glassworks Fall

featuring mysticism

pain and parenthood

strained communication

a publication of Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing

2023

Cover art: “Airhead”

by Dalanie Beach

The staff of Glassworks magazine would like to thank Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing Program and Rowan University’s Writing Arts Department

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Katie Budris

MANAGING EDITOR

Cate Romano

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Stephanie Ciecierski

Cover Design & Layout: Katie Budris

Kay Fratello

Rebecca Green

Allison Padron

Glassworks is available both digitally and in print. See our website for details: RowanGlassworks.org

Cat Reed

FICTION EDITORS

Courtney R. Hall

Glassworks accepts literary poetry, fiction, nonfiction, craft essays, art, photography, short video/film & audio. See submission guidelines: RowanGlassworks.org

Daniel Hewitt

Cat Reed

Javis Sisco

NONFICTION EDITORS

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing Graduate Program

Correspondence can be sent to: Glassworks

c/o Katie Budris

Rowan University

260 Victoria Street Glassboro, NJ 08028

E-mail: GlassworksMagazine@rowan.edu

Copyright © 2023 Glassworks

Glassworks maintains First North American Serial Rights for publication in our journal and First Electronic Rights for reproduction of works in Glassworks and/or Glassworks-affiliated materials. All other rights remain with the artist.

Ellie Cameron

Caitlin Hertzberg

Frank E. Penick, Jr.

