HOW THE FVMA PLANS TO TACKLE TELEHEALTH LEGISLATION

DAVID E. FREEMAN MVB, PhD, DIPLOMATE ACVS

DAVID E. FREEMAN MVB, PhD, DIPLOMATE ACVS

DAVID E. FREEMAN MVB, PhD, DIPLOMATE ACVS

DAVID E. FREEMAN MVB, PhD, DIPLOMATE ACVS

RUTH-ANNE

What an incredible start to the year! Our 59th Ocala Equine Conference (OEC) was a fun and exciting success. Held at the World Equestrian Center (WEC) – Ocala, the world’s largest equestrian complex in the United States, it was an impressive venue with many benefits for our attendees. Our sold-out ultrasound wet lab, held at the Equine Medical Center of Ocala, was a highlight for participants who honed valuable skills they’ll be using on patients the next day. I know we’re all looking forward to returning to WEC next year for our 60th OEC – be sure to mark your calendars for Jan. 19-21, 2024!

ADAM

Missed out on OEC? Our flagship equine conference, Promoting Excellence Symposium (PES), will be held Oct. 19-22, 2023, in West Palm Beach, Fla., at the Hilton West Palm Beach. PES provides unique opportunities for learning, leisure, and networking for equine veterinary practitioners and industry professionals from near and far. Offering world-class continuing education, PES 2023 features world-renowned speakers, cutting-edge topics, and a wet lab that will provide comprehensive instruction and lead participants in hands-on learning. Want a pro tip? Our ever-popular wet lab sells out fast. Don't get stuck on the waiting list, register as soon as we launch! Learn more on page 17.

SALLY

I hope you’ll find this issue of The Practitioner to be another worthy read. I understand some of the articles differ from our usual subject material (equine medical/scientific articles), but it’s important for us to remember the bigger sphere in which our industry and profession operates. Legislative and personal challenges face us – but, together, I know we can handle them.

COREY

As we go into the busy spring season, I hope you will be kind to yourself and check in with those around you.

Kind regards,

Armon Blair, DVM Ocala Equine Hospital FAEP Council President abeqdoc@gmail.com

JACQUELINE

If anyone is struggling with mental wellness, please do not hesitate to reach out to colleagues, friends, or the FAEP (call 800.992.3862).

Our Membership Assistance Program (MAP), which is free for all members, offers personal and professional consultation to help you be your best. More information and wellness resources can be found at fvma.org

Opinions and statements expressed in The Practitioner reflect the views of the contributors and do not represent the official policy of the Florida Association of Equine Practitioners (FAEP) or the Florida Veterinary Medical Association (FVMA), unless so stated. Placement of an advertisement does not represent the FAEP’s or FVMA’s endorsement of the product or service.

The FAEP focuses on supporting the professional development of its members, providing a wealth of benefits focused on both personal and professional assistance in your daily life. Members get exclusive access to discounts, programs, and systems that assist with mental wellness, legal matters, educational opportunities, and more. That leaves more room in your life for doing what you love.

Members have access to online courses and conferences for affordable CE opportunities. Conferences expand the skills and knowledge of attendees while offering a chance to network with colleagues and industry partners. Our yearly equine events include Ocala Equine Conference (OEC) and Promoting Excellence Symposium (PES).

These conferences expand the skills and knowledge of attendees while offering a chance to network, professionally and socially, with colleagues and industry partners in the veterinary medical field.

The Florida Veterinary Medical Association’s (FVMA) Legislative Committee and our staff are constantly monitoring any proposed legislation that could affect small- and large-animal medicine. Our statewide member network contacts legislators whenever necessary to protect the interests of our membership. We retain the lobbying firm Converge Government Affairs to ensure that the “good bills pass” and the “bad bills don’t.”

Our members do so much to care for animals, and we’re just as driven to take care of our members. The Membership Assistance Program (MAP) is available 24/7/365 to offer help with personal and/or professional concerns by providing free, confidential, short-term counseling and personal consultation.

The MAP provides personal and financial consultations, but FAEP members have always been able to ask our legal team questions on practicing veterinary medicine, pharmacy law, and veterinary board relations.

We’ve expanded legal benefits to include new areas of law such as labor and employment law and civil litigation.

Practice and pharmacy-related inquiries are referred to attorney Edwin Bayo, partner of Grossman, Furlow, Bayo, LLC and instructor of the RACE-approved three-hour Florida Laws and Rules & Dispensing Legend Drugs course. Labor, employment law, and civil litigation inquiries are referred to Sniffen & Spellman, P.A.

To take advantage of this benefit, email info@fvma.org with your inquiry and contact information.

FVMA Advocate and The Practitioner are both published four times a year. These publications are provided to members free of cost and are vehicles for circulating up-to-date industry and medical information as well as information regarding CE conferences and events. Emails and social media will also keep you in the loop with breaking news and issues that affect your profession.

The FVMA/FAEP staff are here to help you and answer any questions you might have. Your business and professional interests are our daily focus. Staff are up to date on most DBPR/licensing issues/questions and can answer your questions Monday-Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. If we don’t know the answer, we’ll do our best to find it for you!

■ The Power of Ten

Th is program is designed to foster and support leadership potential in the industry by providing learning experiences to recent graduates that will engage and develop foundational skills in leadership, communication, and business.

■ Financial Resources

The FAEP offers resources to make managing the fi nancial side of your career easier, including:

• Receiving cashless payments using Clover Merchant Services, a Fiserv company

• CareCredit enrollment

• Poor debt avoidance and cash flow improvement

We are excited to offer these benefits to all FAEP members to enrich the lives of equine professionals everywhere. FAEP members maintain access to these benefits and new benefits as we continue to develop offerings.

■ Digital Marketing

Social Ordeals can help veterinary practices with digital advertising, social media management, reputation management, and listing management so you and your staff can focus on taking care of patients. They help practices improve their online visibility in local searches with a powerful platform that manages listings, reviews, and social marketing.

Members can get a free custom report card on their online presence and exclusive discounts by visiting socialordeals.com/fvma/.

■ Exclusive Discounts

You can get discounts on everything from event tickets to rental cars, movie tickets, streaming services, and more. We’ve partnered with Working Advantage to offer you a one-stop shop for savings on the experiences, products, and services you know and love.

