Micheline Gingras was born in Québec City, Canada, 1947, to Roméo Gingras and Rosée Dubois, sixth in a family of seven. Both Roméo and Rosée grew up on small subsistence farms outside the city. Together, they both left the land, moving to the city to improve their economic futures. Catholicism was then the national religion of the province with the church managing the public schools. Micheline was a typical student in school where nothing was expected from girls since they were destined to be mothers and housewives. In 11th grade, her art teacher, Ms. Blais, recognizing her latent talent, encouraged Micheline to enter a citywide art competition, the winner being offered admission into a classical European-styled fine art school, Les Beaux Arts de Québec. After a full day of successfully completing several drawing assignments, Micheline was accepted into the school, beginning fall, 1963.

Roméo was against her studying fine art for several reasons, most importantly a desire for Micheline to work in the family moving business and a fear of licentious behavior in the school. Despite his opposition, she nonetheless persisted and in 1968, graduated with a Master of Fine Art, Cum Laude.

Micheline interviewed for a job at the Montréal Expo 67 Worlds Fair, becoming a tour guide for the Canadian Art Pavilion. It was there, she met her future husband. Their relationship led her to move to New York City in 1969. After an extended tour of Europe, they moved into ‘Tribeca’ in 1971, at that time still a fading industrial neighborhood.

During this time of loft living, Micheline developed a major painting series, “La Main Méchanique” (“The Mechanical Hand,”) 1971-73. She was entranced by the morning ritual of factory workers being disgorged from subway stations,

destined to go to their industrial jobs and machines. Her stated concerns at the time were,

My intent was to show, in a humorous yet serious way, how each of us is controlled by a “mechanical hand” of culture and history, especially in the solitude of urban life. My hope was that people could sense this control and divest themselves of their conditioning and renew their spirit and soul.

This work was critically successful, and shown at the Musée du Québec, Québec, CA, in 1973 and the Centre Culturel Canadien, Paris, FR in 1975. https://michelinegingras.com/painting

Two major bodies of painting followed; “White on White,” in 1976, (a virtual concept realizing a sense of touch through sight), shown at Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montréal, CA, the Canadian Cultural Center, London, GB, and the Kornblee Gallery, NYC, in 1976. The “Origin of Man,” in 1979, (portraying the birth of man from natural phenomena), was shown at the South West Gallery in New York City. Micheline began showing her work in commercial galleries in 1976 but became quickly disillusioned with the prospect of selling her work. Feeling that she had nothing left to say in painting, she decided to teach art at Saint Ann’s School, a progressive institution, in Brooklyn Heights. In this fashion she maintained her interest in fine art and current issues.

In 1980, I joined the art faculty at Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn Heights. Since that time I have taught almost exclusively 4th and 5th graders. Their artistic endeavors have never failed to fascinate and inspire me. I have discovered that the most interesting assignments are ones that pique my own curiosity. By investing my energy, enthusiasm and wonder, I often feel that I am really collaborating with my students as we embark on a path of discovery. One project leads to another; a drawing is transformed into a painting, which in turn, leads to a relief or a sculpture as the end result. By creating assignments that last 4 to 6 weeks, the students can relax their insecurities and have multiple opportunities to explore their creativity, skills and imagination. Another major component of the projects is the recycling of domestic materials. This creative approach

teaches the students that “art” can be something made out of nothing, and is everywhere.

Micheline taught at Saint Ann’s until 2017. This teaching was an important influence in her subsequent art expressions. In her classes, she made use of recycled materials, an anomaly in the department. Styrofoam trays became printing plates for holiday cards. Small milk containers became a foundation for the construction of chairs. Empty ½ gallon milk containers became small barns in a farm landscape. Large plastic juice containers combined with branches became fantastical creatures. Discarded magazine and newspapers were the raw materials for mosaic collages. Influenced by an environmental consciousness, emphasizing that the ordinary discarded materials in one’s life could become the basis for making art, was a major lesson imparted, one that quickly became evident in Micheline’s own work.

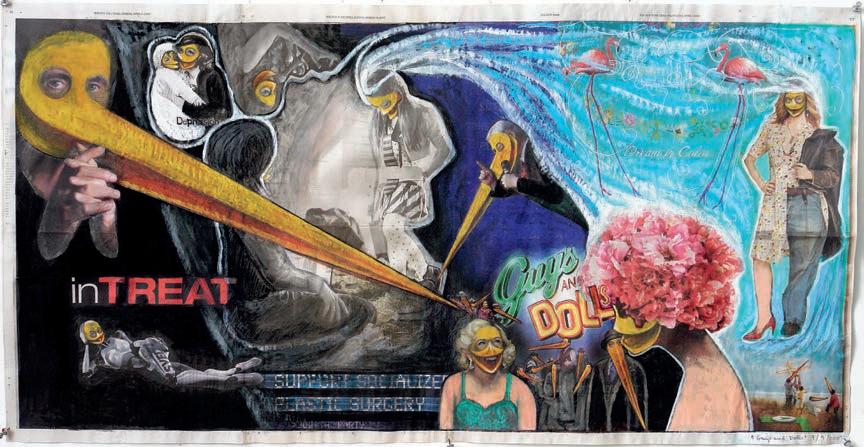

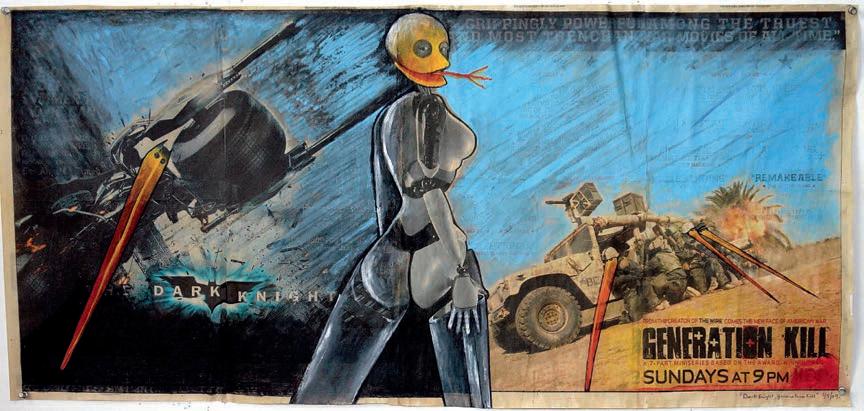

Intrigued by the use of collage, having explored it in fine art school and in her own journals, Micheline was always an avid collector of images, at first, utilizing the NY Public Library Picture Archive and later, clipping her own images from mass media especially the New York Times. During the bank failures and political upheavals in 2008, Micheline decided to return to her early social and political concerns. In a series of collages, the “Mis/Representation (Meltdown)” 2008-10, she created a pantheon of suspicious and dishonest individuals all sporting the beaks of scavenging birds of prey. Each collage was created on one or two existing pages of the NY Times. In addition to utilizing traditional collage techniques, Micheline also used her formidable painting techniques to bridge the cuts and seams of collage. https://michelinegingras.com/paper/ meltdown-2008-10

This seemingly naïve work became the fundamental foundation for all subsequent work. The experience of teaching children was reflected in the intuitive construction and story telling involved in each composition. Reducing complex political issues to those of an innocent unconscious individual trying to comprehend matters beyond their experience resulted in an “outsider” perspective in the realization of her interior

reality. Even the choice of mediums, recycled newsprint and left over tempera reflected personal concerns of recycling, wasting nothing in creating art.

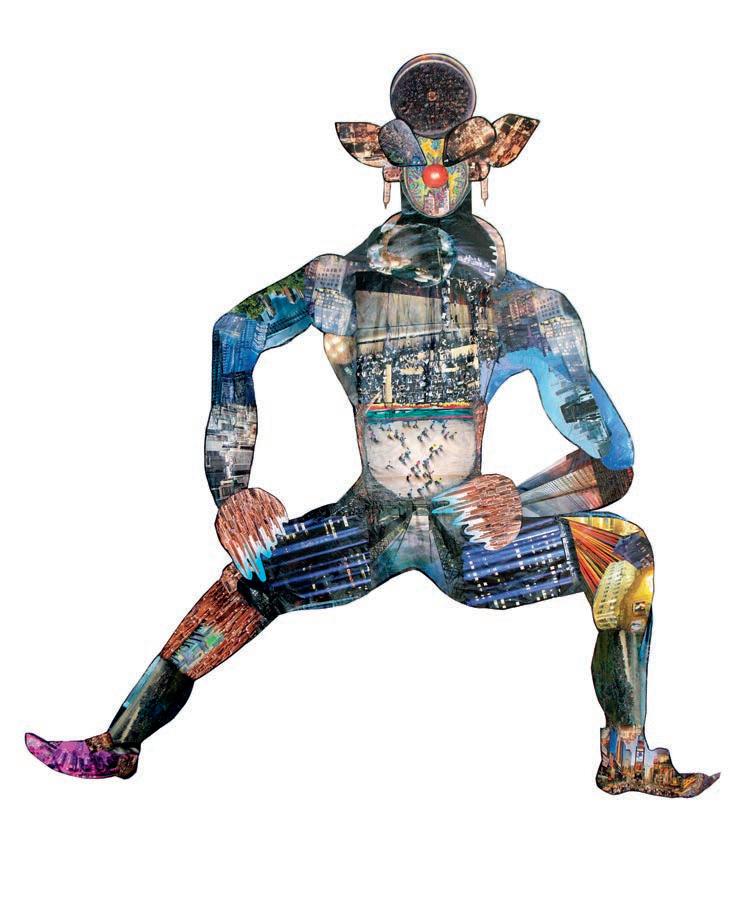

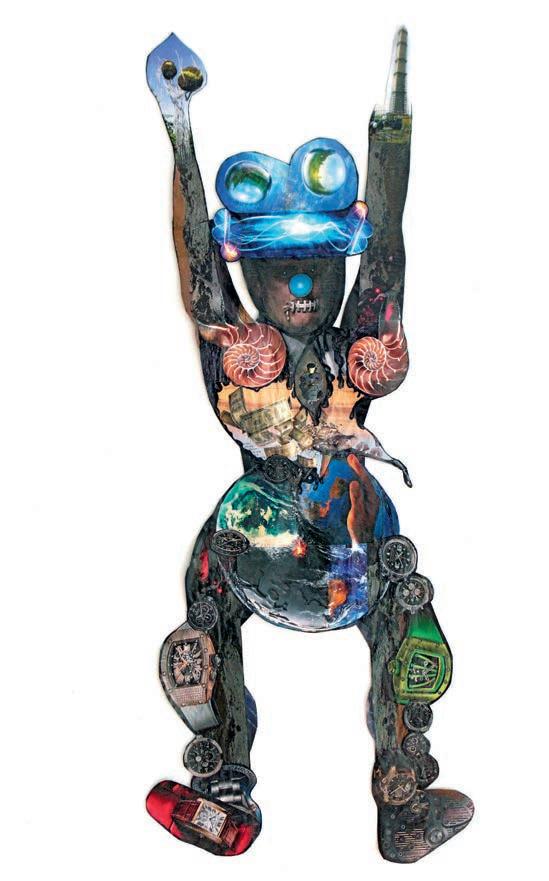

This body of work became a springboard for the numerous ideas that followed. “Clowns,” 2013, is a powerful series of nearly life sized dream like figures, each constructed of a welter of consumer images that terrifies the viewer into imaging a dystopian future.

This body of work was created to confront my fears concerning the current state of affairs in our country. I perceive that our political system is weakened by decisions made that are not

always in the best interests of the people governed. In my sensorial nervousness, my feelings are distracted, threatened by unraveling scenarios. I offer these often-grotesque dancing figures as a visual record of their absurd manners and the guttural multitude of discomfort existing in our times…

Each of my twelve fictional cutout figures comments on an aspect of our national reality. I fight the feeling of being manipulated as a commodity, disgusted by the tricky subjects of power and abuse. The clowns I depict, govern us poorly but must be realized as part of our society and ourselves. They are scary and sadly untrustworthy. I myself pathologically try to constantly discern what we are being told to do, and what is being done to us, simultaneously in disarray, and confronting the dishonesty (too much “clowning around”). https://michelinegingras.com/paper/clowns-2013

As Micheline grew more confident in the use of her materials and more secure in her understanding of her political points of view, her collages grew in size. Gluing together several pages, using discarded backdrop paper, her canvas grew larger and more physically confrontational. Again her use of painting techniques made these “canvases” more mysterious and confusing. The viewer’s eye could not trust what was being seen as one enters into the tableau.

