FRIEZE WEEK

THE SHED, NEW YORK MAY 17–21, 2 0 23

Dining Tips Sarah Arison: e Power of Patronage

Alex

On Selecting a Space Mary Lum’s Printed Matter Picks Charlie Engman: Mutation and Movement

Ignacio Mattos’s

Courtney Willis Blair Steps Up

Tieghi-Walker

GEM DIOR COLLECTION Pink gold, white gold and diamonds.

GEM DIOR COLLECTION Pink gold, white gold and diamonds.

CELEBRATING THE INAUGURAL WINNERS

FILMMAKER & PRODUCER

WANG BING

DANCER & CHOREOGRAPHER

MARLENE MONTEIRO

FREITAS

MUSIC COMPOSER & PERFORMER

JUNG JAE-IL

ARTIST COLLECTIVE

KEIKEN

GAME DEVELOPER & DESIGNER

LUAL MAYEN

FILMMAKER

RUNGANO NYONI

ARTIST & POET

PRECIOUS OKOYOMON

THEATER DIRECTOR

MARIE SCHLEEF

FILMMAKER

EDUARDO WILLIAMS

DANCER & CHOREOGRAPHER

BOTIS SEVA

CREATING THE CONDITIONS FOR ARTISTS TO DARE

Image: Keiken, 2021

Image: Keiken, 2021

SCULPTED CABLE COLLECTION 57TH STREET PRINCE STREET SAKS 5TH AVENUE

DAVIDYURMAN.COM

CONTENTS

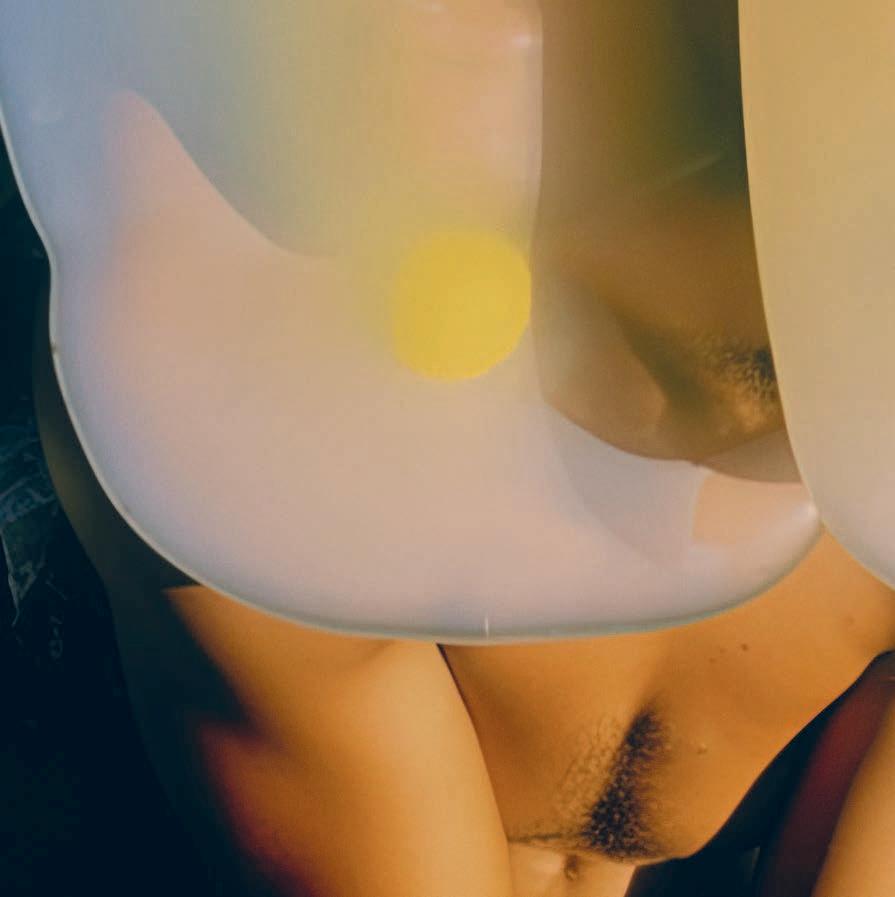

“ ree is a magic number.” So sang Schoolhouse Rock! ’s Bob Dorough—or De La Soul, depending on your references. is is the third year in which Frieze New York takes over e Shed, bringing presentations by galleries from 27 countries to the art world’s capital. is issue of Frieze Week responds to the scene in our host city: from the Black women dealers taking charge at some of New York’s biggest galleries (p.12), to agile spaces finding their own unique nooks (p.42), and the major museum shows of the season (p.18). We also turn the spotlight on collaborations with local non-profits: Artadia (p.22), the Artist Plate Project (p.24) and Printed Matter, Inc. (p.20), which you can find at the fair, while Frieze’s Christine Messineo and e Shed’s Tamara McCaw share their respective engagement with the city’s communities and highlights of the week (p.9). Charlie Engman’s portfolio showcases his distinctive use of A.I. (p.48). His sensuous cover image suggests two lads merging into one being with two heads.

ree is the number of love, my mother says, because out of two comes one more.

Matthew McLean, Editor and Creative Lead, Frieze Studios

28 Maestro Dobel

30 Young Hearts Run Free Meet Sarah Arison

42 A Separate, Little World

A New Space for Self-Taught Makers

46 Written on the Wind

Joe McShea & Edgar Mosa’s Colorful Creations

48 Welcome to My Island

e A.I. Dreams of Charlie Engman

56 Chef’s Choice

A Q&A with Corner Bar’s Ignacio Mattos

7 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK 9 Civic Center Serving the City’s Communities 12 e Next Generation Black Women Dealers to the Front 18 Supply and Demand Consuming the Work of Josh Kline 20 Read the Room Essential Titles from Printed Matter Inc. 22 Posting Up Jessica Vaughn’s Bold Fair Commission 24 Dinner Service A Project Serving Up Social Justice 26 Deutsche Bank Global Lead Partner Deutsche Bank Global Partners On the Cover Charlie Engman, Pressed Flowers, 2023 Frieze Week is printed in Canada by Imprimerie Solisco and published by Frieze Publishing Ltd © 2023 e views expressed in Frieze Week are not necessarily those of the publishers. Unauthorized reproduction of any material is strictly prohibited.

12 24 48 56

Frieze New York Partner Global Media Partner

Luc Tuymans

new york through june 17

Yayoi Kusama

new york through june 17

Katherine Bernhardt

hong kong opening may 20

Sherrie Levine

new york and paris through june 17

Elizabeth Peyton

london opening june 7

Lisa Yuskavage

paris opening june 9

Bob Thompson

new york — 52 walker through july 8

David Zwirner

new york los angeles london paris hong kong online

How can cultural institutions engage the diverse publics and cultural communities of New York City? Frieze’s Director of Americas, Christine Messineo, and Tamara McCaw, The Shed’s Chief Civic Program Officer, discuss their approaches for Frieze New York and The Shed.

CIVIC CENTER

TAMARA MCCAW

is is the third year of Frieze New York taking place at e Shed. What is your vision for the fair now that it has adapted to this setting?

CHRISTINE MESSINEO

Involving New York non-profits has been part of Frieze New York since the outset, and now that our partner in the fair– e Shed–is a non-profit, this is an even more distinct part of the fair’s identity. Because Frieze New York utilizes a smaller footprint than some other Frieze fairs, my approach is to honor just one or two non-profits a year and give them a bigger platform, not only for fundraising via sales, but to really create an understanding of their mission and history. is year non-profits include Artadia, the Artist Plate Project, Printed Matter Inc., Vote.org and others. ese presentations happen right alongside those by galleries, so we hope to foster a sense of community. How does the idea of community inform your approach to the role of Chief Civic Program o cer?

TM A community-centered approach has always been fundamental to my practice. My 17-year tenure at Brooklyn Academy Music (BAM) enabled me to partner in deep and meaningful ways

with community boards, neighborhood development organizations and business improvement districts, during a period when BAM’s immediate neighborhoods experienced extreme waves of gentrification. Navigating these changes shaped my understanding of the indisputable role cultural institutions have as cultural citizens and neighbors. A civic practice that centers on co-creation, accountability and shared leadership, evolved organically from there and is now cornerstone of e Shed’s civic work. I believe any organization’s future vision must include and benefit its wider communities. CM at idea of civic practice is very resonant. I was very struck to learn that e Shed is a site for early voting, and I’m really pleased that we will again this year give a platform to Vote.org and PLAN YOUR VOTE. I think this is a particularly important issue to put in front of our younger visitors, whether it's the school groups whom we o er tours to via outreach, or young adults who are art curious.

e spark for PLAN YOUR VOTE was looking at the imagery around voter engagement and wanting to make it more compelling. I’m a big believer that visual communication has the power to transform society. For the last Frieze Impact

Award in LA we worked with the nonprofit Define American, which gave a very visible platform to immigrant narratives at Frieze Los Angeles. I’m thrilled to dedicate space at this year’s fair to an installation by ektor garcia, an emerging Latinx artist born in California and working in Mexico. Supported by Maestro Dobel, this will explore forms of Latinx identity and heritage. I wonder, when you talk about e Shed’s wider communities, how the migrant community figures in your civic programming?

