FRIEZE WEEK

SKINCARE BACKED BY 25 YEARS OF ANTI-INFLAMMATORY SCIENCE

SKINCARE BACKED BY 25 YEARS OF ANTI-INFLAMMATORY SCIENCE

WOULD EVERY OTHER ORGAN

What kind of place is an airport? A place between local and global, where languages mingle, wide vistas open up. As the location for Frieze Los Angeles, this week Santa Monica Airport will become a place of creativity too: with over 120 galleries, Focus and Spotlight sections, and Frieze Projects by the likes of Ruben Ochoa (p. 24), Alake Shilling and Jennifer West, among others a col laboration with the Art Production Fund, whose Director Casey Fremont is a recent LA a rrival (p.27). As well as showcasing this activity, and other highlights of the week across the city (like the survey of Simone Forti, of which Gillian Garcia went behind the scenes to create our cover image), this issue celebrates the art of the fair’s new environs: from Don Bachardy (p.10) and the late Chris Burden (p.8) to Jay Ezra Nayssan (p.14), curator of the off-site program ‘Against the Edge’. As Nayssan explains in his guide (p.16), stories of exile and reinvention sprawl throughout the Westside: an area crisscrossed by comings and goings. Like an airport, perhaps? In any case, I can’t wait to explore it more.

Matthew McLean, Editor & Creative Lead, Frieze Studios8 In Dreams

Anne Imhof’s take on Chris Burden

10 Face to Face

Jonathan Griffin Meets Don Bachardy

12 Always on Time

Suzanne Lacy in Conversation

14 Home Is Where We Start From

Travis Diehl on Del Vaz Projects

16 West side Stories

Jay Ezra Nayssan on ‘Against the Edge’

22 Deutsche Bank

24 The Value of Vendors

Patricia Escárcega on Ruben Ochoa’s Frieze Projects

27 Coast to Coa st Casey Fremont Brings Art Production Fund To the Fair

28 It’s Our House Lyndon Barrois and Janine Sherman Barrois’s Bold Approach To Living with Art

40 Simple Pleasures The Joy of the Good Liver

42 Lean In A Visual Essay by Gillian Garcia

54 Frag ment by Fragment Members of GYOPO on Korean Art At LACMA

The late Chris Burden is indelibly associated with Western Los Angeles, with some of his most significant performances taking place in Venice, where his studio was located on Oceanside Drive. As her first LA exhibition opens during Frieze Week, artist Anne Imhof reflects on Burden’s unique vision of the cityscape.

Chris Burden’s art has resonated with me a lot in my development as an artist, ever since I first read about it in ‘Out of Actions’ (1998), curated by Paul Schimmel. His view of performance as threedimensional sculpture aligns completely with the way that I compose my performance pieces. They are a total world to be stepped into, and seen in the round. For Shoot (1971), I somehow always pictured the audience as super close to the action, but revisiting the pictures , I realized people are quite far away, as is the guy shooting him. It’s a circus action, like a knife thrower. That distance is deliberate and part of the piece. Standing in front of a white wall, observed from a distance, Burden becomes an image. The image is sculptural. It’s as if the idea of the performance manifests in a sculptural way. Creating what you want to say in the photos of your piece is something that has to do with you gaining control. I think that’s what Burden’s work is about control. Who’s controlling whom? What are you allowed to do? What freedom does an artist have? What power? It’s interesting to me to think about Shoot taking place at the start of the decade that sees the Red Army Fraction or the Symbionese Liberation Army, who asked versions of these questions too.

But this is also a generation super aware of the media and TV. They all counted on a kind of fame. That does something to the reality effects of these images. If you look at Hans Namuth’s photos of Jackson Pollock painting, they are almost like a film strip. You see Pollock doing what he’s doing as it happens. But with the documentation of Burden’s performances, you see the moments after events. In the Shoot documentation, you have the proof that something happened. You see the blood running down his arm, but you don’t see the bullet. It’s the same in the images of 747 (1973). You don’t see the bullet, or even know if the bullet could have hit the plane. So it just hits a nerve of this possibility, of crossing over a boundary. It was only the artist and the photographer there, nobody else.

I think Burden’s work is in this way a lot about dreams. In the photographs of

747, there’s a white sky, but if you see the sky in LA, it’s never white. It’s the most beautiful, blurred dome that opens up above you over the huge Pacific ocean. When I first saw the Pacific I thought, “Wow, this is more overwhelming than anything I have seen in my life.” It’s almost too big to be anything you could have ever imagined. The dream of shooting down an airplane is about something bigger than you too.

I read that Burden had his studio on Venice Boardwalk. So, every day he was looking out on the beach, the palm trees and the sea, and he must have seen the airplanes constantly taking off from LAX. That was something that surrounded him. It’s that weirdness where your artistic practice and everyday life go inside each other and almost merge. It’s almost a case of, “I did this because it was in front of me.” Like falling in love with some person because they crossed me on the street.

I love how in this way the artist uses this city of big streets and cars, accidents and palm trees, as his material. The geographical context gives Burden’s work a map, a place and time. It lends an almost cinematic quality, that lives on like a movie you can replay. LA itself is so connected to film and the idea of fame. When Anne Wagner wrote about Burden, she quoted this Beatnik poet Stuart Perkoff about the city being “a dream, a container of dreams, a structure”, but also “a limit and a tool.” As I spend more and more time in the city for my upcoming show, I find this huge raw potential for creating new worlds, whether through the dreamworld of film or the endless possibilities of getting on the freeway. That’s what I want to achieve in my exhibition to create another world for the viewer to become embedded in, like a player in a video game.

As told to Matthew McLean Anne Imhof is an artist. She lives in Berlin, Germany.

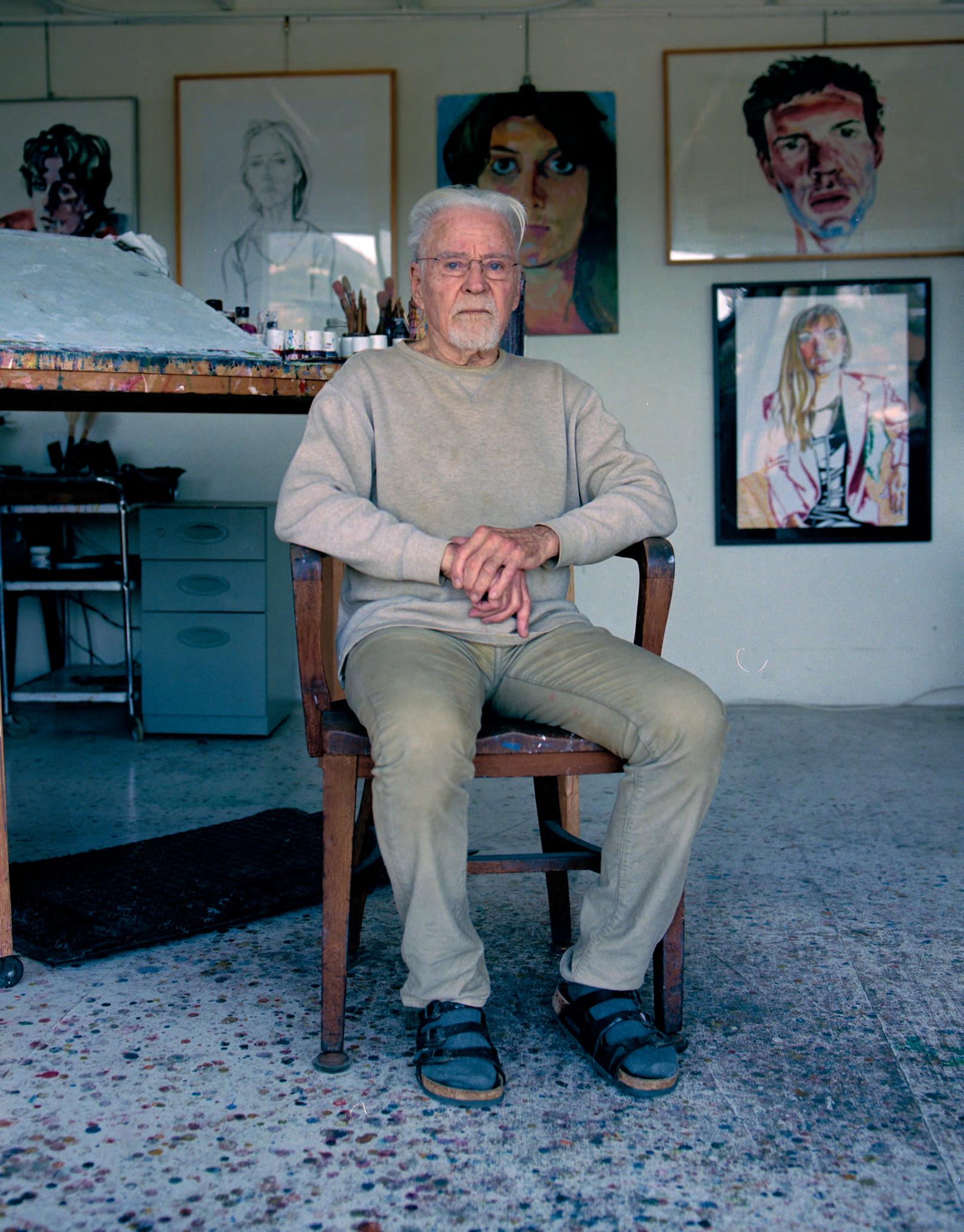

From Joan Didion to Bette Davis, Billy Al Bengston to Jerry Brown, Don Bachardy's subjects are a ‘Who's Who’ of California’s post-war cultural history. Jonathan Griffin meets the Santa Monica-based artist at home, to discuss his life and a career dedicated to capturing character through line.

Beyond the French windows in Don Bachardy’s Santa Monica portrait studio, a canyon studded with white-painted houses, palm trees, pines and eucalyptus tumbles down to the gleaming blue Pacific Ocean. It’s the kind of view that epitomizes visitors’ fantasies of Los Angeles, but which people who live here seldom get to enjoy firsthand, and certainly not on a daily basis.

