Forest and Bird

NATURE’S HEROINES

Six unsung women of conservation and the difference they made

TE REO O TE TAIAO № 388 WINTER 2023

NEW ZEALAND’S INDEPENDENT VOICE FOR NATURE • EST. 1923 CREATE A BIRD-SAFE GARDEN SANCTUARY

COVER SHOT Puawānanga (Clematis paniculate). Rob Suisted. Our 1950s custom cover was inspired by issue 110 of Forest and Bird, published in November 1953, which also featured New Zealand’s native bush clematis.

PAPER ENVELOPE Pīwauwau rock wren. Jeremy Sanson RENEWAL Pepe para riki common copper butterfly. Donald Laing

EDITOR Caroline Wood E editor@forestandbird.org.nz

ART DIRECTOR/DESIGNER Rob Di Leva, Dileva Design E rob@dileva.co.nz

PRINTING Webstar www.webstar.co.nz PROOFREADER David Cauchi

ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES Karen Condon T 0275 420 338 E karen.condon@xtra.co.nz

MEMBERSHIP &

T 0800 200 064 E membership@forestandbird.org.nz

Thank you for supporting us! Forest & Bird is New Zealand’s largest and oldest independent conservation charity.

Join today at www.forestandbird.org.nz/joinus or email membership@forestandbird.org.nz or call 0800 200 064

Every member receives four copies of Forest & Bird magazine a year.

Forest & Bird is printed on elemental chlorine-free paper made from FSC® certified wood fibre and pulp from responsible sources.

CIRCULATION

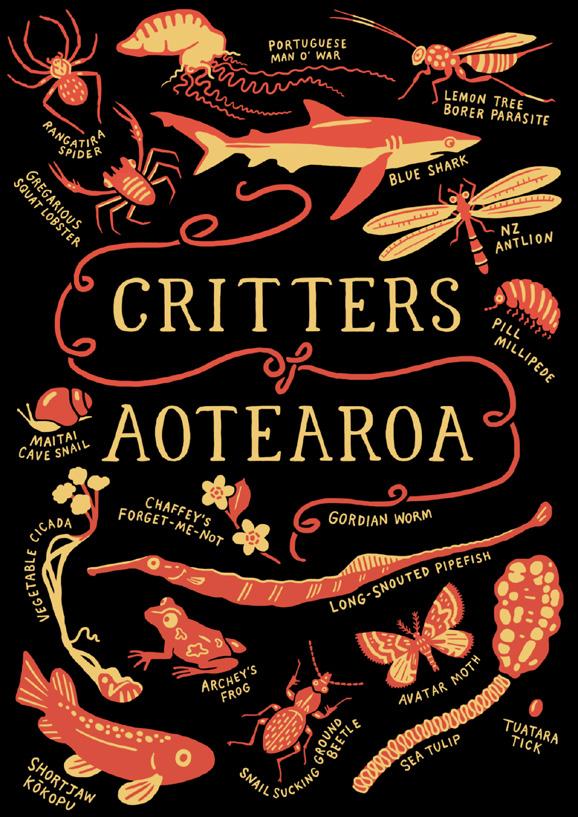

Forest & Bird is published quarterly by the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. Registered at PO Headquarters, Wellington, as a magazine. ISSN 0015-7384 (Print), ISSN 2624-1307 (Online). Copyright: All rights reserved. Opinions expressed by contributors in the magazine are not necessarily those of Forest & Bird. Contents ISSUE 388 • Winter 2023 Editorial 2 Lessons from the past 4 Letters + competition winners News 6 Round up of centennial events 8 Forest & Bird’s 2023 conference 10 New climate campaign, Time to stop trawling, Mining threatens kauri and freshwater 12 Te Kuha win, Glenbrook gain Cover 14 Backyard bird feeding guide 16 Keeping birds wild 17 Ready set count, Garden Bird Survey 18 Make your garden bird friendly 19 For the love of birds Climate 20 Listen to the land 23 The future won’t take care of itself 31 On the frontline Future conservation 24 Can genomics save hoiho? Biodiversity 28 Critters and Wikinerds 44 Still vanishing Forest & Bird project 32 Rewilding riflemen Centennial stories 34 Unsung women conservationists 42 Stamping our identity 54 Finding our voice 14 24

Pest-free NZ

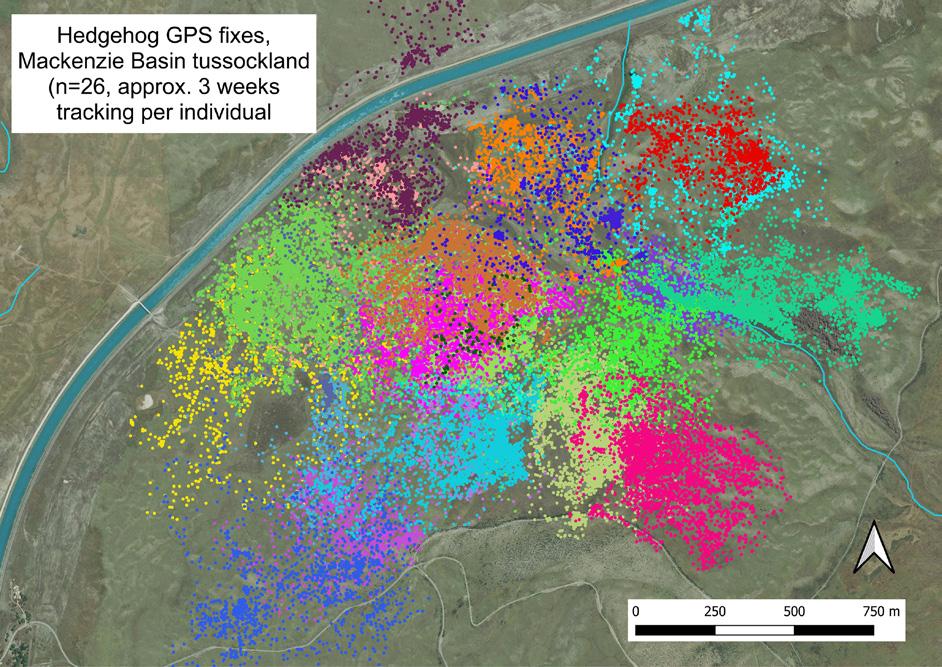

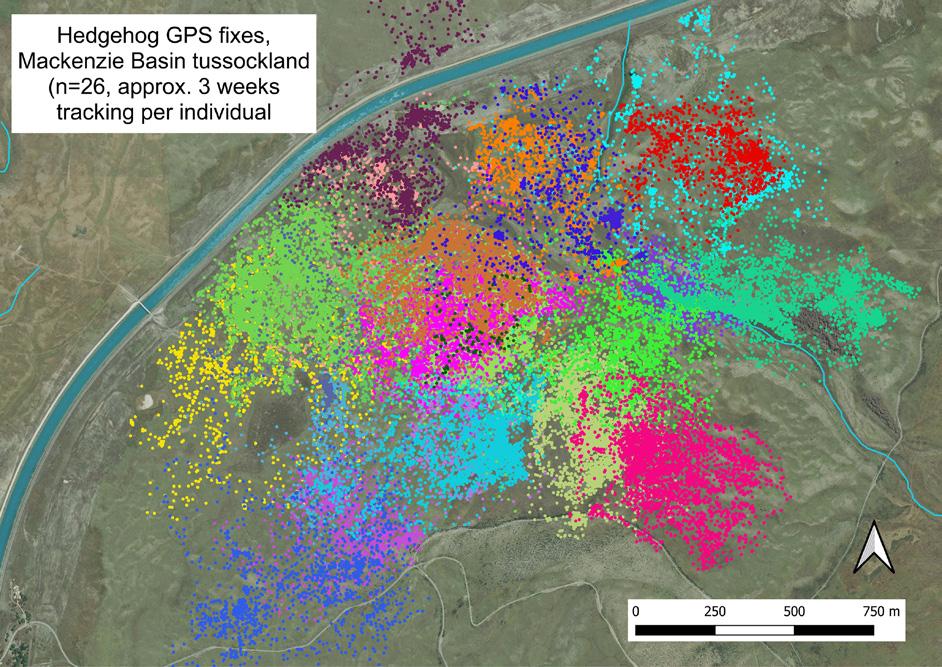

38 Hedgedevils: A prickly problem

Freshwater

40 Shine a light

Fundraising

41 Singing for birds and bush

Forest & Bird branch

46 For Arowhenua

Marine

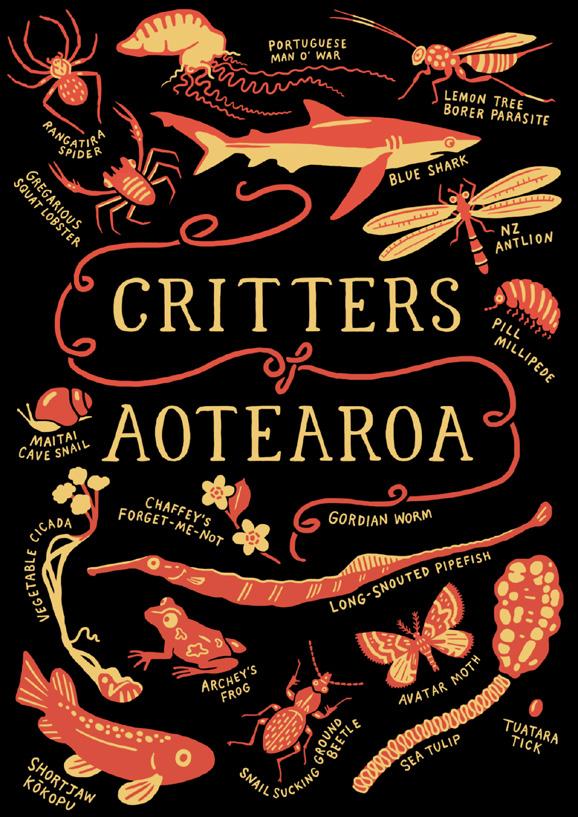

48 Dolphin delights

Special report

50 Protecting southern kauri (part II)

Photography

53 Top shots

Going places

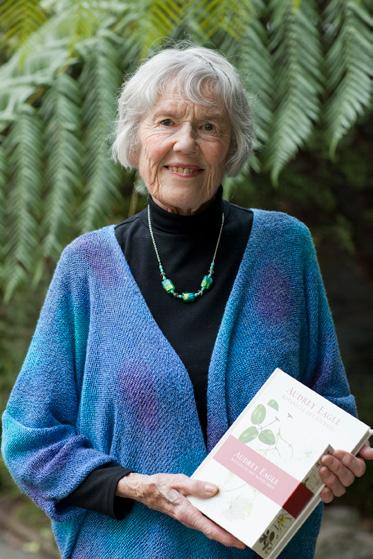

54 Auckland Whale and Dolphin Safari, Hauraki Gulf

Our partners

60 Cathy Hansby: Bird works

Tribute

61 Ken Catt: Marine life champion

Market place

62 Classifieds

Last word

64 A clever bird thing

Parting shot

IBC Bellbird and bee

CONTACT NATIONAL OFFICE

Forest & Bird National Office

Ground Floor, 205 Victoria Street

Wellington 6011

PO Box 631, Wellington 6140

T 0800 200 064 or 04 385 7374

E office@forestandbird.org.nz

W www.forestandbird.org.nz

CONTACT A BRANCH

See www.forestandbird.org.nz/ branches for a full list of our 50 Forest & Bird branches.

www.facebook.com/ ForestandBird

@forestandbird

@Forest_and_Bird

www.youtube.com/ forestandbird

Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society of New Zealand Inc. Forest & Bird is a registered charitable entity under the Charities Act 2005. Registration No CC26943.

PATRON Her Excellency The Rt Honourable Dame Cindy Kiro, GNZM, QSO Governor-General of New Zealand

CHIEF EXECUTIVE Nicola Toki PRESIDENT Mark Hanger TREASURER Alan Chow BOARD MEMBERS Chris Barker, Kaya Freeman, Kate Graeme, Richard Hursthouse, Ben Kepes, Ines Stäger CONSERVATION AMBASSADORS Sir Alan Mark, Gerry McSweeney, Craig Potton DISTINGUISHED LIFE MEMBERS Graham Bellamy, Linda Conning, Philip Hart, Joan Leckie, Hon. Sandra Lee-Vercoe, Carole Long, Peter Maddison, Sir Alan Mark, Gerry McSweeney, Craig Potton, Fraser Ross, Eugenie Sage, Guy Salmon, Lesley Shand

42 48

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

The sea floor is covered in a choking layer of silt, smothering and suffocating many forms of marine life. Every time the sea is rough or the swells increase, the disturbance lifts the fine pumice silt back into suspension to continue its deadly effect. It reduces the light reaching algae and seaweeds, causing them to perish … The world below the ocean surface is not seen by many and is easily and conveniently ignored by both authorities and the public. It’s the ongoing tragedy of the hills of Tairāwhiti and the moana that the silt-laden and slashladen rivers flow into.”

These words were written by Quentin Bennett in a Forest & Bird magazine article in November 1990. He was talking about the devastating impacts of Cyclone Bola on the marine environment, more than three decades before this year’s storms and floods in Te Tairāwhiti, Te Matau-a-Māui Hawke’s Bay, and Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.

The East Coast of the North Island, from Hawke’s Bay to the East Cape, has a history of extreme weather events. Its steep hillsides and geography mean high rainfall events have a bigger impact than in many other parts of our country.

Following Cyclone Bola in 1988, it was suggested taxpayer-funded managed retreat from key erosionprone lands in Te Tairāwhiti and planting of these areas would likely cost less than the payout from the next natural disaster to hit the region. But, other than

increased pine afforestation, little eventuated.

Thirty years later, and Tairāwhiti has experienced recent multiple disastrous floods – in August 2014, three events in 2017/18, then in November 2021, March 2022, and most recently Cyclone Gabrielle.

The trend is frightening, especially as climate change is bringing more extreme weather events with increasing regularity.

Following Cyclone Gabrielle, multiple scars emerged on steep clear-felled hillsides, with eroded soil creating mountains of silt that headed into the ocean, smothering marine life, just as Quentin described back in 1990.

