T-03 2022

Unsettling Ground: BEYOND THE TERRA NULLIUS

Unsettling Ground: BEYOND THE TERRA NULLIUS

Cover image

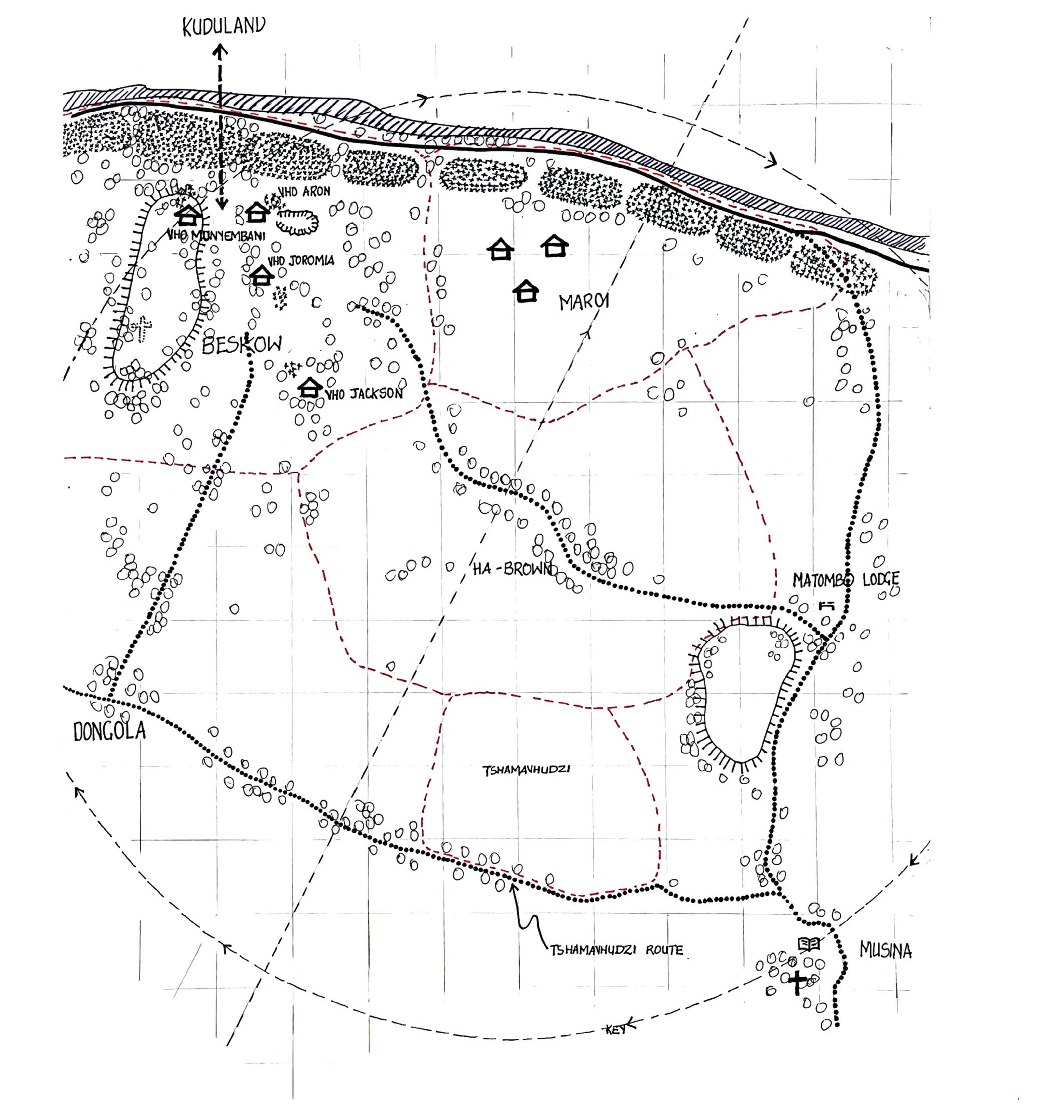

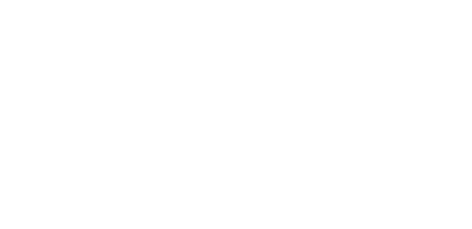

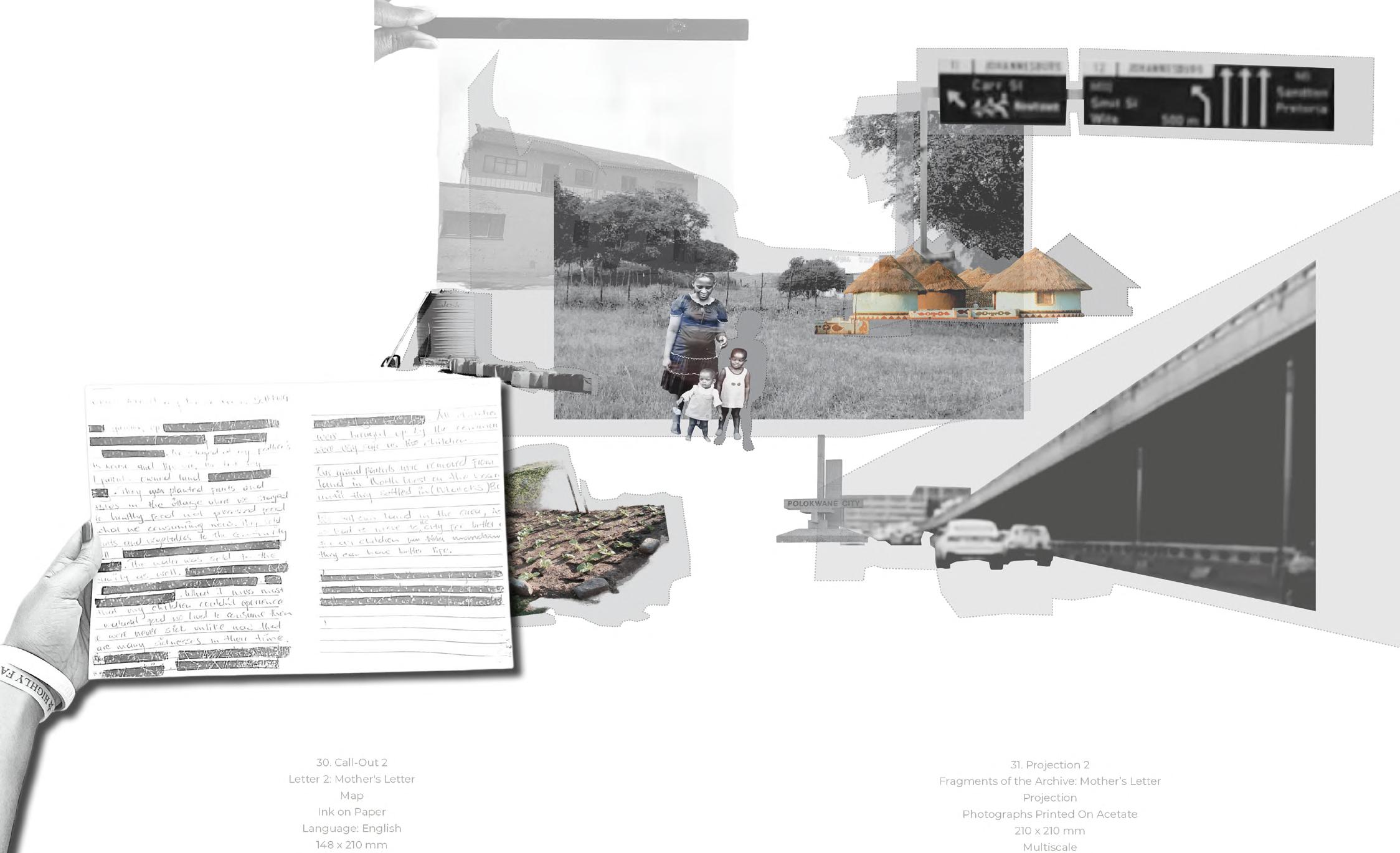

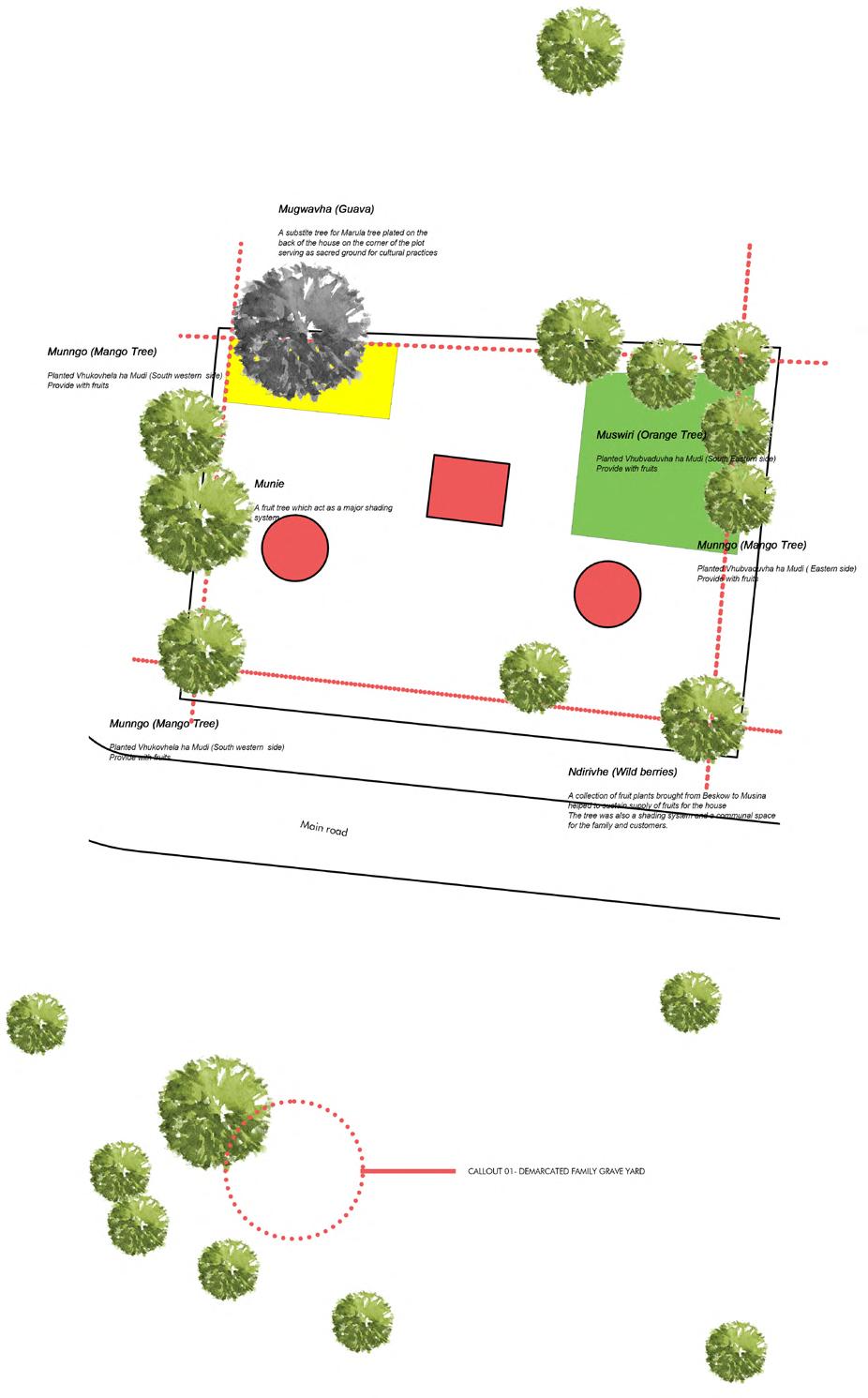

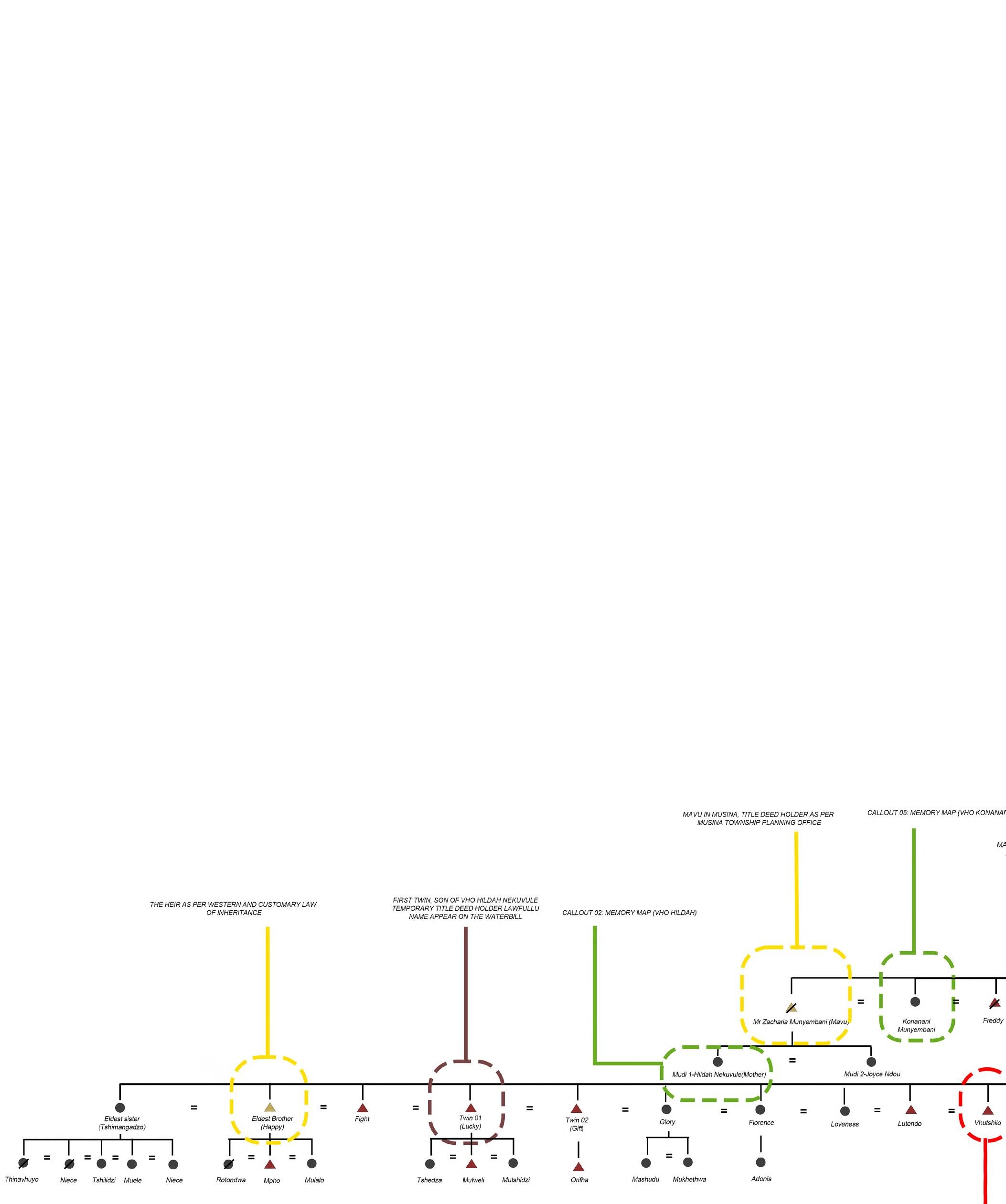

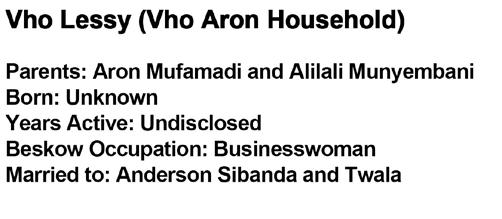

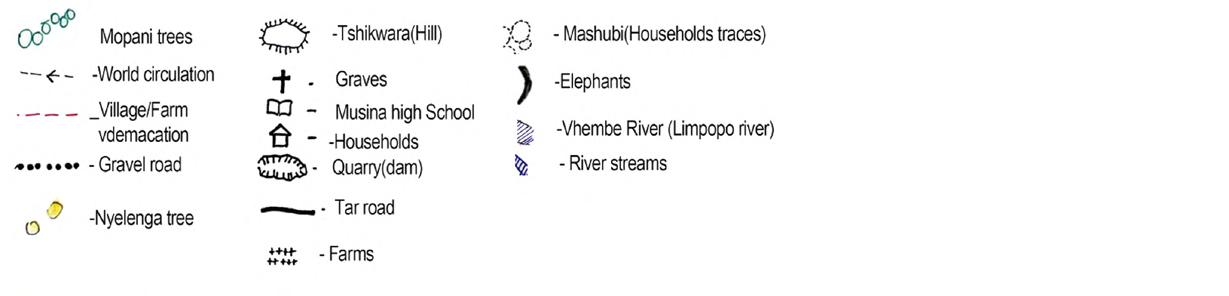

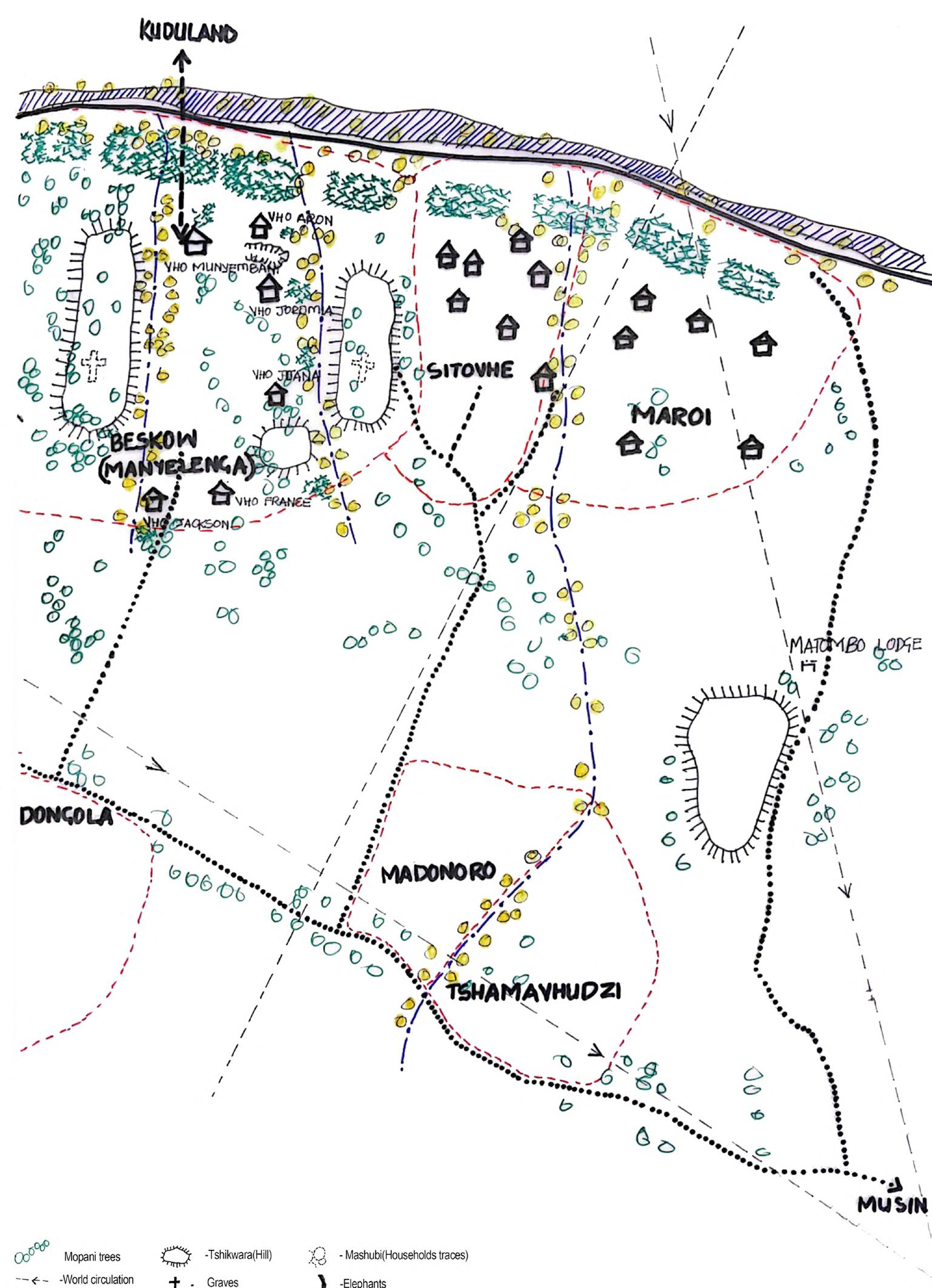

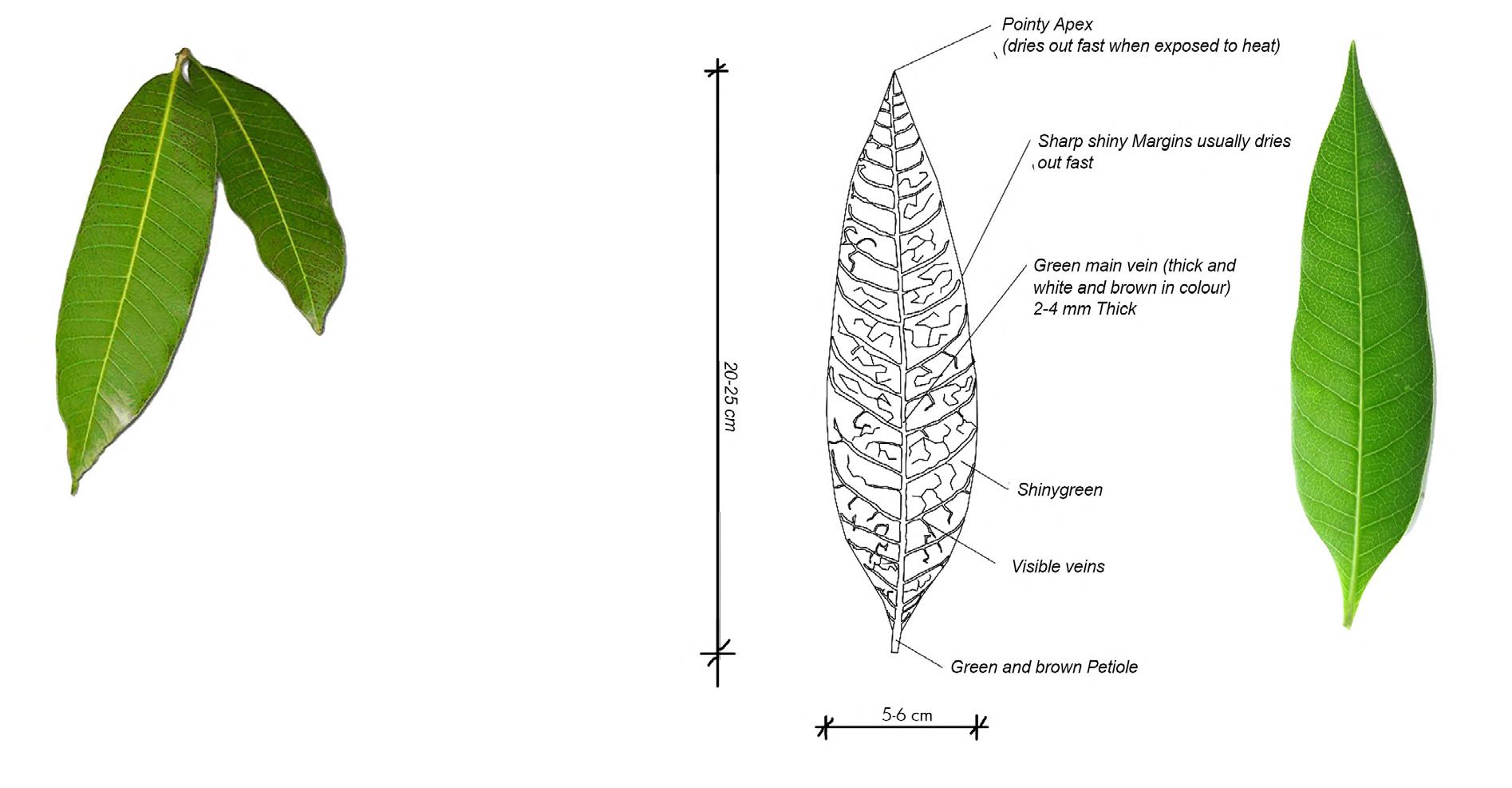

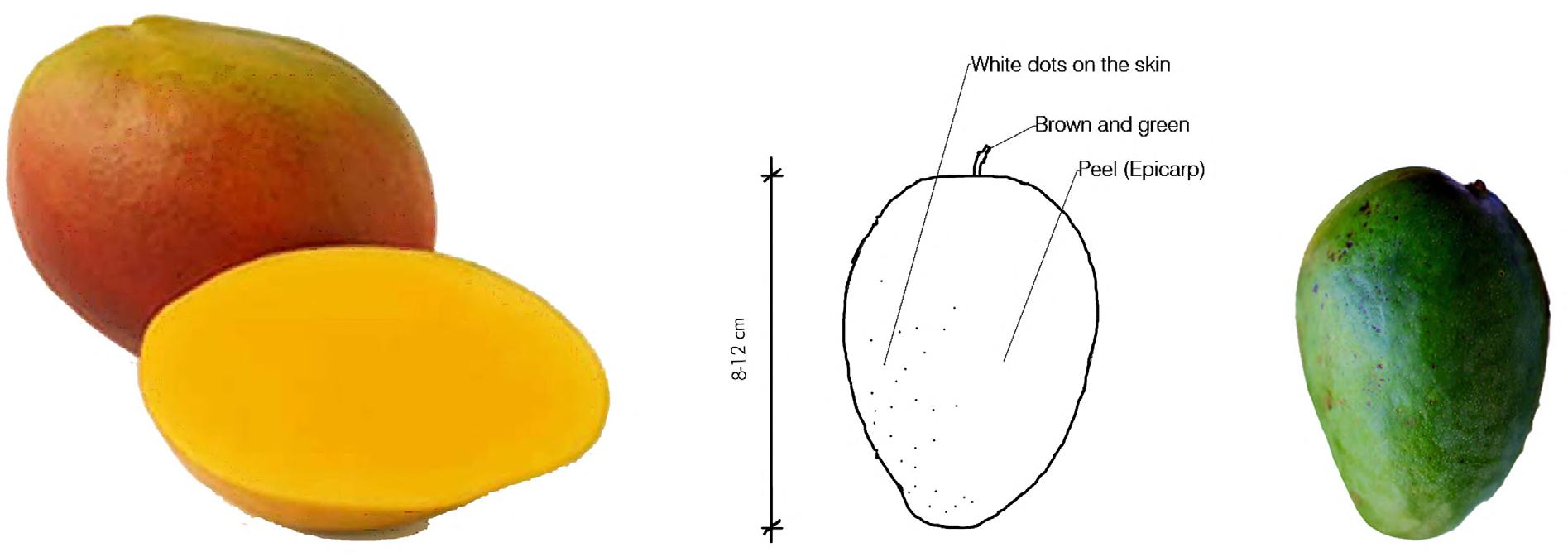

Callout 02: Vho Hildah Nekuvule (Memory Map) by Vhutshilo Munyembane

Published by

Unit 19 of the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) in Johannesburg, South Africa.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the publisher.

Graphic designer

Dustin August of DADA Collective

Editor

Tuliza SindiUnit 19’s oNform T-03

Unsettling Ground: BEYOND THE TERRA NULLIUS

194pgs

19x25cm includes Acknowledgements

Unit 19

Unit System Africa

Graduate School of Architecture (GSA)

Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture (FADA)

University of Johannesburg (UJ)

List of Current Publications

2020:

oNform T-01 (accessible on issuu)

2021:

oNform T-02 (accessible on issuu)

Awards, honours, features & mentions

• saay/yaas collective (of which Tuliza Sindi is a member), who are the curators of the :her(e); otherwise platform, was invited in July 2022 to host an event in Bordeaux, France, within the framework of the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial. You can access the platform here: https://hereotherwise.space/; and the Bordeaux event/offering here: https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=TAiVBM_SDJU&t=2980s&ab_chan nel=arcenr%C3%AAvecentred%27architecture

• In early August 2022, Tuliza Sindi was invited to deliver a school talk as international guest lecturer for Thailand’s International Program in Design and Architecture’s International Lecture Series, Never The Right Time.

• Tuliza Sindi was invited as a librarian at Zimbabwean artist and activist Kudzanai Chiurai’s The Library of Things We Forgot to Remember, in Johannesburg, SA. She brought on room19isaFactory., her cross-

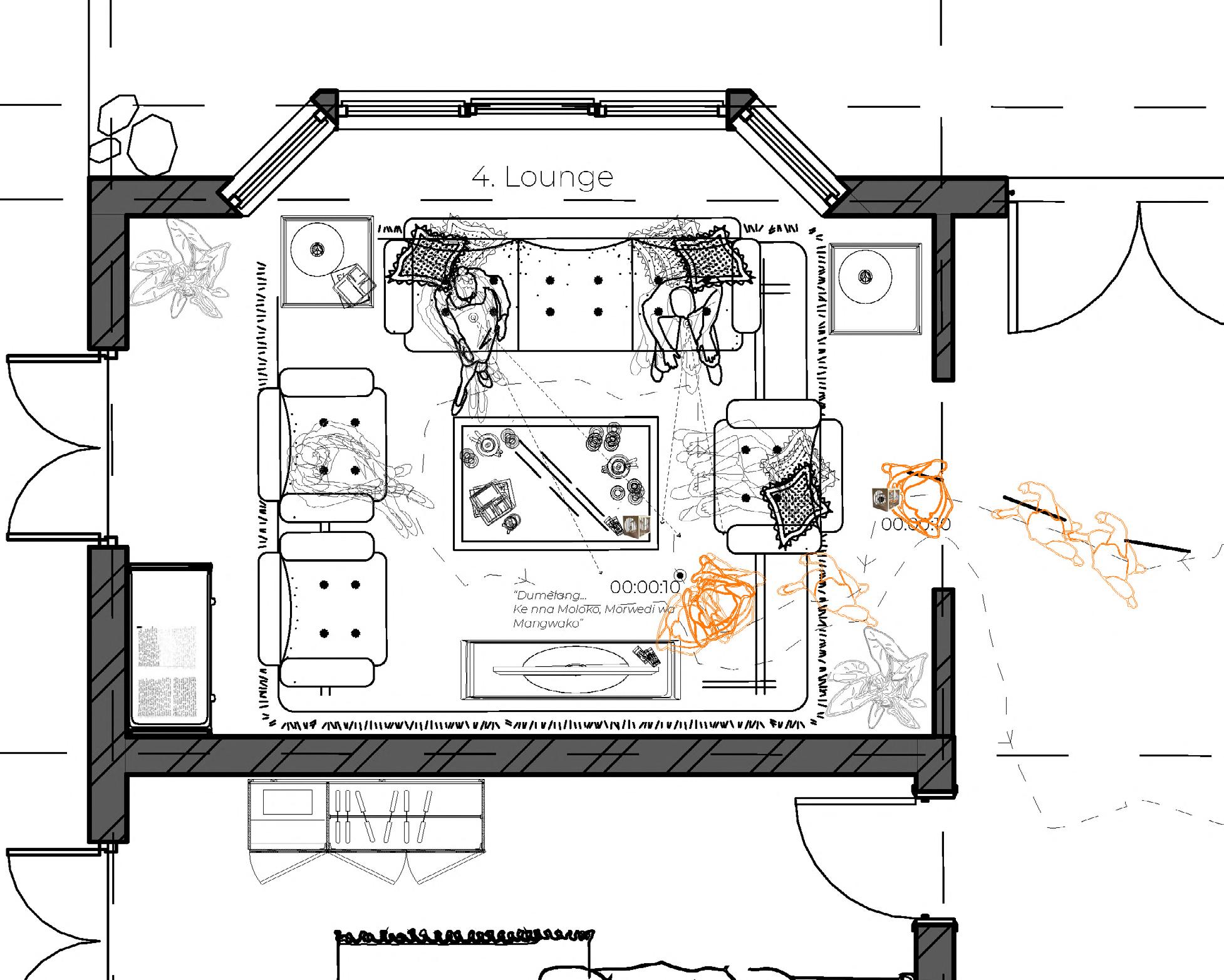

disciplinary architecture collective that she cofounded with Unit 19 alumni Tuki Mbalo, Thandeka Mnguni, and Miliswa Ndziba, to fulfil the brief. The 3-month installation offering, called Lounge(v), opened to the public in September 2022. The installation acted as their backdrop to host US professor of humanities and acclaimed author Tina Campt. The collective will travel with the installation to Berlin in early 2023.

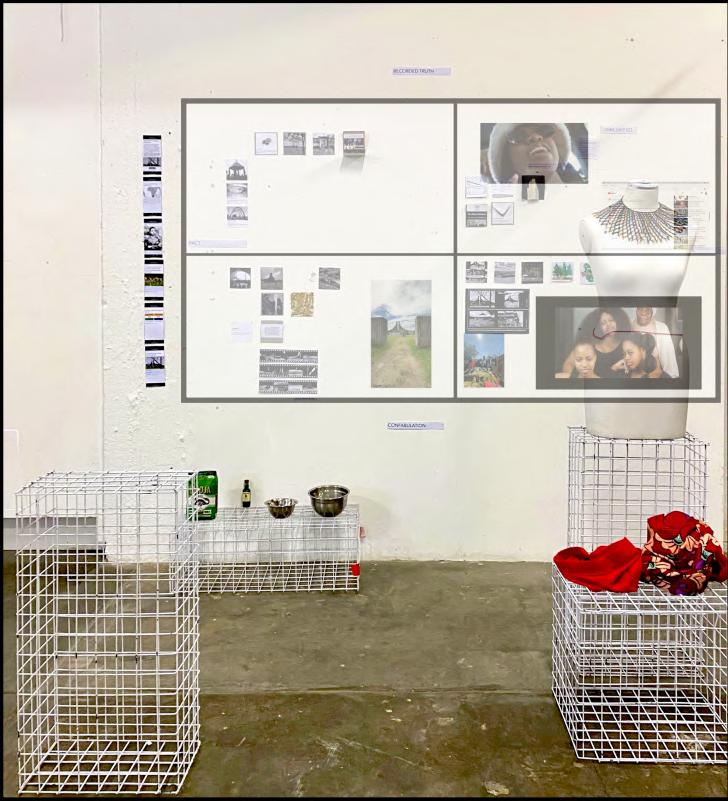

• Tuliza Sindi and Miliswa Ndziba were selected to exhibit their respective research practice works at the FADA Gallery’s annual Creative Research Outputs exhibition. This year’s exhibition, which ran throughout October 2022, was entitled Situated Making.

• The Pratt Institute School of Architecture hosted the Architectural Humanities Research Association (AHRA) Conference in mid-November 2022, entitled Building Ground for Climate Collectivism: Architecture After the Anthropocene. Delegates were made up of an expansive array of thinkers and practitioners who outlined their provocations across four broad themes of inquiry. GSA delegates included Unit 19 leader Tuliza Sindi, and Unit 19 alumni Tshwanelo Kubayi, Miliswa Ndziba, Thandeka Mnguni, and Tuki Mbalo.

• Olive Olusegun’s paper, entitled The Survival of Spaza Shops: Reframing and Redeveloping Informal Trade in South Africa, was selected to represent Unit 19 and the GSA at the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) Annual International Conference to be held in Montreal, Canada in midApril 2023. She will present under the theme Beyond the Mall – Retail Landscapes of the Late Twentieth Century.

• MArch(Prof) Distinctions: Matildah Maboyane; Razeenah Manack; Olive Olusegun

• BArch(Hons) Distinctions: Vhutshilo Munyembane

• Examiner’s Choice - Jeanne Sillett: Olive Olusegun

