L ve Freshwater Fish

Ngā ika taketake wai māori o te Aotearoa | Native freshwater fish of New Zealand

If you asked most people to name some of our native birds, they would be able to – no sweat! However, ask them to name even one of our equally precious native freshwater fishes, and they’d find it a bit tricky... they might even name an introduced species, like trout, by mistake.

We want all of New Zealand to know how unique, rare, and totally loveable our native fish are too!

Some of them, like the Canterbury mudfish, Clutha flathead, Teviot flathead, and Lowland longjaw, are already in serious trouble, and we don't want them becoming part of Gretel’s exclusive crew...

Hi I’m Gretel the Grayling. I’m a NZ native fish. What do I have in common with a moa?

Inside you’ll find...

■ More about our nifty native fishes

■ Why they are having problems

■ How you can help

We can turn this all around if we work together.

Illustration: Margaret Tolland

EDITOR: Rebecca Browne

ART DIRECTOR/DESIGNER: Rob Di Leva, Dileva Design

PRINTING: Webstar, Auckland • ISSN 2230-2565

COVER Pouched lamprey (Geotria australis).

Photo by Rod Morris

I smell like cucumber and shine like metal.

My red fins make me stand out from the rest.

Name that native fish!

Need help? Go to doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/freshwater-fish to find the answers.

We like fastflowing water.

We can survive in the mud (for a time) when there is no surface water – unlike most other fish.

Otago Galaxiids

By Annabeth Cohen, Forest & Bird’s Freshwater AdvocateThe Galaxiidae family of fish was named for the beautiful gold specks in their scaleless skin. Together, these specks look like a galaxy of stars. Whitebait are our migratory (travelling) galaxiids. They go between fresh and sea water to breed and feed. But there are also dozens of other non-migratory (non-travelling) galaxiids in New Zealand that stay in fresh water their whole lives.

As they’ve been isolated by geological events, such as earthquakes and glaciers moving, each galaxiid species is unique and special.

Otago is a non-migratory galaxiid hotspot! Nearly half of these galaxiid species live there. Meet some of my favourite sparkling fish that live in this region:

Central Otago roundhead

NATIONALLY ENDANGERED

■ We live in the headwaters of the Taieri and Manuherikia rivers.

■ Our brown markings are mismatched down our backs, with a gold or silver dusting.

■ We can live up to four years.

■ We like the shallow gravel of braided rivers.

Clutha flathead

NATIONALLY CRITICAL

■ We live in the upper tributaries (river branches) of the Clutha River, upstream of Roxburgh.

■ We’re golden brown, with darker splotches and orange dusting.

■ We have broad flattened head with thick lips.

■ We can live up to 10 years.

Southern flathead

DECLINING

■ We’re found in the Waiau, Aparima, Mataura, and Oreti rivers. Some of us are even found on Rakiura (Stewart Island). We’re thought to have arrived there during an ice age when a land bridge was present.

■ We are grey brown to olive green, with dark brown splotches and mismatched patterns down our backs.

■ Our relatives are usually found high up in headwater streams away from predators. Not us! We’re typically found in the mid to lower reaches of gravel-bottomed streams and rivers.

Eldon’s galaxias

NATIONALLY ENDANGERED

■ We live in East Otago in the small tributaries of the Taieri, Waipori, and Tokomairiro rivers.

■ We’re dark grey-brown, with creamy gold bars along our bodies.

■ We can live up to 12 years.

■ We lay tiny eggs in streamside vegetation or small caves carved out of stream banks during floods.

See if you can find all the rivers named in this story on Google Maps!

Top Trumps: lamprey

They might both have long bodies and be good climbers, but that

Give each fact an epicness score out of 10 SUPERPOWERS:

Born blind

They don’t develop eyes until four years after they're born!

