MEMBER

DR. ANNE

VMD, MS, CVSMT, CVA

ANESTHESIA FOR DONKEYS AND MULES

NORA S. MATTHEWS

DVM, DACVAA

JILL K. MANEY

VMD, DIPL. ACVAA

MEMBER

DR. ANNE

VMD, MS, CVSMT, CVA

ANESTHESIA FOR DONKEYS AND MULES

NORA S. MATTHEWS

DVM, DACVAA

JILL K. MANEY

VMD, DIPL. ACVAA

Greetings fellow practitioners,

RUTH-ANNE

I hope you had a busy and productive spring. Remember to take some time this summer to enjoy yourselves and your special people.

We have exciting continuing education (CE) opportunities in the form of Ocala Equine Conference (OEC), this July 22-24, and our Promoting Excellence Symposium (PES) October 6-9. We are excited to be back in Ocala, “the horse capital of the world,” offering an engaging array of CE opportunities in a location convenient for many. This year, we are also looking forward to a new location, the Sawgrass Marriott, for PES as this venue offers many opportunities for extracurricular activities.

We hope to see you all there and are sure that our world-class, equine-exclusive conferences will provide you with enriching learning and networking opportunities.

ADAM CAYOT DVM adamcayot@hotmail.com

Hopefully, this is the last time our meetings will be shuffled due to COVID or any other unforeseen circumstances.

We look forward to seeing you at OEC 2022 or PES 2022!

COREY MILLLER DVM, MS, DACT cmiller@emcocala.com

ANNE

Armon Blair, DVM FAEP Council President

SALLY DENOTTA DVM, DACVIM, PhD REPRESENTATIVE TO FVMA EXECUTIVE BOARD s.denotta@ufl.edu

A NOTE FROM YOUR FVMA TEAM: Your Florida Veterinary Medical Association (FVMA) team thanks you for being a member and values your contributions to helping us progress veterinary medicine. We're proud to present this publication as a part of your membership benefits. If you have questions regarding your membership or your reception of this publication, please contact the FVMA/ FAEP at 800.992.3862 or email membership@fvma.org

If anyone is struggling with mental wellness, please do not hesitate to reach out to colleagues, friends, or the FAEP (call 800.992.3862).

We have instituted our Membership Assistance Program (MAP), which is free for all members. MAP offers personal and professional consultation to help you be your best. For more information, email info@fvma.org

Opinions and statements expressed in The Practitioner reflect the views of the contributors and do not represent the official policy of the Florida Association of Equine Practitioners (FAEP) or the Florida Veterinary Medical Association (FVMA), unless so stated. Placement of an advertisement does not represent the FAEP’s or FVMA’s endorsement of the product or service.

Longtime dual Florida Veterinary Medical Association/Florida Association of Equine Practitioners (FVMA/FAEP) member and FAEP council member, Dr. Anne Moretta’s life has been defined by a lifelong love for horses. From pony rides to a professional show career and veterinary school, Dr. Moretta puts decades of skill and knowledge into her veterinary practice at Wellington Equine Sports Medicine. Here, she believes in a comprehensive approach to helping horses achieve their full potential: looking at the big picture, helping the whole horse, finding root causes for poor performance, and using an arsenal of remedies nearly as vast as her career experience.

“My parents told me that before I could walk, I would insist on going on every pony ride we saw,” Dr. Moretta said. “Growing up in the Northern Virginia-Maryland-D.C. area, all of my weekends revolved around riding. I was always trying different styles of riding, different breeds of horses, and every discipline I came in contact with.”

When she was younger, Dr. Moretta was in the stables every day after school and later, after work. She showed every weekend in junior and working hunters and rode as a professional in the ring and hunter field through college. During her college years, she also exercised Thoroughbred racehorses at Belmont racetrack.

“I have always had a good intuition for being able to sense what is bothering a horse, and I became very good at sensing subtle problems from my time watching so many horses at the Thoroughbred and Standardbred tracks,” she recalled. "Some of my favorite moments have been sitting behind a horse jogging at sunrise in South Florida."

