12 minute read

Keeping Them Pearly White and Smooth

from FVMA Advocate Issue 1, 2020

by FVMA

KEEPING THEM PEARLY WHITE AND SMOOTH PERIODONTOLOGY FOR THE DENTAL TECHNICIAN

Advertisement

Periodontal disease is the most common small animal ailment. Eight out of 10 dogs and cats older than five will suffer from periodontal disease. If periodontal problems are left untreated, bacteria and toxins can be absorbed into the blood stream and, in some instances, can cause permanent damage to internal organs, decreasing the pet’s life span.

Periodontal disease starts with plaque, which attaches to teeth and gingival surfaces. Plaque is primarily composed of bacteria, white blood cells, and saliva. When removed daily, plaque doesn’t cause problems. If left to accumulate, mineral salts in saliva mix with plaque, forming hard calculus. Without daily plaque removal, more plaque accumulates on top of the calculus, extending under the gingiva. At first, there is little difference between the bacteria above (supragingival) and below (subgingival) the gingival margin in healthy sites. Most supragingival plaque bacteria are gram positive, non-motile, aerobic cocci. As periodontal infection progresses, destructive gram-negative, motile, anaerobic rods predominate.

Disease predisposition The cause of periodontal disease is multifactorial. Many elements factor into the equation of why some small animals develop disease, while others do not. Some of the most common criteria that predispose some animals to periodontal disease include:

• Breed- small breeds are more prone to periodontal disease due to the proximity of the teeth and the relative thinness of the bone around the incisors. • General health- animals that have compromised health or that are immunologically suppressed cannot fight periodontal pathogens effectively. • Dermatological disease- animals with dermatological disease many times chew at their coat, embedding hair under the gum line and, thereby, promoting periodontal disease. • Nutritional health- animals on a poor diet often have less immunity to disease. • Age- older pets are more prone to periodontal disease.

Ultimately, the destruction of tooth support (periodontium) is responsible for the loss of teeth. The height of the alveolar bone is normally maintained by an equilibrium between bone formation and bone resorption. When resorption exceeds formation, bone height is reduced. In periodontal disease, the equilibrium is altered, so that bone resorption exceeds bone formation. Plaque-laden calculus plays a key role in maintaining and accelerating periodontal disease. When calculus extends deep into the subgingival tissues, the potential for repair and reattachment is lost without medical or surgical intervention. The therapeutic importance of plaque and calculus removal by the veterinarian and follow-up home preventative care by the client cannot be overemphasized.

The periodontal exam Periodontal pockets result when the periodontal ligament loses part, or all, of its attachment to the tooth. The periodontal pocket is defined as a pathologically deepened gingival sulcus. The clinical pocket depth is defined as the distance from the free gingival margin to the base of the pocket. Diagnosing periodontal disease and assessing the response to treatment are, in part, based on pocket depth measurement. The measurement of clinical pocket depths by a probe is the backbone of a thorough periodontal examination.

The periodontal probe is marked in millimeter gradations and gently inserted in the space between the gingival margin and the tooth. A probe will stop where the gingiva attaches to the tooth, or at the apex of the alveolus, if the attachment is gone. Mediumsized dogs without periodontal disease should have less than 2 mm probing depths, and cats should have less than 1 mm. Each tooth is probed on a minimum of four sides. Abnormal probing depths of all teeth should be noted on the dental record, and a treatment plan should be mapped out before therapy begins.