Changes colour, a lot

Originally, on hatching, they appear milky white, but they lose their yolk within a few weeks and reveal that they actually close to transparent (clear). As juveniles, they become a muddy brown colour (very similar to our eels), and when they go to sea they become a silvery-blue colour. When they are back in fresh water, they go a dull grey colour. Phew!

Like a vampire

These fish feed on the blood of other fish and whales.

Hitchhiker

Lamprey can hitch a ride around the Pacific Ocean on whales by using their sucker mouth to “rasp” (rub) a hole in their host.

Shark-like skeleton

Theirs is made from cartilage (firm, flexible body tissue) too.

Fresh water committed

They might spend 3–5 years feeding in the sea, but lamprey are born, and die, in fresh water.

TOTAL: /60

“Tiny Tim” is a lamprey larvae (baby). “Tim” measured just 15mm and fits on the scientist’s fingertip!

For more on the lamprey story, check out kcc.org.nz/lamprey-story

lamprey vs Eel

that is where their similarities end. Who do you judge as most epic?

By Annabeth Cohen, Forest & Bird’s Freshwater AdvocateGive each fact an epicness score out of 10 SUPERPOWERS:

Only in NZ

Longfins are an endemic species.

Heavy as, and wrinkly

These eels can reach up to 20kg (that might be as heavy as you!), and have big loose wrinkles of skin when they are bent.

Long living

Kirirua can live up to 100 years.

Longfin eel

Secretly golden

Rarely, this eel will lose their dark skin pigments, allowing their yellow colouring to be clearly seen. Can you find a rare golden longfin photo online?

Super swimmers

They travel all the way from NZ to the Pacific Islands to breed and die.

A bit different

These eels can breathe out of water through their skin.

TOTAL: /60

New Zealand has over 50 kinds of native freshwater fish. Some, like īnanga and giant kōkopu, live in shady swamps. Others, like banded kōkopu and kōaro, live in rocky streams far from the sea.

Like the eels, they too migrate. Their young float out to sea and swim back to find a lake, stream, or swamp where they will grow into adults. The tiny clear fish we call whitebait are the young of these fishes.

When the moon is full or new, the high spring tides happen. They flood up the grassy banks and into the rushes and saltmarsh.

The fish leap and turn in the moonlight. They shed their eggs and sperm on to the grass and rushes.

Which migratory galaxiid is missing from this page? Tell us at kcc.org.nz/kcc-reporters

Spring comes. The tiny fish have grown, but they are still small. They return to shore and gather into schools, together with the young of many other native fishes. Then they swim up the rivers. We call them whitebait

Lots get eaten.

The survivors find a place to live – a wetland or stream or lake. They grow into adult fish and next autumn, instinct leads them down to the sea to spawn at the full moon or the new moon, just as their parents did before them.

Next morning they swim back home. The tide falls. The eggs are marooned, stuck to the leaves and stems.

They float and feed amongst the plankton.

The fish are this small: They drift out to sea with the tide.

Weeks later, the next spring tide floods the rushes and grassy banks again. Quickly the eggs hatch into tiny fish.

The whitebait nets are waiting.

The whitebait nets are waiting.

A new Kiwi classic

These recipes were created by students from Waimea Intermediate School during their MasterChef challenge! Give them a go yourself!

Corn and Zucchini Fritters

By Lily, Brydie, and Isobel

By Lily, Brydie, and Isobel

Ingredients:

■ 2 large zucchinis, grated

■ 1½ cups tinned corn

■ ½ cup spring onions, chopped

■ ½ cup fresh parsley, chopped

■ 2 garlic cloves, minced

■ 1½ tsp cumin

■ 1½ cups flour

■ 2 free-range eggs

■ Salt and pepper (to taste)

■ 1 cup milk

■ ½ cup cheese

■ 1 Tsp oil

Method:

1 Place grated zucchinis into a tea towel. Squeeze any water out.

2 In a large bowl, combine the zucchini with the rest of the ingredients (apart from the oil). Stir all together until well combined.

