9 minute read

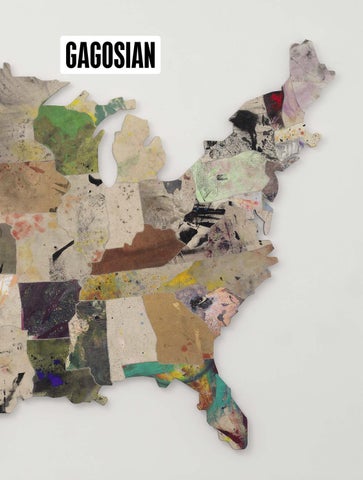

Jean-Michel in Black and White

Fred Hoffman looks back on the creation of Jean- Michel Basquiat’s Tuxedo (1983), examining the work’s significance in relation to identity and the hip-hop culture of the 1980s.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Mostly Old Ladies), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 5 ⁄8 × 15 ¼ inches (49.8 × 38.7 cm). Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT

Shortly after Jean-Michel Basquiat settled into a new studio in the gallery of Larry Gagosian’s Venice residence, in 1982, he and I started the production of the first of his large-scale silkscreen works. Composed from fifteen individual drawings and one collage on paper, this work, which upon completion would be titled Tuxedo, required a fair amount of technical know-how and some interesting choices by the artist. Basquiat wanted to reverse his original artwork from black images and text on a white background to white images and text on a black background. This was achieved photographically, turning the artist’s original artwork into one large silkscreen. During production, I didn’t give much thought to Basquiat’s intention in reversing the original artworks, but from the moment Tuxedo was completed, it became clear that his decision to turn everything black in the work into white and everything white into black was not merely a look he desired to achieve. Basquiat’s aesthetic decisions were his means of questioning certain social and cultural assumptions, with identity most important among them. (2)

Tuxedo was completed at virtually the same time in early 1983 that Basquiat produced the early rap record Beat Bop. Released on the label of the artist’s own Tartown Record Co., the long-playing album was made in collaboration with Fred Brathwaite, Toxic, A-One, Al Diaz, and Rammellzee. Basquiat’s cover art shared Tuxedo’s reversal of blackand-white imagery, further testifying to his fascination with the aesthetic look he had explored in that work.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Jackson), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 ¼ × 15 ¼ inches (49 × 38.7 cm). Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT

We timed the production of Tuxedo so that the completed artwork could be included in Basquiat’s exhibition at the Larry Gagosian Gallery in West Hollywood (March 8–April 2, 1983). It became a striking counterpart to the rich, colorful paintings, laden with multilayered images, that formed most of the exhibition. The reaction to Tuxedo was complicated. One of the artist’s biggest collectors at the time immediately committed to acquire the example on exhibit, only to change his mind on learning that the work was not unique, but one of an edition of ten. When the New York gallerist Tony Shafrazi asked Basquiat for a work for his upcoming exhibition Champions, the artist was excited to send another example of Tuxedo, only to be informed that the gallery had expected a painting for its “important” exhibition. Somewhat despondently taking Tuxedo back to his studio on Crosby Street, Basquiat responded by actually painting on this version of Tuxedo.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Plaid), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 5 ⁄8 × 15 ½ inches (49.8 × 39.4 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, purchase with funds from Mrs. William A. Marsteller, The Norman and Rosita Winston Foundation, Inc. and the Drawing Committee

Basquiat’s desire to include Tuxedo in the Shafrazi exhibition is meaningful for a number of reasons. Champions was the first important survey of the emerging generation of artists whose work reflected the new social and cultural currents in the downtown New York of the 1980s. Before their introduction in this and subsequent exhibitions (at the Shafrazi and Fun galleries), certain of these artists worked primarily on the streets. They soon became identified as “graffiti artists,” because they tagged primarily outdoor locations with images and texts. The Champions exhibition quickly became seen as marking the arrival and validation of this new generation, and their transformation from artists of the street to an accepted presence in established galleries. By presenting Tuxedo in this context, Basquiat wanted to introduce a completely new look; not only was the work distinctive, it was “cool.” It was for this reason that he named the work Tuxedo: the work conveys the qualities of elegance, refinement, and a sense of mystery that a tuxedo might bestow on its wearer.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Olive Oil), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 ¼ × 15 3 ⁄8 inches (49 × 39 cm). Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT

Basquiat’s choice of Tuxedo for this groundbreaking group show suggests his confidence that the work would immediately be perceived as a manifestation of cool, and, as such, would assert his unique voice in downtown hip-hop culture. Although he had a brief history as a graffiti tagger, he had moved on to the New York art world establishment. Tuxedo represented Basquiat’s new way of tagging, of making his aesthetic activity a declarative act. Just as all taggers have their “own arrow,” the key artistic choices resulting in Tuxedo, and especially the decision to reverse the whites and blacks, resulted in Basquiat finding a completely original means of expression. (3) Tuxedo became his declaration that he still embraced the spirit of street culture.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Quality), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 ½ × 15 ½ inches (49.5 × 39.4 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, purchase with funds from Mrs. William A. Marsteller, The Norman and Rosita Winston Foundation, Inc. and the Drawing Committee

