Being a part of FBA has truly changed my college experience and career. I found my people and close friends through FBA who I will continue to stay in touch with after the year comes to an end. My journey to FBA had a rocky start as I was denied from joining the club for the first three semesters of my time here at GW. However, I continued to apply and follow what the organization was doing because I knew the FBA was the right fit for me and the only student organization that I wanted to be a part of. Even as a graphic design major, I was still drawn to the creative opportunities that FBA had to offer and the experience that I could gain from being a part of George’s production. I also wanted to find like minded people who I would be able to share my love of fashion with and I was met with exactly that.

Last year I was the head graphic designer for George V and it was an amazing learning experience and opportunity to put my graphic design knowledge to use. George creates a chance for students to have their visual or written work presented in a professional-level magazine and it let me do exactly that. This year I served as the organization’s president and it is an experience that I will be forever grateful for. I learned so much about team-work, delegating, communication, and leadership. I also learned a lot about myself and gained a confidence that I didn’t have before.

I get emotional every time that I think about the breadth and the amount of work that was put into this issue of George. It is so telling how important FBA is to our members and board considering that creating this magazine takes hours and hours of work with no incentive other than the contribute to a 100% student-made magazine. I am incredibly proud of the accomplishments that this year’s executive board and members have been able to complete and I cannot wait to see the future of GWFBA.

Love,

Brooklyn Ramos President

Looking back on my time in FBA, when I joined my freshman year, I had no idea how much FBA would impact my life both professionally and personally. The FBA community is unlike any other. As Vice President, it has been so fulfilling to witness our members champion their love of fashion and make new connections with others as they explore what they can do in this space.

We have accomplished so much this year: organized incredible events, welcomed captivating guest speakers, thrown an incredible launch party… but more than these accomplishments, the creative work contained in this edition of GEORGE marks what truly makes FBA so special: the people. I truly hope that the relationships you make with your fellow members enrich your life as much as they have enriched mine. Though this edition is about looking back on your archive, I know the bonds you create with others in FBA are timeless. Brooklyn and I are so proud of everyone’s hard work, and we are even more excited to see what FBA accomplishes next. Thank you for inspiring me another year as a member of this organization. Thank you FBA.

Love,

Jack Couser Vice President

Hello everyone and welcome to the sixth edition of GEORGE!

Looking back at this year of FBA, I am so amazed by how much work we were able to do, the community we’ve been able to foster and just how much passion I felt from e-board and members whenever we came together. I became a member of FBA in my sophomore year at GW and it instantly became a place where I knew that I could fully dive into my passion for fashion journalism and fashion critique. Over these years of being in FBA, through the highs and lows, the liberating freedom of pursuing one’s passion and the responsibilities that come with it, I have always been so grateful that this kind of space exists at GW. I’m grateful that every week we all come together to forget about exams and internships and the stress of student life to talk about and make fashion.

In this issue you will find all the ways in which our fantastic members explored this year’s theme, “In the Archives’’. There are retrospectives on iconic designers, breakdowns of the inspirations behind today’s favorite trends, interviews with true vanguards of the fashion industry and a critical look at the ever-evolving link between fashion and society. In a world of international conglomerates, hollow praise from glossy magazines and consumer overconsumption, I hope this magazine offers an alternate way to view fashion and encourages others to be critical about the current fashion landscape.

I am beyond proud of every single writer, graphic designer, photographer, model and everyone else that helped make George VI possible. Please enjoy this issue of George magazine!

Happy reading,

Alex Marootian Editor-in-Chief

ENJOY OUR CREATION.

Editor-in-Chief, GEORGE

Alex Marootian

Editor-in-Chief, After Hours

Nneoma Ileoje

Graphic Designers

Ethan Valliath

Ethan Fernandes

President Brooklyn Ramos

Vice President

Jack Couser

Social Media

Shayda Vandyoussefi

Events

Madeline Ng

Keja Ferguson

Business Outreach

Ava Zohn

Reva Dalmia

Treasurer

Justine Phi

Stylist

Isabella Kelly

Members

Sarah Strausberg

Sofia Gianetto

Sonali Sood

Kiki Baumgartner

Kamila Ramos

Briana Diaz

Olin Peterson

Julia Wasik

Cece Nugent

Maya Welch

Karina Reddy

Alex Johnson

Anusha Trivedi

Kelly Rahimi

Hayden Lambek

Katerina Kontoleon

Orli Rose

Sofya Kurilina

Samantha Sandow

Megan Kreuger

Cora Erice

Sebastian Arreola

Juliana Molina

Alexandra Donahue

Nicola DeGregorio

Jennifer Linares

Samantha Penzone

Callie Hoffman

Philippe

Tchokokam

Samantha Travis

Sofia Daniele

Trinity Vo

Christina Zhao

Lisamarie Preci

Rachel Kimmel

Lara Jasaitis

Enith Munroe

Shamira Guel

Matthew Huang

Kimaya One-

Routier

Caroline Heym

Martina Tsimba

Eliza Thorn

Ava Beatriz

Stamatelaky

Monica Carty

Natasha Brewer

Kaitlin Yang

Kailee Whelan

Eliza Auslander

Christine Yoo

Tye DuSoldO’Connor

Soleil Lech

Jordyn Neugarten

Sravani Mannava

Emily Rose

James Pomian

Alexandra Ennabi

Ayla Karimova

Gabrielle Clark

Sloane Bernstein

Declan Kelly

Nitya Jaisinghani

Fayre Li

Lauren McNealy

Vaishnavi Vangani

Shelby Downey

Kathy Grimes

Kate Young

Ashley Ho

Ben Witt

Liv Pressman

Amari Sharma

Grace Riker

Lucas Golluber

Tony Boyd

Lexi Schultz

Cora Erice

Audrey Lorence

Noah Edelman

Megan Taylor

Abby Turner

Paige Nelson

Sarah Gross

Leah Meyerson

Chaewon Lee

Molly St. Clair

Anna Mennuti

Bebe Limanowski

Linwood Tie

Kyla Robinson

Jenna Xavier

Kamora Provine

Juliana Herbst

Alexia Barillas

Leila Shahidi

Nick Patterson

Zoe Luce

Jordan Agay

Alexa Kieltyka

Dre Pedemonte

Charles Malaga

Trinity Vo

Desiree Camargo

Aryana Samadi

Ana Vucetic

Garima Khatiwada

An Ngo

Adeline Monks

Shritha Pillai

Nicholas Anastacio

Senan Pol

Shreya Kodu

Kaity Hendricks

April Chism

OAKLEY

EUGENE RABKIN

OAKLEY

EUGENE RABKIN

When discussing fashion, feelings of stress and restriction can emerge, but what if I told you two sets of designer rivals founded fashion to instead promote feelings of power, femininity, and creativity within oneself? Similarly to the tension between the icons Coco Chanel and Christian Dior, Charles Fredrick Worth and John Redfern, the creators of the fashion industry, were in a constant battle with their contrasting artistic visions and their various methods to make women feel powerful. However, it becomes clear that there are no winners or losers in the fashion industry and correct ways to dress. These designers’ different styles can be loved, debated, or hated, further proving that people, specifically women, should never feel restricted in how they want to express themselves— the fashion industry does not exist to please the male gaze or set a clear boundary.

Charles Frederick Worth, the “first” Paris fashion designer of the 1830s, is popularly known as the “father of modern couture”. He focused on the luxurious designs of arisocratic wardrobes. Worth’s fashion sense came from being publicly surrounded by “women from European royalty” and his early financial support, during the years of the Franco-Prussian War, can be accredited to the daughters and wives of “American nouveau riche tycoons.” Worth’s career was jump-started when Eugenia de Montiel, Emperor Napoleon III’s Spanish wife, noted two “flamboyant” dresses that he had constructed for Princess Metternich, a famous Austrian socialite. Worth took advantage of the opportunity and designed Empress Eugenia’s wardrobe— now considered a masterpiece. Eugenia was the most influential fashion icon of the 19th century, and working with her guaranteed Worth would meet other female celebrities to further his career.

Worth’s newfound popularity helped fund The House of Worth. Not known for subtlety in his dresses, many garments displayed in The House of Worth belonged to the new 1878 “princess line” that enhanced dress couture and added a new spin on his commonly outrageous gowns. Though no credit was given, the “princess line” used a silhouette from a rival fashion designer, John Redfern. Furthermore, even though Worth’s designs derived from his passion for empowering the many influential women around him, they were not yet regarded as art. The start of the fashion industry was not credibly noted and appreciated until he obtained the title of “man milliner” and began

creating men’s designs. In other words, Worth’s involvement in fashion design can be appreciated from a feminist lens. But it was not until he transitioned to a male clientele that he immortalized his stardom, further proving the inherent gender inequality of his time.

A couple of miles from Worth sat John Redfern, another Englishman. Although not well-known in the present day, in the 19th century he was busy transforming drapes into dresses. Several royal customers lined up at Redfern’s door: Princess Alexandra of Wales, Queen Victoria, and Lillie Langtry— a British socialite and stage actress. Redfern’s big break came when WC Hoffmeister, the Queen’s surgeon, asked Redfern to design his daughter’s wedding dress and bridesmaids’ dresses. The final products left many speechless, and The House of Worth officially had competition.