Visit workingadvantage.com to enroll. Click “Become a Member” and use code FVMAPERKS to create your account.

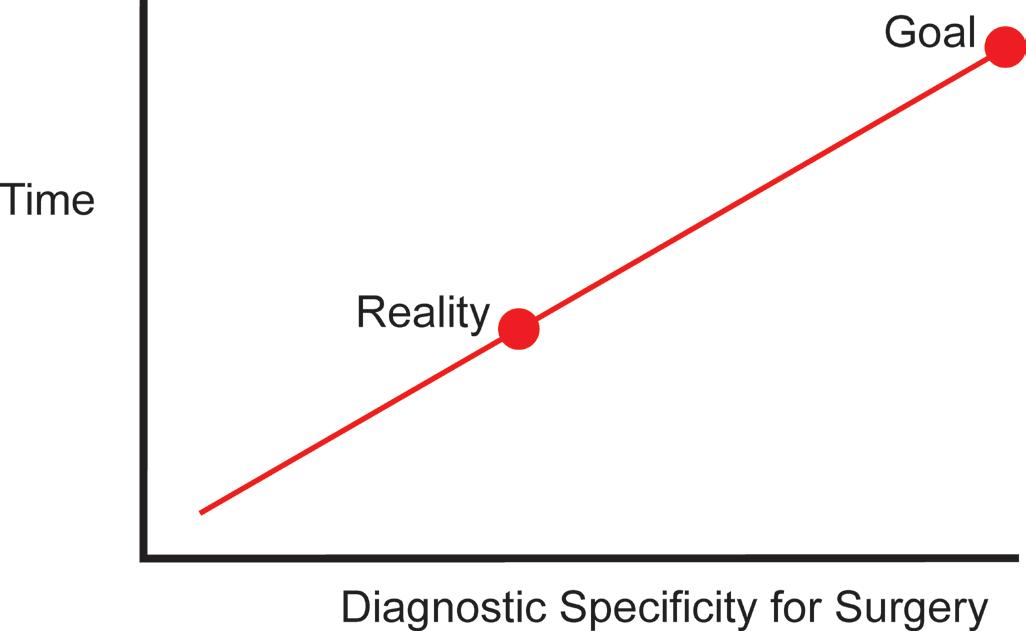

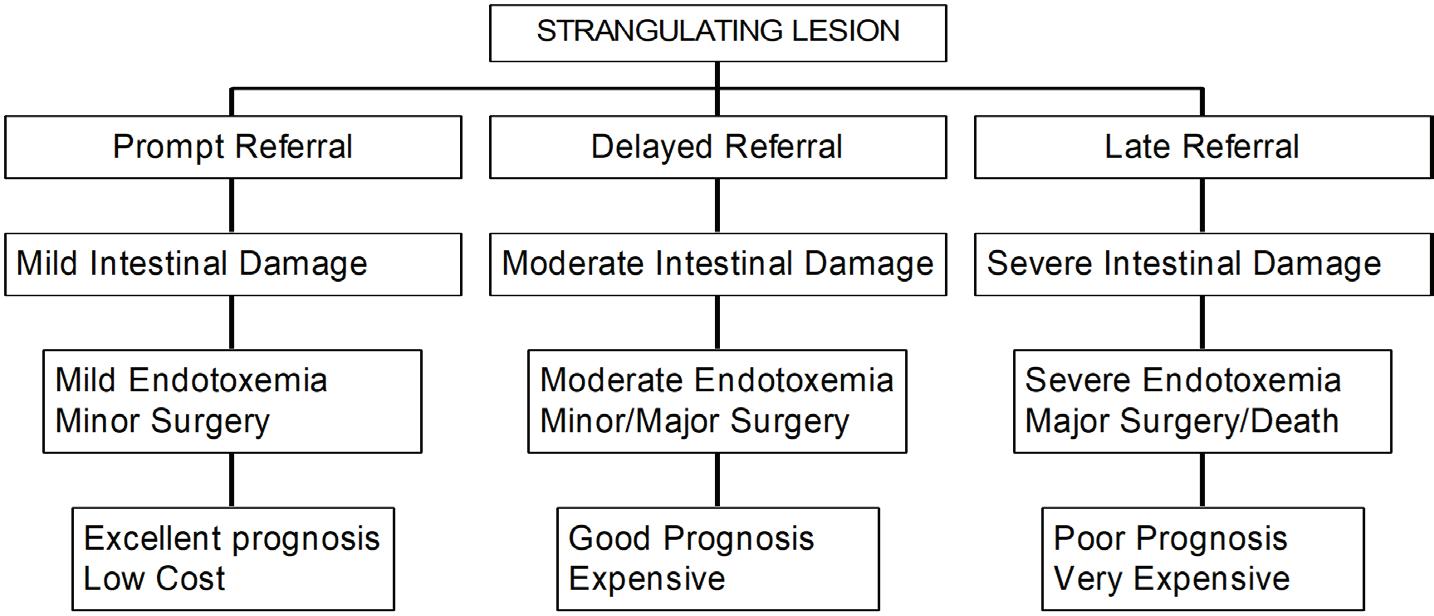

Despite positive trends in colic surgery over the past 50 years, owners, referring veterinarians, and hospital-based surgeons are repeatedly reminded that the single most important factor impacting patient outcome is prompt referral to a fully staffed and equipped surgical facility. Sadly, in recent years, the referral process seems to have shifted towards a delay in surgical treatment. Many factors could be responsible for this change, but owner issues, such as concerns about cost and misconceptions about the disease and its treatment, stand out. It is also time to refi ne the concept of early referral as sending a horse to a surgeon when available evidence tips the scale toward

surgery, even when more solid proof is lacking (Figure 1), is often key to a successful outcome. Failure to do this leads to higher treatment costs, poor results, and a decline in confidence in colic surgery (Figure 2).

The main benefits of early referral are reduced severity of intestinal injury and the associated endotoxemia/systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) at hospital admission1 (Figure 2). A much-overlooked benefit is reduced complication rates. Th is improves survival rates, lowers costs, increases owner satisfaction, and improves overall confidence in colic surgery. Many diagnostic procedures have emerged over the years that can be used to improve the referral process. However, these should be used with careful selectivity and not to improve the specificity of the assessment process, especially if other criteria support the decision to refer (Figure 1).