• Unit Choice: Marilize Higgins

How to reach us

Instagram: @gsa_unit19

Issuu: GSA Unit 19

Youtube: GSA Unit 19

GSA Website: www.gsa.ac.za

Unit 19 website to follow.

© 2022 GSA UJ

All rights reserved.

This

edition of oNform is dedicated to the future of Unit 19, and, to claim it boldly, the future of the architecture discipline: room19isaFactory.

“We intend to harness the scientific potential and creativity of the black world and place it at the disposal of all black states without distinction.”1

- Cheikh Anta DiopOn a hot December’s summer on the streets of Dar Es Salaam, I escape the scorching sun and humidity in a 1966 Bookshop, TPS, on Samora Avenue. Here, I encounter what seems to be a ‘bogazine’, that is a kind of hybrid publication; a cross between a book and magazine, if not at least in my mind. It is called Xibaaru, Teere Yi, April 2018, edition No 13; with a focus on what African writers can learn from Cheikh Anta Diop. Tantalizingly published in West Africa, belatedly distributed, and sold in East Africa for me to find. This simple exchange to this region echos other intellectual exchanges such as that of Unit 19’s leader, Tuliza Sindi, at the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) in Johannesburg, whose East African roots enrich her operations in South Africa, together with her Unit assistants Tshwanelo Kubayi, Miliswa Ndziba, Sarah Treherne, and the students of 2022; who I can comfortably confirm are uniquely unsettling ground, beyond the terra nullius, as the title of their syllabus goes. Without exaggeration in this regard, I consider here their free radical works and the open pedagogical potential of Unit 19, with Cheikh Anta Diop’s body of work in mind. Of reference here being the extracted essays titled The Black Bomb, In the Den of the Alchemist, and A Plausible Future, among the many other essays that venerate his thinking in the Xibaaru publication.

Cheikh (1923-1986) was an anthropologist, physicist, and politician who is described as foundational to the theory of Afrocentricity, and who Carlos Moore described as having “two sides, the scientific side and then the

1 Diallo, M., 2018, Black Bomb, Xibaaru, p 11.

political pan African side who had such a clear vision of the twentieth century and what types of measures were required to secure the welfare of Africa”2. Here too, on an architectural front in consideration of settler colonial states, and specifically South Africa, I see Unit 19 take methodic modes to not only disentangle, but reinscribe a new path to “conjure and catalyse alternate ground philosophies and their accompanying socio-spatial imaginaries” in Africa, as they describe it in their year’s research outline. The ambition set by Unit 19 harkens at least in my mind to an organization Cheikh and a few of his compatriots referred to as the World Black Researchers Association (WBRA). The organization unfortunately fell apart as soon as it was established, scandalized, and disintegrated with an embezzled grant of half a million US dollars. With the many theories of what really happened and who was responsible, what’s sure is that Cheikh’s vision for WBRA, as quoted above at the beginning of my forew[a]rd was generationally stalled, ready for transposition, if not at least with a new force of young minds who will reimagine new forms of being and making on the continent.

It is at this juncture that the potential of Unit 19’s work comes to the fore. Cheikh’s thinking and early works were in the advanced laboratory stage, where he addressed complex territories such as the geopolitically emotive subject of African nations having access to not only nuclear energy but the atomic bomb, a black bomb, as a nexus to secure the future of the African people. Equally known and more celebrated is his vantage point to look at the African origin of civilization from a black Egyptian one, especially in reading it from the vantage point of our homosepien origins, refined if not perfected in his

2 Ibid., p 6.

laboratory at the Institut Fondamental de l’Afrique Noire (IFAN).