Unlike Worth, Redfern received little to no recognition for his influence on fashion as he rarely designed menswear. He simply wanted to explore his creativity with his female clientele and continue to empower the many women around him. Later in his career, Redfern wanted to encourage women to participate in “male pursuits” like sports. To this end, he began to take advantage of the “Dress Reform movement” and construct athleisure, similarly known as the “walking costume” or “tailor-made” which refers to women’s equestrian clothing.

Originally, athleisure wear was only fitted for men and did not frame the female body, but Redfern changed this narrative by adding more “jersey sport clothes” for women to the market. In addition to jerseys in general, Redfern used his female equestrian designs as inspiration to produce women’s wear for the more “vigorous” sports as well like shooting, golf, hiking, archery, tennis, and yachting. Due to Redfern’s famous designs, women were no longer just seeking entertainment through croquet and watching the men participate in the more appealing sports. These female designs also inspired him during his design for new Austro-Hungarian military wear. This served as a stepping stone to female participation in the military as women began to picture themselves excelling in an occupation that was not in a domestic environment.

Redfern did not only use fashion design to encourage gender equality in sports, he also was able to use his artistry to encourage women to embrace their

own body types. Although the influential Alexandra of Denmark and her mistress Lillie Langtry have different physiques, they both used Redfern’s inclusive designs to define fashion for the next several decades. With an audience not composed solely of hourglass or slim figures, Redfern was able to produce a successful international business. In 1820 it became known as Redfern and Sons and was located in populous cities throughout the world. Despite Redfern’s lack of male clientele, in 1892, his company developed into Redfern LTD and was considered a “dominant force in Western fashion” that caused The House of Worth to eventually go out of business. Even though Redfern died a few years later in 1895, according to fashion scholar Daniel James Cole, Redfern’s aesthetic can still be seen in the work of Clair McCardell, Vera Maxwell, Calvin Klein, and Norma Kamali.

The modern-day fashion rivals, Dior and Chanel, used Worth’s and Redfern’s foundation of fashion to enhance the entire industry. Dior’s designs contain more inspiration from Worth while Chanel’s stem more from Redfern. Specifically, Chanel worked to accentuate a woman’s natural beauty and expand couture within a tailored sports aesthetic while Dior took advantage of the flamboyance of Worth to design elegant gowns. Not surprisingly, she was therefore appalled by Dior’s clothing as she believed a man had no place to decide what looked best on the female body. However, just like Worth and Redfern, Chanel and Dior were working towards the same goal in the end— to promote femininity through their iconic designs.

Gabrielle Chanel, later known as “Coco,” was dedicated to adding a sense of masculinity into her elegant designs similar to Redfern. Before her exploration of technical skills like sewing, Gabrielle acquired her stage name, Coco, when she was a singer in Paris dedicated to the “abolition of restrictions” that were “imposed on women.” Later on, nuns taught Coco how to sew, helping her get her start in the fashion industry. A feminist at heart, it was not until the fight for a women’s right to vote that Chanel truly began to find her passion in fashion and explore her talents in design. Chanel implemented traditional “menswear” like Redfern’s sports clothing into her female designs and avoided corsets as well as traditional dresses. Instead, she began working with jerseys, skirts, cardigans, suits, and accessories. Her 1920s style of the flapper dress and twopiece suit were worn by both Jackie Kennedy and Princess Diana who helped her become globally renowned. Chanel was forced to resign during World War II, but her competitive spirit with Dior’s uprising drew her out of retirement and Chanel again became active in the fashion industry.

Christian Dior obtained his design career after he served in the French Army during World War II. In 1946, Dior became entranced in the arts when he picked up designing in Paris under John Redfern’s mentorship.

His work “sought to restore the feminine look.” Ironically, unlike Redfern and Chanel, but similar to Worth, he achieved this goal through the use of more flamboyant designs that were constructed to enhance the curves of a woman’s body. Although many thought his designs were controversial as he was a male working to empower women, in reality, he received guidance from the three women in his life that he referred to as “his mothers:” Madame Raymond Zehnacker, Marguerite Carre, and Mitzah. In addition to these three iconic influencers, Dior was inspired by the Belle Epoque, “the clothes of the British-born couturier.” He began constructing silhouettes that consisted of cinched waists, padded hips, layers of tulle, and silk. Dior became known for these tiny waist skirts that were each around “23 kg” (50.7 lbs) in weight! In response to Dior’s work, Chanel argued that he was in fact working against the point of tailoring techniques and femininity in general with the impracticality of his women’s wear.

Chanel publicly feuded with Dior, who she saw as her foil. She was appalled by Dior’s clothing, claiming his models were “wearing clothes by a man, who doesn’t know women, never had one, and dreams of being one.” In addition, she mentioned that Dior “upholsters them” and dresses women up like “an old armchair.” Chanel’s public statement was to

make others recognize that Dior was dragging women back to the 19th century when they were commonly viewed as objects. However, contrary to Chanel’s opinions, Dior claimed his art accentuated “the beauty of the female body.” And as previously mentioned, all of Dior’s inspirations for his designs were the important women in his life. Unlike the sexist terms men used to describe women in his era, Dior publicly compared Marguerite Carre to “a technical genius” and stated that Madame Bricard “was his confidante.” Therefore, similarly to Worth, his designs and values assisted him in gaining widespread attention from female royals like Princess Margaret who helped create his legacy for generations to come.

As both Chanel and Dior’s designs still greatly impact women’s fashion today, it is clear that high couture does not have easy expiration boundaries. Dior and Chanel’s current directors are both women who make styling decisions to best represent the female population. So, even though Worth and Dior and Redfern and Chanel had different creative visions, they all worked with the goal of promoting feminism. No matter the body type of their clients or their different approaches to design, they labored to accentuate and empower the women’s natural figure, so they could feel beautiful from the inside out. Fashion is and has always been founded upon feminism, allowing for individual self-expression and celebration.

Noelle Cardi, Abby Turner, Eliza Thorn Photo by Ethan Valliath

Fashion is and has always been founded upon feminism, allowing for individual self-expression and celebration.”

The purpose of fashion is to aid individuality in people’s journeys of self confidence and expression. Ever since the beginning, fashion has been created to act as an accessory to the person. People buy clothes as a means to show their wealth, status, creativity, uniqueness, etc. As fashion became more popular, the roles started reversing and the art became the main focus. Jobs were created, such as modeling and photographers, to showcase these fine works of art on the runway to sellers. Among the industry, a select few individuals were branded as “fashion icons” of each decade. As this year’s George Edition is “In the Archives”, let’s look back at some legendary icons of each decade.

Audrey Hamilton

Photo by Ethan Valliath

Audrey Hamilton

Photo by Ethan Valliath

The roaring twenties were dominated by fashion designer and icon Coco Chanel. Coco Chanel was the infamous designer of the Chanel brand, which swept the US starting in the 1910s, introducing a revolutionary change in women’s fashion silhouettes. Out came the tight air-constraining corsets and in came loose and fluid silhouettes. Yet what is unique about Coco Chanel compared to the others on this list was that she was able to be both fashion designer and fashion icon. To explain the full extent of her cultural presence, we must examine some of the photos of her in 1920s fashion. A signature of Chanel is her signature pearls, which can be seen throughout photos of her. What also can be seen is her loose fitted silhouettes that she worked to engineer, which was influenced by the Orientalism fashion trend arising in the 1910s. After a ballet featuring loose fluid silhouettes gained traction, fashion designers like Paul Poiret, Lady Duff Gordon, and Jaques Doucet popularized the style even further. Chanel often wore cloche hats due to their simplicity in a time that deemed embellished hats unpatriotic while men were fighting in WWI. Everything she wore helped define the style of the decade, and she was able to represent the duality of fashion designing and modeling. The next fashion icon on the list is Audrey Hepburn, the picture of elegance and grace after a dreary World War II. Her outfits were characterized by defined clean lines through her dresses and shirts. A great example of this was her little black dress from Breakfast at Tiffany’s, accessorized with white pearls, opera gloves, and sunglasses. The little black dress was introduced by our last icon, Coco Chanel, and then was adapted into a long cocktail dress by Givenchy for the movie. Its popularity started a trend for future creative directors of Givenchy to revamp the little black dress dress including Alexander McQueen, Riccardo Tisci, and John Galliano. The little black dress is still associated with Audrey Hepburn, and continues to be a timeless classic even today. Another aspect of Audrey Hepburn’s iconic style was her French inspired casual outfits. A great example of this is her casual outfits consisting of gingham/ pastel trousers with a plain white blouse and ballet flats. Especially since French fashion was popular but didn’t reach the US at the time, her European nationality and American residential status allowed her to be ahead of the times in fashion trends and reflect it.

