TOMORROW ANEW

Gabriel Kozlowski

Eduarda Volschan

Luisa Schettino

Monica Vieira Eisenberg

What will be different TOMORROW ?

—

200 participants 4 NGOs 10 photographers 8 interviews 22 countries 2020–2022

paramount. > Carlos Saldanha. The pandemic has laid bare the painful irrationalities of our politico-economic rationale. Talks about a new normal or a post-normal arise not because we cannot go back to the world as it was before, but because we should not. Locked up in what is undoubtedly the largest social experiment in the history of civilization, “the imperative to re-imagine the planet” (to borrow the term from scholar Gayatri Spivak) is no longer the duty of scholars, experts, cultural commentators, or political leaders. Anyone can and everyone should partake in this common task.

> Daniel Daou. Societies once geared toward the future, as in the time of the modern avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century, have seen their horizons of expectation blurred, dramatically reduced. In a world where the globe shrank, we were left with only the compressed and precarious present. After all, the economy is based precisely on the anticipated sale of the future through debt and credit. Now, condemned to an even narrower future horizon, facing a distressing present that we don’t know how long it will last, it is not difficult to imagine dystopian scenarios for the near future.

> Guilherme Wisnik. You know, even though this happens every day, Tomorrow, I still have dreams about what you can bring. Not only dreams, but also plans, hopes, and of course illusions. I’m not sure why, but I always end up forgetting that you are made primarily of intentions. Without intending to, you end up—almost always—being an inert continuation of the Now. > Luis Nobrega. In this moment of suspension, we can reflect on our frantic travels and constant commute, the rush to catch up and chaise phantom growth ideas often empowered by extractive greed and unsustainable economic logic.

> Malkit Shoshan. Depending on if you are an optimist, a cynic, a pessimist, an idealist, a believer, a denier, tomorrow may now look very different, or it may look very similar to what you expected —with only slightly annoying differences. > Pedro Gadanho. The children of the neighborhood have taken the time of crisis as an opportunity to create, as so many have done in turbulent times before them. They have contributed their own glimmers of hope in the form of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. Each rainbow is a premature augury, drawn during the peak of New York’s curve. These small gestures of crayon, marker, or finger paint represent a faith that will continue after the storm. > Diana Flatto. For those who are doubly fortunate to remain healthy and to be able to observe a sliver of the world through the window, the Apocalypse is strange. Everything is still outside, trees standing, roofs in place, and few people in sight, although the fact that many people wear masks adds something different to the scene. The future announces itself in small everyday displacements, in the attitudes that allow us to glimpse it. Masks: self-fear, solidarity with others, the feeling of a common destiny, fear of the whole species, trust in science, active obedience. > Sidney Chalhoub. It is difficult to know sociologically what will become of the post-Coronavirus world. It is easier to predict “our” world. I remember that, when I was cured of cancer, more than 20 years ago, when the disease was more associated with death than today, I felt unprecedented pleasure in admiring the sea, for example, which I used to see daily without feeling anything special. > Zuenir Ventura.

200 participants 4 NGOs 10 photographers 8 interviews 22 countries 2020–2022

TOMORROW ANEW

Book Editors

Gabriel Kozlowski

Eduarda Volschan

Campaign Authors

Gabriel Kozlowski

Luisa Schettino

Monica Vieira Eisenberg

AFLUENTE, 2023

— What will be different TOMORROW ?

Copyright © 2023 by Gabriel

Kozlowski

Original title

Tomorrow Anew - What will be different tomorrow?

Translation

Laura Folgueira

Cover design

NESS

The copyright on the photographs is reserved and guaranteed.

Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil)

Kozlowski, Gabriel

Tomorrow Anew / Campaign author Gabriel Kozlowski, Luisa Schettino, Monica Vieira Eisenberg, book editors Gabriel Kozlowski; Eduarda Volschan. -Rio de Janeiro, RJ : Afluente, 2023

ISBN 978-65-85724-14-2

1. Artes 2. COVID-19 - Pandemia 3. FuturoPerspectiva 4. Mudanças sociais 5. Pós-pandemia

I. Schettino, Luisa. II. Eisenberg, Monica Vieira. III. Volschan, Eduarda. IV. Título.

23-167356

CDD-700

Índices para catálogo sistemático:

1. Artes 700

Tábata Alves da Silva - Bibliotecária - CRB-8/9253

To all those who allowed us to dream of a new tomorrow.

Publisher

AFLUENTE

Editorial Production + Design NESS

Production Editor

Agustin Schang

Graphic Designer

Santiago Passero

Translation

Laura Folgueira

Transcription

Joana Martins

Proofreading

Steve Yolen

Photographers

Cassandra Cury

Cristiana Lima

Delfim Martins

Juliana Lima

Luciana Whitaker

Marcos Amend

Rafael Costa

Ricardo Teles

Rogério Reis

Sergio Ranalli

Collaborators

Alessandra Fischer

Miguel Darcy

Pedro Brito

Isabella Simões

Iara Carneiro

Sponsors

DRCLAS — Harvard David Rockefeller

Center for Latin American Studies

POLES — Political Ecology of Space

Prior + Partners

BrazilFoundation

Book

Campaign

Authors

Gabriel Kozlowski

Luisa Schettino

Monica Vieira Eisenberg

Team

Ariel Kozlowski

Helena Wajnman

Max Ghenis

Maria Kozlowski

Leticia Schettino

Collaborators

Refik Anadol Studio, artwork

NESS Magazine, media

Create - Pensamentos Online, web developer

Fleichman Advogados, law firm

Richard Sanches, copy editor and translator

Partner NGOs

Brazil Foundation

Conservação Internacional - Brasil

Instituto BEI

Give Directly

Especial Benefactors

Thomas Pucher

Julie Bedard

Pericles

Paul Petalas

Special Thanks

Rebecca Tavares, President and CEO Brazil Foundation

Tomas Alvim, Co-founder Instituto BEI

Marisa Moreira Salles, Co-founder Instituto BEI

Refik Anadol, Artist and Director of Refik Anadol Studio

Helena Monteiro, Executive Director

Brazil Office, Harvard DRCLAS

Tiago Genoveze, Program Manager, Harvard DRCLAS

Laura Fierro, Architect and Principal at Studio Fierro

Delfim Martins, Photographer

Julius Widemann, Book Editor and Founder at AFLUENTE

Institutional Support

Tide Setúbal Foundation

Support Campaign for the Indigenous Peoples of Xingu

Indigenous Land Association of Xingu (ATIX)

Arq.Futuro

MIT MISTI XDivers

Individual Support

Marina Roesler

Gilberto & Christa

Ilana Lipsztein

Michael Naify

Angelica Walker

Luis Nobrega

Olivia Serra

André Volschan

Isaac Volschan Jr.

Pedro Rodrigues

Sean Rivett

Mariela Melamed

Stuart Smith

Paula Reidbord

Marcia Grostein

Adriana Lucena

Photographers

Cassandra Cury

Cristiana Lima

Delfim Martins

Juliana Lima

Luciana Whitaker

Felix Leather

Nico Escribano

Robert Salvesen

Florença Rezende

Gabrielle Grinstein

Cristiana Mascarenhas

Nick O'Farrell

Marcos Amend

Rafael Costa

Ricardo Teles

Rogério Reis

Sergio Ranalli

Reflection Categories & Keywords 1 Index 3 Visual Summary 15 Campaign Call 25 Introduction 27 42 Cell 35 Responses 01 to 35 37 Interviews I and II 70 Hiatus 95 Responses 38 to 74 97 Interviews III and IV 134 Debris 151 Responses 78 to 114 153 Interviews V and VI 200 Locus 219 Responses 117 to 152 221 Interviews VII and VIII 276 Care 301 Responses 155 to 195 303 356 Responsibility 339 Postface 347 Photographic Essays 354

Table of Contents

Reflection Categories

T E R V I O P NOTE NARRATIVE ESSAY RECALL SCRIPT INTERVIEW PHOTOGRAPH

1

Keywords

IS O ISOLATION N AT NATURE LOS RST CHA N OS NOSTALGIA P OL POLITICS IN T INTROVERSION R ES RESPONSIBILITY INQ HOP UNC A DP ADAPTATION T EC TECHNOLOGY RUT R EG REGRESSION C OL COLLECTIVITY HLP E XP EXPECTATION URB

ROUTINE LOSSES HOPE RESTART INEQUALITY HELPLESSNESS UNCERTAINTY CHALLENGES URBAN 2

3 Conteúdo USA ISR HOP USA uncertainty , losses , collectivity , hope 05/29/2020 isolation , introversion , expectation , hope 09/07/2020 04/20/2020 R E isolation , uncertainty , technology , responsibility 04/19/2020 06/19/2020 challenges , collectivity , responsibility , restart 05/29/2020 R R R CAN introversion , inequality , collectivity , urban R V BRA USA BRA BRA UK USA UK USA USA USA ARG BRA MEX USA challenges , collectivity , responsibility , hope isolation , challenges , responsibility , expectation 03/14/2022 06/18/2020 R R isolation , introversion , collectivity , technology isolation , introversion , routine , restart 05/31/2020 09/02/2020 05/31/2020 07/22/2020 R R E isolation , routine , challenges , collectivity isolation , collectivity , technology , restart 10/06/2020 06/05/2022 isolation , routine , technology , responsibility losses , collectivity , restart , hope 05/27/2020 06/27/2020 isolation , introversion , routine , uncertainty 05/26/2020 isolation , routine , uncertainty , expectation isolation , routine , uncertainty , nostalgia 06/23/2020 03/06/2020 R O USA nostalgia , expectation , restart , hope T R R R isolation , collectivity , responsibility , hope R 07/12/2022 04/15/2020 E E BRA BRA USA CAMPAIGN CALL Tomorrow Anew 25 INTRODUCTION Gabriel Kozlowski 27 CELL 001 Diana Flatto 37 002 Malkit Shoshan 38 003 Manuel Blanco-Ons Fernández 39 004 Neeraj Bhatia 39 005 Joe Jacobson 41 006 Sergio Galaz-García 42 007 Andrés Passaro 43 008 Max Ghenis 45 009 Lui Farias 45 010 Angelica Walker 48 011 Ilana Lipsztein 49 012 Mary Lapides Shela 50 013 Bartira Volschan 51 014 Pedro Varella 51 015 Sophie & Andrew Harkness 52 016 Jane Hall 53 017 Nazareth Ekmekjian 53 018 Nicolas Entel 54

4 05/25/2020 BRA isolation , challenges , restart , hope R 05/16/2020 BRA introversion , collectivity , technology , adaptation T BRA isolation , introversion , uncertainty , hope 05/04/2020 BRA BRA BRA isolation , introversion , collectivity , adaptation 05/01/2020 05/01/2020 routine , collectivity , politics , responsibility routine , collectivity , nostalgia , adaptation 05/02/2020 R T T T BRA SPN ISR BRA BRA BRA USA BRA BRA BRA BRA routine , challenges , uncertainty , adaptation 03/08/2022 R isolation , collectivity , technology , nostalgia isolation , introversion , routine , uncertainty 04/27/2020 11/04/2020 05/21/2020 04/11/2022 R R R R routine , challenges , uncertainty , technology isolation , routine , inequality , collectivity isolation , introversion , challenges , uncertainty 03/11/2022 28/03/2022 helplessness , losses , nostalgia , restart R isolation , routine , expectation , restart challenges , collectivity , responsibility , hope collectivity , technology , expectation , restart isolation , introversion , routine , adaptation 04/14/2022 06/25/2022 07/26/2020 05/26/2020 06/15/2022 R R R R V R IND COL collectivity , politics , technology , nature politics , responsibility , regression , adaptation 07/07/2022 07/28/2022 I I I & II 019 Marcela Berrio 54 020 Beni Barzellai 56 021 Monica Eisenberg 56 022 Vitor Pamplona 57 023 Gildete dos Santos Mello 57 024 Ana Cristina Downey 58 025 Tamara Klink 58 026 Lara Coutinho 58 027 Makau Mehinako 59 028 Marta M. Roy Torrecilla 60 029 Nitzan Zilberman 62 030 Bruno Rodrigues 62 031 Liv Soban 64 032 Isaac Volschan 65 033 Beatriz Guimarães 66 034 Takumã Kuikuro 67 035 Melissa Du 67 INTERVIEWS 036 Sheila Jasanoff 71 037 Ana Cristina González Vélez 85