3 Heat a large non-stick pan over medium heat, add the oil.

4 Using a tablespoon, scoop out the mixture. Shape it into a fritter of the size you want in the pan.

5 Cook for 3–5 minutes on each side until golden.

6 Serve warm.

Plating: Lily, Brydie, and Isobel. Photos: Millie Bourke

You don’t need whitebait to cook a tasty summer fritter!

For a vegetarian alternative, use tofu instead of chicken mince.

Chicken and Spinach Fritters

By Bailey and Claudia

By Bailey and Claudia

Ingredients:

■ 1½ cups self-raising flour

■ ¼ tsp salt

■ 1 cup milk

■ 1 egg, lightly beaten

■ Pepper (to taste)

■ Butter for pan

■ ¾ cup chicken mince

■ 3 cloves of garlic, minced

■ The juice of 1 lemon

■ ¼ cup non-sweetened Greek yoghurt

■ 1½ cup finely chopped spinach

Method:

1 Cook chicken mince until juice runs clear, but don’t brown.

2 Sift flour into a bowl, and add salt.

3 In a separate bowl, whisk egg and milk together.

4 Make a well (hole) in the flour and pour in milk/egg mixture. Whisk together.

5 Add 1 cup of spinach, cooked mince, and 2 cloves crushed garlic. Combine.

6 Heat pan on medium and add butter.

7 Dollop even amounts of batter in fritter shapes in the hot pan. Make sure there is space between them.

8 Cook until bubbles appear on the surface, then flip over. Bottom side should be golden.

9 While waiting for fritters, make sauce. Combine Greek yoghurt, rest of crushed garlic and spinach, and lemon juice.

10 Turn as necessary to ensure fritter is cooked thoroughly. Add more butter to pan as needed.

11 Serve hot, with sauce.

Plating: Bailey and Claudia. Photos: Millie Bourke

Plating: Bailey and Claudia. Photos: Millie Bourke

Our migratory (travelling) native fishes need clear paths so they can get where they need to go, upstream or downstream. However, more and more, there are things that get in their way or stop them travelling altogether. Can you get through all the human-made barriers blocking safe travel in this river?

YOU’LL NEED:

• Dice

• A counter for each player with the name of a native NZ fish on it

HOW TO PLAY:

Pick which fish you want to be, and decide if you want to travel upstream or downstream. Put your counter at the start of your course.

Take it in turns to roll the dice. Move your counter forward the number of spaces shown on the dice, and follow the path of the water. The winner is the person who gets to their destination first.

Follow the instructions on the squares. If your counter lands on one of these fish barriers, do the following…

The river has been buried underneath the ground to make way for a road or a city. Whether you get through is up to chance. Wait until you throw an even number (2, 4, 6) to travel.

The river has been blocked off. If there is a fish ladder, you can pass straight through. If not, miss a turn.

Go back to the start. Pumps are bad news for fish! You have been chopped up as you swim through the turbines.

If the bridge is “free-standing” (has a natural stream bed) – you can travel straight through. If it has a concrete foundation (bottom), miss a turn.

You’ve been able to breed successfully. You have an extra life if you land on a pump.

You’ve been able to feed successfully. With your extra energy, move 2 extra spaces.

You’ve been able to play successfully. Move to the nearest free-standing bridge in the direction you’re swimming.

aMAZE:

Say what now?... Elvers (baby eels) climb vertical wet rock faces?

Can you help this longfin elver navigate past all the barriers to reach the freshwater stream on the other side?

spot the difference:

39 of our native freshwater fish species are threatened or at risk of becoming extinct due to loss of habitat, migration barriers, and introduced predators.