Unlike the previous decades

mentioned, none of these had a radical or gender fluid approach to fashion like the sixties did. Twiggy, a British model and actress, helped bring the mod movement to the masses. Mod first originated in Britain as a group of people that differentiated themselves from the cultural norm of sleek and sexy silhouettes, eventually making its way to the US with the popularization of British music and their stylistic choices. For example, the Beatles came to America around the 1960s and influenced other American musicians to wear more mod styles. A quintessential mod piece that embodied this radical change was the popularization of the mini skirt, a direct defiance of the sexual norms that women were put under, created by London-based designer Mary Quant who Twiggy would go onto collaborate with. Twiggy was seen in many instances of wearing mini skirts, with accompanying mod items like Mary Jane shoes and crochet sweaters. Another shift from feminine to unisex was Twiggy’s usage of shift dresses. Shift dresses were monumental because of their loose and boxy silhouette, in direct opposition to the previous form fitted dresses that fashion was used to. Fashion brands like Givenchy and Balenciaga transformed the dress style to be its iconic look now.

As the seventies rolled in, Diana Ross was the disco star that made waves when it came to her personal style. Disco fashion originated in gay underground nightclubs and then assimilated into the general club party scene, which was overloaded with neon lights and disco balls. Due to the decoration being so stylish, the outfits were made to stand out in the crowd. This style was what Diana Ross incorporated into her stage outfits and became an icon that represented just one of many 70s style trends. Diana was frequently seen in sequined gowns, spangled body suits, flared pantsuits, and any dress that falls under the category of sparkly. An iconic moment that explains Diana Ross’ impact on the seventies disco era was her photoshoot with Motown Records. Batwing sleeves, plunging neckline, sequin tassels hanging from her sleeves and alternating sequins all around the dress is the perfect example of what made the seventies special.

If Diana Ross was the undisputed queen of disco, Madonna had the same title for pop and punk sexuality. The 80s punk trend derived from influences of punk rock, and became a form of rebellion, especially among the LBGTQ+ community . It was a more underground form of expression, but Madonna chose to be a risk taker when it came to fashion. Even though she catered towards a mainstream pop audience,

Madonna’s style was a mix of new wave, punk, and high fashion. A classic Madonna outfit would consist of fingerless gloves, statement jackets, and a plethora of necklaces and jewelry. Her performance outfits were even more outrageous, with the most iconic being her Jean Paul Gaultier pink cone bra. This bra oozed sex and sensuality, but on Madonna’s body it translated as taking back the authority and power that men used to have on women’s bodies. Madonna’s charm also laid in her ability to ripen with age and continue her fashion ventures on and off the stage.

All of these women have one thing in common: they wore clothes but in an iridescent way that allowed them to shine bright. If you ever see any of the outfits you just read about, you would instantly think of the fashion icon associated. Fashion was able to help bolster each person’s influence, and fashion made. Clothing is all about expressing oneself, and I would have to say that these women were the most elegant yet bold about their choices.

If you’re at all familiar with the fashion scene, chances are that you’re familiar with Vivienne Westwood, a pioneer of punk fashion who has revolutionized the fashion industry since the 70s. The Vivienne Westwood brand has a quality of timelessness thanks to their innovative designs that serve as an intersection of historic aristocracy and the modern punk aesthetic. Both the brand’s forward-thinking styles and its anti-establishment image have allowed Vivienne Westwood to continue to dominate the fashion landscape well into the twenty-first century.

Considering the dramatic impact Westwood has had on fashion, it’s surprising to note that much of her background had very little to do with fashion at all. In fact, Westwood was employed as a teacher when she began her foray into fashion. She and then-partner Malcom McLaren opened a clothing store where Westwood put to use her skills as a self-taught seamstress. The store would go through a number of rebrands, eventually becoming SEX in 1974 where it catered to the punk subculture, a rebellion against authoritarianism and corporatism gaining popularity with British youth in the mid-70s. Westwood’s and McLaren’s store saw massive success with fans of the movement, and continued to gain notoriety when McLaren took over management of punk rock band the Sex Pistols in 1975. Westwood styled the group in custom designs as a way of promoting the fashion label. Thanks to its edgy image and clever branding, SEX has since been considered one of the most successful retail ventures in the U.K. and the popularity of the label would mark a strong start for Westwood’s career.

Pirates was the first ready-to-wear Vivienne Westwood collection and debuted at London Fashion Week in 1981. The collection itself was a “plundering” of history, as Westwood reconstructed historical garments for modern wearers—the first time a designer had done this, as well as the first time punk had been showcased on the catwalk. Westwood would soon split from Malcom McLaren and continue to gain acclaim in the industry as an individual. Westwood showcased her Hypnos

collection in Tokyo in 1984 and would go on to expand globally, producing both men’s and women’s wear, as well as bridalwear, shoes, fragrances, and more. Vivienne Westwood would be awarded Fashion Designer of the Year from the British Fashion Council in 1990, and again in 1991. In 2006 she became a DBE, two years after the Victoria and Albert Museum hosted an exhibition of her creations titled “Vivienne Westwood: 34 Years in Fashion.” It was the first exhibit like this that the museum had ever seen and is a testament to the incredible influence Vivienne Westwood has exerted over the decades.

Of course, the main reason Westwood rose to fame was her designs themselves: unconventional recreations of historical silhouettes and motifs, with a characteristic punk twist. The brand exaggerates and parodies the aesthetics of European aristocracies, something that befits the brand’s anti-establishment statement, but also effectively resurrects historical fashion in a form that appeals to the modern market. For example, look no further than the brand’s orb logo which first appeared in 1987 as a motif of the collaboration between Vivienne Westwood and the Harris Tweed Authority. After the success of the collection, Westwood kept the logo, a combination of the Sovereign’s Orb and the planet Saturn, and it became a new signature of the brand, representing “taking tradition into the future.” Other examples of this futuristic approach to old-world styles include the “mini-crini,” a Victorian crinoline cut to resemble a mini-skirt, and the brand’s iconic corsets, which transformed historic underwear into modern outerwear. One of the most recognizable Westwood corsets is from the Autumn/Winter 1990 collection Portrait and features Francois Boucher’s painting, Daphnis and Chloe—and this is not the only time Westwood would reference Boucher’s artwork. She modeled an evening gown after one featured in Boucher’s portrait of famous French mistress and fashion icon Madame de Pompadour (of course with some asymmetric alterations), and would also reference artists such as Jean-Honore Fragonard and Thomas

BY MEGAN KRUEGERGainsborough in other collections. And the ode to the 19th century didn’t stop there: Time Machine saw a revival of the Norfolk suit, while On Liberty and Vive la Cocotte featured outrageously exaggerated busts and bustles. To drive home the historic illusions, runway models were styled with updos, white face makeup, and beauty marks, an ode to the French rococo look. Westwood never limited herself to a single era of fashion, however, also creating new takes on Savile Row suits and the timeless Scottish tartan. “I take something from the past that has a sort of vitality that has never been exploited—like the crinoline—and get very intense,” Westwood explained. “In the end you do something original because you overlay your own ideas.”

Vivienne Westwood itself has a sort of vitality that has allowed it to experience a renaissance in the last decade. This isn’t to suggest that Vivienne Westwood was ever out of fashion, but that it has continued to appeal to new, younger audiences who have an interest in sustainability and aestheticism. Another major reason the brand continues to resonate with people has to do with the antiestablishment image it has maintained since its inception. Westwood had always made a statement through her fashion, and as of the 2010s, she and her brand were championing social causes such as environmentalism and human rights. “Climate change, not fashion, is now my priority,” Westwood said in 2014, and collections such as Climate Revolution and Save the Arctic reflect this sentiment—Homo Loquax took the issue in a political direction, featuring anti-capitalist and anti-politician slogans. She also participated in many sustainability-themed collaborations, such as the SAVE OUR OCEANS collection with Eastpak and a collaboration with Burberry for Cool Earth. Her slogan “Buy Less, Buy Well” similarly encourages responsible and sustainable consumption. Outside of climate activism, Westwood was a huge proponent of inclusive and gender-neutral clothing—Unisex, from Autumn/Winter 14-15, for example, celebrates androgyny and resists strict gender divisions. Westwood herself was known to protest quite publicly off the runway as well, even suspending herself inside a giant birdcage in London in protest of Julian Assange’s extradition in 2020, proving that she was willing to risk her reputation in the name of activism. Rather than hurting the brand, though, this became something that fans have supported and admired.

Thanks to Vivienne Westwood’s tireless forward-thinking and creativity, her brand has combined historic silhouettes with the punk aesthetic and remained popular for over fifty years. Dame Vivienne Westwood passed away in December of 2022, but her husband and long-time work partner Andreas Kronthaler has

Amari Sharma, Sam Penzone, Megan Krueger

Photo by Ethan Valliath

Amari Sharma, Sam Penzone, Megan Krueger

Photo by Ethan Valliath

expressed that her legacy will live on through the brand’s innovation: “[Vivienne and I] have been working until the end and she has given me plenty of things to get on with.” It will be a privilege to see how the brand continues to evolve and shape the fashion industry in the future.

