city_lights

a3: creative project

sem 2, 2021

george rowlands-myers

758020

a3: creative project

sem 2, 2021

george rowlands-myers

758020

Translucent, distorted, the version of real, The memory of a physical space, Inserted within the image surreal, The film as container of data; its base.

A culture collage, an experienced moment, The feeling of change, the contrast on tape, Collected from different temporal points, The image is still while the story’s in pace.

The film - an archive with multiple folders, The city, meanwhile, is its library maze. And what is for us, we are pages in order, The moment in future; the story in place.

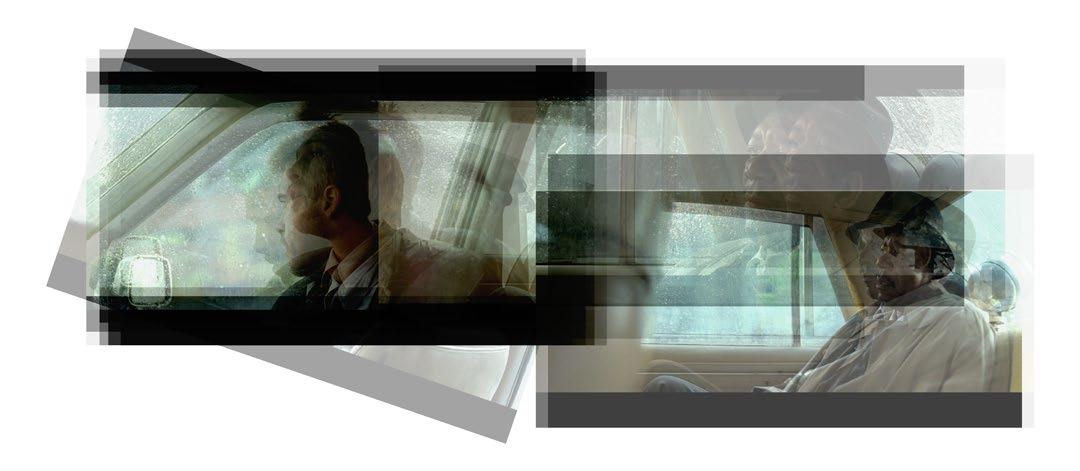

This digital book comprises a series of photographic collages and accompanying poetic narration which seeks to graphically explore the idea of the film as a cultural record of the lived-in moments of their respective cities.

These works have been created using photographic materials available from a series of films shot within two of Hollywood’s most explored cities – New York and Los Angeles - arguably the cities that have been most experienced around the globe through the lens of cinema.

The collages aim to communicate the diverse wealth of experience and exchange that can be lived within the city, as well as explore the dynamic combination of time, movement, and memory that inhabits the places of their respective imagery.

Within his 1974 novel Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino proposes the idea of the imaginary city; a fragmentary collection of moments that comprise the true cultural essence of their respective city. Within this concept, Calvino’s narration incorporates a ‘continual blurring between the traditional distinctions between past, present, and future in a scenario where they overlap into each other’, thus suggesting the idea that the essence of a city is unbound by either time or physical limitations2

A physical record of a collection of moments, the medium of cinema may offer audiences a glimpse into the recorded lives of a individuals within the wider narrative of the city. Audiences virtually go to these places as a passive byproduct of the cinematic experience – ‘films allow the viewer to experience a wealth of sensations that can be part of a destination.3’

‘The perfect city is put together with separated by intervals discontinuous scattered, now more condensed.1' – Italo

1. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, (1978), 164.

2. Sambit Panigrahi, “Postmodern Temporality in Italo Calvino’s ‘Invisible Cities.’” Italica 94, no. 1 (2017), 82.

3. Ariane Portegies, Places on my Mind: Exploring Contextuality in Film in Between the Global and the Local, Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, (2010), 47.

If we apply Calvino’s allegorical city concept to this, the cinematic medium may be viewed as this collage of fragmentary moments - with several films set within a singular place contributing to the collage of a city. In this sense, cinema becomes a memory database, and the city is its library.

What results is a memory collage of the city – an imaginary city; both deformed and freed from its physical nature by the subjectivity of film; becoming ‘an emblem that demands to be deciphered.4’

The city and its streets are the physical vessel that house the experience of film, with the medium’s inherent experiential qualities enabling the recording of a memory more closely resembling the cultural character of its place that is otherwise difficult to communicate.6

4. Carol P. James, “The Fragmentation of Allegory in Calvino’s Invisible Cities.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction 6, no. 2 (1986), 88.

6. Francois Penz, Cinematic aided design : An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture (Routledge, 2017), 132.

