Transgressing Venus Dalí Is Classical, Is Surrealist, Is Pop Art!

EXHIBITION

HOLOGRAM

Scientific / Contents Advice: Montse Aguer Teixidor Curatorship: Laura Bartolomé Roviras Documentation: Centre for Dalinian Studies Design: Pep Canaleta, 3carme33 Graphic: Bureau Alex Gifreu Preventive Conservation: Elisenda Aragonès Miquel, Irene Civil Plans, Laura Feliz Oliver, Josep Maria Guillamet Lloveras Registrar: Rosa Aguer Teixidor, Laura Feliz Oliver Assembly: Roger Ferrer Puig, Ferran Ortega López, Miquel Sánchez Duran Communication: Imma Parada Soler Web and Social Media: Cinzia Azzini, Pere Galán Vaca Rights Management: Mercedes Aznar Laín Marketing Direction: Leonora Aixas Otero

Photographs: The Art Institute of Chicago Production: tururut Art Infogràfic

A very sincere thank you to the Art Institute of Chicago and to all the people on its team who have accompanied us in the research of Salvador Dalí’s work. Caitlin Haskell, Gary C. and Frances Comer Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Suzanne R. Schnepp, former Head of Objects Conservation, Bonnie Rosenberg, Director of Imaging, and especially, Jennifer Cohen, Assistant Research Curator.

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 4

DIGITAL PUBLICATION

Edition: Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí

Authors: Montse Aguer Teixidor, Laura Bartolomé Roviras, Jennifer Cohen

Documentation: Centre for Dalinian Studies

Coordination: Laura Bartolomé Roviras

Coordination assistance: Maria Carreras Oliva

Photography: Gasull Fotografia SL, The Art Institute of Chicago

Translation of the texts: Marielle Lemarchand (French), Ricard Vela Pàmies (English reverse), Julie Wark (English)

Review of texts:

Bea Crespo Trancón, Rosa Maria Maurell Cons tans (Catalan Spanish)

Rights Management: Mercedes Aznar Laín

All the works and documents in this publication are from the collection of the Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, except where otherwise indicated.

COPYRIGHTS

From the works of Salvador Dalí: © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2022

From the texts by Salvador Dalí: © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2022

From the texts of this publication: Their authors

From the images of Salvador Dalí: Image rights of Salvador Dalí reserved. Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, 2022

From the reproductions of this publication: The Art Institute of Chicago, p. [32]. © 2022 The Art Institute of Chicago

Eric Schaal: p. 7, p. [22], p. 29 and p. 36 Eric Schaal © Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2022

Melitó Casals ‘Meli ’: p. 15. © Melitó Casals ‘Meli’/Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2022

Hansel Mieth: Hansel Mieth/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock: p. 47

The publisher wishes to state that every effort has been made to contact copyright owners of the images reproduced. In cases when that has not proved possible, we invite rights holders to contact the Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí

www.salvador dali.org

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 5

9

Transgressing Venus Dalí Is Classical, Is Surrealist, Is Pop Art! Montse Aguer Teixidor 17

Transgressing Venus Laura Bartolomé Roviras 31

‘New Flesh’: Dalí’s First Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936 Jennifer Cohen 41

Dalí’s Drawers

Laura Bartolomé Roviras 51 Catalogue Centre for Dalinian Studies

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 6

CONTENTS

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 7

Eric Schaal, Salvador Dalí painting one of the murals inside Dream of Venus, 1939

Transgressing Venus Dalí Is Classical, Is Surrealist, Is Pop Art!

Montse Aguer Teixidor Director of the Dalí Museums and the Centre for Dalinian Studies

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 9

‘Because the only difference between immortal Greece and the contemporary era is Sigmund Freud who discovered that the human body, which was purely neoplatonic in the time of the Greeks, is now full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis can reveal.’

Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí (1972)1

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 10

This temporary exhibition, like others before it, has entailed research, devotion, and also reflection. It has enabled us to make ‘visible’ Dalí’s main lines of thought about the Venus de Milo and the presence of this Hellenistic sculpture throughout his artistic creation. We have analysed the reinterpretation that Dalí himself made of the work in the 1960s, when he situated it as a forerunner of Pop Art, and have also described its subsequent installation as Venus de Milo with Drawers in the Dalí Theatre Museum in Figueres.

We can associate the Venus de Milo with Dalí’s similar obsession with Millet’s painting The Angelus. Both of them, iconic works belonging to the collective imaginary, attracted him from early childhood, especially because of the enigmatic, underlying power they transmit, which prompted him to reveal new meanings and produce new interpretations. In fact, both works enabled him to develop, in different creative periods, his paranoiac critical method of perceiving reality.

In Dalinian thought, interpreting Venus involves rethinking the classical ideals of beauty and civilisation within the framework of his surrealist creation, and in a twentieth century society avid for new perspectives. This reexamination is clearly visible in the Venus de Milo with Drawers which, for two reasons, has now become the centrepiece of this exhibition. First, is the hologram of the sculpture of Venus at the Art Institute of Chicago, which uses the innovative emerging T OLED technology. The video has been produced with 72 high resolution photographs in which the 360º animation is digitally introduced. And second, beside it, in another showcase, is the sculpture of Venus at the Dalí Theatre Museum: two Venuses for two historical times of the same century

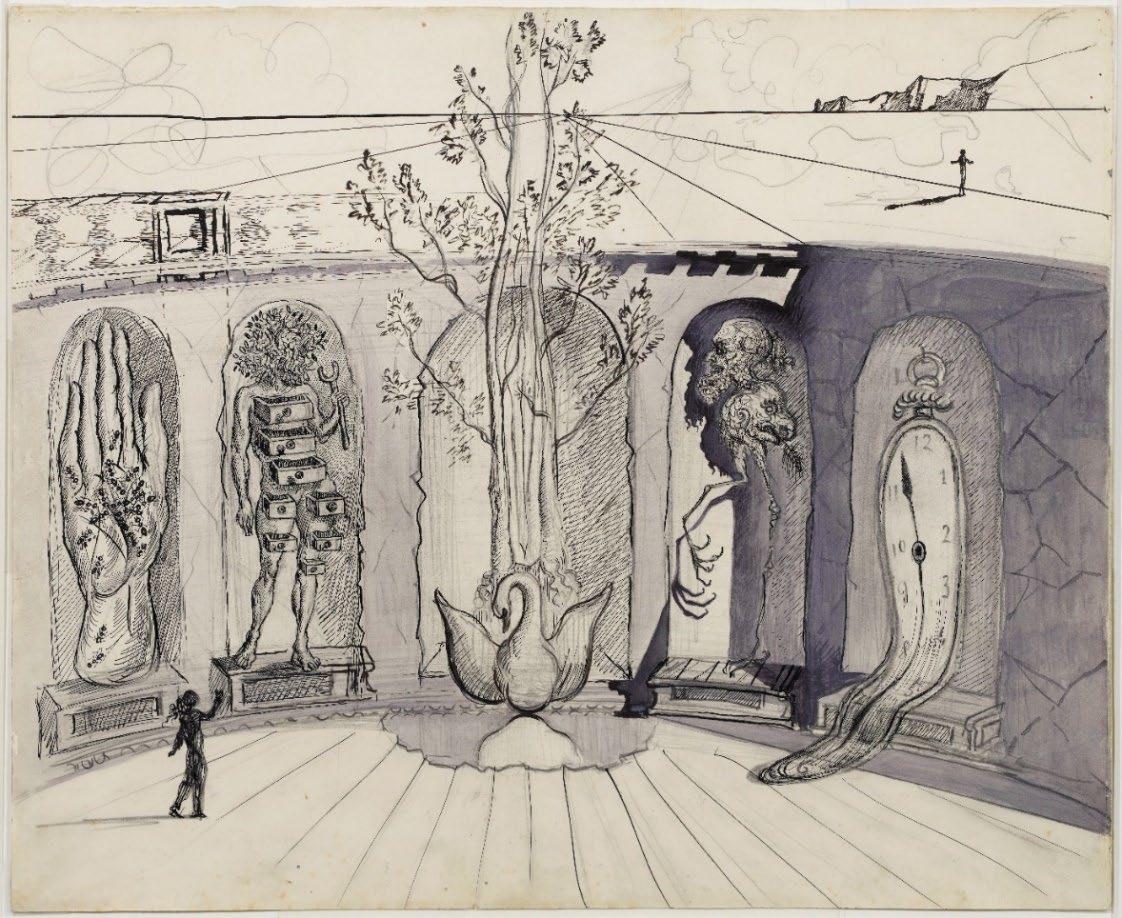

However, Venus is also reexamined in other works by Dalí dating from the 1930s, for example his Dream of Venus pavilion of the 1939 New York World’s Fair for which he planned a façade featuring a large Aphrodite with a fish head. After the Fair’s organising committee eventually refused to allow Dalí to use this image, it became one of the reasons that led him to publish his manifesto, Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness. Dalí’s Dream of Venus is considered to be one of his first pieces of architecture and, in some ways, it is a foreshadowing of the Dalí Theatre Museum. With the 1939 pavilion, Dalí was already pondering several important references, as well as certain overall principles, for his museum.

Dalí also reinterprets Venus from the standpoint of transgression. It should not be forgotten that one of the tools of surrealists, and of the avant garde movement in general, is perception of the fragmented, destructured, or eroticised human body as a form of expression that startles the viewer with new content going beyond the bounds of established norms. The surrealist drawers protruding from Venus perform this function and, from a Freudian standpoint, open doors to the subconscious. Dalí himself declares, ‘the human body, which was purely neoplatonic in the time of the Greeks, is now full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis can reveal.’2

In 1964, the Venus de Milo with Drawers appeared in a limited edition of bronzes, one of which Dalí later installed in his museum. In November the same year, Dalí appeared before television cameras in Barcelona to present the project of his future museum, declaring that he

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 11

would fill it with ‘the most shocking examples of what is now called Pop Art. For example, on one of the balconies there will be six sculptures of the Venus de Milo, all of them, of course, with their respective drawers more or less sunk into their visceral depths.’3 Although, in fact, this particular project never came to fruition, it is yet another example of the sculpture’s conversion into Pop and its overlapping with his museum, his last great work.

One curious point worth highlighting is that, as early as 1937, Dalí demystified the Venus de Milo, although indirectly, in his essay ‘Surrealism in Hollywood’, in which he refers to Harpo Marx, with whom he was very friendly, in the following terms: ‘He was caressing, like a new Leda, a dazzling white swan, and feeding it a statue of the Venus of Milo made of cheese, which he grated against the string of nearest harp’.4 This is, perhaps, a shared vision of the Venus de Milo as an edible or consumable object: ‘Beauty will be edible or it will no longer be’. Once again, Dalí foresaw artistic trends and situated himself in contemporaneity. In his Prologue to the book La Vision artistique et religieuse de Gaudí, which was published in 1969, he places his Venus de Milo with Drawers, of 1936, in the genealogy of Pop Art, in a lineage that also includes other prominent figures in the history of art, from Lysistratus to Gaudí, Boccioni, Duchamp, Richefeu and Segal.