5 HIATUS 038 Pinar Yoldas 97 039 Zuenir Ventura 100 040 José Roberto de Castro Neves 100 041 David Birge 101 042 Michael Waldrep 103 043 Murilo Ferreira 105 044 Sonia Esteves 106 045 Monica Nogueira 106 046 Victor Orestes 107 047 Agustin Schang 107 048 Mary Gao 108 049 BA Mir 108 050 Gabriella Vieira de Carvalho 109 051 Helena Moreira Dias 109 052 Gisela Zincone 109 053 Daniel Milagres 110 054 Mauro Ventura 111 055 Diego Portas 112 056 Anne Bogart 113 057 Pedro Pirim 117 058 Bruno Tavares 117 059 Maria Eduarda Moog 118 060 Mariana Meneguetti 119 UK BRA USA BRA BRA isolation , technology , restart , hope 06/16/2020 R 05/01/2020 06/21/2022 politics , responsibility , expectation , hope challenges , losses , inequality , responsibility 04/26/2020 nature , expectation , restart , hope 08/07/2020 T isolation , challenges , inequality , collectivity introversion , politics , expectation , restart 06/15/2020 06/30/2020 R R R V ARG USA BRA BRA isolation , collectivity , nature , restart 05/01/2020 collectivity , responsibility , adaptation , restart R R BRA CAN BRA BRA CAN BRA ARG BRA USA BRA BRA uncertainty , collectivity , adaptation , hope 05/11/2020 R E losses , collectivity , responsibility , hope isolation , collectivity , expectation , hope uncertainty , losses , inequality , regression 06/03/2020 05/26/2020 05/16/2020 05/21/2020 05/11/2020 05/11/2020 R T T R challenges , collectivity , technology , adaptation uncertainty , helplessness , restart , hope challenges , collectivity , politics , restart 05/16/2020 uncertainty , technology , adaptation , hope R collectivity , technology , responsibility , hope losses , collectivity , expectation , hope losses , inequality , collectivity , politics 06/20/2020 05/01/2020 04/24/2020 05/10/2020 R R R R T USA USA BRA BRA isolation , urban , adaptation , restart challenges , helplessness , collectivity , expectation 05/04/2020 E isolation , losses , responsibility , hope 05/10/2020 06/14/2020 R challenges , losses , collectivity , responsibility T R V 06/19/2020 08/05/2020

6 061 Manuela Müller 119 062 J. Charlesworth & T. Parsons 120 063 Atapucha Waujá 121 064 T. Vaughan & T. Hofmeier 121 065 Xhulio Binjaku 122 066 Barbara Graeff 123 067 José Guilherme Cantor Magnani 124 068 Auritha Tabajara 125 069 Alessandra Fischer 125 070 Lucio Salvatore 126 071 Fernanda Germano 128 072 Bárbara Buril 129 073 Kapisi Kamayura 131 074 Adalberto Neto 132 INTERVIEWS 075 Carmen Silva 135 076 Vita Susak 143 BRA USA 07/07/2022 isolation , uncertainty , politics , expectation isolation , inequality , politics , adaptation 05/28/2020 USA BRA uncertainty , losses , politics , expectation 05/27/2020 T routine , challenges , uncertainty , adaptation 03/07/2020 R collectivity , nature , restart , hope 05/29/2020 R R R BRB AUS BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA collectivity , responsibility , expectation , hope isolation , introversion , routine , uncertainty 05/28/2020 05/15/2020 T R collectivity , expectation , restart , hope 05/27/2022 R introversion , challenges , collectivity , adaptation 06/27/2020 isolation , challenges , collectivity , responsibility isolation , introversion , collectivity , expectation helplessness , technology , nature , regression isolation , challenges , uncertainty , losses 04/14/2022 04/05/2020 05/27/2020 03/05/2022 R E T R R BRA 06/10/2022 challenges , collectivity , responsibility , expectation T BRA 03/15/2022 UKR 03/06/2022 I losses , politics , collectivity , hope collectivity , urban , routine , expectation I III & IV

DEBRIS

7

077 Fernando Henrique Cardoso 153 078 Ani Liu 154 079 Kátia Bandeira de Mello Gerlach 155 080 Denis Mooney 158 081 Pedro Roquette-Pinto 158 082 Mae-ling Lokko 159 083 Marcelo Borborema 160 084 Rosiska Darcy de Oliveira 161 085 Adil Aly 161 086 Caroline A. Jones 162 087 Catarina Flaksman 166 088 João Costa 167 089 Daniel Daou 168 090 Ana Altberg 169 091 Daniel Wilkinson 170 092 Guilherme Wisnik 170 093 Laura González Fierro 174 094 Olivia Serra 176 095 Carlos Saldanha 176 096 Aditya Barve 177 097 Claudia Escarlate 178 098 Cripta Djan 178 099 Pedro Zylbersztajn 179 BRA challenges , inequality , collectivity , hope 05/11/2020 T BRA collectivity , politics , responsibility , adaptation 05/30/2020 R BRA challenges , nature , responsibility , expectation 10/16/2020 T BRA 06/13/2020 R challenges , politics , nature , hope BRA 05/29/2020 introversion , inequality , collectivity , politics R USA inequality , responsibility , restart , hope 07/06/2020 R MEX inequality , politics , adaptation , expectation 07/02/2020 E BRA challenges , uncertainty , politics , technology 08/03/2020 E USA isolation , inequality , collectivity , politics 06/15/2020 E MEX 06/06/2020 03/29/2022 05/26/2020 06/03/2022 isolation , inequality , politics , expectation R V R V BRA 11/12/2020 T challenges , uncertainty , inequality , urban BRA 05/24/2020 T introversion , responsibility , expectation , restart IND introversion , inequality , collectivity , restart inequality , responsibility , expectation , hope BRA 05/04/2020 03/30/2022 R V USA collectivity , politics , technology , hope 06/26/2020 R BRA collectivity , politics , expectation , hope 05/08/2020 R BRA USA 05/30/2020 E isolation , uncertainty , losses , politics UAE 08/30/2020 T challenges , collectivity , expectation , hope BRA 05/16/2020 challenges , uncertainty , helplessness , regression R BRA challenges , helplessness , politics , responsibility 06/22/2020 R BRA uncertainty , collectivity , regression , hope 05/29/2020 T AUS challenges , collectivity , politics , expectation 05/06/2020 R GHA PHL challenges , collectivity , politics , hope 06/21/2020 06/06/2022 R V

8 100 Ascânio Seleme 180 101 Bárbara Fonseca 180 102 Karla Mendes 183 103 Vitória Hadba 183 104 Tábata Amaral 184 105 Iker Gil 184 106 Linda Chavers 187 107 Gustavo Hadba 187 108 Murdoch Rawson 187 109 Ana Fontes 188 110 M. de Troi & W. Quintilio 189 111 Isabela Fonseca 195 112 Pedro Brito 195 113 Luis Erlanger 197 INTERVIEWS 114 Admir Masic 201 115 Adèle Naudé Santos 211 USA USA inequality , collectivity , responsibility , expectation 07/01/2020 T BRA challenges , uncertainty , inequality , responsibility 05/18/2020 R BRA 06/16/2020 T challenges , helplessness , inequality , regression 05/25/2020 04/07/2022 BRA R inequality , responsibility , restart , hope 05/16/2020 inequality , politics , urban , expectation BRA 06/16/2020 isolation , introversion , inequality , urban E BRA 04/14/2022 collectivity , politics , responsibility , hope R BRA helplessness , inequality , responsibility , regression 05/18/2020 R UK inequality , responsibility , expectation , hope 06/02/2020 R BRA inequality , collectivity , politics , responsibility 05/30/2020 T R V BRA helplessness , politics , urban , expectation 07/14/2022 R BRA challenges , collectivity , politics , technology 03/31/2020 E BRA 03/14/2022 uncertainty , politics , technology , regression R AFS 04/03/2022 routine , collectivity , urban , expectation I BRA uncertainty , collectivity , expectation , hope 07/14/2022 R CRO 10/09/2022 challenges , inequality , politics , adaptation I V & VI

LOCUS

9

116 Bruno Carvalho 221 117 Renata Minerbo 223 118 Osborne Macharia 223 119 Leticia Cotrim da Cunha 224 120 Carlos Saul Zebulun 226 121 Ariel Kozlowski 226 122 Mariel Collard Arias 227 123 Sidney Chalhoub 228 124 Marina Grinover 230 125 Naomi Davy 231 126 Michael Batty 232 127 Isaac Karabtchevsky 238 128 Daniel Corsi 238 129 Martim Moulton 242 130 Christiana Figueres 242 131 Pedro Gadanho 244 132 Maria Manuela Moog 244 133 Alejandro de Miguel Solano 245 134 Lúcia Guimarães 254 135 Joris Komen 254 136 Marko Brajovic 257 137 Simone Klabin 259 138 Ricardo Trevisan 260 BRA HOP USA CR POR collectivity , responsibility , restart , hope 05/16/2020 R challenges , inequality , politics , urban 05/27/2020 T NAM 01/17/2021 R urban , nature , responsibility , adaptation 03/24/2020 05/29/2020 challenges , politics , nature , responsibility nature , responsibility , expectation , hope E R politics , technology , urban , adaptation 05/05/2020 challenges , technology , urban , hope 06/30/2020 R BRA challenges , uncertainty , urban , expectation 06/15/2020 T BRA isolation , responsibility , expectation , restart 04/20/2020 E E KEN UK BRA BRA challenges , uncertainty , collectivity , nature nature , responsibility , restart , hope 05/16/2020 T inequality , urban , nature , hope 06/16/2020 inequality , collectivity , urban , nature R 07/31/2020 03/29/2022 06/17/2020 06/03/2022 R V R V BRA collectivity , nature , responsibility , regression 05/29/2020 T 05/29/2020 04/04/2022 R V nature , responsibility , restart , hope 08/11/2020 R inequality , collectivity , nature , responsibility collectivity , nature , responsibility , hope 04/26/2020 06/29/2020 06/02/2020 05/16/2020 R R R R routine , politics , nature , responsibility collectivity , urban , nature , adaptation 05/03/2020 challenges , technology , responsibility , expectation R collectivity , technology , urban , adaptation collectivity , nature , adaptation , expectation urban , nature , responsibility , hope 05/14/2020 05/04/2020 R E MEX BRA BRA BRA USA BRA UK BRA BRA USA BRA

10 139 Cauê Capillé 261 140 Philip Yang 263 141 Natalia Timerman 266 142 Barbara Veiga 266 143 Carlos Nobre 266 144 Gustavo Neiva 267 145 Amanda Palma 271 146 Helena Singer 271 147 Shirley Krenak 272 148 Beth Kozlowski 273 149 Ricardo Bayão 273 150 Marcia Kambeba 274 INTERVIEWS 151 Sônia Guajajara 277 152 Beto Veríssimo 291 BRA BRA 05/30/2020 03/29/2020 07/21/2020 04/05/2022 R V E V BRA politics , nature , responsibility , hope 04/05/2022 R BRA challenges , nature , responsibility , restart 04/31/2022 R BRA 05/15/2022 R collectivity , politics , responsibility , expectation challenges , technology , urban , responsibility BRA 04/04/2022 collectivity , politics , expectation , hope R challenges , politics , nature , responsibility BRA challenges , helplessness , nature , responsibility 03/31/2022 R BRA challenges , urban , adaptation , restart 06/15/2020 E BRA collectivity , nature , responsibility , hope 06/26/2022 R BRA 07/15/2022 R uncertainty , nature , responsibility , hope BRA challenges , collectivity , nature , responsibility 03/21/2022 T BRA challenges , collectivity , nature , responsibility 02/23/2022 R BRA 04/12/2022 collectivity , urban , nature , expectation I BRA 05/29/2022 collectivity , nature , expectation , restart I VII & VIII

