Sugar Pond Page 20 ISSUE 25 Tools on the Job Page 3 Recipes: Made in Haiti Page 16 STORIES OF HOPE FROM AROUND THE WORLD Walking With The Road to Thriving: Stories of Change in Marare and Nashisa Page 10

Tools on the Job

Handy, innovative, everyday tools PAGE 3

Look What I Made!

Children's drawings from our partner communities PAGE 8

The Road to Thriving

Stories of Change in Marare and Nashisa PAGE 10

Poverty Busters

Never too young to fight poverty PAGE 14

Recipes

Made in Haiti PAGE 16

Heroes of Transformation

Meet Biregeya Gerard PAGE 18

Sugar Pond

We all have blindspots PAGE 20

Voices of the Village

She's one determined girl! PAGE 23

FROM THE PRESIDENT

Food for the Hungry has a rich history of “walking with” our communities. “Walking with” is infused into everything we do. We don’t come in with a premade development plan. We tread lightly and build relationships with churches, leaders, families, listening to their needs.

To “walk with” doesn’t mean walking ahead, leading, or pulling along. It’s journeying side by side, together, so a community can thrive.

As we watch our partnered communities lead their own development journeys, amazing things happen. Gardens flourish, families learn to save and invest money, more kids enrol in school, and diseases are prevented. This growth is the sum of the hard work of each community member.

You’ll find inspiring stories of hope and hard work in the pages of this HopeNotes. You’ll get to know the faces,

the stories, and even the tools used in this giant, gritty, and glorious task of ending poverty. Thank you for being part of it.

Gratefully,

ISSUE 25

SPRING 2019

Food for the Hungry (FH) Canada’s seasonal publication, celebrating stories of hope from partner communities around the world.

Editorial: Eryn Austin-Bergen, Colton Martin, Mark Petzold, Michael Prins Design: Tyler Anaya

Contributors: Angie Bonvanie, Damaris Bravo, Kim Cruson, Jean-Mary Edouarein, Donna Fournier, Biregeya Gerard, Ben Hoogendoorn, Karen Koster, Tanya Martineau, John Page, Kari Petzold, Kristina Prins, Tyler Regehr, Calvaire Remy, Avery Sass, Andrea Smith, Eric Strom, Daniel White

Food for the Hungry (FH) Canada is a Christian, non-profit organization dedicated to facilitating sustainable, community development in order to bring about long-term transformation for those stuck in poverty.

Through project development, Child Sponsorship, and emergency relief, FH Canada strives to relieve all forms of poverty—physical, spiritual, social, and personal.

Our Purpose:

To end poverty, one community at a time.

Our Promise:

To graduate communities from poverty in 10 years.

84.6% Building Sustainable Communities

10.8% Invested to Generate Income

4.6% Administration & Running Costs

Shawn Plummer President & CEO

As a Certified Member of the Canadian Council for Christian Charities, FH Canada meets the stringent standards set by the CCCC for accountability and organizational integrity.

CHARITABLE REGISTRATION NUMBER: 132152893RR0001

FH CANADA

1-31741 Peardonville Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 1L2

604.853.4262 | TF 1.800.667.0605

604.853.4332 info@fhcanada.org | www.fhcanada.org

T

F

PAGE 3 PAGE 10 PAGE 23 PAGE 16 2

"MENCHA" (Sword)

The mencha is a standard tool used in Ethiopian households. It’s used to cut bananas from a tree, trim grass in the front yard, and even protect the family from wild animal attacks. The mencha’s curved blade gives it greater cutting power than a regular straight blade, making it more versatile for day to day use.

Ethiopia

Tools on the job

Ethiopians use curved swords to fend off wild animals. Cambodians use doublehandled saws to make felling trees easier. Whatever the need, men, women, and children in our partnered communities have a tool for the task. Check out some of the tools they use everyday!

"POU THAO & DEAK KOOL"

(Axes & Nails)

Axes can be used instead of hammers to drive nails into wood. For many Cambodian builders, having a tool that can both make adjustments to the wood (sharp end) and drive nails into the wood (blunt end) is a major point of convenience. It makes the individual an independent worker.

Cambodia

FHCANADA.ORG 3

4

Farmers worldwide are known for their ingenious, makeshift contraptions. Farmers in Cambodia are no exception. This walking tractor, translated literally, “cow machine,” helps Cambodian farmers plow their fields quickly and efficiently. Farmers in Cambodia have used it in rice fields for nearly 20 years. But it also has a second use—transportation. Tires can be replaced and the kor yun can be attached to a cart.

Cambodia

The ipanga is a common household tool used to cut through pretty much anything. Got a dead tree in the yard that needs to come down? Done. Have shrubs or bushes to prune in the garden? Can do. Need to chop up fruit to feed your two-year-old? There’s no tool more versatile than the ipanga.

Rwanda

The koto is used in Ethiopia to chop and harvest wood. It’s a versatile tool, helpful in splitting logs, and cutting sticks and twigs. The koto is important to every member of the family; mothers, fathers, and children alike use it often daily to collect wood to fuel the family's kitchen and heat their home.

Ethiopia

For many families in rural Bangladesh who can’t access clean water nearby, the kolosh is indispensable. Families use it daily to collect and store water for use at home. The tapered neck and spout serve to keep water in, while also making pouring easy. They’re a dime a dozen in rural areas and almost every family has one.

Bangladesh

"IPANGA" (Machete)

"KOTO" (Axe)

"

KOR YUN" (Walking Tractor)

FHCANADA.ORG 5

"KOLOSH" (Water Pot)

"ROR NA THNOU" (Wood Saw)

Wood saws are a relief for those who commonly use axes to cut down trees. Two people work together, each grasping a handle at opposing ends of the saw to quickly rip through a tree. These saws empower women in particular, to engage in the lucrative work of tree cutting.

Cambodia

"BAK

(Carrying Stick)

Simple and intuitive, the bak is a long stick used to manually haul large loads. In Bangladesh, the bak is commonly used with large baskets to carry fish, food, or other materials from place to place. It makes it possible for multiple people to carry goods together, lightening the workload for everyone.

Bangladesh

The igunira is a multi-purpose material used during harvest time and in construction. As a tough fabric, it’s a convenient way to bundle vegetables and other crops for transport. Slow to biodegrade, it’s also used to keep dirt and other materials in place when building outdoor structures like keyhole gardens.

Burundi

The shitiyo is a basic tool used all over Rwanda. Where would we be without the good ‘ol shovel for all manner of holes? Builders love it for moving gravel and sand and mixing it with cement. Farmers love it because it moves soil and manure from place to place, as well as planting fruit trees or tree lines to combat erosion.