TM e need to support all New Yorkers, new and old, is ever more urgent. e Shed’s immediate neighborhood has one of the highest concentrations of unhoused people in NYC: one in four students in our community board district experiences persistent housing insecurity. Major transportation hubs Penn Station and Port Authority are nearby, so the neighborhood housing crisis a ects growing numbers of asylum seekers. Meeting needs now and responding to the extreme present are our guiding principles, so when e Shed was given the opportunity to partner with NYC Public Schools’ Manhattan Borough Response Team to organize food and clothing drives, we jumped at

it. We now host quarterly days of action and fairs that feature dozens of organizations providing healthcare resources like on-site vaccinations, blood tests and clinical care and advice for navigating insurance, as well as resources for social services like legal aid, food assistance, school enrolment, and adult education and employment pathways.

CM I find these instances of direct action very inspiring. It’s one of the reasons that we invited the Artist Plate Project to the fair this year. ey invite leading artists to create limited edition, beautiful plates, which are sold to benefit the Coalition for the Homeless. e purchase of a single plate provides something like the equivalent of ten hot meals for an unhoused person in NYC.

TM What else is new to the program this year?

CM A new initiative this year is the Frieze Artadia Prize, which will debut a new commission by the New York-based artist Jessica Vaughn, which manifests a kind of alternate map of America through her intervention in the postal system. We opened applications for the Prize to past recipients of Artadia’s awards to draw attention to its unique model, which provides funding to artists in key US cities at

9 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK IN CONVERSATION

Above e 2023–24

Open Call artists. Standing, left to right: Kayla Hamilton, Bryan Fernandez, Christopher Radcli Calli Roche, Garrett Zuercher, Armando Guadalupe Cortés, Jake Brush

Seated, left to right: Kyle Dacuyan, Lizania Cruz, Asia Stewart, Luis A. Gutierrez, Minne Atairu, Sandy Williams IV, Je rey Meris

Not pictured: Cathy Linh Che, e Dragon Sisters, Nile Harris, NIC Kay, Yaa Samar! Dance eatre.

Courtesy: e Shed; photograph: Dana Golan

crucial junctures in their careers—whether that’s to help with a first studio or with scaling up production ahead of a major exhibition. It’s about allowing artists to reach the next step in their practice at stages of their career when support might not be available. Is there a parallel here with e Shed’s Open Call program?

TM Yes, our goal with the Open Call is to increase opportunities and outcomes for local artists who haven’t yet received major commissioning support. Artists at this stage aren’t always a orded platforms, scales of venue, visibility and a chance to produce new work. With Open Call, we make available all our tools and resources for emerging artists to experiment at scale. As one of the founding organizers, I not only produce the performing art projects, but ensure the shared leadership model that includes 70 reviewers and panellists, and a network of mentors and peers who guide individual projects and access initiatives.

Who are some of the emerging artists whose work you’re especially looking forward to seeing in the fair this year?

CM e whole Focus section is a platform for our audiences to engage in-depth with emerging practices and make discoveries. is year, it will feature galleries under

12 years old based in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, Korea and Nigeria, as well as some of New York City’s most groundbreaking spaces.

In the fair’s main section, it’s exciting to also see global diversity among our exhibitors. We’ve strengthened our representation of Asian galleries, added an exhibitor from Manila in the Philippines, and can boast nine galleries taking part from South America. I’m excited that the Tehran-based Dastan Gallery is going to show the work of five Iranian women artists. Given the very contested situation of women’s rights in Iran at this time, it feels urgent to see their expression on their own terms. What will be on your agenda for Frieze Week?

TM Within the fair I’m interested, as with every year, to see the work of BIPOC artists and the themes that emerge from their work. It’s a lso encouraging to see greater representation of Black gallerists. Around town, I’m looking forward to New York Live Arts’ Live Ideas Festival. While folks are here, they should definitely see ‘A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration’ at Brooklyn Museum and Ming Smith at MoMA, before they close.

CM Yes! Nicola Vassell showed a beautiful selection of Ming Smith works at Frieze Los Angeles this year.

TM What about you–what are your “must sees” across the city?

CM Besides the museums and non-profits, it will be exciting to navigate the city’s galleries and their shows. e Shed is so well located for such active gallery districts like Chelsea or Tribeca. ere’s such a sense of proximity to so much of the city’s cultural fabric. is year at the fair, two galleries are making a joint presentation of work by the Swiss artist Pamela Rosenkranz, whose eye-catching new commission for the High Line is going to be unveiled ahead of the fair’s opening. I love the idea that someone can explore the artist’s work at Frieze in e Shed and then walk out and encounter it in a whole new dimension, right on our doorstep.

MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK IN CONVERSATION 1 0

O cer at e

Christine Messineo is Director of Americas at Frieze. She lives in New York, US. Tamara McCaw is Chief Civic Program

Shed. She lives in New York, US.

Above Pamela Rosenkranz, Old Tree (rendering), 2023. A High Line Plinth commission. Courtesy: the artist, the High Line, Karma International, Miguel Abreu Gallery and Sprüth Magers

ere’s such a sense of proximity to so much of the city’s cultural fabric.

This year, White Cube opens its long-anticipated space on the Upper East Side, marking the gallery’s 30th anniversary. At its helm: Courtney Willis Blair, who joins a growing number of Black women dealers who are leading some of New York City’s most renowned blue-chip galleries into a new era, guided by their individual savvy and care. Report and interviews by Jasmin Hernandez.

THE NEXT GENERATION

is September, the internationally recognized mega-gallery White Cube arrives in New York at a multi-level space on Madison Avenue on the Upper East Side. Marking 30 years since it first opened in a small room in London, this next era of the gallery will be shaped by newly appointed US Senior Director, the dynamic Courtney Willis Blair.

A curator, writer and formerly Partner and Senior Director at the gallery Mitchell-Innes & Nash, Willis Blair will lead on White Cube’s New York programming and overall US strategy. At her former gallery, she brought Gideon Appah and Jacolby Satterwhite to the roster, and curated stellar shows, including “Embodiment”, a group exhibition featuring splashy and sensual works by Cheyenne Julien and Jonathan Lyndon Chase. She’s written for notable art publications and edited books on artists including Keltie Ferris, General Idea and Pope.L. rough Entre Nous, a supper club for Black women in the art world, which Willis Blair founded, she has fostered an intimate network and community of peers: including the four other accomplished dealers interviewed in this feature.

Black women are flourishing and innovating throughout the New York City art ecosystem. If you’ve done your homework, you’ll know that this isn’t just a “moment”, but rather due to decades of cultural labor performed by Black women, past and present, not only in New York but across the US. e groundbreaking influence of the storied Just Above Midtown (JAM), founded by film director, food activist and art dealer-disruptor,

Linda Goode Bryant, was recently acknowledged by the establishment of an archive at New York’s MoMA. In 1974, Goode Bryant, then 25 and a mom of two, started JAM as an “autonomous Black space”, a first-of-its-kind, Black womanowned enterprise, that ranfor 12 years across three locations in Manhattan, where Black artists, as well as artists of color, produced radical and freeing work, particularly for Black artists who explored conceptual art, video and performance. Taking place at MoMA (only four blocks from JAM’s original 57th Street location), the recent exhibition “Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces” (2022–23) reimagined the space’s energy—very DIY, anti-establishment and brimming with non-monolithic ideas on Blackness— through archival videos of performance, photographs, painting, sculpture, with works by Dawoud Bey, Senga Nengudi and Lorna Simpson, among others. (JAM and its artists was subject of a tribute section at Frieze New York in 2019.) Funded by the Mellon Foundation, and supported by a one-year term archivist, t he JAM archives will live within MoMA’s research collections, encompassing artists’ files and slides, press releases, gallery publications and more, available to arts professionals, students and the wider public.

