The Florida Center for Cybersecurity

The Office of the National Cyber Director

REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

RESPONSE TO Cyber Workforce, Training, and Education

CYBER WORKFORCE

Recruitment and Hiring

CYBER WORKFORCE

CyberWorks

Recruitment and Hiring

CyberWorks

The Florida Center for Cybersecurity (Cyber Florida) is proud to offer CyberWorks, a cybersecurity workforce development initiative to help address our nation’s critical cyber talent shortage by preparing career-changers for new roles as cyber defense analysts. Through expert online instruction and curriculum aligned to the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework work role of Cyber Defense Analyst, this intensive, 19-week program prepares nontraditional adult students to enter the cybersecurity workforce as Tier 1 Security Operation Center (SOC) Analysts. Full-tuition grants are available for Florida residents who are legally able to work in the United States and who have achieved at least a high school diploma or GED equivalent. With the goal of diversifying the cybersecurity workforce, priority consideration for enrollment is given to applicants who are transitioning military veterans and first responders ( law enforcement, firefighters, EMT/paramedics, and 911 dispatchers) as well as members of historically underrepresented demographic groups such as women, people of color, and people with disabilities. The graphic below illustrates the significant and ongoing increase in interest that the CyberWorks program has garnered over the past three years

The Florida Center for Cybersecurity (Cyber Florida) is proud to offer CyberWorks, a cybersecurity workforce development initiative to help address our nation’s critical cyber talent shortage by preparing career-changers for new roles as cyber defense analysts. Through expert online instruction and curriculum aligned to the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) Cybersecurity Workforce Framework work role of Cyber Defense Analyst, this intensive, 19-week program prepares non-traditional adult students to enter the cybersecurity workforce as Tier 1 Security Operation Center (SOC) Analysts. Full-tuition grants are available for Florida residents who are legally able to work in the United States and who have achieved at least a high school diploma or GED equivalent. With the goal of diversifying the cybersecurity workforce, priority consideration for enrollment is given to applicants who are transitioning military veterans and first responders (law enforcement, firefighters, EMT/paramedics, and 911 dispatchers) as well as members of historically underrepresented demographic groups such as women, people of color, and people with disabilities. The graphic below illustrates the significant and ongoing increase in interest that the CyberWorks program has garnered over the past three years.

The coursework is delivered online through an e-book with corresponding modules of presentations, assignments, and quizzes; hands-on learning exercises through a virtual lab; and two live, instructor-led class discussion sessions each week. The workload is equivalent to an upper -level undergraduate college course with manageable deadlines for working students. Participants enjoy ongoing support from a dedicated program advisor who helps learners stay on track. Students who successfully complete the course will receive vouchers to take the CompTIA Network+ and CompTIA Cybersecurity Analyst (CySA+) certification exams at no cost.

The coursework is delivered online through an e-book with corresponding modules of presentations, assignments, and quizzes; hands-on learning exercises through a virtual lab; and two live, instructor-led class discussion sessions each week. The workload is equivalent to an upper-level undergraduate college course with manageable deadlines for working students. Participants enjoy ongoing support from a dedicated program advisor who helps learners stay on track. Students who successfully complete the course will receive vouchers to take the CompTIA Network+ and CompTIA Cybersecurity Analyst (CySA+) certification exams at no cost.

To remove the barriers common to studying cybersecurity, our program is held virtually so working professionals can study around their work and family responsibilities. The CyberWorks program is also offered free of charge to remove the financial burden. Funding for this program is made possible through a grant from the National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity Education (NCAE-C) as designated by the National Security Agency (NSA) to establish a national, certificate-based

To remove the barriers common to studying cybersecurity, our program is held virtually so working professionals can study around their work and family responsibilities. The CyberWorks program is also offered free of charge to remove the financial burden. Funding for this program is made possible through a grant from the National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity Education (NCAE-C) as designated by the National Security Agency (NSA) to establish a national, certificate -based

cybersecurity workforce development program called CyberSkills2Work. Under the University of West Florida’s guidance as the coalition lead, CyberSkills2Work was established in 2020 and comprises nine educational institutions that are designated NCAE-C schools. Each institution offers free, certified and credentialed cybersecurity courses that prepare learners for entry-level roles in the cybersecurity field.

CyberWorks actively recruits adult learners for two separate cohorts, which are run concurrently:

• New Skills for a New Fight: Transitioning military veterans and first responders (law enforcement officers, firefighters, 911 dispatcher, EMT/paramedics)

• Community Cohort: Individuals who identify as members of demographic groups that have been historically underrepresented in cybersecurity, including women, people of color, and people with disabilities.

