A PLAYBOOK FOR NATURE-POSITIVE INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT

Early Lifecycle Stages and Procurement Chapter September 2024

Early Lifecycle Stages and Procurement Chapter September 2024

FIDIC, the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, is the global representative body for national associations of consulting engineers and represents over one million engineering professionals and 40,000 firms in more than 100 countries worldwide. Founded in 1913, FIDIC is charged with promoting and implementing the consulting engineering industry’s strategic goals on behalf of its member associations and to disseminate information and resources of interest to its members.

For more than 60 years, WWF has been protecting the future of nature. The world’s leading conservation organisation, WWF works in 100 countries and is supported by more than 1.3 million members in the United States and close to five million globally. WWF’s unique way of working combines global reach with a foundation in science, involves action at every level from local to global and ensures the delivery of innovative solutions that meet the needs of both people and nature.

WWF and FIDIC recognise that the engineering and conservation communities both play central roles in shaping the transition to nature-positive infrastructure. From the earliest points of infrastructure design, these two communities can shape projects to best meet nature-positive and net-zero objectives. They are well-positioned to challenge old norms; to not only break down barriers but to visualise the possible.

Technical Partner:

AECOM is the world’s trusted infrastructure consulting firm, delivering professional services throughout the project lifecycle. On projects spanning transportation, buildings, water, new energy and the environment, our public - and - private-sector clients trust us to solve their most complex challenges. Our teams are driven by a common purpose to deliver a better world through our unrivalled technical expertise and innovation, a culture of equity, diversity and inclusion and a commitment to environmental, social and governance priorities. AECOM is a Fortune 500 firm and its Professional Services business had a revenue of $13.1bn in fiscal year 2022. See how we are delivering sustainable legacies for generations to come.

The publication was made possible by funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Foundation was established to create positive outcomes for future generations. In pursuit of that vision, they foster path-breaking scientific discovery, environmental conservation, patient care improvements, whilst also focusing on the preservation of the special character of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Figure

Table

Table

Nature positivity and biodiversity net gain (BNG) are increasingly being driven by regulatory requirements across many jurisdictions, with market demand further supporting the move to adopt best practice approaches throughout the lifecycle of a project. Across all sectors, there is increased pressure from investors, customers, clients, and communities for projects to incorporate biodiversity and nature-positive thinking into each lifecycle stage. The greatest chance for successful implementation of nature-positive solutions will occur where this is considered in the early lifecycle stages of infrastructure development.

There is a wealth of guidance, standards, and frameworks available to organisations that can encourage and help inform stakeholders in implementing nature-positive solutions in infrastructure development. Even though many of the guidance, standards, and frameworks available are not mandatory, organisations are encouraged to incorporate this best practice advice to achieve the best outcomes for their projects.

It is essential to engage with a range of both internal and external stakeholders when implementing nature-positive solutions into the early lifecycle stages of infrastructure development. Buy-in is required from a range of an organisation’s internal stakeholders including senior leadership, supply chain procurement teams, finance departments, operations teams, and engineering and design teams. Additionally, external stakeholders can be instrumental in applying practical solutions in the value chain as well as improving knowledge and understanding.

Developing an early project and procurement strategy is key to ensuring the effective implementation of nature-positive solutions. This requires an understanding of a development’s value chain, stakeholders, and the establishment of clear goals to enable project aims to be communicated with the value chain and stakeholders in a coherent and structured way.

This chapter presents high-level guidance to infrastructure developers and practitioners seeking to implement nature-positive solutions into the early lifecycle stages of an infrastructure development, prior to the detailed design stage (see Figure 1). The guidance outlined within this chapter covers:

Why inclusion of nature-positive solutions in infrastructure planning is critical to driving positive change in the sector: the context, different project stages, guidance and frameworks, and considerations for businesses are all explored.

Who the key stakeholders and groups that need to be engaged at each stage are, as well as the different processes, standards and support mechanisms that can be used.

How to develop and adopt an early project strategy and procurement strategy to support nature-positive solutions.

FIGURE 1-1 INFRASTRUCTURE LIFECYCLE AND ENTRY POINTS FOR NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

Figure 1-1 highlights the different lifecycle stages of an infrastructure project and the entry points (darker green stages) at which a particular focus on nature-positive solutions is necessary. These five early project stages are expanded on below:

Strategic planning: Strategic infrastructure planning includes consideration and allocation of expenditure throughout the whole lifecycle of an infrastructure development.

Prioritisation: Determines the order in which tasks are required to be completed and ranks these by urgency and importance. Sustainability issues, including nature-positive solutions, should be high priority and considered early in projects to enable the maximum opportunity for improvements and benefits to be realised.

Project planning:

- Pre-feasibility involves early analysis of the project and is designed to give stakeholders the information they need to decide whether the project is implemented or not. Consideration of nature-positive solutions helps ensure developers are aware of the requirement to implement such solutions.

- Feasibility determines the best solutions analysed at the pre-feasibility stage. Consideration of nature-positive solutions enables procurement planning and decision-making processes to be appropriately informed and guided.

Concept design: outlines early-phase design and should consider all the opportunities for implementing nature-positive solutions. This provides developers with options to ensure solutions can be implemented effectively.

Procurement (e.g., work contracts): Nature-positive solutions should be a part of an organisation’s wider procurement strategy, and not limited to a project level. Strategies should include the requirement to include nature-positivity as part of contract procurement in the design and planning stages, as well as during construction.

As this chapter will highlight, there is considerable importance in embedding nature-positive solutions early in the lifecycle of a project to maximise opportunities and benefits. Nature positivity and BNG are increasingly being driven by regulatory requirements across many jurisdictions, with market demand further supporting the move to adopt best practice approaches throughout the lifecycle of a project. There are three principles identified in Chapter 3 (Benefits) of the main Playbook, that underpin the requirement for nature-positive solutions:

- The requirement to protect and enhance biodiversity;

- The need to reduce carbon emissions throughout the lifecycle of an asset; and

- Ensuring developments are resilient to the effects of climate change.

This chapter aims to summarise the key regulations and guidance across different contexts and recommended best practice guidelines that can be applied within the five early project stages to maximise inclusion of the above principles, as well as provide signposts to additional information.

This section aims to provide detail on available guidance, legislation, and standards relevant to the implementation of nature-positive solutions and sustainable procurement. With a focus on best practice, a basis for understanding why nature-positive solutions are required to be considered across all sectors and industries is presented. It is hoped that further relevant guidance and case studies will become available over time as activity to include nature-positivity in infrastructure projects continues to increase. This topic is in its early stages and therefore this chapter is designed to promote dialogue.

The following principles have been summarised to set the context in which nature-positive solutions should be considered.

BNG is the process of creating and improving natural habitats, aiming to ensure that developments have a measurably positive impact on biodiversity, compared to what was there prior to the development. BNG is fast becoming a regulatory requirement rather than a recommendation. For example, in the England it is now mandatory that BNG is delivered under Schedule 7A of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as inserted by Schedule 14 of the Environment Act 2021). Developers must ensure that the biodiversity present on their site is enhanced by at least 10% compared to its pre-development state. This requirement applies to most types of development, including residential, commercial, and infrastructure projects.

The Biodiversity Hierarchy1 (Figure 2-1) provides businesses, developers and ecologists with a framework to follow that limits the negative impacts from developments.

FIGURE 2-1. BIODIVERSITY HIERARCHY

Source: Adapted from Ecology By Design

The hierarchy is a set of guidelines that can be used to clearly define and establish the steps taken to improve the biodiversity value within a development project. It highlights the biodiversity impact that will occur if nature-positive solutions are considered for infrastructure projects and enables developers and stakeholders to measure biodiversity loss by categorising actions as follows:

Avoidance is the first step that can be taken to ensure biodiversity loss is as low as possible. This requires effective planning and consultation and can also reduce costs that would otherwise be spent on mitigation strategies.

Minimisation assists to manage issues that cannot be avoided through adaptation and reducing biodiversity impacts. Having a creative approach and early project implementation is key to achieving minimisation measures to reduce the duration, intensity and extent of impacts that cannot be avoided.