After graduating college early, she stayed on to do her masters work while continuing to train horses for three-day eventing, hunting and showing on the side. During this time, she began working with an equine vet who shined a light on her future career path by suggesting she "make her avocation her full-time vocation and go to vet school." Immediately following his advice, she headed to the University of Pennsylvania for veterinary school.

During her time there, she continued to, train, buy, sell, breed, and ride horses as often as she could. Buying and selling helped her pay for many of her vet school expenses. At one point, she even bought the Radnor Hunt Master’s horse, Cyrano.

"I was never able to replace that wonderful horse and retired him to the farm in Pennsylvania where he lived to 45 and his pony companion to 42. He was a large Draft Thoroughbred cross who if he could not jump the 'trappy' fence, he would simply clear his way straight through the fence, leading the way for the rest of the hunt field! He taught me to not just hear, but to truly listen with all my senses—and to hang on..."

Dr. Moretta's first year in practice was a dichotomy of two worlds— working with high-end stakes Thoroughbred racehorses, Amish road horses and breeding farms.

Dr. Moretta’s skills were put to the test right out of veterinary school when her boss became unable to work halfway into her first year.

“I basically just graduated vet school and was now doing all of the high-end lameness and breeding work alone... I was so fortunate that my veterinary school community was so supportive,” she said. “Several of my veterinary instructors at University of Pennsylvania Veterinary School would come out on weekends to the practice. They would help me do lameness checks, surgical procedures, injections, reproductive work, etc. to further my education and support my solo work in the practice until my employer was able to work again. They were pillars of selfless giving.”

Following her busy first year, she went on to open her own practice in Pennsylvania, Maroche Equine Clinic, which rapidly grew thanks to a retiring veterinarian putting Dr. Moretta's name and phone number on his machine to refer his clients to her. Dr. Moretta's practice included working with Thoroughbred and Standardbred racing, all aspects of sports medicine, breeding, and the yearling and racehorse sales industry. The next step was to establish Maroche Equine Consulting. Dr. Moretta used her diverse background and business skills to help her clients buy, sell, and race their horses around the world. She personally bred, raised, and sold over twenty Standardbred yearlings of her own at different venues over the years.

Her experiences and course work/externships traveling abroad for many years introduced her to equine acupuncture and chiropractic work, where she found her niche by using eastern medicine to complement the sports medicine skillset she already employed in the US. With new knowledge and Maroche Equine Sports Medicine in Pennsylvania, she followed her sportshorse niche to work in Wellington, Florida, integrating the two practices to establish Wellington Equine Sports Medicine.

Dr. Moretta brings a special approach not only to her sports medicine and rehabilitation practice, but also to her involvement in the veterinary community.

"Communication and education are paramount in veterinary medicine at any level, " Dr. Moretta said. "Mentoring and encouraging college students to go to veterinary school through positive experiences, in the office or field, is important."

In 2000, with great compassion, Dr. Moretta established Stony Run Veterinary Center (small animal) on a neighboring property to Maroche Equine Clinic. Dr. Moretta and her late husband wanted to give a young, talented veterinarian, Dr. Katherine Chronister, a chance to own her own practice, which she would not have had the opportunity to do where she was working at the time.

In 2006, prior to its merging with FVMA, Dr. Moretta joined the FAEP.

"Our FAEP council members continue to be strong, motivated individuals who come from varied equine practices and backgrounds," Dr. Moretta said of the FAEP. "Our common goals focus on organizing quality educational programs for our members. I truly enjoy the team-oriented environment of our FVMA/FAEP symposiums and our participating members who support us."

Though most of her time is now spent with clients’ horses, she still rides and raises Hanoverians and miniature spotted donkeys.

Dr. Moretta continues to also make time for her larger veterinary community by serving on the FAEP executive council and as the advising veterinarian of The Practitioner, the FAEP/FVMA’s equine-exclusive veterinary publication. In this role, she helps curate content and ensures relevant articles are published. Her involvement has been invaluable to the Florida equine veterinary community and the many lives she has touched along the way.