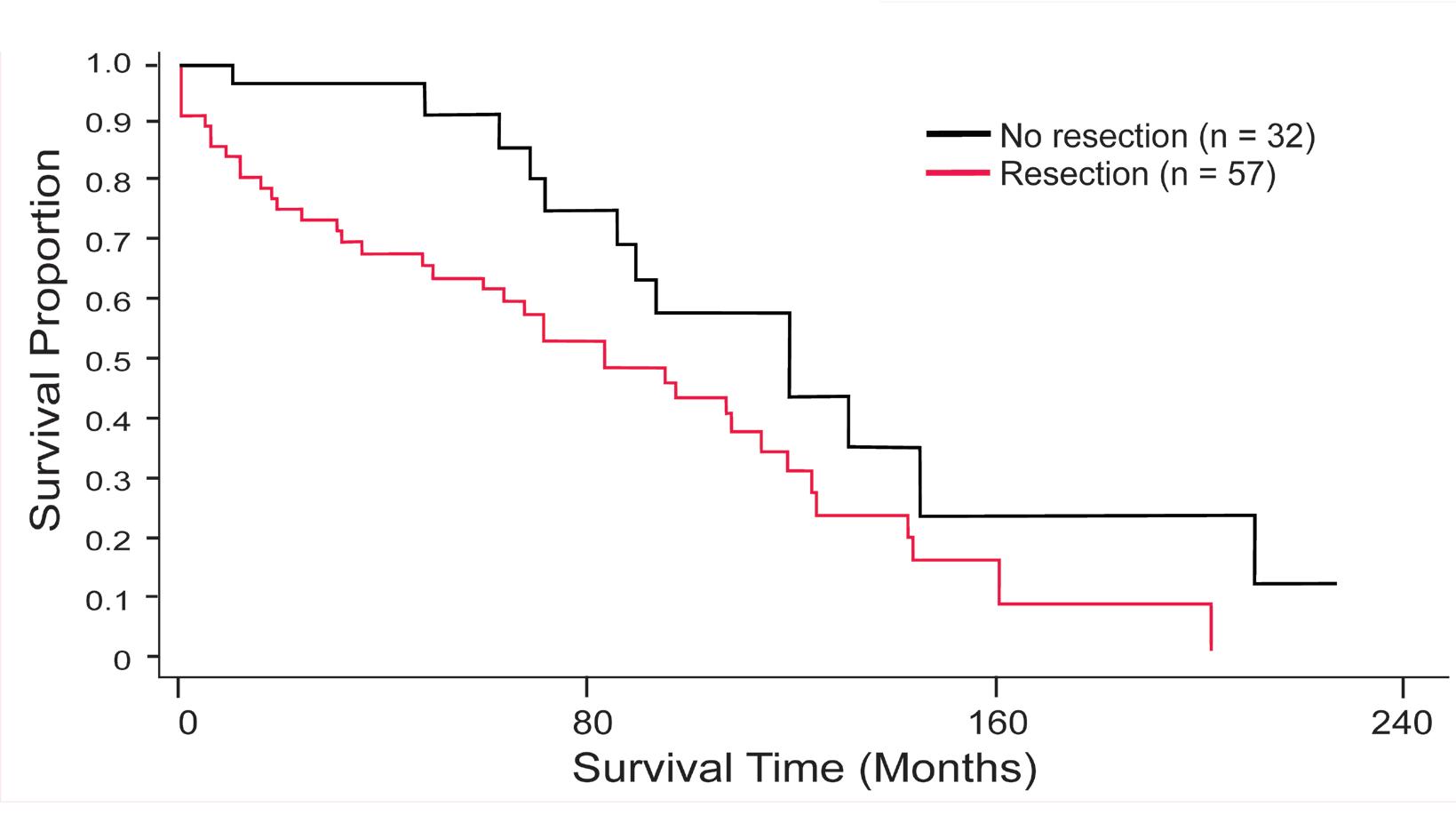

In a recent study on horses that had surgery for small intestinal strangulation, those that did not require resection (Figure 3) had superior long-term survival rates compared to those that required resection 2 (Figure 4). In that study, all the horses that did not require resection survived until hospital discharge and experienced low complication rates. The median survival time for the group that did not require resection (when half the horses were still alive) was three years longer than the group requiring resection (120 months versus 84 months). Th is difference is significant. More importantly, those that did not need a resection (Figure 4) had a significantly shorter duration of colic

before surgery than those that did need resection, evidence that referral before irreversible changes develop in the strangulated small intestine is a key element to improving survival after colic surgery.3 Early referral has been shown to improve survival after large colon volvulus (LCV),4,5 ileal impaction, 6 inguinal hernia,7,8 and entrapment in the epiploic foramen (EFE).9 The risk of postoperative ileus and diarrhea after surgery can also be reduced by early referral.10

The argument for early referral is strengthened by the observation that the length of small intestine strangled can increase over time as more is drawn in until the ileum becomes involved.11 (Figure 5). Th is can then lead to a more complicated

surgery with a poorer prognosis. Delays in referral can also increase distention in the intestine oral to the lesion,12 which leads to poor perfusion of that segment and adhesions (Figure 5). Prolonged periods of pain can lead to self-infl icted traumatic injuries (Figure 6), and such fi ndings could indicate a longer disease course preceding the time of discovery (Figure 6).

The owner’s decision regarding colic surgery is a complex part of the referral process,13 largely frustrated by the nature of the disease, limited opportunity for preparation, the immediate need for resources that are not always available — such as a trailer for transport or funds — and limited opportunity to seek input from friends and family. If the owner states that surgery is not an option, the groundwork for failure has been laid in many cases. The problem is that a change of heart can follow when the need for surgery becomes established later, at which point the prospects of a successful outcome have passed, considerable expense has been incurred, and a resection that could have been avoided earlier is needed. Therefore, the referring veterinarian must have a frank and informed discussion with the owner about his or her aversion to colic surgery. Many owners might be seeking arguments against surgery at this stage, such as cost, poor outcomes, and other negative issues. They are likely grasping at the hope that surgery is not indicated.

The following are commonly used explanations from owners for rejecting surgery, which need to be addressed:

• Colic surgery is rarely successful.