Can you spot 8 differences in this wetlands photo?

did you know that NZ has over 50 species of native freshwater fish?

finish the fish:

Grab some drawing stuff and complete our redfin bully.

word hunt:

All the words hidden in our word hunt are names of fish found in New Zealand freshwater habitats. Look horizontally, vertically, and diagonally to find them and tick them off as you go

TORRENTFISH

EEL

PIHARAU

KŌARO

GREY MULLET

BULLY

WHITEBAIT

GIANT KOKOPU

GRAYLING

SMELT

LAMPREY

GALAXIIDS

To recycle The Collective’s suckies and raise money for your chosen charity or organisation join the NZ Suckies Brigade at terracycle.co.nz, or alternatively, recycle the suckies at any Soft Plastics recycling bin at selected supermarkets.

it is important to keep pathways free so our freshwater fish can migrate to or from the sea.

Support fish in your community

Native fish windsocks

Create awareness of native fish in your area by putting up special kites where they live. This activity is by Pātaka Art + Museum, Porirua. They were inspired by traditional Japanese koinobori made on Children’s Day.

Materials:

■ Piece of A4 or A3 paper or a paper bag

■ Scissors

■ Felt pens/coloured pencils/crayons

■ Cellotape

■ Decorative stickers or Duraseal to add some sparkle

■ Wire

■ String

■ Bamboo stake (or equivalent)

Instructions:

1

If you’re using a paper bag, flatten it out, open up the bottom, and cut it open on one side first.

2

At the top of the paper, make a “casing”. Fold the top edge over about 2cm, and stick it down with cellotape. Later, you will put wire through the casing.

3 Fold your paper in half lengthways.

4 Trace the īnanga template (or draw your own native fish) on each side of the paper so it matches up. Decorate your fish.

5 Once you are happy with your decorations, use cellotape to tape the paper together so it becomes like a tunnel.

Be inspired by the kites made by kids from Porirua East School with Pātaka on our blog. Go to kcc.org.nz. Search “windsocks”.

6 Thread wire into the casing to make the fish’s mouth. It should look like an “O” shape. Twist the wire together and make a loop.

7 Thread string through the wire loop.

8 Attach string to bamboo stake.

Hey! This is more like a sharp waterslide than a safe route...

Monitor fish passage and fish barriers

Ask yourself these questions when you’re out exploring your local...

n manga (stream) n awa (river)

n roto (lake) n puna (spring)

n kūkūwai (wetland)

➜ Is it safe? Sometimes structures like dams, bridges, or roads accidentally block the path of fish. That’s not safe. Other times, structures like trout barriers are needed to keep native fish safe. They stop non-native fish eating them or their eggs.

Hey! How am I supposed to climb that?

➜ Is it cool and clean? Good planting at the sides of streams will create shade, keep the water temperature cool, and give fish a place to hide or lay eggs. Planting can also reduce pollution going into the water.

Get in touch with you local DOC office, or regional council, if you’re worried about fish passage or fish barriers at your place.

How do scientists tell the age of a fish? expertAsk an

By Stella McQueen

By Stella McQueen

One way scientists can tell how old a fish is is by counting growth rings on a tiny bone in the fish’s ears. Yes, fish have ears! There is nothing to see on the outside – their ears are inside their heads.

The little lumpy bone grows as the fish grows. A very thin layer of bone is added to it every day. In summer, the fish grow fast and the layers are thick. In winter, the fish grow slowly and the layers are thin.

This is similar to the rings inside a cut down tree trunk or branch. There is one dark ring for every year the tree has been alive. Trees grow fast in summer and slow in winter. Slow-growing winter

wood is harder and makes dark rings inside the trunk or branch.

Scientists need to take the ear bone out of the fish and polish it so they can see and count the rings.

Eels can be as old as your parents or even as old as your grandparents. These fish have been alive for thousands and thousands of days. But the daily rings become very blurry in old fish, and the scientists can’t count them. Instead, they look for the layers of thick summer rings and thin winter rings. Then they can count the fish’s age in years, just like with trees.