It is never easy to create an environment for students to harness the potential of what might be - broadly speaking - referred to as the scientific creativity of the black world, without the tendency to revert to cliched and arguably arbitrary ‘wakanda-esque’ concoctions. What is for sure, is that it starts with how Unit 19 have carved out a safe space of solidarity and communal support where both tutor and student feel free to imagine and play with the rules of engagement and bounds of teaching in the rigor of relearning architecture on the continent of Africa. A place in true African style where a supportive jeer, high five, and hug in-between intensive crits go a long way to make meaningful bonds of trust and vision; bonds that were broken when you trace the weak point of the WBRA.

At the GSA’s International Critic’s Week 2022, I experienced the rumbling groundswell of Unit 19; a kind of connective black thread of graduate scholarly tangents that unpack often static and yet deeply contested colonial and post-colonial territories in need of cultural re-reading and re-imagined reproduction.

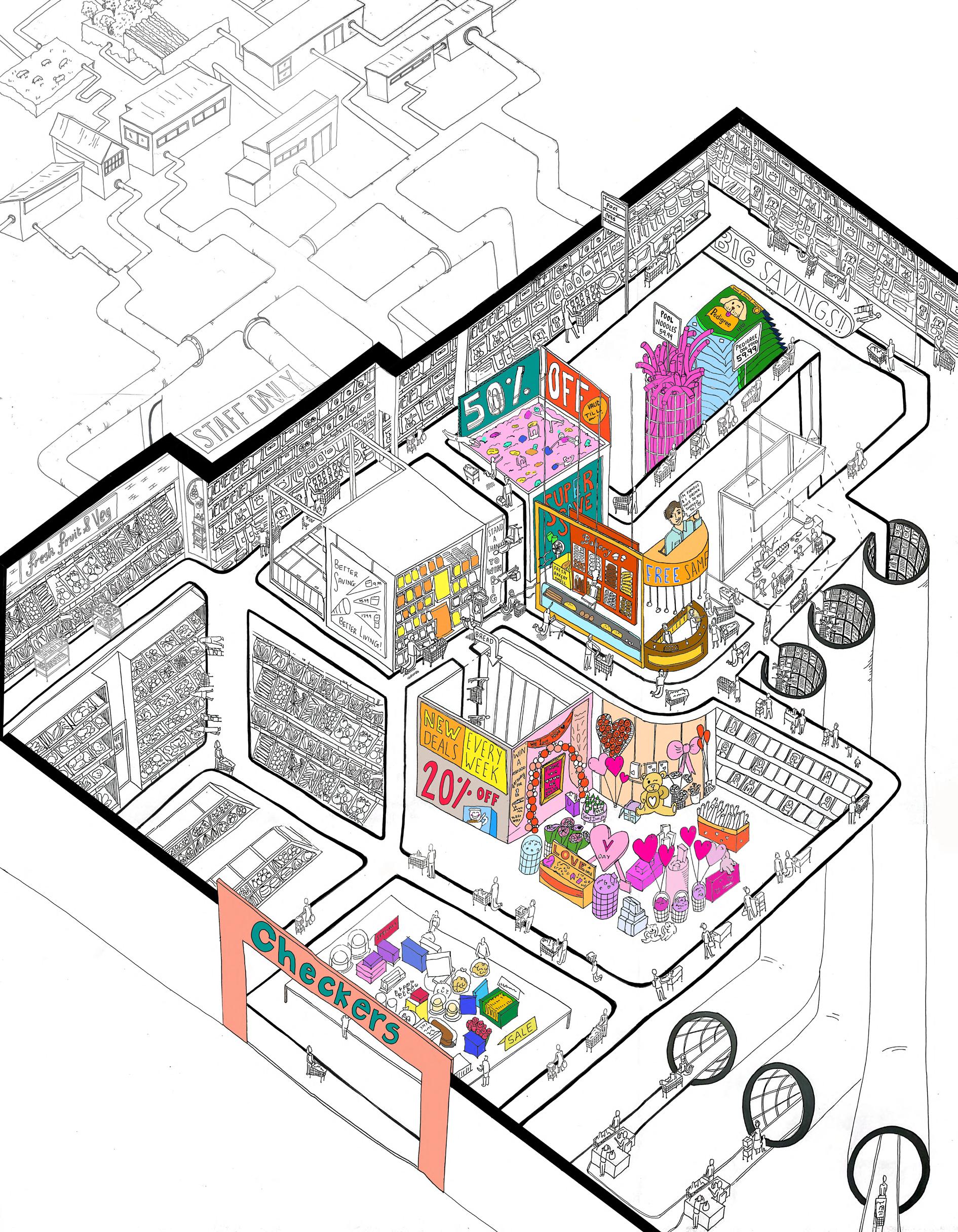

One such encounter was a project where the contemporary and seemingly innocuous workings of a gift shop were reprogrammed and critiqued to harness the discursive potential of both reading and representing the black culture for the discerning and undiscerning tourist. We were beautifully subjected to a new value system of trinkets, postcards, and maps. A project that soon metaphorized into an ambitious satirical reconstitution of the shopping mall infrastructure and its soon-tobe hacked capitalist operations across the immediate surroundings. It soon became apparent to me that it was a real scholarly retail space where I gladly emptied my wallet to take home a piece of this rich black culture.

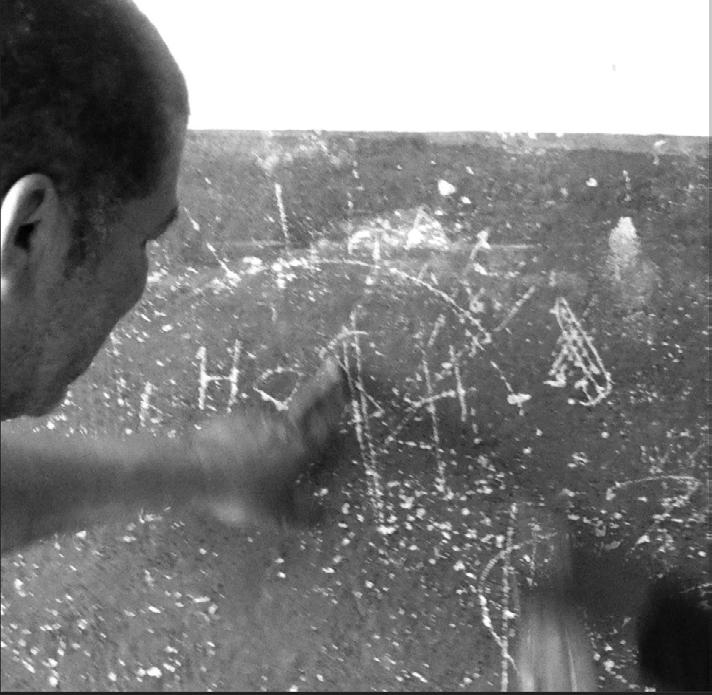

With equal potency was another student’s operationalized art-based works that utilized evidence-based indigenous mapmaking records through the engagement of indigenous women, to trace oral generational land records that can expound and lead to executing current land restitution efforts in South Africa: a new black aesthetic of architectural advocacy where painting, filmmaking, and internal reflection is harnessed in full effect.

Among the many students’ works that you will experience in this year’s compendium, what is evident is that the most seemingly inert territories become the very sites of contested power relations that architecture is seldom in dialogue with. From the bland formation of an act of parliament about waterways, to a seemingly harmless realignment of a city tour, and not forgetting the anatomical journey of a student’s own facial recognition,

as a cipher to a much broader reading of a nation state in flux.

What is for certain is that the works and ambition of Unit 19 has the potential to expand more deliberately in the realm of praxis beyond or as an extension from the academy, as a laboratory on a broader continental scale - a site where half a million US dollars would be the tip of a melting iceberg - since the future of the black world is in re-conception here.

‘The laboratory inevitably conveys mysterious significance, it appears as a cave of sorts, where a (necessarily) solitary genius is pursuing some fantastic goal. To the society at large, the laboratory seems much like the medieval den of an alchemist’3.

3 Diagne, B.S., 2018, In the Den of the Alchemist, Xibaaru, p 11.

Deputy editor of the Architectural Review magazine, Eleanor Beaumont, opened the October 2020 on Land issue with an editorial she entitled uneven ground. In it, she proclaims the following:

Never a blank, flat surface on which to build, even the emptiest site is not empty. The site does not end at the boundary line; long tangled roots of history, ecology, personal stories, extend outwards and backwards through time…Land is the assimilation of countless layers and threads, many man-made, some etched by conflict, capital, ecocide, some buckled or melted under human neglect and abuse. From the smallest act of shifting a stone to the most brutal raising of territories as-yet unbuilt, architecture is part of this accumulation: sprinkled sparsely or bristling in dense tufts, carving the ground into neat squares to be more easily laboured or large parcels to be more easily fortified. Architects build land, not on it (Beaumont, 2020).

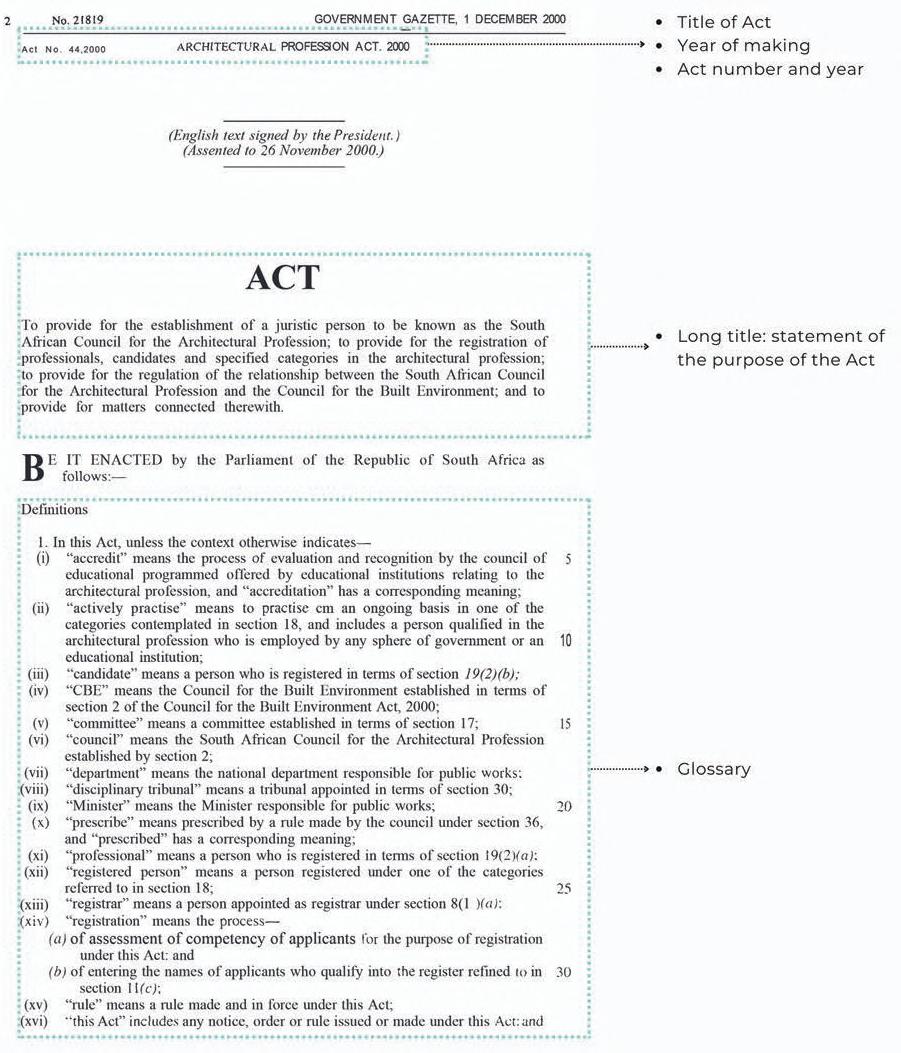

The imposed Architecture profession1, introduced through colonial conquest in territorial regions, hinges on the practice of substituting the natural ground, first ideologically, and then materially as a way to fix ideology in place, allowing ideology’s inherently temporal and fantastical nature to be overridden. This form of spatial practice holds the ground ideologically captive as it renames it with terms that embody capitalist notions such as land, property, site, territory, borders, estate, stock, etc. This vocabulary delimits our spatial imaginings of ground (and hence space, place, home, locality, etc.) within the autopoietic confines of [settler] capitalist conceptions, i.e., currency, ownership, and marketized characterizations of productivity.

The misdiagnosed perception of ‘natives’ as barbaric, illiterate, uncivilized, and other-human (i.e., wretched anthropos2) by colonial settlers was fundamental to the conception of ground-as-land. During British colonial invasion, founder of the British modern political economy, William Petty, established philosophies of improvement and development by conflating the value of land (measured on the basis of its productive capacity in that imposed political economy) with the value of people, to create what UK law professor Brenna Bhandar (2020) refers to as “‘racial regimes of ownership’” (Bhandar, 2020). This meant that any use of the ground that did not bare the hallmarks of individual ownership was deemed firstly, inferior, and secondly, available for appropriation by the superior humans (referred to as humanitas3) who could be trusted to use the ground in a superior economic form. Australian urban planner Mirjana Ristic (2018:34-38) names this practice of land classification and designation ‘spatiocide’, where entire landscapes are targeted (through practices such as the scorched earth policy) to revert it back to empty land (or terra nullius4) by wiping out origin communities (Ristic, 2018:34-38), rendering them trespassers, and offering resettlement

2 Anthropos is a term reserved for a lesser kind of humanity who participate only in empirical knowledge-production, i.e., although they are able to produce knowledge, they were deemed incapable of reflecting upon and criticizing their modus operandi (Sakai, 2010:455).

3 Humanitas is a term that signifies an exceptional kind of humanity capable of engaging in both empirical and transcendental knowledge production (Sakai, 2010:455). This referred to Europeans only as they were seen to be the only ones with this capacity.

4 Terra nullius is a Latin expression meaning “no man’s land” (Terra nullius – Wikipedia, 2021). Mirjana Ristic (2018:34-38) offers a practice-based vocabulary to this spatial classification, and refers to it as ‘spatiocide’, where entire landscapes are targeted with the aim of reverting it back to mere land by wiping out origin communities (Ristic, 2018:34-38).

1 The Architecture profession is to be differentiated from the practice of space-making.and belonging through skewed and punishing systems of taxation5 (The Chimurenga Chronic, 2018:4-5).

The practice of terra nullius-ing is a myth-making endeavour that invents a new origin story for the ground in question by resetting its history, and its notions of time and space. It denies that history measurability (which can be understood map-ability) as it charts a new timeline, or what French-Tunisian geopolitical activist MeryemBahai Arfaoui (2022) labels as ‘political time’ in her THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE article entitled Time and the Colonial State (Arfaoui, 2022). Arfaoui says of political time that:

Because creating political time requires memory, the State produces its own superficial and fictitious accounts by drawing up a linear and causal narrative to make it seem as if history were the product of a progression of moments. The State then denies any role in this construction and defers to an essentially tautological referential: it is because it is (Arfaoui, 2022).

Such linear constructions of time (or the Western chronopolitical6 imagination) transforms “history into nature”7 (Barthes and Lavers, 1972:128, 130),

5 From the nineteenth century onwards, colonial forces in Africa made efforts to ensure that people stayed in the same place. They had a difficult time accomplishing this because many indigenous groups in pre-colonial Africa were constantly on the move through transhumance modes of living, remaining aligned to the cycles of the seasons. In efforts to ‘capture’ indigenous groups, borders that limit transhumance mobility was enforced, and those borders in turn, delineated territories that could now define trespassers and trespassing, which could help make the case for legitimizing the use of force, and ultimately, taxation if desiring access to the territories again. “People who do not have an address cannot be taxed” (The Chimurenga Chronic, 2018).

6 “Colonization imposes definitions of time across space or the domination of time through the appropriation of space. The imposition of the capitalist-State as the ultimate form of social organization creates a standard temporal referential (modernity) whose main functions are to normalize the negation of any other social temporality and to establish State dominion over any other social structure. On the world map, we can observe how time zones require all of humanity to live at the same rhythm of ‘progress’. These lines are also borders. Political time is created and ordered by State authorities that declare itself as the norm. To define political time, the State must describe itself as timeless such that without the State there is no temporality: nothing exists before the State nor beyond it. In this construction of political time, the State centres itself as the defining, dominant, authority of time-space. One main function of the State is to name and to govern. It does this by systematically determining what is and differentiating it from what is not. To do this, the State needs a nomenclature system. Law is the language of the State. It is used to define political time by establishing a system of measurement. Therefore, in the same way that there is a ‘geopolitics’ aimed at analysing power over territories, it is essential to acknowledge a ‘chronopolitics’, which analyses power over temporalities” (Arfaoui, 2022).

7 “We reach here the very principle of myth: it transforms history into nature. What causes mythical speech to be uttered is perfectly explicit, but it is immediately frozen into something natural; it is not read as a motive, but as a reason…What allows the reader to consume myth

which is fundamental to the production of seemingly objective realities/futures, as they prescribe definition8 , directionality9, measurability10, and inevitability11 in spatial practice. Definitionally bordering time in that way imposes rhythms and social formations that enforce a universal rhythm of ‘progress’ through a hegemonic temporality that renders time and space fixed and chronological. This negating fixity positions all other realities and their corresponding futures as immeasurable, and hence, a spatial fiction. The chronopolitical practice of spacemaking is designed to manufacture a vulnerability to being denied history and removed from the timeline of civilization (Phillips, 2022) for those not tethered to the grounds they inhabit. Through invented mechanisms such as legal instruments like passports, visas, and title deeds, the law is made to operate as a metronome that regulates hegemonic temporalities, and through Architecture12, these latent legal rules are ritualized to

innocently is that he does not see it as a semiological system but as an inductive one. Where there is only an equivalence, he sees a kind of causal process: the signifier and the signified have, in his eyes, a natural relationship. This confusion can be expressed otherwise: any semiological system is a system of values; now the myth-consumer takes the signification for a system of facts: myth is read as a factual system, whereas it is but a semiological system (Barthes and Lavers, 1972:128, 130).

8 The name and meaning of things, and the meaning of ‘future(s)’.

9 The meaning of progress, primitive, forward-thinking and innovative, ahead, and backwards.

10 Who and what can be catalogued and counted, weighed and evidenced? Who and what have tools of measure, and who and what is immeasurable through existing tools?

11 What is nature and what is natural?

12 To make the distinction between ‘Architecture’ and ‘architecture’, ‘architecture’ – as outlined by Unit 19 recurring critic in the context of the Unit, Anesu Chigariro (2021) – refers to spatial practices “whose lines of inquiry may appear to ask more philosophical, or sociological questions than what can be understood as Architecture [proper]” (Chigariro in Sindi, 2021: v). Such inquiries offer up decolonial moves towards freedom, as it grapples with how transgressive architectural practices can be promulgated through its space as a ‘liberated zone’ within Architecture (liberated zones were sites during African nationalist liberation struggles that were wrested from the control of colonialist settlers in places like Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Namibia, and Guinea- Bissau, where insurgents would form communities from which to recoup, organise, plan, and launch further attacks). Beyond the spectre of the colonial futures presenced through the work of Architecture – that has participated in enforcing, reinforcing and continues to mark the ways in which racialised, gendered and classed oppression operates in South Africa, and throughout the rest of the Africas (Ann Daramola formulates the Africas as a term to reckon, more incisively, with the totality and multiplicities of the continent of Africa, which is often flattened and denuded of variegation. Daramola posits the Africas, the Americas and the Asias as terms that “evoke the multiple”) – there exists otherwise architectures (I borrow the articulation of the ‘otherwise’ from Keguro Macharia’s thinking on ‘otherwise vernaculars’ as presented in Otherwise Vernaculars: A Meditation on 9 July 2021 for the University of Minnesota Department of English). These otherwise architectures are not concerned primarily with negating Architecture; they exist outside its orbit. They form new trajectories of thought that are free from its gravitational pull, resisting Architecture’s place as the centre of the planetary system. They begin by setting a new pace and course for their revolution[s], establishing relations with each other that constitute a new universe entirely, governed by laws that defy

infiltrate our everyday collective behaviours until they become behavioural reflexes. On this basis, Architecture can be said to function as the material manifestation of the rules/laws of conquest, to maintain the trauma of its orchestrated spatiotemporal anachronism.