Goode Bryant was not alone in laying foundations for Black women in the US art world today. Suzanne Jackson, dancer, artist and founder of Gallery 32, ran her self-funded community-focused art space from 1968 to 1970 in Los Angeles, showing Black feminist artists such as Betye Saar

and the late great Gloria Bohanon. (Jackson’s own art was exhibited in 2019 at O-Town House, a gallery based in the same Granada Buildings complex which housed Gallery 32.) Shirley Woodson, an oil painter widely recognized as Detroit art royalty, served as gallery director at the Black-owned Pyramid Gallery in downtown Detroit in the late 1970s, where she promoted the vibrant figurative work of Ernie Barnes—recently a marquee auction name—and Varnette Honeywood. Back in New York City, Peg Alston, a venerable private dealer who started working in 1971, exhibits influential 20th century Black American artists like Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett, while also dealing in traditional African sculpture. Having managed Romare Bearden’s career during his final years, June Kelly opened her namesake SoHo gallery in 1987, and currently represents diverse practices including figurative painter Philemona Williamson, Korean-born Su Kwak and poet Derek Walcott.

Today, there is an ever-growing number of successful Black women-owned galleries throughout the US, including Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Jenkins Johnson Gallery, Hannah Traore Gallery and Nicola Vassell. Meanwhile, Willis Blair, and a younger generation of Black women art dealers—all in director or partner roles at established blue-chip galleries—continue the work of their pioneering Black women dealer predecessors in a new context, guiding their respective galleries into the 21st century, engaging both local and global audiences, and leaving the door open for the next generation of young Black women in art.

12 GALLERIES MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Opposite Courtney Willis Blair at the White Cube viewing space in New York, March 2023

Photography Courtney Sofiah Yates

Black women are flourishing and innovating throughout the New York City art ecosystem.

and Adjunct Project. She

Poddar an art historian and Curator at the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi She lives in London, UK.

Eva Langret is director of Frieze London. lives in London, UK.

COURTNEY WILLIS BLAIR US Senior Director, White Cube

How are you developing a specifically US strategy that still feels tied to White Cube’s overall ethos?

Our presence in New York will allow us to expand several areas of the business, from artist engagement and programming to further developing our secondary market activities. White Cube New York will be a launchpad for exciting initiatives that build on what the gallery has achieved in Europe, Asia and online in recent years.

We’re also thinking about the needs of artists, museums and collectors in other regions of the country and not just in the major cities. As for how this approach dovetails with our global personality: for 30 years White Cube has been known for being artist-led, pioneering and ambitious, and our New York space will maintain that core ethos.

Arts writing has been foundational to your career, what excites you about continuing this at White Cube?

Scholarship is integral to an artist’s career. Oftentimes what remains after an exhibition ends is the writing. White Cube has, from the beginning, made truly astonishing publications, many of which have won prestigious honors. It’s exciting to think about being part of that lineage, to continue scholarship for our artists, and to create stunning objects that will be referenced again and again. Who are Black cultural sheroes and trailblazers you admire?

I couldn’t possibly name them all.

We tend to think these lists will be short because we give so much weight to a certain level of visibility. But I know how much work is done in the shadows and how important it is to acknowledge those who have made invaluable contributions but never received the public accolades.

So, this certainly isn’t an exhaustive list: Toni Cade Bambara, Peggy Cooper Cafritz, Julie Dash, Nikki Giovanni, elma Golden, Linda Goode Bryant, Lorraine Hansberry, June Jordan, June Kelly, Nancy Lane, Toni Morrison, Adrian Piper and Lowery Stokes Sims. Can you expand on the inaugural show you’re curating at White Cube’s forthcoming New York space?

I’m really excited at the opportunity to curate the debut exhibition at the new White Cube gallery at 1002 Madison Avenue. e show considers how artists are using the same frameworks we see in music traditions—sampling, the cover, the remix and the mashup—to rethink or subvert established ideas. It’s really a look at the u se of experimentation and distortion as both conceptual and technical tools that can lead to innovation. We’ve received an incredible response from artists so far.

White Cube is known for programming rigorous, thought-provoking group exhibitions: from the survey of surrealist tendencies in the work of fifty women artists, “Dreamers Awake” (2017), to “Sweet Lust” (2022), curated by Michèle Lamy with Mathieu Paris, exploring the body. I think it will be an elegant, searing addition to that tradition.

ALEXIS JOHNSON Partner, Paula Cooper Gallery

Starting out at 1301PE in LA, Alexis Johnson was Associate Director at Paula Cooper Gallery for six years, before becoming Director & Artist Liaison at Lévy Gorvy. In 2021, she returned to Paula Cooper as Partner, as part of the esteemed founder’s succession team, and one of two Black partners. Something I find fascinating about your journey is that you’ve returned to two galleries twice, 1301PE in LA, and you’re now back at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. How have these decisions to return, and to lead, impacted your art dealer trajectory? My decision to return reflects the honesty and endurance of my relationships. Even after I departed each gallery, I remained in contact with the owners, sta and artists out of genuine a ection. My trajectory in the art world has been organic. I’ve never done a job search for a gallery position. All of my experiences are born out of friendships. I was once told by a former employer that I don’t take enough advantage of my relationships in the art world: i.e. for sales purposes. My response then is still true today: the reason I have these relationships is specifically because I don’t exploit them.

Now as Partner, what does success mean?

Success is a moving target. e world is overflowing with galleries and their rosters, so I’m always brainstorming ways in which to shine a light on our artists. ere have been so many shifts in the workplace since March 2020, and the present challenge is maintaining the profoundly human spirit that has always guided the gallery,

while also evolving to serve our artists within an increasingly professionalized art world. Personally, I became a wife and mother the same year as my gallery partnership, so it’s a learning curve to balance all of that at once.

You began championing the legacy of Terry Adkins during your time at Lévy Gorvy. How will this continue now at Paula Cooper Gallery?

Working with the Estate of Terry Adkins is an honor that is bittersweet. It’s a pity that Terry isn’t here with us to see his work being celebrated by a wider audience.

Nevertheless, I’m proud of the work I’ve done in collaboration with his widow Merele Williams-Adkins and the Estate on several major museum exhibitions and important acquisitions. ere is much the world has yet to discover about Terry, and I’m committed to continuing to champion his work—the poetics, relevance and influence of his work are enduring. Who are some Black women in the art world that you share a sisterhood with and what makes that bond special?

When I began working in galleries in the late 1990s, I didn’t know of any other Black women working in a contemporary art gallery. When I met Steve Henry, my colleague at Paula Cooper, friend and brother from another mother, around 2003, he was the only Black person I knew working in a commercial gallery. [A Director since 1998, Henry was made a Senior Partner at Paula Cooper Gallery in 2021.] In a way, from this experience, I feel I share a sisterhood with all Black women in the art world. We work in a field that has largely been dominated by a white Western perspective and aesthetic. I cannot help but feel bonded in some way to any of us who have carved out a place for ourselves here.

EBONY L. HAYNES Senior Director, David Zwirner & 52 Walker

For the last two years, Ebony L. Haynes has been leading 52 Walker, a blend of commercial gallery and Kunsthalle , established by David Zwirner. Also a curator and writer, Haynes was formerly Director at both Martos Gallery and the project space Shoot the Lobster, in New York and Los Angeles.

You envisioned 52 Walker as a slowdown—for galleries, artists, art workers and visitors. Coming up on two years this fall, what takeaways do you have about 52 Walker’s success? And especially its engagement?

My main takeaway is that people really understand and show up for the 52 Walker mission. ey seem to enjoy this Kunsthalle gallery model and the ethos we’re cultivating, which has been rewarding to say the least. Engagement varies depending on the show, but we get such a range—collectors, students, artists, writers, even haters of all ages— a nd I think that’s an integral part when measuring the success of an exhibition.

14 GALLERIES MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

Below, top ‘Red Green Blue’, 2022, installation view, Paula Cooper Gallery. © Paul Pfei er. Courtesy: Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photograph: Steven Probert.

Organized by Alexis Johnson

Below, bottom ‘Tau Lewis: Vox Populi, Vox Dei’, 2022–23, installation view, 52 Walker, New York. Courtesy: 52 Walker, New York

Curated by Ebony L. Haynes

At 52 Walker, you’ve reunited with artists such as Kandis Williams and Tau Lewis, whose work you’ve curated in the past. Can you describe how this hybrid space allows you to nurture their careers (and those of other artists)?

I’ve previously worked with so many of the artists included in the first two years of our programming. It’s really their work that nurtures my curatorial practice. If there was something that piqued my interest in the past, that doesn’t disappear with time. On the contrary, I’m eager to show the world more! And 52 Walker o ers a unique opportunity as a gallery model that allows for flexibility, growth and exploration. Can you talk about the Clarion publishing series with artists?