Conservation Heroes

The Wetlands Signage Group, Porirua

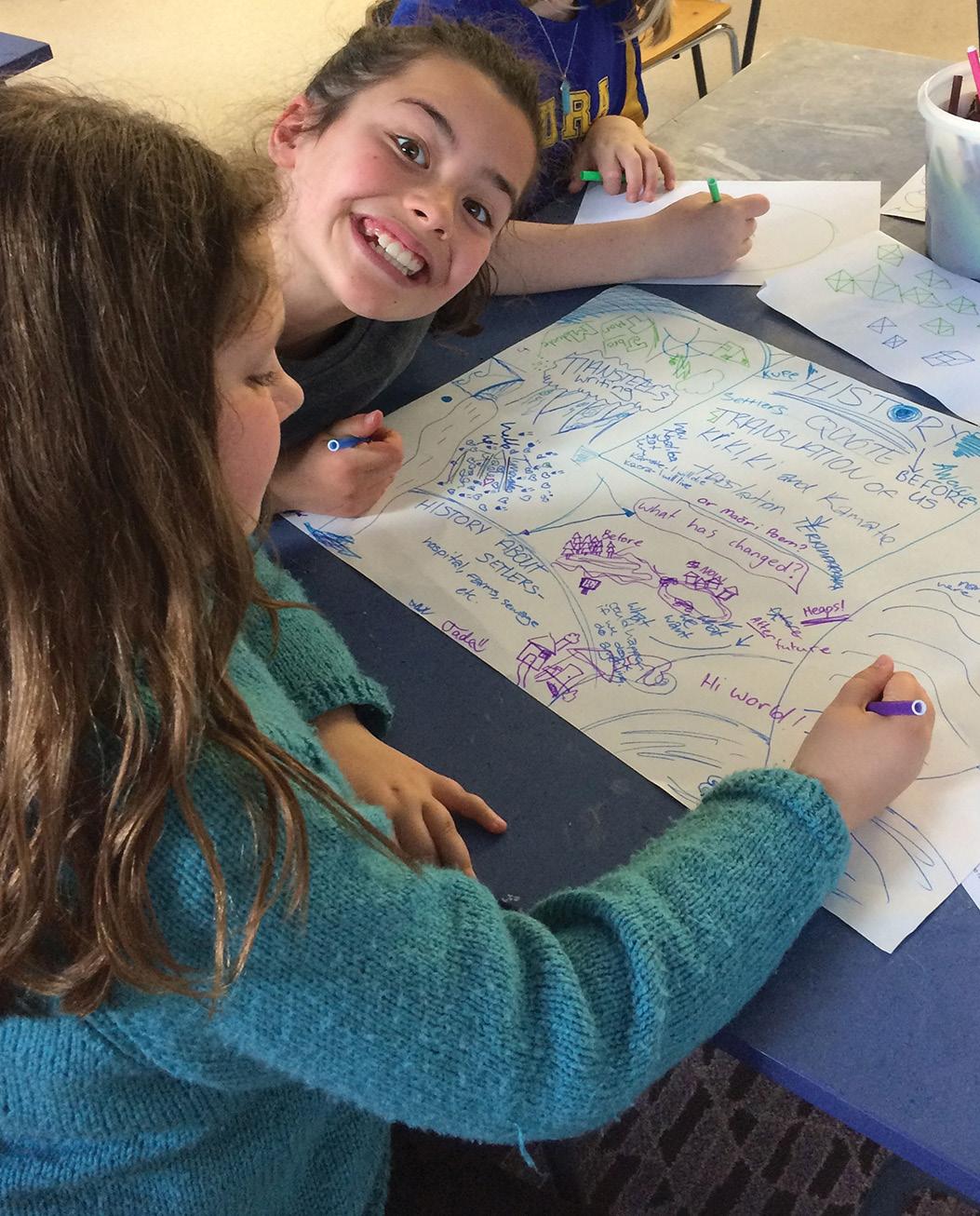

In 2017, Porirua schools came together with the Porirua Harbour Trust to speak up for Te Awarua-oPorirua.