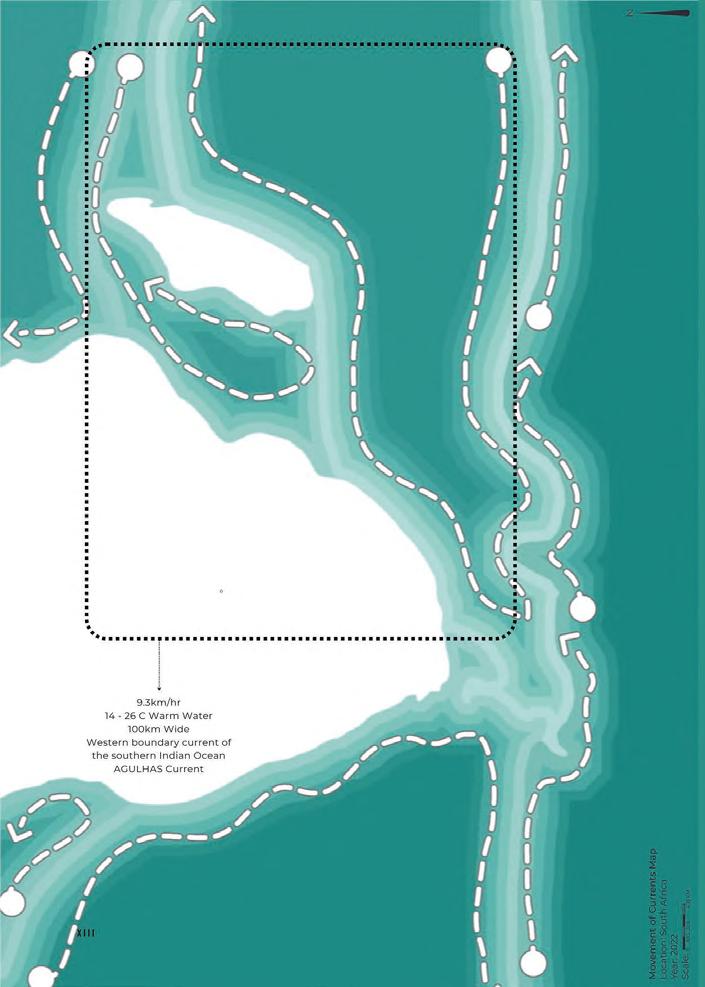

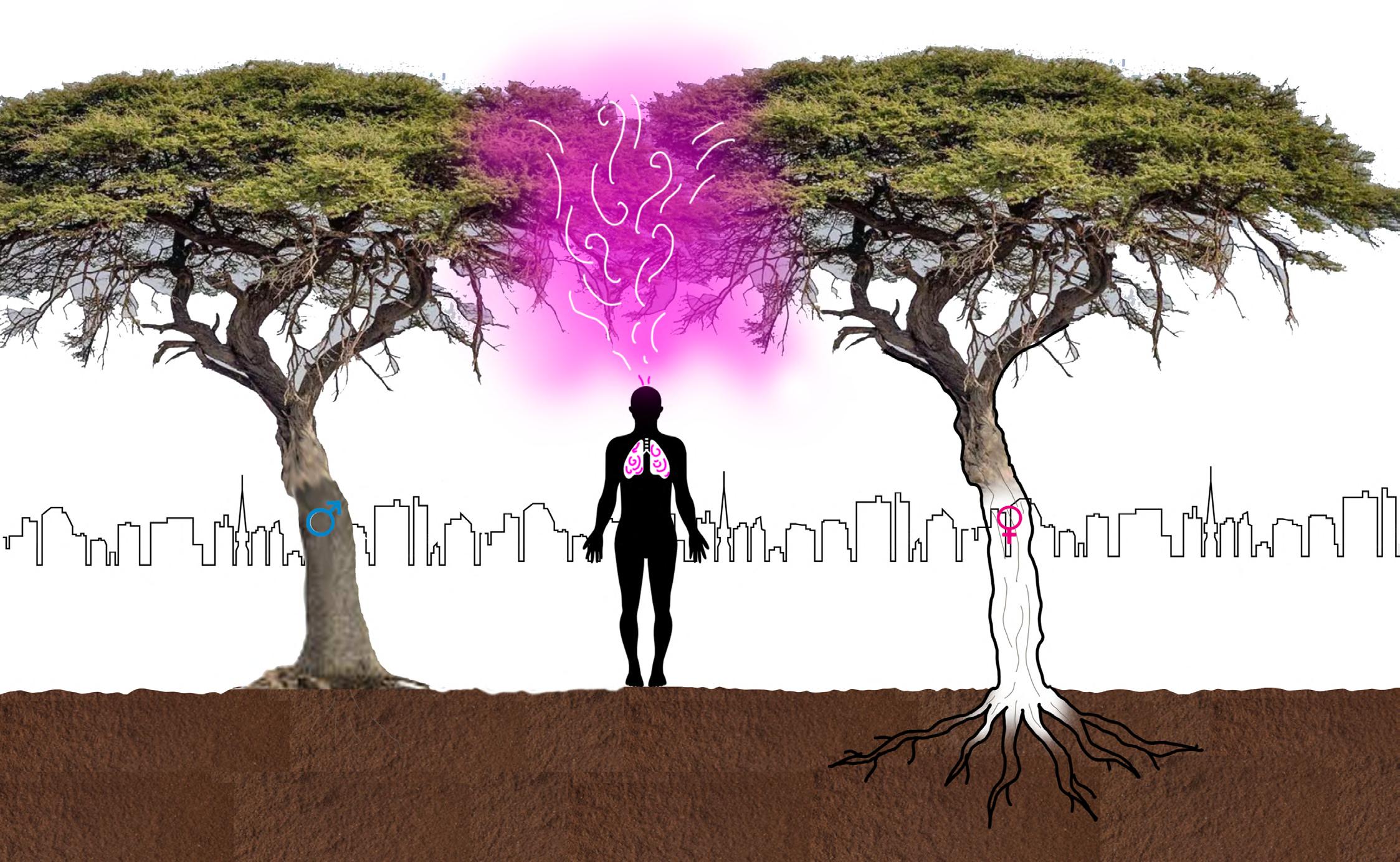

The belief and treatment of the ground as land was designed to be a fundamentally dehumanizing practice, one that enacts socio-cultural crises and collapse of alternate knowledge systems, wisdoms, sciences, and futures. Such critical wisdoms are now being honoured by bodies such as the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as necessary and urgent knowledge frameworks to restore and preserve for renewed use. UNESCO highlights the ingenuity of first peoples, who practiced a social order of preservation known as transhumance, which can be understood as a mobile village that occupies varying grounds seasonally. Grazing would happen inland during the summer months, while they would occupy the coasts in the winter months to exploit marine resources (Apollonio, 1998). UNESCO says of such synergized wisdom that

“indigenous knowledge operates at a much finer spatial and temporal scale than science and includes understandings of how to cope with and adapt to environmental variability and trends” (UNESCO, unknown).

The synergy between the spatial systems that indigenous peoples built to food (plants and animals), natural medicines, and seasonal cycles, and their unmatched sustainable and scalable systems (i.e., operating food systems at the scales of forests, rather than the smaller and less sustainable scales of farms, for instance) have been documented to have lasted millennia, in relation to our young, centuries-old collapsing modern systems and societies. Indigenous knowledge systems are proving critical to introduce as philosophies through which to approach space-making, and to understand land as ground once more requires engagement with such threatened philosophies.

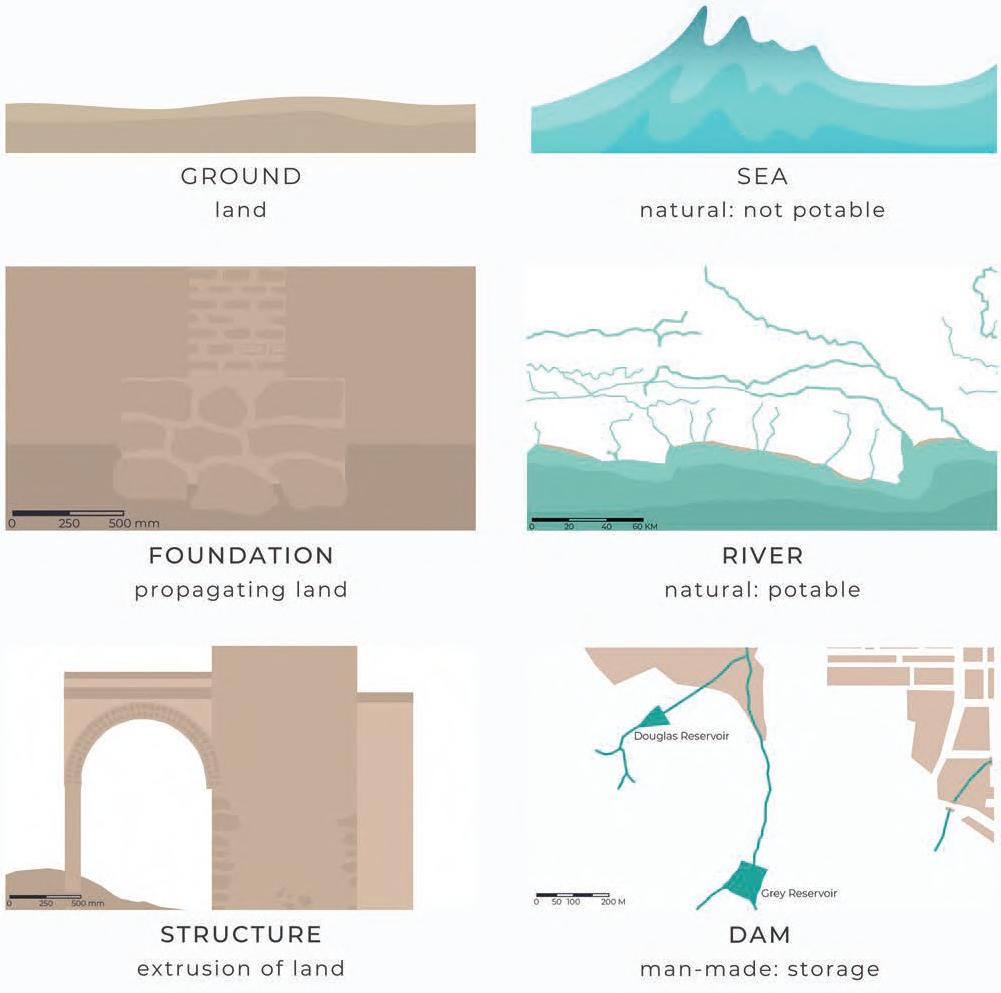

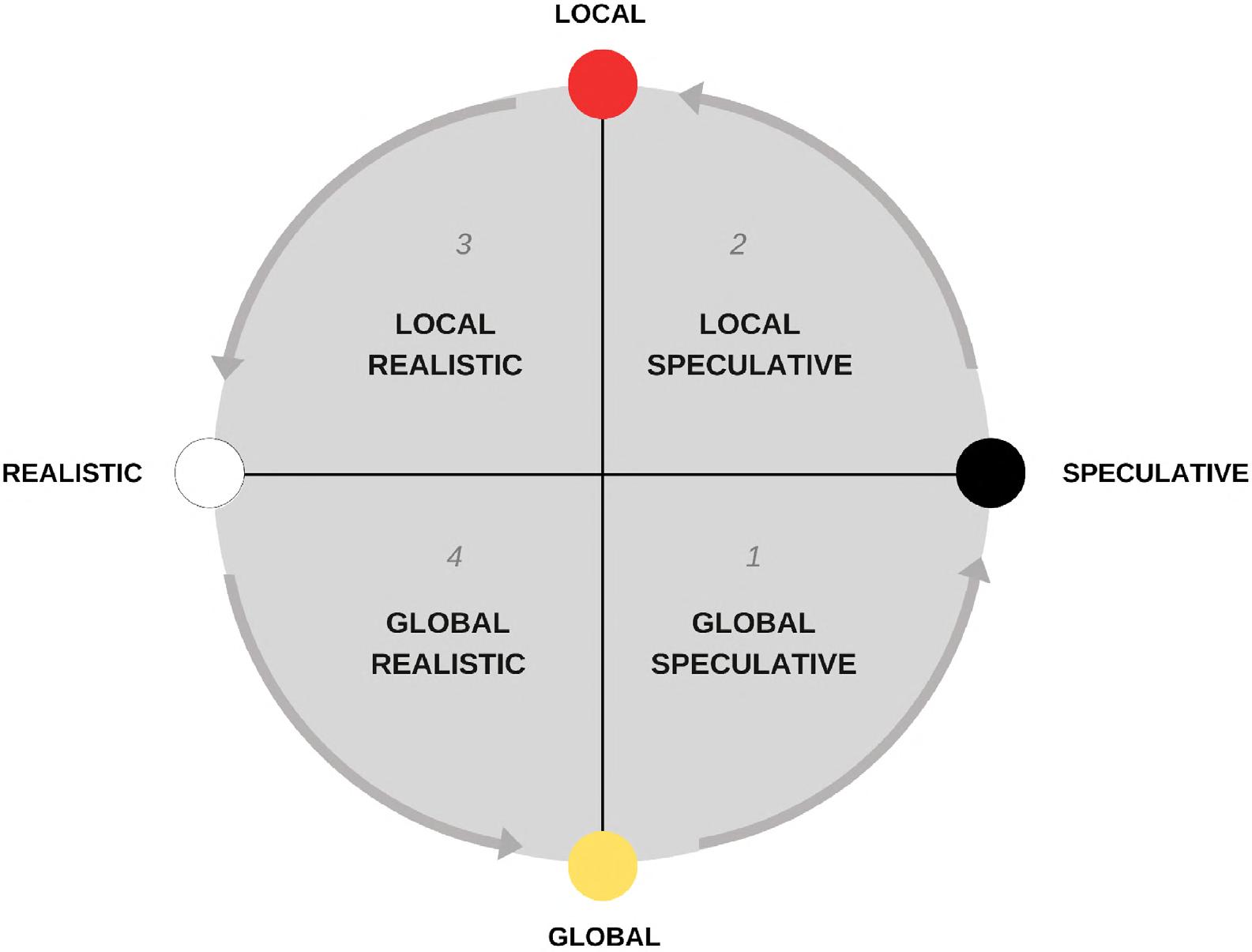

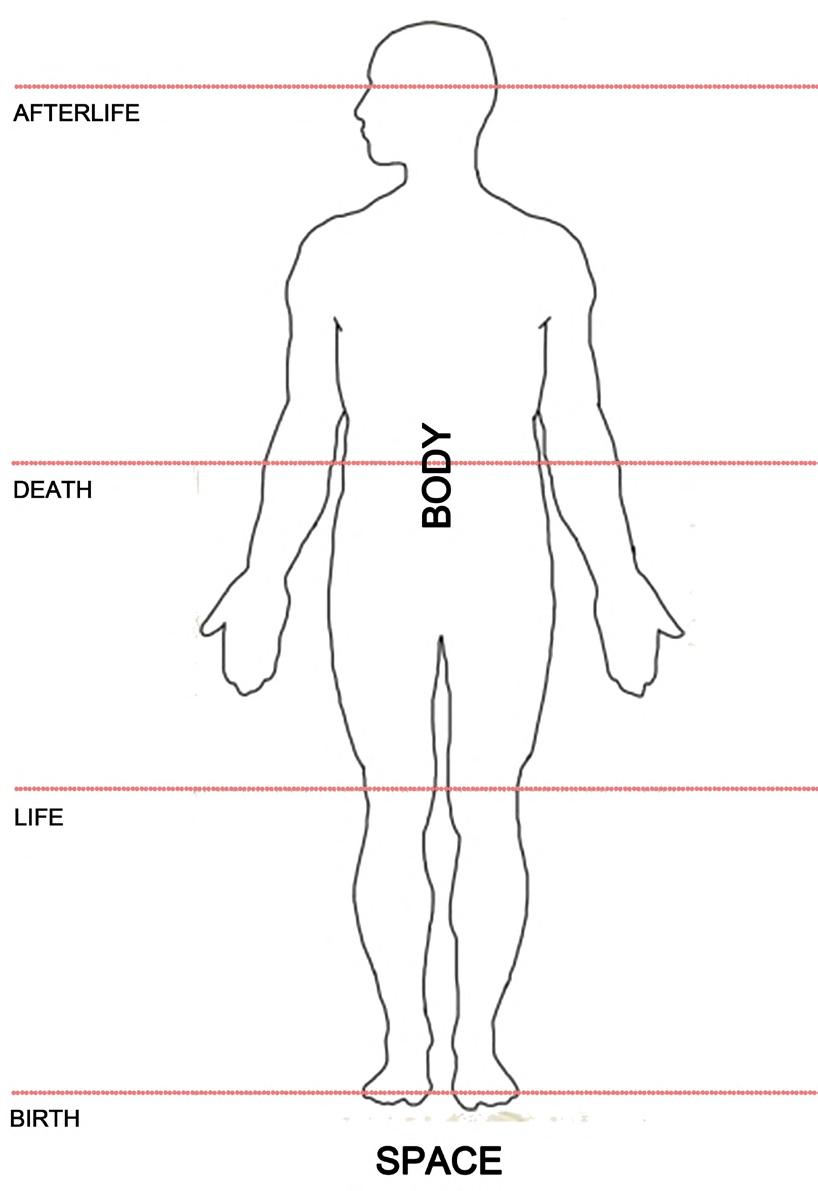

To approach the ground as the fiction of land, and to build on it as such is to inadvertently maintain the practice of terra nullius-ing. Radical and restorative forms of spatial practice require a retiring of such fictions, to once more philosophize from the ground itself, rather than from its ideological overlays/veneer. Unit 19 applies four principal approaches in an ongoing attempt to retire approaches to such fictions:

1. Firstly, we treat the ground as a calendar, and engage its temporalities in an effort to materialize new futures. In this way, architecture remains a tool of

Architecture’s logics” (Chigariro in Sindi, 2021: v).

measure, but the form that it takes reflects other notions of time, and their corresponding material characteristics.

2. Secondly, we approach sites as grounds, to liberate the design process from being primarily informed by a site’s material (or territorial) constraints, i.e., the substitute ground. We work toward uncovering, mapping, and languaging the ideological frameworks that dictate a site’s operations, so that we can engage a ground’s philosophical possibilities primarily.

3. Thirdly, the graduate studio approaches cartographies as calendars. In the English language, time is often referred to through spatializations (i.e., the past is referred to as being far, or behind us, or the ‘now’ is said to be ‘here’, etc.); a tendency known in linguistics as space-time mapping. The object of maps allows for the re-presentation of this fused space-time, but French philosopher Henri Bergson (1889) argues a fundamental incompatibility with “representing time by space”, because the mapped image is not the territory itself, but a mere re-presentation/ symbol of reality. As maps cannot account for lived knowledge, i.e., one cannot go back in time in the way one is able to turn around in space, Bergson argues that the body-as-map and symbolic maps are ultimately un-equivalent, in favour of embodied cartographies, and although we treat maps as true representations of their depicted territories, they in fact do the opposite: they objectify time and space, and render flat all experiential notions of them. To practice cartographies as calendars requires the practice of embodiment, which brings along with it expanded forms of measurability, map-ability, and evidencing of diverse people, places, knowledges, and temporalities.