Bachardy, now 88, has lived here on Adelaide Drive, on the upper border of Santa Monica, for most of his life. From his balcony you can glimpse the beach on which he first met the British writer Christopher Isherwood, on Valentine’s Day in 1952. Though Isherwood was 30 years his senior, they shortly after became a couple, and soon moved in together. In 1959 they bought this home. (Incidentally but perhaps auspiciously, they were not the canyon's only creative residents: the house next door was home to the artist-couple Luchita Hurtado and Lee Mullican)

Isherwood, who died in 1986, was respected in Britain but hardly famous; in the US, he was almost unknown at lea st until 2009, when his novel A Single Man (1964) was adapted for the screen by designer Tom Ford.

“I couldn't ever have become an artist without his backing,” Bachardy reflects. As an adolescent, Bachardy liked to copy the faces of movie stars from magazines. When they first met, Isherwood asked to see some and to Bachardy’s delight recognized every single one. Isherwood offered to sit for him.

“It was such a discovery for me!” says Bachardy. All the headshots he’d been drawing from, he realized, had been retouched to smooth out every crease and wrinkle. “It was so much more interesting a real face with all the lines!” When he showed the portrait to Isherwood, Bachardy remembers, there was a long pause. Isherwood was shocked: his young lover had drawn him to look even more

decrepit than his 48 years. “It’s good,” he eventually mustered, in a strangled tone. “After that I couldn’t work from a photograph ever again,” Bachardy says. “The experience of looking closely at a living face, a real face I got dr unk on it!” Isherwood, though never well off, paid for Bachardy to go to art school, at the Chouinard Art Institute near MacArthur Park. (Chouinard became CalArts when it moved to Valencia in 1970.) Bachardy was unbothered about getting his diploma, but he took every drawing class available. “Because I was so determined to succeed and make Chris proud of me, I did succeed,” he says. “It really made my life.” In recognition of the transformative potential of arts education, in 2017 the Christopher Isherwood Foundation established the Don Bachardy Fellowship, which sponsors a post-graduate artist from outside the UK to study for three months at the Royal Drawing School in London.

Though their age difference scandalized some, Bachardy and Isherwood were beloved figures in a cultural milieu composed largely of European émigrés. After Isherwood, Bachardy’s first sitter was the British-born historian and philosopher Gerald Heard, who had emigrated to the US in 1937 with his friend Aldous Huxley. The resulting portrait was acquired by another feted émigré to LA: Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, who settled in a house in West Hollywood in 1941.

All of these figures were friends of Isherwood long before Bachardy came on the scene. Doing portraits was a way for Bachardy to forge his own relationships with them, outside of the sometimes overbearing intellectual dominance of his partner. One of his proudest moments came in 1969 when the National Portrait Gallery in London acquired his pen drawing of W.H. Auden, one of Isherwood’s oldest friends, whose notoriously lined face was an ideal subject for Bachardy.

Bachardy’s incisive technique begins, and ends, with drawing. Until the 1980s, he rarely touched color, sticking to pencil, pen and ink wash on paper. Later, he developed a style of painting with vibrant strokes of water-based acrylic, although plenty of white still shows between the colored lines. Every formal decision is in service to speed and economy. Bachardy is painfully aware of how difficult it is to sit still for a portrait; he always positions sitters in his studio with a prime view of the ocean.

It is impossible to separate Bachardy the social being from Bachardy the artist. He was a fan as well as a friend to many of his sitters, who ranged from the anonymous to the world-famous. “If you’d told me that one day I’d have people like Bette Davis sitting for me!” he exclaims. He could be dispassionate too “bot h merciless and loving,” as Stephen Spender put it. When he drew Davis, then in her 60s, he pulled no punches. “She was a good sport,” he says, even if he sensed she didn’t like the drawings he did of her. (“There’s the old bag,” she commented when he showed her his drawing.)

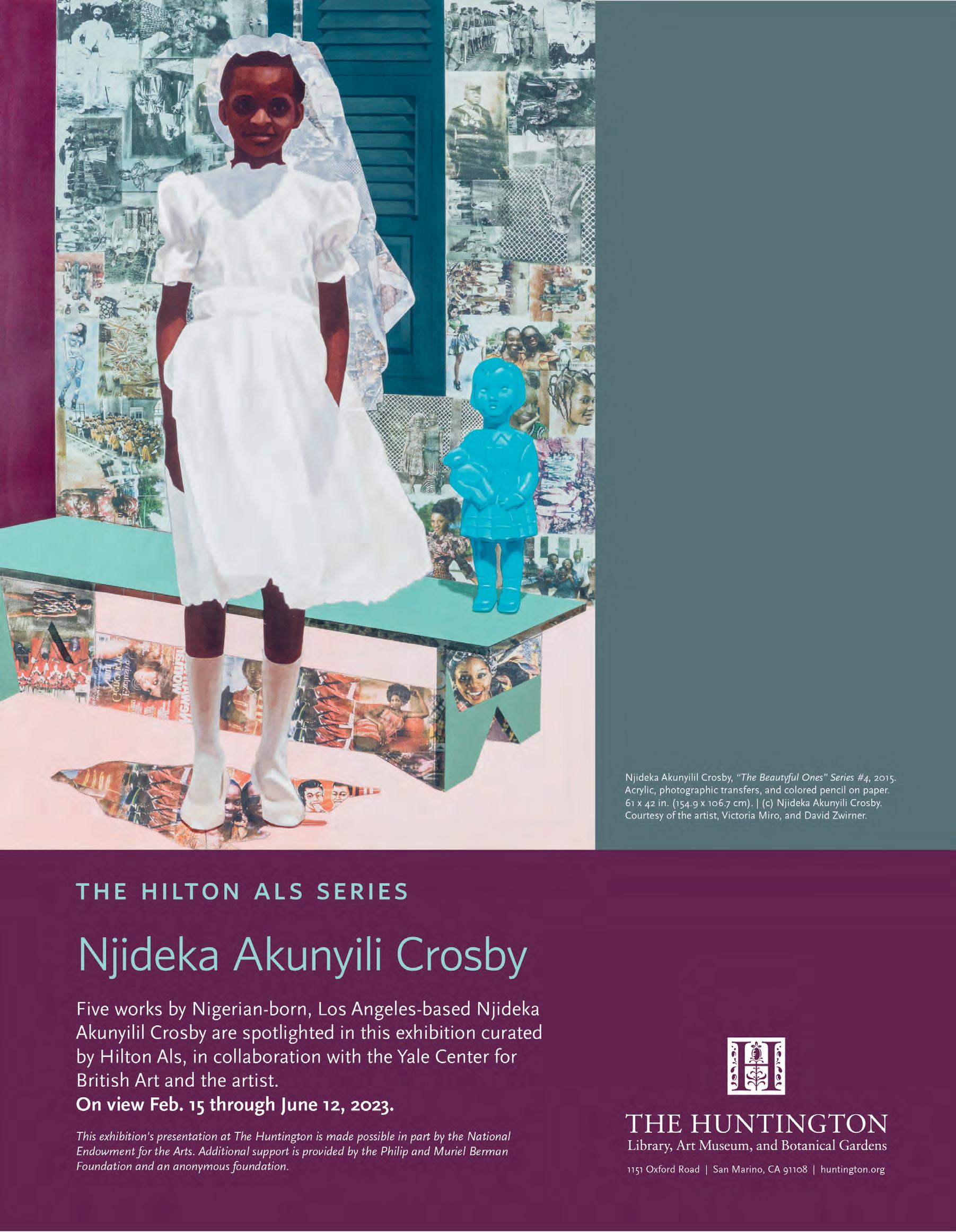

A 1972 portrait by Bachardy of the writer Joan Didion features in the recent, Hilton Als-curated exhibition “Joan Didion: What She Means”, at the Hammer Museum, LA. Following her screenplay for The Panic in Needle Park (1971), Didion was being fêted in Hollywood, but Bachardy’s picture shows her as girlish and pensive. Als, who owns the picture, describes it as “romantic without being sentimental because she’s romantic without being sentimental.”

When David Hockney moved to LA in 1964, Spender suggested he look up Isherwood. The young painter found he was much closer in age to Bachardy: the three became lifelong friends and Isherwood and Bachardy became two of Hockney’s most iconic subjects. Fascinated by the complicated dynamics

of their partnership, he often painted, drew or photographed them together. (In return, Hockney was an indelible influence on Bachardy’s work.)

On the walls of their home, artworks are hung from floor to ceiling, almost all gifts from friends. Paintings and prints by Billy Al Bengston, Jessie Homer French, Ken Price and Ed Ruscha nestle up against works less identifiable but equally significant to their owners. Few are figurative (Bachardy never hangs his own portraits in his home), with the major exception of the walls entirely given over to pictures by Hockney.

It’s moving to follow Bachardy from his living room, with its Saltillo tiles and wicker furniture, to a corridor in which Hockney’s photo-collage shows Bachardy and Isherwood sitting in that same furniture in 1983. “To Christopher + Don with much love and admiration,” runs the inscription. The work wid ely reproduced in books of Hockney’s collages is, i n this context, as sentimentally meaningful as Isherwood’s Repton School photograph from 1923, or the photograph of a grinning teenage Bachardy next to Marilyn Monroe, or a rare self-portrait by their friend Tennessee Williams, all of which hang in their kitchen.

When Bachardy dies, the house on Adelaide Drive will be preserved by the Santa Monica Conservancy, an assurance that gives him great satisfaction. It is a time capsule and ha s been, perhaps, since Isherwood’s death but it is also a living monument to love and to friendship, to a circle of luminous personalities who found community in this house over the ocean.

For 25 years, Santa Monica’s 18th Street Arts Center has proved itself ‘a force in LA for feminist, gay and performance art’, in the words of the pioneering artist Suzanne Lacy. A Resident Artist at 18th Street Arts Center, Lacy discusses her work there and beyond with the Getty Research Institute’s Glenn Phillips.

GLENN PHILLIPS

Suzanne, the first time we did an interview was in 2007 at 18th Street Arts Center where you and Leslie LabowitzStarus had installed “The Performing Archive”. You turned the archive into an installation and activated it by having people come in and use it. It was highly visual, interactive and a functional archive—all at once.