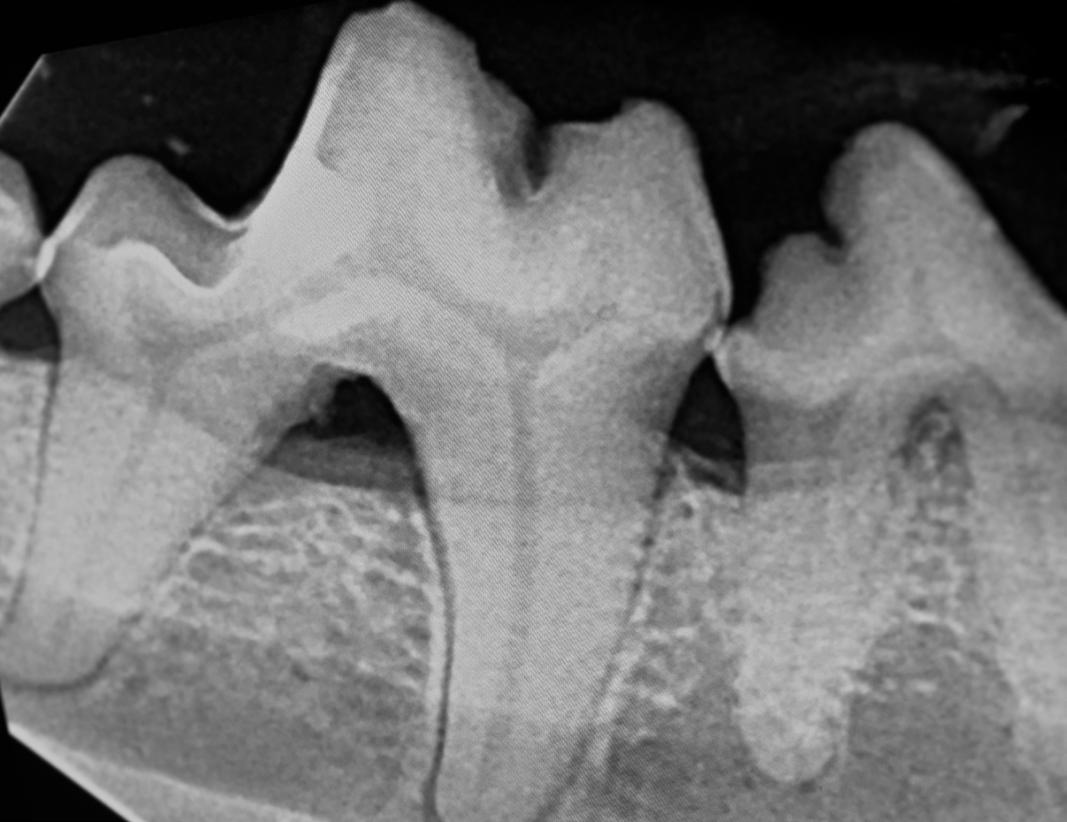

Gingival recession involving the left maxillary fourth premolar, extraction is indicated. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jan Bellows

Gingival recession occurs secondary to bone loss. Recession is the exposure of the root surface caused by a shift in the position of the gingiva toward the root. Recession may be visible where the root is clinically observable, or hidden where the root is covered by minimally adhered gingiva. Hidden recession can be measured by inserting a probe down to the level of epithelial attachment and/or by evaluating radiographs.

Oronasal fistulas result from periodontal disease of the maxillary teeth, resulting in communication between the oral and nasal cavities. In cases of oronasal fistulas, a periodontal probe will usually extend from the oral cavity through the nasal cavity. Most commonly, the maxillary canine teeth are affected. Clinical signs include sneezing and nasal discharge, which is sometimes blood tinged.

Gingivitis vs. Periodontitis Understanding the difference between gingivitis and periodontitis is critical when formulating a treatment plan. Gingivitis is an inflammatory syndrome affecting the soft tissue. Gingivitis does not clinically extend into the alveolar bone, periodontal ligament, or cementum. Periodontitis, on the other hand, is an inflammation involving the periodontal ligament, the alveolar bone, and the cementum. Periodontitis is present once bone loss occurs; all cases of periodontitis start with gingivitis. The distinction between gingivitis and periodontitis is important because gingivitis is considered curable with teeth cleaning and home care, whereas periodontitis is merely considered controllable and progressive. Gingivitis. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jan Bellows

There are four stages of periodontal disease that are clinically recognizable.

The degree of severity of periodontal disease relates to a single tooth; a patient may have teeth that have different stages of periodontal disease.

Normal (PD 0): Clinically normal - no gingival inflammation or periodontitis clinically evident.

Stage 1 (PD 1): Gingivitis only without attachment loss. The height and architecture of the alveolar margin are normal. Stage 2 (PD 2): Early periodontitis - less than 25% of attachment loss or, at most, there is a Stage 1 furcation involvement in multirooted teeth. There are early radiologic signs of periodontitis. The loss of periodontal attachment is less than 25%, as measured either by probing the clinical attachment level, or by radiographic determination of the distance of the alveolar margin from the cemento-enamel junction relative to the length of the root.

