12 minute read

Losing Nothing: Arakawa and Madeline Gins

The cover of the Artnews of May 1980 shows a smiling face, with superintelligent eyes, under a somewhat unruly crop of dark hair. In a black sweater covering a blue workman’s shirt, collar just showing, the artist Arakawa, known only by his last name, points a pencil toward the viewer, his other hand pressing down on a messy stack of papers. Behind him in the photograph, by Hans Namuth, is one of his singular paintings.

The opening photograph in the feature shows a young Madeline Gins, Arakawa’s wife and creative partner—a native New Yorker who had studied Asian philosophy and physics at Barnard College and painting at Brooklyn Museum Art School, and who knew Chinese and Japanese poetry—looking confidently out, and standing with her hand just touching her seated husband’s neck, as he looks sideways at us.

Presented with two pictures, we find ourselves dealing with several layers of perception. A dominant feeling of potential, of ongoing work, has already been staged. Namuth’s single and double portraits correspond, as the single and double works of Arakawa and Arakawa/Gins correspond, and as the real thrust of all their work is about developing a flexibility of thought. Their work, which was their life, always concerned perception in all its various modes and possibilities.

Untitled (Stolen), 1969, oil and graphite on canvas, 72 × 48 inches (182.9 × 121.9 cm)

Art by Arakawa; Photo by Allen Phillips

The Tale

Somehow, as those of us who write biographies know all too well, it is often easier to speak of the works than of the creators. The works converse differently, of course, with each of us, in music and in art and in writing, and yet we tend—rightly, I think—to trust our own reactions. But since, in the lives of the artists, there are absolute facts, we would like to get them right and, insofar as possible, give them out that way also.

Born in 1936 in Nagoya, Arakawa was evacuated, at the age of seven, with 200 other children, to a Buddhist monastery in the mountains, where they had to forage for their food. This was at the height of Japan’s entanglement in World War II. When he came down, almost blind and deaf from malnutrition, he was “adopted” for three years by neighbors, a doctor and his wife, for a sort of therapeutic environment. He became the doctor’s assistant and said “there had been so much death” that he was not frightened by it. He studied biology, biochemistry, and classical painting in school. When he was seventeen, tubercular spots were found on his lungs; he later learned that this was a misdiagnosis but at the time it led him to exercise a lot, not only his body but his voice, singing arias from Italian operas. Encouraged to attend classes in mathematics and medicine at the University of Tokyo, he instead studied drawing at the Musashino Art University before dropping out and engaging private tutors.

Even at this young age, Arakawa was fascinated by Edgar Allan Poe’s Eureka and obsessed with the work of Leonardo da Vinci. He was, and would remain, good at obsessions, one of our mutually favorite topics.

The influence of European modernism was still dominant in Japan, and Arakawa’s use of materials unusual in that context, demonstrated in works he showed in the annual Yomiuri Independent Exhibition (a major event for postwar Japanese avant-garde art) in 1957 and again in 1958, made him scandalous by the age of twenty. By 1960 he was a member of Tokyo’s short-lived Neo- Dadaism Organizers group, a precursor to the country’s Neo-Dada movement. He saw art as political, even staging a Luis Buñuel-like act, trapping dozens of persons in darkness on a balcony, while hundreds more were clamoring loudly outside the venue because they couldn’t get in. His sculptures were extremely physical: formed from wet cement, gouged and incised, sometimes with found machine parts embedded in their surface, wrapped in cotton, and placed in closed, satin-lined boxes, quite like coffins and quite like the boxes of Joseph Cornell, which he and I were to discuss at length.

Texture of Time, 1977, acrylic, pencil, and art marker on canvas, 66 × 100 inches (167.64 × 254 cm)

Arakawa

Unsurprisingly, Dada and Surrealism, too, found their way into Arakawa’s work. A sketchbook drawing of 1963 recalls Lautréamont’s famous line from Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) about “the chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table,” the genesis of a work by Man Ray. Arakawa makes the overhanging lamp shine full-scale on the sewing table, as if a medical procedure—not just an artistic one— were eminent.

