A black-and-white photograph sits on the windowsill of Samuel Davis’ room in Buckingham’s Choice, the Adamstown retirement community where he has lived since 2015.

The photograph, faded and creased with age, depicts a group of Davis’ relatives seated for a portrait. There’s his mother and her two sisters, as well as his grandmother, his grandfather and many others.

Davis never met most of the people in the picture. Many –including his grandmother, his grandfather and his mother’s two sisters – were killed in the Holocaust.

He remembers standing in his childhood synagogue in his early teenage years, shortly after his family got the news of their death, and watching his mother weep.

“That’s the last time she mentioned it,” Davis said.

The relatives his family lost in the geno cide were one reason why, two days after his 19th birthday, Davis volunteered to leave all he knew in Uniontown, Penn sylvania, to join the fight in Europe.

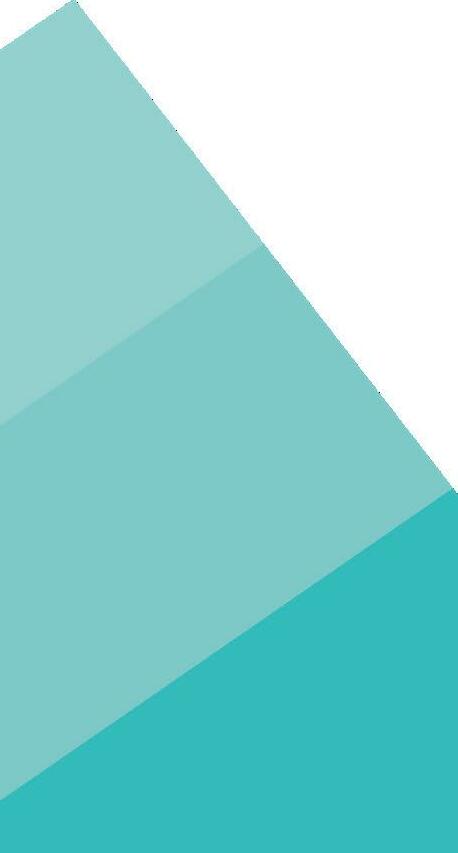

Seven decades after being honorably discharged from the U.S. Army in 1946, Davis, now 98, recounted for The Frederick News-Post stories from his three years in the service.

Sandy Turney, his only child, sat crosslegged on a nearby couch, listening intently. Most of what her father shared, she said, she had never heard. “I never talked about the war,” Davis said. “Never mentioned it.”

Davis joined the service on April 23, 1943, according to his discharge papers. He traveled to the draft office in Carmichaels, Pennsylvania, a small town about 17 miles west of Uniontown, and asked to be conscripted. He wanted to join the fight, he said, and he knew that his mother wouldn’t have let him enlist.

“I was her baby,” he said.

Plus, his older brother had already joined the war, and “one’s enough,” Davis said.

Throughout the war, Davis rarely wrote his mother letters. He knew they would only make her worry more. Although his mother spoke some English, she was a native Yiddish speaker. She couldn’t write in English.

But it was through a letter – which Davis thinks his mother asked for help to send him – that he learned his brother had been wounded in the war. Half of his brother’s face had been blown off, Davis said; he lost an eye.

Davis served with Company A of the 157th Engineer Combat Battalion. With his unit, he journeyed across Central Europe,

through Germany and France, before landing in Salzburg, Austria, toward the end of the war.

After completing boot camp in Paris, Texas, Davis and his unit traveled to England. From there, they advanced across the English Channel to northern France as part of the Normandy invasion. During the journey, Davis took off his dog tags – which identified him as a Jew – and threw them overboard. If he were captured by German troops, he suspected they would kill him no matter what. But his death was more certain if they knew his religion.

His unit arrived on Utah Beach about two weeks after the June 6 attack. He and the other soldiers had never seen combat before. They didn’t know what to expect.

They were scared for their lives. There was still fighting about half a mile from where they landed, and their commanders ordered them to dig foxholes, Davis said.

For days – he doesn’t remember how long – they hunkered down, spending most of their time sleeping and talking.

For the most part, Davis looks back fondly on his time in the service. He told stories of drinking and goofing off with his buddies in the unit, which made his daughter groan in embarrassment.

Davis was discharged from the service on Jan. 8, 1946, according to his discharge papers, about four months after U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur accepted Japan’s formal surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri.

He had never fired a gun before joining the Army and, after his service, never did again, he said.

After coming home, Davis returned to work at the store his father owned in Uniontown. He continued working in retail until he turned 90, Turney said.

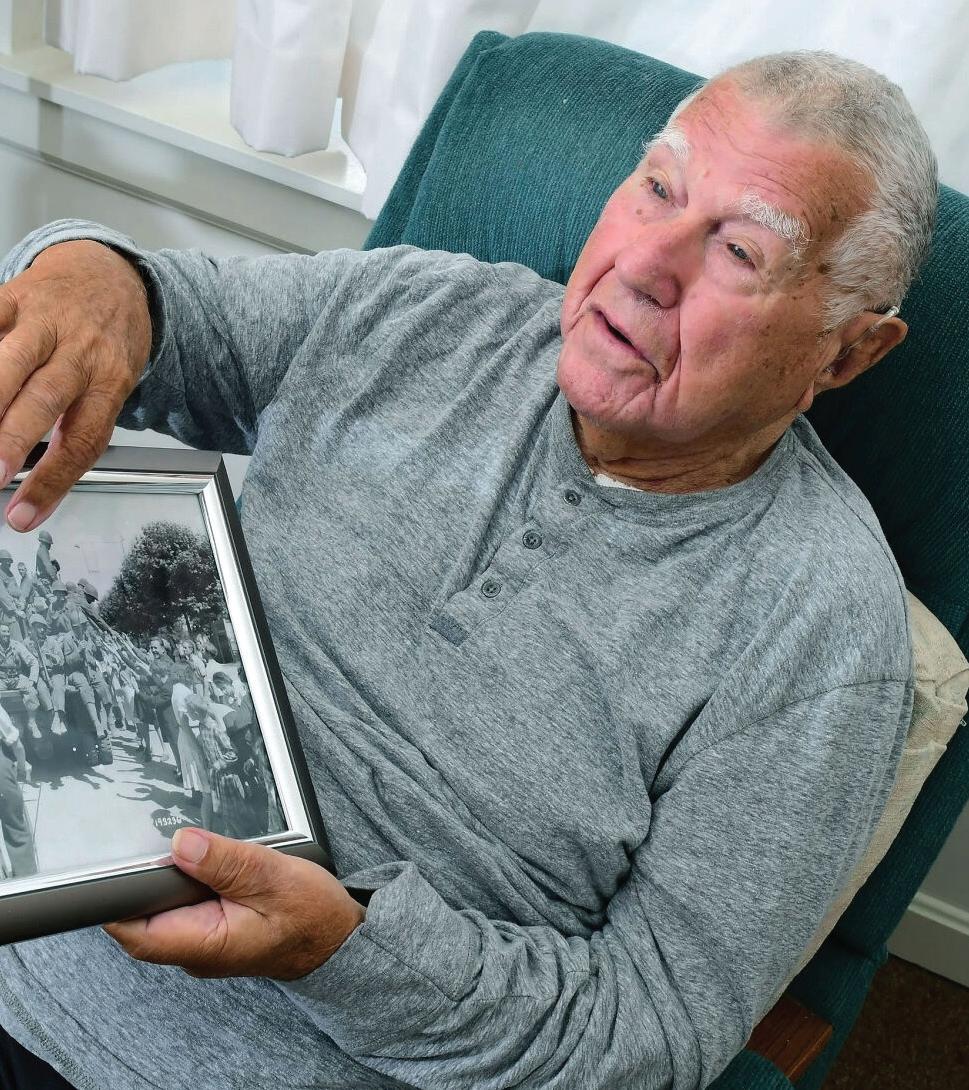

Scattered throughout his room in Buckingham’s Choice, there are reminders of his time in the service. There’s a framed photo of some of the men in his unit, gathered around a truck, and a large military map of Europe. There’s also a photo of Davis as a young man, buttoned up in his uniform, baby-faced and clean-shaven. Some reminders are more substantial.

After moving to Buckingham’s Choice, Davis discovered a connection he has with one of his fellow residents – a Frenchman who was a young child when Germany invaded his hometown. He was still living there when Davis and his unit helped free it.

Now, when the men see each other, they shake hands or give each other a hug.

ABOUT THIS PHOTO: Samuel Davis, a U.S. Army veteran of World War II, talks about a picture of his unit riding in the back of a truck in the streets of Paris, France.

ABOUT THIS PHOTO: Samuel Davis, a U.S. Army veteran of World War II, talks about a picture of his unit riding in the back of a truck in the streets of Paris, France.

He had never fired a gun before joining the Army and, after his service, never did again.

