PARAGON

vol. 45 | 2024 | Gilman School | Baltimore, MD

Editors-in-Chief

Trey Taylor

Nathan Cootauco

Literary Art Editor

Ethan Yan

Visual Art Editor

Ellis Thompson

Managing Editor

Jameson Maumenee

Review Board

Ben Barish

Neel Behari

Bohlen Brooks

Dylan Buchalter

Matthew Chi

Thor Cohen

Joe Hutzler

Vivek Raghavan

TJ Reiter

Jay Salovaara

Ambrose Smith

Bo Vaughn

Rohan Vesely

Faculty Editors

John Rowell

Arnisha Royston

Rebecca Scott

Karl Connolly

Karaline Johnson

This issue of Paragon is in memory of Mr.

Francis“Boo”Smith Dean, Coach, Educator

“Do the right thing.”

Owen Pu‘24

Buck Franklin‘24

Leo Eiswert‘26

Nick Lutzky‘24

Truman Paternotte‘24

Nathaniel Frempong‘24

Francis Beam‘25

Paul Shkolnik‘24

Ben Barish‘25

Oliver Beattie‘24

Ryan Collins‘24

Cal Hickey‘24

Nikhil Gupta‘26

Phineas Schanbacher‘25

Joshua Turner‘26

Travis Dutton‘24

Francis Beam‘25

Noah Peters‘24

Thomas Lee‘24

Timothy Edwards‘25

Daniel Koldobskiy‘24

Jameson Maumenee‘24

TJ Reiter‘24

Nathan Cootauco‘25

Ethan Yan‘24

Bruno Becker‘24

Henry Jeanneault‘25

Neel Behari‘25

Thomas Lee‘24

Ellis Thompson‘25

Timothy Edwards‘25

Max Shein‘26

Noah Peters‘24

Dylan Moyar ‘26

Luca Mulligan‘27

Grayson Mickel‘25

Luca Mulligan‘27

Liam Digges‘27

Michael Edwards‘25

Nathan Cootauco‘25

Jack Bennett ‘25

Finn Tondro‘24

Paragon is an honored recipient of both a 2022 & 2023 NCTE REALM First Class magazine award

