18 minute read

F o c u s o n F r o n t l in e r s

FOCUS ON f r o n t l in e r s

Advertisement

Matt King, M.D., Critical Care Physician Mike Newhouser, Grocery Clerk

As Gallatin faced an unprecedented lockdown during the COVID-19 crisis, firefighters, police officers, and healthcare workers weren’t the only ones serving on the front lines. They were joined by grocery clerks, restaurant workers, and others serving in essential worker roles. This article tells the story of eight Gallatin residents who found themselves in frontline roles during the great pandemic of 2020.

M a t t K in g , M .D . - SUMNER

REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER

What does a doctor in a critical care unit do during a pandemic? Dr. Matt King can answer that question. He has been vice chief of medical staff at Sumner Regional Medical Center since 2019 and medical director of the hospital’s critical care unit since 2015. management of the coronavirus,” Dr. King said. “They could see it coming. In early February, they started stockpiling personal protective equipment. They were able to procure some things that later became scarce, including air scrubbers to keep the virus from spreading.” unit. “During the early days of the outbreak, we were trying to minimize the number of workers that came in contact with coronavirus,” he explained. “I took the rst r un an r e f r three weeks straight so the medical center’s other two intensivists could limit their potential contact with the virus.”

Before COVID-19, Dr. King worked as an intensi ist a h sician s eci ca trained to take care of critically ill patients. He worked exclusively in the critical care unit with no outpatient responsibilities.

As the COVID-19 situation loomed on the horizon, things started to change. Fortunately, Sumner Regional Medical Center was ready. A previously unused intensive care unit was repurposed as an isolation unit for coronavirus patients. “Our management team had some pretty incredible foresight in terms of As medical director of the critical care unit, it was Dr. King’s job to coordinate staf n in the ne is ati n One of the biggest challenges Dr. King faced involved a COVID-19 outbreak at a local nursing home. “We took in close

to 100 patients in a weekend which is about four times what we would normally do in that amount of time,” he said. Patient isolation also created challenges. “It's emotionally taxing to tell a family member over the phone or FaceTime that their loved one is dying.” If you’ve visited that location, you’ve probably seen him. He’s one of the friendly faces who will appear if you need assistance during the scanning and bagging process in the self-checkout area.

Working as a frontliner created personal challenges for Dr. King, inc u in the if cu ties f ein se arate fr his fa i ha t is ate fr ife an three i s f r the rst nine weeks of the pandemic,” he remembered. “They moved into my in-laws' house down in Florida while I stayed here in Tennessee. It was very hard because the days were taxing, and there was no one to share things with when I got home.” Dr. King’s isolation from his family turned out to be a blessing when he ended up with his own COVID-19 diagnosis. “Several weeks into the pandemic, I traveled to New York to help in the ICUs where they were short on healthcare professionals,” he said. “While I was there, I contracted coronavirus and then came back to Gallatin and spent two weeks in quarantine. That was the most personally challenging time of the pandemic for me.”

Dr. King noted big differences between the environment at Sumner Regional and the situation in New York, especially when it came to how well hospital staff members were protected. “While working at Sumner Regional, I didn’t feel any anxiety about exposure because we were so well prepared,” he said. “In New York, it was a different story. They didn't have the equipment like Sumner Regional had. And they were so overwhelmed that they just had coronavirus patients everywhere mixed in with non-coronavirus patients. People were stacked up in rooms.”

Though the experience was challenging on many levels, Dr. King learned several lessons about human resilience in the face of adversity. “It has been fun seeing how creative people can be with their recreational activities, especially outdoors,” he added. “It has also been inspiring to see healthcare workers come together and help each other out.”

M ik e N e w h o u s E R , KROGER

During the pandemic, everyday workers in essential businesses were thrust into new roles as frontline heroes. Take Mike Newhouser, for example. An employee of Kr er f r near e eca es i e runs the self-checkout area at the Kroger located at Nashville Pike and the S.R. 109 bypass. When COVID-19 hit, everyday interactions with Kroger customers became much riskier. Fortunately, Kroger was quick to respond with cleaning protocols and safety measures designed to protect customers and employees. “We all had to wear masks and practice social distancing,” Mike said. “We disinfected anything that people could touch, including the keypads where you enter your credit and debit card information, and the bag racks.”