In 1960, Arakawa participated in a demonstration against American military bases in Japan, and the newspapers said he had started it. As he would recall, “The poet Shuzo Takiguchi said I had to leave Japan at once, [and] gave me a bit of money and a passport.” So Arakawa arrived in New York in 1961, with $14 in his pocket, and phoned Marcel Duchamp, whose number he somehow had, to ask why Marcel had not phoned him! Duchamp asked (I am telling the tale as Arakawa told it to me) how much money he had, and where he was, and then said he would meet him halfway. They had for lunch what Duchamp always had: spaghetti with no sauce and a half-glass of white wine. Never doubt how a single meal can change the course of one’s life, or, in this case, of art history.

Arakawa crossed paths with many other central figures in the downtown New York of the time. For example, he met John Cage and also came to know Yoko Ono, whose loft on Chambers Street would become his home and studio. He met Madeline in 1962, while both were studying at the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

Some three years after arriving in the United States, Arakawa was already having his first solo gallery show, Arakawa: Dieagrams, at the Dwan Gallery in Los Angeles. By 1966, he and Madeline had married and moved into 124 West Houston Street, the Greenwich Village townhouse where all of their future experiments in living, painting, writing, and thinking would take place. (Also where Bob Dylan had his practice studio on the ground floor in the late 1960s and early ’70s.)

Hard or Soft No.3, 1969, oil, acrylic, and art marker on canvas, 95 ½ × 65 inches (242.6 × 165.1 cm)

Arakawa

If Possible . . .

To borrow from the poet Charles Bernstein, let’s say that Arakawa’s multidiscursive and multimedia works are always in a “tentative relationship with their surroundings” and therefore “part of a collective project,” as opposed to participating in any sort of “romantic exceptionalism.” Hence we can associate him with artists and poets including Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Huebler, Mel Bochner, Cy Twombly, and Hannah Weiner, and can address his affinity with Richard Foreman, Ron Silliman, Joseph Kosuth, Eva Hesse, Leslie Scalapino, and the great lineage stretching from Stéphane Mallarmé through Duchamp, Cage, William Carlos Williams, and Charles Olson.

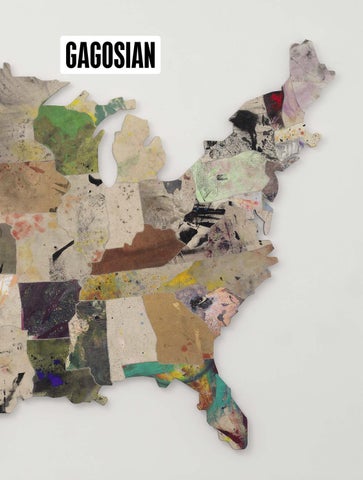

Like this roster of visionaries, Arakawa always engaged with the social, with its “participants,” and with a large matrix of other minds. Take for example a hilarious but nonetheless meaningful event that crystallizes so much of what is meant by “participatory engagement”: one of Arakawa’s works, with the inscription “If possible, steal any one of these drawings including this sentence,” was stolen from Virginia Dwan’s New York gallery in 1969, and the five culprits, graduate students at Rutgers University, wired Arakawa “Work completed.” He asked them to donate the canvas to a “public institution,” a gift the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford accepted, delighting the painter; “That a painting, and particularly a conceptual painting, should generate such passion is beautiful.”