‘The quantity of things that could be read in a little piece of smooth and empty wood overwhelmed Kublai; Polo was already talking about ebony forests, about rafts laden with logs that come down the rivers, of docks, of women at the windows.5'

– Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities.5. Calvino, Invisible Cities. 132.

In his film The Man with the Movie Camera (1929), Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov documented soviet urban life using a combination of fictional surrealist imagery and documentary techniques, determining that ‘the human eye was inadequately equipped to record the complexity, the multiplicity and the simultaneity of contemporary life,’ thus creating a film situated somewhere between ‘the reconstructed celluloid city and the actual urban terrain.7’

It could thus be said that ‘Moving images possess a comparative advantage over other expressions in preserving and communicating the spirit of our times. These enable the construction of a counter-history, an unofficial history…contributing to the formulation of our historical consciousness.8

THE STREET IS AN INTERSECTION OF NARRATIVES

A city involves a million narratives that cross paths - each person has their own particular story – where and when they interact dictate the nature of their story – their own film. Contrasting films between different genres renders the city as a character itself influx – and displays its capacity to contain narratives of vastly different nature.

The same apartment may house the possibility of a neighbour concealing the murder of his wife or a dinner between work colleagues almost 50 years later. A police investigation in Seven (1995), or a conversation with a passenger in Taxi Driver (1976) may all inhabit the same urban space at varying temporal points, becoming moments contained within the memory database of the collaged city.

A FAMILY GATHERING

The subjectivity of both film viewing and its direction naturally lends itself to the idea of a city comprising of millions of inhabitants, all with varying perspectives that experience the city in their own unique way. Cities experienced through many different films create this approximation of a real place that lives within the cultural collective consciousness – an imaginary city of memory9

THE CITY IS ALIVE BEHIND US

Indeed, ‘films of particular places colour the expectations of inhabitants and visitors. Sightseers in London see the city through the lens of Passport to Pimlico (1949) and Alfie (1966)’, therefore showing us that ‘urban experience colours our experience of film and film influences urban experience10

Further, the imaginary city may supersede the experience of its physical counterpart through sheer quantity of cultural exposure; ‘in an age of mechanical reproduction, the status of memory changes and assumes a spatial texture. Both personal and collective memories lose the(ir) taste…and acquire the sight/site of photographs and films11

In his chapter for Cinematic Urban Geographies, Professor Richard Coyne asserts that ‘To think of the city as film is to assume that our lives occupy the horizons of a film, as if staged, directed, and dramatized, and where emotions are orchestrated, managed, appraised and interpreted.12’ This more melancholic view may be counteracted by a more uplifting interpretation;

If the city is a memory archive and film is its medium, then we are ourselves characters in a narrative.

The idea of an orchestrated narrative should be rejected however, as it neglects the city’s nature as a living, breathing character comprised of a thousand fragments of memory and intersecting narratives. As noted by Rushdie, ‘The city…refused to submit to the domination of the cartographers, changing shape at will and without warning.13’

Our singular moments contribute to the collage of memory that we all inhabit. A conversation we have in a café, or a stroll with a friend through the streets –these may become scenes of some future story – a record of a city’s life.

Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Fox, Kenneth James. “Cinematic Visions of Los Angeles : Representations of Identity and Mobility in the Cinematic City,” January 1, 2006.

James, Carol P. “The Fragmentation of Allegory in Calvino’s Invisible Cities.” The Review of Contemporary Fiction 6, no. 2 (1986): 88–94.

Panigrahi, Sambit. “Postmodern Temporality in Italo Calvino’s ‘Invisible Cities.’” Italica 94, no. 1 (2017)

Penz, François. 2017. Cinematic Aided Design : An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. Routledge.

Penz, François, and Richard Koeck. Cinematic Urban Geographies. Screening Spaces. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Portegies, Ariane. Places on my Mind: Exploring Contextuality in Film in Between the Global and the Local, Tourism and Hospitality

Planning & Development, (2010) DOI: 10.1080/14790530903522622

Martins, A.I.C. “Invisible Cities: Utopian Spaces or Imaginary Places?” Revista Archai: Revista de Estudos Sobre as Origens Do

Pensamento Ocidental, no. 22 (January 1, 2018): 123. doi:10.14195/1984.

Rushdie, Salman. The Satanic Verses. 1st American edition. Viking, 1988.

Taxi Driver (1976), Columbia Pictures. Rear Window (1954), Paramount Pictures. Seven (1995), New Line Cinema. Rebel Without A Cause (1955), Warner Bros. Pictures. Blade Runner (2017), Warner Bros. Pictures. The Man with the Movie Camera (1929), VUFKU. Alfie (1966), Paramount Pictures. Passport to Pimlico (1949), General Film Distributors UK.

Student work. Not for Profit. All rights belong to their respective owners.