Len Lye Shadowgraphs

images:

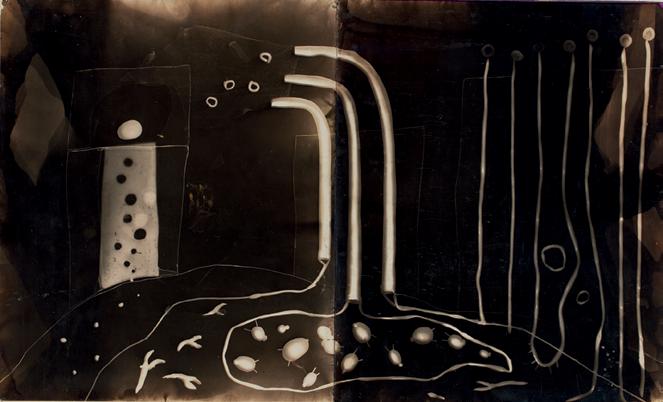

2–3 Doodle, 1947

4–5 Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden, circa 1930

The photographs presented in Shadowgraphs represent one of the treasured but lesser known bodies of work by Len Lye (1901–1980). Renowned for his experimental films and kinetic sculpture, Lye’s practice occupied a much wider territory than is typically understood. Before confirming his credentials as a leading figure of modern cinema (arguably with his 1935 film for the GPO Film Unit A Colour Box), Lye had established an eclectic practice during the late 1920s in London. Tin and cardboard sculpture, batiks, paintings and film stills had all been exhibited through the Seven and Five Society (at the time Britain’s most avantgarde artist collective), while his connections in the literary world (particularly to Robert Graves, Laura Riding and Nancy Cunard) produced a fascinating body of cover and bookplate designs for leading modernist publishers. We may expect amongst Lye’s multi-media practice that photography plays a part, and so it transpires, yet with a particular caution—no cameras. With just a few exceptions, Lye’s engagement with the photographic medium was almost entirely through the form of the photogram—an image produced with photographic materials but without a camera. One of Lye’s earliest efforts Untitled (Eye Bath, Fork and Light Chain) is a textbook example. In a dark room three objects were placed on unexposed photographic paper. When exposed to light the impression of each object was registered in the light-sensitive chemistry of the paper. We see the varying translucent qualities of the objects tempering the degree of chemical reactions under light— the opaque fork blocks the light from reaching the paper surface while the glass or plastic eye bath lets a degree of light through to ‘burn’ the paper (where no object obstructs the path of light at all, the paper is darkest).

This method of making photographs is often perceived as an alternative process to conventional

camera-based photography. However, the photogram is as old as photography itself, exemplified in the early photographic experiments of Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) and the botanical photography of Anna Atkins (1799–1871). The technique reemerged in the 1920s as an avant-garde form, popularised by artists such as Man Ray (1890-1976) and László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946). Lye engaged with the photogram during this period of popularity, producing in the years around 1930 a small number of works (just five extant from this period).

Self-Planting at Night (or Night Tree) and Marks and Spencer in A Japanese Garden are Lye’s most well-known photograms, each an entry by Lye into the surrealist cannon. Herbert Read (1893–1968), at the time a leading British art critic and impresario of British surrealism, included Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden in his 1936 text Surrealism while Read and his colleagues included Self-Planting at Night in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London (another photogram, Watershed was also included in this exhibition).

This small body of work represents a fairly precise but modest engagement with the photogram. Interestingly, Lye produced Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden and Watershed in batik forms during the same period, suggesting the photogram was simply one of a variety of modes that Lye chose to work in, and perhaps not his most preferred. However, this involvement with the cameraless-mode provides a fitting parallel with Lye’s approach to ‘direct’ filmmaking, largely abandoning the use of a film camera to make films where imagery is painted or otherwise applied directly onto film.

The photogram again re-emerged as a popular technique in the years following the Second World War, notably in the United States. Émigré artists such as Moholy-

Len Lye, 1940s

Len Lye on set of Basic English, 1944

Len Lye in studio working on Colour Flight, 1937

Len Lye, 1940s

Len Lye on set of Basic English, 1944

Len Lye in studio working on Colour Flight, 1937

Nagy and György Kepes (1906–2001) generated a new vitality in the form and in 1947 (now living in New York) Lye again reconnected with the photogram, this time in a much more intensive fashion and employing his own term for the practice—the ‘shadowgraph’. Within a single year Lye produced dozens of new shadowgraphs, several of which (such as Doodle and Cigarettes and Ashtray) suggest a return to the surreal, yet the bulk of the group comprises portraits of friends and acquaintances of Lye and his wife Ann (1910–2000).