"I believe we are at crossroads in veterinary medicine," Dr. Moretta says when looking at the future. "There are many new challenges on the horizon as to how we will practice and deal with change. In particular, mental wellness is a challenge in the profession, and it is vital we do all we can to help ensure there is 'Not one more vet' (NOMV) lost - Please support NOMV. As a large, diverse professional group, we all have the opportunity to support each other through effective communication, legislation, and education. We need everyone to be an active participant. I strive daily to be involved and help shape future change. From participation with 4H to encouraging and mentoring veterinary students to connecting with fellow veterinarians—my door is always open. Will you accept the challenge?"

Legislative advocacy is a key benefit provided to all FAEP members, where we fight for your profession in Tallahassee and in Washington, D C to ensure legislation affecting all veterinary medicine (including small animal, large animal, and equine) is fair to those who practice it

The FVMA Professional Advocacy Committee (PAC) is a bipartisan, nonprofit, political committee formed to raise contributions from our members and provide needed financial support for lobbying efforts

Every dollar raised for the PAC funds legislative efforts in favor of veterinary professionals, small business owners and the animals entrusted in your care. Both our lobbyists and the local and state legislators that we choose to support are aligned with our values.

Contributing is the best way to get involved and directly impact the legislative condition of veterinary medicine in Florida Scan the QR code to donate and help create a brighter future for all of us.

You can learn more about our legislative initiatives by visiting fvma org/advocacy

We would like to thank our FAEP Educational Partners for their support of our mission to provide the highest-quality, equine-exclusive continuing education in the Southeast.

Our partners are instrumental in developing an enriching educational environment within the FAEP, whether in the form of The Practitioner, our conferences, and a host of additional offerings throughout the year. We are energized by their enthusiasm for equine education and are excited about our joint potential as we look to the future.

Our incredible partners include:

The FAEP invites you to Ocala, Florida, “The Horse Capital of the World,” from July 22-24, 2022, for its world-class program of cutting-edge lectures and hands-on instruction.

Ocala is the proud home of the facility and personnel who were instrumental in the early training of American Pharoah, the first horse to win the “Grand Slam” of American horse racing, the Triple Crown and Breeders’ Cup Classic, in 2014. Ocala also has some of the leading equine veterinary practices that provide state-of-the-art veterinary care to their patients.

This is an exciting opportunity for equine professionals to gather in Florida’s horse country for their CE and to network with colleagues as well as with representatives of the business sector who will showcase their products and services in the engaging Exhibit Hall.

We look forward to welcoming you to Ocala, July 22-24, 2022!

HILTON OCALA

3600 SW 36th Ave.Ocala, FL 34474

www.hiltonocala.com

Telephone: 352.854.1400

Fax: 352.854.4010

Special room rates available through June 20, 2022, or until block is SOLD OUT. Reserve your room today!

Telephone: 352.854.1400

Group Code: FVMA

AAVSB RACE, CE Broker Provider #50-27127

Approval RACE Program #20-865863

Sponsor of Continuing Education in New York State

Florida Board of Veterinary Medicine, DBPR FVMA Provider #0001682

AAVSB RACE

This program #20-865863 (CE Broker #50-27127) is approved by AAVSB RACE to offer a total of 25 CE credits in jurisdictions that recognize RACE approval with a maximum 25 CE credits available to veterinarians and 17 CE credits available to veterinary technicians.

Friday, July 22 | 8 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Wet lab fees include:

• Breakfast and lunch

• Expert instruction

• Transportation to/from Hilton Ocala and Equine Medical Center of Ocala

• Rotation through all five stations

Sponsors:

$695 WET

$895 WET LAB ONLY

NORA S. MATTHEWS | DVM, DACVAA

JILL K. MANEY | VMD, DIPL. ACVAA

Although a member of the equine family, donkeys and mules can be difficult for the equine practitioner to deal with for several reasons. Behavioral, anatomical, and physiologic differences are minor but significant in our management of donkeys and mules.