Tubes, 1965, oil, acrylic, and art marker on canvas, 51 × 69 inches (129.5 × 175.3 cm)

Arakawa

In all of the work, much is about ambiguity, treasured for itself. This extended to Arakawa’s delight in the double senses of words such as the verb cleave, which can indicate both sundering apart and joining together. The notion of, and expression of, the reversible prefigures the architectural workings that would come to obsess Arakawa and Madeline from the 1990s through the rest of their lives. The Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa) (2008), out in East Hampton, New York, operates with the “tentative” on a full-body, immersive/encompassing scale. The diagrammatic paintings operate on the visual-mental-perceptual level in much the same way: take the visual/verbal map From Mechanism of Meaning (1971), with its “balloons” radiating out, like the speech bubbles in comic books, from a field of crisscrossing lines in the center, inviting multiple ways of looking at a lemon. The work stretches the idea of definition, amusingly and convincingly, since all of these creative possibilities are contingent on the existence of a double helix, as the underlying text says. All those possibilities radiate out from a creative center, like a source of energy, and we think of Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs and of all the ways in which Arakawa and Duchamp crisscross in their own energies.

Here, too, the ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein come into play, specifically the duck/rabbit illusion discussed in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations of 1953. The conscious mind cannot manage both perceptions—seeing the duck and seeing the rabbit—simultaneously, so we have to hold two possibilities in mind at the same time, making it stretch. In this perceptual breakdown, where visual and linguistic programming is short-circuited, the subject can move, leap, and fall into new frontiers of thought. When assumptions are undone, diverted, or cracked, light is invited in.

From the early paintings on to the late architectural investigations, the work integrates information from all manner of scientists, including biochemists and psychologists and physicists and creative artists, mirroring—as in the mirror writing practiced by Arakawa—just the kind of gatherings that Arakawa and Madeline hosted at 124 West Houston. Arakawa would often allude to the plays of Samuel Beckett, and, more often still, to James J. Gibson’s book The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. All of us who were friends of Arakawa’s recall those allusions, so important for his own works. At their place, there would be discussions of Heidegger, Kant, and above all, Wittgenstein and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Gathered there might be Geoff Hendricks and Alison Knowles of the Fluxus group, the feminist writer Kate Millett, the historian of science Stephen Jay Gould, the composer La Monte Young, the artists Don Byrd, Vito Acconci, Öyvind Fahlström, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Isamu Noguchi, and Joseph Beuys (especially important for Arakawa), the poet David Shapiro, the publisher George Quasha, the Greek Surrealist Nicolas Calas, and groups of writers on every available subject, including the postmodern philosopher and fabulist Italo Calvino, the writer and art critic Edward Casey, and the delightfully bizarre poet Edward James, at whose home in West Dean, in the South of England, a frequent guest was Tilly Losch, the dancer and heroine of Joseph Cornell. Her footsteps were traced on the stairs at West Dean, I remember, from several gatherings there.

Arakawa’s and Madeline’s community continued to expand in France. It would grow to include the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, a thinker on time and technology and the author of The Postmodern Condition (1979), who wrote on Arakawa’s art and whose technological, informational, and learning-exchange research had affinities with the artist’s thought. Another member of the circle was Gilles Deleuze, who often discussed with Arakawa his work with Félix Guattari on the rhizome and then, crucially, on the notion of the fold (le pli) in relation to Leibniz and the baroque—so essential for Surrealism. And the philosopher and writer Jean-Michel Rabaté, editor and author of books on Beckett, Ezra Pound, modernism, literature, and psychoanalysis, joined in to write the preface for the French translation of Madeline’s book about Arakawa and Helen Keller.

Blank Lines or Topological Bathing, 1980– 81, acrylic, art marker, and graphite on canvas, in four parts, 100 × 272 inches (254 × 690.9 cm)

Arakawa

The philosopher Arthur Danto—a close friend, and responsible for Arakawa’s brief film on the bicycle wheel, in honor of Duchamp—spoke of the artist in his Transfiguration of the Commonplace (1981):

"When contemporary artists use words in their paintings, a complex decision as to their status always has to be made because words are at once vehicles of meaning and material objects, and because a picture of a word has to be distinguished from a word tout court. . . . The subtle tension between these possibilities constitutes much of the structure of the panels in Arakawa’s spectacular work The Mechanism of Meaning, which almost rises to the level of philosophy through the fact that it is about the sort of decision I have just described. Arakawa’s panels look like showcards in a demonstration of some daffy IQ test, on which the words are not mere shapes but genuine imperatives, to which the viewer must respond, these not being paintings you merely look at. . . . And so after all you find yourself delivered back to the paint as something to look at and not merely heed, and the letters themselves are rewardingly painted."