Forest & Bird has been pushing for decades for these fragile landscapes to be rested or retired. We want to see restoration planting and proper pest control to help the forests recover and bind the soils together.

Anything less than a full commitment to a managed retreat from industrial forestry and hill country farming on unsuitable land is a decision to let the whenua and moana die. It is not a question of whether we as a nation can afford to do this, it’s more the case that we can’t afford not to do it.

My hope is that someone reading this in another 30 years will be able to say that we as a nation lived up to our responsibilities, that the landscapes of Tairāwhiti are more resilient, silt loads in rivers are declining, the moana is recovering, and tāngata whenua are thriving.

☛ For more on the environmental impacts of the recent storms and flooding, and Forest & Bird’s response, see pages 20–23.

EDITORIAL

Ngā manaakitanga Mark Hanger Forest & Bird President Perehitini, Te Reo o te Taiao

“

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 2

Satellite image showing silt flowing into Hawke’s Bay following Cyclone Gabrielle. Koordinates

CELEBRATE CHRISTMAS IN THE SUBS

EXPLORE THE WILDS OF FIORDLAND & THE SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS THIS SUMMER

Discover the wilds of New Zealand’s Subantarctic Auckland, Snares and Campbell Islands, the untamed wilderness of Fiordland’s ice-carved mountains, forests and fiords, and Stewart and Ulva Island on this iconic 12-day Kiwi voyage. Celebrate Christmas in this very special part of remotest New Zealand, observe life at the New Zealand/Hooker’s Sea Lion colony on Enderby Island and wade through waist-deep fields of flowering megaherbs. Share in the magic of the rarely seen albatross ‘gamming’ courting ritual, observe the antics of Snares Crested Penguins navigating the trecherous Penguin Slide and much more.

BEYOND FIORDLAND | 12 Days

20 – 31 December 2023

$12,750pp + KIDS SAVE 70%* Superior Deck 4 Stateroom, twin share

INCLUDES

• Pre cruise hotel night in Queenstown including dinner & breakfast

• All on board accommodation & meals

• House wine & beer with lunch & dinner

• All shore excursions^

• Pre & Post cruise transfers

• Lecture series by noted naturalists

FOREST & BIRD MEMBERS SAVE 5%* PLUS a contribution from your fare is donated to Forest & Bird to support their ongoing conservation work!

Fiordland

The Snares Stewart Island

Auckland Islands

Queenstown Invercargill

Campbell Island

*T&Cs apply, new bookings only, children under the age of 18 years, must travel with a full fare paying adult, excludes F&B discount. ^Excludes optional excursions.

KIDS SAVE 70%

© Luis Davilla

© Chris Todd © Heritage Expeditions

See our website for more Subantarctic adventures! WWW.HERITAGE–EXPEDITIONS.COM Freephone 0800 262 8873 info@heritage-expeditions.com

© Doug Gimesy

*

LETTERS

YOUR FEEDBACK

Forest & Bird welcomes your thoughts on conservation topics. Please email letters up to 200 words, with your name, home address, and phone number, to editor@ forestandbird.org.nz, or by post to the Editor, Forest & Bird magazine, 205 Victoria Street, Wellington 6011, by 1 August 2023. We don’t always have space to publish all letters or use them in full. Opinions expressed on the Letters page are not necessarily those of Forest & Bird.

DEGROWTH MATTERS

Thanks for publishing the Sahra Kress article on degrowth (Autumn 2023). It seems very timely, given the latest updates from the IPCC. Climate breakdown is just one of the planetary boundaries we are breaching, although it is probably the most urgent. Currently, we seem locked into a cycle of public apathy and blame-deflection reinforcing political cowardice and inaction. As well as getting political, each of us should, I think, ask ourselves what we are doing to cut our own GHG [greenhouse gas] footprint? For most of us, a big component is likely to be travel, especially aviation. It’s worth noting that a sustainable annual GHG footprint would be around two tonnes CO2 equivalent per human and one return economy flight AKL–LHR emits about four times that amount. Even domestic car trips across the country have a significant footprint. Saving individual native species is of little consequence if our lifestyle is contributing to Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

Graham Townsend Christchurch

The Degrowth Revolution (Autumn 2023) was a great read and ticks all the boxes – everyone can contribute a bit to degrowth with just some behavioural change. A useful tool for households and small businesses can be the free and easy carbon calculator with a reduction planner at www.carbonneutraltrust.org.nz. Once you know your own CO2 emission footprint, you realise what can be reduced – often quite painlessly and inexpensively. We are an able and responsible team of five million.

Rolf Mueller-Glodde Carbon Neutral Trust NZ

NEW AGENCY NEEDED

Thousands of pest animals infest the North Island’s alpine and native forest communities, wetlands, and dunelands. The animals include several species of deer plus feral pigs, goats, sheep, cattle, and horses. Every year, they devour huge tonnages of our native plants, while

BEST LETTER WINNER

WRITE AND WIN

The best contribution to the Letters page will receive a new edition of The South Island of New Zealand – From the Road by Robin Morrison (Massey University Press, $75). Originally published to much acclaim in 1981, this new reprint coincides with an exhibition of Morrison’s images at the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

their hooves disturb fragile soils on erosion-prone slopes. This destruction is exacerbated by the damage possums, rats, mice, stoats, weasels, ferrets, rabbits, hares, hedgehogs, and feral cats do to native plants, birds, lizards, and invertebrates. Ecosystem destruction by pest animals for over a century in native forests on the North Island’s Raukūmara, Te Ūrewera, Ahimanawa, Kāweka, Kaimanawa, Ruahine, and Tararua ranges contributed to the devastation caused by Cyclone Gabrielle’s huge downpours. The result? Billions of dollars of damage in Te Tairāwhiti and Hawkes Bay. The destruction of landscapes, settlements, farms, horticulture, roads, railways, telecommunications, and coastal areas was catastrophic. Government budgets should fund an agency similar to the former New Zealand Forest Service’s Noxious Animals Division, to employ cullers to shoot alien herbivores and poison and trap smaller pests. This will give the indigenous ecosystems of our axial ranges time to recover, increasing their resilience against future storms of Cyclone Gabrielle’s ferocity, while restoring the forests’ crucial carbon-sequestration function.

Chris Horne Wellington

DON’T KILL THE GOOSE

I refute all that Peter Jackson said, in practical and philosophical terms, but he had every right to air his views (“Funding DOC”, Autumn 2023). Given what has happened with Cyclone Bola and, more recently, Cyclone Gabrielle, we are reaping the consequences of poor land management, not least being unwise native forest clearance. The thoughts that our last few remaining (and still retreating) precious taonga could be exploited for timber (along with tourism) to fund the Department of Conservation’s core function is a complete anathema to me. If he is so keen to still use native trees for timber, I ask him the same question I ask others who propose the same kinds of exploitation: How about growing new native forests for such purposes rather than exploiting existing natural forests? Yes, we

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 4

could benefit from native timber, but not from natural sources, and we need much more research into the silviculture of native species with timber potential. As for tourism, this is a real double-edged sword for our natural areas and so much has been put at risk by the impact of tourism in many of our natural areas. Great care is needed to not kill the [golden] goose.

Martin Nicholls New Plymouth

AUNTIE ACES IT

On receiving the impressive special Centennial issue (Autumn 2023), I was immediately taken by the picture of the kākā on the front cover that looked familiar. The reason was revealed when I checked my copy of the second edition of the Forest & Bird publication New Zealand Forest-Inhabiting Birds that was a gift from an aunt, probably in 1949 or 1950. The same picture is in that book, where it is named the “brown kākā”. The picture appears to be identical except that the cover version seems to be a mirror-image of the other, with the kākā facing to the right rather than the left. The book is certainly a great source of information on the birds. Thank you again for the outstanding issue of the magazine.

Roger Purchas Palmerston North

Editor’s note: Well spotted! The Autumn cover featured Lily Daff’s original artwork, one of 52 commissioned by Forest & Bird to show New Zealanders the beauty of their unique birdlife. The Society’s first colour cover featuring Daff’s “brown kākā” was published in August 1933. Ninety years later, the original painting is still in pristine condition in the Alexander Turnbull Library. This whakapapa provided the inspiration for our 100th birthday issue and art deco cover. You can read more about Daff’s life and impact on page 37.

RADICAL CONNECTIONS

While I found Dr John Flux’s article “Radical Connections” (Autumn 2023) very interesting, I also found it somewhat negative. It’s easy to point out what’s wrong with the way things are or with the efforts being taken by us humans to improve our natural world, but this article had few proposed alternatives and those that were proposed weren’t backed by successful real world examples. The “ecological way to tackle introduced predators” was indicated to be starting with mice and working up to the apex predators and suggested that current approaches being taken are wrong. I would like to see a follow-up article where Dr Flux provides

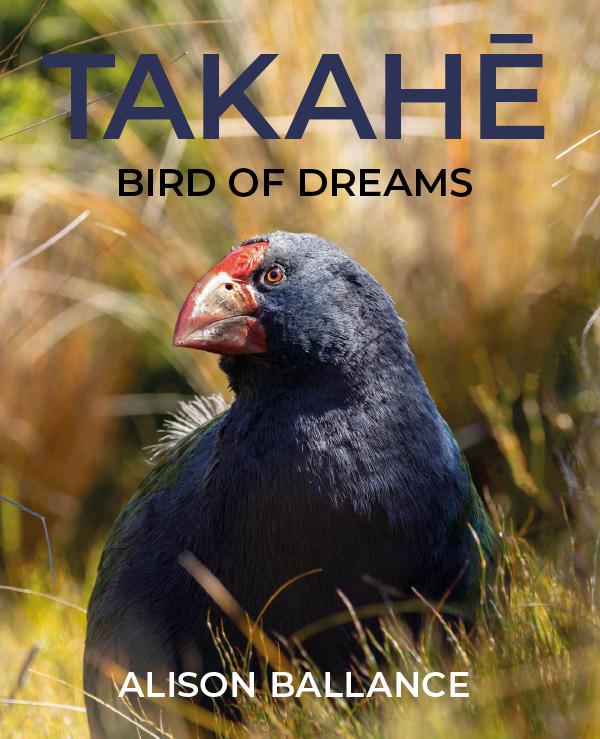

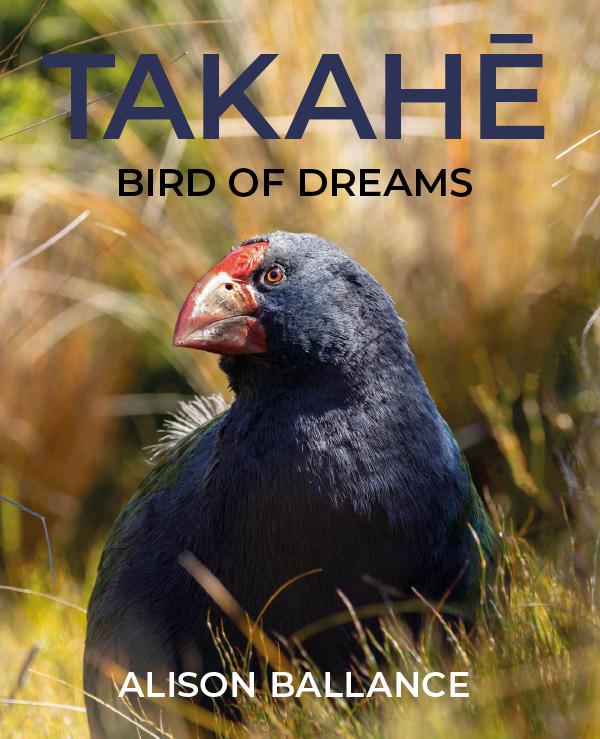

BOOK GIVEAWAY

We are giving away two copies of Takahē Bird of Dreams by Alison Ballance, the inspiring story of the rediscovery and then recovery of the takahē (Potton & Burton, $59.99).

To enter, email your entry to draw@forestandbird.org.nz, put TAKAHĒ in the subject line, and include your name and address in the email. Or write your name and address on the back of an envelope and post to TAKAHĒ draw, Forest & Bird, PO Box 631, Wellington 6140. Entries close 1 August 2023.

The winners of Soundings, diving for stories in the beckoning sea by Kennedy Warne were Ron Vautier, of Hamilton, and Suzanne Hills, of Runanga. The winners of The New Zealand Seashore Guide by Sally Carson and Rod Morris were Nick Wiffen, of Motueka, and Ruth Underwood, of Mount Maunganui.

proposed solutions alongside successful examples of each. This would be a much more constructive, positive, and beneficial article than the rather doom-and-gloom article that was printed.

Jared Oliver Dunedin

John Flux responds: I agree with Jared – I do feel negative. There are no “successful examples”. Take RHD (Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease), discovered in China from a load of rabbits imported from Germany. The Australians brought in RHD for trials, but it escaped (what’s new?), and any ecologist could have told them the result, because all hosts adapt to a virus or any other parasite. Then farmers illegally imported it into New Zealand to kill the rabbits on their land and caused the oscillating rabbit numbers we warned them about. Whenever rabbit numbers fall, predators turn to birds, at random, anywhere, but RHD keeps being spread by disgruntled farmers worldwide. Last year, it arrived in South Africa and is now killing protected rare native rabbits and hares. In Europe, where rabbits and hares are valuable game, they have to be caught and inoculated. In short, I guess my solution is to stop trying to “improve the natural world” and just let it adapt the way it sees fit, but get back to 50% native forest or more. Humanity occupies far too much space.