Colic surgery has a success rate of approximately 80% survival for horses with small intestinal strangulation.

• The owner might prefer to try medical treatment first. Medical treatment is not a substitute for surgical treatment if the horse has a strangulating lesion, and prolonging suffering is inhumane.

• A fr iend’s horse died from colic surgery, and he/she was devastated by the poor outcome. Th is experience reflects a strong emotional impact, but it is based on a single case and each case is different.

• The horse will never be the same after colic surgery. Most horses return to previous use, even in athletic

competition at the highest level, such as winning major stakes races. A prime example is Lil E. Tee, an Americanbred Thoroughbred horse that won the Kentucky Derby in 1992).

• This mare is pregnant, and it will be impossible to save the mare and foal with surgery. Mares can foal normally and deliver a live foal at any time after colic surgery, provided the surgery is done promptly.

• This is an old horse, and old horses do not handle anesthesia and colic surgery well. This is simply untrue (see the section on strangulating lipoma on page 9).

• This horse is much loved/valued, but we cannot justify spending money on colic surgery in our present financial circumstances.

This is probably the most valid concern for some owners, but should be based on recognition of two critical factors: 1) if surgery is needed, the sooner it is done, the lower the cost, and 2) the attending veterinarian can seek help from a surgeon that could be consulted on the case for accurate estimates.

The cost of colic surgery can play a large role in an owner’s decision14 and could explain the growing rates of euthanasia, especially before and during surgery.15 Referring veterinarians can guide them on this.16 However, owner attitudes toward surgery can undergo a complete reversal from staunch refusal

to full acceptance at all costs when the owner eventually realizes that surgery is the only option.

If the owner declines referral, the attending veterinarian must establish clear guidelines for the next step. At this point, the owner must be informed that if the horse has a true surgical lesion, especially small intestinal strangulation, only surgery will save its life. If a surgical diagnosis cannot be made definitively and if the horse “appears comfortable,” the owner might request continued medical treatment, “just in case.”

This approach should prompt the following questions for the owner:

• Is this a humane approach?

• What is my true financial limit on this horse?

• Can I afford repeated visits to the farm for treatments?

• How much time can I commit to around-the-clock monitoring and care?

• Can I handle watching my horse suffer?

• Is my family supportive of this decision?

• Will I change my mind or stay the course?

The last question is critical, because if the owner requests surgery at a later period, it is probably too late. Resources have been exhausted and euthanasia may be the only reasonable option. At that point, the cost of surgery will be considerable, and the outcome for the patient is poor (Figure 7). Referral to a hospital for a second opinion and supportive care is another option and could confirm that humane euthanasia is needed.

Horses that require surgery or euthanasia because of a surgical lesion can have one or more of the following: persistent pain despite analgesic drugs, a persistently elevated or increasing heart rate (≥ 48 beats/minute), reflux from a nasogastric tube, worsening abdominal distention, abnormal rectal examination

fi ndings, obvious abnormality on ultrasound examination, and belonging to a high-risk group (see below). However, pain indicators in some horses might be absent or subtle, such as nostril tension and flare, facial grimace, and abrasions on boney prominences. The diagnostic approach should be realistic and recognize that a high degree of diagnostic sensitivity is preferred to seeking a high degree of diagnostic specificity17 (Figure 1). High sensitivity means that many horses that could be treated at home will be referred, which is better than the aggressive pursuit of diagnostic accuracy that could delay referral for horses with surgical lesions. Th is is the error that leads to the worst patient outcomes.

Simple features in the signalment can provide diagnostic clues for different surgical lesions (Table 1). If other fi ndings fit with the possible “at risk” diagnosis, as with lipoma (see below), the odds of that disease being responsible for colic increase accordingly. Th is should prompt an early decision toward surgery. However, as with any diagnostic procedure, it is important not to fi xate on any particular diagnosis.

Old horses (horses ≥ 10 years) have similar types of colic as younger mature horses, but they also have their own more lethal and common disease: strangulating lipoma.18 Th is age/

HORSE FACTOR(S)

Horse >10 years old (especially >15)

Intact male (especially Standardbreds)

Miniature horse, small pony, foal of any breed

Mare in late pregnancy

Previous small intestinal surgery

Postpartum mare with severe abdominal pain

Postpartum mare with mild colic, peritonitis

Feeding coastal Bermuda grass hay

Cribber (especially a Thoroughbred and gelding)

disease link is so well established as a horse ages18 that an old horse with colic should be considered as having a strangulating lipoma until proven otherwise.

Unfortunately, these horses are the most likely victims of delayed decisions about surgery. They are already at the end of their lifespan and many of them have comorbidities, like lameness, pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction, and laminitis, that might tip the decision against surgery. Many have earned a strong degree of emotional worth but have passed their prime for their intended purpose. Th is is the group that presents the greatest fi nancial challenge to owners. If distended loops of small intestine are found on rectal examination or on ultrasound examination with abrasions on bony prominences

AT RISK FOR:

Strangulating lipoma

Inguinal hernia

Fecalith in small colon

Uterine torsion

Recurrent disease or adhesions

Large colon volvulus, other strangulation

Small colon avulsion/necrosis, ruptured uterus

Ileal impaction

Epiploic foramen entrapment

(Figure 6), with or without reflux through a nasogastric tube, surgery is probably required as soon as possible.

Old horses are likely to be denied surgery because of the myth that they cannot handle anesthesia and surgery well.19 Old horses can be stoic,19 which can be a breed effect, as commonly seen in Tennessee Walking Horses, but all horses with a strangulating lesion can also become obtunded by endotoxemia. Th is can lead to an impression of a mild or resolving disease. As with all horses with small intestinal strangulation, these horses also develop a vacuum-packed large colon, which can feel like a dry, hard impaction on palpation per rectum. Th is creates the erroneous impression that they have a large colon impaction, a nonsurgical disease. A rectal fi nding of colon impaction is actually a strong indicator that small intestinal strangulation is the primary lesion.