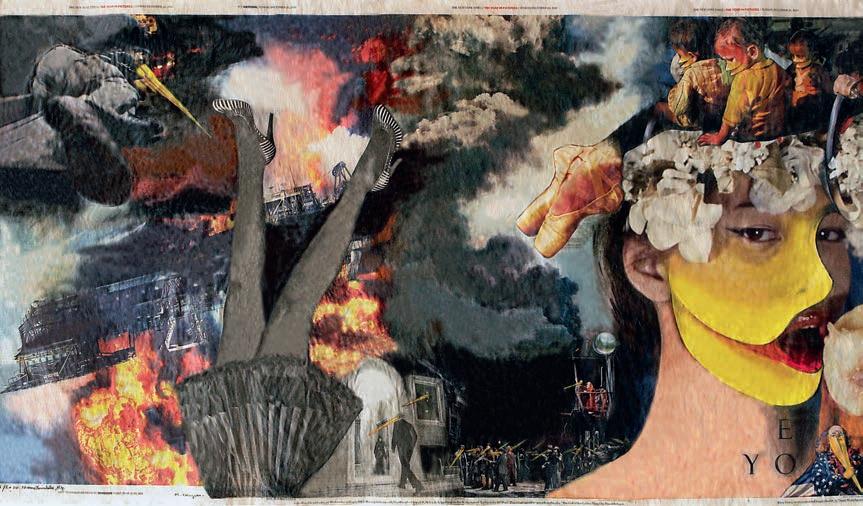

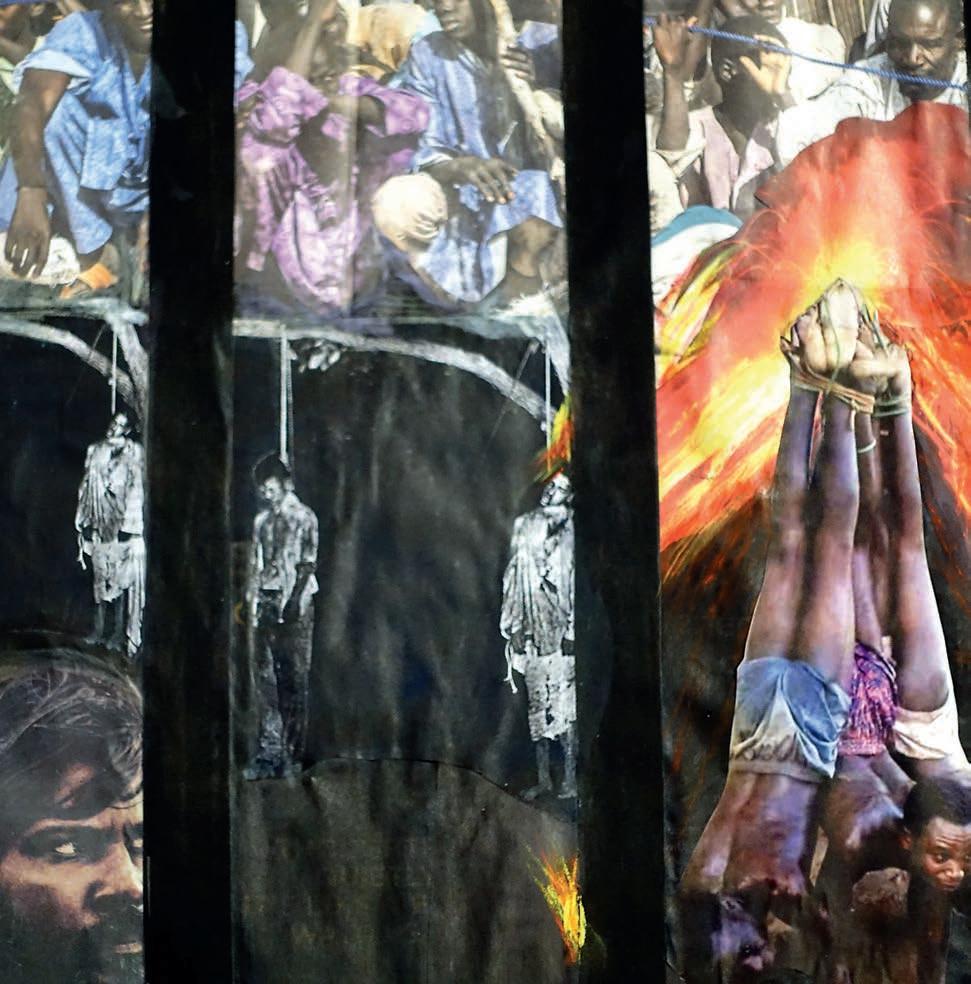

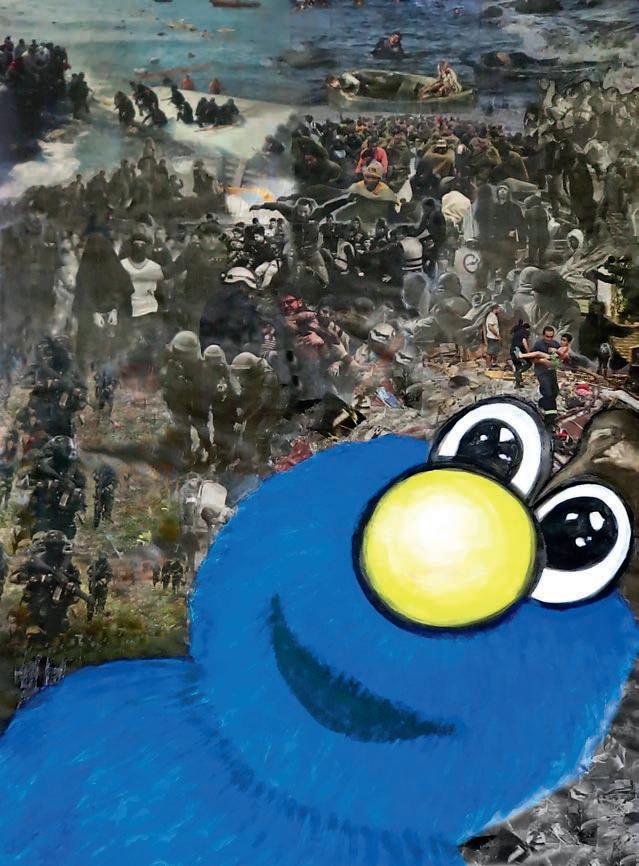

“End Times/ Aftermath,” 2015 further explores themes of social injustice. Micheline explains,

(This work) gives vent to my uneasy frustration with the apparent lack of justice in today’s world. There is a foreboding feeling as innocents confront images of machines that impact us. Mixing and compressing crowds and faces with various media images of “real” news, presents uncomfortable political pictures of our current times. I wish to give voice to invisible people who during local wars are forced to leave their homes, seeking refuge in dangerous and desperate ways… Are we not in the process of disconnecting from a communal society,

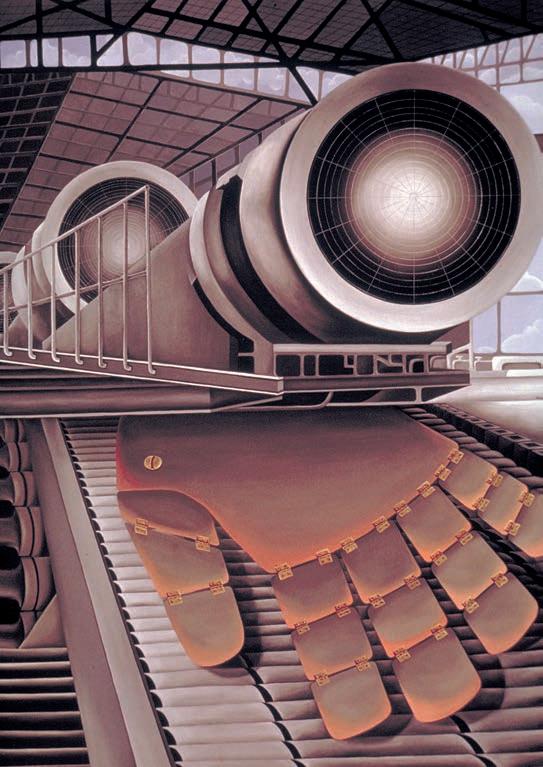

left: Mechnical Hand, The Manufacture, 1971, 48”w x 72"h, oil on canvas

alienated by social media, stuck in our individual anomie, trying to attain culturally determined goals, paralyzed by never ending wars, becoming all immigrants in pathos… And we, who are responsible for the turmoil that causes such grief and tragedy, wash our hands of our responsibility.

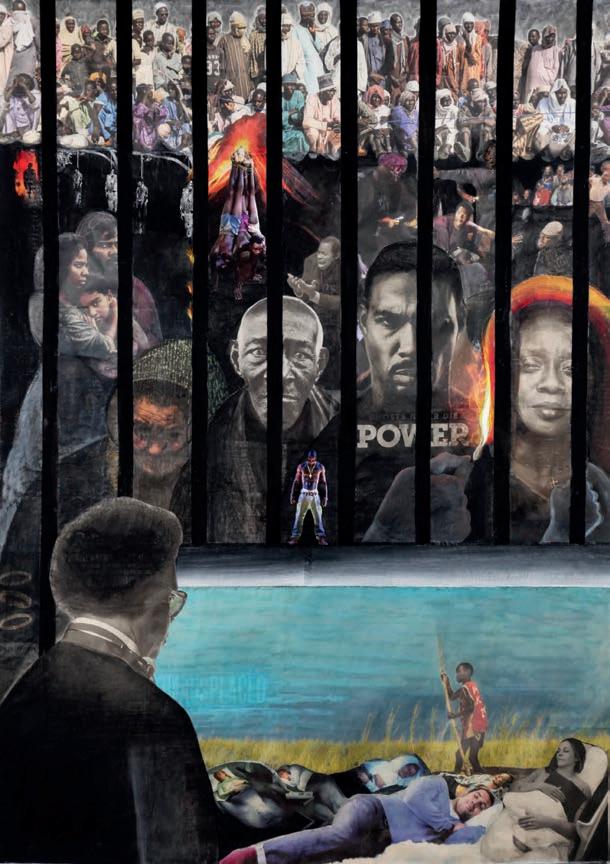

The most powerful painting of the series, “Amnesia,” 2016 (Image #21), literally portrays the enduring issues of racism and incarceration in America. A silent black individual, under brutal and dark collaged vignettes of prisoners behind bars, another calmly watches a white family asleep during a picnic while a small black boy resolutely paddles a small boat upstream. https://michelinegingras.com/paper/end-timesaftermath-2014-17

Faced with tragic images, many experience a visceral fear and revulsion. In my case, I feel a strange fascination. The dramatic images drew me into the portrayed experience. Yet at the same time, I remove myself in the act of collecting… Viewing tragic images, we can become sensitized, perhaps with empathy, puzzled and intrigued, vaguely feeling that horrific reality. We distance ourselves, relieved that it did not happen to us. Why this overwhelming sympathy I feel when viewing these images? Can I make a difference accepting the “realness” of the image, using it in my art?

By this time, Covid was becoming overwhelmingly manifest and disruptive. In an introduction to “Malaise”, 201820, Micheline wrote.

(It) arrived full force, imprisoning all of us in our own bubble. My summer was haunted and prolific. I reacted to the media bombarding us with unsettling images and latent anxieties. Chaos was in the air. One at a time, I dealt with each of my concerns using images, colors, textures and painterly strokes to exorcise my fears through each collage. I felt lucky to have my art to reflect on the changes in our daily existence.

“Malaise” saw Micheline’s work reaching a maximum of presence and scale. Her collage technique created more dense and elaborate compositions, deliberately pressuring the

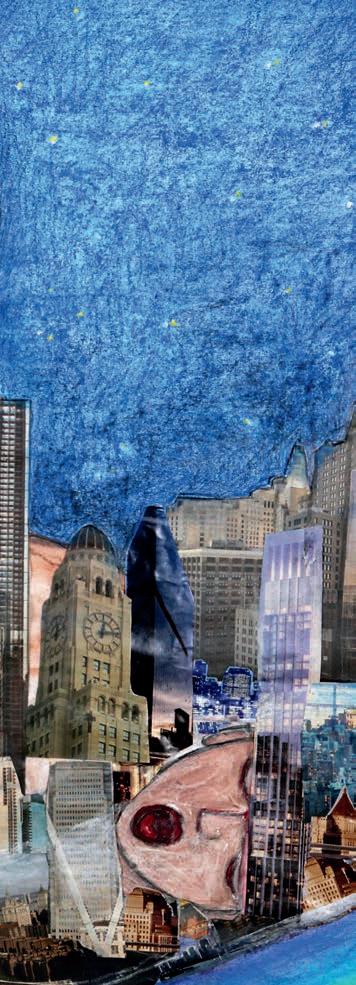

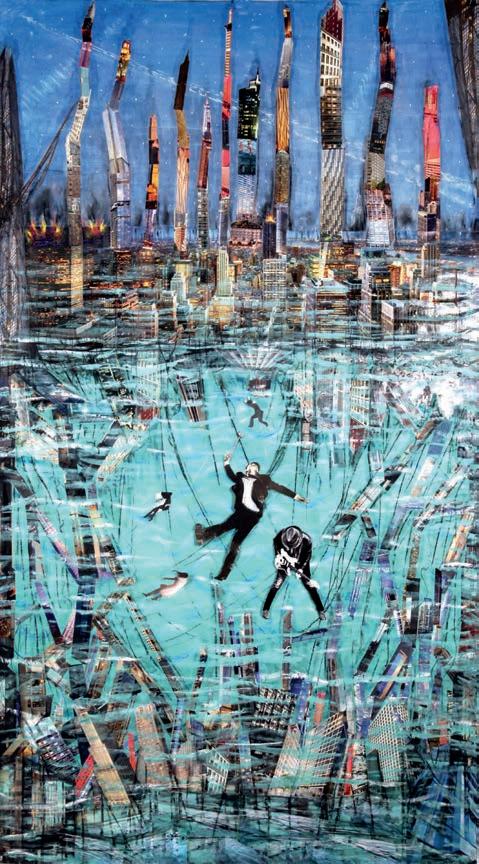

viewer to deal with her artistic and social concerns. “Home/ Less/Nest,” 2020, (Image #33), directly juxtaposes homeless encampments in front of the imposing architecture of the Supreme Court building, with an ironic “Equal justice for all” on the façade, surrounded by high-rise buildings; wide-open “innocent” eyeballs tacitly accepting tragedy. “Icarus, Crime and Punishment,” 2018, (Image #29), creates the haunting image of an urban metropolis sinking into deep water as its inhabitants slowly dangle, seeking salvation, accompanied by a guitarist, blithely playing a song and a businessman, selfie-taking, oblivious to the surrounding chaos. “Golem,” 2020, (Image #32), larger than life size, is a masterpiece of detail and painting. Ostensibly the portrait of an exhausted football player, his cape is filled with fragments of tragedy, under the bare foot of Buddha, as skyscrapers tilt ominously while the seas rise. https://michelinegingras.com/paper/ malaise-2018-2020

My state of emotion in the time of Covid-19 motivated me. I needed to describe my frustration regarding the state of the world. Our normal state of existence had been crossed out. We, the living, are emotionally sandwiched between life and death. Uncertainty and fear rule our lives. Life during the summer felt cancelled. Everyone’s lives were disrupted. Jobs lost, vacations postponed, families socially distant. Everything was crossed out, X’d.