CARE

11

153 Mohsen Mostafavi 303 154 Dado Villa-Lobos 312 155 João Anzanello Carrascoza 313 156 Adam Haar Horowitz 313 157 Jeremy Bailey 314 158 Heloisa Escudeiro 315 159 Anna Maria Moog Rodrigues 315 160 Maira Genovese 316 161 Mark Bryan 316 162 Sergio Branco 317 163 B. Castelar & J. Moreira 319 164 Eime Tobari 319 165 Debora Martini 320 166 Igor Lima 320 167 Higia Ikeda 321 168 Marcos Frazão 321 169 Antônio de Salles Guerra Lage 322 170 Paula Braun 322 171 Ontxa Mehinaku 323 172 Isabella Simões 323 173 Guilherme Alves 324 174 Julie Michiels 324 175 Mari Mel Ostermann 324 USA 05/25/2020 T collectivity , urban , responsibility , expectation BRA 05/20/2020 T collectivity , adaptation , expectation , hope BRA BRA BRA IR uncertainty , collectivity , adaptation , hope collectivity , responsibility , expectation , hope isolation , adaptation , expectation , hope collectivity , politics , nature , adaptation 04/04/2022 R politics , technology , responsibility , adaptation 09/27/2020 05/04/2020 challenges , uncertainty , adaptation , restart T 05/27/2020 06/05/2020 R T E CAN UK USA BRA USA BRA BRA USA introversion , challenges , uncertainty , restart responsibility , expectation , restart , hope 10/28/2020 05/27/2020 06/16/2020 08/31/2020 06/25/2020 04/03/2022 R R BRA 06/15/2020 collectivity , responsibility , expectation , hope R T R V challenges , inequality , responsibility , hope challenges , collectivity , technology , adaptation collectivity , technology , responsibility , hope 04/26/2020 08/15/2022 responsibility , expectation , restart , hope R R T BRA collectivity , politics , responsibility , hope 06/15/2020 T BRA challenges , collectivity , politics , responsibility 08/07/2020 T BRA losses , responsibility , restart , hope 03/05/2022 T BRA 07/13/2022 R challenges , uncertainty , inequality , hope USA BRA 06/04/2020 collectivity , responsibility , expectation , restart R BRA challenges , collectivity , responsibility , hope 05/20/2020 T BRA collectivity , responsibility , expectation , hope 03/14/2022 R BRA collectivity , responsibility , restart , hope 06/11/2020 R

12 176 Tereza C. Mc Courtney 325 177 Miguel Darcy de Oliveira 325 178 Marcelo Maia Rosa 325 179 Ney Latorraca 326 180 José Benedito Tui(~) Huni Kuin 326 181 Rita Braune Guedes 327 182 Adriana Lucena 328 183 Cláudio Domênico 328 184 Rafael Marengoni 329 185 Fernanda Ferreira 329 186 Gabriel Kozlowski 330 187 Charles Silva 332 188 Seamus O'Farrell 333 189 Tina Correia 334 190 Luis Nobrega 336 USA BRA isolation , introversion , expectation , hope 05/03/2020 T BRA isolation , collectivity , urban , adaptation 11/16/2020 E BRA adaptation , expectation , restart , hope 05/26/2020 R BRA 05/01/2020 R collectivity , politics , responsibility , hope BRA 05/17/2020 T challenges , uncertainty , adaptation , expectation BRA 04/25/2020 R introversion , collectivity , responsibility , hope BRA 05/07/2020 introversion , collectivity , adaptation , expectation R losses , adaptation , restart , hope 06/01/2020 BRA isolation , introversion , challenges , uncertainty 04/26/2020 T BRA challenges , responsibility , adaptation , expectation 04/27/2020 R R BRA collectivity , responsibility , expectation , hope 05/08/2020 T BRA routine , challenges , uncertainty , collectivity 03/23/2022 R BRA challenges , inequality , collectivity , restart 05/29/2020 R AUS isolation , routine , expectation , hope 05/28/2020 R 10/09/2020 04/30/2022 BRA collectivity , politics , technology , adaptation R V

13 RESPONSIBILITY Tomorrow Anew 339 POSTFACE Rebecca Tavares 347 M. Moreira Salles & T. Alvim 347 Graham Goymour 347 Tiago Genoveze 347 PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAYS 191 Cassandra Cury 355 192 Cristiana Lima 365 193 Delfim Martins 375 194 Juliana Lima 385 195 Luciana Whitaker 395 196 Marcos Amend 405 197 Rafael Costa 415 198 Ricardo Teles 425 199 Rogério Reis 435 200 Sérgio Ranalli 445 BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA 06/2022 11/2018 04/2019 07/2022 01/2020 08/2018 07/2021 08/2012 07/2011 F F F F F T F F T T F F F USA BRA UK E T USA USA collective , children , portraits , rituals buildings , customs , children , landscape buildings , landscape , portraits , rituals children , landscape , portraits , rituals collective , buildings , children , customs children , portraits , rituals , landscape customs , children , landscape , rituals buildings , landscape , portraits , rituals buildings , children , landscape , portraits buildings , customs , children , landscape 08/2022 09/2022 08/2022 02/2023 09/2022 08/2022

14

Visual Summary

15

2020 • 2022

16

Responses x Keywords

Adalberto Neto

Adam Haar Horowitz

Adil Aly Aditya Barve

Adriana Lucena

Agustin Schang

Alejandro de Miguel Solano

Alessandra Fischer

Amanda Palma

Ana Altberg

Ana Cristina Downer

Ana Fontes

Andrés Passaro

Angelica Walker

Ani Liu

Anna Maria Moog Rodrigues

Anne Bogart

Antonio de Salles Guerra Lage

Ariel Kozlowski

Ascânio Seleme

Atapucha Wauja

Auritha Tabajara

BA Mir

Barbara Fonseca

Barbara Graeff

Barbara Veiga

Bartira Volschan

Beatriz Guimarães

Beni Barzellai

Berta Castelar e João Moreira

Beth Kozlowski

Bruno Carvalho

Bruno Rodrigues

Bruno Tavares

Bárbara Buril

Carlos Nobre

Carlos Saldanha

Carlos Saul Zebulun

Caroline A. Jones

Catarina Flaksman

Cauê Capillé

Charles Silva

Christiana Figueres

Claudia Escarlate

Claudio Domênico

Cripta Djan

Dado Villa-Lobos

Daniel Corsi

Daniel Daou

Daniel Milagres

Daniel Wilkinson

David Birge

Debora Martini

Denis Mooney

Diana Flatto

Diego Portas

Eime Tobari

Fernanda Ferreira

Fernanda Germano

Fernando Henrique Cardoso

Gabriel Carvalho

Gabriella Vieira de Carvalho

Gildete dos Santos Mello

Gisela Zincone

Guilherme Alves

Guilherme Wisnik

Gustavo Hadba

Gustavo Neiva

Helena Moreira Dias

Helena Singer

Heloisa Escudeiro

Higia Ikeda

Igor Lima Iker Gil

Ilana Lipsztein

Isaac Karabtchevsky

Isabela Fonseca

Isabella Mayworm

Isabella Simões

Jane Hall

Jeremy Bailey

Jessica Charlesworth & Tim Parsons

Joe Jacobson

Joris Komen

José Benedito Huni Kui

José Guilherme Cantor Magnani

José Roberto de Castro Neves

João Anzanello Carrascoza

João Costa

Julie Michiels

Kapisi Kamayura

Karla Mendes

Kátia Bandeira de Mello Gerlach

Lara Coutinho

Laura González Fierro

Leticia Cotrim da Cunha

Linda Chavers

Liv Soban

Lucio Salvatore

Lui Farias

Luis Erlanger

Luis Nobrega

Lúcia Guimarães

Mae-ling Lokko

Maira Genovese

Makau Meinhako

Malkit Shoshan

Manuel Blanco-Ons Fernández

Manuela Müller

Marcela Berrio

Marcelo Borborema

Marcelo Maia Rosa

Marcelo de Troi e Wagner

Marcia Kambeba

Marcos Frazão

Mari Mel Ostermann

Maria Eduarda Moog

Maria Manuela Moog

Mariana Meneguetti

Mariel Collard Arias

Marina Grinover

Mark Bryan Marko Brajovic

Marta M. Roy Torrecilla

Martim Moulton

Mary Gao

Mary Lapides Shela

Mauro Ventura

Max Ghenis

Melissa Du

Michael Batty

Michael Waldrep

Miguel Darcy de Oliveira

Mohsen Mostafavi

Monica Eisenberg

Monica Nogueira

Murdoch Rawson

Murilo Ferreira

Naomi Davy Natalia Coachman

Natalia Timerman

Nazareth Ekmekjian

Neeraj Bhatia

Ney Latorraca

Nicolas Entel Nitzan Zilberman

Olivia Serra Ontxa

Meinhako

Osborne Macharia

Paula Braun

Pedro Brito

Pedro Gadanho

Pedro Pirim

Pedro Roquette-Pinto

Pedro Varella

Pedro Zylbersztajn

Philip Yang Pinar Yoldas

Rafael Marengoni

Renata Minerbo

Ricardo Bayão

Ricardo Trevisan

Rita Braune Guedes

Rosiska Darcy de Oliveira

Seamus O'Farrell

Sergio Branco

Sergio Galaz-García

Shirley Krenak

Sidney Chalhoub

Simone Klabin

Sonia Esteves

Quintilo

Sophie and Andrew Harkness

Tadeu Fidalgo

Takumã Kuikuro

Tamara Klink

Tamara Vaughan & Timothy Hofmeier

Tereza C. Mc Courtney

Tina Correia

Tábata Amaral

Victor Orestes

Vitor Pamplona

Vitória Hadba

Xhulio Binjaku

Zuenir Ventura

CARE LOCUS DEBRIS

CELL 17

HIATUS

ADAPTATION

CHALLENGES

COLLECTIVITY

EXPECTATION

HELPLESSNES

HOPE

INEQUALITY

INTROVERSION

ISOLATION

LOSSES

NATURE

NOSTALGIA

POLITICS

REGRESSION

RESPONSIBILITY

RESTART

ROUTINE

TECHNOLOGY

UNCERTAINTY

URBAN

18

Def:

1. No dia seguinte ao de hoje

2. Num tempo futuro

Def:

1. recently or lately

2. anew or afresh

Def:

the part of existence that is measured in minutes, days, years, etc., or this process considered as a whole

in Portuguese: novo

in Portuguese: tempo

Def: 1. 2. generally the in amanhã

120 130 140 times / vezes > > > > > > amanhã word frequency / frequência de palavras word frequency [137] [130] [122] [115]

em

Inglês: tomorrow

new time tomorrow 70 80 90 future change será one social people life world many tempo todos also pessoas di erent way need pandemia

[85] [89] [89] [89] [87] [82] [72] [72] [70] [69] [67] [66] [66] [68] 19

Most used words

Def:

1. the day after today

2. used more generally to mean the future

in Portuguese: amanhã

Def:

1. Corresponder a determinada identificação ou qualificação

2. Consistir em.

em Inglês: to be

Def:

1. relativo ao Brasil ou o que é seu natural ou habitante

em Inglês: Brazil

100 110 > > > > > > [115] [110] [108] [97] tomorrow mundo ser Brasil 40 50 60 way need pandemia pandemic hoje muito ainda like architecture tudo nossa futuro global diferente political society crisis vida casa city agora today human virus environment work mesmo home momento

[64] [64] [61] [60] [60] [59] [59] [60] [56] [56] [53] [51] [48] [47] [47] [46] [45] [44] [44] [44] [43] [43] [45] [45] [48] [55] [55] [56] [64] [66] [66] 20