Restoration of areas within the development involves measures to repair degradation or damage to features of a project. This allows for an adequate assessment of the scale of restoration required.

Offsetting aims to compensate for any residual impacts after full implementation of the previous three steps of the hierarchy. Here, any net loss caused by infrastructure development can be balanced out by nature positive activities off-site.

Throughout these stages, considerations for ecological, economic, and sustainable outcomes are required from a wide range of stakeholders, therefore emphasising the need to consider them early in project design and planning to maximise the opportunities and benefits.

Whilst the Infrastructure Carbon Review2 (ICR) is focused on carbon reduction, lessons can be learnt by applying similar thinking to biodiversity and nature-positive solution implementation. As illustrated in Figure 2-2, the opportunities for carbon reduction are greatest early in the infrastructure development process and this also applies to nature. Commonly the two complement each other and can improve project outcomes.

FIGURE 2-2. CARBON REDUCTION PROCESS FOR CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS

Source: HM Treasury

To understand the importance of embedding nature-positive solutions into infrastructure planning, it is necessary to align operations with the requirements that already exist. Best practice guidance, frameworks and legislation that organisations should have an awareness of are presented below.

ISO 20400:2017 SUSTAINABLE

ISO 204003 defines the principles of sustainable procurement and highlights key considerations, such as risk management solutions and prioritisation. By setting out the core subjects of sustainable procurement (see Figure 2-3), ISO 20400 helps support positive outcomes for sustainability overall, with the environment as an area that should be given focus when considering how to implement nature-positive solutions.

FIGURE 2-3. THE CORE SUBJECTS OF SUSTAINABLE PROCUREMENT AS DETAILED IN ISO 20400

Source: International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO)

ISO 26000:2010 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

ISO 260004 Guidance on social responsibility provides guidance to organisations that want to demonstrate their recognition that respect for society and environment is a critical success factor. It links the core subjects included in ISO 20400 to social responsibility issues and procurement actions in relation to the environment, as detailed in Table 2-1.

TABLE 2-1. RELATION BETWEEN ISO 26000 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY ISSUES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT AND PROCUREMENT ACTIONS

ISO 26000: The environment and related social responsibility issues

Sustainable resource use

Protection of the environment, biodiversity, and restoration of natural habitats

Related actions and expectations for procurement

• Assess the relevance and feasibility of environmental strategies with suppliers.

• Promote environmental principles with suppliers and other stakeholders in supply chains.

• Improve in collaboration with suppliers, regarding the sustainable use of key energy sources.

• Promote and adopt sustainable agriculture, fishing, and forestry practices, including aspects relating to animal welfare.

• Protect and value in collaboration with suppliers and other stakeholders, biodiversity ecosystem services, using land and natural resources sustainably, and promote environmentally friendly sound urban and rural development.

• Respect the welfare of animals, when affecting their lives and existence, and ensure decent conditions for keeping, breeding, producing, transporting, and using animals.

Source: Extract taken from Annex A of ISO 20400

The G-20 set out the Quality Infrastructure Investment (QII) Principles5 in 2019, as outlined in Figure 2-4. This focuses on creating positive economic, environmental, including ecosystems, ecosystem-based adaptation, resource use, and climate, social and development impacts through infrastructure, and efficiency across development processes. Implementing these principles can help drive positive sustainability actions throughout a project’s lifecycle.

FIGURE 2-4. G-20 QII PRINCIPLES FOR SUPPORTING POSITIVE IMPACTS THROUGH INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS

Maximising positive impact to achieve sustainable growth and development

Building resilience against natural disasters

Source: Adapted from World Bank

Raising economic efficiency in view of life-cycle cost

Integrating social considerations in infrastructure investment

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL FRAMEWORK

Integrating environmental considerations in infrastructure

Strengthening infrastructure governance

The Environmental and Social Framework6 (ESF) is a set of mandatory standards for projects financed by the World Bank. It is designed to support environmental and social risk management and ensure that a project is prioritising sustainability, protection of people and the environment, and contributing towards positive development outcomes. The key elements of the ESF are:

Vision for Sustainable Development: aims to promote green, resilient, and inclusive development by strengthening protections for both people and the environment.

Environmental and Social Standards: outlines requirements for Borrowers (project implementers) and the Bank itself in areas including climate change, biodiversity, and stakeholder engagement.

Risk-Based Approach: provides increased oversight and resources for complex projects while allowing flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances.

Integrated Risk Management: emphasises integrated environmental and social risk management to support capacity building for Borrowers.

Transparency and Stakeholder Engagement: promotes transparency through timely information disclosure, meaningful consultations throughout the project lifecycle, and responsive grievance mechanisms for addressing concerns.

The Global Biodiversity Framework7 (GBF), formally referred to as the Kunming-Montreal GBF, consists of global targets that are to be achieved by 2030 and beyond, to safeguard and sustainably use biodiversity. This a key driver for incorporating nature-positive solutions early in project developments. There are four overarching goals to be achieved by 2050, which are:

Halting human-induced extinction of threatened species and reducing the rate of extinction of all species tenfold.

The sustainable use and management of biodiversity to ensure that nature’s contributions to people are valued, maintained, and enhanced.

Equitable sharing of benefits from the utilisation of genetic resources.

Implementation and finance to include closing the biodiversity finance gap of $700 billion per year.

The GBF sets out specific targets to be achieved by 2030 that support the reduction of threats to biodiversity; meet people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit-sharing; and providing the tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming. Of the 23 targets set out, consideration should be given to Target 14, which focuses on the full integration of biodiversity into all aspects of strategy, policy and regulatory decision-making across all sectors and at all levels of government.

The FAST-Infra Label8 is a globally recognised framework that sets out requirements and guidance for various markets to demonstrate the positive sustainability performance of an infrastructure asset. Figure 2-5 presents the four dimensions of sustainability that the Framework is based upon.

FIGURE 2-5. FOUR ‘DIMENSIONS’ OF SUSTAINABILITY THE FAST-INFRA LABEL FRAMEWORK IS BASED ON

ENVIRONMENTAL DIMENSION

SOCIAL DIMENSION

GOVERNANCE DIMENSION

ADAPTATION AND RESILIENCE DIMENSION

Balancing our planet’s natural environment and conserving natural resources to support the wellbeing of current and future generations.

Source: Adapted from FAST-Infra Label

Identifying and managing business impacts on people.

A holistic, integrated leadership and management which serves the common good, respects the environment and keeps company activities impactful.

Anticipating adverse effects of climate change and taking appropriate action to prevent or minimise the damage it can cause.

Following the requirements of the framework enables markets to introduce credibility, impartiality, and technical rigour in the labelling of sustainable infrastructure.

The Heads of Procurement (HoP) network of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) issued a joint statement9 to reflect the collective intent for sustainable procurement10 The following four priorities have been set out:

Awareness Building, Outreach & Partnership: actively coordinating sustainable procurement practices with various stakeholders with alignment on sustainable procurement efforts in operational regions.

Common Approach: sustainability needs to be integrated into procurement policies and practices, including, receiving details of sustainability approaches from suppliers, explanations of suppliers’ sustainability risks and mitigation to risks, and encouragement of the inclusion of sustainability-related evaluation criteria and clauses in final contracts.

Training/Resource & Tools Development: promoting sustainable procurement solutions and approaches by sharing experiences, knowledge, resources, and tools.

Monitoring and Communicating Impact: develop common approaches and enhance public communications about efforts and initiatives to mainstream sustainable procurement.

The common approach the principles set out offers an opportunity for effective implementation of sustainable procurement and nature-positive solutions, encouraging cross-organisational collaboration and supporting a comprehensive approach for the supply chain.

The Blue Dot Network11 (BDN) certification applies to infrastructure projects across all major infrastructure sectors including energy, water and sanitation, transport, and Information Communications Technology. This aims to consolidate various international standards and frameworks relevant to infrastructure projects, helping assist developers in aligning on relevant standards. The following elements comprise the BDN certification, with further detail on nature and biodiversity related considerations:

Promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth and development.

Promote market driven and private sector led investment, supported by judicious use of public funds.