John Flux Wellington

5 Winter 2023 |

100 YEARS AND COUNTING...

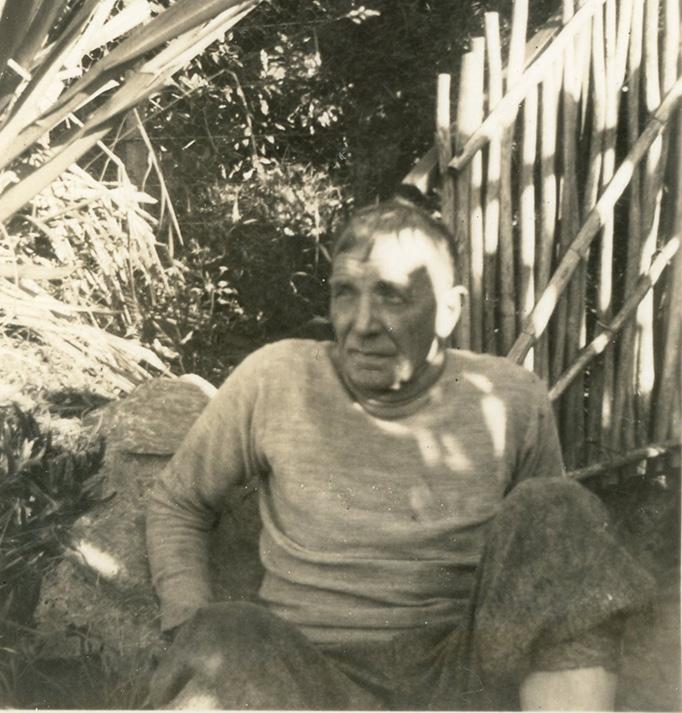

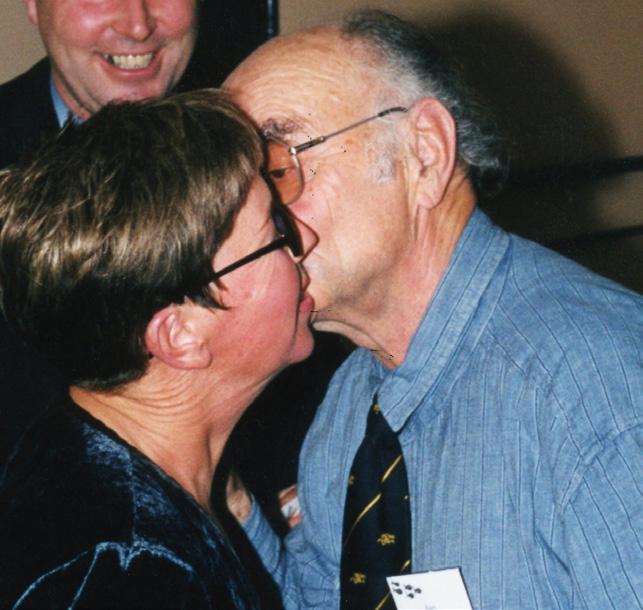

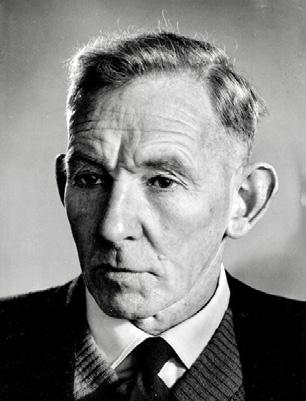

Standing in the dappled light of a leafy canopy, in a small clearing at the heart of the Waikākāriki wetland is the family of Forest & Bird’s founder Captain Ernest “Val” Sanderson. They are accompanied by chief executive Nicola Toki, iwi representatives, Kāpiti Mayor Janet Holborow, and other invited guests.

We are here to watch the unveiling of new signage about Sanderson’s life and legacy in Paekākāriki, a place that inspired his passion for protecting nature. It has been installed along the newly named “Sanderson’s Way” – a gentle tree-lined path that forms part of Te Araroa Trail.

The sign was blessed by Dr Taku Parai, of Ngāti Toa Rangatira, and six tōtara were planted in memory of Sanderson by members of his whānau and invited guests.

The Waikākāriki wetland is a sliver of land that runs between State Highway 59 and the Kāpiti railway line.

Volunteers from local conservation group Ngā Uruoa, led by Paul Callister, have spent

several years painstakingly ripping out invasive weeds, planting native plants, and bringing Waikākāriki back to life. It was Paul who first suggested a permanent tribute to Sanderson here in the recovering wetland.

Sanderson lived and worked in Paekākāriki village while running Forest & Bird for more than 20 years. His house overlooked Kāpiti Island, the inspiration for the establishment of the Society on 28 March 1923.

Ten members of Val Sanderson’s family travelled to Paekākāriki in late April to attend a weekend of celebrations, exhibitions, and children’s activities in memory of Forest & Bird’s founder. Those present included three grandsons Justin Jordan, Giles Jordan, and Guido Panduri, as well as Sanderson’s niece Enid White.

“The name ‘Sanderson’s Way’ has a double meaning to us,” explained Justin. “This small patch of land is a fine example of how anyone – and all of us – can help make a difference. We need to keep growing these small patches by

working together.”

The weekend’s celebrations included an “Inspired by Sanderson” exhibition featuring artefacts that once belonged to him, along with early examples of Forest & Bird’s publicity materials, including posters, magazines, and books. Kāpiti-Mana Branch chair Pene Burton-Bell, who helped organise the weekend’s activities, said Sanderson’s mission to give nature a voice had motivated her and many others to become conservation volunteers.

“Our branch was established in 1974, nearly three decades

NEWS

NATURE

It’s been wonderful to see some of you at our centennial celebrations around the country, including the opening of Sanderson’s Way. Zoë Brown

Justin Jordan and Nicola Toki Bob Zuur

Sanderson’s family at the start of the newly named ‘Sanderson’s Way’. Bob Zuur

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 6

after Sanderson’s death, and has achieved many wins for nature since then,” she said. “I think Captain Val would have been pleased to see what has been achieved so far. It gives me hope for the future.”

Justin generously gifted a collection of Captain Val’s treasured possessions to Forest & Bird, including a perfectly preserved Underwood portable typewriter that his grandfather used to smash out countless letters to government officials.

“Forest & Bird was started by a volunteer who saw our native birds and bush disappearing and decided to do something about it,” said Nicola Toki.

BIG BIRTHDAY BASHES

Three stunning landscapes – Bushy Park Tarapuruhi, Pelorus Bridge Scenic Reserve, near Nelson, and Forest & Bird’s Lenz Reserve, the Catlins, provided the backdrop for Big Birthday Bash parties around the country. More than 600 people from across the motu joined in the March celebrations marking 100 years of Forest & Bird. There was cake aplenty, with creative nature-themed delicacies being whipped up, plus scavenger hunts and conservation activities for the whole whānau. Several branches also organised birthday parties and special events, including Golden Bay, North Canterbury, West Coast, and Manawatū. A huge thank you to the branch members, project volunteers, and staff who helped organise all of these events.

FORCE OF NATURE CONCERTS

Three concerts have been held to date starting with a sold-out performance at Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Arts Festival on 17 March, before heading south to Wānaka and Ōtautahi Christchurch. The Force of Nature concerts showcased the work of eight New Zealand composers, who created modern classical music inspired by Forest & Bird’s whakapapa. The new works were well received by the audience and critics alike. Forest & Bird would like to thank Jenni Murphy-Scanlon, chief executive of the Performing Arts Community Trust, for her hours of work on this music-meets-nature project. Watch this space for future concerts around the motu!

You can experience the music at home by buying a Force of Nature CD. Check out this review here www.fivelines.nz/articles/ forceofnature. The CD is available from Forest & Bird’s online shop at shop.forestandbird.org.nz

CENTENNIAL SPEAKER SERIES

“That same spirit remains at the heart of Forest & Bird today. We continue to campaign for change – to churn out submissions and letters, just using computers instead of typewriters!

“Sanderson and his legacy prove we can make a difference for our wild places and wildlife – especially when we come together.”