28/04/202029/04/202030/04/2020 24/03/2020 26/03/2020 31/03/2020 02/04/2020 05/04/2020 10/04/2020 19/04/2020 20/04/2020 23/04/2020 25/04/2020 26/04/2020 27/04/2020 01/05/2020 02/05/2020 03/05/2020 04/05/2020 05/05/202006/05/202007/05/2020 08/05/2020 10/05/2020 11/05/2020 14/05/2020 16/05/2020 17/05/2020 18/05/202019/05/2020 20/05/2020 21/05/2020 25/05/2020 26/05/2020 27/05/2020 28/05/2020 29/05/2020 30/05/2020 31/05/2020 01/06/2020 02/06/2020 03/06/2020 04/06/202005/06/202006/06/202007/06/2020 11/06/2020 13/06/202014/06/2020 15/06/2020 16/06/2020 17/06/202018/06/2020 19/06/2020 20/06/202021/06/202022/06/202023/06/2020 25/06/2020 26/06/2020 27/06/202028/06/2020 29/06/2020 30/06/2020 01/07/202002/07/202003/07/2020 06/07/2020 07/07/2020 13/07/2020 14/07/2020 18/07/2020 21/07/2020 31/07/2020 03/08/2020 07/08/2020 11/08/2020 15/08/2020 19/08/2020 24/08/2020 30/08/202031/08/2020 02/09/2020 07/09/2020 27/09/202028/09/202029/09/2020 09/10/202010/10/2020 Christiana Figueres Marcelo de Troi e Wagner Quintilio Bárbara Buril Joe Jacobson Neeraj Bhatia Marko Brajovic Mariana Meneguetti Fernanda Ferreira Murilo Ferreira Marina Grinover Anna Maria Moog Rodrigues Claudio Domênico Nitzan Zilberman Adriana Lucena Gildete dos Santos Mello Ana Cristina Downer Michael Waldrep Pedro Pirim Maria Eduarda Moog Rita Braune Guedes Vitor Pamplona Ariel Kozlowski Ney Latorraca Monica Eisenberg David Birge Pedro Zylbersztajn Isaac Karabtchevsky Dado Villa-Lobos Alejandro de Miguel Solano Denis Mooney Marcelo Maia Rosa Rosiska Darcy de Oliveira Miguel Darcy de Oliveira Zuenir Ventura Mauro Ventura Daniel Milagres Diego Portas Olivia Serra Michael Batty Beni Barzellai Helena Moreira Dias Gisela Zincone Tadeu Fidalgo Pedro Roquette-Pinto Vitória Hadba Osborne Macharia Martim Moulton Maria Manuela Moog Gabriel Carvalho Karla Mendes Tereza C. Mc Courtney Ascânio Seleme Guilherme Alves Mari Mel Ostermann Bruno Rodrigues Bruno Tavares Marcela Berrio Cripta Djan Iker Gil Julie Michiels Nicolas Entel Marta M. Roy Torrecilla Gabriella Vieira de Carvalho Aditya Barve Rafael Marengoni Nazareth Ekmekjian Manuela Müller Auritha Tabajara Alessandra Fischer Lúcia Guimarães Adam Haar Horowitz Heloisa Escudeiro Xhulio Binjaku Barbara Grae Seamus O'Farrell Malkit Shoshan Diana Flatto Parsons & Charlesworth Marcelo Borborema Catarina Flaksman Carlos Saul Zebulun Sidney Chalhoub Pedro Gadanho Charles Silva Kátia Bandeira de Mello Gerlach João Costa Tábata Amaral Cauê Capillé Sophie and Andrew Harkness Jane Hall Andrés Passaro Luis Nobrega Murdoch Rawson Naomi Davy Lui Farias BA Mir Marcos Frazão Berta Castelar e João Moreira Laura González Fierro Higia Ikeda Daniel Wilkinson José Roberto de Castro Neves Victor Orestes Caroline A. Jones Ricardo Trevisan Philip Yang Peju Alatise Debora Martini Monica Nogueira Claudia Escarlate Barbara Fonseca Gustavo Hadba Renata Minerbo Eime Tobari Leticia Cotrim da Cunha Max Ghenis Sergio Galaz-García Pinar Yoldas Igor Lima Mary Gao Nearly one-third of the world’s population is living under coronavirus-related restrictions Global coronavirus cases pass the one million mark; deaths exceed 50,000. New York City reports more coronavirus cases than any country Germany approves first trials for a coronavirus vaccine. Brazil's health ministry removes coronavirus data from o icial website 21 Timeline

Susak

Gustavo Neiva recall Andrés Passaro recall Aditya Barve recall Leticia Cotrim da Cunha recall Mae-ling Lokko recall Marta M. Roy Torrecilla recall Michael Waldrep recall Pinar Yoldas recall Cauê Capillé recall Laura González Fierro recall Pedro Zylbersztajn recall Bruno Carvalho recall Sergio Branco recall Diana Flatto recall Sidney Chalhoub recall

27/09/202028/09/202029/09/2020 09/10/202010/10/2020 16/10/2020 29/10/2020 06/03/2022 08/03/2022 11/03/2022 14/03/2022 15/03/2022 29/03/2022 30/03/2022 31/03/2022 01/04/2022 03/04/2022 04/04/2022 05/04/2022 06/04/2022 07/04/2022 11/04/2022 12/04/2022 14/04/2022 20/04/2022 29/04/2022 30/04/2022 02/05/2022 05/05/202206/05/2022 13/05/2022 15/05/2022 27/05/2022 02/06/202203/06/2022 05/06/2022 09/06/2022 30/05/2022 02/06/2022 05/06/2022 09/06/2022 10/06/2022 15/06/2022 21/06/2022 26/06/2022 13/07/2022 14/07/2022 16/07/2022 28/07/2022 28/07/2022 09/10/2022 15/08/2022 Gustavo Hadba Renata Minerbo Eime Tobari Leticia Cotrim da Cunha Max Ghenis Sergio Galaz-García Pinar Yoldas Mae-ling Lokko Fernando Henrique Cardoso Pedro Varella Sergio Branco Melissa Du Mary Lapides Shela Lucio Salvatore Daniel Corsi Agustin Schang Simone Klabin Linda Chavers Daniel Daou Carlos Saldanha Tamara Vaughan & Timothy Hofmeier Isabella Mayworm Natalia Coachman Gustavo Neiva Bruno Carvalho Guilherme Wisnik Sonia Esteves Mariel Collard Arias Adil Aly Mark Bryan Angelica Walker Manuel Blanco-Ons Fernández Mohsen Mostafavi Tina Correia Ana Altberg Jeremy Bailey Tamara Klink Paula Braun Lara Coutinho Marcelo de Troi e Wagner Quintilio Natalia Timerman Barbara Veiga João Anzanello Carrascoza Carlos Nobre Iker Gil recall Tukumã Kuikuru Beto Veríssimo Ana Fontes José Guilherme Cantor Magnani Tina Correia recall Amanda Palma Liv Soban Helena Singer Auritha Tabajara Alessandra Fischer Adalberto Neto Beth Kozlowski Isabella Simões Bartira Volschan Isabela

Vita

Carmen

Fonseca Pedro Brito Ricardo Bayão Maira Genvese Mary Gao Ani Liu Santos Sônia Guajajara Sheila Jasano Ana Cristina González Vélez Admir Masic

Silva Adèle Naudé

Responses Interviews

Recalls 2022 2020 Events Global coronavirus death toll surpasses 500,000 Russia begins production on Sputnik-V Brazil passes 110,000 COVID-19 deaths and 2.4 million cases. First case of COVID-19 reinfection reported in Hong Kong. Global COVID-19 deaths pass one million Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine shows acceptable safety. Brazil passes 150,000 COVID-19 deaths, giving the second-highest death-toll after the United States. The World Health Organization declares that Europe is again the "epicenter" of the pandemic WHO strengthens its endorsement of booster shots, while still emphasizing the need for primary shots A third of the world population remains unvaccinated from COVID-19 according to the WHO. WHO says over 65 percent of Africans have been infected with COVID-19 since the beginning of the pandemic WHO urges people worldwide to continue wearing masks. Research links exposure to air pollution to worse COVID-19 outcomes World Health Organization (WHO) releases a preliminary report on the origins of COVID-19. The United States reports over 55,000 new coronavirus cases, marking a new daily global record WHO reports that the United States and Brazil made up half of the daily increase in coronavirus cases globally. 22

Participants

Introversion,Challenges,Uncertainty,Restart Collectivity,Technology,Responsibility,Hope Isolation,Introversion,Challenges,Uncertainty, Collectivity,Politics,Technology,AdaptationCollectivity,Technology,Responsibility,Hope Collectivity,Responsibility,Expectation,Hope Collectivity,Politics,Responsibility,Hope Routine,Collectivity,Responsibility,Expectation Introversion,Challenges,Collectivity,Adaptation Introversion,Collectivity,Nature,HopeChallenges,Collectivity,Technology,Adaptation Collectivity,Politics,Nature,AdaptationCollectivity,Responsibility,Restart,HopeCollectivity,Responsibility,Expectation,Restart Challenges,Collectivity,Politics,Responsibility Challenges,Inequality,Collectivity,Restart Losses,Responsibility,Restart,Hope

Helplessness,Nature,Responsibility

Isolation,Routine, Expectation,Hope

Challenges, Collectivity, Responsibility,Hope

Collectivity, Adaptation, Expectation,Hope

Collectivity,Urban, Responsibility, Expectation

Introversion, Collectivity, Adaptation, Expectation

Isolation, Collectivity, Urban, Adaptation

Isolation, Introversion, Expectation, Hope

Introversion, Challenges, Collectivity, Expectation

Collectivity, Politics, Responsibility, Hope

Challenges, Uncertainty, Inequality, Hope

Adaptation, Expectation, Restart, Hope

Challenges, Responsibility, Adaptation, Expectation

Introversion, Collectivity, Responsibility, Hope CAN ISR USA SPN BRA BRA BRA BRA CAN BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA USA BRA BRA BRA BRAUK BRA

USA/BRABRABRABRAAUSBRABRAUSABRABRABRA BRA BRA

Collectivity, Responsibility, Expectation, Hope BRABRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA

BRA

Uncertainty, Collectivity, Adaptation, Hope BRA

BRA IRN BRA USA USA BRA ? AS BRA BRA UK KEN USABRABRABRAMEXBRAPORBRABRABRABRABRABRA UK BRA BRA CR SPN USA NAM BRAUSA/BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA USA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA USA USA UK BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA

BRA

Inequality, Responsibility, Restart, Hope Inequality, Collectivity, Responsibility, Expectation Inequality, Responsibility, Expectation, Hope Collectivity, Politics, Responsibility, Hope Challenges, Collectivity, Politics, Technology Helplessness, Politics, Urban, Expectation, Uncertainty, Collectivity, Expectation, Hope Uncertainty, Politics, Technology, Regression Regression, Losses, Collectivity, Resposanbility Urban, Expectation, Collectivity, Routine Inequality, Urban, Nature, Hope Inequality, Collectivity, Urban, Nature Challenges, Uncertainty, Collectivity, Nature Collectivity, Urban, Nature, Adaptation Collectivity, Responsibility, Restart,Hope Nature, Responsibility, Restart,Hope Collectivity,Nature, Responsibility, Regression Urban,Nature, Responsibility,HopeNature,Responsibility, Expectation,Hope Challenges,Technology, Responsibility,ExpectationCollectivity,Nature,Responsibility,Restart,Hope Politics,Expectation,Hope Routine,Inequality,Collectivity,Nature,Responsibility Politics,Nature,Responsibility Collectivity,Collectivity,Technology,Urban,Adaptation Nature,Adaptation,ExpectationChallenges,Collectivity,Nature,Responsibility,Hope Politics,Nature,ResponsibilityChallenges,Politics,Technology,Urban,Adaptation Inequality,Politics,Urban Isolation,Urban,Nature,Responsibility,Adaptation Challenges,Responsibility,Expectation,Restart Technology,Urban,Hope Challenges,Challenges,Uncertainty,Urban,Expectation Urban,Adaptation,Restart Challenges,Challenges,Technology,Urban,Responsibility

