30 APRIL – 24 JULY 2022

HURSTVILLE MUSEUM & GALLERY

Our Journeys | Our Stories is a ground breaking exhibition for Hurstville Museum & Gallery.

As a converged facility – both a museum and a gallery – this marks the first time our exhibition space will simultaneously reflect our two halves. Often alternating between a social history (or ‘museum’) exhibition and a visual arts (or ‘gallery’) show, this exhibition showcases the full potential of a combined facility, as we present side by side the history of Chinese migration to the area accompanied by artworks responding to the themes and objects on display.

Our Journeys | Our Stories explores the Chinese migration history of the Georges River area, interweaving social and cultural history with the work of contemporary Chinese-Australian artists Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen, Guo Jian, Lindy Lee, Xiao Lu, Jason Phu, and Guan Wei. This exhibition aims to highlight and celebrate the significance of local Chinese migration from the 19th century through to the 2000s and the ongoing contribution of the Chinese community to the Georges River area.

At the heart of most cultural institutions is storytelling, and one of Hurstville Museum & Gallery’s strengths is its local focus and passion to tell the diverse stories of the Georges River community. Create Georges River, Council’s Cultural Strategy, highlights the link between culture and place, exploring how our community’s activities, backgrounds and beliefs impact upon the place where we live. The Georges River area is a culturally rich place, and this exhibition demonstrates the value of cultural exchange.

To our community lenders and oral history participants, thank you so much for trusting us to share your stories. It is these personal accounts and memorabilia that demonstrate

the long-lasting impacts of migration, not only in your personal lives, but on the social fabric of our area.

To our artists and their participating galleries, thank you for your support and enthusiasm for this exhibition. I am honoured to have each one of your works included in the show and to have heard how the narratives explored inspired your creative processes.

To the cultural institutions and funding bodies who have supported us, thank you for opening your collections to us and seeing the value in what was an ambitious dream that has turned into an amazing reality.

Finally, to Hurstville Museum & Gallery curators, Claire Baddeley and Renee Porter, you should both be immensely proud of this exhibition. Claire, you researched and listened with care to our local community, revealing fascinating stories and objects that tell the history of Chinese migration to Australia and our area. Renee, you worked so hard to achieve the artists on our wish list, and in turn have helped shine a light on the work done here at Hurstville Museum & Gallery.

I hope our visitors enjoy uncovering the connections between the artworks and history, and leave this exhibition with a deeper awareness of the longstanding and continuing connection the Chinese-Australian community has with the Georges River area.

Bethany MacRae Coordinator Cultural Services Hurstville Museum & Gallery《我们的旅程·我们的故事》是好市维博物馆&画廊举办的史无前例的展 览。

本机构是博物馆与画廊的二合一,本次展览标志着我们的展览空间首次同 时展现本机构的两个部分。展览交替展出了社会历史(博物馆)和视觉艺 术(画廊),展现了本融合机构的全部潜力。展览同时展示了该地区的华 人移民史和与展览主题相关的艺术品和展品。

《我们的旅程·我们的故事》探讨了乔治河地区的华人移民史,同时将社 会文化历史与当代澳大利亚华裔艺术家曾苑慈、郭健、李林迪、肖鲁、符 子龙和关伟的作品交织展出。本次展览旨在强调并赞扬 19至 21世纪当地华 人移民的重要性,以及华人社区对乔治河地区的持续贡献。

大多数文化机构的核心都是叙事,好市维博物馆&画廊的优势之一就是对 乔治河社区当地的关注以及讲述多元故事的热情。市议会的文化策略“创 意乔治河 ” 强调文化和地区之间的联系,探索本社区的活动、多元背景和 信仰是如何影响了我们生活的地方。乔治河地区是一个文化丰富的地方, 本次展览展示了文化交流的价值。

我谨在此感谢社区中慷慨出借展品的人士,并感谢口述历史参与者的信 任,允许我们来分享你们的故事。正是这些个人记录和纪念品,展示了移 民对个人生活和本地区社会结构的长远影响。

我也要感谢各位艺术家和参与展出的画廊,感谢你们对本次展览的支持和 热情。我很荣幸各位的作品能在本次展览中展出,并且有幸了解各位如何 探索叙事方法、启发创作过程。

感谢支持我们的文化机构和出资机构,感谢诸位向我们开放了你们的收 藏,看到了雄心勃勃的梦想转变为美妙现实的价值。

最后祝贺好市维博物馆&画廊的策展人克莱尔·巴德利和蕾妮·波特,两位都 一定为本次展览感到非常自豪。克莱尔对本地社区进行了研究调查和认真 聆听,发现了讲述澳大利亚华人移民史以及本地历史的精彩故事和物品。 在蕾妮的努力下,我们能预定到预期中的艺术家,并帮助增加大家对好市 维博物馆&画廊工作的理解。

我希望观展者乐于去发现艺术作品与历史之间的联系,并在观展之后对澳 大利亚华人社区与乔治河地区长期持续的联系有更深的认识。

A history focused on a single location such as the Georges River area enables the teasing out of much that is unique and individual, allowing locals to understand some of the complexities of history to be found perhaps in the family living just next door. However, history is context and only with a broader understanding can we appreciate why individuals such as Henry Bing Lee, Gable Sheung Chun Yip, Sun Tiy Sing and others who appear in this exhibition lived and acted as they did. Market gardens, cafes and fruit shops may be the obvious face of the local Georges River Chinese community, but much more occurred beneath the surface.

What could be simpler (or more complex), than a history of Chinese migration in Georges River? Especially one supported with images and artist’s interpretations? What could go wrong? Nothing at all in fact, so long as we accept that history always gets it wrong. Historical interpretations and associated exhibitions can only hope to suggest the complexity of individuality and context, networks and links, perceptions and myth-busting, needed to understand our past. Nevertheless, let’s do our best.

‘Chinese’ would appear to be an easy first step – people from China, right? Except that the first peoples to arrive in the Australian colonies in any number from ‘China’ in the 1840s did so from the Empire of the non-Chinese Manchu and were mostly Fujian speakers recruited as indentured labourers through what was then referred to as the port of Amoy (Xiamen). These first ‘migrants’ were then greatly surpassed in numbers in the decades after by thousands of men (scarcely any women) from a handful of counties around the Pearl River Delta who came seeking gold, just as thousands did from Europe. These men travelled more freely, even if often owing money for their tickets, via the newly established British controlled port of Hong Kong. These ‘Chinese’ spoke an entirely different language from those of Amoy (occasional fights highlighting

this division), while even among these people of ‘Canton’ (aka Guangdong) numerous dialects and even language divisions also existed. This also led to disputes on occasion, but more often separate networks of support and business, and even preferences as to which colonies they tended to ‘migrate’ to, and certainly who their daughters married.

All this took place, including the enactment and then repeal of a number of anti-Chinese immigration measures, before the Georges River area began to become the residence of an increasing number of people generally labelled ‘Chinese’ in the 1870s. (As well as some earlier fish curing industries on Botany Bay). By this stage a new generation of people from the Pearl River Delta villages were arriving in numbers, numbers that would greatly increase in the 1880s as tin mining grew more lucrative leading to a renewal of anti-Chinese immigration restrictions. More rural than urban, successful business networks were established, temples built while others converted to Christianity. Entertainment included Chinese opera as well as the better-known gambling. For those taking up market gardening in the then outlying districts of Sydney, it was a matter of continuing the now generational links with the British colonies as fathers retired and sons were sent in their turn to earn income for the families in the villages of south China.

It is this continuing link over generations with extended families located in the home village or perhaps later in Hong Kong, networked via dialect and district businesses and organisations that is an essential context to Chinese ‘migration’ from the 19th through to the second half of the 20th century. A networking and movement that requires us to rethink ‘migration’ as not the simple one-way new settler process it is for some. Certainly, many people from the Pearl River Delta did just that, while some retired to the villages, others were taken as children to be raised there before returning again, and still others married or re-married and raised families in more than one location and culture.

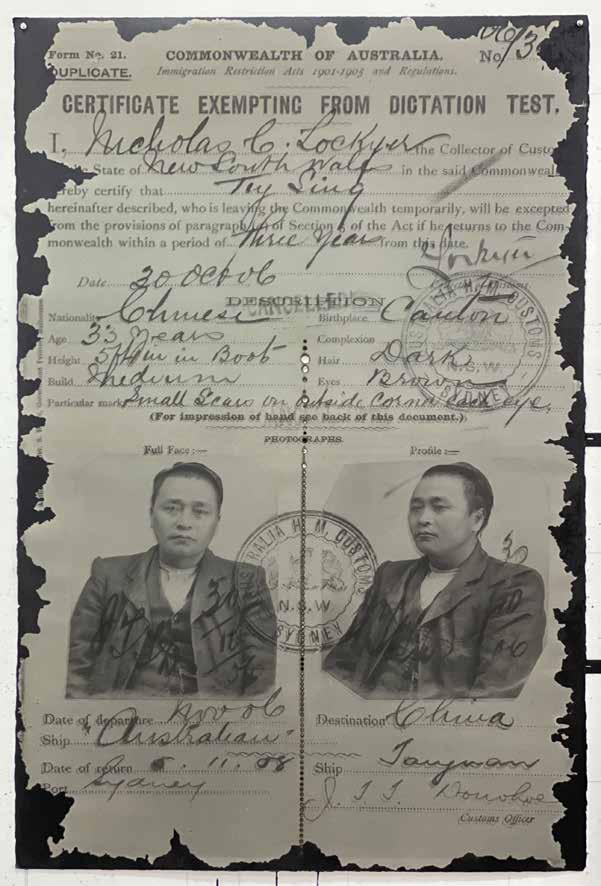

All this living and working was of course made more complicated by the racist White Australia policy with poll taxes that increased the debts some began their life in Australia with, and which after 1901 imposed the infamous fake Dictation Test. Giving people tests in European languages such as Estonian was designed to reduce the numbers of non-whites in Australia and made it difficult for many of the relatives of those in Australia to continue their links. It also made life difficult for even Australian-born people of Chinese heritage who found themselves needing to get exemptions to this test to travel – something ‘white’ Australians never did. Yet while this racist perspective often dominates the history it needs to be balanced with two considerations – agency and whitewashing.

Too great a focus on the discriminations of White Australia – as undeniable as they are – neglects the strength of the Chinese family and business networks which allowed people to continue to support their families, educate their children and maintain their networks despite the racism. Casting Chinese Australians in the light of perpetual victims is in fact one of the legacies of the White Australia policy; while the other is a whitewashing of Australian history. It is this second consideration this very exhibition helps to counterbalance as we learn to understand that Chinese people have been contributing to Australia for many generations and that much of their contribution has been too simplistically reduced to that of market gardeners and victims of racism.

In fact, far from the White Australia faddists dominating, it is changes in China and the wider world that had the greater impact on this history. War and Japanese invasion caused many to prefer Australia over the hazards in Hong Kong and south China, including fresh arrivals as refugees, many of Chinese origin. These new arrivals, added to increased sympathy as Australia allied itself with China against the Japanese Empire, saw the first cracks in the White Australia policy. The result was a new generation of Chinese Australians able and willing to move into a broader range of businesses and jobs than ever before.

After 1949 even greater changes began as the new government in China imposed policies that raised barriers to the old links between the Pearl River Delta villages and those overseas. Even those wishing to retire often chose to remain in Australia. Chinese Australian families began to find Chinese cookbooks available to assist them adapt to local ingredients as well as introducing the broader Australian community to Chinese

cuisine. Many people fled to Hong Kong and from there took up some of the few avenues available to enter Australia – cafes and students. The continuing White Australia policy, while reluctant to recognise a refugee situation in Hong Kong, did recognise Chinese Australian cafes as a legitimate place for ‘Chinese’ employment so the number of such eateries expanded. At the same time, it became gradually easier to sponsor students and an increasing number of young Chinese people arrived in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s to study.

The great difference in the post-war period is that while many people and students who arrived via Hong Kong originated in the Pearl River Delta and continued the old family and dialect links of the past, many more people began to arrive from the wider Chinese diaspora; for the wider context of Chinese migration has always been that those coming to Australia were only a small fraction of those who travelled to South East Asia as well as around the Pacific. Chinese people in the nations now independent as the European colonies ended, often found themselves discriminated against. And so Chinese people, mainly from Singapore and Malaysia, began to enter Australia, very often as students and increasingly as university students. This new generation of people is often associated with the Colombo Plan, something governments anxious to avoid a backlash as the White Australia policy was increasingly subverted, happily promoted. The reality however is that for every one student arriving under the Columbo Plan three were selffunded, and a great many of these remained in Australia to take up the citizenship that only after 1957 was possible for Chinese and other non-white people.

Numbers arriving remained small until the final dismantlement of the White Australia policy by the Whitlam government in 1972 and the acceptance by the Fraser Government in 1976 of the first ‘boat peoples’ after the reunification of Vietnam. Once again many of those from South East Asian nations, this time Vietnam and Cambodia, were people of Chinese heritage. It is only at this point that the gender imbalance that had always characterised Chinese migration to Australia was finally restored. Though in the final years of the White Australia policy many of the former students had been able to marry and bring spouses from Hong Kong and elsewhere.

In the 1980s two significant changes began to transform the history of Chinese migration to Australia once again. One was domestic as the Australian government converted the education sector into a fee for service enterprise, at least as far as overseas students

were concerned. And the other was to be found in China as the reforms of Deng Xiaoping set the stage for the rapid growth of a Chinese middle class and the evolution of a new generation of students willing and able to pay the fees for Australian university entry. All this took a dramatic turn in 1989 as a massacre of students in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square and the Hawke government’s response resulted in some 40,000 young well educated people taking up residence from China. In addition to their age, gender and numbers, it was also significant that they were overwhelmingly Mandarin speakers and from many locations around China, other than the Pearl River Delta.

The early years of the 21st century has seen increasing migration from China itself once again predominate over other sources. More middle class and educated, and many former students, their numbers are now bringing the overall ‘Chinese’ community of Australia up to proportions not present since before the introduction of the Dictation Test in 1901. This is a community long represented in the Georges River area and enriched by the many contributions of its Chinese migrants from vegetables to the most recent one of Light Volleyball. The oral histories and items on display are essential to our continuing to learn and benefit from our history of long links with people of Chinese heritage as much as we learn and benefit from our continuing migrant communities.