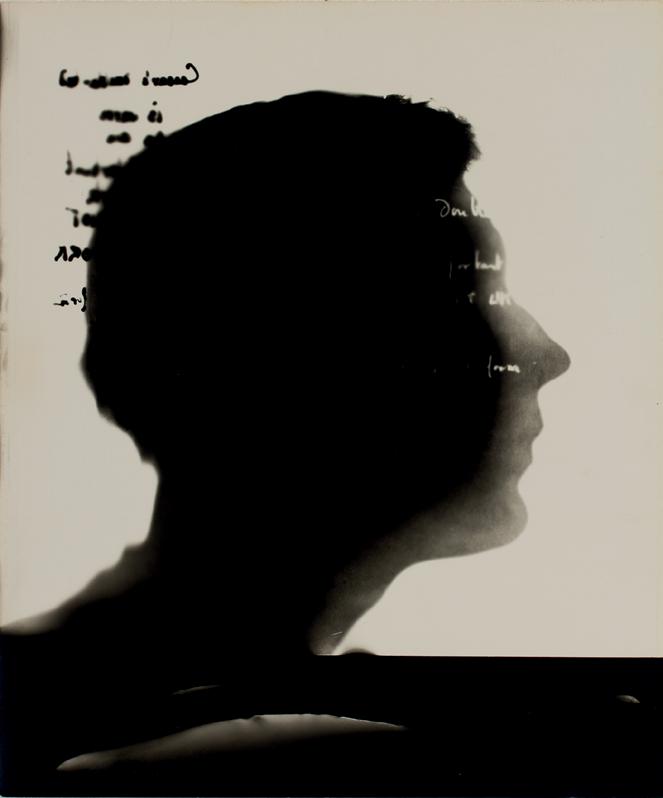

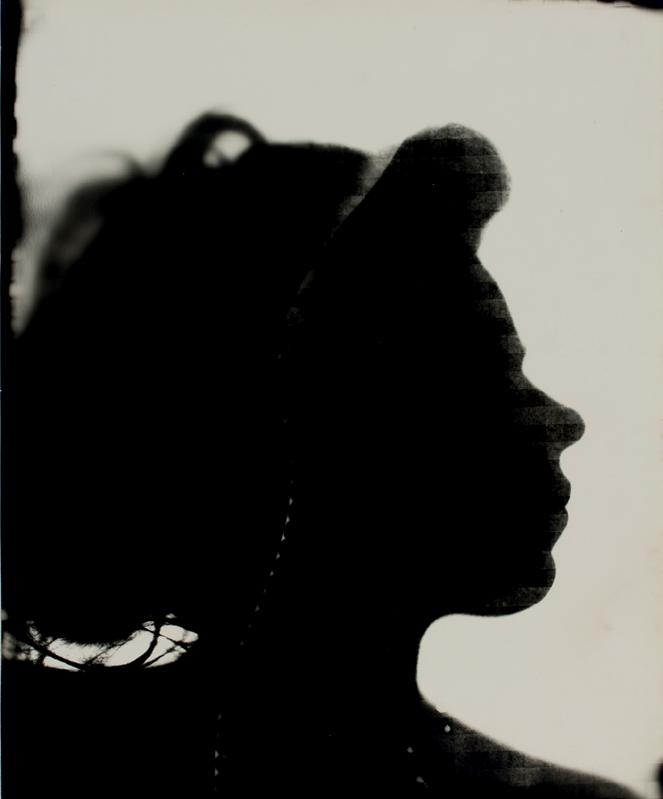

Few artists produced portraiture with the photogram and none so extensively as Lye. Forty-one unique portraits by Lye are extant, capturing 17 individuals, from his plumber Albert Bishop to recognisable figures such as the painter Georgia O’Keeffe and the architect Le Corbusier. Invited to Lye’s studio, the sitters posed in the dark with their head against an unexposed sheet of photographic paper. When exposed to light, their silhouette was captured. This simple portrait provided Lye with a negative from which further prints could be generated exposing a portrait print over a new unexposed sheet. Each iteration reversed the tones of the image and further elements could be added to the new image. Joan Miró added cut-out shapes. Antlers and leaves were added to O’Keeffe’s portrait. Patterns were sometimes introduced by exposing a print through lace (Jean Dalrymple), a matchstick blind (Le Corbusier) or a copy of the New York Times (Roy Lockwood).

Lye’s shadowgraph portraits have been largely unknown to the wider world of photography. There is little to suggest they were exhibited by Lye in his own lifetime and he has left us with relatively few comments on their production. Recent decades, however, have seen a steadily growing interest in both these portraits and Lye’s earlier photograms, and with this publication we present the

first complete survey of Lye’s photograms. Included in this visual survey is a bibliography of key texts and publications that discuss either Lye’s photograms directly or the wider contexts in which they exist. One important text, Wystan Curnow’s Len Lye’s Portrait Photograms is reprinted here with some minor revisions.

PAUL BROBBEL is Len Lye Curator at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. He was previously assistant collection manager of photography at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and a 2016 research fellow of the Henry Moore Institute.

Watershed, circa 1930

300 x 500mm

Earth Magnetic, 1930

300 x 250mm (approx)

Doodle, 1947

330 x 450mm (approx)