TOMORROW ANEW 23

HIATUS INTERVIEW 5 E 6 LOCUS INTERVIEW 7 E 8 CARE PHOTOGRAPHY ESSAY 20 April 2020 29 May 2020 29 May 2020 7 Setember 2020 4 April 2020 19 April 2020 02 June 02 June 2022 16 June 2020 16 June 2020 25 May 2020 25 May 2020 04 May 2020 30 March 2022 18 May 2020 17 May 2020 16 May 2020 07 April 2022 01 July 2020 02 June 2020 14 April 2022 31 March 2020 14 July 2022 14 July 2022 11 March 2022 11 March 2022 03April 2022 31July 2020 01April 2022 16 June 202016May2020 16May 2020 17June 2020 17June 2020 03June 202229May202029May202003May202003May202011August20200404April2022 April20220226April2020 June20200414May2020 May20202429June2020 05March2020 May202027May2020 17January2021 3020April2020 June20201515June2020 June2020 2930May2020 March 2020 31 March 2022 05April 2022 05 April 2022 21 July 2020 31 April 2022 15 May 2022 21 March 2022 26 June 2022 14 July 2022 23 February 2022 29 May 2022 12 April 2022 27 September 2020 04 May 2020 01 June 2020 27 May 2020 27 May 2020 29 October 2020 26April2020 26April2020 09October2020 30April2022 1515June2020 June2020 15June2020 31August202028June2020 14July202025June202003April202216June202011June202004June202007Aug202029May2020 05March202228May20202020May2020 May202025May202017May202008May202007May202016May 2020 16May 2020 03May 2020 23 March 2022 01 May 2020 27 April 2020 13 July 2022 26 May 2020 25 April 2020 14 March 2022 04 April 2022 Neeraj Bhatia Malkit Shoshan Diana Flatto Manuel Blanco-Ons Fernández Barbara Fonseca Gustavo Hadba Cripta Djan Iker Gil Pedro Zylbersztajn recall Ascânio Seleme Karla Mendes Vitória Hadba recall Linda Chavers Murdoch Rawson Ana Fontes Marcelo de Troi e Wagner Quintilio Isabela Fonseca Pedro Brito Luis Erlanger Admir Masic Adèle Naudé Santos Bruno Carvalho recall Renata Minerbo Osborne Macharia Martim MoultonLeticiaMariaManuelaMoog Cotrimda Cunha recallCarlosSaul ZebulunPedroSidneyChalhoub GadanhoMarielArielKozlowski BarbararecallCollardArias VeigaNaomiMarinaGrinover DavyIsaacMichaelBatty DanielKarabtchevsky Corsi AlejandroChristianaFigueresdeMiguelSolano

Klabin RicardoTrevisan CauêPhilipYang

CarlosTimerman Nobre recall Gustavo Neiva Amanda Palma Helena Singer Shirley Krenak Beth Kozlowski Ricardo Bayão Marcia Kambeba Sônia Guajajara Beto Veríssimo Mohsen Mostafavi Dado Villa-Lobos Luis Nobrega Adam Haar Horowitz Heloisa Escudeiro JeremyBailey

ClaudioDomênico TinaCorreia recall MairaGenovese DeboraMartini IgorLima MarkBryan LucioSalvatore IsabellaMayworm SergioBranco recall EimeTobariHigiaIkeda

Seamus

GuilhermeAlves

LúciaGuimarãesMarkoJorisKomen SimoneBrajovic

NataliarecallCapillé

AnnaMariaMoogRodrigues

MarcosFrazão AntoniodeSallesGuerraLage CharlesSilvaOntxaMeinhako

O'Farrell

MariMel Ostermann JulieMichiels

Oliveira Marcelo Maia Rosa Gabriel Carvalho Gabriel Kozlowski

Latorraca José Benedito Huni Kui Rita Braune Guedes Adriana Lucena Isabella Simões RafaelMarengoniFernandaFerreiraPaulaBraun João Anzanello Carrascoza Delfim Martins Luciana Whitaker Juliana Lima Marcos Amend Rafael Costa Ricardo Teles Rogério Reis Sérgio Ranalli Introversion, Inequality, Collectivity, Urban Challenges, Collectivity, Responsibility, Restart Uncertainty, Losses, Collectivity, Hope Challenges, Helplessness, Introversion, Responsibility, Expectation, Restart Inequality, Politics, Urban, Expectation Inequality, Responsibility, Expectation, Hope Helplessness, Inequality,

Regression Challenges, Uncertainty,

TerezaC.Mc Courtney MiguelDarcyde

Ney

Responsibility,

Inequality, Responsibility

Politics, Nature, Responsibility, Hope Challenges, Politics, Nature, Responsibility, Challenges, Nature, Responsibility, Restart Collectivity, Politics, Responsibility, Expectation Challenges, Collectivity, Nature, Responsibility Collectivity, Nature, Responsibility, Hope Uncertainty, Nature, Responsibility, Hope Challenges, Collectivity, Nature, Responsibility Politics, Technology, Responsibility, Adaptation Challenges, Uncertainty, Adaptation, Restart Losses, Adaptation, Restart, Hope Isolation, Adaptation, Expectation, Hope Challenges, Inequality, Responsibility, Hope

Challenges, Uncertainty, Adaptation, Expectation

Collectivity, Responsibility, Expectation,Hope

Introversion, Inequality, Collectivity, Urban Challenges, Collectivity, Responsibility, Restart Uncertainty, Losses, Collectivity, Hope Isolation, Introversion, Expectation, Hope Isolation, Uncertainty, Technology, Responsibility Isolation, Collectivity, Responsibility, Hope Isolation, Introversion, Routine, Uncertainty Isolation, Challenges, Responsibility, Expectation Isolation, Routine, Uncertainty, Nostalgia Isolation, Introversion, Routine, Restart Isolation, Collectivity, Technology, Restart Losses, Collectivity, Restart, Hope Challenges, Collectivity, Expectation, Hope Isolation, Routine, Uncertainty, Expectation Isolation, Introversion, Collectivity, Technology Isolation, Routine, Challenges, Collectivity Isolation, Routine, Technology, Responsibility Nostalgia, Expectation, Restart, Hope Isolation, Challenges, Restart, Hope Introversion, Collectivity, Technology, Adaptation Routine, Challenges, Uncertainty, Technology Isolation, Introversion, Uncertainty,Hope Routine,Collectivity, Nostalgia, Adaptation Isolation,Introversion, Collectivity, Adaptation Routine,Collectivity,Politics, Responsibility Isolation,Routine,Inequality,Collectivity Isolation,Introversion,Challenges,UncertaintyHelplessness,Losses,Nostalgia,Restart Isolation,Introversion,Routine,AdaptationIsolation,Introversion,Routine,Adaptation Isolation,Collectivity,Technology,NostalgiaIsolation,Routine,Expectation,RestartIsolation,Collectivity,Adaptation,Hope Isolation,Introversion,Routine,Uncertainty Challenges,Collectivity,Responsibility,HopeCollectivity,Politics,Technollogy,Nature Politics,Responsibility,Regression,Adaptation

Galaz-GarcíaAndrésPassaroMaxGhenisLuiFariasAngelicaWalkerIlanaLipsztein

MartaM.RoyTorrecilla

BeatrizGuimarães

Challenges,Helplessness,Collectivity,Expectation Isolation,Losses,Responsibility,Hope Losses,Inequality,Collectivity,Politics

BartiraVolschan

AnaCristinaGonzálezVèlez

SheilaJasanoff

PinarYoldas

CAN ISR USA SPN USA MEX / USA ARG / BRA USA BRA USA USA USA USA BRA UK UK USA USABRABRABRABRABRABRABRABRABRABRABRASPN ISRBRA BRA BRA BRA IND COL USA BRA BRA BRA USA USA

ZuenirVentura

Challenges,Losses,Collectivity,Responsibility Isolation,Urban,Adaptation,Restart Politics,Responsibility,Expectation,Hope

MauroVentura

JoséRobertodeCastroNeves

DavidBirge

MichaelWaldrep

Challenges,Losses,Inequality,Responsibility

Introversion, Responsibility, Expectation, Restart Inequality, Responsibility, Expectation, Hope Helplessness, Inequality, Responsibility, Regression Responsibility

Challenges, Helplessness, Inequality, Regression Inequality, Politics, Urban, Expectation

Isolation, Introversion, Inequality, Urban

Challenges, Uncertainty, Inequality, Urban

Introversion, Inequality, Collectivity, Restart

Inequality, Responsibility, Restart, Hope

Inequality, Responsibility, Restart, Hope

Isolation, Inequality, Politics, Expectation

Challenges, Uncertainty, Politics, Technology

TábataJoãoCosta Amaral

Mae-lingRoquette-Pinto

BarbaraXhulioBinjaku Graeff

JoséGuilhermeCantorMagnani

AlessandraAurithaTabajara

FernandoHenriqueCardoso

KátiaBandeiradeMelloGerlach

BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA USA UK BRA ARG / USA CAN CAN BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA ARG USA BRA BRA BRA BRA BRA USA BRA BRA BRA USABRB/AUS BRABRA/US BRAUSABRABRAUKRBRA /USA AUSBRABRA BRABRA BRA UAE USA MEX BRA BRA BRA MEX MEX BRA USA IND IND BRA BRA BRA BRA USA BRA BRA BRA BRA

Challenges, Nature, Responsibility, Expectation

Challenges, Politics, Nature, Hope

GHABRA /PHLGHA/PHL

Introversion, Inequality, Collectivity, Politics

Challenges, Collectivity,Politics,Hope Uncertainty, Collectivity, Regression,Hope

Isolation, Inequality, Collectivity, Politics

Collectivity, Politics, Expectation, Hope

Collectivity, Politics, Expectation, Hope

Challenges, Uncertainty, Helplessness, Regression

Challenges, Collectivity,Politics, Expectation

Collectivity,Responsibility,Adaptation,Restart Uncertainty,Losses,Politics,Expectation Collectivity,Nature,Restart,HopeChallenges,Isolation,Introversion,Routine,Uncertainty Isolation,Collectivity,Responsibility,Expectation Inequality,Uncertainty,Politics,Expectation Collectivity,Expectation,HopeIsolation,Collectivity,Responsibility,Expectation,Hope Helplessness,Challenges,Collectivity,Responsibility Technology,Nature,Regression Collectivity,Restart,HopeIsolation,Introversion,Collectivity,Expectation Isolation,Challenges,Uncertainty,LossesCollectivity,Losses,Politics,Collectivity,Hope Urban,Routine,ExpectationChallenges,Helplessness,Politics,Responsibility Isolation,Collectivity,Politics,Technology,Hope Uncertainty,Losses,Politics Collectivity,Politics, Responsibility,AdaptationInequality,Collectivity,Politics, Responsibility

OMORROW ANEW 24

CELL

DEBRIS

HIATUS PHOTOGRAPHY ESSAY 20 April 2020 29 May 2020 29 May 2020 7 Setember 2020 4 April 2020 19 April 2020 19 June 2020 1 June 2020 6 May 2020 18 June 2020 3 June 2020 2 Setember 2020 22 July 2020 27 June 2020 26 June 2020 23 June 2020 31May 2020 31May 2020 27May20202626May2020 May202025May202016May20204May202022May2020 May20202May20201May202211March202029March2020 8March202015June202027April202021May202014July202216July202228July2022 19June2020 1010May2020 May2020 14June2020 04June2020 01May2020 21 June 2020 26April2020 07August 2020 16 June 2020 15 June 2020 30 June 2020 20 June 2020 06 June 2020 26 May 2020 16 May 2020 16 May 2020 16 May 2020 11 May 2020 11 May 2020 11 May 2020 1 May 2020 1 May 2020 21 May 2020 25April 20202727April2020 April2020 07July2020 07July2020 07July2020 07July2020 28May2020 2928May2020 April202227May2022 0527May2022 April2020 0604March2022 March20222215March2022 June202026June20203030May2020 May202030May20201506May2020 May202021June 2020 05June 20222929May2020 May202008May 202030August 2020 15 June 2020 02July 2020 16 October 2020 13 June 2020 03 August 2020 06 June 2020 29 March 2022 11 May 2020 06 July 2020 26 May 2020 02 June 2022 02 June 2022 16 June 2020 16 June 2020 25 May 2020 25 May 2020 04 May 2020 30 March 2022 18 May 2020 17 May 2020 16 May 2020 07 April 2022 July 2020 Neeraj Bhatia Malkit Shoshan Diana Flatto Manuel Blanco-Ons Fernández Joe Jacobson Sergio