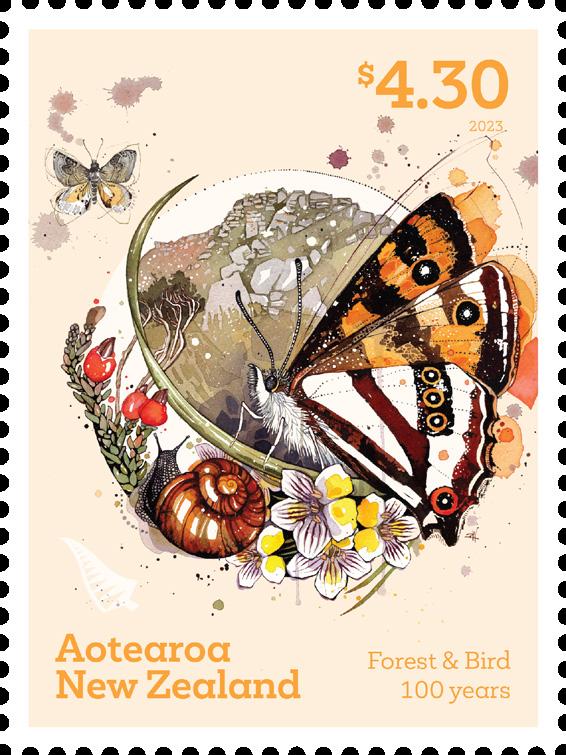

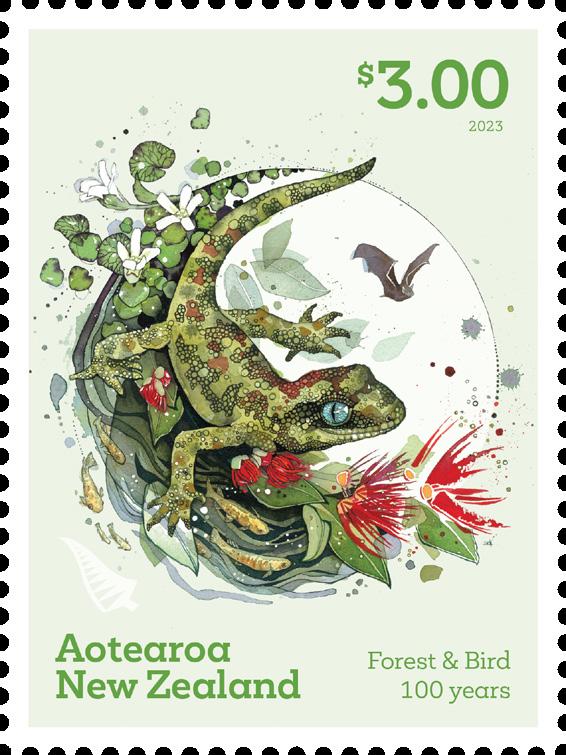

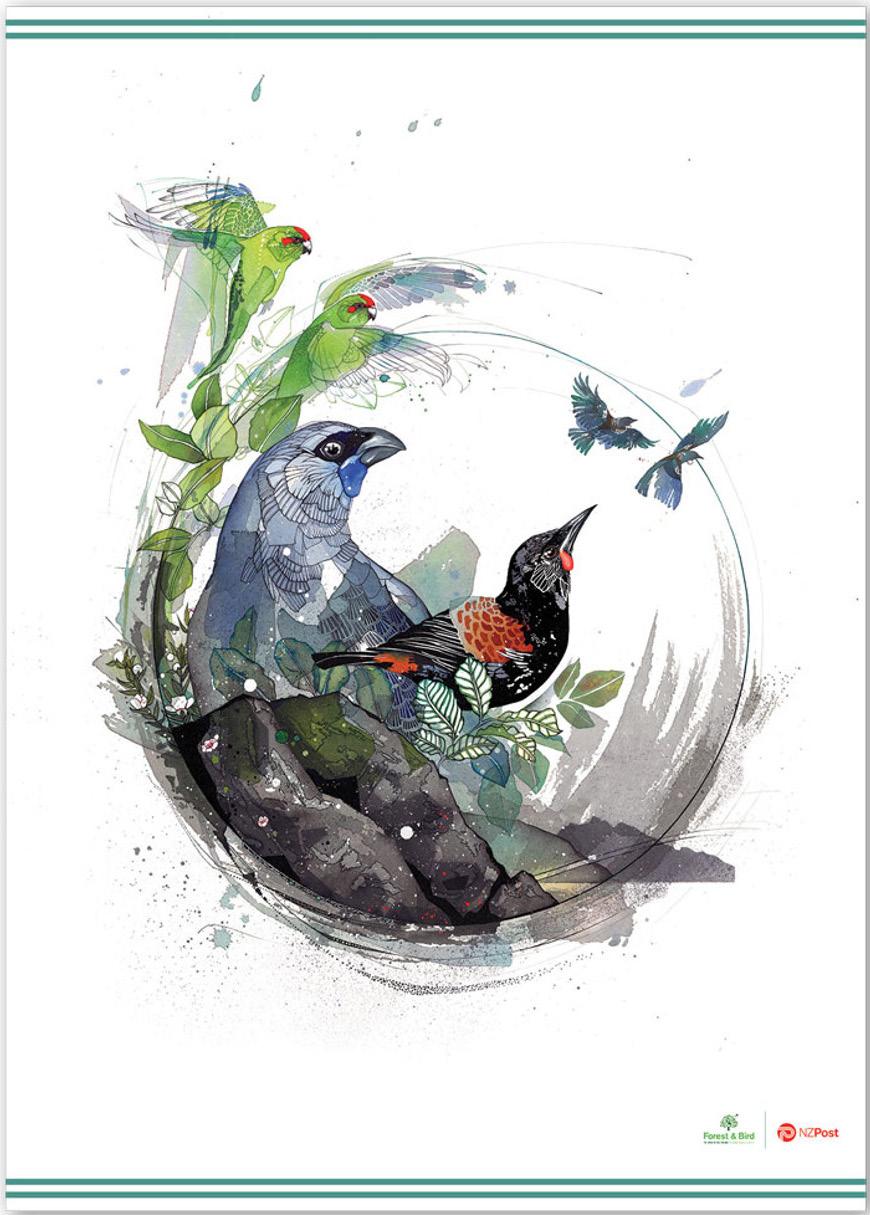

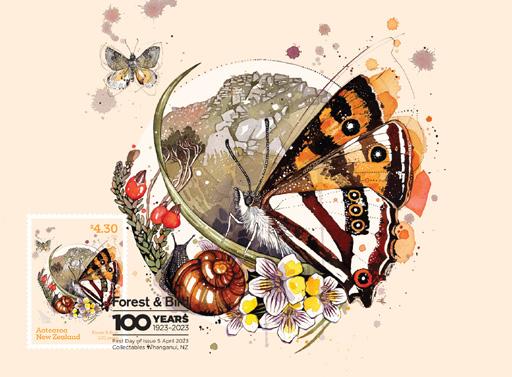

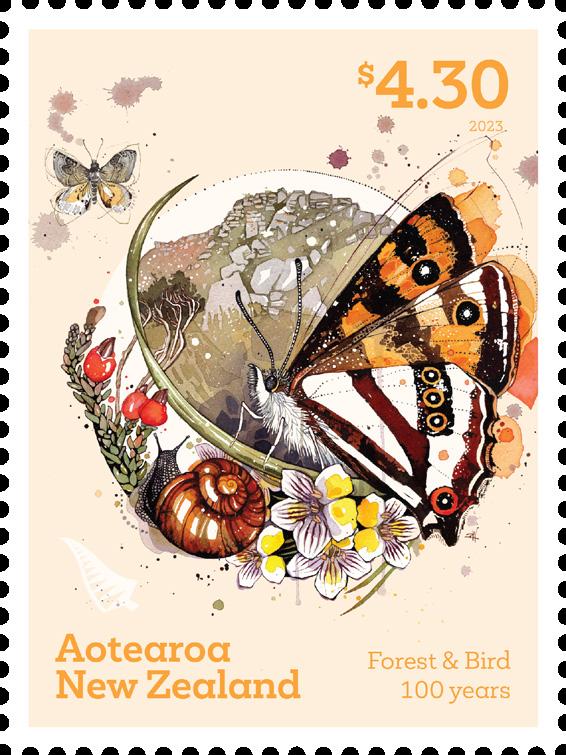

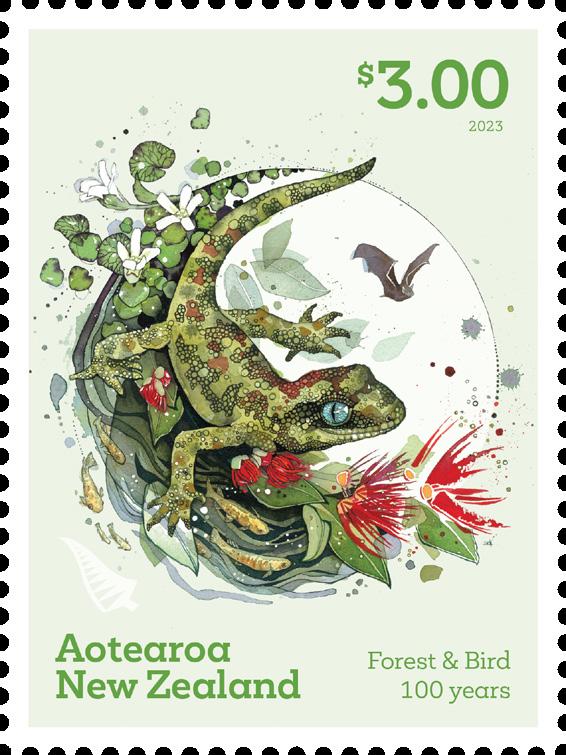

Forests for Human Health and Wellbeing kicked off Forest & Bird’s 12-month centennial speaker series on International Day of Forests in March. The panellists included Dr Geoffrey Handsfield, Senior Research Fellow and Forest Therapy Guide, Rongoā Māori Practitioner Rob McGowan, and Dean BaigentMercer. Forest & Bird is encouraging everyone to plant native trees this winter. Keep an eye out for commemorative planting events coming soon. The second speaker series focused on Forest & Bird’s new stamps – see page 42.

Find out more about Forest & Bird’s Centennial Celebrations programme at www.forestandbird.org.nz/natures-voice-100-years-and-counting. See pages 34, 42, and 54 for more centennial-related events.

Force of Nature concert, Auckland Arts Festival Andi Crown.

Esther Williams and Matai Moore, Bushy Park Tarapuruhi.

Sanderson in his Paekākāriki garden, circa 1930s.

Force of Nature concert, Auckland Arts Festival Andi Crown.

Esther Williams and Matai Moore, Bushy Park Tarapuruhi.

Sanderson in his Paekākāriki garden, circa 1930s.

7 Winter 2023 |

Sanderson’s Underwood portable typewriter.

After a hiatus of three years, Forest & Bird’s annual conference is back! Join us at Te Papa, Wellington, to celebrate a century of conservation mahi, discuss current environmental challenges and solutions, and look ahead to the next 100 years.

The theme is bold leadership in a time of crisis, and Forest & Bird’s chief executive Nicola Toki will deliver a State of the Nation address explaining why looking after the environment matters more than ever in our fastchanging world.

A series of thought-provoking sessions will follow with an exciting line up of guest speakers, including a keynote address from Simon Upton, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. The MC for the day will be Jesse Mulligan, of RNZ and Discovery’s The Project.

Gisborne Mayor Rehette Stoltz will join Federated Farmers President Terry Copeland and Air New Zealand’s Chief Sustainability Officer Kiri Hannifin in a panel discussion about business and community responses to the climate and biodiversity crises.

The conference will also provide an opportunity to explore the future of conservation – drawing on expertise from iwi leaders and academics, including Dr Amanda Black, co-director at Bio-Protection Aotearoa Research Centre, and Mananui Ramsden, chairperson of Te Rūnaka o Koukourata, Banks Peninsula. They will challenge the audience to think outside the box.

There will be a panel discussion of leading political and environmental journalists, who will discuss crisis communication and what it will take for politicians and business leaders to act on environmental issues and climate apathy. This session includes Eloise Gibson, climate change editor at Stuff NZ, Dale Husband (Ngāti Maru), of Waatea News, TV3’s Isobel Ewing, and Marc Daalder from Newsroom.

This session will be followed by a rangatahi panel of

CENTENNIAL CONFERENCE

SATURDAY 29 JULY 2023

TE PAPA, WELLINGTON

inspiring young Kiwi environmental leaders, who will provide perspectives from a generation that will live with the consequences of the choices we are making today. Professor Jacinta Ruru, Māori Law Professor and legal scholar, will join Nicola Toki to wrap up the day with a session about shifting our mindset and looking forward to the future.

In the evening, we will be celebrating Forest & Bird’s first 100 years at this year’s Sanderson dinner and conservation awards ceremony, where we will be honoured to hear from historian, author, and environmentalist Dame Anne Salmond.

You can see the full Centennial Conference programme and register at www.forestandbird.org. nz/conference-registration