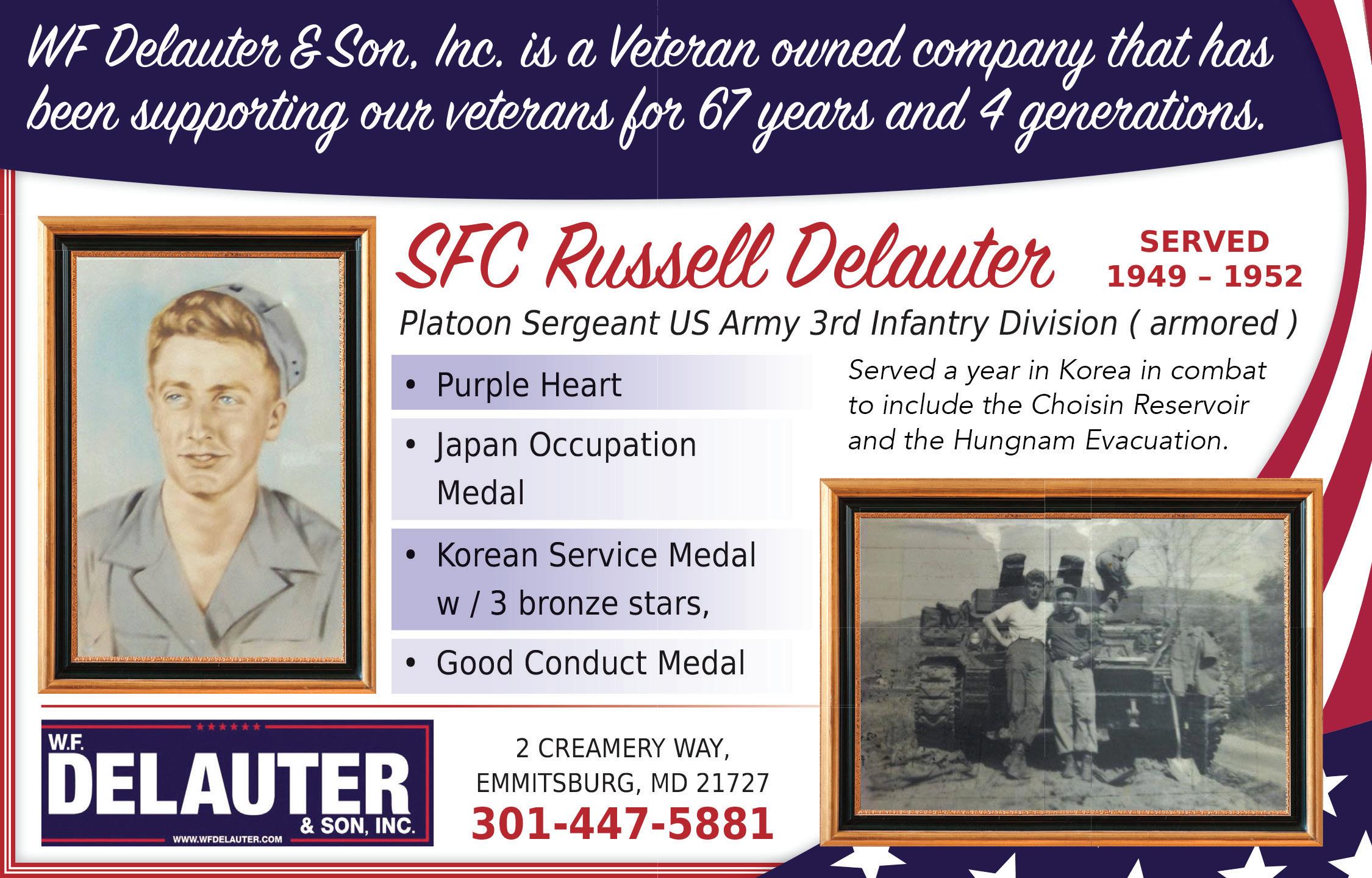

McDaniel is proud of our longstanding military tradition, which includes having one of the nation’s oldest Army ROTC programs, and we are honored to give back to our military personnel through our Military Legacy Scholarship. All military veterans, active-duty military personnel, and their children who are admitted to McDaniel as undergraduates are eligible to receive a guaranteed scholarship valued at up to $30,000 per year, and there is no limit to the number of scholarships awarded by McDaniel each year.

LEARN MORE

For more information, visit: www.mcdaniel.edu/scholarships

Shawn Rearden never saw himself as a leader but concludes his military service brought that out in him. “A few years ago, I had an evaluation and my manager at the time said you know that you’re one of the people in the OR that’s really looked up to as a leader, and I was like ‘really, why?’ I didn’t understand it – I’d never seen myself as that type of person.”

Rearden knows he wouldn’t be where he is today without his time in the service. He is a Surgical First Assistant at Frederick Health, and he’s working towards his nursing degree, on schedule to achieve that in December 2023. Rearden has been married to his wife Jen for 15 years and has a 12-year-old daughter, Molly. The Reardens make their home in Adamstown near Point of Rocks.

He enlisted in the Navy at 18 after four years of Army ROTC in high school and served for seven and a half years. The Navy was a no-brainer for Rearden as both his father and grandfather served in that branch. It also didn’t hurt that the Navy offered some of the best medical training available. As with many young men, military service offered a career path, a way to pay for college through the GI Bill and a way to get out of his small town.

Rearden misses the structure and ca maraderie at times, but doesn’t feel like he particularly needed the structure at 18. He understands, however, that many young people do. “It’s not for everyone. If you have a problem with authority, you’re not going to do well. But if you can suck up your pride and realize they are breaking you down to rebuild you in a way that will make you productive, then they’ll bring out the best in you. They definitely brought out the best in me.”

Rearden’s seamless transition from military to civilian life serves as a guide for others about to leave the service. He says it is import ant to get training that you can translate to civilian life. “Make sure you get some kind of certification that you can use when you get out. For me, Naval Hospital Corps School was basically the first semester of nursing school.” In fact, the training is so good that employers take notice right away. For his first job after leaving the military, Rearden said the hiring manager quipped, “Maybe I should interview you. No, I’m going to hire you anyway. What shift do you want to work?”

After graduating from college and looking for work in television production, becoming a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force might not initially sound like the most natural career path for Cynthia Scott, but it was the perfect one.

“The Air Force was pretty progressive,” the 66-year-old Frederick resident said. “I got to be the boss of things instead of someone’s secretary.”

Scott’s father was also in the Air Force so she said the idea to follow in his footsteps was there for a while. What sealed it for her was graduating from Emerson College in Boston but not being great at the typing tests that were required for communications jobs in the 1970s, so she enlisted in 1979 and took a job in public affairs.

This included deployments and assignments in New York City, Kansas, Panama, Argentina, Pakistan and Texas. The most notable assignment was at the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, where Scott said she was sent almost immediately after it was attacked on Sept. 11.

She could still see the smoke when she arrived, and was assigned to work on the press desk. “The media was super polite,” Scott recalled of the environment at the time.

Her main role was as a Spanish language spokesperson under the U.S. Department of Defense under former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. She worked very long shifts and was frequently at the Pentagon from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. with only one day off.

The most rewarding aspect to being in the Air Force was the culture of integrity and lifelong learning, Scott said. She especially enjoyed doing documentation of humanitarian missions under former President George H.W. Bush, and said that there was some times a “wining and dining” aspect to her role with Public Affairs.

She feels fortunate to have served when she did rather than her fa ther’s era, which included the height of the Cold War. Scott retired in 2007 and is now the co-owner of 3 Roads Communications, a televi sion production company, along with her husband. She also recently opened the Gaslight Gallery in downtown Frederick, and featured a veteran art show. Part of her heart will always remain with those serving the country. “We need good leaders so the military is used in positive, constructive ways,” she said.

From following in her father’s footsteps to being one of the faces of the Pentagon post on Sept. 11.