Trick, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

Althea, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

Althea, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

Althea, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

Althea, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

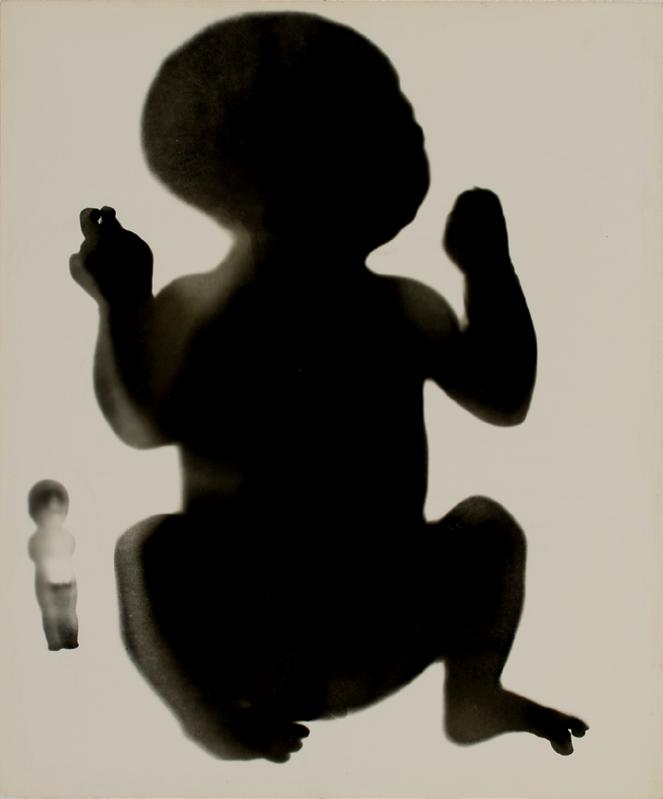

Baby Dodds, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

Untitled, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)

image: 70–71 Len and Ann Lye, 1970s

Len Lye was one of many artists whose sense of direction and purpose was radically affected by the Second World War. Continuing as an artist in wartime, or starting out as one, induced in many a sense of responsibility and privilege, of prohibition and permission that in times of peace would seem extravagant or simply uncalled for. Mark Rothko stopped painting and began working on a book-length manuscript on the philosophy of art. The critic Harold Rosenberg asked Barnett Newman to explain what one of his abstract paintings could possibly mean to the world. This was in 1947, not so long after Newman had taken up painting in a serious way, and, of course, not so long after the end of the War. Newman’s answer was that if Rosenberg and others could properly read his work it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism. War was over but what sort of a peace was it? Or take a different example, from somewhere far closer to the ‘Iron Curtain’ that for Churchill defined this Cold War limbo. ‘There was a time,’ wrote the Yugoslav artist, Mangelos, who had begun to paint during the War, ‘when people were dying but there were no ideas … in the time of dying the books smelled of death too and reading smelled of dying.’2 His small black monochromes, the Paysages de la Guerre, (Landscapes of War) have been described as ‘Flags of mourning, … evidence of the fruit of destruction, holes in the fabric of reality.’ It was 40 years before they were exhibited; as it was 60 before Rothko’s manuscript found print, as The Artist’s Reality. 3

Lye spent the War years directing information/ propaganda films for the Realist Film Unit in Britain and magazine-style news documentaries for the March of Time

series in New York. Although in these films he worked at his craft, it was clear that in practical terms his art career was on hold. This essay mainly concerns the immediate postwar years, 1946 and 1947 especially, when Lye was overtaken by a passion for writing, and made sporadic returns to art making. It has long been known that Lye produced a few paintings in these years, but the existence of the 53 photograms now in the Len Lye Collection and Archive in New Plymouth, remained effectively unknown until a few years ago. Yet these are surely the most significant of his works from the post-war 1940s. Unexhibited in his lifetime, they were first shown in quantity less than 10 years ago.4 A short catalogue essay by Judy Annear appeared in 2000, but otherwise little or nothing has been written about them.5 Their addition to the canon of Lye’s works should cause us to rethink its shape and character, and to ask whether their contribution to modern photography is at all comparable to Lye’s contributions to film and sculpture. But what of this new passion for writing? During long hours cooped up in London’s air raid shelters, Lye had begun to think about putting down on paper his ideas about what had gone wrong with the world and how it could be put right. Later, he showed drafts to friends and to people of power and influence who he hoped would be interested. It became a preoccupation. First in London and later in the United States, he continued to re-work his thesis –arguably, he did so for the rest of his life. First it was known as IHN (Individual Happiness Now), later as IDA (Identity Degree Act). He framed it as an essay for publication, a plan for political action, a grant proposal. It kept on changing in size and genre; the essay grew into a book, then into several books; it was a film script, a research project, a collection of stories, or prose poems, and so on. He never did publish it, not even a substantial part of it. To give you

an idea of how much it grew over this period: for the years 1945-1949, the Len Lye Archive contains nearly 50 files of variously incomplete drafts, many of them approaching book length.

One might conclude from this that Lye’s feelings about the war situation had convinced him he could or had to be the kind of intellectual he was never cut out to be, and that this delusion lasted him a lifetime, stealing precious time and energy from what he did best. That’s not my view. In 1944 his essay ‘Foreword to an Idea of Freedom’, as it was then called, took him to New York, in the first instance so as to meet with would-be Republican presidential candidate, Wendell Willkie, author of the best-selling, One World. Willkie had as a matter of fact expressed an interest in Lye’s ideas. Nothing came of that, but New York and Lye hit it off so well that he stayed and made most of his best work there. Lye did of course publish essays, both before and after the 1940s, addressing questions specific to his current concerns in sculpture and film but the War appears to have convinced him that this was no longer enough; that quite apart from whether publishers or others were interested in his new writing he at least considered it a necessity for himself as an artist. There seems little doubt that it was a way of keeping Rosenberg’s question (what could your work possibly mean to the world?) alive, for himself at least, and providing his version of Newman’s answer not only through the films and sculptures that were to follow but also the photograms which are my concern here.6

What is a Photogram?

A photogram is a photographic image made without camera or film. It is usually produced in a dark room by exposing to light an object placed on or near photosensitive paper which is then developed and fixed in the usual way.

