7 minute read

Pay it forward

OKEY KAT

Cocktail recipe

If canned or bottled cocktails are not your thing, don’t fret...we tapped Javelle Taft, head bartender at Death & Co East Village, to create an exclusive FRANK cocktail recipe to enjoy aboard your yacht. This riff on the Boulevardier is as stiff as it is luxurious, the perfect end-of-day tipple as the sun descends on the edge of the sea.

True Wind

0.75 oz Stellum x D&C Dark Matter Bourbon 0.75 oz Rhine Hall Plum Brandy 0.75 oz Amaro Braulio 0.75 oz Sweet Vermouth

Stir ingredients in a cocktail shaker and then strain over a large ice cube in a double Old Fashioned glass. Garnish with an orange twist.

Words Rachel Ingram Photograph Sam McElwee

Pay it

forward

What does it mean to be rich? FRANK delves inside the life and mind of Dame Stephanie ‘Steve’ Shirley, the first woman to drop off the

Sunday Times Rich List after giving away so much of her money…

↑ In the workplace as a female engineer

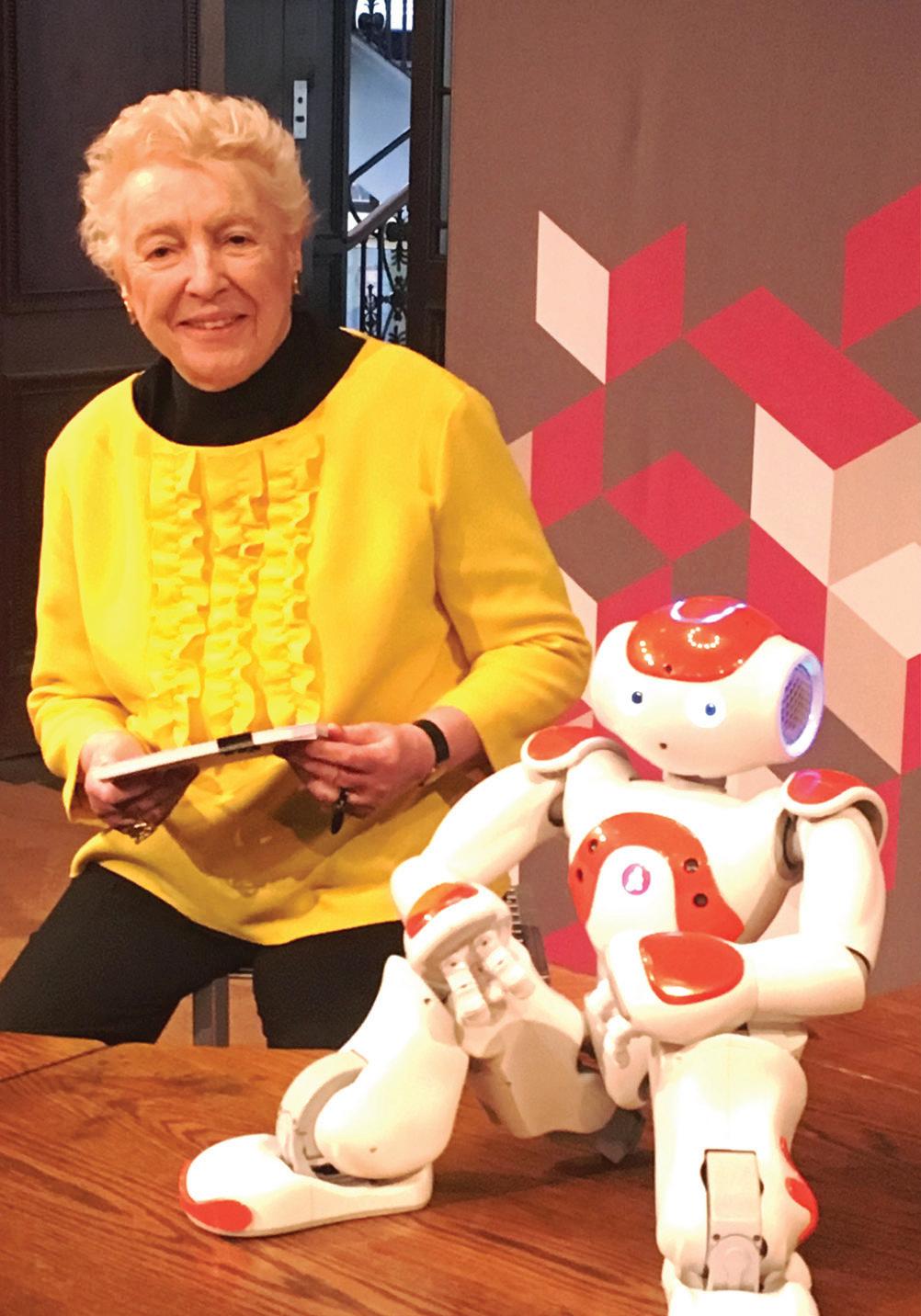

← Clockwise from top left: Dame Stephanie’s

Kindertransport evacuation document from 1939; Dame

Stephanie with a robot teacher; Dame Stephanie pictured with her Member of the Order of the

Companions of Honour medal, presented by

Prince William in 2017; As a child with a new identity and life in England. “I decided to make my life one worth saving,” Dame Stephanie Shirley CH famously once said. As one of Britain’s most pioneering technology leaders-turned-philanthropists, her unusual upbringing instilled in her an unrelenting ambition to create positive change. It’s made her a role model for entrepreneurs and women around the world.