Clarion is absolutely collaborative and a product of true partnership. It’s great because it allows for another element of the exhibition to exist, and for a closer

look at the artist(s). It also becomes an addition to our 52 Walker archive—an archive that is integral to the space. We get to take a broader look at what the work and the show mean in a larger context, both culturally and historically, within the gallery and in an art world setting. How do you pay it forward to Black women and femmes seeking pathways in the gallery world?

Anytime you see a Black woman in a gallery, know that it wasn’t an easy road. For that reason, I teach a free course for Black students called “Black Art Sessions” which advises on pathways to work in art galleries, museums and not-for-profit spaces, and I work with HBCUs for our internship program. I hope to always provide a space for Black people to feel welcome and free to ask questions about how to access a world that may otherwise feel opaque and guarded.

CHRISTIANA

INE-KIMBA BOYLE

Senior Director of Sales & Global Head of Online, Pace Gallery

Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle was formerly Senior Director at New York’s Canada, where she implemented digital strategies, including the gallery’s first online viewing room and a virtual performance platform. She joined Pace Gallery in 2021.

Your role at Pace Gallery is robust, from online and IRL curation, to artist liaising. Can you talk about bringing on your first artist Kylie Manning?

My role at Pace is incredibly multifaceted: artist-liaising, curation, sales and leading on digital programming and strategy— but what I enjoy most about my position is that all aspects of my job filter into championing and supporting artists. Kylie Manning is the first artist I brought to Pace and began working with. is relationship has taught me so much about being a true advocate and the patience and nimbleness it takes to build a longstanding career. Most importantly, the trust you must instill in your artists. As Senior Director of Sales, what are some interesting trends you’re seeing amongst millennial collectors in 2023? Millennial collectors are diversifying their collections beyond mid-career and emerging. Many are aging up and have more spending room to acquire works by established artists. Works on paper, domestically scaled paintings and sculptures are brilliant entry points for many.

You curated two shows in New York in 2021 that, for me, were standouts: “Black Femme: Sovereign of WAP and the Virtual Realm” at Canada and “Convergent Evolutions: e Conscious of Body Work” at Pace , both exploring agency and autonomy of the body. What led you to explore these ideas in both projects?

I’ve always been hyperconscious of agency as a Black woman: how my body exists within society and a white cube, and how it’s outwardly perceived. e pandemic drew us to the internet/social media as our only means of connecting with art. “Black Femme” was the entry point—a commentary on the cultural contributions of Black femme-identifying creatives who’ve constructed and contributed to the virtual canon (the internet) and how their work was adopted in real time and space. “Convergent Evolutions” extended this investigation, as we physically returned to the white cube, and was an inclusive conversation on agency through technical practice.

I’m continuing this research, with two follow-up exhibitions planned for the next two years.

Who are some Black women and femme artists working at the intersection of digital art, technology and the internet that you admire?

ere are many: Linda Dounia, Eileen Isagon Skyers, Kenya (Robinson), Ada Pinkston, Qualeasha Wood and @yungprempelli. I could go on!

JOEONNA BELLORADO-SAMUELS

Director, Jack Shainman Gallery & Founder, We Buy Gold

Joeonna Bellorado-Samuels is a longtime Director at Jack Shainman Gallery and the Founder of We Buy Gold, a nomadic gallery of six years.

e state of the world is constantly shifting, but what are the values you think of when planning an artist’s exhibition at the gallery?

Supporting the artists and their vision for presenting what’s most often their newest body of work, is what we do the vast majority of the time. When I think about values, I’m always brought back to the artist and being a platform for them to realize their ideas. at’s always at the core.

Your nomadic gallery, We Buy Gold, just turned six this year and you’ve curated exhibits inside empty storefronts in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, to commercial billboards all over New York City.

What has this freedom and flexibility taught you over the years?

e flexibility was birthed out of necessity but the freedom that it has brought me was of more value than I could’ve imagined.

To this day, I try to center myself in those lessons, or at least remind myself… ere’s a responsiveness that can come when you work outside of a structure or rubric. I deeply appreciate the balance it has brought me. Most importantly, I look back and think of how the rules I made in the beginning were mere guardrails, not limitations.

How do you mentor Black women and femmes seeking entry into the art world?

I hope that the representation that was so important to me is something that I can continue to provide for others. I also try to be accessible and available. We all engage in our own worldmaking and I try to act consciously when building my own.

How do you balance business and softness with the artists you work with?

When you care deeply about someone, their ideas, their goals and their wellbeing, then the balance comes. Like any relationship, trust is at the core, on both

15 GALLERIES MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

sides.

Jasmin Hernandez is the creator of the platform Gallery Girls, and the author We Are Here: Visionaries of Color Transforming the Art World (2021). She lives in New York, US.

Above, top ‘Convergent Evolutions: e Conscious of Body Work’, 2021, installation view, Pace Gallery, New York. Courtesy: the artists and Pace Gallery, New York. Photograph: Kyle Knodell and Jonathan Nesteruk

Curated by Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle

Above, bottom ‘Radcli e Bailey: Ascents and Echoes’, 2021, installation view, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Radcli e Bailey. Courtesy: the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Organized by Joeonna BelloradoSamuels

Frieze Week boasts a raft of must-see exhibitions: from Lauren Halsey and Cecily Brown at the Met and “Young Picasso in Paris” at the Guggenheim, to Mugler couture in Brooklyn and Wangechi Mutu at the New Museum. At the Whitney is the first US museum survey of Josh Kline, whose works addressing technology, labor and class have won him wide acclaim. But how does an art of critique avoid “curdling into satisfaction”? Paul

McAdory

considers.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

In 2016, writing in the New York Times, Roberta Smith compared works in Josh Kline’s show, “Unemployment” at 47 Canal in New York, to “one-liners with many clauses, all sobering, but obvious and dull.” e exhibition included Kline’s series “Productivity Gains”, for which the artist used scans of unemployed people living in Baltimore to produce 3D-printed sculptures of their bodies. e life-size objects, folded fetal-style, sealed in plastic bags and spread across the gallery floor, posit the jobless middle class as economic waste products. In another series, transparent plastic orbs, spiked to resemble viruses and hung like waist-high chandeliers, housed cardboard boxes packed with o ce supplies and other e ects of the newly laid o . Its title: “Contagious Unemployment”.

An ArtNews headline, au contraire, hailed “Unemployment” as “a Brilliant, High-Concept riller”; an approving Artforum reviewer said Kline “merges social science with science fiction”. Alternatively, as one museum worker put it to me recently, Kline makes “obvious Anthropocene boy art”. To me, it sometimes looks like crapitalism art, recalling the visual language of Adbusters, the “Journal of the Mental Environment”. For example, in his 2020 show “Alternative Facts” at Various Small Fires in Seoul, Kline cast Samsung and LG televisions and wrapped them in American and Blue Lives Matter flags. Reality Television 16 (2020), from the American flag series, was doused in white epoxy—“the skin color of Fox’s primary

viewership”, a gallery director told writer Travis Diehl during a Zoom tour reported in Art in America e lone Blue Lives Matter piece on display, meanwhile, was titled Fox and Friends 5 (2020). Kline’s art is, in other words, the sort that induces you to nudge your neighbor in the ribs and trade expressions of forlorn apprehension, which, perhaps, then curdle into satisfaction. Whether it’s a one-liner or not: surely, we get the joke.

e press release for Kline’s first US museum survey, “Project for a New American Century”, on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York during Frieze Week, states that, “at its core, Kline’s prescient practice is focused on work and class, exploring how today’s most urgent social and political issues— climate change, automation, disease and the weakening of democracy—impact the people who make up the labor force.”

If anyone should be aware of work and class as “urgent” issues, it’s the Whitney, whose unionized workers agreed to a tentative first contract on March 6 this year, after 18 months of negotiations. is welcome development spared Kline the awkwardness of exhibiting explicitly activist art amidst a labor-management stando . Had the negotiating been ongoing, I wonder if his approach would have landed di erently. Is it possible that art about “work and class” is, in fact, best delivered as a series of one-liners? Might some artists be right in prizing bluntness over subtlety, in the hope of raising consciousness among viewers, confronting

audiences with capitalism’s rapaciousness and implicating them in its production of our bleak future? If people go to art museums to be consumed, don’t they also want to feel that they have consumed an accessible critique of themselves and broader power structures? (To feel themselves confronted, to bear witness to being implicated ). To register as e ective, and thus a ectively gratifying, the critique must be digestible by its audience. But what enters a body tends to leave it. If the message, that something must be done, remains for a few hours or days, excretion can return its consumer to their baseline: apparently necessary participation in and acceptance of the world as it is.