In Tokyo, there is a rich and treasured culture centered around street style and fashion. Young people have flocked to the Harajuku neighborhood, where streets are closed for easy pedestrian traffic, to shop, socialize, and show off their outfits. Home to various subcultures, Harajuku has become a Mecca for those interested in wackier styles. What may be a youth rebellion through fashion, or simply an uninhibited form of self-expression, has made Harajuku the animated fashion center we know it as today. Beginning in the 1980s and exploding in the 1990s, the vibrant Japanese street fashion has been captured throughout the years by various photographers and fashion enthusiasts to gather inspiration and share with others. Of these archives of Harajuku fashion, perhaps the most influential is FRUiTS Magazine. Having a cult following and continuing to inspire fans of Japanese fashion today, FRUiTS has had a large impact worldwide. Lately, its influence has reached larger audiences through social media, creating new followers and sparking inspiration among new generations of fashion lovers.

FRUiTS was created by Shoichi Aoiki, a now renowned photographer. In the magazine, young people who hung out in Harajuku were photographed in the “street snap” style characteristic of FRUiTS. Interestingly, this photographic style could be described as a lack of distinct style. The magazine is filled with images of people on the street taken head on, with no special effects and within no specific setting, just on the street. Individuals, couples and friends are photographed against the

backdrop of professionals walking by, friends congregating on the curb, and shoppers walking through streets with bags. Shot very plainly, the images uniquely focus on the individual in the photo themselves, allowing their personality and self-expression to be at the center of the photo, leaving the personality and expression of the photographer on the back burner. In an interview with the New Yorker, Aoki explained that he is, “not so much photographing as [he is] collecting [his] subjects. It’s not that [he] just [wants] to take photos of people– [he wants] to see people’s inner thoughts, their personalities come to the surface. This, to [him], is fashion, and [his] goal is to document it. When [he shoots, he] is trying not to express [his] own proclivities or show [his] creativity. Seeing someone on the street wearing something killer actually moves [him] emotionally, giving [him] a feeling of pleasure.” This explains more deeply the motivations behind the creation of the magazine, and why its style is so consistent and simple. Additionally, the editing of the magazine is very minimal, with photos taking up entire pages with small captions including details of the subject’s outfit overlaid in the corner, giving full display to the subjects and their interesting and creative outfits.

The fashion throughout the magazine is varied, capturing people of many different styles, from classic to offbeat. However, the most iconic and stereotypically FRUiTS look is something more eccentric, and is sported by many throughout the pages. These more eclectic looks by women have some staple

BY JULIANA MOLlNA

BY JULIANA MOLlNA

items, including but not limited to: petticoats, statement bags (often in the shape of stuffed animals), carrying stuffed animals as an accessory, short and/or colorful hair, platform shoes, long socks or leg warmers, colorful or patterned tights, bloomers, chunky plastic jewelry, and a statement piece on the neck (large necklaces, scarves, or large collars). Despite a general theme of layering, pattern mixing, and over-accessorizing, there is still a lot of variety to be seen in the outfits of FRUiTS. With differences of color palette, fabric, and accessory choices, the distinct style of individuals shines through. Even the plainest outfits pictured in the magazine usually have an extra flair of style–perhaps an interesting hat or unique silhouette. In a conformist culture like that of Japan, the youth who wore wacky outfits were making a bold statement of individuality and rejection of fitting the norm.

Today, FRUiTS is no longer in circulation, having ended in 2017 after Aoki famously said that “there are no more cool kids left to photograph.” While the magazine is no longer around, it’s kept alive through things like Instagram, with accounts such as @ fruits_magazine_archives uploading old spreads. The spirit of FRUiTS and capturing everyday people’s outfits in street snaps is also seen in current websites like tokyofashion.com, but even more so through social media where users upload their own outfits. Despite not having an editorial reference, social media makes finding and referencing others outlandish outfits more accessible than ever. While the return of Harajuku as a booming fashion epicenter

for weirdos and eccentric dressers will likely never happen again, there are still people taking inspiration from this era of fashion, and its documentation through FRUiTS magazine serves as an important snapshot of fashion history to look back on.

There has been an influence of Japanese fashion on western fashion for decades, with well known designers like Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo having global success and influence. However, this influence was largely reflected in high fashion by people like the aforementioned designers, or in subcultures like Ganguro, Dekora, or Lolita. Where the current influence of FRUiTS style differs is in its more casual and mainstream appeal. Seen on people like Bella Hadid, the recent styles that parallel Harajuku street fashion have been deemed as the “weird girl” aesthetic online. Popularized on social media, people like @tinyjewishgirl on TikTok or Sara Camposarcone are poster girls for the aesthetic, sporting bright colors, lots and lots of layers, bright accessories, and patterned printed items. Things like petticoats, a handbag shaped like a binder clip, and a mini skirt printed with the words “MINI SKIRT” are just some of the fun, loud, and unique pieces you may find in a “weird girl’s” closet. Similarly to those pictured in FRUiTS, they’re not afraid to wear things that may seem childish. However, the outfits themselves rarely could be worn by a child, as they often include a risqué edge. These clothes are often thrifted or vintage, but are also often

by small brands, adding to the unique, one-ofa-kind factor– you can’t buy this at the mall.

What does the weird girl say about fashion today? I think it speaks to the phenomenon of “aesthetics” that now dominate fashion on social media. Cottagecore, indie kid, dark academia, coquette, normcore, old money… the list goes on. There is now a plethora of aesthetics that one can pick out and choose as their style of the month. Unlike subcultures, these aesthetics do not require any specific life changes or even a set wardrobe, instead they are only concerned with the aesthetic. This is the natural progression of style in the digital age. It is most important to look a certain way for pictures and social media, but this does not need to permeate your everyday life, nor be aligned with certain beliefs or political movements. In contrast to the youth taking a stand against conformity and challenging the generations before them, the weird girl is not trying to make a statement that is anything but visual. While the teens in Harajuku were outcasts, the main example cited of weird girl fashion is one of the most famous models of the past decade.

The rise of the weird girl also reflects the recent shift towards sustainability that many consumers are interested in. By leaning into the “weirdness” of clothing, people are able to focus on things that are not new, or not in trend. Instead of side eyeing the colorful striped skirt at the thrift store, someone may remember a weird girl they saw on TikTok and take inspiration from the bright colors and patterns. By the sourcing of many pieces being second hand and vintage, and from small, quirky brands, many of which hold sustainability and ethics as core values, consumers can contribute to a circular economy instead of fast fashion trends.

Lately, there has been a conversation about how the number of fashion trends are too high to keep up with, leading people to ultimately embrace their personal style over everything. This begs the question: Is the weird girl a celebration of individuality? While I wish this were true, we still see many overarching and micro-trends that inform consumer habits. The weird girl unfortunately fits into these trends as well. Somewhat aligned with the other recent trend of “dopamine dressing,” we can already see the more vibrant and eccentric styles of the weird girl falling out of favor for more streamlined and muted colors and silhouettes. While those who dress “weird” will always persist, their popularity will inevitably fall off. Furthermore, the deeming of the weird girl as a specific aesthetic ends up pigeonholing her into a specific category, diminishing her

sense of individuality by labeling her. By compartmentalizing such a bright and novel look, the weird girl label has taken away from the uniqueness of her style.

FRUiTS magazine has an undeniable influence in fashion and likely will for years to come. Its demonstration of individuality and personal style is an inspiration to so many people looking for their own sense of selfexpression through clothes. Reflected in the present day, the weird girl encapsulates a similar individuality found in FRUiTS, yet in a world driven by social media, showing how even the weirdest senses of style may ultimately cater to our need to belong to visual aesthetics fit for a Pinterest board or Instagram collage.

Isabella Kelly

Photo by Sarah Strausberg

Isabella Kelly

Photo by Sarah Strausberg

The Renaissance of Oakley in the Y2K Resurgence

BY DECLAN KELLY

Walking through the Tysons Corner Center just outside of DC, my friend and I decided to walk into the Oakley store and browse through. After 20 minutes in the store, we had just about tried on every model of sunglasses they had in the store. Interestingly, there was one pair of sunglasses I had worn that would change my view on Oakley in the sunglasses market, the Eye Jacket Redux. The model is a revived design from the 1990s of the original Eye Jacket that emulates the same original design principles, but with a modern twist. With the rise of Y2K nostalgia, companies spanning from many industries are looking for ways to bring back designs from the past and appease both old and new consumers. In today’s fashion industry, nostalgia plays a large role in drawing consumers in. We have seen a prime example in the increased popularity of Nike’s Air Jordan 1 and 4 models. With the models having ties to professional athletes of the past, like Michael Jordan, it is evident that consumers feel sentimental towards certain products. Oakley has taken advantage of the nostalgia movement by rereleasing past iconic designs and altering them for today’s audience. With this, they’ve demonstrated the lasting influence of Oakley’s eyewear and the sentimental shift in consumer choices.