INTERVIEW1E2

INTERVIEW3E4

Mary Lapides Shela Melissa Du Pedro Varella Sophie and Andrew Harkness Jane Hall Nazareth Ekmekjian Nicolas Entel Marcela Berrio Beni Barzellai BrunoRodriguesMonicaEisenbergVitorPamplona

SantosMello AnaCristina Downer Takumã Kuikuro TamaraKlink

Gildetedos

LaraCoutinhoMakauMeinhako

NitzanZilberman

LivSoban NataliaCoachman

recall Murilo Ferreira Sonia Esteves Monica Nogueira Victor Orestes Agustin Schang Mary Gao BA Mir Gabriella Vieira de Carvalho Helena Moreira Dias Gisela Zincone Tadeu Fidalgo Daniel Milagres Diego Portas Anne Bogart Pedro Pirim Maria Eduarda Moog Bruno Tavares MarianaMeneguetti Manuela Müller

FernandaAtapuchaWauja AdalbertoGermano Neto

Parsons&Charlesworth

TamaraVaughan&TimothyHofmeier

CarmenVitaSusak Silva

AniLiu

FischerKapisiBárbaraBuril Kamayura

PedroDenisMooney

recall Marcelo Borborema Catarina Flaksman Rosiska Darcyde Oliveira CarolineAdilAly A. Jones Daniel Daou Ana Altberg Daniel Wilkinson Guilherme Wisnik Laura González Fierro recall Olivia Serra Carlos Saldanha Aditya Barve recall Claudia Escarlate Barbara Fonseca Gustavo Hadba Cripta Djan Iker Gil Pedro Zylbersztajn recall Ascânio Seleme Karla Mendes Vitória Hadba Rafael Costa Ricardo Teles Rogério Reis Sérgio Ranalli

Lokko

Nature, Expectation, Restart, Hope Isolation, Technology, Restart, Hope Isolation, Challenges, Inequality, Collectivity Introversion, Politics, Expectation, Restart Collectivity, Technology, Responsibility, Hope Losses, Collectivity, Responsibility, Hope Challenges, Collectivity, Technology, Adaptation Challenges, Collectivity, Politics, Restart Uncertainty, Technology, Adaptation, Hope Isolation, Collectivity, Adaptation, Expectation Uncertainty, Collectivity, Adaptation, Hope Uncertainty, Losses, Inequality, Regression Uncertainty, Helplessness, Restart, Hope Losses, Collectivity, Expectation, Hope Isolation, Collectivity, Nature, Restart Isolation, Collectivity, Expectation, Hope

Inequality, Politics, Adaptation, Expectation

Campaign Call

Tomorrow Anew

Originally written in English

2525

2020

April

Times of crisis are also times to rethink our established ways of living. Although we are individually separated, we can think together as a collective body and act from within our households to help those on the frontlines. Tomorrow Anew invited individuals from all over the world to act on two fronts:

1. Think

Trapped inside our homes, each day is another of the same, where individual living in isolation long for a public one. We recurrently re-live the today with a mix of uneasiness, nostalgia and hope. Tomorrow Anew is a collective cry for tomorrow to come again. However, we do not ask for tomorrow to come as our normal yesterday, mimicking our old habits, our same ways of neglecting people, of doing business, or of disregarding the environment. Tomorrow must come anew, refreshed to inaugurate a new era. And for that, we need to think: we invited amazing minds to answer the question of “what will be different tomorrow” so we may collectively reflect on our future

2. Share

While reclusion might offer a moment of introversion, reflection, and maybe even peace for some, it is a burden for a large segment of the population that lives from end-of-day paychecks, let alone for those who are battling the virus. This crisis should also be a crisis of selfishness, opening new paths of solidarity. Those who can offer a figurative hand to those who are in a more fragile condition. And for that, we must share : we invited friends, family and strangers to donate as they responded to the question so we could help those who need it the most right now

26

Gabriel Kozlowski

Originally written in English

2727

July 2022

Introduction

Tomorrow Anew began as a reaction to a state of crisis. It was one among a constellation of artistic expressions that tried to make sense of what was happening in the world and do something about it. It was conceived out of an urgency to not just sit and observe but, instead, to mobilize people around a common cause. Rather than fully fleshed out and planned to its last details, Tomorrow Anew was the outcome of a gut feeling that forced us to fight inertia and a sense of disbelief that was starting to weigh heavily on everyone as tragic news spilled out day after day in the early months of the pandemic. By then, it was already clear that the toll of the new disease mirrored our social inequalities. True, one might say the disease spared no one, but this is different from saying it flattened structural differences. If anything, the result was the opposite: inequalities worsened, and the hardest impacts were felt in socially vulnerable regions and disenfranchised communities. This represented a segment of the population for whom isolation was not an option, access to fast and individualized health care service was nonexistent, and whose daily survival depended on the income of the previous month. Thus, as the pandemic deepened and uncertainties grew, solidarity among people increased in an effort to minimize the harmful consequences of the inequity that was created. The feeling was that acts of selflessness were sprouting everywhere along with a sense of responsibility, emerging not only from those in a more privileged position to those who were not, but also among those in need. It was as if anyone who could extend a hand to their fellow neighbor would do it if necessary. And so did we. The gravity of the situation compelled us to think about ways to expand our possibilities for providing help. How could we do more than the little we could do individually, so small acts could build up to something bigger? Or, more pragmatically, how could we create a channel through which those who did not know how to help or had no time to do so could find an easy and reliable way to contribute to alleviating the hardship of others?

The first drive of Tomorrow Anew was its philanthropic ethos, gathering resources—no matter how big or small—to help address a situation that was escalating quickly and becoming more critical as time went by. Aware of the network we had, we knew a fundraiser could be a viable path, but we also realized that, in order to succeed in garnering support, we had to establish trust, clearly communicate our dedication, provide transparency, and make it appealing. Thus, we set out to understand how to make donations work legally, transactionally and in terms of user experience. We reached out to lawyers, economists, directors of nonprofits, web developers, translators, and marketing

28

professionals for advice, and this way we established the initial partnerships that built the foundations of the campaign; every single one of them offering their time and experience without asking anything back. A large component of this initial phase was finding the right NGOs to work with that were already committed to the Covid-19 cause and that, between them, could have a geographical reach to offer multiple possibilities of assistance in different places around the globe. We joined forces with NGOs that were already actively responding to the current crisis, covering the US, Kenya, and Brazil, in different regions and capacities. They had been selected because of their seriousness, transparency, efficiency and scope, while acting like redistribution channels. Donations would first go to them, from where they entered the targeted communities. Thus, our initiative was set to redirect donations to the indigenous peoples of the Xingu and to families living in precarious conditions in slums of São Paulo (in partnership with Instituto Bei); to quilombola and riverine communities in the Amazon (in partnership with Brazil Foundation and Conservation International – Brazil); and to families hit hard by the pandemic and the unleashed economic crisis in the US and in Kenya (in partnership with GiveDirectly). Our campaign was possible because of them: for the beautiful work they were doing on the ground and due to the trust these large institutions placed in us, i.e. a couple of individuals without any charity structure in place or previous knowledge in philanthropy. Side-by-side, Tomorrow Anew moved from design into action, becoming a vehicle to connect new donors to people in need.

If gathering donations was a response to the present situation, one that focused on the immediate and urgent needs of those in need of support and not afterwards, we were convinced that, as a global society, we would come out of this challenge stronger if we also took steps to secure our futures. Not only acting through doing but also acting through thinking. Being able to imagine what tomorrow might hold, where it could be taken, or what we wanted it to be was necessary to avoid missing an opportunity of converting disintegration into evolution. The need was to fight the inertia of sticking to a form of presentism and problem-solving mode only while losing sight of a broader perspective. Thinking, far from a passive act, becomes an active, political stance that extends in time. Through thinking, we can extract lessons from the past, from what brought us to such a point of collapse, so as to re-channel them forward, preempting the future of similar mistakes. We can reject the many facets of pragmatism, utilitarianism, economicism and conformism and accept to give room to innovation, imagination, daydreaming and utopia. The same way that the idea of the present is something we have socially constructed rather than

29

being a natural, given, or preordained concept, so too should the future be. But the future also takes its form from a given present, some would argue, more sober than idealized, a predetermined extension of our current certainties. This view suggests a tomorrow that replicates the path that led to today. The future is not different from what the present once was: a past promise of brighter days, failed due to the very systems of politics, capital accumulation, social exploitation and disregard of nature that we see invariably continuing into the future. In fact, reconciling the two views is a negotiation between optimism and pessimism. Perhaps it is a matter of understanding what triggers real change. Is it a matter of scale: how much is enough for a wake-up call? Or, is it perhaps a matter of method, a search for the processes that may occasion rupture? Regardless of the direction, it became important to us to delve into the relationship between this dystopic moment and our potential futures. We sought to use the multiple kinds of resources and energy we were mobilizing to build, in parallel to the fundraising efforts, a platform where thoughts about our future could be collected and shared. This was a platform conceived of as an incentive for people to reflect collectively, to take time to stop, and then think. Thus, we asked them: “ What will be different tomorrow? ” And their answers became this book.

This is a book about envisioned futures from the perspective of a derailed present. We reached out to a wide range of people, from multiple backgrounds, genders, races, ethnicities and nationalities. We asked for reflections from professionals in the arts, design, photography, architecture, literature, journalism, cinema, sociology, psychology, healthcare, economics, entrepreneurship, law, politics, climate activism and more. From a former president to a housewife. We heard from intellectuals we admire and individuals we do not know as a result of both the direct invitations we sent and the campaign’s organic dissemination due to the open character of its on-line presence, expanding answers beyond our initial circle. As there was no imposed framework for the individual reflections, they came in multiple formats and lengths. From a paragraph to an essay to a movie script. Some reflected on the future they saw as needed, others on the future they wanted, and others yet on the future they thought inevitable. Some thought there was no future. In hindsight, we see the answers as a balancing act between hope and disillusionment and, generally speaking, the feeling is that they tended to get grimmer the later they were written. Despite the severe atmosphere of the moment and the shared anguish, it is noticeable that in the first phase of the pandemic there was a hint of excitement, even if in reverse: a sense that from the dusk of doom a new dawn would arise. This change in tone according to the period of the year compelled us to

30

take advantage of the timeframe of the book’s production process to deepen its content and gather updated reflections from some individuals who had already submitted answers a year before, like a recall. Reading their reflections before and after the pandemic offers a fascinating perspective on its development.