Opaque objects contacting this surface block out all light leaving that part of the sheet unexposed, i.e. white. Shadows of these objects caused by lighting during the exposure result in varying gray-values depending on the density of the shadows. Areas flooded with light, that is, fully exposed, become black.7

Thomas Wedgwood’s photogram was the first, dating from the turn of the 19th century. Which is to say the photogram pre-dates photography proper, nevertheless the photosensitive paper Wedgwood invented was a step in the direction of the positive/negative printing, developing and fixing process of William Henry Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawings (photograms) of the 1830s. These in turn led to the multiplication of images which is an essential feature of modern photography. Fox Talbot’s photograms of leaves, lace and the like were exposed outdoors to sunlight rather than in the darkroom to electric light. In the early 1920s, Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy independently re-discovered the photogram as an art medium. As did Lye in the late 20s.8 Several of his paintings from 1928 were apparently based on photograms or vice versa, plans for unrealised sections of his 1929 film Tusalava were to include them, and two, Self-Planting at Night, and Watershed, 1930, were shown in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London.9

Few of their contemporaries followed the example of these artists; today, however, now the photographic media have turned the tables on the traditionally dominant art media, it’s not surprising that photograms are more widespread; Olafur Eliasson, Mona Hatoum, Sigmar Polke, James Welling, Günther Förg are among those who have made them.10 What distinguishes Lye’s 1947 photograms from his and others’ earlier efforts is that they are almost entirely portraits. In the dark, his ‘sitters’ lay their heads down on a piece of photographic paper before he ‘took their pictures’ by quickly switching the light on and off. I know of no comparable use of the photogram before or since. This is perhaps surprising given the often remarked on association of the photogram with silhouettes and the large role portraiture plays in the history of photography.11 The 19th century was the heyday of the silhouette portrait, when it served as a cheap substitute for a portrait painting – it is named after Étienne de Silhouette, Louis XV’s famously parsimonious controller general – until, that is, the portrait photograph took its place. Besides being cheap to produce compared to painting, the silhouette was also poor, in comparison to both painting and photography, in the amount of information it delivered about the sitter. Whilst the same applies to the photogram, to a modernist such as Lye its directness, or indexicality, gives it an advantage over other forms of portrait representation. Charles Sanders Peirce proposed three kinds of sign.

Firstly, there are likenesses, or icons, which serve to convey ideas of the things they represent simply by imitating them. Secondly, there are indications, or indices; which show something about things, on account of their being physically connected with them […] Thirdly, there are symbols, or general signs,

which have become associated with their meanings by usage.12

A portrait, whatever the medium, that is not a likeness is no portrait – that is, no genre of representation is more constitutively iconic than portraiture. On the other hand, in no other medium is iconicity more a function of indexicality than photography: the photographic image resembles its object only in so far as it bears the traces of the light physically reflected by it. If portraiture is a model of the icon, so the photogram is a model for the indexicality of the photograph, since its physical connection with its object is actual, not mediated – neither the optical apparatus of the camera nor the chemical positive/negative transfer intervenes. Paradoxically, it is the photogram’s lack of iconicity, its relative failure as a portrait, that serves as a guarantee of its claim ‘that something has happened [here], that something exists or existed.’ 13 Lye’s subjects, in silhouette, are primarily, and for the most part, existential human objects. First and foremost they declare: Wystan Hugh Auden was here. Warren ‘Baby’ Dodds was here. It is this combination of special cases, semiotically speaking, that gives Lye’s portrait project its unique conceptual power and affect.

A Portrait Gallery?

Even though, or perhaps because, the photograms are not much concerned with the individual appearances of their subjects, we still have to ask who Lye’s subjects are and

why he chose them? Roger Horrocks is non-committal, suggesting the subjects were friends and acquaintances willing to submit themselves ‘to the photogram ritual’. Judy Annear finds somewhat more purpose: the photograms are ‘in the main, celebrations [my italics] of the individuals who made up his circle of friends and colleagues in New York.’14 And I think they are both partly right. Lye’s subjects are a disparate group, they do include work associates from March of Time such as British expatriate Roy Lockwood,15 Ann Hindle, soon to be his wife, their local plumber, Alfred Bishop, a young woman named Althea, a young boy – Harry Watts Jr. – an unidentified baby, and a neuroscientist friend from the University of Columbia in her late 60s, name of Nina Bull.

On the other hand, there is clearly a group of six or seven subjects, all of whom I am suggesting Lye chose not because they could be prevailed upon but specifically because of the considerable prominence they had achieved in the arts: Le Corbusier, W. H. Auden, Joan Miró, Georgia O’Keeffe, Baby Dodds, Hans Richter, and Jean Dalrymple. Lye had some acquaintance with all of them, but none was a close friend, and it is hard to say if any of them belonged to his circle of friends and colleagues.16 Lye devotes between two and four photograms to each of them, and collectively they make up half of the total. Some other explanation seems called for.