Dame Stephanie’s life could have been different. Born under the name Vera Buchthal in Dortmund, Germany, she was one of 10,000 Kindertransport children evacuated from Germany in 1939. Uprooted and transplanted in England at the age of five, she was raised by foster parents in the West Midlands as World War II raged on; this was a defining chapter in her life.

In the early 1960s, now an adult British citizen and bearing a new name, Dame Stephanie faced her next challenge — inequality in education. In her youth, she was forced to attend a boys’ school to study math, her favorite subject. Then sexism followed her into the workplace where she struggled to have a voice among her male peers. Driven by frustration, she set up a software-selling company in 1962, originally named Freelance Programmers.

“I’d been patronized as a woman. I’d come up against the glass ceiling many times, and eventually I got fed up with it and set up the sort of business I would like to work for: a family-friendly company where women are drivers, not second-class citizens,” she says.

It was a tough sell, and her ideas were met with hostility and, often, laughter. At her husband Derek’s suggestion, Dame Stephanie got her foot in the door by signing letters using her family nickname ‘Steve’ – the name by which she would eventually become known.

Freelance Programmers gained financial and social success, working on industry-changing IT projects, such as Concorde’s black box flight recorder, and employing hundreds of women. Of the first 300 employees, 297 were women, a revolutionary feat at the time. She believes the “enormously high productivity” of a previously undervalued workforce was key to the company’s success.

By the turn of the millennium, the business was valued at almost $3 billion and hired 8,500 staff. After the company was floated, over 70 employees became millionaires. But money was never the main driver for Dame Stephanie. “We measured success by the number of single mothers, women breadwinners and disabled people we employed,” she says. “I was only the second person ever to not concentrate on the technology of computing, but on its social impact. The first was Enid Mumford; she was an academic and a theorist, but she wasn’t a ‘doer’ like I am.”

Now in her 80s, Dame Stephanie devotes her life to philanthropy. “I’ve made a lot of money and I live very nicely, but I don’t live a millionaire’s lifestyle,” she says. “I love my nice clothes and the modern art I’ve bought gives me great pleasure, but I think of wealth as something that gives me freedom of choice as to how I live, and I choose to live as a venture philanthropist.”

To date, she’s given away about $95 million, which gives her “a great deal of satisfaction, because I can see the impact from the money that I’ve made.”

Her philanthropic endeavors focus on two fields: information technology and autism. An eternal entrepreneur, Dame Stephanie prefers to build

organizations, rather than donate monies to existing entities. “As a venture philanthropist, I find problems and set up solutions for them. Like many charities, mine were born from a personal need.”

Her first charity, Autism at Kingwood, was set up to care for her son long term – “he was profoundly autistic, without speech, epileptic and clearly learning disabled from quite an early age.” After failing to find the services that she needed, Dame Stephanie set them up for her family, and others. “My son was the first resident.”

The second project, Prior’s Court, is a specialist school in Berkshire, England, for pupils with autism aged five to 25. Students learn skills, such as gardening, baking, shopping and swimming. “We’re teaching them life skills more than anything,” she says. One of the parents, who is keen on boating, even bought the school a boat and named it DAME STEPHANIE.

Her third charity is Autistica, the UK’s national autism research charity – “the most strategic of the lot.” Its focus is on giving autistic people the opportunity to live long, happy, healthy lives by funding research, shaping policy and working with autistic people to better understand their needs. It comprises the autism ‘brain bank’, which is used by hundreds of researchers worldwide. Autistica also lobbies governments to improve infrastructure for people with autism.

Where possible, Dame Stephanie draws on her expertise to combine the worlds of tech and charity. In 1999, she set up the first virtual conference on autism, which had 65,000 attendees – “it was very advanced at the time” – and at Prior’s Court, around 100,000 items of data are captured each month.

“The data tracks what pupils are doing, how they are feeling and reacting. If we can find out what is impacting each young person, we can tackle the issues and make their lives better,” she says. The school also uses robot teachers to teach nursery skills, such as copying body actions, listening to a story or walking calmly. “Oddly enough, a robot strengthens the relationship between an autistic pupil and a teacher. I think the robot gives a sense of security because they’re predictable and they don’t have facial expressions to be deciphered,” she says.

Often considered a role model, Dame Stephanie has received many accolades. She was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the Queen’s 1980 birthday honors, followed by a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 2000. In 2017, in recognition of her services to IT and philanthropy, Dame Stephanie was appointed Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH), a membership limited to 65 individuals globally.

But not all accolades are for keeping. In 2020, Dame Stephanie became the first person to drop off the Sunday Times Rich List after giving away so much of her money. “It was a very proud event,” she says smiling. “People think that philanthropists are altruistic but giving is a reciprocal relationship. We get just as much from it as we give. Giving is ruled by the heart, not the head. Often philanthropists have been blessed and their conscience says, ‘the world is biased towards me, so I need to do something to set the balance right and help other people’. And, for business people like myself, it means I can go back to being entrepreneurial, setting up new things and taking them to sustainability. That’s where I feel I can be most impactful.”

↑ Dame Stephanie delivering her TEDWomen talk in 2013