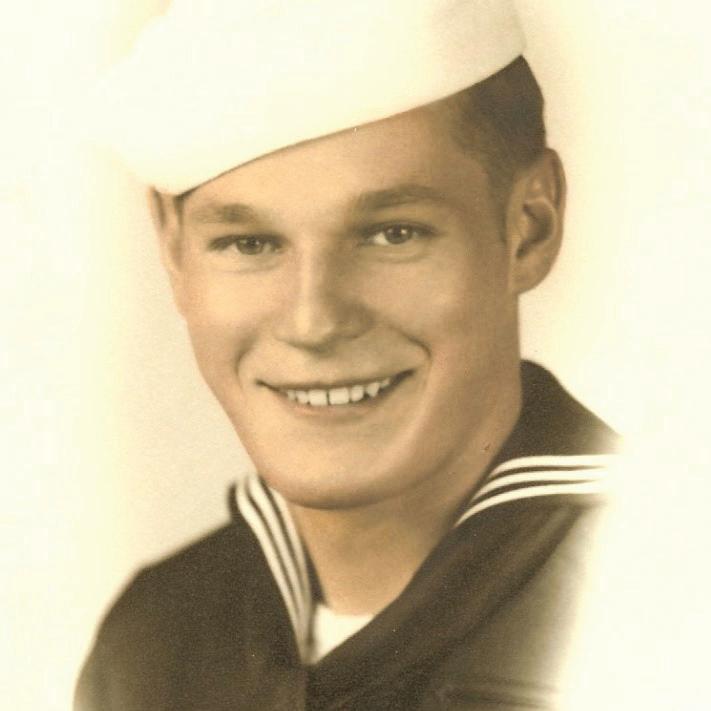

As World War II was raging on, a 17-year-old Edward Wawrzynek enlisted in the United States Navy in 1944. “Our country was at war and they were looking for people to help,” he recalls. “My buddy and I figured ‘Well let’s do our part.’”

He had two brothers who were also a part of the Navy. “I had seen a lot of Navy pictures,” Wawrzynek said. “I thought ‘Well, you have a bed to sleep in. You’ve got food. You are not out in the mud, the rain and the snow.’ It looked pretty good to us. Me and my buddy enlisted.”

After training in New York and several weeks at a base in California, Wawrzynek was deployed to the Pacific working on a landing craft ship that he described as no bigger than a tugboat. There was a lot of patrol security work involved. During the war, the Japanese forces would leave bombs in the bays and the Navy would have to find and detonate them. They would also have to vigilantly watch for one-man submarines equipped with large bombs that targeted the ships.

Once the war was over, Wawrzynek was in Japan for the reconstruction efforts doing security work. “A lot of (the Japanese soldiers) did not want to quit yet,” he recalled. He saw the destruc tion after the two atomic bombs were dropped in 1945. “If they would have tried to bomb here in Frederick, there would be no Frederick,” he said. “That is how bad it was over there. The poor kids were hungry. It was just a mess.”

He notes the Navy helped him learn about life. “I could see what I needed to do,” he said. “When I was younger, I was happy-go-lucky and getting in trouble. I was a young smart aleck. Then the Navy turned me into a man. It was fun. I enjoyed my life in the Navy. There were some tough times where we almost didn’t make it back but everything turned out pretty good.”

Wawrzynek and his wife will soon celebrate 75 years of marriage. They have seven children, 13 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. “We had a great family,” he said. “This was a great life.”

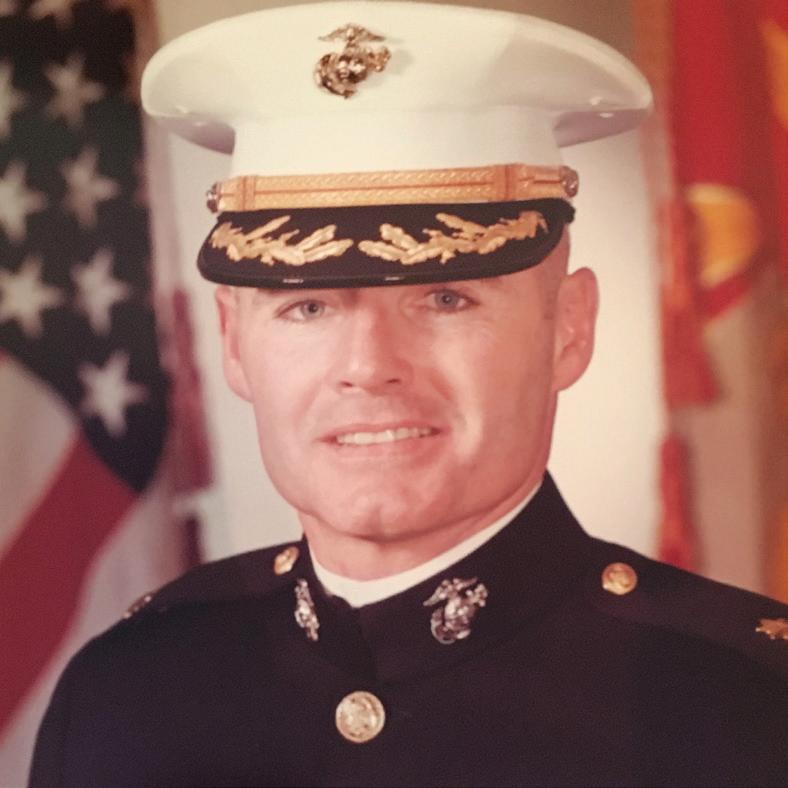

McGowan trained in Quantico, Virginia, and was stationed at Camp Pendleton in California and the Marine Barracks in Washing ton D.C. He also served as a White House social aide, and later at the Pentagon. He was stationed in Okinawa, Japan, as a weapons platoon commander. He served in Vietnam as a senior advisor to the 5th Vietnamese Marine Corps Infantry Battalion. He attended officers’ school at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He was stationed in Frankfurt, Germany, as commanding officer of the Marine Security Guard Com pany in Western and Eastern Europe. He was also enrolled at the Norwegian Na tional Defense College in Oslo, Norway.

“I tell my wife we can never say we had a boring life,” said McGowan, who can speak Norwegian and Vietnamese.

“The Marines have always hailed themselves as being the first to fight, and they prided themselves – and still do – in discipline, structure, leadership, and depending on each other, and always having each other’s backs – not that the other services don’t do that also,” he said. “I gravitated toward the Marine Corps because I knew it was a tough service and I knew that that’s what I wanted to do.”

McGowan was deployed two different times to Okinawa, Japan, on unaccompanied tours and to Vietnam for 13 months.

“One of the things that really hit home to me, not only in the combat tour in Vietnam for 13 months, but also in my Okinawa tours, it made me realize how blessed we are in the United States to have such things as running water and so forth. I was thinking we take for granted all the benefits we have in the United States. Most of our country will never see anything like that. That’s what hit home to me.”

“I learned a lot in the Marine Corps. I’ve almost always felt that I was reasonably confident, but I think it really increased my confi dence, it increased my feeling of responsibility and accountability.”

Ray served primarily in military intelligence. He was stationed in Germany twice and was deployed to Vietnam in 1968 and 1969 and 1972 and 1973. After his time in Vietnam, he was stationed in Okinawa, Japan, and Korea, where he served for five years.

“I actually first took the exam to join the Marine Corps. I was in Houston staying with a cousin and when I went to his house and told him I had signed up for the Marines, he reminded me that the Marines spent a lot of time on ships,” he recalled. “Well, at that point in my life the biggest body of water I’d seen was a lake. So, the next morning I got up, went back downtown to where they had the recruiting office and I went to the Army recruiter, and I took their test and passed it so that kept me out of the Marines.”

“I basically was like ‘I wanna get out of East Texas’ and you know they had the recruiting posters (that said) ’Join the Army, See the World.’ So I thought ‘Why not? This should be interesting,’ and it was for 20 years.”

“I did two tours in Vietnam so I guess you could call that two one-year deployments, which was sometimes hair-raising, but interesting,” he said. “I was involved in intelligence work primarily.”

At one point in Ray’s service he spent a week digging people out of a snowstorm in Northern Ohio and left the next week for Korea.

He said his unit commander in Germany allowed troops to have a cookout of hamburgers and hot dogs during a VIP visit. The worst food he ate was his daily diet of potatoes three meals a day.

“When I joined the Army in 1962, I weighed 124 pounds and by the end of my post – my last year in the Army – I weighed 160 pounds.”

On a cool October morning, James Derry welcomes a visitor into the Jefferson home he shares with his son Dennis and daughter-in-law Mary. He brings out a book on the U.S. Army’s 42nd Infantry Division, the 242nd Infantry Regiment, Anti-Tank Company, which he was a part of during World War II.

Known as the Rainbow Division, the U.S. Army infantry soldiers landed in France in the winter of 1944 and fought during the Battle of the Bulge. The division would work and fight its way from France through Germany, ending in occupational duty in Austria.

During the Battle of the Bulge, Derry was ordered to go back two miles to where they had placed daisy vines of improvised exploding devices and retrieve them under artillery fire. He placed them near a town they were defending in an effort to thwart incoming German tanks. For his efforts, Derry earned a Bronze Star, which recognizes heroic achievement during combat situations. “To win a war, you do the impossible,” he said.

He recalls a time where the soldiers went up a mountain during the night in order to get to higher ground before the Germans. Derry’s captain asked him if he thought he could drive the jeep up while the soldiers took horses and mules. “When the day light come, we were looking down on a (horse-drawn) German artillery unit. They lined up to get their breakfast and the captain said ‘Let them have it!’”