Behavioral differences between horses and donkeys will be most obvious in donkeys which have had little handling or training. When well trained, they are very easy to work around. Donkeys do not have the same flight response as the horse; when confronted with something new, they will usually freeze until they have had a chance to observe it (hence their reputation for stubbornness). Patience is required when trying to get them to do something new, like enter a stock. They are also not as easily “bullied” into movement as horses are so be prepared to wait! A nose twitch is often ineffective in restraining donkeys (partially because it usually slides off the nose). However, they may be adequately restrained by snubbing the head rope securely to a stout fixed object.

Mules are generally more difficult to work around than donkeys (unless well trained) and, because of their larger size, may be more dangerous; it is strongly recommended to have an experienced mule handler available when working around untrained mules. Both mules and donkeys kick without warning and with great accuracy.

Both donkeys and mules are very stoic making it difficult to assess illness; it is likely that they will be much sicker or more painful than casual observation would lead one to conclude. There is a myth that says that donkeys and mules don’t colic. This is not true, but mild bouts of colic are probably never observed because of their stoic nature. The animal may be significantly ill before being presented for treatment or surgery, thus the patient is a worse anesthetic risk.

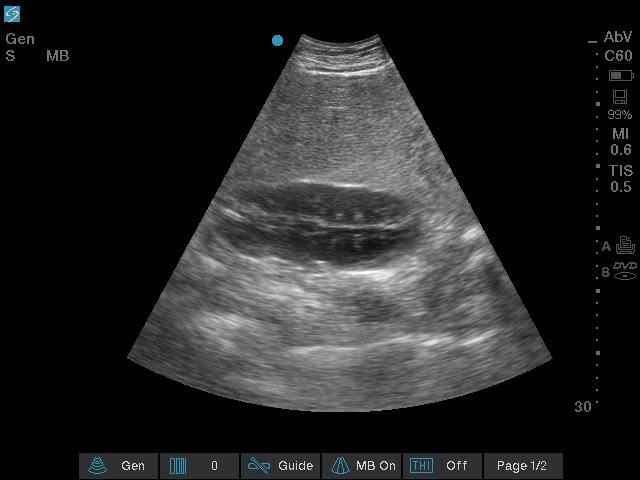

The most striking anatomic difference is observed when trying to give jugular injections or place catheters. While the jugular vein lies in the same position as in the horse, donkey skin is thicker, and there is a thick layer of fascia covering the entire neck (Figure 1). It is like hitting the jugular on a cow. Add to this the fact that donkeys and mules don’t tolerate numerous attempts to hit the vein. This author (NM) has had good luck giving Dormosedan gel to unhandled donkeys and mules (at the horse-label dose) to provide sedation prior to anesthesia (Figure 2).

Numerous physiological differences have been identified between donkeys and horses. Donkeys are desert-adapted and their fluid balance is different; this probably accounts for the shorter half-life of various drugs seen in donkeys.

Adequate preoperative analgesia should be achieved especially for very painful (e.g., orthopedic) conditions. Failure to provide preoperative analgesia may result in serious cardiovascular collapse soon after induction of anesthesia. This is probably no different than what is seen in horses with chronically painful conditions (e.g., chronic laminitis), but it is easier to recognize severe pain in horses, so it is more likely to be treated prior to anesthesia. Donkeys require higher dosages of NSAIDs or

shorter dosing intervals to achieve the same degree of analgesia since they metabolize many drugs more rapidly than horses. This is especially true of miniature donkeys, which metabolize flunixin more rapidly than standard donkeys. Under-treatment of pain in donkeys can easily occur because pain is not easily recognized and differences in drug metabolism are not known.

All of the same sedative and premedications used in horses have been used in donkeys and mules with relatively good results. Generally, mules require 50% more drug than donkeys or horses to achieve adequate sedation. Standing procedures can be accomplished with the same sedatives (e.g., acepromazine/ xylazine; xylazine/butorphanol) used with lidocaine locoregional techniques as would be used for horses. As is also seen with horses, larger doses (2-3 times) may be necessary for excited or feral equids. Route of administration will also affect the dose required; generally twice the dose is required when the IM route is the only one possible. The same precautions should be observed with sedated mules or donkeys as for horses; they are still capable of biting or kicking! It is also not uncommon for donkeys to lie down on a preanesthetic dose of xylazine; they do not fall down, but will deliberately lie down when they feel uncoordinated. Induction drugs can be administered with the donkey in sternal recumbency. Medetomidine (10 mcg/kg) or dexmedetomidine (5 mcg/kg) also provide good sedation.