SUZANNE LACY

Leslie and I collaborated in the late 1970s on performances about violence against women. We wanted to look back at these issues, to look at the way performance art transforms over time, and we were also looking at understandings of gender in contemporary art. Then in 2007, we were discussing how feminist art was being rethought in terms of new theories and cultural understandings, including issues of race, poverty and so on. I thought it would be interesting to challenge received narratives in art discourse based on what you might actually find in a feminist artist’s archive. I wanted to foreground both the importance of archives for women’s work and direct access to archives as a learning tool. We invited 12 young women artists and scholars and said, “Go through the archive and see what ’s of interest to you.” I just videotaped them responding to what they selected. I didn’t correct them. I wanted to illuminate their process of discovery, their interpretations. We stuck the videos inbetween the boxes so visitors to the installation could see the archives, along with these young women trying to understand how we actually thought about the work.

GP 18th Street Arts Center was the venue. Could you talk about their openness to having projects like this?

SL 18th Street has been a force in LA for feminist, gay and performance art. They’ve been crucial for so many areas of social, political, exploratory and avantgarde kinds of thinking. And of course, it’s been a residency for artists from all over the world. I don’t remember when 18th Street came into my consciousness; it was always part of the LA performance scene.

GP One of the more remarkable developments in your career is the way you’ve used your archive to create these extraordinary, spatially complex installations. It really struck me in your recent retrospective at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the way your projects unfold over time and space. But you have many other kinds of space that are important to you. One of them is social space and how people understand the issues you confront in our present moment. Another is the

media space, and how public communication happens around these same issues, whether that be television in the 1970s or social media today.

SL My work is idea driven and hard to pin down as a singular aesthetic form. It’s very visual, but it’s also informed by the context in which it operates, the social issues and how they align with my own values. Exhibitions of temporal works have changed too. In the 1970s we thumbtacked photographs on the wall and considered that as an effective way to communicate a performance produced earlier. Each time we exhibited, we configured the work to fit the space we had. But now it’s important to create a “final” version, an artwork that represents the nature and context of the original work, one that responds to current technologies and ideas, where you can say: this is that work.

GP When performance enters the museum in its “final form”, it often matches the era in which the museum acquires it. In the era of big photography, for instance, people started blowing up their documentation to match. I think performance has no choice but to react to the era it’s in.

SL I agree that once a work’s acquired, you should probably leave it the way it is. But just because a piece was shown on a small television in the 1970s doesn’t mean it can’t be a large projection now. It’s my work. While I’m alive, I can show it the way I want. That’s the malleability of contextual and timebased art.

GP That c an be a challenging idea for museum professionals. The acquisitions side of me never wants to see a piece change. But the exhibitions side of me—well that’s a different story because you want to do the very best show possible, even if that means breaking some rules. And your work is always a prompt for people to engage with an idea. If that’s the ambition, then it needs to be presented in a way that can get that idea across to the viewer.

SL Right. What draws me to art is the idea. In “The Performing Archive” Leslie and I were exploring very current ideas about art and social context. As I’ve been focusing on exhibitions lately, I’m hauling projects out of my archives and considering how I might finally represent them. Like Cinderella in a Dragster, a performance I did in 1976. Maybe I need to build a hot rod? What will be its final form?

Glenn Phillips is Senior Curator, Head of Exhibitions and Head of Modern & Contemporary Collections at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. He lives in Los Angeles, USA.

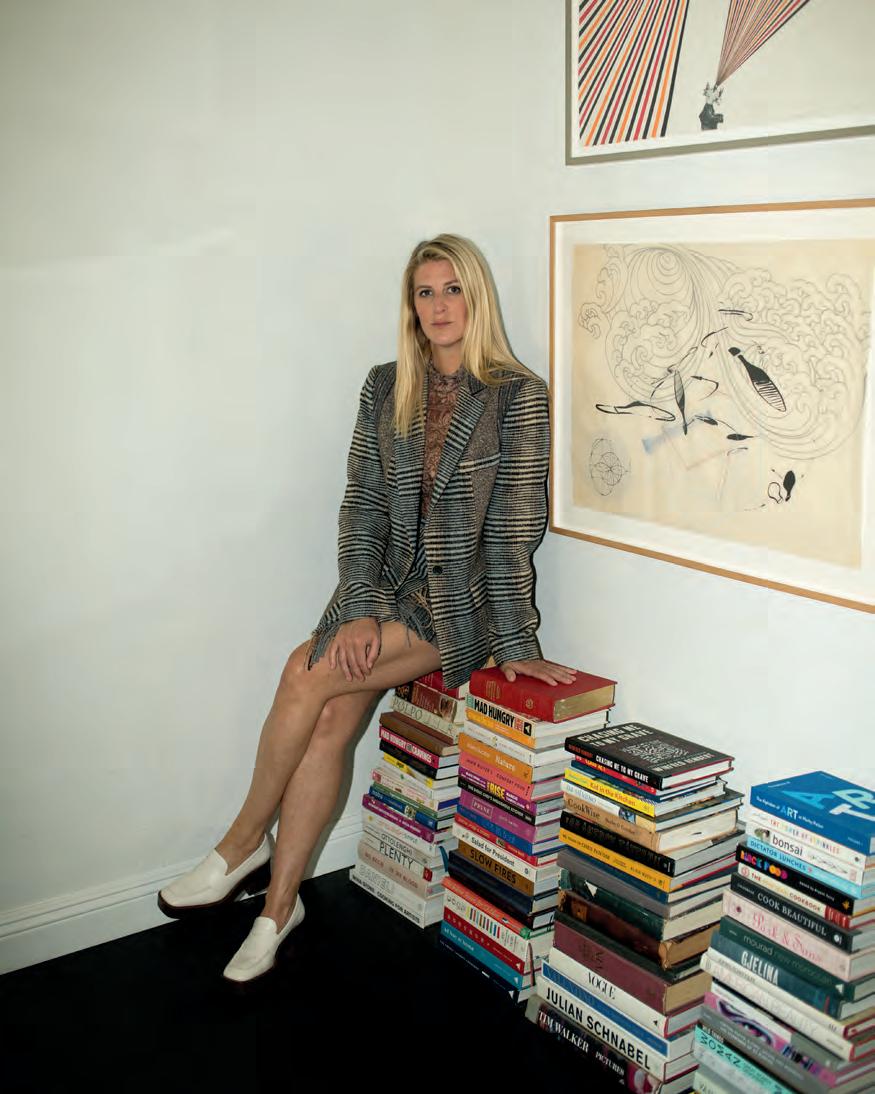

Transforming a guest room into an place for exhibition-making, Santa Monica’s Del Vaz Projects is dedicated to exploring the relationship between art and the domestic space. Travis Diehl profiles its founder, Jay Ezra Nayssan, as he embarks on a project that animates sites across Frieze Los Angeles’s new neighborhood.

Opposite Jay Ezra Nayssan at Del Vaz Projects, Santa Monica, November 2022

Browse the wares in the Del Vaz Projects gift shop or, as they have it, the apothecary and what do you find? Among artist editions, like linen tablecloths by Piero Golia and reef-friendly sunscreen by Amy Yao, are jars of sauerkraut from cabbages grown on site, fresh eggs from Del Vaz’s resident flocks of ornamental ducks and fancy chickens; bowls from Andrea Zittel’s famous A-Z West outpost in Joshua Tree, and apple cider vinegar from Salmon Creek Farm, the vintage commune bought and restored by Fritz Haeg.

What unites these offerings is an ethos; not just household goods or domestic design, they are the produce of other experiments in artistic living evidence of a network of artists and curators with ties to Los Angeles, trying to build the art world they want to see, starting at home.

Indeed, home is where Del Vaz began. In 2014, curator Jay Ezra Nayssan had organized a handful of exhibitions and was learning the art of the deal when the venue for a planned group show, including the works of Max Hooper Schneider and Liz Craft, fell through. But Nayssan had a spare bedroom and Craft had an idea: Nayssan should host the show there, like he would a houseguest. The opening featured a harpist in the living room and trays of desserts in the kitchen.

Craft also told Nayssan to commit the e xhibition should be the first of many, in a program with an official name. Eight years later, he has moved twice, and Del Vaz Projects, named after a Farsi phrase of welcome, is now in its third spare room, having hosted more than 20 exhibitions.

There in the Sawtelle neighborhood of LA, Nayssan tapped into a Westside tradition. Curator Emma Gray started Five Car

Garage in Santa Monica in 2013, on the heels of the project space Paradise Garage, which Craft and fellow artist Pentti Monkkonen had opened off the alley by their Venice home in 2012. When Paradise Garage closed in 2015 dramatically collapsing in an action by artist Oscar Tuazon entitled This Won’t Take Long it broke a link in the history of Venice salons, which extends back to the 1960s and encompasses those of Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Huguette Caland, Fred Eversley, Robert Irwin and Ed Ruscha.

For “Against the Edge”, a series of artist interventions curated for Frieze Projects on the occasion of Frieze Los Angeles 2023, Nayssan looked to some deeper, darker periods of the city’s history. In the 1940s, while war consumed the Old World, European emigrés-in-exile, from Theodor Adorno to Aldous Huxley to Arnold Schoenberg, resettled in and around Santa Monica. Nayssan has sought out key historic sites in the area, which he plans to activate with contemporary art. Among these, the Thomas Mann house stands out for its style: the German novelist toured the modern architecture of the region with Richard Neutra before commissioning a new residence by Julius Ralph Davidson. A year later, the GermanJewish author Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife Marta moved into Villa Aurora, a crumbling Spanish-style chateau. With help from their friends and neighbors, they gradually restored the building until it, too, became a grand gathering place for the era’s restless minds.

At Del Vaz Projects itself, Nayssan will host an exhibition of work by a no-less restless force: the late Julie Becker. Her work mined some of the darker psychic

and political aspects of domestic real estate: the show’s title, “(W)hole”, refers to Becker’s ambitious project Whole, which she began in 1999 in a rent-free basement apartment she had been granted in return for clearing the belongings of its last inhabitant, who died of AIDS; it remained unfinished at the time of her own death in 2016.