Then again, shortly before Dalí replicated in bronze his Venus de Milo with Drawers, Andy Warhol had painted his famous ‘Coca Cola’, making the bottle one of the first Pop Art icons. However, Dalí had already incorporated this icon into his Poetry of America, a painting dated 1943 in which, once again, he anticipated the movement of the early 1960s. Like the Venus, he placed this work on the first floor of his museum in Figueres. The line of interaction between tradition, surrealism, and Pop Art is condensed in the space of his museum and, in particular, through the sculpture we are exhibiting this year. As already noted, Dalí had envisaged the whole layout of his Theatre Museum, and had placed a bronze copy of his Venus de Milo with Drawers in a special niche on a first floor passageway leading to the space devoted to Moses and Monotheism, thus evoking, perhaps, the conceptual genesis of his sculpture.

Another of the aspects that appear in the Dalí Theatre Museum is the incorporation of technology, especially because of the new opportunities it offered, into Dalí’s artistic practice. As he himself said, ‘The doors have been opened for me into a new house of creation’5. This is particularly visible in works like the hologram Holos! Holos! Velázquez! Gabor!, which he created with the Nobel laureate for Physics, Dennis Gabor, in 1972. In another hologram, dated 1973, the American rock singer Alice Cooper is sitting on a revolving platform where he starts singing with a microphone statuette of the Venus de Milo in his hand, as his brain is coming out of his head. For all these reasons, we believe it is appropriate to present, by means of current holographic techniques, the 1936 Venus de Milo with Drawers, which is presently in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. We have therefore organised a digital loan, a form of mobility for a three dimensional work of art which guarantees its conservation when it is fragile because of its material, in this case, plaster. It also allows us to reintroduce, conceptually, a resource that Dalí had already embraced in his lifetime.

Dalí has created an icon with his interpretation of the Venus de Milo as the Venus de Milo with Drawers.This exhibition can help viewers to reflect on whether he achieved this through

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 12

sacralisation or demystification, or by means of a difficult combination of both. Yes, he has done so, once again, from a stance of provocation and enigma, which are also found in the essence of his Dalí Theatre Museum, forming part of his most genuine surrealist convictions, which call for ‘freedom of the imagination, destruction of the reality principle, (or) a new awareness of the dazzling images of our truest and deepest desires’.

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 13

Footnotes

Illustrations

1 Jean Christophe Averty (dir.), Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, RM Productions, Télévision Française, Henry R. Coty, 22/12/1972, min. 36:05 36:38. Author’s transcription and translation into Catalan.

2 Ibid.

3 According to the press of the day: ‘Conferencia de prensa de Dalí ante las cámaras de televisión’, La Vanguardia española, 10/11/1964, Barcelona, p. 7. Author’s translation into Catalan.

4 Salvador Dalí, ‘Surrealism in Hollywood by Salvador Dalí’, Harper's Bazaar, 30/06/1937, New York, p. 68.

5 Salvador Dalí, The 3rd Dimension: The 1st World Exposition of Holograms Conceived by Dali, M. Knoedler & Co., Inc., New York, London, 1972, p. [1].

[1] Melitó Casals, Meli, Salvador Dalí in his studio in Portlligat, 1968.

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 14

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 15 [1]

Transgressing Venus

Laura Bartolomé Roviras Curator at the Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 17

‘My surrealist glory was worthless. I must incorporate surrealism in tradition. My imagination must become classic again.’

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942) 1

[1] [2]

‘I also made at this period a copy of the Venus of Milo in clay; I derived from this my first attempt at sculpture an unmistakable and delightful erotic pleasure.’2 The circumstantial references in Dalí’s account of this memory make it possible to locate this experience in the period when his family moved to live at number 10 carrer Monturiol (presently number 24), Figueres, in 1912.3 Hence, the reader can imagine the boy Dalí, barely eight years old, modelling a Venus de Milo in clay. He also recalls producing another Venus during a stay at a property known as, the Molí de la Torre (the Tower Mill) in the municipality of El Far d’Empordà: ‘I painted Helen of Troy or sketched Venus de Milo (…). By playing the embryo genius in that way, I gave birth to the genius; setting up the conditions for his birth, I created its cause.’4 It is evident that this icon of Greek art is part of the early experiences of the artist who was already dreaming of being a genius.

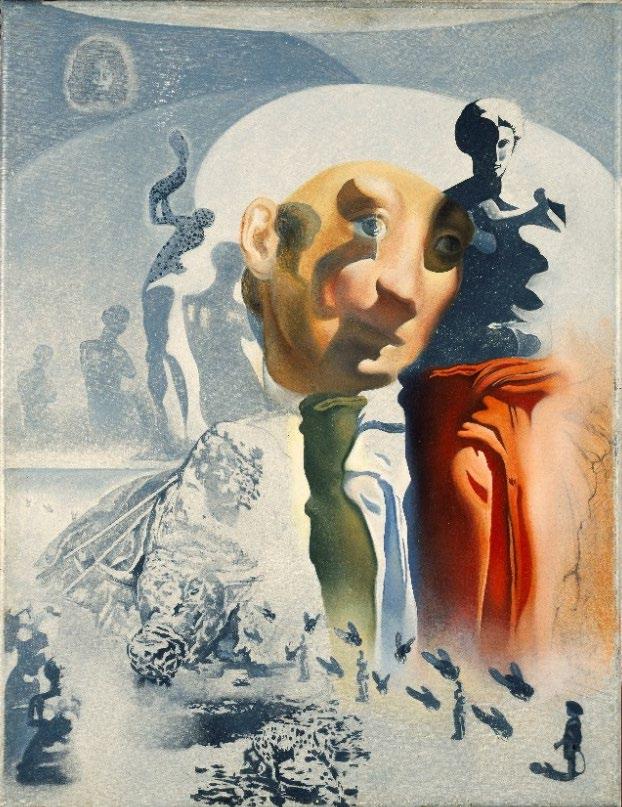

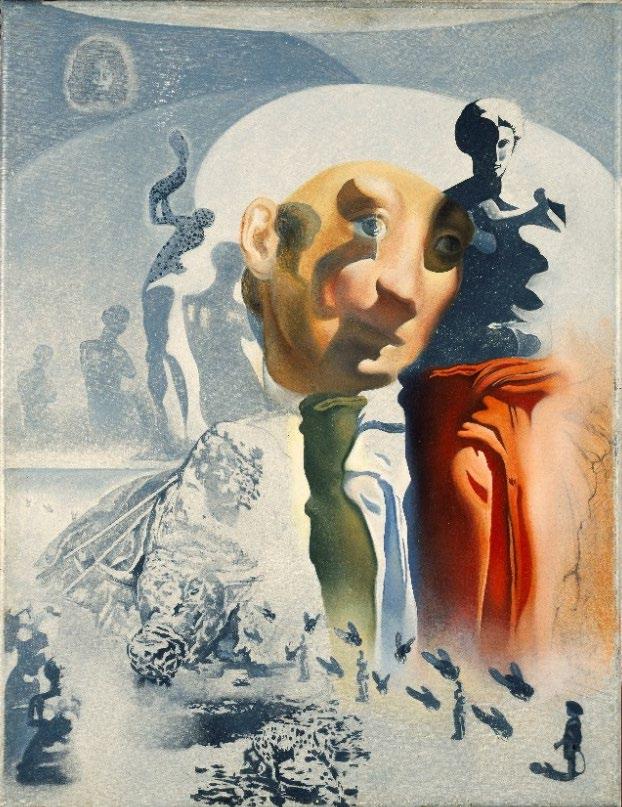

In some sense, the Venus de Milo formed a pendant to Millet’s The Angelus, a painting that Dalí also discovered when he was a schoolboy in Figueres.5 Images of these two works became his obsessive references as well as the leading lights of his paranoiac critical method. While The Angelus is the painting on which he based his method, the Venus de Milo is the centrepiece of one of his most famous double images, presented in the The Hallucinogenic Toreador of 1970. ‘I have used accumulations of a single obsessive image like the Venus de Milo to obtain a hallucinogenic structure that can evoke any kind of specific image in the viewer.’6 In the Study for The Hallucinogenic Toreador [1] one can clearly

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 19

see how Dalí uses repetition of the Venuses to both hide and reveal the face of the bullfighter Manuel Laureano Rodríguez Sánchez, otherwise and better known as Manolete. In 1968, the photographer Melitó Casals, Meli, immortalised Dalí working on this creation, surrounded by workshop material, and also a small replica sculpture of the Venus de Milo. 7

However, long before that, in 1936, at the height of his surrealism, Dalí embraced this Greek sculpture to create his Venus de Milo with Drawers [2]. Dalí himself identified the ‘invention’ of this work as the result of the perfect functioning of his paranoiac critical method at a particularly convulsive time: the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.8 This is a plaster statue that recalls, on a reduced scale, the original work, which has been displayed in the Louvre Museum of Paris since 1821. Dalí transgressed the classical reference by perforating the body of Venus with six drawers that can be opened and closed. These are elements which, as he himself declares, can only be understood through psychoanalysis: ‘Because the only differen ce between immortal Greece and the contemporary era is Sigmund Freud who discovered that the human body, which was purely neoplatonic in the time of the Greeks, is now full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis can reveal.’9 Is it possible that his desire to transgress was a response to an intention to accommodate the ideal of the classical world to the reality of his present, which is to say, that of the 1930s?