Support sound public financial management, debt transparency, and project-level and country-level debt sustainability.

Build projects that are resilient to climate change, disasters, and other risks, and aligned with the pathways towards Net Zero by 2050. Projects must include nature-based solutions that improve climate resilience and benefit biodiversity and people to deliver key services.

Ensure value for money over a project’s full lifecycle.

Build local capacity, with a focus on local skills transfer and local capital markets.

Prevent corruption while promoting transparent procurement and consultation processes.

Uphold inter national best practice of environmental and social safeguards, including respect for labour and human rights.

Promote the non-discriminatory use of infrastructure services.

Advance inclusion for women, people with disability, and underrepresented and marginalised groups.

Engaging with and aligning these elements can ensure infrastructure development projects effectively implement sustainable procurement and nature-positive solutions within early lifecycle stages, by holding developers to account for achieving targets set.

The UK Government’s Green Book12 offers guidance on assessing and valuing effects on the natural environment. Natural capital stock levels need to be systematically measured and monitored for social costs and benefits to be understood and controlled. The guidance asks the following questions as a starting point for consideration of development impacts on natural capital.

the use or management of land, or landscape?

the supply of natural raw materials, renewable and non-renewable, or natural?

the atmosphere, including air quality, GHG emissions, noise levels or tranquillity?

the environment from which they are extracted?

an inland, coastal, or marine water body?

opportunities for recreation in the natural environment, including in urban areas?

If any of these issues are likely to occur, then further analysis is required before progressing with the project. This guidance aligns with early implementation of nature-positive solutions, prompting developers to understand the nature associated risks in the early lifecycle stages of infrastructure developments. 1 5 2 6 3 7 4 IS THE OPTION

wildlife and/or wild vegetation, which are indicators of biodiversity?

Guidance within the United States13 can be found in the government report Opportunities to Accelerate Nature-Based Solutions: A Roadmap for Climate, Progress, Thriving Nature, Equity, & Prosperity, which provides guidelines for the design and implementation of nature-based solutions to:

Start with nature-based solutions to address multiple, critical societal challenges simultaneously, and often in a cost-effective way. Promote and integrate nature-based solutions wherever possible unless alternatives are demonstrated to be more beneficial.

Benefit people and nature so that solutions meet the needs of both people and the environment.

Interweave equity as inequalities leave some communities at greater risk from climate change and limited access to nature.

Use evidence to help ensure effective design and tailor solutions to the circumstances.

Continually improve understanding of nature-based solutions to evolve in response to new evidence and novel challenges. Solutions should be monitored to assess performance, inform adaptive management, and promote transparency.

These principles are not mandatory but can be applied by government agencies, the private sector, and non-governmental organisations, as they provide a clear and effective method of implementing nature-based solutions into procurement processes, and early-stage development design and planning.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards14 provide guidance on how to identify risks and impacts to avoid, mitigate, and manage them and undertake business in a sustainable way. Assessment and management of environmental and social risks (including biodiversity loss) are required to be managed in an effective manner to reduce adverse project impacts.

Performance Standard 6 covers Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Management of Living Natural Resources, with objectives to:

Protect biodiversity.

Maintain ecosystems.

Promote sustainable management of natural resources through integrating conservation needs and development priorities.

Systems and verification practices in relation to supply chain management are set out within the standards and are required to be met for an organisation to manage and control nature-positive impacts in development.

Table 2-2 highlights how the various guidance and frameworks detailed below align to the early lifecycle stages in infrastructure development.

The colour coding here differentiates between the lifecycle stages of infrastructure development. The first five dark green boxes relate to the early lifecycle stages that are being focussed on as part of this chapter. The later lifecycle stages have been included to provide a holistic overview of the whole project lifecycle

The following maps detail legislation that relate to or incorporate the need for consideration on nature positivity or biodiversity with respect to infrastructure developments.

2.3.1.1

The aim of European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Act15 directive is to foster sustainable and responsible corporate behaviour, while guiding human rights and environmental considerations within organisations operations and governance processes. The Directive implements a corporate due diligence duty on organisations and specifically on Directors. The duties imposed are designed to minimise and ultimately prevent negative human rights and environmental impacts.

The German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act16 emphasises human rights, environmental protection and responsible supply chain management on organisations operating within the jurisdiction. The defined due diligence obligations conveyed under this law apply to businesses, the actions of their contracting partners and the actions of indirect suppliers. This emphasises the importance of considering nature-positive solutions across the whole value chain, and considering biodiversity impacts early on in procurement activities to enable greater positive impact.

2.3.1.3

The Environment Act 202117 introduced a mandatory requirement for BNG for projects consented under section 7a Town and Country Planning Act in England to be set at a minimum of 10% for new developments (with some exceptions) to halt the loss of biodiversity.

2.3.1.4

The Commercial Organisations and Public Authorities Duty (Human Rights and Environment) Bill18 aims to enhance the accountability and responsibility in preventing human rights and environmental harms. The overall purpose is to place obligations on organisations to prevent human rights violations and environmental damage. Measures included within the Bill include undertaking proper due diligence, reporting requirements, civil liabilities and penalties and notices. This Bill is yet to be enacted into law; however, this has been included for future reference.

The US Government’s Federal Acquisition Regulation19 (Chapter 1 of Title 48) is the primary regulation for use of all executive agencies in their acquisition of supplies and services. The Regulation provides a flexible framework for procurement, ensuring integrity and efficiency in acquiring goods and services.

The Government Procurement Law (GPL, 2002)21 makes it compulsory for procuring entities to report their implementation of the measures and data gathered in the official government procurement media. This encourages transparency throughout the whole procurement process and means information around buying and selling is publicly available.

The Commonwealth Procurement Rules20 govern how entities procure goods and services and are designed to ensure value for money. The overarching rules for achieving value for money include encouraging competition, use resources in an efficient and effective manner, be transparent and engage in appropriate risk management.

Aligning with European legislation and requirements, the Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive (CSRD)22 aims to foster transparency by enforcing reporting on sustainability activities for all companies within China. The legislation reinforces reporting rules and ensures stakeholders gain insight into a company’s environmental and social impacts.

The Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting (BRSR)23 mandates Indian companies to provide quantifiable metrics on sustainability-related issues, for example in environmental protection and respect for human rights. This framework aims to make connections between a company’s ESG performance and its financial performance. Greater transparency will therefore exist as regulators, investors and other stakeholders are able to access overall growth and sustainability.

Linking to Chapter 3 of the main Playbook, three core principles have been identified as key factors driving the increased uptake of nature-based solutions in the infrastructure sector.

BIODIVERSITY CARBON RESILIENCE

Habitat creation and reducing endangered/at risk species extinction

Reducing embodied and operational carbon, increasing carbon sequestration and offsetting

Reducing risks associated with extreme weather events

Nature-positive solutions are becoming a minimum requirement across the legislative landscape and there is increasing pressure from investors and wider stakeholders for the need to ensure infrastructure has a positive impact on nature. To this end, there are many risks to businesses and organisations who do not implement nature-positive solutions, these include:

Ecological risks: businesses may experience greater operational risks due to resource dependency, scarcity and quality which can be linked to increased costs, supply chain deterioration and operational disruption.

Liability risks: transparency is increasing through organisations disclosing and reporting their biodiversity impacts which could result in an increase in legal cases. While this is positive in that companies will take steps to avoid/mitigate biodiversity impacts, organisations may be deterred from voluntary disclosures.

Regulatory risks: action on biodiversity is evolving and increasing, therefore organisations face risks around changes to policy, law, technology, and markets, which may create a change in demand for organisations.

Reputational risks: there is increasing pressure from investors, consumers, stakeholders, policy makers and society to report and manage environmental, social and governance risks (including biodiversity risks).

Market risks: consumer awareness of sustainability issues is increasing globally. Changes in customer preference (such as products with reduced biodiversity impacts) can create challenges.

Financial risks: loss of investment opportunities because of lack of consideration for biodiversity as investors use recognised standards, guidance, and disclosures to inform their assessment for investments.