“Now the highest aspiration of avowedly radical work is its own display.” e statement is from Hannah Black, Ciarán Finlayson and Tobi Haslett’s 2019 manifesto, “ e Tear Gas Biennial”, published by Artforum, which argued for ousting then-vice chair of the Whitney board Warren Kanders (in response to his ownership of a company that manufactures and sells tear gas and other armaments used to suppress protests in the US and elsewhere), and for artists to withdraw their work to further that end. At that year’s Biennial, Kline showed a series of framed black and white, LED-lit photographs, including images of a Ronald Reagan statue and Twitter’s San Francisco headquarters. Water pumped through the frames slowly erases the images of political and corporate power until, blank, they are replaced by fresh photographs. I like these works.

ey dissipate their own obviousness, launder their meaning, restate and re-e ace themselves: futility and plainness flip to perseverance and emptiness, and back again. Still, some moments call not for complexity, but directness: Kanders stepped down six days after eight artists withdrew from the show. (Kline was not among them.)

Kline’s work is most a ecting, and paradoxically at its bleakest, when it is most hopeful. In Hope and Freedom (2016), Kline’s video of a deepfaked Obama, the President makes very un-Obama-like demands for systemic change; and in Kline’s faux commercials for universal basic income, Universal Early Retirement (Spots #1 and #2) (2016), also included in “Unemployment”, diverse beneficiaries, freed from need, pursue their interests without thought for monetary gain. ese visions, so dissonant with our reality, garnish Kline’s mournfulness with a rich, twisted optimism, like a dollop of caviar dropped on a Lunchable.

As one-liners go, “hope” still lands.

Paul McAdory is a writer and editor from Mississippi, US. He lives in Brooklyn, NY.

“Josh Kline: Project for a New American Century” is on view at the Whitney Museum, New York City, through to August 13, 2023.

Opposite Josh Kline, Desperation Dilation, 2016. Collection of Bobby and Eleanor Cayre.

Courtesy: © Josh Kline and 47 Canal, New York.

Photography: Joerg Lohse

18 MAY 17–21, 2 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK EXHIBITIONS

Since its founding in 1976 by a group of individuals including Lucy Lippard, Sol LeWitt and Pat Steir, New York’s Printed Matter, Inc. has built a reputation as the world’s leading non-profit organization dedicated to artists’ books. Its main location just a 10-minute walk from the fair, Printed Matter Inc. will also host a pop-up on the ground floor of e Shed throughout the duration of Frieze New York.

For 18 years, artist Mary Lum served on the Printed Matter board of directors, and in 2012 joined its advisory council. Herself a maker of artist books, her multidisciplinary practice is rooted in urban living, drawing influence from Cubism, the Russian Constructivists and the psychogeography of the Situationist International. Wandering through cities to mentally collect images of overlooked details of the cityscape, in her collages Lum reconfigures these fragments into new abstract forms with fresh meanings. Professor Emerita of painting and drawing at Bennington College, Lum is the 2023 recipient of the College Art Association’s Distinguished Teaching of Art Award.

READ THE ROOM

Volcano Manifesto, 2022

Cauleen Smith

Describing a manifesto as equal parts invitation, pronouncement, rant and dare, Cauleen Smith puts the words out there and then tests herself against them. Volcano Manifesto begins, “Your rock, my volcano.” A tale unfolds of a personified volcano (she) destroying our present world and dismantling capitalism—proposing to remake the world where Man is not at its center. “ e volcano obliterates all boundaries and collapses all orders. If the lava oozes over your dotted line, do we share?” A Weather Channel image of moving lava about to overtake a municipal fence sets up the inevitable and welcome destruction. Interspersed with Smith’s sharply rendered thoughts are quotes from Fred Moten, Trinh T. Minh-ha, W.E.B. Dubois and others, all of which drive forward and add to the story. e book ends with a refrain from Édouard Glissant, “our boats are open and we sail them for everyone.” e stakes are high, and Smith’s voice proves them out once again.

Tree Identification for Beginners, 2018

Yto Barrada

Tree Identification for Beginners is a rich, rewarding book that can scarcely contain the enormity of what is documented within. It’s a lovely thing to handle, with its newsprint pages in green, grey and pink sections that collect typewritten texts, interviews, historic photos, maps and charts, performance notes and film stills. A way to reinvest in Yto Barrada’s contribution to Performa in 2017—a stop motion animation with recorded sound, accompanied by a live performance—the book functions as both a catalog, as well as a stand-alone work of art. e performance and book tell the story of the artist’s mother, Mounira Bouzid, who made her first visit to the US in 1966 as part of a group of African students participating in the Operation Crossroads Africa program. Barrada uses archival materials, including invitations, publicity, press clippings, photos and her rebel mother’s unreliable narrative, in order to illuminate the political and social undertones of this trip. e story is important, and made even more so by Barrada’s compelling, original telling.

Sixteen Drawings, 2017

Laylah Ali

e people portrayed in Laylah Ali’s book of mixed media drawings seem to barely tolerate our gaze. eir expressions hover between dissatisfaction and resignation, no wide smiles nor faces contorted by anger. e elaborate hairstyles and head coverings, wildly patterned clothing and some boldly shadowed eyes, announce people we must contend with, rather than hope to understand. Still, it’s a conversation. ey stare just over our shoulders or o into space, inviting us to ask questions about what is actually below the surface.

Two of the figures wear t-shirts with words that give us a clue: “comfort with rage” and “Lies”. As we page through these beautifully drawn portraits we ask, but not out loud, “Is this someone I know?”

A Better Life For e Workers (I), 2021

Jen Liu

e pink, shiny, blank outside of Jen Liu’s

A Better Life For e Workers (I) is perfectly calibrated to cover the incredible document found inside. Originally a 2013 training manual for Worker Empowerment, a Hong Kong based NGO education program for workers in Shenzhen, the text “provides a framework for understanding the psychological, political and legal issues shaping industrial work life in modern China.” e original Chinese version appears under one cover and on turning the book over the reader finds the text translated (by Liu and her family) into English. In undertaking this translation, Liu is not asking us to indulge in the

“spectacle of su ering”, but rather to recognize likeness and experience solidarity with Chinese workers, and perhaps all workers who are caught up in the globalized industrial system. Overlaid on both the original and the translation is a flip-book picturing a hand that at first seems to hold the volume open, and then is gradually overtaken, x-rayed, attacked, changed and obscured by mysterious pink orbs. e book is designed to reflect themes of hiding in plain sight and dissolving visibility, and in turn speaks to the shared fate of workers, labor activists and NGOs since 2013, and since 2020 in particular.

Loom Book, 2022

Chang Yuchen

Chang Yuchen’s Loom Book is an invitation to a handmade world where everyone knows that readers are makers. It invites the reader to participate in the act of weaving, as the pages of two independent but intertwined sections are revealed through direct interaction. By repeatedly lifting the pages of one section and turning those of the other, the reader recognizes the warp and weft of loom weaving and the process of creating patterns. In 2018, Chang discovered e Book of Looms (first published in 1979), a historical survey of weaving devices, and was inspired to interpret the development of looms and the origins of weaving by making simple, descriptive drawings as a form of notetaking. One section of Loom Book contains these clearly articulated drawings, one loom per page, while the other section describes the drawings with concise, vertically written captions, placing each loom in a time period, culture and geographical location. rough the reader’s manipulation of the interlaced sections, a history of the loom is rewoven, and a new story about language is told.

Bonus Pick:

Any zine from BlackMass Publishing

Founded by Yusef Hassan in 2019, BlackMass Publishing is a New York based collective and independent press that publishes the work of Black artists, often through improvisatory processes of research, looking, listening and making.

FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK NON-PROFITS 2 0

Below Mary Lum at Printed Matter, Inc., New York, 2023 Photography Tim Schutsky

MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 Mary Lum is an artist and educator. She lives in Massachusetts, US. Visit the Printed Matter, Inc. pop-up store in the Lobby of e Shed throughout Frieze New York. www.printedmatter.org

As the venerable Printed Matter, Inc. returns to the fair, artist Mary Lum selects five essential artists books.

As winner of the new Frieze Artadia Prize, artist Jessica Vaughn is undertaking a major commission at the fair, mapping the vicissitudes of American life through its postal system. Profile by Folasade Ologundudu.

POSTING UP

“How do we live, breathe, operate and situate ourselves in the world?” artist Jessica Vaughn asks during our recent conversation, ahead of her upcoming commission at Frieze New York for the Frieze Artadia Prize, to which the idea of situating—“to place in a site, situation, context, or category: locate”, as defined by Merriam-Webster—is key.