Most of these people are very well known today, so it’s worth recalling that when Lye made his portraits of them their fame was recent or still in the making. That the moment of time in which Lye’s portraits came into existence, is linked to specific stages in the careers of his subjects. Georgia O’Keeffe was the first woman artist to be given a retrospective by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it opened in May 1946. Hans Richter’s, Dreams Money

Can Buy, won the award for Best Original Contribution to the Progress of Cinematography at the Venice Film Festival in 1947. Joan Miró was commissioned to produce a 91-metre mural for the Terrace Plaza Hotel in Cincinnati, then considered the world’s most modern hotel. In March of that year Le Corbusier completed scheme 23A, the basis for design for the new United Nations building. And W. H. Auden published The Age of Anxiety for which he received a Pulizter Prize the following year. If Jean Dalrymple was yet to win the plaudits that later came to her as a Broadway director and if drummer Baby Dodds’ renown was confined to an emerging group of middle-class enthusiasts for New Orleans jazz, Lye’s choice of them for his gallery suggests he wished it to represent theatre and music as well as literature, architecture, painting and film, and perhaps also to offset its European bias.17 They are a disparate group, but that is the point. While Le Corbusier’s United Nations building project and Auden’s new collection, as well as his poem ‘The Fall of Rome’ part of which appears in the poet’s hand on his photogram, clearly relate to postwar hopes and fears, they are the only ones that do. Miró and O’Keeffe are two quite different kinds of painter. Clearly Lye’s choices do not amount to a thesis about the arts or the time; they nevertheless present themselves as a cross-section, a representative sample, at a particular moment in time. We know about these figures today as people knew about them then: from their photographs; Lye’s photograms should also be considered in their relation to those photographs. Georgia O’Keeffe is perhaps the extreme example; she told Calvin Tompkins: ‘I’ve been a person other people always wanted to paint or photograph.’ Those other people have included Cecil Beaton, Ansel Adams, Bruce Weber and, famously, Alfred Steiglitz who, during the first two years of their relationship took over

200 pictures of her. It’s Lye’s choice of medium that’s his point of difference. The photogram in effect challenges the claims made by those pictures, individually and collectively by demonstrating that their subjects as images possess a double life. Lye invited his subjects to assume a position in an unfamiliar space, a crepuscular even nocturnal world in which they found themselves all of a sudden flash-bulbed into and out of an existence that must surely have been startlingly new to them. As it would be to any of us. We have all been photographed, so the difference a photogram makes applies to us all.

Perhaps to base an account of the photograms exclusively on this particular group, to regard his portraits of friends and associates as secondary may be to misunderstand Lye’s project altogether. There are, as we shall see, good reasons for organising the gallery in another but complementary way: around the images of human development. To start with there are two photograms of unidentified babies; attended by or implanted with a homunculus-like kewpie doll, they represent human renewal. There is also a young boy, named Harry Watts Jr., and an anonymous girl in pigtails surrounded by flowers and greenery, an unnamed young woman, and another named Althea. Gender differences are elaborated (Alfred Bishop/ Jean Dalrymple). Life and death (antlers and green leaves), nature and culture (lace and leaves) are intertwined. In this way the gallery introduces nature as well as culture, history as well as biology, and all the portrait subjects to the realm of the photogram.

In spite of the shock that terms like neuromuscular, motor-sensory, empathy and so on may give to the sensitive, philosophically-minded introspective artist and critic they will have to get around to such terms if they want eventually to bring the arts into relation with the age we live in. It is an age of scientific reference to the natural world we live in and to the life we enact and experience, Art manifestos and explanations of work in many catalogues these days look medievally inadequate.18

Lye’s new-found enthusiasm for behavioural psychology is startling. Artists and writers in the 1940s were still talking of Freud or Jung, and they were far from impressed by science. Maybe they were right; for all that it was and may still be, as Lye says ‘an age of scientific reference to the natural world we live in,’ very little of the science of the time that impressed him then has proved its worth. And yet it is true to say his interest in it is the key to his own ‘progress’ on from surrealism to what in art history is called abstract expressionism, and to the special understanding of the kinetic that is at the centre of his achievement. The photograms, which play a part in this progress, are a byproduct of Lye’s enthusiasm for science, and of the dialogue (even argument) with art which it fueled in his mind.

Late in 1945, working on ‘Life with Baby’, a March of Time assignment, dealing with the Yale Clinic of Child Development, Lye met Louise Bates Ames, curator of the Clinic’s film archive who quickly became a close friend and introduced him to many of her research colleagues and acquaintances.19 Later, he met and filmed William H.

Sheldon, whose Varieties of Temperament: A Psychology of Constitutional Difference (1942) had proposed a typology of body types based on systematic correlations between physique and personality. As with the work of Yale Clinic, Sheldon’s research relied heavily on the analysis of photographic images of his subjects. These uses of the camera as a research tool, would have reminded Lye of the role he had given film in his proposal to Willkie, they surely encouraged him to incorporate film into his own applications for research grants at this time, and are likely to have influenced his thinking about his photogram portrait gallery as I have called it.20

Through 1946 and the following year Ames worked closely with Lye, guiding him in his exploration of this new field and helping him incorporate its ideas into his writings. Of all her introductions that, to Nina Bull, a friend and a research associate in psychiatry at Columbia University, had the most impact. In April 1946 Bull published an article ‘Attitudes: Conscious and Unconscious.’ By ‘attitude’ she meant a positioning rather than an opinion. Her purpose, she wrote, was ‘to align the psychoanalytical concepts of unconsciousness and consciousness with the physiological concepts of attitude, by explaining them both in terms of a single basic neuromuscular sequence.’ 21 This sequence (XYZ) is set in motion when a latent attitude, a predisposition of the central nervous system, is activated by a stimulus. What then starts as a motor attitude (X) becomes a mental attitude (Y) and is followed by an action (Z). Of these three stages of ‘attitude’ the first which is neural (X) is completely unconscious, the second (Y) which is muscular is initially unconscious too, until it becomes conscious in the sense of acquiring orientation and intentionality, usually as a form of feeling, followed by a conscious act (Z). This elaboration of a physiological

unconscious appealed to Lye, particularly her proposed ‘motor attitude.’ Her new theory of attitude, he wrote, puts it:

fairly in its place, fair in the neuromuscular body of the organism where brains are what you think with and bodies are what you ‘with’ it all with. She indicates that all ‘attitudes’ reside right in the body; that the particular attitudes of how you happen to be in your being spring straight from the entire state of the person not partly this and partly that: that it is the body’s state that conditions the mind’s imagery state. The attitude to act a particular way starts up inside a person’s body without him necessarily knowing a thing about its starting.22