The 102-year-old, who was a driver, points to a picture of him in the book. The vehicle he drove is covered in the remains of a destroyed building. “That was our best truck,” he said. Derry had just left the building with a sandwich in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other when the Germans dropped a bomb nearby using an ally plane they somehow confiscated. Derry was not injured in the attack.

“I’m glad that we came out on top (of the war),” he said. “People don’t really realize how close we came to losing the war. Today, nobody thinks anything about it. But I dream more about it now than I did when I came home because I have the time I guess.”

Terry Sullivan was on his way to becoming an accountant at Syracuse University when the Korean War began.

He decided on the Air Force because the Korean War had started in 1950, and he was in college. His dad, who had served with the Marine Corps, suggested the Air Force.

“He told me, ‘I think you’ll do better in the Air Force than you would maybe one of the others,’” Sullivan remembered.

Sullivan, 92, enlisted and served with the Air Force from 1951 to 1955. He spent ‘51-’52 in Korea stationed with the Marine Corps. He left the Air Force as the rank of staff sergeant.

Sullivan, a Rochester, New York, native, now lives in Walkers ville with his daughter Bridget and her husband.

Sullivan said the Air Force would give tests during basic train ing to determine which training the airmen would have go in.

“They gave you a testing period when you’re in basic training in nine categories. Nine is the highest that you can get in any category,” he explained. “And when I came out, I had eight nines so I could pick anything I wanted. I didn’t know much about anything and the guy at basic kept talking about weather school.”

Sullivan was sent to Chanute Air Force Base in Illinois, for a 16-week training course.

“When we graduated there, the class before us went to Germany, and my class was sent to Korea,” he said. “You had one weekend to decide if you wanted to go to Korea or not.”

He said if airmen chose to go to Japan, they got 1 point, but if they decided to go to Korea, they got 3 points. And Sulli van said you needed 36 points to go home. After talking to a guy who had returned from Korea, Sullivan decided to get his 3 points.

The Marine Corps taught Sullivan a new skill – how to shoot.

The instructor “thought I was gonna kill guys on the base because we didn’t get much training at all in the Air Force,” Sullivan said.

He said he learned because even though he had gone to weather school, he was expected to do anything that was needed. He said on the base there were 32 World War II Corsairs, which were Navy planes.

Even though Sullivan wasn’t a pilot, he still saw action in and

around the base. He said that they usually got involved with Chinese, not Koreans.

“So you’re on alert all the time,” he said. “You kind of slept with a weapon under the cot.”

He served in Korea for a year, then on his birthday –Sept. 16, 1952 – he received his orders he could go home. He earned 36 points. But it would be another three to four days before he could find a Marine pilot to fly him out of the base to Seoul, Korea. He said it was a crazy ride, but it was worth the harrowing trip.

Sullivan ended his service in February 1955. By then, he was stationed at Niagara Falls, which was a convenient drive home to Rochester.

He married his wife Junie and they had seven children. Sullivan has 21 grandchildren, and 33 great-grandchildren. A 34th is due in March. He and his wife were married for 60 years before she died in 2013.

TERRY SULLIVANAfter the military, he got involved in several businesses.

“There was a little company forming in Rochester called Xerox,” he said. “I worked for them for three years and went back to college.”

After college, Sullivan said he owned his own business “one way or another.”

Sullivan is proud of his service and recently took part in an Honor Flight in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t know why I’m still around,” he said. “I grew up with 16 guys that all went into the Korean War. And I’m about the only one left.”

“

I don’t know why I’m still around. I grew up with 16 guys that all went into the Korean War. And I’m about the only one left.”

Thomas Denton, ETC (SS/SW), USN (Ret.), of Walkersville, spent a total of 22 years as an active duty service member. He joined up in 1973, after the draft was eliminated and the all-volunteer service began.

From his hometown of Keene, New York, Denton went to boot camp in Great Lakes, Illinois, and then to the Submarine Service at the Naval Submarine Base New London in Connecticut.

The submarine qualification process “weeds out anyone who shouldn’t be there,” he said. Not just that, it was easy to trust those who qualified. “You rely on them for your life,” he said, adding, “There’s room for everything on a submarine except a mistake.”

Once qualified, Denton was on a sub based out of Rota, Spain, and from 1975-1979 completed seven patrols on a ballistic missile sub, the USS George C. Marshall (SSBN-654). When asked about the potential for claustrophobia, he explained that a neat thing about a submarine is that “when you first got to the boat, everything is so small. But mentally it gets bigger.”

Denton said that volunteering to work on subs was kind of a spiritual event for him; his favorite hymn is “He Leadeth Me.”

“After retiring,” he said, the ci vilian world was a bit of a shock, but that he adapted.” He stays ac tive in the group U.S. Submarine Veterans, Inc (USSVI). “It’s a good way to share things we can’t share with anyone else.” He also attended a Marshall reunion last month. The aged faces might have been hard to recognize, but he said, “Once they started talking, you knew who they were. All the names pop in place.”

Denton is also a renowned artist. He paints ships, subs, lighthouses, and more, using watercolor and acrylic. The self-taught artist started drawing back on subs, when his buddies would hand him photos of their wives and he’d sketch them. Again, he acknowledges God for his artistic gifts; it’s another way he serves his country and fellow citizens, especially sailors, making his art affordable at www.submarineart.com.

For Edward Schoder, a concept put forward by Spanish priest Pedro Arrupe in the 1970s continues to resonate with him today. Arrupe, Superior General of the Society of Jesus, talked about how we should all strive to be “men and women for others.”

Schoder carried that ideal through his Catholic upbringing, Eagle Scout train ing and, eventually, U.S. Army tenure.

“I went to schools and had a family that believed in service to the country,” said Schoder, of Frederick.

Schoder, 63, attended Georgetown University on an ROTC scholarship. He served active duty in the Army from 1981 to 1985, retiring as a captain. He then spent another nine years in the Army Reserves.

EDWARD SCHODERSchoder worked in equipment maintenance and readiness. He saw many advancements in machinery during his time in the service and jokes that he realized “I have become obsolete” before his time ended.

Schoder started with the 24th Infantry Division in Fort Stewart, Georgia, when President Jimmy Carter had reactivated the mechanized infantry to support airborne divisions in the Middle East. “It was a time we’d started painting vehicles sand instead of green,” Schoder said, saying he eventually oversaw 140 soldiers.

Today, Schoder teaches English at Oakdale High School. He organizes a Veterans Day program every year in which he finds impressive keynote speakers, including area World War II veterans. “It’s nice to have the kids involved with the veterans who come,” he said. Dozens of his students have sought military service of their own.

Schoder likes to think about how military training and experi ence provides not only people skills, but also the ability to focus on a mission while looking out for the welfare of other people. “Anyone who has served in the military has important job skills when you think about mission, money and people,” he said.

“

I went to schools and had a family that believed in service to the country.”

“

“There’s room for everything on a submarine except a mistake.”

THOMAS DENTON, on the submarine qualification process

Weight served nine years in foreign countries including France, The Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, South Africa, and Japan, where he met and married his wife, Ikuko Weight, in 1958.

“There’s so many more. I flew on a lot of flights,” he said.

“It’s just something I wanted to do as a youngster. It was not a difficult decision to make. It seemed like an exciting thing to do.”

“I think that’s when my anxiety kicked in,” Weight said. WERE YOU EVER DEPLOYED?

Weight had a temporary assignment on planes flying in and out of South Africa supporting missions during The Congo Crisis. He said he saw things during that time that still trouble him today. Weight also served on support flight missions during Vietnam but was not involved in direct combat.

YEAR ENLISTED 1956 YEARS OF SERVICE 23 CURRENT AGE 84 RANK Master Sergeant

“I don’t know why I came out of it pretty well,” he said. “I think it motivated me more – in the transition out of the service.” Weight worked as an aircraft mechanic for many years after he left the military.

“The teamwork was a big thing. I miss the flying part of it, too. I was a flight engineer with special air missions out of the U.S. Air Base. We flew cabinet members and dignitaries.”

He got to know former President Gerald Ford (before he was president) on those flights.

“I’d like to help anyone who comes out of it with anxiety, but I don’t have any advice.”

When Harold “Hal” Snyder III was commissioned into the U.S. Army in 1980, the person administering the oath was very special to him. Snyder’s father stood with him at Virginia Military Institute to launch what would become the son’s 27-year military career.

Snyder attended dental school and later studied the specialty of periodontics during his early years with the Army. By the late 1980s, he was serving in Germany with an airborne infantry division and later deployed with Operation Desert Storm to practice field dentistry.

“Instead of being a chairborne dentist, I was an airborne dentist,” said Snyder, of Braddock Heights.

Using easily transportable equipment and generators, Snyder set up practice in a tent, where he concentrated on tasks like fillings and extractions to get soldiers back to their unit as quickly as possible. He credited military life and training for leadership skills, adaptability and the ability to work in austere environments under stress – traits he finds transition well to work outside the military.