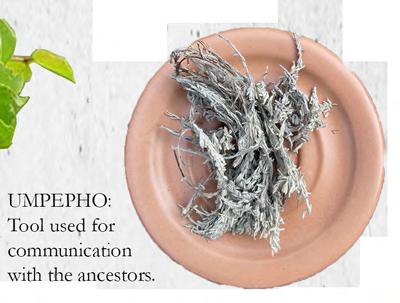

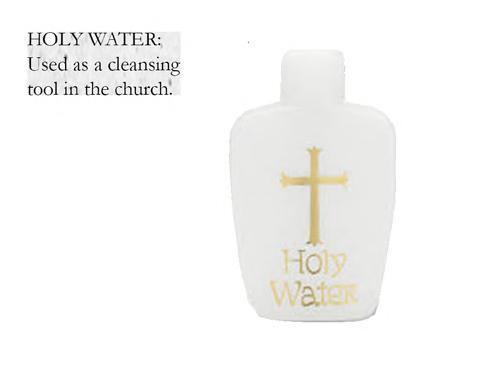

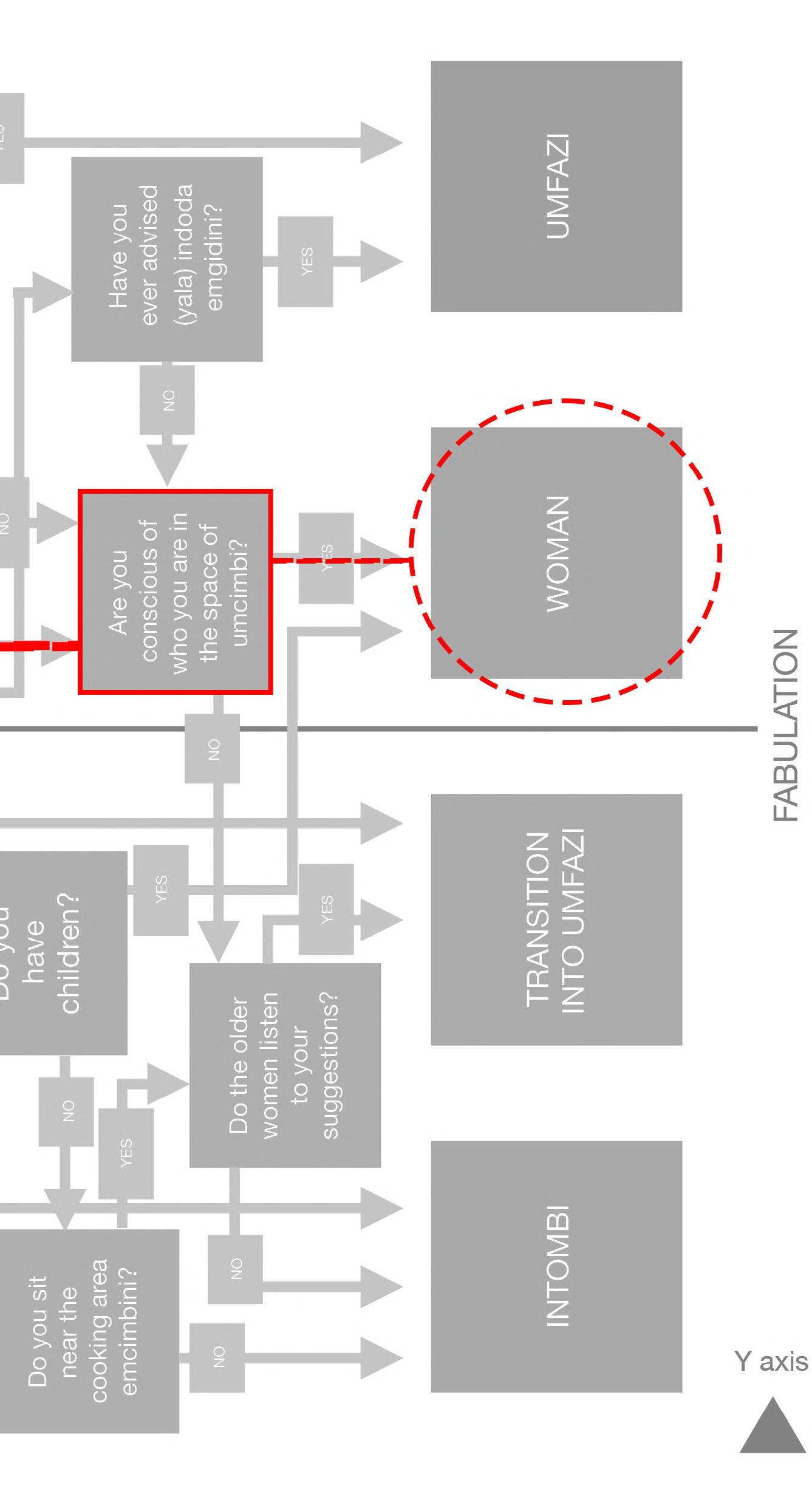

4. Finally, and based on the above point, we prioritize ritual practice (rather than spatial programming) as architectural typology and approach it as a tool of measure through embodied cartographic notions. The capacity that rituals have to appropriate space and its [infra]structures expose the vulnerability of spatiotemporal programming as it resets programmatic prescription. This lens also makes way for rituals whose infrastructures were targeted and disrupted, erased, or deemed immeasurable through colonial conquest, yet remain critical parts of the daily rhythms of marginal groups who forcefully claim the material accommodation of those rituals through spatial practices such as appropriation.

Through this methodological framework, the design research practice methodology of the Unit conflates approaches to cartography, calendars (and as a result, futures), grounds, and rituals, toward suspending speculating from captive grounds, and to make way for alternate fantasies and futures that override our current nature of spatial inevitability and crisis.

To revert back to understanding land as ground by tapping into indigenous knowledge systems again is a radical world-building endeavour that does not offer quick fixes to the problems of the 21st century, but attempts to offer truly sustainable capacities for radical new futures.

References:

1. Apollonio, H., 1998. Identifying the Dead: Eighteenth Century Mortuary Practices at Cobern Street, Cape Town. University of Cape Town.

2. Arfaoui, M., 2022. Time and the Colonial State. [online] THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. Available at: <https://thefunambulist.net/ magazine/they-have-clocks-we-have-time/ time-and-the-colonial-state> [Accessed 12 May 2021].

3. Barthes, R. and Lavers, A., 1972. Reading and deciphering myth, in: Mythologies. New York: The Noonday Press, pp.128.

4. Beaumont, E., 2020. uneven ground. [online] Architectural Review: on Land. Available at: <https://www.architectural-review.com/ essays/letters-from-the-editor/editorialuneven-ground> [Accessed 17 August 2021].

5. Bhandar, B., 2020. Lost property: the continuing violence of improvement. [online] Architectural Review: on Land. Available at: <https://www. architectural-review.com/essays/lost-propertythe-continuing-violence-of-improvement> [Accessed 17 August 2021].

6. Chigariro, A., 2021. There is no hand or gaze to stop you. in: T. Sindi, ed., oNform T-02: The Myth of Violence. [online] Available at: < https:// issuu.com/gsaunit19/docs/onform_t-02_ final_pages_compressed> [Accessed 13 January 2022].

7. Chimurenga Chronic, 2018. The Idea of a Borderless World. pp.4-5.

8. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2021. ground. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary.cambridge. org/dictionary/english/ground> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

9. Mignolo, W., 2015. Sylvia Wynter: What Does It Mean to Be Human?. in: K. McKittrick, ed., Sylvia Wynter on Being Human as Praxis Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp.106-123.

10. Phillips, R., 2022. Placing Time, Timing Space: Dismantling the Master’s Map and Clock. [online] THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. Available at: <https://thefunambulist.net/ magazine/cartography-power/placing-timetiming-space-dismantling-masters-map-clockrasheedah-phillips> [Accessed 12 May 2021].

11. Ristic, M., 2018. Architecture, Urban Space and War: The Destruction and Reconstruction of Sarajevo [Place of publication not identified]: Switzerland, pp.29, 34-38.

12. www.UNESCO.org., unknown. Indigenous Knowledge and Climate Change. [online] Available at: <https://en.unesco.org/links/climatechange> [Accessed 30 May 2022].

v ix xvi

^EDITOR’S NOTE_CONTENTS / 2022

FOREW[A]RD

An African Laboratory of Unsettling Pedagogy, by Kabage Karanja

EDITOR’S NOTE

Unsettling [Chronopolitical] Ground, by Tuliza Sindi

INTRODUCTION

Unsettling Ground 2022

T-03: Beyond the Terra Nullius

‘FRONTIER COUNTRY’

Makhanda, Eastern Cape, South Africa

The Invention of Land

ABOVE GROUND

025 M1 039 M1 053 M1 067 M2

EDIFICE OF ILLUMINATION: A Manuscript. Tasmiya Chandlay

THE MYTHMAKING TERRITORY OF TOURS. Sesethu Mbonisweni

FAÇADES OF BEAUTY. Nobuhle Ngulube

FORGETTING LANGA.

083 M2 103 M2

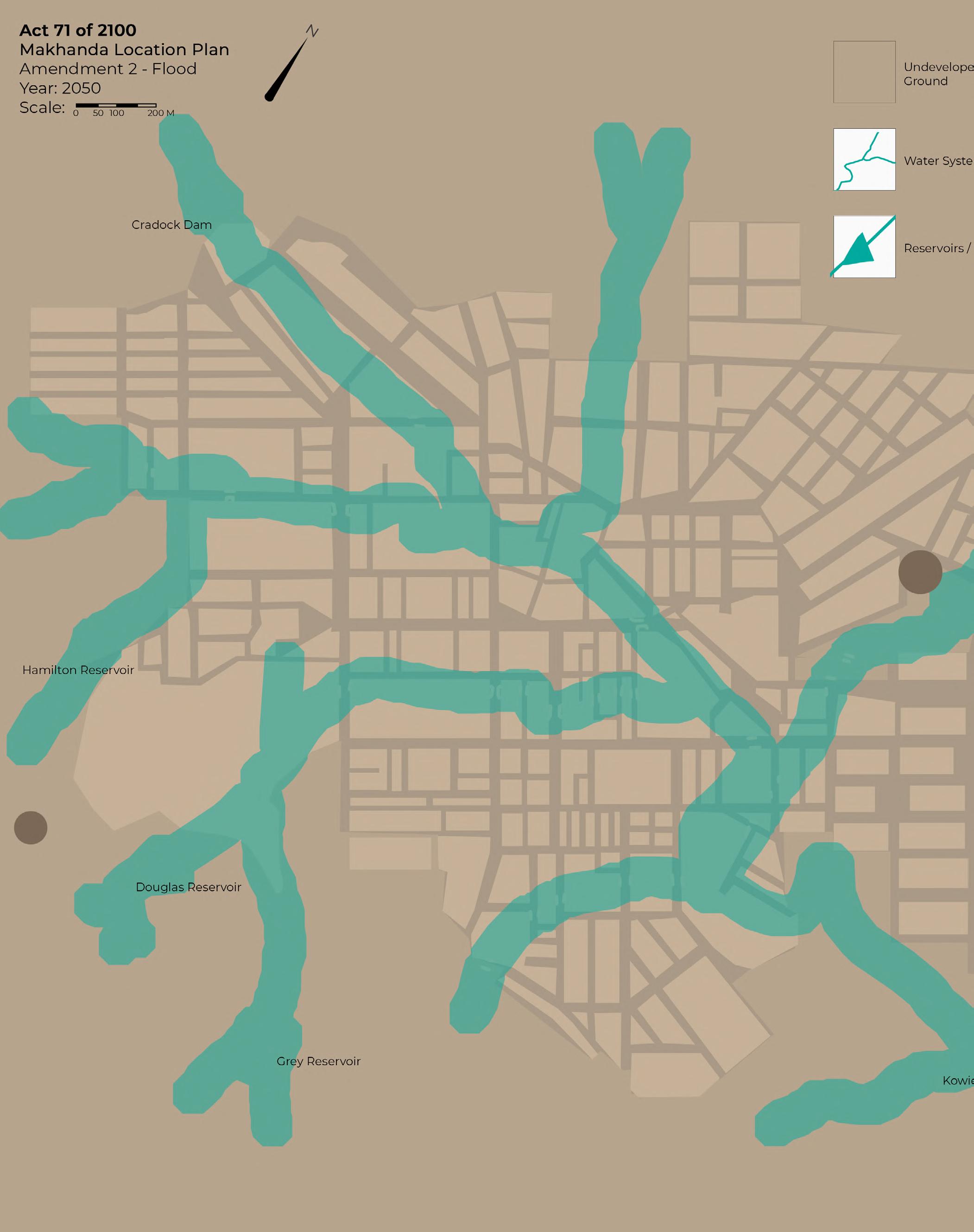

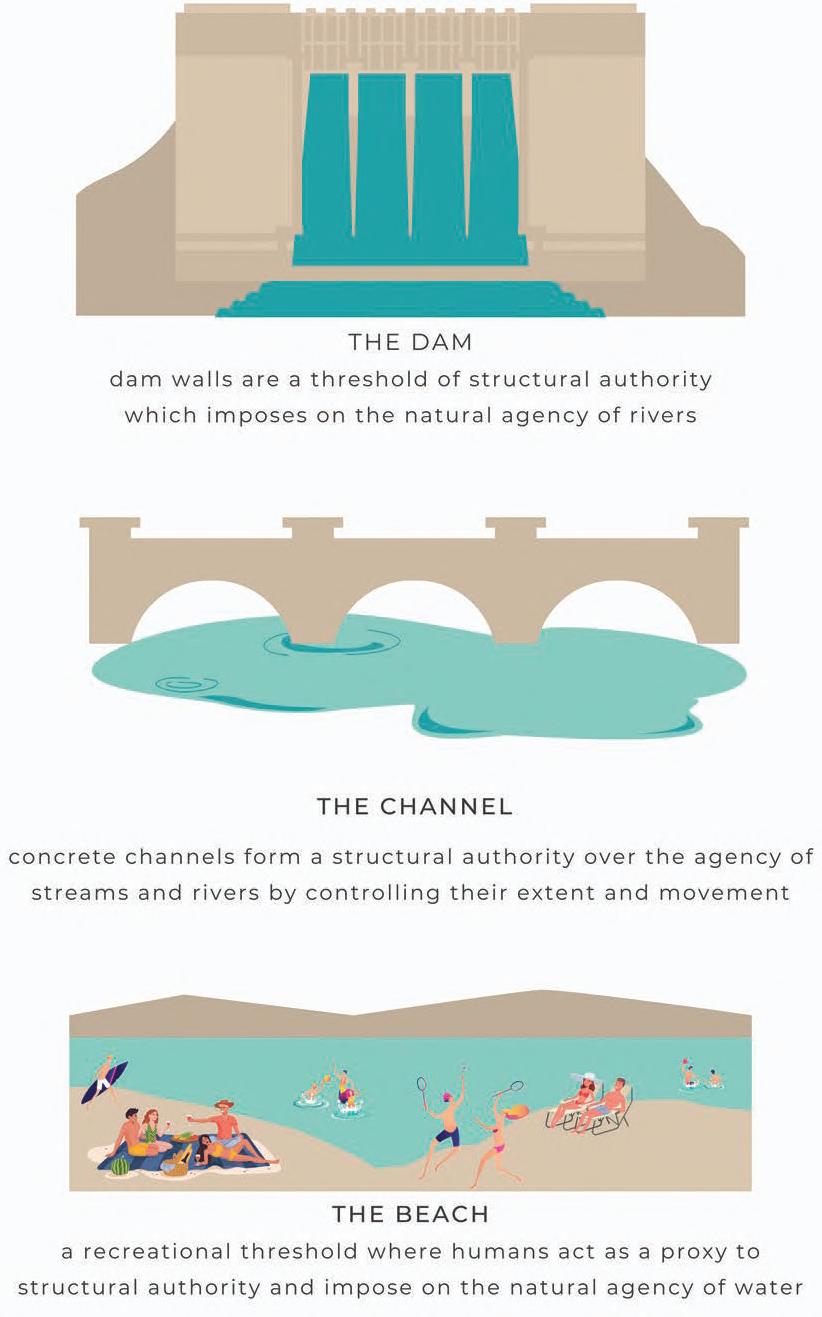

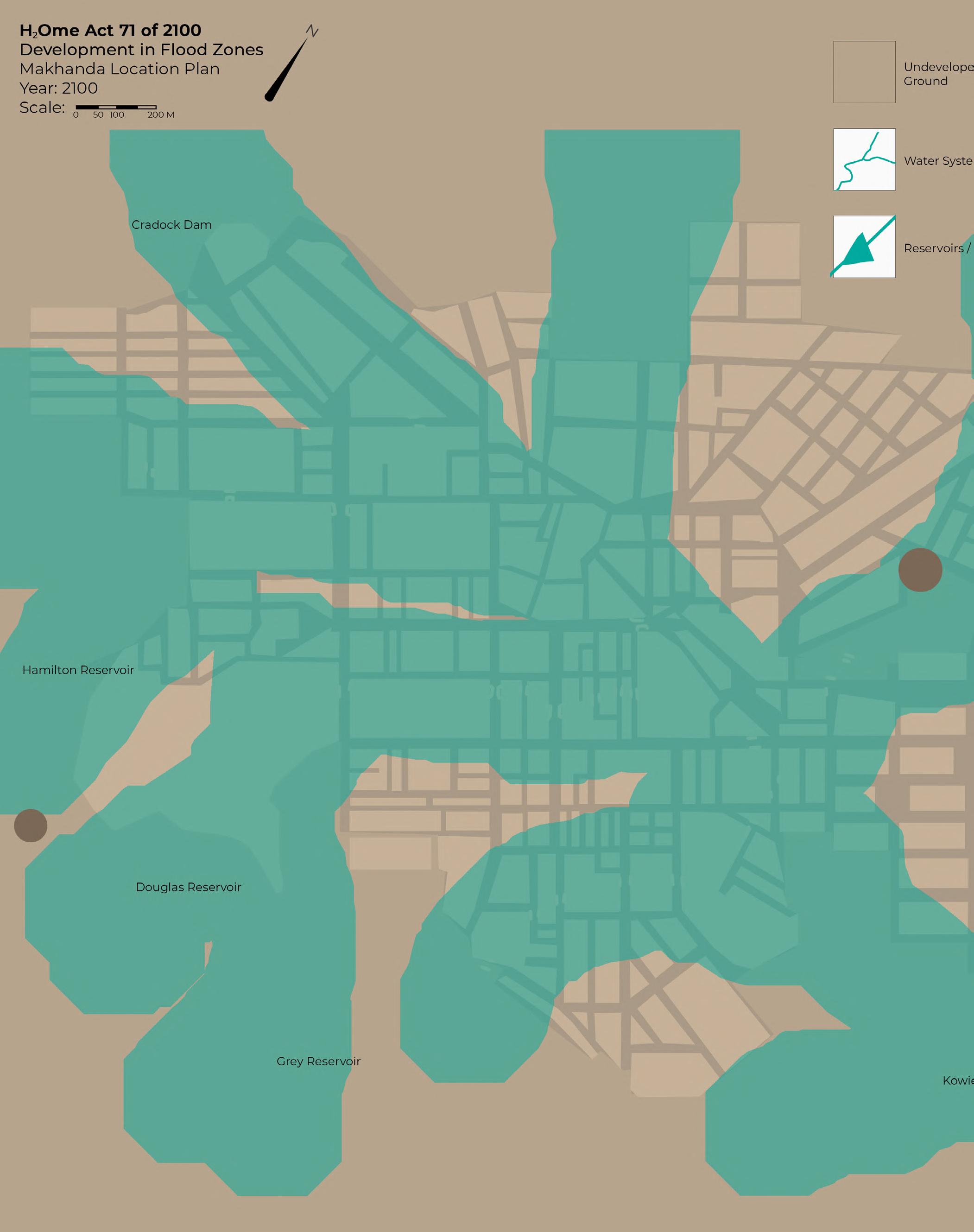

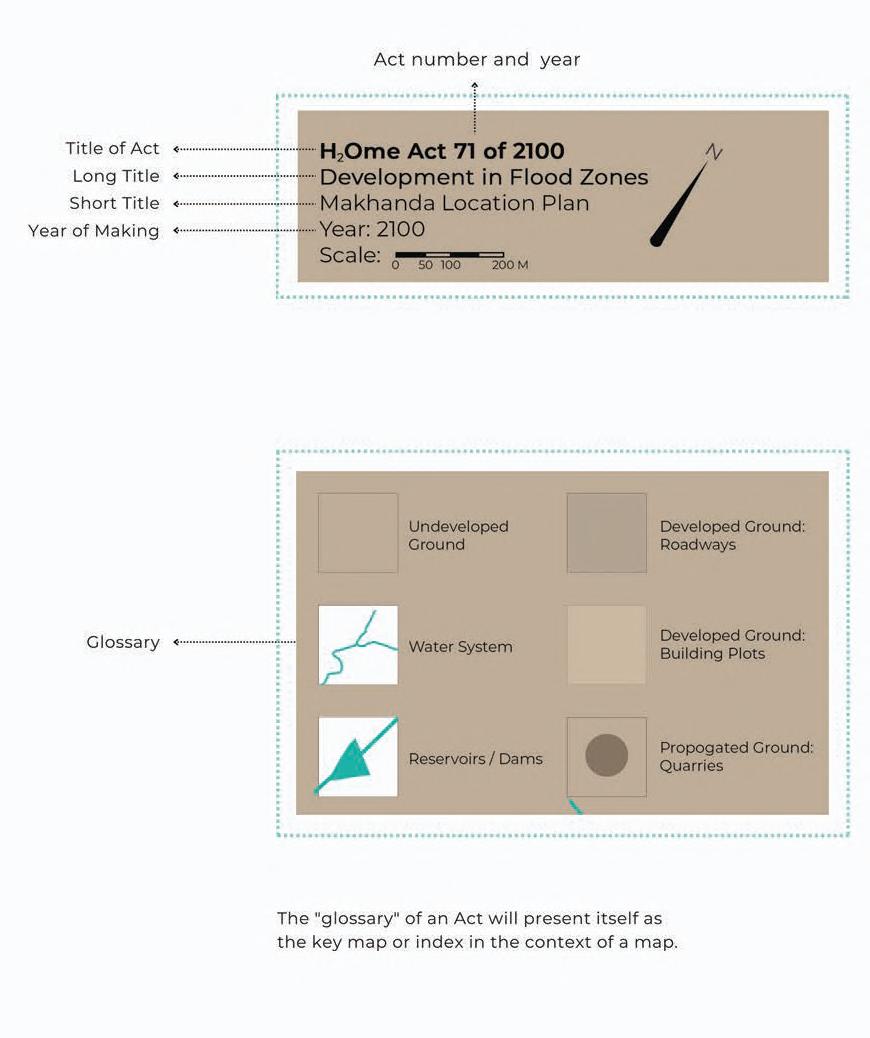

CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE AGENCY OF WATER. Razeenah Manack