Rwanda

"

"SHITIYO" (Shovel)

"IGUNIRA" (Plastic Tarp)

6 ISSUE 25

7

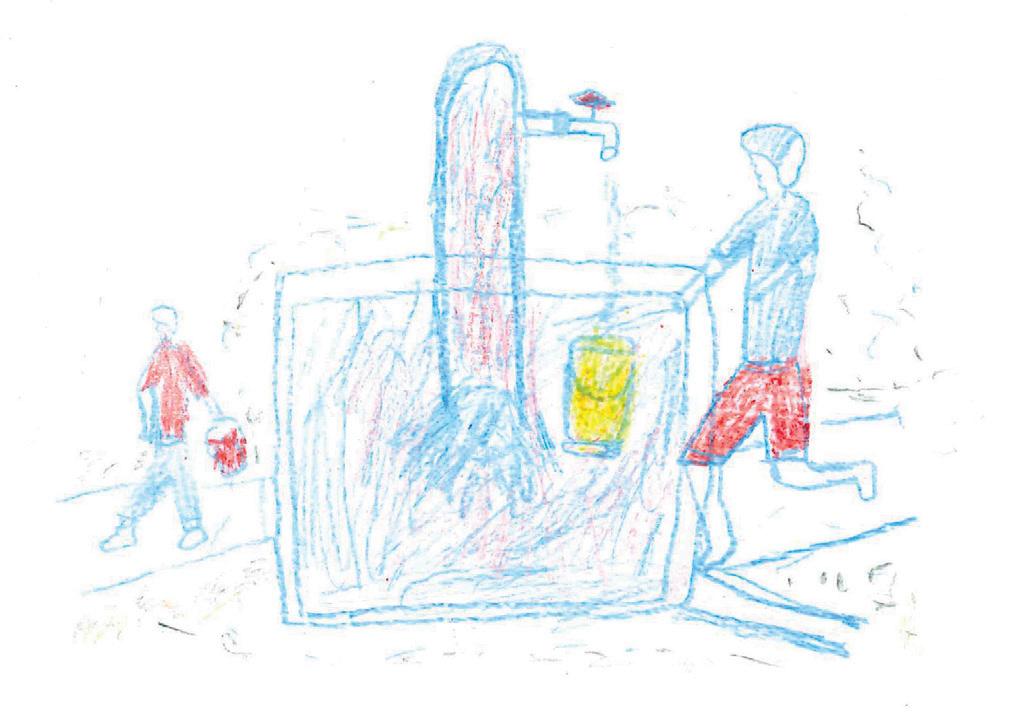

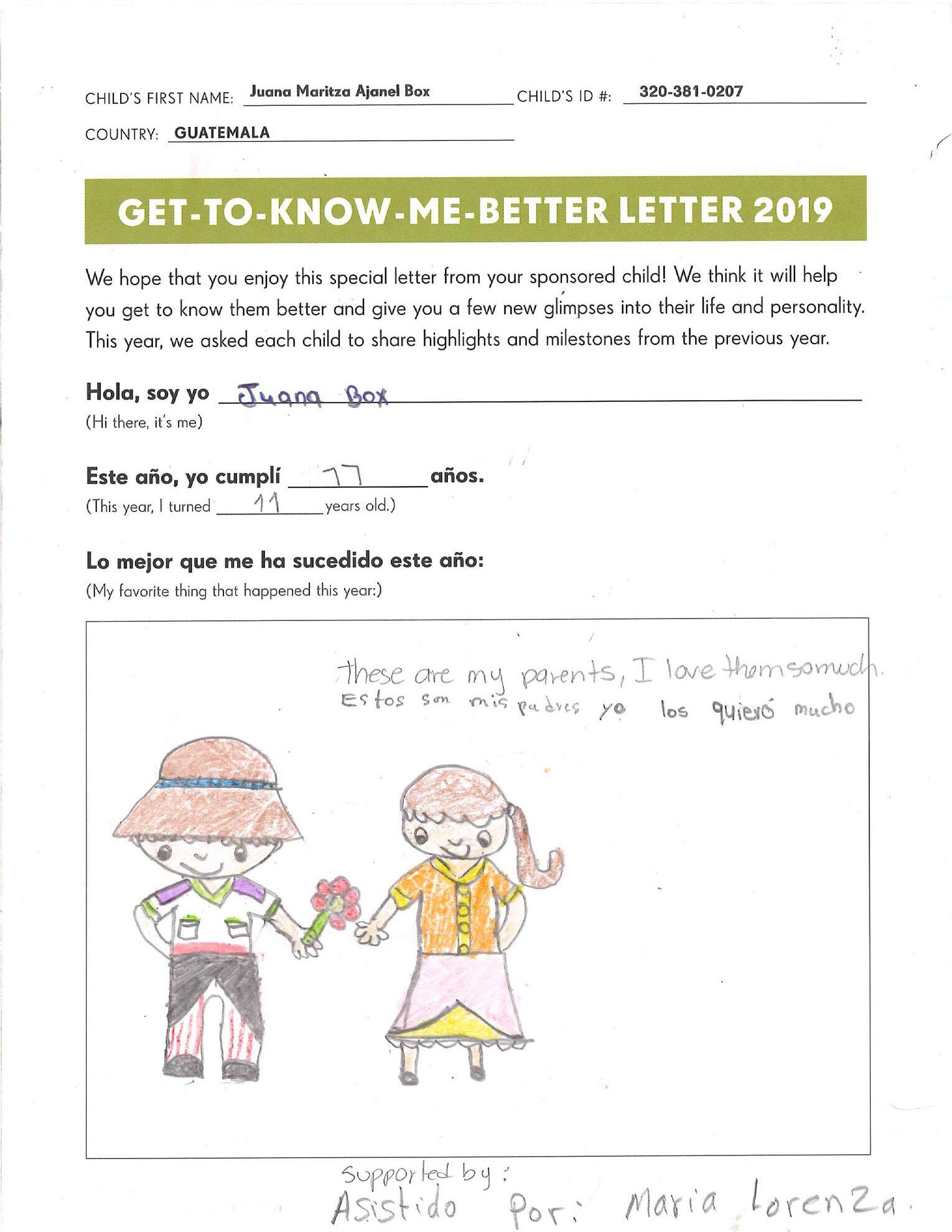

Look Wh at IMade!

"I improved at cricket."

Ariful Age 15 Bangladesh

I love them so much."

Juana Age 11 Guatemala

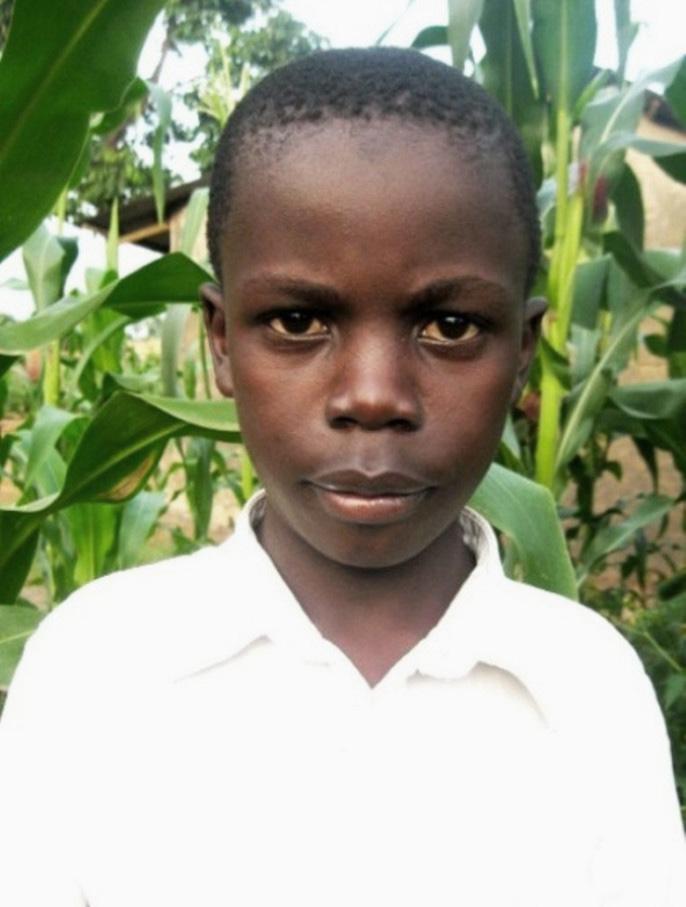

Elie Age 14 Burundi

"I sold my hen and bought my boxes. I am a choir member at shcool!"