Peritoneal fluid changes, such as serosanguinous discoloration and elevated peritoneal lactate, develop early in the course of intestinal ischemia. 20 Although easy to perform, abdominocentesis performed at home delays referral and increases cost with little gain. Abdominocentesis can also be difficult to interpret, and equivocal fi ndings are common. These fi ndings should not be interpreted in isolation. Abdominocentesis might have a place in a patient’s treatment plan if the owner needs strong guidance on a decision for euthanasia. The following limitations should be considered before using this test:

• Gross appearance, PCV, and TP in the peritoneal fluid can be misleading or equivocal and time for laboratory analyses can delay decision-making (Figure 8).

• The following surgical lesions might not develop diagnostic peritoneal fluid changes:

· Large colon volvulus, even with a nonviable colon

· Diaphragmatic hernia (strangulated segment in the thorax)

· Ruptured viscus, which can produce fluid with a normal gross appearance, WBC, and TP (need a cytological examination)21

Early pressure necrosis in the site of an enterolith, fecalith, or foreign body impaction

· Lipoma strangulation by the wrapping of the lipoma around a segment of intestine rather than strangulating a loop and its vasculature

The misconception has emerged over recent years that fluid therapy on the farm for horses with strangulating diseases can make them better candidates for surgery and anesthesia. The ready availability of sterile fluids in plastic bags and associated systems for delivery make this treatment very feasible and attractive (Figure 9). However, the benefits of this approach before referral are highly questionable, even for strangulating lesions, and the delays, complications, and costs associated with it are difficult to justify. Similar concerns apply to continuous rate infusions (CRIs) on the farm (e.g. lidocaine). Instituting IV fluids immediately before surgery is sufficient in most cases because defi nitive treatment (surgery) follows. Risks of overly aggressive fluid therapy before referral are:

• High-volume fluid therapy can produce a misleading degree of improvement that only confuses owners and delays referral.

• High-volume fluid therapy can create electrolyte imbalances such as calcium and magnesium losses through sodium diuresis. 22 Some of these changes can delay postoperative recovery and reduce survival.

• The time required for administration of fluids and to monitor responses allows for the worsening of tissue injury (Figure 2). Consequently, the ischemic changes can become irreversible and the more proximal distended segments will probably fill with much of the fluid-infused IV (Figure 5). This only adds to proximal intestinal distention and mural edema, critical factors that increase pain and delay recovery. 23

• There is a growing awareness that aggressive fluid therapy can cause adverse consequences for recovery of intestinal function. This can be mediated through damage to the vascular endothelium that exacerbates transcapillary fluid leakage and tissue edema. 24

• In a clinical study in horses with small intestinal strangulation, a more restricted goal-directed approach to fluid therapy had similar survival and complication rates as the traditional liberal fluid therapy. 25

Repeating the same diagnostic and treatment procedures at a surgery facility that were performed at the farm can become a contentious issue with many owners, and referring veterinarians should consider this. Owners regard this as an unnecessary additional cost, arguing that their veterinarian already did the same. Unfortunately, some information might be missing or some indicators could have changed during the interim. Warning owners of this beforehand might prepare them to accept this necessity. If hospital tests are regarded as necessary in the field situation, then the horse should be referred instead so that the procedure can be performed in the same hospital that will conduct the surgery.

Decision-making about colic referral is complicated for owners,13 and therefore a team approach is recommended, that starts with the owner or designee and the referring veterinarian. If clinical signs suggest surgical treatment is indicated, but owner reluctance persists, a surgeon at the hospital that would receive the case should be consulted to provide a reasonable overview of cost and prognosis. The decision that surgery is or is not an option should be based on solid facts that could be produced by discussion with all involved. The goal is not to

change the owner’s mind but to prevent a fatal change of course that closes off the opportunity for a successful surgery.

The referral process can be summarized as the need to pursue a second opinion for a horse that does not fit within the typical colic presentation that will respond to medical treatment at home. The owner should be guided by accurate information as to the true range of costs for the suspected disease and based on consultation with a surgeon at the hospital. This is intended to prevent those problem situations in which the surgery option is rejected initially, only to be selected later when the nonsurgical approach is failing. Owner education is critical, and all veterinary professionals play a role in that duty. This approach is based on a refined concept of early referral, which is sending a horse to a surgeon in a timeframe from disease onset that produces the best outcome at the lowest total cost (Figure 2).

1. Proudman CJ, Dugdale AHA, Senior JM, Edwards GB, Smith JE, Leuwer ML, French NP. Pre-operative and anaesthesia-related risk factors for mortality in equine colic cases. Vet J 2006;171:89-97.

2. Rudnick MJ, Denagamage TN, Freeman DE. Effects of age, disease and anastomosis on short- and long-term survival after surgical correction of small intestinal strangulating diseases in 89 horses. Equine Vet J. 2022 Jan 12. doi: 10.1111/ evj.13558. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35023209.

3. Freeman DE, Hammock P, Baker GJ, Foreman JH, Schaeffer DJ, Richter RA, Inoue O, Magid JH. Short- and long-term survival and prevalence of postoperative ileus after small intestinal surgery in the horse. Equine Vet J Suppl. 2000;32:42-51.

4. Levi O, Affolter VK, Benak J, Kass PH, Le Jeune SS. Use of pelvic flexure biopsy scores to predict short-term survival after large colon volvulus. Vet Surg 2012;41:582-588.

5. Hackett ES, Embertson RM, Hopper SA, Woodie JB, Ruggles AJ Duration of disease influences survival to discharge of Thoroughbred mares with surgically treated large colon volvulus. Equine Vet J 2015;47:650-654.

6. Parks AH, Doran RE, White NA, et al. Ileal impaction in the horse: 75 cases. Cornell Vet 1989;79:83-91.

7. Baranková K, M. de Bont MP, Simon O, Meulyzer M, Boussauw B, Vandenberghe F and Wilderjans H. Nonsurgical manual reduction of indirect inguinal hernias in 89 adult stallions. Equine Vet Educ 2021; https://doi: 10.1111/ eve.13494.

8. François I, Lepage O, Boswell J, Schofield W, Perez

Olmos JF, Grulke S. Acquired inguinal herniation in horses: a retrospective multicenter study of 48 cases. Vet Surg. 2014;43:E167.

9. Scheidemann W. Beitrag zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Kolik des Pferdes: Die Hernia Foraminis omentalis. 1989; DMV thesis, Muenchen.

10. Fogle CA, Gerard MP, Correa M and Blikslager AT. An analysis of factors associated with a prolonged duration of colic (344 horses). Proc. 10th Equine Colic Res. Symp. 2011;10, 202.