Having discussed why embedding nature-positive solutions in early stages of infrastructure development projects is important, this section explores the key stakeholders, groups and organisations that can be consulted to increase knowledge and understanding of embedding sustainability into the early stages of infrastructure developments. There are a range of internal and external stakeholder groups to consider. Internal stakeholders are those within the organisation such as procurement teams, operations and engineering teams and senior management. External stakeholders are organisations who can be engaged to provide expertise on sustainable procurement and implementing nature-positive solutions and extend to organisations and/or individuals who will need to be consulted during the development project. This section also covers the guidance and digital tools available to support users in their implementation of nature-positive solutions.

There are a range of internal stakeholders required to be engaged in early project stages. Figure 3-1 highlights the key stakeholders within an organisation required to be involved in the review of sustainability issues and the implementation of nature-positive solutions.

FIGURE 3-1. KEY INTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR ROLE IN IMPLEMENTING NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

Supply Chain Teams

Provide expertise and understanding of supplier capabilities and capacity.

Finance

Responsible for managing budgetary and funding matters, particularly the business-case.

Procurement

Developing strategy, sourcing, contract management, performance monitoring.

Engineering & Design

Ensure solutions are technically feasible and effective as well as driving innovative thinking.

Operations

Implementing new processes and identifying opportunities for improvement.

Executive & Senior Management

Strategic decision-making, driving culture and organisational mindset.

Having each of these stakeholders engaged in embedding sustainability and nature-positive solutions allows for an increased understanding of its importance and provides a holistic viewpoint of potential solutions, challenges, and opportunities. Each of these stakeholders is likely to be involved in the early-stage lifecycle of an infrastructure project at any one time, therefore buy-in and understanding is key to effective implementation.

Engagement with external sources can encourage an organisation’s stakeholders to gain a greater understanding of what other companies are doing and support knowledge and best practice sharing to make positive environmental and biodiversity impacts within their organisations. External stakeholders can range from suppliers/contractors, customers, and consumers, to regulators, industry bodies, community groups, and associations. The following paragraphs summarise resources for engaging stakeholders in the value chain.

The Sustainable Procurement Pledge24 (SPP) is an international non-governmental organisation for procurement professionals, academics, and practitioners aimed at driving awareness on responsible sourcing practices. Driven by knowledge sharing across different sectors, the SPP’s strategy is centred around empowering and equipping procurement professionals and encouraging strong leadership within organisations so that sustainable procurement practices will increase growth.

The Pledge encourages stakeholders to “stop exploitation of nature and human beings, environmental pollution, rising inequality and injustice” and “act against modern slavery, human trafficking, child labour corruption and bribery while upholding business ethics and law-abiding behaviour.” While this pledge is grounded in what should be considered standard legal and regulatory requirements for operating a business and part of an effective governance structure, it is important to recognise that being part of this community means organisations and individuals will be held to account for their actions and ensures transparency across business operations.

Furthermore, the SPP links into each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set out by the United Nations. With the focus of nature-positive solutions, particular attention should be given to SDGs 14 and 1525. These SDGs can be achieved through:

Eliminating pollution and overfishing are essential in protecting these resources as we begin to responsibly manage marine life around the world

Promotion of sustainable use of ecosystems and preserving biodiversity is of paramount importance for achieving this SDG.

Source: United Nations

Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) is a global professional body working for procurement and supply chain professionals. There are several benefits that can be used via CIPS membership, such as developing knowledge and expertise through training and events, access to resources, networking opportunities, and access to innovative tools to support their work.

CIPS provides a useful forum for members to share common challenges across a wide range of sectors, including compliance with environmental laws and targets, and provides guidance for sustainability topics, such as:

Sustainable procurement strategies: CIPS identifies and guides members on the stages required in sustainable procurement strategies and information on successful implementation;

Circular procurement: this is the consideration of a product from design stage through to disposal. CIPS offers advice and encourages members on the various models that need to be considered to ensure sustainable circular procurement processes can be achieved; and

Carbon management: this involves understanding how and where activities of an organisation generate emissions and extends to ensuring the minimisation of emissions in an ongoing efficient way. CIPS provides its members with key guidance on effective carbon management.

The Supply Chain Sustainability School (SCSS)26 is a free service in the UK that provides access to a range of training across various topic areas including, sustainability, digital, fair inclusion and respect (FIR), lean construction, management, off-site, people and procurement. As well as training the SCSS has opportunities for individuals and companies to attend networking events, gain CDP points, complete self-assessments, and receive action plans.

The SCSS regularly organises webinars and workshops which provide useful opportunities for businesses, academics, and industry partners to share and learn from each other on several topics, including for example Green Infrastructure, Embedding Carbon Reduction into Sustainable Procurement, and Developing a Sustainability Strategy. These resources are free for members to attend and use, with recordings available via their free learning resources catalogue.

The FIDIC Climate Change Charter27 is a resource that can be used by various stakeholders, including FIDIC’s member associations, project teams, and individual engineers. The Charter sets out a series of actions as to how stakeholders across the globe can address climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience of the built environment in the years to come.

This offers guidance and recommendations on nature-based solutions being incorporated into infrastructure developments and focuses on nature-based solutions in reference to developing an approach that integrates solutions and resilience into the delivery and performance of infrastructure.

Understanding and applying the relevant standards, guidance and digital tools presented below will provide maximum opportunities and benefits for the potential nature-positive solutions present within infrastructure development projects.

2017 SUSTAINABLE PROCUREMENT

2015 COLLABORATIVE BUSINESS RELATIONSHIP FRAMEWORK

2010 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

As discussed in Section 2.2 of this Chapter, ISO 20400 offers guidance on embedding sustainable procurement within an organisation and is considered best practice for implementing sustainability throughout the process. With the “Environment” as a core subject within the guidance, this should be used as a basis for informing a sustainable procurement strategy alongside other relevant standards and guidance.

ISO 44001 specifies requirements for effective identification, development, and management of collaborative business relationships within or between organisations and can help to ensure nature-positive solutions are embedded into early stages of infrastructure development. The Collaborative Business Relationship Framework is designed to deliver a wide range of benefits, from enhancing competitiveness and performance to adding value to all organisations.

ISO 26000 provides guidance on the recognition of society and environment being the “right thing” to do. Application of ISO 26000 is being increasingly viewed as a way of assessing the sustainability commitments of a company. Linking to nature-positive solutions, ISO 26000 ensures a range of subjects are at the forefront of a company’s governance operations. Compliance with ISO 26000 enables companies to follow best practice in terms of social responsibility and the environment.

Digital tools can assist companies to manage their ESG risk, particularly those that exist within their supply chain. Use of these tools can help ensure appropriate levels of consideration have been given to nature-based solutions at the early stages of a project (i.e. supplier selection stages). Where appropriate nature-positive solutions have been embedded within the early design and planning stages of a project, these tools will be key in ensuring that solutions are consistent across the whole supply chain and throughout the procurement process. A selection of tools is presented in Figure 3-2. Note that this is not an exhaustive list, but it does demonstrate the capability of tools in the space currently.

FIGURE 3-2. EXAMPLES OF DIGITAL TOOLS AVAILABLE TO SUPPORT SUSTAINABLE PROCUREMENT PRACTICES

Evidence-based assessments using information provided by the supplier, recognised standards, 3rd party audits, government agencies and news aggregation tools, to provide ratings for key areas of sustainability:

Environment (e.g. carbon, water, biodiversity, waste);

Labour and Human Rights (e.g. Health & Safety, forced labour, diversity, and inclusion);

Ethics (e.g. corruption);

Sustainable Procurement (measuring how sustainability is built into the supplier’s strategy, processes, and procedures).

Allows users to assess supplier ESG issues, conduct in-depth sustainability assessments to measure a company’s full economic and social impact, and review and conduct due diligence checks.

Their ESG Risk Rating tool helps avoid adverse nature or biodiversity by:

Measuring an organisation’s exposure to material, industry specific ESG risks; and

Enabling consideration of ESG risks associated with a potential contractor or supplier.