College dropout, ex-mormon, and entrepreneur Jim Jannard began Oakley as a motocross handlebar grip company. He manufactured high-quality uniquely lopsided grips that were different from the cheap, cylindrical ones of the 70s. After failing to promote his grips, he moved on to selling motocross and ski goggles believing that the logo on an athletics head would effectively promote his company. Communications manager Renee Law was able to promote Oakley through extreme skier Trevor Bowers. With his endorsement, Oakley was able to release in 1984 the company’s first pair of sunglasses, the eyeshades, which were a mix between goggles and sunglasses. The market for premium sunglasses was a growing one, Oakley took advantage of this by embracing technology and forward-thinking design.

In 1993, Oakley began to pivot its brand for further growth through the redesign of their logo by the new VP of Design, Peter Yee. Through his designs Yee emphasized aerodynamics, biomimicry, and pulling inspiration from unrelated sources. Yee’s first design with Oakley was the cornerstone for the recent trend in “gas-station sunglasses,” the Oakley Eye-Jacket. This design was inspired by the natural shape of our eyes, and utilized unique production methods as it steered away from the conventional straight lines and blocky appearance of previous sunglasses. Yee described the creative process behind the brand’s designs at this time as a balance between “shock-in-awe” and functionality. This balance was demonstrated in the launch of their “Over-The-Top” sunglasses which donned the faces of Michael Jordan and Dennis Rodman. Today they have appeared on the face of famous Migos rapper Offset in Travis Scott’s music video for his Utopia hit, “Modern Jam”. This subtle resurgence of the highly sought after sunglasses demonstrates how Peter Yee’s creative direction gave Oakley a long-lasting impact in the pop culture world.

On a wider scope, Oakley’s influence can be seen in other brand’s models, such as Balenciaga’s Swift Oval Sunglasses. This model was seen on

Kim Kardashian at the Vanity Fair Oscars Afterparty. After this event, sales for the model and accompanying dupes skyrocketed. Outside of this specific model, it is worth mentioning how Oakley’s original Factory Pilot Eyeshades inspired the majority of Pit Viper’s products. Additionally, the similarity in design and the company’s emphasis on athletes is reminiscent of Oakley’s brand image. Browsing through Oakley’s website, I noticed many products were sporting logos from the brand’s different eras. For example, the Hydra and ReDiscover Sutro use the brand’s first logo while the Holbrook, Gascan, and Fuel Cell models sport the brand’s newer logo which was introduced in 2000. Outside of logos, Oakley has reintroduced specific models, such as the aforementioned Eye-Jacket, M- Frame, and Wind Jacket. These models have been slightly redesigned and outfitted with Oakley’s newest technology, to better align with current design trends. The dynamic use of their logos and revitalizing old models demonstrates how Oakley is responding to the sentimental value which consumers place on familiar designs and logos. Through the examples of celebrities and competing companies, it is evident Oakley’s early designs have influenced present day consumers and the overall trend of nostalgia. Sunglasses are just an miniscule accessory when it comes to the fashion industry as a whole. Although there are many different brands and actors, nostalgia seems to play a big part in most brands’ items and marketing. For fashion houses, this means bringing back iconic designs or even specific clothing, like low-rise jeans. Brands are currently aware of the importance of nostalgia because consumers desire a sense of comfort, familiarity, and emotional connection with products and media. In a noisy world, nostalgia provides an escape for consumers to enjoy the products they coincide with familiar, positive experiences.

Oakley’s journey from its humble beginnings as a motocross grip company to its current status as a leading eyewear brand is a testament to the enduring power of innovation, creative direction, and the strategic embrace of nostalgia. The revival of iconic models, along with the dynamic use of logos and the incorporation of modern technology, showcases Oakley’s ability to adapt to changing consumer preferences while staying true to its roots. The influence of Oakley extends beyond its own products, evident in the designs of other brands and the broader trend of nostalgia in the fashion industry. As consumers increasingly seek comfort and emotional connections with products, Oakley’s strategic approach to incorporating nostalgia not only reflects the brand’s resilience but also underscores the timeless appeal of familiar designs in a rapidly evolving market. The Renaissance of Oakley stands as a compelling example of how a brand’s heritage can be a source of inspiration for both past and present consumers, creating a bridge between generations and leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of fashion and eyewear.

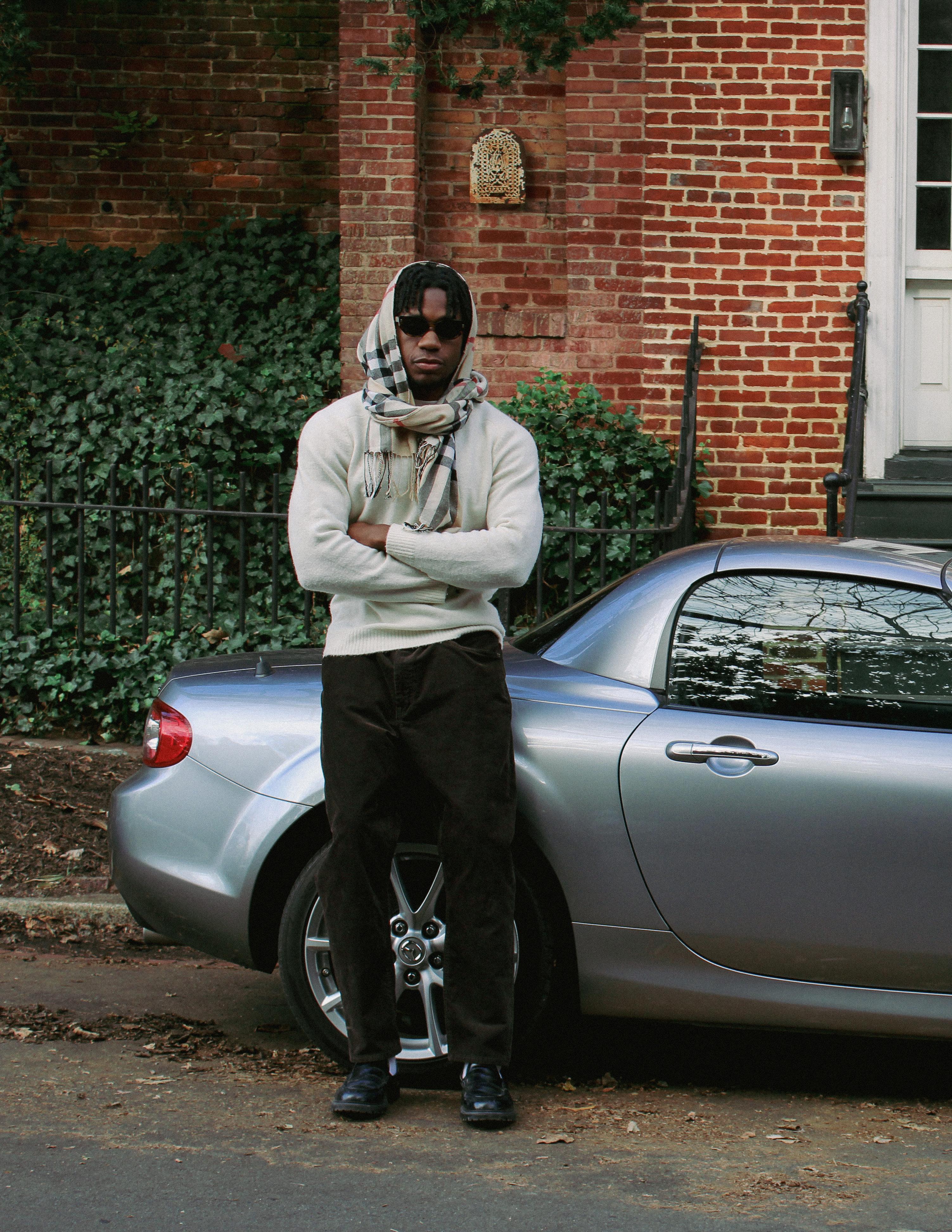

Declan Kelly, Noah Edelman

Photo by Ethan Valliath

Declan Kelly, Noah Edelman

Photo by Ethan Valliath

Eugene Rabkin unapologetically tells us the truth. After immigrating from Belarus to New York City as a teenager, a Wall Street career crisis and an exploration of independent fashion movements at luxury vanguards like Barney’s and experimental SoHo boutiques like If Boutique and Atelier New York, Rabkin established the StyleZeitgeist message board in 2006. He hoped to create a digital space for the kind of people that wanted to talk about the fashion that didn’t just exist on 5th Avenue or Avenue Montaigne. After StyleZeitgeist’s founding and success, Rabkin has gone on to also write for several major publications and interviewed fashion innovators such as Rick Owens, Ann Demeulemeester, Dries Van Noten and Haider Ackermann just to name a few. Between his regular contributions to the Business of Fashion or Highsnobiety, his own articles and magazine publications under the StyleZeitgeist banner and most recently his podcast, Rabkin has always provided a biting critique of the fashion industry at large. Thank you very much to Eugene for sitting down with me and providing your insights.

This interview has been edited down for publication.

BY ALEX MAROOTIAN

BY ALEX MAROOTIAN

AM: Tell me about how you became interested in fashion? Were there specific artists, musicians or personal events that influenced you to become interested in fashion?