(Continued)

Rick Donley ire hter

Kr er a s ffere nancia incenti es for employees to continue working during the pandemic. “They gave us ‘Hero Pay’ for a while, which we all appreciated,” Mike noted.

Though frequent contact with the public exposed him to more risk than people who were sheltering in place, Mike didn’t let fear get the better of him. “I as a itt e a rehensi e a ut it at rst added Mike. “I focused on trusting in the Lord and doing what I was supposed to do. I had faith that it would all work out.”

R ic k D o n l e , GALLATIN

FIRE DEPARTMENT

ire hters ut their i es n the ine every day as they work to protect life and property. But what happens when an invisible enemy shows up?

Rick Donley knows. As a station lieutenant at Gallatin Fire Department’s Firehouse #4 at Big Station Camp Creek Road, Rick is responsible for an engineer, t re hters an an cre f his engine company responds to a call, Rick is the man in charge.

In mid-July, Rick started feeling under the weather. On July 19, he woke up with a headache, nausea, and fatigue. The next day was no better. Several days later, Rick got the unwelcome news: COVID-19.

Rick went home to quarantine and recover, monitoring his oxygen levels with a PulseOx that his sister, a nurse practitioner, gave him. A few days later, faced with diminishing oxygen levels and a rising fever, Rick was admitted to Sumner Regional Medical Center. But things didn’t get better, despite breathing treatments and medications. “There are e e etrics that ct rs use t determine how severe your case is,” Rick remembered. “I was borderline on most of them, so they kept me in the hospital. The fever stayed and all I could do was sleep. I didn’t eat for about nine days.”

Ultimately, plasma drawn from patients in Washington, D.C. who had recovered from COVID-19 helped Rick turn the corner. “Physically, I felt better right away, but the isolation was taking a toll. I was in the hospital for eleven days and I couldn’t see my family,” he explained. “When you’re in your 40s like I am, you don’t think much about death. When you’re alone in a hospital room, there’s nothing to do but think. I could have ended up in a coma on a ventilator. I could have died alone, without being able to say goodbye to my family. There was a lot of emotion.”

As Rick was on the mend, he was overwhelmed by the outpouring of community support. “I was incredibly humbled by how much my city loves me,” he said. “I got hundreds of phone calls from people all over the country. Mayor Paige Brown called me every single day. The Police Chief, the Fire Chief, and the EMS director all called e re atta i n e en sh e at the corner of Bledsoe and Steam Plant. To have my whole crew out there waving at me was incredible. I got up in that window and cried. And then my family started doing the same thing. Once a day, they'd come to the corner there and give me a big heart sign and wave at me and tell me they loved me.”

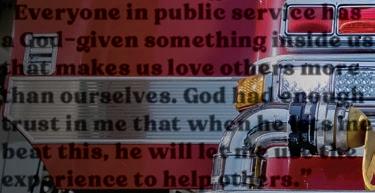

Though Rick can’t pinpoint where or when he was exposed to the coronavirus, he’s clear about what the experience has taught him. “This had to happen for a reason,” he added. “Everyone in public service has a God-given something inside us that makes us love others more than ourselves. God had enough trust in me that when he lets me beat this, he will let me use the experience to help others.”

TA B AT H A G R E G O RY

O’CHARLEY’S KITCHEN + BAR

M IC H A E L G R E G O RY

FORMER LOCAL RESTAURANT

MANAGER

What was it like to work in a restaurant during the COVID-19 pandemic? “It was challenging, to say the least,” admitted Tabatha Gregory, who manages O’Charley’s Kitchen + Bar. Tabatha wasn’t the only one in her family working in a restaurant during this disruptive time. Until September 2020, her husband,

Brittany Piro, R.N., Emergency Department Director

Michael Gregory, managed a local eatery. In fact, between the two of them, this couple has more than 30 years of experience in the restaurant industry. They’ve each seen a thing or two—but nothing could have prepared them for what 2020 would bring.