Provides data and software solutions to help companies make informed ESG investment decisions, such as their Supply Chain Transparency tool, which:

Integrates risk management and sustainability factors to deliver holistic insights;

Provides real-time sustainability monitoring and regulatory and ESG risk assessments;

Enables organisations to connect suppliers in one unified platform to allow responsible sourcing and emissions tracking;

Enables organisations to connect its suppliers in one unified platform to allow responsible sourcing and emissions.

Each of the stakeholder groups, digital tools and standards discussed in this section are key to ensuring successful implementation of nature-positive solutions holistically for infrastructure developments. ISO 20400 is a key driver for ensuring sustainable procurement is embedded within organisations and enables stakeholders to understand the steps that are required to effectively implement nature-positive solutions. Using ISO 26000 and ISO 44001, in conjunction with ISO 204000, offers the most potential for ensuring successful implementation of sustainable procurement, while considering collaborative relationships and social and environmental issues.

Additionally, using existing bodies such as the SSCS, SPP, and CIPS can also assist stakeholders in understanding issues across the supply chain. Access to training and knowledge sharing available through these organisations, enables best practice actions to be shared and a greater understanding of how to effectively implement nature-positive solutions within infrastructure development.

Digital tools are an effective resource for ensuring sustainable procurement is embedded from the outset. Assessing suppliers on their sustainability and ESG credentials before contracting is key, as this allows organisations to avoid those who are potentially causing negative environmental and social impacts enabling nature-positivity to be incorporated from the outset of a project.

Creating a nature-positive infrastructure project requires more than just implementing nature-positive solutions to improve the direct, localised effects of a development on biodiversity, climate, and carbon, it involves applying the same mindset to the value chain and a development’s broader, indirect impacts.

The following section aims to assist the reader understand the impact of their supply chain and start to establish clear goals and objectives for active engagement with their key suppliers and service providers.

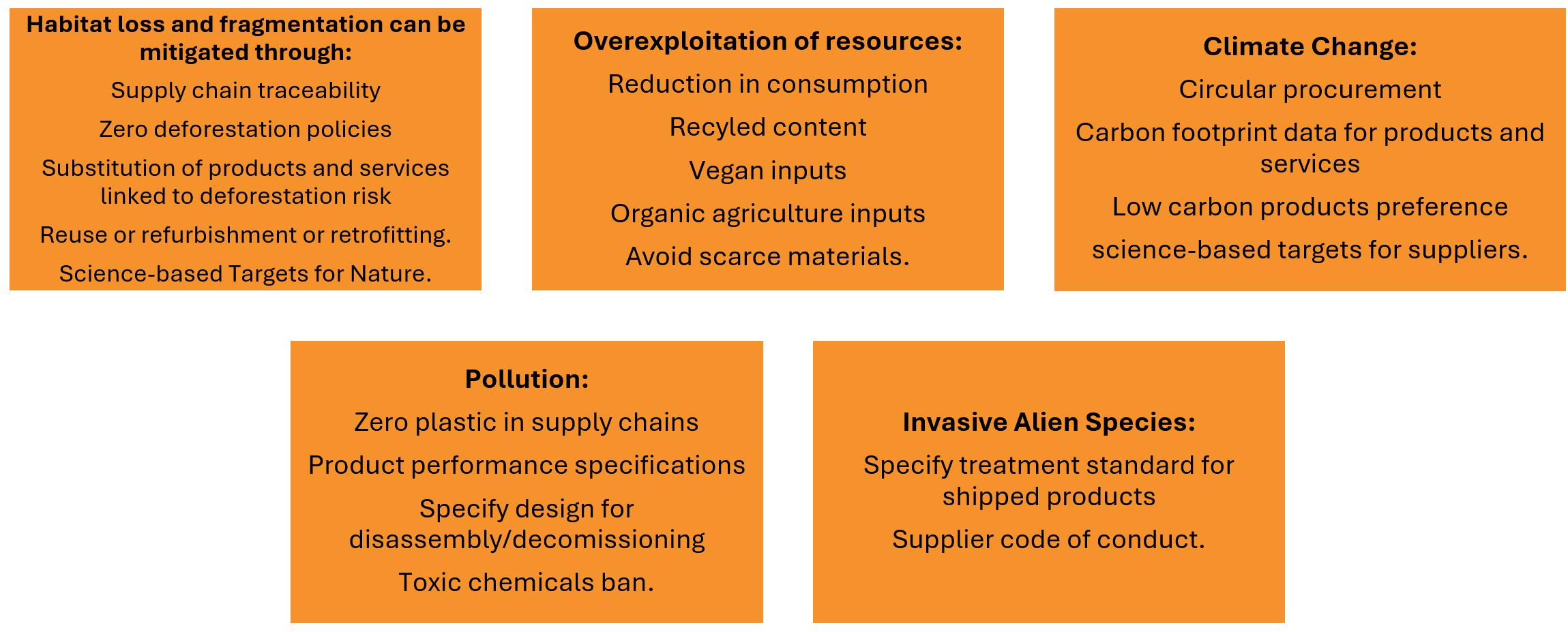

Mapping of the value chain to identify where impacts take place and quantifying them is an important first step to focus minds on the consequences and opportunities associated with the infrastructure project. Understanding these impacts can be achieved by analysing the biodiversity footprint of the materials, parts, services, and the suppliers and contractors that provide these. This will include considering the potential impacts of raw material extraction, transportation and distribution, and the production processes and activities that suppliers employ. Figure 4-1 highlights the potential impacts that a robust procurement process can help to mitigate in the value chain.

FIGURE 4-1. NATURE RELATED FACTORS THAT CAN BE INFLUENCED BY PROCUREMENT ACTIVITIES

Source: AECOM, adapted from the Sustainable Procurement Pledge 28

Once an understanding of the potential impacts and opportunities associated with the infrastructure project has been mapped, nature-positive goals can be set. Considerations should be given here to the overall objective for the project, including who will use it, its purpose, and how a nature-positive mindset can be integrated. Further to this, thought as to where solutions can serve joint natural services is recommended, in terms of the creation of carbon sinks, enhanced amenity, or community value. A holistic approach to sustainability is necessary to prevent gains in one area being carried out to the detriment of another.

A final high-level consideration, before the detailed process of incorporating nature-positive factors into the procurement process itself, is to aim to establish a culture amongst all stakeholders that promotes sustainable thinking. Early and regular engagement is key to this and while it is not the complete responsibility of the developer or lead consultant to set the overall culture amongst all stakeholders, a collaborative approach can assist to shape this.

Involving stakeholders in the above activities related to assessing high-level potential impacts on nature, and setting nature-positive project objectives, can be a valuable tool to gaining buy-in to the sustainability aims, and making sure that the project begins with nature-positivity at its heart. Engagement extending as far as regulators, investors, designers and where appropriate local government, communities, and other agencies, as well as the developer’s own procurement function, can act to build capability and move to a proactive approach.