Dr Michael Williams, Adjunct Professor Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture, Western Sydney UniversityReturning Home with Glory: Chinese villagers around the Pacific, 1849 to 1949 by Michael Williams, Hong Kong University Press, 2018. [On the pattern of links to China]

The Poison of Polygamy by Wong Shee Ping (trans: Ely Finch), Sydney University Press, 2019. [A Chinese voice from 100 years ago]

Locating Chinese Women: Historical Mobility between China and Australia, edited by Kate Bagnall and Julia T. Martínez, Hong Kong University Press, 2021. [On women]

The China-Australia Heritage Corridor project, https://www.heritagecorridor.org.au/about [An ongoing study on ongoing links]

One Bright Moon by Andrew Kwong, Harper Collins, 2020. [A personal memoir]

ACIAC Chinese Australian History Seminar Series, https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/aciac/ audio_and_visual/aciac_chinese_australian_history_seminar_series [Online overview of Chinese Australian history]

聚焦于乔治河等单一地点的历史,人们或可从中发掘出许多独特和个人的 东西。让当地人从隔壁家的家史中,稍稍了解历史的复杂性。然而历史只 是背景,只有从更广泛的角度去理解,我们才能理解本次展览中出现的 Henry Bing Lee、Gable Sheung Chun Yip、Sun Tiy Sing等人的生活和行为。

市场花园、咖啡馆和水果店是乔治河当地华人社区的表象,但表象之下有 更多纷繁复杂之事。

还有什么比乔治河华人移民史更简单(或更复杂)的事呢?特别是还有图 片和艺术家的诠释?会有什么问题呢?事实上,只要我们承认历史总是错 的就什么问题也没有。历史诠释和相关展览只能寄希望于尽量展示理解我 们的历史所需的个性和背景、网络和联系、见解和辟谣的复杂性。不管怎 样,让我们尽力而为吧。

看上去“华人”是个简单的入门概念——就是来自中国的人,对吧?但其 实 19世纪 40年代,第一批从 “中国 ”来到澳大利亚殖民地的人来自非华夏民

族的满清帝国,他们大多讲福建话,在当时的厦门港被招聘为契约劳工。 这第一批 “移民”的人数在之后几十年里,被从珠江三角洲周边的几个县 来淘金的成千上万的男性(几乎没有女性)大大超过了,正如成千上万来 淘金的欧洲人一样。这些人通过当时在英国控制下新建的港口香港,更加 自由地旅行,甚至经常还欠着船票钱。这些 “华人 ”说的语言与厦门来的人 (这一支的特点是偶尔斗殴)完全不一样,然而即使在这些 “ 广东 ” 人之 中,也有许许多多的方言甚至语言分支。这有时会导致争议,但更多的是

造成了分别的人际支持网络和生意圈,甚至决定了他们倾向于 “移民 ”到哪 个殖民地,当然也决定他们女儿的婚嫁。

以上这一切(包括一系列反华移民措施的颁布和废除)都发生在 19世纪 70 年代越来越多的 “ 华人 ”开始居住在乔治河地区之前。同时在 Botany湾,也

开始出现一些早期的鱼类腌制业。到了这个时期,来自珠江三角洲渔村的 新一代移民开始大量涌入。随着 19 世纪 80 年代锡矿的利润越来越丰厚、

移民人数大幅增加,反华移民限制也再度出台。华人大多在农村、较少在 城市,建立了成功的商业网络。有些人兴建了庙宇,而有些人则改信基督 教。娱乐项目包括中国戏曲,当然更著名的是赌博。对于在当时的悉尼远 郊地区从事商品果蔬种植的人来说,这关乎于继续保持与英国殖民地的世 代联系。随着父辈退休,就轮到儿子们被送去为中国南方的农村家庭赚取 收入。

正是这种代代相传的联系,让华人移民与居住在故乡渔村(或后来居住在 香港)的亲戚相连,通过方言、地区企业和组织联系在了一起。这成为 了 19世纪至 20世纪下半叶华人 “移民 ”的重要背景。这样的人际网络和人员

流动让我们必须重新思考“移民”这一现象,与某些移民不一样,这不是 简单的单向新移民过程。当然许多来自珠江三角洲的人就是这样的,只不 过有些人退休后回到了村里;另一些人在童年时就去了国外,长大后再返 乡;还有一些人结婚或再婚,在不同的地方和文化中成家育儿。

乔治河地区的华人移民:历史背景

头税让一些人开始在澳大利亚生活时背负了更多的债务; 1901年之后,澳 洲还实行了臭名昭著的假听写测试。用爱沙尼亚语等欧洲语言对人们进行 测试的目的是减少在澳大利亚的非白人人数,并让在澳有色人种的许多亲 属难以维持联系。这甚至也让在澳出生的华裔人群的生活变得困难,因为 他们需要获得免试资格才能旅行,而“白种”澳大利亚人则不需要。这种

种族主义观点经常主宰历史,然而我们需要考虑 “ 代理 ”和 “洗白 ”这两个方

面来抗衡种族主义观点。

白澳政策的歧视是不可否认的,但对白澳歧视的过分关注会让人忽略华人 家庭和商业网络的力量。这种力量让华人在种族歧视的背景下继续养家糊 口、教育子女、维系人际网络。将华裔澳大利亚人描述为永久的受害者, 实际上是白澳政策的遗留问题之一;其另一遗留问题则是对澳大利亚历史 的洗白。本次展览希望能抗衡 “洗白

人为澳大利亚作出了贡献,而这些贡献大多被简化成了商品果蔬种植者和 种族主义受害者的贡献。

事实上,白澳政策的拥趸并没有主导这段历史,中国和更广阔世界的变化 对这段历史产生了更大的影响。战争和日本的侵略使许多华人更倾向于选 择澳大利亚,而不是危险中的香港和中国南部,这包括新来的难民,其中 很多都是华裔。当澳大利亚与中国联盟对抗日本帝国时,新来的难民得到 了更多的同情,白澳政策开始出现裂痕。结果就是新一代的华裔澳大利亚 人能够、也愿意从事比以往任何时候都更广泛的生意和工作。

1949年以后,随着中国的新政府实施了一些政策,对珠江三角洲渔村与海 外华人之间的旧联系树立了障碍,更大的变化发生了。甚至那些希望退休 的人也常常选择留在澳大利亚。澳大利亚华人家庭开始寻找中餐食谱,以 帮助他们适应当地食材,并向更广泛的澳大利亚社区介绍中国菜。许多人 逃到香港,并通过为数不多的可行途径进入澳大利亚——餐馆打工和当学 生。持续的白澳政策虽然不愿正视香港的难民情况,但也承认澳洲华人餐

馆是“华人 ” 就业的合法场所,因此这类餐馆的数量增加了。与此同时资

助学生变得越来越容易,因此上世纪五六十年代,有越来越多的中国年轻 人来到澳大利亚留学。

战后最大的不同是虽然许多经香港来澳的人和学生都来自珠江三角 洲,延续着过去以前家庭和方言上的联系,但同时越来越多来自更 广泛地区的华人开始抵澳。从更广泛的背景来看,一直以来中国 移民大部分去了东南亚和太平洋沿岸地区,只有小部分到了澳大利 亚。然而随着欧洲殖民时期结束,在获得独立的国家里,华人经常 受到歧视。因此,主要来自新加坡和马来西亚的华人开始移民澳大 利亚,通常是作为学生,越来越多的是作为大学生。这些新一代的 移民往往是通过科伦坡计划抵澳的。在白澳政策越来越受到颠覆之

后,政府急于避免反弹,于是积极推行了这一计划。然而,事实是 通过科伦坡计划来到澳大利亚的学生与自费学生的比例为 1 比 3 。

其中很多人都留在澳大利亚希望取得公民身份,但直到 1957年以后,华人

和其他非白人才有可能获得公民身份。

移民人数一直很少,直到 1972 年惠特兰政府最终废除了白澳政策,以及 1976年弗雷泽政府接受了越南统一后的第一批“船民”,这一点才有所改 观。同样,许多来自东南亚国家的人(这次是越南和柬埔寨)都是华裔。 直到这个时期,移民澳大利亚的华人的性别失衡才最终得以改善。在白澳 政策的最后几年,许多以前的学生已经能够在香港或其他地方结婚,并把 配偶带来。

20世纪 80年代,两项重大变化再次改变了华人移民到澳大利亚的历史。一

项是澳大利亚国内的,澳大利亚政府把教育部门变成了收费买服务的企 业,至少对海外学生来说是这样。另一项发生在中国,邓小平的改革提供 了良好环境,让中国的中产阶级快速增长,产生了新一代有意愿并有能力 支付澳大利亚大学入学费用的学生。 1989

被屠杀,这一切发生了戏剧性的转变,霍克政府的反应使大约 4 万名受过

”这一问题,让大家了解到一代代的华

年,随着北京天安门广场的学生

良好教育的年轻华人留澳定居。值得注意的除了这批人的年龄、性别和人 数,还有一点是他们绝大多数都讲普通话,并且来自中国除珠江三角洲以 外的许多地区。

在 21世纪初,来自中国的移民人数再次超过了其他地区。越来越多的华人 移民是中产阶级的、受过良好教育的,其中许多以前是留学生。他们的人 数使澳大利亚的“华人”社区达到了自 1901年引入听写测试以来的最高比 例。长期以来,华人社区存在于乔治河地区。从蔬菜到最新的气排球运 动,华人移民的许多贡献丰富了这个社区。这些口述历史和展品对我们继 续学习和受益于我们与华人的长期历史联系至关重要,我们也将从持续接 纳移民的社区中学习和受益。 麦克

《荣归故里:太平洋地区的中国侨乡1849-1949》,麦克·威廉姆斯著,香

港大学出版社,2018年。[论与中国的联系模式]

《多妻毒》,黄树屏著(林雍坣译),悉尼大学出版社,2019年。 [一百年前的中国见解]

《华人女性的定位:在中国与澳大利亚间的历史驿动》,白碧(Kate Bagnall)与Julia T. Martínez编写,香港大学出版社,2021年。[论女性]

中澳承传长廊项目,https://www.heritagecorridor.org.au/about [关于持续联系的持续研究]

《One Bright Moon》,Andrew Kwong著,哈珀柯林斯出版社,2020年。 [个人回忆录]

ACIAC澳洲华人历史系列讲座,https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/aciac/audio_and_visual/aciac_chinese_australian_history_seminar_series [澳洲华人历史在线概览]

·威廉姆斯博士 副教授 澳中艺术与文化研究院 西悉尼大学

延展阅读

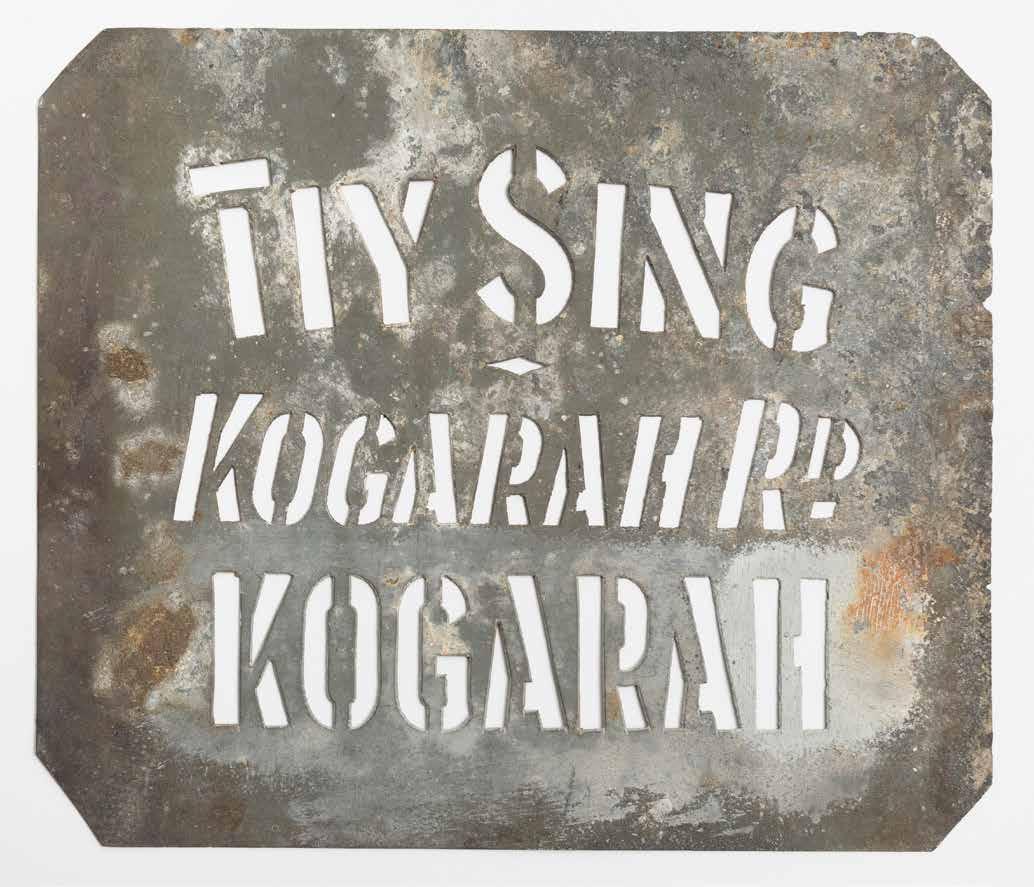

Market gardens were established in Kogarah by English and German families during the 1850s. They often converted cleared bushland into prime real estate. The earliest listing for a Chinese market garden in Kogarah appeared in 1888, with Ah See & Co. on Rocky Point Road. Many Chinese migrants who came to Australia during the gold rushes of the 1850s later found agricultural work. By 1903 the Sydney Mail noted that ‘practically the whole of the vegetables consumed in the metropolis and its many suburbs are the product of Chinese market gardening’. From 1897 Sun Tiy Sing leased a six acre market garden on Kogarah Road (now Princes Highway) where he worked with several other Chinese men. His market garden business in Kogarah prospered and he sold much of his produce at markets in Sydney. By 1921 he had leased another 13-acre property in Beverley Park which he called ‘Sun Tiy Sang’ (New Mountain Life), an auspicious name for a farm. The success of this market garden allowed a truck to be purchased which was used to deliver the vegetables grown to markets. In 1935 Tiy Sing’s 13-acre property was advertised for sale. It was purchased by Kogarah Council in 1938 and became part of the Beverley Park Golf Course which opened in 1941. Tiy Sing’s fate is unknown, but it is likely he returned to China a wealthy elderly man.