As with horses, a smooth induction is only achieved when the donkey or mule is adequately sedated before administering induction drugs. In general, induction is easier to accomplish because of the small size of most donkeys and some mules. A variety of drugs can be used for induction and maintenance with injectables. Ketamine (following sedation with an alpha-2 agonist) works well, but is metabolized more rapidly in donkeys and mules than in horses, so higher doses or shorter dosing intervals must be used. This is especially important in miniature donkeys where a surgical plane of anesthesia will

not be achieved with horse doses of xylazine and ketamine. If repeat administration of ketamine (by bolus or infusion) is not possible, a local block with lidocaine will ensure adequate analgesia during the latter stage of the procedure even if the donkey is awake. The addition of butorphanol will produce a slightly longer period of anesthesia and improved analgesia.

The combination of guaifenesin with xylazine and ketamine will produce smooth induction and maintenance in donkeys when used in the following manner: premedicate the donkey with xylazine (1.1 mg/kg IV) or equivalent dose of an alpha-2 agonist (e.g., romifidine or detomidine). Induce by rapid infusion (gravity flow) of 1 liter 5% guaifenesin with 2 grams ketamine and 500 mg xylazine mixed in (Figure 3). Once the donkey has become recumbent, slow the infusion to approximately 1 ml/kg/ hr (based on monitoring eye signs, respiratory rate, and pattern). Donkeys are more sensitive to the respiratory depression of guaifenesin, this mix delivers more ketamine (which is more rapidly metabolized) with less guaifenesin. For mules, induction can be accomplished with xylazine (1.6 mg/kg IV) followed by ketamine (2.2 mg/kg IV); then the G-K-X can be used for maintenance of anesthesia. Ketamine (3 mg/kg) may also be combined with diazepam or midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) for a smooth induction to anesthesia.

Other anesthetic drugs which have been used in donkeys and mules are tiletamine-zolazepam (Telazol), propofol, and alfaxalone. Telazol will provide a slightly longer period of anesthesia and is recommended for miniature donkeys. Propofol can be used for induction and maintenance in donkeys, following sedation with xylazine. Since apnea and desaturation are common problems with propofol, it is not recommended for use unless tracheal intubation and oxygen supplementation is available. Alfaxalone (1 mg/kg) provides a smooth and rapid induction to anesthesia when combined with midazolam (0.05 mg/kg) in donkeys. Intermittent boluses of alfaxalonexylazine may be used for maintenance of anesthesia; however, supplemental oxygen must be provided to prevent hypoxemia. Recovery from alfaxalone is acceptable, but longer and less smooth than recovery from ketamine.

Figure 4. Inhaled anesthetics and careful monitoring should be used for longer procedures.

Image courtesy of Drs. Nora Matthews and Jill K. Maney.

Figure 4. Inhaled anesthetics and careful monitoring should be used for longer procedures.

Image courtesy of Drs. Nora Matthews and Jill K. Maney.

Endotracheal intubation and maintenance with inhalant anesthetics is preferred for longer procedures. Endotracheal intubation is usually easily achieved in the same manner as in horses; on occasion, it may be necessary to use a slightly smaller endotracheal tube especially if the depth of anesthesia is not sufficient to produce good conditions for intubation. Additional induction drugs should be available to deepen anesthesia if required. Miniature donkeys (especially those with dwarf-like features) may have hypoplastic tracheas and abnormal airway anatomy as can be seen with some (dwarf-like) miniature horses.

Minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) values for isoflurane in donkeys appear to be similar to those of horses, so vaporizer settings should be similar. The MAC-value for sevoflurane has not been determined in donkeys and mules; our clinical experience seems to indicate that the same vaporizer settings can be used in donkeys and mules as in horses. However, as always, the patient should be appropriately monitored and settings adjusted based on physiological parameters and depth of anesthesia. It should be stressed again that there is less published information about mules, and they may be more variable than donkeys.