Founded in 1999, Artadia is a grant-giving body, defining its mission as supporting artists at pivotal moments in their practice. Reaching artists throughout the US, Artadia has awarded over US$6 millon in unrestricted funds to nearly four hundred artists over the past two decades: in smaller and larger art hubs across the US. In 2018, the Brooklyn-

based Vaughn was one such recipient, awarded US$10,000 in unrestricted funds, which she used to conceive of new projects and pay for studio space in New York City. In 2022 she was invited, along with all other New York area artists who had previously received Artadia funds, to submit proposals for a work to be realized at Frieze New York for the Frieze Artadia Prize.

Vaughn’s winning entry was selected by a pair of external jurors: SohrabMohebbi, Director of New York’s SculptureCenter and the Director of Miami’s Perez Art Museum, Franklin Sirmans.

ough it constitutes a new partnership between Frieze and Artadia, the Prize continues a tradition of commissions awarded to artists at Frieze New York,

Opposite Jessica Vaughn in her studio in New York, March 2023

including Lauren Halsey in 2019—whose new work for the Roof Garden Commission at the Met will be on view during Frieze Week and, in 2018, Kapwani Kiwanga, who will represent Canada at next year’s Venice Biennale.

Vaughn’s work explores the systems that shape our lives, inquiring into the social fabric of America to reimagine the ways its products are saturated with cultural histories. For Vaughn, the seeming mundanity of even the most everyday objects holds the potential to reveal profound meaning. Materiality is critical. Her practice often transforms and repurposes existing, mass-produced objects, using the commonplace to create richly layered works that reflect the complexities

of place, production and use. “When I start to use a material, I begin from the point of trying to understand it in a social and historical context,” she tells me. e impetus for Vaughn’s Frieze Artadia Prize commission began during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the pandemic spread, the conditions of late capitalism were exacerbated; economic inequalities increased and racially motivated attacks by both the state and citizenry broke out, causing worldwide outrage. At the same time, with so many in-person services not working, reliance on postal services increased.

Beginning during the pandemic and lasting until this year, Vaughn sent letters via the US postal service to a selection of locations, marking sites of “leisure,

22 MAY 17–21, 2 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK NON-PROFITS

Photography Fumi Nagasaka

commerce and places where acts of violence occurred,” she says. She used security envelopes, since, as she explains, “the interiors of those envelopes are synonymous with debit and credit in the US.” Enclosing a generic message inside, Vaughn marked the envelopes with intentionally incorrect information—a wrong number or slight spelling discrepancy—so the mailed letters would be subsequently sent back. e letters returned to Vaughn had accumulated numerous handwritten and digital markings, revealing locations they had passed through on their journey through the infrastructure of the postal system: “Residual traces,” she says, “aligning past, present, and future.” ese traces are captured in over 30 images of the returned

envelopes, which Vaughn then printed digitally onto strips of linen and canvas, assembled at the Shed for Frieze New York 2023 in the form of the final work.

e format of these large-scale works—each printed strip is nearly two and a half meters long—hung above eye level across two walls, recall aspects of traditional landscape painting, a genre in America typically made by and for white males, depicting the nation’s land in terms of economic prosperity and wealth extraction. Vaughn instead reframes the American landscape, mapping sites from Walt Disney World, Prospect Park, o ces in Silicon Valley, malls and the gated community in Sanford, Florida, where Trayvon Martin was murdered in 2012.

“I was interested in all of these sites, which when considered together, constitute a conceptual landscape that reorients how American life is pictured, felt and structured,” Vaughn explains. While her conceptual landscape is one soaked in persistent violence—it includes the sites of public acts of brutality such as the Pottawatomie massacre of 1856 and the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965—it deliberately also includes sites associated with leisure and commerce as well: a combination that is at once repulsive, yet frighteningly familiar to citizens today.

Vaughn’s piece reflects not only on our collective history (the power to establish post o ces was enshrined in the constitution, and the mail’s scope was

discussed by the founding fathers), but also the present moment. Shining a light on the polarizing experiences of what it means to live in a society marred by financial exploitation, violence, racial inequality and a hypocrisy that so often turns a blind eye to its own inequities, the America she maps is also a place where we can contend with precisely these problems.

23 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK NON-PROFITS Folasade Ologundudu is a writer and multidisciplinary artist. Her writing includes art criticism, profiles, essays and interviews. She is the founder of Light Work , a creative platform rooted at the intersection of art, education and culture.

e Internet of ings (2020-2023), Jessica Vaughn’s commission for the Frieze Artadia Prize, is on view at Frieze New York ( e Shed, Level 4) throughout the week.

New Yorkers are facing historic levels of homelessness. Presenting at this year’s fair, a purchase from the Artist Plate Project is a small but meaningful step towards the deep, systemic change desperately needed to end the crisis. What’s even better: each plate features work by a world-renowned artist.

DINNER SERVICE

More people are homeless in New York City now than at any time in history since the Great Depression. is dire statistic is reported by the Coalition for the Homeless, whose analysis of shelter census reports from the NYC Department of Homeless Services and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development finds 72,000 people slept in the city’s shelter system in January of this year: nearly 23,000 of them children.

e Coalition for the Homeless, the oldest advocacy and direct service organization in the US, is dedicated to helping individuals and families experiencing homelessness, providing more than one million New Yorkers with a way o the streets since its inception in 1981.

One major source of funding was the organization’s annual gala, ArtWalk NY. When COVID-19 made such events

unfeasible in 2020, a new lifeline arose in the form of the Artist Plate Project, founded and curated by consultant and advisor Michelle Hellman.

A partner of the New York gallery

A Hug From e Art World, and a member of the Coalition’s advisory board, Hellman had noted the success of a limitededition plate produced for the 2019 gala by artist Katherine Bernhardt. “In lieu of yet another virtual auction,” she told the Art Newspaper in 2020, “the idea popped into my head.” Why not extend the e ort, inviting more leading contemporary artists to create their own limited-edition plates, whose sales would directly benefit the homeless. Produced by Prospect, the first series included plates by Derrick Adams and Cecily Brown, among others. e project has reportedly raised over US$4.5 million for the Coalition.

Opposite

Left to right, top to bottom: Alice Neel; Albert Oehlen; Amoako Boafo; Peter Beard; Dana Schutz; Philip Guston; Glenn Ligon; Virgil Abloh; Ed Clark; Henry Taylor; Robert Nava; Ed Ruscha; Joel Mesler; Jonas Wood; Katherine Bernhardt

At Frieze New York 2023, the Artist Plate Project will launch over 40 new limited-edition plates by world renowned artists including Ed Ruscha, Lorna Simpson and Hank Willis omas. Funds raised will directly benefit the Coalition for the Homeless, providing food, crisis services, housing and other critical aid to thousands of people experiencing homelessness and instability. Each artist’s dinner plate is an edition of 250 priced at just US$250, meaning the purchase of one plate can feed up to 100 individuals.

In the Coalition for the Homeless’s view, the solution to homelessness in the city must be systemic: their 2022 State of the Homeless report urges attention to improved shelters, mental health services and, crucially, a ordable housing—which, along with su cient food and the chance to work for a living wage, they hold to be

“fundamental rights in a civilized society.” In the meantime, we can all play our part—simply by purchasing an artist plate, you’ll help provide lifesaving relief to thousands of New Yorkers in need each and every day.

24 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK NON-PROFITS

Visit the Artist Plate Project’s presentation on the 2nd Floor at Frieze New York or online at ArtwareEditions.com. www.coalitionforthehomeless.org

Take Notice Women Photographers Come into Focus

Among the jaw-dropping findings in the most recent Burns Halperin Report, compiled by the art journalists Charlotte Burns and Julia Halperin, is the fact that “women artists account for just 3.3% of all fine-art auction sales since 2008.” Indeed, the auction sales from 2008–22 for just one male artist–Pablo Picasso–reached US$6.23 billion, “exceeding the combined sales of all female artists in the database by US$30 million.” While some arts organizations have attempted to improve historical disparities by acquiring more pieces by women and presenting them in formal settings, institutional collections also evince the persistence of gender inequity: according to an article published in the Public Library of Science, a 2019 survey of 18 renowned American art museums found that 87% of artists represented in their collections were men.

is is the situation that this year’s Deutsche Bank presentation at Frieze Week New York hopes to engage in dialogue, highlighting the work of women photographers from around the world, including K8 Hardy, Cecilia Paredes, Alessandra Sanguinetti and Xaviera Simmons. “Early on [we wanted to] focus on portraiture,” Britta Färber, Global Head of Art at Deutsche Bank, said in an interview. “Showing a di erent angle of life from female artists was very important to us.”