Career Development and Retention CyberWorks

In addition to technical instruction, CyberWorks participants benefit from various career readiness experiences such as professional resume and interview guidance, coaching to enhance LinkedIn profiles, job search and networking advice, industry insight from cybersecurity professionals during live guest speaker sessions, a cybersecurity workforce skills analysis, and one-on-one mentoring with a cybersecurity talent acquisition professional. Cyber Florida takes advantage of our extensive network of partners and supporters throughout the state to provide students with numerous perspectives of what it is like to not only work in the field as a professional but also as a leader and even what human resources teams are looking to hire. At the conclusion of the program all participants and program alumni are invited to an in-person networking reception that connects participants to potential employers. CyberWorks caters to these populations of career changers by providing them with customized support, relevant resources, and practical opportunities for them to learn cyber defense fundamentals, as well as participate in workforce development experiences. Program participants report feeling supported throughout the program and confident that they are well-prepared upon conclusion to launch their job searches.

We recommend, at a minimum, to maintain funding for the CyberSkills2Work program so the nine institutions may continue to offer no-cost training and certification to career-changers. However, additional funding would allow the program to be expanded and offered at additional NCAE-C schools across the country. Unfortunately, limited funding inhibits our ability to accept all eligible applicants. An increase in funding would allow us and other participating NCAE-C institutions to accept larger cohorts of future cybersecurity professionals.

DIVERSITY, EQUITY, INCLUSION, AND ACCESSIBILITY (DEIA) DEIA in Cyber Training, Education, and Awareness CyberWorks

Women; Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC); and professionals with visible or invisible disabilities continue to be underrepresented in cybersecurity, an issue that still needs to be addressed by government leaders, industry, non-profit organizations, higher education, and K-12 public schools. As a nation, we cannot mitigate the workforce crisis without engaging these groups in the workforce at higher rates. It is crucial that employers and educators develop new

to improve diversity. The U.S. cyber workforce is composed of only 26% racial-ethnic minorities (9% Blacks, 4% Hispanics, 8% Asians, 1% Native Americans, 4% Others)1 . Moreover, few from that group have obtained technical, higher education, or corporate leadership positions. Another issue is that few cybersecurity companies invest their time and resources in hiring neurodivergent professionals, such as people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and others with visible and invisible disabilities.

strategies, practices, and processes to improve diversity. The U.S. cyber workforce is composed of only 26% racial-ethnic minorities (9% Blacks, 4% Hispanics, 8% Asians, 1% Native Americans, 4% Others)2. Moreover, few from that group have obtained technical, higher education, or corporate leadership positions. Another issue is that few cybersecurity companies invest their time and resources in hiring neurodivergent professionals, such as people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and others with visible and invisible disabilities.

Through our daily engagement with historically underrepresented communities, cyber recruiters, and local and national companies, we have identified some challenges, best practices, and recommendations that apply to the inclusion of a diverse cyber workforce:

• It is necessary to deconstruct stereotypes about underrepresented and minoritized groups in STEM fields, particularly women and people with disabilities, beginning in K-12 education and continuing in higher education;

To address these issues, Cyber Florida made a significant effort to reduce the disparity and prepare underrepresented and minoritized professionals from low-socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds to advance their technical skills and enter the cybersecurity industry. Since our CyberWorks program was re-launched four years ago, Cyber Florida has implemented a concerted effort to encourage underrepresented communities from diverse socioeconomic, cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds to apply through targeted outreach. As detailed above, minoritized students who are accepted into the program receive a 19-week free intensive training program, and after completing the course, Cyber Florida provides them with all the tools required to become Tier 1 Security Operation Center (SOC) analysts (post-training with hands-on activities, Networking and CySA+ COMPTIA vouchers). Cyber Florida works to ensure that the program meets the specific needs of women, BIPOC, people with visible and invisible disabilities, transitioning veterans, and first responders, such as providing individual 1:1 mentoring to improve students’ networking and leadership skills, update their resumes, develop their elevator pitches, and build confidence during the job application process.

To address these issues, Cyber Florida made a significant effort to reduce the disparity and prepare underrepresented and minoritized professionals from low- socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds to advance their technical skills and enter the cybersecurity industry. Since our CyberWorks program was relaunched four years ago, Cyber Florida has implemented a concerted effort to encourage underrepresented communities from diverse socioeconomic, cultural, ethnic, and racial backgrounds to apply through targeted outreach. As detailed above, minoritized students who are accepted into the program receive a 19-week free intensive training program, and after completing the course, Cyber Florida provides them with all the tools required to become Tier 1 Security Operation Center (SOC) analysts (post-training with hands-on activities, Networking and CySA+ COMPTIA vouchers ). Cyber Florida works to ensure that the program meets the specific needs of women, BIPOC, people with visible and invisible disabilities, transitioning veterans, and first responders, such as providing individual 1:1 mentoring to improve students’ networking and leadership skills, update their resumes, develop their elevator pitches, and build confidence during the job application process.