Tuxedo shares hip-hop’s blurring of identity. Much like the voices of the early rappers and black poets of the early 1980s, the work pulls the viewer back and forth between the world of a black man in a white world and that of a white man in a black world. The aesthetic appearance of many of its individual text/image sections also acknowledges hiphop and rap culture. This is especially clear from the fifteen drawings that were the basis for the silk screen, two of which are in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art and four in the collection of the Brant Foundation. Executed in oil stick and ballpoint pen, the drawings present layerings of individual words and short lines of text with the occasional insertion of an image. In their density and compactness, these drawings, along with those used in the follow-up silkscreen-on-canvas Untitled (1983), also produced in Venice, California, are unique in the artist’s oeuvre. Basquiat’s working method in each of these works is unclear: it is unknown whether he began at the top or the bottom of the paper, and whether he worked first in oil stick or ballpoint pen. He probably went back and forth, a word or phrase inspiring a new association, resulting in an intertwined web of text and imagery. Words and phrases are often repeated, sometimes multiple times.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (Cheese Popcorn), 1982, oil paintstick and ballpoint on paper, 19 ¼ × 15 ¼ inches (49 × 38.7 cm). Courtesy The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT

In his mixing, combining, and layering of words, images, and graphic references in these drawings, Basquiat turns the recognizable and obvious into the new and unexpected. Hip-hop and rap artists employ similar strategies, and their lyrics have a similar density, intensity, and diversity, driven by an underlying beat that echoes the raw edges of street life. Yet while Basquiat shared a certain spirit with hip-hop culture, and some of the same historical and cultural influences, he stood apart.

Being based on fifteen drawings and a collage, Tuxedo comprises fifteen distinct sections along with an image of a crown at the top. The texts and images are highly structured and ordered: each of the bottom two rows contains four distinct, blocklike configurations of text, followed by three sections in each of the two rows above them, followed by one section directly below the crown. Within several individual panels Basquiat has drawn ladders and arrows, and these, combined with the work’s basic structure, invite the eye to move from bottom to top, implying ascent toward a spiritual place symbolized by the crown. While the pathway depicted is, predictably, not diagrammatic, and is far from a reliable road map, it nonetheless directs us upward, with Basquiat’s arrows literally pointing the way and the ladders in at least one section of text, and images in each of the bottom three levels, inviting us to climb. As we move up, the information becomes increasingly sparse: we have moved from a vast array of facts, symbols, and references toward a realm less well defined.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Beat Bop, 1983, album cover and back cover, Tartown Records, 12 ½ × 12 ½ inches (32 × 32 cm)

The large crown at the top announces an arrival. Freed from references to the constant bombardment of information and stimuli experienced on the street, Basquiat’s crown declares a state of liberation. If the lower part of Tuxedo, paying tribute to the spirit of hip-hop, captures the visionary quality of Basquiat’s social observation, the positioning of the luminous white crown at the work’s summit indicates a leaving behind of one’s daily experience.

Text published in full in The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gallery Enrico Navarra, Paris and New York, 2017

Artwork © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

(1) Monologue from Saturday Night Live, December 8, 2012

(2) It is interesting to note that Jean-Michel Basquiat’s large silkscreen-on-canvas Untitled (1983), produced immediately after Tuxedo and sharing with it the reversal of imagery from white into black and black into white, was the first of his works to enter the collection of an American museum. Untitled was given to New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1984, in honor of Basquiat’s inclusion in the museum’s 1984 exhibition An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture. The work was illustrated in the catalogue but not included in the exhibition. Over the subsequent thirty-two years the museum completely overlooked it, and excluded it when first putting the MoMA collection online. It was not exhibited in the galleries until 2015. In 2014, when MoMA began a collaboration with the clothing store Uniqlo, a cropped image of Untitled was used as the signature image for the marketing of the store’s “SPRZ” collection of iconic artworks applied to clothes. Only then did the museum publicly recognize the work as part of its collection.

(3) The idea that graffiti artists should have a unique look or expression, which they refer to as their “own arrow,” appears throughout the literature on graffiti culture. See, for example, Ilyse Spiegel, “The History and Evolution of Arrows in Graffiti Art,” February 10, 2011, available online at http://ezinearticles. com/?The-History-and-Evolution-of-Arrows-in-Graffiti- Art&id=5896977 (accessed June 2018).