19 世纪 50 年代,英裔和德裔家庭在高嘉华( Kogarah )修建了商品蔬果 园。通常是把荒地变成黄金地产。高嘉华最早有记录的华人商品蔬果园出 现在1888年,是位于Rocky Point路的Ah See & Co.。许多在19世纪50年代 淘金热时期来到澳大利亚的华人移民后来都从事了农业工作。根据《悉 尼邮报》的记载,到了 1903 年 “ 城市及其许多郊区消费的几乎所有蔬菜都

来自华人商品蔬果园”。从1897年起,Sun Tiy Sing在高嘉华路上(现在的 Princes Highway)租了一个6英亩的商品蔬果园,在那里他和其他几个华人 一起工作。他大约于 1872年生于广州(广东),于 1884年抵达悉尼。他在

高嘉华的商品蔬果园生意兴隆,大部分农产品都在悉尼的市场上出售。到 了1921年,他在贝弗利公园(Beverley Park)又租了一处13英亩的地产,

命名为“Sun Tiy Sang”,意为新山人生,是一个很吉利的农场名称。商品 蔬果园的成功让他有钱购买一辆卡车,将种出来的蔬菜运到市场。 1935 年,Tiy Sing的13英亩土地打广告进行出售,并于1938年被高嘉华市议会

收购,之后成为了 1941年开放的贝弗利公园高尔夫球场的一部分。我们并 不知晓Tiy Sing的命运,但很可能他回到中国时已经是个富有的老人了。

Stencil plate for produce boxes (c. 1910)

metal

Georges River Libraries Local Studies collection

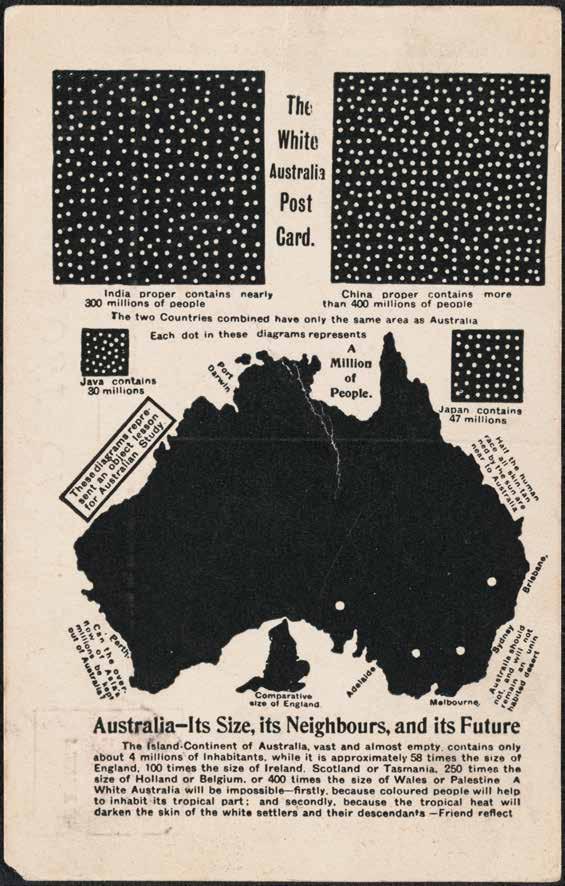

During the 19th century many state government laws restricted Chinese entry into Australia. After the gold rushes of the 1850s growing racial intolerance resulted in the New South Wales government passing the Chinese Immigration Regulation & Restriction Act 1861. The Act required a poll tax of £10 to be paid by or for every Chinese person arriving in the colony of New South Wales. This Act was repealed in 1867 but resulted in further acts being introduced aimed at restricting Chinese migration to Australia. One of the first of these by the new Commonwealth was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 which became known as the ‘White Australia’ policy. It aimed to prevent non-Europeans, particularly those from Asia, migrating to Australia. The Act was harsh, discriminatory, and racist. It restricted Chinese migrants by regulating how long they could stay, if they could bring family members, whether they could work and in what jobs they could work. Chinese migrants were also subject to a dictation test, intended to assess English skills, but could be delivered in 50 words of any European language. Popular promotion that advocated for a ‘White Australia’ was evident in material culture, such as post cards, songs and badges. Some members of the Chinese community opposed restrictions placed on them and China appointed its first Consul-General to Australia in 1909 to support the local Chinese community. By the 1960s public attitudes were changing and the ‘White Australia’ policy was finally dismantled in 1973.

19世纪时,许多州政府的法律都限制华人进入澳大利亚。 19世纪 50年代淘 金热之后,日益严重的种族歧视导致新南威尔士州政府通过了《华人移 民条例和限制法案》( 1861年)。该法案要求每一个到达新南威尔士州殖 民地的华人缴纳 10英镑的人头税。该法案于 1867年被废除,但结果是又出 台了更多旨在限制华人移民澳大利亚的其他法案。其中最先出台的一项, 是新澳大利亚联邦的《移民限制法案》( 1901 年),也就是众所周知的 “白澳大利亚 ” 政策。其目的是防止非欧洲人,特别是亚洲人,移民到澳 大利亚。该法案是严厉的、歧视性的和种族主义的。它对华人移民进行了 限制,规定了他们能居留多久、能否带家人来、能否工作、能做什么工 作。华人移民还必须接受听写测试,旨在评估英语语言能力,但测试可用 50个任何欧洲语言的单词进行。提倡“白澳”的大众宣传在物质文化中很 常见,例如明信片、歌曲和徽章。华人社区的一些成员反对了对其施加的 限制,中国于 1909年任命了其首任驻澳大利亚总领事,以支持当地的华人 社区。到了 20世纪 60年代,公众的态度发生了变化,“白澳”政策最终于 1973年得到废除。

Published by E.W. Cole, Melbourne National Library of Australia, PIC 15675/118

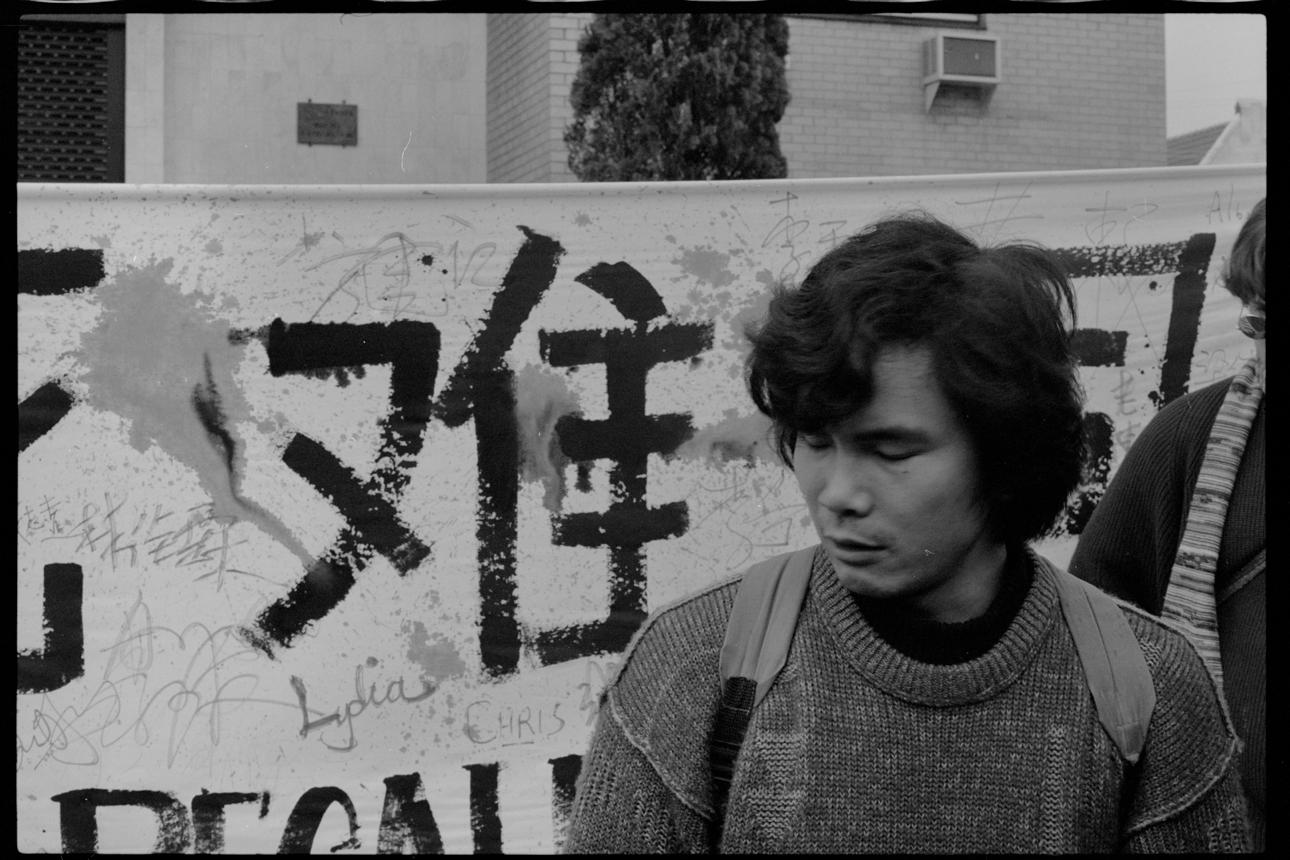

The Tiananmen Square incident began with protests and demonstrations in spring 1989. A small number of students demonstrated in April 1989, but the numbers swelled to over 1 million in the months leading up to this incident. There was growing sentiment for political and economic reform in China during this time. On the night of June 3 into the early hours of June 4, tanks and heavily armed troops advanced towards Tiananmen Square in Beijing, opening fire on or crushing those who tried to block their way. The government crackdown resulted in 241 people (including soldiers and workers) killed and some 7,000 wounded, although some sources suggest higher numbers were injured. In response to this, Prime Minister Bob Hawke committed to four-year entry permits for thousands of Chinese students in Australia. This resulted in the permanent settlement of 42,000 Chinese people in Australia. The journalist Carlotta McIntosh captured scenes outside the Chinese Embassy in Sydney in response to the events in Tiananmen Square. During the 1990s, Hurstville experienced a boom in Chinese migration, with the first wave of people arriving after Tiananmen Square from mainland China. After the British handover of Hong Kong in 1997 further Chinese migrants settled in this area. Many looked overseas to begin new lives, educate their children and invest funds. People were attracted to Hurstville due to its proximity to the city, good transport links and affordability. The large increase in Chinese migration to the area, which today stands at 27% of the population, shaped the urban landscape, revitalized businesses, stimulated the economy, and added to the cultural diversity of the St George region.

Protest against Tiananmen Square massacre outside Chinese embassy and McDonalds workers, Sydney, New South Wales (June 1989)

Photograph by Carlotta McIntosh

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ON160/Item 1081

1989

Carlotta McIntosh拍摄 米切尔图书馆,新南威尔士州图书馆,ON160/Item 1081

天安门事件始于 1989

1989 年 4 月,少量学生进 行了示威,但在该事件发生前的几个月里,人数快速增长到了 100 万以 上。这一时期,中国的政治和经济改革呼声日益高涨。 6月 3日晚,坦克和 全副武装的军队向北京天安门广场推进,向试图挡道的人开火或进行碾 压。政府的镇压导致 241 人(包括士兵和工人)死亡,约 7000 人受伤,有 消息称受伤人数更多。作为回应,鲍勃·霍克总理承诺为成千上万的在澳 中国学生提供四年的入境许可。结果就是4.2万华人在澳大利亚永久定居。

记者Carlotta McIntosh在悉尼中国大使馆外拍摄了这一场景——对天安门 广场事件的反响。在 20世纪 90年代,好市维( Hurstville)迎来了华人移民 潮,第一批是天安门广场事件后,从中国大陆来的移民。 1997年英国移交

出香港后,更多的华人移民在这一地区定居。许多人期望在海外开始新生 活、教育子女、进行投资。好市维吸引人的原因是它离市中心近、交通便 利、实惠宜居。华人移民的大量增加(如今占该地区人口的 27%)塑造了 城市景观、振兴了商业、刺激了经济、增加了圣乔治地区的文化多样性。

天安门广场

年春天的抗议和示威活动。

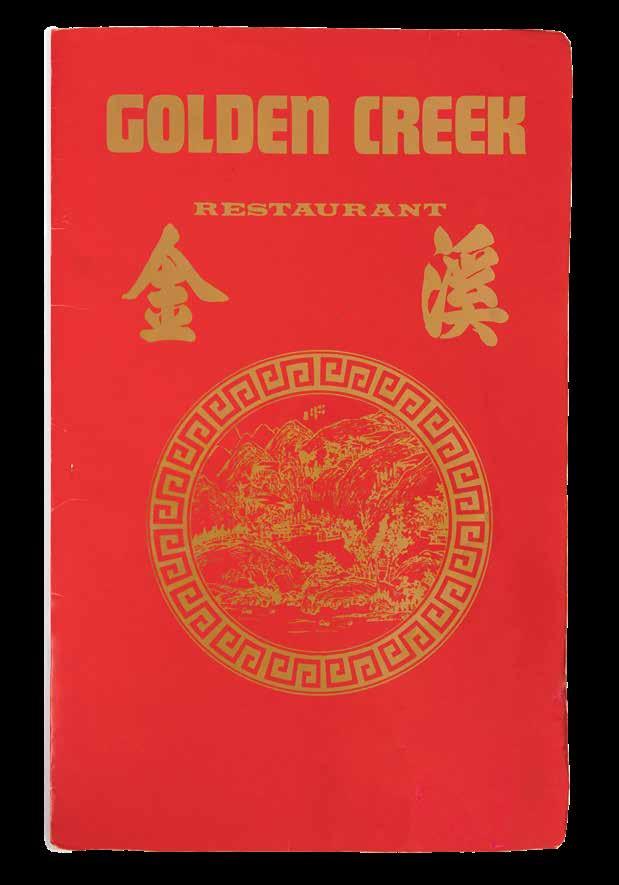

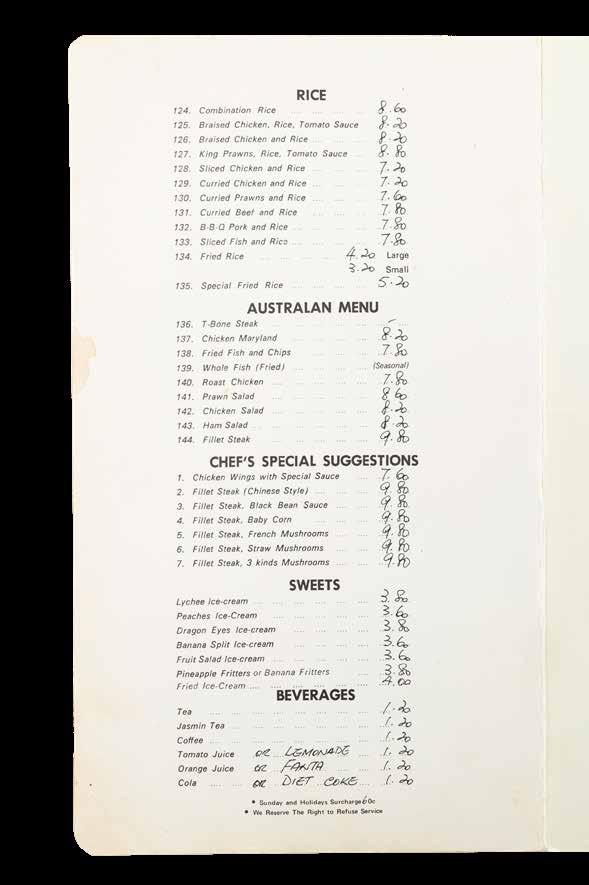

Chinese food came to Australia with indentured labourers who arrived in the 1840s. Cookbooks for Chinese and Australian audiences however were not produced until much later with Mrs. L. Sie’s 50 Recipes for Famous Chinese Dishes being the first, published by the Australia-China Association, Melbourne in 1947. This was followed in 1948 by Cooking the Chinese Way by Roy Geechoun, which adapted recipes using locally available ingredients. Understanding Chinese recipes, preparing Chinese food and using chopsticks were new to many Australians. Although Chinese cafes had been established in Sydney as early as the 1910s, they were often stereotyped as undesirable places; ‘cheap, boisterous, always-open dens’. Despite this, interest in Chinese cuisine increased during the 1930s. Changes to the Immigration Act in 1934 further drove this as established businesses could bring non-relative workers from China to Australia. Cooks and café workers were admitted for limited periods, but they were subject to government scrutiny and the businesses had to meet set financial turnovers. Many migrants who left China after 1949 were employed as cooks and waiters in Australian cafes. Restaurants offered European and ‘Australian’ Chinese dishes. By the 1960s Chinese cafes were established in suburbs in the St George area. Only after this decade did Australians embrace the idea of going to Chinese restaurants to eat out. Golden Creek Chinese restaurant in Riverwood opened in February 1974. It was named after Jinxi (Golden Creek) village in Zhongshan, Guangdong, China and operated until 2008. The first menu from the restaurant was in use until the 1990s.