Given Lye’s longstanding interest in the connections between consciousness and movement, he found the idea that ‘neurons set up particular patterns of movement for the muscles to carry out before the mind of the person is aware he is about to perform any movement of purpose at all’ particularly compelling. However, ‘… the boo-hoo of psychology for me is that imagery is left out of the picture of the organism’s ‘attitude’ enactments. We, me, I say, simply can’t have motions and ideas without having them as images and the symbols as analogies to what ‘experience’ refers to.’ 23 Clearly, Bull was unable to allay Lye’s ‘boo-hoo’ in their discussions. The value of her theory for Lye depends upon the involvement of language broadly understood in the enactments of attitude, so he just incorporates it into his own version: ‘For, to me, this is the flash point instant, not only of attitude inception but also of image combustion ... OK.’ 24

These ideas certainly come to fruition with Lye’s return to the kinetic in the physiologically-oriented sculptures of

the late 1950s, and his subsequent writings on the subject, such as ‘The Art that Moves’, 1964. But more immediately it is hard to resist the conclusion that the ‘theatre’ of photogram production Lye set up a few months later was also informed by them. Wasn’t the photogram darkroom designed as a place in which to stage Bull’s sequence of neuromuscular attitude enactments as the procedure of portraiture? Both portrait subject and the artist are literally in the (almost) dark as they position, and otherwise prepare themselves for the imminent flashpoint of image inception. The instant of visibility is equally the instant of consciousness, the instant of being, of becoming somebody. It occurs to nobody except as they assume their roles, as artist, subject, as stimulus, response, in this theatre of the photogram. Each portrait is a discrete act of thought or feeling.

Lye now set himself the task of re-working his three key concepts – individuality, happiness, the present – in terms of human biology. For instance, the present was to be understood in terms of this flashpoint inception of image or consciousness. Or, as the necessary action of the organism adapting to change in order to survive. William Sheldon’s ‘varieties of temperament’ helped Lye to find a biological basis for ‘individuality’; it is something common to ‘all people in their own natural form as units of the process of survival. … it’s a factor that exists not only in people but also in the general run of all the things of life.’ 25 Lye quotes Edmund W. Sinnott arguing that the biological basis for individuality goes deeper than instinct:

It lies in the very architecture of our chromosomes, in protoplasmic mechanisms which insure that each of us is different from his fellows. Through all the course of evolution, advantage has still been with the species

which were variable and thus produced a wealth of different types for the great proving-ground of evolutionary competition.26

Applications of the ‘lessons’ of evolution to social policy have, of course, a long and not so reputable history; nevertheless, Lye is led to promote artists as models of individuality of this kind.

In this Golden Age of visual art with Picasso, Brancusi, Moore, Miró, Calder, Magritte, Braque, Gris, Mondrian, Tanguy, Masson and others who represented the greatest surge and variety of individuality in mental experience that the world has ever plumbed the depths of in a consciousness of aesthetic purpose; in such art we have the permanent record of the processes and results of them to help us differentiate types of mentalities that represent the type we are each and the value of the total range of human expression in one convention of communication.27

The Photogram (haunting photography)

As photographic trace or impression, the index seems to harbor a fullness, an excessiveness of detail that is always supplemental to meaning or intention. Yet the index as deixis [or pointer] implies an emptiness,

‘The index asserts nothing; it only says “There!”

– CHARLES SANDERS PEIRCE 28

a hollowness that can only be filled in specific, contingent, always mutating situations. It is this dialectic of the empty and the full that lends the index an eeriness or uncanniness, not associated with the realms of the icon or symbol. –

MARY ANN DOANE 29So far I have oversimplified the account of how these photograms were made. There are two, three, sometimes four portraits of each subject. In most cases an original photogram was placed face down on a new sheet of paper, the exposure repeated and developed so as to produce a negative of the first image, with the black and white areas changing place. Thus, we have a ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ photogram of most but not all of the portrait subjects.30 Secondly, the process was repeated, sometimes more than once, with the superimposition of objects, such as the tools that encircle Alfred Bishop’s head, or of inscription; drawing in Miró’s case, handwritten poetry in Auden’s. The O’Keeffe works involve a double positive/negative exchange. On the back of some photograms, Lye has recorded their technical history. (Trick? Pigtails ) for example: ‘60w on off sharp= + -, for face, lily, curves, then, on same paper, put reverse & expose again – 500w on off sharp= +++-- .’ In some cases (W. H. Auden, Althea) there has been more than one original. From the photograms in the Collection it is not possible to construct a standard ‘set’ for each portrait subject so it is difficult to say whether there is one ‘finished’ photogram (say a head accompanied by objects) preceded by one or more ‘studies’, or whether each is to be regarded as a work in its own right.