ER: Yeah, definitely. My interest started, like for many teenagers, with dressing up. I came to the States from Belarus when I was 16 with my family. A huge part of many immigrant families is aspirational consumption, you come to the States for a better life. And obviously this is an age when you start caring about how you look. A lot of this has to do with sex and romance, trying to be attractive, etc. The person who was most influential for me was Trent Reznor, the singer and founder of Nine Inch Nails. When I saw the first video clip for March of The Pig, I really fell in love with Nine Inch Nails. Seeing something so raw and real was very eye opening to me. So he sort of became my style icon, not just wanting to emulate him mindlessly, but really, really being attuned to his music and lyrics and what he stood for. And at the same time my brother had a friend who was an aspiring designer, and he was really the only person I knew (who was into fashion) because we came from an immigrant Brooklyn neighborhood that will never be gentrified. He’s the one who saw my interest in dressing and he said well you should go to this store called Barney’s and I did. This was the first time where I discovered the Belgians and the Japanese, and I discovered that

Kyla Robinson, Abby Turner, Paige Nelson, Noah Edelman, Lucas Golluber, Samantha Travis, Sam Penzone, Abby Tuthill, Alex Marootian Photo by Ethan Valliath

there is fashion that’s not just about status display and conspicuous consumption. These clothes looked like what I’m wearing already, but just like infinitely better versions, much more elegant, much better made, much better fitting of course. And so that was my rabbit hole. And of course I was thinking “who are these people?” And why do they make clothes like that, and they must make clothes like that because they were into the same music that I was into. It was a very pure connection, a creator created something, and someone discovered it and you opened the dialogue through the clothes, which to me was full of meaning. It just goes to show you how insular the neighborhood I grew up in was, because I discovered Soho around the same time completely by accident. I prowled every single block of that neighborhood. I was like, “oh my god, this place was made for me.” I discovered stores there like the Helmut Lang boutique, which is still my most favorite store in the world. The original Comme Des Garçons boutique was still there before it moved to Chelsea, If Boutique, the Yohji Yamamoto flagship but it was all in between art galleries. Then later I discovered magazines like ID, Dutch, those were very instrumental to my education in the late 90s, early 2000s.

AM: What pushed you specifically into fashion journalism and starting StyleZeitgeist?

ER: Around 2003 or 2004 I was googling stuff on Raf Simons. In my search, this website popped up called The Fashion Spot, which was like the original (fashion) message board. I was really drawn to that because for the first time in my life, I met people virtually who were interested in the same clothes that I was interested in, the kind of people who knew who Helmut Lang or Jil Sander were. There were a lot of people on it, you talked to people like Susan Bubble before she launched her blog. I quickly earned the

reputation on The Fashion Spot for a) really knowing my avant garde and b) cracking jokes and firing off these one liners that were both a bit snide but funny. And so I became quite prominent there. And then eventually I thought, you know, I should start my own thing, why not? I really wanted to concentrate on design because The Fashion Spot was talking a lot about models and celebrity style and I was like I just want to talk about design. And that’s how StyleZeitgeist was born, as a message board and it attracted quite a lot of people. I kind of drove it but not really, because you can’t really drive a message board. It’s the community. At the same time, I had a career crisis. I was working on Wall Street, like a lot of Russian speaking Jewish immigrants do and I really, really hated it. So I went and got a master’s degree at The New School. I thought I was going to teach English literature in high school classes, that’s what I wanted to do. I realized that I wanted to write my master’s thesis about fashion. And at the same time as I was graduating, I got a message on StyleZeitgeist from someone who turned out to be an editor at the weekend magazine Haaretz which is the most prestigious Israeli newspaper. We were talking and I kind of blurted out, you know, I would love to write. So that’s how I started writing and then one thing led to another. Then I decided to start the StyleZeitgeist magazine and at the same time I met Imran Amed from Business of Fashion, I started contributing there and then it just snowballed. So StyleZeitgeist turned from a message board to a magazine, which was very timely, because the message board culture started dying because of Instagram and other social media (platforms). Then I launched the StyleZeitgeist podcast a few years ago, which I think was also very good. I’m glad because I’m never first to the finish line in terms of exploring new media but it seems like the podcast has sort of taken on a life of its own.

AM: You had mentioned the term avant garde before. What does that mean to you and is it a term that’s still

relevant for categorizing these very diverse artists over a 30 year timespan? Is it okay to call both Rei Kawakubo and Peter Do avant garde and is it a term that we should still use today?

ER: What I mean by the avant garde is the classic, modernist definition of the avant garde. It is creators who push the envelope, who introduce something new, who create outside of the norm, and who are basically pushing the conversation forward and pushing the limits of their respective disciplines. Yes, someone like Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, Rick Owens etc. Whether that is still relevant? That’s a fantastic question. I wish I had an answer for it, and I don’t have a definitive answer because I go back and forth on that. (There are) other people who are pushing the envelope. Iris van Herpen, designers like that, there’s a lot of pushing the envelope on the textile development side, materials, etc. In terms of aesthetic, I think that it becomes much harder in our thoroughly post modernist environment where so much has been done. And now it’s more about mixing what has come before rather than creating something genuinely new, which is not impossible, it’s just much harder. At the same time there are designers like Chitose Abe from Sacai, who is actually very avant garde, she created a new aesthetic right? But she’s not really avant garde in her thinking, she’s actually very commercially minded and supremely talented at the same time. And then of course there are fake avant garde brands like, not pushing the envelope at all, but they’re like, you know, “I’m the 50th version of Paul Harnden”. I wouldn’t call that avant garde at all. I would say the term is definitely fraught at this point, and I wish I had a clear answer, but I don’t, which is what makes it interesting. Is fashion art? I don’t know, I go back and forth on that. But that’s what makes it interesting because I haven’t made up my mind.

AM: What are your thoughts on independent creators on Tik Tok or YouTube discussing iconic designer collections or discussing these designers that were making collections before they were born? Do you think they’re actually interested in these designers or are they really just looking for the social media clout of guys in Rick Owens?

ER: Yeah. Look, technology is what you make of it. It’s really how you use this, would there be StyleZeitgeist if there was no internet? No, I would still be probably on the train to Brooklyn with a Barney’s bag so I would never knock it. I’m glad these platforms exist to spread the word. And there are absolutely real enthusiasts who run Instagram accounts. If you look at something like Archive PDF, these guys are genuine with what they do. Are there posers? I imagine there are, like I’ve said I don’t go on TikTok, but I know but I’m too old for this shit. My only reservation with social media and places like TikTok is an incredible amount of misinformation that goes on there. Yeah it’s great that you read one magazine article about Rick Owens, and now you go and tell people about it. But I guarantee you the amount of factual errors I’ve seen in magazine articles, including publications like The New Yorker,

these TikTok videos, Instagram stories whatnot, they’re also leading to a lot of misinformation. And to me, that is the biggest obstacle where I meet kids sometimes and they tell me stuff and I’m like this is absolutely, factually inaccurate. And another problem with this is that stuff creates its own ecosystem. So everyone just keeps spreading this misinformation where, you know, you see my background. I get my information from books where people really have done their research. Even sometimes my fact checkers when I write for publications are like “where did you get this we couldn’t google it.”. And I’m like yeah you couldn’t google it because it’s in a book and guess what that book is out of print. This is why you have me writing for you, because you can’t get this information anywhere else. So my biggest issue there is the amount of misinformation and alleging that is being spread. That’s one of the reasons why I started the Academy and one of the reasons why the first course of that Academy is the history of contemporary fashion. I would like to share my knowledge in a consistent academic environment, it’s a college level course. That’s my biggest problem. Am I glad these platforms exist? Absolutely, yeah, they should exist. And that’s how you learn. Especially, you know, I never forget where I come from. I didn’t live in Manhattan, I am not from an intellectual family. The internet is what allowed me to meet like-minded people, I’m all for it. Will a lot of passion and genuine and accurate information get lost in the vortex, of course, the problem will be about editing out.

AM: What do you think about the influence of reselling platforms like Grailed or Depop on this specific sect of archive fashion? Do you think it is a net negative or do you think there can be some positives to people doing this whole secondhand reselling of these pieces from iconic collections?

ER: Yeah, I think Grailed sucks, I hate it. And I’ve written about it on StyleZeitgeist, I gave an interview about it to the New York Times some years ago as well. I really think Grailed is the epitome of Oscar Wilde’s maxim that today everyone knows the price of things and no one knows the value of things. It has created this culture of low balling and this merchant mentality whereas in the days of forum classifieds; first of all it was a self selected community. Usually people who were passionate about fashion, and that created a community because you traded with people you kind of knew. Maybe you met them in real life, or you met them on the internet. But there was this aspect that went beyond merely transactional, which to me is still super important. This is why I sell my stuff on Instagram. Because it’s as important to me for something I’m selling to go to a good home as it is to get a price. Like I’ll take a discount just knowing that this piece means something with somebody. So I think Grailed engendered this transactional mentality. Oscar Wilde’s maxim was nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing. I think that’s the damage, where the clothes that are so imbued with meaning to me have just become another asset class. That is the thing that I find off putting.