L. Sie太太所著的《50道中餐名菜菜谱》。1948年又出版了《中式烹饪》,

使用当地有的食材进行烹饪。对许多澳大利亚人来说,了解中餐菜谱、烹 调中餐和使用筷子都是一件新鲜事。虽然华人开的咖啡馆早在 20世纪 10年

代就出现在了悉尼,但通常被刻板地视为不好的地方: “ 廉价、喧闹、总 在营业的馆子 ” 。尽管如此,在 20 世纪 30 年代,人们对中餐的兴趣变得浓

厚。 1934年《移民法案》的修改进一步推动了这一趋势,因为开业已久的 店铺可以从中国将非亲属的工人引进澳大利亚。在有限的时间段里,厨师 和咖啡馆员工可以进入澳洲,但会受到政府的审查,店铺也必须达到营业 额方面的要求。许多 1949年后离开中国的移民被澳洲咖啡馆雇佣为厨师和 服务员。餐馆提供欧洲菜和“澳式 ” 中餐。到了 20 世纪 60 年代,圣乔治地 区的郊区出现了华人开的咖啡馆。直到这十年过后,澳大利亚人才开始接 受去中餐馆吃饭的想法。里弗伍德( Riverwood)的金溪中餐馆于1974年 2 月开业。它以中国广东省中山市的金溪村为名,一直营业到了 2008年。该 餐馆的第一份菜单一直沿用到了20世纪90年代。

Susan金溪餐馆菜单,里弗伍德(约20世纪70-90年代)

Susan Lowe收藏

家的味道

中餐在 19世纪 40年代随着契约劳工来到了澳大利亚。然而直到 1947年,澳 中协会才在墨尔本出版了第一本面向华人和澳大利亚读者的烹饪书

Chinese opera in Australia began on the Victorian goldfields during the 1850s. Visiting overseas troupes performed for the Chinese community but were viewed by colonial Australians who witnessed performances with a mixture of curiosity and disdain. Known for its vibrant make-up, dancing, music and singing, Chinese opera revolves around historic stories and supernatural beings. For many centuries it was the main form of entertainment for urban and rural residents in China as well as Chinese migrants overseas. Colour provides the key to opera characters; red is brave and loyal, black is bold, yellow symbolises ambition, blue-faced characters are fierce while white faces are the villans of the show. The first full-length opera to be performed in Australia after the 19th century occurred in 1940. It was presented by members of the Chinese community at Australia Hall in Sydney as a charity performance to raise money for relief funds during the Second World War. Gable Sheung Chun Yip (1925-2001) arrived in Australia in the 1950s as a migrant from Hong Kong. Throughout the 1970s he was involved with the Chinese community in Haymarket and managed a restaurant. He also organised and ran productions of Chinese opera in Sydney and appeared in various roles, including that of an Emperor. The opera performances were usually charity events, offering the Sydney Chinese community not only entertainment but a way to maintain their cultural history and connections. Costumes and props used in the performances were hand-made, brought back by Gable to Australia from trips to Hong Kong.

Golden

1970s-80s)

fabric, metal, plastic, metallic mesh, faux jewels, pearls, tassels Private collection, Sydney.

19世纪 50年代出现在维多利亚的金矿地区。访 问海外的剧团为华人社区演出,但殖民地的澳大利亚人也带着好奇和蔑 视的心情观看了演出。中国戏曲以其充满活力的妆容、舞蹈、音乐和歌唱 而闻名,主题通常是历史故事和神怪传说。几个世纪以来,戏曲一直是中 国城乡居民以及海外华人的主要娱乐形式。色彩是塑造戏曲人物的关键: 红色代表勇敢和忠诚、黑色代表大胆、黄色代表野心、蓝脸的角色通常凶 猛,而白面则是剧中的恶棍。 19世纪后,在澳大利亚上演的第一部完整的 中国戏曲是在 1940年。这是一场由华人社区成员在悉尼澳大利亚大厅举办 的慈善演出,为二战期间的赈灾筹集资金。叶尚春(Gable Sheung Chun Yip )( 1925-2001)于 20世纪 50年代从香港移民澳洲。在 20世纪 70年代,

他活跃在 Haymarket 的华人社区,并经营了一家餐馆。他还在悉尼组织演 出中国戏曲,并扮演过各种角色,包括皇帝的角色。中国戏曲表演通常是 慈善活动,不仅为悉尼华人社区提供娱乐,也是保持其文化历史和联系的 一种方式。表演中使用的服装和道具都是手工制作的,由叶尚春去香港旅 行时带回澳大利亚。

For much of the 19th and early 20th century Chinese migration to Australia was overwhelmingly male. The 1861 census revealed there were 12,968 Chinese men in Australia compared to only two women. Cultural, social, and economic reasons meant that unmarried men, or men married with their families remaining in China, made up most of the early Chinese populations in Australia. Chinese men remained tied to their families and homeland through return visits and sending money earned back to their villages. The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 also made it difficult for Chinese women to come to Australia. The small number of Chinese women who did migrate to Australia came as wives and daughters, managing households and assisting with businesses. In the municipality of Canterbury, which included the parish of St George, four Chinese women were recorded in 1891. Their identities remain unknown. For many Chinese women, a traditional wedding was an elaborate affair. It was not only an event for the bride and groom, but for their families as marriage was seen as a way of maintaining good ties between villages. The combination of four colours on the collar was intended to expel evil spirits, while the clinking bells as a bride walked were believed to prevent misfortune in the marriage. The motifs on the collar were for ‘blessings’, rather than decoration, and the pomegranate symbolises fertility. The desire for a harmonious union was embroidered on the collar: ‘Combine strength with one heart, help one another and love one another’.

Wedding collar (1951)

silk, cotton, glass beads, metal Maker unknown, China

Lent by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. Gift of Katherine Kerr, 2008.

在 19世纪和 20世纪初的大部分时间里,移民到澳大利亚的华人绝大多数是 男性。 1861 年的人口普查显示,澳大利亚有 12968

有 2 名。出于文化、社会和经济原因,未婚男性或家人留在中国的已婚男 性构成了澳大利亚早期华人人口的大部分。华人男性通过回国探亲和把收 入寄回家乡来与其家庭和祖国保持联系。 1901年的《移民限制法案》也使

华人女性难以进入澳大利亚。少数华人女性以妻女的身份移民到了澳大利 亚,操持家务并协助家里的生意。 1891年在包括圣乔治教区在内的坎特伯

雷市,只有四名华人女性的记录。她们的身份仍然未知。对许多华人女性 来说,传统婚礼是一件精细繁复的事。这不仅是新娘和新郎的大事,也是 双方家庭的大事,因为通婚被认为是保持村庄之间良好关系的手段。领饰 上四种颜色的组合有辟邪的作用,而新娘行走时发出的叮当铃声能防止婚 姻不幸。领饰上的图案是为了 “祈福 ”,而不仅仅是装饰,石榴象征着多子 多福。领饰上绣着对美满婚姻的渴望:

Complex interwoven threads of diasporic and Australian history create rich patterns of memory in the work of each Chinese Australian artist in Our Journeys | Our Stories

Their own stories are as diverse as their artworks: Lindy Lee and Jason Phu were born in Australia and raised here by immigrant parents; Malaysian-born Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen arrived as a small child; Guan Wei first visited in January 1989 to take up a residency in Hobart at the Tasmanian School of Art; Guo Jian and Xiao Lu were post-Tiananmen arrivals. Each has made work for this exhibition inspired by connections between museum artifacts, archival photographs, and their own life stories. Their work is also underpinned by responses to the landscape of the Georges River and its long history of habitation by the Biddegal people of the Eora Nation, by the narratives of Chinese immigration to Australia, and by their personal experiences of diaspora.

The history of the Chinese in Australia is a long one, from fishermen trading with Aboriginal people in Arnhem Land before colonisation, to those who came seeking their fortune on the 19th century goldfields, to recent arrivals from Hong Kong and mainland China. Sydney’s first recorded Chinese immigrant was Guangzhou-born Mak Sai Ying, who arrived as a free settler in 1818 and bought land at Parramatta. In an astute – and quintessentially Australian – move, he opened a pub. Over the next century, immigrants from China opened restaurants and small shops, and started successful market gardens, including those around the Rockdale, Kogarah, and Hurstville areas.

Water plays a large part in these immigrant stories and in the exhibition – in the histories of trade, exploration, colonisation, and the arduous journeys across oceans into safe harbours undertaken by so many new arrivals to this country. But there is also the story of a river, winding from its catchment at Appin through suburbia to meet Botany Bay at Taren Point. The Georges River, and the indigenous and settler people living around it, are present in many of these works too.

Guan Wei, for example, has painted a double-sided folding screen, The Georges River, riffing on a traditional form that represents his Chinese (Manchu) ancestry: decorative folding screens made from wooden panels were a feature of wealthy Chinese homes from as early as the Han Dynasty. A successful market gardener named Tiy Sing is the central subject of his work; Guan examined museum documents and archival photographs and chose twelve images that represent aspects of Tiy Sing’s life in Australia. Painted onto a flat background, his stylised technique recalls the ‘floating world’ of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and the precisely delineated figures in Chinese gongbi court painting.ii Chinese-inspired motifs of clouds and curling waves are juxtaposed with the tiny silhouettes of Aboriginal, Chinese, and European figures. A dark ship in full sail enters Botany Bay, symbolising both the coming violence of British settlement and the arduous journeys across dangerous oceans undertaken by Tiy Sing and his fellow Chinese immigrants.

Guan Wei alludes to colonial dispossession with the inclusion of Aboriginal figures at the top of the composition, and racist injustices suffered by immigrants from Asia are represented by the silhouette of a western figure chasing a pig-tailed Chinese labourer. Tiy Sing’s portrait, based on an archival photograph of the vegetable grower from the certificate exempting him from the notoriously racist Dictation Test, is placed beside the official seal of the Commonwealth of Australia Customs authority. It makes the dark shadows of colonial history inescapable: we see them in the copperplate handwriting of Tiy Sing’s 1906 ‘Exemption from Dictation Test’ certificate, in portraits of the be-whiskered colonial Premier and Governor General and, most disturbingly, in a detail from sheet music published in 1910 – a red ribbon with the chilling inscription, ‘Australia the White Man’s Land’.

‘The river is within us, the sea is all about us.’

(T.S. Eliot, ‘The Dry Salvages’ – No 3 of ‘Four Quartets’)

Fascinated by Australian history and geography, Guan Wei incorporates mountains, rivers, coastlines, oceans, and other cartographic symbols into his work, exploring ideas about empire, trade, and colonisation. Combining real and imagined histories with recent discourses around immigration and the contested ideological territory of border protection, Guan’s visual references range from map coordinates to meteorological patterns, from Chinese astrology and traditional medicine to Daoist cosmology, and from geopolitics to science. His constant subject, however, is universal: the traveller, journeying far from home. It recalls imagery of lonely scholars wandering through mist-wreathed mountain landscapes found in Chinese literati painting, but also references the plight of the contemporary refugee. Guan Wei’s imagery reflects his own life experience, too, of traversing parallel worlds as he moves back and forth between his home in south-western Sydney and his home and studio in Beijing.

A different Australian/Chinese history has found its way into Jason Phu’s quirky homage to the home cooking of his youth – the story of how Chinese cuisine was reinterpreted for western tastes. Chinese food is inextricably part of Australian history – the Chinese on the goldfields in the 1850s ran cookhouses catering for both Chinese and European miners, and every country town in Australia has its Chinese restaurant serving a hybrid, not-quite-Chinese menu of spring rolls, prawn cutlets, sweet and sour pork, and chicken chow mein. Phu’s work is a video, zine, and cookbook entitled, with typical whimsy, There is only today to eat a meal we cooked today, tomorrow we can cook something different, and the day after who knows where we will all be. It was inspired by a recipe book, ‘Cooking the Chinese Way’, first published in Australia in 1948.

Food is such a powerfully emotive element of the migrant story; it can immediately return us to our earliest childhood memories. For Phu, it is bound up with his memories of feeling somehow inauthentic as a ‘Third Culture’ child born in Australia to Chinese parents and hearing their stories of home. He says, ‘I think the past is somehow important. Not only how you lived it, but how you remember it.’iii During the Covid-19 lockdown of 2020 Phu stayed with his parents in Sydney and watched his mother in the kitchen as she re-learned the northern Chinese dishes she remembered from her own childhood. It made him think of his beloved grandmother, his lao lao, in Beijing. Having been thinking about the significance of food to cultural memory, Phu was interested to find ‘Cooking the Chinese Way’ in the list of objects for Our Journeys | Our Stories. When he returned to Melbourne, he came across a later edition of the cookbook owned by a friend, which

he is lending to the exhibition to accompany his video work. In his video Phu prepares recipes from the 1948 cookbook for his housemates in Melbourne to show ‘that food and culture and the idea of “authenticity” can exist anywhere’.iv

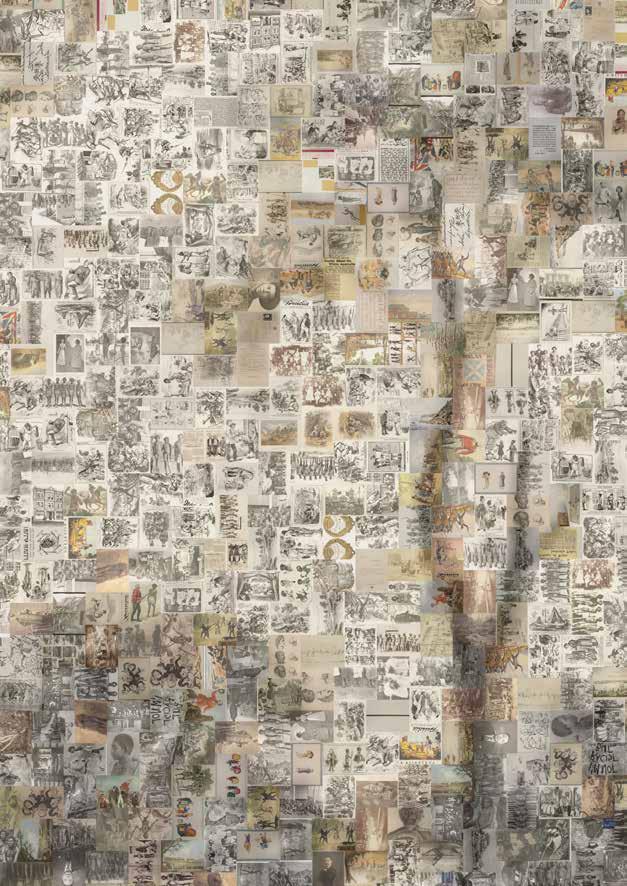

Like Guan Wei and Jason Phu, Lindy Lee explores themes of diaspora, dislocation and belonging. Her parents arrived separately in Australia after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. With two small children (Lee’s siblings) in tow, carrying a suitcase with a false bottom hiding the family’s gold, Lee’s mother made the dangerous journey from China to join her husband in Queensland. Growing up in the suburbs of Brisbane, Lee felt not quite Australian and not quite Chinese. Her earliest exhibited works were altered photocopies of appropriated European Old Master paintings that examined her own sense of being a ‘bad copy’, a faded reproduction.v Later, Lee turned to manipulating images that connected her with her Chinese ancestry, including family photographs; she has returned to this technique with her work, The Market Gardener and the Restaurateur.

