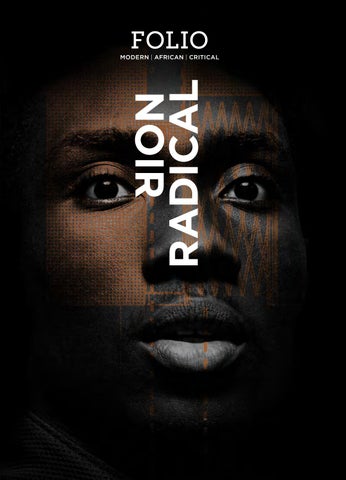

Supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, FOLIO is Africa's newest, peer-reviewed journal of architecture exploring issues, ideas, built projects, criticism and speculative writing on a wide range of topics concerning architecture, urbanism and creative practice both at ‘home’ and abroad. In this second volume, thirty-eight contributors showcase some of the most innovative and critical writing, projects and reflections coming ‘out of Africa’ and the Diaspora today.