Amanda Smera Welsh

POETRY EDITORS

Rebecca Green

Iliana Pineda

Nyds L. Rivera

Paige Stressman

MEDIA EDITORS

Lesley George

Bryce Morris

S. E. Roberts

COPY EDITORS

Editing the Literary Journal

Fall 2023 students

glassworks

Fall 2023

Issue TwenTy-seven

MASTER OF ARTS IN WRITING PROGRAM

ROWAN UNIVERSITY

Issue 27 | Table of ConTenTs

arT

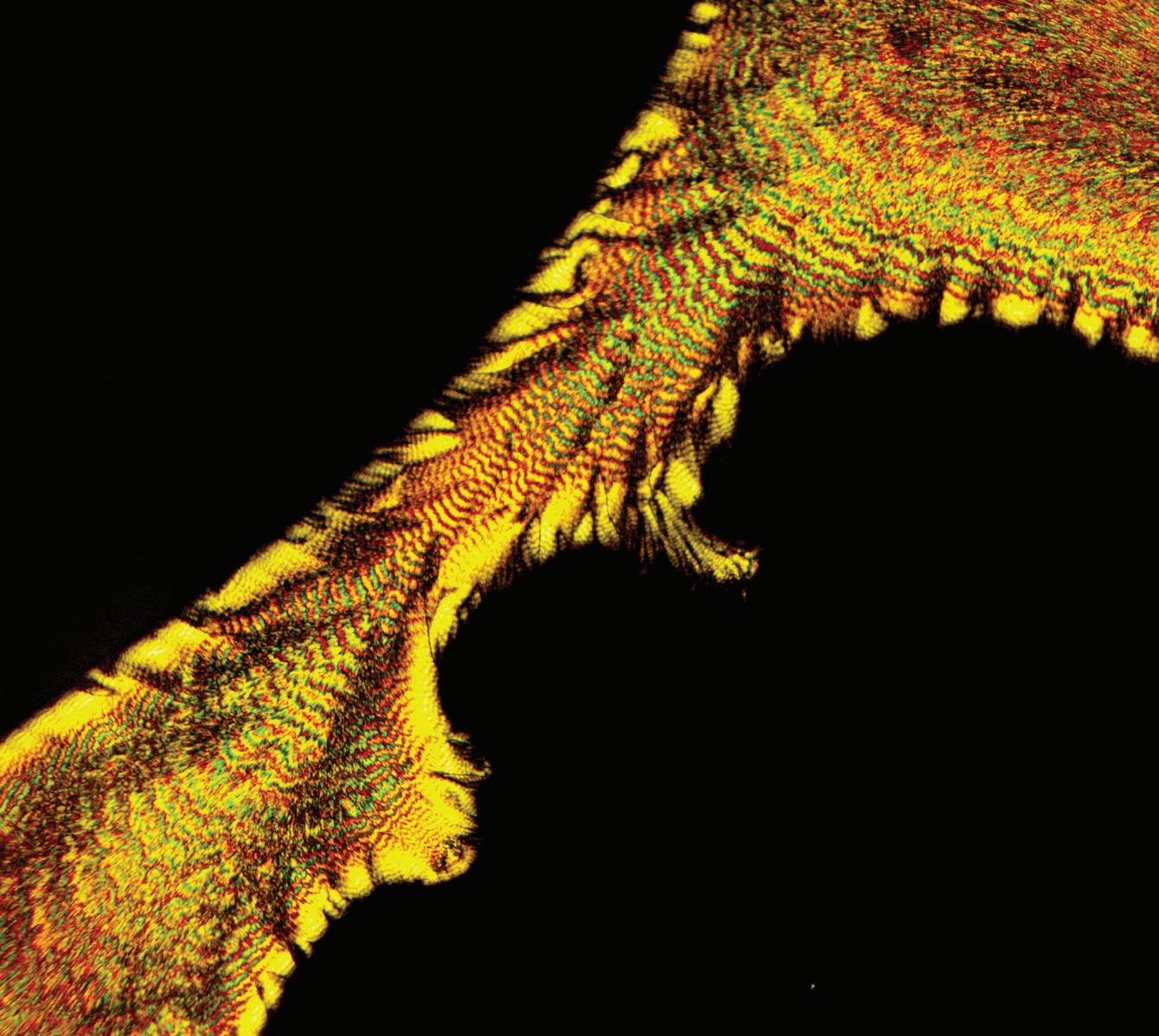

IsThmusCopIC |

ForensIC

FICTIon mIChelle

nonFICTIon audrey

alIson

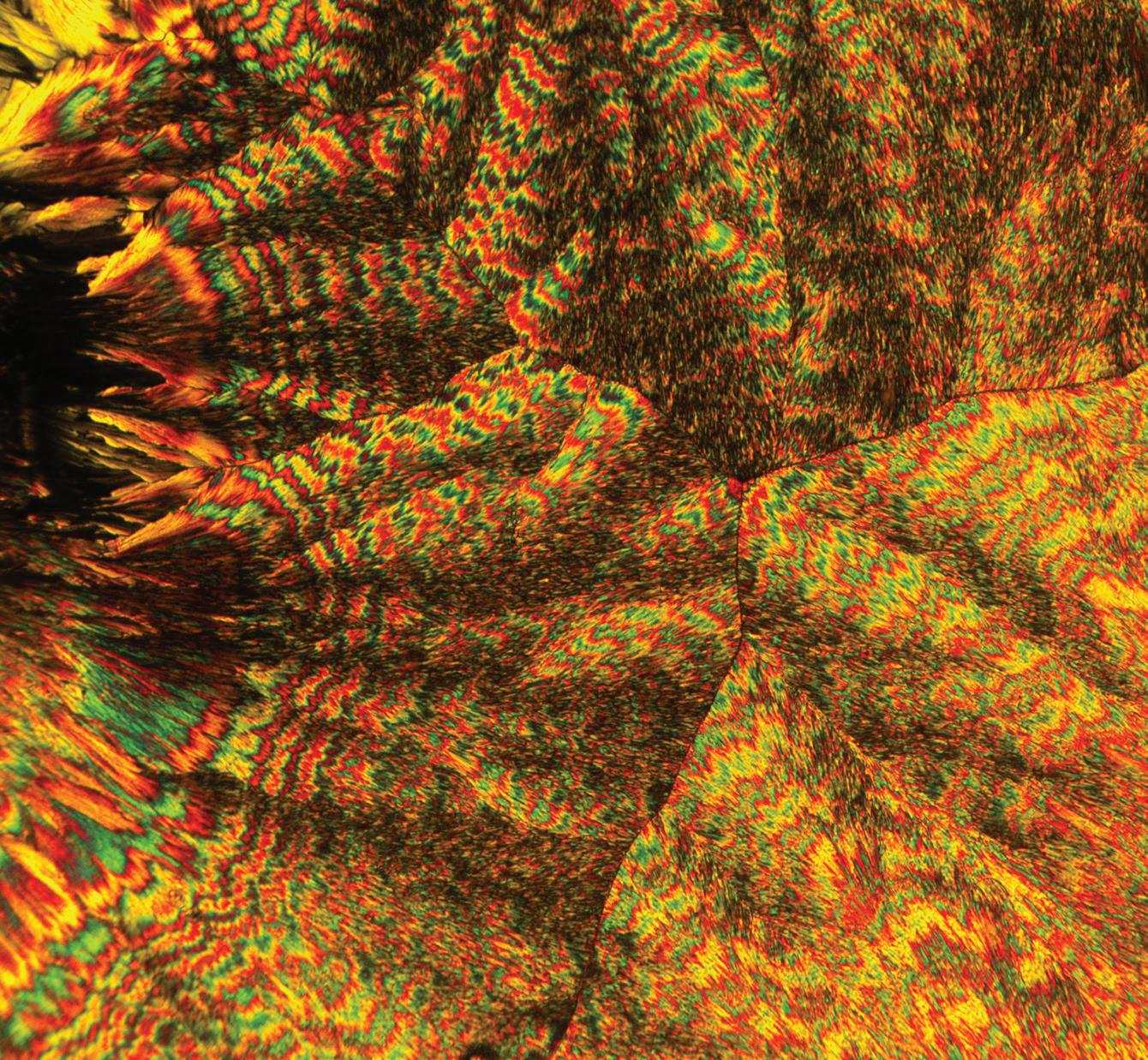

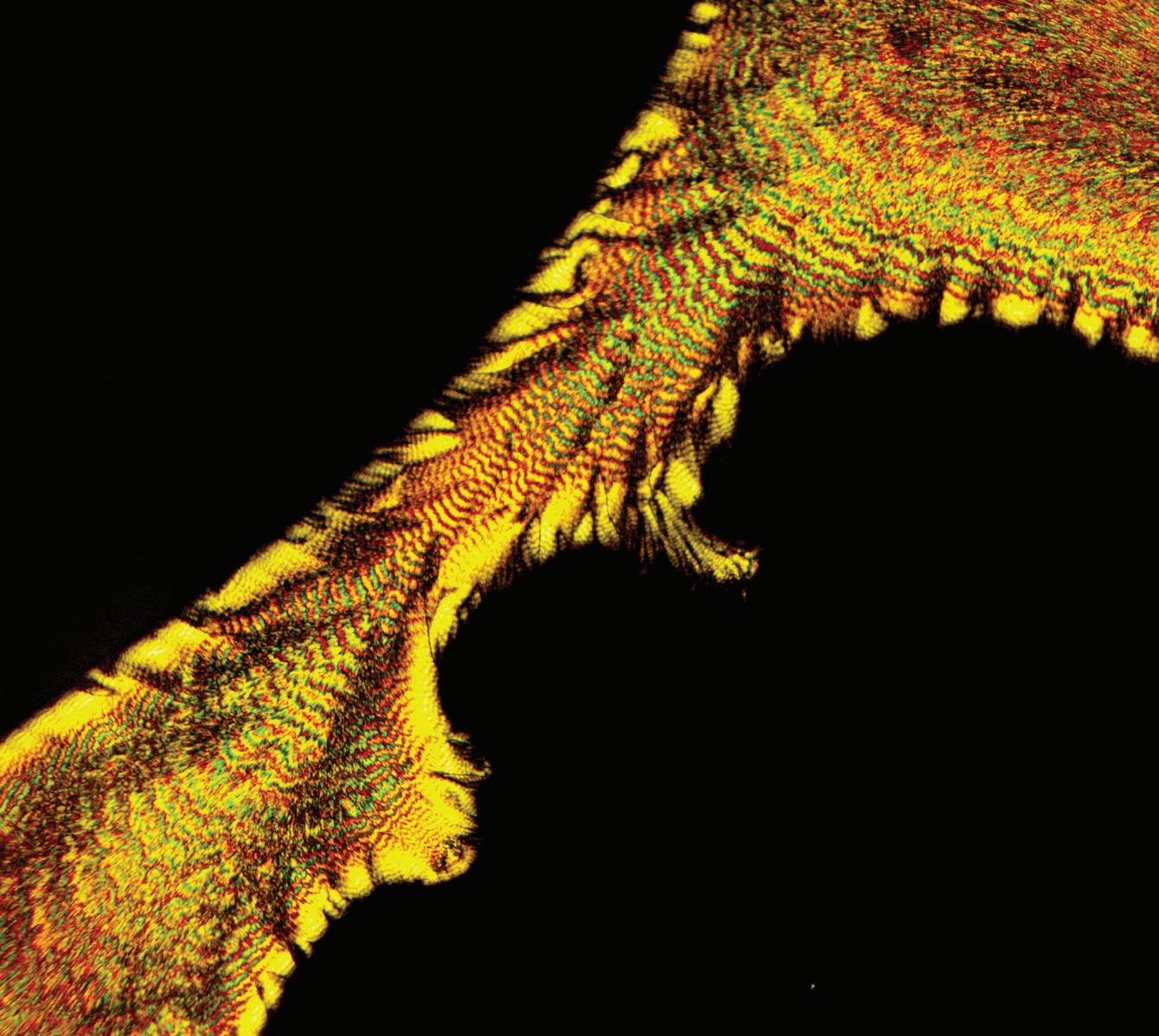

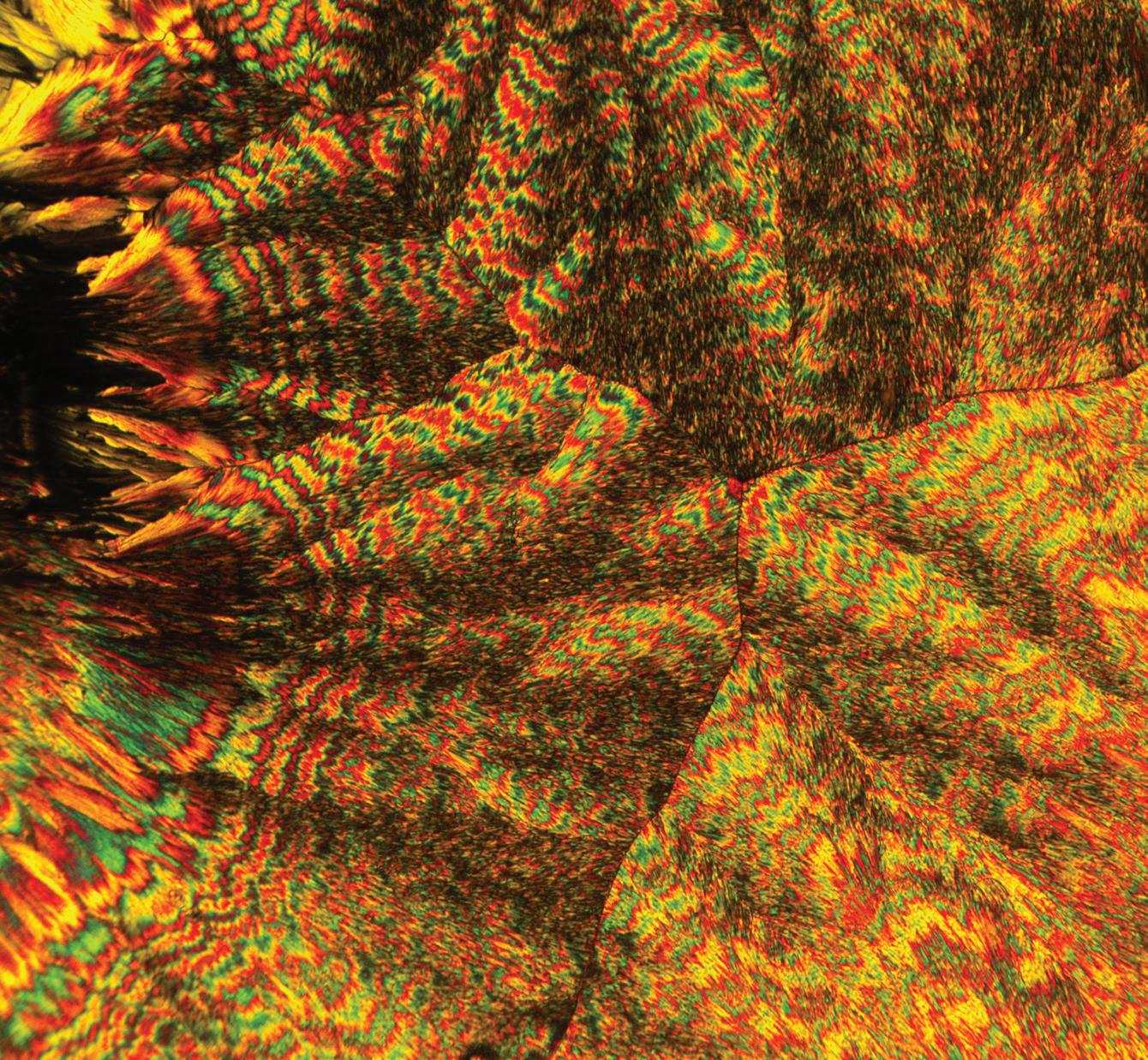

Ivan amaTo, Topography In TIny C and mICrosweeT | 67

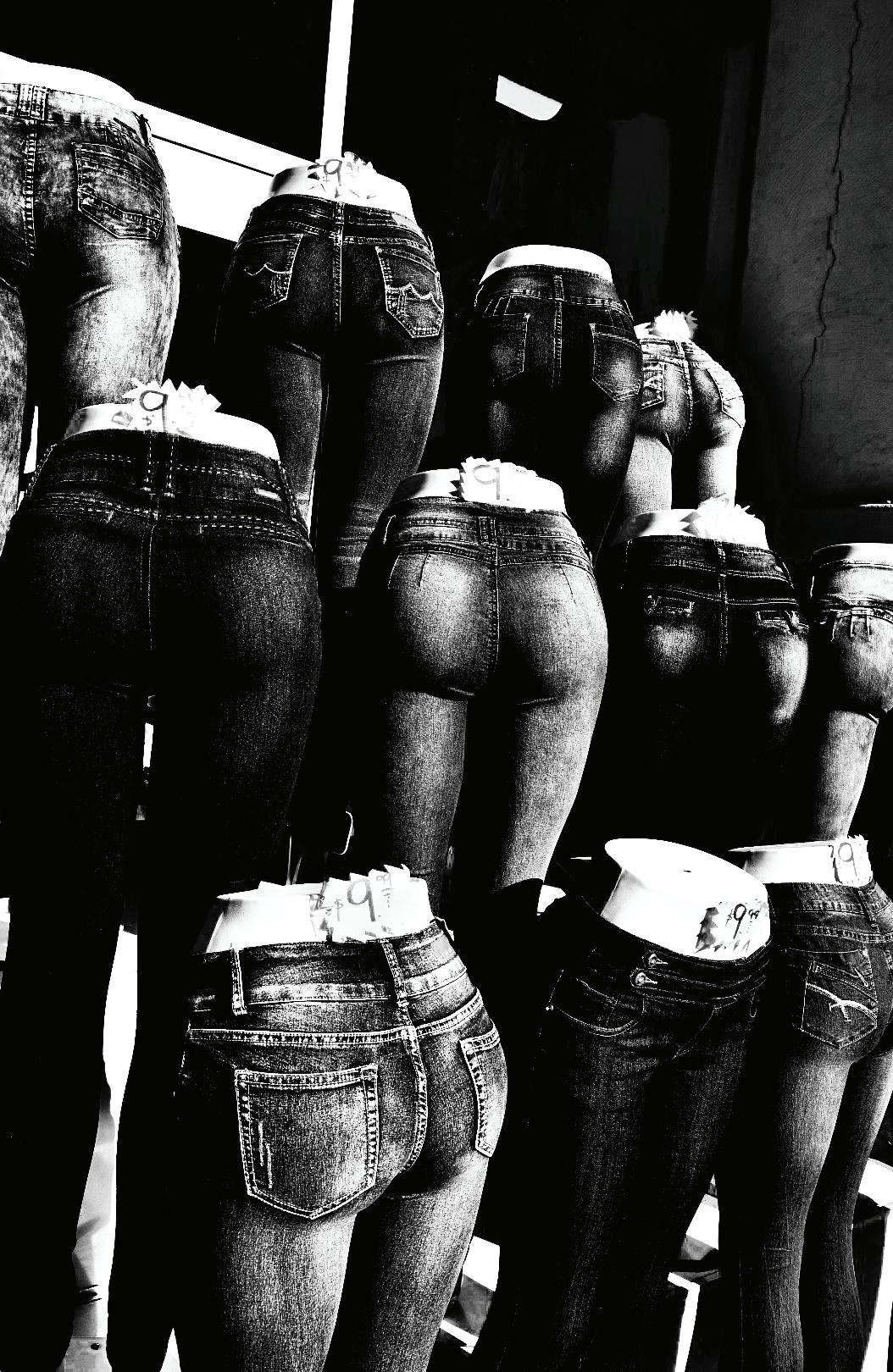

17 dalanIe BeaCh, aIrhead | Cover lover Boy | 52 wIllIam C. CrawFord, ForensIC FInds 1 | 6

FInds 2| 36 JIm ross, maCrame From The sea 30 | 48 maCrame From The sea 56 | 33

BraCken, all lITTle hands and FeeT | 8 mIllIe kensen, TIny Bones | 55

T. Carroll, The paIn sCale | 37 JennIFer lang, on Common ground | 24

maTayosIan, The soluTIons To a young woman’s proBlem | 50

poeTry alex CarrIgan, moTher and FaTher Tongue | 18 whITney Cooper, peelIng BaCk | 69 a Tender head | 68 susan g. dunCan, o, To Take whaT we love InsIde | 70 kaTee Irene FleTCher, day-To-day | 35 emIly Jahn, my aunT’s loCkeT | 45 nepTune’s Candle | 46 orChIds | 47 sheree la puma, BeCause I’m lonely . . . | 34 laura CelIse lIppman, on The 18Th annIversary . . . | 7 laura mCCullough, daddy, you do noT do | 16 ThIs Is how my FaTher has TwICe Been Taken In . . . | 14 kevIn neal, The monsTer we made | 54 monICa prInCe, hurrICane season | 4 shana ross, ThIs way Comes | 3 damIeka Thomas, CoyoTe CreaTes The oCean | 20 red woman | 22 ellen June wrIghT, selF-porTraIT as a gray novemBer mornIng | 53

The hIsTory of Glassworks

The tradition of glassworking and the history of Rowan University are deeply intertwined. South Jersey was a natural location for glass production—the sandy soil provided the perfect medium, while plentiful oak trees fueled the fires. Glassboro, home of Rowan University, was founded as “Glass Works in the Woods” in 1779. The primacy of artistry, a deep pride in individual craftsmanship, and the willingness to explore and test conventional boundaries to create exciting new work is part of the continuing spirit inspiring Glassworks magazine.

glassworks 2

ThIs way Comes

Shana Ross

I know you, and you will want to say that sunset was predictable because accurate timekeeping feels like control, or close enough to soothe the inner scream we have agreed to call tinnitus. I am more right, which brings me no joy, when I say yes, yes, the reliable

spinning of planets and stars can balance on seconds, and still the sun fades the way it wants, the clouds shading in moods, every night with no consultation to the clockwork of the universe, no vote put to humanity. We both could have known we’d be here,

by now, sitting in the dark an hour past twilight. It’s only the transitions where we litigate the details. It seems clear now we are neither of us luminescent. No inner glow. We make do with what we have, well suited to our cat eyes, the way we share every scrap of light, the reflections

we offer in diminishing and recursive bounce, my hand reaching for yours. Someone in the distance is worried about the way home, and on seeing our paired and blinking stares, whispers wards against the watchfulness of wolves and witches, breaking into a run.

glassworks 3

hurrICane season

Monica Prince

after Rachel McKibbens

It’s in the small moments— a stray rain drop on the edge of an afro puff, a line of blood marking a scar reopened, not fatal, a quiet river marching toward Hell—

in which you remember love like a monsoon, like a forecast calling for devastation. You have been warned every day since the light broke you open, and to no one’s surprise,

you did not evacuate, did not board up your windows or even fill the closets with water and tuna. You always stay, convinced you know better than God,

than the rupturing seams of clouds and slick backhands of lovers. The first time is never the last time, foolish heart of spider wire, misplaced trust and golden naivety.

Name every storm after the officer who takes down your statement but never files charges. Tattoo each moniker on the remodeled bone once the beating sheets lighten

4

glassworks

against the side of the house you call body. One morning, you will say enough, ripen like overstuffed grape, poison the smiles of any possible love, call it protection.

One day, you will trade this recurring season in a country you believed was your inheritance for a new planet, cleansed not by rain but fire, still burning, the smoke a song in your lungs.

glassworks 5

forensIC fInds 1

glassworks 6

William C. Crawford

on The 18Th annIversary of my moTher’s deaTh

Laura Celise Lippman

The sharp tack of autumn had not pierced the air that year she died, as it does here, each year, where I live. Somehow last week that date went unheeded, overwhelmed by lassitude or busyness or random family worries, a week of helping with the chaotic lives

of grands and kids dithering about the future amid the confusion of daycare, school starts, marriages stressed by current conflagrations— work, substance abuse, fractures, dislocations, low back pain, and imminent declinations of age.

Under the distracted brilliance of fall’s blue dome the onrushing Armageddon of heat, smoke unnerving politics, inconsistency and overpopulation

I center myself with cerulean skies, lingering smell of blooming roses, dahlias unfurling curly petals along our waysides

the sun still radiant before the start of our late-season rain.

glassworks 7

all lITTle hands and feeT

Michelle Bracken

It’s been thirty-one days since my father killed me with a bullet to my chest. I know this because it’s been thirty-one days that my little brother Stevie has been in a coma, a bullet in his brain. The nurses on his floor keep track with a calendar tacked to the wall. Stevie would have liked a calendar about dinosaurs, sharks, or even one with pictures of outer space, but one of his nurses brought what she had at home: a calendar of English gardens. It’s the only color on the walls.

The lights are out when I visit Stevie at St. Bernardine’s. The hospital glows in the darkness of night, covered in a green fog. I used to watch him from the ceiling, but I wanted to be closer, to see him breathe, to see the stitches in his head, the heartbeat beep on the machine near his bed. So, I pushed myself further, as if I was a kitten resting on his chest. Lighter than a feather, lighter than air.

Remember the time we danced in our mother’s heels? Tap tap tapping down the hall, her necklaces slapping against your baby belly, giggling as we danced?

For whatever reason, he never answers back.

The people on the streets and the nurses in the hall are never this quiet. Always full of something, but Stevie lies here, wrapped in white, a tube in

his mouth, his dark hair a bunch of fuzz. My mother visits in the day, her arm in a sling, and sits in the corner of the room, looking out the window. She never opens it. Just stares out and sips from the paper cup in her hand.

Her face so still, her eyes empty. She thinks a lot about her boyfriend Maurice: his smile, the white of his teeth, and how he would hold her when she cried. My father shot him, too.

But mostly, she thinks about me. Josephine, oh Josephine. Now what? My mother tries to block her last memory of me and my father, the gun in his hand. ~

It was night when we moved into the Sunset Row complex. My mother carried our things in black garbage bags, and I held Stevie on my hip, his head resting on my shoulder. His hair was full then and sometimes it’d cover his eyes and he liked it that way, said it was like another world under all that hair.

“Stay close,” my mother said, dragging the bags up the stairs to the second floor. She kept her head down as the men below yelled out.

My mother was used to men yell-

ing. Before the Row it was from my father, but there were times when she would tell me about the days

glassworks 8

before him, when all kinds of men paid her all kinds of attention.

“Don’t look at them,” she said, taking the key from the pocket of her jeans.

The doorknob was stiff, and my mother pushed her body against it. “Just for a little while.” She quickly locked the door behind us and sat on the carpet, her back against the wall, her eyes closed.

“What about Daddy?” Stevie asked, rubbing his eyes. He walked around, counting aloud how many steps it took to get from one wall to the other. Even though he hadn’t been in school, he could count to 100 and took every chance to show it.

“It’s better this way,” she said.

I took Stevie by the hand, and he continued to count. I had been teaching him his numbers and letters, getting him ready for kindergarten. In our last place, I even had a chart of the alphabet stuck to the fridge, something I had drawn while waiting up for our father, giant red and black letters with a picture for each sound. Alligators and bears, lollipops and jump ropes.

When our mother was at work at the market, we’d sit in the kitchen on little plastic chairs, my knees knocking together, and he clapped every time he made the right sound.

At Sunset Row our room was the only room. It had a closet and a balcony. We wouldn’t have furniture and would use blankets for beds.

Just for a little while. I could hear my mother digging in the living room. She liked to sort the things she packed, but it wasn’t much this time: a few pairs of jeans, some sweaters, a hairbrush.

I untied our bag and took out one of the only things I had grabbed from the old place, a thick blanket from my grandmother, someone I never met but had always heard stories about.

“When you were born,” my mother used to say, “Grandma bought this, said it would keep us warmer than any other.”

It was no longer bright blue, but so big that it could cover me and Stevie together. Faded in many spots, sometimes I’d find a piece of cotton poking through the layers. I spread it out and Stevie hopped into the middle. He fell back asleep, curled up like a caterpillar.

The blinds were pulled back and the light from the moon lit up our room. I knew that my mother would not allow us on the balcony, especially Stevie. If she had known about it, we may not have moved in, but we had nowhere else to go. Your father isn’t well, she told me, bundling us up in the car. Outside, some of the streetlights were a deep yellow and hit the sidewalks like little suns. Others cast shadows along the street. I stepped out and rested my arms on the railing, the paint chipped underneath and heard someone humming.

I leaned over and took a peek.

glassworks 9

There was Isis, my future bff, sitting on a pillow, writing in a journal. Her hair in braids, clipped at the ends with bright pink and yellow barrettes. She wasn’t humming but whispering.

“Hey!” I whispered.

“Don’t ‘hey’ me,” she called back and kept writing.

“Up here. I just moved in.”

She looked up at me and tilted her head. “Oh. Me too.”

“I’m Josephine.”

“You going to school tomorrow?” she asked, her arms crossed.

“Probably.”

She held her journal in the air. “In this little thing, I have all kinds of ideas.”

“Like what?”

Isis shook her head. “A girl has her secrets,” she smiled. “Meet me at recess tomorrow.”

My mother came out on the balcony and leaned beside me.

“Who are you talking to?” she asked, lighting up a cigarette.

“Me!” Isis shouted back. She took off and ran inside, her journal in her hands.

“What was that?”

“Just a girl.”

My mother looked out at the men in the street and sighed. “Don’t make too many friends around here.”

It got colder then and my arms shivered. The smoke from my mother’s cigarette swirled up into the night, like the little snake I had drawn for the letter S. The men in

the street threw a bottle against the sidewalk and when it cracked into a million pieces, they high-fived one another and laughed. ~

When Isis walks to school the sun is not yet out and the fog spreads over the block like a slow burn. She walks alone, navigating around shopping carts and people in dirty sweaters.

Men and women in torn jeans. They lie on the sidewalk and sometimes Isis steps off into the street just to pass them. She holds her arms tighter around her body, her backpack slung over her shoulder, her hair no longer in braids, but curled into little spirals. It makes her look older and even though her mother spent all Sunday on her hair, the curling iron hot against her scalp, sometimes burning the back of her neck, Isis hates it. Her mother said it was for church, even though they hadn’t been in weeks, not since I died.

The Isis I knew always had braids. She liked to match her barrettes to her outfits, and had a little section on the floor of her closet where she kept sandwich bags of hair clips, organized by color. Pink was the one she wore most, a color she would never not have. Sometimes socks, a sweater, skinny jeans or sneakers, but never pink on pink on pink.

This morning Isis wears a dark sweater and jeans, her white socks lined around the ankles in neon pink, glassworks 10

like frosting on a cupcake. They’re the brightest thing on the street and as she gets closer to campus all I can see are her thin ankles twinkling in the distance.

Your hair looks cute like that.

I’ve been practicing sending her messages, little thoughts. A question, a raised eyebrow.

Sometimes even a hug. These are things I try as I watch her in the mornings. She’s so busy then, getting ready. I try my hardest at night as she reads in bed, her eyes not really

He rubs his hands together and points at me.

“Take a look at that,” he says. His friend follows his finger, shaking in the cold air.

“Looks like Christmas, don’t it?”

Most of the time I don’t even realize that I am no longer myself. It’s a moment like this, when someone sees me glowing above that sets me straight. A whir in their ears, a light in their eyes. “Don’t see nothing,” his friend

The smoke from my mother’s cigarette swirled up into the night, like the little snake I had drawn for the letter S. The men in the street threw a bottle against the sidewalk and when it cracked into a million pieces, they high-fived one another and laughed.

reading, but scanning. I throw these thoughts out like sticks, and though I know they go nowhere, it makes me feel better, like we’re not so far away.

Turn around. See if you can see me like I can see you.

She doesn’t. She never does.

The people with the shopping carts start talking to one another and pack their blankets into bundles. An older man pulls his beanie down, covering his ears. He rubs his hands together. Friction, our teacher Ms. Rivers taught us.

says, shaking his head and lying back against the concrete. He pulls his jacket over his head and curls up tight.

Don’t see nothing. ~

At home, my mother covers the mirrors. She tapes newspaper sheets over the glass. She thinks it will help her get better, that not seeing herself will make things easier. That not seeing her eyes will help her forget. So strong, Maurice used to tell her, looking into them.

glassworks 11

|

“

Michelle Bracken

All Little Hands and Feet

”

She thinks that not seeing what’s missing will make her handle it all, that not seeing her cropped hair, her arm in a sling will help block her daughter dead and buried, her son in the hospital, a bullet in the brain. All of it will be on pause.

one more leads to one more leads to one more.

Do you remember the time you and your brother danced in the hallway, his pot belly hanging over his diaper? Those heels of mine tapping under your little feet, clanging together as you danced? Laughing so hard, tickling one another.

His head hit the tile, his cries so loud. The race to the hospital.

My brother, you kept shouting. Just a scratch, a nick. We came home and the two of you crawled into bed beside me, your father not there. Do you remember that?

My mother sits up and takes another drink. She looks at the blanket in the corner and drags it across the carpet. She hasn’t washed it in forever, not since I died. She wraps it around her, like Stevie did when he fell asleep that first night.

Yes, I tell her. Yes.

A thousand times, yes. ~

The covering of glass makes it easier for my mother to drink in the daylight. She only showers when she visits Stevie and when she isn’t with him she’s spread flat out on the carpet, a bottle beside her, her mother’s blanket balled up and tossed in a corner. She goes through a bottle a day, sometimes more when she can afford it. She thinks that one more drink will take her to that place, where she can close her eyes and not see me. The afternoon sun burns through the dusty blinds and

When my mother leaves the hospital, she walks across the street to the cemetery, and keeps her head down. Her blonde hair no longer past her shoulders, but cut short, shorter than it’s ever been, just past her ears. She finds it easier this way, no longer something to wash and curl, no longer something for someone to look at, for someone to touch.

When she gets to my headstone, she lies on the grass. My mother doesn’t say much. The sun hits her face. She squints and closes her eyes.

“

glassworks 12

”

She thinks that not seeing what’s missing will make her handle it all, that not seeing her cropped hair, her arm in a sling will help block her daughter dead and buried, her son in the hospital, a bullet in the brain.

In these moments, she doesn’t think of Maurice or Stevie. Not even my father.

She thinks about the day I was born, in a hospital far away, her mother not there. She thinks about the first moment she saw me, all little hands and feet. Again and again, she thinks about that.

glassworks 13

Michelle Bracken | All Little Hands and Feet

ThIs Is how my faTher has TwICe been Taken In for psyChIaTrIC assessmenT

Laura McCullough

After the second wife died, he kept posting how he wanted to die. After the third wife’s

Alzheimer’s diagnosis, he told a spam caller he wished he was dead. After that the police

showed up and wouldn’t even let him tell her he was being taken to hospital for evaluation,

the memory impaired wife coming downstairs discovered him gone. My dad looked like Santa

Claus for a long time—white ringlet cascades around his cheery face and silver white beard.

He can be jovial, too, no doubt, a belly laugher, an eye twinkle, but his hair has thinned to strands

now, spots on his translucent skin, the mottling of age, and his hands quaver. He says he doesn’t

want to die, but Everyone wishes I was dead and would just be out of the picture. I’m filling

his room with pictures—his navy days, his wives, kids, pets—he wants to brood, mull, and simmer

in the old betrayals. He says, I had a great time getting old, but now that I’m here, I hate it. He

doesn’t want to “talk to anyone” or “take any damned drugs”

but insists he will drive again, will get to that third wife

14

glassworks

in her memory care home to tell her he never left her, he just got sick, but for now, tells the spammers,

Oh yes, I have a minute. I have all the time in the world. Can you come over? I can see you now.

glassworks 15

daddy, you do noT do Laura McCullough

Not barely daring to breathe or achoo, my father felt he could face anything, embrace anyone, be friends with all, and not fearful of life’s failures, he’d get up again, and yet, something smallering began to happen as he aged. But let’s be honest: even as a girl I saw the way he framed his reality, heroism, the “underdog” always his goal, the ways to overcome, the challenge to be met; he loved a good story, was socially just, believed that right was better than might. But his shadow? Too dark to look deep into, it was there in sudden angers, and it’s come out now: staring out the window from his wheelchair, raises a fist at a walking man, snarls, If I had a gun, I’d shoot him.

glassworks 16

IsThmusCopIC

Ivan Amato

glassworks 17

moTher and faTher TonGue

Alex Carrigan

after Chim Sher Ting

When we met around the ruins of the Tower of Babel,

I didn’t know what to say to you. I didn’t know how to say to you.

I tried to move my lips in shapes that you could recognize,

stretching like a cord I used to use as a slingshot, hoping the rock I spat out of my mouth would carry the message

to you. You didn’t seem to appreciate the black eye,

nor did I come to enjoy the venom you returned when you showed me your purple tongue and your canines tinged with red.

We would have to continue and stare at one another, waiting for one of us to

move a piece across the chessboard we made from 32 rocks of differing sizes and colors.

I could try to anticipate your thoughts, your meaning, and your tone as you eyed the rocks,

glassworks

18

but I knew your language could come in feints and gambits, so I remained silent and unmoving.

Finally, I broke the silence by scrambling the chessboard until all that remained was a darker color of soil where our game used to remain.

I grabbed a branch to use as a brush on the earthen canvas, hoping you’d understand my shapes and figures. It should be easy, but I’m still not sure

what the first thing I should say to you should be. Perhaps I should give you the branch first.

Maybe this collaboration will finally move us away from the ruins

of the tower so we can instead begin to form our own private language.

glassworks 19

CoyoTe CreaTes The oCean

Damieka Thomas

I.

Light comes first, then breath, as Coyote breathes deep, filling up lungs with acrid air that he then feeds to people. When the dream dropped out of him,

Coyote planted people in the hard earth because light always comes first then air, breath, lungs, people: eyes wide and eyelashes long like spider legs, staring hard at the sky like they’ve witnessed a crime.

Coyote creates the ocean last of all, and as all great ideas come, by accident. One day, he discovers water as he is digging in his garden, and upon digging further, he burrows himself so deep in the wet sand, sensuous in its soft cradle, that he creates the ocean.

He briefly drowns himself in his own creation. He swallows salt deep in his lungs. It burns like renewal; it ignites like rebirth.

II.

When Coyote comes up for air, landing with a thump on the earth, he trips up a hill on his little stonelike feet, and he creates ocean from earth. Before his eyes it grows as he throws the biggest animal on the land and calls it whale.

He throws in a log and calls it seal then he throws in a snake and calls it eel. Of all the things he has done, this is his greatest accomplishment; this something from nothing. When he is done, he climbs to the top of a hill with muddied feet, and looks from his perch atop the land.

glassworks 20

He becomes fat with knowledge and eventually grows bored, looking for excitement.

He doesn’t have to travel far to find what he was looking for. He depletes the ocean, pushing his creations gasping back on the land from which they come. Sucking back what he wants and leaving the rest to rot

until he allows the ocean to consume all that he has created, gulping it down in one swift swallow. This is the truth and the beauty of the ocean.

It consumes, burning in its salty seafoam taste, until all else is gone.

glassworks 21

red woman

Damieka Thomas

My mother always told me that someday I would come into my power. And when you do, the world better watch out.

I was born of the sun and the sky.

I was born of the wind and the stars. Now my feet bleed with the noise that my rattles make. My mother always told me that to be a red woman is to be forgotten. But she was wrong.

I was born on a Sunday. A holy and unholy day. I was born of two religions. I am shaped by the constellations. My body is an ode to the earth. I have the gift and curse of memory. My rattle alerts everyone to my presence.

When the rattlesnake man first came to my door, Dressed in the finest jewels and green with envy, I nearly shut the door on him. But I was drawn to that rattle wrapped in the beads on his neck. It sang when he laughed, Shaking his head to the left like he was getting water out of his ear. There was a sensual quality to its melody. An aphrodisiac that I couldn’t help but swallow. Before I knew it, I was undressed and undone on top of him.

When we were done, He turned back into a snake.

Slithered up my thigh, Wrapped himself around my breast, Looked up at me with those yellow slits for eyes. This was power.

I wanted all of this and more.

22

glassworks

Who are you?

I asked, stroking his head. Everything that you’ve ever wanted, He hissed.

What do you want?

I asked.

Those yellow eyes bore into me. No one had ever asked him that.

Everything, He said.

And so I gave And I gave And I gave in.

Four little rattlesnake boys. Goodbye to my husband and child.

Goodbye to jello on Sunday after church. Goodbye to birthday gifts.

I gave And I gave And I gave in.

Late at night, When I sleep with my boys all coiled around me, I dream of my body floating In the stillness of A world shaped like a rattle.

glassworks 23

on Common Ground

Jennifer Lang

Touch is the first of the senses to develop in the human infant, and it remains perhaps the most emotionally central throughout our lives.

–Maria Konnikova, “The Power of Touch,” The New Yorker, 2015

Every morning, I debate: kiss or not kiss my still half-asleep daughter with her head bent over her cereal bowl? Sixteen and sensitive, she’s as fickle as a mood ring.

When Simone was a baby, I held her a lot. Stroked her hair. Tickled her underarms. Blew on her belly button. Gave into her tantrums. Strapped her onto my right hip like a belt. Born with extra digits, she underwent two surgeries in five years. Maybe I indulged her because she was my last, or because her older brother and sister needed me less, or because I was overcompensating for her differences.

During her toddler days in Northern California, we spent Monday mornings at the park with a playgroup. For two hours, she frolicked at my feet while my friends’ kids climbed the slides or dug in the sandbox.

“What can I do?” I asked the other mothers about my cling-on.

“Don’t worry,” one said.

“She’ll grow out of it,” said another.

Fourteen years later and on the other side of the world, I think about those playgroup mothers every time Simone dodges my attempted contact like in a game of tag.

“Why?” I plead, trying not to reveal my hurt. “All I want is a kiss.”

She shrugs and tosses out random excuses: “You have bad breath,” or “I’m hungry,” or “I’m hot” after another brutal day under the unforgiving Israeli sun.

Perhaps she has haphephobia: an extreme fear or dislike of touching or being touched? Perhaps I’m not ready for her to grow up, for me to let go? ~

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, I was fortunate to know all four grandparents and was particularly close with two of them. During our frequent visits to my mother’s parents in Los Angeles, Grandma and I snuggled on their moss green couch, watching Bewitched while I petted her cheeks, cooing “You’re so soft.” Since my father’s parents lived on the other side of the Bay Bridge, we celebrated Jewish holidays, Thanksgivings, and birthdays together. I nestled into the crook of Zayda’s elbow, begging him to scratch my back with his blunted fingernails and hear him say in his thick Russian accent, “Shayna punim”

glassworks 24

or “Shayna meidala,” Yiddish for pretty face, making me believe I was his favorite.

I was affectionate with my parents too, but as I hit adolescence, a certain inevitable distance developed between us. Three months after I’d chanted from the Torah for my bat mitzvah and was deemed an adult in the eyes of the Jewish community, our best family friends arrived to light candles, gorge on potato latkes, and exchange Hanukkah gifts.

We waltzed into the living room where my mother had propped menorahs on the fireplace mantle. Everyone slouched into the two tweed sofas. My father sank into his burnt-orange-and-white striped velour armchair.

“Come,” he said, patting a knee. A middle-aged lawyer, he looked suave with his movie-star moustache, facial hair that came and went in his thirties and forties.

I teetered: Daddy’s little girl on one side, a flat-chested thirteen-yearold on the other. I shook my head. He pouted. Did he feel spurned, or did he understand I was caught between ages and stages?

From that point on, a new norm was established, but I wasn’t sure if it was intentional on some subconscious level or typical teenage drifting and obliviousness. Close physical contact became reserved for specific occasions: before getting on a plane, after opening a gift, before leaving for college, after receiving a

degree. The question is, have either of my parents noticed? At what point had I? ~

The summer of her seventeenth birthday, Simone and I fly from Tel Aviv to Mumbai in the middle of monsoon season. On our first night, we stroll along the harbor. The violent waves of the Arabian Sea crash against the shore. Everyone carries oversized umbrellas. Packs of men walk in pairs either draping their arms around each other or holding hands, fingers interlaced, as if a couple, on a date.

I’ve traveled to this part of the world before but never noticed this comportment and wonder if their physical contact is religion related. In Hinduism, which is almost eighty percent of the population, god resides everywhere, especially in other human beings; perhaps touching brings them closer to something bigger and higher and holier than themselves.

When I try to discuss it with Simone, she gives me an I-have-noclue shrug. Still curious, I ask our guide about the men’s behavior the following day.

“They’re not gay,” he says with a chuckle. “It’s not like your country. Here men show their affection easily. Even more than women. It means they’re good friends, and they care about each other.”

His words make me wonder how people would react if same-sex glassworks 25

friends behaved like this in America or in Israel or in Europe. How ironic that the lesser developed country economically seems the more developed one socially.

From Mumbai, Simone and I head south to Goa for a two-week volunteer program. Back home, my friends asked why I signed up for this. “I see the imminent empty nest and want to spend as much time together as possible,” I said, preferring that to the truth.

The truth hurt: Simone and I don’t have as much common ground as she and the other members of our immediate family. She and my husband like to garden and bike; she and her sister concoct complicated

stay-at-home writer/yoga teacher. When she refuses my morning kisses, I want to trust her ageappropriate behavior rather than question her solitude or doubt our relationship. ~

For my first eight years on a yoga mat, I never interrogated touch. Until one snowy Sunday morning in New York, midway through a 200hour teacher training program, when Yoga Haven’s studio owner asked us to close our manuals and listen.

“Today, we’re talking about assists,” said Betsy. “How to assist. When to assist. Who to assist.” She scanned the room, eyeing our baker’s dozen one by one.

vegan dishes in the kitchen; she and her brother download silly apps and stare blank-faced at their phones.

My youngest child reminds me of my younger self: temperamental, strong-willed, stubborn. If not at school, she hunkers down in her bedroom, listening to Korean pop songs and studying. I worry she’s a recluse, a behavior she’s either inherited or learned from me, a

I thought about my first teacher on the opposite coast and how his touch had made me feel the poses more intensely and had roused my body without seeming awkward or sexual.

“It’s sensitive,” Betsy said. “Not everyone wants to be touched. Some people, especially women, have experienced trauma. You must always ask your students if it’s okay.”

“

”

26

In Hinduism . . . god resides everywhere, especially in other human beings; perhaps touching brings them closer to something bigger and higher and holier than themselves.

glassworks

My first teacher had never asked. Each time he pushed my thighs up and back into a downward dog or lifted my hips higher in a backbend, it put me in my body, took me out of my mind. That touch had awakened every muscle from the soles of my feet to the crown of my head, free of shame, stigma, or second thoughts. That touch had given me back my body after pregnancies and motherhood had overtaken it.

Betsy’s teachings made me understand how fortunate I was to never have been harmed by touch. Her instruction reminded me to never take that for granted.

Two years into teaching, I led a mother-daughter yoga workshop in White Plains. Toward the end, I instructed everyone to face their partner, clasp wrists, take one giant step back, bend knees, and fold over halfway for five breaths.

“Moms, child’s pose. Daughters, come watch.” After asking permission, I pressed the heels of my palms up and down either side of one mother’s spine while her daughter stood aside. “Girls, you try. Remember to ask Mom if it feels good, if she’s okay.” Stiff minutes passed. Nervous energy filled the room. Gawky teenagers fidgeted with their hair.

For the next thirty minutes, I kept them in partner poses: back to back, feet to feet, hand to hand. During the final resting pose, I noticed the silence. The girls’ dis-

comfort or self-consciousness shed or forgotten, mentally overcome by the ancient practice.

“Thank you,” one mother said after class. “You don’t know how much I’ve missed touching my daughter. I felt that hole, and today, I filled it.”

Only after hearing that did I understand my motive for teaching this workshop. I, too, had ventured into this no-touch zone with two teens and one tween. I, too, felt that hole and longed to fill it—if only I could figure out how.

During our volunteer assignment in Goa, Simone and I share a separate, sparse bedroom down the hall from three twenty-something-year-old European women in a two-story peach house with cranberry trim built by the Portuguese.

“This okay?” I ask while we unpack.

“Sure,” she shrugs. “Whatever.”

Throughout our weekend in the country’s largest city, we bonded over the second-class women’s compartment in the train, the off-putting odors of animal excrement and garbage, and our Evel Knievel tuk-tuk drivers. We talked at length about poverty and wealth and the unjust gap amongst them and between them and us in

~

|

glassworks 27

Jennifer Lang

On Common Ground

the western world.

At dinner with our housemates, Simone and I choose chairs across from one another. Conversations start and stop. Simone tries not to address me as Mom in their presence, and I vow to abide by her wishes not to kiss her or take pictures together in front of them or the rest of our group for the next fourteen days. During the day, she’s been assigned to tutor children of migrant workers, while I’ll work in a women’s shelter.

On my first afternoon, I’m greeted at the front gate and ushered up to the classroom, where a dozen girls come for homework help in English, their second language. There are a few plastic chairs, a small chalkboard on the ground, and a trash can. I remove my shoes and sit on the straw mat. A group of pre-teens gab in Konkani, the local dialect and mother tongue. They live at the shelter for a variety of tragic reasons: no parents, no money, no food.

“Didi, who are you?” a loudmouth lassie asks. Didi means older sister or cousin and is often a proper name or form of address.

I introduce myself. A thin, dainty, black-eyed girl taps my shoulder. She opens her book and squeezes next to me. I ask her to read. She hesitates. The story is about the Thar Desert: its climate, vegetation, and temperatures. Every few words, she pauses to breathe and summon the courage to continue. When she finishes

the one-page text, I slide my pointer finger under the words one at a time to reread it.

“Didi, you have sons or daughters?” she asks, leaning into me. Her arms are as slight as twigs.

I share my children’s names and ages. She weaves her fingers through mine. As I gaze at our Oreo-cookie-colored combination, I marvel at how much easier it is to touch a total stranger than my own daughter. Our connection makes me think about how spending time in a foreign culture can change your attitude toward touch.

At the end of my shift, I tidy the room, turn off the lights, and say goodbye.

“Tomorrow?” my new friend asks, wrapping her cotton-light body around mine. I startle, caught offguard by her openness and trust. Perhaps it’s because she was raised in an environment that has less taboos about touching or less boundaries between people; the population is so dense that it’s impossible to avoid unintentional contact in the streets of Mumbai. Perhaps she craves maternal contact and hopes I can fill those holes.

A gaggle of girls swarms, accompanying me down the stairs, through the courtyard, to the gate. I want to hug and be hugged by them all. Because I want them to know they count and people care. Because I want them to take away my own sting of loneliness. Because I want glassworks 28

them to understand the distinction between alone and lonely. ~

times we kissed and said nothing at all.

Les bises broke tension. Often, they served as a conversation starter since people did two, three, or four, depending on where they hailed from, whether Paris, suburbs, Provence, or elsewhere.

The first time I spent significant time in a different culture was in the late 1980s, after college, when I worked as a bilingual assistant for the French Section of the World Jewish Congress in Paris. Whenever my colleagues invited me to holiday dinners with their parents, or friends brought me to parties with their peers, we performed quick little kisses on each cheek. We kissed when we arrived at a social gathering, when we reunited after an absence, when we gave or received a gift, and when we parted ways. We kissed morning, midday, night. We kissed whether or not we knew each other’s names. Sometimes we kissed and said bonjour, salut, au revoir; some-

As I brushed cheeks with the French on a daily basis, I thought about my parents, about our lost physical connection, wishing we could rewind time. In California, we had no such customs or understandings. With our stodgy neighbors, we waved at one another in the driveway; with close family friends, we hugged, depending on how much time had elapsed between get-togethers. No one I knew in America was consistent or ritualistic when it came to the first of our five senses, and I thought we might be more united, less harmful or hateful toward others if we taught our children a shared, unswerving, ceremonial form of human contact like les bises.

Every night in bed under the Goan stars, Simone and I swap stories about our days. During my afternoons at the local shelter, she teaches division and multiplication to children from other parts of India.

“I don’t know if the kids understood what I did today,”

~

29

Jennifer Lang | On Common Ground glassworks

”

“ Because I want them to know they count and people care. Because I want them to take away my own sting of loneliness. Because I want them to understand the distinction between alone and lonely.

she says, “but they’re so adorable, really smart.” Her voice is animated, full of compassion and admiration. “I don’t really get where they go next but know they aren’t staying long. It must be so hard.”

I listen. She rambles. Wild dogs yelp outside our window.

“Thank you, Mom, for doing this with me.”

The previous summer, Simone spent a month at a monkey rehabilitation center in South Africa, cleaning cages and caring for the mischief makers. After her required national service in Israel, she intends to spend three months doing medical outreach in a developing country with a Jewish Agency program. My husband and I beam, sure she will one day head a nonprofit organization and presume she gravitates toward these humanitarian causes because of her own issues. Or maybe her call to serve stems from a desire to get perspective on the world and where she fits in it.

“I’m so happy to be here,” I say, shoving aside my heartache and homesickness. ~

According to marriage counselorturned-author Dr. Gary Chapman’s The Five Love Languages, people show and receive love as expressed through one of five languages: words of affirmation, quality time, receiving gifts, acts of service, or physical touch. While we enjoy some degree of each, and all five count, we

usually prefer one above the others. Intrigued, I took a quiz on his website. Each sentence began with “It’s more meaningful to me when” followed by two choices along the lines of “I receive a long letter/ email/message from my loved one or my partner and I hug.” On the last screen, my final tally appeared: 10 physical touch, 7 words of affirmation, 6 quality time, 5 receiving gifts, and 2 acts of service. It explained that touch fosters a sense of security and belonging in any relationship and extends way beyond the bedroom to hugs, pats on backs, and arms over shoulders, all ways to show concern and love.

Is this my dominant language because I grew up in the land of touchy-feely Northern California, because my brother often ignored me and I sought attention from others to compensate for my loneliness, or because I was the smallest in every social setting be it school, Girl Scouts, or camp, and my friends always picked me up, calling me Baby and cradling me in their arms? Could it be because touch reminds me of my grandparents and evokes a feeling of unconditional love? Maybe all of the above, maybe none of the above.

No wonder I teach yoga. No wonder I noticed the hand-holding men in India. No wonder I crave contact with Simone and her siblings.

Touch anchors me. For the past three decades, since leaving for glassworks 30

college in the Midwest, I’ve moved— cities, states, coasts, countries, continents—never spending more than six years in any one place. I’ve been trying to feel my feet on the ground since the first time I stepped on a yoga mat in 1995 and my teacher told us to root ourselves into the earth.

Whatever the reason, gentle, loving touch is a lingo I want my children to speak with me, with their father, with their future boyfriends and girlfriends, husbands and wives. ~

Simone and I settle into our Air India seats for our return flight to Mumbai, where we have a long layover before the plane to Tel Aviv. We’re tired, eager to sleep in our own beds, and eat pancakes and waffles for breakfast.

“It’s a famous line from a movie when the main actor, Humphrey Bogart, tells this woman he loves, ‘We’ll always have Paris.’ What I’m trying to say is…”

“Oh, sure.” She cuts me off, preparing to insert her ear buds. I wait. Neither one of us moves. I think about what I’m trying to say, wondering if touch is my preferred love language because it’s easier than words.

I push through the awkward and the uncomfortable. If touch is a language, it seems we instinctively know how to use it. But it feels more like a skill we fail to acknowledge, forget to appreciate. In the past, my parents and I failed and forgot, a pattern I don’t want to repeat

She removes her iPod before stowing her backpack under the seat. I lean over and extend my hand. “Well, Simone, we’ll always have Goa.”

“What?” she says. “I don’t get it.” Her big eyes growing bigger. My hand lay on top of hers.

with my kids. In the future, a global pandemic will steal it from us like a criminal, a period of time I don’t want to repeat during my lifetime.

My daughter and I have shared an extraordinary experience, and despite the sting I feel

Jennifer Lang | On Common Ground

“ I push through the awkward and the uncomfortable.

” glassworks 31

If touch is a language, it seems we instinctively know how to use it. But it feels more like a skill we fail to acknowledge, forget to appreciate.

every time she pushes me away and puts up walls, I understand now. It’s not about me. I might gravitate toward physical touch, but she might express her love through acts of service. As her parent, my duty is to accept her for who she is, to give her the freedom and space to use whatever language makes her feel the safest, seen and heard.

Simone sighs: heavy, exasperated, hormonal. I close my eyes to block it out and keep my hand on hers where it belongs.

glassworks 32

maCrame from The sea 56 Jim Ross

beCause I’m lonely /I wanT To know

The sound of love / reTurnInG

Sheree La Puma

When I ask my daughter what forgiveness means, I am thinking of her birth. The cold night air that surrounds a house ready to displace its occupants. I didn’t expect it to be that bad—the sounds a body makes unraveling. Anguished in the losing, I tried my best to keep to her. Minute by minute, as if this time might last, forever. Need. Love. The whole of the universe singing. We had it all before the nurse, footsteps receding as if she knew something terrible. How easily I might snap when pressed like a four-year-old that looks to the sky and sees nothing except string after a balloon breaks free. Give me a light to focus on. Help me forget my purpose as mother is to become entirely stranded.

glassworks 34

day-To-day

Katee Irene Fletcher

in a room full of single strangers i want his piano fingers to support my spine. i want him to kiss me with mango tongue and say that my cheap jewelry is a turn-on. i want to share soft shirts that hang to my thighs and eat bites off a single ice cream spoon. i want to layer myself like paint beside him when the sheets feel cold and whisper about my nightmares.

on thursday he brings me paper-wrapped flowers to make me blush. we lay in bed while i ribbon-wrap my knuckles in his yellow hair. when mascara trails my cheeks in the shower, he calls me beautiful and now i only want his voice to trace my eardrums.

glassworks 35

William C. Crawford

glassworks 36 forensIC fInds 2

The paIn sCale

Audrey T. Carroll

0 No Pain (No Gain)

I’ve never known if, when a doctor asks you to “rate your pain, on a scale of one to ten,” you are actually allowed to say “zero.” I’ve been too afraid to ask, because if my pain is a zero, then what the hell am I seeing a doctor for anyway? My pain is always discounted to begin with, so why would I willingly give the ammunition to ignore my body’s cries for help?

To be fair, it has been a long while since I could truthfully say “zero”— so long, in fact, that I don’t remember when, so even asking at this point would be a hypothetical waste of everyone’s time. For one thing, I’ve had pain half the time from the July before my thirteenth birthday until I was in my late-twenties (see point seven), and ever since it’s only been a matter of measuring degrees, but maybe before all of that there was a time when the days with pain stood apart from the days without. ~

1–3 Mild Pain (nagging, annoying, interfering little with activities of daily living)

AKA Why are you here?

1. It doesn’t sound so bad, does it? My foot missed the board of the scooter, and the wheels rode along the concrete sidewalk where it was broken, shooting up like a ramp in

a skate park. I had been navigating this mini-hill for years, where roots must have been growing aggressively underneath care of the enormous tree that stood between the sidewalk and the road. But the scooter was new, and so was my balance on it, and so I missed my footing and collided with the ground. (This will be a pattern, this loss of balance, though I will not think about it much for another fifteen years.)

In truth, the skinned knee hurt, but it was nothing major, no broken bones. It was a lot of blood, the sight of which made me dizzy (dizziness—another pattern to keep an eye out for), and I can still remember the hot red gushing down the front of my leg and staining the top of my white sock folded over. What I remember more than the pain, more than the blood, was the adult body blocking the front door, refusing to allow me inside to clean and bandage myself until I put the scooter away because someone might steal it. The potential harm to property outweighed the realized harm to my own child-sized body.

(Childhood and pain weave together again and again—the betrayal of blood, the lonely physicality of labor, the callous disregard for the little girl who stared up to look for help from her elders.

glassworks 37

Pain is recursive. It is not linear; it resists the confines of narrative.)

The implied confession would stay with me long after my skin knit itself back together so well that no scar remained. And the confession would become louder as the years passed, the way the “too-big” shape of the child-body is mocked into reduction, the way the body is trespassed and its pleas for help ignored, the way that threats are laid like broken glass within a windowpane, all while they insist that nothing has cracked. These same adults who do not believe will never believe, their certainty a tool to will silence, to ignore pain within and without. And this will return, too, this edict to ignore your pain, it’s in your head, talking about it just makes it worse.

skin which is hurting in its most basic job of existence, skin which is peeling to escape a damaged body; this pain is disbelieved, an immeasurable thing and therefore unimportant. Stop being so dramatic.

Again, before I’ve ever heard the word for it, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t you remember?

Or perhaps: a post-surgery stitch not believed. The surgery itself was not felt, though awake. Incisions were made to remove a wisdom tooth before it took root, stopping the thing growing sideways and forcing all the others to grow sideways along with it. The after-pain transforms, moment to moment,

2. What is the dead center of nagging and annoying? A contender: a sunburn so bad that my arms oozed clearish yellow, that we had to go to the doctor, that movement hurt enough to carve out a place in memory. It is the interferences that are the most vivid, the way a new wool uniform kilt slides over sunburnt

sharp to dull to pulsing to swelling. The pain is a chameleon, no way to describe its color without the next moment proving you wrong. I wanted to obey the instincts of my body, to keep my mouth closed, to keep my tender insides protected, to prevent myself from spilling yet more of my own blood. And demands

“

glassworks 38

The after-pain transforms, moment to moment, sharp to dull to pulsing to swelling. The pain is a chameleon, no way to describe its color without the next moment proving you wrong.

”

made by adults: open wide so we can see, the same people who would tell me in any other circumstance to do the exact opposite. All efforts to explain pain ignored, treated as strange fantasy, until a doctor confirms that stitch does, in fact, weave through cheek.

And once again, the same group of adults gaslight my body’s reality; the lights are not dimming, you do not feel so much pain—it is only in your head, don’t you remember? Childhood and adolescence prepare you for The Real World; I do not yet realize how few will believe my kind of body’s experiences there, either.

3. Twenty-one years with no broken bones, and then an elbow fractured just enough to spiderweb X-ray images. I was young, and so perhaps can be forgiven for the lack of insistence and vigilance that I would learn in the years to come. When the doctor said to use a sling for a week, I did; and, when he said to start moving the arm at that time, I did. During the flooding of the rivers from hurricane skies, I pushed through my pain, sure that it must be normal. I did not know yet that the same doctor had ignored an acquaintance’s complaints of pain until she was diagnosed with strep throat in urgent care. I did not trust my own body’s pain, my faith instead in a professional who didn’t so much as schedule a follow-up appointment.

In the aftermath of the break, there were the little interferences

with activities of daily living: showering, styling hair, carrying books. These interferences work as a kind of foreshadowing more than anything, a glimpse of what life will be like when a cane occupies one hand and solutions must be calculated at every turn. ~

4–6 Moderate Pain (interferes significantly with activities of daily living)

AKA Find the measurable evidence.

AKA Can you get off the couch if it’s not an emergency?

4. The rumor was that adults can’t get hand, foot, and mouth disease. This, as it turns out, is a lie. The pain was middling: if I absolutely had to, I could get off the couch, though it hurt the bottoms of my feet every time as though the skin had peeled and regrown and was still tender. I couldn’t walk without pain— not stabbing, not searing, but still present in every step, like a toned-down version of the original Little Mermaid tale. This was not the version of my childhood nostalgia. I never really thought about the distress of losing one’s voice in any version of the story—a voice lost not by stitches sewn or authoritative glares, but by choice.

The itching of the disease was bothersome, of course. The red spots and weak nails were the

glassworks

Audrey T. Carroll |

39

The Pain Scale

only measurable factors. The worst of it, though, was the way that I could feel the skin in my throat peeling, could feel the damage of each individual sore. I couldn’t drink water or eat without pain; even letting my throat naturally constrict the way that it must’ve done hundreds of times every day before only served as a constant reminder that I was sick. (This was still in the time when my body had to remind me it was sick; after a certain threshold, other people help you remember, too.)

5. This is the threshold for the COVID vaccine. I had read the warnings for weeks about the vaccine on Twitter from those with fibromyalgia and other varieties of chronic pain. These reports were criticized as scaring people away from getting vaccinated; I suppose I put aside thoughts about the way that people fear one day of the kind of pain that I live with regularly. And then others —many able-bodied, perhaps— countered with their mostly asymptomatic stories of It’s not so bad, look, it was only a sore arm for a few hours, oh I was just tired, no worse than a mild flu for a day, the assurances to the unvaccinated drowning out the forewarnings to the ill and disabled. It is not common knowledge, perhaps, that the ill and disabled know what to do with rationed time and energy, and clarified expectations are a miracle of knowledge in that process. But the culture downplays (disbelieves) (disregards) disabled bodies and

experiences (ill bodies and experiences) (female/femme/female-coded bodies and experiences). The shaming of those who shared lessthan-pleasant experiences became a deluge of persistent positivity.

I was prepared for the first vaccine to cause a flare, but I hadn’t realized just how much it would be a trip down memory lane to my pre-medicated, pre-diagnosis fibromyalgia: pain all over (especially in my trigger points), memory issues, problems doing simple physical tasks, feeling dazed and exhausted. With the second vaccine dose came even more pain, sleepless nights, a back that could find no comfort. Dose two also came with chest pain, a tightness like either a heart attack or, I eventually realized, hyper-localized labor pains. And the booster brought with it fever, fullbody sweats, intense pain in both arms, and a deep aversion to leaving the couch.

It was impossible to imagine how the pain rated separate from fibromyalgia, almost as impossible as it was to imagine how bad these experiences would be if my body was still undiagnosed or untreated, if it was this bad with the Gabapentin.

(This is the trouble with the pain scale: how does someone with chronic pain rate anything? Do you account for your baseline? Do you rate based on whatever is considered “normal”—i.e. there should be no pain at all? We can’t really share pain.

glassworks 40

It is a lonely and singular experience, even if you are with someone who might also understand it from their own experiences. And even when we try to share our pain, how often is it not believed or not understood for any number of reasons? You’re just anxious. You’re just depressed. You just need to drink more water. You just… you just… you just…)

I used ibuprofen like I had used with undiagnosed fibro, a heating pad that I had gotten for the unbearable pain when my endometriosis was out of control, and ice everywhere that I reasonably could. This, too, is one of the lessons of a chronic pain condition: so often, you are on your own; so often, you must design your own solutions, engineer your own comfort, because it is so infrequent that someone else will help you manage. This was a lesson that I learned early, well before any symptom of chronic pain bubbled to the surface.

6. Contractions weren’t the first sign that I was in labor. I had woken up at 11:30 at night, my body telling me to stay awake while remaining coy as to the matter of why, and then my water broke in bed and the entire way into the bathroom. It wasn’t until after I had been tested at the hospital, confirmed to be in labor, and in my designated birthing bed, that the contractions started. I was told to get some rest, but that was impossible. I was very clear from the get-go: I wanted the best

drugs that insurance could buy. I was informed that the anesthesiologist didn’t get in until 9:00 a.m. and I would have to wait. (I don’t know if he was actually a half hour late to my room or if that’s the memory warping of pain talking.)

It was like some of the worst cramps of my life—migraines are to headaches as contractions are to (even endometrial) cramps. The pain would compress in my uterus and then shoot intense signals all around my torso. I was in tears; it was difficult to even breathe. I don’t think I could have gotten out of bed in an emergency, and it would have been more merciful if the pain would’ve knocked me out. It was approaching mind-altering pain territory, with slight hints of my brain sending warnings that I was dying. I was no stranger to the feeling of my body betraying me; it had been

Audrey T. Carroll | The Pain Scale

” glassworks 41

“ We can’t really share pain. It is a lonely and singular experience, even if you are with someone who might also understand it . . .

two years since being diagnosed with fibromyalgia, a condition where everything is processed as a threat and reacted to accordingly. Perhaps the body’s self-betrayal is yet another threshold of this level of pain.

This will not be the last time that pregnancy makes an appearance on this pain scale. ~

7–10 Severe Pain (disabling; unable to perform activities of daily living)

AKA The ratings where doctors stop believing you.

7. This is the nexus of “your pain is normal” and “you can’t be in this level of pain.” The “fifth vital sign” can be pain. Other times, the fifth vital sign is the menstrual cycle. The four standard vital signs are body temperature, heart rate/pulse, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. The process of expressing “menstrual troubles” (i.e. undiagnosed and untreated endometriosis) to doctors often goes something like this, whether explicitly or implied: Being in severe pain for half of the month (translation: half of your life for all the years that you could potentially give birth) is normal and natural; using double the feminine hygiene products that you should be is normal and natural; full body pain is normal and natural; only experiencing relief for two weeks out of the month is normal and natural. Just try harder to perform the activities of daily living. Cut back on the caffeine that allows you to concentrate at work; exercise more with a disabled body prone to chronic pain;

take some ibuprofen and it’ll be fine.

It took endometriosis getting exponentially worse post-pregnancy and a doctor who believed me to get treated; I imagine there are lots of women unlucky enough to have the former and then even more unlucky in their lack of the latter. Alleviating pain seems like something scientific and sure and medical; it should not come down to something so fickle and intangible as luck, and yet—

Note: Could also be interchanged with number eight. The shades of pain are difficult to parse.

8. There is no standard “sixth vital sign,” but gait is something that can stand in for it. This is the threshold of “Can I shower independently?” and the answer is no. Untreated and undiagnosed fibromyalgia symptoms may include: medical professionals who don’t believe you until you come in with a cane; dizziness; pain; a neck that feels constantly on fire; inability to think; inability to concentrate; inability to remember; and, yes, inability to shower independently. This is not a pain that can be countered with whatever you might pick up in the supplements aisle at CVS, and it can get worse the longer you’re unable to convince a doctor to believe you.

(This process of manifesting belief is in part dependent upon your ability to perform a persuasive essay, but in even larger part dependent upon a medical professional taking you seriously.)

glassworks 42

There are no signs that they can measure, at least not traditionally: your blood work will show nothing; your CT scan and your MRI will show nothing; the billion-and-a-half pregnancy tests that they make you take will show nothing. The root of the controversy in the medical community regarding fibromyalgia is the disbelief toward self-reporting, the trouble of getting people to believe pain at all, nonetheless a particular severity of pain.

The designated medical professional must prod you in predetermined places—“trigger points” when I was diagnosed, though I’ve seen them called “tender points” now. Maybe “tender points” are less violent, maybe it’s a phrase meant to encourage the idea of tenderness in chronic pain. Or maybe there’s some random medical reason for the swap, because I find it difficult to believe that fibromyalgia has someone working PR to make it sound less threatening than its long and complicated-sounding name might suggest. Whatever you call them, these points are both: the places where pain radiates are triggers— they are violent—but they are also tender—they have violence enacted upon them. It is a survival instinct, a coping mechanism, fibromyalgia, but it is also and always a body turning anticipation into violence against itself.

9. Pain is not linear; it is recursive. The same event can have separate

moments in separate rankings on the pain scale, just as completely unrelated pains can take up the same intensity on the scale. In truth, I have never told a doctor that my pain level is at a nine, not that I can recall. I don’t know if I would even be believed if I did make this claim aloud; I’ve been disbelieved enough times that I never bank on anyone else’s trust in my reports on my own body. But the twenty or so minutes where I had to resist pushing during labor, though my daughter and my body both protested, likely belongs here. It was a difference of a half a centimeter of dilation between me and freedom, between my daughter and freedom, and I couldn’t even measure that amount between my fingers.