11. Gandini M. and Giusto G. Why is the ileum involved in the majority of cases of internal hernias? a biomechanical hypothesis. Equine Vet Educ 2021;33. Supplement 12:48.

12. Dabareiner RM, Sullins KE, Snyder JR, White NA 2nd, Gardner IA. Evaluation of the microcirculation of the equine small intestine after intraluminal distention and subsequent decompression. Am J Vet Res. 1993;54:1673-1682.

13. Scantlebury CE, Perkins E, Pinchbeck GL, et al. Could it be colic? Horse-owner decision making and practices in response to equine colic. BMC Vet Res 2014; doi: 10.1186/1746-614810-S1-S1.

14. Archer DC. Colic surgery: keeping it affordable for horse owners. Vet Rec. 2019;185505-507.

15. Blikslager AT, Mair TS. Trends in the management of horses referred for evaluation of colic: 2004–2017. Equine Vet Educ 2021;33:192-197.

16. Ireland JL, Clegg PD, McGowan CM, et al. Factors associated with mortality of geriatric horses in the United Kingdom. Prev Vet Med 2011;101:204– 218.

17. Peloso JG, Cohen ND, Taylor TS, Gayle JM. When to send a horse with signs of colic: is it surgical, or is it referable? A survey of the opinions of 117 equine veterinary specialists. Proc Am Assoc Eq Pract 1996;42:250-253.

18. Freeman DE, Schaeffer DJ. Age distribution of horses with strangulation of the small intestine by a lipoma or in the epiploic foramen: 46 cases (1994-2000). JAVMA 2001;219:87-89.

19. Southwood LL, Gassert T, Lindborg S. Colic in geriatric compared to mature nongeriatric horses. Part 2: Treatment, diagnosis and short-term survival. Eq Vet J 2010;42:628-635.

20. Ruggles AJ, Freeman DE, Acland HM, et al. Changes in fluid composition on the serosal surface of jejunum and small colon subjected to venous strangulation obstruction in ponies. Am J Vet Res 1993;54:333-340.

21. Pratt SM, Hassel DM, Drake C, Snyder JR. Clinical characteristics of horses with gastrointestinal ruptures revealed during initial diagnostic evaluation: 149 cases (1990-

2002). Proc Am Assoc Eq Pract 2003;42:254-255.

22. Garcia-Lopez JM, Provost PJ, Rush JE, Zicker SC, Burmaster H, Freeman LM. Prevalence and prognostic importance of hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia in horses that have colic surgery. Am J Vet Res 2001;62:7-12.

23. Shah SK, Uray KS, Stewart RH, Laine GA, Cox CS Jr. Resuscitation-induced intestinal edema and related dysfunction: State of the science. J Surg Res 2011;166:120130.

24.Woodcock TE, Woodcock TM. Revised Starling equation and the glycocalyx model of transvascular fluid exchange: an improved paradigm for prescribing intravenous fluid therapy. Br J Anaesth 2012;108:384-394.

25. Giusto G, Vercelli C, Gandini M. Comparison of liberal and goal-directed fluid therapy after small intestinal surgery for strangulating lesions in horses. Vet Rec. 2021 Feb;188(3):e5. doi: 10.1002/vetr.5. PMID: 34651880.

David E. Freeman, MVB, PhD, Diplomate ACVS

David Freeman graduated from the Veterinary College of Ireland, Dublin, in 1972 and was awarded a PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1985. From 1981 to 1994, he was an equine surgeon at New Bolton Center and became a board-certified surgeon in the American College of Veterinary Surgeons in 1989. He joined the faculty at the University of Illinois, College of Veterinary Medicine in 1994 and became the head of equine medicine and surgery in 1998. In 2004, he joined the department of large animal clinical sciences at the University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, as a professor of equine surgery and associate chief of staff, and subsequently served as the service chief in large animal surgery. He was also the interim department chair in large animal clinical sciences at the University of Florida from 2009 to 2012.

ratio, every wet lab attendee received personalized instruction. Attendees earned eight CE hours while rotating through five anatomical stations as they worked with real horses under the

SPONSORS:

supervision of expert educators. Th is year’s wet lab introduced the eye station, where Brittany Martabano, DVM, MS, DACVO, showcased how smartphones could aid complex medical imaging. Additional stations covered the metacarpal, abdomen and thorax, back and pelvis, and the hock.

Our lecture-based CE sessions on Saturday and Sunday provided attendees with the opportunity to earn 16 CE hours from nine renowned speakers. Speakers shared their insights on lameness, respiratory health, internal medicine, ophthalmology, reproduction, professional wellness, and more using knowledge crafted from their careers’ worth of experience in equine medicine.

As the largest equestrian sports facility in the United States, WEC’s climate-controlled indoor amenities gave us the opportunity to present our educators on a grander stage than ever before. WEC’s size also provided fast, easy access to our exhibit hall, where attendees could connect one-on-one with industry representatives, play carnival-style games, and win prizes for participating in networking activities. Our exhibit hall at WEC was larger and more advanced than any previous iteration, with a jumbotron and video screens framing a fun, innovative space meant for mingling with our industry’s best.

Each day's educational sessions were followed by lively, interactive social events, including a welcome reception on Saturday and a bingo raffle on Sunday. Comradery has been an essential part of the FAEP’s events since their inception, and we’re proud to have been able to bring together one of our largest groups of equine practitioners yet. Th rough the opportunities afforded by our venues, we instilled an atmosphere of conversation and collaboration.

We’re excited to bring the same energy and quality of education to our next event, the Promoting Excellence Symposium (PES), in West Palm Beach on Oct. 19-22, 2023.

Veterinary telehealth legislation has been voted upon in Florida in recent years, and we are preparing for it to reappear. As leading animal advocates in the state, we want to do our part to protect animals as much as our dedicated veterinary professionals do.

The FVMA has long supported veterinary telehealth legislature that provides protections for the veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR). We are committed to nurturing opportunities that properly protect animals, their owners, and the veterinarians who support them.

Telehealth is a term used loosely in the discussion of veterinary care in the state of Florida as well as the entire United States. The term describes a large umbrella of healthcare modalities tied together by the use of an electronic device for communication between the care provider and the client/patient.