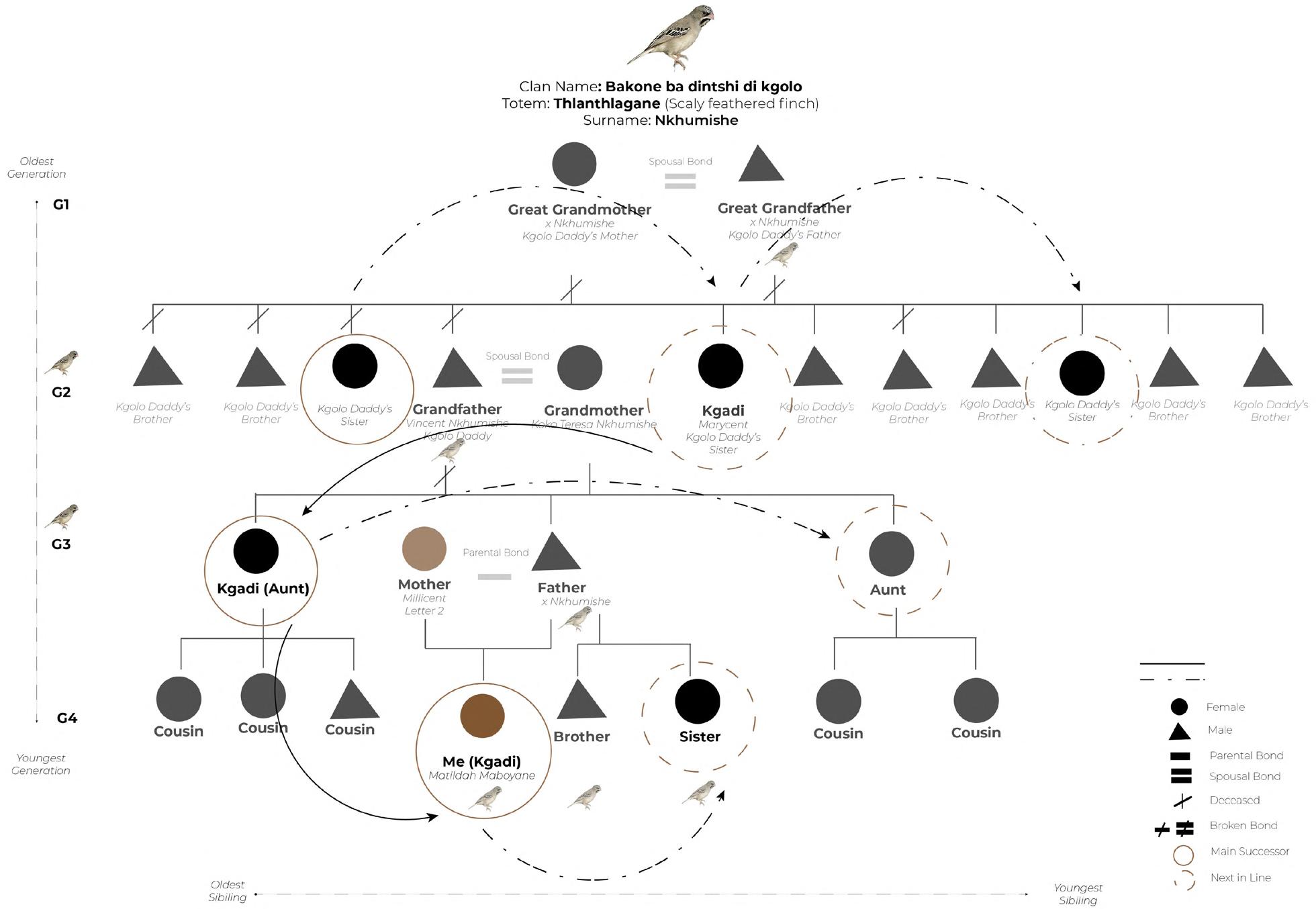

GAEKE KAE? : Living Archive as Mines of Cartographies. Matildah Maboyane

117 M2

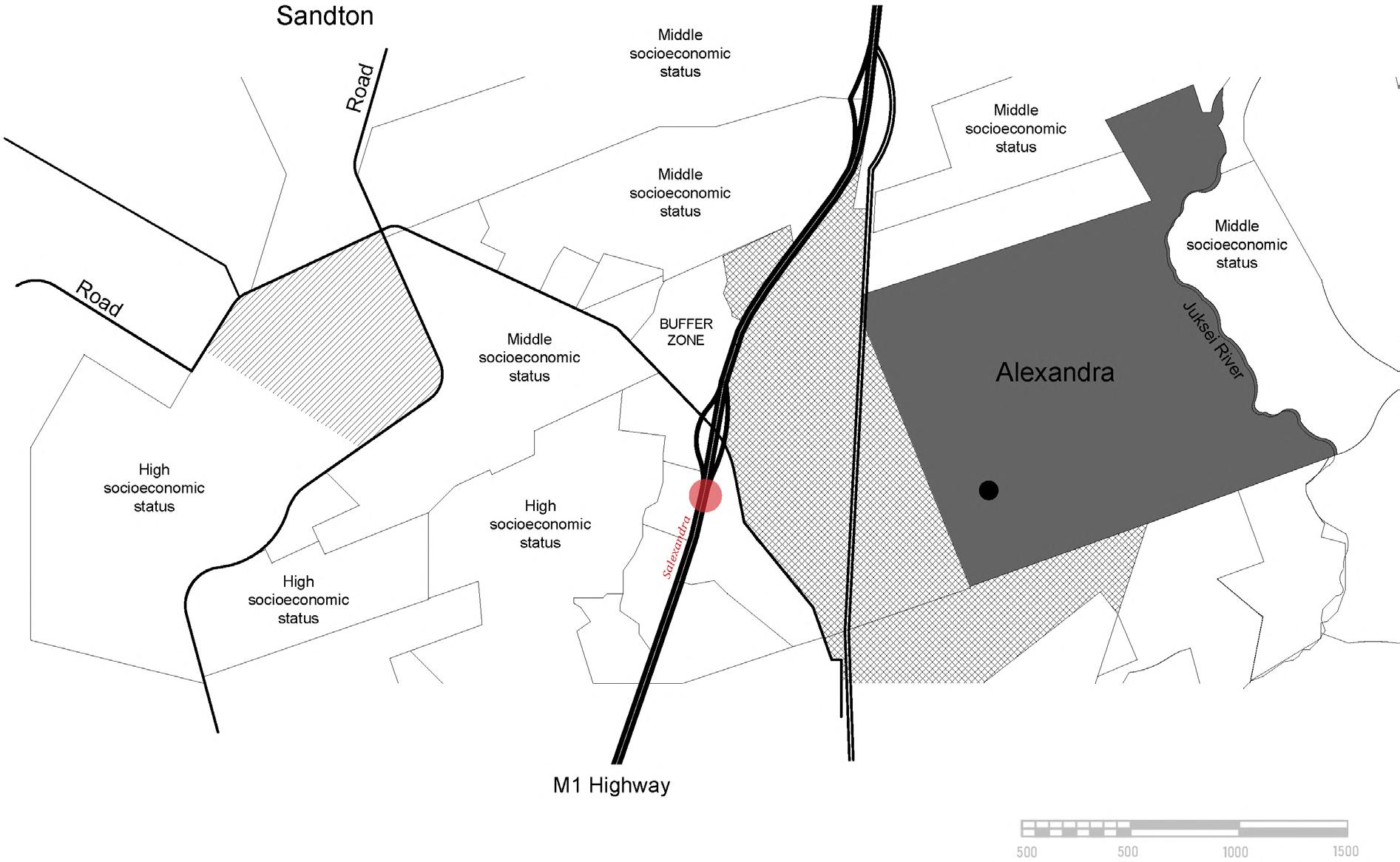

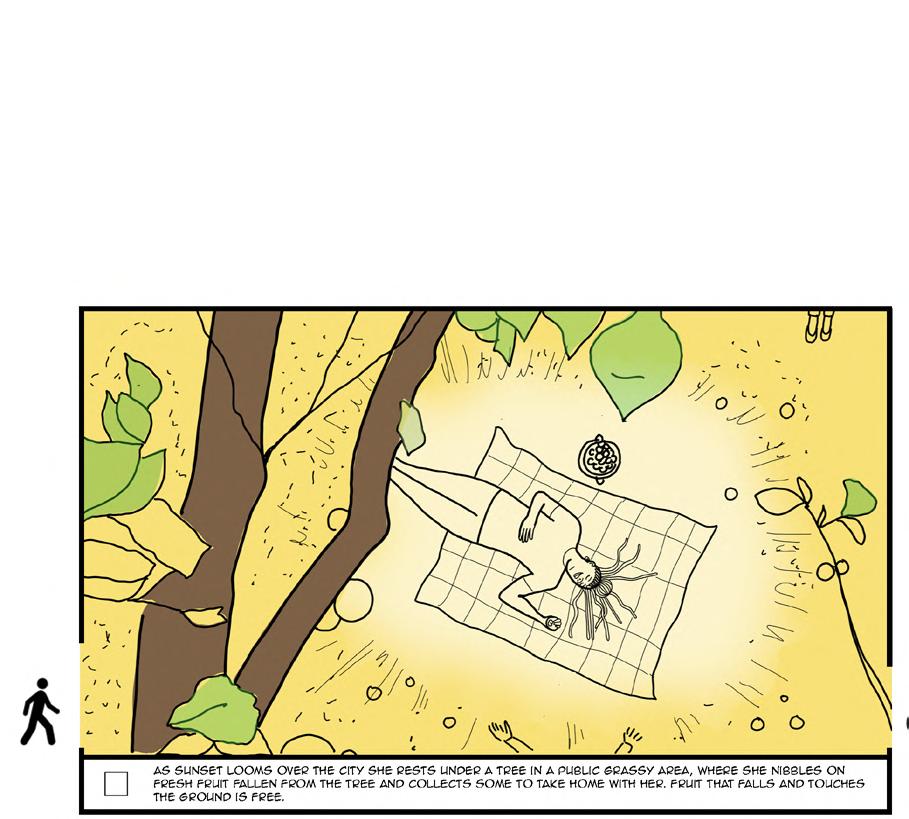

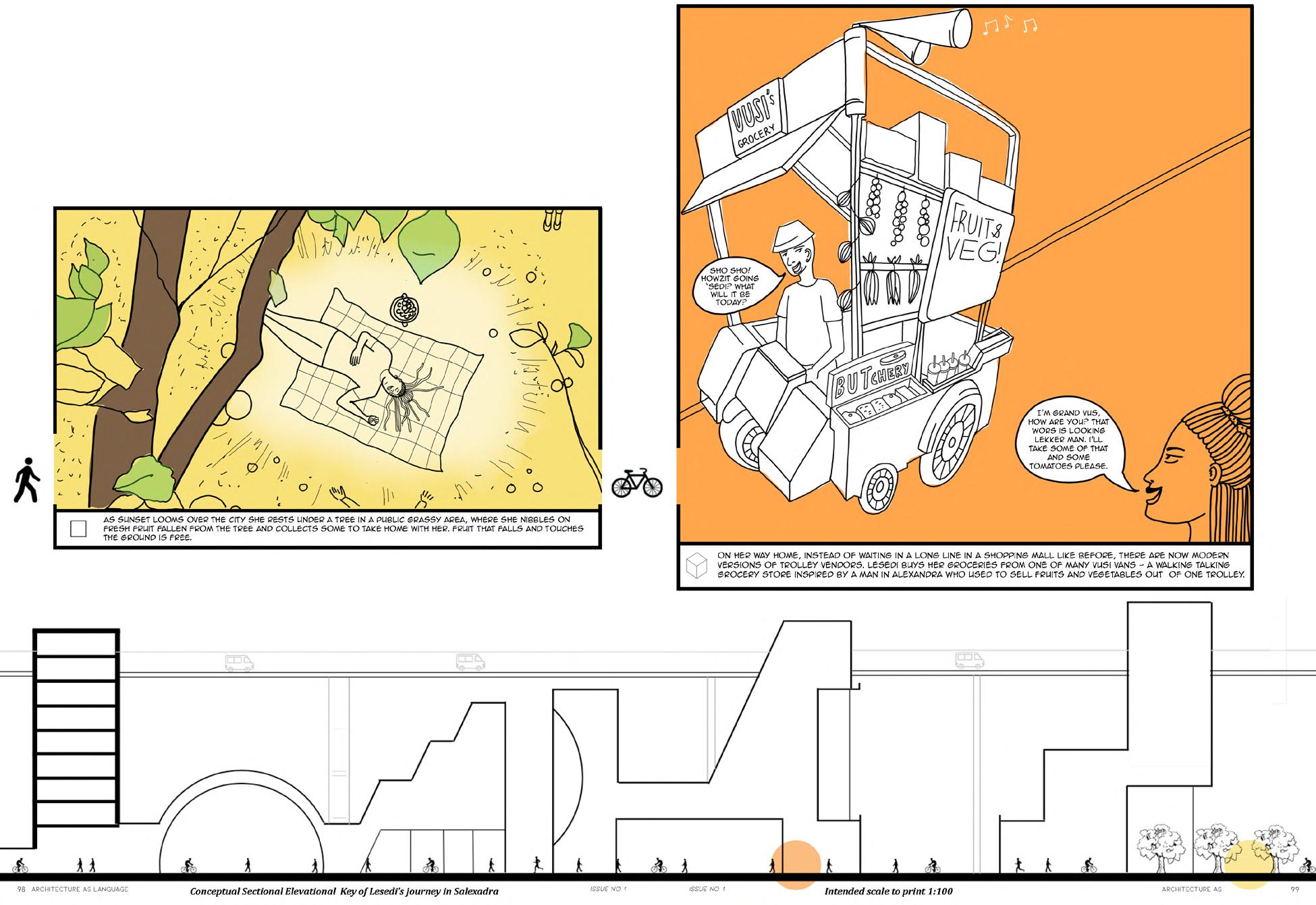

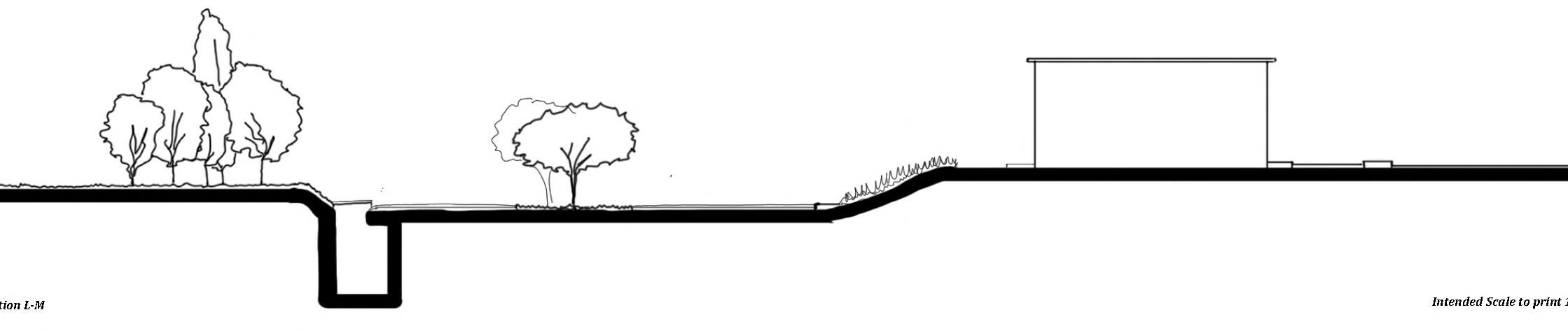

ARCHITECTURE AS LANGUAGE: Paper Portals for Black Leisure from American Modernity to Afro-Modernity in Salexandra. Olive Olusegun