As previously mentioned, one of the authors (NM) has observed several donkeys that suffered from serious cardiovascular collapse (bradycardia and profound hypotension which responded to anticholinergics and inotropic drugs) within a short time after induction. All of these donkeys had very painful orthopedic conditions (i.e., were “three-legged” lame or had severe laminitis) which may not have been adequately treated with analgesics preoperatively due to a failure to recognize pain in donkeys.

Basic monitoring should be similar to the horse with some subtle differences seen in donkeys and mules. Eye signs (nystagmus, corneal and palpebral reflexes, and rotation of the eyeball) are helpful and similar, but not as reliable in the donkey. Monitoring blood pressure (either indirectly or directly) is strongly recommended; blood pressures will increase as the patient gets “light” and are a more reliable indicator of depth of anesthesia. When placing an arterial catheter, it is recommended to perforate the (thicker) skin with a needle prior to introducing the catheter; this will prevent “burring” the catheter. Branches of the facial artery, dorsal metatarsal, and auricular arteries are good sites for catheter placement to allow direct blood pressure measurement.

Hypotension (defined as a mean arterial pressure less than 70 mm of Hg) should be treated in the same manner as the horse; plane of anesthesia should be decreased if possible; IV fluids should be increased; and an inotrope (such as dobutamine) should be administered until appropriate blood pressure is restored.

Respiratory rate and pattern should be carefully observed; normal respiratory rates are faster in donkeys than in horses, but the author has observed breath-holding during a painful procedure in donkeys, rather than increasing respiratory rate as would be expected in horses. An increase in respiratory depth and spontaneous “sighing” are usually associated with a very light plane of anesthesia. Capnography is recommended for intubated patients and pulse oximetry or blood gases should be monitored to assess oxygenation.

Post anesthetic myositis is less likely to occur in donkeys since they have much smaller muscle mass, but could occur in mules, especially draft types. Appropriate padding of body surfaces and caution to pad exposed nerves (i.e., facial and radial) should be taken.

When the donkey is not intubated (as with injectable anesthetics), the anesthetist should be observant that airflow is not compromised by a head position such that the airway is kinked or that excessive nasal tissue obstructs airflow. Straightening the position of the head relative to the neck, or placement of a nasal cannula usually relieves excessive inspiratory noise. Supplemental oxygen should be provided if possible.

Since donkeys usually have a calmer manner, recovery from anesthesia is usually not affected by the hysteria which is often seen in horses. However, analgesia should be provided since pain affects the quality of recovery from anesthesia. Donkeys will generally lie quietly until they are able to stand; they may make a half-attempt to stand and lie back down if not coordinated enough. It is generally not necessary to “hand recover” a donkey; sometimes a boost on the tail is helpful (Figure 5). Donkeys will also frequently stand hind-end first (like a cow), or get up on one knee and hind legs first. Mules are more variable in their response to recovery and may require assistance with head and tail ropes (as would be used in horses).

Figure 5: It is generally not necessary to “hand recover” a donkey; sometimes a boost on the tail is helpful. Image courtesy of Drs. Nora Matthews and Jill K. Maney.As mentioned previously, although the analgesics used in horses are appropriate for donkeys and mules, the dose or dosing interval need to be adjusted, and the clinician must be more observant about the degree of pain shown by the animal. There is less published information for mules, so careful observation is recommended.

In conclusion, although it is tempting to treat donkeys and mules like little horses, there are significant differences in physiology, behavior and drug response which must be taken into account in order to provide successful and minimally stressful anesthesia.

• www.ivis.org. Matthews and Taylor. Veterinary care of donkeys.

• Matthews and van Loon, Anesthesia, sedation and pain management of donkeys and mules. P. 515-527. Veterinary clinics/equine practice. Diseases of donkeys and mules, ed. Toribio. Dec. 2019.

