6 minute read

Foxfire

“A Salute to the Vanishing Mule” June 1968

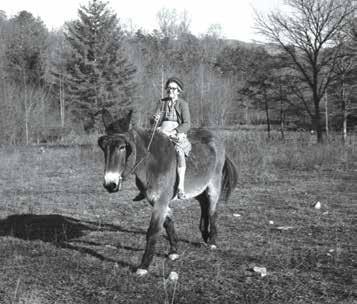

Billingsley plowing with a mule

George Burch & Mickey Justice

Adapted by Kami Ahrens

We assumed that nothing was amiss in the mule world until we were informed that their position of prominence had been blasted forever by the Industrial Revolution. “After all,” our friend continued, “when was the last time you saw a young mule?” That got us thinking. Were mules following oxen into extinction? The result was the following study which we hope you will find as interesting as the subject was to research. At one time, the mule was king. Mrs. Ada Kelly shared some of the important work mules did: “[The mule] helped clear timber so that agricultural products could be planted. It helped drag logs off the land for building houses and barns, and hauling the logs to building sites. After they began sawing logs, the mule was busy dragging logs out of woods and hauling them to the mills. After they were sawed, they were loaded on wagons and pulled by mules many miles to some place where they could be readied for building houses. Then the faithful old mule would haul the lumber back to building sites. In his spare time, he plowed land, and helped to get the planting and cultivating done. He was there to help harvest and haul the crops. Everything that was too heavy to be moved from place to place by man was moved by the mule. In the horse and buggy days, it was most often mules instead of horses that was hitched to the buggy. It was always convenient to hitch up the mule or put a saddle on him to go to anywhere that was too far to walk.”

Mules also pulled reapers, combines, and potato diggers; snaked logs for tan bark and telephone poles; plowed; worked sorghum mills; carried mail—the list is endless. Some mules were so well trained that they could haul sugar and malt to mountains stills alone and then walk back out alone laden with the finished moonshine.

Farms in Kentucky and Tennessee specialized in breeding them. Their young mules were sold in places like Franklin, North Carolina, where Mr. R.L. Edwards’s uncle paid $400 for an untrained pair—and that in a day when money was worth considerably more than it is now.

Many farmers began breeding their own mules. Mr. Grover Wilson told us that some mules raised in this county were huge. Mr. Bill Blalock’s grandfather had a pair that weighed 2700 pounds. There were two or three “jacks;” these were carried to farms by request and bred to farmers’ mares. After the mare foaled, the breeder would come back and collect a $10 fee. Local farmers thought that the mules from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri—though bigger—were not as tough as the smaller “mountain mule.” Even farmers in the cotton belt often preferred the mountain mule for its stamina. Esco Pitts, the Farm Supervisor for the Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School, said when he arrived in 1909, the school had two mules named Pete and George. Before long, they added six more. The school was almost run by mule power: the sorghum was ground using mules, foundations and basements were dug out using mules, everything that had to be hauled, such as corn or rye, was hauled with mules.

They cultivated 200 acres at the school and he can remember seeing eight mules at a time in the fields, each followed by one of the students. In the spring, the mules dragged the cutaway harrows out into the fields and readied them for seed. Then the rows were laid off with a mule-drawn “shovel plow” or “laying off plow,” and the planting would commence. Idyllic as it all may sound, the use of mules was slow, grueling labor. Mules had to be fed daily and equipment such as plow points had to be kept in perfect shape. And even the best mules could only cultivate four acres a day. With 200 hundred acres to be worked—well, figure it out for yourself. Conversations with other farmers turned up other disadvantages: Mules get tired. Tractors don’t. After two or three good rows, you have to rest both the mule and the man behind him! Mules are far more expensive than most people will admit. Mr. Wilbur Maney, the county agent, told us, “A mule costs about a dollar a day, adding in repair for the equipment and shelter for the animal during the winter. That makes about $365 a year. Nowadays for the same price, you could buy a Sears Roebuck tractor that would do the same amount of work and do it faster. Whereas a mule can only plow an acre or two a day, a tractor can do the same in about thirty minutes.” Another farmer in the county added, “Nowadays most farms have to be business ventures and mules just aren’t good enough when compared to today’s prices for labor.” Maude Shope riding Frank

Considering the disadvantages listed above, it is no surprise that the tractor sealed the fate of the mule. Mr. Pitts remembers that the Rabun Gap-Nacoochee School switched over to tractors almost immediately. When asked if he was sorry to see them go, Mr. Pitts replied, “No, not at all. They were a tremendous amount of work.”

Mr. Maney dug into his United States Census of Agriculture books for us and came up with concrete documentation for the fall of the mule in Rabun County. The statistics read: “In 1950, there were 476 farms using a total of 740 farm animals—mules and horses.”

But only nine years later, in 1959, there were only “96 farms using only 137 horses and mules.” There are no figures available for the situation today. Mr. Pitts said, “You won’t find two dozen mules in the county I don’t guess.” Mr. Wilson agreed. He knows almost every farmer in the county and he had trouble coming up with 15 mules. The farmers we talked to who still used mules offered a variety of reasons for keeping them: “Mules don’t pack the ground like a tractor does;” “My land is too steep for a tractor, and mules don’t slip;” “They cultivate better and cut deeper in to the ground;” “When plants are young, mules don’t cover them up like tractors do. You have better control;” “I already have the equipment I need for a mule. I’d have to buy all new equipment for a tractor and I can’t afford it. Anyway I’ve already got the mule and it’s not costing me anything.” Other farmers were just reluctant to change. The mule had become a part of the landscape and part of the family. One said, “The only reason I keep it is because I have it!” And Mr. Wilson gave one of the best reasons of all: “I really only use it once a year, and in terms of dollars and cents it probably isn’t worth keeping. And I have a tractor. But look, I’ve always been used to having one, and fact is, I like to handle ‘em in a garden.”