8 minute read

Rage of the Unpaid Intern

By Shreya Kollipara

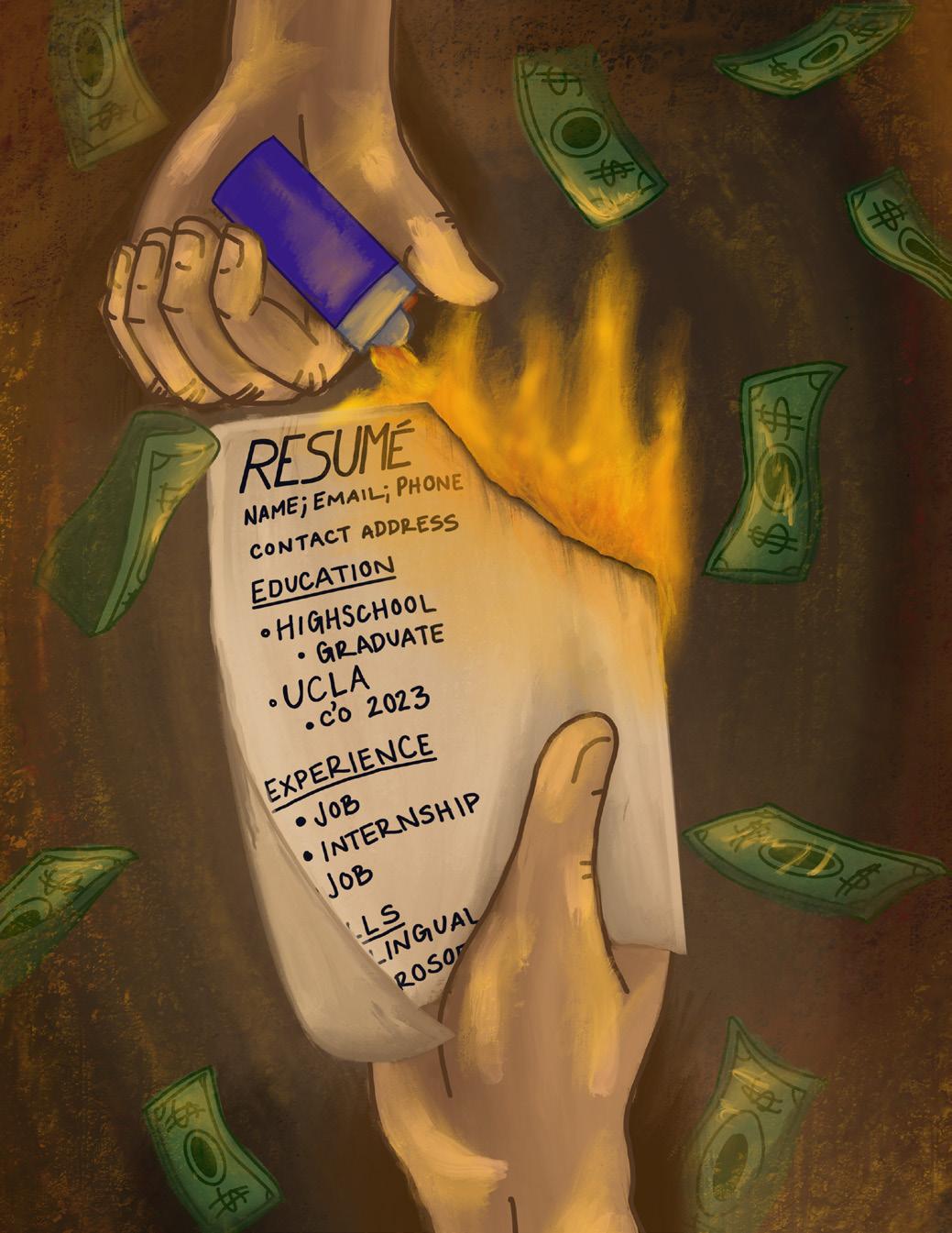

The unpaid internship is a tale as old as time on college campuses across the country, a sacred rite of passage before one enters our capitalistic hellscape – I mean, booming American economy (cough cough). But as an intern who’s done her fair share of labor (with enough experience to warrant a mere comment, or even a whole article), I am dying to know why my contributions as a student do not deserve to be compensated if they are so dearly necessary. Why have we normalized unpaid work in so many industries, and what makes it any different from exploitative labor practices abroad which we are so quick to criticize? The flowery concept of an internship draws students into a cosmopolitan mirage, a world where exploitation under the premise of “building your resume,” “gaining experience,” or “paying your dues” is justified and even reasonable. Unfortunately, unpaid internships exacerbate inequities even as graduating students enter the workforce, and ironically enough disproportionately affect those students who cannot afford to do unpaid work in the first place. I interviewed students at UCLA who have worked as unpaid interns in different fields, drawing from their experiences and rage to inform my own.