Dalí, however, is not the only one who created a ‘shocking visual parable’ of the Venus de Milo.10 In the early 1920s, the Dadaists Johannes Theodor Baargeld and Erwin Blumenfeld used the image in their photographic collages.11 Some surrealists were also fascinated by the icon and, like Dalí, transferred it to their sculptural work. Les menottes de cuivre (The Copper Handcuffs), 1931, is a sculpture by René Magritte in which the goddess is subjected to an evident chromatic transformation.12 Later, other artists including the American Jim Dine and the French Arman, to cite just two of them also played their part in this contemporary afterlife of the Venus de Milo. Moreover, the Restored Venus by Man Ray, the Blue Venus by Yves Klein, and the Metallic Venus by Jeff Koons testify to no less special tributes to the Greco Roman goddess using other models or references. In 1973, the Ready Museum in Brussels and the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris held the exhibition La Vénus de Milo ou les dangers de la célébrité, which clearly shows the prolonged fascination this ancient sculpture held for certain contemporary artists, among them Dalí.13

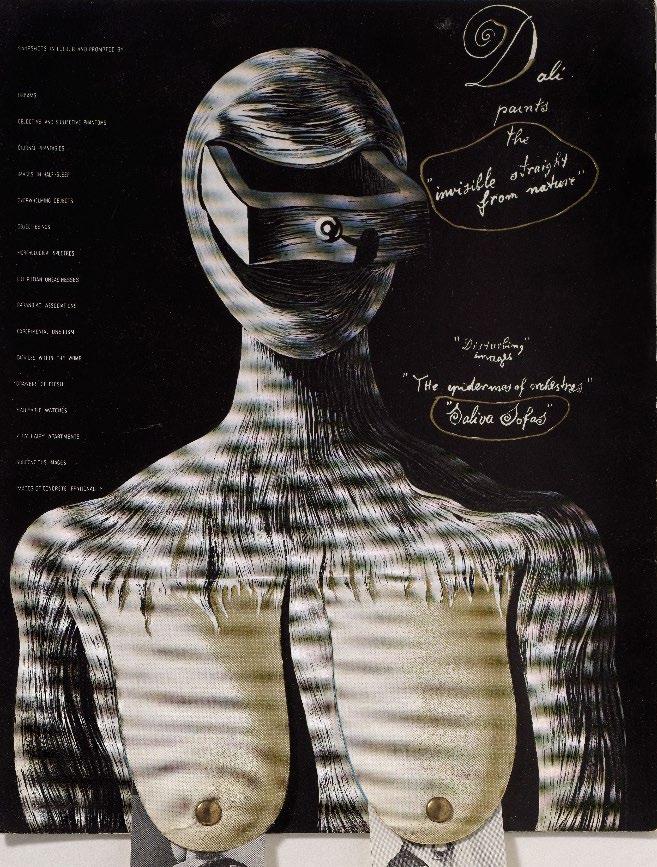

To return to the Venus de Milo with Drawers, it could be said that Dalí achieved his goal by enkindling his paranoiac critical method. In his own words, ‘My surrealist glory was worthless. I must incorporate surrealism in tradition. My imagination must become classic again’14 Without a doubt, his statements in The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí make it possible to grasp the point his career had reached and what his immediate intentions were: ‘Instead of stagnating in the anecdotic mirage of my success, I had now to begin to fight for a thing that was ”important”. This important thing was to render the experience of my life “classic” to endow it with a form, a cosmogony, a synthesis, an architecture of eternity’15. Dalí managed to incorporate surrealism into tradition, transgressing the genuine aura of the Venus de Milo with the addition of drawers. Moreover, this is not the only occasion when one can observe a similar practice. On the cover he designed for Minotaure Magazine, he transgresses the monster of the labyrinth with drawers, a lobster, and a key on the right leg, a key that recalls

the two that were hanging from the neck of Venus de Milo with Drawers in 1939 when the work was shown in the exhibition held by the Julien Levy Gallery in New York

Before continuing this inquiry into Dalí’s purpose, it is interesting to focus on his creative process. The presence of the two keys with the Venus de Milo with Drawers in 1939 is probably ephemeral. In fact, there is no sign that they were part of the work of 1936, and neither are they found again later. Transitory addition to an already finished work is a practice that Dalí engaged in during the 1930s.16 The result of this is an ephemeral work that only exists for the duration of its public exhibition. For study purposes, this particular creation is identified as a version of, or variation on the original work, which is to say the Venus de Milo with Drawers of 1936.17

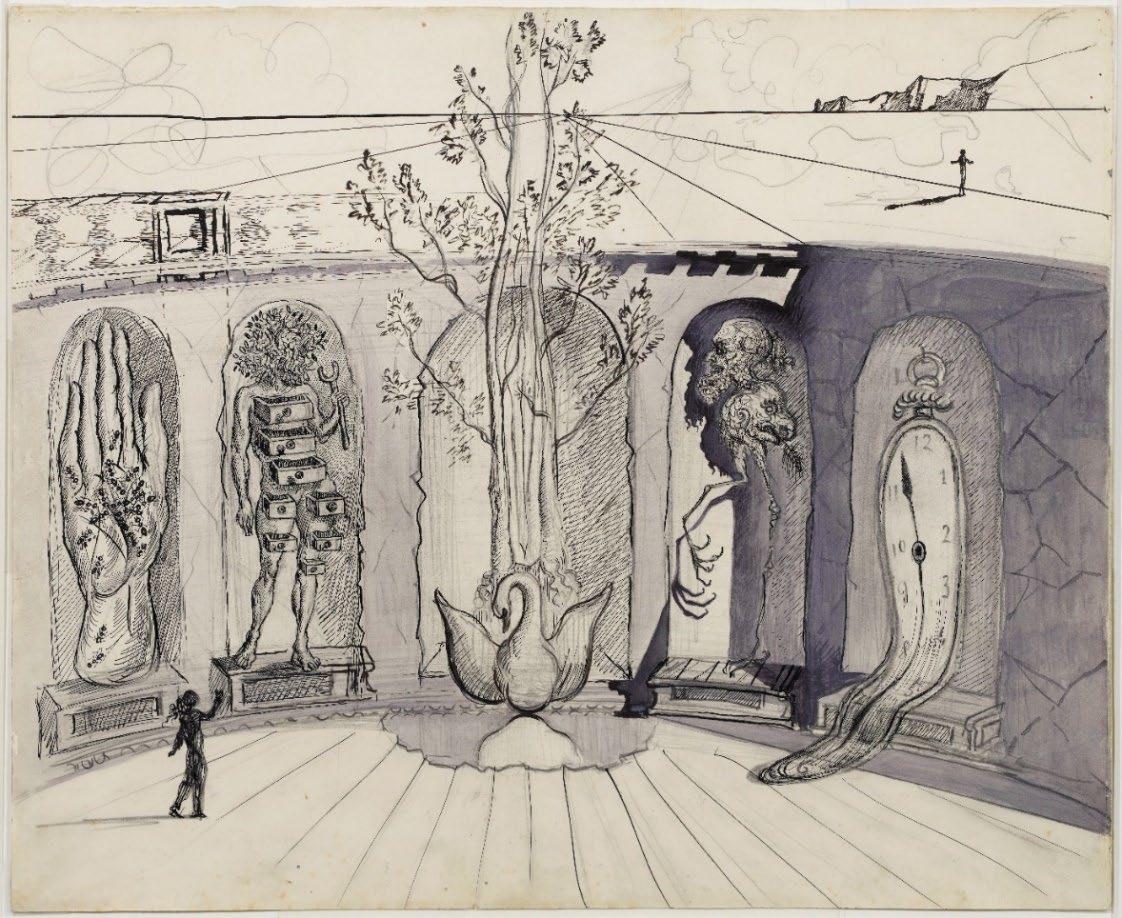

In the Julien Levy Gallery, Dalí combined this sculpture with an installation presided over by a recreation of the Trylon and the Perisphere the two monumental streamline form buildings of the New York World’s Fair [3].18 Dalí personalised it with his most genuine surrealist iconography: keys, ants, cracked walls, and Yin and Yang forms. The Trylon is also marked with a list of characters and artists. On one face are the names of Caligula, Paracelsus, and Dalí, amongst whom parallels are not easy to find, although it is true that all three, in their different periods, shared a special interest in alchemy. Another face is labelled with the names Messonier, Böcklin, Dalí again, Leonardo, and Vermeer. In some way, this recalls Dalí’s ‘ranking’ where he rates the figures of the history of art he most admires in 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship 19 And Vermeer is placed at the top both times. It seems that this elongated pyramid also showed Freud’s name, according to the press of the day.20 This evocation of the father of psychoanalysis, whom Dalí had met in person the previous year,21 would lead us to speak of the connection that has been established between his inquiry into the subconscious and the Venus de Milo with Drawers. The keys, perhaps, could be a visual metaphor for psychoanalysis, the means that Dalí himself validates for tapping into these ‘secret drawers’.

After this exhibition in the United States, it is true that Dalí exhibited and spoke of the work again on only a few occasions. Yet he did do so in the 1960s, coinciding with the bronze edition of 1964. It is probable that he agreed to replicate the sculpture in response to a growing demand for the work to be shown in international exhibitions. In fact, the Venus de Milo with Drawers has been part of almost all the Dalí retrospectives: in Japan the same year (1964), then in New York (1965), Amsterdam (1970), and also the Centre Pompidou in Paris (1979). However, the ‘multiplication’ of the original work of art can be related with a concept shared by other artists like Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray who, in the same period, also began to edit some of their own works.22 According to the available information, the limited edition of bronzes was done by the French painter and poet Max Clarac Sérou who, at the time was director of the Galerie du Dragon in Paris. All the bronzes have a white patina, probably to conserve the memory of the original work. As a new touch, Dalí added a fur pompom to each of the six drawers. The precise intention that led him to introduce these elements which, however, represent a new transgression is unknown. They are sometimes related with the work of Leopold von Sacher Masoch, the Austrian writer who addresses masochism with his Venus in Furs , which was published in 1870. 23 In 1967, the press also

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 21

[3]

[4]

repeated a significant statement by Dalí: ‘We live in the century dominated by masochism […] in which Venus is wrapped in furs.’24

Whatever the case, Dalí added the pompoms to all the casts except one, namely that reserved for the Dalí Theatre Museum, which is identified with the inscription ‘Exemplaire Gala Dali’ [4]. It is highly likely that, with this gesture, he wanted to distinguish this cast from the other bronzes, thus turning it into a certain kind of unique work. This was the impression of his close friend Antoni Pitxot, director of the Dalí Theatre Museum until 2016, who also took part in the creation of the Museum. Such distinctiveness, conceived and desired by Dalí, means that the sculpture is identified as a unique cast.25 This decision could also open the way to interpreting another nuance. In fact, the Venus de Milo with Drawers of 1936, which is now in the Art Institute de Chicago, still has fur pompoms, which in some sense follow the same precept that was assigned to the bronzes of 1964. But when were these elements added to the original work in plaster? Images by the photographers Eric Schaal and Hansel Mieth, who immortalised the work in 1939 do not show the presence of pompoms.26 This makes it necessary to think of a later addition, but during Dalí’s lifetime. The book Dalí de Gala, published by Robert Descharnes in 1962 includes a photograph of the sculpture with pompoms, but not the present ones.27 Yet in an article published in the press the same year, this sculpture in fact the only one that existed at the time appears without pompoms.28 Is it possible, then, that the pompoms were added in around 1962? And that the bronze casts of 1964, except for that of the Dalí Theatre Museum, present the same detail as a result? What Dalí ended up achieving with this was to preserve in this cast the physiognomy that is closest to the original work of 1936.