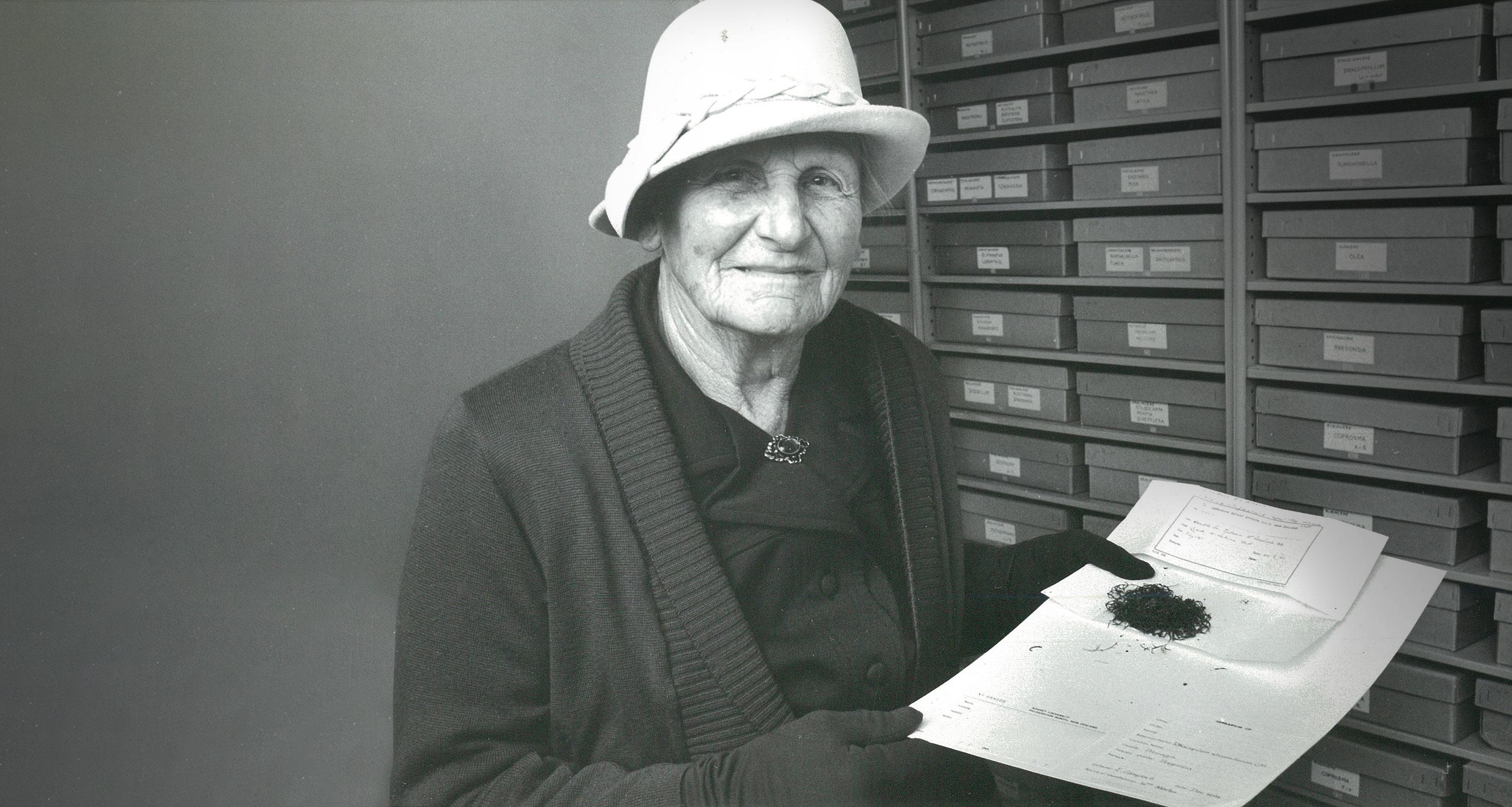

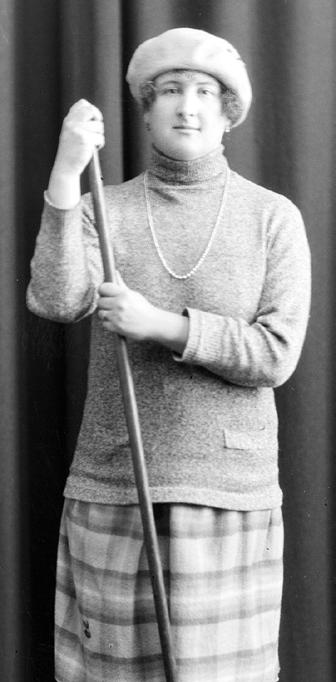

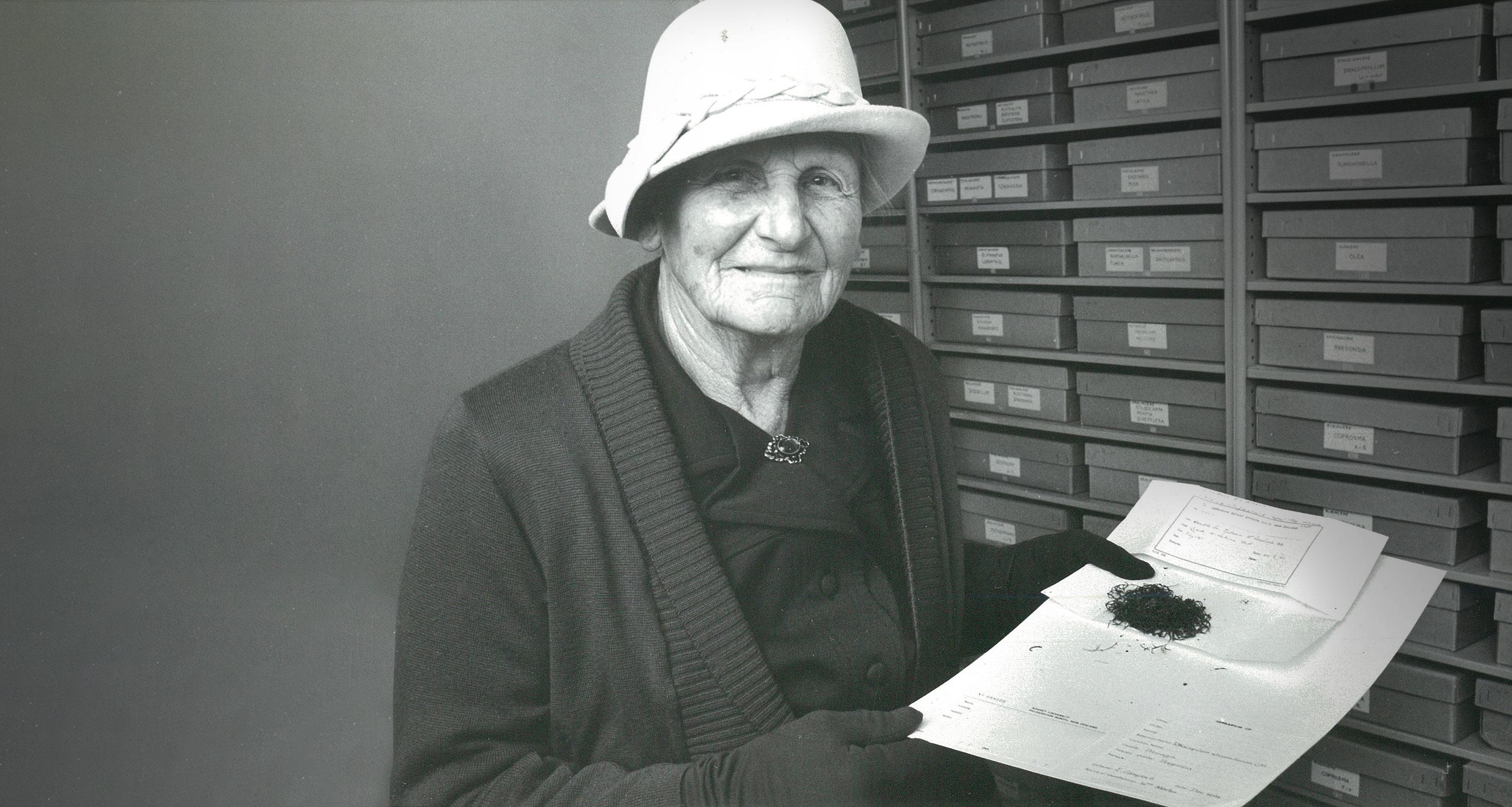

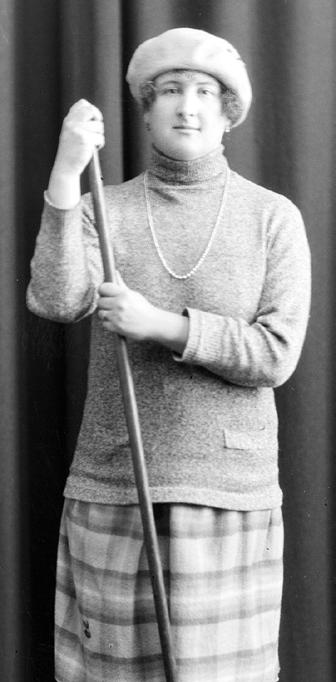

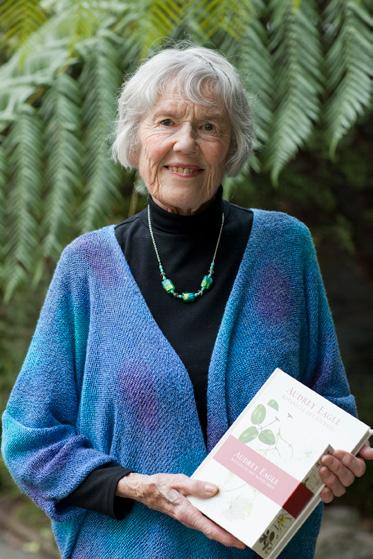

100 NATURE HEROES

We are looking forward to launching Forest & Bird’s Conservation Heroes tribute during National Volunteer Week (18–24 June 2023). Do you know someone who is a conservation hero for nature who deserves some recognition? You don’t need to be a Forest & Bird member to nominate a hero or be nominated. Nominees will receive a certificate in recognition of their work to protect te taiao. Nominations will be open until February 2024. Please keep an eye on your inbox and social media or check our website for more information. In the meantime, check out page 34 for six women heroes in Forest & Bird’s history.

NATURE NEWS

Juvenile kea, Arthur’s Pass. Daniel Dirks

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 8

NEW CLIMATE CAMPAIGN

Forest & Bird, together with our allies Oxfam Aotearoa and Greenpeace Aotearoa, is set to launch Climate Shift: A 10-point plan for action.

During 2023, we have experienced several “1 in 100 year” weather events, including Cyclone Gabrielle’s flooding, erosion, and landslides in the north and severe droughts in the south.

Communities across Aotearoa New Zealand are aready feeling the devastating consequences of successive governments’ inaction.

Our new Climate Shift campaign calls on government ministers, MPs, and political parties to step up a gear and urgently address the climate crisis. Forest & Bird, Greenpeace, and Oxfam have put together 10 key climate actions that, if implemented, would restore nature, cut emissions, and protect frontline communities.

“This year’s extreme weather events underscore the urgency of addressing this crisis head on,” says Nicola Toki, Forest & Bird’s chief executive.

“With October’s general election coming up fast, we want to hear how political parties intend to rebuild and stop future climate disasters from happening in our country.

“I suggest they start by looking at the 10 key policies developed for the Climate Shift campaign and make sure they put nature, and proper funding, at the heart of their responses.”

The Climate Shift campaign will soon be visible across Aotearoa, with public meetings, posters, billboards, hoardings, election debates, and more planned.

“Together, let’s demand urgent climate action from ourpoliticians ,” says Forest & Bird’s Climate Shift campaign lead George Hobson. “Please help us make 2023 a turning point for climate action in Aotearoa.”

Find out more about Climate Shift’s 10-point plan and how you can help spread the word at www.forestandbird.org.nz/climateshift

TIME TO STOP TRAWLING

Hundreds of people and a flotilla of crafts turned out to oppose bottom trawling in the Hauraki Gulf, in an protest organised by Forest & Bird and Greenpeace Aotearaoa.

The Show Your Heart For The Hauraki event in April attracted more than 60 vessels, including yachts, kayaks, and paddleboards, who surrounded a huge banner calling for an end to the fishing practice.

Bottom trawling is a fishing method that involves dragging large weighted nets across the seafloor, bulldozing ocean life and indiscrimately destroying precious ecosystems.

“Tīkapa Moana is a biodiversity hotspot, it is a taonga, and we must do everything we can to revitalise the mauri and life-sustaining capacity of the Gulf,” said Bianca Ranson, Forest & Bird’s Hauraki Gulf coordinator.

“Everything is connected in an ecosystem, and it is deeply disappointing bottom trawling is still being allowed.

“The government is considering decisions that will determine whether the Gulf thrives or declines further into ecological collapse.

NATURE NEWS

Jo Dighton rescues a pet chicken from floodwaters caused by Cyclone Gabrielle in Hawke’s Bay. Steve Dighton

Greenpeace | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 10

“We’re here to tell Ministers to listen to the tens of thousands of people that want protection and not be influenced by commercial fishing industry lobbyists.”

The event, which took place off Mission Bay, Auckland, is part of our Love the Gulf campaign to protect and restore Tīkapa Moana from manmade ecological threats, including overfishing, sedimentation, and climate change.

People turned up because they wanted to see a thriving vibrant Tīkapa Moana, said Ellie Hooper, Greenpeace’s oceans campaigner.

“Trawling has no place in this precious marine park, and the public mandate for change is clear – more than 84% of people surveyed want trawling gone from the Gulf.”

☛ Dolphins, gannets, and sharks: see page 58 for more on the marine treasures of the Hauraki Gulf.

MINING THREATENS KAURI AND WATER

Concerned Whangaroa hapū members and Forest & Bird representatives gathered at two locations in Northland during April to speak out against the threat of mineral mining.

Manginangina Scenic Reserve, Puketī Forest, is among the last 1% of unlogged ancient kauri forest in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The area is included in a prospecting permit for lithium and rare earth elements the government granted last year to Mineralogy International Limited, owned by controversial Australian mining billionaire Clive Palmer.

Whakarara Conservation Area, behind beautiful Te Ngaere Bay and above the water source of local Ngāi Tupango hapū, is included in a different prospecting licence held by the same company.

The prospecting permits cover private land, Māori land, and public conservation land that is under Treaty claim.

“In this area, we have underground streams all through our maunga and whenua,” said Robyn Tauroa, of Whangaroa Papa Hapū.

“We would not want toxic mining waste here, in an area famous for flooding, that could lead to the pollution of waterways out to Whangaroa Harbour and the sea.”

More than 150,000ha of exploration and prospecting permits have been granted on public conservation land since 2017, when the government promised to end new mines.

Forest & Bird has been calling on the government to fulfil its 2017 promise, helping the public write to MPs in support of a Bill to end new mines on conservation land, and holding protest banner events around Aotearoa.

“We need the government to hurry up and fulfil their promise. Local communities shouldn’t have to fight to stop mining destroying the ancient forests, wetlands, and rivers we thought were already protected,” said Forest & Bird’s Dean Baigent-Mercer, who attended the Northland protests.

Protest at Manginangina Scenic Reserve, Puketī Forest, Northland. Forest & Bird/George Hobson

11 Winter 2023 |

Forest & Bird’s Hauraki Gulf coordinator Bianca Ransom.

TE KUHA WIN!

This is one of those cases where Forest & Bird can make a difference,” said the Society’s legal counsel Peter Anderson. “Without us, a coal mine would likely be consented by now.”

In April, the Environment Court ruled that resource consents should not be granted for an opencast coal mine on the Te Kuha escarpment, overlooking Westport.

It’s a big win for the climate and threatened species, especially New Zealand’s rarest butterfly –the proposed mine site is home to the largest known forest ringlet population nationwide.

Since 2017, Forest & Bird has been battling on three legal fronts to stop the mine, with our lawyers winning cases in the Environment Court, High Court, Court of Appeal, and Supreme Court.

Stevenson Mining Limited is running out of legal options, but it has rolled the dice one more time – by appealing the latest Environment Court decision.

The vast majority of the 144ha mine footprint is covered in indigenous forest and shrubland with 500-year-old pink pine, mountain beech, pahautea, and

yellow-silver pine. It is particularly rich in moss and liverwort species.

It is located on a local purpose reserve, administered under the Reserves Act by the Buller District Council for water conservation purposes. About 12ha is conservation land administered by the Department of Conservation.

The proposed site occupies the crest of a ridge at a point where the Buller coal measures overlap with the Paparoa coal measures, the only place in the country where the two occur together.

It has a distinctive low-growing “coal measures vegetation” because of its altitude and the acidic nature of its soils. This area has no roads and has been subject to very little human activity, thus

it possesses very high naturalness and visual amenity.

It is home to a number of threatened plants and animals, including roroa great-spotted kiwi, mātātā South Island fernbird, New Zealand pipit, native geckos, and an undescribed leaf-veined slug, which is potentially locally endemic.

“The ruling shows environmental bottom lines are so important –you can’t offset or compensate your way out of destroying unique landscapes, plants, or animals,” said Forest & Bird’s chief executive Nicola Toki.

Te Kuha Partnership (made up of the Stevenson Group and Wi Pere Holdings) is the owner of Rangitira Developments, which holds the mining permit over the Te Kuha prospect. It has appointed Stevenson Mining as the project coordinator and mine operator.

The company needed three sets of permissions: resource consents, permission to mine public conservation land administered by DOC, and permission to mine the public reserve administered by Buller District Council.

Over the past six years, it has lost in all three areas, with April’s

NATURE NEWS

“

Thanks to thousands of you, our legal team has clocked up (another) win for Te Kuha, the latest in a six-year campaign to save it from being mined.

Te Kuha escarpment with untouched forest below. Neil Silverwood

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 12

Distinctive low-growing vegetation is a feature of Te Kuha. Neil Silverwood

win coming just after Forest & Bird marked its 100th birthday.

One donor reacted joyfully to the news, saying: “I couldn’t be a lawyer, but I’m so proud to be a paid-up member of Forest & Bird so I can support this sort of legal action, which is so necessary.

“So few groups have the strength of resources to carry this sort of action through to a Supreme Court conclusion, but Forest & Bird has this collective power. Thanks for your determination, uncompromised kaupapa, and follow through.”

Crucial policies that helped the courts form decisions on the case included the West Coast Regional Policy Statement and the National Policy Statement for Freshwater.

Forest & Bird staff have put in many hours of time and effort advocating for stronger rules to be put into both policy statements. This

work paid off with the Te Kuha case and will help defend nature against climate change in the future.

“This coal mining company has seen legal failure after legal failure. It lost in the Supreme Court, and it doesn’t have any land access. It’s time to withdraw this climate-and biodiversity-damaging proposal once and for all,” added Nicola Toki.

“Charities like ours shouldn’t have to spend years in court battling coal mining companies. For a safe climate, we urgently need to stop all new and expanded coal mines.”

GLENBROOK GAIN

The government has finally taken a meaningful step towards reducing Aotearoa New Zealand’s unsustainably high carbon emissions. In May, the Prime Minister announced a deal with New Zealand Steel and Contact Energy to subsidise a new “electric arc” boiler for NZ Steel’s Glenbrook Plant. This will reduce 800,000 tonnes of climate pollution each year – one percent of the country’s total annual emissions. We’d now like to see Labour follow through on

D i s c o v e r t h e u n i q u e b i r d s a n d p l a n t s t h a t c a l l t h e C h a t h a m

D i s c o v e r t h e u n i q u e b i r d s a n d p l a n t s t h a t c a l l t h e C h a t h a m

I s l a n d s h o m e o n t h e m o s t c o m p r e h e n s i v e g u i d e d e x p l o r a t i o n o f

I s l a n d s h o m e o n t h e m o s t c o m p r e h e n s i v e g u i d e d e x p l o r a t i o n o f t h e s e r e m o t e i s l a n d s w i t h o r n i t h o l o g i s t t h e s e r e m o t e i s l a n d s w i t h o r n i t h o l o g i s t M i k e B e l l . M i k e B e l l .

9 to 16

8 - d a y g u i d e d t o u r w i t h o r n i t h o l o g i s t a n d

c o n s e r v a t i o n i s t M i k e B e l l c o n s e r v a t i o n i s t M i k e B e l l

i t h o l o g i s t a n d

Jan 2024 check out our website for additional tour dates!

D i s c o v e r u n i q u e p e o p l e , h i s t o r y , c u l t u r e ,

D i s c o e r u n i q u e p e o p l e , h i s t o r y , c u l t u r e ,

g e o l o g y , f l o r a a n d f a u n a g e o l o g y , f l o r a n d f a u n

V i s i t P i t t I s l a n d n a t u r e r e s e r v e s

V i s i t P i t t I s l a n d n a t u r e r e s e r v e s

E x p l o r e o u t e r i s l a n d s , i n c l u d i n g S E I s l a n d a n d

E x p l o r e o u t e r i s l a n d s , i n c l u d i n g S E I s l a n d a n d

M a n g e r e f r o m t h e w a t e r

M a n g e r e f r o m t h e w a t e r

L e a r n a b o u t t h e C h a t h a m I s l a n d T a i k o T r u s t

L e a r n a b o u t t h e C h a t h a m I s l a n d T a i k o T r u s t

P r i c e f r o m $ 7 , 1 7 5 p p * . P r i c e f r o m $ 7 , 1 7 5 p p *

*The current price per person twin share in NZD. Includes return air travel on Air Chathams, seven nights' accommodation, all meals including continental breakfast/picnic lunches/buffet dinners, all sightseeing and entry fees as per itinerary. Refer to website for full price inclusions & single traveller pricing. Wild Earth Travel has regular Chatham Islands tours throughout the summer season - dates, prices and itineraries will vary.

H i g h l i g h t s : H i g h l i g h t s : 8 - d a y g u i d e d t o u r w i t h o r n

Backyard

BIRD FEEDING

We look at some environmental friendly ways to attract native birds to your garden while avoiding bad practices that could harm their health.

