4 minute read

Who is good at what, no matter their title or role? Find and use the expertise among us

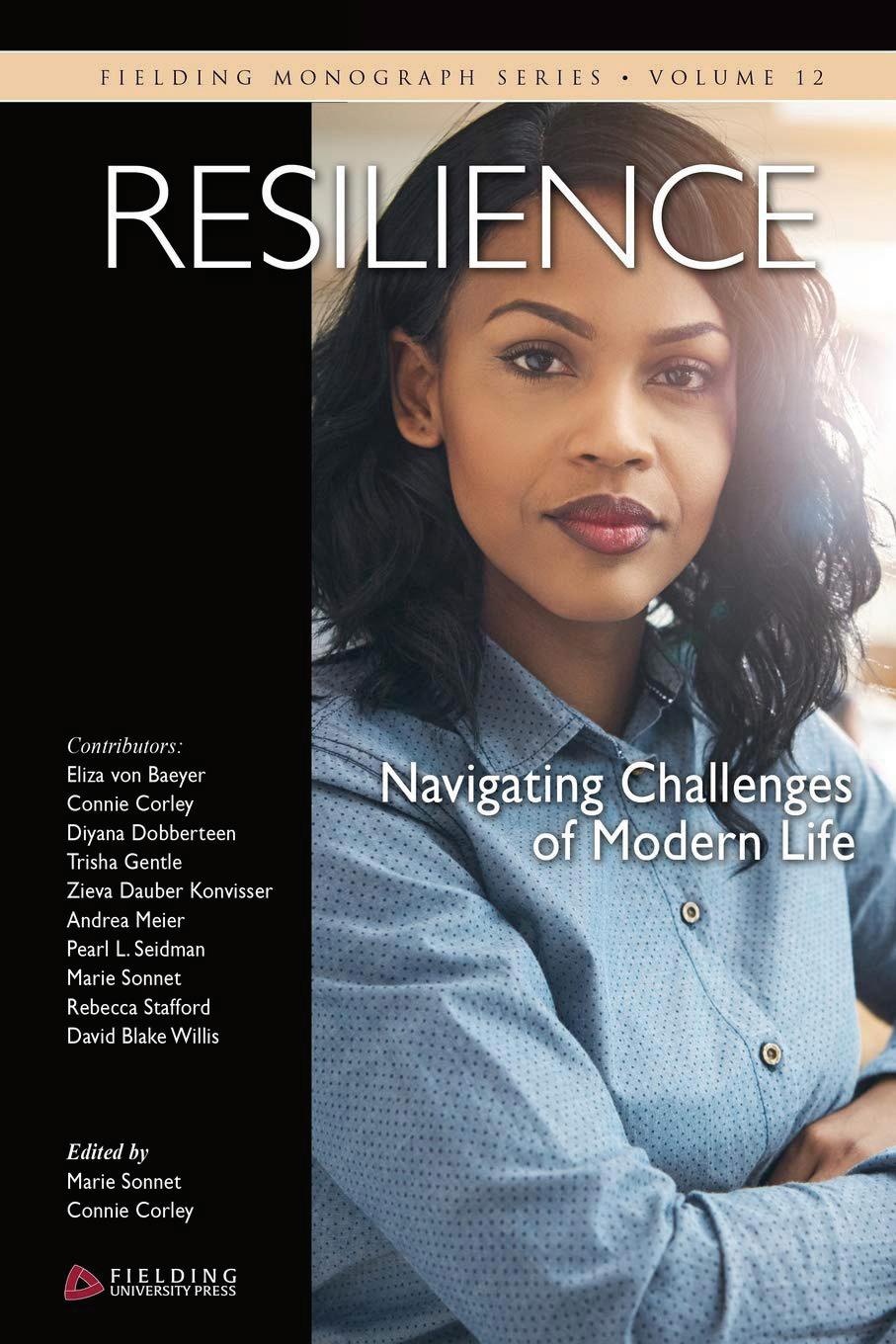

RESILIENCE IN CHALLENGING TIMES Fielding scholars share a diverse set of findings By Alum Marie Sonnet, PhD and Faculty Connie Corley, PhD

Resilience is a component of breaking through, whether breaking through a structural barrier, a state of mind, or an individual circumstance. As societies across the globe tackle the challenges of 21st century phenomena, such as pandemics and climate change, and grapple with forces like technological change and globalization, resilience has become a vital collective characteristic.