When Tabatha took a few days off work in March, she had no idea that she would return to an empty dining room. “I spend most of my time on the job interacting with guests, so it was really strange to walk in and see no one,” Tabatha said. During the height of the shutdown, declining sales forced both Tabatha and Michael to lay off most of their employees. “Shifting to a carry-out only menu helped, but it wasn’t generating enough business to keep everyone on board,” Michael noted.

The pandemic created major management challenges. “For many of our employees, this job is their livelihood,” Tabatha added. “It was important for us to help them see that there was a light at the end of the tunnel, and that we were working as hard as we could to make sure they had jobs to come back to.”

When restaurants’ dining rooms were allowed to reopen in May, keeping employees and customers safe was a top priority for both. “We let our customers know that we were taking every possible precautionary measure, down to the sanitation of team members, packaging, and even the food,” Michael explained. But there were new worries. With four f their e au hters sti i in at home, Michael and Tabatha knew that reopening their dining rooms meant possibly bringing the virus home to their family. “We did everything we could to protect ourselves,” Michael noted. “Fortunately, no one has gotten sick.” As diners returned to her restaurant, Tabatha watched their generosity with amazement. “Our guests knew that our servers had been out of work, and many of them were leaving very large tips,” she added. “I lost count of how many people thanked us for our service and said that they wanted to do their part to keep businesses going. We are incredibly grateful to everyone in the community who supported us.”

B r it ta n y P IR O , R .N .

SUMNER REGIONAL MEDICAL

CENTER

For the last 13 years, Brittany Piro has put her nursing background to work as the director of Sumner Regional Medical

(Continued)

Patrick Collum, R.N.

EMS Captain

Joey Collum, R.N.

Emergency Nurse Manager

Center’s emergency department, which includes emergency rooms at Sumner Regional and Sumner Station. Managing a busy ER is nothing new to her.

Then, in early 2020, the storm clouds were brewing. “As early as February, we started seeing reports about the virus in Asia and Europe, so we started preparing for the impact here in our community,” Brittany said.

That early preparation turned out to be a smart move. “I got a phone call with instructions to open a third emergency room within 24 hours,” Brittany recalled. Just a few hours after getting her new ER situated, another call came in, this time with shocking news. Due to a suspected COVID-19 outbreak, more than 100 elderly patients were being evacuated from a local nursing home— and they were headed for Sumner Regional’s emergency rooms. It was an unprecedented scenario that would tax even the most prepared ER.

There’s nothing like a pandemic to test the skills and resources of healthcare workers. Fortunately, hospitals train for scenarios just like this, so Sumner Regional was ready. “Our focus was on being prepared so we wouldn’t be put in a reactive position,” Brittany explained. “We had plenty of personal protective equipment like masks, gowns, and face shields. We set aside isolation rooms with negative air pressure for patients who tested positive for COVID-19, which kept airborne virus particles from getting into other parts of the hospital. And we had staff members who were dedicated to caring for COVID-19 patients.”

Keeping staff members safe was a top priority. “I think everyone in healthcare is afraid of becoming positive for COVID-19 and bringing that home to their family, to their children, to their spouse,” Brittany said. “It was one of my biggest fears. I wasn’t able to see my parents for months because I didn’t want to risk exposing them.”

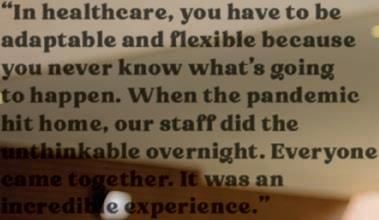

For Brittany, the silver lining in the COVID-19 cloud was seeing how her staff rose to the occasion. “In healthcare, u ha e t e a a ta e an e i e because you never know what’s going to happen,” she added. “When the pandemic hit home, our staff did the unthinkable overnight. Everyone came together. It was an incredible experience.”