Along with an awesome art exhibition held in the centre of the city, a student-led journal called The Current was made. The kids involved learnt that through their action and creativity they could help change people’s hearts and behaviours. The adults involved learnt too that kids can do anything with the right support! So, when the Porirua City Council came to the group this year looking to create signage for the new local wetlands area they’ve built, the group jumped at the chance to help get their community on board.

Wetlands are so important. They improve water quality, absorb water during floods, maintain water during droughts, and keep shorelines and riverbanks nice and stable. Some of our endangered plants and birds depend on wetlands to live.

Native fish need wetlands too, especially galaxiid species for spawning. Scientists have found that there is a big link between the decline of our native fish populations and the mass draining and channelling of freshwater habitats.

Porirua wetlands have been made right next the mouth of the Porirua Stream. This stream is home to five species of native fish – longfin eels, shortfin eels, īnanga, giant kōkopu, and redfin bullies.

“Our signs focus on three things: the history of Porirua, why wetlands are important, and being a kaitiaki of our harbour. Here are some pictures of us planning out the history sign.”

Tumanako (Year 7)

“Making the signs was a very fun, hands-on, and long process. We got to try and see new things, meet new people, and learn about the importance of wetlands. First, we made a draft where we just brainstormed ideas on where everything would go on the signs. We learned new techniques for making art, like watercolour and collage. We visited the spot where our signs would be displayed. The new wetlands area is behind Pak’nSave. It’s been a wee while since we finished working on the signs, so I’m excited to see the signs up on launch day.”

“Doing the signage project at Pātaka Art + Museum was amazing. We got to socialise, try new drawing and painting techniques, and use new art tools. Our goal was to produce creative, eye-catching signs for the harbour and its new wetlands area. We created numerous artworks to tell people about it. We made small groups to design and create the signs. We even had a few field trips, like when we went down to the harbour for walks, and when we made art on the shore with flowers, seaweed, rocks – anything we could find. It was a lot of fun, and I am really proud of what we created.”

We’ll put photos of the signage up on the KCC website (www.kcc.org.nz) after the launch happens so you can see them too. Search “wetlands”.

“A big thank you to Esmé Dawson, Educator at Pātaka, for all her help and support too."

Jade (Year 7)

© Wild Things Issue 141, November 2018.

Produced by Forest & Bird

© Wild Things Issue 141, November 2018.

Produced by Forest & Bird

Bug Corner

With Dr. Briar Taylor-Smith

PART 3

Toe biters (Megaloptera)

The weather is warming up, and I bet you are looking forward to going for a swim this summer. But watch out for toe biters!

“Toe biter” is a nickname for a dobsonfly (which has wings but isn’t a fly at all). In New Zealand, we have only a single species of dobsonfly and it’s the largest of all New Zealand’s stream insects, growing up to 4cm long. At first glance, you might think that this creature is a centipede. But take a closer look, and you’ll notice that the first three pairs of legs are segmented (divided into parts), while the remaining “legs” are actually the toe

On their head, they have a large pair of mandibles (jaws), which they use to catch and eat other insects, such as caddisfly and mayfly larvae, and even other dobsonflies. These mandibles are the reason for the name “toe biter”. But don’t worry, their jaws are too small to hurt you.

Briar is our KCO in Waikato

Adult dobsonfly. Photo: Jaco Grundling

Dobsonfly larvae. Photo by David Wilson

Briar is our KCO in Waikato

Adult dobsonfly. Photo: Jaco Grundling

Dobsonfly larvae. Photo by David Wilson

Giant water bugs

In other countries, “toe biter” might be a name used to refer to giant water bugs, which are completely different to dobsonflies. They are more similar to vegetable bugs and cicadas. Giant water bugs are aggressive predators with long sharp beaks, which they use to stab prey and inject saliva. The saliva then turns the prey into a liquid that the bug can then suck out, just like a milkshake. If they feel threatened, giant water bugs can deliver the same nasty “bite” to human toes. Fortunately, we don’t have giant water bugs in New Zealand!

