6 minute read

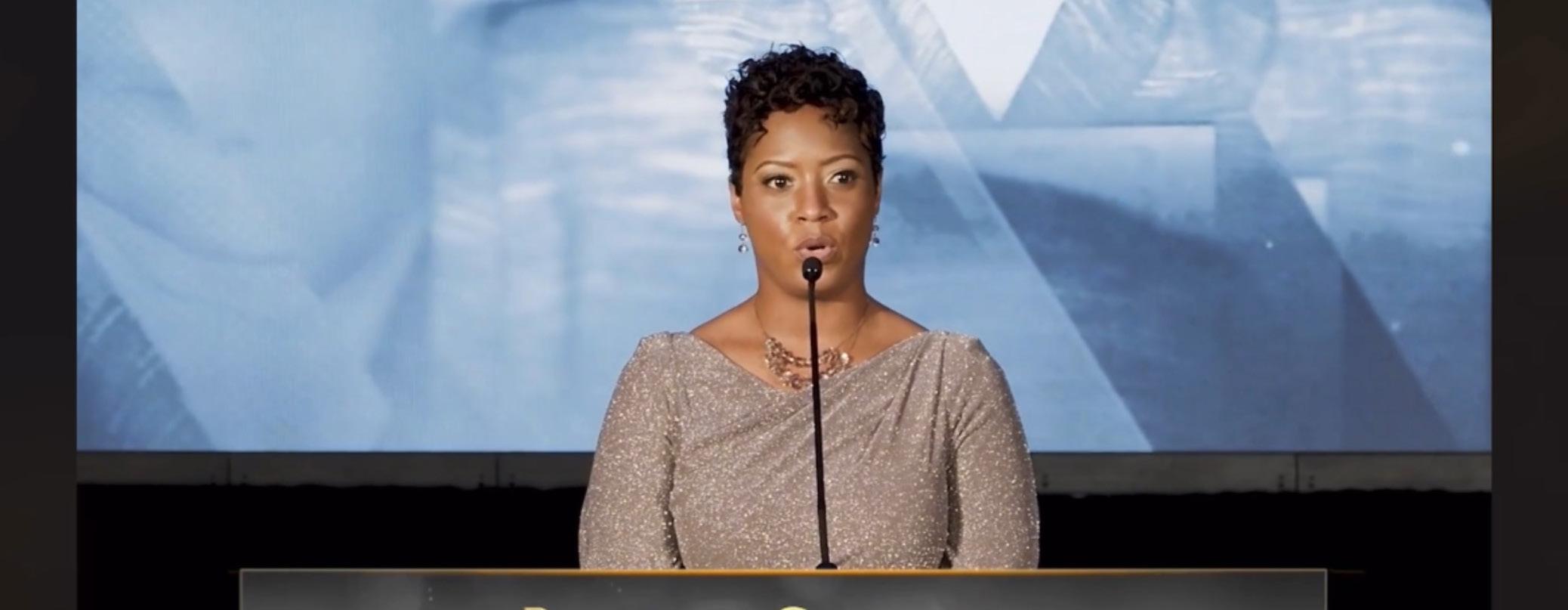

Dr. Rachel Sherman

Dr. Rachel Sherman Takes to the Street to Heal Her Community

A portion of the Frontier Nursing University mission statement includes the phrase “to prepare competent, entrepreneurial, ethical, and compassionate leaders in primary care to serve all individuals.” While that refers to a typical healthcare setting and caring for one’s patients, it also conveys a different, even deeper message -- a message about being an ethical and compassionate leader in one’s community and ensuring equitable care for all people.

Advertisement

That’s a daunting task that no one can do alone, but it takes a leader to inspire and organize the goodwill and intent of others who share the same idea of “serving all individuals.” So it was, in the tumultuous spring and summer of 2020, that Dr. Rachel Sherman, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, Class 36, came to help heal a community by serving on the front lines of both the predominant battles facing the country. She worked 10- to 12-hour shifts at Prince George’s Hospital in Prince George’s County, Maryland, the hospital with the highest number of COVID-positive patients in the state. After long days where she might lose half a dozen COVID-19 patients in a single shift, she would organize and attend daily social justice protests.