Christine Age 17 Uganda

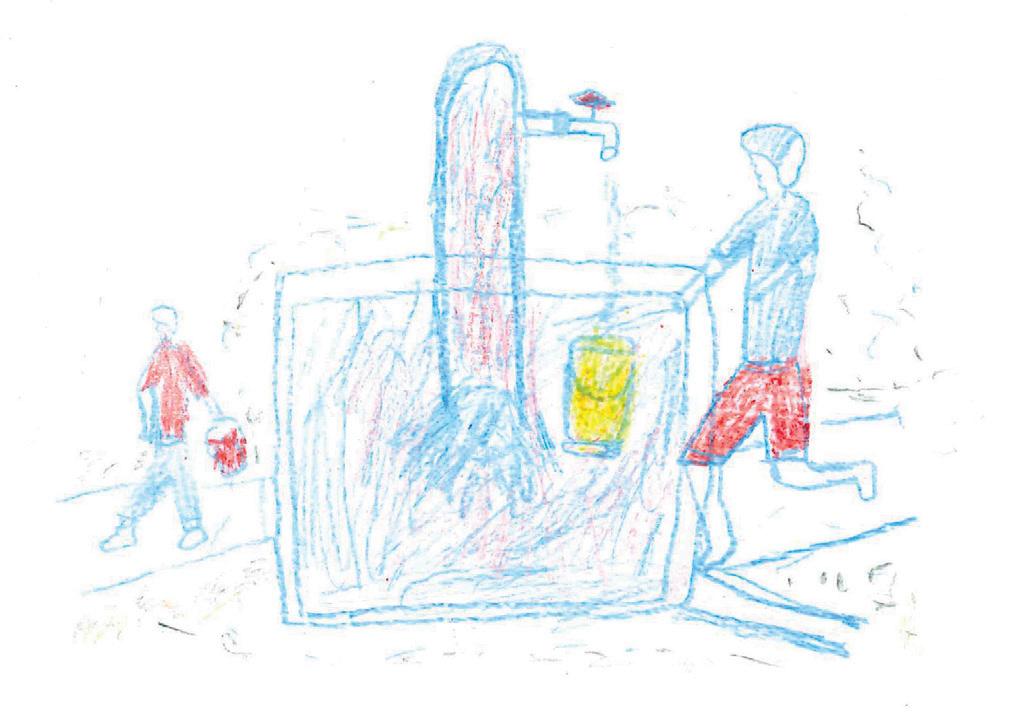

"Food for the Hungry contributed for us a water source."

8 ISSUE 25

"My favourite thing this year!"

"I like to drink milk from our cow! FH is building two more classrooms from your support, thank you."

Bees and a flower

Pascal Age 12 Rwanda

GIFTS FOR CHANGE 2019/2020 EDITION G IFT

UIDE

Ronald Age 13 Haiti

G

"[My family] received the bamboo from FH!" Mom Sery Age 14 Cambodia

"I

joined [the children's club] to draw pictures!"

www.fhcanada.org/gifts These KIDS GOAT talent! Made possible by Gift Guide purchases! This particulardrawing is UDDERly inspired! 9

Sreikhuoch Age 9 Cambodia

The Road to Thriving:

Stories of Change in Marare and Nashisa

It hasn’t always been an easy road for the communities of Marare and Nashisa. For decades, these two villages in Mbale, Uganda, struggled to survive. Political unrest, war, and human rights abuses shaped the way people approached life, and it significantly slowed community development. Like most rural communities in Uganda, Marare and Nashisa dealt with a struggling economy, sanitation and hygiene problems, and a growing HIV/AIDS crisis.

In 2009, Food for the Hungry started walking alongside these two communities. The people of Marare and Nashisa were eager to begin their journey from stuck to thriving. Since 85 percent of the population were subsistence farmers, FH knew the key to success would be helping them farm in the most efficient and lucrative ways possible. By holding agricultural training workshops and providing seeds, seedlings, and livestock, FH staff worked with the people of Marare and Nashisa to improve their livelihoods.

But they didn’t stop there. New teachers and classrooms brought thousands of children a quality education. Cooking workshops helped families create diverse, healthy diets. Communities dug and maintained wells together, preventing disease and giving everyone better access to water.

After ten years of working together, it is now time for Marare and Nashisa to graduate from their partnership

Written by: Colton Martin

with FH. The communities are confident that they are ready to move forward independently and that they can maintain their new way of living.

The difference after ten years is apparent. Each leader, child, or farmer has a story of change. Here’s what their thriving looks like.

Musa Finds Hope

“I was an orphan in Grade 5, a small boy, who seemed to have no hope of what my education would be like. I was depressed, I had no father whom I could depend on for my future opportunities.” -

Musa

Musa couldn’t remember what hope felt like. He was an orphan for the bulk of his formative years. He fought depression

10

Musa in Grade 5. Musa today.

Children of Nashisa Primary School can hardly contain the thrill of harvesting corn from the school garden!

The difference after ten years is apparent. Each leader, child, or farmer has a story of change.

and hopelessness. His Canadian Sponsor would write him to send encouragement. “She told me how she loved me and wrote words of hope,” Musa explains.

Thanks to counseling sessions and guidance from FH staff, Musa was able to overcome negative feelings of hopelessness. Despite being an orphan, Musa was encouraged and motivated to stay in school and take life head-on.

Today, Musa is focused on becoming an accountant. “This education has given me hope,” he says with a smile.

Loy Coaches

Mothers died in childbirth. Children died from preventable illnesses. The communities of Mbale suffered because of inadequate healthcare.

“Before FH, health messages were only heard at the clinics. But now, we hear them at the courtyard and at the well,” explains 42 year old Loy, a faithful member of her women’s health group. She’s noticed how common health advice and practices have become thanks to FH—and it’s making a difference in Mbale. “Now people value their lives by going to the hospital willingly,” she says. Children are eating better and are being immunized. Childbirth is now a much safer process.

BEFORE only 38% of students passed, NOW

85% PASS

BEFORE 304 enrolled NOW

632 ENROLLED

BEFORE most families trekked daily to unprotected water sources

BEFORE 588 enrolled NOW

1170

MARARE NASHISA ENROLLED

91% NOW

of families have access to clean water

MARARE NASHISA BOTH

BEFORE BEFORE NOW OF HOMES had their own latrine

47% 38%

OF HOMES had their own latrine OF HOMES have their own latrine

90%

Loy has set up a hygiene station outside her house. It’s one of the practices she’s picked up from her Cascade health group.

11

Deborah Celebrates Ester Leads

Ester has natural leadership potential and a savvy business sense, but there weren’t many opportunities for her to thrive in Mbale. “Women were never recognized as leaders,” she explains.