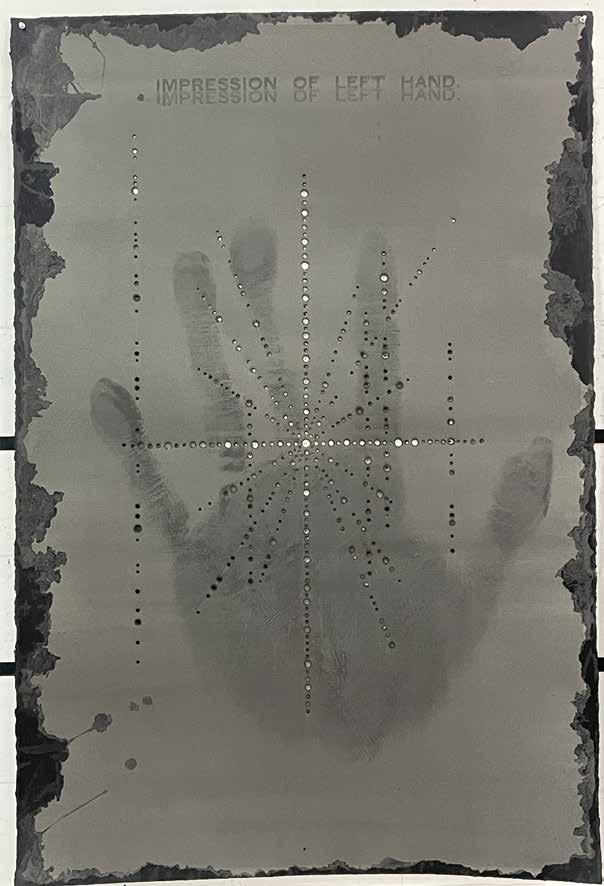

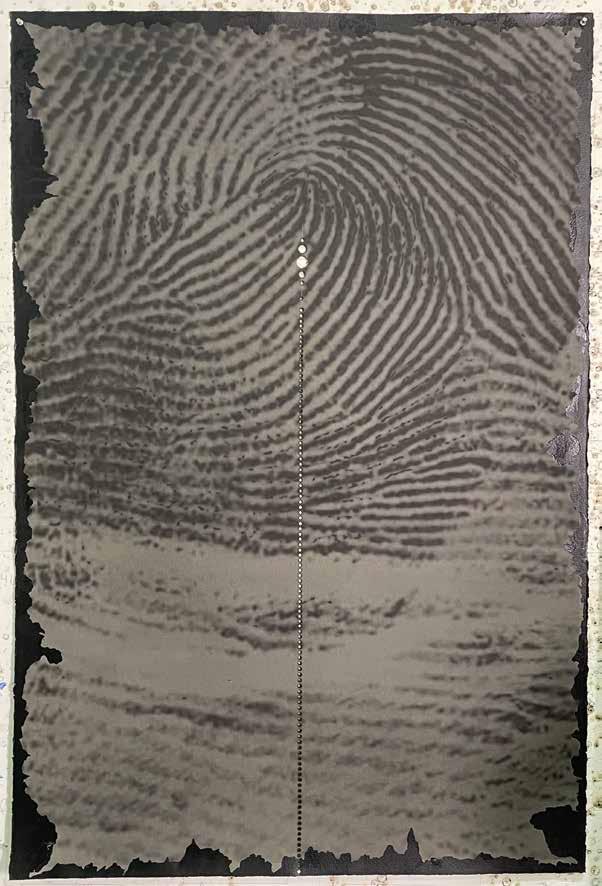

Lee, like Guan Wei, based her work on Tiy Sing’s official papers. But her moody, shadowy, much enlarged reproduction of Tiy Sing’s document is paired with a similar image of another man’s Dictation Test Exemption Certificate – her grandfather’s. Lee Foy, who owned a Chinese restaurant in Lidcombe, was a contemporary of Tiy Sing’s–he could have bought his vegetables from Tiy Sing’s market garden. The official documents bearing their photographs are paired with a handprint and thumbprint in place of signatures, providing us, more than a century later, with a palpable sense of their physical presence. The grave faces of Tiy Sing and his contemporary, Lee Foy, emerge from the mists of the past and meet our gaze, forcing us to face the fact, as Lindy Lee says, that ‘the tentacles of racism reach into our present era’.

The ragged, torn edges of their immigration documents, so redolent of the passage of time, are echoed in the patterns of perforations that are a characteristic idiom of Lee’s works on paper, and her sculptures in metal. These holes, sometimes made by burning the paper with a soldering iron, sometimes by piercing the surface, create tiny pinpricks of light that reference Daoist and Buddhist cosmologies of tian xia – everything under heaven existing in a harmonious relationship. They suggest maps of heavenly constellations, or diagrams of divination. Lee’s artistic practice celebrates her Chinese ancestry, and the contribution made by Chinese immigrants to Australia, but is frequently imbued with a sense of melancholy, loss, and longing.

Those ‘tentacles’ from the past are present in Guo Jian’s work, in the form of secret images hidden within a beautiful landscape. Guo’s work frequently relies on a kind of double coding – what you see at first sight shifts and alters; deeper meanings are revealed, slowly. Trained as a painter in China, Guo Jian is known for his savage social critique in the ‘Political Pop’ idiom. By about 2005, however, he had begun to explore digital photographic collage techniques, creating a series of works exploring the destruction of the natural environment. From a distance they appear to be peaceful landscapes or appropriated classical shan shui (mountain and water) ink paintings, but as you come closer, you realise each work is made up of a mosaic of thousands of tiny photographic fragments. On Guo’s return to his home province of Guizhou he had found scenic vistas and construction sites polluted with rubbish, once-beautiful ancient villages destroyed by overdevelopment. He inserted his photographs of the discards of consumer society into the landscape in a digital mosaic, documenting an ugly human secret hidden in the beauty of the natural world.

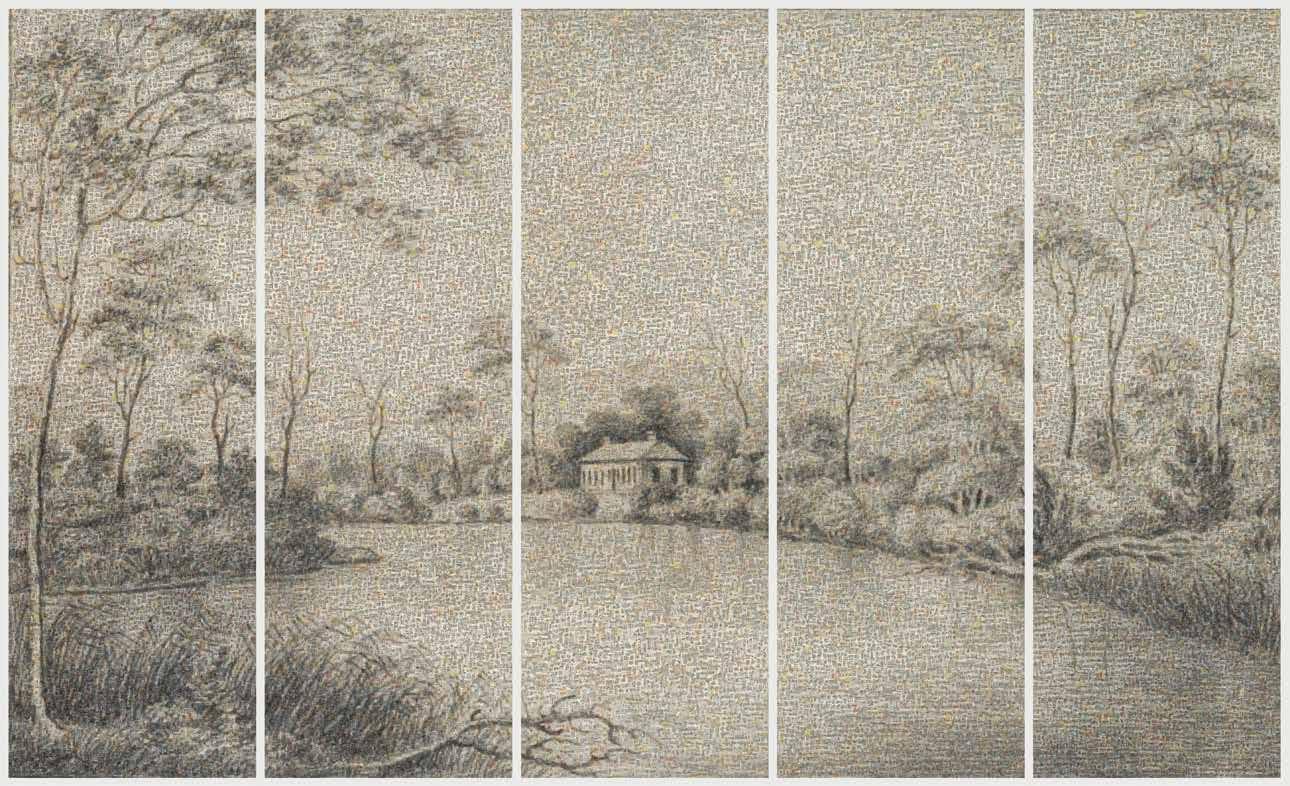

Guo Jian’s multi-panelled work, Where the River Flows, is based on an appropriated colonial sketch. The original work, View of Georges River near Liverpool New South Wales, the property of G Johnston Esqre 1819, depicts a peaceful stretch of river framed by slender gum trees, with a solid Georgian house on the far bank. Major George Johnston came to Australia with the First Fleet in 1788 and was granted large tracts of land around the Sydney area, including more than 200 acres around the Georges River, where a contemporary noted in his journal that he ‘had a good house and an extensive farm’.vi Both banks of the river had been occupied by Aboriginal people for more than 60,000 years. It had provided water, food and a meeting place that connected them to their ancestor spirits. Guo Jian hides an alternative to the colonisers’ version of history inside this work in the form of tiny, pixel-like photographs. He asks us to acknowledge uncomfortable truths – of Aboriginal massacres, colonial occupation, and of the racism directed towards the Chinese. The apparently peaceful landscape contains a dark message of blood and suffering.

Xiao Lu’s video documentation of her 2019 performance, Skew, similarly represents a truth that she feels compelled to speak. Xiao Lu is known for transgressive performance works. In February 1989, as a young artist newly graduated from the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, she brought Beijing’s artworld to a standstill when she fired two shots from a handgun into her installation at the opening of a major exhibition.vii More recent

works involve the use of almost alchemical symbolic ingredients: ink, water, ice, alcohol and smoke are dramatic elements in actions that resemble rituals of purification. Xiao Lu’s work is always provocative, and sometimes dangerous – she pushes her bodily endurance to the limit in many of her works, risking serious injury. After 1989 and the tragic events of Tiananmen, Xiao spent nine years in Australia before returning to China, where she lived and worked until early 2021. Her work in this exhibition reflects her experiences of diaspora, of dislocation, of not quite belonging, of observing and recording.

In Skew, which took place in September 2019 in Hong Kong and is dedicated to that city, we see Xiao desperately fighting to escape a sealed pyramidal container that has been filled with red, blood-like liquid once the artist is inside it. She frantically pushes and claws her way out, finally bursting forth as a panel breaks and fluid gushes out onto the street. Skew is a ritual of mourning. The video is paired with Remember, a series of photographs of the June 4 vigil in Hong Kong commemorating the events of 1989, and of crowds protesting against the proposed extradition bill. Xiao Lu’s work is an elegy for Hong Kong, with its dark colonial history as a Treaty Port, its return to China from British rule in 1997, and its complex, troubled identity today. Like earlier performances in which the materiality of substances such as ink and water symbolise yin-yang reciprocity, Xiao Lu’s representation of trauma in Skew represents a catharsis – and a refusal to be silent.

A strong sense of place is evident in each work in the exhibition. Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen undertook the challenge of responding to artefacts held in the museum with a quiet and considered approach befitting an artist whose work centres around a process she calls ‘embodied listening’. In her experimental drawings, often combined with sound recordings, she explores the complexities of how we are connected to land. Born in Malaysia to Chinese parents with Hakka ancestry, Chen reflects on histories of migration from southern China. She was initially inspired by listening to the oral histories of migrants who, like Chen, are now living on (unceded) Aboriginal land and responding to the beauty of the natural world in their new home. Working en-plein-air in Oatley Park, she listened to the sounds of birds, wind, water, and the voices of passers-by speaking many languages.

In response to the apparently random direction of the wind blowing her paper, she drew delicate, rhythmical ink lines, each representing a possible life path, a potential direction.

Chen’s work obliquely references the history of literati shan shui landscape painting, but the presence of the landscape is not just visual – it becomes a sensory memory in the form of recorded sounds – lapping water, wind, and the hum and buzz of insects. Working with ink in the traditional manner, grinding an ink stone and using fine brushes to make slow, considered marks on xuan paper, her practice is like a form of meditation.

The museum artefact that Chen selected as a source of ideas and inspiration was the qiuqian (‘chi chi’ or fortune telling sticks) often used for divination in Daoist temples. They are depicted in Guan Wei’s work too, on the rear panel of his screen. Qiuqian represent the very human desire to find certainty amidst the chaos and confusion of life; similar sets were likely brought to Australia by the first Chinese arrivals in the 19th century. Here, they are a potent symbol of the turbulence of historical forces that shape our lives and our journeys. The wind and water that influenced Chen’s production of the work in situ are metaphors. Her work is an allegory of chance – how it operates in human destiny, and how people’s fates are at the mercy of the winds of global geopolitics.