A talk on Becker’s work with Ralph Coon and Chris Kraus is planned to take place in the garden of Del Vaz Projects’ current location: a Santa Monica property where, apparently, Shirley Temple grew up. As in 2014, Hooper Schneider inaugurated the new exhibition space a room off the courtyard with a coffin-like sculpture incubating the ducks’ eggs.

Nayssan lives at Del Vaz Projects with his partner, Dr. Max Goldstein, but also with the art, which spills into the common spaces even when there aren’t openings and visitors. There’s a mural in the greenhouse by artist Patricia Iglesias Peco, next to the pens of birds in the yard. There’s a residency program, hosting artists from all over, like members of K-HOLE, Olivia Erlanger and Alicia Adamerovich. Del Vaz Projects has traveled, too to brick-and-mortar galleries in Los Angeles and apartments in Paris.

I asked Nayssan if, in the course of his moves, he’d considered finding Del Vaz a more traditional building, separated from the mix of his daily life mirroring the way that other apartment spaces served as stepping stones to the real thing. The thought has occurred to him, but he doesn’t think he will. The Santa Monica house is a step up, as far as it goes freestanding, spacious, with architectural details like Spanish tiles and a fountain.

And while the operation has upgraded and professionalized, as going concerns should Del Va z has stayed at home. There’s a way the apartment or house or domestic space feels malleable to Nayssan. The exhibition is not just some paintings and sculptures shoved into a spare room, but artwork taking place. It’s a generous project, founded on a dynamic of host and guest that couldn’t work any other way. There are house galleries on the Eastside, too and in Berlin, New York and Mexico City, for that matter but they’re a little different to what LA’s Westside offers. Del Vaz Projects has always had an open, inviting feeling, a sense that the exhibition isn’t in someone’s house out of necessity: not a lack of space, but an abundance of it.

‘The art spills into the common spaces, even when there aren’t openings and visitors. There’s a mural in the greenhouse, next to the pens of birds in the yard.’

Curated by Jay Ezra Nayssan as part of Frieze Projects, “Against the Edge” brings the work of contemporary artists into dialogue with cultural sites across the Westside, unearthing narratives of liberation and creativity as well as exile and occlusion. But, as Nayssan explains, he’s less interested in rehashing history than in teasing new stories out of it. Find out more about the program on frieze.com. Illustrations: LILKOOL

“Ever since Del Vaz Projects moved to Santa Monica in 2020, I’ve been thinking of a program that would put contemporary art into a dialogue with the historic homes in this area. For ‘Against the Edge’, I have drawn on Norman Klein’s History of Forgetting [1997], in which he uses the idea of the ‘anti-tour’ of places that don’t or no longer exist. I’m interested in Klein as a guide to a kind of style: both as an author and a teacher at CalArts, Klein practiced a form of storytelling in which history and possible fictions merge into this kind of mythmaking, for which he uses the psychological term ‘imago’. ‘Against the Edge’ only features sites that still physically exist, however, and even if some of their histories have been ‘forgotten’, there is active effort in keeping them alive.

So, the purpose of bringing these artists into relation with these sites is to create new stories that, like Klein’s narrative, live somewhere between fiction and fact. For example, bringing the work of Kelly Akashi, as the daughter of imprisoned Japanese-Americans, into the home of the Feuchtwangers: exiled Jews escaping death camps. Did Isamu Noguchi, who electively selfinterned in the Japanese-American camps, and in 1951 had a tea ceremony at the Eames House a short drive away, ever meet the Feuchtwangers and their circle? Nicola L. didn’t really live in LA until she was close to passing away, but using her work to queer the Thomas Mann House, also raises a kind of ‘what if ... ’. Thus, the program is about weaving these new, partly fictionalized stories, out of the record.

We are staging a performance in the Santa Monica Pier’s Merry-Go-Round Building to, in a way, kick off the ‘Against the Edge’ program. This building was the site of the first proper exhibition Walter Hopps curated, ‘Action 1’, in 1954. Hopps covered the carousel in tarp and hung art from it: a kind of inverted anticipation of the rotunda of Guggenheim, where he would later make major exhibitions. Was it almost a premonition?

The piece we are staging is John Cage’s Speech [1955], which formed part of ‘Action 1’, and is scored for five radios, each tuned to different stations. Operators shifting the radio dials, creating an unorganized, unthreaded sound event. Again, it’s about that disjunctive overlap of sources, that mingling of real information and partial accounts, that produces an imago of the city.”

Built in 1906, the former Venice City Hall has since 1980 been home to Beyond Baroque. Emerging from the Venice Beat scene as an experimental zine run from a storefront by founder George Drury Smith, Beyond Baroque has evolved into a leading literary arts organisation, providing workshops, readings, film screenings, a publishing imprint and a specialist bookstore boasting 40,000 volumes, including rare and small press publications. It has hosted everything from early Mike Kelley performances to readings by Amanda Gorman, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Flanagan, Amiri Baraka and countless more.

“Presenting Tony Cokes’s work here is about building upon the legacy of Beyond Baroque as a beacon for beat poetry and punk. The musicality and rhythm of Cokes’s work, and its connection to

vernacular forms of music and spoken word, will resonate in Beyond Baroque’s theatre.

The initial reason I wanted to include Cokes in the program was because of a series of video works he showed a few years ago at Hannah Hoffman that reflected on the legacy of Paul Revere Williams: a Black architect who helped design Black neighborhoods in Los Angeles, like Pueblo del Rio, as well as commissions for Hollywood stars. I wanted to acknowledge the fate of nearby Black communities like the Belmar Neighborhood, which the City of Santa Monica literally set on fire in 1950 to make way for development, and the Oakwood community in Venice Beach, the only remaining Black community in Southern California within a mile of the beach, which has also been threatened by development.

But actually, we’re not showing those works about Williams, but instead, a more recent commission that explores the relationship between art and real estate through the 1988 Tompkins Square Park Riot, a piece paying homage to Okwui Enwezor, and a piece about the labor of mourning. I wanted to do something that wasn’t the expected thing. That desire runs throughout the program: working with perhaps not iconically ‘LA artists’, and homes that people are not necessarily familiar with, creating a sense of displacement. I want to speak to the unease of this place as a paradise. When the playwright Bertolt Brecht moved to Santa Monica in the 1940s, he complained that it was too beautiful to make any work here. I want ‘Against the Edge’ to convey some of that disquiet.”

With his wife Katia and children, the Nobel Prize-winning author Thomas Mann moved to Los Angeles via Princeton in 1941, having fled Nazism in his home country. Before commissioning his new home in Santa Monica, Mann toured California modernist buildings in 1938 with Richard Neutra, ultimately selecting the Berlin-born, German-Jewish architect Julius Ralph Davidson, who designed some of the first Case Study Houses. The Manns stayed at the house until 1952, Thomas writing his two last novels here, before McCarthyism drove them back to Europe. Since 2016, it has been a residency centre.

“There are few threads that come together in presenting Nicola L.’s work at the Thomas Mann House. Because Nicola L.’s work often brought sexuality to the fore—with her penetrable, vinyl

sculptures pointing to the erotic body, and the fetish—one is about queering the space, to speak to Mann’s own complex, closeted homosexuality, which is still very controversial. You find an echo of this in the clear contrast between the house’s California modernist ‘outside’ and its interior, which the Manns furnished in a very traditional, bourgeois, Central European style that really offended the house’s architect.

Nicola L.’s work was also confronting modern architecture as a male-driven language driven by a hegemony of vision, and its almost sterile lack of the sensual (think of how Le Corbusier or Adolf Loos placed sinks right at the entrance of certain villas, demanding you to wash your hands). Nicola L. really rubbed against this, her art pointing to an architecture of sensuality

and of community, works that could be felt and smelt and heard.

The work we’re installing at the House is one of Nicola L.’s fabric banners, which she first produced for the 1968 Student Revolt in Paris. It proclaims Nous Voulons Entendre, or ‘We Want to Hear’, but the verb ‘entendre’ can also mean ‘to sound’, or ‘to understand’, which interests me.

As well as highlighting the sensory in relation to modernism, this slogan and its political context connects to a different moment of protest: the anti-fascist radio broadcasts which Thomas Mann recorded in his office in this house, broadcast by the BBC broadcast to Nazi Germany from 1940—43. Radio transmission also brings us back to the John Cage staged on the Pier.”

The ‘demonstration house’ for the planned Miramar Estates, the Spanish-style Villa Aurora was completed in 1928, with luxury features like electric garage doors and a pipe organ to accompany movie screenings. Following the Wall Street Crash, it failed to sell and fell vacant in 1939. In 1943, it was acquired by Lion Feuchtwanger, author of Jew Süß (1925) and his wife, Marta. With Salka and Berthold Viertel’s nearby home, the Villa became a meeting point for émigrés like Bertolt Brecht, Alma Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg. After Lion Feuchtwanger’s death in 1995, it became a residency for artists.

“Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger arrived in Los Angeles in 1941. They bought this place in 1943. It cost $9,000, which was a small sum even then. In Marta’s oral history, the house was so run-down

that the couple had to spend the first night in sleeping bags in the garden.

By placing Kelly Akashi’s work here, I wanted to explore the fact that just a few months after the Feuchtwangers arrived here with all their support, Executive Order 9066 was issued, forcing Japanese-Americans into internment camps. So almost the same fate the Feuchtwanglers were escaping in Europe was happening in their ref uge. Many of the Japanese-Americans interned were from Santa Monica and Venice. Akashi’s own father and grandparents had to leave Boyle Heights to be interned at Poston Internment Camp in Arizona.

There’s this overarching narrative that is emerging with the work at Del Vaz that connects here. With shows like ‘Shell’ with Heidi Bucher

(who installed her “Bodyshells” sculptures on Venice Beach in 1972), and others. I was really looking at the protective nature of the shelter, whereas now I want to look at the precarity of place and space and shelter. The work by Julie Becker that will be shown at Del Vaz as part of the program really speaks to this idea too of the precarity, or faultiness, of the “home” in Los Angeles. I think ‘faultiness’ is a good word to use for this idea in LA, where we are literally on a fault line.”