“X’d,” 2020, was a culmination of the themes previously explored. The desire to creatively explore the national distress over the unforeseen pandemic resulted in instinctive emotional explorations. Abstract compositions like “X-Tended,” 2020, (Image#35), became a means to describe barely articulated fears. “X-Pulsed,” 2020, (Image #34), turns the world upside down and inside out as cartoon eyes confront the viewer in a destabilized environment. “X-Hale, CA,” 2020, (Image #38), depicts the existential fears of natural environmental degradation at the hands of a nature we have created. Two discreet eyes at the bottom of the painting, observe dinner place settings for a last supper. https://michelinegingras.com/ paper/xd-2020-2021

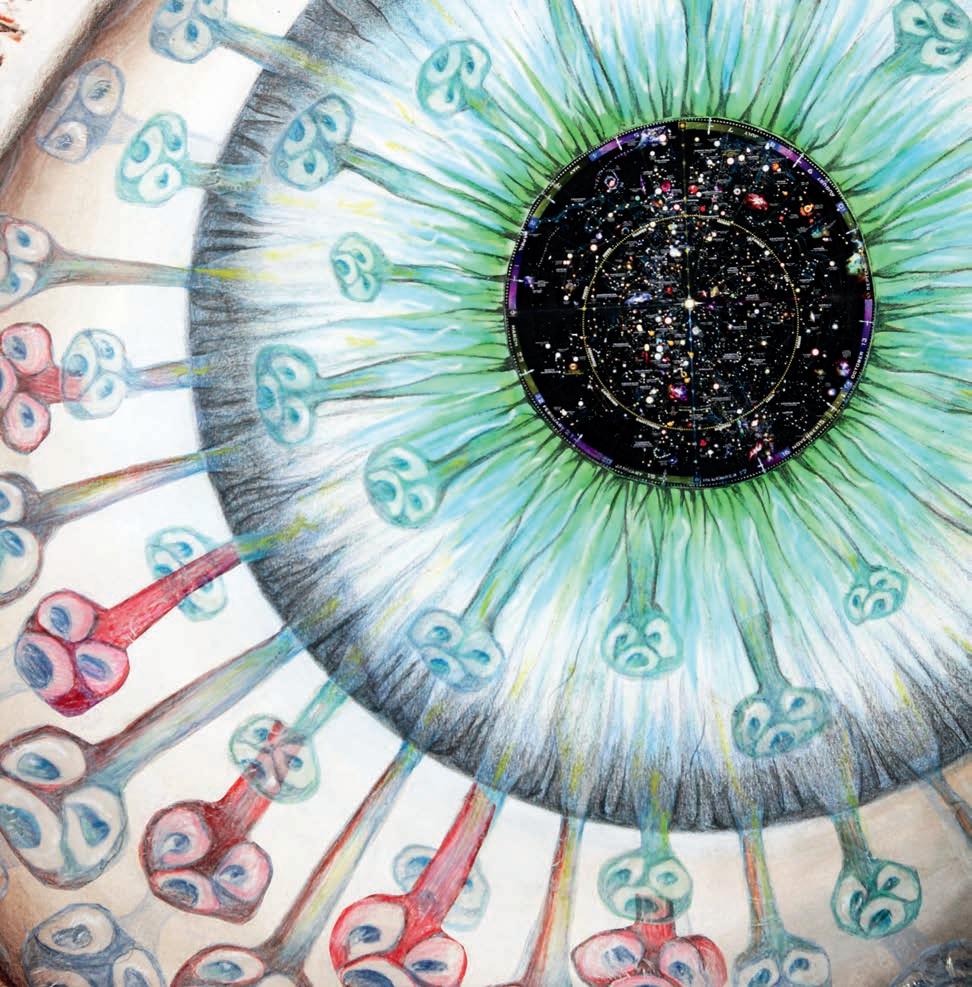

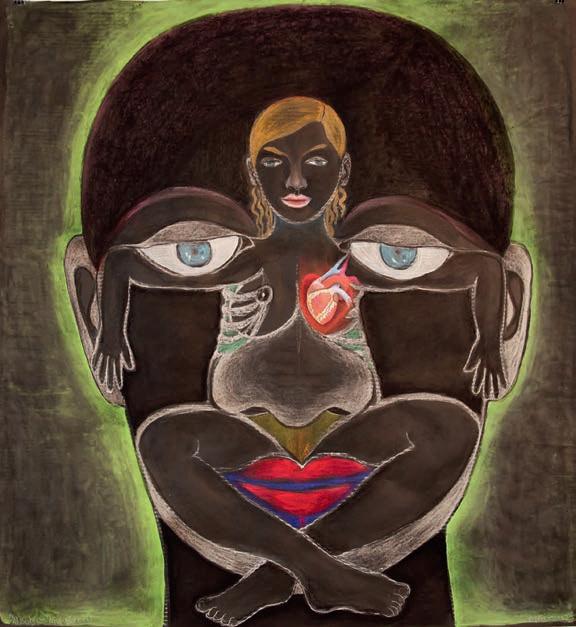

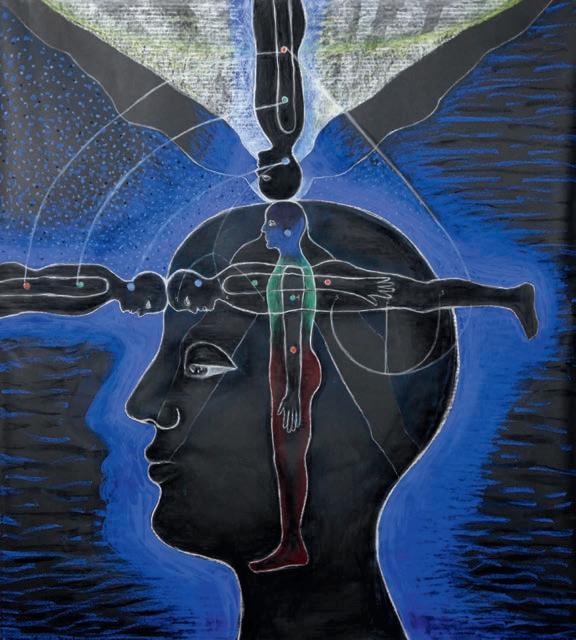

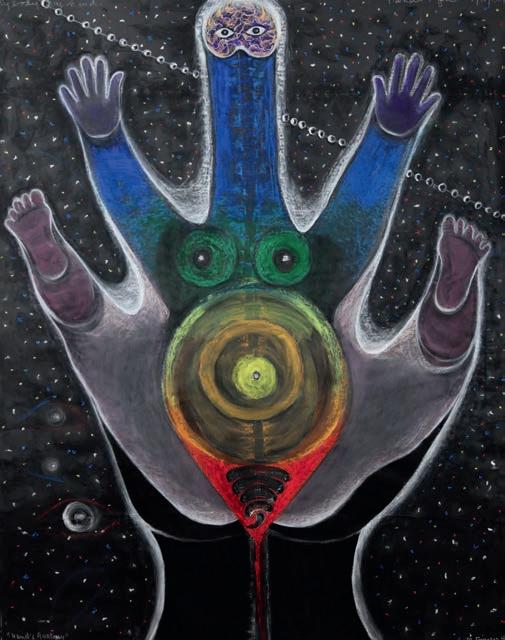

“Inner Space Mysteries,” 2021, came about at the height of Covid. Returning to an illustrative style, Micheline decided to portray different medical issues and information.

In May 2021, New Yorkers relaxed during the Covid pandemic, once vaccines were generally available and accepted. In this time of confinement, a lot of close friends were going through difficult personal times. I felt that if I could interpret and illustrate specific areas of our body’s anatomy, I could perhaps better understand what was going on with my friends. Hopefully my art, with some humor and color would bring a bit of hope and possible comfort.

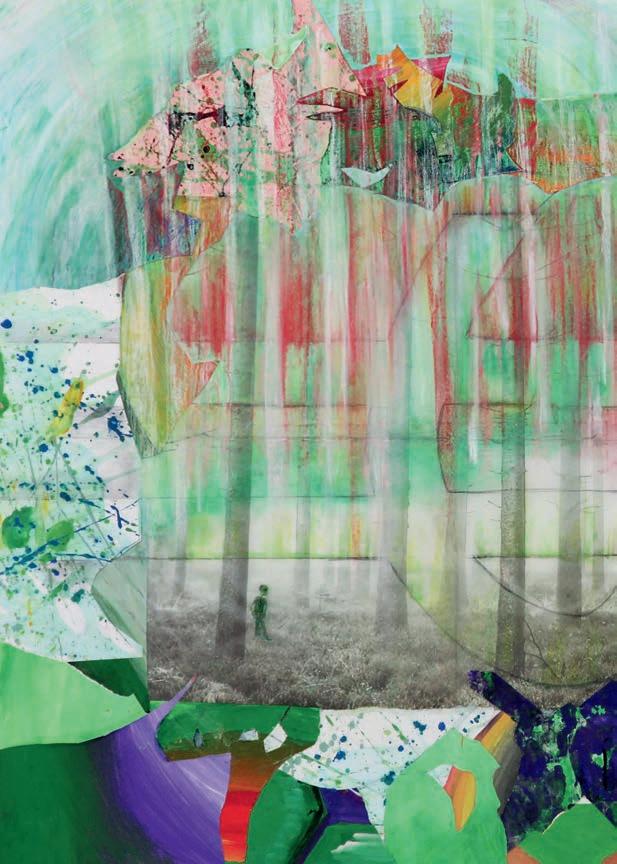

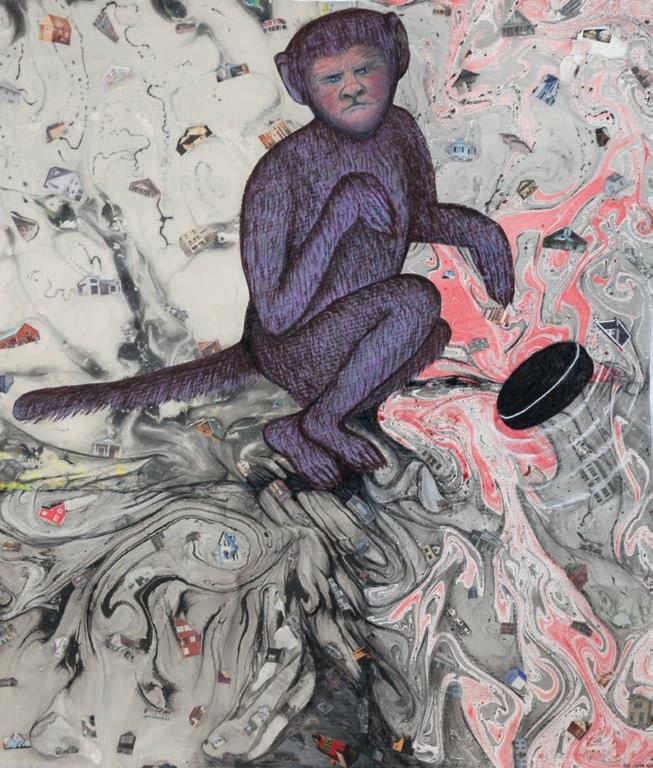

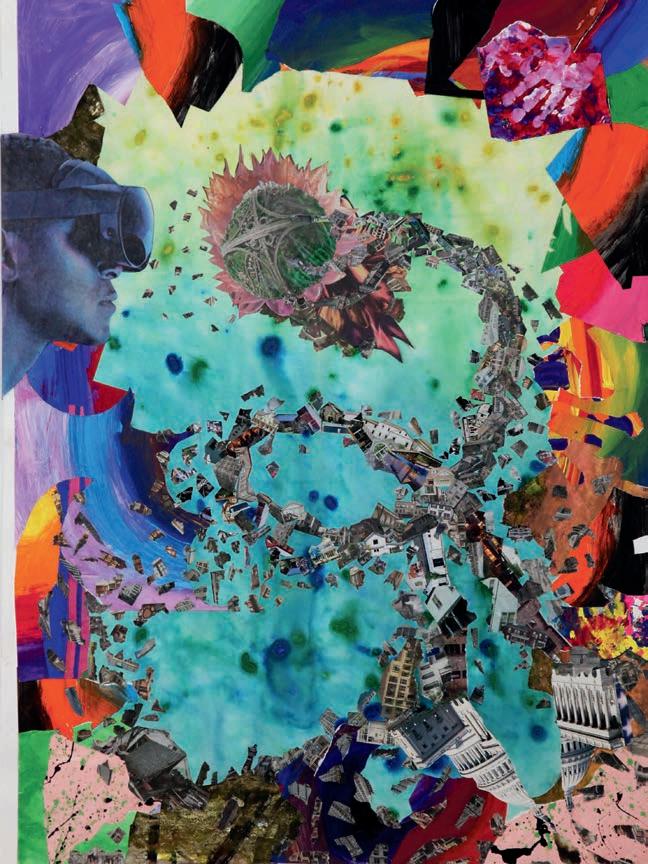

Micheline in her entire career has been a firm believer of confronting her anxiety by making art from it. By depicting the ‘issue” maybe a solution can be found. Her most recent body of work is “Anthroposes,” 2023. This work exhibits a sense of humor, as it addresses the new culture wars of identity and gender. Gender fears are being politically exaggerated in the media. Anthropomorphic animals, a mixture of human features and animal bodies poke fun at right wing fears of “trans” children. “Monkey Puck,” 2022, (Image #50), mocks the unsubstantiated fears of a nascent Christian moral majority. Turning from social issues, the newest work attempts a bridge between abstraction and realism. The idea of framing social issues into abstract and cubist bright frames of color appears in “Virtual Demolicious,” 2022, (Image #52), as a large entangled deadly flower grows, observed in virtual reality. “Aurora Boreal,” 2022, (Image #46), addresses voters who fear their loss of power while ignoring toxic environmental health problems. The natural world tries to survive, amid incessant human exploitation. What will be for sale after all forests have been devastated? Distractions attenuate our meaningful attention from the plastic detritus that mark our civilization that will last long after us. In “What to watch,” 2022, (Image #51), a riflescope sight targets the World Cup players as the broken colorful frame is connected to images of the Ukrainian

right: White on White, Water, 1975, 48"w x 72"h, oil on photo sensitized linen

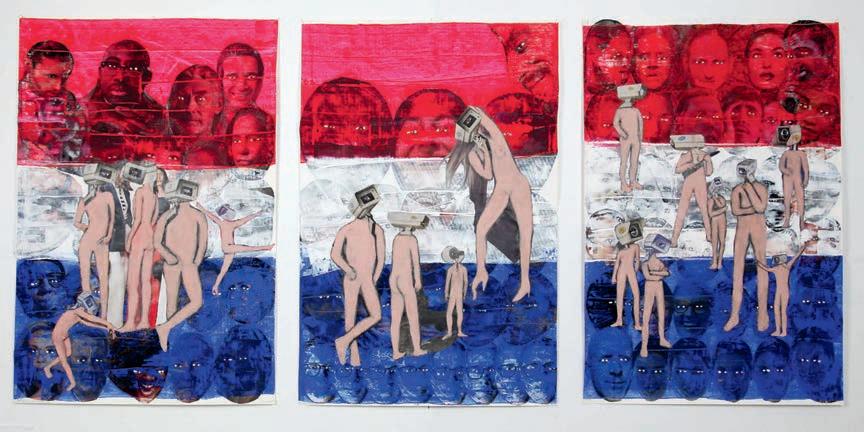

war. Which will hold our attention? “Artificial Surveillance,” 2023, (Image #54), depicts a dystopian patriotic world where everyone both surveils and is under surveillance. So who is watching whom and what for, all seems illusion.

After all is said and done, I come to place all this earthly humanity, dissonant materials and detritus at the very center of an immense, receptive and inclusive engulfing ocean of creation. What goes down comes up again in this process of re-imagination as the tides cycle high and low. Myths are depicted in my art and drawings, aiming to reach a minute potential idea of acceptance and inclusion.