• In addition to providing more accessibility to workforce programs and job employment, historically underrepresented groups need more accessible tools to participate in hands-on experiences;

• The high cost of daycare prevented some mothers from completing our in-person program; programs should provide resources to mothers from low-income backgrounds who are striving to complete their cyber education;

• There is a need for supportive strategies for stay-at-home mothers who paused their careers to take care of their families but are now trying to re-enter the cybersecurity workforce;

• Because of the socioeconomic situation of many applicants who are homeless veterans of color, they were unable to complete their program;

• The government and industry should offer initiatives to motivate companies to hire, particularly for entry-level positions, individuals from underrepresented communities;

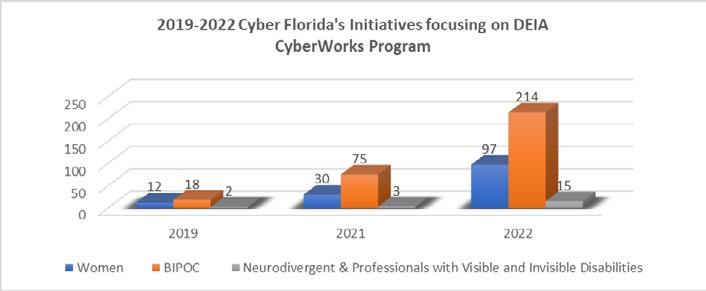

In the table below, we map out how, over the years, we have achieved a considerable increase in enrolling historically underrepresented minoritized applicants from low-income backgrounds to the program.

In the table below, we map out how, over the years, we have achieved a considerable increase in enrolling historically underrepresented minoritized applicants from low-income backgrounds to the program.

Cyber Florida also implements curriculum and practi ces designed to create a safe environment where students feel welcome and represented. In every cohort, we invite professionals from a variety of ethnicracial-linguistic backgrounds to share their stories of how they got into the field and what hard and soft skills students need to succeed. Furthermore, Cyber Florida has established partnerships with non-profit

• Cybersecurity positions are in high demand, but one of the challenges is motivating companies to hire security professionals with no prior experience, who, according to our experiences, tend to be from underrepresented groups;

• It can be challenging for students to find jobs in the cyber industry, particularly those with children;

• Online learning appears to attract a more diverse group of professionals. After revamping from an in-person to an online program due to COVID-19, our program has increasingly received applications from professionals with disabilities (physical disabilities, ADHD, Autism, PTSD, visual impairment, language disorder, anxiety, and others);

• There is a need for additional empirical research that examines the daily experiences of professionals with disabilities in cybersecurity companies and cyber education programs. Listening to their experiences is key to building a supportive environment and increasing their hire rate;

• The cybersecurity industry needs multicultural training to reduce workplace discrimination (hiring process, leadership positions, gender disparity wages, etc.);

• More effective apprenticeship and internship programs would help students gain valuable hands-on experience and prepare them to find a long-term career.

NCAE Cyber Games

In 2020, Cyber Florida partnered with Mohawk Valley Community College in Utica, NY, to win a grant award from the National Security Agency’s National Centers of Academic Excellence in Cybersecurity (NCAE-C) program office to establish a national collegiate cyber competition program for NCAE-C member schools. The Cyber Florida/Mohawk Valley (CF/MV) proposal was selected for funding because of its emphasis on creating access to the field for newcomers and members of underrepresented groups. The world of cyber competitions can be intimidating to newcomers—there is a well-established “hacker culture” at work with its own terminology, humor, and unwritten rules of engagement. It is an overwhelmingly

male-dominated space and can feel unwelcoming to women and members of minority groups who have not historically participated in this space. Cyber competitions, however, are also a critical resume-builder for aspiring cybersecurity professionals and often serve as recruiting events for major employers, so it is imperative that aspiring professionals of all genders and ethnicities have access to these events to improve diversity in the field.

The CF/MV team designed the NCAE Cyber Games as the first-ever national collegiate competition for students who have never competed before. The competition was presented as a learning platform for new competitors with plenty of tutorials, an open sandbox for learning and practicing, and a Discord hub to facilitate community-building. Outreach efforts included working with college and university faculty advisors to reach out to and encourage students who are not already involved in competitions. Promotional materials featured women and students of color and language was encouraging and welcoming. The materials acknowledged the hesitation that many students feel when considering whether to compete and assured students that they would only be among other new competitors and educators who want to see them succeed.

Faculty advisors were excited to have a channel for new students to develop and build competition skills and created “farm teams” of new and less-seasoned competitors who were coached and mentored by schools’ established hacker teams. In addition to team recognition based on points earned in the competition, individual students were selected by teammates as Most Valuable Teammate and Most Improved Teammate to help keep the focus on skill development and team building.