Stage 3 (PD 3): Moderate periodontitis - 25-50% of attachment loss, as measured either by probing of the clinical attachment level, or by radiographic determination of the distance of the alveolar margin from the cemento-enamel junction relative to the length of the root, or there is a Stage 2 furcation involvement in multirooted teeth.

Stage 4 (PD 4): Advanced periodontitis - more than 50% of attachment loss, as measured either by probing of the clinical attachment level, or radiographic determination of the distance of the alveolar margin from the cemento-enamel junction relative to the length of the root, or there is a Stage 3 furcation involvement in multirooted teeth.

Furcation invasions occur secondary to periodontal disease. The furcation is the area between the roots of a multirooted tooth, formed where the roots begin to separate at the floor of the trunk. Normally, this area is sealed off from the oral environment by the gingival attachment. The area of bifurcation or trifurcation is exposed when periodontal disease causes bone loss. When left untreated and allowed to progress, the furcation invasion may result in tooth loss. There are three clinical furcation classifications distinguished by the use of an explorer probe.

Furcation involvement/exposure definitions • Stage 1 (F1, furcation involvement) exists when a periodontal probe extends less than halfway under the crown, in any direction of a multirooted tooth, with attachment loss. • Stage 2 (F2, furcation involvement) exists when a periodontal probe extends greater than halfway under the crown of a multirooted tooth with attachment loss, but not through and through.

F3 furcation in a cat’s left maxillary fourth premolar. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jan Bellows

F3 furcation exposure affecting a dog’s right first molar. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jan Bellows

• Stage 3 (F3, furcation exposure) exists when a periodontal probe extends under the crown of a multirooted tooth, through and through from one side of the furcation out the other.

Tooth mobility • Stage 0 (M0) Physiologic mobility up to 0.2 mm. • Stage 1 (M1) The mobility is increased in any direction other than axial over a distance of more than 0.2 mm and up to 0.5 mm. • Stage 2 (M2) The mobility is increased in any direction other than axial, over a distance of more than 0.5 mm and up to 1.0 mm. • Stage 3 (M3) The mobility is increased in any direction, other than axial, over a distance exceeding 1.0 mm or any axial movement.

Radiographs are helpful when identifying furcation involvement. The slightest radiographic change in the furcation area should be investigated clinically. Diminished radiodensity in the furcation area suggests furcation involvement.

The importance of intraoral radiology Intraoral radiography supplies valuable information to the veterinarian, when evaluating the tooth’s support structure. Radiographic examination is crucial in all cases of periodontal disease.

Gingivitis- Clinically, the gingiva appears swollen and inflamed. In Stage 1 disease, no bone loss has occurred yet, and dental radiographs appear normal.

Early periodontitis- Stage 2 disease indicates early periodontitis and signifies the first appearance of radiographic abnormalities. The earliest radiographic sign of periodontitis shows a loss of definition of the crestal bone. The alveolar crest loses its distinct, sharp appearance and becomes blunted. The bony margin becomes diffuse and irregular, and may demonstrate areas of localized erosion. In the incisor regions, there will be a blunting of the alveolar crests.

Moderate periodontitis- Stage 3 periodontal disease is typified by pocket formation. Radiographically, the bony destruction extends to the alveolar bony plate. There may also be horizontal or vertical defects. Horizontal bone loss is used to describe the radiographic appearance of the loss of bone height in the region of several adjacent teeth. Vertical bone defects are also called “intrabony defects.” This defect extends from the alveolar crest, and is surrounded by either one, two, or three walls of bone.

Advanced periodontitis- Deep pockets represent advanced periodontal lesions typified by Stage 4 periodontal disease, tooth mobility, gingival bleeding, and pustular discharge. Bone loss is extensive.