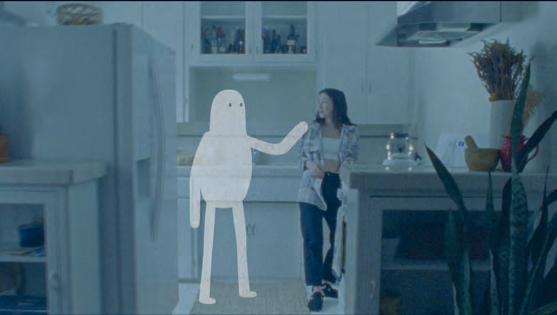

It was during the summer of 2020 that film writer and director Jane Chow was scrolling through the resources at Free the Work, film director Alma Har’el’s talent discovery platform. After a year spent directing commercials and music videos, Chow was eager for opportunities that would allow her to reprioritize her own narrative projects, and her attention was caught by a call for entries for the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award. While Chow had never applied for this kind of program before, she was drawn to the Fellowship’s emphasis on professional mentorship and creative support alongside the development of a 3–4 minute short film. “Honestly, I couldn’t have asked for a better first program,” says Chow.

Launched in 2019 to coincide with the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles and driven by a commitment to inclusivity, the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award brings together ten shortlisted Fellows to participate in a four-month intensive filmmaking course led by the award-winning, nonprofit Ghetto Film School (GFS), with support from the production company FIFTH SEASON (formerly Endeavor Content). Guided by a thematic prompt, the Fellows develop their projects while learning about the ins and outs of film production from guest speakers representing all facets of the industry, whether cinematographers, writers, producers or executives. The Fellowship ends with a ceremony for the Fellows and their films during Frieze Week, and the announcement of the US$10,000 prizewinner, picked by a jury of esteemed artists and cultural workers. In the past, jurors have included internationally renowned curators Christine Y. Kim and Hamza Walker, acclaimed artist Kehinde Wiley and producer Alana Mayo, a long-time collaborator with Michael B. Jordan and now head of Orion Pictures, which oversaw Billy Porter’s directorial debut.

Brooklyn-born Timothy Offor participated in the first iteration of the Fellowship, applying on a whim following the recommendation of a friend. Like Chow, he viewed it as an opportunity for a change of pace from the freelance grind, where he took on editing and directing gigs, amongst other things. In addition to the sessions at art institutions like the Hammer Museum and the Underground Museum, Offor says he appreciated the

investment in their professional development, noting the program’s practice of taking headshots of the Fellows and setting up interviews about their art. He also points to his cohort’s collaborative nature: “Yeah it’s a competition, but a lot of us ended up helping each other and advising [on each other’s projects].”

Offor’s own generous spirit caught the attention of GFS, and after he left the program, he was asked to join the company as a consultant, with a particular focus on running the Fellowship. He joined in the second year, which coincided with the award’s new partnership with Endeavor Content (now FIFTH SEASON). With their support, alongside GFS, Offor made the curriculum more filmmakercentric, tapping into Endeavor’s wide network. “We wanted the sessions to reflect the filmmaking process,” he explains.

“By the time those four weeks are over, you’re ready to shoot your project.” The Fellowship also aims to prepare the participants for the future, with presentations by agents and representatives. Chow cites a ta lk with writer and director Rashaad Ernesto Green as a highlight. “I remember that conversation being so affirming. He’s a multi-hyphenate too, a writer and

To watch all the films by the 2023 Fellows of the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award, in partnership with Ghetto Film School and FIFTH SEASON, and discover the winners, go to: frieze.com/ DB-Frieze-LA-FilmAward

director who works in both film and TV,” she says. “When you’re able to hear about other people’s career trajectories, you start to see the possibilities for yourself as well.” After running other GFS programs with brands like Neutrogena and Netflix, Offor is taking time to focus on his own projects. “It has been great helping filmmakers. But ultimately I need to make movies. That’s what my goal is.”

Diante Singley, a Fellow from the third year of the program, came across the award through a friend who had participated in the second year. Working as a creative executive by day, he says the Fellowship allowed him the space to “get back to basics.” It also afforded him the chance to build new connections with his peers and colleagues. “You meet these phenomenal people who you aspire to be, and you see what got them to where they are.” Although Singley went into it with modest expectations, his impressionistic film Greyhound (2022), which follows a young Black man’s encounters with his community and loved ones before leaving for college, ended up winning the coveted prize. “It felt very beautiful to be in a room and have people look at you like a filmmaker.” Since winning, it’s been

heartening to have people reach out to him as a creative, rather than an executive, Singley says.

Chow’s life has also shifted since the Fellowship. Her film, Sorry for the Inconvenience (2021), a stirring ode to Chinatown, centers on a teen helping her parents run their seafood restaurant during the COVID-19 pandemic. After it won the inaugural Audience Award, which is voted for by general viewers alongside the jury-decided Award, Chow decided to keep up the momentum, releasing the short film on platforms like Omeleto and NoBudge. That led to the piece being chosen for NBCUniversal’s “Scene in Color Film Series”, sponsored by Ta rget. She is now at work on an original pilot script for NBCUniversal. “Even though the Fellowship was in 2020 and early 2021, opportunities keep coming from this short film. It’s been a really exciting process.”

Since its launch in 2019, the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award has been offering a development program to aspiring and emerging LA-based filmmakers. Presented in collaboration with Ghetto Film School and FIFTH SEASON, the initiative offers support to young artists, engaging with the local community and celebrating the creativity and unique culture of Los Angeles.

To discover more about the Award, visit www.frieze.com/DB-Frieze-LA-Film-Award

Ruben Ochoa’s practice interrogates the construction and experience of public space around Los Angeles. For Frieze Projects, he undertakes a multilayered celebration of the local street food vendors: a community that is an essential part of the city’s culinary story, as Patricia Escárcega finds.

In 2001, Ruben Ochoa, then a graduate art student at University of California, Irvine, found himself in possession of a barelyfunctioning 1985 Chevy van. In its former life, the hand-me-down vehicle, part of a small fleet of delivery vehicles owned by his parents, was used to transport bulk orders of tortillas, chicharrón, nopales and other Mexican food products, to homes and far-flung ranchos across north San Diego County.

“My mother pioneered an extensive door-to-door tortilla route in the 1970s. This was before there were Mexican markets on every other corner,” says Ochoa, a native of Oceanside, California. “It was essentially a mobile mercado on wheels.”

Ochoa, who moved to LA in the 1990s to attend art school, repurposed the van into a mobile art space and curatorial project called CLASS: C. From 2001 to 2005, the van retrofitted with a small office, gallery space, track lighting and storage area showcased works by more than 75 artists across Southern California, many of them emerging artists of color. The art-van made visits to lowrider shows, the Rose Bowl Flea Market and local dive bars, as well as more traditional venues, including an exhibition at the Orange County Museum of Art’s 2004 California Biennial. “Every stop was like an opening,” he recalls, fondly.

As part of the Frieze Projects program at Frieze Los Angeles, Ochoa is resurrecting the CLASS: C van, exhibiting “Las Tortillas”, a series of bronze tortilla sculptures that pay homage to both the food and his family’s history as tortilla purveyors. In parallel, working in partnership with the fair, Revolution Carts maker of the first

hot-food vending cart approved by the LA County Department of Health and local street vendor advocacy groups, Ochoa will design the graphics for a custom “streetlegal” food vending cart, which will be unveiled and donated to a local vendor at the fair. As well as directly benefitting this community, the gesture is intended to raise awareness of the history, contributions and ongoing “hustle” of Los Angeles’ street vendors, whose economic and cultural impact on the city is, Ochoa says, unrecognized and undervalued.

Street vending has been a central feature of LA food culture and commerce since the late 19th-century, when Mexican and Chinese immigrant vendors selling tamales, vegetables and fruit traversed the city on wagons and bicycles. Many beloved and emblematic LA dishes tacos, burritos, hamburgers and bacon-wrapped hot dogs, among others are rooted in the city’s street-food culture. Yet the history of street vending in LA has been one of political disenfranchisement and intense criminalization. There are an estimated 10,000 street vendors in the city many undocumented workers, women or elderly and they risk harassment, robbery and assault every time they go to work.

(According to the nonprofit newsroom Crosstown, the number of reported crimes against LA street vendors rose nearly 337 percent between 2010 and 2019.) The Safe Sidewalk Vending Act (2018) decriminalized vending in the city, but failed to create a pathway for people to obtain vending licenses. The COVID-19 pandemic, which summarily shut down all street vending operations in the city for months, further derailed the progress toward

legalization. However, street vendors and advocacy groups are optimistic about the newly passed California State Bill 972, which takes effect in January 2023, and aims to reduce many of the financial and bureaucratic restrictions that have kept thousands of vendors at the margins of the city’s street economy.