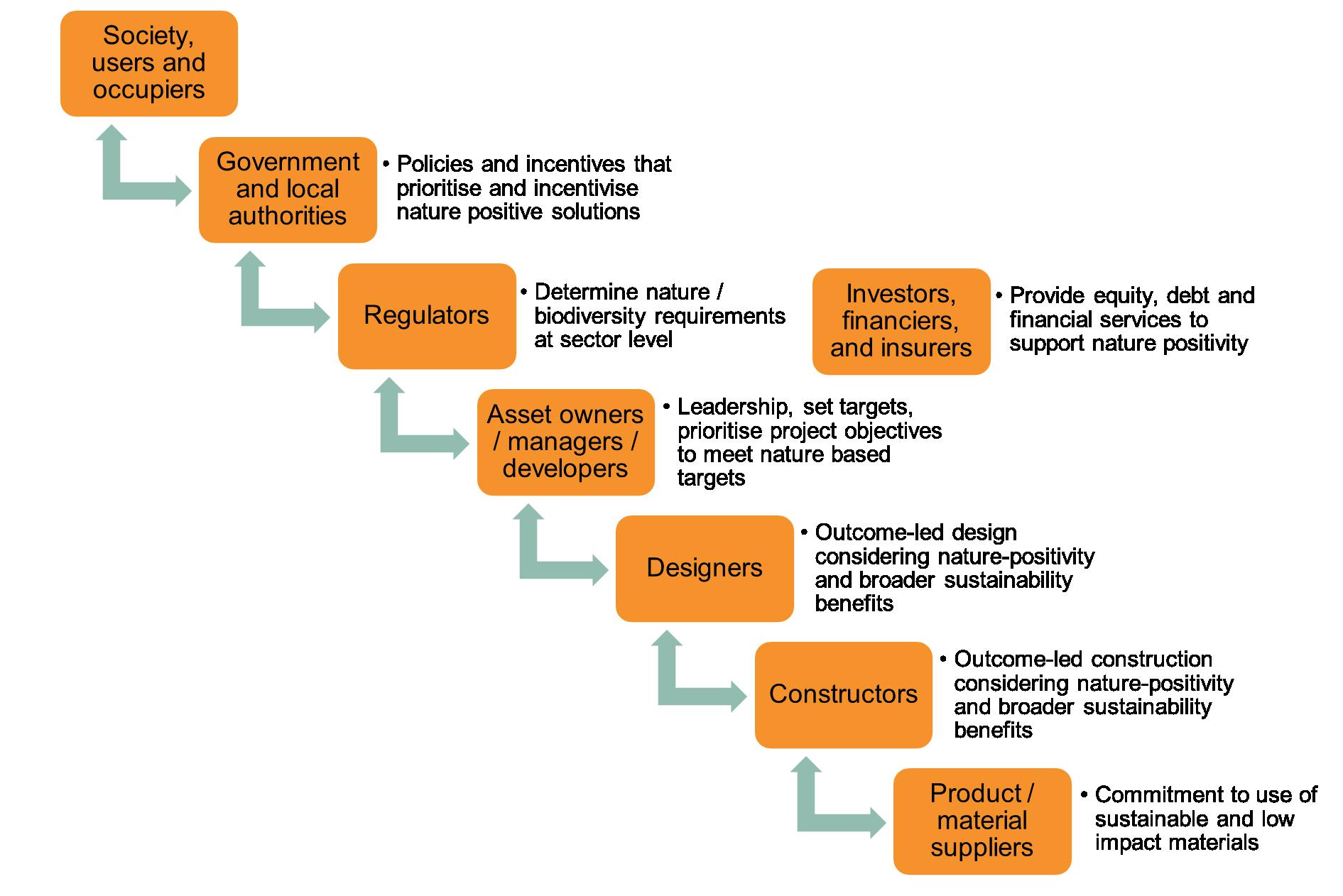

An outline of the stakeholders in a typical infrastructure development project and their roles related to nature-positive solutions is presented in Figure 4-2. This shows the high-level role that each stakeholder can hold in the context of integrating nature-positive solutions at a strategic level. The next section details how these considerations can be practically incorporated into the procurement process to realise robust nature-positive infrastructure developments.

FIGURE 4-2. OUTLINE OF THE STAKEHOLDERS IN A TYPICAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT AND THEIR ROLES RELATED TO NATURE-POSITIVE SOLUTIONS

Source: AECOM, adapted for nature-positive solutions from PAS 2080 29

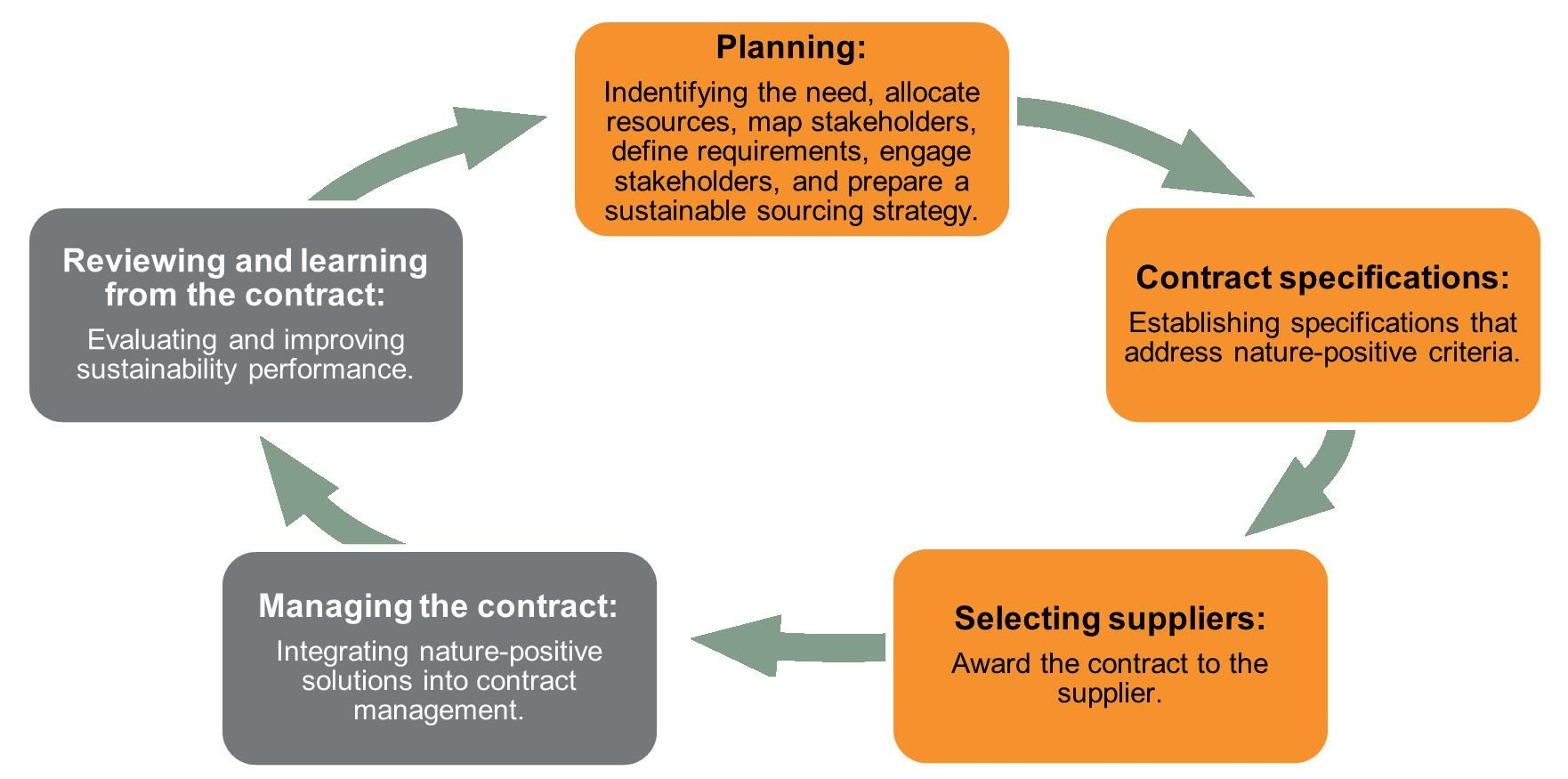

A typical procurement process is detailed in Figure 4-3. Each of these procurement steps will be considered in turn, to detail how nature-positive solutions can be incorporated into the process. While this document considers the early stages of an infrastructure development (see green boxes in Figure 11), procurement involvement in processes in the grey boxes can also be considered upfront in a project, and early work will be required to influence the outcomes throughout the procurement cycle.

FIGURE 4-3. TYPICAL PROCUREMENT STEPS INTO WHICH NATURE-POSITIVE CONSIDERATIONS CAN BE INCLUDED 30

The starting point should always be to assess the business need of the infrastructure project. While the requirements of the project are being defined and streamlined, considerations of sustainability within the value chain should be considered as part of the success criteria wherever possible. Specific aims for nature-positive outcomes should be considered alongside economic and societal needs, to make sure that decisions are not being made to the detriment of the natural environment which would be challenging to reverse at a later stage.

As seen in the Biodiversity Mitigation Hierarchy (Figure 2), avoidance is the first step to protecting the natural environment. If the infrastructure development is deemed necessary, then the early planning and design stage can be used to design out unnecessary or particularly harmful aspects of the infrastructure as well as identify opportunities for and commitment to nature-positive solutions.