In each artist’s work, and in their stories, we hear echoes of soft voices from the past –from those who lived along the river for aeons, and from those who crossed the ocean –for trade, for imperial power, for adventure, to escape famine or persecution, or to make a better life in a safe harbour. Themes of migration, dispossession, dislocation, loss, and memory are woven together, creating a complex narrative that honours all those who have left their traces on this landscape.

Luise Guest Independent writer & researcherNote: The author interviewed Guan Wei and Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen in their Sydney studios, and has previously interviewed Guo Jian and Xiao Lu; they each provided her with additional information about their works in this exhibition. Lindy Lee and Jason Phu responded to the author’s questions via email.

i See https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/harvest-of-endurance/scroll/early-chinesemigrants#:~:text=Records%20show%20that%20about%2018,and%20purchased%20 land%20at%20Parramatta. [accessed 2.5.21]

ii Gongbi painting is a meticulous and detailed painting style, often associated with court painting. The V&A Museum in London produced an excellent video that shows an artist working on silk to create carefully delineated figures replicating a famous painting. https:// www.vam.ac.uk/articles/chinese-gongbi-silk-painting [accessed 20.5.21]

iii Jason Phu, Artist Profile, Issue 47, 2019, available at https://www.artistprofile.com.au/jasonphu/ [accessed 2.5.21]

iv Jason Phu, in an email to the author, 16 April 2021

v The author’s review of Lindy Lee’s exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, ‘The Moon in a Dewdrop’, was published by Randian on 18 February 2021. See https://www. randian-online.com/np_review/lindy-lee-moon-in-a-dewdrop-replicas-postmodernism-andbad-copies/ [accessed 2.5.21]

vi For maps and other historical documents linked to Guo Jian’s choice of the 19th century drawing see https://dictionaryofsydney.org/natural_feature/georges_river and for details of George Johnston see https://www.peterwalker.com.au/johnson.html [accessed 2.5.21]

vii For more information on Xiao Lu’s 1989 work Dialogue see the author’s book Half the Sky: Conversations with Women Artists in China (Piper Press, Sydney: 2016) or Xiao Lu’s interview with Monica Merlin for Tate, available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/researchcentres/tate-research-centre-asia/women-artists-contemporary-china/xiao-lu [accessed 19.5.21]

《我们的旅程·我们的故事》中作品所呈现的,是海外华人与澳洲历史繁

复交织,一同生长而独特的丰富记忆,展现的是这些艺术家丰富多元、有 深度的人生故事。李林迪和符子龙出生在澳大利亚,由移民来澳的父母抚 养长大;曾苑慈出生在马来西亚,来澳大利亚的时候还是个孩子;关伟于

1989 年 1 月首次抵澳,并在霍巴特塔州艺术学院担任驻留艺术家;郭健和 肖鲁在天安门事件之后来到澳大利亚。每位艺术家创作的灵感均来源于博 物馆的物件、历史相片以及他们人生经历之间息息相关的联系。透过讲述 华人移民到澳大利亚的故事以及作为海外华人的个人经历,他们创作的核 心主体中都有对乔治河自然风光情感抒发以及对在 Eora原住民土地居住的 Biddegal民族悠久历史的感慨。

从早在欧洲殖民时期以前就有华人渔民与Arehem岛原住民通商,到十九世 纪有许多华人来这里淘金,以及如今从香港和中国大陆来的华人移民,华 人在澳大利亚留下了长久的历史足迹。悉尼最早有记录的华人移民是来自 广州的Mak Sai Ying ,他出生于广州,1818年作为自由移民抵达澳洲,并

在Parramatta买下土地。之后做了个十分精明且非常“澳洲”的决定,他开 了一间酒馆。i 在接下来的一个世纪里,不断有华人移民来开餐馆、开商 店,并建立起繁荣的蔬菜种植业,并在Rockdale、Kogarah、Hurstville等地 扎堆,欣欣向荣。

在这些移民故事和展览中,无论是贸易、探索未知领地、殖民,还是无 数历尽艰辛,漂洋过海最终驶入避风港湾的新移民,您会发觉自始至终 “水”都扮演着重要的角色。然而除此以外,从 Appin 集水区蜿蜒穿过郊

区,在Taren Point与Botany Bay港湾相遇的乔治河也书写着无数传奇,在这

条河的两边,无论是原住民,还是新移民都在这里生活安居乐业,这些也 出现在展出的许多作品中。

例如,艺术家关伟的双折屏风画作《乔治河》,就是他在华人传统艺术形 式屏风上的即兴绘画艺术表达。装饰性极强的木质传统折叠屏风是华人富 贵家族常有的物件,最早可以追溯至汉代。该作品的核心主题是一位还算 富裕,名叫Tiy Sing的蔬菜农。为了创作该作品,关伟通过博物馆查阅史 料,收集历史照片,并选出12张图片来代表Tiy Sing在澳大利亚生活的方 方面面。画作背景以平面形式展现,他艺术表达的某些细节让人联想到日 本“浮世绘”以及中国皇室国画中的工笔画风 ii 。充满中国国画特色的云 彩和卷着浪花的潮水与原住民、华人、欧洲人的轮廓形成视觉对比。一支 驶入Botany Bay港湾的黑帆船既象征着即将来临的英国残酷殖民暴力,又 象征着Tiy Sing及他的华人移民远渡重洋的艰辛旅途。

关伟作品中的上方的原住民形象是对殖民剥夺主义的影射,作品中西人追 赶长辫子华人劳工的轮廓画象征着亚洲移民所遭受的种族主义不公。作品 中澳大利亚联邦海关印章旁就是菜农Tiy Sing的肖像照,照片取自他的听

写测试豁免证书,极具种族主义色彩。殖民历史的阴暗在这种表现下赤裸 呈现,无处藏身。作品中可见Tiy Sing 1906年“听写测试豁免”证书的铜 版笔迹。在留着胡子的殖民地州长兼联邦总督的肖像中有一个让人难受的 地方——一张 1910 年出版的澳大利亚国歌曲谱的红丝带上写着“澳大利 亚——白人的土地”。

关伟对澳大利亚历史和地理有浓厚的兴趣,他的作品中也融入了许多澳大 利亚的山水河流、海岸风光、大海和其他澳洲的地貌特色,并在这些大背 景下引发人们对帝国、贸易、殖民的思考。关伟将真实的历史和自己的想 象与近年来关于移民和充满争议的边境保护意识形态的论调相结合,作品 的视觉元素丰富,从地图坐标到气象模式,从中国的算命、传统医学到道 教世界观,从地缘政治到科学。然而,他作品永恒的主题总是一样,即远 离家乡的旅者。这不仅让人联想到中国文人画中孤独学者在云雾缭绕的山 野中漫游的意象,也让人想到当代难民流离失所的困境。关伟在澳大利亚 悉尼西南的家宅和位于北京的家和工作室两地工作生活,因此他作品的意 象也是自己在平行世界来回穿越的生活经历的反映。

符子龙万万没想到,自己孩提时代的家常菜竟然成就了另一段特别的澳大 利亚华裔历史。他的作品蕴含独特的幽默,也是对这段宝贵经历的纪念。 这是关于如何将中国菜改良成西式口味的故事。中国菜是澳大利亚历史不 可磨灭的一部分,十九世纪五十年代的金矿食堂都是华人厨子,不仅给自

己的华人同胞做吃的,还给欧洲移民矿工做饭。而且,在澳大利亚的任何 小镇,都能找到一家中餐馆,做的不太像真正中餐的混合型饭餐,虽然也 叫春卷、虾球、糖醋里脊、鸡肉炒面等等。符子龙的作品算是一部视频杂

志菜谱,名称风趣古怪,叫做《今天吃今天的饭菜,明天再做不同的,后 天谁知道我们在哪儿》。作品的灵感来自一本首刊于1948年发行的名为

本食谱的新版本,朋友就借给了他用于本次展览,与他的视频作品搭配出 现。视频中,符子龙按照 1948年食谱中的做法给他在墨尔本的室友做了些 吃的,以此表达“食物、文化以及‘真实性’的概念无处不在”。iv

李林迪的作品跟关伟、符子龙一样,都是对海外侨民、背井离乡、归属感 的探索。她的父母在 1949年中华人民共和国成立后分别来到澳大利亚,带 着两个年幼的孩子(李林迪的哥哥姐姐),母亲背着一个有隔层的手提 箱,里面藏着家里的金子,从中国出发,踏上了危险的旅程,来到昆士兰 州与丈夫团聚。在布里斯班郊区长大的李林迪觉得自己不太澳洲,也不 太中国。她最早期展出的作品借用欧洲大师画作为基础并进行“艺术加

v 之后,李林迪开始转向通过修改家庭照片等图片,探索自己与她中国血统 的联系。在她的作品《蔬菜农与餐馆老板》中,该艺术技巧再次出现。

食物是移民故事中强烈的情感元素,能让我们立即回到自己最早的童年记 忆。在符子龙的记忆中,作为父母为华人出生在澳大利亚的“第三文化” 子女,并且总是只能从父母口中听说家乡的故事,他总有种不纯粹感觉。 他说:“从某个角度上来说,过去很重要,因为它不仅关系到自己的切身 经历,还涉及在脑海中留下形成的方式。”iii 在2020年悉尼因疫情封城期 间,符子龙和他父母住在一起,看着母亲在厨房里重温自己童年时记得的 中国北方菜时,他想起了在北京跟自己很亲的姥姥。在思考了食物对文化 记忆的重要性后,符子龙特别希望把《中式烹饪》这本食谱列入《我们的 旅程 · 我们的故事》展览中。他回墨尔本时,偶然看到一个朋友那里有这

李林迪和关伟一样,作品也以Tiy Sing的官方文件为蓝本。但她的作品中 Tiy Sing的文件以一种阴郁、模糊不清的方式放大呈现,与摆放在一旁另 一位男士(她祖父)的听写测试豁免证书形成对比。Lee Foy在Lidcombe有 一家中国餐馆,跟Tiy Sing是同一代人 祖父可能也在Tiy Sing蔬菜店买 过菜。有他们照片的官方文件签名处可见手印和指印,一个多世纪后,这 种方式可以让我们感觉到他们真实的过去。Tiy Sing和同时代的Lee Foy的 严肃面孔从过去的迷雾中浮现,与我们的目光相遇,迫使我们面对一个逃 不掉的事实,用李林迪自己的话说: “ 种族主义的触角伸向了我们现在的 时代。”

这些移民文件边缘残破,散发着时间流逝的气息,在穿孔图案中得到呼 应,穿孔图案是李林迪纸材作品和她金属雕塑的典型艺术特色。这些洞, 有时是用烙铁烧纸形成,有时是穿透表面,创造出微小的光点,引申至道 教和佛教的世界观 “天下 ”——天下万物以和谐的关系存在,这些图案象征 了天上的星座或占天卦图。李林迪的艺术是对自己中国血统的赞美,是对 华人移民为澳大利亚做出贡献的歌颂,但经常充满了忧郁、失落和渴望的 情感。

工”,以表达她自己的心中的 “ 拙劣复制品 ” 的感觉,即褪色的复制品。

在郭健的作品中,一眼看上去美丽的风景总隐藏了些什么,那些来自过去 的“触角”通常以秘密图像的形式慢慢浮现。郭健的作品常常以“双重编 码”的方式呈现 最初看到的事物会逐渐变化,一丝一点逐渐揭开更深 的含义。郭健在中国学习的美术,以其“政治波普”风格且野蛮的社会批 判性作品而闻名。之后在 2005年左右,他开始探索数字摄影拼贴技术,创 作了一系列关于自然环境被破坏的作品。远看,是宁静的风景或正儿八经 的古典山水墨画,但一旦走近时,您会发现每幅作品都是由成千上万个微 小的摄影碎片组成的马赛克。郭健回到家乡贵州,发现无论是秀丽的风景 还是建筑工地,都充斥着垃圾和污染,曾经美丽的古村落也因过度开发而 被破坏。他将消费社会抛弃的照片安插到数字马赛克风景中,记录下自然 界的美丽中隐藏的人类丑陋的秘密。

郭健的多镶板作品《河水流向何方(Where the River Flows)》借用了一幅 殖民时代的手绘图为基础。原作《新南威尔士利物浦附近的乔治河风景》 是 1819年乔治·约翰斯顿·埃斯克雷的财产,画中央宁静的河流被细支桉

树叶沿画框包围,远处的河岸上有一栋坚固的乔治亚时代风格的房屋。乔

治·约翰斯顿少校于 1788年随第一舰队来到澳大利亚,并受封悉尼地区周 围的大片土地,包括乔治河周围的 200 多英亩土地。一位当代人士在他的

日记中写道,乔治在那里“有一所很不错的房子和一个大农场”。vi 原住民

在这条河的两岸生活了 6 万多年。这里曾经为他们提供水源、食物,还是 他们与祖先灵魂交通的圣地。在这部作品中,郭健以微小的、像素般的照 片形式隐藏着西方殖民主义历史的另一个视角。他要求人们承认令人不安 的事实——屠杀原住民、殖民占领和针对华人的种族主义。表面上平静的 风景画隐藏着血腥、痛苦的黑暗哀嚎。

肖鲁以其冲突强烈的表演作品而闻名。肖鲁 2019 年表演艺术《歪曲

(Skew)》的影像记录,展现的是她为了说出自己的事实而无法压抑的冲

动。 1989 年 2 月,刚从浙江美术学院毕业的年轻艺术家的她在一个大型展 览的开幕式上用手枪向自己的艺术装置开了两枪,让北京的艺术界瞬间静

止。vii 近年的作品涉及使用与炼金术息息相关的象征性原料:墨水、水、 冰、酒精、烟等充满戏剧性的元素,表达出一种净化的仪式感。肖鲁的作

品总是充满挑衅,有时也很危险——她在许多作品中将自己的身体耐力发 挥到了极限,冒着严重受伤的风险。在经历了 1989年和天安门的悲惨事件 后,肖鲁在澳洲度过了九年,然后返回中国,在那里生活和工作到 2021年 初。她在这次展览中的作品反映了她离散、错位、不完全归属、观察和记 录的经历。

《歪曲》于 2019 年 9 月在香港展出,以这座城市为主题,表演开始后,我 们看到艺术家肖鲁被放入一个密封的金字塔形容器,进入后她开始拼命挣 扎着要从中逃脱,容器中充满红色、像血一样的液体。她疯狂地推、抓, 寻找自己的出路,最后,面板破裂,液体四溅喷到街上爆发而出。《歪 曲》是哀悼的仪式。该视频与 6月 4日在香港举行的纪念 1989年事件守夜活 动摄影作品展《记得( Remember )》一同展出,摄影作品还有记录抗议

拟议引渡法案的示威游行。肖鲁的作品是香港的一曲挽歌,它有着作为通 商口岸的黑暗殖民历史, 1997年从英国统治下回归中国,以及今天复杂而 混乱的身份。在她早期的表演作品中,墨水、水等元素的物质性象征着阴 阳对转,肖鲁在《歪曲》中对创伤的表现代表了一种宣泄——以及对沉默 的拒绝。