When FH started walking with Marare and Nashisa, they held workshops that taught leadership, listening, values, and restoring relationships. This broadened the definition of leadership and who could be a leader.“I did not know that the church would ever allow women to be leaders. I did not know that I would be a leader!” exclaims Ester.

Ester now leads groups in her church. “I started using leadership skills in my position as a woman leader. I even sit on the church council at the parish level.”

She also runs her own small business. “Since 2015, I attended trainings with FH and I’ve used what I learned on money and savings to start the business I now have.”

91% NOW

Deborah reflects on her life before FH came to Mbale. “Before my involvement with FH, my life was characterized by domestic violence, distance from the church, and involvement in witchcraft. I had no savings plan. I depended on my husband for everything.”

After ten years of partnership with FH, Deborah’s life is completely different. She’s taken adult literacy classes and joined savings and loans groups. “I have learned how to save, look after dairy cows, and make my own bricks for construction.”

“The biggest change is our knowledge,” Deborah explains. “We don’t have time to gossip anymore. We work, share knowledge, and develop one another.”

BEFORE 0 Savings and Loans groups existed BEFORE NOW

Savings and Loans groups are active and 98% of the community is involved in a group

93 NOW

62%

The majority of families were solely subsistence farmers have a means of income apart from farming.

Ester shares scripture with her family. She is now a leader and mentor in her local congregation.

Deborah poses for a photo with six of her children. Providing for a busy family would not have been possible without the help of Canadian sponsors.

focused on daily survival to plan for the future

families

follow a biblical worldview

Families were too

BEFORE of

claimed to

18% DISASTER RISK REDUCTION plans are in place to mitigate any future emergencies attest to experiencing change in their lives and adopting a biblical worldview

NOW 91% BEFORE 18% 12

church partners

Share in Celebrations

Ten years ago, two Canadian churches embarked on a journey. CAP Church in North Vancouver began walking with Nashisa, and Northgate Baptist in Edmonton partnered with Marare.

This new partnership meant a lot of things. It meant financial support and a new development plan. More importantly, it meant building relationships, and the churches sent teams to Uganda to get to know the families living there.

As personal ties between the communities grew, members of CAP Church and Northgate Baptist began to notice a change. Within a few years of partnership, it was evident that Marare and Nashisa were well on their way from stuck to thriving.

“In 2012, I saw the village of Nashisa for the first time. We met under a mango tree next to the partially constructed church. Only one classroom block was completed and the other building was a dilapidated structure with gaping holes in the roof... There were no latrines... It was a depressing sight.

“There are now over 1,200 children in school, more than half of which are girls. There are now 50 savings and loan groups operating which offer members a means to save and borrow to buy land, livestock, and supplies that improve their ability to earn a living and send their children to school. Cascade groups train mothers in basic hygiene and useful skills which then trickle down into the community. The dairy cow program provides nutritious milk for children and a marketable product, and the manure is used in biogas systems that are becoming more common throughout the village. We walked the fields of a young farmer who has embraced organic methods and produces a staggering quantity and variety of vegetables.

"We were privileged to play a small role in [their] journey... They have done

the work with God’s help. We celebrated with the community the transformation in the lives of men, women, and children and of the land itself. Our tears as we left were tears of joy."

— Andrea Smith, CAP Church

“It brought the grandparents a lot of excitement and pride to show the progress in the construction of their new house. Making the bricks themselves and buying the concrete mix, Prossy’s grandparents are slowly building a much bigger house for the family so they can move out of their mud hut. This brought A LOT of encouragement to the team to see that the people of Marare truly are self sufficient... The time there won't be forgotten.”

— Vanessa, Northgate Baptist

“They sang, “We will cry cry cry brother Diniz never forget us.” They sang that to each team member. They also sang 'for everything that you did for St. James School we will never for get you.' Lots and lots of tears were had by all including the children themselves.”

— Diniz Rodrigues, Northgate Baptist

Canadian congregations cheered on Nashisa and Marare from afar but throughout their partnership sent teams to see the transformation firsthand.

FHCANADA.ORG 13

CAP Church members (Andrea, pink shirt) on a visit to Nashisa.

POVERTY BUSTERS

NEVER TOO YOUNG TO FIGHT POVERTY

Written by: Colton Martin Interviews by: Eric Strom and Michael Prins

Poverty isn’t dead yet. Kids notice it. When given the exposure, they see poverty locally. And globally. Kids are often the first ones to care, to really believe that they can make a difference.

This year across Canada, children took on the mission of ending poverty. From bake sales to book sales, to hosting a “hunger banquet,” they proved that caring for those in need can be a deeply satisfying and rewarding act. They showed that we can look across the world to foreign countries and see people as our neighbours. Here are some inspiring stories of creative kids helping to end poverty!

Students Serve Food for Thought

Exploring themes of hunger can be tricky. But Angie Bonvanie and her Grade 5 and 6 students believed they could drive the message home by putting guests in a situation where their stomachs would do the thinking.

Angie and her students planned a culinary and social experience to educate banqueters about global poverty and food-related issues. They engaged Food for the Hungry (FH) Canada for help, and settled on hosting a Hunger Banquet.

Guests trickled into the Halton Hills Christian School gym. Twelve-year-old Jada waited at the door to inform them of their fate in the Hunger Banquet, assigning some attendees to a finely decorated table and multi-course dinner. Others were seated on folding chairs, eating potatoes. Most guests settled on the floor, crowded, and eating rice.

“We hope this event will be some great food for thought!” punned one student as he kicked off the event. Students even quizzed participants. Does hunger affect all people (old and young, men and women) equally? False. “I was struck by how the women go without food to give the husband and kids food, before even touching it,” commented one student.

Then came the dinner rules, including seating arrangements to dictate who was ‘rich,’ ‘middle class,’ or ‘poor.’ And one absolute imperative − no sharing food.

For the rich, it was fine-dining − complete with table-cloths, gleaming cutlery, a steak dinner, and a view from the gym stage overlooking the room. Middle class ticket holders received folding chairs, no table, and a simple meal of potatoes. Those slotted into the poor group found a spot on the cold, hard floor with little to eat and drink but plain rice and murky water.

The unsuspecting participants heard hard statistics like each year nearly 12 million children under five years old die from malnutrition or food-related illness. They learned that while hunger is often a painful symptom, poverty is bigger than a lack of food and it isn’t just about “not having stuff.” Poverty is felt when parents cannot regularly provide for their kids, when healthcare is inaccessible, or when basic schooling is unaffordable.

Through donations to the Hunger Banquet, students raised over $600 towards the work of ending poverty! They gave the funds to FH Canada and two local organizations, the Ontario Christian Gleaners and the Georgetown Bread Basket. Also at

"Poor" guests sat on the floor of the gymnasium and ate handfuls of rice for dinner.

"Poor" guests sat on the floor of the gymnasium and ate handfuls of rice for dinner.

about world

14 ISSUE 25

Students served the "rich" class a three-course meal at a finely decorated table.

The

class hopes that the conversations

hunger and poverty will be ongoing.

the event, six vulnerable children were sponsored through FH Canada—truly the icing on the cake.

“What a spectacular evening that succeeded in raising awareness,” Angie commented, “Best yet, this event created ongoing conversations in homes about what our world looks like and how God is calling us to make a difference.”