The selected added images derived from the superimpositions take the place of the photograph’s random excess of detail. Images ordinarily have more than one sign function. All these additions are indexical;

the signatures of Miró and Auden are symbols but they are also doubly indexical; as traces of the hand that wrote, and of the individual whom signatures name. They serve to further characterize or categorize their subjects. Gender distinctions are reinforced, the female subjects are further feminized by their adornments (string of pearls: Ann Lye; lace and tulle fascinator: Jean Dalrymple) or by associations with the natural (flowers and leaves: Althea, Georgia O’Keeffe).31 The sections of precision metal mesh that overlay Le Corbusier’s head and Albert Bishop’s are perhaps the male equivalents of the women’s netting veils and lace mats. W. H. Auden, Miró and Le Corbusier are categorized in terms of the arts they practice.

The effectiveness of Lye’s portraits as models of modern mentality relies not on their likeness to their subjects, not on a knowledge of human biology, perhaps partly on our knowledge of the achievements of their subjects as artists, poets or whatever, but mainly on their affect as photograms. And, as we have said, that affect stems from the photogram’s indexicality and its difference from the photograph. The eeriness of the dialectic of the empty and the full is far greater in the photogram because it harbours far less and far different iconic detail while at the same time – because this is a portrait – requiring far more of what detail it does possess. The photogram puts aside our daylight expectations, offering instead a subject that looks the other way, that won’t face us as if to compel us to take its greater indexical weight seriously. A subject secreted behind nets or meshes and bathed in an estranging nocturnal light. Photography’s perspectival space is replaced by an infinitely graduated apparently shallow space, mostly concentrated near the interior margins of the profile, one which is as vivid a visualization of eeriness as you could ask for. In its proximity to the

paper, the face and head displace the darkness and in the process render it, rather than their features, more palpable. In Ann Lye’s portrait we see the light of this displaced darkness, rather than the side of her face and the string of pearls resting beneath it. The photograms of W. H. Auden portray a head whose profile seems intently following its own gaze far into the deep background space as well as one reduced to a lump of protoplasmic palpability whose intense glow illuminates but also burns into illegibility several lines of his poetry. We want to say that they succeed equally as portraits. As itself a model of modern mentality the photogram is designed to reorganize the way we look so we may perceive psychological depth as the direct trace of the subject’s face and head – in a ‘flash point instant.’

WYSTAN CURNOW is an Emeritus Professor of the University of Auckland, founding trustee of the Len Lye Foundation and a well-known art critic and historian.

1 This essay was originally published in Len Lye, Tyler Cann and Wystan Curnow [eds.], Govett-Brewster Art Gallery and Len Lye Foundation, 2009. It is reprinted here with minor revisions.

2 Branka Stipancic, ‘Mangelos from 1 to 9 ½. No art.’ In Mangelos nos. 1 to 9 ½, Porto, Fundacao de Serralves, 2003, p.14.

3 Laura Hoptman, ‘No time like the present: Mangelos’s no art then and now,’ ibid., p.35.

4 The credit for their ‘discovery’ goes to René Block, who’s Toi Toi Toi, Three Generations of Art from New Zealand, Museum Fredericanium, Kassel, 1999 included 24 photograms. [ed.] A selection were exhibited in the exhibition Len Lye at the Watershed Gallery, Bristol in 1987.

5 Judy Annear. ‘Len Lye – Free Radical’ in Len Lye, Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2001. Although Annear’s title suggests otherwise, her excellent essay is mostly concerned with the photograms, 21 of which were included in her exhibition. Roger Horrocks’, Len Lye: A Biography, Auckland, Auckland University Press, 2001, p.236-7, is as ever the indispensable starting point on the subject.

6 A draft of this essay was given as a seminar presentation to the University of Auckland English Department in 2007; several people have made suggestions

from which I have benefitted, in particular my colleague, Dr. Lee Wallace, and my son, Ben Curnow.

7 László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion, Chicago, Paul Theobald, 1947, p.188.

8 See Horrocks, pp.104-5.

9 The catalogue accompanying the International Surrealist Exhibition erroneously lists three works by Lye: the painting Jam Session and the photograms SelfPlanting at Night and Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden. Photographic documentation of the exhibition held in the Roland Penrose archive at the National Gallery of Scotland indicates a substitution of works. The exhibition included the following by Lye: King of Plants Meet’s First Man (painting) and the photograms Self-Planting at Night and Watershed.

10 See www.photogram.org. In 1960-1, Yves Klein made his ‘anthropometry paintings’ by having nude female ‘models’ to use themselves as paintbrushes. Negative images were also made, by spray painting around their bodies. As these produced silhouettes and the paint was always blue they resemble the blueprints of early photograms. Although Klein’s intentions in these works were in some respects very different from Lye’s, the interest in indexical trace of the body is clearly comparable. See Untitled Anthropometry(ANT 63), 1961, and Hiroshima (ANT79), c.1961.

11 Silhouetted heads are found in the work of György Kepes and Arthur Siegel, for example, but neither can be called portraits.

12 C.S. Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Charles Hartshorne and Paul Weiss [eds.] Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1931, vol. 2, p. 81.

13 Mary Ann Doane, ‘The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity,’ Differences, Vol.18, 1, p.135.

14 Annear, p.18

15 Lockwood directed the Shell Film Unit’s first film, Airport (1934) a documentary on Croydon airport, at the time London’s main airport. In 1936 the Unit engaged Lye to direct The Birth of the Robot. Lockwood’s Jamboree, 1957, was the first rock ‘n’ roll movie.