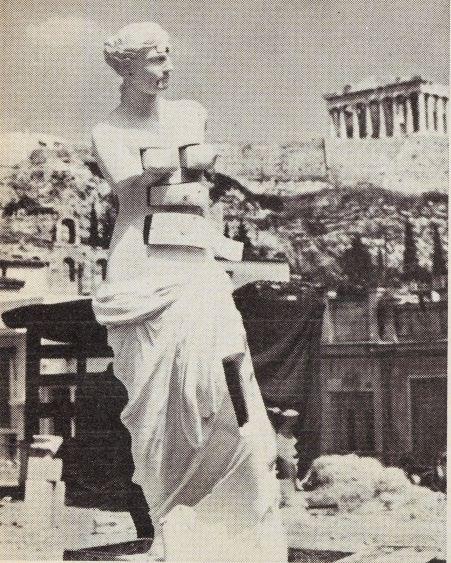

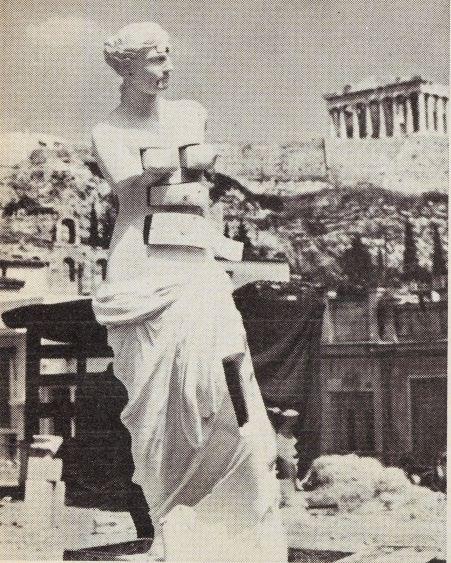

A Venus de Milo with Drawers, probably a bronze without pompoms, travelled to Athens in 1965 to be shown in the Panathenaia of Sculpture, which was curated by Tonis Spiteris.29 The site chosen for it, with the Parthenon in the background, aimed to highlight the connection between classical Greece and contemporary creation. Dalí’s sculpture would seldom find a better setting in which to reverberate everything that had led to its creation in 1936. The photographs published in the press at the time evoke the link between surrealism, the Venus de Milo with Drawers, and the Parthenon [5] 30 Nevertheless, this happened at a time when Dalí had already declared that his sculpture had embarked on its new journey.

In November 1964, Dalí announced before the cameras of Spanish television an installation of six copies of his Venus de Milo with their respective drawers on a balcony of his future museum. He imagined this project as ‘the most shocking of what is now called Pop Art’.31 Although the idea did not come to fruition, his announcement was a clear statement of intention. Moreover, in Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, a film shot by Jean Christophe Averty in 1966, Dalí declared before the camera that his Venus de Milo with Drawers is ‘a lesson for Pop artists’. In his Prologue to Gaudí, the Visionary, which was originally published in French in 1969, he also even identifies his Venus as a forerunner of Pop Art,

‘Whether or not it uses casts, there is a whole body of art called “pop” in modern terminology, the genealogy of which is completely legitimate:

Lysistratus, inventor of casting from nature, fourth century B.C.

The sculpted carriages in Italian cemeteries at Palermo and Genoa, nineteenth century.

[5] [6]

Gaudí, and the realistic sculptures of the SAGRADA FAMILIA. Boccioni and his “DEVELOPMENT OF A BOTTLE IN SPACE,” 1912. Marcel Duchamp, with his “BOTTLE RACK,” the first ready made, 1914. Richefeu, “LONG LIVE THE EMPEROR,” 1917. Dali, “VENUS DE MILO WITH DRAWERS,” 1936. Segal and pop art, today.’32

The transformation of this sculpture into a forerunner of Pop Art at the end of the sixties is certainly both surprising and revealing. The Venus de Milo with Drawers is classical, is surrealist, and is Pop Art! Dalí is classical, is surrealist, and is Pop Art!

It is therefore not at all surprising that Dalí’s icon should find its definitive home in the Dalí Theatre Museum. In 1970, in a report published in a La Actualidad española, Dalí stated, ‘The museum will be full of niches in which the whole history of Greek and neo Greek sculpture, from the Venus de Milo onwards, will be displayed.’33 And indeed, in the vestibule of the Museum, two niches with semicircular arches contain two reproductions of José Álvarez Cubero’s statue of Ganymede in versions by Dalí. In the inventory of casts at the Real Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid there is one of this neoclassical sculpture, so it could evoke the plaster models that were part of Dalí’s artistic education.34 Furthermore, in the ground floor passageway there is a display case which, showing the

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 25

reproduction of the Venus de Milo, is placed next to another Venus that recalls a Roman sculpture from the first and second centuries CE. This latter work is conserved, restored and with arms, in the British Museum.35 In a niche on the first floor passageway, there is a cast of the Venus de Milo with Drawers and, in the Centre for Dalinian Studies, there are several photographs showing that it had already been placed here in August 1973, in a museum that was still being constructed.

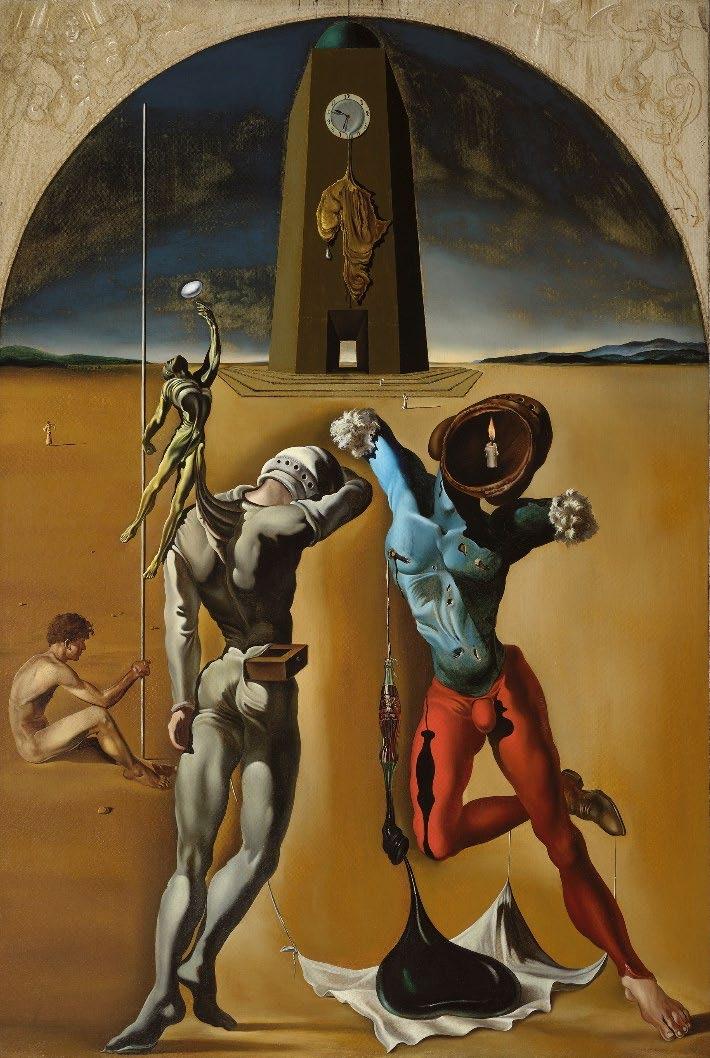

Perhaps there are messages yet to be discovered in the conception and creation of this passageway in the Dalí Theatre Museum. It is true that visitors starting to walk through this space after leaving the Mae West room find a particular series of works. These include the Retrospective Bust of a Woman 1933/1976 1977, one of Dalí’s main surrealist objects; the niche with the Venus de Milo with Drawers 1936/1964; an installation devoted to Millet’s The Angelus and, accordingly, to Dalí’s paranoiac critical method; the reconditory reserved for Poetry of America [6] a painting from 1943 in which surrealism is still pointedly present. Yet, without a doubt, the most surprising thing is his anticipation of Pop Art, approached with his representation of a Coca Cola bottle; and, right at the end of the route, on the other side of the semicircle, visitors cross a space devoted to Moses and Monotheism, a clear tribute to the work by Freud. The blending of classicism, surrealism, psychoanalysis, and Pop Art that Dalí might have organised in this space is the same as that which he condenses in his Venus de Milo with Drawers. And all of this endures in his particular Olympus, his Dalí Theatre Museum, his last great work of art which is also the repository of his immortality.

5

3

Footnotes

1 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, Dial Press, New York, 1942, p. 350

2 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life..., Op. cit., p. 71

Cf. Mariona Seguranyes Bolaños, Els Dalí de Figueres. La família, l’Empordà i l’art, Figueres, Barcelona, Ajuntament de Figueres, Viena Edicions, 2018, p. 53. Salvador Dalí, Obra completa, vol. VII, Àlbum Dalí, Destino, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Barcelona, Figueres, Madrid, 2004, p. 10

4 Salvador Dalí, Comment on devient Dali (1973). Salvador Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali, William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1976, p. 63

Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life..., Op. cit., p. 64

6 Salvador Dalí, ‘I have used…’, Art Now, 2, no. 5, University Galleries, New York. Translated from: Obra completa, vol. IV, Assaigs 1, Destino, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Barcelona, Figueres, 2005, p. 815

7 Photograph by Melitó Casals dated 1968 conserved in the archive of the Centre for Dalinian Studies. See p. 15

8

Salvador Dalí, Comment on devient..., Op. cit., p. 181

9 Jean Christophe Averty (dir.), Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, RM Productions, Télévision Française, Henry R. Coty, 22/12/1972, min. 36:05 36:38. Author’s transcription and translation into Catalan.

10 Dimitri Salmon, ‘De l’Aphrodite de Mélos à la Vénus de Milo’. In D’après l’Antique, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000, p. 434

11 Dominique de Font Réaulx, ‘Disposition verticale comme portrait du Dada Baargeld’ and ‘Manina ou l’âme du torse’. In D’après l’Antique, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000, p. 457 458, 459

12 Michel Draguet, ‘Magritte and Dalí: Hermetic Mimesis’. In Dalí and Magritte, The Dali Museum, Ludion Publishers, St. Petersburg, FL., Brussels, 2018, p. 54, 94 95.

13 La Vénus de Milo ou les dangers de la célébrité, Louis Musin Éditeur, Brussels,1973. Appearing in this exhibition are the Venus de Milo with Drawers and the Otorhinological Venus by Dalí, with catalogue number 8.

14 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life..., Op. cit., p. 350.