Dr Daria Erastova

Backyard bird feeding is an enjoyable hobby that many Kiwis enjoy. Previous studies have found around half of New Zealand households provide food for garden birds in their neighbourhood.

This pastime attracts birds that people can observe up close, increasing our quality of life, especially in urban areas. If done correctly, it can also provide a valuable supplementary food source for our native species, especially during winter when natural foods are scarce.

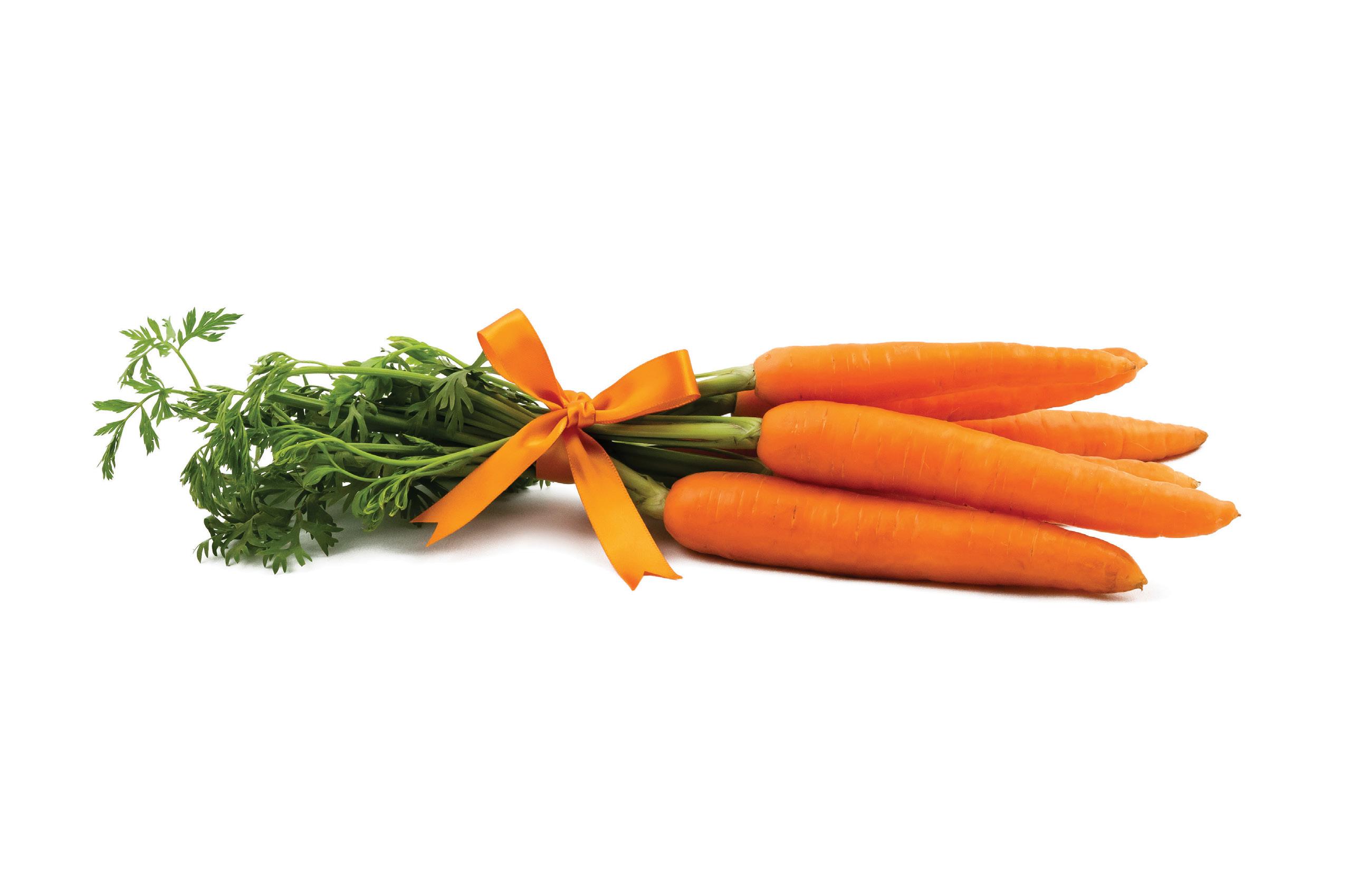

But it’s important to choose the right food and feeder type for the particular species we want to attract rather than copy practices in other countries, such as the UK, that could be detrimental for Aotearoa New Zealand’s already threatened native species.

New Zealand studies show bread and seed are the most commonly offered food in our cities.

Unfortunately, such practice is harmful because it attracts introduced grain-eating species, such as starlings, doves, and mynas, that outnumber native species.

On top of that, some grain-eating species – for example, house sparrows – can carry dangerous diseases such as salmonellosis that they can pass onto other birds, or even humans, through soiling the feeding equipment or the area around them.

Native garden birds have specific dietary

requirements to stay healthy and thrive – but none of them are grain eating. Some eat invertebrates (riroriro grey warbler, pīwakawaka fantail), flower nectar (korimako bellbird, tūī), fruit (tauhou silvereye, kākā), or tree leaves (kererū).

So offering these types of food can support taonga species and bring them into our lives. But how safe is it to offer such foods to native birds?

SUGAR WATER: In a recent research study, my colleagues and I looked at how backyard sugar-water feeding, which is an achievable alternative to flower nectar, affected tūī, korimako, and tauhou.

We found birds that visited feeders with high sugar concentrations (1 cup per litre or more) in winter had better body conditions. In addition, we sampled the feeders and the visiting birds for nasty pathogens such as salmonella, and they all returned negative.

Compared to bread and seed feeding, sugar water seems to be relatively safe for native birds and humans as long as the following rules are followed.

n Always use one of the commercially available Tui Nectar Feeder™, Topflite Nectar Nutra feeder™, or PekaPeka™ bird feeders. That will stop unwanted birds from soiling sugar water.

n Regularly clean your feeding stations to reduce pathogen growth.

COVER

GARDEN SPECIAL REPORT BIRDS | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 14

Korimako bellbirds hogging a PekaPeka feeder from tauhou silvereye. Oscar Thomas

FRUIT: It is a good idea to offer fruit halves for fruiteating birds such as tauhou and kākā. However, people should wash fruit before offering it to remove wax and other added chemicals that make fruit look appealing. Do not offer rotten fruit, as the mould and bacteria growing on them can be harmful to birds.

INSECTS: For birds that eat insects and spiders, a freshly hard-boiled egg can serve as a great alternative protein source. Even better, build a bug hotel and plant native trees to encourage all sorts of creatures into your garden. This can provide a great food source for visiting birds.

WATER: Another important aspect of attracting birds to urban gardens is providing water for them to drink and bathe in, especially during hot and dry months. A bird bath can be as simple as a shallow dish, but it is crucial to keep the water level very shallow (4–5cm) because there is a serious risk of drowning for small native birds. It is important to change the water in your bird bath regularly to prevent the growth of algae and bacteria.

WHAT NOT TO FEED: There are definitely foods we do not recommend for backyard bird feeding. As mentioned earlier, bread and seed feeding is associated with a risk of pathogen transmission between birds and humans, and discourages native birds. Food scraps and leftovers can attract mice, rats, hedgehogs, and possums. Cheese contains too much salt and

microorganisms, and it can be harmful to birds’ health. Make sure the offered food is fresh and free from dirt and mould.

TIPS FOR SUCCESS: The most important thing is to offer sugar water in a concealed container and pin it to the top of a tall pole. This will keep the rats and other pests away and protects food from soil bacteria contamination.

Install bird feeders for fruit and eggs on tall poles too. A separately standing pole away from trees and fences will discourage bird predators from climbing it and gives birds an unobstructed view of potential hazards.

Keep your bird feeder clean and well maintained. A dirty feeder can become a breeding ground for bacteria and disease, which can harm birds and humans. We recommend cleaning feeding stations twice a week with hot water and scrubbing. Avoid using bleach or other chemicals that may harm birds.

In addition to providing food and water, you can also create a bird-friendly habitat in your backyard. This can include planting indigenous trees and shrubs that provide natural foods, shelter, and nesting sites for birds, as well as leaving areas of your lawn unmowed to provide habitat for invertebrates. Finally, carrying out backyard pest control is an easy way to make a difference for native birds that struggle because of introduced predators.

In conclusion, providing birds with supplementary food, especially in winter, is an affordable and appealing way to interact with local wildlife. But this alone will not boost your local bird population. The long-term answer is to transform our backyards and city parks into bird-friendly habitats (see page 18 for more tips on how to do this).

☛ Our special report on garden birds continues overleaf

Dr Daria Erastova works for Forest & Bird as Te Hoiere Bat Recovery Project Manager. She was the main author of a recent study, the first of its kind in New Zealand, to determine how sugar-water feeding affects backyard bird communities.

A leaf-eating kererū. Heidi Benson

Bathtime for one happy pīwakawaka fantail. John Nelson

A leaf-eating kererū. Heidi Benson

Bathtime for one happy pīwakawaka fantail. John Nelson

15 Winter 2023 |

Our kākā are partial to fruit. Glenn Turner

KEEPING WILD BIRDS “WILD”

Recently, there have been a number of comments on birding Facebook groups about keeping wild birds as “pets”. People have suggested young tūī can be kept and trained to talk, people have said they keep tauhou silvereye in cages, and there has been talk of native owls being kept as pets.

There have also been pictures of people feeding wild birds from the hand and handling them. Many people may not realise that doing these things is either illegal and/or not recommended for the health of the bird.

You cannot keep native and endemic birds captive on your property unless you are a licensed bird rehabilitator or kākāriki breeder. There are good reasons for this. We don’t want a market in caged birds, and they also have special dietary requirements if they are to recover and thrive.

If you find an injured native or endemic bird, take it to a licensed bird rehabilitator or vet. Aside from rescuing it, do not try to take care of it yourself or keep it as a pet – it is illegal to do so.

As explained on page 14, many birds have special dietary requirements that people do not know about or get completely wrong. I’ve recently seen people giving advice that is going to harm a bird, such as feeding honey to tūī and tauhou.

Feeding captive birds the wrong foods can result in permanent bone and feather deformities that lead to a quick death.

Last year, people were posting pictures of dead or sick birds in their garden on social media. One showed two tauhou silvereyes dead under an olive tree. They appeared uninjured, although they had fluffed up feathers. The photographer asked why this may have happened.

Fluffed up feathers are a common feature of birds with salmonella and diseases such as chlamydia. Feeding these birds the wrong foods, combined with poor hygiene, likely killed these birds.

Bread is absolute junk food for birds. It’s full of carbohydrates, yeast, and sugars and should never be fed to them.

Encouraging birds to feed from your hand is also a very poor practice. It leads to birds associating people with food, losing their fear of people and quickly becoming cat food!

It may be satisfying for us humans to feed birds by hand, but ultimately it’s not good for them. Please refrain from keeping or treating wild birds as pets. Let’s keep them wild, healthy, and alive.

Ian McLean is the Auckland Regional Representative for Birds New Zealand.

Feed tūī, bellbird, hihi, kākā, silvereye & more

● Cat proof! 360 degrees of visibilty while birds feed

● Provides sugar water, fruit & energy truffles

● Feeder can go anywhere, it’s on a waratah

● Stainless steel nozzle ensures safe, hygienic feeding & easy cleaning to prevent the spread of avian pox.

Buy a feeder at PFNZ shop.predatorfreenz.org

For more info go to our website pekapekabirdfeeders.nz

Licensed bird rehabilitator Sabrina Luecht, of Kaikōura Wildlife Centre Trust, with injured ruru.

It is illegal to keep a wild bird as a pet, even if you have nursed an injured avian back to health, as Ian McLean explains.

COVER GARDEN SPECIAL REPORT

BIRDS

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 16

READY SET COUNT!

It’s time to get out the binoculars and bird books. This is your opportunity to brush up on your avian identification skills before the 17th annual New Zealand Garden Bird Survey begins.

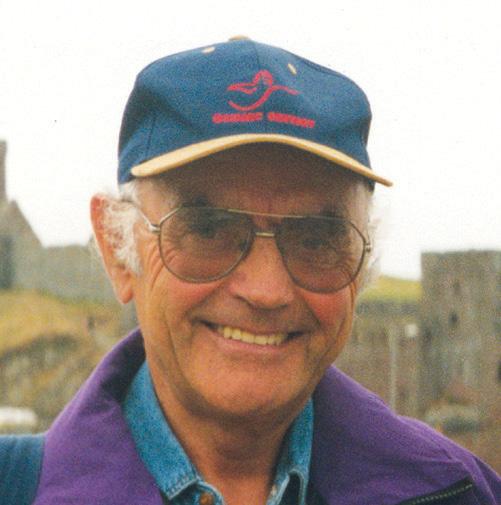

TV producer Ian McGee, who hails from Dunedin, is one of thousands of New Zealanders planning to gather on decks, near windows, and under trees in gardens, parks, and school grounds across the country to count all the birds they can see and hear for one hour, on one day in the last week of June.

Ian started doing the survey in 2007 and says it’s become quite addictive.

“We get the regular flocks of silvereyes, but occasionally a rosella has turned up, which is always exciting,” he said.

“Once you’ve done the survey, you start noticing birds for weeks afterwards. It’s an entry step that really opens your eyes to a whole new world.”

If you are thinking of doing the survey but haven’t quite reached out for the tally sheet that is included with your June Forest & Bird magazine, Ian says don’t hold back, go for it.

“Grab a pair of binoculars and just sit and watch. You can look in the eyes of these birds and it’s not hard to imagine scales on them and travelling back in time 60 million years. You’re watching their dinosaur ancestors.”

More than 5400 new surveys were added from last year’s analysis to bring the total completed over the past 10 years to 44,357.

The information is analysed using supercomputers

to crunch all the data. Scientists can see whether birds were fed in the garden they were recorded in – and whether they are located in a rural or urban setting. The data also shows how many gardens have been surveyed in each region of the country.

