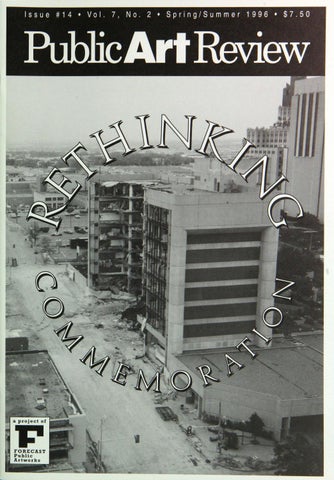

Issue

#14

• Vol.

7,

No.

2 • Spring/ Summe r 1996 •

$7.50

PublicArt Review a » • t« « « • i n it t i n it » aim ii ii ii ii ii ii

i-

I

*

I

Lrii

• £SI -

I? *v

1 -

*

Issue

#14

• Vol.

7,

No.

2 • Spring/ Summe r 1996 •

$7.50

PublicArt Review a » • t« « « • i n it t i n it » aim ii ii ii ii ii ii

i-

I

*

I

Lrii

• £SI -

I? *v

1 -

*