Since its inception in the late 1970s, Deutsche Bank’s collection has sought to acquire a variety of works on paper, spanning drawings, collages and photographs. e collection initially focused on works on paper created after 1945 from German speaking countries, but since the late 1990s the perspective has become far more inclusive, and it now features hundreds of pieces by female artists from around the world. e works on view at Frieze are all currently hung in the Deutsche Bank Center on Columbus Circle in New York.

“[ ere has been] a stronger focus on women artists in recent years,” Färber wrote in a 2018 collection essay. is, she asserts, “is inextricably intertwined with

the increasingly global focus of the collection. e increased attention paid to female practices is bound up with the move away from a Eurocentric perspective on contemporary art. e numbers alone document this. Today, a total of 669 women artists from 62 countries are represented in the Deutsche Bank Collection.” is year’s presentation at Frieze in New York continues to speak to these questions, putting work created by women to the fore. One of the photographs on view—Into the New Sea (Nomad) (2009) by Xaviera Simmons—depicts the artist wandering through a wheat field. She stands to the right side of the frame, her head— which is covered by a sa ron-colored shawl that she clutches with both hands—is turned to the side. It’s di cult for the viewer to determine exactly what the subject

is thinking, and we’re left to create our own stories about how this character relates to the world around them. “I was really thinking about the history of painting and photography as it relates to the landscape,” says Simmons. Later she adds, “For me, there’s some mystery in that photograph, but it is part of a larger series of works that are in conversation with the history of painting and the history of figures inside landscapes: [it asks] which characters can live in certain landscapes and which characters can’t.”

Paredes’s work also contemplates themes of nature and the female body, albeit in di erent ways. Two of her pictures in the exhibition—Asia (2009) and Paradise Hand (2009)—depict camouflaged bodies set against ornate patterns of flowers and foliage. e latter shows an

outstretched hand painted in the same design as the wallpaper behind it, creating an interesting tension between foreground and background, prompting us to ask questions about where these designs came from and how we feel in our surroundings. “Paradise Hand is part of a series called ‘Elusive Paradise’” Paredes explains. “It sits within the ‘Landscape’ series where I talk about our search for happiness and how elusive it can be […], while not recognizing it was already there and we didn’t notice.”

ough many of the works on view prompt similar questions about nature and the body, the distinct range of photographs on display speaks to the multiplicity of perspectives from female artists. Some of these works depict their subjects looking straight into the camera, others show them turned away from the viewer, while some are devoid of a recognizable human presence. Such diverse portrayals of women—created by women—challenge the history of female portraiture, which in the words of K8 Hardy “has been largely in the hands of men and t he male gaze”.

“If curators are the ones who make the decisions, and if this group of people is not diverse, then the exhibitions will not be diverse either,” Färber said. “ is is something that we are really committed to, and why we partnered with Frieze to develop an emerging curators fellowship for curators from a BIPOC-background in key art institutions.”

26 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK FRIEZE PARTNER: DEUTSCHE BANK Isis Davis-Marks is an artist and writer. Her articles have been published in the Smithsonian magazine, Cultured , the Art Newspaper and elsewhere. She is based in Brooklyn, NY.

Above Cecilia Paredes, Paradise Hand 2009. Courtesy: the artist and Echo Fine Arts

To learn more about the exhibition in the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounge, watch Art:LIVE, a video report from Frieze New York, featuring accessible expert insights from artists, gallerists, collectors and art professionals: frieze.com/ artlive-new-york-2023

The Struggle of Memory

Deutsche Bank Collection Part 1 April 19 –October 3, 2023 Samuel Fosso, Untitled (Detail), not dated © Samuel Fosso, courtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

On the first night of my first visit to Mexico City, in 2020, a fellow guest at a dinner party asked if I would take in any other parts of the country during my stay. When I confessed I wouldn’t—I had less than a week to see the capital—the guest reflected, ruefully, that: “if you haven’t seen Oaxaca, you haven’t really seen Mexico.”

For those who, like me, are yet to visit Oaxaca (or Oaxaca de Juárez, to give it its full name), there’s a chance to sample a taste of the city’s cultural flavor at this year’s Frieze New York, in the form of the Maestro Dobel Artpothecary installation at the fair. Titled “Oaxaca: A Lens on Tradition & Innovation”, this presentation features works produced by two Oaxacabased creatives: architect Marissa Naval and design studio founder Javier Reyes, celebrating the city’s tradition of crafts and making, and its thriving community of makers and designers. Past iterations at Frieze of the Maestro Dobel Artpothecary, billed as “a creative platform that spotlights and celebrates Mexican art and hospitality”, have presented icons of Mexican modernist furniture designs, in collaboration with Clásicos Mexicanos, and works by Latinx contemporary artists such as Eduardo Sarabia.

“I was visiting family in Oaxaca for the first time in 2017, and saw that this was a Mecca for craftsmanship techniques,” explains Javier Reyes, founder of studio rrres, which has operated from the city since early 2018, producing woven objects, textile hangings, rugs and ceramics.

Born in the Dominican Republic, Reyes was at that time based in Barcelona, but was so inspired by his encounter with the craft practices in Oaxaca he spent a year traveling back and forth from there, to “research the city’s history and explore museums to learn about its craft and culture”, before relocating full time to the city, where studio rrres now occupies an ochre-colored traditional building in the city’s Barrio de Jalatlaco. “It’s structured almost like a showroom,” Reyes continues. “Everything is made custom-ordered to ensure that all of my work is ethically sourced and produced. I host workshops for local Oaxacan artisans, where everything is made completely from scratch using our traditional methods.”

History In e Making A Maestro

showcase

e active presence of distinct indigenous traditions is essential to the identity of both the city of Oaxaca and the state of which it is the capital. Due in parts to its rocky geography, the territory was historically isolated from the centers of colonial government, meaning the cultural traditions and identity of the region’s indigenous peoples such as the Zapotec and Mixtec remained relatively intact.

Today, about a third of the state’s population speak indigenous languages— half of all Mexico’s indigenous language speakers. e sense of a proudly Zapotec identity is apparent not only in the crafts of the region but in the work of its visual artists—including some of Mexico’s most esteemed, like Rufino Tamayo and Francisco ‘El Maestro’ Toledo. Reyes observes that “Pre-Hispanic practices and strong, resilient culture, dating back generations, are still very alive in Oaxaca. Filled with diversity, the landscapes and people have an inspiring history which has shown to be incredibly influential to their artistry.” Despite this, he does not see the work of studio rrres as backward looking in any sense. For the Artpothecary installation at Frieze New York, Reyes presents a new collection of weavings and textiles in wool, cotton and palm, as well as ceramics, based on the geometry of modernist architecture. “We wanted to bring something authentic and di erent,” he says, “a modern view and not just what one would typically think of regarding Oaxacan architecture.”

Architect Marissa Naval also brings an unexpected angle to Oaxacan tradition. Born and raised in Mexico, she studied architecture in Monterrey and then at Columbia in New York, working for some years at the practice of the late ChineseAmerican I.M. Pei. But it was a summer apprenticeship in Kyoto, Japan in which she began to forge a new path. “I had the privilege of serving as an apprentice to a highly skilled master carpenter,” she explains, “and discovered an authentic artistry that connected both Japan and Oaxaca—a creativity that went beyond the surface.” In the ancient traditions of Japanese woodcarving, in which formally complex structures can be assembled solely through hand tools, eschewing fastenings like metal nails or glue, Naval

saw a parallel with the understated intricacy of Oaxacan crafts. “ e artists are anonymous,” she continues, “but have the ability to draw inspiration from a tree, t he sky or a rock—radiating a sense of mysticism in their works.”

It’s intriguing to think about the cultural connections between Japan and Mexico: from the way that the painted folding screen known in Japan as byōbu arrived via colonial trade in the 17th century and became the Mexican biombo; to how, in the early 20 th century, the JapaneseAmerican Isamu Noguchi produced an extraordinary sculpted mural in a now somewhat dusty corner of the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market. What are some of the continuities between the two cultures, I ask Naval. “We both love food, nature! And some drinking!” she responds. “It’s actually pretty spectacular,” she continues, “how the Beckmann family, who are the owners of Maestro Dobel Tequila, helped introduce tequila to Japan and now there’s a growing interest and popularity in tequila and other Mexican spirits in the country.”

For Frieze New York, Naval attempts to convey this sense of harmonious dialog between distinct local traditions through a bar structure and furniture, inspired by the form of the traditional Zapotec house, constructed according to Japanese

carving techniques from Mexican cedar wood. As with Reyes, working with specialist local artisans is central to Naval’s practice. “ e people that I work with are very important,” Naval says, “as we are all very much passionate about our work, each one with the subject that corresponds to us, being honest and respectful with the materials, and our past.”

is approach to heritage and tradition is clearly one which appeals to Maestro Dobel, who not only pride themselves on being an eleventh-generation tequila, but credit this accumulated knowledge with their ability to innovate: producing the first “cristalino” tequila in 2008. As with Reyes and Naval’s work, being enmeshed in tradition is not an obstacle but a path to new creation. As Reyes notes: “We’ve cultivated traditions of the past into our pieces, while integrating an innovative perspective towards the future.” ¡Salud! to that.