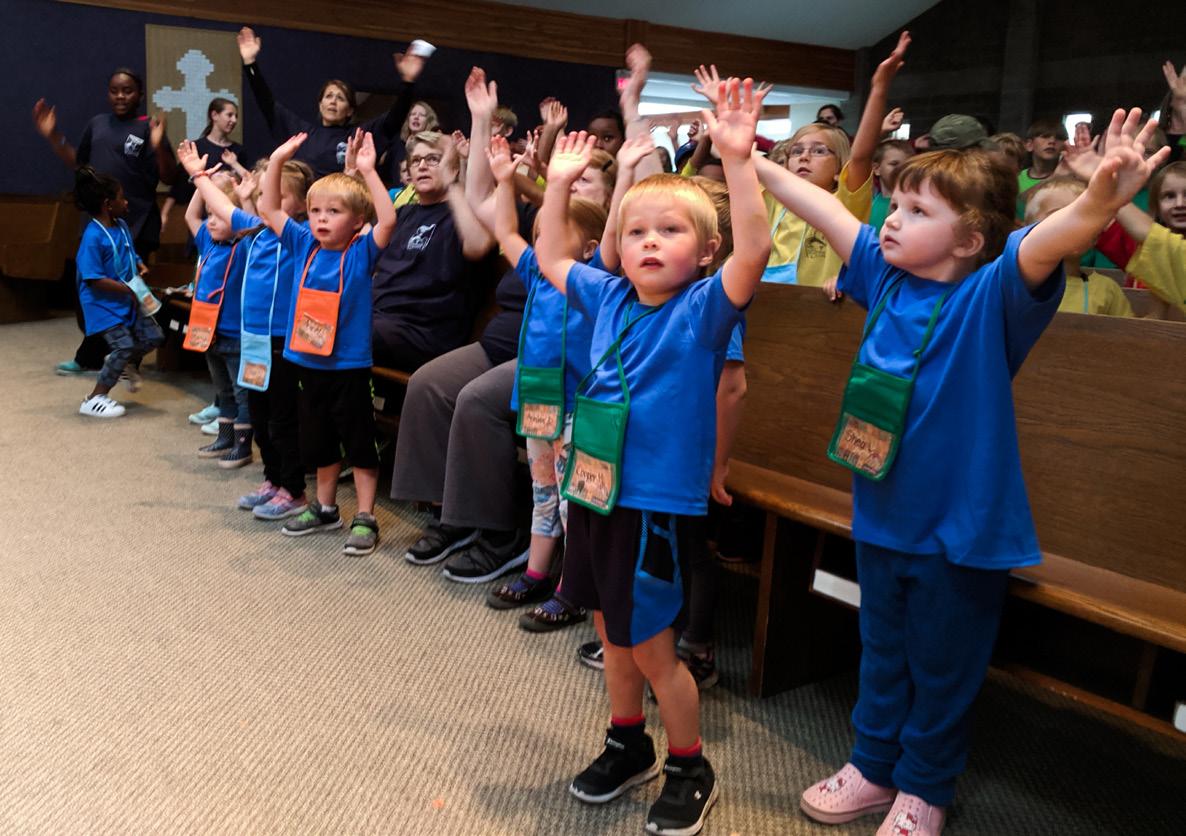

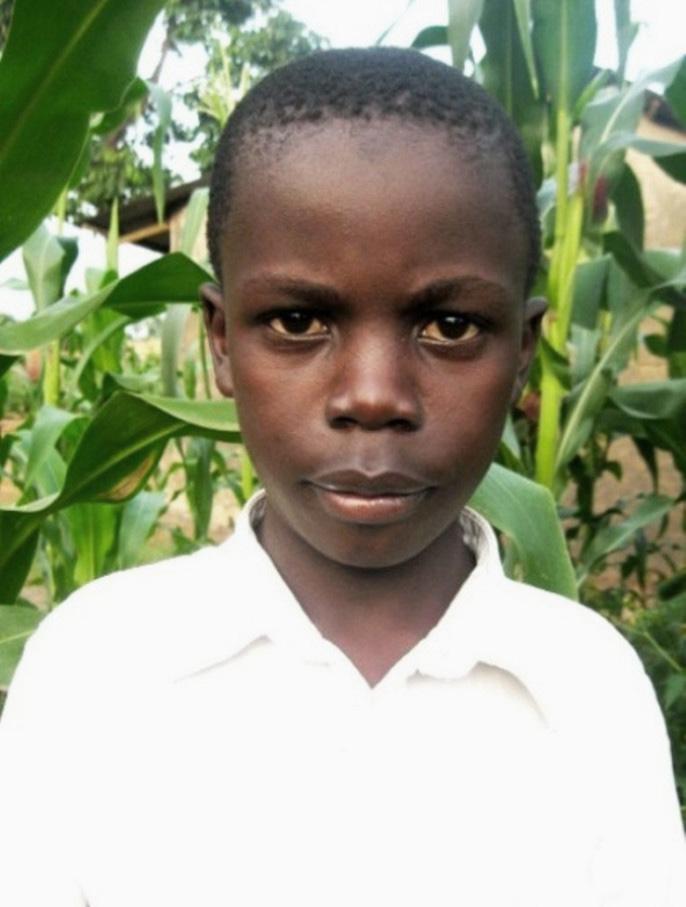

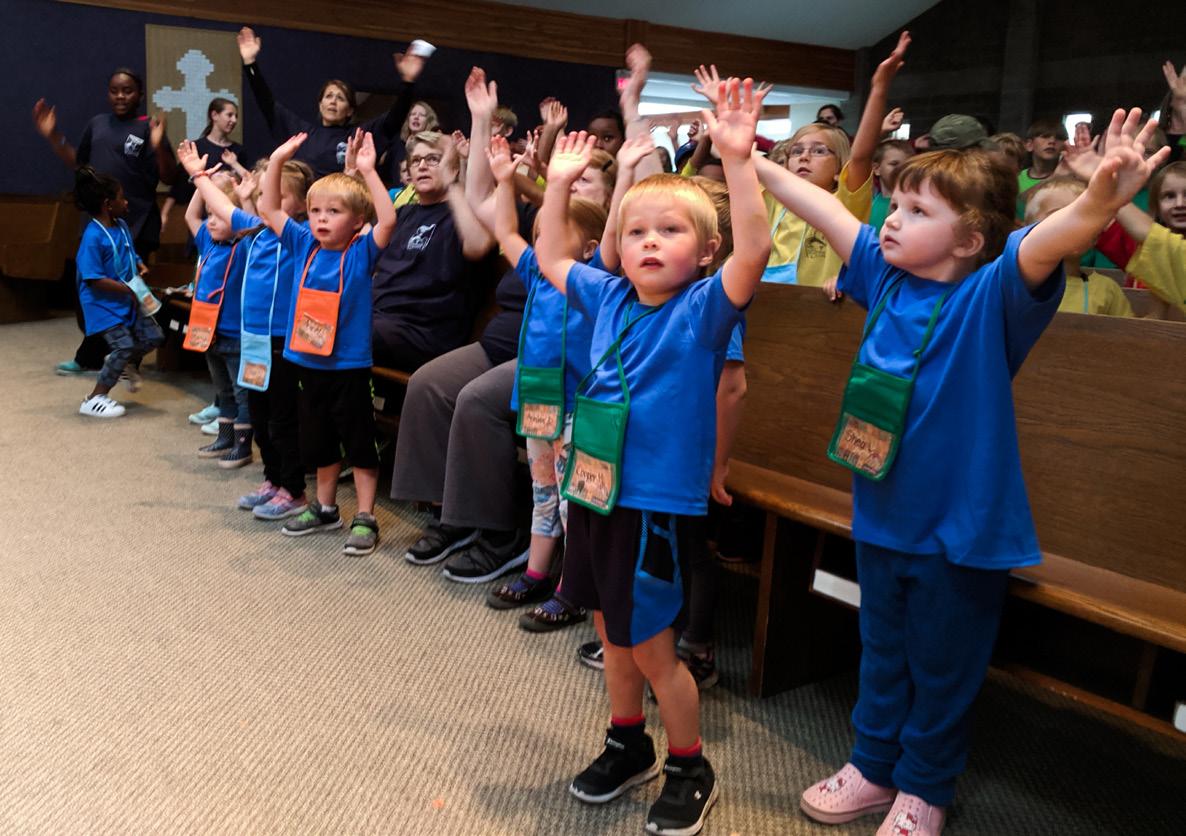

Kids Help Kids: VBS students raise money for overseas classroom

Poverty busters worldwide were recently joined by a host of Calgarian Vacation Bible School (VBS) attendees. Ninety elementary-aged children from two churches in Calgary teamed up to take poverty alleviation seriously by raising funds to furnish a school in a developing community. Knowing that children there are forced to learn without desks or school supplies, these VBS kids tackled their goal with a roar!

The churches wove the fundraiser into their four-day VBS program this past summer. “We hosted the safari-themed ROAR - Life is Wild, God is Good! program at Emmanuel Christian Reformed Church,” explained Kristina Prins, one of the event organizers. “We wanted to bring the word of God to children in our community, and give them the opportunity to give and bless others.”

Each day, kids watched videos about children’s lives in African countries. “We loved the idea of kids learning about other children around the world, and for kids to have the opportunity to bless others who aren't as fortunate,” commented Kristina.

The VBS kids found the videos a real eye-opener. “It is sad and dangerous that girls have to spend all day getting water, and that people still get sick from it,” said seven-year-old Emmit. “It made me happy to see videos of people getting out of poverty!” These conversations didn’t just stay at VBS—kids brought up these topics in their homes with parents and other family members, and were able to collect donations by sharing with friends and family.

As funds accumulated, the children’s passion shone through. “We had a donation tracker located by the entrance, and each day kids would excitedly check how much money was collected,

and how close we were to our $500 goal to furnish a school,” explained Kristina. “We also included a few 'extra' items that we could add to our donation—like a Dairy Cow, Water Tap, etc. which was definitely needed, as we collected $631!”

“It was very good to raise money for a classroom because it’s important for kids to learn they can have better lives!" explained Emmit. "And it was really good that we could also buy a cow so they have good food to eat, and that we could even get a water tap too so that their water would be clean, and it won’t be all dirty.” Clearly, this was no monkey business!

Everyone was thrilled to have surpassed the goal. Partway through the week, an anonymous donor called in to pledge an additional $500 if they met their goal, fueling the kids' excitement. “The enthusiasm of our children was inspiring,” said Kristina, “I think that the combination of watching FH videos, discussions, and the challenge helped the kids feel more connected to this cause.”

Fighting poverty isn’t just for charities and governments. If a seven-year-old “poverty buster” has what it takes to change someone’s well being, then so do you! Sometimes it takes a group of 90 poverty-fighting VBS kids to remember that.

Have a great idea that engages your community? Contact the team at the FH Canada office for support! 1-800-667-0605.

FHCANADA.ORG 15

For many of the younger VBS attendees, the videos about life in FH communities was their first exposure to life overseas.

MADE IN HAITI