Advertisement

Before delving into the anecdotal, let’s consider the significant body of research pointing to the prevalence and unpopularity of unpaid internships nationally. University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Centre for Research on College-Workforce Transitions estimates that roughly 31% to 58% of internships do not pay in the United States. Another study shows that 43% of internships at for-profit companies are unpaid. The National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) also conducted a study in the spring of 2019 to analyze the internship experiences of 4000 seniors across 470 member universities and colleges, and found that: i) Hispanic and Latino students were more likely than any other racial group to not have interned prior to graduation, ii) Women made up 81% of unpaid interns despite 74% of the survey respondents identifying as women, and iii) First-generation college students only represented 19% of all paid interns even though they made up 22% of survey respondents — and more than a quarter of these first-generation students had never worked an internship. One of the conclusions drawn from this survey was that students with paid internship experience tend to perform better in job fairs and receive more job offers. And why would they not? Similar research shows that nearly 80% of all employees at the Big Four accounting firms have previous internship experience, and this trend most definitely extends to larger tech companies such as Google and Facebook. much as other employees) are susceptible to racial and/or disability dis crimination, ex ploitation, and sexual harass ment. “When you’re not get ting paid, in essence, [you] have no protec tions. For the protection of the individual, people need to pay” says Vera. Unpaid interns are not eligible for federal workplace protections, much less any accommodations un der the Americans with Disabilities Act; while a few states like New York have initiated some protections for unpaid interns, many have not.

Despite deviously deepening existing social and economic divisions, the unpaid internship makes students vulnerable, tricking them with resume candy like Hansel and Gretel’s infamous Gingerbread Hag.

The legality of unpaid internships is also lost in gray area, unclear and exception-ridden. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act, unpaid internships are only legal if the in tern is the primary beneficiary of the settlement, which is determined by a seven-point test (this is only appli cable to for-profit companies, since public sector and nonprofit orga nizations are held to different stan dards). These guidelines become more elusive for international students without authorization to work in the U.S.; an intern still must be the primary beneficiary but their inability to be appropriately compensated does not give employers a legal loophole. In fact, if the terms of their internship violates the FLSA, they could be breaching the terms of their immigration status and risk deportation. An international student I spoke to, M, told me that to receive the Curricular Practical Training (CPT) work authorisation (i.e. the state authorisation required for students on F-1 visa programs to pursue any practical work experience) she had to enroll in a 2-unit “shell” summer class at UCLA called “Internship Studies.” Although UCLA itself has no role in helping international students find internships, the class requires students to write a two-page report at the end of their summer and pay the summer quarter’s exorbitant tuition and campus fees just to stay and work in the U.S. legally.

Other UCLA students I interviewed discussed their unpaid internship experiences with me, showcasing how these positions allow for exploitation and/or unfair treatment across all industries. My friend J was recently hired as a Fashion Design intern for a popular fashion designer and celebrity stylist in Los Angeles; she mentioned that most of her work involves doing the “dirty work,” including organizing, scheduling, picking things up, and dropping things off using her own car (and here’s a bonus: they don’t pay for her gas). Although she ac- knowledges relevant takeaways from the work, she says that her workload and responsibilities were unprecedented – especially due to the lack of compensation – and that the fashion industry is unfortunately largely held up by unpaid labor because “if you want it badly enough, you’ll do it for free.” And if she didn’t work the job, somebody else would. Another student M, who works as a legal assistant in the public sector, talked to me about how strangely structured the legal field in the U.S. is — although paid positions rarely exist at the undergraduate level, work experience is still expected (despite not being officially required) when applying to law school, even though you may not be very useful without an LLM / J.D. degree. She also notes that the legal profession is heavily characterized by dominance and office hierarchies; a social barrier tends to separate interns, paralegals, and attorneys in the office, explaining why she is routinely referred to as “intern” instead of her name, and how disrespect and exploitation are embedded in legal office culture.