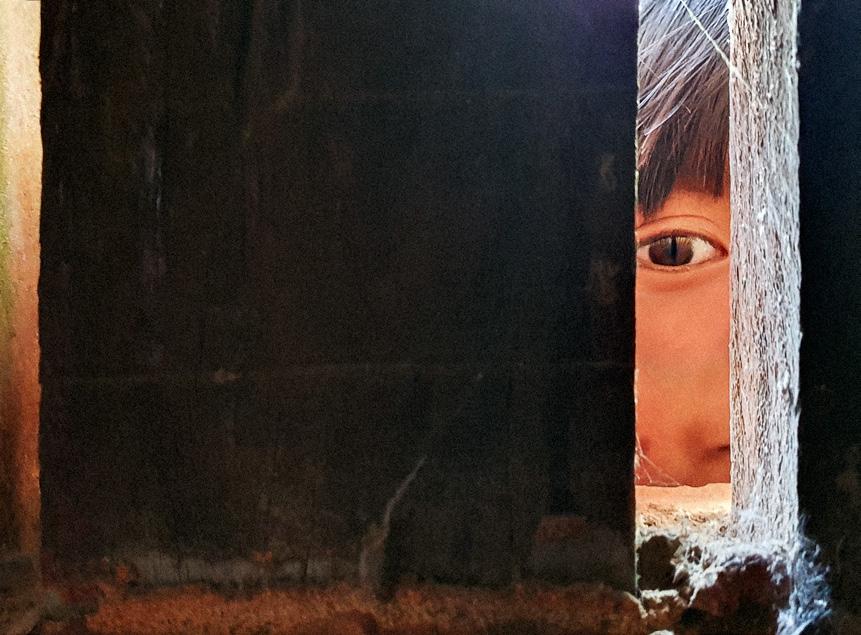

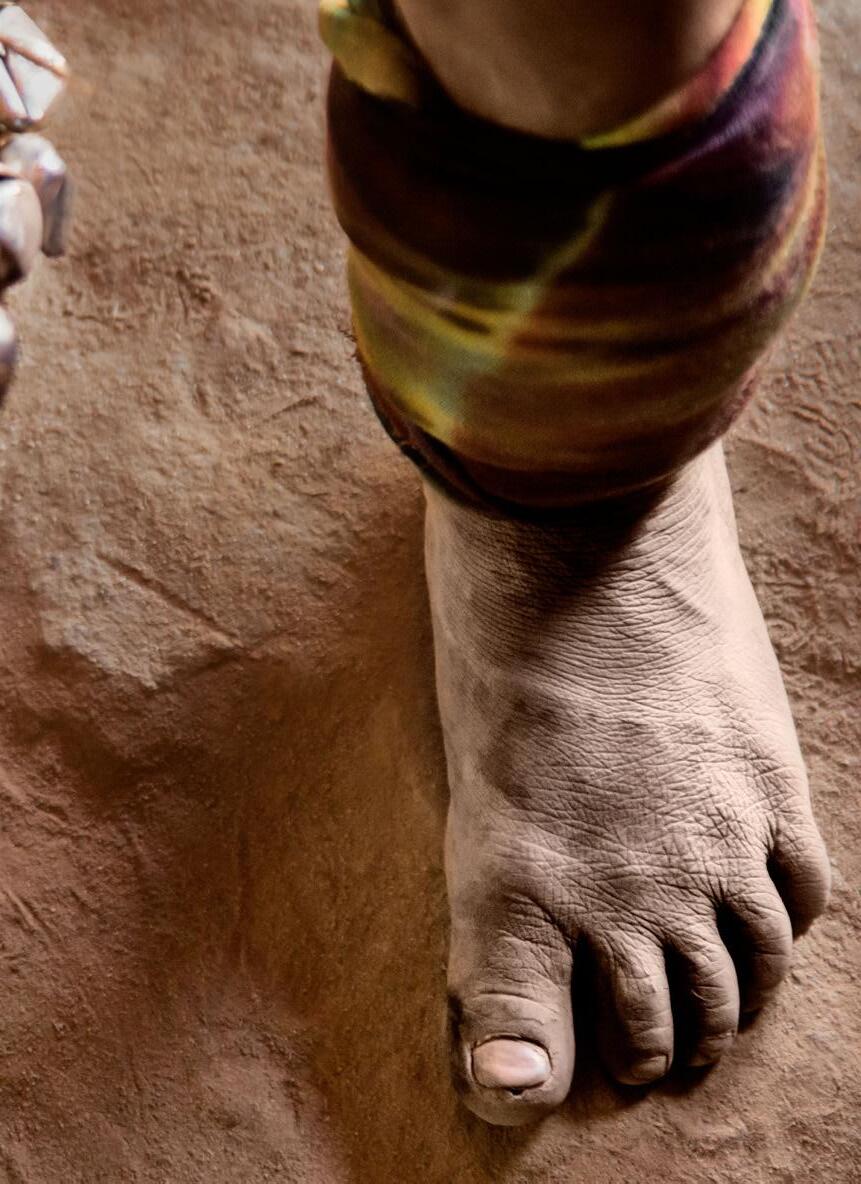

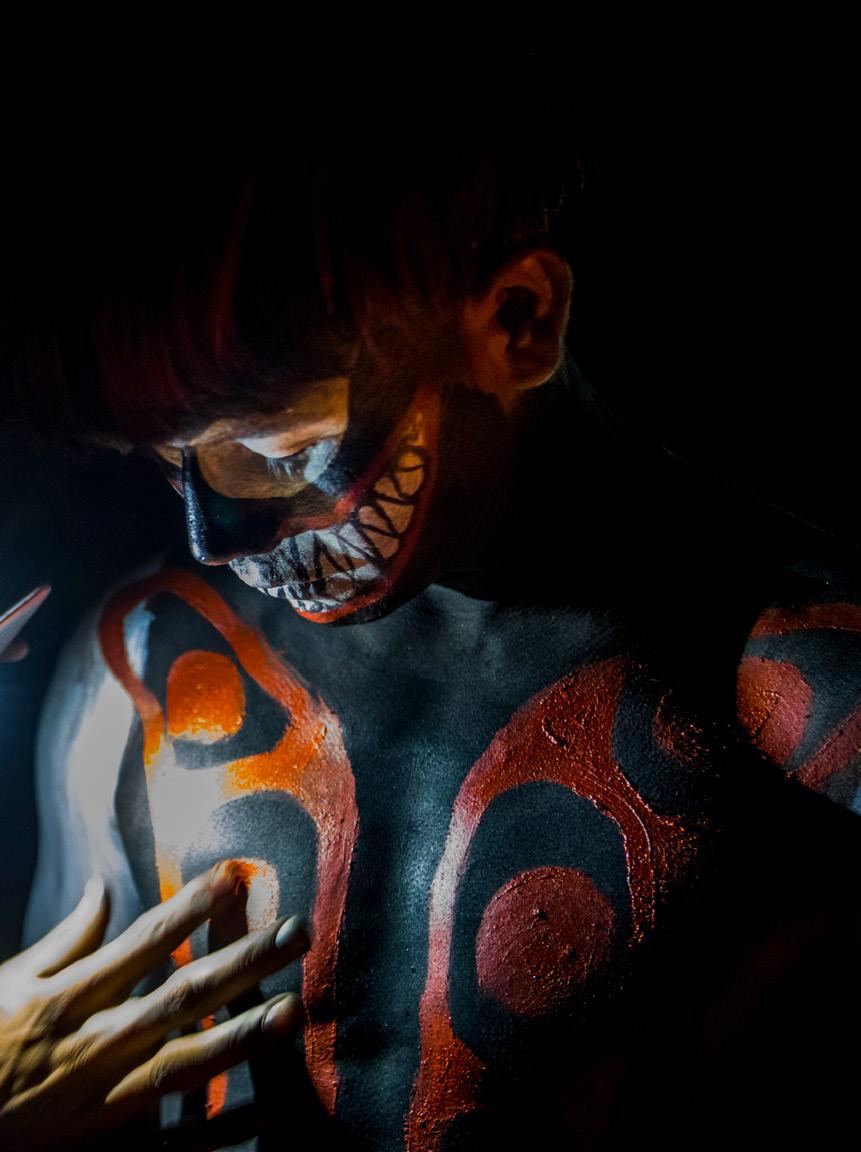

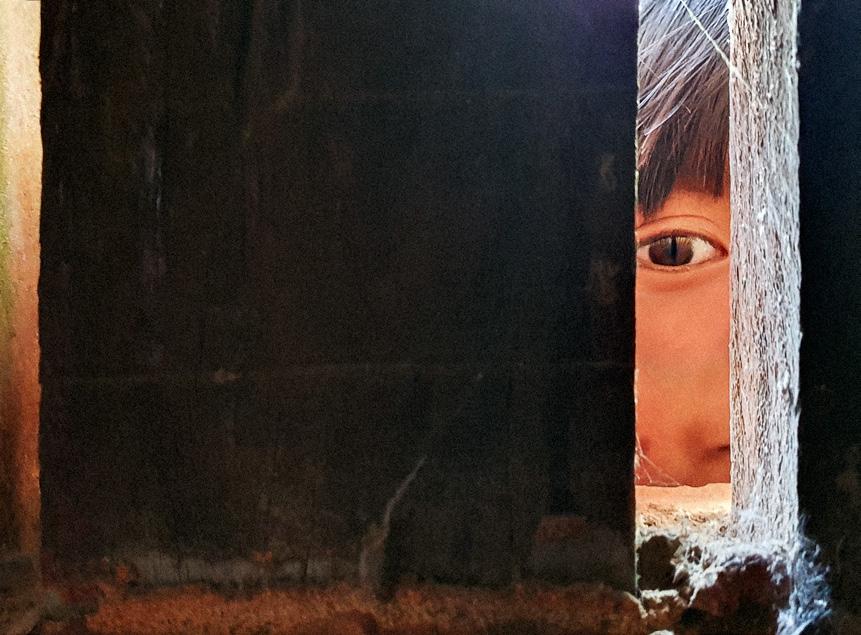

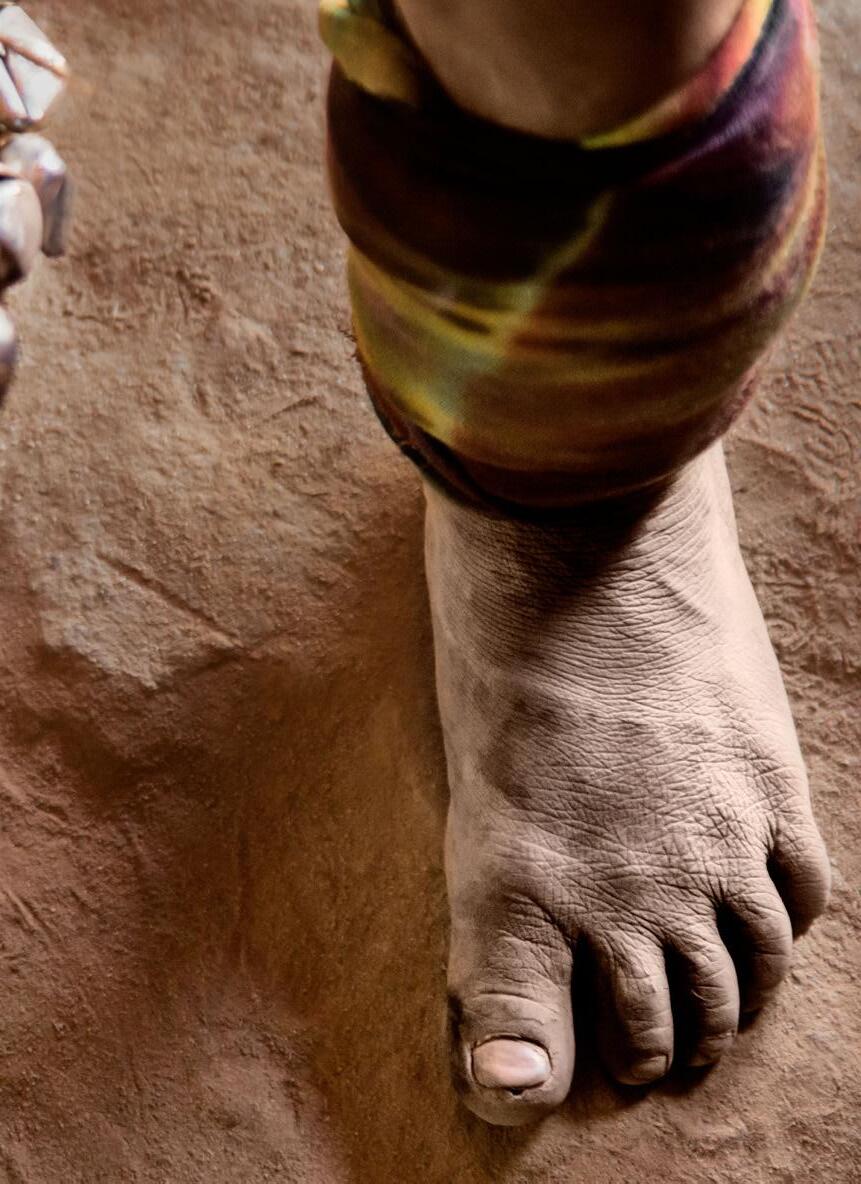

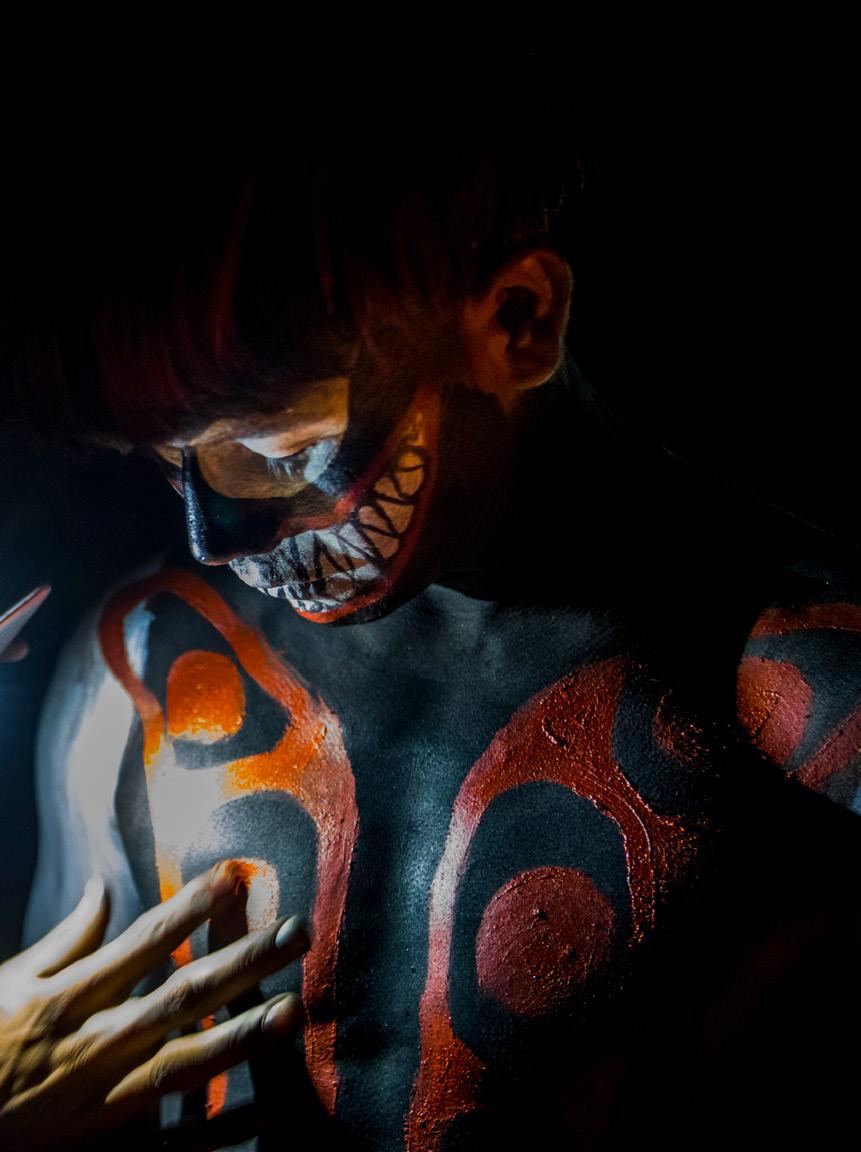

Throughout production, we also explored another type of dialogue through the medium of interviews. We selected eight outstanding thinkers for whom the pandemic had become an extra drive to expand their practices around social, political and environmental rights. They deal with questions pertaining to universal access to housing (Carmen Silva), the role of design in the provision of an affordable and equitable city (Adele Santos), the defense of indigenous territories (Sonia Guajajara), women’s rights and gender equality (Ana Cristina González Vélez), transnational solutions to the refugee crisis (Admir Masic), rights to sovereignty and peace in Ukraine (Vita Susak), protection of the Amazon forest and its inhabitants (Beto Veríssimo), and the ethics of scientific development as it intersects with politics (Sheila Jasanoff). Furthermore, to this collection of eight verbal reflections, we added ten visual essays. These were generous gifts from renowned Brazilian photographers who have been photographing indigenous tribes for decades. Concluding the book, the collection of about sixty photographs depicts the beauty of Brazil’s native peoples, a group for whom the pandemic has been particularly destructive due to their low immunity to viruses, collective traditional ways of living, limited access to health services and hospitals, and current governmental inaction. These photos are an homage to their cultures that have for so long persevered against adverse conditions, such as the one built around the current administration, which has mobilized everything in its power to dismantle such communities and cede their lands to agribusiness and resource extraction activities. By depicting multiple aspects of indigenous peoples’ life, culture and arts, these photographers help raise awareness about the urgency of valuing and protecting Brazil’s original inhabitants, who, at the end of the day, are the true owners of this land and the most important protectors of its forests. Altogether, between reflections, recalls, essays, interviews and photographs, the book depicts the thoughts of 200 people, written in two batches between April and October 2020, and March and July of 2022, building a panorama of the ways we have dealt with the crisis.

The book organizes this written material into 5 sections, which also reflect the structure of its chapters. They are: Cell, Hiatus, Debris, Locus and Care. Each chapter’s beginning offers a deeper elaboration on these words, trying to convey a set of positions and feelings that make sense when read together. Siding more with the poetic than with the utilitarian, they represent a loose attempt at

31

categorization and clustering designed to emphasize some areas of discussion while also facilitating the reader’s access to the different themes present in the publication. The purpose was not to build a rigid framework that precisely corresponded to the content of each individual reflection; instead, it was an exercise to help identify and point to intersections that can be perceived when a group of texts is viewed collectively. This way, the sections should rather be understood as a retroactive effort on extracting some of the main concerns that cut across the texts while finding similarities and differences between them. The sections were then ordered as to subtly suggest a progression of feelings and postures towards the pandemic, ranging from disbelief to hope and renewal. Naturally, an attempt at categorization for something that was not originally designed to fit into categories risks oversimplifying or diluting the nuances of the arguments. Our response to that was to first embrace the instability of the sections’ labels and actively work to blur the boundaries between them by positioning texts that talk across sections when it came to the closing and opening of each chapter. To reinforce this blurring, we also used the interviews as transition moments between the chapters. Displayed in pairs, they function as thematic markers leading the conversation from certain themes into others. Second, we created a system of keywords that offered more depth to the classification while the same time providing the reader with a roadmap to find in the book the reflections that spoke to their interests. By following the keywords, each reader can create his or her own paths for accessing the content and navigating through the multiple discussions. One may decide, for example, to read only the texts tagged as Nature, while someone else may prefer to explore Routine, Politics and Nostalgia and see how these topics have been addressed by our writers. Equally valid would be to ignore the keywords and sections altogether and read the texts chronologically. All in all, the book offers multiple discussion paths, including, we believe, many we have not foreseen. Another component that is important to emphasize when introducing this publication is that the initial campaign was bigger in scope than the actual book. Not everything from there made it here. A couple of examples include the material of the crowdfunding campaign launched by Instituto BEI and Tide Setubal simultaneously to our campaign and with whom we joined forces; the artwork auction we created under the name “Mapping Brazil” to increase our fundraising capacity by selling the maps myself and my fellow co-curators created for the Brazilian pavilion at the 2018 Venice Biennale; the event we prepared for the ringing of the New York Stock Exchange closing bell to raise awareness for our campaign; the countless social media content, pitch decks and marketing materials; and, most importantly, the gorgeous digital animation that Turkish media artist Refik Anadol crafted specifically for Tomorrow