28 MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

PARTNER:

DOBEL TEQUILA Visit the Maestro Dobel Artpothecary, featuring works by Javier Reyes and Marissa Naval, at the DOBEL Tequila stand on Level 6 of e Shed throughout Frieze New York. Matthew McLean is Editor & Creative Lead at Frieze Studios. He lives in London, UK.

FRIEZE

MAESTRO

Above Maestro Dobel Tequila Bar (rendering) at Frieze New York 2023 by Marissa Naval

Dobel

reveals that heritage is alive and well in the craft scene of Oaxaca

onefi homeowners earned combined $6.8 million in 2022 THE EXPERTS IN VACATION RETURN TO PEACE OF MIND | ADDITIONAL | END-TO-END SERVICE FLEXIBILITY | DEDICATED MANAGEMENT VETTED GUESTS | INSURANCE ASSETS NEW YORK • LOS ANGELES • LONDON • PARIS our team to learn more onefinestay.com/list-your-home homes@onefinestay.com +1-855-553-4954 *Image taken from a onefinestay home; a view enjoyed by guests

As Chair of YoungArts, Sarah Arison oversees a system of invaluable, long-term support to young artists and arts organizations across the country. She discusses getting advice from Agnes Gund, assembling her “very personal” collection, and why she’ll always be drawn to New York’s endless energy.

YOUNG HEARTS RUN FREE

SARA HARRISON

I wanted to begin by asking you about YoungArts, an organization founded by your grandparents just over 40 years ago. Could you tell me about the work you do?

SARAH ARISON

So my grandparents founded YoungArts in 1981, and the impetus was that my grandfather had wanted to be a concert pianist, and he did not find the support from his family, the educational community or the community at large. eir response being, “go get a real job.”

When he reached the point that he was able to give back, he wanted to create something so that no young, talented, aspiring artist had the experience he had. He wanted them to have the resources they needed to pursue an education and a career in the arts and so, my grandparents founded YoungArts.

For decades, the organization was really focused on that first critical juncture in a young artist’s life, from high school to college, when they are having to decide

where they’ll go to school, what they’re going to study, and if they have the scholarships and financial support to pursue that. ere really was not—and honestly is not—another organization that addresses that early critical juncture across all ten artistic disciplines: performing, visual and literary arts.

Every year, approximately 170 of the most accomplished young artists from across the country, in all disciplines, come to Miami for National YoungArts Week—a week of masterclasses with luminaries in each field. So, Mikhail Baryshnikov might do Dance, James Rosenquist the Visual Arts, and Renée Fleming Voice. ese young artists have an opportunity to meet and collaborate with artists of other disciplines and then they receive cash awards from us.

SH And five years ago you took over as chair. What changes have you implemented since taking on that role?

SA So, since I took over as chair, we’ve been a lot more focused on the lifetime

of an artist. We really want to identify these young artists as we always have done, amplify their potential and then invest in their lifelong creative freedom. And in terms of a lifetime of support that means everything from mentoring, networking and community, to funding and providing physical space.

But one organization cannot do all of that. So, while YoungArts remains unique in working with artists across all disciplines, there are wonderful organizations out there focused on particular fields, that are addressing critical junctures and have been doing it for decades, and are really phenomenal at it.

So, I started setting up cultural partnerships, and a great example of that is Sundance. About six years ago, Sundance launched the Ignite program, which was for filmmakers aged 18 to 25. I said, we have the greatest filmmakers in the country, aged 15 to 18, can we funnel them into your new program? is way, they are going to the best possible place they can.

Opposite Sarah Arison in her home in New York, March 2023

On wall, clockwise from left: Robert Longo, Untitled (Bill & Bjorn)

2014; Jos Gruyter and Harald ys, Objects as Friends, 2011; Oliver

Je ers, Not Too Deep, 2018;

Zoë Buckman, Champ Embroidery Edition, 2017; Ying Ge Zhou, YGZ

181–#161, undated

Photography Caroline Tompkins

It has become about creating an ecosystem—working together to support artists at di erent points in their lives with their di erent needs.

SH So, for Film you’ve partnered with Sundance, and for the other disciplines, who have you collaborated with?

SA With Dance, we’ve partnered with Jacob’s Pillow. In the visual arts we’ve done shows at MoMA PS1. For music, we work with the Musical Instruments Department at e Metropolitan Museum of Art. We collaborate with Joe’s Pub in New York and the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA. We also have some artist residencies, like Fountainhead Arts in Miami, Florida.

SH Beyond this you are President of the Arison Arts Foundation, and serve on an incredible number of boards.

SA Yes, so, Arison Arts Foundation was founded by my grandparents to ensure the continuity of the two bodies they founded, YoungArts and New World Symphony, which they set up in 1987,

31 COLLECTING MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

which is the largest training orchestra for young people in the US. So, it is in my capacity as President of Arison Arts Foundation that I serve on all the boards that I do, which right now total 11!

SH at’s really a lot! How do you balance that? In terms of fundraising, I imagine you are often contacting the same individuals or companies that are aligned with the arts.

SA I think one of the good things is that I serve on boards that are across disciplines: whether it’s President of the American Ballet eatre, or MoMA and MoMA PS1, or the Lincoln Center. People ask, aren’t they constantly competing with one another? But my favorite thing to do is to find the synergies between organizations and figure out how they can work together, because we are in a field where resources are so limited. rough collaboration, organizations can save a lot of time, money and energy, and also increase the impact that they can have.

SH Obviously you got a lot from your grandparents in terms of your involvement in philanthropy and role as a patron. How did they influence your own journey as a collector, and how has that evolved?

SA I was very influenced by my grandparents, but also by Aggie [Agnes] Gund, who is another huge mentor for me.

I don’t even necessarily consider myself a collector all the time. But first I have nothing in storage, so everything is on my walls, and I also follow Aggie’s rule of never selling a piece by a living artist.

My collection is a history of my life and career, and my work with all of these organizations and all of these artists. I would say about 95% of the works that I own are by artists who I have worked with closely, including YoungArts alumni or YoungArts mentors, or people that have shown in Greater New York at MoMA PS1.

So, it’s a very personal collection. I really love that with every piece there’s a story behind it, and that, in many cases,

I met the artist when they were very young, and I’ve been able to follow their career. SH You obviously support far more artists than you can collect. What’s the impetus that makes you want to take that step and own something by them and live with it?

SA People ask me all the time, what should I buy now? What’s a good investment? But you can’t think of it in that way. If that’s the way you think, go buy a poster, have it framed and call it a day, because you should not be collecting art. But I do say, buy what you want to live with, buy what you want to see on your walls. Every piece that I have I fell in love with, or I felt like it was a very important moment in the life or career of the artist, or a body of work that was reacting to important times.

Also, so many not-for-profits use art as fundraisers, and Aggie’s organization, Studio in a School, is a great example. ey only do a benefit every five years, but they do sell works: this year, they had a Martin Puryear print; a couple of years ago one

Above, left John Baldessari, Big Catch 2016

Above, right Zoë Buckman, e Fucking Master 2019

Opposite

On wall: Taryn Simon, Poolside, Tel Aviv Mini Israel, Latrun, Israel, 2007

by Teresita Fernández; and before that one by John Baldessari. I’m not going to buy an original Baldessari, but I can have a fantastic print and know that it’s going to support an organization that does brilliant work.

SH And have you made any acquisitions recently?

SA I bought a piece by a YoungArts alumnus named Mark Fleuridor and also something by Derrick Adams, who is an amazing artist, a YoungArts board member, mentor and dear friend, who curated a show of Mark’s work on the YoungArts Campus last year. Also, at the UNTITLED fair in Miami this year, I bought a piece by Jean Shin, who is a wonderful artist— also a YoungArts alumna and mentor, and on our board. She did an incredible project in Olana, near Hudson, about the hemlock trees that have been cut down. I had been up to visit it, and then in Miami a gallery had some smaller works related to this project. Also, I recently bought a Sadie Benning, who was an

32 COLLECTING MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

33 COLLECTING MAY 17–21, 2 0 23 FRIEZE WEEK NEW YORK

artist I first saw in Greater New York at MoMA PS1, ten years ago. I fell in love with her work then, and I bought a piece from her last show.