Steps of professional teeth cleaning In the long run, no other procedure performed on small animals does more to help patients than periodic teeth cleaning and aftercare. The dental visit for cleaning, however, must be performed in a methodical manner. All 12 of the following steps are important and interlinked. When one step is not performed, long-term benefit to the patient suffers. 1. Conscious oral evaluation 2. Anesthetized intraoral radiography 3. Teeth scaling 4. Crown polishing 5. Periodontal probing 6. Subgingival irrigation

7. Periodontal therapy or extractions 8. +/- antibiotic therapy 9. Antiplaque sealant application 10.Oral mass biopsies 11.Anesthesia recovery 12.Home care education

Medical vs. surgical therapy • Grade 1 gingival and Grade 2 periodontal disease can be treated non-surgically. Once the teeth are cleaned, polished, fluoridated, and home care rigidly followed, gingivitis will recede, returning the gingiva to normal appearance and function.

• Grade 3 periodontal disease may require some surgical care, based on the amount of attachment loss. If the periodontal probe depth is not greater than 5 mm, often the tooth root can be cleaned thoroughly with hand instruments and/or special ultrasonic scaler tips for subgingival use. Root planing- When calculus is removed from the root surface, the cementum is often left rough. Root surfaces exposed to periodontal disease is covered with bacterial plaque and endotoxins. Root planing will smooth these roughened surfaces by shaving the root surface down with a curette. Obviously, smooth surfaces are easier to keep clean than rough ones. The smooth surface will also adapt easier to the cleaned pocket, thus reducing the pocket depth. Subgingival curettage involves removing the lining of the periodontal pocket as well as damaged tissue. Subgingival curettage is performed with curettes, following plaque and calculus removal. Scaling, root planing, and curettage can be quite effective as definitive treatments in cases of periodontal disease that have a slight amount of tissue destruction, particularly where there is pocketing of 4-6 mm. The combination of tissue shrinkage, connective tissue remodeling, and gain of soft tissue attachment makes these procedures viable options. Instillation of Clindoral® or Doxirobe ®, in areas of Stage 2-3 support loss has been shown to decrease pocket depths.

• Grade 4 periodontal disease requires surgical careextraction.

LESION APPEARANCE TREATMENT

Stage 1 Gingivitis Plaque/calculus at gumline inflammation Under anesthesia removal of supra and subgingival calculus, irrigation, full mouth radiographs charting, home care instructions, set follow-up

Stage 2 Early Periodontitis < 25% support loss Same as above, +/- instillation of local antimicrobials into cleaned pockets

Stage 3 Moderate Periodontitis 25-50% support loss Same as above, plus root planing in pockets

Stage 4 Advanced Periodontitis >50% support loss Same as above, plus curettage and surgery to either save the tooth through flaps, guided tissue regeneration, or extraction

Oronasal Fistula Communication between the mouth and nasal cavity (some animals will have a nasal discharge) Extraction of the affected tooth, plus closure of defect with single or double flap technique, without tension on the suture line

Furcation Invasions Gingival recession to exposure of a void at the area where the roots bifurcate or trifurcate If the furcation is exposed on both ends (buccal and lingual/palatal), extraction is indicated

Marked Gingival Recession Greater than 50% of the root exposed Perform either intraoral radiographs to confirm extraction or advanced periodontal surgery

Jan Bellows, DVM, DAVDC, DABVP (Canine and Feline) Dr. Jan Bellows received his undergraduate training at the University of Florida and his Doctorate in Veterinary Medicine from Auburn University. After completing a small animal internship at The Animal Medical Center in New York City, he returned to South Florida where he still practices companion animal medicine surgery and dentistry at All Pets Dental in Weston, Florida. He is certified by the Board of Veterinary Practitioners (canine and feline) since 1986 and American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC) since 1990. He was president of the AVDC from 2012-2014 and is currently president of the Foundation for Veterinary Dentistry. Dr. Bellows’ veterinary dentistry accomplishments include authoring four dental texts: The Practice of Veterinary Dentistry …. A team effort (1999); Small Animal Dental Equipment, Materials, and Techniques (2005, second edition 2019); and Feline Dentistry (2010). He is a frequent contributor to DVM Newsmagazine and a charter consultant of Veterinary Information Network’s (VIN) dental board since 1993. He was also chosen as one of the dental experts to formulate AAHA’s Small Animal Dental Guidelines, published in 2005 and updated in 2013 and 2019.