“If you can succeed in the military, I think you should be able to succeed in civilian life. I think most of the people are equipped to succeed in any job,” Snyder said.

Snyder, 64, grew up “an Army brat,” moving several times due to the long career of his father, whom he described as a hard worker and great leader.

HAROLD SNYDER

HAROLD SNYDER

Snyder’s wife of almost 40 years, Kathy, supported him and their three children during several moves. Now, the youngest of his three children is on active duty at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Snyder bought his own dental practice in Frederick when he retired from the Army as a colonel in 2007.

Snyder still fondly recalls how pushing himself and being in harm’s way shaped him today.

“I think all these things help you realize you’re stronger than you think you are,” he said.

“

If you can succeed in the military, I think you should be able to succeed in civilian life.”

When Frank Abrecht Jr. was 17 in 1968, he got into some trouble in high school. His father encouraged him to join the military. His family had a member participate in every military conflict dating back to the Revolutionary War.

A U.S. Navy recruiting office would not take him due to his age, the U.S. Marines agreed to take him, with parental consent. They told him on the day he enlisted they would be giving him a call in six to eight weeks. Just a few days later, they called him and told him he would be leaving that week.

While in boot camp, his drill in structor would walk up and down the line and say “Look to your left. Look to your right. They are not coming home. Don’t make friends.”

“Being 17 and really impressionable to this day I don’t form close friendships other than family.“

Abrecht did training in a number of different areas including jungle warfare and escape and evasion. When he turned 18, he deployed to Vietnam. He served as a mil itary police officer patrolling and sweeping villages and the hillside around the air base. “I learned a lot about people,” he said. “I’m amazed at what some people can do to one another.”

He was touched by the strength of the Vietnamese civil ians who were enduring a war-torn country and still had smiles on their faces. His service took him to other parts of the world and parts of the United States.

“It took me a long time to talk to someone that had been there, done that, and they helped me understand that what I went through and what I had to do wasn’t my fault,” he said.

Danny Farrar was looking for a way out of his small town of Crewe, Virginia, when he enlisted in the Army in 1998.

“Honestly, I didn’t really have any other real opportunities where I am from,” said the now 42-year-old whose hometown population is a little over 2,000.

On his day of enlistment, Farrar said he remembers “feeling like I was finally an adult and out on my own.”

Farrar, who lives in Frederick, said he chose the Army because it “guaranteed I’d be stationed with my girlfriend at the time.”

For eight years, he served in the Army with the 182nd Airborne, The Old Guard and Multi-National Security Transition Command in Iraq. He rose to the rank of staff sergeant before he left the military.

During his tenure, he was deployed to Baghdad, Iraq.

“I remember thinking how sad it was that those people were stuck in a war that the majority wanted no part in,” he said.

Military life had a powerful impact on Farrar.

“I learned a lot of valu able lessons in the military, none more important than this. No one is coming to save you. It’s up to you. So get the mission done,” he said.

After his service, Farrar was a firefighter and EMT, and graduated top of his class. He was awarded the Chief’s award for leadership.

Today, the father of two still is proud of his duty. He is the CEO and founder of Soldierfit, which is a fitness center that uses boot camp work outs as a basis for the routines.

He is also the executive director and founder of Platoon 22, which helps to combat veteran suicide. The name comes from the statistics that 22 veterans die every day by suicide.

For those who are transitioning out of the military, Farrar said “Don’t over or underestimate your value. Find a mentor. Find a purpose. Never stop serving.”

“

I learned a lot of valuable lessons in the military, none more important than this. No one is coming to save you. It’s up to you. So get the mission done.”

DANNY FARRAR

That’s why Goodwill Industries of Monocacy Valley and Platoon 22 have teamed up to open the Platoon Veterans Services Center at Goodwill (VSC). The center brings local veteran service providers together under one roof to offer essential programs and services to veterans transitioning from service to civilian life.

Marshall was trained at the Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois, and at the Aviation Machinist’s Mate school in Memphis, Ten nessee. He was stationed at the Naval Support Facility Anacostia in Virginia and was at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland for nearly two years before being transferred to Norfolk, Virginia, where he attached to the Helicopter Squadron HS-7.

“I was fresh out of high school and all the recruiters were in Winchester Hall and I simply went in, and told the recruiter that I wanted to somehow or another be able to fly,” he said. “I talked to the Navy recruiter first and he told me that I would be able to do some of that and therefore I enlisted with the Navy.”

“At that particular time, I wasn’t going to college and was just kind of striking out on my own. I come from a dairy farm and I didn’t feel there was a future there and I was ready to try something else. At that time, it seemed like the military was the thing to do.”

Marshall’s helicopter squadron, based in Norfolk, Virginia, was assigned to the USS Randolph aircraft carrier, which was an antisubmarine carrier at the time.

“In approximately October or early November of 1962, we were sent to the Caribbean, and we spent nearly six months down there during the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

He added, “Our intelligence knew the Russians were going to set up nuclear missiles in Cuba and that was the purpose of us being down there, and in the process we was able to find them.”

“It’s one of the best experiences of my life,” Marshall said. “I mean it wasn’t always easy and all that, but the development of character and leadership and all that I attribute to being in the Navy for nearly four years.”

Retired U.S. Army and Maryland National Guard Sergeant Walter “Wes” Evans, of Smithburg, said that military service in his family “has gone all the way back to the Revolutionary War. Even before, to the colonies.”

He showed up to an Army recruiter’s office in his hometown of Fayetteville, North Carolina, and was told to come back at 17 with his mother’s authorization. To the recruiter’s surprise, Evans did and was shipped out to MEPS in Raleigh, North Carolina.

After that, he was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky for boot camp, and Fort Jackson, South Carolina, for Advance Individual Training (AIT) Wheel Mechanic School. Later he was assigned to Fort Hood, Texas, where he was a driver for the Battalion Commander and Lieutenant General, the latter of which he drove to pick up Brig adier General George Patton IV, son of the famed WWII general.

After time away from the service, Evans joined the Maryland Army National Guard. In 2001, he worked alongside the Department of Justice, FBI, CIA, ATF, and other law enforcement and underwater dive teams that searched the watershed for evidence of the anthrax letter attacks.

As the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) was being created in response to 9/11, he was assigned to the Hagerstown Regional Airport to provide security.

In 2005, Evans went down to New Orleans in response to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. He said, “We set up a complete transportation, medical, food and ice distribution center.” After Rita, Evans said, “Some of us had to help out the traumatized soldiers that were in the Astrodome. They rescued flood victims, and dealt with looting and shooting.” He called it a “real hairy experience to be there; trying to help people and still be shot at.”

It wouldn’t be his last dangerous mission. In 2007, he was sent to Kuwait and Iraq, where he saw a lot as he worked as a wrecker recovery specialist, retrieving and fixing vehicles broken down or damaged in combat. He told younger troops to stay smart, and use their heads instead of their guts, and added that everyone in his unit luckily came back alive

He retired in 2010, then went to work as a civilian for Letterkenny Army Depot. He was there for 15 years before he retired again.

In his spare time now, he spends time with family, friends, and fellow veterans, and is active with reenactments of the Revolutionary, French and Indian, and Civil Wars.

James Kennedy, 91, has lived in Frederick all his life – except for the three years he served in the Marine Corps in the 1950s. As a 19-year-old, Kennedy was inspired to enlist by his brothers and cousins, who had all served previously in the Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force.

Three of those relatives are buried in the World War II section of Mount Olivet Cemetery. One of his brothers was even captured in Germany as a prisoner of war. But that didn’t stop him from wanting to enlist. “It was my duty to serve our country,” Kennedy shared.

During his three years in the service, Kennedy was deployed for seven months to Japan at the tail end of the Korean War. One memory in particular stands out for him: hiking Mount Fuji on a Sunday off to try to “keep in shape.”

Only a few days later, Kennedy and his fellow Marines were called back to the United States, and Kennedy was discharged. Although he said he was asked to join up again later, he declined –he preferred not being told what to do.

After returning to Frederick, Kennedy got involved in groups like the American Legion and Elks Club, where he met fellow veterans. One helped him get a job at Fort Detrick, where he worked as an engineer for several years. Later, he continued his work in the civil service by working for the United States prison system, traveling around the country to visit and assess different prisons.

“I enjoyed that,” he said. “I met interesting people in the prisons and all the guards.”

His connections in veterans’ groups were also how he met his wife, Johnna. They wed in 1954 and are still married today. “She’s the love of my life,” he said. “I’d be nothing without Johnna.”

While he never had to fight in combat during his service, he said the training could be grueling, especially for advanced infantry where troops train with weapons and practiced combat.

Looking back on his time in the Marines, he thinks of his service to his country, and the camaraderie that got him through it.