It can be challenging to justify the ‘business case’ or need of an intervention that could help the natural world if it is not monetised. While the societal shift in this thinking is being managed, techniques such as natural capital asset stock assessment or ecosystem services assessment can be implemented to quantify the impacts as part of a business case. The Green Book, published by the UK Government provides a good starting point for such assessments, as detailed in Section 2.2 of this chapter.

Most infrastructure projects will be large in scale and therefore it is recommended that a stakeholder is chosen who has specific responsibility for integrating nature-positive solutions. This can be a sustainability specialist within or close to the procurement function, or a sustainability or biodiversity specialist from the business who has the requirement for the procurement to take place.

Once the responsible stakeholder is in place, a more detailed stakeholder mapping process is recommended to identify stakeholders, both internal and external, who will have input, control or advice for the decision-making stage of the procurement process; for nature-related issues. Figure 10 provides a starting point for stakeholder identification relating to infrastructure projects, and it is also important to include internal and external stakeholders, as detailed in Section 3 of this Chapter.

Building on the success criteria defined for the business case, the requirements for the project in terms of achieving nature-positive solutions can be defined. Steps to be taken to achieve and integrate these into the success criteria are as follows:

Identify the relevant aspects of biodiversity / nature-positive / broader sustainability policy and requirements that apply to the procurement aspects of this infrastructure project.

Revisit the key areas in the value chain where procurement processes can influence nature and complete preliminary estimates of where nature could be enhanced.

Consider the desired outcome, i.e. the ideal scenario for nature for the project, and set this as a requirement up-front, rather than just a specification item in a contract. This will encourage more innovation amongst stakeholders from an early stage.

Relate back to lear ning from similar projects and check for issues or positive outcomes in terms of the broader aspects of sustainability. There may be learnings that can be included and applied here to enhance performance.

By following these steps, the case for integrating nature-positivity can be demonstrated, and assurances can be made that support steps taken towards nature-positive outcomes to align with core practices and overall objectives. At this point, the supply chain can be reviewed to identify further opportunities that have multiple benefits such as increasing biodiversity, social value and reducing carbon (e.g. source sustainable materials).

Examples of success criteria:

• Legal obligations, such as compliance with 10% biodiversity net gain in the UK Environment Act 2021

• Best practice solutions, such as:

• Biodiversity enhancements within areas where legislation does not apply;

• Habitat restoration to meet or improve degraded habitats to their natural state;

• Resource efficiency to reduce use of water, materials, and energy using sustainable practices and technologies;

• Community engagement to ensure active participation and consideration of the local community and their needs, including their dependence upon the natural environment and the impact of the development upon it;

• Climate resilience and the project’s ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions, such as extreme weather events or shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns; and,

• Stakeholder satisfaction to include positive feedback from stakeholders, including local communities, government agencies, NGOs, and businesses.

Biodiversity and nature-positive criteria should be included throughout the value chain of the project as part of the risk assessment undertaken by the procurement function. Criteria should also extend to include the infrastructure itself and its impact on the local area.

Before preparing the sustainable sourcing strategy, it is advisable to engage with stakeholders. Alongside the processes already undertaken in relation to stakeholder engagement and mapping, a sustainability assessment of potential contractors and suppliers can be conducted with nature considerations in mind. The resources identified in Section 3 of this Chapter can provide useful tools to undertake these reviews quickly and effectively. This helps to establish an engagement strategy with key stakeholders in the supply chain, which can inform where risks and opportunities are readily available, to promote or encourage nature-positive solutions.

Engagement with potential suppliers, contractors and stakeholders through supplier working groups and workshops to seek out activities that may already be underway, or innovations that stakeholders are willing to share, may well influence the development of the sustainable sourcing strategy or indicate the level or influence that the procuring party may have over the supplier to achieve nature-positive outcomes. Avenues for potential working groups between stakeholders can also be explored to drive nature-positive outcomes through collaborative working.

Methods of Value Chain Stakeholder Engagement:

• Sustainability Working Groups amongst contractors working on the same project.

• Workshops to discuss approaches to the requirements or aims.

• One-to-one conversations to discuss points of contract or specific specifications.

In addition a matrix looking at extent of influence that the procuring party has over a supplier’s provision of nature-positive initiatives and their ambition to supply in a nature-positive way could be used (Figure 4-4). Such an assessment can be used to explore the level of ambition amongst suppliers, and the level of

influence that the procuring party could have on a particular procurement activity. By assessing suppliers in this way, the outcomes can be used to identify the variation in supplier credentials related to sustainability within the market.

FIGURE 4-4. MATRIX FOR CONSIDERING THE SUSTAINABILITY OUTCOMES THAT CAN BE ACHIEVED FROM THE MARKET

Source: adapted from ISO 20400

To develop the sustainable sourcing strategy, the business case (i.e. the need), requirements, and success criteria should be revisited and included within the strategy, with the aim to fully integrate nature-positive solutions within the overall sourcing activities for the works. Any learnings from supplier engagement and previous procurement exercises should also be included to maximise opportunities for continual improvement.

As is proportional to the project, the sustainable sourcing strategy can be as short as a page or considerably longer. Key nature considerations to be included alongside broader sustainability aspects are:

Key findings about risks to nature and opportunities for enhancement for the infrastructure development, specific to the need and the supply market;

The actions required to manage key risks to nature and opportunities for enhancement;

The recommended demand-related approach (e.g. avoid, minimise, restore, offset, contribute, in accordance with the Biodiversity Mitigation Hierarchy);

How the sourcing approach delivers nature-positive objectives;

How nature-positive requirements are incorporated into the specification, including any go/no-go criteria at the prequalification or tender stage (care should be taken to ensure all suppliers are given full and fair opportunity to compete);

How nature-positive aspects are incorporated into the draft contract or terms and conditions;

The weight given to nature-positive solutions in the evaluation criteria, with careful consideration given to finding the best balance with other criteria, such as price or quality;

The expected nature related benefits; and

The impacts of nature-positive solutions or approach on the project plan and budget.

A US pharmaceutical company has implemented a Responsible Supplier Programme that has helped their suppliers and senior management develop a greater understanding of nature. The Programme covers 6 key priority topics: climate change, human rights, deforestation, responsible packaging, water, and waste. To prioritise and ensure nature is properly recognised, the company created a more concise and appropriate narrative for deforestation, responsible packaging, water, and waste topics to fall under the broader scope of nature. Separating nature out into these different sustainability topics has helped their suppliers and senior management understand their role in combatting adverse nature actions. Greater understanding from various stakeholders assists successful nature-positive solutions to be embedded within industry.

The following paragraphs detail the process to select suppliers, develop contracts and draft specifications that detail supply chain requirements.

The usual scoring and assessment methodology should be applied to supplier selection, to make sure that the process is fair and transparent. The suppliers and contractors should be made aware of the selection criteria and process when they are invited to tender. Establishing strategic supplier groupings based on an assessment of their sustainability performance is an effective approach for prioritising during the sourcing group.

Activities undertaken earlier in this stage, such as the supplier mapping matrix and benchmarking of suppliers provide a mechanism to do this. Once these groups are established, sourcing activities can be streamlined to provide priority to these suppliers in bidding processes and working groups can be used to identify new opportunities and preferred bidders.

Ensuring nature-positive requirements are incorporated into the terms agreed with potential suppliers is a critical step in embedding the aims and objectives of the sustainable sourcing strategy. There are several mechanisms that can be used to achieve this:

Contractual clauses should be included in standard terms issued to prospective suppliers that enable tracking and monitoring towards desired outcomes, helping to make sure contractors can be held accountable for progress made.

Standards such as ISO 20400 and ISO 44001 can be included as minimum requirements of suppliers to be able to contract with the organisation.

Specifications for parts, materials and products are useful for setting expectations of what is required of suppliers, particularly for activities such as resource extraction and production processes.

Supply Code of Conduct, including nature-positive goals and ambitions for the project in supply chain code of conduct documents assist to reinforce the expectations of suppliers to support the development’s aims.