“Chef” Remy has done it again! Tempt your gou boujon (tastebuds) with two savoury classics made in homes across the island nation of Haiti. Chef Remy is on staff with FH Haiti, helping host visitors as they build relationships with developing communities. His craft in the kwizin (kitchen) showcases some of the best of Haitian culture!

By Jean-Mary Edouarzin and Calvaire Remy, FH Haiti

Sos Pwa Nwa (Black Bean Soup)

SERVES FOUR

INGREDIENTS:

8 cups water

2 cups uncooked or dried black beans

1 cup coconut milk

2 tbsp olive oil

3 cloves garlic (minced)

3 feet* leek (diced)

1 tbsp butter

1 tsp ground cloves

*That's right, our Haitian chef measures literally! In Canada, try 2 leeks.

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. Bring water to a boil. Add beans, oil, garlic, leek, and coconut milk. Let simmer for about 60 minutes on medium-low heat, until the beans are soft. Add water as needed to keep the beans covered.

2. Remove 2 cups of the soup. Blend the remaining soup (an immersion blender works best), and return

1 cube chicken bouillon

1 ½ tbsp salt

1 tbsp black pepper

the 2 cups of unblended soup for an authentic look.

3. Add butter, ground cloves, and seasoning. Let simmer for 15 minutes on low heat. Stir often to prevent sticking to the bottom of the pot.

4. Garnish with a large spoonful of white rice.

16

INGREDIENTS:

6 garlic cloves (minced)

2 leeks (diced)

1 green bell pepper

3 lemons

Poul Sitwon Nan Sòs (Lemon Chicken in Sauce)

¼ thyme (fresh, leaves pulled from stem)*

¼ parsley (fresh, diced)*

1 bitter orange**

5 cups water

*substitute ¼ cup fresh herbs with 2 tbsp ground or dried herbs

**substitute with a Valencia or Seville orange

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. Dice garlic, leeks, thyme, parsley, and tomatoes. Cut pepper into large, thick slices. Squeeze juice from lemons and orange. Set rinds aside.

2. Place chicken in heat proof bowl. Boil 4 cups water, add vinegar and immediately pour over meat. Let stand for 40 seconds. This helps sanitize and tenderize the meat.

3. Drain water. Rub raw chicken with lemon and orange rinds. In a large saucepan heat oil and begin to cook the chicken over medium heat for 5 minutes.

6 chicken thighs or drumsticks (bone in)

12 cloves

1 cube chicken bouillon

2 tsp white vinegar

SERVES FOUR

1 tbsp vegetable oil

2 tomatoes (chopped)

1 onion (diced)

4. Add to the saucepan the leek-herb mixture and fruit juices. Cook for 10 minutes.*

5. Remove chicken. Add tomatoes and peppers (all but one slice) to sauce. Simmer for 5 minutes.

6. Add chicken back into the sauce. Cover and simmer for 4 minutes.

7. Plug cloves into remaining slice of green pepper. Add 1 cup of water and the clove-stuffed pepper to the saucepan. Simmer for 3 minutes then remove and discard the clove-stuffed pepper.

8. Garnish with diced onion. Serve with rice or roasted sweet potatoes.

*Or combine chicken, leek-herb mixture, and fruit juices in a container, and let rest for an hour to marinate before cooking.

FHCANADA.ORG 17

HEROES TRANSFORMATION OF

MEET BIREGEYA GERARD

Livelihood Officer in Kabarore, Burundi

Interview by Karen Koster and Michael Prins

At some point in our childhood, we realize that the superheroes we see on screen and read about in comics are just fiction. Can any one person have such incredible abilities and be of such noble character, making an extraordinary difference in ordinary people’s lives each day?