展览中的每件作品都都有极强的场景感。曾苑慈的作品核心都围绕着一个 她称之为“沉浸式倾听”的过程,她的参展作品以一种安静而仔细雕琢的 方式将博物馆里的艺术品复活,这种方式也适合她的艺术风格。她通过自 己与录音结合的实验性绘画中,探索了人类与陆地之间关系的复杂性。曾 苑慈出生在马来西亚,父母都是客家人,她通过这种方式回顾自己从中国 南方移民过来的历史。她最初的创作灵感来自于听其他移民的口述历史。 这些移民和曾苑慈一样,现在生活在(未开垦的)原住民土地上,在自己 新的家园感受并回应自然世界的美丽。曾苑慈在奥特利公园露天创作,聆 听鸟儿、风、水声,以及说着各种不同语言路人的声音。

随性的风吹过,她手中画纸自由舞蹈,与风、画纸共舞的她手中的画笔勾 勒出精致、有节奏的墨线,每一条都代表一条可能人生,一个可能的方 向。曾苑慈的作品隐隐约约地从文人山水画历史卷轴中浮出,但山水不仅

是视觉上的,还是一种感官记忆,以录音形式记录下来的水拍岸、风声、 昆虫的嗡嗡声。她遵循文房传统,用墨水创作,用砚台磨墨,用细毫在宣 纸悠然而深邃地描绘,这种创作好比冥想。

在博物馆展品中,曾苑慈选择求签盒作为灵感来源,该物品通常在道观中 常用来算命。关伟的屏风作品后面板上也有相关描绘。算命求签代表的是 人们在混乱生活中寻找确定性的渴望。这样的求签盒大约在 19世纪由第一 批来澳华人带入。历史动荡的旋涡主导塑造了每个人的生活和人生旅程, 而求签盒正是对此的强烈回应。曾苑慈 “就地 ”创作时的风与水还有一层隐

喻。她作品的寓意主题是“偶然性” 它在人命运中的作用,以及人的 命运如何因地缘政治而彻底改变。

在每位艺术家的作品和他们的故事中,我们都能听到过去轻柔的呼唤 来自那些在河边生活了数千年的人,来自那些穿洋过海的人——为了贸 易、帝国权力、冒险、逃离饥荒或迫害,或为了更安全的地方过上更好的 生活。移民、剥夺、流离失所、失去和记忆的主题交织在一起,这支悲喜 交加、复杂多彩的故事集,向所有在这片土地上留下足迹的人致敬。

i 文献参阅:https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/harvest-of-endurance/scroll/early-chinesemigrants#:~:text=Records%20show%20that%20about%2018,and%20purchased%20land%20at%20 Parramatta. [访问日期:2.5.21]

ii 工笔画是一种细节感极强的绘画风格,通常与宫廷绘画联系在一起。伦敦的V&A博物馆制 作了一段精彩的视频,展示了一位艺术家根据一幅历史名画在丝绸上通过工笔画法再现的人 物画作 https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/chinese-gongbi-silk-painting [访问日期:20.5.21]

iii 符子龙,艺术家介绍2019年第47期;网址:https://www.artistprofile.com.au/jason-phu/ [访问日 期:]

iv 符子龙于2021年4月16日给作者发送的电子邮件

v 作者对李林迪在澳大利亚当代艺术博物馆的展览《露珠中的月亮(Moon in a Dewdrop) 》”的评论由Randian于2021年2月18日出版。文献参阅: https://www.randian-online.com/np_ review/lindy-lee-moon-in-a-dewdrop-replicas-postmodernism-and-bad-copies/ [访问日期:2.5.21]

vi 有关地图和郭健所选19世纪绘画相关的其他历史文献,请参阅:https://dictionaryofsydney. org/natural_feature/georges_river;有关乔治·约翰斯顿的详情请参阅: https://www. peterwalker.com.au/johnson.html [访问日期:2.5.21]

vii 有关肖鲁1989年作品《对话(Dialogue)》详情,请参阅作者的书籍半边天:与中国女艺 术家的对话》(披珀出版社,悉尼:2016年),或泰特莫尼卡·梅林的肖鲁访谈内容;网 址: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/tate-research-centre-asia/women-artistscontemporary-china/xiao-lu [访问日期:19.5.21]

Luise Guest

注:作者于关伟和曾苑慈各自在悉尼的工作室分别采访两人,之前已采访 过郭健和肖鲁;每位艺术家都向作者就本次展览中的作品提供了额外信 息。李林迪和符子龙通过电子邮件回答了作者的问题。

新南威尔士大学艺术设计学院 独立作家兼研究员

Cindy Yuen-Zhe Chen is an emerging artist living and working in Sydney on unceded Darramuragal and Gadigal lands. She uses experimental drawing, listening and sound practices to explore processes of embodied listening. Through interactions with the surfaces, people, and atmospheric contingencies of places, Chen examines how expanded drawing and listening practices can engender new connections and enact distinct senses of places. As the recipient of the University Postgraduate Award, Chen completed a Doctor of Philosophy in Art, Design and Media at the University of New South Wales Art and Design in 2020. Chen has presented her research internationally in England and China.

With work held in private and public collections, Chen has exhibited in Australia and China in solo, group and finalist prize exhibitions. In 2020, Chen was selected to participate in a curated group exhibition at Ideas Platform in Artspace, Woolloomooloo, and invited to hold a solo exhibition by Willoughby City Council. In December 2018, Chen held a solo exhibition and undertook an artist residency at Ningbo Museum of Art, China, where her work was acquired for their permanent collection. In 2017, she was selected to exhibit in Beijing’s Today Art Museum as a part of Art Nova 100, an exhibition for emerging artists under the age of 30. Chen has undertaken artist residencies at Akiyoshidai International Art Village in Japan and Hill End, Bathurst Regional Gallery. She is represented by Art Atrium in New South Wales and is currently a studio artist at Parramatta Artist Studios.

Divining possible pathways 2021 ink, watercolour and pencil on Wenzhou paper (detail)

“As an artist who is based in Sydney, it is essential for me to examine how my context as a female artist of migrant Chinese heritage inflects the relationships that I develop with people and places within Australia. My family arrived in Sydney from Penang, Malaysia, 30 years ago on 19 February 1991. My Hakka ancestors have a long history of migrating and settling upon the lands of other people, and by moving to Sydney, we have continued this tradition by making our home in Gadigal and Darramuragal Countries.

In listening to the stories of local migrant people who are residing in the Georges River area, I considered how their journeys, like mine, have unfolded upon Aboriginal Countries. They spoke of the incredible warmth and intensity of colour in the land, water and sky, their sensory receptiveness heightened by encounters with a landscape that was utterly distinct from those that they had experienced in China and other countries. Having grown up here, my bodily senses have been shaped by the Australian land. However, in engaging with places through embodied listening, drawing and sounding processes, I continue to be surprised by the rich variations of my home. By engaging with the wind in Oatley Park and allowing it to direct the lines of my drawing, I chose to work within a significant meeting place of the Biddegal people. Listening to the wind, trees, water, animals, and languages from different cultures in Oatley Park and Carss Bush Park, I realise that these places continue to be practiced as a point of convergence for the journeys of many people.”

挖掘可能的路径 2021 温州纸上的墨水、水彩画和铅笔(详版)

新兴艺术家曾苑慈根植于悉尼北部原住民的 Darramuragal 和 Gadigal 原始土 地,通过实验性绘画、声音和音响方式来探索 “沉浸式聆听 ”。通过与物体 表面、人和环境的互动,研究拓展式美术和音响方式可以如何产生新的联 系并再现地理位置的独特感观特性。曾苑慈荣获研究生奖,并于 2020年获

得新南威尔士大学艺术与设计学院艺术、设计与传媒哲学博士学位。她在 英国和中国等国际舞台也展示过自己的研究成果。

曾苑慈的作品有被私人收藏,也有公众机构收藏,曾在澳大利亚和中国举 办个人、团体和决赛奖展览。 2020 年,她的作品入选 Woolloomooloo 艺术 空间创意平台的策划组展,并被 Willoughby 市政府邀请举办个展。 2018 年

12 月, Chen 在中国宁波美术馆举办个展并获得驻留艺术家资格,她的作 品也被列入美术馆永久收藏。 2017 年,她入选北京今日美术馆参加“ Art Nova 100”展(Art Nova 100是专为30岁以下的新兴艺术家举办的展览)。

她还曾在日本秋吉代国际艺术村和Bathurst Hill End地区画廊担任驻留艺术 家。她的的经纪公司为新南威尔士州的Art Atrium艺术代理公司,目前在

Parramatta艺术工作室继续她的艺术创作。

Divining possible pathways 2021 ink, watercolour and pencil on Wenzhou paper (detail)

挖掘可能的路径 2021

温州纸上的墨水、水彩画和铅笔(详版)

在悉尼从事艺术创作,自己作为女性华人移民艺术家的背景对我与澳大利 亚当地的人或地方所产生联系的文化互动是我艺术表达的核心重点。 30年 前, 1991 年 2 月 19 日,我的家人从马来西亚槟榔屿移民来到悉尼。我的客 家祖先有着悠久移民史,古往今来经常在他族人的土地上定居。举家搬到 悉尼也是这一传统的延续,我们在 Gadigal 和 Darramuragal 的原住民土地上 安家。

在听乔治河地区当地移民的故事时,我联想到他们在原住民国度的漫漫旅 途,就好像自己的移民之旅。他们描述了土地、水和天空难以言状的、温 暖绚丽的色彩,这种在中国和其他国家从未经历过的完全不同景观给他们 带来强烈的感官刺激。我在这里出生长大,我的身体感观由澳大利亚的土 地塑造。然而,通过沉浸式聆听、绘画和音响方式来感受不同的地方时, 我依然对故乡丰富多彩的多样性感到惊讶。在奥特利公园风中的作画,让 风导引我的绘画线条,我选择了前往 Biddegal 原住民的圣地创作,聆听奥 特利公园和卡斯丛林公园里不同文化的风、树、水、动物的歌唱和言语, 我领悟到这些地方在时空中继续作为汇聚点,承载着千万旅者的足迹。

Guo Jian was born and grew up in China but has been living and working in Australia since 1992. He tells stories through art that relate to his own experiences and reality. Guo Jian and his art are products of the last 50 years of violence and tumult in China, from the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s, to the Sino-Vietnamese War at the beginning of the 1980s, and through to the horrors of the Tiananmen Square incident. Guo Jian’s art is not about preaching or converting others but rather a reflection of his observations from both sides of propaganda and art. As a result of his firsthand perspective both from within and outside propaganda systems in China, he sees abundant commonalities in the Chinese and Western approaches to ideas of persuasion.

Guo Jian’s work has been exhibited and collected in Germany, France, Belgium, Sweden, USA, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong and China, including Musée de Picardie, France; Brussels Art Festival, Belgium; White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney; the Art Gallery of New South Wales; the Queensland Art Gallery; and the Australian National Gallery. He has been featured in Artist Profile, The New York Times, CNN, the Sydney Morning Herald, ABC Radio and TV, and on the cover of the Asian Wall Street Journal’s weekend magazine. Guo Jian is represented by Defiance Gallery, Sydney and Arc One Gallery, Melbourne.

“Every time I turned on the computer to search for stories about the early settlers in Australia, apart from the innumerable pictures and materials about the hardship, perseverance, bravery, and frontier expansion of the early settlers, I would see a lot of documentary photographs and cartoons of Indigenous Australians being massacred, and racism towards Chinese immigrants. Between these, flashing up alternately on the computer screen, were those classically beautiful, colonial European landscape paintings.

Shocked from seeing and hearing - both on social media and in real life - the conservative, far-right, racist, and even fascist comments in relation to these histories, I had the idea of putting what had happened in history - the suffering, the blood, the discrimination, and arrogance - into a beautiful, classic, colonial style landscape painting, allowing the audience to feel the grief of what seems to be far away in the past. This intricate photo collage references A.W.F. Fuller’s pencil drawing View of George’s River near Liverpool New South Wales (c. 1820s).”

Where the river flows 2021 inkjet on photo paper

Arc One Gallery

郭健在中国出生长大,但自 1992年以来一直在澳大利亚生活工作。他通过 艺术讲述自己的经历和现实故事。郭健本人和他的艺术是中国过去 50年暴 力和动乱的产物,从 20世纪 60年代和 70年代的文化大革命,到 20世纪 80年 代初的中越战争,再到天安门广场事件的恐怖。郭健的艺术不是为了说教

或改变他人,而是从政治宣传和艺术这两个角度展现自己观察到的世界。

通过身处中国政治宣传体系内外的第一手视角,他看到了中国和西方在“ 说服”这一概念上的许多共同点。

郭健的作品曾在德国、法国、比利时、瑞典、美国、墨西哥、澳大利亚、 新西兰、香港和中国展出和收藏,包括法国皮卡第博物馆、比利时布鲁塞 尔艺术节、悉尼白兔画廊、新南威尔士州美术馆、昆士兰州美术馆和澳大 利亚国家美术馆。《艺术家简介》、《纽约时报》、CNN、《悉尼先驱晨

ABC广播和电视公司等媒体均有对他进行报道,他还作为 封面人物登上《亚洲华尔街日报》杂志周末版。郭健的经纪公司为悉尼迪 法恩画廊和墨尔本Arc One画廊。

每当我打开电脑搜索澳大利亚早期移民的故事,除了无数关于早期移民的 艰辛、毅力、勇敢和开拓边疆的图片和资料之外,还会看到许多纪录片和 讽刺画,记录了对澳大利亚原住民的屠杀以及对中国移民的种族歧视。然 而随着我继续翻动网页,夹在这两者之间的是那些古典美丽的欧洲殖民风 景画。

然而在社交媒体和现实生活中,令人震惊的是,我们可以看到和听到与这 些历史相关的保守、极右、种族主义甚至法西斯主义评论,因此我想把 历史上发生的这一切——苦难、流血、歧视和傲慢——变成一幅美丽、经 典、殖民风格的风景画,让观者感受到这似乎已成为遥远过去的悲伤。这 幅繁复的照片拼贴画以A.W.F .富勒的铅笔素描《新南威尔士利物浦附近的 乔治河风景》(约1820年创作)为参考而作。

Where the river flows 2021 inkjet on photo paper (detail)

河流流动的地方 2021

在照片纸上喷墨 借自艺术家, Arc One Gallery 提供

Lindy Lee’s practice explores her Chinese ancestry through Taoism and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism – philosophies that see humanity and nature as inextricably linked. She employs chance and spontaneity to produce a galaxy of images that embody the intimate connections between human existence and the cosmos. Her works are meditative, often revealing themselves through time.

‘In my earlier artwork, I’ve made reference to the Western canon of portraiture and questioned notions of authenticity and belonging, using imagery from family photo albums to explore the experiences of loss and transition that have spanned five generations of travel from China to Australia.’