“I had good relationships with all the troops. We all wanted to do the job,” he said. “I have no bad memories at all.”

When Maria Roat was in high school in the 1970s, young girls were supposed to take home economic classes. But she didn’t want to take those classes, instead opting for math, business and tech education focusing on computers.

“At that time, when I was looking at colleges, they were not teaching (computers) and I was very interested in it,” she said. “The military had a program, specifically the Navy.” She joined when women were not in the military or assigned to ships.

Through her time on active duty and later as a part of the reserves, she served in Norfolk, Virginia; Fort Worth, Texas; and Washington, D.C. Roat notes the military taught her about leadership, team building and a number of other skills to be successful.

When transitioning out of the military, she notes some don’t highlight these skills on a resume. “You can learn the technical pieces of a job or function or whatever you might be interested in,” Roat said. “The fact that you’ve got all these other skills is really what sets you up for success and I try to get people coming out of the military to think about not just your job, but what else you bring to the table because there is so much of value.”

After retiring, she worked at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for a decade in several executive roles. She also was chief technology officer for the U.S. Department of Transportation, and chief information officer for the Small Business Administration and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

YEAR ENLISTED 1981

YEARS OF SERVICE 26

CURRENT AGE 58 RANK Master Chief

When thinking back on her military career, it is the people she missed the most. “The people that I worked with over the years were amazing and tremendous,” she said. “I could not have worked with better people throughout my whole career. I also never thought as a 17-year-old that as an E1 I would ever get to where I did getting to be a Master Chief. I would never have thought that was even in the realm of possible.”

When you meet James Hubbard for the first time, a sense of quiet confidence, competence and thoughtfulness comes through clearly. And, it’s no wonder after the things he saw and accomplished in Vietnam in the late 1960s. He especially points to the story of his “alive day” – a day he not only remained alive under dire circumstances, but proved he could think and function well under extreme pressure.

March 30, 1968, was a typical hot and humid day at fire support base Fels in the Vietnam delta near the town of Cai Lay. The base served as field headquarters for an infantry battalion. Sometime after 5:30 p.m., the Viet Cong started dropping mortar rounds onto the base from about 1,000 yards away. Unfortunately, a few of the rounds caused six or seven casualties among the troops, a few very serious.

The battalion surgeon was soon on the phone asking Hubbard for a helicopter to immediately evacuate the worst casualties to a field hospital for treatment. Trouble was, it was extremely dark with no moon or stars to guide the chopper pilots. For just such an emergency, Hubbard and his men had constructed a helipad, complete with 15 slanted holes about five yards apart in the shape of a T to hold tin cans that would, in turn, hold 15 flashlights to guide the pilots onto the base. This did the trick and the chopper landed safely.

Unfortunately, the chopper, with its flashing red lights, made a good target and the enemy soon started firing again. Through the chaos of shouts, screams of wounded men and enemy fire, Hubbard and his men got the casualties loaded onto the chopper and out of harm’s way just as the last round landed near their po

sition. Extreme courage, preparation and inventiveness had saved the day. Hubbard went on to receive the Silver Star for his service in Vietnam.

YEAR ENLISTED 1966

YEARS OF SERVICE 6.5

CURRENT AGE 79

RANK Captain

In 1973, Hubbard was medically dis charged by the Army due to a serious illness. Otherwise, he would have made the Army his career. The discipline and leadership skills he learned in the Army served him well over his long civilian career as a director and lobbyist for the American Legion, where he was a frequent presence testifying on Capitol Hill. One of his proudest moments at the Legion was assisting in the approval and dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Not one to stop working, Hubbard now serves as a volunteer at Monocacy National Battlefield, giving tours and explaining what went on at this hallowed place during the Civil War. “My time in the military taught me a lot about myself, about leadership, about buckling down and getting the job done, about decision-making. It was a really en joyable part of my life, even though some of it was fraught with danger.”

Hubbard and his wife Judy live in Frederick and celebrated their 56th wedding anniversary this year. They have two daughters and four grandchildren.

Daughter Deborah Nylec helped him with his book about service in Vietnam. It’s called “From Michigan to Mekong: Letters on Life, Learning, Love and War, 1961-1968.

“

My time in the military taught me a lot about myself, about leadership, about buckling down and getting the job done, about decisionmaking. It was a really enjoyable part of my life, even though some of it was fraught with danger.”

JAMES HUBBARD

Jay Woelkers joined the U.S. Navy in 1982. He grew up in Detroit, Michigan, one of 15 children. He had a unique coming of age moment. “At 18, my parents said ‘you got to go’ because they were moving, so I went down the street and knocked on the recruiter’s door.” He originally was thinking about the Air Force, but they were closed, but the Navy guy was eating lunch. The rest, they say, is history.

Military service wasn’t new to the family. Woelkers’ father was a World War II veteran and some of his older siblings served in Vietnam. “We were a military family and hung a flag outside our door.”

He went in as an E1, and was as signed to the USS Alamo, his first and only ship. “It was scary, but exciting.”

Within approximately a year, Woelkers would graduate from the Hospital Corps School in San Diego and then to “C” School to become a physical therapy technician. Upon completion, he would be assigned to the Naval Hospital Annapolis.

Being stationed at a military academy also inspired Woelkers to enroll in college and become an officer. The process took a while, but persistence pays off. At age 29, he completed his degree and was then commissioned in the Medical Service Corps. His military career led him to become a healthcare administrator and get a master’s degree from Baylor University. He worked or served in leadership positions at medical facilities in Charleston, Cherry Point, Newport, Germany, and many others.

In 2006-07, Woelkers ran the Shock Trauma unit in Iraq and was the commanding officer in the Helmand Province in Afghanistan in 2010. His last assignment was at Walter Reed, where he walked alongside the president of the United States. “That was a big deal. Going from an E1 to being with the commander in chief was one of the highlights of my career.”

Woelkers met his wife Tracy, also a Medical Service Corps Officer, in Washington, D.C. They’ve been married going on 27 years and have six children, including a U.S. Marine currently stationed at Quantico. Last year, Woelkers retired from the Navy as an O6, or Navy Captain, with nearly 39 years of service.

After Robert Low completed four years at Erskine College in South Carolina, he was drafted by the U.S. Army in 1968. The Vietnam War was ongoing and he was sent to the front lines.

“I was 23 so I was one of the older ones because I had gone to college,” he said. “I think I matured a lot (during his time in the service). I want to say I learned how to survive. I was about six foot four and I was afraid (enemy soldiers) would say ‘Let’s kill that tall guy there.’ You learn how to survive.”

He and his fellow soldiers were sta tioned on a hill that overlooked the South China Sea. “We pulled guard every night,” Low recalled. “We could have been easily overrun but it was good ground like Gettysburg (was during the Civil War).”

One day, they decided to take a Chinook helicopter to a nearby beach to have some fun in their downtime. “We got out and bullets started flying over our head,” Low recalled. “We were in a safe place (on the hill) and then we went down to the beach to have a good time and then the bullets started flying.”

The soldiers mainly ate C-rations and the only hot food that was ever available was flown in by helicopter usually just for a major holiday. November was the monsoon season in Vietnam and Low remembers on Thanksgiving Day, the helicopter pilot was afraid to land with the heavy rain and wind. He recalls hearing a military official telling the pilot over the radio “You better land. You better get those boys that Thanksgiving din ner.” Low heard the pilot respond “Yes, sir. Yes sir.” The pilot did land the helicopter but the hot dinner was all turned upside down and jumbled up.

After his service ended in 1970, Low would go on to work for Safeway for 40 years and become a store manager.

“

We were a military family and hung a flag outside our door.”

JAY WOELKERS

Growing up, Trevor Meador viewed the military as his heroes. Both of his grandfathers and his father were in the military, so the importance of the United States’ troops was evident to him from a young age. When he was 17, he started deciding what branch of the military he’d like to join when he enlisted himself. He decided on the United States Marine Corps, as he always viewed the branch as difficult but respectable.

During his four years of service, Meador was deployed twice: once to Afghanistan and once to Jordan.

During those times, he learned about other cultures by working alongside the nations’ military and police forces.

That’s what made re-entering civil ian life the most difficult.

“One day you have 300 or 400 best friends that you’re surrounded by all the time, for better or for worse, and the next day you’re in a different state, and for the most part you really don’t see those guys ever again,” he said. “It’s a big, big culture shock.”

He describes re-entry as a lonely time, but soon enough he found community through his job as a firefighter in Frederick County. “You get absorbed into this brotherhood and the next chapter of your life,” he said. “Leaving the guys behind but having those good memories was lonely at first, but getting absorbed into a new culture definitely helped.”

Meador said there are a few things that he took away from his time in the military. One was knowing how to test his physical and mental limits. In the civilian world, he finds himself remembering times in the military when he was pushed further than he thought he could be, and knows he can handle whatever life has for him now.