15 Ibid.

16 See: Laura Bartolomé Roviras, ‘Understanding the original sculpture of Salvador Dalí by way of Retrospective Bust of a Woman’. In Salvador Dalí, Retrospective Bust of a Woman, 1933/1976 1977, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2015, p. 22 61

17 See: Artistic criteria of the Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí in relation to sculpture and three dimensional work. https://www.salvador dali.org/en/artwork/obra escultorica/criteris artistics de la fundacio gala salvador/ [Last accessed: 08/08/2022].

18 This installation is known today thanks to a series of photographs by Eric Schaal, now conserved in the archive of the Centre for Dalí Studies.

19 Salvador Dalí, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, Dial Press, New York,1948, p. 28.

20 Robert M. Coates, ‘The Art Galleries’, The New Yorker, 01/04/1939, New York, p. 56

21 Salvador Dalí, Obra completa, vol. VII , Op. cit., p. 124 125.

22 Adina Kamien Kazhdan, ‘Duchamp, Man Ray, and Replication’ In The Small Utopia Ars Multiplicata, Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2012, p. 97 113

23 William Jeffett, ‘Venus de Milo with Drawers’. In Dalí, Bompiani, [Milan], p. 258.

24 ‘Salvador Dalí, doctor honoris causa’, Presència, 09/12/1967, Girona, p. 15.

25 See: Artistic criteria of…, Op. cit.

26

To the present day, it has not been possible to identify any image or description of the work prior to 1939. In fact, it seems that it was not presented to the public before this date. Although Robert Descharnes stated that Dalí showed the sculpture in a private session on 19 June 1936 in his apartment at 101 bis rue de la Tombe Issoire in Paris, it has not been possible to confirm this information. See: Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus de Milo et la persistance de la mémoire antique’. In D’après l’Antique, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000, p. 463

27 Robert Descharnes, Dali de Gala, Edita, Lausanne, 1962, p. 165, 223. This work is identified as a plaster

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 27

Illustrations

sculpture dated 1936. It was then conserved in a private collection in Paris

28 Leslie Lieber, ‘The Mystery of Venus's Arms’, This Week Magazine, 04/03/1962, p. 11 and ff.

29 Eva Fotiadi, ‘What could art history contribute to modern Greek studies in the 21st century: A discussion with Areti Adamopoulou’, 29/01/2021. Publ.: https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/what could art history contribute to modern greek studies in the 21st century. part i. a dis [Last accessed: 28/07/2022].

30

‘Art Sculpture’, Time Art, 08/10/1965, New York, p. 48

31 ‘Conferencia de prensa de Dalí ante las cámaras de televisión’, La Vanguardia española, 10/11/1964, Barcelona, p. 7. Author’s translation into Catalan.

32 Robert Descharnes, Clovis Prévost, Gaudí, the Visionary, Viking Press, New York, 1982, p. 12.

33 José Antonio Vidal Quadras, ‘El Museo Dalí visto por Dalí’, La Actualidad española, 06/08/1970, Barcelona, p. 54. Translated into Catalan by the author

34 See: https://www.academiacolecciones.com/esculturas/inventario.php?id=E 010 [Last accessed: 04/08/2022].

35 See: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/ G_1805 0703 16 [Last accessed: 23/08/2022].

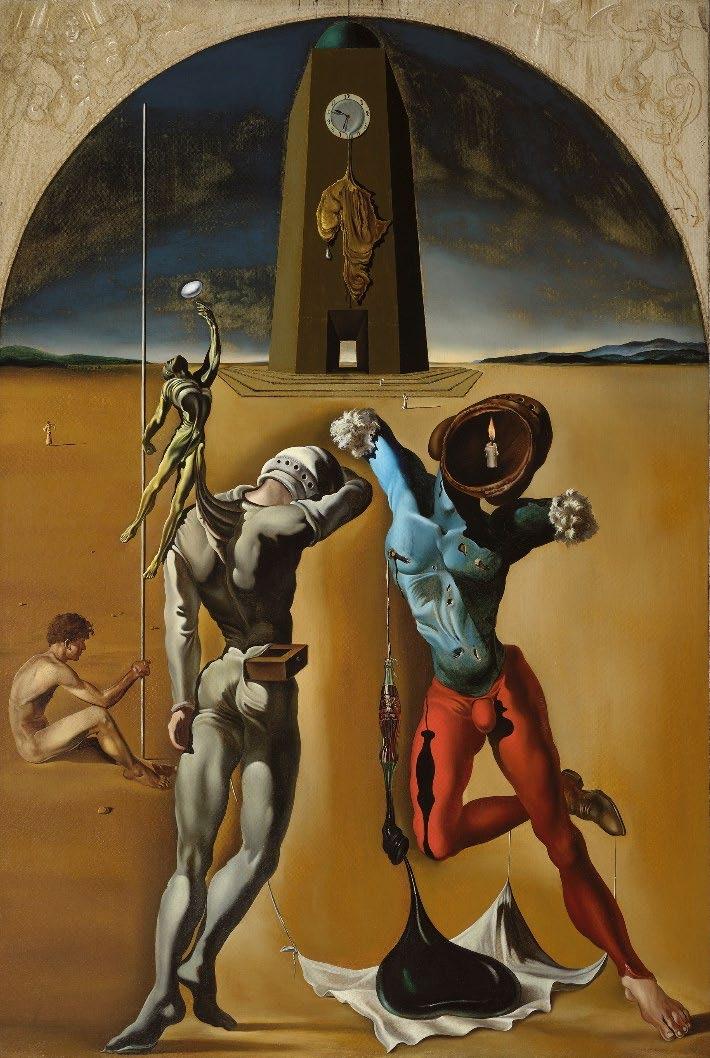

[1] Salvador Dalí, Study for The Hallucinogenic Toreador, c. 1969, oil on canvas.

[2] Salvador Dalí, Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936, painted plaster with metal pulls and mink pompons, 98 x 32.5 x 34 cm (38 ⅝ x 12 ¾ x 13 ⅜ in.), Through prior gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman, Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.424.

[3] Eric Schaal, Installation with Venus de Milo with Drawers in the exhibition Salvador Dalí 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, 1939, corrent copy.

[4] Salvador Dalí, Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936/1964, painted bronze.

[5] Photograph of Dalí’s Venus de Milo with Drawers at the exhibition Panathenaia of Sculpture in Athens.

[6] Salvador Dalí, Poetry of America, 1943, oil on canvas.

[7] Eric Schaal, Salvador Dalí at the façade of Dream of Venus during its construction, 1939, period copy.

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 29 [7]

‘New Flesh’: Dalí’s First Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936

Jennifer Cohen Assistant Research Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago

31

[1]

Among the earliest and most articulate theorists of a new category of art making known as the surrealist object that gained traction in the early 1930s, Salvador Dalí described an ephemeral found object assemblage incorporating such psychologically resonant items as glass of milk and his adored wife Gala’s shoe as ‘functioning symbolically,’ producing meaning in the process of its handling, and even potential consumption.1 Creations like this made Dalí one of the most venturesome practitioners in this medium, profoundly challenging not only sculptural conventions but also the boundaries of art and life. Frequently ephemeral, we know of them and their changing states largely by means of photography. For example, Retrospective Bust of a Woman was captured in multiple subsequent versions after its first presentation in 1933, as the artist continuously altered it for display over the course of the next five years, both at home and in public exhibitions.2 The contribution of this theory and practice went beyond avant garde materials and procedures, implicating the body in new ways. Dalí famously advanced a theory of the aesthetics of edibility and the related notion of the ‘being object,’ which he illustrated with photographs of a masked figure, likely the artist himself, performatively striking a series of sculptural poses.3

One of the most memorable images of Dalí’s extensive iconography of the 1930s, Venus de Milo with Drawers [1] embodied these ideas with singular elegance and wit. A plaster cast just under half the size of the original Greek figural sculpture known as the Venus de Milo on display at the Louvre, it incorporates six custom fit sculpted, functional drawers. Presenting the artist’s idiosyncratic vision of beauty as something which could stand the test of time, it also ambiguously characterized the practice of psychoanalysis as both timeless and potentially vapid, the revelation of narcissistic voids which may or may not hold anything inside them. The earliest related commentary by Dalí is an apocryphal account of his first meeting with Harpo Marx, in which the artist finds the actor feeding ‘a statue of the Venus de Milo made of cheese’ to a swan.4 With its own capacity for physical ingestion, Venus de Milo with Drawers seemed to invert the artist’s evocative injunction, ‘beauty will be edible or will not be,’ with a cannibalistic flair in line with notable paintings of the same period, such as Autumnal Cannibalism and Soft Construction with Boiled Beans.5

Despite these enduring qualities and the artist’s growing celebrity during the mid 1930s, our knowledge of the early history of Venus de Milo with Drawers is surprisingly scant.6 One of only a handful of extant original three dimensional surrealist works by Dalí, the object left little trace in exhibition histories and publications until much later, when the artist authorized the gallerist Max Clarac Sérou to fabricate a limited edition in bronze. It was during this later period that Dalí related additional remembrances to his close confidante Robert Descharnes, a photographer with singular access to the artist who briefly held the work before Clarac Sérou.7 To say that it has been difficult to separate history from mythology when it comes to understanding the life and art of Dalí would be a vast understatement; his autobiographical narrative must always be regarded as motivated humorous, ironic, or at least slightly exaggerated part of the same finely woven iconographic network evident throughout his art. That our knowledge of the origin of Venus de Milo with Drawers is nearly completely founded in this narration, makes it more interesting to ask why the artist chose to relate certain details about his work than to interrogate their historical veracity.