The most recent analysis of the 2022 data showed positive signals emerging for four native species:

n A moderate increase over 10 years of kererū and pīwakawaka fantail counts.

n A continued shallow increase in tūī counts in the long and short-term, especially in Canterbury, Taranaki, and the West Coast.

n Little or no change in tauhou silvereye counts over the past five years, although overall they are still in a long-term shallow decline.

However, things are not looking so good for some introduced species. Numbers for tāringi starlings and pahirini chaffinch show a population decline for both species.

The trend of little or no change in myna counts continues nationally, except in Wellington, ManawatūWhanganui, and Taranaki where counts show an increase in bird numbers over both 10- and five-year periods.

Manaaki Whenua researcher Dr Angela Brandt says the data let us understand how bird populations are changing across Aotearoa New Zealand.

“What’s exciting about having so many years of surveys now is we can see how trends are changing over time,” she said. “The results give us an early warning if a species starts to decline.”

This year’s New Zealand Garden Bird Survey runs between 24 June and 2 July, and scientists need your help to find out how our feathered friends are doing. Kim Triegaardt

Ian McGee, of Dunedin, has completed 15 Garden Bird Surveys and is looking forward to this year’s event Sam McGee

→ 17 Winter 2023 |

Tauhou silvereye. Manaaki Whenua/Rob Osborne

Since 2021, Manaaki Whenua has also asked survey participants what more needs to be done to care for birds in New Zealand. Last year, there was overwhelming response for more to be done to manage predators and weeds.

Manaaki Whenua social researcher Dr Gradon Diprose says participants suggested a wide range of everyday actions people can take to reduce the impacts of weeds and predators on birds.

Not all participants agree on what should be done, but the responses highlight how many New Zealanders care both about birds and the wider environment.

And as Dunedin birder Ian McGee points out, you don’t have to go far to take notice.

“One of the things I worry about is that because kids are watching wildlife television programmes, they start to think that nature only happens in places like the Serengeti and other exotic places.

“But really all you need to do is stick your nose out of your window at home and sit and watch the birds come to you.”

The New Zealand Garden Bird survey runs from 24 June to 2 July 2023. You can find an easyto-use bird identification section at www.gardenbirdsurvey.nz, plus lots of other useful information. You can also submit your bird counts online instead of using a paper tally.

Kim Triegaardt is Senior Communications Advisor at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research.

MAKE YOUR GARDEN BIRD FRIENDLY

If you want to keep wild birds flourishing in your garden, controlling introduced mammals is a must.

Stoats, rats, possums, and hedgehogs are common predators that kill and maim birds, eggs, and chicks in our backyards, in the city as well as rural areas.

Trapping is a simple measure you can do at home to make a difference. Predator Free New Zealand has a handy guide to choosing the right trap on its website – go to Bit.ly/3mLlRQ5

If you have a cat that goes outside, you can make it more bird friendly by fitting a bell on its collar, feeding it at regular times, and keeping it inside at night.

Bird feeding stations should

be over 1.7m high or hung from a sturdy branch to keep them out of the way of predators and pets. Why not try some of these measures and see what difference it makes to the birds visiting your garden? Maybe you can help bring back the dawn chorus to your neighbourhood.

For more tips on how to make your garden bird friendly, go to gardenbirdsurvey.nz/gardenfor-birds/

In your garden, school or local park Notice and connect with birds and nature Plant native species for fruit, foliage, and nectar Manage weeds and predators Provide supplementary feeding with care Get involved with community initiatives Add water Create

bird-friendly haven gardenbirdsurvey.nz Provide water Supported by:

a

Tūī. Manaaki Whenua/Mike Wilson

Dr Angela Brandt

Dr Gradon Diprose

COVER → | Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 18

FOR THE OF BIRDSLove

Forest & Bird has been battling for a better deal for native birds for the past 100 years. Here are some ways you can help us bring back a dawn chorus to every corner of Aotearoa New Zealand, including in your garden.

➊ Volunteer: Forest & Bird has more than 120 projects all over the country where conservation volunteers are working hard to reducing pest numbers in their neighbourhood. This mahi is helping return native birds, bats, lizards, and insects to areas where they once thrived. Volunteers are always welcome! You can find your local branch at www.forestandbird. org.nz.

➋ Donate a predator trap: Visit Give a Trap, a new Forest & Bird initiative that matches donors with community-run projects around the country. You can buy a predator trap on the Give a Trap website and have it delivered directly to your chosen project. Once the group receives your gift, they’ll put it to work and send you regular updates through our platform. Check it out at giveatrap.org.nz

➌ Join Forest & Bird or gift a membership to friends or whānau: Members can join their local branch and volunteer in a range of different ways and help return nature to their local community. Members also receive a complimentary Forest & Bird magazine subscription and access to Forest & Bird lodges and reserves. Go to www.forestandbird.org.nz/joinus

➍ Become a regular giver: We rely on donations, bequests, and grants to carry out our work. Setting up a regular donation is one of the most important things you can do to help restore nature in Aotearoa. If you are interested in becoming a Nature’s Future regular giver, please go to www.forestandbird. org.nz/support-us/become-regular-giver. If you already support us in this way, thank you!

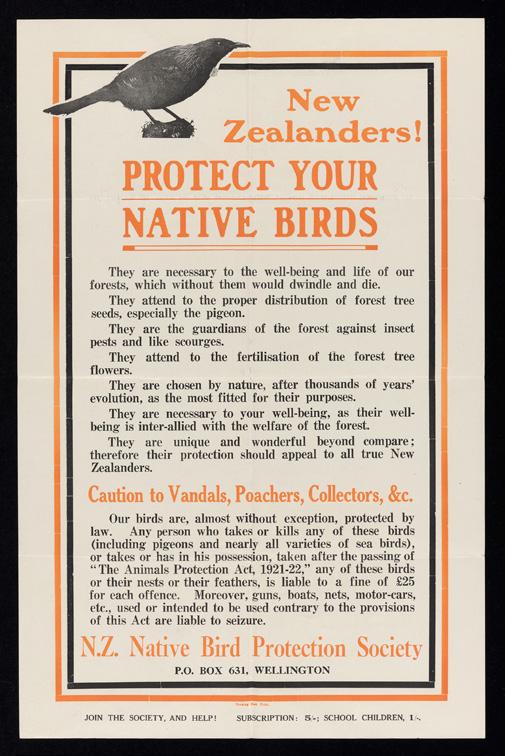

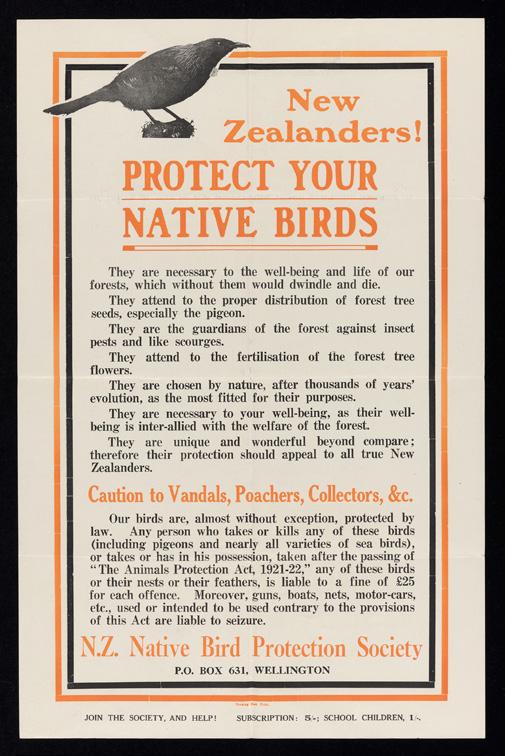

NEW ZEALANDERS! PROTECT YOUR NATIVE BIRDS

This was the title of the society’s first poster published in 1923. It was printed in different colours and and produced on paper, calico, and linen. The posters were very popular and were put up in 300 railway stations during 1923, while 2300 went into post offices. They were also seen at harbour wharves and yacht clubs, including around the Hauraki Gulf. They appeared in many schoolrooms around the country, including Native Schools, and Tararua Tramping Club displayed them in huts. The calico versions were displayed outside – for example, where forestry workers were felling trees to try to stop them shooting birds on their breaks. The Society’s early leadership claimed the posters resulted in an increase in bird populations in New Zealand’s forests.

A high-resolution version is available for branch use –email editor@forestandbird.org.nz

COVER

Pīwakawaka fantail. Jake Osborne/Flickr.com

The poster on display at Cape Kidnappers gannet colony, Hawke’s Bay, circa 1920s. Forest & Bird archives

19 Winter 2023 |

LISTEN TO THE LAND

Nature-based solutions can help heal the steep hillsides of East Cape and other weather-ravaged communities in Auckland and Hawke’s Bay. Ann

Cyclones Hale and Gabrielle unleashed devastation in Auckland, Hawke’s Bay, and the East Cape in January and February this year. It was a disaster waiting to happen, as Forest & Bird field officer Basil Graeme warned back in 1990.

He visited the Tairāwhiti Gisborne region following Cyclone Bola, in 1988, and saw for himself the erosion and destruction it had caused. He later wrote, in the November 1990 issue of the Society’s magazine, some prescient words:

“The seeds of destruction were laid in our pioneer culture which assigned too freely individual rights with property ownership. Today these rights are infringing the wider rights of the East Cape community … Today the East Cape waits exposed and unprepared for the next cyclone.”

And so it came to pass four decades later with not one but two cyclones only two months apart. What lessons can we learn from the response to Cyclone Bola in 1988 – and from decisions made around land use that go back even further, to the 1960s?

After Cyclone Bola, the government gave nearly $200m in a relief fund. It should

Graeme

have been used to buy out and retire the most severely damaged properties. Instead, it helped farmers reestablish grazing and enabled forestry companies to plant pines on the 240,000ha of category 2 and 3 (higher risk) erosion-prone land. It was a huge mistake.

Previously, in the 1960s, under the “East Coast Project”, the worst category 3 land had been retired and planted in pine trees, and these stood up relatively well during Cyclone Bola. But after Bola, these taxpayer-funded “conservation” forests were sold to private companies, felled, and replanted in pines.

Many of these forests are being clear-felled now, while the thin grass of the steep lands is still being grazed. This gave the land very little protection when the worst cyclones in living memory hit the East Cape earlier this year. Now the steep lands are an endless landscape of slips, and the downstream communities are full of mud and misery.

There are many victims in this story. There is the environment, the scarred hills, the lifeless streams choked with silt and slash, and the degraded coast beyond.

CLIMATE

Devastated farmland after Cyclone Bola. Forest & Bird archives

Basil Graeme in 1990. Forest & Bird Archives

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 20

Cyclone Bola aftermath: Motumate Stream, Kaitangata Station area, looking southwest towards Te Karaka on the Waipoua River. Lloyd Homer, Geological Survey. Published in Forest & Bird, November 1990

There are the people, Ngāti Porou hapū, the forestry workers whose incomes help sustain the East Coast communities, and the downstream farmers whose homes, paddocks, and orchards are deep in mud. And the forestry companies and hill country farmers, whose practices led to this debacle, are victims too.

We need to find a fair and sustainable way forward for them all. We must support all these communities, but, this time, we must do it in a way that offers the local people and the environment a more sustainable future.

To keep the lowlands safe, we need to protect their watershed, the steep lands behind them. The fragile hillsides of farmland and felled pines need a green cloak to shelter them from the hammering rain.

That cloak needs to be a permanent native forest, a carbon sink, protecting the soil from erosion, and the waterways and the sea from the smothering sediment. This will give the downstream hapū and communities the security they deserve.

If this is to be achieved, we need to recognise the most erodible land cannot support any further exploitation, be it for timber trees or for grazing. It must be fostered to regenerate into permanent native vegetation. But how can this be achieved on such a vast and damaged landscape?

Nature could provide a solution, but only if goats and deer are killed and stock removed. Among the thin grass, the naked slips, and pine stumps and slash, weeds will grow but so too will those native pioneers, mānuka and kānuka.

Beneath their canopy other native plants will find shelter and in time – a very long time – a native forest will grow. But for this to happen, nature must be given a helping hand. Vast areas of land need to be fenced, seeded, and weeded, and browsing pests controlled.

As for the established pine forests, many are already protecting soils and streams in the identified zones of instability. These trees must not be harvested! While they stand, they provide erosion control, sequester carbon, and shelter native species establishing beneath them.

But these solutions involve costs – enormous costs –and they deprive the landowners and the communities who depend on forestry and farming of their incomes. An alternative source of income for the landowners needs to be provided, and the Emissions Trading Scheme in its present form does not yet provide it.

These restoration actions required on the vast retired land could provide work and income. Some will need fencing. All will need ongoing pest control if goats, deer, pigs, and possums are not to undo the work of restoration.

On naked slips, planting and possibly aerial drone seeding of mānuka and kānuka will speed restoration. Forest workers might find work in fencing, pest control, planting, track cutting, and weed management. And, yes, pine trees might help (see box).

Big problems require big solutions, and the challenge of revegetating the East Cape is enormous. We must accept that, although the task lies on private land, its resolution will be a public good. We, the taxpayers, must take responsibility for this fragile landscape and its dependent communities.

It is time to value existing native forests, and the growing of native forests, as assets that pay their way in the carbon they store, the catchments they protect, and the downstream costs and damages they avert. The East Cape has been exploited for too long, and the time for restitution is now.

“Enough is enough!” says Basil Graeme, 81, who is still an active conservationist today. “Fix the Emissions Trading Scheme and provide a way out for farmers and foresters on the East Cape.”

Damage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle, Dartmoor Road, near Puketapu, Hawke’s Bay. Chantal Pagel

→

Papamoa Forest, Gisborne, is being restored with native planting, while controlling goats, deer, and possums has allowed natural bush regrowth. Barry Foster

21 Winter 2023 |

Forestry slash on Gisborne foreshore, in 2023. Barry Foster

TRANSITION FORESTS

On the most erosion-prone land where felling the existing pine forests is untenable, standing pines can be a pathway to restoring native forest. This has been given a catchy name, “transition forests”. Projects are under way, such as that being undertaken by Tāne’s Tree Trust, to find out what native plant regeneration can be achieved under pine tree stands and how their conversion can be encouraged with different environmental and planting conditions. Do they need to be thinned to help understorey growth, and can this occur without causing erosion? Will the planting of islands of missing and diverse native species speed up natural regeneration? Maybe pines themselves could be planted at wide spacing, not for timber, but to specifically act as a nurse crop to native regeneration.