Dr. Nora Matthews has spent five years in mixed animal practice after graduating from veterinary school. She did her residency in anesthesia at Cornell, followed by being on faculty at Washington State, Oklahoma State and Texas A & M. As a clinician, she has spent more than 50% of her time in the hospital and on emergency duty. Her research interests include monitoring equipment and small animal and equine drug protocols. Dr. Matthews is currently semi-retired, serving as a locum at various universities and large referral clinics.

Dr. Maney received her BS from Pennsylvania State University and VMD from the University of Pennsylvania. She completed an anesthesia residency at the University of Georgia and became a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia in 2013. She currently serves as an Associate Professor of Anesthesiology at Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine. Her research interests include novel anesthetic agents, respiratory function during anesthesia, and anesthesia/analgesia in donkeys.

Horses make us better. Together, we make them better, too.Jill K. Maney, VMD, Dipl. ACVAA Nora Matthews, DVM, DACVAA (Diplomate American College Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia)

The Next Generation of FLU Protection

Introducing updated flu strains, only available in the Prestige vaccine line from Merck Animal Health

Developed to help protect against influenza viruses threatening horses today, the Prestige line of flu vaccines offers the most encompassing and advanced level of protection against equine influenza.

Horses deserve the best protection we can give them. Contact Merck Animal Health or your veterinarian to learn more about the new Prestige line of vaccines.

www.merck-animal-health-equine.com

Florida ‘13 Clade 1:

Based on a highly pathogenic isolate from the 2013 Ocala, Fla. influenza outbreak that impacted hundreds of horses. Florida ‘13 was exclusively identified and isolated through the Merck Animal Health Biosurveillance Program.

UPDATED INFLUENZA STRAINS INCLUDE: Richmond ‘07 Clade 2: Meets World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) guidelines for Clade 2 influenza protection.

IN ADDITION TO:

Kentucky ‘02: Influenza strain maintained from previous vaccine line.

For more than 30 years, Adequan® i.m. (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan) has been administered millions of times1 to treat degenerative joint disease, and with good reason. From day one, it’s been the only FDA-Approved equine PSGAG joint treatment available, and the only one proven to.2, 3

Reduce inflammation

Restore synovial joint lubrication

Repair joint cartilage

Reverse the disease cycle

When you start with it early and stay with it as needed, horses may enjoy greater mobility over a lifetime.2, 4, 5 Discover if Adequan is the right choice. Visit adequan.com/Ordering-Information to find a distributor and place an order today.

BRIEF SUMMARY: Prior to use please consult the product insert, a summary of which follows: CAUTION: Federal law restricts this drug to use by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. INDICATIONS: Adequan® i.m. is recommended for the intramuscular treatment of non-infectious degenerative and/or traumatic joint dysfunction and associated lameness of the carpal and hock joints in horses. CONTRAINDICATIONS: There are no known contraindications to the use of intramuscular Polysulfated Glycosaminoglycan. WARNINGS: Do not use in horses intended for human consumption. Not for use in humans. Keep this and all medications out of the reach of children. PRECAUTIONS: The safe use of Adequan® i.m. in horses used for breeding purposes, during pregnancy, or in lactating mares has not been evaluated. For customer care, or to obtain product information, visit www.adequan.com. To report an adverse event please contact American Regent, Inc. at 1-888-354-4857 or email pv@americanregent.com.

Please see Full Prescribing Information at www.adequan.com.

1 Data on file.

2 Adequan® i.m. Package Insert, Rev 1/19.

All trademarks are the property of American Regent, Inc. © 2021, American Regent, Inc.

3 Burba DJ, Collier MA, DeBault LE, Hanson-Painton O, Thompson HC, Holder CL: In vivo kinetic study on uptake and distribution of intramuscular tritium-labeled polysulfated glycosaminoglycan in equine body fluid compartments and articular cartilage in an osteochondral defect model. J Equine Vet Sci 1993; 13: 696-703. 4 Kim DY, Taylor HW, Moore RM, Paulsen DB, Cho DY. Articular chondrocyte apoptosis in equine osteoarthritis. The Veterinary Journal 2003; 166: 52-57. 5 McIlwraith CW, Frisbie DD, Kawcak CE, van Weeren PR. Joint Disease in the Horse.St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2016; 33-48.