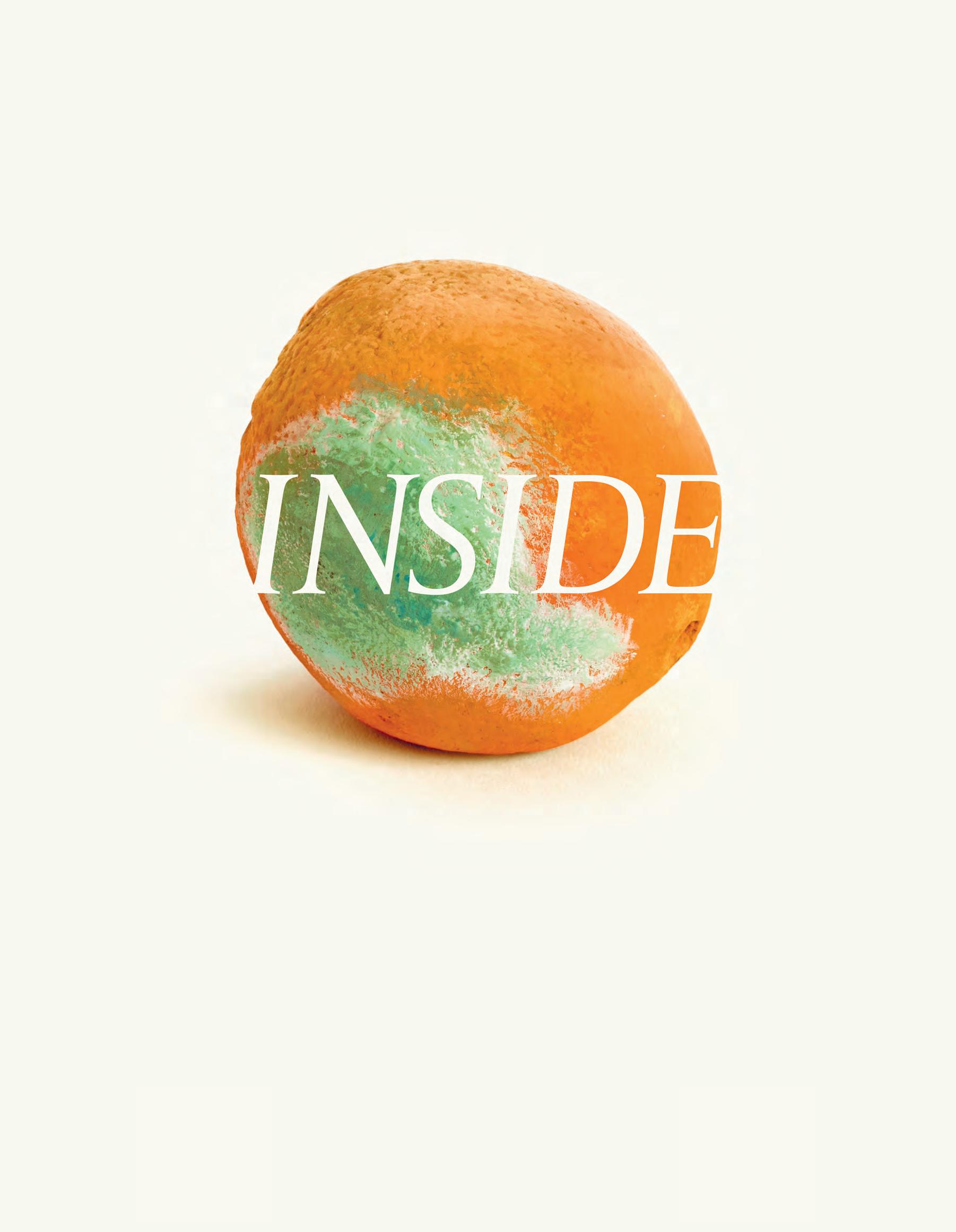

Some of these issues were foregrounded in Ochoa’s most recent work, part of a project by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and Snapchat, which invited artists to reimagine monuments through augmented reality technology. For Ochoa’s ¡Vendedores, Presente! (2021) the artist designed a Snapchat geolocated to MacArthur Park, a site with a long and contentious history of street vending. (It is also a nod to the former location of the Otis College of Fine Arts, where Ochoa went to school.) The work forayed into a distinctly LA-style magical realism: a swarm of flying fruit-vendor carts, festooned with their instantly recognizable rainbow umbrellas, hover over MacArthur Park Lake; a boulder-sized orange bounces and ricochets across the park; while on the horizon, a heroic, rocket-propelled elotero showers the city with steam-tendered corn kernels.

It was not the first time that Ochoa’s work interrogated and reimagined the cultural, economic and racial divisions that characterize “public space” across the built and natural environments of LA. In Fwy Wall Extraction (2006), for example, Ochoa camouflaged the 60-foot-tall retaining wall of a freeway using a massive trompe l’oeil photomural depicting rugged green space. The portion of freeway “extracted” runs along the infamously knotty

East Los Angeles interchange, a site where multiple high-speed roadways converge. Ochoa’s intervention gestured to the history of the site: the junction among t he busiest in the world had ripped apart the working-class neighborhood of Boyle Heights in the 1950s and ’60s, displacing thousands, and resulting in long-term environmental and health issues for residents. This fundamental concern with space, access and movement, and the way these can shape, control and marginalize people and natural environments, underpins Ochoa’s work. Industrial materials frequently function as signifiers of “the hidden and invisible labor” of Southern California’s built environments, as well as references to his own working-class roots and family history. (Several members, including Ochoa’s father, are skilled in construction, and Ochoa has collaborated with them in the past on his sculptures; the artist also credits his partner, Cam La, as his “mano derecha ”, or right hand, in the production of many of his works.)

Ochoa’s interventions at Frieze could be understood as efforts to make one form of these hidden labors the st reet vendors’ hustle more vi sible: creating a lens to a vision of a bubblier, brighter LA, where street vendors are not perceived as a public nuisance, but as a source of energy, community and joy.

Destination Street Food

Street vendors are in many ways the lifeblood of LA’s food culture, which has earned a reputation around the world as one of the most diverse and exciting places to eat. Here are five places to sample the breadth of the city’s street food scene.

Please note that due to the nature of street vending, location and hours are subject to change without notice.

1. Corn Man

2338 Workman St, 90031

Hours: Open most nights, 11.15pm – c. 3a m Los Angeles has no shortage of elote vendors, but this venerable late-night Lincoln Heights stand, situated in a rather poorly-lit parking lot, distinguishes itself from the pack with consistently friendly service, and some of the juiciest, most decadent elote and esquites creations in the city. Whether you order elote (corn on the cob) or esquites (fresh corn kernels served in a bowl), it will come doused in lavish amounts of mayonnaise, butter and Parmesan cheese. Chili powder and lime are optional, but highly recommended, as these help temper the snack’s unctuous decadence. Prepare to eat late: the Corn Man, a local legend who is known as Timoteo to regulars, arrives after 11pm and pac ks up around 3am or whenever the corn sells out.

2. Alejandra’s Quesadilla Cart de Oaxaca

1246 Echo Park Ave, 90026

Hours: Open most Fridays, Saturdays and Mondays, 11.30am – 6.30 pm

Tucked inside a parking lot near the corner of Echo Park and Sunset Boulevard, this popular cart specializes in sturdy, griddle-crisped blue corn quesadillas stuffed with two or three meals’ worth of cheese-smothered meats and vegetables. There is not a whiff of mediocrity on the spartan menu, which offers six options: chicharrón, featuring crisp pork skins; huitlacoche, the earthy, jet-black corn fungus spackled with stretchy Oaxacan cheese; buttery flor de calabaza (squash blossoms); hongos (mushrooms); papas con chorizo (potatoes and chorizo); and chili-rubbed shredded chicken. Complimentary pickled nopales (cactus) and salsas (spicy red and medium-spicy green) are excellent and plentiful.

3. Night Market El Gato

941 S Un ion Ave, 90015

Hours: Open on Fridays, 5pm – 12a m; Saturdays and Sundays, 3pm – 11pm

Among the current spate of night markets, El Gato, which pops up in the Westlake neighborhood on the majority of weekends, is among the most likely to make an appearance on your teenager’s TikTok feed. The line-up of vendors is constantly changing, but the market has quickly earned a reputation for excellent skewered meats, barbecue and trendy Mexican-fusion street foods (carne asada pizza and chili-smattered potato twists, anyone?). Traditionalists will appreciate the strong showing of offal-stuffed tacos and agua frescas; everyone else will appreciate the market’s youthful vibe, the relatively easy parking and the wide selection of syrupy, novelty desserts, which on a recent visit included penis-shaped pancakes.

4. Tacos El Chido 6840 Santa Mon ica Blvd, 90038

Hours: Open Monday – Wed nesday, 6pm – 1am; Thursday – Sat urday, 6pm – 3am L A street vendors have raised the bar for late-night feasting. A case in point is Tacos El Chido, a spacious and friendly taco stand that pops up on most evenings next door to a gas station in Hollywood. The meat selection is comprehensive, encompassing the canonical (carne asada , pollo and al pastor), along with slightly harder-to-find offal, including lengua (beef tongue), tripas (cow tripe) and buche (pork stomach). Meats are generously ladled onto sturdy, handmade corn tortillas, and topped to your specifications. It would be a mistake to leave without at least trying the al pastor, sliced to order from the always-turning trompo and pollo (grilled chicken), which tastes as if it is fresh from a backyard grill.

5. Guatemalan Night Market 1834 – 1898 W 6th St, 90057

Hours: Open seven days a week, 5pm – 12a m

The scent of grilled meats permeates the air near the intersection of Bonnie Brae and Sixth Street in Westlake’s Little Central America, where a motley assemblage of vendors, families and teenagers crowd the sidewalks every evening. Much of the allure of this singular market is the opportunity to savor regional specialities that can be hard to find outside Guatemala. Charcoal-grilled beef, pork ribs and chicken served with beans and macaroni salad are staples, as are banana-wrapped paches (potato tamales), tostadas heaped with crumbly picadillo and fried-to-order pollo y papas fritas (fried chicken and French fries), drizzled with mayonnaise, ketchup and salsa.

- Patricia EscárcegaUkrainian expression under threat of cultural annihilation

“MOMA’s attempts last century to educate Americans about the dangers of fascism are echoed today by Sonya: A Sunflower Network Project.”

- The Village Voice

- The Village Voice

Art Production Fund has enabled some of the most instantly recognizable public artworks of recent times, in sites from West Hollywood to West Texas. A New Yorker now based in Los Angeles, its Executive Director Casey Fremont is spearheading multiple projects at Frieze Los Angeles 2023.

Bringing art outside museums, private collections and galleries, and often, quite simply, outside: that’s the mission of the nonprofit organization Art Production Fund (APF). Founded by Yvonne Force Villareal and Doreen Remen in New York in 2000, for more than two decades APF has been bringing big, bold and strikingly recognizable public art to life. Think of Zoe Buckman’s Champ (2018–19), a four-story-high neon uterus with boxing gloves for ovaries, that loomed above the Standard Hotel in West Hollywood. The artist’s first major public work has a fresh poignancy among a new wave of assaults on women’s reproductive rights.

“The goal is always for it to be standalone within a public space,” explains Casey Fremont, Art Production Fund’s current Executive Director. Speaking from her new home in Beverly Hills, she underscores the APF’s commitment to making artwork truly accessible to a diverse public. “We gravitate toward projects that are accessible on many different levels to many different people, and that don’t require an art-historical background.”