We are proud to report that more than 500 students from 55 colleges and universities across the country participated, with roughly 36% identifying themselves as members of underrepresented groups. Additionally, while participation from women hovered near 15% percent, 22% of the students selected as Most Improved Teammate were female, demonstrating the inclusive spirit achieved by this event. This project was received as a resounding success by the National Secure Agency and stands as one of only two projects selected to be extended for two years at the full funding amount requested.

TRAINING, EDUCATION, AWARENESS

Training and Postsecondary Education

Postsecondary Education

Based on our experiences with multiple successful stakeholders that have made a tangible impact within the broad area of cybersecurity training, education, and awareness in K-12 and postsecondary education in the state of Florida (and nationwide), we are pleased to offer some strategies for critical focus areas identified in the RFI.

There is a critical need to understand the diversity in cybersecurity training imparted across the spectrum. Our experiences have revealed that curricula in certain schools and colleges are more theory/ foundations-focused, while others cover more hands-on topics. Both fulfill critical national needs; however, we believe that gaps could be closed to create a more comprehensive and uniform curriculum based on carefully orchestrated corrective measures. Exit surveys are a great way of capturing the strengths and weaknesses of programs, as is soliciting feedback from local industry. Sharing such information statewide can provide a comprehensive overview of where students are in the skills landscape needed for the jobs market. Examples of corrective action could be one or more of the following: updating syllabi, funding to purchase hands-on equipment, funding for students to take certification exams, and industry visits to campuses to create visibility.

To identify initiatives and models in training and education, we can refer to the success of the BS in Cybersecurity program at University of South Florida, which started off with a handful of students four years ago and has now grown to more

than 560 students. The program carefully covers a mix of foundations (both in cybersecurity and computing in general) early in the program before transitioning to more hands-on courses. These efforts culminate in a rigorous senior project course. Specifically, the curriculum is modeled after the ACM/IEEE/IFIP Joint Task Force on Cybersecurity education and designed following ABET guidelines. Building programs on these foundations provides scalability and industry-ready graduates. The program periodically assesses student outcomes in core courses, with faculty members reviewing whether identified student outcomes are being met and taking corrective action to enhance the course offerings. This rigor in planning and execution is critical for initial student success and serves as a platform for scaling up cybersecurity education in the long run. These are critical characteristics and features of programs that have succeeded in scaling effective cybersecurity skills development. Furthermore, lessons learned from such flagship programs, if effectively disseminated, also serve to increase the number, rigor, and quality of cyber-related educational programs across higher education statewide, and possibly nationwide.

In order to make a career in cyber an enticing and approachable opportunity for more postsecondary students, we recommend creating pipelines for students to pursue industry internships. Another recommendation is to integrate local cyber industry professionals into advisory boards of departments offering cyber programs to keep the curriculum current and industry focused. In order to enable learners to overcome cost and other barriers to an education and training in cyber and related fields, we recommend programs specifically catering to low-income groups earn cyber certifications. The education & training, coupled with industry certifications will help students enter the cyber workforce. Of course, there are still barriers to being able to pay for certification exams, but this could be overcome via funding specifically gleaned to offset those costs towards enhancing cyber workforce in local communities and the state. Another potential opportunity is to invest in high-schools and community colleges to enhance their programs to be more hands-on, which will improve certification outcomes for students.

We are aware that there is an increasing shortage of trained and qualified cybersecurity faculty across the nation, and there is a need to increase the skills and number of faculty needed to expand cyber educational programs across the nation. This is a significant barrier to realizing workforce development in the area. While producing graduates with masters and doctoral degrees is one approach to overcome these barriers, we recommend an alternate approach, that fits nicely with the overall goal of skilled workforce development. We recommend state-wide programs that specifically solicit industry experts that are close to retirement and want to try something exciting – as in teaching younger people. A rigorous program for six months to train these people in undergraduate teaching may be a great way to fill up gaps in faculty position in cyber (and we are not aware of such programs, or at least ones that are established). We believe that such efforts will not only increase the generation of skilled workforce, but also make them shovel-ready for the industry, since they are taught by industry experts with experience.

To summarize, our recommendations of integrating theory/ foundations with practical/hands-on experiences, overcoming barriers to low-income groups and certifications, augmenting existing curriculums in schools and colleges with equipment support, curriculum sharing to learn from successful programs, involving industry people as cyber advisors and faculty are among the best practices in ensuring graduates of programs in cybersecurity are fully prepared for work in the field.

Finally, to assess the value of investments in cyber training and education, we recommend extensive exit surveys, alumni surveys, feedback from peer programs on curriculum, employer surveys, and feedback from board members for improvement. Likewise, accreditation from established organizations like ABET is a powerful way to judge a program’s rigor.