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 33

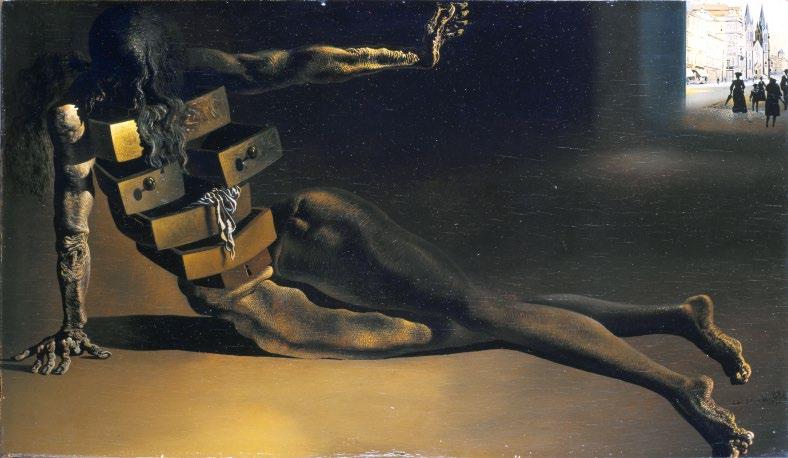

First, since the title is descriptive, what can we learn about the artist’s motivations by the dating of the work? Venus de Milo with Drawers has been dated to 1936 alongside a range of comparable two dimensional works representing human figures with drawe rs, including the painting City of Drawers and its preliminary sketches [2] 8 Indeed, similar illustrations published by the artist during this year exhibition catalogs and a cover of Minotaur [3] show that he was then in the process of developing this motif. Lo oking back some forty years later, Dalí described the origination of Venus de Milo with Drawers as part of the same context, naming his approaching speaking engagement in London in June of 1936, which immediately followed the important Exposition Surréaliste d’Objets at Galerie Charles Ratton. 9 This exhibition saw surrealist objects installed alongside a nearly encyclopedic range of object types, in a gallery space typically dedicated to so called ‘ primitive ’ art. Dalí presented three surrealist objects in this exhibition, indeed every other three dimensional work attributed to 1936 in the catalogue raisonné of sculpture Cat. no. OE 25, Cat. no. OE 26, Cat. no. OE 27. Significantly different in composition, material, and technique from Venus de Milo with Drawers , they were composed of disparate found objects assembled in an additive manner, while the Venus was more monolithic, and indeed actively subtractive in its technical construction, re introducing carving techniques to the cast by cutting into it. It is certainly the most sculptural intervention within Dalí’s three dimensional works of this period, kn owingly invoking the history of sculpture and its interplay of form and void.

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 34

[2]

[2]

Suddenly, in March 1939, the work appeared in public, in a complex installation heavily curated by the artist. Rare photographs of the interior of the Julien Levy Gallery taken on the occasion of the exhibition opening reveal the object installed precariously on a three dimensional model of the New York World’s Fair’s iconic Perisphere, with painted cracks and fissures [4].10 As one reviewer memorably described,

‘I imagine that many visitors to the gallery will be mildly startled to find a large plaster simulacrum of the Trylon and Perisphere in the place of honor in the centre of the exhibition especially since this Perisphere is cracked in spots like an egg about to hatch and is surmounted by Beauty in the form of a cast of the Venus de Milo...’.11

Not listed in the catalog, the object temporarily retreated back into obscurity, overshadowed by the related, yet more sensational, Dream of Venus pavilion that opened at the fair the following June. But by envisioning a symbol of the fair’s unifying theme ‘World of Tomorrow’ as distressed and in ruins, Dalí had indelibly presented the Venus de Milo with Drawers rising out of the rubble of the future. Casting his art as anticipatory of major world events, especially the Spanish Civil War and World War II, Dalí invested himself with the responsibility of spearheading a second renaissance, which would call upon the enduring qualities

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 35

[4]

of classical art, while embracing the inventions of psychoanalysis. In his autobiography, a related illustration titled ‘New Flesh’ punctuates a section describing his turn to classicism, where he writes, ‘I had now to begin to fight for a thing that was “important.” This important thing was to render the experience of my life “classic,” to endow it with a form, a cosmogony, a synthesis, an architecture of eternity.’12 If Venus de Milo with Drawers dated to 1936 to his suite of images of figures incorporating drawers, to the major exploration of the surrealist object at the Galerie Charles Ratton then Dalí’s interest in classicism narrowly predated these world events.13 At the same time, a 1936 creation date shows that the artist was already differentiating his three dimensional work from the surrealist object, even while continuing to make new and significant achievements in this medium. In addition to these psychologically resonant assemblage based objects, he was crafting ‘new flesh,’ an ambition with range far beyond Surrealism.

When Dalí left hurriedly for France, we can only speculate that the Venus de Milo with Drawers must have returned with him, and it remained in the artist’s collection for over a quarter century.14 Uniquely characterizing Dalí’s changing three dimensional practice, Venus de Milo with Drawers exemplifies the way in which his works tended to collapse temporalities through reiteration, rediscription, and reinvention, continuously creating a mythology that has endured well beyond his lifetime. While there is still much to be explored, especially with regard to the materiality of Venus de Milo with Drawers, the fur pompons in particular show the unique ability of Dalí’s work to signify multiple points in time simultaneously. As can be seen in the image of the object on display in 1939, they were incorporated at a later moment, a product of the artist’s reconsideration of the work during the early 1960s, as he began to imagine its subsequent lives in other collections, bronze editions, and much more. Two photographs taken in 1962, apparently in quick succession (without the forehead drawer in place) show the work before and after the pompons were added to the drawer pulls, initially positioned behind them and later reconfigured as a covering.15

This addition brought a range of historical and contemporary references to the object’s classical subject, not only recalling Meret Oppenheim’s Object (called Lunch in Fur by André Breton) and the ermine fingernails of Dalí’s Bonwit Teller mannequin with a head of roses Cat. no. OE 29, but also anticipating the artist’s later illustrations for Leopold Sacher Masoch’s Venus in Furs in 1970. 16 Fittingly, this historical leap was made through an intervention that might be described as a fashionable adornment, suddenly making Dalí’s 1936 from the additive procedures of the surrealist object to its interpretation in shop windows relevant once again, and transforming the fragile and aging work to meet its moment in the visual culture of the early 1960s.

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 37

Footnotes

1 My sincere thanks to the organizers of this exhibition, especially to Montse Aguer Teixidor, Director of the Dalí Museums, and Laura Bartolomé Roviras, curator at the Gala Salvador Dalí Foundation, where Bea Crespo kindly facilitated my research, and to my colleagues at the Art Institute of Chicago, especially Caitlin Haskell, Gary C. and Frances Comer Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Jay Dandy, Collection Manager, Modern and Contemporary Art, and Suzanne R. Schnepp, former Head of Objects Conservation

Salvador Dalí, ‘Objets surréalistes,’ Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, no. 3 (December 1931), p. 16 17. See: Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture and Three dimensional Work by Salvador Dalí, Cat. no. OE 1. All linked catalog numbers in this essay refer to this publication or its companion volume of pain tings, and they were accessed on May 10, 2022.

2 Laura Bartolomé Roviras, ‘Understanding the Original Sculpture of Salvador Dalí by way of Retrospective Bust of a Woman’. In Salvador Dalí, Retrospective Bust of a Woman 1933/1976 1977, Fundació Gala Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2015, p. 22 58.

3 Salvador Dalí, ‘De la Beauté terrifiante et comestible de l’architecture ‘modern’ style’, Minotaure 3 4 (December 1933), p. 69 76; Salvador Dalí, ‘Apparitions aérodynamiques des “Êtres Objets”’, Minotaure 6 (Winter 1935), p. 33 34. For an extended discussion of Dalí’s notion of the surrealist object in relation to his texts on the subject through 1936, see Haim Finkelstein, ‘The Incarnation of Desire: Dalí and the Surrealist Object’, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 23 (Spring 1993), p. 114 137

4 Salvador Dalí, ‘Surrealism in Hollywood’, Harper’s Bazaar (30/06/1937), p. 68. Thank you to Montse Aguer, Director, Dalí Museums, for bringing this article to my attention.

5 Salvador Dalí, ‘De la Beauté…’, Op. cit., p. 76.

6 1936 was perhaps the most eventful year for his development into a celebrity of international renown, despite the onset of the civil war in Spain and his famously theatrical ‘expulsion’ from the surrealist movement two years earlier. Even as he continued to participate as a leading surrealist artist in Paris, he was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in the United States, exhibiting at the Museum of Modern Art and in solo exhibitions in New York and London.

7 Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus de Milo et la persistance de la mémoire antique’. In D’après

l’Antique, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000, p. 462 463.

8 Robert Descharnes, Salvador Dalí: The Work, The Man, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1976, p. 199. A single day in home display of the work has been identified just a few weeks after the closing of the exhibition at Galerie Charles Ratton, an occasion that seems to have gone without comment in the press and within surrealist lore, even the artist’s own copious writings. Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus…’, Op. cit., p. 462 463.

At least two of these works are confirmed to have been first owned by Dalí’s London patron Edward James, who gave the artist a year long contract beginning the same summer and involved him in conceiving decor for his London townhouse. See Nicola Coleby (ed.), A Surreal Life: Edward James, 1907 1984, Royal Pavilion, Libraries & Museums, Philip Wilson, Brighton, London, 1998.

9 Salvador Dalí, as quoted in André Parinaud (ed.), Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí as told to André Parinaud, William Morrow and Company, New York, 1976, p. 181.

10 Thank you to Laura Bartolomé Roviras for disco vering these photographs and sharing them with the Art Institute of Chicago, and for her close attention to the changing states of the work over time.

Venus de Milo with Drawers seems to have gone without comment following the artist’s invitation to the press to view works planned for his exhibition at Julien Levy set to take place in just a few weeks in New York in his apartment at 99 rue de l’Université in Paris. It evidently travelled with the couple when they arrived from Le Havre at Ellis Island on the S.S. Ile de France on February 15th to be installed at the Julien Levy Gallery the following month.

11 Robert M. Coates, ‘The Art Galleries’, The New Yorker (01/04/1939), 56. Coincidentally, the Louvre replaced the original Venus de Milo with a plaster copy to protect it from the prospect of German invasion in 1939, which likely became common knowledge only later in this year.

See Agnès Poirier, ‘Saviour of France’s art: how the Mona Lisa was spirited away from the Nazis’, The Guardian (Nov. 22, 2014). See Agnès Poirier, ‘Saviour of France’s art: how the Mona Lisa was spirited away from the Nazis,’ The Guardian (22/11/2014), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/ 22/mona lisa spirited away from nazis jacques jaujard louvre [Last accessed 15/07/2022].

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 38

Illustrations

12 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, Dial Press, New York, 1942, p. 347.

13 Two comparable objects were included in the exhibition at Charles Ratton in 1936: another plaster cast of the Venus de Milo partially painted in naturalistic flesh tones by René Magritte and known as The Copper Handcuffs and Meret Oppenheim’s Object, which likewise activated found objects with fur. Magritte, like Dalí, was commissioned to create works for Edward James’s London home and was seeking a similar yearlong contract. As Danielle Johnson has argued about this moment of competition and shared patronage, ‘rivalry between the two artists peaked in the late 1930s,’ and ‘their rivalry was a productive force as the artists delibe rately drew upon previous work in their competitive exchanges, showing that they were highly aware of their shared history.’ Danielle Johnson, ‘Influence, Dialogue, Rivalry’. In Dalí & Magritt e, The Dali Museum, Ludion Publishers, St. Petersburg, FL., Brussels, 2018, p. 66.

14 According to Descharnes, the piece remained in the Dalí’s Paris apartment through the war, where Cécile Eluard was left in charge and ordered an inventory in case of an eventual seizure. Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus…’, Op. cit., p. 463.

15 Leslie Lieber, ‘The Mystery of Venus’s Arms’, This Week Magazine, 04/03/1962, p. 11; Robert Descharnes, Dali de Gala, Édita, Lausanne,1962, p. 165.