Interestingly, unpaid internships are largely concentrated in (although not limited to) a few fields — government/public sector, politics, fashion, research, nonprofit organizations and other altruistic work. In a Teen Vogue interview, Massachusetts representative Ayanna Pressley discusses how unpaid labor under the guise of experience is all too common: “In politics, working for free was the norm.” Funnily enough, the White House only recently announced that it will be offering also require those studying journalism, education, or social work to complete field work that is almost always uncompensated. However, many organizations in these fields provide such contested opportunities because they cannot afford to pay student workers to begin with, pointing to larger issues of equity that go beyond this conversation.

A player that is somehow conveniently overlooked throughout this discussion is higher education institutions. When a student works an unpaid internship to receive credit, their employer does not provide said credit, the university does. Technically, students pay tuition for “credit,” although no classroom or professor is required — so you are paying to take time away from school, a social life, and other responsibilities to then work a job that will not return the favour! Make it make sense! In the same interview with Vera, he mentions how such arrangements provide employers with legal cover, and that “Universities are staying quiet because it’s an additional revenue stream for them at the expense of their own students.” I interviewed two students who mentioned receiving academic credit at UCLA instead of actual payment for their work; one student, K, worked at a talent management agency and was required to be oncall 19-28 hours a week (depending on the week), and another friend, M, works for a mechanical engineering

What this modern market has failed to realise, or even conveniently taken advantage of, is the fact that working for free still comes at a cost — it is only a question of who can bear it. With student debt on the rise like never before, is this a game we’re still playing?

Naturally, these consequences disproportionately affect low-income students of color who are already subject to the burden of paying their student loans. Women are also further liable to additional economic difficulties given the gender wage gap and the issue of unpaid household labor being predominantly tackled by women. Moreover, the role that race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and economic privilege play in being able to i) receive an internship offer, and ii) afford to work an unpaid internship is an indispensable part of the problem. Another NACE study conducted between 2020 and 2021 showed how the majority of students working unpaid internships identified as white men. The unwillingness or inability to compensate students for their labor is a direct barrier to entry, exacerbating generational wealth gaps and hindering social and economic mobility. The price of unpaid work is the opportunity cost of working elsewhere simply to make ends meet, but a larger disadvantage presents itself when students without the financial security to work such positions graduate and find themselves lacking the required industry experience to move forward. In this way, a cycle emerges: financially comfortable students are rewarded with resumes filled to the brim, and low-income students are confronted by an increasingly competitive job market that is still stuck in its delusion of meritocracy.

The graduating workforce today is welcomed by a new and improved set of obstacles, including relentless “degree inflation” or even “experience inflation” (the inflation of candidate qualifications and requirements) for what are supposed to be entry-level jobs. An interesting solution emerging through discourse is the introduction of paid apprenticeships, or even micro-internships. A paid apprenticeship would include a similar scope of responsibilities as a full-time role post graduation, allowing for a more accommodating transition while providing much-needed experience and knowledge. A micro-internship is a short-term role offered to undergraduates, allowing students to build transferable skills, take advantage of other opportunities, and most importantly, be compensated; Parker Dewey is a company that is actively working with college career centers to make micro-internships accessible!

Another approach to eliminating this barrier — or at least to successfully mitigate its consequences — is legislation. A measure being considered in California includes $5 million in funding to provide stipends to 650 low-income students and graduates working unpaid internships at the State Department (Why can’t they just start paying their interns? Ask the White House). New York labor laws also include specific stipulations regarding internships that make it virtually impossible for employers to profit from unpaid work. We’re not where we need to be, but at least that’s a start.

So, what now? Do you take that sexy unpaid internship or worry about never finding a job? A recommendation I’ve come across is reaching out to your employer for a minimum stipend to pay for food and travel, if you can afford to work the job. Some schools also provide smaller grants for students working unpaid jobs! Unfortunately, my rage is not consequential — this is something that is bigger than me, bigger than us. Even in my critique of the concept, I must acknowledge the privilege I’ve held to accept such work in the past and perpetuate inequity in the labor market. But student worker strikes across campus have shown us that one way to bridge the gap is to start the conversation. I can hardly expect Will Smith to slither out of a golden lamp and drop a stipend into my lap, but I can definitely ask why the government won’t.