Although he’s happy with his role as a firefighter, Meador said he does miss the people he served with, calling upon a quote a fellow Marine shared with him.

“He said, ‘You never miss the circus but you always miss the clowns,’” Meador shared. “I think that’s the biggest one that I miss, is the people, the Marines.”

Michael Kelly grew up in Germantown. He was in his second year at Montgomery Community College. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. 9/11 had happened and I was infuri ated by it.” A friend of his had joined before him and noticed how different he was after coming back from basic training. “He was more grown up and I thought that was the best decision for me.”

So in 2002, Kelly enlisted in the Army National Guard, attending basic training at Fort Knox and then getting advanced individual training at Fort Gordon, Georgia, the home of the Army Signal Corps. His original military occupation was as a radio operator.

He was attached to Bravo Company of the 115th Infantry Regiment out of Olney. One of Kelly’s training assignments took him to Japan, where they trained with that country’s soldiers. “That was an amazing experience.”

While on another training mission at Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia, his unit was notified that they were going to be deployed to Iraq. But Kelly was told he couldn’t go, as only the infantry soldiers were being mobilized. That didn’t sit well, so Kelly signed up to get trained as an 11 Bravo or Infantry. “I needed to be reclassified in order to go and be with my unit.”

From 2005 to 2006, Kelly and his unit were in Iraq. They were stationed at Camp Taji outside of Baghdad. For a portion of that time, they were volunteered for a mission to secure a municipal building 30 minutes away in Saba al Oor. “We named it The Alamo and fortified it, and conducted mounted and dismounted patrols.” After that, the unit was relocated to Al Asad Air Base and were charged with conducting mounted escorts of oil tankers between Jordan and back. “We were hit with IEDs on a daily basis.” Although two guys were severely injured, no one died in country. “It was the best and the worst time of my life.”

When Kelly got back stateside, he wanted to be promoted, so he transferred to a unit out of Silver Spring and earned the rank of sergeant. Kelly would spend the last couple of years with that unit.

The Ijamsville resident got out of the military in 2009. “I miss the brotherhood. I miss the training.” He is a service disabled veteran, diagnosed with PTSD and tinnitus. He also has some back damage. But at age 39, he started Kelly Floors, a service-disabled veteran-owned small business, which he attributes to his service.

A month before 9/11, Bernard Hobbs had put in his retire ment papers after already serving 25 years in the military. But that event quickly changed his mind. “I can’t do this now,” recalled Hobbs at the moment. He would go on to serve for another 14 years, culminating in 39 years of service.

Hobbs first en listed in May 1976. He was a middle child of six and his father was an alcoholic. “I needed a break from the situation I was in.” Hobbs, from Ladiesburg, discovered an Army Reserve unit in Gettysburg. The day he enlisted was a special one. “I remember feeling like I am finally going to do something.”

Eighteen of those years were spent on active duty. Throughout his career, he divided his time between active duty, serving parttime in the reserves and the Army National Guard. Much of his civilian career was spent in the construction industry. “It is difficult balancing a job, military service, and family,” Hobbs said.

After 9/11, Hobbs was deployed to Fort Belvoir in support of Operation Noble Eagle, which was initiated after the terrorist attacks to strengthen national security and support federal and other agencies. Later, he was deployed to Guantanamo as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. In 2008, Hobbs volunteered to go to Afghanistan. After nine months, he suffered a heart attack.

In August 2015, Hobbs left the Army with the rank of ser geant major. He had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and is now a disabled veteran at 64 years old. But he will never forget the positive aspects of serving in the military. “I served with all the different branches and with different armies from around the world. I was amazed at how unique and how similar we all were and how well everyone seemed to get along.”

For soldiers currently or soon to be transitioning out of the military, Hobbs has some advice. “Take advantage of everything they are offering and don’t be afraid to ask for help. I got a lot of support from my wife and family.” Hobbs and his wife Dawn have been married for 43 years.

At age 17, Melvin Hurwitz graduated from high school in 1942, but he was still too young to go into the military, which was in midst of fighting World War II. He went to Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College in Tennessee until he was able to enlist a year later.

His friend encouraged him to join the U.S. Army Air Corps because he’d “always have a bed, a hospital and food and you wear silver wings and the girls love silver wings.”

After training in St. Louis, Montana, and Yuma, Arizona, and then traveling to Florida and Maine, he was sent to Europe.

“The first real experience where I said to myself ‘Melvin, what are you doing here?’ was about 30,000 feet in an airplane and flying over Europe,” he said. “It was pretty exciting for a kid that had never been away from home before.”

Hurwitz recalls several memorable events including being a part of a humanitarian mission, Operation Chowhound, dropping food to the starving Dutch and flying into Austria to pick up French prisoners of war. “They were a terrible site to see,” he said.

As a radio gunner on a B-17 bomber, he said his time in the U.S. Army Air Corps taught him how to get along with people and about who he was in high-pressure situations. “I never thought it would come so early in my life,” he said. “I learned what it was to feel patriotic and do something about it. I hoped to make a better world.”

Last year, Hurwitz was contacted by The Best Defense Foundation, a nonprofit that provides unforgettable experiences free of charge to veterans. He got to go to Berlin, Germany, and Nor mandy, France, with events focusing on WWII.

Later in the year, the nonprofit flew him to Pearl Harbor. Hurwitz had never been to Hawaii before. He got to stay at a beachfront hotel in Waikiki and asked Alexa to play Elvis Presley’s “Blue Hawaii.” “I’ve had quite the experience for being 97 years old and I will never forget it,” he said.

“

I remember feeling like I am finally going to do something… this became me.”

BERNARD HOBBS, on the day he enlisted in 1976

After 12 years of school, Rick Weldon simply could not imagine continuing on to higher education right after graduating high school. He took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery test and scored high. Deciding to join the U.S. Navy, he was placed in the submarine service.

“It was probably the best decision I’ve made in my adult life,” he said. “I would not have been a great student. I prob ably would have been a great partier. But after four years of the discipline of serving on a ballistic missile submarine at several hundred feet under the North Atlantic, you learn a lot about yourself, your place in the world and how 137 other people are completely dependent on you for their health, safety, and life.”

Assigned to the USS Stonewall Jackson, which patrolled the waters of the north Atlantic Ocean, Weldon’s patrols were done six months out of the year with the submarine submerged underwater for increments of 68 days straight. Being in a solid steel vessel that was 425 feet long and 55 feet around, he said, he learned a great deal about human psychology including conflict resolution, creative problem solving, working with others in a confined space and responsibility.

“Those four years were incredibly important to my development as a well-rounded human being,” he said.

These skills have been useful throughout his life since leaving the Navy including during his time as a state delegate, a Frederick County commissioner, a city administrator for Bruns wick, executive assistant to the mayor of Frederick and president and CEO of the Frederick County Chamber of Commerce.

“I learned as an 18-year-old to be more kind in how I dealt with people,” he said. “That idea of focusing on the values we share as human beings was an invaluable lesson. I don’t think I would have learned it as a (college student) had I chosen that track. Military service isn’t for everybody. For those who it is right for, if you take advantage of the opportunities you are provided, it will make you a substantially more productive human being.”

Growing up as one of 12 children, Karen Gaydos dreamed of leaving her Cleveland home to see the world.

“Most of my life, starting about 10, I was babysitting, so I think, I just really wanted to get away from my family,” said the 65-year-old during a telephone interview from her Urbana home. “We didn’t have much, so the only way to get anywhere was pretty much to go into the military.”

The Army offered her the perfect escape. She was 17 when she enlisted in 1974. She served until 1979, rising to an E4. After her initial training, Gaydos was first stationed at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. From there, she was sent to Camp Humphreys in South Korea. Her last duty station was Dugway Proving Ground in Utah.

When she enlisted, the Vietnam War was still raging on. Because of that, Gaydos knew there was a possibility she could have been deployed to Vietnam but said, “I was OK with that.”

When she joined, she was a member of the Women’s Army Corps. “In 1976, that changed,” she said. “They got rid of that and women became part of the regular Army.” Today, she still has patches with the Women’s Army Corps insignia.

Women were not allowed in combat roles when Gaydos enlisted. The closest she could get to any combat was with the military police. She spent eight weeks of training at Fort Gordon, Georgia, where she was taught military law and weapons training, along with other physical training.

The Army did allow her to see the world. Her favorite place she was deployed was Korea, where she got to experience the culture. “It was so different than anything I’ve ever known,” she said, noting that at the time the base was in a rural area.

She would have made the Army a career, but she said she left after experiencing sexual harassment, which was often overlooked back then. After leaving the Army, she worked for a defense contractor in Maryland. She worked for BAE Systems and its legacy companies for 36 years before retiring in 2016.

Gaydos respects her time in the Army, which gave her “a sense of discipline that really benefits you later on in whatever career you choose.”