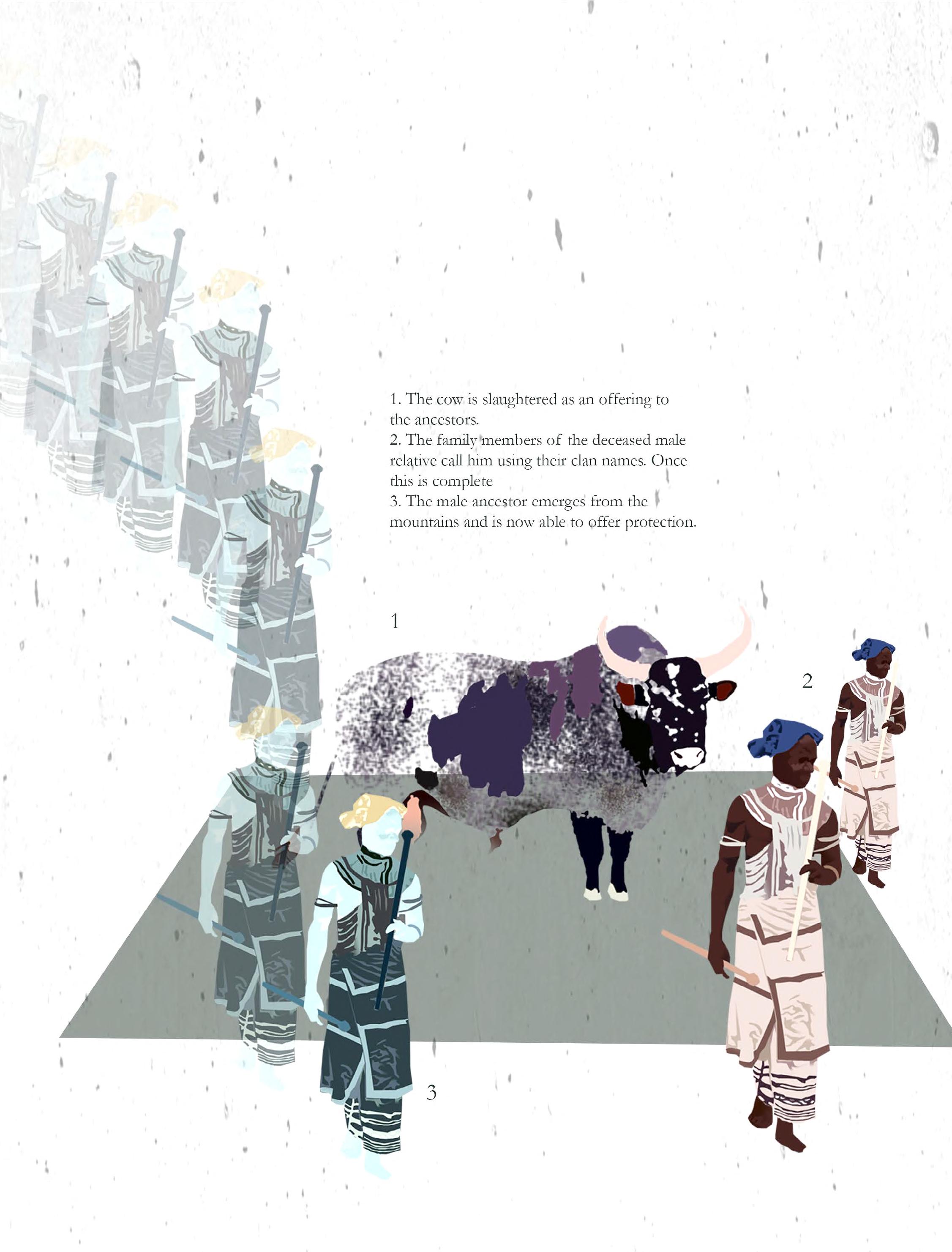

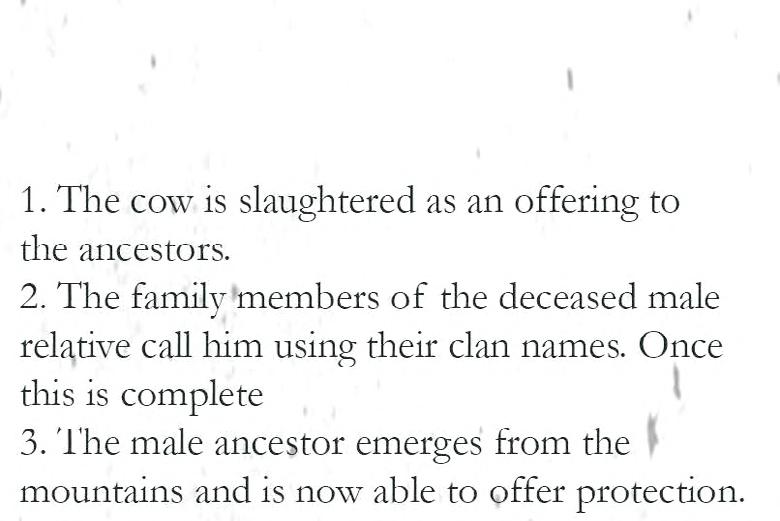

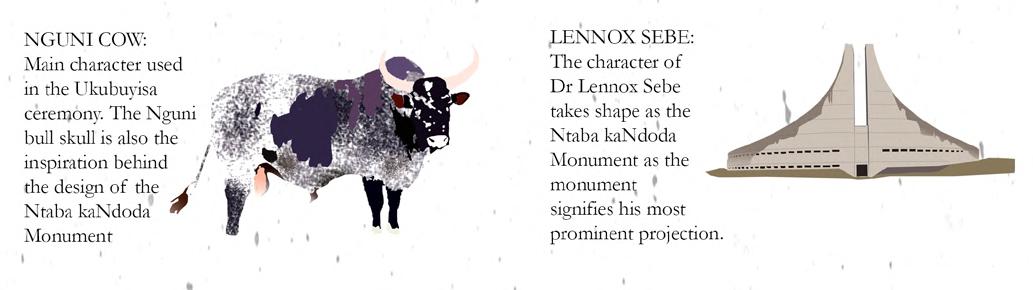

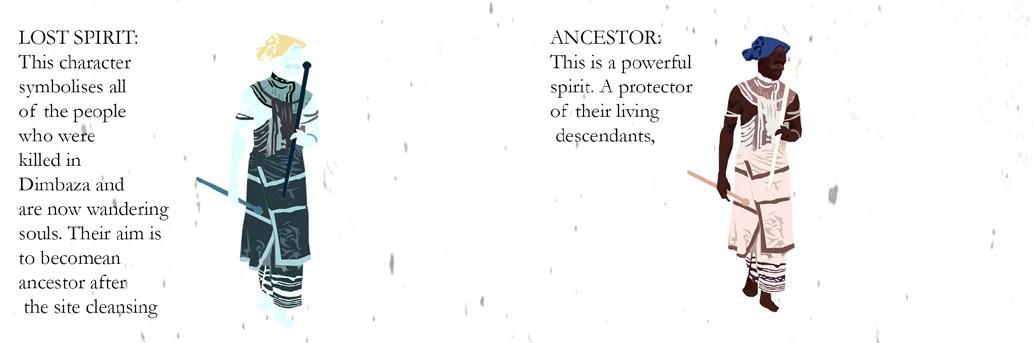

THE GRIM ADVENTURES OF LENNOx SEBE: Exorcising the Ukuza kaNxele Phantom. Masego Musi

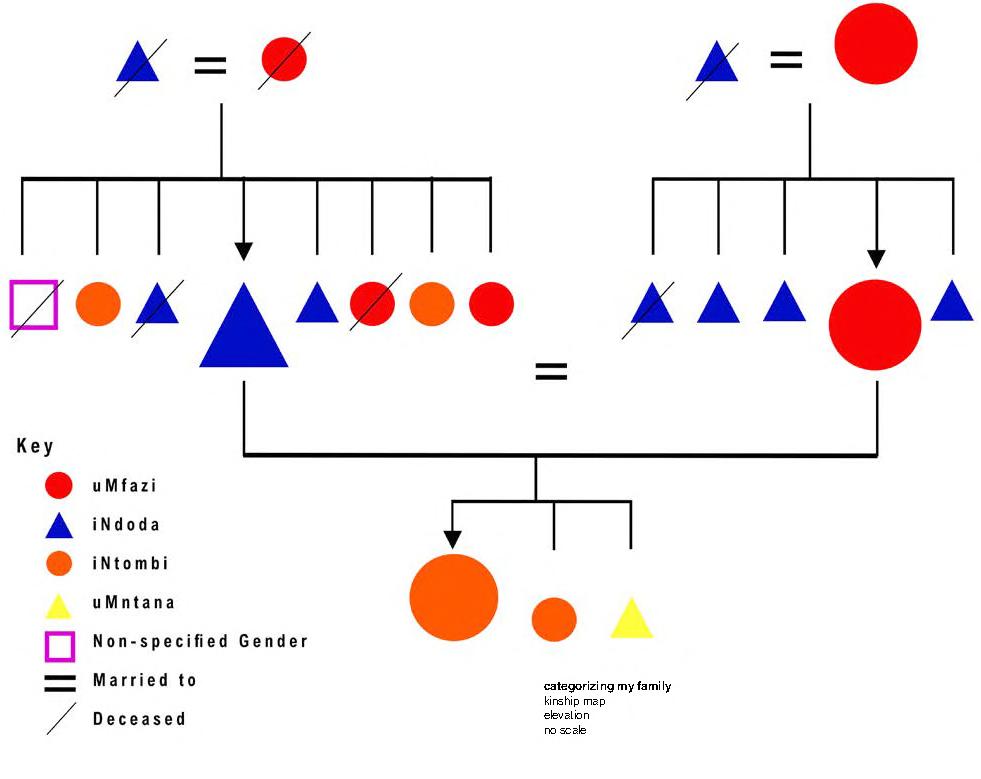

PASSAGE TO RITES: Defining Womanhood esiXhoseni to Escape Identity Purgatory. Siphokazi William