Consider the people who have made a difference in your life. A teacher who took extra time with you? A coach who saw your potential? A youth pastor who listened? For those living in many FH partnered communities, it’s the local FH staff who move into their towns, build relationships, and spend years communicating a message of positive solutions and hope who make all the difference. They may not be able to “leap tall buildings in a single bound,” but they’re there, day-in-and-dayout, walking with leaders, churches, and families as they strive to overcome poverty.

And to the families in Kabarore, Burundi, they’re better than the guys in tights. They’re the real heroes.

KK: How long you have worked with FH and what other positions have you had?

BG: I have worked with FH Burundi for [over] seven years. I have been a Care Group Supervisor, then a Multisector Promoter, and up to now, I am the Livelihood Officer.

As a Livelihood Officer, my role is providing technical expertise on agricultural and economic empowerment for the community and delivering appropriate, sustainable, and environmentally friendly interventions that meet the needs of families in the community.

Gerard lives out a quiet resolve to end poverty; he has committed his career to helping others, traveling into Kabarore almost daily.

KK: Tell us a bit about yourself, your family, and where you come from?

BG: I am 51 years old. I was born in a family of nine children— six girls and three boys. I am the sixth. We are seven still alive and I am the only boy; my two brothers passed away at an early age and my parents [passed] at the older age of 70 and 80.

My hometown is Cankuzo, in eastern Burundi. It was a small center with few people but nowadays it is getting wide, perhaps because of its cool climate with cheap plots. But [for] now I live in Kabarore. It is at 188 km from where I grew up and where my wife and children stay.

I am married to Fabiola since September 2010. She is a teacher. We have two daughters—Shekinah, six years old, and Sheila, four years old. They are children who ask clever questions. In my personal time I like to play guitar and sing Christian songs. I also like to ride a sport bicycle.

FH

18 ISSUE 25

KK: What lead you into community development work?

BG: I finished one year of Burundi National University, and later completed a degree in Social Work from Newman Institute of Social Work of Tanzania. From 1994, I started to work in a refugee camp as a supervisor to community health mobilizers’ supervisor with Doctors Without Borders, and also with the International Rescue Committee. There, I got experience working with vulnerable people.

KK: What does a typical work day look like for you?

BG: I start the day at 7:30 with a half hour devotion with my colleagues, and do office work up to 9:00. I eat brunch, then take an FH motorcycle into the community. At noon, I start home visits, normally to about five households. Next are meetings or training with volunteers, model farmers, church leaders, community leaders, or saving group members. I later return to the office and go home at 4:30.

KK: What are some of your most memorable stories?

BG: At Ryamukona community, I was launching Cascade [health] Groups and I heard one of the leaders asking her peers to contribute money so as to provide me with food and lemonade every time I go there. I asked her why she made such a suggestion. She replied that FH is the first NGO to work in their community when other NGOs would not because of difficult accessibility. She wanted to encourage me to continue supporting their community. I thanked her and explained to her

that my family needs are met and that FH sent me to serve the community and not to be served.

Another time I was sent to Kibuba community to start Savings and Loans Groups, which emphasize women participation. There was a general belief that a woman cannot keep money. A woman who was caught by her husband with some money could be accused that she got it by prostitution. Many women were victims of such a wrong belief. One young woman named Sarah told me that her husband had forbidden her to keep even one franc (less than a penny). She said that through the educational meetings I conducted for everyone in the community, her husband started allowing her to save money for medical needs and groceries such as salt, cooking oil, onion, and so on. She is a savings group committee member now.

Gerard's days are filled with people. His passion to help and his humble charisma is impacting hundreds of lives in Kabarore as he coaches community leaders, farmers, and savings group members.

Gerard's days are filled with people. His passion to help and his humble charisma is impacting hundreds of lives in Kabarore as he coaches community leaders, farmers, and savings group members.

19

"She said that through the educational meetings I conducted for everyone in the community, her husband started allowing her to save money for medical needs and groceries such as salt, cooking oil, onion, and so on. She is a saving group committee member now."

SUGAR POND

Written by: Eryn Austin Bergen, Writing for a Change

It’s easy to jump to conclusions. We do it all the time. About the driver who doesn’t use their turn signal, the mom who lets her kids eat cookies for snack, the woman standing barefoot by the side of the road holding a cardboard sign.

We jump to conclusions when the how to fix to someone else’s problem seems obvious to us. It can be hard to understand why they can’t embrace the solution we find so intuitive. We jump to the conclusion they are either too stupid, stubborn, or proud to change or to accept the help we generously offer. In our exasperation, we often forget to ask them “why.” We forget that we, too, have blind spots. This is especially easy to do when engaging cross-culturally.

immediate suffering in Cambodia’s rural communities. Clean water was at the top of everyone’s list.

For decades, families in the village of Chhuk had used a simple and effective method of collecting and storing water. Each home dug a reservoir near their house which filled with rainwater during the summer and fall monsoon season. This water lasted households throughout the remaining dry season. Families accessed this homemade water source for all their household needs – cooking, drinking, watering livestock, bathing, growing gardens. In some instances, families transformed their water-storage pits into dual purpose fish ponds – a great source of food and income.

But there was a problem. Because these ponds were filled with stagnant water unprotected from animals and debris, they were terribly contaminated. Harmful parasites and bacteria thrived in them. The result? Chronic illness for the families drinking the dirty water. Parents couldn’t work. Children couldn’t go to school. The elderly suffered. Not only were the intestinal parasites painful, but repeated bouts of illness

The late 1990s marked the early days of Food for the Hungry (FH) work in Cambodia. It was a tumultuous time as the country underwent a power transition from Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge rule to the hands of a newly empowered National Assembly. The country was still quaking from decades of rampant, state-enacted violence, fear, and hunger. In the end, deep seated poverty was the far-reaching legacy of Pol Pot’s failed utopian dream.

In partnership with other like-minded NGOs, Food for the Hungry acted swiftly to identify and prioritize areas of highest need to alleviate

Instead of drinking what was effectively poison, they could drink life. There was just one problem –they didn’t want to.

20

The pond may look idyllic, but drinking the water is sure to invite sickness.

weakened those getting sick and often caused the premature deaths of small children.

Together with their partners, FH worked to install clean water wells for the village of Chhuk. From these sources, families could conveniently collect safe drinking water and begin enjoying life free from recurring sickness. Instead of drinking what was effectively poison, they could drink life.

There was just one problem – they didn’t want to.

FH and other aid workers were stunned. Why would families prefer to drink their old, dirty water that could kill them instead of this new, fresh water that could save their lives? It seemed so stupid. At this point, the team could have simply given up and gone home. They could’ve thrown their hands in the air concluding that Cambodians are foolish, “backward” people who just want to be sick. They could have judged the people of Chhuk.

But they didn’t. Instead, they paused to ask why, and to listen to the answers. After many conversations, the truth finally came out, and it was rather simple. The new water tasted bad. The old water tasted sweet. The foreign aid workers were at a loss. To be fair, the villagers in Chhuk had a point. Groundwater often has a heavy mineral taste that can be off-putting if you’re not accustomed to it. And change is hard to swallow. So how could FH convince the families in Chhuk that switching water sources was worth it…especially if they hadn’t grown up with the benefit of germ theory?