Sustainability ratings and assessments, such as those detailed in Section 2 above, provide a useful benchmarking tool that is transparent and consistent. Aligning contractual key performance indicators (KPIs) and metrics to these assessment ratings help to drive responsible, nature-positive activities.

Suppliers and contractors should filter these requirements through the value chain to optimise success.

The Chancery Lane Project is an organisation of legal professionals that draft and share template clauses for companies to incorporate into their standard terms, e.g. a clause that incentivises the minimisation of deforestation and work towards Zero Deforestation in the supply chain.

UK water company, Anglian Water, have included in their commitments to protect and enhance the environment as part of their purpose into their Supply Chain Code of Conduct, with the minimum requirement that all suppliers not only adhere to and uphold all relevant regional and national environmental laws and regulations, but also expect construction suppliers to follow the mitigation hierarchy for biodiversity and take steps to restore and offset biodiversity impacts.

While not covered by this chapter, there are important steps in the later stages of contract management undertaken by the procurement function that should also be considered. These include:

Monitoring of supplier performance while the contract is live: organise time appropriate check-ins (monthly or quarterly) with the contractor to discuss how the specifications and other contract clauses are being implemented as part of the work, or procurement of products, parts, or services;

Measurement of metrics is key to measuring success: keep up to date with any reporting requirements set in the contract and address any concerns early on so that early intervention or support can be implemented if required;

Embedding nature-positive solutions throughout the supply chain: use resources available, such as the supply chain sustainability school to upskill the supply chain; and,

Implements lear nings: document successes and points for improvement so that they can be implemented or improved in future procurement activities.

Whilst there is a wealth of standards, legislation, and guidance available for companies to use when integrating nature-positive solutions into the early stages of infrastructure developments, several gaps and challenges remain that limit this uptake. This chapter aimed to summarise the key information available to companies and concludes in identifying three critical areas where additional focus or action is needed to drive the uptake of nature-positive solutions.

Firstly, there is a noticeable scarcity of publishable case studies and examples where nature-positive solutions have been incorporated into the early stages of infrastructure developments. This may be attributable to the topic’s

infancy and/or lack of prioritisation compared to other sustainability issues, but the high prevalence of non-disclosure agreements also indicates that there is a lack of information and knowledge sharing taking place currently.

Secondly, it seems apparent that companies might perceive implementation of non-mandatory guidance and frameworks as time consuming or expensive, however, the benefits to both the company and the broader environment can be significant.

Thirdly, to ensure successful integration of nature-positive solutions into early stages of infrastructure developments, it is essential for companies across all sectors to collaborate in sharing information and knowledge, to foster a deeper understanding. Government and regulator intervention to make nature-positive solutions compulsory will also enhance engagement with the topic among companies and stakeholders.

Despite the existing gaps there have been notable advancements discussed throughout this chapter. There is enhanced awareness for the need to increase the uptake of such solutions and innovative methodologies and standards for supporting companies as they undertake early adoption are being developed. Examples of integration of nature-positive solutions into operations from other sectors and project stages are also available to explore. While acknowledging the ongoing need for refinement and broader adoption in the infrastructure sector, these achievements signal a promising trajectory towards more sustainable and harmonious infrastructure development practices that prioritise the preservation and enhancement of nature.

1. Ecology by Design. Biodiversity Mitigation Hierarchy Explained. Available at: https://www.ecologybydesign.co.uk/ecology-resources/biodiversity-mitigation-hierarchy

2. HM Treasury. (2013). Infrastructure Carbon Review. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c9803ed915d12ab4bbd33/infrastructure_ carbon_review_251113.pdf

3. International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) (2017). ISO 20400:2017 Sustainable procurement (Guidance). Available at: https://www.iso.org/ standard/63026.html

4. ISO (2010). ISO 26000: 2010 Social responsibility (Guidance). Available at: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html

5. The World Bank (2024). QII Principles. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/quality-infrastructure-investment-partnership/qii-principles

6. The World Bank (2017). Environment and Social Framework. Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/837721522762050108-0290022018/ original/ESFFramework.pdf

7. United Nations Environment Programme (2022) Convention on Biological Diversity. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en. pdf

8. FAST-Infra Label https://www.fastinfralabel.org/

9. The Heads of procurement at Multilateral Development Bank (2023). Joint Statement on Sustainable Procurement Initiatives. Available at: https://www.adb. org/sites/default/files/page/559571/mdb-hop-joint-statement-sustainable-procurement-initiative.pdf

10. ADB (2021). Sustainable Public Procurement (Guidance Note on Procurement). Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/sustainable-public-procurement.pdf

11. Certification — Blue Dot Network https://www.bluedot-network.org/

12. HM Treasury (2022). The Green Book – Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1063330/Green_Book_2022.pdf

13. The White House (2022). Opportunities to Accelerate Nature-Based Solutions: A Roadmap for Climate Progress, Thriving Nature, Equity, & Prosperity. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Nature-Based-Solutions-Roadmap.pdf

14. International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group (2012). Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability. Available at: https://www.ifc. org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2010/2012-ifc-performance-standards-en.pdf

15. European Commission (2022). Corporate sustainability due diligence. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32022L2464

16. German Federal Government (2023). German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act

17. United Kingdom Parliament (2021). Environment Act 2021. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/30/contents/enacted

18. United Kingdom Parliament (2024). Commercial organisations and Public Authorities Duty (Human Rights and Environment) Bill. Available at: https://bills. parliament.uk/bills/3527

19. US Federal Government (Chapter 1 of Title 48 of the Code of Federal Regulations). Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-48/chapter-1

20. Australian Government, Department of Finance (2022) Commonwealth procurement Rules. Available at: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/ files/2022-03/Commonwealth%20Procurement%20Rules%20-%201%20July%202022%20-%20advanced%20copy.pdf

21. Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (2022) Government Procurement Law. Available at: http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/englishnpc/ Law/2007-12/06/content_1382108.htm

22. People’s Republic of China Government (2023). Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive.

23. Indian Government (2023). Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting Directive.

24. Sustainable Procurement Pledge https://spp.earth/

25. UN Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

26. Supply Chain Sustainability School. Available at: www.supplychainschool.co.uk

27. FIDIC (2021). FIDIC Climate Change Charter. Available at: https://issuu.com/fidic/docs/climate_charter_with_foreword

28. Sustainable Procurement Pledge - Considering nature and biodiversity in your supply chain: #9 - Discussion on how to consider nature and biodiversity in your supply chain Available at: youtube.com

29. PAS 2080 (2023). Available at: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/insights-and-media/insights/brochures/pas-2080-carbon-management-in-infrastructureand-built-environment/

30. Source: AECOM, adapted from ISO 20400, Figure 5.

The report was developed by AECOM, authored by Harry Bettinson, Emily Ghedia, Stephen Perkins, Milica Apostolovic, Emily Le Cornu and Amanda Wharton. Evan Freund, Kate Newman from WWF reviewed and provided inputs into the draft report, as well as Graham Pontin, Basma Eissa, and Italo Goyzueta from FIDIC, and Robert Spencer provided guidance during the Playbook development. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support from numerous colleagues from both WWF, FIDIC and AECOM for their contributions and comments on the report, as well as the representatives from the organizations that provided case studies.

AECOM (2024) A Playbook for Nature-Positive Infrastructure Development. Published by FIDIC.

This document was produced by FIDIC and is provided for informative purposes only. The contents of this document are general in nature and therefore should not be applied to the specific circumstances of individuals. Whilst we undertake every effort to ensure that the information within this document is complete and up to date, it should not be relied upon as the basis for investment, commercial, professional or legal decisions.

FIDIC accepts no liability in respect to any direct, implied, statutory and/or consequential loss arising from the use of this document or its contents. No part of this report may be copied either in whole or in part without the express permission of the authors in writing.

WWF® and ©1986 Panda Symbol are owned by WWF. All rights reserved.

Copyright FIDIC © 2024

Published by

International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) World Trade Center II P.O. Box 311 1215 Geneva 15, Switzerland

Phone: +41 22 568 0500

E-mail: fidic@fidic.org

Web: www.fidic.org

Technical Partner: