4 minute read

ON THE RISE

CODING CERAMICS

An early practitioner in the world of 3D-printed ceramics, Brian Peters is scaling his work to an architectural level, while retaining the elegant nuances of working with clay.

By Jen Woo

EVERY PART OF ARCHITECT BRIAN PETERS’ CAREER COMES BACK TO THE LONG, LOW LANDSCAPES OF THE MIDWEST, WHERE GILDED FIELDS OF GRASS BILLOW IN THE WIND. During his teenage years in Michigan, Peters first stumbled into the world of design upon entering the Meyer May House, a Prairie-style residence by Frank Lloyd Wright. His visit to that elegant 1909 home— which exemplifies Wright’s approach of rooting architecture in nature— ignited within him a respect for custom design, as well as a fresh perspective on his hometown of Grand Rapids. Wright’s iconic design would come to influence Peters’ career, which today encompasses architecture and art.

“I was inspired by the level of craftsmanship that went into every detail of the house and how the finishes create a tactile interior experience,” says Peters, who officially launched his namesake studio in Pittsburgh last fall. “Frank Lloyd Wright’s work inspired my interest in studying architectural ornamentation, which led me to study the work of Louis Sullivan when I was living in Chicago, Gaudi and Modernisme when I was in Barcelona, and the Amsterdam School while I was working in the Netherlands. References to this history are embedded in my work today.”

Peters is among just a handful of designers worldwide working »