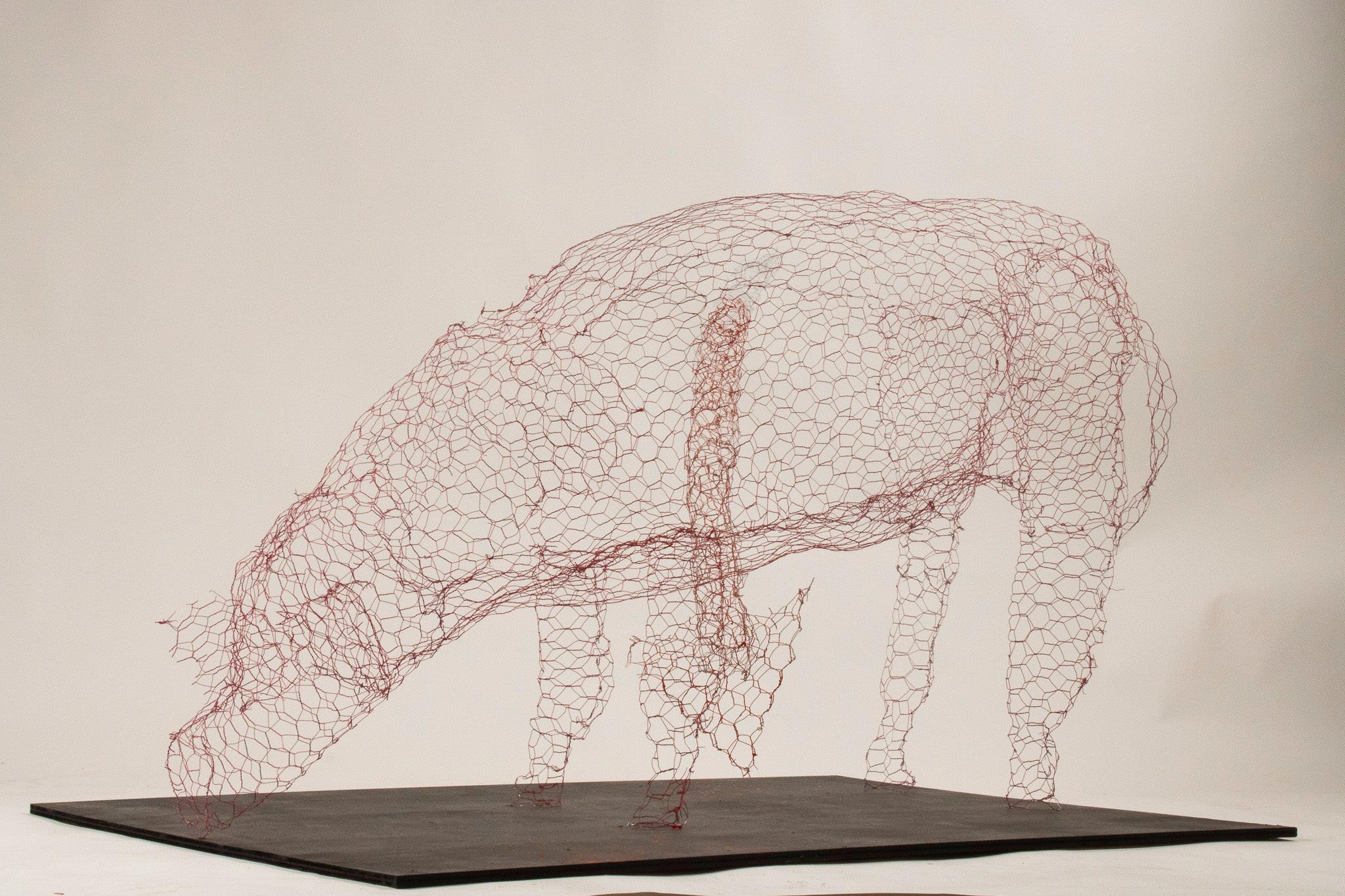

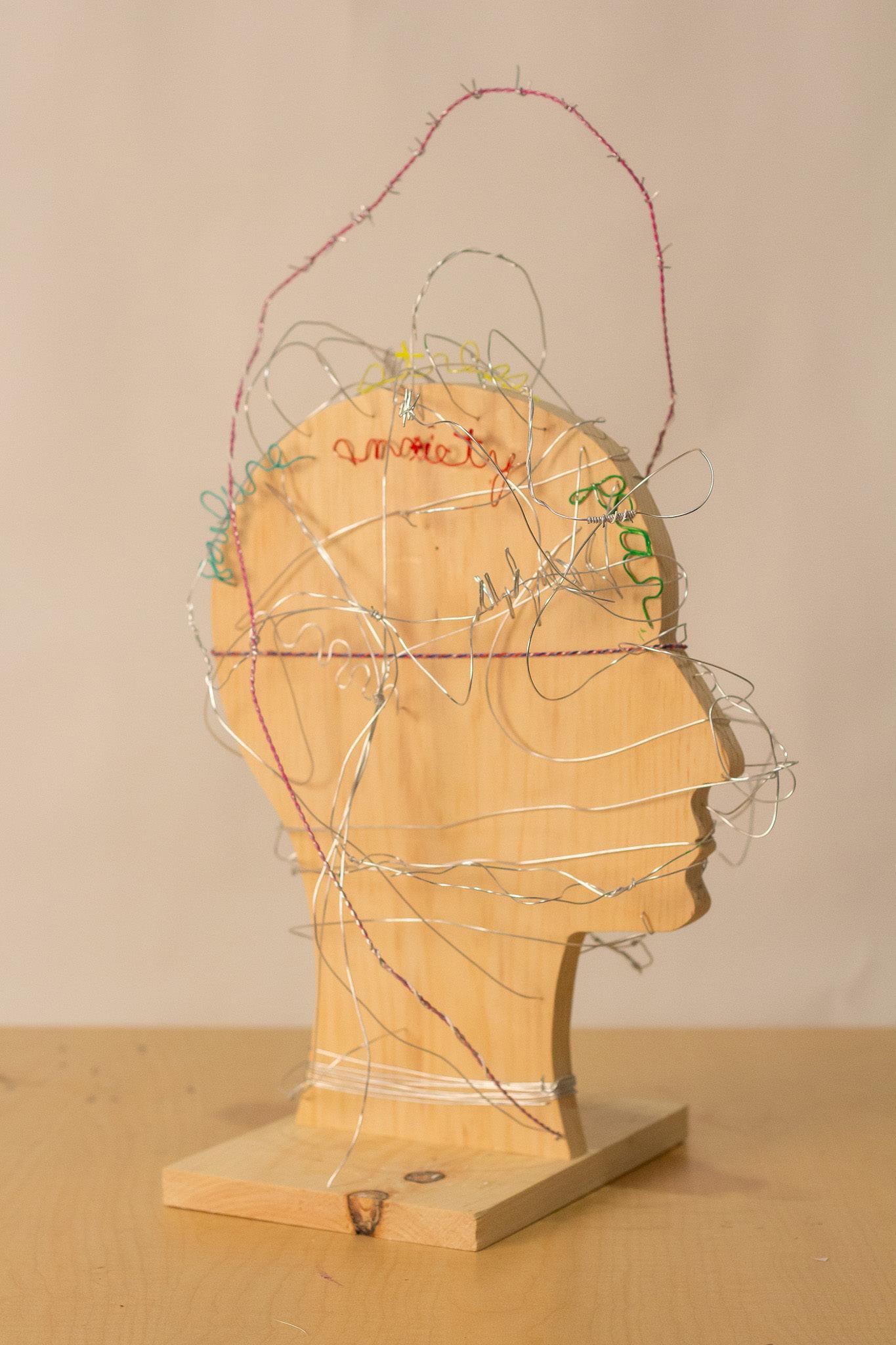

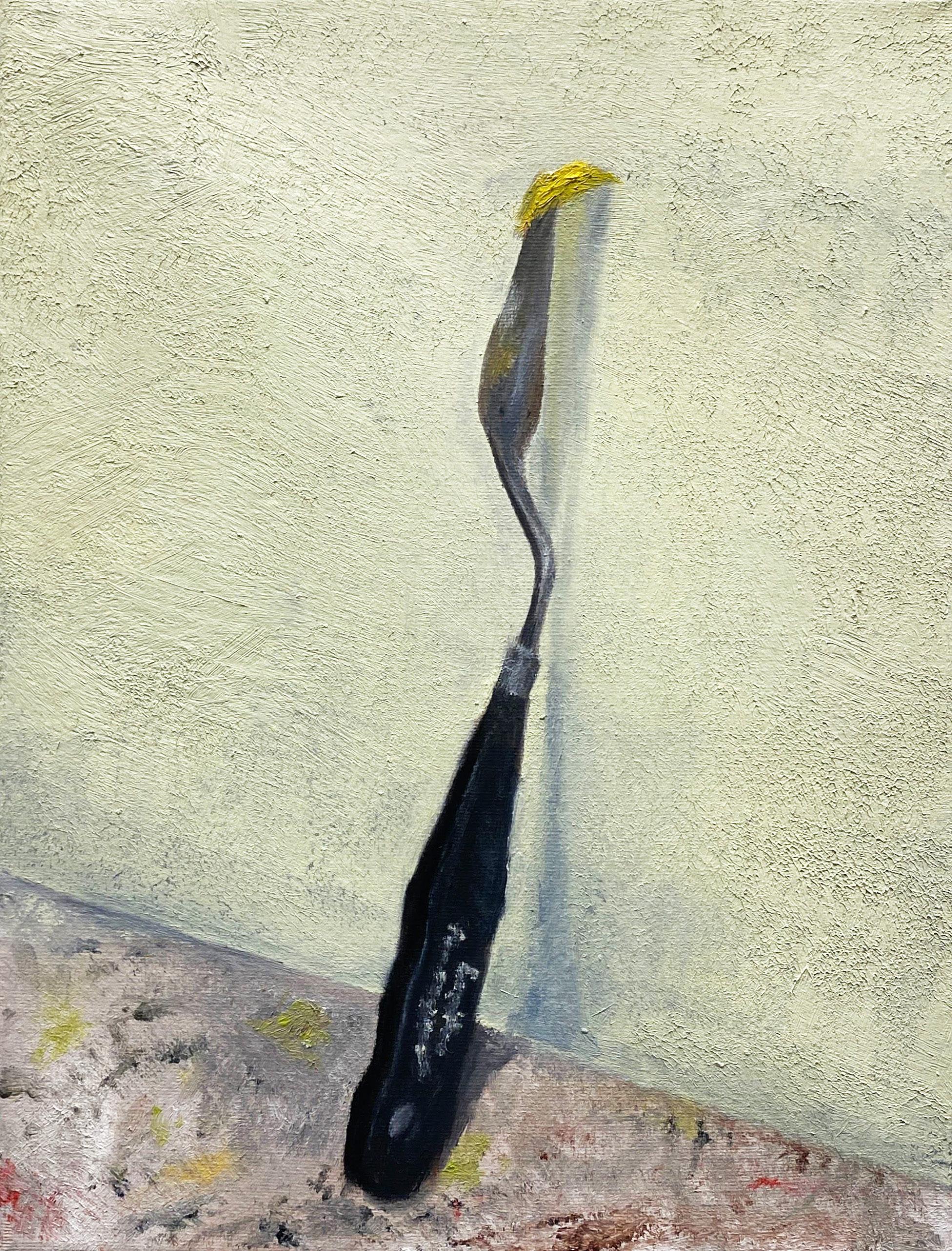

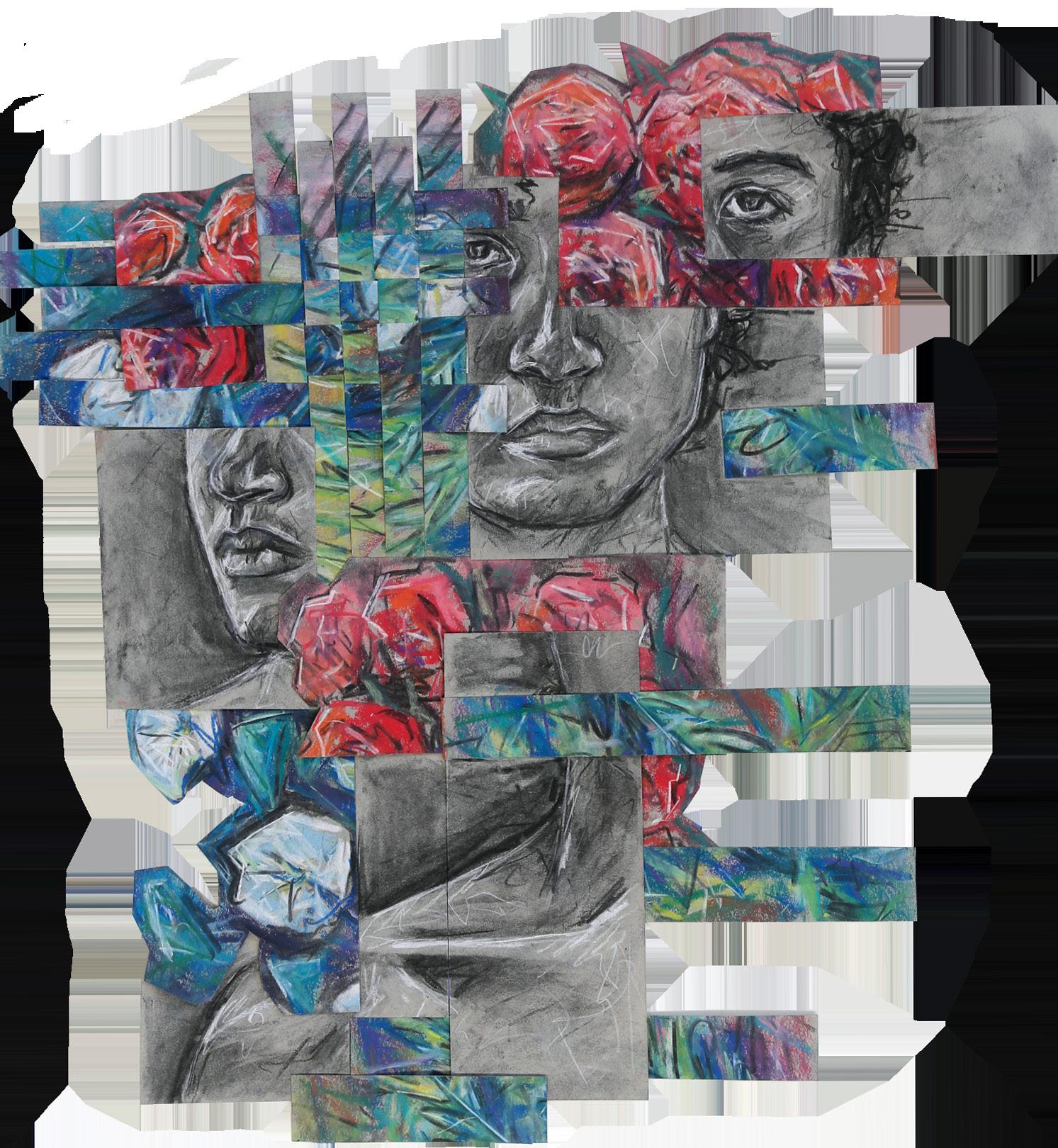

By the grace of many assembly announcements and occasional email reminders, this issue of Paragon slowly and elegantly emerged from the year’s pool of nearly 200 submissions. With this final, physical copy in your hands, a world of literary and visual art awaits; a compendium which characterizes Gilman and captures the skill and expertise of the community of which we are a part. Through sculptures that explore modern day issues and struggles, through paintings, drawings, and photographs that push boundaries and capture the beauty of form, landscape, and figure, and through writing that challenges you to think and feel as you read, we hope to redefine the framing of the“high school artist”into what it should be:“artist”.

I’d like to first thank everyone who submitted to Paragon and allowed us—certainly no experts—to review and curate the artistic endeavors of the student body. Your contributions were invaluable to the spirit of the magazine, and guided our decisions and inspiration. I’d also like to thank the editorial staff for your unwavering faith, your knowledge, and appreciation for the arts which kept us on the path to success. I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to work with such an amazing group of people, and I won’t soon forget the hours of copy-editing, proofreading, layout formatting, and laughter by your side.

The bees in this issue were hand painted after those found on the Gilman school shield. This symbol, one which really took off this year in popularity (pun intended), represents industry and community, two core aspects of the school that keep Gilman strong and connected. As it happens, Paragon would not be possible without you, the community, who creates, submits, reads, views, and hopefully enjoys this year’s magazine. I hope that through the art that lies ahead, and the bees occasionally buzzing throughout, you may see yourself within the pages, understand how special this community is, and recognize your greatness within it.

Trey Taylor Editor-in-Chief

Nick Lutzky‘24

He thinks, which means he’s awake.

The man begins his day with soft exhales through the nose: In, Stop—Out. In, Stop—Out. Regulation of breathing is imperative to survival at seventy degrees below freezing. Experience had taught him better than any school or book could have, although strict and punitive in her ways. Through trial (necessity) and error (frostbite), he learned to respect the cold and its rules—cover exposed skin, stay dry, stay inside unless absolutely necessary—or die in defiance of them. Freezing is not the worst way to die.

The first thing he must do is dress. Though his cabin is warmer than the tundra, cold still finds a way inside, requiring an additional vestimentary warmth. The night had not been so bad, though, for it was far worse in the winter. Spring was never easy, but in winter, men learn what cold is. During those times he slept in the day when it was warm enough to lie down. At night, he paced back and forth, forcing himself to stay awake because if he were to sleep, he knew he would not wake. Still, he preferred the quiet solitude of winter to louder summers, falls, and springs. But even in spring it is far from warm (especially this early into the season), and insulating his body is imperative: thermal underwear, a cotton insulating layer, and an outer jacket. He did not wear goggles, preferring to see things with his naked eyes.

After dressing, he must stoke his fire. He collects wood in the summer, just as he had built his cabin in the summer. In fact, he does most things in the summer. He spends his other seasons with the cold. It was not warm in the summer by any means, but the man did not believe it was truly cold. Real cold, as he saw it, reminded one of their humanity.

This all takes him roughly an hour, and is rigidly planned to fit such a time frame. Scheduling is important, both to minimize time outside and to ensure such time is spent in the prime hours of the day. With this routine complete, he can step outside.

As he opens the door, the world is gray and the ground is white. A sharp glare hits his eyes as he preemptively raises his mittened hand to block the intrusion. He nods; it is time to check his traps. Fifty-two snares surround his cabin, but there is little game this time of year, so the prospect of large game is doubtful. He will likely find a rabbit, maybe two. This is enough for him to survive another day. You can eat very little and persist if sedentary, but survival requires maintenance, and maintenance requires food.

In, Stop—Out. In, Stop—Out.

He muscles through the snow. Patience, too, is imperative to survival. Twenty-four empty traps in and the man remains largely unfazed. Frustration is a fatal waste of energy. Instead, he keeps the same stoic face he’s had at every gameless junction and continues on. Emotional expressions serve little value at seventy degrees below zero. A thin layer of crystallized ice covers exposed skin; in this case, the small parts of face the man left uncovered. Stretching of facial muscles (yawning, smiling, frowning) could shatter this layer, which has proven to be excruciatingly painful. Opening the mouth is equally dangerous; exposing saliva to the frigid air for too long causes it to freeze inside the mouth—again, terribly painful.

He trudges along, following his trail markings from trap to trap. They are crude wooden planks, erected in snow and adorned in different colors corresponding to each trail. He follows the Red trail. Though shoddy in appearance, these trail markings were meticulously constructed, maintaining shape even in the harshest of conditions.

His gait is similar; though peculiar in appearance, he walks with careful attention to each step. Below him are riverbanks. Vast networks of streams, lakes, and flowing water are covered by layers of thick ice, having not seen the light of day for hundreds of years, not since a time that was kinder to them. But ice is tricky, as while it may hold ten feet in one spot, it only takes ten paces before the man could find himself standing on ten centimeters of ice. Contact with water that cold is deadly, and entails dire consequences, even with a quick response. This lesson was learned at the cost of three toes, a merciful punishment to the man. Each step is planned, as he knows the route by now and knows which steps to take and where. Still, ice is tricky, and the feeling of it cracking under him was already committed to memory such that, on this day, he knows, with complete assurance, that the ground is about to give way.

In, Stop—Out— In, Stop—Out.

Patience is imperative. Frustration is fatal. His thoughts do not race; they sprint into careful formation. His thoughts know exactly where to go, his thoughts have been preparing for this moment for years. He knows it is not safe to run, doing so would only hasten the process. No, he needs to maximize his surface area—in order to spread out his body weight as much as possible. Quickly, but not hastily, he drops to the ice, making contact with the thin layer of powder first before feeling the floor below him: marble-like. Powder sticks to his face, biting at his skin in excruciating fashion, though he dare not scream. His face is still. The cracking slows. The ice will not give way.

He curses himself for haste, doing so silently and in a manner indecipherable to an onlooker. His face remains still. Splayed about the ice with his arms and legs scattered about, he knows there is little time for self-pity or criticism. He must evaluate the situation and act.

In—Out. In—Out.

Firstly, he knows his face is damaged. Exposed to the snow lying atop the ice, larger crystals begin freezing on top of his beard and at the seal of his lips. He can no longer open his mouth, even if he wanted to. This could be remedied if he heated himself quickly; he needs to get back to the cabin. At this point, he would be lucky not to lose part of his face. He knows there is thicker ice to his west—ice he can hopefully stand on. Like a deer being dragged by an invisible hunter, the living carrion inches westward. But as he moves, shooting pains spread across his face. Ice particles, sharp as they are tricky, cut into his left cheek and forehead, painting his face with cruel mosaics of blood, frost, and water.

InOut—InOutInInIn—OutOutOut.

Blood is less than ideal. While it takes longer to freeze than water, it mixes especially poorly with ice. Crystallized ice and blood alike drip into his eyes. Instinctually, he blinks—a fatal error. The blood and ice coagulate at the seams of his eyelids, sealing them shut. Had he a mouth, he would scream. Just once.

But he collects himself nonetheless, scooting a dozen or so feet west before stopping. He has little way of knowing the depth below him at this point outside his interior map—standing up is a play at fate. But he is tired. Were he to die here a thousand times standing, it would still be better than to die once, lying.

He stands quickly and intentionally. The sky is quiet. The ground does not move, he plants his feet firmly below him. The carrion is a mangled, fantastic, bloody mess. Had he a mouth he would smile. But the man’ s face is still as he walks towards the cabin; he will have to check the rest of his traps tomorrow.

Nathaniel Frempong‘24

I got bored.

Dropped a Mento in a bottle

Watched it freefall the same way

Shattered dreams plummet.

Isn’t that what we do anyway?

Sacrifice our bodies to accomplish a goal

Telling ourselves

Pain will dissolve

Into nothingness

It doesn’t.

It fuels—

Coke swells

My breath slows

Patiently waiting for the inevitable

Promised amusement

Rushes forth and rescinds like

A wave of dopamine on a fixed timer

Bound to retract

Collapsing in upon itself

Until...

But there’s no explosion?

It just sputters out

Nothing’s left.

Francis Beam‘25

I am the Father of the Garden,

Shaping trellises from ligaments and pergolas from bone

Spinning coats of hair to brace for frost

Watering dormant seeds with tears.

I am present at the earliest green of germination, Cutting weeds with nails, divorcing root from ground

Fertilizing crops with the scalp’s oils

Sewing a fence from grafts of skin.

I am ready for the day of harvest,

Lying in the soil with mud-caked soles

Assembling stems and roots into capillaries

Passing nectar into blood, when catnip blooms.

Ryan Collins‘24

*Before reading this poem, the author suggests listening to the sound of a loon’s call

The scary, ghostly call echoes from the sun-stained lake. It’s dusk: shadows lengthen the sky blushes staring in wonder after another beautiful day On Golden Pond. The next morning, again, she calls I’m drawn to her source, her wonder.

The screen door creaks as I close it, letting the sprawling life know my presence.

Following the leaf-covered, camping-seasoned trail I make my way to her voice, her song.

The boards bob up and down held by the strength of her magic. The wheel the lightbulb the hydrobike, tied to the end post like a dog just waiting for its owner to run free.

Timid to put my toes in listening to all the stories about Snappy, I am unable to resist falling victim to the powerful spells. Despite the warm breeze, her body stays just cool enough,

an excellent shower replacement and perfect after many games at camp.

Sitting there quiet and dazed

I listen,

only to hear the call—carried through the foothills of the White Mountains, weaving through an army of birch trees, bouncing from island to island, and skimming across her glassy water— making its way to my ear.

A call, a trance, a reminder that I am at peace, at home.

Phineas Schanbacher‘25

Aquiline beauty, big eyes hang, dragging a white space between the iris and the long black bottom lashes. Patchy stubble covers a small plain, weeds growing. On the top side of the eye are thick brushstrokes, dark. Dark hair, black, brown, curled, waved.

Waved and said hi, not a smile but acknowledgment passed between us. Passed nonetheless. Passed and ended before it began.

Two swimming pools separated by a high ridge, a pointed, beautiful arch. I go there when I need someone to think about. When I cannot surpass passing because, in this imaginary place, he can swim with me.

Francis Beam‘25

I am old enough to have Little Wisdom.

The kind that comes from the extrapolation of experience.

The kind that shows me the world through a small keyhole, with kaleidoscope vision.

The kind that gives meaning to beauty.

The kind that shows me the world both as it is and as it should be.

The kind that isn’t quite right but is never truly wrong.

The kind that lets me stand on the blurred lines without falling in.

The kind that gives me adaptability with commitment.

The kind that knows it isn’t good but isn’t bad either.

I have Little Wisdom because I am young.

Daniel Koldobskiy‘24

1348,

Paris, The Black Death.

The city sticks out of the ground like a cut, a splinter. A little piece of wood that got into the skin, that hurts and throbs. That sobs. You can hear the crying all over, as normal as the chirping of birds or the passing of time.

As the clock strikes noon the bells ring out. The doctor stops to count: one, two, three. He doesn’t wait till twelve, turns away and heads home. The light dances on the river’s surface, smooth and silky, gliding past the algae and muck. The doctor walks across the bridge silently, one hand in his pocket.

When he opens the door, he is greeted by chatter. He sits down at the table and begins to talk. The day was the same as always: the sickness is spreading. It can’t be helped. He does what he can. The way his bird mask sits at the doorway almost makes him laugh. Like a scarecrow, he thinks, but for people.

When they first heard about the child, the townspeople thought it was a joke. The stories poured in. In Chantilly he had lifted himself up into the air, flying higher and higher until his audience was convinced. Then, he let himself fall back to the ground, and, when the dust cleared, his hair was not the least bit ruffled. In Lille, a woman had come up to him, crying. Her daughter was missing. The boy turned away, clapped his hands twice, and smiled. Nothing happened. Then, as the woman was about to leave, he clapped his hands a third time, and the daughter appeared.

The doctor paid no mind to those stories. A boy who could lift himself into the air, make people appear just by clapping. Next he would hear the child had reattached a severed arm, fixed someone’s paralysis, awakened a dead man from his sleep.

One story about the child was widely spread. In a nearby town, the boy had appeared. He was ridiculed for his robe and his cane, for the way he shuffled forwards rather than walked. He looked like an old man, except for his eyes. They said his eyes glimmered like they were on fire, that they jumped from person to person with an animal-like focus.

They said he stumbled and fell, that his cane broke into a hundred pieces. They said he didn’t do anything, just waited there, smiling, until someone passing by asked if he needed help. The smile disappeared and he said no, got up, and kept on walking.

They said he found himself an elevated spot, stood stiff and tall, and began to chant. He chanted for hours on end, unintelligible, until a crowd had gathered out of curiosity and fear. People watched from windows and listened through closed doors. Suddenly, the boy stopped, and the silence that followed was like a breath of fresh air. He shook off his robe and pulled out a bag that shook and trembled in his hand. He opened it, and pulled out a pitch-black snake. The snake curled itself around his clasped-together hands.

Suddenly, the boy separated his wrists, and the snake broke in two. A gasp echoed its way through the crowd, followed by the child’ s laughter.“Things must be broken before they can be fixed,”he said, and he clapped his hands together three times. The halves of the snake came back together, and it was no longer black, but a radiant green and blue. The boy put the snake back in its bag and walked away.

The stories spread in their usual way. The doctor chose to ignore them. He traveled from house to house in his bird mask and overcoat, moving quickly, efficiently. He knew he didn’t have a solution, but continued on regardless. People need some kind of answer. Had he stopped, it would have been worse for him and them.

He recommended letting blood. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not. At one household, he prescribed a medicine to cause vomiting. The problem was in the fluids, deep within the blood; to make it go, the fluids had to go too.

One woman called his bluff, accused him of lying, said he didn’t know any more than the rest of them. He moved on to the next patient, made no response. What could he have said?

When the doctor’s own daughter grew sick, it came as a surprise. They had taken every precaution. He had worn the suit, prayed every evening. His wife cooked with medicinal herbs; they never traveled out of town. The doctor’s wife was so shocked it seemed she might take ill herself. The doctor himself began wearing his coat and mask at home.

It started with fever, then got worse. The blisters began to appear. The doctor knew from experience how much time she had, and as a result grew more desperate. He tried everything. Let out her blood, gave her molasses, applied pastes to her skin.

He prayed longer and harder, as did his wife. They had no other children. Around this time, the doctor began to listen more closely to the stories being told. A girl he was treating told him she wasn’t going to be here tomorrow, she was going out to find that boy. They said he knew how to cure it, that just one look from his eyes was enough. That if you believed you would find him, you would.

They said a few days before, the boy had been spotted next to the Seine. His robe had gotten larger, more ornate. He was carrying bread and wine, walking alone. A sick man approached him, begged for help. The boy did not turn his eyes away from the water, just motioned for the man to follow him. As he walked, more of the sick joined, creating a procession of men and women, children and adults. Suddenly, the boy shook off his robe, falling back into the crowd.

They said that suddenly the boy’s eyes looked older, and sad. That they lost their brightness and luster, their energy. That for a moment the boy could have blended in with them.“I am no better than you,”he said, and picked up his robe, which had been trampled on by the crowd. The robe was in tatters, and the crowd waited anxiously for his reaction. It had been beautiful, soft, covered with intricate patterns and symbols. The boy’s eyes regained their brightness, and their focus. He paused for a few moments, then threw the cloak into the river, grinning. “Something must be lost for something to be gained,”he said.“Trust not the doctors with their platitudes, the kings and queens with their greed. Follow not those who have led you here. To be healed you must let go of the things which have held you back. To be healed you must break free.”

And suddenly the cloak jumped back out of the water, no longer in tatters and somehow more beautiful than before. And they said all the sickly men and women in the crowd that day were cured.

On the second day of his daughter’s illness, the doctor made his rounds. The woman who the other day had questioned him sat there with a smirk, telling him she was going to find the boy and his magic. That he could try what he wanted, but she knew how to be healed.

He heard the same thing from others, but there was one problem: people disagreed over where the boy was. Some said he was in Giverny, others in Chartres. An old man had seen him by the Seine earlier that day, said the boy had told him to come there again tomorrow.

That night the people set out, to Giverny, to Chartres, to the Seine. Along with them went the doctor and his daughter. He had nothing to

lose by going, he thought to himself. He and his daughter walked separately from the others, on their way to the river. Meanwhile, other groups went to Giverny and Chartres, and still others to other spots, all in the hopes of seeing the same person.

The doctor did the math: the boy could only be in one place at a time. Or maybe not? It was hard to say. He wasn’ t an expert in magicians. At the Seine they waited all through the night and morning, wondering when he would show up. But he didn’ t show up at the Seine. Nor at Giverny, nor Chartres.

Now, a new rumor sprung up: the boy would appear only to those who truly believed.

That night the boy appeared in the doctor’ s dreams.“Why are you crying?”the boy asked. The doctor didn’ t respond; they both knew.“Why are you crying?”the boy repeated, and the doctor was filled with a sudden anger.“Because of you.”And the boy started laughing, and his robe began to shake in the wind.