Jo e y C o l l u m , R .N ., B S N

SUMNER REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER

Pa t r ic k C o l l u m , A E M T

SUMNER COUNTY EMS

First responders often come in pairs. That’s the case for Joey and Patrick Collum, a married couple who found themselves on the front lines of the pandemic. Joey is the nurse manager at Sumner Station emergency department; Patrick is captain of the Basic Life Support Division at Sumner County Emergency Management Services. Both have jobs that involve administrative duties in addition to their front-line responsibilities. For Joey, that inc u es staf n hirin r erin supplies, and other office tasks in addition to working bedside and serving as charge nurse. Patrick hires, trains, and schedules EMTS, makes arrangement for EMTs in his division to be moved into the Advanced Life Support division, all while going out on calls to pick up and transport patients.

For Joey, the COVID-19 situation created new challenges, especially when it came to protecting emergency room workers. “COVID made it a little bit tougher because you're not used to wearing full gowns and full masks with every patient who comes into the ER,” she said. “But with COVID, we had to assume that every patient coming in might test positive, so every employee needed to be fully protected before interacting with patients.”

atric s i est cha en e as urin out how to take care of his people while they were out taking care of everyone else. Like Joey, Patrick was responsible for making sure that everyone on his staff had the personal protective equipment they needed. But he had another concern: making sure that everyone on his crew was healthy enough to work. “In the early stages of COVID, every cough was suspicious,” he explained. “The hardest part was determining who was healthy and protecting those people from exposure.”

As the COVID-19 situation escalated, Joey and Patrick wondered what would happen if one or both ended up sick. As the situation crested, the wondering morphed into fear, especially about the impact on their family. “We were both terri e atric a itte e th ha t t r n matter what. If something happened to us, what would happen to our three girls?”

Though Joey and Patrick did their best to protect their children from the hazards they encountered at work, it came at a price. “We were scared to hug our kids,” said Joey, “and our girls didn’t understand why they couldn’t hug us or cuddle in bed with us anymore, especially early on when there were so many unknowns.”

t as a if cu t ti e f r the u fa i ur un est has said many times that she hates COVID because she couldn’t attend school to see her friends nor hug us,” added Patrick. “One of the hardest things for me was getting off work after caring for the community and not being able to be a normal parent to my kids.”

The pandemic drew attention to an important but often overlooked fact about the nation’s healthcare system. “The entire s ste is incre i fra i e sai e e e in rst responder roles typically run themselves ragged working crazy hours. When a disaster happens and those hours increase even re rst res n ers ften n the ha e n thin eft in the tank. We saw it happen all around us. No one had any idea just how devastating this situation would be to healthcare workers.”

Jo n a t h a n M c A l l is t e r , GALLATIN POLICE

DEPARTMENT

s a canine f cer r in f r the a atin ice e art ent Jonathan McAllister gets around. In normal circumstances, nathan an his canine f cer ast e s en st f their time assisting with felony response calls and serving as a narcotics unit dedicated to getting drugs (and drug dealers) off the streets.

Of course, 2020 has been anything but normal. For Jonathan, the year has been like no other. As the COVID-19 crisis started to unfold and people sheltered in place, the number of narc tic searches an traf c st s r e hen ca s ca e in, Jonathan was extra cautious, wearing personal protective equipment and limiting contact with the public as much as

Jonathan McAllister & Castle ice f cer anine f cer

possible. “We're not used to social distancing and having to wear masks,” Jonathan said. “Whenever I would see somebody wearing a mask, it would automatically raise suspicion. But now everybody's wearing masks and we’ve had to get used to it.”

s a ice f cer r in n atr c ntact ith the u ic create an e tra ris f e sure t the c r na irus f cers adopted CDC-recommended protective precautions and the a atin ice e art ent a e f cers t han e certain lower priority situations over the phone. “My wife and I are expecting a baby soon, so I wanted to be as careful as possible,” Jonathan added.

If the pandemic taught Jonathan anything, it showed him how much he values interaction, especially with his loved ones. “My wife and I work different schedules and I don’t get to see her as much as I’d like,” he explained. “For most of my day, it’s just me and the dog in the car. Having to socially distance around my older relatives has really shown me how important those relationships are to me. When you have to keep six feet away from someone you would normally hug, it’s hard. It took a pandemic to show me how much those close relationships mean to me.” §

Local long-term care facilities found ways to connect families and residents during the COVID-19 pandemic.