Idea No. 1, 1962, acrylic, crayon, and graphite on paper, 14 × 11 inches (35.6 × 27.9 cm)

Arakawa

The Essential Blank

In the preface to the 1988 revised edition of Arakawa’s and Madeline’s book The Mechanism of Meaning—to which architectural drawings and notes were added—the idea of blank surfaces as essential. This concept of “pushing easily past any grid of rationality, moving and expanding every which way” so as to do justice to “the poetic jump!,” is crucial to their mission. An active reader/perceiver has to be constructed, as the authors say, for the “reordering, which is what the process of art is.” The exertion demanded of the observer/experimenter, also termed “the participant,” depends on an open-ended mental situation. The term blanco, or blank, in all its sense of unlimited vast expanse and parallel possibilities, borders on the essential Buddhist concept of Sunyata. Take a look at the rightmost panel from the work Blank Lines or Topological Bathing (1980–81), which urges the reader/perceiver to approach blank amidst a field of arrows and shapes disappearing in wonderful blurred smudges. Look long enough and you, too, may dazzle at the endless “reorderings” available.

Schopenhauer, one of Arakawa’s favorite thinkers, said it straight out: “Genius hits a target no one else can see.” Arakawa remained excited about the concept blanco—as in “blank,” “white,” “target,” and Joanot Martorell’s chivalric Catalan novel Tirant Lo Blanch, published in 1490 and called by the priest in Don Quixote “the best book in the world.” When we speak of blanco, targets, and genius, as Arakawa did, we find ourselves aiming at something that wonderfully runs away. All of which, of course, leaves us with a delight in “almost nothing” yet no less exciting, as in Hard or Soft No. 3 (1969), which states “These arrows indicate almost nothing.”

Arakawa’s Leonardo obsession returns here, alongside all of those panels, those nothings, of The Mechanism of Meaning that existed only in Arakawa’s mind. Leonardo wrote of his projects left unfinished, “Tell me. Tell me. Tell me if ever I did a thing. . . . Tell me if anything was ever made.” In making the last sketch in his notebooks, with four triangles on the right, he breaks off “perche la minestra si fredda,” “because the soup is getting cold.” This, his final piece of writing, reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s next-to-last diary entry, written on Saturday March 8, 1941:

"I insist upon spending this time to the best advantage. I will go down with my colours flying. . . . Occupation is essential. And now with some pleasure I find that it’s seven; & must cook dinner. Haddock & sausage meat. I think it is true that one gains a certain hold on sausage & haddock by writing them down."

These inventors—Leonardo, Woolf, Arakawa— enjoyed conception more than completion, relished every detail and the world in flux. There was, for these thinkers, something always to be learned, some detail, some word, some stroke to be added: those unexpected leaps from that related thing seen to the thing unseen.

From Mechanism of Meaning: Presentations of Ambiguous Zones of a Lemon, 1971, acrylic, art marker, and graphite on canvas, 72 × 48 inches (182.9 × 121.9 cm)

Arakawa

Be an Apple!

One day, Arakawa told me a tale about going to see his sound engineer and saying—

Arakawa: Make me the sound of apple!

Sound engineer: The sound of cutting an apple?

Arakawa: No, the sound of apple!

—and I thought of Cézanne saying to his models, “Be an apple! Be an apple!” I try to remember if Arakawa was saying: “Make me apple!” The power of the ambiguous has invaded my memory. But D. H. Lawrence wrote of Cézanne, “[It’s] the appleyness, which carries with it also the feeling of knowing the other side as well, the side you don’t see… The eye sees only fronts, and the mind, on the whole, is satisfied with fronts. But intuition needs all-aroundness, and instinct needs insideness. The true imagination is forever curving round to the other side, the back of presented appearances.” That’s what Arakawa was about.

Text by Mary Ann Caws