(Expressing the intensity of labor pain is cliché, so talked about as a marker of extremity that it is often disregarded as overwrought and melodramatic. Overwhelmingly this dismissal is made by those who haven’t experienced it for themselves. The perspective of the one who experiences the pain is not taken as truth. What is truth when it comes to pain? Why is it so often allowed to be defined by those outside of pain?)

This is my “Could I get out if there was a fire?” level. The answer is a resounding no.

glassworks 43

Audrey T. Carroll | The Pain Scale

The world could burn around me in those minutes, and I’m not sure that I could have even been able to bring myself to care.

erally experienced alone. There were others nearby, but no one conscious, no witnesses to even contradict it. No matter the number assigned,

No matter the number assigned, often arbitarily, to the experience of pain, there are two constants: the people who will not believe you, and the aloneness, always, of the hurt itself.

10. Literally blinding pain. One missed painkiller in the bleary sleep-deprived fog of postpartum life. As I returned to bed— from the bathroom? From feeding the baby? I can’t quite be sure—I felt a pang so strong in my core that I literally fell over. After so long a time spent with dizziness, I managed to artfully collapse against the side of the bed, still half-standing. I do not know if it was being vertical that left me first, or my vision, but for however long it took, I stayed in place, in a state of near-unconsciousness, simply feeling the afterwaves of the most painful seconds I’ve ever experienced, a pain that somehow surpassed even the literal acts of labor itself. (I suppose this is not a true mystery: one experience had an epidural that could be delivered by a button’s press, the other did not.) There was no doctor to report this level ten pain to, of course, in the dark of night in my own bedroom.

My worst moment of pain was lit-

glassworks

often arbitrarily, to the experience of pain, there are two constants: the people who will not believe you, and the aloneness, always, of the hurt itself. No matter the pain that comes next to unseat this one and that, the constants will always be there, fixed stars blinking back in the dark.

“

”

44

my aunT’s loCkeT

Emily Jahn

Around 4 o’clock in September, light the color of its polished exterior glances off the gold, hinged heart of my aunt’s locket suspended mutely from a desk lamp graceful in its role as a surrogate throat for this chained, refractory heirloom of my deceased relative. I’ve worn it—that smooth, metal heaviness; slid my fingernails into the seam where it holds itself together, the heart; pulled it open to find it empty: no picture, no words. Nothing to indicate that it was loved as the vessel of something cherished. So like a dead thing. I nudge it absently on quiet Sundays, its broad, flowered map shining on these fading autumnal afternoons, bleeding colder and colder one morning at a time.

glassworks 45

nepTune’s Candle

Emily Jahn

Winter carries on amid faint bird calls and mist, cold being extracted from the Earth like carbon in the scarred skeletons of fallen trees. When everything unknown was human they would burn bulls, show the presence of the gods in little sparks, in wavering haloes of candlelight at the height of summer. The marriage of heaven and Earth had a name, the rivers were spoken for and the caprice of the sea explained. When I was a child I would pray through the votives of the church, see Christ flicker faintly on the stone cheekbones and lowered eyes of the saints, specks of grace carried softly to speed the journey to the summit of Dante’s gray mountain. The dead are kept burning there under the stone arches, stained glass and marble. I was thinking of the water god, the deep blue planet turning in its vacuum, glimpses of the sun its own tiny offering: some hint of the divine.

glassworks 46

orChIds Emily Jahn

They cannot grow here in the pale light:

soft heaven of late winter’s heavy calm. Rich

and deep, purple-winged, arching on green stilts like a dream, like Dalí’s delicate scaffold. I never said

I wanted happiness, never asked for those fragile, satin petals—

remnant of spring— duped into blossom

this time of year. For my life to be seamless somehow, home to bright gardens, multiplicity, and fecundity, orchids

and their sweet perfection lingering in the rain-streaked window’s terrible gray shine.

glassworks 47

maCrame from The sea 30 Jim Ross

glassworks 48

glassworks 49

The soluTIons To a younG woman’s problem

Alison Matayosian

Solution 1:

You feel the faintest twist in your stomach that something isn’t right, and the first thing you do is pee on a stick in the communal dorm bathroom. You see that second line appear in the tiny window and you know your life will not be the same. You’re only a college freshman, the first in your family to go further than a high school diploma. You barely know the man who impregnated you after a couple nights of “hanging out” and watching horror movies in his room down the hall. You could pretend it never happened. You could ignore the growing, changing body that is slowly trapping you. Ignore the morning sickness that is already making every piece of food that passes through your lips taste putrid. Ignore the judgemental stares and obvious looks of concern when people see first your rounded middle and then look up to see the baby weight still desperately clinging to your cheeks in your newfound adulthood. Live a life of makebelieve even as someone gently places a wrapped bundle in your arms nine months from now. ~

Solution 2:

You could search the internet for people who would do anything

to have a child of their own. Search for the mothers who will never give birth but have had a nursery painted the perfect shade of sage green for years. Watch as their faces light up at each ultrasound picture, even as your body recoils from the blurred image of black and white blobs. Hope they don’t see how much you’re dying inside as their family grows. Spend twenty hours in labor to hear a baby cry but never hold it. Spend every day for the rest of your life searching for your features in strangers’ faces. ~

Solution 3:

Call your mom and let her force you out of school. Move back home and watch what you eat. Listen to her list off baby names that she finds suitable, like Andrew, Cara, Loren, Michael. Watch as your life slowly morphs into hers. A single mother before you’re legally allowed to drink. No college degree to show at jobs that barely pay minimum wage but allow you to be with your baby every morning. Move from apartment to apartment because you are desperately searching for some semblance of comfort in a life you never thought would be yours. Watch as your baby grows into a person all their own and asks you questions about where their father is

glassworks 50

or why you can’t go to Disney during the summer like all of their friends. Resent that man you barely knew because you saw on Facebook that he’s a doctor now with a wife and a beach house on the Cape. Resent yourself for not trying to keep more of who you were intact. Resent your child for nothing at all.

as the pain pushes bile past your lips. Pull down your pants and press your lips together to stifle your cry as the blood and tissue drips down your thighs to collect at the knobs of your shaking knees. Take a deep breath and try to ease the pain stabbing at the lower half of your body. Spend the rest of the night in bed with a heating pad tucked into your side and a hand on your stomach. Close your eyes and imagine a baby with your chameleon eyes and that man’s ancestral nose. Think of a laugh that sounds like bubbles popping and cry at what might have been. Spend the rest of your life wishing you had had other options but loving yourself for choosing you.

Solution 4: Do what you know you were planning to do from the very beginning and call a clinic for an appointment the following week. Be poked and prodded by needles and probes to make sure nothing is wrong with you besides the foreign object growing inside of you. Try desperately to pretend like you don’t want to see the ultrasound screen that the technician has strategically turned away from you. Take the pill offered to you and set an alarm for the exact same time the next day. Take the second pill and the codeine-covered Tylenol for the pain. Run to the communal bathroom and hunch over the toilet

~

glassworks 51 “

”

Resent yourself for not trying to keep more of who you were intact. Resent your child for nothing at all.

lover boy

glassworks 52

Dalanie Beach

Dalanie Beach

self-porTraIT as a Gray november mornInG

Ellen June Wright

Overnight, some unseen hand stripped the trees naked.

They shiver in the icy nor’-east wind like those seeking warmth around a steel drum’s crackling fire.

Others like the maple are resilient and persist as they turn gold.

The last to relinquish its green will be the wisteria I thought was dead last spring.

glassworks 53

The monsTer we made Kevin Neal

In the giving woods, we pull the buttery shale from almost dry creekbed walls and knead it until it’s soft, until in our chests we know that it’s missing part of us, so we slice off our index fingers and make our monster in our image.

We love and nurture it, latch its mouth to breast, and so it grows small. It gums our fingers; prefers the severed nubs, and though our nerves are scarred it burns like electricity.

When it learns to stand on its own we pride ourselves to watch it. And then find it watches us while we sleep, wakes us with chilly fingers on our backs, familiar and foreign on its hand, taking our nights away from us.

While we grow old it turns young and beautiful. And in one night I wake with my ruined hand in its mouth. We try to save my hand, but in the end cannot, so I say goodbye and lop it off— watch it, dead and unfeeling, open like a lily on the floor.

glassworks 54

TIny bones

Millie Kensen

Maura Cotter watched the tendrils of steam rise from a chipped mug, the words STILLWATER HIGH peeking out from beneath four plump fingers.

“Want some?”

The scent of cheap coffee drifted towards her, wading its way through something floral and musty, reminiscent of gas station soap. Hushed sounds of idle chatter floated through the house, carried around on paper plates piled high with cubes of yellow cheese and blobs of mint-green pistachio pudding dotted with bright red cherries.

“No,” she told her aunt, who’d been hovering above where she sat on the stairs. “I’m fine.” Maura smoothed the edge of her skirt then stood using the banister to steady herself, the little white pill her cousin had slipped her finally starting to take effect. She’d insisted she didn’t need it, but she wasn’t one to look a gift horse in the mouth, especially when that horse was handing out free drugs.

“You sure?” Aunt Deidre asked. “Coffee always makes things better.”

“I stopped drinking caffeine last year,” said Maura. That was true, though she left out the part where the hiatus had only lasted two weeks. Detoxing from Starbucks to catch the eye of her hot yoga

instructor hadn’t been worth the caffeine headaches.

Deidre peered over the top of her wire-rim spectacles, the thick lenses clouded with fingerprints. “There’s decaf in the dining room. Lemme get you some.”

“I’m good, thanks.”

“You know, you should eat something. Bethy would want you to.”

Hearing her mother’s name made Maura’s mouth feel as though it were filled with sand. She considered slapping a palm across her aunt’s pig-like face, but the pill made her feel as though her hand might float away from her body if she tried. “Thanks, Aunt Dee, but like I said— I’m good.”

As if on cue, Maura’s uncle came around the corner holding a plate filled with rolls of sliced deli meat filled with cream cheese and chopped black olives. “Ham roll?” he asked, lifting the plate from where it had been resting on the mound of his gut. “Bev made ‘em. Says they’re good dipped in ranch.” He pushed one of the rolls into his mouth.

“How was the flight? Dee says you got in late.”

Maura shrugged. “Flight was fine. Same as usual.”