Discussions often center on a veterinarian or staff member’s ability to interact with a pet owner about general care, which can lend themselves well to virtual communication. Th is type of interaction is labeled teleadvice, and it is limited to providing information, opinions, or guidance that is not specific to a patient’s health.

Veterinary professionals often receive calls from animal owners during an emergency seeking immediate advice as to what to do next. Th is can lead to some quick recommendations such as how to temporarily bandage a wound, manage the ingestion of a toxic substance, or use an over-the-counter antihistamine and

is usually followed by directions to go to the closest veterinary care facility for proper treatment. Th is type of interaction is labeled teletriage. Similar to teleadvice, a diagnosis is not rendered during teletriage as this type of interaction is focused on helping animal owners make safe decisions in uncertain situations.

Neither of these, teleadvise or teletriage, require an established VCPR to perform.

Only a small slice of the area under the veterinary telehealth umbrella is occupied by actual veterinary telemedicine, defi ned as the act of a Florida-licensed veterinarian diagnosing and subsequently prescribing legend drugs (commonly known as prescription drugs) or controlled substances strictly by telecommunications or audio/visual means.

It is our fi rm position that this diagnosing and prescribing

TELEMEDICINE the act of exchanging medical information electronically to improve a patient’s clinical health status. Examples of this type of telecommunication include electronically observing a patient for a postoperative follow-up examination, diagnosing a condition, recommending a particular treatment, or prescribing legend drugs or controlled substances.

TELEMONITORING involves remote monitoring of patients who are not at the same location as the veterinary professional. This type of telecommunication relies on the use of digital monitoring devices that capture a patient's vital signs and other behavior and transmit the important data back to veterinary professionals. This can guide recommendations and treatment.

must only occur, for the direct benefit of the animal, within an established veterinary/client/patient relationship (VCPR). Th is VCPR, initiated by the physical exam of an individual animal or a site visit for herd health, gives the treating veterinarian some familiarity with the pet’s true baseline condition and allows for accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. It also allows the veterinarian to determine the agricultural site’s upkeep and operation, and the owner or site operator's abilities to properly complete the recommended treatments. Under current Florida veterinary rules and Federal Veterinary Directives, this must occur at least once a year.

TELEADVICE involves using electronic communication devices to provide general health information, opinions, guidance, or recommendations that are not specific to a patient's unique health status. This type of information is not intended to diagnose or treat patients but instead refers to generic advice such as recommending that all animals should receive annual wellness exams or providing general advice on how to encourage pets to exercise.

TELETRIAGE refers to the safe, appropriate, and timely assessment and management of patients via electronic communication during conditions of uncertainty and urgency. This can lead to some quick recommendations such as how to temporarily bandage a wound or manage the ingestion of a toxic substance. A veterinary professional also determines the urgency of the situation and the need for immediate referral based on the client’s report of history and clinical signs.

Collaboration rests at the heart of our legislative efforts – with our membership in the Telehealth Coalition key. Spearheaded by the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), the coalition intends to collaborate across the veterinary and animal health industry to enhance and expand care by leveraging technology while safeguarding the welfare of animals and people.

The coalition's members are essential in helping better position veterinary practices to tackle telemedicine and are an essential part of protecting the VCPR.

As members of the Telehealth Coalition, we believe veterinary telehealth and, in particular, telemedicine holds great promise for improving continuity of care and strengthening the relationship between veterinarians, their clients, and their patients. We also support the recommendation of the AVMA that a VCPR should not be established via electronic means.

We are attempting to introduce our own version of the past years’ telehealth bill, as previous attempts at the legislation have failed to include proper VCPR protections.

In the draft version of our bill, research and conversations with all affected parties has led to proposed legislation we believe can serve as equal protection for pets, owners, and veterinarians alike.

Our work in fulfi lling our mission through legislative advocacy doesn’t end with any singular bill. While our focus is currently on telehealth and protecting VCPR, our defense of veterinary medicine never ceases. That is why we created the FVMA Advocacy Ambassador program, which provides participants with opportunities like meeting with legislators, visiting with district representatives to discuss legislative topics, virtual legislative strategy meetings, and exclusive communication on FVMA legislative maneuvers.

The FVMA Political Action Committee (PAC) is an essential defender of veterinary medicine in Florida. A bipartisan, nonprofit, political committee formed to raise contributions from our members, its fi nancial health is essential to our ability to be able to support animals through lobbying efforts.

When it comes time for Florida’s legislative session each year, the FVMA works tirelessly to ensure veterinary interests are considered as thousands of bills are introduced. We ask you to consider supporting the FVMA PAC.

This article references material published in the FVMA white paper, "What is Veterinary Telemedicine?" (2022), written by Dr. Richard Sutliff.

Horses make us better. Together, we make them better, too.

Katherine Pearce | Senior Creative Lead Florida Veterinary Medical Association

Katherine Pearce | Senior Creative Lead Florida Veterinary Medical Association

Our time is largely seen as being broken into two parts: work and life. Yet sometimes it’s not always easy to see a clear distinction. Work is often not seen as a part of life, though many initially pursue a career in the veterinary profession because they feel that if they love what they do, it won’t feel like work.

Unfortunately, the opposite immediately becomes true as 60+-hour work weeks quickly become the norm – especially for recent graduates. Weekends, birthdays, and holidays disappear into a rabbit hole of animal emergencies and nonstop obligations to clients and patients. A topic of increased interest within the profession has been work-life balance and helping veterinary professionals find that balance.

When fi nally getting home, you may feel too tired and stressed to be present. When you’re at work, you feel guilty for not being home. If you go home, you feel guilty for not tending to work. Those in the veterinary profession often feel they must give to others and share the pain of their patients and clients. Th is tendency burns veterinary professionals at both ends and selfcare disappears.

If no help is sought out, this may escalate into a loss of self-worth, isolation, loss of morale, detachment, an increase in emotional intensity (having reactions that are stronger than warranted), and even existential despair. Little sleep, poor eating habits, and, sometimes, a reliance on drugs and alcohol becomes the norm. Veterinary professionals stop playing with pets and start to dread their clients — these are serious signs that work has become too much.