She cites Ugo Rondinone’s Seven Magic Mountains (2016–), precarious towering stacks of fluorescent-hued rocks in the endless desert a few miles south of the Las Vegas Strip, as an example. “When you see Seven Magic Mountains in person, you view the surrounding natural landscape in a whole different way. Anyone can experience that.”

Though she grew up immersed in the art world—“My dad worked for Andy Warhol and my mother worked in galleries, so I was always exposed to art and artists,” she notes—Fremont was not always a passionate lover of art. “I resisted art and going to museums—I hated that my parents dragged me.” It was only when Fremont got older, she notes, laughing, “I learned that I actually did like art. I wasn’t as rebellious as I thought I was!”

Fremont began her story at APF as a summer intern while she was a student in Boston, joining as a full-time staff member in 2004. “I loved what Doreen and Yvonne were doing, and I loved work ing with them. It was really a dream job. The timing aligned perfectly—they were hiring someone, and I graduated college a year early and was available, so I moved back to New York. It felt like it was meant to be.” She has spent her entire professional life at the organization, and in 2017 took over the leadership of APF, working alongside the Director of Operations, Kathleen Lynch.

During this time, Instagram has reshaped the landscape of public engagement with art, and some APF projects have become the sort of pilgrimage sites that it was made for. Take Elmgreen & Dragset’s Prada Marfa (2005–), a decidedly contraband outpost of the Italian luxury brand in lonely Valentine, Texas, forever sparsely stocked with 2005 accessories, and never open for business. “Prada Marfa opened before Instagram,” Fremont notes, “but now it’s become such a social media sensation. It’s been interesting seeing how it has found its way into pop culture.” (A sign for the “store” was prominently featured in the home of a character in the TV show Gossip Girl [2007–12]). “That’s probably why,” she continues, “in the social media age, these projects have continued to be successful and are attractive to people— they’re visually striking and certainly photogenic, but also thought-provoking.”

With Fremont’s relocation to LA in 2020, APF entered a new chapter. While projects in New York are continuing— with Art in Focus, their ongoing program of art shown in Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center, as well as Art Sundae, their program which pairs artists with kids to create public projects—Fremont is also developing an as-yet-unannounced project on an LA museum campus. Meanwhile, at Frieze, APF is presenting new commissions around the fair site by Jose Dávila, Alake Shilling and Jennifer West, as well as a collaboration with Ruben Ochoa (see p.24). “We’re learning about and navigating the city,” Fremont says of the APF’s plans for her new hometown, “identifying spaces that make sense. It’s quite different from New York in the way that public art fits into the landscape, so we are working on how best to integrate.”

While their geographic footprint expands, Fremont isn’t fixated on growth at all costs. “We’ve always been a small organization—I don’t know if bigger is better necessarily—but we want to continue with these large-scale, long-term projects when the right ones come around.” The challenge in bringing artists’ dreams into reality is part of the thrill.

“Every one always feels impossible at the start,” she reflects. “And then seeing them realized is so exciting. There are moments when you’re in f ront of a sculpture, and it’s almost surreal because you’ve seen it on paper and talked about it for years.”

Jennifer Piejko

With careers as an animation director and a TV showrunner, Lyndon Barrois Sr. and Janine Sherman Barrois know a thing or two about representation. But at home in Lafayette Square, they are determined to hang the art in their collection ‘where it feels right’, as they share with Essence Harden. Photography: Chantal Anderson

ESSENCE HARDEN

Janine, you’re from DC, and Lyndon, you’re from New Orleans, and I wanted to start by asking how your hometowns have influenced how and what you collect?

JANINE SHERMAN BARROIS

I grew up in Massachusetts, then Virginia, right outside of DC, Chocolate City. My mom and dad always took us to museums. We had a very big old house and my mother used to buy big pieces of wood and paint abstracts on them. I just thought, “This is what moms do.” I didn’t realize she was trying to fill this house up with art, because we couldn’t afford to buy it. When we were of age to go to museums, I was always looking for Black artists that were like my mother or trying to see my face in them. But at that time, even when you went to major museums in the country, African American artists were not embraced in the way they are now. There’s been an awakening in the last 15, 20 years.

For me, collecting was about filling our home with all different types of African American artists, or artists of the diaspora, and having family and friends come and see themselves and feel themselves in the house. We don’t collect based on whether someone is famous or not, we collect from our gut and our gut might have allowed us to buy a Kehinde Wiley early on in his career. It might have got us a Mark Bradford, but it also got us an artist who was selling their work on the street outside MOCA.

LYNDON

Well for me, it just started growing up. Like most kids, I always drew, but then I just never stopped, and I went into art. I went to Xavier University [of Louisiana].

I did undergrad there and studied under John Scott. He was the most important teacher I had. John was exceptional as an artist and in the way he taught. He’d say, “I’m going to teach you guys everything I know, everything I’ve ever learned, because I want you guys to be the best you can be. But when you graduate from here, just know you’re my competition.” When you hear that, you could either be intimidated by it or you could grow from it. He made me see that my miniatures were art forms because they were sculptures and I didn’t realize how much of what I was learning from him, I was putting into them. He was also the first MacArthur Grant winner that I knew. I started to see all the possibilities in art and all the artists creating things. John would teach us, not just European stuff, but about a lot of his friends people like Martin Puryear, Sam Gilliam and Elizabeth Catlett and they would come to Xavier.

Seeing all these people’s work, you just think: at some point in my life, it would be cool to collect it. Then when I came to CalArts, I wasn’t even in that mindset. Years later when we started dating, Janine would come to the house that I was renting in Whittier and say, “You’re not an artist. Where’s the art on the wall?”

One thing I had was this cool-ass poster that’s in my studio now. When I had posters printed in New Orleans for the Boston Marathon and New Orleans Jazz Fest, the publisher gave me a Piet Mondrian silk screen from Pace Gallery in 1970. I didn’t think about its value I just appreciated having it because it was cool.

JSB What about New Orleans?

LB Grow ing up there, there’s Mardi Gras, jazz fests, music and food everywhere.

There is always something artistic happening. There’s so much artwork around, there’s NOMA [New Orleans Museum of Art] and CAC [Contemporary Arts Center] and posters being published. Then I worked at YAYA [Young Aspirations, Young Artists, Inc.] before going to CalArts.

One of the coolest things happened when I was in 10th grade. It was winter 1980, and in my English workbook on every page I drew a different sport from the Winter Olympics. Turning the book in, I’m thinking, “Oh, shit, man. Father Perry’s going to see what I’ve been doing and that I’ve not been doing the work.”

But when he gave me the book back, he wrote in it, “B- for the work, A+ for the artwork.” I will never forget it. That was typical for New Orleans.

JSB I had the same thing in DC going to Howard. It was the first time I had real proximity to art on a daily basis. Like a lot of HBCUs, Howard has a major collection and when you’d go to the library, for example, there would be great artists all around you, from Charles White to Romare Bearden.

EH There a re more formal ways of hanging things that are very Western and European, but the way that Black collectors hang their houses has this lush and abundant quality. It’s not stark, there’s not a blank white wall as if it’s a gallery, with a single work. It’s actually a conversation between artists, whether emerging or established, different materials and textures. In all of your spaces I saw that over and over again.

I’m interested in the choices to put particular artists in relation to each other. You’re getting new work all the time and changing things out, making new conversations happen. When I

hang something, as a curator, I have a conversation in mind. Thinking about your work by Greg Breda, I asked myself who was below him, because that’s a very direct relationship you’re creating.

JSB Jack ie Nickerson.

EH Right. That’s just one of the many instances in your home. What’s the narrative that you’re interested in creating between the artists?

LB When we have the opportunity to actually live with work, it’s not really a conscious thing of “this needs to go here and this needs to go there”. It’s just a case of, put it where it feels right.

JSB We like to have a house that’s engaging and open to everyone in all walks of life. I think that’s why a lot of people enjoy coming here. We didn’t want the pretension and preciousness of “this is a Mark Bradford and here is a blank white wall. He will hang by himself; he is one of the greatest of our time. Please come and look at our Mercedes and then our Mark Bradford.” Instead we wanted the vibe that this is a house in a historically Black neighborhood where art was bought at auction, on Instagram, at a student fair, at Frieze. Or it was bought at a great gallery, but also from an emerging one on Washington Blvd. Just like the people that we love coming to our home we don’t value anyone because of what they do, who they are, what they have.

LB We don’t rank our visitors.

JSB We don’t rank them, and we don’t rank the artworks. I hope that all of the artists in the collection get whatever they want. If they want to be catapulted and become renowned like Betye Saar, Amy Sherald or Kara Walker, I hope that happens for them. We don’t collect for that reason.

LB If they don’t, we’re still going to hang their work.

JSB We want the works to speak to each other, but even more so to speak to the people that engage with them when they come into the house.

LB We have a piece you didn’t see, in the dining room. It’s not hanging because it’s very heavy and I’m afraid it might fall. It’s 12 panes of glass with a portrait of Muhammad Ali by an artist named Henry O’ Henry, done in 1975.

JSB We got it at the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Mall in Leimert Park. There was a little show in the middle of the mall. People have come here from Tate, LACMA, MOCA or wherever, and they look at that piece and see the artistry behind it.

What actually makes someone the greatest? Is it that a curator has said it, is it that they’ve been tapped by someone in New York or a big institution? What is it and does it matter? To us does it matter? It’s just like understanding some people will get an Oscar. We get that, but we try not to have a hierarchy at all. And in the end if you come here we’re actually not interested in whether you like it or not.

EH It’s your house. You like it. That’s why it’s here.

JSB It’s our house. We like it. We’re happy that we’re having a conversation because clearly it’s doing its job. It’s making you feel something.

EH How does your collection have a relationship with people working intuitively as artists? Specifically around artists choosing materials that are more unwieldy compared to acrylic and oil, and those working in abstraction.

JSB We do collect a lot of figurative work. As we have expanded, we have got into abstract. There is such a tendency to

want to see yourself, but part of seeing yourself can also be seeing yourself in abstraction. We recently commissioned a phenomenal Shinique Smith and acquired an amazing Reginald Sylvester II and are looking at other great abstract artists. Their intuition is creating what they want and not necessarily doing what the markets want.

