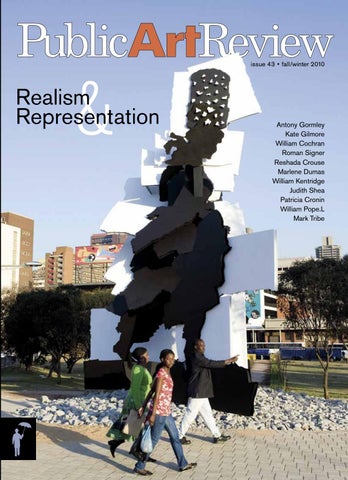

Realism & Representation

PAR43 explores the marked increase in the quantity + quality of representational public art in the US + abroad. Guest Editors Patricia Phillips & Nancy Princenthal present a selection of features focusing on realism, figurative sculpture, and public portraiture. Articles cover such concepts as “liberty” in post-apartheid Johannesburg, public art on a literal pedestal, reenactments of significant protest speeches, and two artists’ reflections on the concept of memorial.

According to Phillips and Princenthal, this issue's authors “address questions of how replication and substitution relate to realistic depiction. They accept the permeability of boundaries between live performance and figurative sculpture, and are interested in problems of simulation and reenactment. Room is found for photography and video in the public realm, and even for painting.”

Featured artists: Antony Gormley, Kate Gilmore, William Cochran, Roman Signer, Reshada Crouse, Marlene Dumas, William Kentridge + more.