“Scared Crone with Oil Rigs,” 2023, (Image #53), is a virtual self-portrait of the artist trying to warn of the impending doom due to mankind itself and it’s earthly attachment to personal consumption and exploitative capitalism.

democratic tool for broadcasting differing viewpoints, inviting everyone to communicate and also provides a necessary feedback to the artist who often needs help to further their creative process.

https://www.michelinegingras.com

Although she has worked hard to create a social media presence, this has its limits. But a lack of exposure has not deterred Micheline from pursuing her creative efforts. She has stated her beliefs, quite simply.

I process the world around me. I am generally an optimist in nature… My grandfather Thomas, a farmer, continually reminded us: ‘Don’t worry, tomorrow will be worse.’ But for today, I create.

I first met Micheline in 1981, as she was transitioning into teaching. Micheline’s intuitive imagination was a pleasure to experience. Unfettered by the constraints of a gallery system, Micheline could explore ideas, forms, shapes and techniques inspired by her class assignments without worry or obligation. At times I would help her with technical issues. The sheer abundance of her personal creativity was always a fascinating mystery.

Micheline has been dedicated to addressing our very natural existential anxieties by deciding to vividly portray them in her canvases. She has committed herself to steadfastly working everyday over the past 15 years to realize her vision. Working in the studio has been a balm for her. Sharing her work with the public though has been a struggle. Without access to the NY commercial gallery scene, this work has not been publically visible. Micheline’s website documents the full range of her creative efforts. She states simply its purpose.

Observing the images I placed on this website, what you, the viewer, see in these bits of information, become your very own to interpret, share or reuse and make your own. A website is a

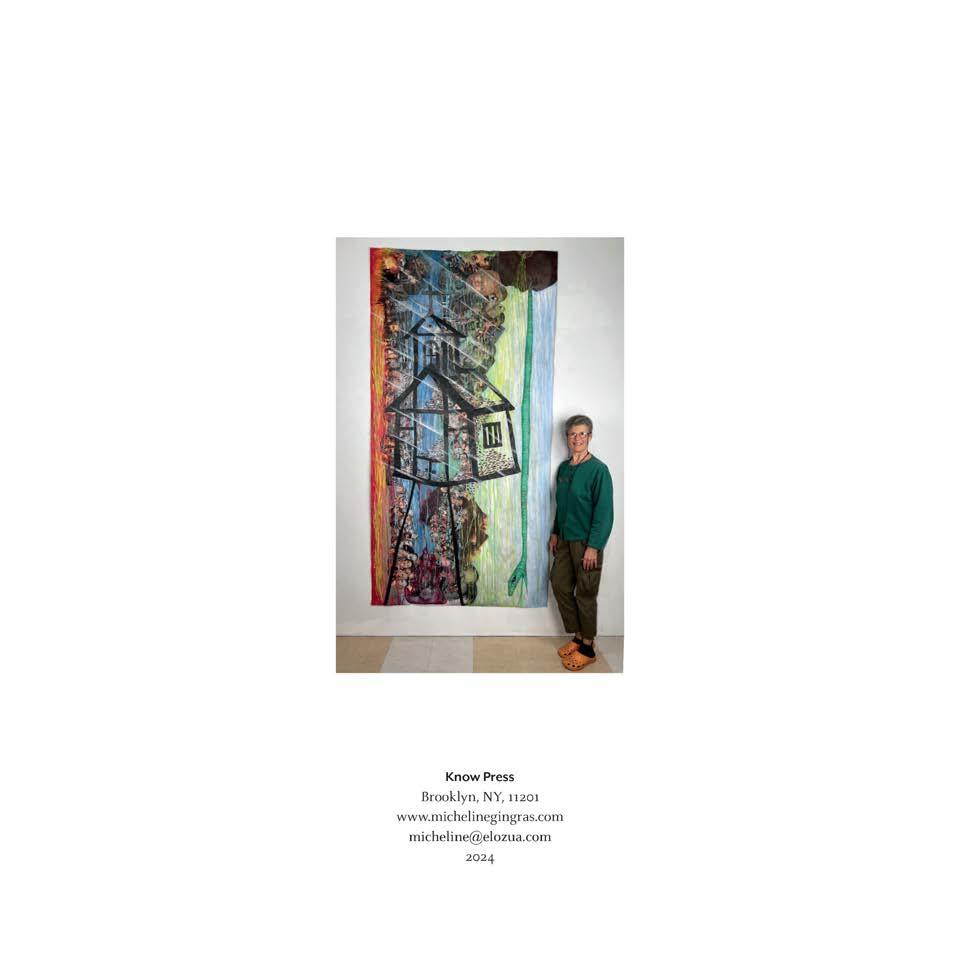

left: Origin of Man, Crystal Ball, 1977, 48"w x 72"h, air brushed acrylic on canvas; above: Micheline Gingras, studio portrait with Minerva and Golem, 2020

1. Retirement, 2008, 22”h x 24”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

1. Retirement, 2008, 22”h x 24”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

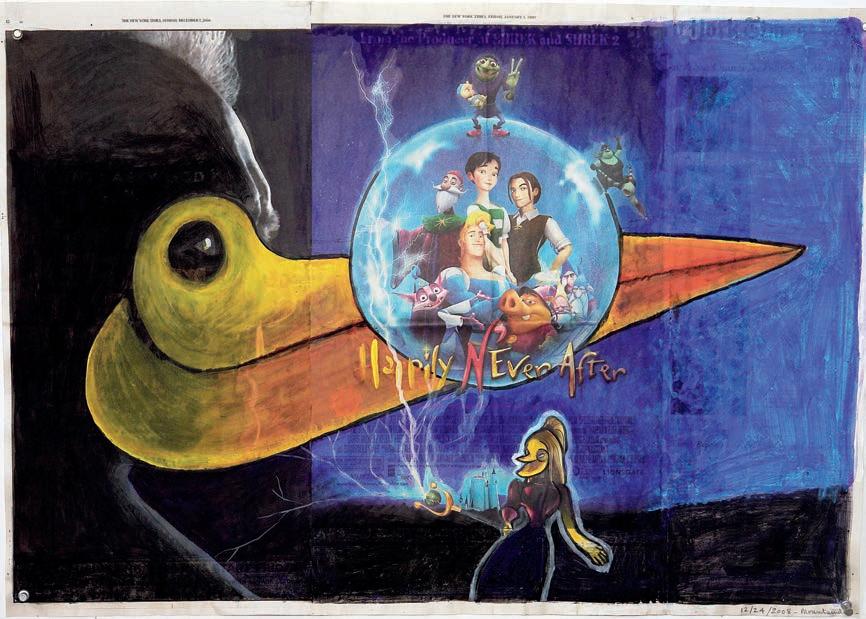

2. Happily Never After, 2008, 22”h x 31”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

3. The Haunting, 2009, 22”h x 33”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

3. The Haunting, 2009, 22”h x 33”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

4. Mother’s Helpers, 2010, 22”h x 36”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

4. Mother’s Helpers, 2010, 22”h x 36”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

5. Guys And Dolls, 2009, 22”h x 48”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

5. Guys And Dolls, 2009, 22”h x 48”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

6. Nobody Owns, 2009, 22”h x 44”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

6. Nobody Owns, 2009, 22”h x 44”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

7. Generation Kill, 2009, 22”h x 44”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

7. Generation Kill, 2009, 22”h x 44”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

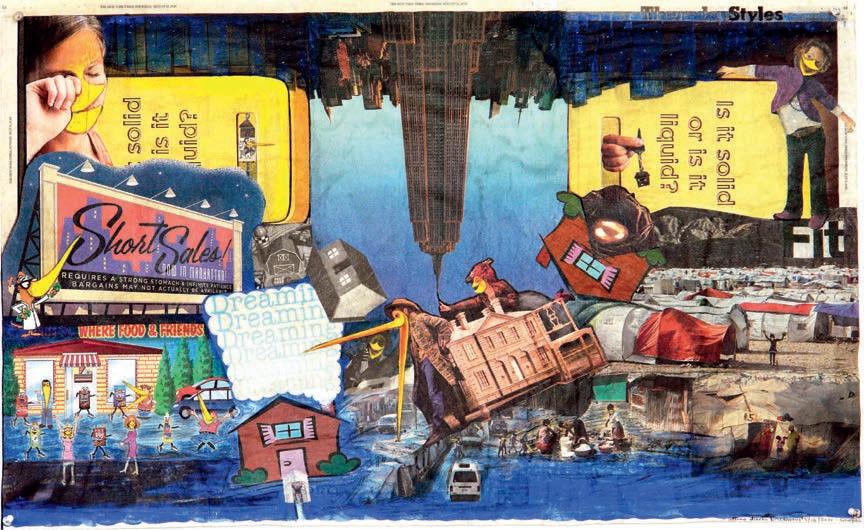

8. Katrina, Flood Dream, 2010, 22”h x 36”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

8. Katrina, Flood Dream, 2010, 22”h x 36”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

9. Thumb Generation, 2010, 22”h x 40”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

9. Thumb Generation, 2010, 22”h x 40”w, collage, tempera on newsprint

11. GMO Plants, 2013, 61” x 41w,” printed media and acrylic medium

12. Cynical Promises, 2013, 57” x 45w,” printed media and acrylic medium

13. Faux Nationalism, 2013, 64” x 59w,” printed media and acrylic medium

14. Factory Farms, 2013, 57” x 45w,” printed media and acrylic medium

Micheline Gingras’s artistic career began with The Mechanical Hand, a series of 18 paintings, one sculpture and assorted drawings, first shown at the Musée du Québec, Qc, Canada, in 1973.3 While the focus of this essay is Gingras’ monumental collage works, the Mechanical Hand series of the early ‘70s demonstrate how even in her early paintings, collage as a way of thinking is present. In style, the aesthetics and composition of the Mechanical Hand paintings recall 1920s Precisionism, particularly the work of Charles Sheeler but crossed with René Magritte. These early eye-popping wonders, benefit from a visual language based on, if not collage, at least its modernist cousin, montage. For this series of odd and uncanny oil paintings relies on the shock, and absurdity, of the graphic juxtaposition of a gigantic flat pink mechanical hand posed in various positions in urban and industrial settings.

But these are not just representations painted from the imagination. The mechanical hand is an actual physical entity.

We run in circles. We are tense. We joke about it. We resist yet we buy into the fabric of the ache. We can call events, hypocrisies, since one thing is said but another is done. Trying to reassemble images of the media mumble jumble gave power to my unconscious. These found images migrate from my mind, through my mind and soul. They are a record of our times and illustrate who we are becoming.

–Micheline Gingras2It is a cutout being that Micheline constructed from Masonite with tiny brass hinges and screws.4 Looking back from the present, Micheline writes,

I realize how much these paintings touch on the social and cultural changes that were occurring in the late 1960’s. My intent was to show, in a humorous yet serious way, how each of us is controlled by a “mechanical hand”of culture and history, especially in the solitude of urban life. My hope was that people could sense this control and divest themselves of their conditioning and renew their spirit and soul. Today, I realize that this same struggle endures, and I accept the manifest difficulties in “real” change.5

Maybe an unconscious inspiration for making the Mechanical Hand series as a wandering cut-out, was Michael Snow’s Walking Women (1961-1967), which she saw while working as assistant to the director, Duncan de Kergommeaux, Collage is born of interruption and the healing instinct to use political consciousness as a glue with which to get the pieces into some sort of new order (though not necessarily a new whole, since there is no single way out…)

at the Canadian Art Pavilion in the Montréal Worlds Fair, Expo 67. Snow’s Walking Women silhouette was about notions of iteration, repetition, and the moving image rather than the singular object as a sculpture. As the film historian Scott MacDonald put it, “Much of the work’s original impact must have involved the surprise of discovering still another variation and a new context for the Walking Woman motif” since Walking Women is “really a single huge work, developing through time and space like a long musical composition, a work meant to defy conventional esthetic categories and the assumption that artworks are intrinsic entities.” 6 Micheline’s Mechanical Hand also defied categories. Here is a description of the original exhibition from Arts Magazine, 1972,

The ubiquitous element in the show was a huge mechanical hand, a flat, puppet-like shape articulated with hinges at the joints and painted a dead flesh orange. For the most part she has carefully underplayed this image, eschewing the easy shock value and concentrating on the act of painting itself in a clean and strongly defined style that suggests a marriage of the naive with the metaphysical. One of the most appealing features of the exhibition was a series of photographs of a huge hand that

above: Mechanical Hand Sculpture, West Side Pier, NYC, 1971, photograph, 11”x 14” right: Mechanical Hand, The Gate, 1971, 48”w x 72”h, oil on canvas

Ms. Gingras took around New York and set up is such unexpected places as subway stairs, startling images that recall the sciencefiction film of the witch-hunting days 7

As we learn from this article, these works of the early ‘70s are about the making and placing of the “huge mechanical hand, a flat, puppet-like shape …painted a dead flesh orange” in urban and industrial contexts as much as they are about the exhibition of the completed paintings.

The Mechanical Hand series is also of note for the way it prefigures themes and conditions of downtown New York in the 1970s with its growing preoccupation with mass media, capitalism, technology, and advertising. I think of

Cindy Sherman’s Film Stills (1977-80), which are about the “mechanical hand” of cinema’s transformation of our 20th century unconscious by the history of cinema, or Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities, 1976-1982 where young urban well-dressed professionals are swept and roiled by an urban wind that suggests the heady gales of financial capitalism and neoliberalism, or the iconic John Baldessari piece I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971), seen here in a film still, where with pen and paper, a hand writes “I will not make boring art,” over and over like a machine or a punished school child. Made the year before Gingras’s first mechanical hand, Baldessari’s iconic work would be written today with the aid of a “mechanical” algorithm.8

The work in this catalog was made between 2008 and 2023 and consists of epic, theatrical, narrative vertical and horizontal collages. As she said in 2009,

I juxtaposed all kinds of images, a veritable DADA-esque tapestry of skepticism. Utilizing full-page images of movie advertisements from The New York Times, I collaged and over-painted the images to create a unified whole. Real and imaginary worlds clash and commingle. Using colorful cartoon child-like imagery and humor, re-presenting and drawing over these images, allowed me to cushion the harsh reality of our mass illusions.9

The first body of work, Mis/Representation (Meltdown), 2008-2012, was made during the bank failures and political upheavals of 2008,10 It includes a series of collages with tempera on newspaper featuring “a pantheon of suspicious and dishonest individuals all sporting the beaks of scavenging birds of prey.” 11 In Nobody Owns, 2009, (Image #6), “the distress of the economic system is highlighted by beaked Wall St. executives making decisions that ignore the common good.” In Mother’s Helpers, 2010, (image #4), on the right, a painted male figure in profile, with a huge translucent yellow beak, opens his mouth as if to speak or yell. The beak is painted with a beam of light so we can see an image of a World War II bomb bursting forth,

threatening to explode like a comic book bomb. Upside-downfigures are collaged in uneven lines underneath. The figure of a woman with a painted beak seems to fly in from the left side of the painting like a Renaissance angel holding a champagne bottle, which spills red paint over the scene, passing by Mother’s Helpers, a Disney Snow White figure who also wears a beak. It is a cosmic nightmare. Part conflagration, part anti-war message, recalling in wit and outrage, Martha Rosler’s collage series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, 1966-72. Micheline uses her formidable painting techniques, utilizing primarily tempera on the newsprint, to bridge the cuts and seams of collage so that Yo! 2010, (Image #10), and The Haunting, (Image #3), 2009, read like morality tales where beaked horror figures loom and are juxtaposed menacingly across a chaotic urban landscape. Painted in all sizes and shapes, the beaks Micheline paints, range from duck-like to the extended razor of a long-billed Curlew. They read like medieval plague masks dipped in the affective duplicity of Pinocchio’s extra-long nose.

