The Beginning of the University Farm

Absent drought, the High Plains of Kansas produce a seasonal spectrum of vibrant colors: from the first greens that sprout after winter to the purple alfalfa blooms dotted among vivid leaves and stems, vast fields of golden wheat waving in the wind, and auburn, bronze, and ivory sorghum piling up at the co-op like sand art as the big blue sky stretches as far as the eye can see.

Of course, not everyone will notice this array of visual stimuli. Even if they do, beauty is in the eye of the beholder; some early explorers and settlers to the area deemed western Kansas the “Great American Desert” for the monotonous wasteland of the desolate, treeless plains.

Arriving in the area as a land agent in the 1870s, Martin Allen (the namesake of Martin Allen Hall) saw something different. After planting an orchard, some wheat, and a garden, Allen soon recognized that, despite the harsh western Kansas environment, the area could thrive if the people understood what could be grown and how to grow it.

Envisioning that the abandoned military reservation of Fort Hays could offer space for such a project, he sought to establish an agricultural school and experiment station. After advocating for this vision for 23 years, it became a reality when the Western Branch of the Kansas State Normal School opened in 1902 (present-day Fort Hays State University).

The teaching focus of the Kansas State Normal School didn’t match Allen’s initial agricultural vision. However, the early decades of the school’s existence rooted it firmly in its agricultural potential.

Upon its founding, the school was allotted 4,160 acres. The first Principal, Mr. William S. Picken (the namesake of Picken Hall, Principal from 1902-1912), simultaneously served as the registrar, dean, financial officer, and instructor. Among other duties, he also managed the thousands of acres of farmland, clearing the area of squatters and signing leases with tenants who rented and farmed the land.

Picken started a Farmers Short Course in 1912, in collaboration with the Kansas State Agricultural College and the Fort Hays Experiment Station, to provide a three-week intersession course that taught area farmers practical knowledge and skills. This annual offering continued into 1917 and served hundreds of area farmers, including President Tomanek’s father.

The initial seeds of Martin Allen’s agricultural vision and Picken’s support of area farmers continued to grow with President William Alexander Lewis (the namesake of Lewis Field; President from 1913-1933). Prior to his arrival in Hays in 1913, Lewis held positions managing college demonstration farms in Missouri and Utah and was tantalized by the prospect of reproducing that model in Hays.

Referred to as his one ambition in his inaugural address, Lewis saw the school’s land as a way to allow students to enter into a business partnership with the state to earn their college education “and know that they never need ask mother or father or friend for a dollar.”

The dairy started in 1914 as a teaching tool. Eventually, students were encouraged to bring cows from home to keep them at the college farm and supplement their income by selling dairy products. The dairy became one of several “projects” that generated income to supplement the college budget and supply food to the dining hall.

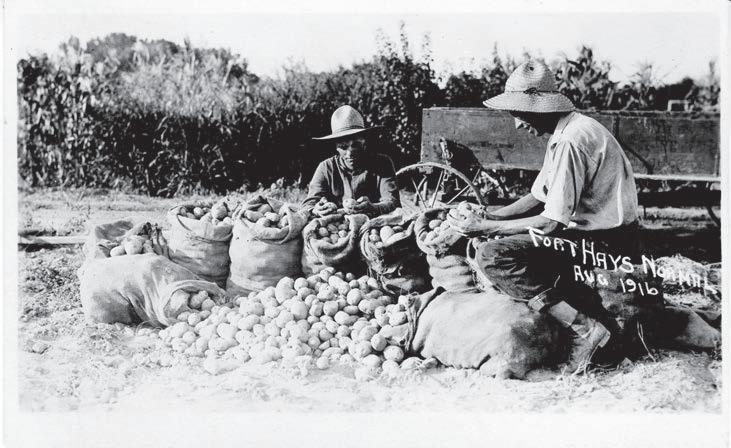

In 1915, a student organization called the Truckers’ Association was formed to turn “idle hours into cash.” Students in the Truckers’ Association applied profits from growing produce on ¼ acre of rented land to school expenses (or to pay for a trip to the World’s Fair). During the first year of this “gardening project,” 40 students committed two hours per day to grow tomatoes or cantaloupes under the direction of Agriculture Professor E. B. Matthews after he had demonstrated that as much as $150 could be produced from ¼ acre of land. That same year, Lewis developed a completed plan for the campus that included the initial farm buildings.

The following year the Truckers’ Association varied their crops and began leasing larger plots that yielded approximately $2,700 worth of produce on a mere 10 acres. Produce was sold to the dining hall, on the open market in Hays and surrounding towns, and along the Union Pacific rail line.

This profitable hobby soon became known as the field crops project, one of many agricultural projects offered to students to offset educational costs. Students leased plots for a November-to-November growing season for $9.00 per acre, covering rent, water, and overhead expenses. These enterprises taught practical, real-life skills. They included other specializations such as “gardening under glass” for winter gardening and utilizing the livestock students brought from home for the dairy, swine, and poultry projects.

During WWI, a time when victory gardens assisted the war efforts, these agricultural projects were a huge point of pride for Fort Hays Kansas Normal School. Enough food was raised and conserved that it became a self-sustaining campus.

With over 4,000 acres available, the number of students who could fund their educational expenses through these projects was “unlimited.” A Country Gentleman magazine article from December 1917 stated, “If you will farm, garden, milk cows, churn butter, raise chickens, slop pigs, peel potatoes, wash dishes or keep bees, you can get your college education [at Fort Hays].”

Frederick W. Albertson (the namesake of Albertson Hall) was secretary of the inaugural 1915 Truckers’ Association. After graduating in 1918, he began a 43-year career teaching Agriculture at Fort Hays State College, the same year the Agriculture Department began supervising all of the Normal School lands. During the Dust Bowl, Albertson studied the shortgrass prairie under adverse climatic conditions, understanding the true realities of living in the Great American Desert.

The agricultural component of this institution’s history has evolved from the initial innovation and determination required to rise above the challenges of drought, wind, and fire to turn the Great American Desert into a granary for the world. Following in the footsteps of our founders, the university’s land continues to produce. Today the University Farm operates commercially on 3,825 acres while still providing practical production experience for agriculture students. The farm includes beef, swine, sheep, and crop divisions - a reflection of the initial projects that started long ago.

at FHSUNews@fhsu.edu