EH It fee ls like you’re growing and stretching look ing for other genres and media.

JSB Video work is important to us because we know that it has been important for Black artists.

EH You are both artists in different fields yourselves and I’m interested in how that influences you. You know the impact of what it means to be a working artist. How do your jobs link to what you collect? And how do the two maybe weave in and out of each other?

LB A lot of it, I guess, on a personal level is just the inspiration we get. I love waking up under those butterflies. I just love seeing how different artists approach and execute their work. It inspires me and I get ideas about how I’m going to execute my own work, whether it’s my miniatures or my feature film VFX work.

JSB As a creative and a showrunner, it was important to me for The Kings of Napa [2022–] to make sure that we put art in there so that people see how African Americans live and feel. Also I know, as an artist, as a writer, how hard it is to get things on the air that deal with Black subjects. That correlates to how hard it is for a Black writer, a Black painter, a Black sculptor or a Black collagist. I know because we’ve traveled around the world, we’ve gone to the Louvre and all the major museums, and we know who’s

being collected. Knowing the struggle and the importance of having our h istory represented globally has compelled both of us to be active on boards. Lyndon is on the board of the National Portrait Gallery in DC and in the last year, I joined the Hammer Advisory Board. We want to advocate, help fundraise, help acquire these artists because we want, in 50 or 100 years time, when people go to institutions around the world, for us to be celebrated. The only way that happens is through advocacy. That’s why we will fund a show or help fund a show.

LB Not only that, it’s also important to let Black people who aspire to be artists know that it’s possible. So often, people don’t have the opportunity or privilege to take the necessary risks, and instead are discouraged from doing it. When people see us and successful artists, it helps to promote that notion that you can do this too. We’re nothing exceptional or special. We made the sacrifices, we put in the time and work, we got into debt to achieve this. It’s doable.

JSB We’re also embracing the idea of passion being a way to make a living. In the past you became a lawyer, a doctor, an accountant. But I think now people are saying to children, you have to follow your passion. You need to have the encouragement of your community, your parents, your friends to make it happen.

LB Art is such a big umbrella. Everything, no matter what, started on a drawing board. From shoelaces up to the comb you use on your hair. You can choose to go into product design, advertising, layout design or animation, as I did. It’s all art and there are so many ways to make a living at it.

EH I thin k for Black collectors it’s very much about kinship and friendship

and forging paths and roads together to bring everyone up at the same time. What does this idea of belonging to a larger friendship web mean to you?

JSB It’s g reat. It’s been years of forging these relationships and it’s an amazing feeling to be around people at dinner and talk about art. You can discuss what you’ve seen. You can travel to another country and talk about art. I think that commonality has unified a group of people in a way that will result in lifelong friendships. And to talk about not only acquiring work, but celebrating artists and seeing how we can get them into institutions.

LB We as Black people have been doing the work in every aspect of life for so long and we’ve just been left out of the conversation. I always like to say the world is just catching up.

Janine Sherman Barrois is an award-winning writer and showrunner at Warner Bros. Her work includes Claws , Self Made and The Kings of Napa Through her production company, Folding Chair, she is currently executive producing the documentary Hargrove and the upcoming Apple TV+ series The Big Cigar She lives in Los Angeles, USA.

Lyndon Barrois is an artist and animator, with feature film credits including The Matrix Trilogy Happy Feet and Tree of Life He is an AMPAS VFX Executive Branch member. He’s also known for his unique, miniature gum wrapper sculptures and animated portraits of historical figures and events through his @itsawrapper studio. He serves on the boards of The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, California Institute of the Arts and on the Inclusion Advisory Committee at the Academy Museum. He lives in Los Angeles, USA.

Essence Harden is a visual arts curator and independent arts writer. She lives in Los Angeles, USA.

“We want the works to speak to each other, but even more so to speak to the people that engage with them when they come into the house.”

– Lyndon Barrois

Now Live Drop at lgartlab.com

LG Art Lab is its very own non-fungible token (NFT) platform that LG Electronics has launched starting from America. Accessible directly from the Home Screen in TV, the new platform enables users to buy, sell and enjoy high-quality digital artwork.

Delivering outstanding picture quality and offering several, large screen sizes to choose from, LG’s state-of-the-art TVs are the perfect medium for displaying and enjoying one’s NFT collection.

Barry X Ball, "Granulo-Specular Chiaroscuro Meta-Morph (Alchemic Copper)", Courtesy of Barry X Ball Studio, Inc

Barry X Ball, "Granulo-Specular Chiaroscuro Meta-Morph (Alchemic Copper)", Courtesy of Barry X Ball Studio, Inc

A stone’s throw from the ICA in the Arts District, Bert Youn’s The Good Liver has earned a devoted following for its selection of beautifully crafted, useful objects, from tableware to fabrics. This modern take on a general store is underpinned by a love of storytelling, as Eva Recinos finds.

Walking into The Good Liver, a downtown Los Angeles general store, it’s hard to resist the urge to pick up every object on the shop’s clean, open shelves. This carefully curated space boasts items from around the world: from a charming vintage Finnish money box in the shape of a bear, to German hand-forged cutlery and dyed fabrics from Thailand. It feels like a design gallery in a museum or indeed a gallery except at The Good Liver, you can (and should) touch the exhibits.

The Good Liver’s founder and owner is Bert Youn, whose main career is creating cartoons as an animator, story artist, writer and director. He discovered his fascination with well-crafted items during visits to Japan and Korea; he was drafted into the military while visiting his parents in the latter, spending two years in service and using that time to think about the next steps in his creative career.

Youn often helped friends with magazine photoshoots and videos, lending a hand with styling and sourcing objects which he found “through traveling and online digging”. Eventually, this sparked

an idea: an online shop where he could list his favorite finds. It went live in 2014 and, less than a year later, the brickand-mortar iteration of The Good Liver opened. “Online pictures didn’t really do them justice,” says Youn, “the beauty of the items could only come through actually seeing them in person, touching them, feeling the weight and really seeing the details of how everything was made.”

For Youn, part of the value of the objects is the stories they tell about the people and places that produced them. A ceramic tableware series from Iruma, Japan, for example, shows the earthy effect that happens when “ash is added to Shigaraki clay,” as detailed in the product description; a minimalist brass wind chime comes from a fabricator founded in 1609 in Takaoka, Japan, whose “master craftsmen” carefully render each piece. “I needed another outlet for a different kind of storytelling, that could benefit from my expertise acquired from my primary job,” he says. “I just wanted to take that further.”

Opposite Items from The Good Live r. Clockwise from left: Iron Household Scissors, Korean Bronzeware Plate, Brass Triangle Hanger, Brass Candle Holder Photography

Sergiy Barchuk

Browsing through the shop’s inventory, I’m drawn to some Japanese brooms made from bound Tampico fibers, and a soap tray carved from Kiso Hinoki wood: everyday essentials, elevated through their use of materials and thoughtful modern design. This commitment to simplicity is continued in furniture pieces Youn himself designed specifically for the space. Whenever he found the budget and time, he collaborated with friends to make each piece, uniformly fashioned from American red oak. “I try not to overshadow the products we sell with the furniture we design,” says Youn. “They’re simply designed so that they’re like a frame for the goods.”

The shop counts on word-of-mouth recommendations to d raw in design enthusiasts; the team does little online marketing. Yet, art lovers and shoppers alike may have come across Youn’s curation of goods in other ways. In 2018, for example, he presented a selection of items at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, themed to coincide with their restaging of Harald Szeeman’s

exhibition “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us” (1974). (The ICA has featured pop-up shops from experimental retailer Days LA and independent bookseller Marfa Books Co.). Youn also collaborates with Kettl, a New York-based company that brings Japanese matcha to the US. He carries their products and organizes events in the shop; recent activations include a matcha tasting and brewing class, and Korean tea tasting.

The tea ceremony is a fitting parallel for the Good Liver proposition: while Youn stays busy, with imminent plans for a second retail location to house items that don’t quite fit the existing store’s categories, his ultimate aim is for visitors to slow down, and “just take their time” to experience and enjoy the beauty of the everyday items he finds so fascinating

On view during Frieze Week, MOCA presents a retrospective of the pioneering Los Angeles artist, Simone Forti. The first such exhibition on the West Coast, it will include weekly performances of her ‘Dance Constructions’ (1960—61), which drew on Forti’s studies in Marin County with choreographer Anna Halprin. Described by Forti as dances that “also can be seen as sculpture made of people”, the schedule includes the seminal Huddle, in which performers interlock their bodies, creating a surface for one breakaway performer at a time to climb over, eventually reaching solid ground and rejoining the group.

During preparations for the exhibition, photographer and director Gillian Garcia was granted access to the rehearsals for Huddle to create a special photo commission for Frieze Week. Capturing the patient labor of the performers as they realise this piece anew, Garcia creates a warm visual poem about parts and the whole, support and surrender, tension and joy.

The fair continues online. Discover artworks by artist and price, get in touch with galleries and explore immersive 3D rooms

, 2 0

Frieze Week is your last chance to visit the landmark exhibition, “The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art” at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Billed as the “first of its kind in the West”, the exhibition presents more than 130 works from a period of great upheaval: from the twilight of the Joseon dynasty through to the bloodshed of the Korean War and the following settlement. The second exhibition organized by LACMA and Hyundai Motor’s Korean Art Scholarship initiative, the exhibition’s curator Dr. Virginia Moon has created a structure across five thematic sections to organize the works of 88 artists. Moon places a special emphasis on the range of media introduced to Korean artists through dialogue with the wider world, from Shin Nakkyun’s photographs of the performer Choi Seunghui to the abstract metal sculptures of John Pai. As a tribute to the growing global presence of K-culture, the audio guide accompanying the exhibition is provided by none other than the icon RM of K-pop group BTS.

Los Angeles is home to the largest Korean community outside of Korea, and to mark the closing of the exhibition, Frieze Week invited members of GYOPO, the LA-based collective of diasporic Korean cultural producers and arts professionals, to select their personal standout works from this historic selection.

Caroline Ellen Liou selects Research (1944) by Lee Yootae