Giant dobsonflies

A few years ago, scientists in China discovered a new species of dobsonfly. The species is the largest known aquatic insect in the world alive today, with adults big enough to cover the entire face of a human adult! The adult males have extremely large but very weak jaws. If the world’s largest aquatic insect can’t hurt you, then your toes are probably pretty safe.

Our toe biters are fussy about their homes and so are only found in clean and fairly clean hardbottomed streams and rivers. They like water so much that they spend years swimming around as larvae. If they survive until adulthood without getting eaten by fish or stoneflies, they will eventually emerge from the water as winged adults

(the scientific name for dobsonflies means “large wings”). Adults live for about a week, only long enough to find a partner and lay a few hundred eggs. See how you can measure water quality by searching out bugs, like toe biters, over the page...

Is it a healthy habitat?

Using macroinvertebrates to measure water quality

If the water is healthy, you’ll find more of these living in it… Mayflies

This information is best used when exploring hard-bottomed (stony or gravelly) streambeds.

Uncased Caddisflies

Large stoneflies

Cased Caddisflies

Dobsonflies

We are least tolerant to pollution.

If the water is ok, you will find more of these living in it…

If the water is unhealthy, you will find mostly these living in it…

We are somewhat tolerant to pollution.

We are most tolerant to pollution.

When we talk about animals or plants, “tolerance” means how well they are able to handle the conditions.

Chironomid midge (small fly)

Least tolerant = most sensitive to pollution

How’s your fresh water doing?

Photos: Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research Dragonfly larva Amphipods Damselflies Beetle larva larva Water boatmen Snails WormsAnd the winners are...

KCC 30th Birthday T-shirt competition

Age Group winners

Design a T-shirt to tell the world!

We had a huge amount of entries to our recent T-shirt competition. They filled the whole floor of one of our meeting rooms at National Office – wehi nā (that’s amazing)!

After our public vote, we had four Age Group winners.

We also had two clear Grand Prize winners too, Helena and Angelique. Here they are with their designs printed.

Thank you to everyone who submitted a design. You rock!

Carly is the winner of the 5–7 prize. Ava is a co-winner of the 8–10 prize.

Ina is a co-winner of the 8–10 prize

Carowyn is the winner of the 11+ prize

Carly is the winner of the 5–7 prize. Ava is a co-winner of the 8–10 prize.

Ina is a co-winner of the 8–10 prize

Carowyn is the winner of the 11+ prize

Grand Prize winners

A very chuffed Helena (6) in her winning design, by the sea.

A very chuffed Helena (6) in her winning design, by the sea.

KCC ADVENTURES

Electro-fishing with South Canterbury KCC

“At KCC, we learnt how to fish and saw how to do electro-fishing. It was fun. We did a lot of walking. We caught and released mayfly nymphs, two longfin eels, bluegill bullies, and torrent fish. I caught one torrent fish in a little net. To electro-fish, Rob, Austin’s dad, and a man from Environment Canterbury (ECan) went in the water, and we were not allowed in the water. The ECan man wore a back pack with a battery, and carried a pole with a thing on the end that put current in the water. Rob and Austin’s dad stood further downstream with nets in the water. The current made the fish sleepy and they floated into the net.” Kyla (8)

“I thought that it was great seeing the two eels. I have never seen eels before. I didn’t like the part when I saw that the adult eel had a bite in it. I learned not to go in the water when someone is electric fishing, because I didn’t want to get zapped.”Jenica (6)

“The suits stop you from getting zapped. You can go into the water only when they are not fishing. It was interesting when we were looking through the magnifying glass at the fishes.” Ethan (5)

“We caught some fish that had some blue on their gills – bluefin bullies. We caught lots of fish.” Emma (6)

“I had cake and went playing in the water. I caught a toe biter in the green net.” Tom (4)

Gold Wonders

ByZachary (11) from Auckland

It all started out one evening when me, my brother (Alexander), and my Dad (Glenn) were out at the local stream. Dad said he saw something unusual in the murky shallow water. Me and Alexander were intrigued when Dad said, “It was like a fish, but was probably an eel’s tail.” Me and Alexander went back the next day to investigate.