Among the many boxes of images Micheline has stored away, one is labeled “Tragedies.” This box contains images collected “since 1970, my arrival in NYC” when,

America was in upheaval. The civil rights anti-war movements meshed with the counterculture of new freedoms, the woman’s movement, and a sexual revolution, creating major changes in the domestic social fabric. Today our country endures a 9/11 mindset of forever wars and cultural clashes over abortion, LGBTQ rights and Black Lives Matter, among others. And the pandemic isolates everyone into oppositional political spectrums rather than unified efforts to keep everyone safe…Challenged by curiosity and a deep need to comprehend how things work, or don’t work, I allow my imagination to wrestle with my e/motions. My reason and intellect organize the bits of ideas and images that surface, now becoming my painter’s palette. The purpose and process of collage begins.12

In Katrina, Flood Dream, 2010, (Image #8), Micheline creates an homage to the nightmarish neglect of the people in New Orleans by the George W. Bush administration during

and after the 2005 Hurricane Katrina. A cacophony of beaked figures float, march, and strut like puppets from a commedia delle arte show, telling the story of a city roiling with debris and disaster. A collaged billboard with the words “SHORT SALES NOW IN MANHATTAN” in mid-century font, with “REQUIRES A STRONG STOMACH AND INFINITE PATIENCE. BARGAINS MAY NOT ACTUALLY BE AVAILABLE,” in a smaller font below. The billboard rises above a convenience store where beaked products such as dish soap, cereal boxes, and canned beans parade like children under a rainstorm in the flood waters. The word “DREAMING” appears in a collaged cartoon cloud. To its right is a river of tumbling houses-one with a leaning figure dressed in cap and long coat, whose open V-shaped beak threatens to swallow the whole world. A figure in the upper right of the image, comical yet deadly, holds onto an upside down Manhattan-scape where the Empire State building plummets down from above as if to say, Katrina threatens the whole of the country. “Is It solid or is it liquid?” appears in large bubble font on what look like an iPhone screen in Post-It yellow, resting horizontally. A white female with a small beak,

rubs her eyes as the figure on the right smiles with cocked head, arm resting on top of a yellow tablet. As with all of her collage work, the foreground background relationships are infinite. One point perspective is never her point as her surfaces are never static or flat.

Made the same year as Katrina: Flood Dreams, Thumb Generation, 2010, (Image #9) reads like an epic narrative of a cold winter in an urban landscape on one hand and “contrasts with the joy and warmth of creating a family.” The smiling woman in the center right, multitasks, pushing a baby carriage, holding a cup, her leg askew as if in a comical sketch. A monster truck pulls away from that white middle class nuclear family, dressed in various bird beaks, who sprawl on a couch crushed between a painted baby carriage, a taxi, and a bridge to nowhere.

The residual effects of the iPhone introduction in 2007 created the “new arrival of the cell phone/social media phenomena, with the power use of the agile thumb over the index, to text, the new thumb generation.” 13 Thumb Generation could be a portrait of the students Micheline taught. You see her trying

to work out what this “Eak Preview” (collaged fragment glued upside down at the bottom) means for future generations. The familiar muppet figures -googly eyes and red rubber noses -peer out while discreet floating words on black paper arrows spell out: I’M, GOING, TO, are suspended below the profile of a threatening beaked head and figure using a cell phone. “A discreet message, a potential alert of destructive forces, at the right bottom corner of the page -marked (as if to urgently invite others to): “Share.” 14

Collage as a method of construction has existed for centuries, but the moment two male artists in France, glued scraps, fragments of physical paper (or some other physical entity) onto a canvas or piece of paper or block of wood, the meaning of European painting and modern culture changed. In this origin story, the modernist moment of radical collage is one of male rivalry. Braque made the first papier collé, titled Fruit Dish and Glass in 1912, using mass-produced faux bois wallpaper purchased in Avignon. “To gain a surreptitious advantage over his partner and rival, Braque, waited until Picasso had left Avignon for Paris before beginning to incorporate strips from the roll into his charcoal drawings.” 15 Even so, Picasso upstaged Braque by gluing a piece of oilcloth, painted with a trompe l’oeil design of chair caning, onto his oval shaped canvas which he then framed with a thick, hairy piece of rope. Picasso’s choice to add an extra layer of labor and texture to Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) not only changed the being of painting (again) but also introduced the blunt brute mass of physical things or “materiality” into the conversation. What once was a Surrealist romp through flea markets in search of oddball objects and materials is today called upcycling. Matter used in upcycled art made in the 2020s, from rubber tires, torn newsprint to glitter and plastic bags, signifies the anthropogenic effect on the planet -also known as the Capitalocene and a worldwide reckoning with the debris of capitalism and colonialism. Micheline’s collages explore and engage critically with the matter of economic equality, climate change, racism, sexism, and technological transformation that constitute the clowns, monsters, and conflicts of our time.

Micheline describes her archive as a “library of ripped pages” inspired by the thousands of archival flat files at the New York City library She snips and tears her collage fragments, like words, mostly from the newsprint version of The New York Times, and years of collected images and paper scraps. Collage offered a way into the adult world, but even then, it “had to be new, mine in forms, in rules, in ways, not the coloring book with its guidelines.” She continues,

As a ten year old child, I constantly obeyed borders because of my talented friend, Ginette the colorist, who demanded it. Yet, I needed to escape those contours, slipping out of the given lines. Forget the time it takes to be neat. It should be messy and fun. I want to blast out of the confines…. OK, so I search but find no paint. I determine that colorful images in the magazines will do. I rip quickly. On an 8”x 10” cardboard, I lay down bits of torn paper. I need yellow and red because the sun is hot. Hurrying into the kitchen, I find mustard and ketchup. Chaos is magic to a point. Soon the page is covered with slippery materials like condiments and glue, and the eclipse is fading away out there. Still, I am passionately engaged, feeling much more relieved. Time passes. I have found a new game, a new tool to steal away from fear. An illusion of control in a fabricated world enhanced by the thrill of the creative moment, a process that brings me closer to the adult world, isolated yet connected. I am growing;

the germ of imagination is here to stay. I cherish my private sanctuary of making collages when I am home, secure and bold in spite of the chaos out there, always.16

Collage is a tool, a method, and a means of making sense in a world that shirks conventions. No two collages are alike. They depend for their effect on the tension between the new arrangements of dissimilar items. Micheline could have chosen to use Photoshop to “cut and paste” her massive theatrical tableaux. But if she did, she would have created slick frictionless works of art. But friction and texture are the point as these works are about facing anxiety, by collecting, tearing, cutting, and gluing. Collage is about tension and overload, accretion and tactility. It is a form of non-hierarchal thinking, in the words of Dr. Cole Collins,

Similar to Jessica Hemmings’ model of ‘textile thinking’ which is predicated upon ‘soft logics, modes of thought that twist and turn and stretch and fold’, ‘collage thinking’ resists hierarchies and binaries and, instead, its vision hinges upon flexibility and slippage backwards, forwards, within and between concepts –breaking them in to something new.17 (Image #21)

Collage is a form of writing for Gingras, more Gertrude Stein than Jane Austen.

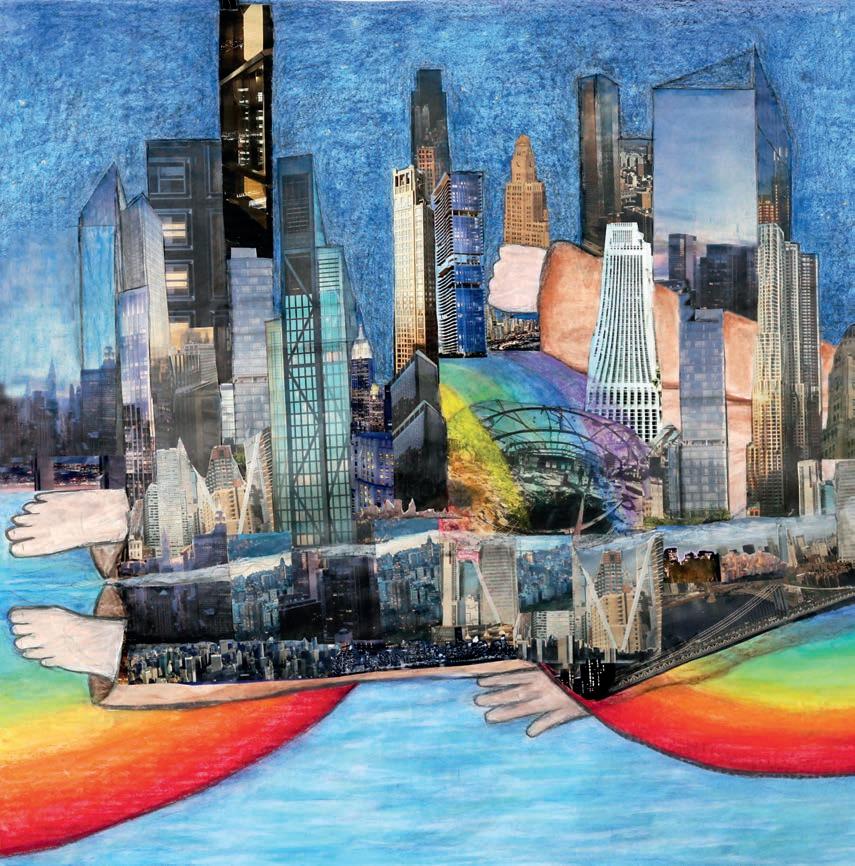

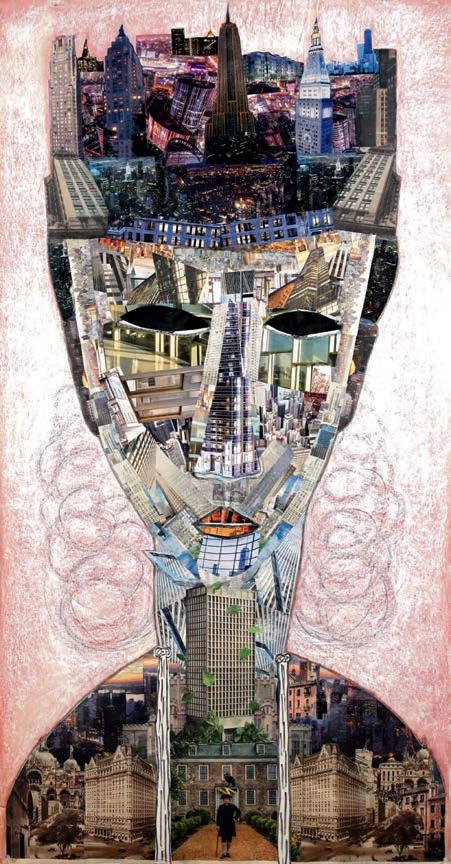

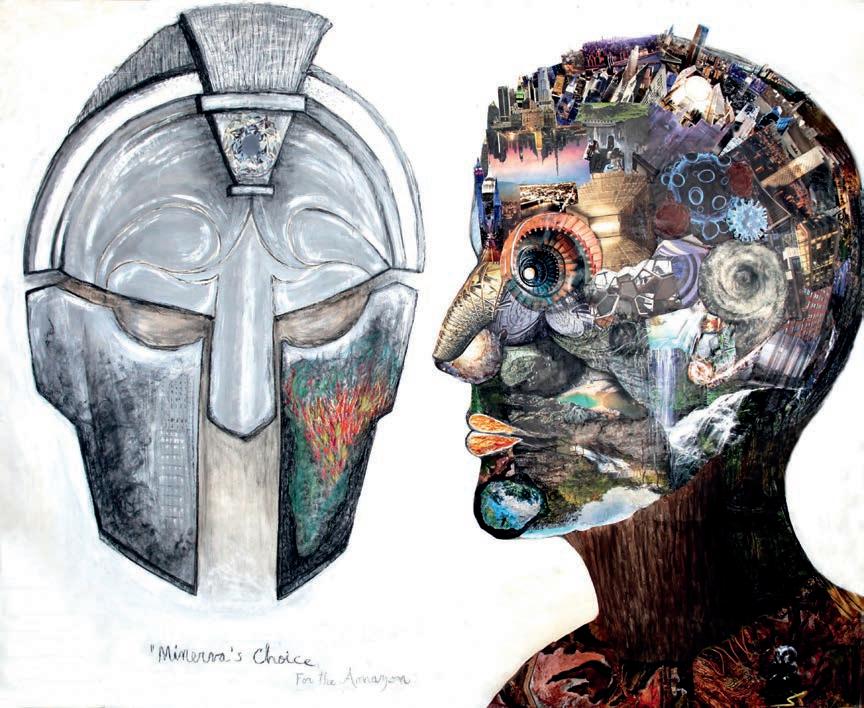

The cover of this catalog is an image, Minerva’s Choice, (Image #31), a 87”w x 83”h, mixed media collage made in 2019. A stark and noble figure cut from forests, cities, landscapes, and skyscrapers, Minerva is the Roman counterpart to the Greek God, Athena, Goddess of wisdom, handicrafts, arts, war, medicine, and, most importantly for the work in Violent Beauty, justice. Centrifugal and multidimensional, formidable, and kaleidoscopic, this gigantic collage of Minerva hails from a world where, as Lucy Lippard says in the opening of this essay, there is “no single way out.”18 In fact, Minerva’s Choice represents and celebrates life as a dense fabric of lived fragments, contradictory and undeterred by reduction -e.g., one-point perspective -a world of mass and volume that dips into stairways and urban corridors, rising and falling. Jutting. Dynamic. Her forehead bursts into a spiky New York City skyline, tiny cut-out

buildings rotating. The eye is a spiral staircase that spins to infinity; the lips are tadpole shapes of fire; the chin is a jigsaw of clouds and mountain ranges. The head emerges from a thick tree trunk neck, set in a primordial forest of autumn-colored fragments of ancient wood deposits and deep caves. The owl of Minerva oversees this arboreal memory. Minerva’s Choice is also a portrait of the artist, Micheline Gingras, as a mind in e/ motion.