To examine this, in 2019 we coedited the monograph, Resilience: Navigating the Challenges of Modern Life , published by Fielding University Press.

Six articles by ten authors use original academic research to analyze and discuss core aspects of resilience in practice, deepening our understanding of a profound and promising human attribute and promoting more research for evidence-based applications.

The authors examine resilience ranging from an adaptive individual response to change and adversity, to organizational and community responses that can foster sustainability, yet innovate, and generate shared learning opportunities.

Being “resilient” has become an everyday adjective. To be effective in studying and building resilience, scholars, educators, and practitioners must experience deeper understanding and engage with more evidence across a range of applications. Applying resilience in practice calls for detailing what it means, how it is observed and assessed, where it is applied, if or why it offers value, and how it can be strengthened. These were the goals of the monograph.

The authors explore adaptation and growth experiences of social actors within the boundaries of particular ecosystems and problems – cultural, socioeconomic, geographic, organizational, political, and communal. They offer a scan of how the properties of resilient people and systems work, increasing our awareness of the complexity and variety of the resilience concept.

In Resilience and Vulnerability in Aging Holocaust Survivors and their Descendants ,

Zieva Dauber Konvisser

describes resilience across generations in response to searing trauma endured during the Holocaust.

Rebecca Stafford and

Andrea Meier , authors of Trajectories of Resilience for Whistleblower Psychological Trauma, discuss the resilience and recovery from trauma experienced by whistleblowers, noting that roughly 50 to 60 percent of Americans are exposed to some kind of significant, traumatizing stressor in their lifetimes. (See related article on page 15.)

Trisha Gentle wrote Voices of Women: Oppression and Resilience, which examines the resilience of women who have experienced abuse and oppression.

Marie Sonnet’s Employeebuilt Organizational Resilience Capacity: Getting to Specific Beliefs and Behaviors, explores organizational resilience capacity as a strategic asset employees use as they work together to create a “storehouse of capabilities.”

Ecotones: How Intersectional Differences Spur Adaptation and Resilience, written by Pearl L. Seidman, details the experience of cultural connectors who foster resilience “at the edges” of a Korean American community in Maryland.

How older adults and former gang members build bridges to community resilience through a storysharing process is detailed in Cruzando Puentes/Crossing Bridges: Building Resilience through Communitas, a collaboration by Connie

Corley, David Blake Willis, Diyana Dobberteen,

and Eliza von Baeyer. Collectively, the authors discuss resilience as both a valuable capacity to be fostered in preparation for change and adversity, and as an activated capability for growth in complex, and even dire, circumstances. The dynamics of resilience vary from individual work (Gentle; Stafford & Meier), in families (Konvisser), in organizations (Sonnet), and in communities (Corley, Willis, Dobberteen, & von Baeyer; Seidman).

While resilience is most often presented as a positive characteristic, there are different findings as well. One paradox of resilience is that it is often most visible amid tension, turbulence, and trauma. Another is that it proliferates as the result of adversity. Yet another is that resilience can reside in persistent forces and entities with corrupt, biased, or evil intent.

Seidman observes: “Without tension there is no reason to adapt or build adaptive potential. Tension was a trigger for individual and collective elasticity—in behavior, ways of seeing, social networks, and innovation.” She acknowledges that growth depends on friction invokes viewing resilient human systems as complex, adaptive, socioecological systems.

All provoke profound human responses. Konvisser summarizes: “While they do not forget their traumatic experiences, many survivors are able to integrate and own the painful emotions of their situation, make them part of their story, and live with them in a productive way.” There is enormous power in such a capability.

Gentle observes in her study of oppressed women: “There was a consistent surfacing of coping, understanding, adaptation, and even healing that demonstrates resilience.” Corley et al. find in Los Angeles that “…the yearnings and struggles of diasporic communities commemorate historical memory, power, and resistance that have cultural identity at the core of the changes we witness over time – reflections of ethnicity, race, and gender in particular eras.”

Konvisser concludes, “While each experience is unique, by bringing forth and understanding some of the common qualities and sources of strength that help people cope with the tragedy and uncertainty and survive the long-term impacts of extreme prolonged trauma, we provide valuable insights and evidence for the traumatized individuals themselves; for their families, friends, and communities supporting their recovery.” •

Coauthors Connie Corley (top) and Marie Sonnet (bottom), and their new book (middle).