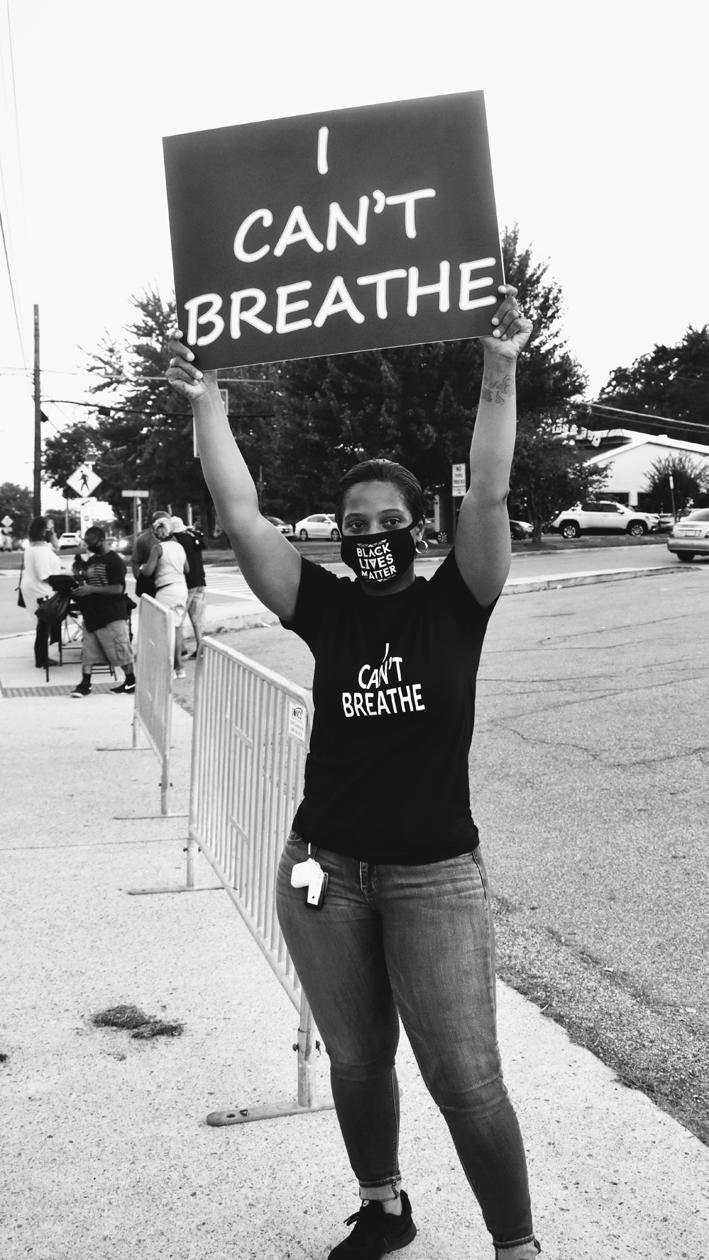

The protests began in June 2020 in response to an incident in a local restaurant. The restaurant owner refused service to a Black customer wearing an “I Can’t Breathe” t-shirt. In addition to a boycott of the restaurant, daily protests were held, with Sherman serving as a leader and organizer. She used social media to inform the community about the demonstrations and their importance in bringing about change.

“Initially, the goal was to be out there every day,” Sherman said. “We set a time to protest daily from 3 p.m. to 9 p.m. I had a co-organizer, and then we formed a coalition with other groups in the area. For the first week, we were out there every day.” As if the long work shifts and protests weren’t enough, Sherman also has two children who were homeschooling during the pandemic and was a student herself, working toward her DNP at Frontier. Organizing and prioritizing each of those significant parts of her life was seemingly impossible.

“I remember thinking, ‘How in the world am I going to implement my DNP project and do daily protests?’” she said. “We had an organizers’ meeting and came up with a schedule. I had Tuesdays and Saturdays and, because the days were longer and hotter, we changed the hours from 3 to 9 to 5 to 9 so we weren’t there in the dead of the heat. If it weren’t for my co-organizers, it really would have been a struggle. So we had this schedule, and then we had weekend events to blast the daily boycott. If it wasn’t for both my team on my project side and my team on the protest side, there’s no way I would have been able to keep that up.”

While the daily protests ended after about five months, the work continues and includes what Sherman describes as occasional “pop-up protests.”

“The protest is still ongoing,” Sherman said. “While we are not outside of the restaurant daily, we are using our social media platform to continue our demonstration.”

-- Dr. Rachel Sherman

It has been a long year since that initial protest, but the results, while slow at times, are encouraging.

“We are seeing that local businesses are changing their poor practices,” Sherman said. “We have seen a sense of renewed ownership of the community. Churches, local leaders, and residents are showing that they care. The restaurant has reopened, but many patrons have not returned.”

Building upon the momentum, Sherman and many others involved in the protests and local leadership are leaders for change in other areas of the community as well.

“We are using our advocacy group ‘We The People of PG County’ to bring awareness to the discriminative zoning laws, issues with the public school system, poor nutrition and health care services, and lack of access to economic resources,” said Sherman, who was presented with the Rosa Parks Award for Excellence in Community Activism at the District 9 Prince George’s County Day of Service Awards in January.

Just like the community around her, Sherman’s life has changed in many ways in the past year. She completed her DNP and graduated from Frontier. She left the hospital and is now DNP clinical faculty at Frontier. It is a role that figures to suit her well as she can relate to students’ scheduling issues and their desire to serve their communities while caring for their own families.

“I have a newfound appreciation for time management and having a strict schedule,” Sherman said.

As she strives “to prepare competent, entrepreneurial, ethical, and compassionate leaders in primary care to serve all individuals,” Sherman likely will point to her own DNP project and the lessons she learned from it.

Her quality improvement project, which was converted to a virtual platform due to the pandemic, was “Advance Care Planning -- A Patient-Centered Approach to Community-Based Advance Care Planning.” Her social activism heightened her social media presence, and when she shared that she was offering a free advance care planning project, the volunteers rolled in. In total, 85 participants signed up for the project, via which Sherman intended to help educate the participants about advance directives.

While it wasn’t the project she originally planned to do, it was quite fitting in

-- Dr. Rachel Sherman “One of the more recurring themes was patients did not trust the local medical system. They would say, ‘I don’t trust that hospital.’”

-- Dr. Rachel Sherman

many ways. The findings were a powerful reminder of the importance of removing inequality in all aspects of society, including health care.

“One of our questions was centered around trust,” she said; “One of the more recurring themes was patients did not trust the local medical system. They would say, ‘I don’t trust that hospital. If I go in and I don’t have this advance care plan, or I don’t have someone to speak for me, they’re just going to kill me.’ They didn’t trust the local medical system. We found that more in our Black population. Even our white population, who had Black family members or friends, commented about how they saw their loved ones of color treated in the medical system. That was a big recurring theme that I didn’t initially set out to discover, but it became very apparent.”

The findings were a clearly stated need for ethical and compassionate leadership in health care. It’s a role Sherman understands and takes seriously, and she embraces the opportunity to inspire her students and community members to become leaders in their own right.