There are many art worlds. Some support the making and appreciation of art separate from making money, some consist of makers and appreciators for whom art is life, some require what Arthur Danto wrote in 1964, “an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld,” 19 and some -the one labeled “the” -are consumed and driven by profit, status, and power. For Micheline Gingras, the art world is best described by the early 20th century artist Robert Henri in a quote printed on “two for $5 t-shirts” that the artist and writer Jarrett Earnest discovered at the Robert Henri Museum and Art Gallery in Cozad, Nebraska, “I am interested in art as a means of living a life; not as a means of making a living.”20

What is known as “the art world,” is defined by its umbilical connection to the market, to commercial art galleries, museums, international art fairs, biennials, art magazines, auction houses, media buzz. In this art world, art is deified and defined as an object of affiliation pinned like a dead butterfly to the wall of profit and art historical reputation. In this art world, art is an investment, epitomized and “shaped” by the auction houses and members of the moneyed class, such as Larry Gagosian. For Larry, as he is known, becoming an art dealer was never about art. It was in fact, “an arbitrary choice.” He launched his career by copying the business model of a street poster vendor he saw making lots of money on the streets of Los Angeles. To state the obvious, Micheline Gingras’s art world is not Larry Gagosian’s. In fact, at her periodic “Biennales” mounted in Mountaindale, NY, a sign hangs on the wall, “Not for Sale.”

Micheline Gingras and her partner Raymon Elozua have no truck with an art world where the value of money can easily be substituted for the value of art. They live in Brooklyn Height and continued on page 66

17. Drone Nibaba, 2014, 22”h x 60w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

17. Drone Nibaba, 2014, 22”h x 60w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

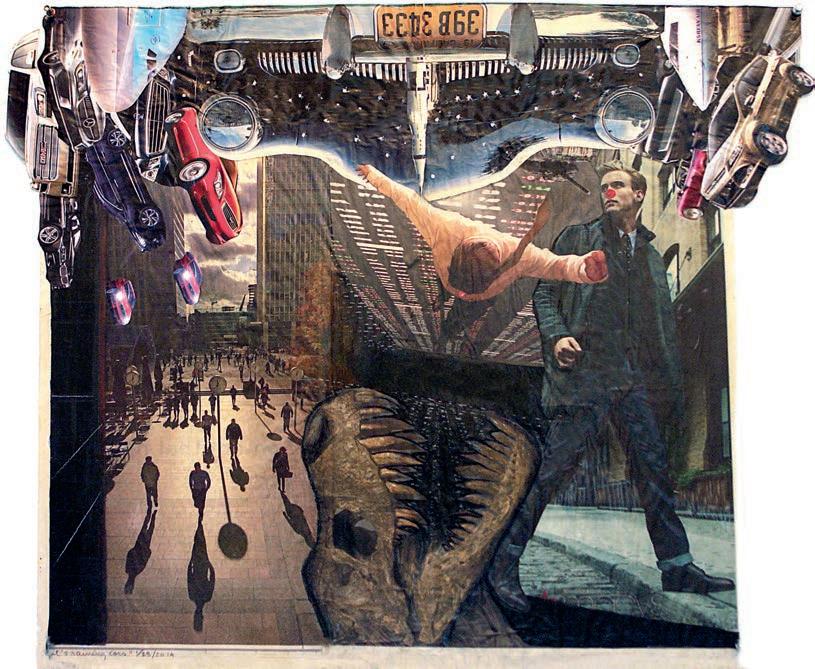

18. It’s Raining Cars, 2015, 26.5”h x 33w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

19. El Monster, 2016, 36”h x 24w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

18. It’s Raining Cars, 2015, 26.5”h x 33w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

19. El Monster, 2016, 36”h x 24w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

20. Drowning, 2017, 21”h x 34w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

21. Amnesia, 2016, 66”h x 48w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

20. Drowning, 2017, 21”h x 34w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

21. Amnesia, 2016, 66”h x 48w,” collage, tempera on newsprint

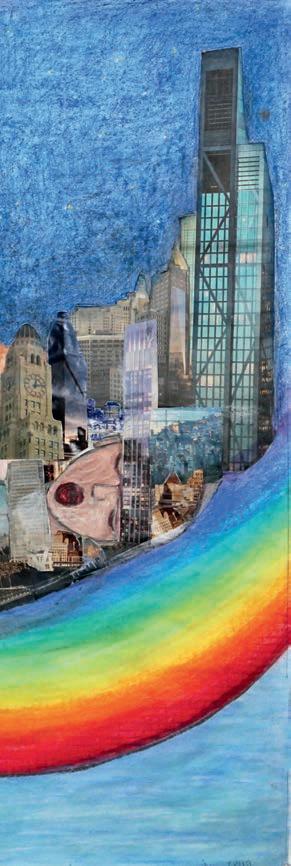

22. Jacob’s Ladder, 2019, 29” x 29”h, collage, mixed media and graphite on newsprint

22. Jacob’s Ladder, 2019, 29” x 29”h, collage, mixed media and graphite on newsprint

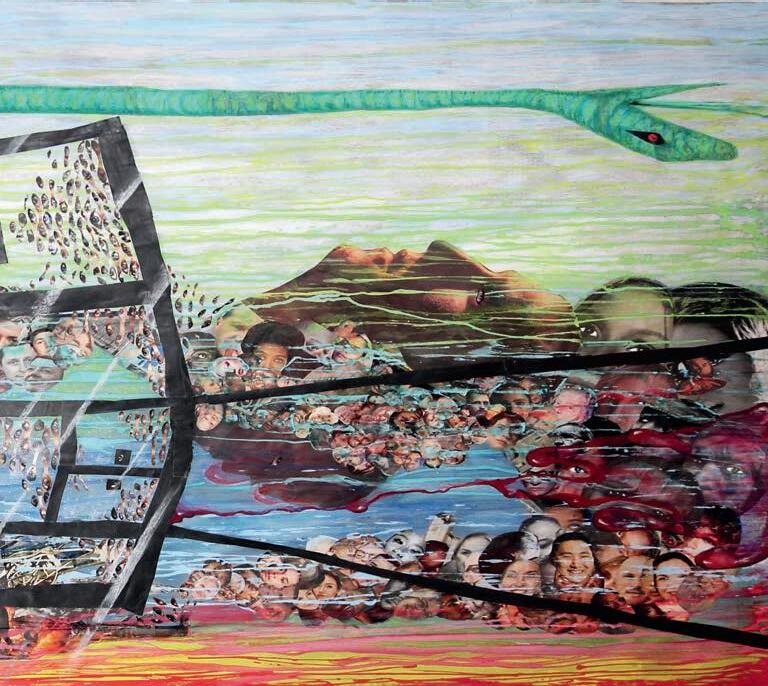

23. Four Elements Plus Metal, 2019, 36” x 82”w, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

24. ManIsland, 2019, 36” x 46”w, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

24. ManIsland, 2019, 36” x 46”w, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

25. Nuclear Towers, 2019, 36” x 83”w, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

25. Nuclear Towers, 2019, 36” x 83”w, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

26. In Trust, 2020, 40” x 70”h, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

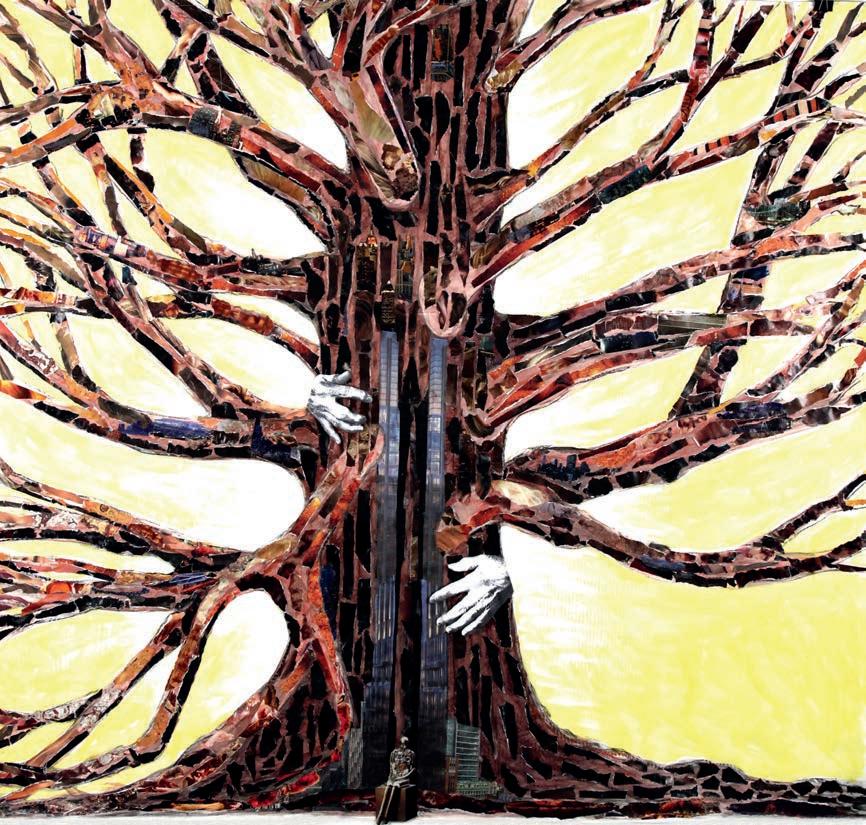

27. Tree Of Knowledge, 2020, 58” x 61”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

28.

29.

Athena’s Vigilance, 2019, 36” x 68”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

Icarus, Crime and Punishment, 2018, 46” x 83”h, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

Athena’s Vigilance, 2019, 36” x 68”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

Icarus, Crime and Punishment, 2018, 46” x 83”h, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

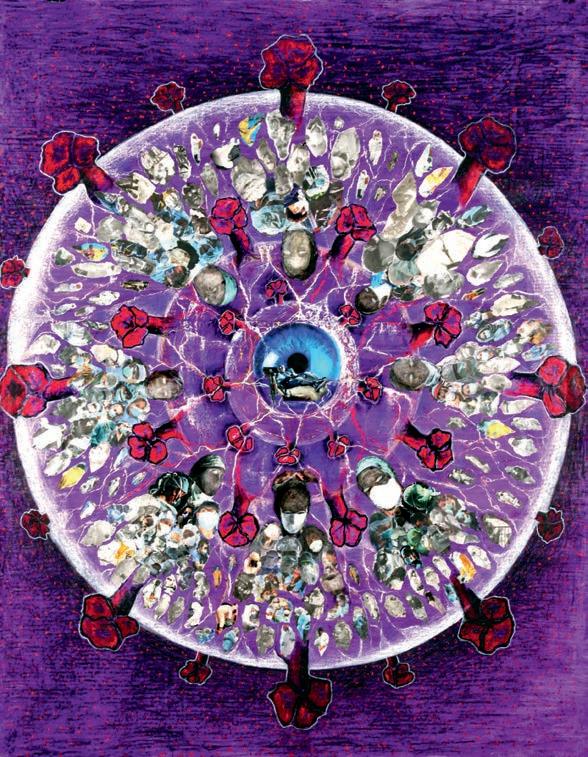

30. Corona, Fleur du Mal, 2020, 45” x 57”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

31. Minerva’s Choice for the Amazon, 2019, 83” x 87”w, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

32. Golem and detail, 2020, 62” x 106”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

32. Golem and detail, 2020, 62” x 106”h, collage, mixed media, tempera and graphite on paper

33. Home/Less/Nest, 2020, 58” x 88”w, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

33. Home/Less/Nest, 2020, 58” x 88”w, collage, mixed media and graphite on paper

Mountaindale, New York where each occupies their own building with the respective signs “Gingras Studio” and “Elozua Gallery” mounted on the facades. Here, they inhabit a world disentangled from what Lucy Lippard calls that “lousy place for artists and a lousy place for art” -the commercial art gallery system.21

By 1979, Micheline Gingras, like her Minerva, made a choice, the choice to stop exhibiting in commercial galleries. One year later, she began teaching art at Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn Heights where she was hired by the legendary founding headmaster Stanley Bosworth, a maverick like Micheline who believed in “creative chaos” and the absence of grades. In fact, some of her artwork contains scraps left on the floor after a day of cutting shapes from colored paper with her nine-and ten-year-olds (an optimal age for creativity). Well before it became fashionable for artists to practice sustainable modes of making art, Micheline considered the left-behind debris from classroom projects as material to be saved, boxed, and used in her own artwork. Five years after she retired from Saint Ann’s, she incorporated torn and cut pieces in works such as Auroras, 2022, (Image #46), What to Watch, 2022, (Image #51), and Virtual Demolicious, 2022, (Image #52).

Virtual Demolicious contains many of the traits that make her collages so visually dynamic and fecund. The title sounds made up but after a dive into virtual search engines I found

“demolicious” on Reddit, Wiki, the Urban Dictionary, but not yet canonized as a word by Merriam Webster. The title bundles associations of destruction and food into a commentary on our everyday virtual existence. Like Artificial Surveillance, 2023, (Image #54), her topic is the unease of this virtual world (a progeny of the mechanical world) that we inhabit and have increasingly become.

