CV1_A)January US SUBS cover Final2rev

11/24/08

4:19 PM

Page 1

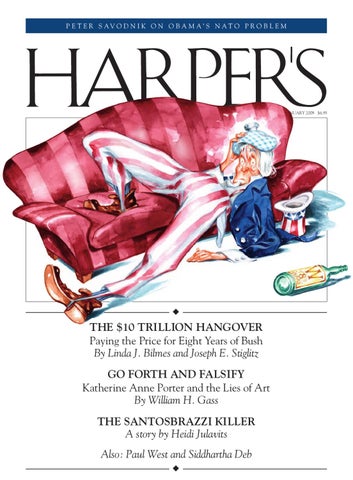

P E T E R S AV O D N I K O N O B A M A’ S N AT O P R O B L E M

HARPER’S MAGAZINE / JANUARY 2009 $6.95

◆

THE $10 TRILLION HANGOVER Paying the Price for Eight Years of Bush By Linda J. Bilmes and Joseph E. Stiglitz GO FORTH AND FALSIFY Katherine Anne Porter and the Lies of Art By William H. Gass THE SANTOSBRAZZI KILLER A story by Heidi Julavits Also: Paul West and Siddhartha Deb ◆