AM: What advice would you give to a young designer or a young journalist or anyone that’s interested in accessing the fashion industry as a profession. This is such a large system, what can people do to help themselves but also stay true to not writing bad puff pieces for Vogue or something like that? What can people that want to work and contribute good work to the fashion industry do?

ER: Yeah, well, I hate to say it, my first inclination is always the same: don’t do it. Because it’s arduous and rewards are low. But of course, I’m not here to prevent anyone from pursuing their dream. I feel like in today’s day and age, probably the most direct thing is to develop your own thing. Journalistic jobs are few and far between, and it is very hard to make a living doing one. I would advise starting your own thing, and growing your own thing. I don’t have much advice for fashion designers, I do think that going to fashion school is important. Going to school in general is important. Because you don’t only learn skills, but you acquire a network, which hopefully you will use down the line. Then my other advice is you have to meet people. Yes, I’ve gotten work because of Instagram, just people DMing me. I’ve got some great connections, but people already know me. So as a starter meeting people is absolutely paramount. And also, let’s not forget the numbers. One big problem with America, we only hear stories about winners. But for every “ideservecouture”, how many kids are there that have their Instagram or YouTube channel and TikTok and nothing happens? So statistically, like any statistic would tell you don’t do it. But I don’t want to discourage anyone. I have a glass ceiling as well. So it’s not easy at all. What’s unprecedented today is that we do live in an age where the means of production has been absolutely democratized. And that can be a huge, huge boon. Yeah, but meeting people is key because emails, messages never work as much as meeting someone in person, which is hard because we usually have to live in one of the cultural capitals which is also expensive.

AM: That’s all the questions I have. Is there anything else you’d like to add or any final thoughts to give?

ER: My final advice is don’t be daunted. I don’t want to say anyone can do this. But I will say that anyone who has the passion and the curiosity and intellectual curiosity can do this. I came from a place of nothing to a place that was also of nothing. But I was very driven and on some level, like autodidacts are my favorite sort of American success stories, because this country is very adamant about not educating its people. But it doesn’t stop you either. I’ve met quite a few autodidacts and they’re actually my favorite people, because they’re driven. I would say don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t. Because knowledge is acquirable, it just takes effort and time.

AM: Thank you very much Eugene for giving me your time.

Lucas Golluber, Kyla Robinson

Photo by Ethan Valliath and Sarah Strausberg

Lucas Golluber, Kyla Robinson

Photo by Ethan Valliath and Sarah Strausberg

“Grailed is the epitome of Oscar Wilde’s maxim that today everyone knows the price of things but no one knows the value of things.”

When it comes to the artisanal fashion scene, Maurizio Altieri’s Carpe Diem was among the first to establish a voice that touted craft, simplicity in design and truly upending many preconceived notions of “luxury” fashion. A pure celebration of quality materials and small batch production, Carpe Diem helped establish a unique look at daily dress. From totally singular leather offerings to timeless wardrobe staples, this brand of Italian fashion flew right in the face of glossy photoshoots, sleek suiting and stylized embellishments. I had the privilege to speak with Alessia Righi Amante, a central part of Carpe Diem’s creative team. We talked about her start at the brand, what made Carpe Diem successful and its eventual closure in 2006. Thank you very much to Ms. Amante for sharing your experiences with me.

AM: Take me back to when you were at Carpe Diem. How did you start working there, how would you describe the brand, its place in fashion history and its eventual closure?

AA: I met Maurizio Altieri in 1996 or 97 by chance, my ex husband told me “I met someone you have to know” and I met him. I was designing and selling jewels at that time. Meeting Maurizio was a sort of illumination, I never met anyone like him… he was a sort of a shaman, a wizard, a storyteller. I did visit his studio and I fell in love with his work, so raw, primitive, unique simply and perfect. He did only leather clothing and shoes at that time, oh my god the shoes, they were addictive, once you started wearing them you couldn’t wear anything else.

They were not comfortable at all but they looked amazing and totally different, you had the feeling to be different in a pair of Carpe Diem shoes.

At the time I visited his studio in Rome he told me “we’ll change it all”, it was just the second time I met him. He had the rare talent of immediately recognizing people’s potential and pushing them to the maximum so they could express it. This is the way everything started. We were short of money, we worked for the pleasure of it, I kept my job with the jewels company for years before being stable at CDiem. We moved from Rome to Perugia in a very small space nearby the factory who made our clothes, his style at the very beginning was a bit close to Chrome Hearts. He spent some time in LA with Richard and the crew, but then he found his own way with raw hedges, distressed leather, unisex pieces, clothes as uniforms, double layers, reversible jackets, it all seems so obvious now but then it was new and exciting. I used to buy Margiela, Helmut lang, and Ann for myself but this was a step forward.

A couple of years later, business started to work out, we had the best customers in the world back then, we moved in a huge space, new people joined our team, we were like a rock band playing our own music. Everything seemed to be possible; customized, amazing, crazy expensive leathers and fabrics, we started l’Maltieri, the fabric clothing collection, and then Linea, with a much more minimal approach to fashion based on the simple concepts of light, medium, heavy weight and light, medium, dark colors…we also opened an experimental space in Paris called x18, nearby Canal St.Martin. It used to be a garage, it became our home, workspace, a new dimension. We used to communicate with the motherhouse in Perugia through a very complicated video conference system built inside a 12 meters container installed in the center of the space, kind of Facetime or Teams grandfather.

But then everything crashed down, not all in a sudden, I felt it but maybe I did not want to see the evidence, Maurizio was not into it all anymore. CDiem got too big, too “famous”, too much intrusive, he could not stand with it anymore. He needed to find other possibilities, to explore different ways to express himself and we got to the end. I can say now, looking backward, it had been one of the best times in my life. I met incredible people, amazing souls Yoko Ito, Maurizio Amadei, Anna Blessman, Vivetta, Luca Laurini, Simone Cecchetto, Emanuele Colella, Massimo Degli Effetti, Sarah Stewart, Tommy Perse, Kurt, Sofia, Alda, Anna Meris, Peter Sidell, Darius Chegini, to name a few.

AM: Thank you Ms. Amante for giving me your time.

Whether it’s a reflection of financial shifts akin to the George Taylor hemline index, or of a desire to dress like you’ve married a Windsor, Gen Z has found a new infatuation with quiet luxury and quality pieces and deemed it “Old Money”. The lifestyle of inheritance is a virtually unattainable lottery, but it seems that Gen Z also finds it relatively undesirable; all they desire is the look itself. The trend stems from a return to sustainable, reliable basics from quality brands such as Ralph Lauren, Burberry, Brooks Brothers, Loro Piana, and Chanel likely originating from the elegantly casual looks of European elite and royalty. Such brands were worn casually or recreationally, like Polo Ralph Lauren which was initially inspired by Lauren’s interest in sports and sportswear. Thanks to the nature of the sport, Ralph Lauren clothes were manufactured to be timeless and durable, and we can attribute the continuity of its popularity to this notion. Similar labels also focused on durability and style, guaranteeing quality materials and timeless silhouettes, though for a higher cost.

Quality brands have been, and continue to be, resonably expensive for everyday wear, so why is the generation paying college tuitions and job-hunting so immersed in the aesthetic? Many find the look to be the appeal: simple accessories, timeless silhouettes, muted and jewel tones. Recently, the uptick in thrifting and buying secondhand has delivered greatly on the affordability front. It’s simple to go to your local Goodwill or flea market and find a previously worn Ralph Lauren sweater, and as long as it isn’t host to a questionable stain, one wash makes it good as new. Whether they’re name-brand finds or look-alikes, thrifted pieces are a sustainable and affordable way to achieve the “Old Money” look. This may also be a testament to the durability of “Old Money” brands, having survived years of wear by previous owners. But durability is not the aesthetic’s only appeal.

The trend is also wildly popular due to the nature of it being less “flashy”, in which a more subtle display of sophistication is preferred to flaunting name-brand pieces just for the sake of flaunting them. This obsession with name-brands, or “logomania”, began in the early 1980s and reached a final height around 2016 after Louis Vuitton’s Spring show. Though its reign in the ‘80s and ‘90s was iconic and ever-present in certain elements of modern fashion, logomania is slowly being replaced by a desire to boast quiet luxury, rather than obvious opulence. Many people draw this inspiration not only from the style itself, but also from fashion icons of yesterday

and today.