“I had very little confidence when I went in the Army and that’s what it gave me – a lot of confidence,” she said.

Dozier served in the U.S. Army for two years. He was drafted and deployed to fight in the Vietnam War for 11 months.

YEAR ENLISTED 1967

YEARS OF SERVICE 2 CURRENT AGE 75 RANK

E-5 Sergeant“Losing buddies,” Dozier said. Dozier said he doesn’t talk about his service often. In the past, he has given Vietnam War presentations to middle schoolers, which he found therapeutic.

Talking later about his service, Dozier said, “It was June before I took my first shower, but I arrived in February.”

“There were not too many what I would call good days –mostly bad days,” he said. “It’s not a very positive time in my life, I guess. Survival was key.”

“I think I became a more private person,” he said. “I’ve gotten more praise in the last 10 years than in the last 50 years.”

He added, “I do enjoy going to my Army reunions. As we get older the ‘whys’ become more important.”

Like most anyone enlisted at the time, Dozier spent his deployment eating C-rations.

“As long as you had the C-rations to heat it up you were OK,” he said. “The worst was if you didn’t have C-rations.”

He added, “They tried to bring us ice cream sometimes, but it was strawberry milk.”

“Get in the (Veterans Affairs) system – even if you don’t use it right away,” he said. “The VA in Martinsburg has been very good to me.”

Doug Orrison is still amazed at how a kid from Middletown learned how to ski in Europe. He has the Army to thank for his adventures.

Orrison, 62, made a career out of the Army and then the National Guard. He enlisted with the Army on Nov. 17, 1980, then served 26 years. When he retired, he was a sergeant first class.

He said he enlisted because “it was the best thing to do.”

Orrison was sent to boot camp at Fort Knox, Kentucky, then back home to Maryland to Aberdeen Proving Groups for military occupational specialties (MOS) training. He was trained as a heavy truck and tank mechanic.

After training at Aberdeen, he was sent to Germany for two years, where he received winter training. He said for a month they were taught how to ski downhill and cross-country skiing. Asked if he knew how to ski beforehand, Orrison chuckled.

“Not a chance. I was lucky we got a second stop light in Middletown,” he said.

He served with the 82nd Airborne Division, where he jumped out of planes three times a month. He said he earned an extra $110 a month, but admits before he jumped that first time “it was terrifying.”

After the winter in Germany, Orrison had the chance to spend time in warmer climates. He was stationed in Honduras, Grenada, El Salvador, and Panama.

“And some places I can’t tell ya,” he said with a laugh.

The Army appealed to him because both his father and grandfather had served. The Army really allowed a guy from a small town to see the world, which is one of Orrison’s favorite aspects of the military. “I didn’t realize I was gonna go all the places I went, but it’s something that I would have never done,” he said. “It was an adventure, and it was a learning experience. And you meet a lot of nice people.”

After serving with the Army, he joined the National Guard. He worked full time while still dedicating a weekend a month to the military. For those considering enlisting in the Army, Orrison suggests going into the National Guard first.

Orrison, who is married with two children and three grand children, said what he misses the most from his time in the Army are his fellow soldiers.

“It’s the camaraderie,” he said. “It’s a different kind of bond.”

Major Ronald “Ron” Bowers, ARNG, US ANR, MDNG (Ret.), of Maugansville, is a Marylander through and through. He was born at the foot of the Appalachian Trail and raised in Boonsboro.

He regularly attended Beaver Creek Christian Church, where he met two young soldiers in the Army National Guard. “Their in fluence started on me when I was 10, 12,” he said.

In 1963, Bowers was inspired to join the Maryland National Guard, and as a young officer, saw violence right away. He was stationed in Cambridge, during the race riots. “I don’t think I had even gone to basic training then,” he recalled. Four years later he was stationed in Patterson Park in Baltimore

after the murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bowers also remembered the assassina tions of John Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy. “Back then we were in the guard to keep peace.” When asked how those tumultu ous times compared to the present era, Bowers called it a very scary and unsettling time. “A lot going on,” he said. “A lot that I missed because I was the establishment. Women’s Rights, the Woodstock Era. The times were extremely volatile.” He said that time “gave me a life lesson to work with people of all ethnicities. And to command.”

As a lieutenant, Bowers commanded the unit in Hagerstown, in a building on Willard Street for seven years. “I was in when we got the first woman in our unit. Started out with one. That was an experience. Housing them, making sure nobody could get to them in their quarters.”

As he talked about his transition out of the military, Bowers advised: “Use what

you learned to parlay your career into more than you imagined you can do. Some people sell themselves short. Take yourself to the next level and higher.” He added that “Military leadership ... put me where I wound up in civilian life.”

Bowers retired from the military in 1983, and worked for the state of Maryland as the administrator for the Property Tax Assess ment Appeals Boards. He was close with then-Baltimore Mayor William D. Schae fer and many governors over the years. He also served over 20 consecutive years as a Washington County commissioner, the longest serving member, including time spent as its president.

“My military experience not only provid ed leadership opportunities, but guided me in listening to others, working with others. Being able to handle situations like running a business or county that others can’t do. You have to recognize peoples’ talents and pick them for the right circumstance.”

“

I was in when we got the first woman in our unit. Started out with one. That was an experience. Housing them, making sure nobody could get to them in their quarters.”

Gary “Michael” Rand of Frederick had just been married a month to his high school sweetheart when he was drafted in 1967 and shipped to Vietnam.

The 76-year-old Palm Beach County, Florida, native, served with the First Air Cavalry, where he rose to the rank of sergeant E5 when he left in 1969.

He spent a year in Fort Benning, Georgia, and Fort Polk, Louisiana, before he was sent to Vietnam in February 1968.

When he landed, he received a combat infantryman badge the same day. “I was in combat the very first day, which many soldiers are very proud of that,” he said.

Rand uses a quote to describe his experience: “There are no unwounded soldiers in war.”

“What that means is that a lot of times you can’t see how they’re wounded,” he explained, noting that today it’s often referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD.

Rand was wounded several times in Vietnam.

“So I always tell the joke I wasn’t a good ... soldier because I kept getting blown up or shot,” he said. “The first time was May 12, 1968,” which wasn’t long after he got there. Once back in combat, he was wounded again on June 5, 1968. This time, he was shot in the head and sent to the USS Repose.

He still has shrapnel in his head, back and chest.

He credits the love of his wife, Donna, for helping him make it through the darkest times. “She motivated me a lot to stay alive,” he said, noting they have three children and eight grandchildren.

Today, he still keeps in touch with two of his combat buddies. They text and chat regularly. He thinks a lot about his time in Vietnam every day. In 2018, he wrote a book called “WW Vietnam” about his time in Vietnam.

After serving with the Army, Rand returned home and attended Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was a registered architect for nearly 40 years.

Rand advised others transitioning back from the military to find others to talk to about their experiences.

“You’re gonna be depressed,” he said. “You need to talk to some people. You need to talk to the VA. If you can’t get out there, there’s an organization called Disabled American Veterans. Just talk to someone.”

Middletown native John Bussard can still remember the most extraordinary thing he ever saw as a Naval hospital corpsman.

“A beating heart in an open chest,” he said.

Bussard, 81, enlisted in the Navy in 1960 and served until 1965, earning the rank of E-4.

He completed boot camp and hospital corpsman training at Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois before transferring to Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Washington, D.C., where he spent a year and eight months.

After that, Bussard said he applied for advanced training and was sent to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where he was trained as an operating room technician. He stayed there for three years.

“At that time in the Navy, after four years of shore duty, you had to transfer to sea duty,” he said. However, after four months he had to return to shore to deal with family issues and decided then to end his career.

Bussard said he decided on the Navy “probably at that time to get out of Middletown Valley.” Also, his older brother Frank had already joined the Navy. Later, their younger brother Ray joined as well.

Bussard said being in the Navy was something he enjoyed.

“My experience was amazing,” he said.

Bussard said what he learned the most from his time in the Navy was discipline. “With the military, you learn the rules, and you keep the rules,” he said. “If you don’t keep the rules, you pay the penalty.”

“I attribute some of my OCD from working in the operating room,” he said. “Because in the hospital corps, there’s a place for everything and everything in its place.’

When he left the Navy, he applied for a job at the hospital in Frederick. “Unfortunately at that time, the concept of a male nurse hadn’t reached Frederick by 1965,” he said. So Bussard decided to become a draftsman instead. He did that for 50 years before retiring.

Bussard lives in Ocean Pines. He’s married and the father of five children. He also gives back to his fellow serviceman and is adjunct of American Legion Synepuxent Post 166 in Ocean City.

“I would recommend that veterans leaving active duty hook up with an American Legion or VFW,” he said. “There’s a lot of camaraderie there. There’s a lot of storytelling. It’s really helpful. I think that’s one thing that some of the troubled service members are missing.”