“I haven’ t done a thing,”the boy said.“How could you be mad at me?”

Then the boy looked the doctor in the eyes, with a deep and unyielding focus.“I only exist because of you.”

And the doctor remembered the woman talking to him. You don’ t know any more than the rest of us. He remembered letting out blood without any results, the patient dying the next day. He remembered the scarecrow mask, how instead of scaring off birds he scared off humans, letting them know this house was yet another sick one.

And he got on his knees and begged the child to cure his daughter. And the boy smiled and walked away, and the doctor continued to cry.

The next day the doctor’s daughter died. As he made his rounds that day, he felt guilty, ashamed. If the townspeople had been able to see through his mask, they would have known. But all they saw was that same old beak, heading from house to house.

The townspeople continued to search. They said the boy was in Provins, in Lille. They looked all over, and the child was no closer to being found. And yet, the stories continued to spread. And the doctor continued to make his rounds.

And the people continued believing the boy would come.

Ethan Yan‘24

There was one ponderosa pine growing

On the leeward side of the mountain—

This was the only one singing its tune.

The mountain winds whirled with vital Force: an arrest of sense or idea. It seemed to be the same force that bore life

To the endless crashing of waves on rock, Which is of canyons and depths, Of the devotion from the distant moon.

The growing pine had witnessed

All births—dustbound heat, changing Friends, barren straits—

Recalling that the wind gave at birth under the difference that dawn Had presented on those days.

The wind, the tide, the moon, the dawn: Although these may appear always, They are merely felled shadows—

Only one singing its tune is there Still, bound only to the leeward side, Sending itself away, one last time, In pining.

Neel Behari‘25

Calm blue of the pool’s thin tarp

From the villa’s tranquil deck,

Shielded from the streets’noise and grime

The vibrant green guises

A fictitious lush paradise

Same blue hue graces the tarp across Stitching roof, threads of wishes, Holding together shattered walls

Bearing lofty weight of home and hearth

Swirling in air like bitter truths

Clear blue of plastics across

Pools of trash cover dusty roads

When mere meters away, skin is soaked,

Chlorine waters, splendor, delight,

Oblivious of the other side

Dust and sand shatter the mirage

Gazing upon the scorching land

Where unyielding sun kisses the skin,

Of those toiling in the burnt desert

Their brows furrowed and hands calloused.

Timothy Edwards‘25

*After the painting“Room in New York”by Edward Hopper

Seated in his favorite armchair, his back hunched and his newspaper scrunched in anxious hands, my father let out a heavy sigh. His furrowed brow and trembling fingers revealed the torment of a worried mind. The headlines spoke of the war, of battles fought in faraway lands, and of young lives sacrificed under the guise of duty and pride. Dad’s logical mind, an engineer’s mind, sought answers in the dramatic words on the paper. He was waiting. And he was hoping—no—dreading the news of my so perfect older brother, Michael, who had enlisted. He went against my parents’will, yet in some stupid, altruistic way, they found it all exciting. That is, until they learned he was now on the front lines fighting. The sharp blast of honking city cabs jolted me from my daze, a cacophony of sound reviving my attention.

Across from the table, at the upright piano that dominated the quaint room, sat my mother. Her long fingers dragged across the keys with an almost aggressive force, her usually graceful movements now more akin to a tempest. The piano’s melancholic tune filled the room, a haunting echo of the turmoil within her heart. Tchaikovsky, that’s what it was: his sixth symphony. At times, she would turn to the rest of the room. Her eyes were red and swollen, and her music seemed like a desperate cry, as if trying to cast away the nightmares that had taken root in her mind. I’m not sure. She clearly found relief in the minor chords, pouring her preemptive grief into each note. And then there was me. In the corner of the room, I worked on my schoolwork, away from my parents’dreadful aura.

I am almost fourteen now, but everyone thinks I’m too young to fully understand the weight of the outside world. My parents think I’m too young for just about everything. They

don’t tell me about the news, but I’m not stupid. I figure things out pretty easily. That doesn’t matter to me though. Michael was never“too young”. At my age, he discussed politics and got respect from the old man. And mother showered him with love every day. Look at me. All I get is the silent treatment.

As my father reads on, my mother’s fingers continue dancing on the piano keys, combating her private agonies. In this little New York City room, the thoughts of my idiot older brother create an invisible barrier that separates us. He just always has to ruin everything. I hate him. I hate him so much. It’s about time I free myself from this moment of exile. I open my mouth to speak. It seems like the whole world halts. And in some ways, it does. My mother stops playing and turns away, leaving just one finger on the warmed keys. The silence is refreshing. But neither of them can look my way. Father pretends to ignore me, looking as invested as ever in his world of black ink on loose sheets. And my mother simply stares at her pale complexion reflected on the lid of the dreadful instrument.

Yet all I asked was,“Are either of you going to ask about my day?”

Dylan Moyar‘26

Wednesday, 15

I arrived in Paris two days ago. The legend of the broad streets’wide magic, of the enticing romance of young men and women waiting at open air café tables, of the lovely night lamplight chatter is real. I dropped off the bags in the hotel and escaped outside, nothing on me, no destination in mind. I watched, listened, and marveled. The trees came into sharper focus and the smiles on the faces of passing pedestrians took on new meanings... The days are fantastically adventurous; the nights, loftily romantic. I go out in the morning for indefinite strolls down flowing streets and pick up maps at intersections. Yesterday a flower shop caught my eye. After three hours of blissful wandering, taking in the sweet blend of guitars and jazz violins, I found my way back there today. The sunlight faded into lamplight before I returned to the hotel. I went to a bar. There were a couple of personable university students who spoke English, but speaking with the French girl, whose bilinguality was comparatively subtle, was the peak of the night. Her voice and cheeks glowed with the fashionable oldtime romance of her city. When I left and beheld the sky, I thought I could see the stars.