A visiting FH donor had an idea. Ben Hoogendoorn was a faithful FH advocate, heralding the cause of ending poverty throughout his farming network in British Columbia. He took every opportunity to join FH “on the ground” to visit and encourage the communities working to get from stuck to thriving. He wondered if showing the people of Chhuk what was in their pond water might just do the trick. Ben returned to Canada to retrieve a microscope from FH’s International Medical Distribution (IMED) warehouse in Saskatoon and hand-carried it back to Cambodia. FH set up experiments with key leaders and families. First, they looked at the clean water coming from the new, protected water sources. Next, they watched parasites squirm around on the microscope

1 https://www.unfpa.org/press/promoting-international-development-through-cultural-lens

It took a shift in worldview, but now the Chukk community has embraced clean water sources, despite not always having the familiar taste.

plates of pond water samples. Needless to say, the leaders were totally freaked out!

As FH continued to form long-term relationships with the people of Chhuk and walk with them on their journey out of crisis into stability–and eventually to graduating from poverty–they saw a profound transformation. Not only did families learn to trust each other–an incredible feat after the decades-long, Pol Pot rule-by-fear regime–they also began adjusting cultural habits that proved detrimental to their health. They had the maturity and humility to listen to outsiders, examine their practices, and ask themselves whether those practices were delivering the kind of community they wanted to live in. If the answer was no, they changed.

Cultural habits are incredibly powerful. They have the potential to catalyze transformation or arrest life-saving change. Reflecting on international development through a cultural lens, the UN recognizes that “people are the products of their culture and also its creators. As such, they are not simply passive receivers but active agents who can reshape cultural values, norms and expressions.”1 In other words, while our reason for perpetuating destructive habits may have its roots in our culture, we are not helpless victims doomed to march forever on

It is never as simple as someone saying, “Don’t drink this.” There are reasons for why we do what we do. Development involves a mindset transformation, a radical worldview shift.

FHCANADA.ORG 21

the same path. We are capable of redirecting our culture when we understand the underlying values and assumptions driving our decisions and are persuaded that the benefits of change outweigh the cost.

I wonder, were the tables turned would we be so wise?

What if we, in North America, faced a public health crisis similar to the village of Chhuk, where something we were accustomed to, a practice deeply rooted in our culture, turned out to be the very thing that was making us sick – or worse, harming our children? And what if someone from the outside offered us a simple solution?

In 2015, the United Nations World Health Organization (WHO) published a controversial and groundbreaking statement: “A new WHO guideline recommends adults and children reduce their daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% (12.5 teaspoons or 50 grams) of their total energy intake. A further reduction to below 5% or roughly 25 grams (six teaspoons) per day would provide additional health benefits.”2

On the face of it, it’s hard to see how this press release could make waves. But what you might not know is Americans consume, on average, two to three times the WHO 10 percent daily limit.3 And Canada ranks 10th on the list of nations having the highest average daily sugar consumption per person in the world.4 Sugar has become core to our food system and factors into many of our cultural celebrations –Thanksgiving pies, birthday cakes, break-up ice cream – as well as daily life routines – snack time juice boxes, morning vanilla lattes, granola bar pick-me ups.

Voices in the scientific and medical communities (“outsiders”), however, have warned us for years that our sweet tooth might be getting us into more trouble than we realize. We’ve been told refined sugar causes tooth decay and weight gain, and that there is a strong correlation between sugar consumption and obesity and diabetes.5 Recent evidence suggests even certain kinds of cancers exploit a high sugar diet.6

But, despite the “outsider” WHO’s proposed solution – consume less sugar – we’re still eating and drinking it. Over two-thirds of packaged food sold in Canadian grocery stores contain added sugar.7 One out of every three Canadians is obese.8 And Type II Diabetes is on the rise in children under the age of 18.9

Why? Well…we like the way sugar tastes.

And, like the villagers in Chhuk, we have a hard time seeing the connection

2 https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/sugar-guideline/en/

3 https://www.foxnews.com/health/just-how-much-sugar-do-americans-consume-its-complicated

4 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/02/05/where-people-around-the-world-eat-the-most-sugar-and-fat

5 https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/04/case-against-sugar-lobbyists/349625/

between our consumption and many of the sicknesses we suffer. It’s simply a blind spot in our culture. But whether in Cambodia or Canada, development is never just about clean water or nutrition. It always occurs within a web of cultural values and personal and communal preferences. It is never as simple as someone from the outside pointing to poison and saying, “Don’t drink this.” There are reasons for why we do what we do. Development involves a mindset transformation, a radical worldview shift. And that takes time, humility, trust, and persuasion.

Acknowledging our own cultural blind spots first helps us cultivate the humility and courage we need to listen to outsiders, evaluate their

perspective, and make changes we decide are beneficial. Second, recognizing our cultural blind spots enables us to withhold judgement on others who appear, quite frankly, to be making nonsensical choices. It reminds us that we have a “why” for everything we do, and so do they.

By compassionately listening to the answer and considering the context, we, like Ben Hoogendoorn, may devise a way for the “other” to see their situation differently. Respect and patience may win us the privilege of offering an alternative roadmap and we, like FH, may even be invited to stay for the journey.

6 https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2019/05/food-cancer/589714/

7 https://www.berkeleywellness.com/healthy-eating/nutrition/article/most-packaged-foods-have-added-sugar

8 https://obesitycanada.ca/obesity-in-canada/

9 https://globalnews.ca/news/4336705/type-2-diabetes-kids-increase/

22 ISSUE 25

Ben Hoogendoorn (centre) visiting community leaders and families in Cambodia.

Strong

MEET JUSTA GUATEMALA

When boys at school started bothering 13-year-old Justa, she decided school just wasn’t worth the harassment. Last June, she dropped out.

Thankfully, Justa is a sponsored child. FH staff member, Ana, visited her at home regularly, offering support, counselling, and prayer.

“I am greatly thankful to God and the FH staff for their support when I needed it most,” Justa shares. “Now I am sure that God listened to my prayers and helped me through you.”

Today, Justa is excited to go to school and learn new things. Her sponsorship has meant the world to her. She thrives on the encouraging words in her sponsor’s letters which motivate her to stay in school and study hard. Thanks to her perseverance and willingness to try again, Justa has a bright future ahead.

Resilient

FHCANADA.ORG 23

Positive

***** ***** SHOP ONLINE TODAY AreyouKID-ding me? Gift Guide seasonalready? COW did you get in there? Can I MOO-veoutyet? @fhcanada @foodforthehungrycanada blog.fhcanada.org @fhcanada GIFTS FOR CHANGE G IFT G UIDE FHCANADA.ORG/GIFTS 1-31741 Peardonville Road, Abbotsford, BC V2T 1L2 1.800.667.0605 info@fhcanada.org fhcanada.org HEN-ny day can BEE a Gift Guide day!

"Poor" guests sat on the floor of the gymnasium and ate handfuls of rice for dinner.

"Poor" guests sat on the floor of the gymnasium and ate handfuls of rice for dinner.

Gerard's days are filled with people. His passion to help and his humble charisma is impacting hundreds of lives in Kabarore as he coaches community leaders, farmers, and savings group members.

Gerard's days are filled with people. His passion to help and his humble charisma is impacting hundreds of lives in Kabarore as he coaches community leaders, farmers, and savings group members.