32

Anew depicting the spatial evolution of Covid-19 cases throughout the world. The work entitled New Gravity of the Earth builds a 3D visualization that draws data from John Hopkins University and Healthmap.org, mapping the 2.5 million confirmed cases as of June 2020. The data was processed to make legible the cumulative sum of infections throughout time, filtered by continent, country, province and city, while encouraging a more comprehensive understanding of the current moment and the imagination of a post-pandemic world, where global interconnections will be instrumental for our collective healing process. Refik’s generosity in producing this piece and helping expand the campaign makes any note of appreciation fall short next to it; we can only express our gratitude for this collaboration. The reason it was not included in the book is simply due to the different nature of its content in comparison to the ones we chose to prioritize: raw texts and visuals of indigenous peoples. The New Gravity of the World should be experienced in its original version, hence the video can be seen on-line at the locations listed in the footnote1. All these components, succinctly listed here, were as integral parts of the campaign as the content that ended up in the making of the book. They were equally important for building momentum to our fundraising efforts while also giving them legitimacy, traction, reach and, ultimately, success.

To conclude, this book also acts as the end point of a long enterprise. Both symbolically and practically. Practically, because it is a way to show ourselves accountable to all the trust that has been deposited in us. As it consolidates the content produced by hundreds of people in a single place, it concomitantly makes such content concrete, allowing it to endure beyond the pandemic years. In this sense, the book can be seen as an artifact, a small glimpse into a particular time. Additionally, it provides a section explicitly labeled Accountability, where it offers an overview of the path the donations took until reaching their recipients. On the symbolic side, the book marks a completion. It is a culmination of events, time, resources and the good will many people put into making a philanthropic drive an actual source of impact.

All this considered, the book is an opportunity to thank genuinely and publicly everyone who participated in any capacity throughout the different phases of the initiative. To every single contributor who donated their time and knowledge to put Tomorrow Anew together; to all who embraced the prompt and donated their ideas in the form of written reflections and conversations; to

Studio Refik Anadol: https://refikanadol.com. New Gravity of the Earth: https://vimeo.com/446199466.

33

every generous person who donated money to the campaign, as well as those who gracefully received the donations; and to all our partners and sponsors we could not be more grateful. Although we have listed their names in the front credits, here we pay an additional homage to our closest partners: the Brazil Foundation, under the leadership of Rebecca Tavares; the Instituto BEI, headed up by Tomas Alvim and Marisa Moreira Salles; the Harvard David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, with its executive director of the Brazil Office Maria Helena Monteiro and program manager Tiago Genoveze; and our publisher Editora Afluente, under the creative and resourceful figure of Julius Wiedemann. Finally, we extend the thank-you note to the readers, who, by acquiring this publication, are not only valuing and celebrating this work, but also providing proceeds to the inhabitants of the Amazon region and the Association for the Indigenous Territories of the Xingu (ATIX).

We thank you all from the bottom of our hearts and sincerely wish that the compilation of ideas presented here sparks a sense of empathy, curiosity and responsibility towards the building of our collective tomorrow.

Gabriel Kozlowski Campaign Author & Book Editor Belém, Brazil. July, 2022

34

A cell is an interior space. It is both a space in which one finds herself and a unit within a broader system. It describes a state of enclosure, an enclave. The cell mirrors a territory. It detaches so it can look inside. It may protect or alienate. “To be in a cell means” to be contained within limits, be they physical or mental. These are limits that divide and isolate. They are membranes, skins, envelopes, covers, wrappers, shells, cuirasses, but also ideas and beliefs. At the same time the cell locks down, it frees up: the prison and the egg.

A cell is a retreat where one recreates oneself and, in return, recreates the world. A cell implies a continuous transformation of both medium and subject. It is reciprocal. There is no such thing as a subject inserted in a medium without this medium being inserted in the subject. Being a cell, one unwillingly constructs the environment in which she will need to live: one constructs its own possibility of existence. Like the chicken and the egg, but with the caveat that we know the egg came first. The egg found the chicken the same way the cell found the subject. The cell only uses the subject so it can build the environment where other subjects can exist. A cell allows one to live, but it is exactly living that one dies. So, the cell is the biggest sacrifice of the subject the same way “the egg is the biggest sacrifice of the chicken. It is the cross the chicken carries in life.” 1 This way, egg and cell are the perfect manifestations of universality. They contain the entire cosmos within themselves. Therefore, like the egg, the cell came first. No surprise it inaugurated the pandemic.

3535

CELL / Responses 01 to 35

1. Lispector, Clarice. "O ovo e a Galinha" [The Egg and the Chicken]. In Complete Stories, edited by Benjamin Moser, 306. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Rocco, 2016.