Alexander was down on a log when he said he had found something. He said, “I see something spotty under that log”, so I bent down, and saw a fish’s tail. So my mum (Nicola) contacted the council, and they advised us to try and get a photo. She did. Sure enough, it was a giant kōkopu.

Since we found the giant kōkopu, the council have protected the stream habitat by giving it a high value status, and getting contractors to undertake pest control – trapping the mice, rats, and hedgehogs so they don’t eat the eggs of the fish.

I went with Auckland Council on a night-time fish survey in January, and we found another five of these special fish in our stream! We also saw lots of kōura (native crayfish), banded kōkopu, and some WHOPPA tuna (long-fin eels)!

The local school (Upper Harbour Primary School, which I attended last year) are now doing Waicare stream monitoring and helping with the pest tracking of the stream reserve. I continue to visit the stream and help to look after the reserve edge. Next, I would like to see the Government stop whitebaiting to give these rare fish a chance.

Neat times with North Shore!

Our North Shore branch of KCC gets up to all sorts of fun together every month! This year, they went to the Parry Kauri Park near Warkworth to see a very special 800-year-old tree and learn more about pest control. They also went to Leigh Reserve and took up the role of Nature Detectives, using clues to help them learn about the native plants living there. Another cool adventure they went on recently was to Shoal Bay to spot seabirds and see the marvellous mangroves.

Where is that adventure?

Had a KCC adventure?

Let us know at kcc@ forestandbird.org.nz

Photo: Rae Claassens/Wildlands ConsultantsMailbox

30 Challenges

CHALLENGES

Download at kcc.org.nz/activities

NATURE – An Acrostic Poem

Nice sweet flowers

All around us.

Try to see a lot of nature,

Understanding that it is important.

Remember that trees give us oxygen,

Exciting, nature is beautiful!

Sierra (8)

Rowan (11) has painted a whole series of native birds

Cameron picked his own challenge –learning how to measure fish for conservation

Kāhu (4) is keen to help remove plastic from the ocean, so he’s been fundraising by selling native seedlings and saplings at his stall by his front gate

Congrats to Kāhu! You win

The Cool Pool series by Bianca Begovich and Deanna Maich (biancabegovich.org)

kcc@forestandbird.org.nz

Wild Things, P.O. Box 631, Wellington 6140 Mail

Peyton (6) did more than step out the length of a blue whale – she inflated one with her Mum and home schooling co-op!

Lucy (5) and Frankie (7) made super sun catchers!

Peyton (6) did more than step out the length of a blue whale – she inflated one with her Mum and home schooling co-op!

Lucy (5) and Frankie (7) made super sun catchers!

Hint: check out page 14

To recycle The Collective’s suckies and raise money for your chosen charity, or organisation, join the NZ Suckies Brigade at terracycle.co.nz

Caption Competition

Be

We want to get people thinking about our native whitebait species as loveable fish, rather than food. Come up with a clever/funny caption to go with this picture to help. Send it in to kcc@forestandbird.org.nz by 23 November 2018. The winner/s will feature on our Forest & Bird Facebook and Instagram pages, which reach over 100,000 people!

answers

Next time in Wild Things...

Our reader’s choice: Small and Unusual

Send in your mahi around about this topic.

You might just get published in Wild Things!

Annabeth Cohen, Forest & Bird’s Freshwater Advocate at Te Roto o Wairewa | Lake Forsyth Illustration: Margaret Tollandpart of our freshwater fish social media campaign!