WHO FOOTS THE BILL?

For the re-assigned workers, the government – that’s us taxpayers – would pay the wages. For the farmers, the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) could provide an incentive for destocking their pasture because the land will qualify for carbon credits. But for foresters, there is no incentive to leave their forests standing, as the ETS will not provide them with carbon credits if the first historical tree planting was before 1990. This is because the ETS is based on international rules aimed at stopping countries from cheating on their targets. This arbitrary date is intended to encourage new plantings on land deemed unsuitable for grazing, which is fine for East Cape farmers but disqualifies foresters who own older plantation forests, despite the carbon store they hold and the catchment protection they provide. In New Zealand, we need to reward the owners of forests that are protecting our climate, native habitats, and downstream communities. Parliament has a responsibility to fix this anomaly.

STOPPING FOREST SLASH

From the ravaged slopes, where pine trees were newly harvested, came the mountains of waste timber called slash, piled against bridges, smashed against fences, and strewn over beaches. It was often more visible than the silt and the mud, and has come to epitomise the damage caused by the cyclones. Fingers were pointed at demon pine trees, but it is not the pine trees in themselves that were at fault. It was the method of forestry. Any trees clear-felled in one go on those steep, erodible hills, leaving waste wood behind, would have led to disaster in similar circumstances. Under normal rain, this slash was expected to stay in place and act as a filter against sediment run-off. But “normal” should no longer be the expected.

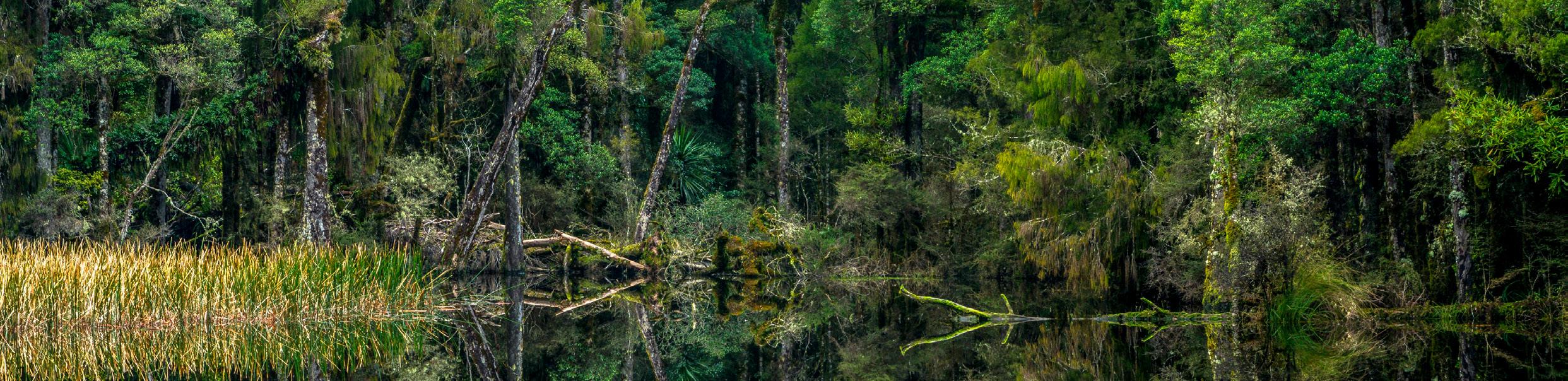

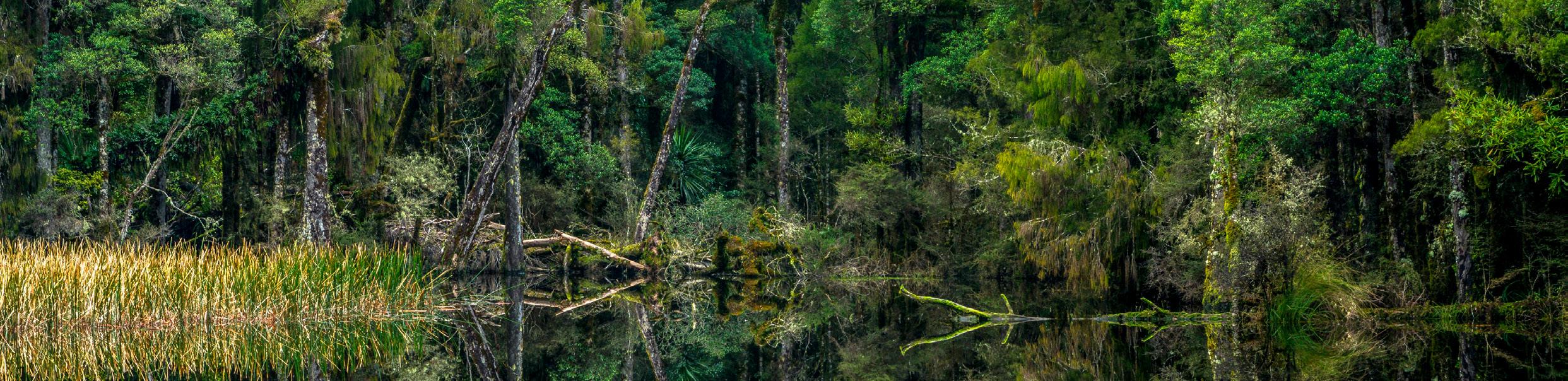

ISLAND OF GREEN

The cyclones didn’t spare native habitats either. Native forests suffered, especially those riddled with pests, their undergrowth and the spongy moss on the forest floor eaten and stomped out by deer and goats. But one place welcomed the deluge. Gray’s Bush is a swamp forest on the Gisborne plains, the only surviving remnant of an extinct forest type, an assemblage dominated by kahikatea and pūriri. Surrounded by drained and cultivated paddocks, it struggles against drying out. For years, Forest & Bird’s Gisborne Branch has cared for the forest, by controlling pests and tackling invasive weeds. A few days after Cyclone Hale, Grant Vincent, chairman of the branch, went to see how the forest had fared. “It did my heart good to see,” he said. “Streams were running down the forest paths, ponding and creating little lakes around the kahikatea and the buttresses of the pukatea. The pūriri, less fond of puddles, stood on the slightly raised ground, well watered but not water-logged.” Days after the storm had passed, the forest floor was still soaking up the flood water, an island of green in a drowned landscape.

☛ “We lost 20 years of restoration planting” – read Dean and Geoff’s climate story on page 31.

CLIMATE

Forest & Bird volunteers at Gray’s Bush, near Gisborne. Forest & Bird

→

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 22

Gray's Bush. David Lynn

The future won’t take care of itself

Earlier this year, we saw back-to-back flooding, slips, and devastation in Auckland, the Coromandel, Gisborne, and Hawke’s Bay.

We don’t wonder anymore if another extreme weather event might be coming. We know it’s coming. This is our country’s wakeup call, our turning point.

We must protect our wetlands, make room for our rivers throughout Aotearoa, and restore native forests with pest control to help stop slips on steep hillsides. This is how we fight climate change to safeguard tomorrow even as we build back today.

Forest & Bird’s freshwater advocate, Tom Kay, grew up in Te Matau a Māui Hawke’s Bay, and his family were impacted by Cyclone Gabrielle just as tens of thousands of others were.

“I wasn’t prepared for the physical and emotional destruction delivered by Cyclone Gabrielle even though I’ve worked in conservation for most of my working life and spent years learning about climate change and campaigning for action to prevent it,” said Tom.

“We can and must build our communities back better – and safer – by prioritising nature-based solutions, including restoring our

wetlands, river floodplains, and indigenous forests.”

At the end of March, Tom gave a presentation to Gisborne District Council imploring them to think about nature-based solutions as part of the region’s recovery plan. This was well received and covered in local media and on Radio NZ

In April, Tom and Dr Chantal Pagel, Forest & Bird’s regional manager for Hawke’s Bay, Gisborne, and Bay of Plenty, met with locals affected by the flooding during a visit to the region.

Tom also presented to Auckland Council, showing them how nature-based solutions could help Tāmaki Makaurau rebuild following January’s floods. This was well received by the council’s leadership.

At the time of writing, Tom and Forest & Bird’s regional conservation managers have advocated for nature-based solutions to more than 30 councils around the country –and given presentations at more than 14 community-based events. Meanwhile, Chantal is making submissions to local councils in her rohe setting out the case for including nature-based solutions in their Annual Plans. She is actively involved in the recovery plan consultation for the Hawke’s Bay. Our Northland conservation

manager Dean Baigent-Mercer is helping people nationally understand the benefits of healthy future forests. Controllling introduced browsers, for example, will stabilise steepsided forested slopes, helping them withstand storms.

Forest & Bird’s strategic advisor Geoff Keey is looking at how central government can help address some of the barriers councils are facing to implementing these kinds of nature-based solutions.

And advocate George Hobson is working on our general election campaign to encourage every political party to incorporate these policies into their manifestos.

Your donation today will help Forest & Bird advocate for naturebased solutions all over the country as we seek to engage with mayors, councillors, community leaders, government ministers, and local MPs in the run up to October’s general election.

Please give today. Aotearoa needs all of us to pitch in as we can. Every little bit helps – please donate at www.forestandbird.org. nz/climate-emergency

Together, we can protect and restore wetlands, make room for rivers throughout Aotearoa, and support healthy future forests. This is how we fight climate change.

Tom Kay in front of Redclyffe Bridge, Hawke’s Bay. Chantal Pagel

Tom Kay in front of Redclyffe Bridge, Hawke’s Bay. Chantal Pagel

FUNDRAISING APPEAL

THIS IS HOW WE FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE

Rob Suisted

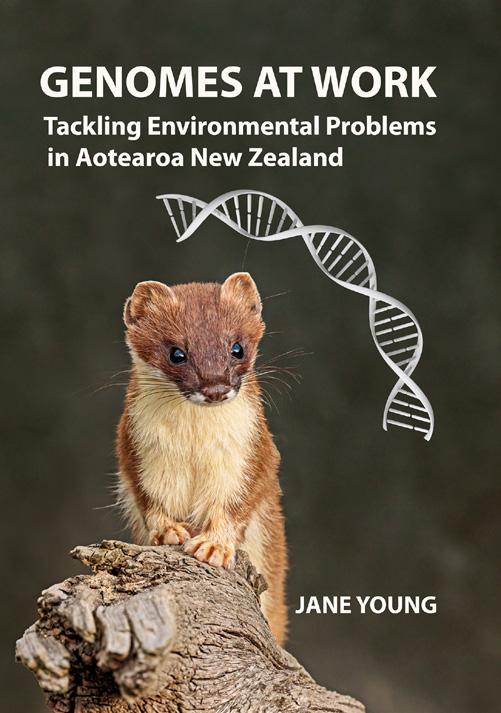

CAN GENOMICS

SAVE HOIHO?

DNA data can give us tools to aid the recovery of yellow-eyed penguins on the Aotearoa mainland, but only a change in human behaviour can give them a fighting chance of avoiding extinction, as Jane Young explains.

Hoiho are on the brink. During the last decade, despite increasingly desperate intervention measures, the number of mainland yellow-eyed penguins has plummeted by more than 70%, with no recovery in sight.

It’s possible, just possible, we can still avert a local extinction: Ban fishing in penguin foraging areas. Preserve and restore habitat. Protect penguins from disturbance by people, dogs and vehicles. And, most importantly, take action to reduce the long-term existential threat of climate disruption.

Genomic technologies also have a part to play in efforts to save hoiho. Genetic data provides vital information that conservation managers need in order to make wise decisions. And, more controversially, it might be possible to develop conservation techniques that involve direct manipulation of genetic material.

First, we can use genomics to better know a species – in this case, our iconic hoiho, proudly displayed on Aotearoa New Zealand’s $5 bill.

For a long time, we thought the yellow-eyed penguin Megadyptes antipodes was the only twig on its evolutionary branch. But, in 2009, researchers announced that ancient DNA analysis of fossil and archaeological bones in museum collections had led to a startling discovery.

There were actually two subspecies of M. antipodes – hoiho and the smaller Waitaha penguin. Then in 2015, researchers discovered a third “big diver” – Richdale’s penguin.

Humans arrived in Aotearoa sometime between 1250 and 1300CE, accompanied by kiore Pacific rats and kurī Polynesian dogs.

Within a few centuries, both Richdale’s penguin, which was restricted to the Chatham Islands, and the Waitaha penguin, found in the lower North Island and the South Island, had been driven to extinction.

Fossil and genetic evidence indicates that only hoiho survived, safe in its remote habitat in the Auckland and Campbell Islands.

Hoiho. Ross Mastrovich

FUTURE CONSERVATION

| Forest & Bird Te Reo o te Taiao 24

Conservation genomics aims to understand how the information encoded in complete sets of DNA (genomes) of living organisms can provide molecular tools for assessing their biodiversity, taxonomy, population demography, disease resistance, adaptation, and evolutionary history.

Despite their close evolutionary relationship, the three Megadyptes subspecies never got to be kissing cousins. Rare hoiho vagrants occasionally turned up far outside their normal range but didn’t establish breeding colonies.

Shortly after the Waitaha penguin disappeared, however, the advent of the Little Ice Age made the mainland a more attractive destination for the coldadapted hoiho. Within 50 years, it had taken possession of the vacant ecological niche.

Unfortunately, the limited number of founding individuals could be an Achilles heel for hoiho due to the resulting lack of genetic diversity, especially in genes that contribute to tolerance of high temperatures.

As the penguins now face an increasing number of stressors, the resultant population crashes further squeeze the genetic bottleneck and reduce the reservoir of potentially helpful variation.

There’s little hope that sub-Antarctic populations will come to the rescue. Not only is it a very long swim between the islands and the mainland, but hoiho are philopatric, meaning that when the juveniles come back from their big OE they usually return to the place where they fledged.

Consequently, the southern and northern populations are genetically distinct from each other, and there’s very little gene flow between them.

DEADLY PATHOGENS AND LIFE-SAVING VACCINES

Enormous efforts go into protecting the world’s most endangered penguin. Annual conferences bring together researchers and conservationists to share their war stories.