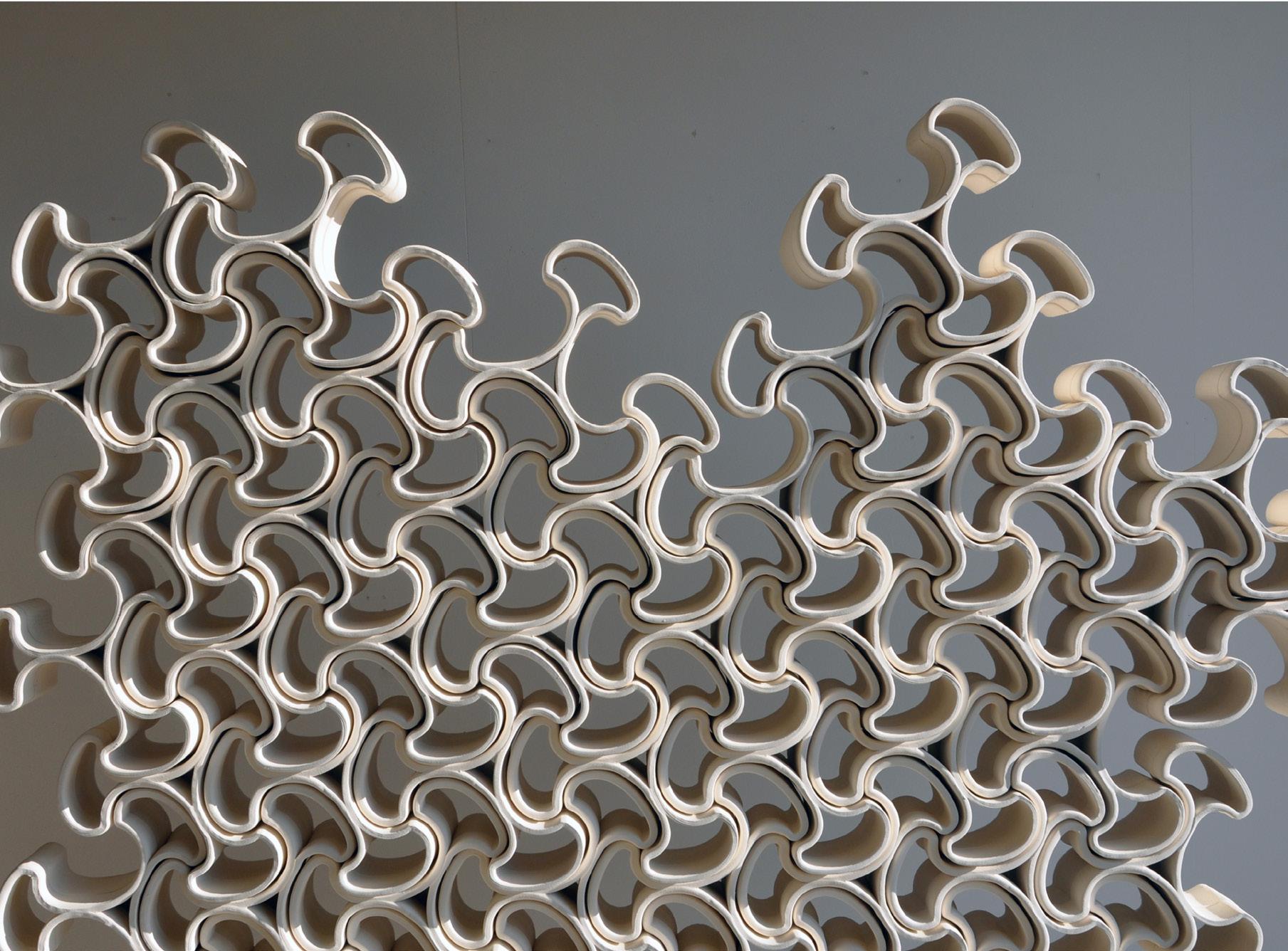

BRIAN PETERS ABOVE: The Carnegie Museum of Art commissioned Brian Peters to create this 3D-printed ceramic screen, titled Aggregation, for its 2019 exhibition Locally Sourced. OPPOSITE: Architect and designer Brian Peters in his studio.

Peters’ Prairie Cord—a site-specific piece that plays with light, shadow, and reflection—was commissioned by the Olbrich Botanical Gardens in Madison, Wisconsin.

FROM TOP: A 3D-printed feature wall that Peters designed for the lobby of the Eighth & Penn development in downtown Pittsburgh. A piece from Peters’ Dyadic series. in 3D-printed ceramics for largescale architectural applications, and his work places him at the intersection of craft and technology. After writing the digital codes for his pieces, he prints them (typically in blocks and tiles), then refines and assembles them by hand, creating intricate sculptures and installations that evince his love of flora with their shapes, patterns, and textures.

In 2011, Peters—who earned a Master of Architecture degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago and a Master of Advanced Architecture degree from the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia in Barcelona—used his process to create something much larger when he collaborated on the 3D Print Canal House project with Amsterdambased DUS Architects. To construct it, he helped develop the world’s first movable 3D-printing pavilion capable of 3D-printing full-scale structures. The following year, he launched his design-and-fabrication concept Building Bytes at Dutch Design Week. Using this awardwinning method, Peters produces bricks with complex or impractical forms for use in architectural applications.

Although he’s able to harness the precision of tech, Peters isn’t seeking perfection. Instead, he’s interested in translating digital code, custombuilt technology, and natural clay into contemporary design. In the past, he used words like “techie” and “startup” to describe his studio; now he embraces a more artistically driven practice, noting in his artist’s statement that “I am fascinated by work that shows evidence of both the artist’s hand and the marks of the tools used.”

Peters elaborates: “I want to show people the power of this new fabrication technique, showcasing its ability to produce complex designs, while contrasting it with traditional ceramic production methods.”

Every large-scale project Peters’ studio takes on is customized, and the maker’s touch is present at each step in the process, from writing the fabrication code to hand-trimming, slip-casting, and glazing the components before they go into the kiln. There is uniformity, and yet each block is unique. Look closely at one of Peters’ structures, no matter the size, and you’ll see fingerprints on the blocks. His work has been shown around the world at institutions including the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pennsylvania and the New Taipei City Yingge Ceramics Museum in Taiwan.

Peters is known for experimenting with pattern tessellation, light, and texture—methods most evident in his Prairie Cord installation at the Olbrich Botanical Gardens in Madison, Wisconsin. Seemingly perched over the surface of a reflecting pool, the ornately latticed, 3D-printed ceramic arc is reflected by the water to form a cylinder that plays with light and shadow by day and night. The installation, in which a series of curves forms an abstract view of the native prairie grass cords, echoes a Frank Lloyd Wright approach to design—nature as the ultimate inspiration—and is a creative nod to Peters’ artistic beginnings. h