In Virtual Demolicious, a cut-out profile of a man in grayscale, wearing VR goggles, gazes from the edge of the top left into the center of the canvas, smack into the disc floret of a rather ungainly flower, certainly a cousin of that feisty plant in Little Shop of Horrors or a progeny of her bawdy and vicious Clown GMO, 2013, (Image #11). But the central motion of Virtual Demolicious is the tornadic spiral of hundreds of tiny, collaged houses that ascend and fly apart from the bottom of the canvas in a manner worthy of the Wizard of Oz. The background oval is painted in shades of pale blue and green, framed with colored paper fragments saved from her Saint Ann’s days. On the top right, a torn fragment imprinted with the tiny impression of a child’s hand awash in paint, appears in an outer swirl of pastels, tempera, and swatches of torn colored debris. The tornado motion of tiny houses is at once terrifying and fantastic. “A giant deadly flower, built of overlapping highways with a multitude of spiraling unstable houses at its

core, rises up, born from a divided White House. All is shaky, no confidence, will the center hold?” 22

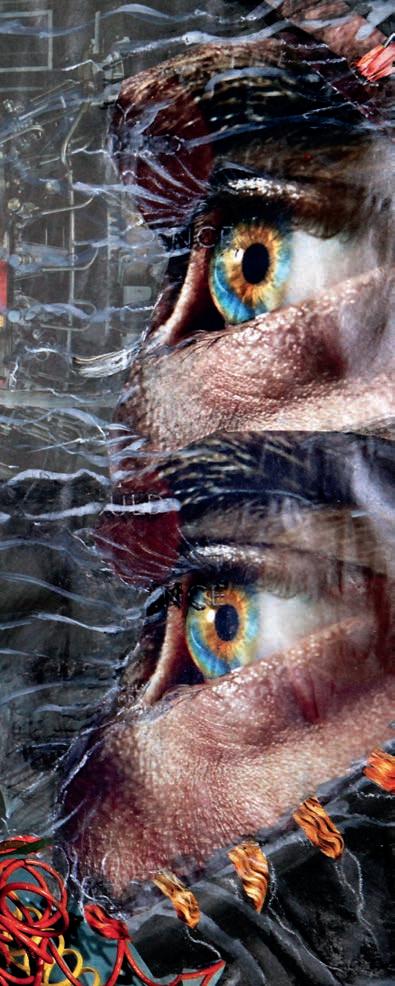

In 2016, Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. As if to predict the turmoil and craziness of his term, Micheline began one of her most political series, End Times Aftermath in 2014. In Drone Nibaba, 2014, (Image #17), hundreds of cut out cars glued into a chain, spill from an immense flower on the right as an American flag waves its patriotic message above. The line of cars rises and falls and enters the head of a cyborgish figure who looms in the center of the landscape like a 1950s film monster. On the left is what appears to be a psychotic drone-like pregnant golf cart. El Monster (Image #19) made in 2016, may even be Micheline’s ode to Trump’s election -Grover, the ever-friendly blue buffoon Muppet whose large googly eyes register nothing, looks out at a wall of collaged soldiers and immigrants. These works are dark, dense, poetic, and apocalyptic. The themes and juxtapositions range from the history of slavery, the carceral state, and racism in Amnesia, 2016, (Image #21), to the wild excesses of capitalism -It’s Raining Cars, 2015, (Image #18), with its dinosaur jaw about to swallow or take a bite out of a city scape in ruins, as a sophisticated urban white male figure wears a clown nose as he crosses onto the sidewalk. Throughout these decades of the early 21st century, Micheline dots her painted and collaged figures with bright red clown noses and even painted googly eyes. Such moments of Pop levity offset the pain and outrage that is at the center Micheline’s work.

Home/Less/Nest, 2020, (Image #33), made during the pandemic is Micheline’s masterpiece. Over seven feet wide and almost five feet high, it is a gigantic collage landscape, framed on the left with the hand painted, huge, masked head of a Covid-19 doctor, whose eyes poke out above the mask and below the surgical cap -an image of the anonymity of care as ubiquitous in the 2020s as images of gas masks were in World War I. This huge head is an image of care and terror. The landscape stretches out to the right into infinity. Grids cut into lines are re-glued into diagonals. Inequality abounds. A court building lying flat suggests the false promise of government‘s

“Equal Justice Under Law.” Tents and temporary housing rise and collapse into tumbling buildings covered with googly eyes. It is as though the city itself has become a creature of fear and chaos, its horizon line suggesting there is an end -or at least another landscape yet to be crushed by the epidemic. No other medium than collage could marry so many tactile and thematic associations of the man-made together. Home/Less/Nest is as large and complete a statement about the wreck Covid-19 made of the already unbearable structured inequalities of health care across the world, as one could imagine.

In the Pink Glass Swan, Selected Essays in Feminist Art published in the mid 90s, Lucy Lippard situates collage and other crafts such as embroidery, or hobby art, as a feminist method of art making. “I’ve always claimed the collage aesthetic…is particularly feminist. Collage is about gluing and ungluing. It is an aesthetic that willfully takes apart what is or is supposed to be and rearranges it in way that suggest what it could be.”

23 Lippard was writing in that threshold moment of the mid 90s when digital technology (computers, the internet, iPhones, and AI) had yet to colonize humanity’s ability to pay attention. At that time “interruption” had not become the pathology of everyday experience -a point that is important in Micheline’s choice of collage as her medium from 2008-2023 where she used “political consciousness as a glue with which to get the pieces into some sort of new order.” Although politics “have never really been a specific interest of mine,” as mentioned in the opening, the 2008 financial crisis created a level of anxiety in Micheline that prompted a return to collage, to create theatrical tableaux confronting the “overload of my fears.” 24

Lippard’s statement linking collage in an existential sense with feminism is present in Hannah Höch’s legendary collage, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany,” (1919-20). The ruthless social commentary on the hypocrisy and bloat of Weimar Germany is made “through the lens of gender…She chooses to give specifications, such as kitchen knife and beer-belly, to make

it clear that this piece is social commentary regarding gender issues in post-war Germany… [S]he carefully pieced all these clippings back together in a way that made sense to her, and … served her purpose of critical examination.” This simple act of finding a way to make critical art “that made sense to her,” is the essence of collage as a choice.25

Collage challenges notions of wholeness, unity, and narrative authority, as exemplified in the dance, performance, and films of Yvonne Rainer. Claimed in 1979 by feminists before she was ready to sign on, Rainer went on to produce a series of films, most notably Journeys From Berlin (1980), The Man Who Envied Women (1985), and Privilege (1990) that drilled into and imploded the codes of the “male gaze” and classical Hollywood, using collage and disjuncture; conflict, contradiction, and dissonance rather than codes of classical Hollywood cinema with its ontological structure of the male gaze. Collage as a method and a philosophy is the art of making sense with a difference. Collage has changed hugely over the centuries, and in our present era of Photoshop and Internet memes, the words “cut and paste” are more likely to call to mind a computer keyboard than glue and scissors. In this sense, collage is “a way of thinking,” as Louise Nevelson described her use of collage in 1975 when speaking about her sculptures.26 Or, as the artist May Stevens, puts it, “One central motivation behind my use of collage is that I want to disrupt the usual, dominant way of seeing and thinking about images.” 27 Even Barbara Kruger, an artist who as removed from art as craft put it, “I make a very personal collage. I throw all kinds of things into it. Memories, history, bad television, Decoder Ring.” 28 For Zarina Hashmi, an Indian American artist who creates paper collages in addition to prints and sculpture, collage is, “…about layering, trying to get memories to speak to each other. Just seeing an image can trigger a flood of memories, associations. Even with my collages -very simple ones using magazine photos -you start building stories in your head from the juxtapositions.” 29 Collage for Micheline Gingras is a moment of choice, “a way to talk back to the media,” and work through the universal fears and anxieties of our violent, sped up, over saturated media

landscape.30 Ultimately the question is, “How does one place everyday images into a language that can be read by others and possibly help someone like me, raw with anxiety.”

Consider Jacob’s Ladder, 2019, (Image #22), or Nuclear Towers, 2019, (Image #25), from the Rainbows series. Both are massive allegorical studies of two of the most frightening inventions of man: the notion of heaven and therefore of hell in Jacob’s Ladder, and, on the other hand, man’s invention of total planetary annihilation in Nuclear Towers. The rainbow is constricted and choked by abandoned rubber tires in the middle of mountains of waste. The colors signify both sentimentality and horror, as the bright colors of a summer sunset are a result of toxic chemicals in the sky. It stretches out from nature on the left and illuminates the nuclear towers threatening our existence on the right.

But these epic collaged essay-worlds are never easy to interpret. Yes, each tableaux suggests a theme -the inequity of capitalism, the housing crisis, patriarchy, climate change, racism, and misogyny. But what is the story told in Golem, Under Buddha’s Foot, 2020, (Image #32), an almost Cecil B. DeMillelike psychodrama? Like Minerva’s Choice, 2019, (Image #31) or Home/Less/Nest, 2020, (Image #33), we are in a mythic space, part urban, part apocalypse (flood and fire), and surely cosmic as we see the edge of the stars at the top right. But what is this being under Buddha’s foot, taking off like a rocket, a hybrid between ancient lore, an Oscar statue or a hawk in repose? Golem is a storied being of ancient Jewish lore, a figure born from the formless matter of mud and dust, mute yet powerful. It is an aporic figure of paradox and contradiction. Monster or Protector? A kind of dumb brute, even Wikipedia says, “Golems are not intelligent, and if commanded to perform a task, they will perform the instructions literally.” 31 This folded-winged figure, whose wings are also a sideline cape worn by football players in frigid weather, is a figure whose meaning is not steady or stable. As one looks deep into the wings, one sees fine strips of Islamic script and Greek ceramic shards collaged into the folds. The tunic is comprised of a mosaic of myriad tragedies. The city disappears like a wind tunnel, a corridor of skyscrapers

reeling from fire and floods. Part trophy, part heroic Americana football, it appears to be launching forward like a rocket into the exploding urban flux. A crude but vibrant royal blue cloudwave of tempera paint at the base of the figure adds roiling floods.

While exhibiting Golem in Mountaindale, a viewer turned to her and said, “It looks like Buddha’s foot.” And suddenly the horizontal frame of gray and blue rounded spheres painted into the sky, what might be a row of rocks, bubble biospheres, even planets, holding and framing the golem, became an image of a foot, stepping over, even preventing, the mayhem of fire and brimstone. It is a sibling emotion/motion collage to the dire X-Capsulated, 2021, (Image #37), where a pair of painted hands holds an earth globe cupped in its hands of protection, as flakes and residue of a conflagration gather in the palms. The hands hold the chaos of spilt oil, violent machines, technological overkill, strained eyeballs, that rains down from above, suggesting both the virus of Corona, Fleur Du Mal, 2020, (Image #30), and the corridors of flame that lap and climb up the inside of the tree of X-Hale, 2020, (Image #38). In the X’d series the titles perform the artist’s concept. For each title, the suffix of the words “expulsed,” “extended,” “excluded,” “exit,” “exhale,” and “exodus” is replaced by a capital X. The capital X has many associations prior to Elon Musk’s intemperate rebranding of Twitter as “X” from “X-rated” to “Generation X” and most notably “Malcolm X.” X-Odus, 2020, (Image #39), X-Hale, 2020, (Image #38), and the phenomenal X-Pulsed, 2020, (Image #34), are agents of allegory and performance. It is this graphic, synthetic (as in bringing things together) anxietyinflected storytelling that is a feature of Micheline’s strongest collages. Many of the works discussed in this catalog depend upon Micheline’s transformation of 2-dimensional flat planes into 3-dimensional, even 4-dimensional spaces as in her 2020 X’d series.

In X-Odus, 2020, (Image #39), an enormous gyrating storm of cut paper pieces is glued onto the surface, positioned to the rhythm of a hurricane cyclone unfurling across a weather map. This ball of discordant energy takes up the entire space

on the left-hand side of the canvas. The eye of the hurricane evolves from color fragments that circulate, unfurling into a slice of rope from a magazine image. The outer rings of the hurricane blend into black and white, merging with the tonality of the background. The turbulence unfurling escapes into a forest of white ghostly trees and fleeing animals of inverted tonality. By replacing the “ex” of “exodus” she both addresses and denudes the word “exodus” of its Christian-Judeo connotations.

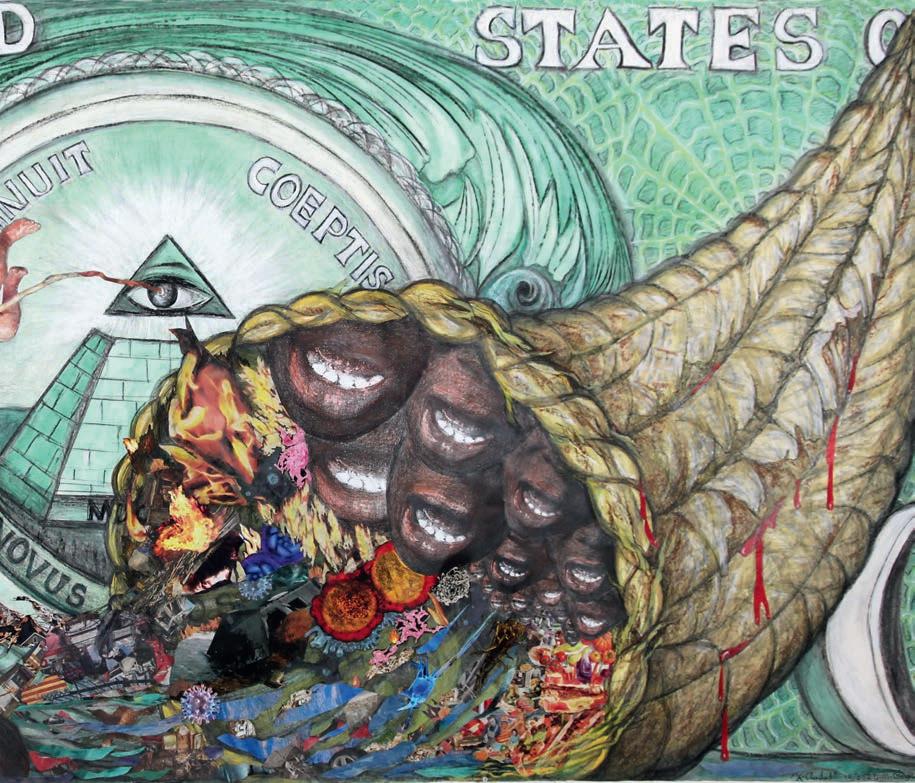

X-Cluded: Poverty in America, 2020, (Image #36), is an epic 47”h x 94”w caricature of the reverse side of an American onedollar bill emblazoned with its Masonic pyramid topped by the eye of God. The dollar bill is a large painted cornucopia pasted onto a tongue-in-cheek one-dollar bill that spews repetitive images of a Black man’s mouth falling out of the cornucopialips parched and teeth showing, the image plays into racist stereotypes even if her intent is to comment on the inequities of racism. But breaking apart of stereotypes and the construction of monsters abounds in her works, from the appearance of the pop culture monster in El Monster, 2016, (Image #19), waving as the world tumbles behind it, to the “dance of the twelve betraying apostles” that constitute the haunting series titled Clowns, (2013).