“I distinctly remember our neurology professor, Dr. Cheryl Chrisman, tell us to make sure we had balance in our professional lives,” Dr. Philip Richmond, professional wellness committee chair of the Florida Veterinary Medical Association (FVMA), says. “Th is was hard for me to comprehend at the time. I mean, I’ve got student loans to pay and have been eating ramen noodles and hard-boiled eggs for the past four years. Plus, isn’t this everything I ever wanted — to be a veterinarian? ‘It’s time to get to work,’ I thought. Well I did, and I took on more than I could handle. I almost didn’t make it.”

According to a 2018 study reported by the AVMA, one in 20 veterinarians experience serious psychological distress with those 45 years and younger being more at-risk. The most frequent conditions reported were depression (98%), burnout (88%), and anxiety (83%). Th is imbalance of work and life can result in severe mental health complications that are exacerbated by perfectionist qualities commonly seen by those who enter the veterinary field. Th is can lead to imposter syndrome and a further chipping away at self-confidence. Those in the veterinary profession often feel selfish for taking time for themselves, but work-life balance is necessary to continue and excel in the profession.

It may seem simple, but “I have prior obligations” or “Sorry, I’m not available then” are both great ways to start saying no without giving more information than necessary. Even if the obligation is only to yourself, start making your personal life a priority. If you’re struggling to say “no,” ask yourself why you should say “yes.”

If it seems impossible to say no, consider having an open and honest discussion with clients about your medical abilities and their expectations, as this type of communication can help reduce the risk of compassion fatigue. Try to remember that saying no, whether regarding personal or professional pressures, will help you say yes for years to come.

A particular struggle is faced by solo equine practitioners, specifically those just starting out who are looking to build and retain a valuable client base. Solo practitioners are often in rural areas where it can be difficult to earn the trust and loyalty of local equine owners. Th is is no small challenge, and at times it may be difficult to tell what benefits you more in the long term. For instance, if your client calls on a holiday with a severely injured or dying horse, what will you do?

There appears to be two options:

Say yes.

You leave your family and drive out there. You spend that time with a distraught, and potentially grieving, owner. Th is may win you the client. It will ensure the horse gets help. While there, in an already emotionally fraught situation, you will likely feel compounding guilt and frustration for leaving your loved ones.

Say no.

You will feel guilty about not racing to your client and the potential additional time that the equine will be in distress. You will fear that you may lose the client, their revenue, and your reputation.

This is the impossible choice so many equine practitioners face. It will rarely be avoided entirely, and each veterinarian will have to make their own call based on the unique circumstances of each event. However, some things can be put in place to curb the number of times this occurs. Turning off your phone before events or having separate personal and work phones can stop these situations from coming to your immediate attention. Ensuring you have set up a voicemail directing callers to another practitioner, university, or a relief veterinarian will help distribute

the burden. Many practitioners are afraid that referring clients to another veterinarian may mean they lose their client, but that’s rarely the case when a good client relationship has been established. As mentioned above, preparing clients for these situations by having an open and honest discussion with clients about your abilities and their expectations can go a long way.

It’s important to take time off without feeling guilty about it. It may seem like it’s all about working hard, coming in early, and leaving late – but it is also about ensuring that you will be able to work in a healthy, happy manner where the overall feeling is enthusiastic and motivated. Th is will allow for the longevity of a personally fulfi lling career, which often goes hand-in-hand with fi nancial growth and stability as it ensures the practitioner continues in the profession and is mentally focused and energized, leading to better client interactions and accurate diagnoses.

“My experience forced me to fi nd balance,” Dr. Richmond says. “One way to defi ne ‘balance’ is having well-being in these five aspects of our lives: career, which includes challenging ourselves and partaking in lifelong learning; social, which includes having strong and healthy relationships; fi nancial; physical,

which includes incorporating nutrition, sleep, and exercise into your routine; and community, which reminds us to remember to engage with the people and area where we live. When we can make progress in all these areas, balance is the end result.”

Being a veterinarian is a profession – it’s what you do rather than who you are. Though it may seem impossible at fi rst, delegation of tasks or arranging with another veterinarian to cover is an important step toward a life outside of work. A great way to prioritize time off is making a calendar every year of important birthdays, anniversaries, family events, and holidays to get an idea of when vacations should be scheduled. The inclusion of personal days should be a priority to ensure both resting and recharging.

Practicing self-care can start with something as small as a professional haircut, a relaxing bath, taking a moment to dance to music, lighting candles in your home, or even visiting a place that gives you spiritual peace. While veterinary professionals often dedicate their free time to “good causes,” this can also add stress and doesn’t provide a needed reprieve. To do for yourself what you do daily for animals – take proper care – try looking into these:

• Meditation

• Yoga

• Appointment with a mental health professional

· Free counseling is offered through our Membership Assistance Program (MAP)

• Doctor, dentist, or chiropractor appointment

While it can be daunting to take the fi rst step, it is essential that the facets of your life coexist with each other. It is important to keep an eye out for stress indicators and act on them. Just as you care for your patients, you must care for and tend to yourself and your needs. To have a long and enjoyable career, both parts of life must come into balance without one consuming the other.

If you or someone you know is suicidal or in emotional distress, contact the National Suicide Prevention

Lifeline at 988. Trained crisis workers are available to talk 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Your confidential and toll-free call goes to the nearest crisis center in the Lifeline national network. Please also utilize our MAP services and attend our wellness CE sessions. Other resources are available from the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and NOMV.

Introducing updated flu strains, only available in the Prestige vaccine line from Merck Animal Health

The Next Generation of FLU Protection

Developed to help protect against influenza viruses threatening horses today, the Prestige line of flu vaccines offers the most encompassing and advanced level of protection against equine influenza.

Horses deserve the best protection we can give them. Contact Merck Animal Health or your veterinarian to learn more about the new Prestige line of vaccines.

www.merck-animal-health-equine.com

Florida ‘13 Clade 1: Based on a highly pathogenic isolate from the 2013 Ocala, Fla. influenza outbreak that impacted hundreds of horses. Florida ‘13 was exclusively identified and isolated through the Merck Animal Health Biosurveillance Program.

Richmond ‘07 Clade 2: Meets World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) guidelines for Clade 2 influenza protection.

IN

Kentucky ‘02: Influenza strain maintained from previous vaccine line.