Stars floating over the city smog! The beauty is so appeasing, to have appeared in nature’ s divine form over the haze of modern buildings. Only in Paris can the line between romance and truth be so subtly delineated. I find I’m not quite sure of anything except my current happiness.

I love being alone. For this week, I’m free to be no person. I don’ t have to define myself, learn names, give mine, show up, eat lunch, or respond to others. It’ s a free life, free of acquaintances, needs, and prerequisites. In five days it’ ll be over, and I’ ll fly back; Dad will pick me up from the airport, and it’ ll be back to whatever my life was before this; but I can’ t say I’m worrying about it. In this charming city of spontaneity and love, everything else is so far away.

Friday, 17

I visited an art museum this afternoon. I don’ t know why; every time Mom has attempted to interest me in art museum visits, I offer up at least brief resistance. But while staring at a naked marble statue in the middle of a cobblestone square, the idea struck me, and it seemed brilliant. My thought process was, why not?

I asked the waiter at the rose restaurant where the nearest museum was. He nearly died laughing when I told him how the pedantic university student he saw me with yesterday had cited a slovenly pas cher kitchen as his preferred restaurant. Yesterday, the waiter had told me to ask, wanting to know whether the student was legitimately knowledgeable or not. Today, the waiter decidedly thought the guy had mispronounced the bourgeois, unaffordable rococo complex by the palace, and that his poor French had failed him. While the waiter laughed, I took his tray with drinks so that they wouldn’ t spill, chuckling along politely, knowing that it had been my poor French to twist the name. He gave me directions to“the greatest museum around.”

The museum was alright. After a while, the walls started closing in.

Sunday, 19

I brought a bouquet of red roses to the girl at the bar. I’m in love with her. I’m not going home tomorrow. We’re going to run away together from the people. When she looks at me and smiles, my heart melts in silent flurries and my dreams spill out of my mouth and they all sound as real as the surreal sparkling counter we’re seated at and the children playing darts in the far corner of the room. Her face is beautifully sculpted, her smile devoid of any inhibition. She has a photo in her back pocket of herself as a little girl hugging her two best friends. That was before her life came uprooted and she had to go live with her grandfather, who died and left her a fortune. She talks about the ocean, the waves and their oscillating lines on the sand. She loves great music that captures the old Paris. She took me there, and we danced across a stage in front of faceless, cheering strangers. By then the dream had taken hold of me and driven out desire for anything else, leaving me satisfied with and convinced of the new reality I had entered into. I’m sorry. I’m sorry, my words are all windy and rainy now, because I’m beautifully torn in a spring storm. Peace and love haven’ t mixed

nor settled yet this new year. My heart is on fire. I can feel it literally simmering. Uncoiling beneath my ribs. I will not sleep tonight, but gather the few things I’ ll bring with me tomorrow. Money, the Christmas photo, my suitcase with clothes. I don’ t want to return, ever. There’ s something especially wonderful about Paris in the rain.

Wednesday, 21

The golden unwinding fields of grain leading away from the city generate a new physical feeling within my chest. I’m on a train, speeding across the countryside. The city is long behind me. Maybe I’ ll never see it again. Maybe I’ ll long for it, but with a horizon shining all colors but gray ahead of me, I know I’m on the road of happiness. The city hues and dirtied beauties can’ t work more than a small bit of their magic from a distance, while the pastures call me irresistibly. Nature’ s promise is so much stronger than people’s. How will I live? Somehow, some way. Where will I be? Somewhere, some place, where I am beyond any definition of feeling. I have only my feelings to describe to myself, I have only to live for myself, I have only to experience bliss and harmony alone. Free is what I am. And this will last.

The wooden table top is littered with sparse flecks of glinting sun. The purple velvet of the booth is fading in the light. Ice cubes bob brilliantly in my glass. I see figures of men outside, working, hats glinting in the vernal sun. Behind them the land and sky expand eternally, to converge at a line. May I dream that once I cross that line, I’ ll be forever out of the reach of all I’ve ever known? Love is gone. Family is gone. Life as I knew it is gone. This is the best I’ve ever been.

Treat people with kindness. Entreat them to your respect. Rule yourself according to the guidebook of others’thoughts. I am done. Allow me to forget language. I am headed for the future.

Liam Digges‘27

All meet their end

What is to drown, but to rise downward up towards the end?

An intake held for all of eternity

And chained to that breath lies a darkness so bright

That everything fades away

And so wait the judges, yelling in soft-hard voices with sharpish broken corners

Fading in and out in perfect clarity

Condemned, you await

Free at last, and yet bound to an existence so dull it cuts

Like a wicked thin razor, empathy blunted

What awaits is unanswerable,

To know is to cage reality,

But reality is hard to catch, so you whisper to it,

Hiding desperation behind soft and soothing words, you slowly reach out for its sunny feathers

But reality chirps too loudly for whispers, and sings to its own tune

One of endless misery,

And so you wait

Fear is left behind, as the dreaded end hides an interminable beginning, infinitely worse

After all, nothing matters anymore, but everything does

Nothing to lose, and yet everything is at stake

Only anguish is left—never ceasing

As sharp as the mind may be, Corners will blur, fuzzing over, Closing in on places that once existed, people that once meant something

Know this: You are alone Forever.

Finn Tondro‘24

*After the book“Hypnerotomachia

I found myself on a dazzling oaken bench

For I had lost the straightforward path.

The radiant glow of all things churning

Cleared my muddled mist and opened my eyes.

A lifeless plain littered with Roman statuary,

As much an ornament of the colorless landscape

As the crimson acne on my flaccid brow, Emerged from the surrounding mire.

Racing and aroused, I chased my Polia

From dream to dream. But once more,

As I catch her vivid embrace, my idea

Festers and fades

And I am left lonesome and lost

On the old oak stump in my backyard.