Regarded as a hugely significant and influential Australian artist, Lindy Lee’s career spans almost four decades. Her work is in most major Australian public collections and her public art can be found throughout Asia, North America, Europe and the Middle East. Lindy Lee is represented by sullivan + strumpf, Sydney.

“His gaze meets ours, deep and clear and steady. In his face I see sadness, resignation, determination. Resilience. Tiy Sing, a Kogarah market gardener who prospered enough to buy his own truck, is hoping to make a trip home to China and, with this document, be allowed re-entry to Australia on his return.

I am captivated by his ID photo: a single unknowable instant in a person’s life. His gaze invites us to be curious, to seek beyond the surface reality of paper and print, to witness his interiority.

I understand the significance of this document because recently, I came across my grandfather, Lee Foy’s, own Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test. Tiy Sing and Lee Foy, born two years apart, were contemporaries in Sydney in the early 1900s. Perhaps Tiy Sing sold produce to my grandfather, who owned a Chinese restaurant called The Red Rose in Lidcombe. But even if they didn’t know each other, still they were fellow travellers.

Because they’d been residents of Australia prior to the introduction of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, otherwise known as the White Australia policy, both Tiy Sing and Lee Foy were entitled to exemptions from the cunningly cruel Dictation Test. Newly arrived Chinese, however, faced this test. In order to pass and be permitted entry, they had to write 50 words in any European language – not necessarily English, it could be Italian, or Lithuanian - as specified and dictated by an immigration officer. A perfect piece of racist spite on the part of the Australian government.

In 1973, one hundred years after Tiy Sing’s birth, the White Australia policy was finally dismantled. I was 19 years old then. These certificates exemplify the oppressive rules of exclusion in Colonial Australia – but the tentacles of racism reach into our present era.”

李林迪从道教和禅宗的角度对自己的华人血统进行艺术探索。道教和禅宗 的哲学认为人类和自然间有不可分割的联系。她的视觉创造过程由巧合和 自发性主导,这些视觉艺术是对人类存在和宇宙之间密切联系的展现。她 的作品如冥想一般,通常需要一些时间才会慢慢揭示其内涵。

“ 在我早期的作品中,我参考了西方肖像画的经典,对真实性和归属感的 概念提出质疑,通过使用家庭相册中图像的表现形式,来探索从中国到澳 大利亚五代人迁居过程中的失落和过渡的经历。”

40年,在澳大利亚是一位非常重要且有影响

力的艺术家。她的作品被多数主要澳大利亚公众机构收藏,她的公共艺术 作品遍布亚洲、北美、欧洲和中东地区。李林迪的经纪公司是悉尼sullivan + strumpf公司。

The market gardener & the restaurateur 2021 Chinese ink, giclee print on cold pressed archival paper, fire (detail)

菜园园丁和餐厅2021

中国水墨,冷压档案纸上的数字墨喷印画,火 借自艺术家

他与我们目光交汇,深邃、清澈、坚定。在他的脸上,我看到了悲伤、无 奈、决心,还有坚毅。Tiy Sing是Kogarah

钱,买了自己的卡车。他希望能回中国一趟,并希望在回来的时候,带着 这个文件就能获允再次进入澳大利亚。

他的身份证照片彻底抓住了我的心,这是一个人生命中一个不可知的瞬 间。他的目光引人好奇,激发人超越纸张和印刷品表面的现实,去见证他 的内在。

我理解这份文件的重要性,因为最近我偶然发现了我祖父Lee Foy自己的听 写测试豁免证书。Tiy Sing和Lee Foy出生相隔两年,是20世纪初悉尼的同 代人。也许我祖父在Tiy Sing那里买过菜?祖父在Lidcombe开了一家中餐 馆,叫“红玫瑰”。但即便他们彼此不相识,他们仍是同路人。

因为在《 1901年移民限制法案》,也就是“白澳政策”出台之前,他们就 已经是澳大利亚的居民了,所以Tiy Sing和Lee Foy都有豁免权,可以不参

加残酷狡诈的听写测试。然而,新来的华人移民面临着这个考验。为了通 过测试并获准入境,移民必须用任何欧洲语言听写出 50个单词,不一定是 英语,可以是意大利语或立陶宛语或其他,由移民官员指定和口述听写。 这是当时澳大利亚政府种族主义恶意的完美体现。

岁。

1973年,在Tiy Sing出生一百年后,白澳政策终于被废除。那时我19

这些证书充分体现了澳大利亚殖民时期排外压迫的法规 然而种族主义 的阴暗触手依然延伸到了我们现在的时代。

Xiao Lu (b.1962, Hangzhou, China) is a contemporary artist known for her performances. In 1984, she graduated from the High School of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1988, from the oil painting department of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Fine Arts) in Hangzhou. At the end of 1989, she came to Australia and acquired Australian citizenship in 1997. From 1997 to 2020, she lived and worked in Beijing and Hangzhou. Currently she lives and works in Sydney.

Her practice shows the various stages of her development, from a young female artist resisting attacks on her personal freedom and dignity, to a mature woman with a feminist consciousness and social awareness. Arising from her personal experiences and reflections on human emotions and social conditions, her work is about the search for and expression of true freedom.

Recent exhibitions include: Democracies TATE Liverpool, UK (2020); Collection Galleries: 1970s - Present, MoMA, New York, USA (2019); Skew, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong (2019); Xiao Lu: Impossible Dialogue, 4A Centre Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, Australia (2019); Collection Displays: Performer and Participant, TATE Modern, London, UK (2018); Her Kind, Zhuzhong Art Museum, Beijing, China (2018); Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World, Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA (2017). Xiao Lu’s works have been collected by major international public institutions including TATE Modern, London; MoMA, New York, USA; the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the National Gallery of Victoria.

“It is not because there is hope that we resist, but only if you resist can there be hope… the people of Hong Kong.

In 2019, Hong Kong was on fire. This unforgettable memory bore witness to the fracturing of an era. For 30 years, candles for June 4 have been lit in Victoria Park. To defend the home of freedom, democracy, and the rule of law, the people of Hong Kong moved heaven and earth with their outcry to boost their courage. This city of heroes loudly sang out: “Glory to Hong Kong!”

June 4, 2019 was the first time I took part in the June 4 candlelight vigil rally in Victoria Park, Hong Kong. I was shattered, moved, ashamed. Afterwards I focused on the protest marches in Hong Kong against the China extradition bill. The spiritual force of the people of Hong Kong inspired my soul to photograph, to create video and perform, immersing myself and witnessing this history was unforgettable. The works presented commemorate that the Hong Kong June 4 candlelight vigil was not extinguished for 30 years, and the resistance of the Hong Kong people in 2019. At the same time, it also commemorates the Australian government’s granting of humanitarian asylum to some 42,000 Chinese citizens because of the Tiananmen incident of June 4,1989. I was one of those recipients.”

Remember 3: Skew, performance, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

September 2019

video, total duration: 3 minutes

Chancery Lane Gallery

肖鲁( 1962 年生于中国杭州),著名当代表演艺术家, 1984 年毕业于中 央美术学院附中, 1988 年毕业于杭州浙江美术学院(现中国美术学院) 油画系。她于 1989 年底来到澳大利亚,并于 1997 年获得澳大利亚公民身 份。 1997 年至 2020 年,她在北京和杭州两地生活工作,目前她在悉尼定 居,从事艺术创作。

她的艺术展示了她的个人成长历程,从最初捍卫个人自由和尊严的年轻 女性艺术家逐渐成长并成为了具有女权和社会意识的成熟女性。以个人 的经历和对人类情感和社会条件的思考为核心,她的作品是对真正自由 的表达和探索。

其近期展览有:英国泰特利物浦《民主》( 2020 年)、美国纽约现代

艺术博物馆收藏展:《 20 世纪 70 年代至今》( 2019 年)、香港大法官

道 10 号画廊《歪曲》( 2019 年)、澳大利亚悉尼 4A 当代亚洲艺术中心

《肖鲁:不可能的对话》( 2019 年)、英国泰特现代美术馆收藏展:

《Performer and Participant》(2018年)、中国北京珠中美术馆:《Her

Kind 》( 2018 年)以及美国纽约古根海姆博物馆《 1989 年后的艺术与中

国:世界剧院》( 2017 年)。肖鲁的作品由包括伦敦泰特现代美术馆在 内的主要国际公共机构收藏,作品还收藏于美国纽约现代艺术博物馆、 新南威尔士美术馆以及维多利亚国家美术馆。

Remember 2: protest march against the China extradition bill, Hong Kong

Photo taken 15 September 2019, printed 2021

digital print

不是因为有了希望我们才反抗,而是因为只有反抗才有希望……香港人 民。

2019 年,香港满城烟火,这段难忘的记忆见证了一个时代的终结。 30 年 来,每逢 6 月 4 日维多利亚公园就会有点燃的蜡烛。为了捍卫自由、民主 和法治的家园,香港人民用他们的呐喊感动了天地,鼓舞了勇气。这座 英雄之城大声高唱:“荣耀归于香港!”

2019 年 6 月 4 日是我第一次参加香港维多利亚公园的六四烛光守夜集会, 我感到震撼、感动和惭愧。后来,我把重点放在香港反对中国引渡法案 的抗议游行上。香港人的精神力量激励着我的灵魂去拍摄、去制作视 频、去行动。身处其中见证这段历史令人难以忘怀。展出的作品纪念香 港六四烛光守夜 30 年不灭,也是对 2019 年香港人民的反抗的纪念。与此

同时,也是对澳大利亚政府因 1989年 6月 4日天安门事件向大约 42000名中 国公民提供人道主义庇护的纪念,而我就是这批人其中的一员。

2019年9月15日拍摄, 2021年印刷 数字打印

记忆

2:游行抗议中国引渡法案,香港,

Jason Phu’s multi-disciplinary practice brings together a wide range of sometimes contradictory references from traditional ink paintings to street art, everyday vernacular to official records, personal narratives to historical events. Working across installation, painting and performance, Jason frequently uses humour as a device to explore experiences of cultural dislocation. Simultaneously he uses stories of ghosts, spirits, demons, and gods as a personification of these concepts.

Jason has shown in the Dobell Drawing Biennale, Art Gallery of New South Wales (2018); The Burrangong Affray, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (2018); Primavera (2018); Young Australian Artists, Museum of Contemporary Art (2018); and was commissioned by the Sydney Opera House for the 2019 Art Assembly Commission (2019). This year he is showing in The Way We Eat at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and is an artist for the arts festival Rising in Melbourne. He is represented by Station Gallery, Melbourne and Chalk Horse, Sydney.

“The important thing for us to remember is that whatever ingredients are available, we can cook them in the Chinese way.” R. Geechoun - Cooking the Chinese Way, 1948.

“Zan drove me from Sydney to Melbourne when Sydney turned into a Covid OrangeZone. I stayed with her and her partner (and two lovely dogs) in Melbourne while we waited for our test results and saw a book on her counter, Cooking the Chinese Way.

I’d seen a first edition was to be included in this exhibition and had wanted to look at it before I left for Melbourne but had run out of time while making the dash for the border. Zan offered to give me the book - it had been left to her by her father. She made me a sauerkraut and cheese sandwich while I leafed through the book.

I had spent the year with my parents during lockdown in Sydney, the longest I’d stayed with them since I was 19. My mum used to cook for us when I was a kid, she never enjoyed it as a part-time worker and housewife. Dad always loved cooking but worked too long hours to ever get around to it. Since dad retired, he cooks every day now and mum’s rediscovered her love for cooking. She is ‘relearning’ all grandma’s recipes from Beijing. She finds the recipes on WeChat rather than asking grandma because laolao passed away a few years ago.

There is only today to eat a meal, tomorrow we can cook something different, and the day after that who knows where we will all be 2021 video stills

Grandma passed at the ripe old age of 93, having smoked a pack-a-day since she was 16. For her, every meal past breakfast was meticulously planned and budgeted in her ruled notepad, only the best (within budget). Breakfast was a mantou with some fermented tofu and a thin menthol cigarette over the latest world billiards championships or English premier league, whatever was in season.”

只有今天吃一顿饭,明天我们可以煮一些不同的东西,后天谁知道我们2021年会在哪里

符子龙的多学科专业背景经常会汇集各类元素,从传统水墨画到街头艺 术,从日常白话到官方记录,从个人叙事到历史事件,这种有时相互矛盾 的形式构成了他艺术的特殊风格。无论是布展艺术作品、绘画还是表演, 符子龙经常使用幽默来探索文化错位的经历。同时,他用鬼魂、灵魂、恶 魔和神灵的故事来赋予这些概念具象化的表现形式。

符子龙的作品曾在新南威尔士州美术馆多贝尔绘画双年展(2018年)、4A 当代亚洲艺术中心的《布朗贡斗殴》展( 2018年)以及当代艺术博物馆的 Primavera 2018:澳大利亚年轻艺术家展(2018年)上展出,并受悉尼歌 剧院委托为 2019 年艺术大会委员会( 2019 年)创作。今年他的作品《 The Way We Eat》在新南威尔士州美术馆展出,并且作为艺术家参加墨尔本艺 术节“Rising”。他的经纪公司为墨尔本Station画廊和悉尼Chalk Horse。

“我们要谨记,不管能有什么原料,都能做成中餐。” R. Geechoun《中式 烹饪》,1948年。

悉尼被定为新冠橙色疫区后, Zan 开车把我从悉尼送到墨尔本。到了墨尔 本,我和她还有她的伴侣(以及两只可爱的狗)呆在一起等测试结果时, 在她的柜子上看到了一本书,名叫《中式烹饪》。我希望展览中有这本 书的首版,并想在去墨尔本之前读一下,但在奔向边境时已经没有时间

了。 Zan 主动提出把书送给我——这本书是她父亲留给她的。我翻着看的 时候,她给我做了一个酸菜奶酪三明治。

悉尼封城期间,我跟和父母一起住了一年,这是我 19岁以来和他们呆在一

起时间最长的一次。小时候我妈妈经常给我们做饭,她从来没有喜欢过边 做兼职边当家庭主妇的生活。爸爸虽然喜欢烹饪,但工作时间太长,根本 没时间去做,但自从爸爸退休后,他每天都做饭,妈妈也重新找回了她对 烹饪的热爱。她在北京“重新学习”了姥姥的所有食谱,不过她是在微信 上找食谱,而不是问姥姥,因为姥姥几年前去世了。

姥姥从16岁开始每天抽一包烟,直至93岁高龄去世。姥姥除了早餐以外,

There is only today to eat a meal, tomorrow we can cook something different, and the day after that who knows where we will all be 2021 video stills

只有今天吃一顿饭,明天我们可以煮一些不同的东西,后天谁知道我们2021年会在哪里

视频剧照

借自艺术家,Chalk Horse提供

之后每一顿饭都是精心计划,都会在她的笔记本上做好预算,而且只吃 (预算内)最好的。早餐是馒头加点豆腐乳,再来一根细薄荷烟,旁边播 放着世界台球锦标赛或英超联赛,有什么比赛就看什么。