5 minute read

Road Trip to the LBJ Ranch in Stonewall, Texas

By Barbara Redding

Advertisement

S

tretching along the fertile Pedernales River Valley in the Hill Country of Central Texas, Stonewall is a quiet community of cattle ranches, peach orchards, and vineyards.

Its best-known resident was Lyndon Baines Johnson, the 36th U.S. president whose ranch became the “Texas White House” in the 1960s. Though Texas has claimed two presidents since then—George H.W. and George W. Bush —Johnson is the only one who was born and who died in Texas.

Presidential history was far from my mind when I set off from Austin on a 60-mile road trip west to the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park in Stonewall on a searing hot August day. After five months of coronavirus quarantining in my Austin bungalow, with its equally petite yard, I just wanted to escape to the country.

Subtle beauty of the ranch

In the process, however, I rediscovered the subtle beauty

of the rambling ranch that shaped and comforted a president facing a different set of world problems.

Road trips to the Hill Country are customary for urban Texans like me. It’s where we take friends in the spring to marvel at the beauty of Texas wildflowers and to raise a glass of wine on the outdoor patio of one of the Hill Country’s many wineries. (Texas is the fifth largest wine producer in the U.S.) Fredericksburg, with its oompah German heritage and cozy bed-and-breakfasts, is the primary destination. Just a dozen miles east, Stonewall, with all of 500 residents, is garnering more notice as new wineries, distilleries, and attractions fill in the countryside.

Coronavirus closes Texas wineries

But this was no typical road trip. The ranch was open but most state businesses were closed when my companion and I packed the car with a picnic lunch, hand sanitizer, and masks.

Once we cleared the capital city’s burgeoning suburbs, we began to relax as farms and ranches stretched out around us. Fields dotted with prickly pear cacti and cedar trees glistened in soft shades of green and gold, in defiance of the relentless summer sun.

We cruised through Johnson City without stopping to visit LBJ’s boyhood home and the Johnson Settlement, where the president’s ancestors scratched out a living on a farm dating back to the 1800s. LBJ state park headquarters is there, but was closed.

Vineyards and peach orchards

I tried to count the signs for wineries that now line both sides of U.S. 290 between Johnson City and Stonewall. But I almost missed the entrance to the LBJ park. On my first visit as a new Texan more than 20 years ago, peach orchards outnumbered vineyards and the only way to see the ranch was on a tour bus.

Today the 600-acre ranch is open daily for free, selfguided driving tours. At the visitor center, where we picked up a ranch map and windshield pass, I noticed a cardboard cutout of the six-foot-four-inch-tall president. He, too, wore a mask.

Photos (Opposite, Top-Bottom): Pedernales River at LBJ Ranch ©LBJ Library; LBJ Ranch sign welcomes all; Reconstructed birthplace of Lyndon Johnson ©LBJ Library.; Air Force One-half at LBJ Ranch @LBJ Library; (This page, Top-Bottom): The Texas White House ©LBJ Library; Fences on LBJ ranch ©LBJ Library

From there, we followed the Pedernales River, past the spot where President Johnson drove a 1934 Ford Phaeton over the river along the dam. We took the conventional route across a bridge, where a stone sign greeted us with LBJ’s own words: “All the world is welcome here.”

A living, working ranch

“That’s still true today, especially during the pandemic”, said Vanessa M. Torres, a program manager with the national park. “We’ve become a more urban society so visiting a living, working ranch is a unique opportunity.”

LBJ’s beloved ranch is also one of the only presidential sites that take visitors from “the cradle to the grave site.” We felt the weight of history as we strolled beneath towering live oaks and pecan trees to the modest two-room home that was reconstructed on the site of the president’s original birthplace in 1908.

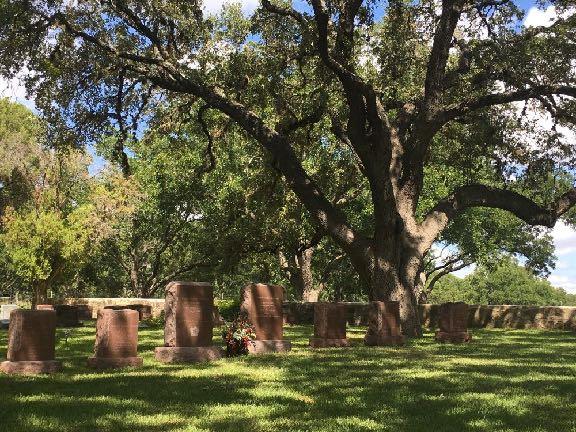

A soft breeze rustled the leaves as we crossed the road to the peaceful Johnson family cemetery. A tasteful granite stone bearing the presidential seal marks Johnson’s grave. His wife, Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson, lies next to him; her headstone etched with a single wildflower.

Roadside signs tell stories

From there the ranch road winds through acres of golden pasture land. Roadside exhibits tell stories about the president’s life. After stopping to read about LBJ’s affection for Hereford cattle, we spied dozens of chunky brown-and-white cows grazing contentedly.

The road loops around the Show Barn, where there is usually a newborn calf, and then runs parallel along the ranch’s landing strip. Though the visitor center in the hangar was closed, we parked to admire the Lockheed Jetstar, dubbed “Air Force One-half” by Johnson, because it was small enough to land on the runway.

We found a shady spot on the lawn of the former “Texas White House” for our picnic. As the river rippled past, I silently thanked LBJ for our escape— though temporary—from the stress of this deadly virus.

Photos (Top, L-R): LBJ cattle brand ©LBJ Library; Stare down with a Hereford; Hereford cow and egret on LBJ ranch ©LBJ Library; (Bottom): Graves of President and Mrs. Johnson in family cemetery.