16 Richter is perhaps the exception. Lye had met Richter (and probably Auden) in London, since he, like Lye, had worked with John Grierson at the GPO and Realist Film Units. Auden had moved into Greenwich Village at the same time as Lye. Stanley William Hayter was another London contact. He had moved his print studio, Atelier 17, from Paris to East 8th Street in the Village in 1940. It was through Ruthven Todd, an English writer who took Joan Miró to Hayter’s studio to work on prints, that Lye met the Spanish artist, and it is likely the studio was the point of contact with Le Corbusier, who also made prints there during his New York sojourn. The Miró photogram is dated in the painter’s hand May 15, 1947; a Miró etching and acquatint from the Ruthven Todd album inscribed epreuve d’essai par Hayter, and dated May 2, 1947 was on the market at the time of writing.

17 Lye, who directed a March of Time feature on New York nightclubs (1946) was a friend of Fred Ramsey, whose book Jazzmen (1939) did much to revive interest in and knowledge of New Orleans jazz. One of those middle-class enthusiasts was the poet William Carlos Williams, whose ‘Ol’ Bunk’s Band,’ famously puts Baby Dodds’ drumming to words. In 1945 through 1947 Lye regularly went dancing with friends at the Stuyvesant Casino, where Dodds was playing with resident Bunk Johnson’s band, and Eddie Condon’s.

18 Len Lye, ‘Notes 2 (Empathy),’ unpublished mss., c. 1946, Len Lye Foundation Archives, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre.

19 Ames had published papers, such as, ‘Early individual differences in visual and motor behaviour: a comparative study of two normal infants by means of cinemanalysis.’ Journal of Genetic Psychology, 1944, 65, 219–226, and collaborated with Arnold Gesell and Frances Ilg, in such influential books as The Child from Five to Ten, Harper & Brother, New York, 1946. In 1950 she was co-founder and director of the Gesell Institute of Human Development.

20 (See Horrocks, pp.213-14). In 1946 he applied (unsuccessfully) for research grants from the Viking Fund and the Guggenheim Foundation.

21 Nina Bull, in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 103, No. 4 (April, 1946), p.334.

22 Len Lye, Untitled Mss., c. 1946, Len Lye Foundation Archives, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre.

23 Ibid.

24 ‘Neurons, Attitudes, Images,’ Mss, c.1946. My discussion of Lye’s often fraught intellectual conversation with Bull is selective. Besides his concern about imagery, he found her references to emotion too abstract. Following on from the various Mss from which I am quoting, Lye embarked on ‘Shoe of My Mind’ late in 1946, and it was most likely he was still working on it at the time of the photograms. This manuscript is an attempt to re-cast Bull’s theory into a sequence of poetic prose narratives. See also my ‘Len Lye and Abstract Expressionism,’ in Len Lye, eds. Jean -Michel Bouhours and Roger Horrocks, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2000, p.207, where I discuss the relation of Lye’s physiological unconscious to that outlined in poet, Charles Olson’s Proprioception essay.

25 Lye, ‘Notes 2 (Empathy),’ (see note 16).

26 Edmund Sinnott, Yale Review, 1, 1945.

27 Len Lye, Untitled mss., 1946, Len Lye Foundation Archives, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Centre.

28 Peirce, Collected Papers, vol 3., p. 361.

29 Mary Ann Doane, ‘Indexicality: Trace and Sign,’ Differences, Vol. 18, No.1, (2006), p.2.

30 There are no negatives for Ann Lye, or Baby Dodds, but two positives of him, one on matt, the other gloss paper. There is no original for Joan Miró, but there are three with different superimpositions. Nor is there an original for W. H. Auden, but those with superimpositions are based on two different originals.

31 According to Louise Bates Ames, Caitlin Thomas described Ann Lye as ‘tough as blue jeans and as beautiful as pearls. Obituaries claim Jean Dalrymple was ‘the most beautiful woman in the world in her day.’

Judy Annear [ed.], Len Lye, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001.

Geoffrey Batchen [ed.], Shadowgraphs: Photographic Portraits by Len Lye, Adam Art Gallery, Wellington, 2011

Geoffrey Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, Prestel, New York, 2016

Paul Brobbel [ed.], Len Lye: The New Yorker, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, 2012

Gregory Burke and Tyler Cann [eds.], Motion Sketch, The Drawing Center, New York, 2013

Tyler Cann, Individual Happiness Now, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, 2005

Roger Horrocks, Len Lye, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 2001 / 2015

Len Lye Shadowgraphs

Edited: Paul Brobbel

Design: Kalee Jackson

Photography: Bryan James, Derek Hughes

Editorial assistance: Sarah Wall

Published by Govett-Brewster Art Gallery on the occasion of the exhibition

Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph

29 April 2016 – 14 August 2016

Curated by Geoffrey Batchen Commissioned by Simon Rees, Director

© 2016 Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, the artist and writers

Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this catalogue may be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher.

All works courtesy of Len Lye Foundation Collection and Archive, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre

Govett-Brewster Art Gallery / Len Lye Centre

42 Queen Street

Private Bag 2025

New Plymouth 4342

Aotearoa New Zealand

www.govettbrewster.com

ISBN 978-0-908848-83-6

Printer: Crucial Colour

Principal funder: Organisation Partner:

cover images:

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1947

430 x 350mm (approx)