While the theatrical tableaux are cinematic in their scope and narrative ambitions, more essay than pictorial scene, Clowns are truly performative and horrifying. Clacking and sputtering at the viewer, with faces made of processed meat, old wires, fierce bestial teeth, they are a “visual record of their absurd manners and the guttural multitude of discomfort existing in our times.”32 They bespeak the horrors of factory farming, of “faux nationalism” with its cowboy ethos, or the “endless gluttony” of capitalism and fast-food packaging. These clowns do not sooth but point, mock, and dance like day of the dead skeletons cobbled together with slick magazine fragments. This danse macabre of “betraying apostles” is the same existential quality of our end times as the wounded and battered landscape on view in Home/Less/Nest, 2020, (Image #33), X-Hale, 2020, (Image #38), and Scared Crone with Oil

Rigs, 2023, (Image #53). One imagines a scene of these clowns bounding about the beach where Scared Crone with Oil Rigs, 2023, (Image #53), stands.

Along with the tempera works of the Inner Mysteries series, (2021), Scared Crone with Oil Rigs, is Micheline’s most optimistic imagery. Here we interact, with an allegorical three-dimensional woman/crone, an assemblage of trash (plastic ribbons, wire, and garbage bags) all movement and emotion, standing against the tiny image of an extended hand rising in a blue sea. The crone is triumphant, even defiant though she appears in a crucified pose. The conviction with which this woman stands is bold, upright; it exceeds the frame of the canvas. It is an image not of chaos and destruction but resilience and forward movement. There is also an unintended connection between works like the Clowns, Doom vs. Boom, 2022, (Image #47), or In Trust, 2020, (Image #26), with one of those other inventions of 20th century modernism -the calligramme -the name Guillaume Apollinaire gave to his 1918 book of poems Calligrammes: Poems of War and Peace. A calligramme is where the words, or in Micheline’ works, the cut scraps of magazine imagery, are arranged in an image that relates thematically to the content.

The most famous of Apollinaire’s calligrammes, and one that recalls High Anxiety On Wheels, (2019), is Apollinaire’s Eiffel Tower or Salut monde, (Hello World). Here in a similar moment of modernist invention as the one that produced the BraquePicasso collages of 1912, Apollinaire arranges the words and typography of his poem to mimic the iconic shape of the Eiffel Tower.

My association of Micheline’s collages

with Apollinaire is more than formal. Apollinaire wrote his calligramme poems between 1913 and 1918 -a teeth-rattling moment of invention in the history of high Western Modernism. Just as Micheline’s use of collage, tempera, and pastel is her way of working through her daily anxiety about 21st century media’s portrayal of current events, Apollinaire’s poetry chronicled his experiences of urban life, and artistic experimentation during World War I. Poems of reflection, they were written when war and an epidemic were strangling the world, much like today when we drown in images of distress, violence, and annihilation. If as Lucy Lippard tells us “collage is born of interruption,” then Violent Beauty is Micheline’s record of reckoning and thinking through the current historical interruptions. But even her wholes -the many storied collage essays on injustice during Covid-19 or the housing boom in her area of Brooklyn Heights and Dumbo, do not tell us what to think. They are invitations that “ruffle at taxonomy” 33 in order to build new worlds.

So, I conclude this essay invoking the many ways Micheline ruffles at taxonomies and invents her own tradition of art history. Initially, when I asked Micheline and Raymon to describe her work, they responded with a twinkle in their eyes, “It’s Neo-Faux Naïve.” This off-the-cuff remark is a well-deserved send-up of art history’s tendency to name movements that artists rarely identify with. Certainly, it is not surprising that left: Guillaume Apollinaire, Eiffel Tower, 1912, calligramme, published in book of poems “Alcools” 1913; above: High Anxiety On Wheels, 2019, collage, mixed media, graphite, 36”w x 56”h

Micheline, who has resisted conventional categories has found the place “where I meditate, questioning rules that keeps blood slowly dripping, one human drop at a time.” 34 Violent Beauty is a paen to this human and humane blood and sweat of Micheline Gingras, our Minerva of Mountaindale (and Brooklyn Heights), a collector and healer of life’s spiky shards.

…history has taught us that in every moment, one needs to surmount the waves, high or low as they come. Should we just close our eyes, fatigued by it all, or do we sleep until the nightmare is over. No answer here because there will always be waves to contend with. I want to build bridges over the waves.35

1 Lucy Lippard, The Pink Glass Swan (New Directions, 1995). 168

2 Micheline Gingras, Mis/Representation (Meltdown), 2008-10, iBook, self-published, 2017

3 https://michelinegingras.com/painting/mechanical-hand/

4 Mechanical Hand, 48”w x 96”h, 3-D sculpture, masonite, oil and brass.

5 Micheline Gingras, Poetry of the Mechanical Hand, iBook, selfpublished, 1997

6 Scott McDonald, “Walking Woman Works, 1961-67,” Artforum May 1984, https://www.artforum.com/events/michael-snow-walkingwoman-works-1961-67-225575

7 William D. Case, “Infinity Plus One,” Arts Magazine, Pg. 63, September-October, 1972

8 See: "Pictures Generation," Museum of Modern Art, https://www. moma.org/collection/terms/pictures-generation; Douglas Eklund, "The Pictures Generation," Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Essays, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October, 2004, https:// www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pcgn/hd_pcgn.htm.

9 Micheline Gingras, Mis/Representation (Meltdown), 2008-10, iBook, self-published, 2017

10 The bodies of work are: Mis/Representation (Meltdown) 200810; Send Back the Clowns: “Qu’est que c’est un clown?” 2013; End Times/Aftermath 2014-17; Rainbows 2017-19; Malaise 2018-20 ; X’d 2020; Inner Space Mysteries 2021; Anthroposes 2022-23

11 Micheline Gingras, In conversation with author, 2022

12 Micheline Gingras: Selections: 2008-2021, iBook, self published, 2021

13 Email communication with the artist, January 21, 2024

14 Ibid

15 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/ art/collection/search/490612

16 Micheline Gingras, text from The Eclipse in My Her(ly) Work, 19571993, iBook, self-published, 2022

17 Dr. Cole Collins, Exhibition Review: "'I'll Just Get Them A Big Bag of Scraps: Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage, Scottish National Galleries of Modern Art, Edinburgh, " CRN (Collage Research Network," October, 2019, https://collageresearchnetwork. wordpress.com/2019/10/19/exhibition-review-ill-just-get-thema-big-bag-of-scraps-cut-and-paste-400-years-of-collage-scottishnational-galleries-of-modern-art-edinburgh.

18 Lippard, 1995, 168

19 Arthur Danto, “ The Art World,” The Journal of Philosophy Vol. 61, No. 19, American Philosophical Association Eastern Division SixtyFirst Annual Meeting (Oct. 15, 1964), pp. 571-584 (14 pages) Published By: Journal of Philosophy, Inc.

20 Jarrett Earnest, Valid Until Sunset ( MATTE Editions, 2023), 121

21 Lippard, 1995, 5

22 Micheline Gingras, Anthroposes, book prototype, self-published, 2023

23 Lippard, 1995, 25

24 Micheline Gingras, In conversation with author, 2023

25 Utopia/Dystopia: Examining Art of World War I, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife,” https://utopiadystopiawwi.wordpress.com/dada/ hannah-hoch/cut-with-the-kitchen-knife/

26 Sam Reilly, “Stick ‘ em up! A surprising history of collage,” 1843 Magazine, July 24, 2019. https://www.economist. com/1843/2019/07/24/stick-em-up-a-surprising-history-of-collage

27 Quoted in Gwen Raaberg, “Beyond fragmentation: collage as feminist strategy in the arts.” Mosaic: A journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature, vol. 31, no. 3, Sept. 1998, pp. 154

28 Quoted in Raaberg, 1998

29 Zarina Hashmi Interview by Rebecca Bengal. Vogue, October 21, 2021

30 Discussing Polarity (1974) Micheline says, “I was always interested in collage as a quick expressive form of sketching. In addition, as a collector of media images, it offered me a way to “talk back” to the media.”

31 Wikipedia, “Golem,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golem

32 Micheline Gingras: Send Back the Clowns: “Qu’est que c’est un clown?” iBook, self-published, 2013

33 Martha Rosler, Irrespective, (NewYork: The Jewish Museum, 2018)

34 Micheline Gingras, Anthroposes, book prototype, self-published, 2023

35 Micheline Gingras, Mis/Representation (Meltdown), 2008-10, iBook, self-published, 2017

34. X-Pulsed, 2020, 44” x 64”w, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

34. X-Pulsed, 2020, 44” x 64”w, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

35. X-Tended, 2020, 60” x 70w”, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

35. X-Tended, 2020, 60” x 70w”, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

36. X-Cluded, Poverty in America, 47” x 94”w, 2020, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

36. X-Cluded, Poverty in America, 47” x 94”w, 2020, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

37. X-Capsulated, 2021, 39” x 50"h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

38. X-Hale, CA, 2020, 47” x 89”h, collage with mixed media

39. X-Odus, 2020, 24” x 36”w, collage with mixed media on canvas

39. X-Odus, 2020, 24” x 36”w, collage with mixed media on canvas

40. Enclosed Universe, 2021, 39” x 50”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

40. Enclosed Universe, 2021, 39” x 50”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

41. Body Within a Face, 2021, 50” x 53”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

41. Body Within a Face, 2021, 50” x 53”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

42. Mystic Brain, 2021, 50” x 53h”, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

42. Mystic Brain, 2021, 50” x 53h”, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

43. Intestinal Measures, 2021, 53” x 53”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

43. Intestinal Measures, 2021, 53” x 53”h, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

44. Opioid, Losing Our Bearings, 2021, 50” x 53”h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

44. Opioid, Losing Our Bearings, 2021, 50” x 53”h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

45. Body in Hand, 2021, 54” x 60h,” tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

45. Body in Hand, 2021, 54” x 60h,” tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite

46. Auroras For Sale, 2022, 35” x 59”w, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

46. Auroras For Sale, 2022, 35” x 59”w, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

47. Housing, Boom Vs Doom, 2022, 40” x 50”h, collage, tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

48. Cat People Exist, 2022, 41” x 59”w, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

47. Housing, Boom Vs Doom, 2022, 40” x 50”h, collage, tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

48. Cat People Exist, 2022, 41” x 59”w, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

49. Aging Cat, 2022, 42” x 69”h, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

50. Monkey Puck, 2022, 50” x 59”h, collage with tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

51. What to Watch, 2022, 46” x 54”h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

52. Virtual Demolicious, 2022, 35” x 54”h, collage, tempera, pastels and graphite on paper

53. Scared Crone with Oil Rigs, 2023, 51” x 91”w x 9”d, oil on canvas with mixed media

54. Artificial Surveillance, 2023, 24” x 36”h, collage, tempera and graphite on paper

54. Artificial Surveillance, 2023, 24” x 36”h, collage, tempera and graphite on paper

We are minerals in the earth’s entrails.

Kevin Birmingham, 2023

Ancestors

Ant colonies achieving formation

Heads of past generations

Symbolical ancestors of civilization

My homage of togetherness

People I met in my life, heard of

Read about, close or distant

Past, present, family, migration, lineage

Everyone linked in chains to humanity

Tragic and joyous stories reside On the fresh border of my art

A simple structure, no floor

Exiting ghosts that circulate

Feelings of shards

In material beams

Of syllables learned in school Church, attended

Recitations by us strangers

Words like sin, shame, or duty

The green snake of yesterday

His agile knowledge permeates onto us

Running wild my spiritual imagination

I meditate as eyes appear in multitude

Flesh, organs and blood composed

From airy to viscous endurance

By osmosis

Grateful to the ancestors

By water often beautiful

By fire always violent beauty

Micheline Gingras, 2024

55. Ancestors , 2023, 53” x 104”h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

55. Ancestors , 2023, 53” x 104”h, collage, tempera, pastels, coloring pencils and graphite on paper

Micheline Gingras (b.1947, Québec City, CA) is a visual artist working primarily in painting, collage, drawing and photography. She received her MFA from l’École des Beaux-Arts du Québec, moving to New York City in 1970. She had major solo exhibitions at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Montréal, Le Centre Culturel du Canada, Paris, FR, and London, GB, Galerie Sauvegarde-Desjardins, Montréal, and Kornblee Gallery, NYC. She received two grants from the Canadian Art Council in Painting, 1973 and 1974, and from Le Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Québec. She has also participated in numerous group exhibitions including the Everson Museum of Art, Yale University Gallery, Mint Museum of Art, and American Craft Museum, NY, among others. Micheline taught art for 37 years at Saint Ann’s School, Brooklyn, and now divides her time between the city and her studio in Mountaindale, NY.

www.michelinegingras.com

Raymon Elozua, is a trans-disciplinary visual artist working with steel, ceramic, glass and photography in Mountaindale, the Catskill region of New York.

Catalog photography: Raymon Elozua

Thyrza Nichols Goodeve is a writer, editor, and educator who lives in Brooklyn Heights. Senior Art Editor of the Brooklyn Rail from 2017-2019, she teaches at the School of Visual Arts.

Wedding photo, 1937

Rosée Dubois and Roméo Gingras, were “salt of the earth” parents and excellent role models. My brother, Gilles, who challenged me to actively choose my future, as well as my other two brothers, Jean-Guy, Michel, and three sisters, Gisèle, Huguette, and Doris, who supported me in my often unorthodox processes of creation.

Ms. Blais, my 11th grader art teacher at Marie de L’Incarnation School in Qc., for believing in my talent and encouraging me to explore it.

Duncan DeKergommeaux, director of the Canadian Art Gallery, Expo Montréal, 1967, for giving me the chance to participate in the world of art as his assistant.

Canadian Art Council, for acknowledging my efforts in visual art, granting me two scholarships in order to achieve my early paintings in 1973 and 1974.

André Juneau, curator at the Québec Museum, who gave me my first solo show at the museum with “The Mechanical Hand” in 1973.

Suzanne Beaulieu, my sister-in-law, for her help translating my texts from English to French.

Leslie Ferrin, Ferrin Contemporary Gallery, for her encouragement.

Thyrza Goodeve, for her intuitive and enthusiastic way with words, who possessed the clarity to organize and analyze my art for this catalog.

Ethan Crenson and Amanda Alic, Red Shift Design, who made this catalog a reality and were instrumental for the elegant design of my website.

Stanley Bosworth (1927-2011) and, Marsha Liberty (1947-1995), for giving me the freedom to share my joie de vivre Québécoise of touching souls as an art teacher at Saint Ann’s School in Brooklyn for 37 years.

Lucy Mahler, my dear and spirited friend with whom I shared many playful visions.

Raymon Elozua, my life companion since 1980. Together we share our dreams and creative endeavors with patience and generosity. Raymon is my bright and shining star, wonderful to behold. I cherish his loving and comforting presence in my life.