16 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, Dial Press, New York, 1942 (1961 ed.), p. 344; Leopold von Sacher Masoch, Vénus aux fourrures, Graphik Europa Anstalt, Geneva, 1970.

In the mid 1960s, the artist eventually shared with Descharnes personally that Marcel Duchamp had assisted with the technical aspects of the sculpture 'Duchamp a été au centre de tout l’affaire’ locating an unnamed plaster mold maker to fashion drawers after Dalí traced their locations. See : Robert Descharnes, Salvador Dalí: The…, Op. cit., p. 199; Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus…’, Op. cit., p. 462.

[1] Salvador Dalí, Venus de Milo with Drawers, 1936, painted plaster with metal pulls and mink pompons, 98 x 32.5 x 34 cm (38 ⅝ x 12 ¾ x 13 ⅜ in.), Through prior gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman, The Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.424

[2] Salvador Dalí, City of Drawers, graphite on buff wove paper, 352 x 522 mm, Gift of Frank B. Hubacheck, Art Institute of Chicago, 1963.3

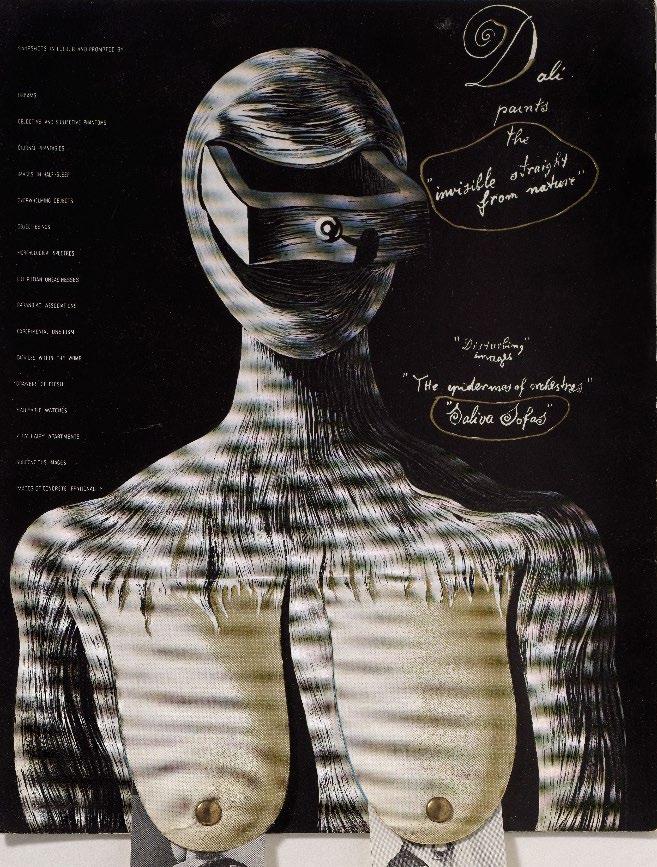

[3] Salvador Dalí, Cover for Minotaure, 8, 15/06/1936

[4] Eric Schaal, Installation with Venus de Milo with Drawers in the exhibition Salvador Dalí 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, 1939, current copy.

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 39

TRANSGRESSING VENUS

Dalí’s Drawers

Laura Bartolomé Roviras Curator at the Gala Salvador Dalí Foundation

‘The chaos in Spain undid me, and the monsters of civil war found their way on to my canvases. The double being of the “cannibalism of autumn” was eating itself up and sucking my blood. My father was to be persecuted, my sister almost lose [sic] her mind, my church steeple would be razed and countless friends would die! Death, nothingness, and the abjectness of hate were all about me. My paranoia critical system was going full blast. In the depths of despair, I continued to paint, turning vertigo into virtue. I produced the Vénus de Milo aux tiroirs (Venus with Opening Drawers) and the Cabinet anthropomorphique (Anthropomorphic Cabinet; also known as The City of Drawers).’

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 42

Salvador Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali (1973)1

With these memories, Dalí invites us to contextualise his Venus de Milo with Drawers at a very specific point of his biography: the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Dalí claims to have ‘invented’ this sculpture at a time when society and his own family were entering one of the darkest chapters of twentieth century history. His friend, Federico García Lorca, was executed in August 1936. During the war, his father a notary in Figueres, suffered professionally and the family’s source of income was jeopardised.2 In 1938, his sister, Anna Maria was accused of espionage, imprisoned, and tortured.

1936 was a crossroads in Dalí’s artistic career for several reasons. His work was shown in several collective and solo exhibitions in Paris and London and, in the second half of the year, mainly in the United States. There, his fame as an artist grew considerably. ‘My second voyage to America had just been what one may call the official beginning of “my glory”’3. These words give an idea of how close to success Dalí felt he was at the time. He arrived in New York at the beginning of December, by which time his work was being shown in the MoMA exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. Then he had a solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery and was also commissioned by the Fifth Avenue Bonwit Teller department store to create the window display She Was a Surrealist Woman She Was Like A Figure in a Dream. The critics and media spoke of the new artist’s talent, and Time magazine published Man Ray’s portrait of him on the cover of its 14 December issue.4 This image was, perhaps, the symbolic starting point of a new beginning, a gradual distancing from the surrealist milieu of Paris, and of Europe as well. In 1940, Gala and Dalí settled in the United States.

In around 1936, Dalí reflected on the nature of his work and adopted a new fiat: ‘My surrealist glory was worthless. I must incorporate surrealism in tradition. My imagination must become classic again. I had before me a work to accomplish for which the rest of my life would not suffice. Gala made me believe in this mission’5. This period, therefore, would have been that of the genesis of his certainty that tradition and classicism had to be the foundations of his work. However, Dalí also experienced it with a mixture of newly discovered feelings. He had, no doubt, longed for the fame and recognition he achieved after much work and effort in the ranks of surrealism, yet he was also suffering from a strange anxiety: ‘There is nothing the matter with me, there is nothing to produce this anguish. And yet I feel myself the slave of a growing anguish I don’t know where it comes from or where it is going! But it is so powerful that it frightens me!’6. The abjectness of the hate, the despair, and the vertigo of the Civil War would certainly have influenced his state. However, it did not limit his creative activity. On the contrary, his paranoiac critical system was ‘going full blast’.

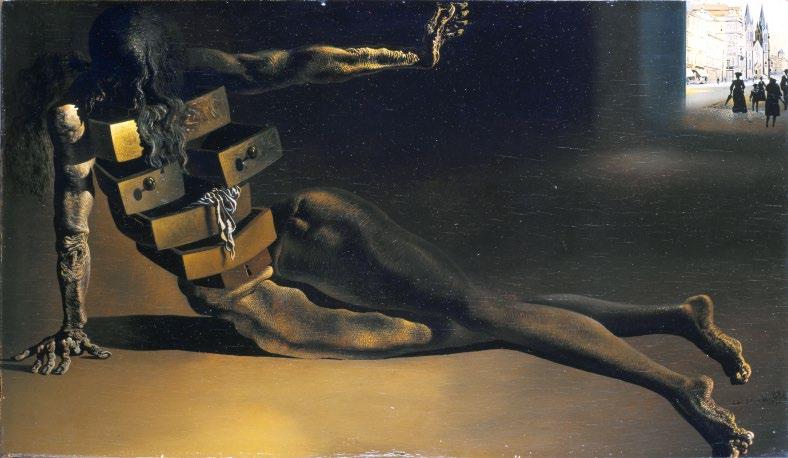

In this situation, Dalí gave greater prominence to drawers in his art, although they were not new to his work. They had already appeared in around 1934 1935 in Invisible Harp as well as in Singularities. Moreover, certain bureaus, with their drawers open, are to be found in other paintings dating from this period, for example, Portrait of Edward Wassermann, The Eviction of Furniture Nutrition, and Suburbs of a Paranoiac Critical Town He also refers to drawers in his literary work. In an article titled ‘Picasso’s Slippers’, which was published in Cahiers d’art in October 1935, he wrote of seeing ‘Picasso turn pale while, seated at the dining room table, he grabs an envelope from his sole meunière (envelope holder) with soft drawers, invented by Salvador Dalí’ 7 In fact, after mid 1936, Dalí’s drawers ceased to be occasional features and began to multiply in his work. In his solo exhibition of June and July

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 43

in the London gallery Alex Reid & Lefevre, he presented his City of Drawers [1], which is mentioned in the introductory quotation from The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali. The centrepiece of this painting is a woman sitting on the floor of a lugubrious room, with her head down and six drawers sunken into her body. In the catalogue of this exhibition [2], there is also an image of a human face with a bloodstained drawer, probably a ‘drawer of flesh’. This reference appears on the left side of the illustration as ‘Snapshots in colour and prompted by [...] Drawers of flesh’ 8

These colour photographs can be related with Dali’s 1935 definition of painting in The Conquest of the Irrational: ‘Instantaneous color photography done by hand of the superfine, extravagant, extraplastic, extrapictorial, unexplored, superpictorial, superplastic, deceptive, hypernormal, feeble images of concrete irrationality images that are provisionally unexplainable and irreductible by systems of logical intuition or by rational mechanism.’9 It is clear that, with this declaration, Dalí is also defining the functioning of his paranoiac critical method. Hence, if his ‘drawers of flesh’ can be identified as a certain kind of image of concrete irrationality, they can also be associated with the result of his genuine method. In fact, years later when the poet Selden Rodman asked Dalí if the fact of inserting a chest of drawers into someone’s belly is a distortion, Dalí replied that it is not, and described it as the most honest and photographic copy of one of his visions.10 The reference to ‘drawers of flesh’ appears once again in the Souvenir Catalogue of the Julien Levy Gallery, dated 1936 1937 [3].11 Dalí illustrated this catalogue with the naked, hairy bust of a woman whose face is disfigured by a drawer sunken into an enormous cavity. Among the works presented in this exhibition is

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 44

[1]

Autumnal Cannibalism, which is the other work referred to in the fragment heading this text. In this painting, a strange being, with drawers protruding from it, is devouring itself with spoons, forks, and knives. Dalí’s own comments in The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali suggest that it is reasonable to situate the creation of Venus de Milo with Drawers at this time.12 With this work, Dalí transgresses the body of the Greco Roman goddess, turning it into a classical bureau with six genuinely surrealist drawers, one in the head, two in the breasts, one in the abdomen, and another in a knee. Given all the above, could the drawers of Venus also be identified as ‘drawers of flesh’ and, therefore, as a certain kind of instantaneous colour photographs of Dalí’s concrete irrationality?