When it comes to icons of quiet luxury and “Old Money”, the People’s Princess is the choice of many thanks to her casual but sophisticated street style, not to mention her legacy in the Royal family. Today, many find inspiration in Princess Diana’s simplistic style, like model Sofia Richie. After her stunning dream-wedding the internet was buzzing, and praised her elegant and timeless style. Her stylist, Liat Baruch, revealed that the trick was not to overdo it with a flashy bag or excessive jewelry. Her go-to look for Richie features the classics: a button down, highwaisted jeans, a plain white tee, and a contemporary but timeless accent piece à la a unique shoulder bag or cutout midi dress. Dani Michelle, stylist for Kendall Jenner and Hailey Bieber, also emphasizes that the importance of “quiet luxury” is all in the details; elevated accessories revive an outfit without detracting from its simplicity. In general, it seems that the motto for “Old Money” fashion is certainly “less is more”. The “Old Money” motto, however, is remarkably in line with the motto of minimalism, and it’s important to recognize where the two differ. The move to minimalism began in the late 1980s and ‘90s, replacing ‘80s maximalism with more sleek, simple designs. Designers like Calvin Klein, Georgio Armani, and Jil Sander found minimalism to be at the heart of their designs. Jil Sander, a European fashion designer hailing from late ‘60s Germany, was particularly transformative during this period of ‘80s and ‘90s minimalism. Her designs enhanced basics and gave them life in the fashion world; a white button-down and a neutral structured coat went from off the rack consumer goods to runway fashion. Her minimalist designs may have lacked “Old Money” prestige and tradition, but the quality and sophistication of her work never fell short. In later years, Phoebe Philo would transform Celine in a similar way. From 20102018, Philo focused on tailored, monochrome looks which varied in texture and pattern, taking women’s daywear to a new level. Brands like The Row would follow, taking inspiration from Philo in an attempt to create cosmopolitan women’s attire that mirrors ‘90s minimalism and quality.

Similarly, minimalist Paris-based brand Lemaire creates pieces that are modern yet classic and ever-changing to suit the trends of the moment. Their minimalist values are held in the timeless designs of their pieces but enhanced by modern, unique twists. What the aforementioned brands and “Old Money” designers have in common is undoubtedly their emphasis on quality and simplicity. Whether you’re buying from Chanel or The Row, you’re guaranteed to be met with durable designs that

exude sophistication. Where they differ, however, is in prestige and intent. “Old Money” conveys not only wealth, but tradition and class. Such brands try to maintain vintage designs, material, and colors, while modern minimalists work to transform such designs. Regardless of their differences, minimalism and “Old Money” continue to fluctuate in and out of fashion, and it’s clear that they’re both making comebacks. In particular, there are several “Old Money” pieces that have risen back into popularity in recent years. The kitten heel has become a staple piece in many wardrobes due to its versatility and comfortability. The style, popularized in the 1950s, is more demure and simplistic than many of the trendier stilettos and chunkier heels present in fashion today. The shoes flowed in and out of popularity during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, naturally, due to their wearability without having to sacrifice sophistication. Flats are also reemerging into fashion for similar reasons. Perhaps their popularity is due to the “balletcore” trend that’s taken off in recent months, which everyone from designer to retail brands have jumped on in clothing and footwear.

Quiet luxury has also manifested itself in the form of minimalist, timeless bags. Neutral-toned leathers, quality hardware and simple designs all add to an outfit in an understated but luxurious way that trendier, flashier bags are not able to harness. A simple bag will always be in style; from Banana Republic to LOEWE, it’s impossible to avoid finding a unique but timeless clutch or tote for every occasion. In union with minimalist bags, elegant scarves are also making a bit of a comeback, now that Gen Z has recovered from their days of infinity scarf trauma, and not only are they functionable, but they’re extremely fashionable. One can never go wrong with a classic Burberry tartan-check scarf, a subtle yet distinct display of “Old Money” elegance and craftsmanship. However, thrifted or vintage scarves are gaining popularity due to their elegant patterns and versatility when it comes to styling. Whether you’re using scarves to cover your hair in a 1950s Hollywood way, or adorning your classic leather shoulder bags with them in a Birkin-esque manner, vintage scarves give anything that “Old Money”, European flair. On the accessory front, Cass Dimicco, founder of Aureum Collective, explains it best. Accessories should be chosen with care and consideration, as they are meant to be long-term investments that you benefit from by wearing them every day without having them tarnish or break. Pieces should be elegant and timeless, and should complement just about everything in your wardrobe. This is what “Old Money” is all about: pieces that will never go out of style and can be worn and re-worn

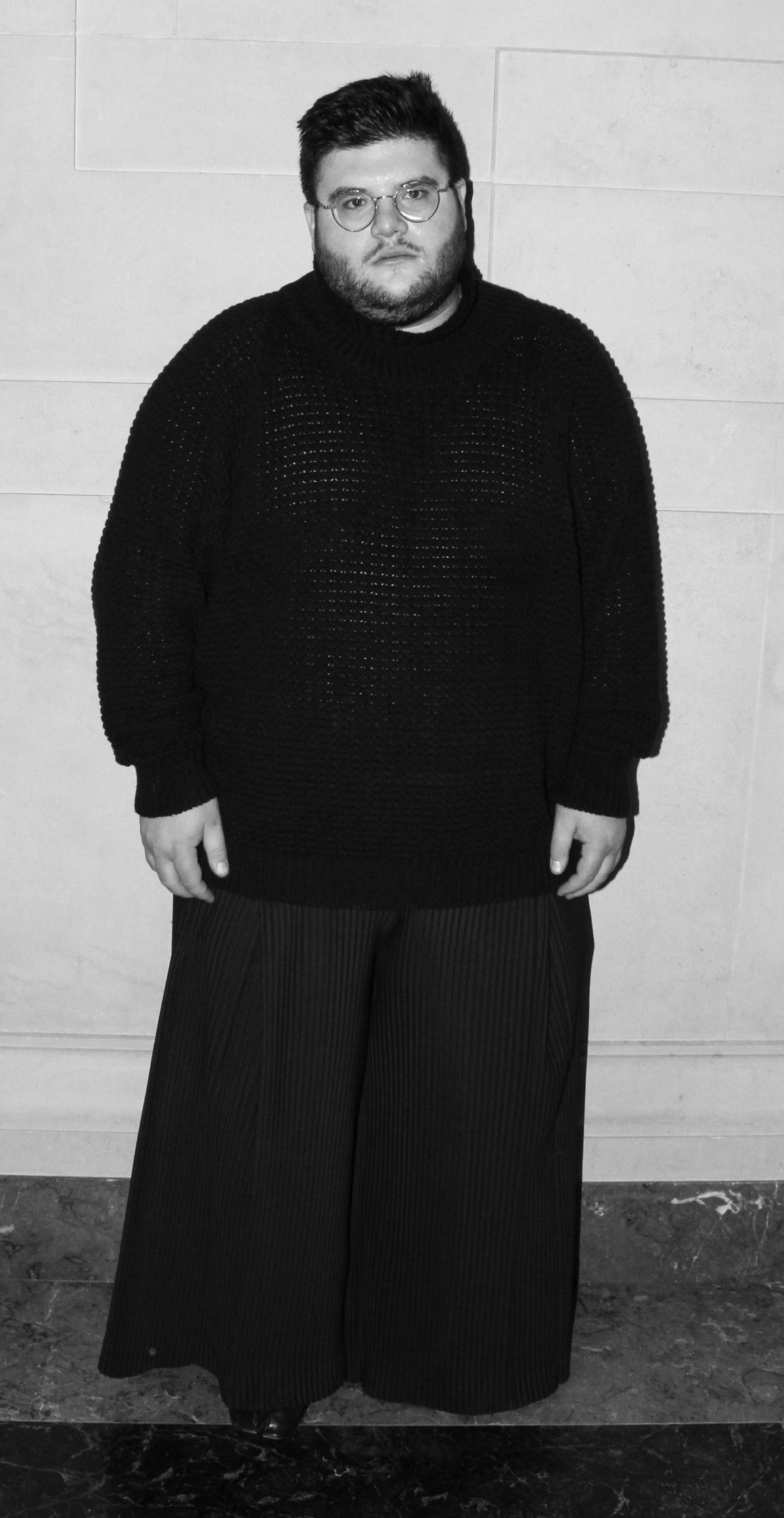

Philippe Tchokoam

Philippe Tchokoam

Eliza Thorn, Phillippe Tchokoam, Andrea Pedemonte

Photo by Ethan Valliath

Eliza Thorn, Phillippe Tchokoam, Andrea Pedemonte

Photo by Ethan Valliath

a hundred times before they show any wear and tear. In particular, luxury brands such as Tiffany and Co, Cartier, Bulgari, and Van Cleef & Arpels have significant historical notoriety among the rich, but still remain relatively popular as once in a lifetime investment pieces. They emphasize the classic design and versatility of “Old Money” fashion when it comes to jewelry, and represent hundreds of years of deeply rooted fashion history.

So, why does Gen Z have such an infatuation with Old Money”? The reality is that the obsession itself is a trend; fashion is constantly fluctuating between out-of-the box style and back-to-basics, and right now many are more appreciative of simplistic style, unlike former fast-fashion trends. However, the reasoning behind wanting a wardrobe that is sustainable and timeless is solid; you want to get the most out of your purchases, so why not make them something that will never go out of style? Quiet luxury will always be at the baseline of fashion, whether it goes by “Old Money” or “minimalism” or whatever TikTok wants to call it, and the emphasis on quality craftsmanship and timeless silhouettes is something that goes much further than a logo.

Eliza Thorn, Phillippe Tchokoam

Photo by Ethan Valliath