The fact is that, in the three works two paintings and one sculpture created by Dalí and also referred to by him in the context of the Spanish Civil War, a common denominator can be identified, namely beings penetrated by drawers. Drawers, ‘drawers of flesh’, instantaneous colour photographs of images of concrete irrationality… Dalí warns the reader that these photographs are the result of an experimental method based on systematic associations typical of paranoia. The resulting images in colour are not, in principle, explicable by means of rational mechanisms. Any understanding arises, if possible, a posteriori when the work already exists as a phenomenon. In short, this is how his paranoiac critical method works.

One of the most revealing statements in this regard is one Dalí offers in front of Venus de Milo with Drawers in Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, a documentary directed by Jean Christophe Averty. ‘So, as for the drawers, and now we’ll cover it with drawers, because the only difference between immortal Greece and the contemporary era is Sigmund Freud who dis

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 45

[2]

[3]

covered that the human body, which was purely neoplatonic in the time of the Greeks, is now full of secret drawers that only psychoanalysis can reveal.’13 The correlation between the drawers, the paranoiac critical method, and psychoanalysis is therefore absolute. Furthermore, the name Freud seems to appear marked on the installation that presented Venus de Milo with Drawers in New York in 1939.14 Throughout this year, Dalí kept introducing dra wers into the bodies of other figures in his works, as can be seen, for example, in the sets for the ballet ‘Bacchanale’ [4] and inside the Dream of Venus pavilion, which Dalí designed for the New York World’s Fair.

By the time Dalí created this sculpture, he was well acquainted with Freud’s work. He recalls in The Secret Life that he had begun to read his books during his time in the Students’ Residence in Madrid and it is likely that, by 1929, he had already read The Psychopathology of Everyday Life 15 In the section devoted to childhood and concealing memories, Freud describes a personal experience of a childhood memory about a ‘cupboard or chest’16 (in the Spanish version, the word is translated as cajón (drawer))17. As an adult, he remembers being very young, not yet three years old and screaming next to a ‘drawer’ that had been opened by his much older stepbrother. Finally, he managed to decipher the meaning of the memory of this occasion when, missing his mother, he was looking for her in a ‘drawer’ that his stepbrother had opened, and associating this with what the latter had told him when he was also missing the nanny who had suddenly disappeared after being arrested or ‘boxed in’, as his brother put it. When he couldn’t find his mother in the ‘drawer’, he screamed until she came home. This is a moving image and certainly representative of human vulnerability.

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 46

[4]

[5] [6]

The ‘content’ of the drawers of Dalí’s Venus, which can also be opened, remains unknown, and it is not easy to pinpoint the images of the concrete irrationalism that Dalí wishes to reveal with them. Nevertheless, some interpretations can be considered. ‘The Civil War is the torso of a woman torn apart with drawers’,18 says Luis Racionero in his Converses entre Pla i Dalí (Conversations between Pla and Dalí). It is true that the contemporaries of Venus de Milo with Drawers are women and men who have experienced, and are or will experience the conflagration first hand, as was the case with Dalí and his family. Might it be possible that the artist conceived the drawers as enablers for exploring the subconscious of a society that, far from the classical ideal embodied by the Venus de Milo, had been plunged into civil war? Spain, one of Dalí’s most heartfelt artistic protests about the war, shows a woman with her head down and supported by a bureau with a single open drawer. Although this painting is dated 1938, the preparatory drawing dates back to 1936 [6], and perhaps to the same context as that of Venus de Milo with Drawers

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 47

Footnotes

1 Salvador Dalí, Comment on devient Dali (1973). Salvador Dalí, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dali, William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York, 1976, p. 181.

2 Mariona Seguranyes Bolaños, Els Dalí de Figueres. La família, l’Empordà i l’art, Ajuntament de Figueres, Viena Edicions, Figueres, Barcelona, 2018, p. 124 130.

3 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, Dial Press, New York, 1942, p. 344.

4 Time. The Weekly News Magazine, vol. XXVIII, 14/12/1936, New York.

5 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life... Op. cit., p. 350. Although, in many cases, it is difficult to give a precise date to passages describing Dalí’s experiences in The Secret Life, this comment can probably be situated in around 1936.

6 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life Op. cit., p. 347.

7 Salvador Dalí, ‘Les pantoufles de Picasso’, Cahiers d’Art, 1935, p. 72 76. Publ.: Salvador Dalí, ‘Picasso’s Slippers’. In Haim Finkelstein (ed.), The Collected Writings of Salvador Dali, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998, p. 298

8 Salvador Dali, Alex Reid & Lefevre, London, 1936, p. [1].

9 Salvador Dalí, La Conquête de l'irrationnel (1935). Publ.: Haim Finkelstein (ed.), The Collected Writings… Op. cit., p. 265.

10 Selden Rodman, ‘Dali the Great?’, Controversy, 31/05/1959, Philadelphia, p. 14.

11 Souvenir Catalogue, Julien Levy Gallery, New York, [1936/37].

12 Robert Descharnes says that Dalí presented this sculpture in a private viewing on 19 June 1936 in his apartment at 101 bis rue de la Tombe Issoire in Paris, a fact that would establish an ante quem date for the creation of the work. See Robert Descharnes, ‘Dalí, la Vénus de Milo et la persistance de la mémoire antique’. In D’après l’Antique, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000, p. 463.

13 Jean Christophe Averty (dir.), Autoportrait mou de Salvador Dalí, RM Productions, Télévision Française, Henry R. Coty, 22/12/1972, min. 36:05 36:38 Author’s transcription and translation into Catalan.

14 According to the press of the day. See: Robert M. Coates, ‘The Art Galleries’, The New Yorker, 01/04/1939, New York, p. 56.

15 Salvador Dalí, The Secret Life... Op. cit., p. 167. Cf Vicent Santamaria de Mingo, ‘Salvador Dali lector de Freud 1927 1930. Una aproximación a las fuentes del pensamiento daliniano’, La Balsa de la Medusa, 47, 1998, p. 104

16 Sigmund Freud, Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens (1901). Publ.: Sigmund Freud, Psychopathology of Everyday Life, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1914. The English version using the word ‘chest’ may be accessed online at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/67332/67332 h/67332 h.htm [Last accessed: 01/10/2022]

17 See: Sigmund Freud, Obras completas: 1900 1905, Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid,1972, p. 786 787.

18 Lluís Racionero, Converses amb Pla i Dalí: localistes cosmopolites, Edicions 62, Barcelona, 2002, p. 89.

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 48

Illustrations

[1] Salvador Dalí, City of Drawers, 1936, oil on wood panel, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, Düsseldorf

[2] Exhibition catalogue Salvador Dalí, Alex Reid & Lefevre, London, 1936

[3] Salvador Dalí, Souvenir Catalogue, New York, Julien Levy Gallery, [1936/37] (detail).

[4] Salvador Dalí, Study for the ballet Bacchanale, c. 1939, pencil, Indian ink, and gouache on paper

[5] Hansel Mieth, Salvador Dalí and Edward James in the exhibition Salvador Dalí 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery de New York, 1939.

[6] Salvador Dalí, Study for Spain , 1936, pencil on paper

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 49

Catalogue

Centre for Dalinian Studies

SCULPTURE

PAINTING

Salvador Dalí

Venus de Milo with Drawers

1936/1964

Painted bronze 98,5 x 32,5 x 34 cm

Salvador Dalí

Venus de Milo with Drawers

Holographic creation based on the original sculpture

1936 Painted plaster with metal pulls and mink pompons 98 x 32.5 x 34 cm

The Art Institute of Chicago, Through prior gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman, Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.424

Salvador Dalí

Study for The Hallucinogenic Toreador c. 1969 Oil on canvas 58,5 x 44 cm

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 52

DRAWINGS

PREPARATORY MATERIAL

Salvador Dalí

Frontispiece for Second Manifeste du Surréalisme [André Breton]

1930 Phototype on paper 27,9 x 22,5 cm

Salvador Dalí

Untitled. Variations on the Symbols of the New York World’s Fair

1939 Pencil on paper 27 x 17,1 cm

Salvador Dalí Study for the ballet Bacchanale c. 1939

Pencil, Indian ink and gouache on paper 35,8 x 43 cm

Salvador Dalí

Progect for ‘mad TrisTan’ poetry of New York [Colliere] neurosis Artificial vampire organ of Babel wagner, GAudi Boecklin

Illustration for The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí

1939 1941

Ink on paper 22 x 28 cm

Salvador Dalí

Preparatory material for The Hallucinogenic Toreador c. 1969

Ballpoint pen on photograph 23,5 x 7,1 cm

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 53

PHOTOGRAPHS

Eric Schaal

Installation with Venus de Milo with Drawers in the exhibition Salvador Dalí 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York 1939 Current copy 23,9 x 17,8 cm

Eric Schaal

Installation with Venus de Milo with Drawers in the exhibition Salvador Dalí 1939 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York 1939 Current copy

23,9x 17,7 cm

Eric Schaal Façade of Dream of Venus in construction 1939 Period copy

20,4 x 20,5 cm

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí at the façade of Dream of Venus during its construction 1939 Period copy

25,3 x 20,5 cm

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí painting one of the murals inside Dream of Venus 1939 Period copy

25,4 x 20,6 cm

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí painting one of the murals inside Dream of Venus 1939 Period copy

25,5 x 20,6 cm

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí painting one of the murals inside Dream of Venus 1939 Period copy 20,6 x 25,4 cm

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí preparing one of the manne quins for Dream of Venus 1939 Period copy

25,3 x 20,5 cm

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 54

LEAFLETS

Eric Schaal

Salvador Dalí and Gala in the Rainy Taxi 1939 Period copy 25,2 x 20,7 cm

Eric Schaal

Ceiling of umbrellas inside Dream of Venus 1939 Period copy 23,7 x 20,6 cm

Venus de Milo with Drawers inside a modernist style cabinet reclinatory

Posterior to 1962 Period copy 29,8 x 19,7 cm

Salvador Dalí Souvenir Catalogue [1936 1937] 25,9 x 19,7 cm

Salvador Dalí Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness 1939 38,2 x 22,4 cm

Invitation to the opening of the exhibition Salvador Dalí at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris 1979 21 x 10,4 cm

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 55

BOOKS AND MAGAZINES

Salvador Dalí

Cover of Minotaure Magazine

1936 31,4 x 24,5 cm

Time Art

Photograph of Dalí’s Venus de Milo with Drawers at the exhibition Panathenaia of Sculpture in Athens 1965 28 x 21,3 cm

Robert Descharnes, Clovis Prévost

La Vision artistique et religieuse de Gaudí

Prologue by Salvador Dalí 1969 30,7 x 26,5 cm

TRANSGRESSING VENUS 56

DALÍ IS CLASSICAL, IS SURREALIST, IS POP ART! 57

Salvador Dalí, Study for the façade of Dream of Venus, 1939