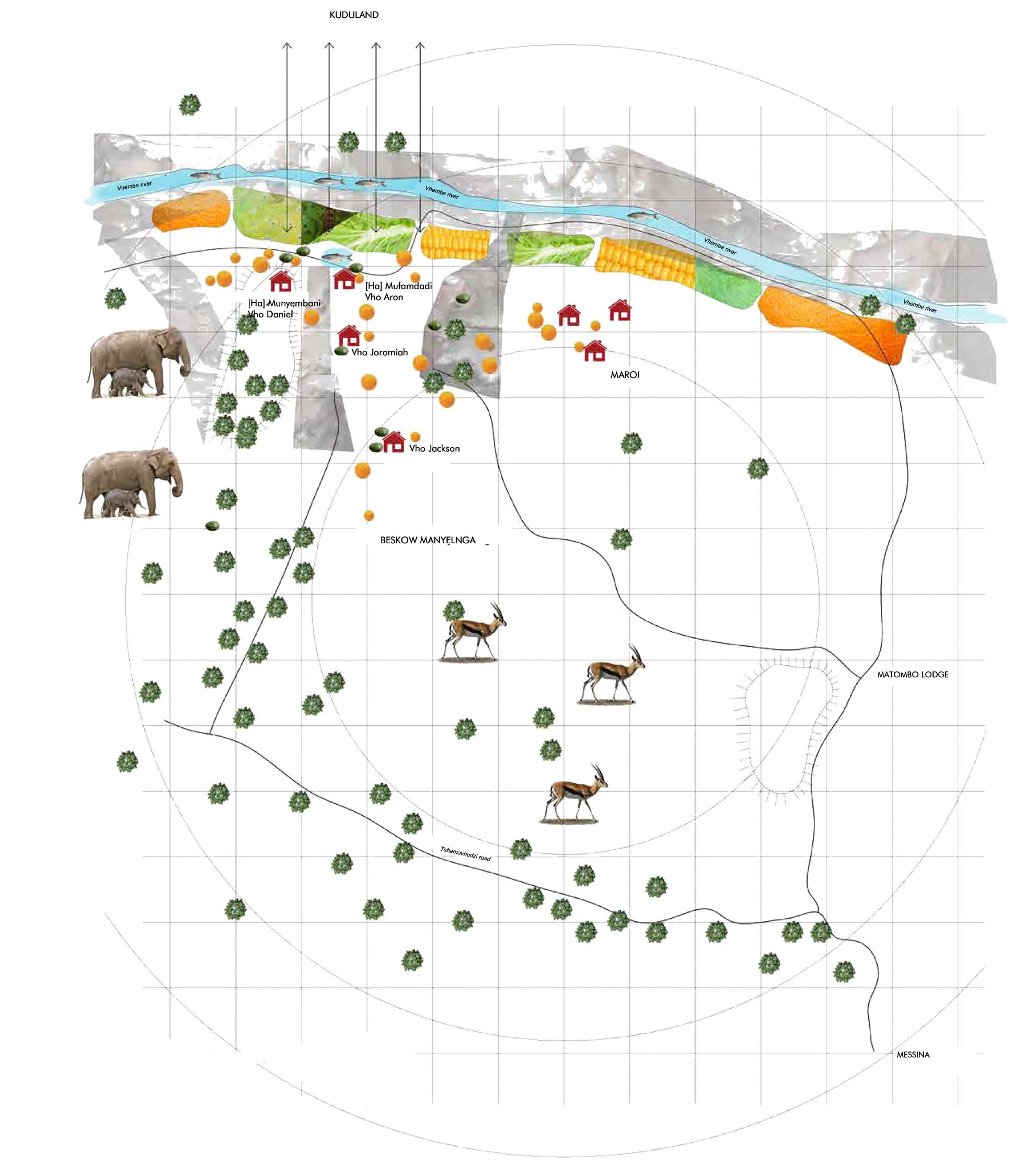

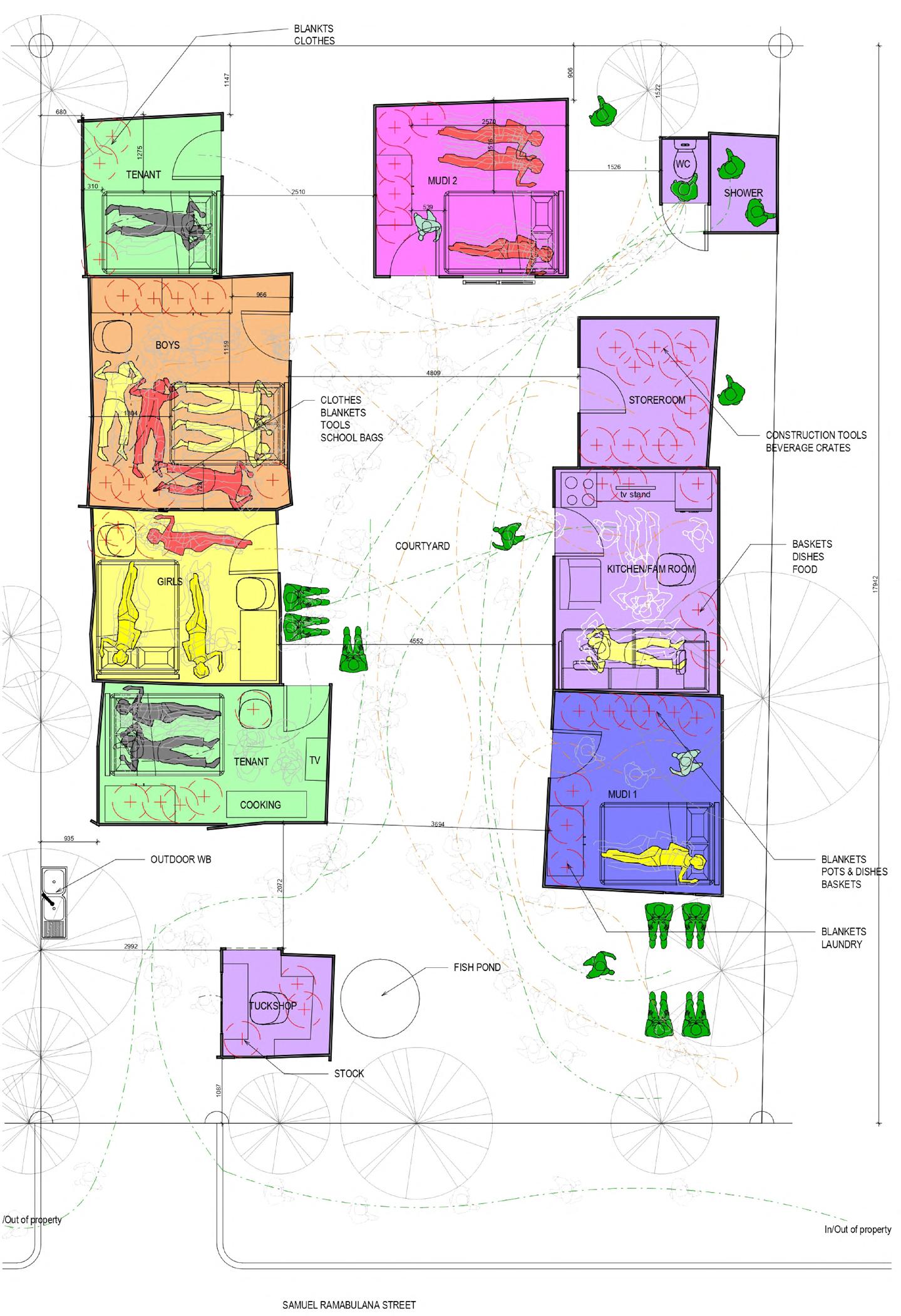

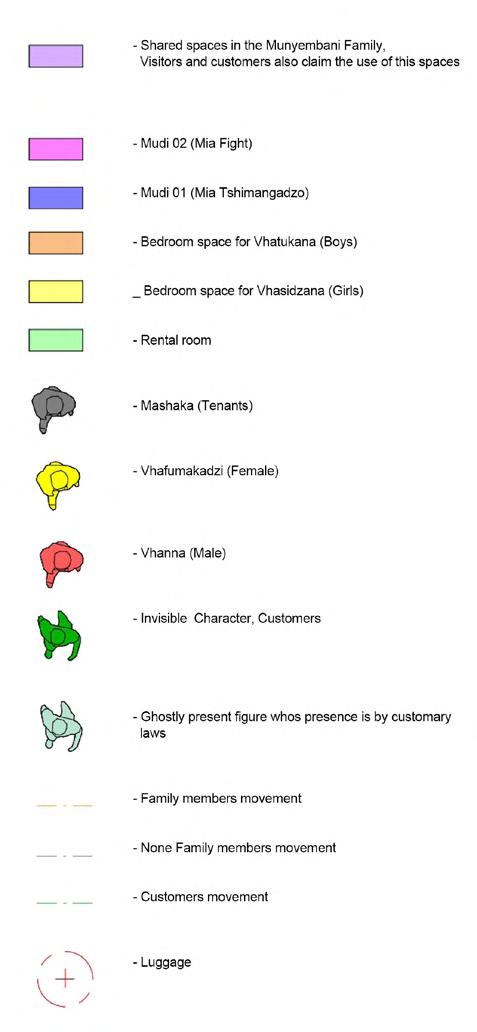

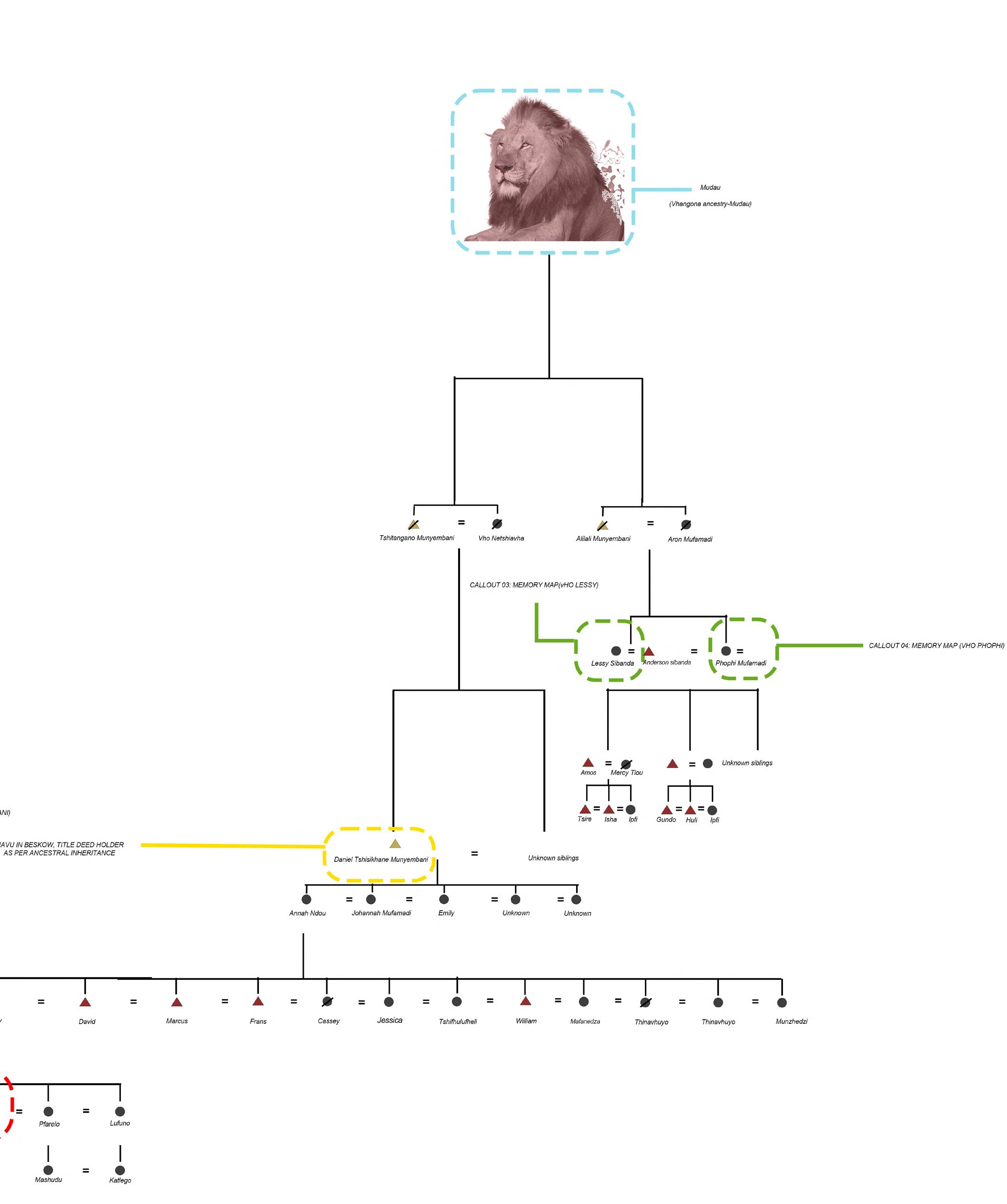

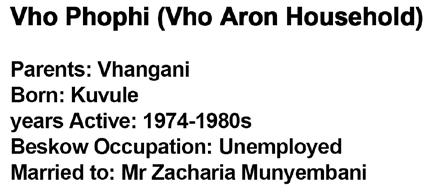

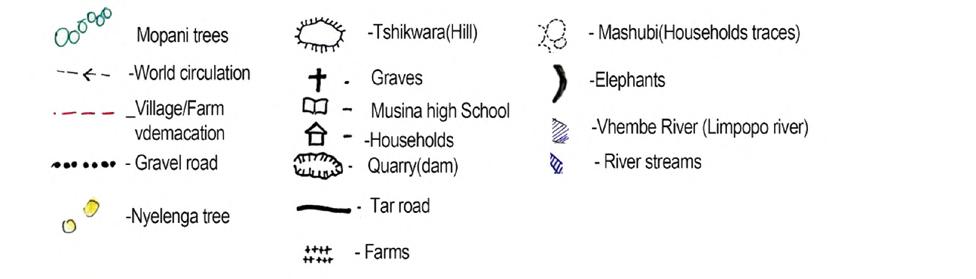

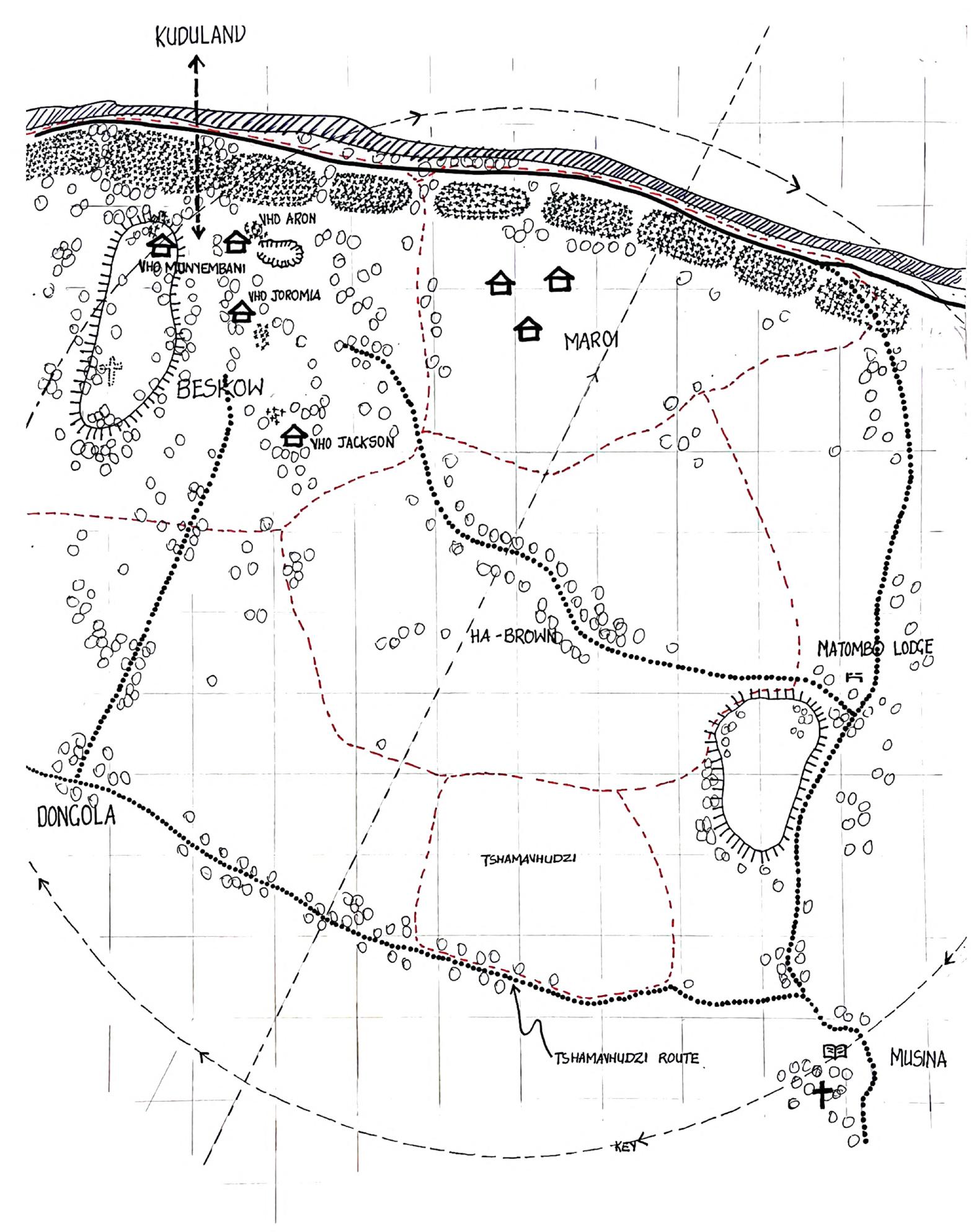

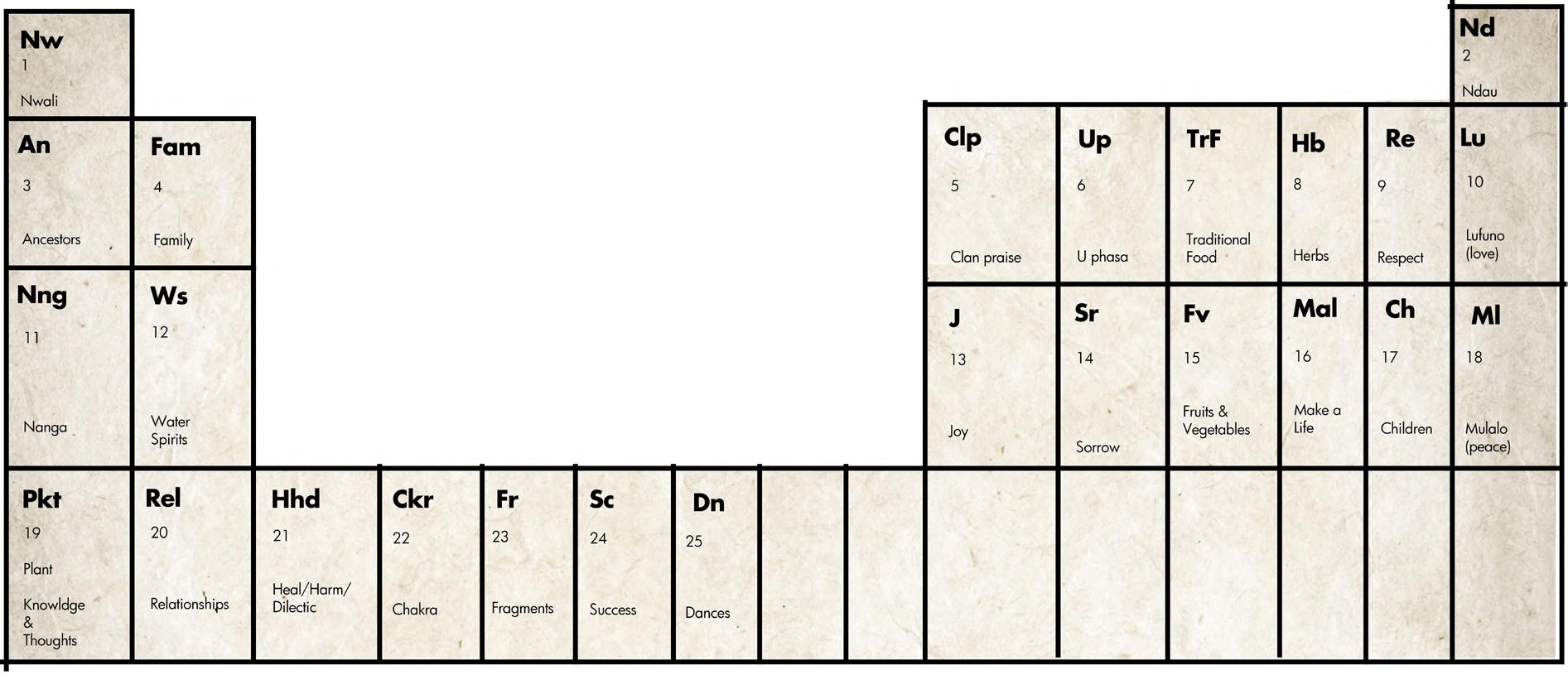

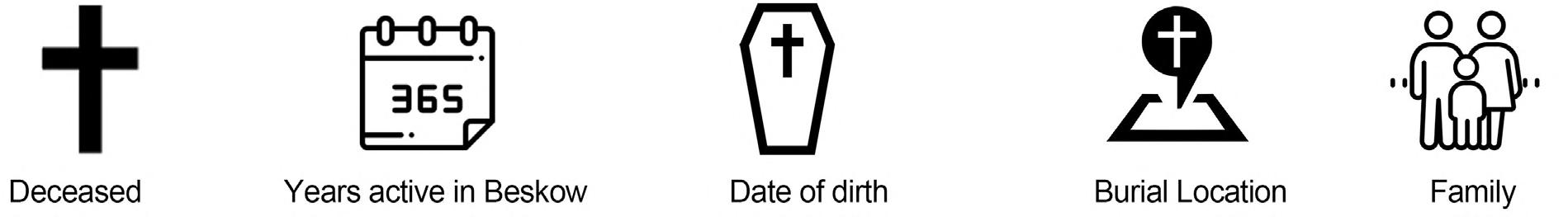

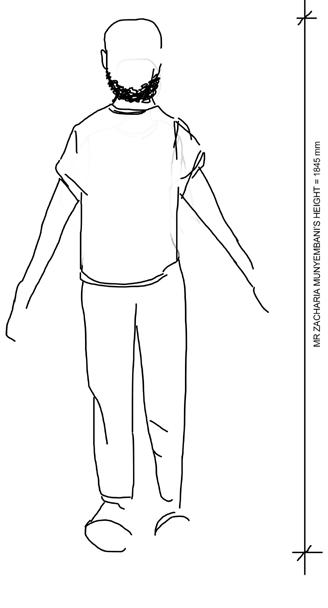

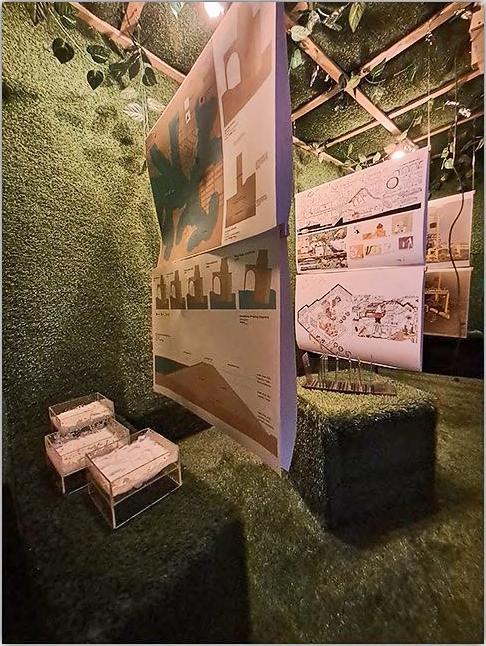

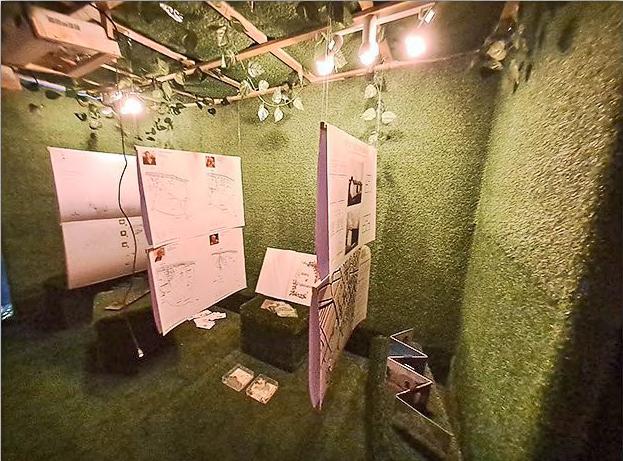

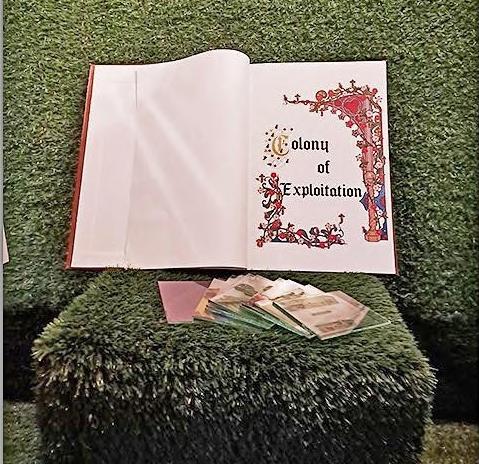

BESKOW: Mavu a Mudi. Vhutshilo Munyembane

T-03: Beyond the Terra Nullius

It is always the same story. Barren land. Undeveloped land. Terra nullius. Barbaric, uncivilized inhabitants. Backward peoples. Jaahil log. The colonial drive to occupy. The colonial drive to expel. The colonial need for self-aggrandizement and dishonest justifications. The myth of the greater god. The myth of knowing better. La mission civilisatrice. “National development.” It is always exactly the same story (Anwar, 2021).

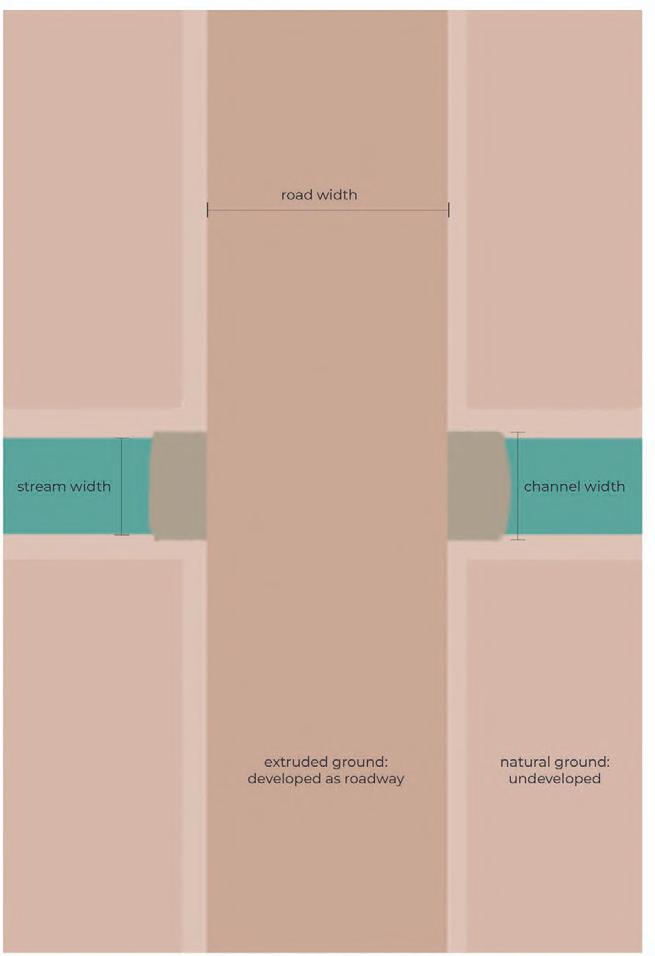

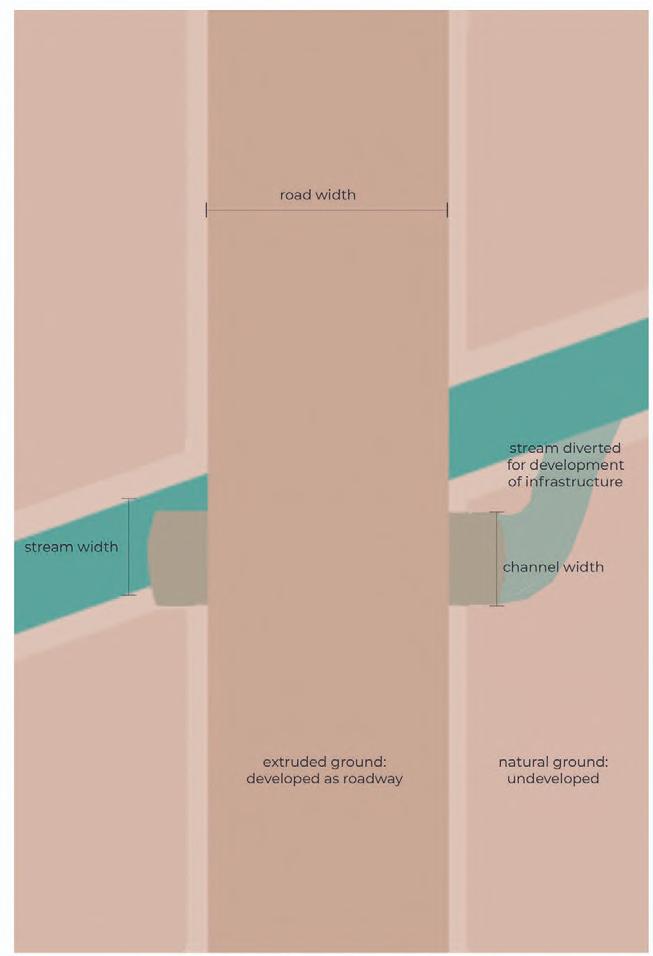

Unit 19 defines architecture as the production of substitute grounds that, in the context of settler-colonial states such as South Africa, operate as negating grounds. These grounds enable sustained practices of displacement (and dispossession1) and erasure of the myriad of alternate meanings and corresponding futures tied to them.

The Unsettling Ground studio works to unravel and disentangle the ongoing settler-colonial legacy of the captured grounds that the Architectural profession inscribes, and in that way, sustains its captivity. The first way that this unravelling occurs is by retiring approaches

1 The word dispossession means to “deprive (someone) of land, property, or other possessions” (dispossession, 2021). It is used tentatively in the framing text as it implies that those who have been dispossessed held the same marketized relationship to land, and on the basis of this shared notion of ownership was the land passed from one hand to another. This negating misnomer suffocates the other notions of meaning that those who have been separated from land might have held, making the extent of loss inaccurately recorded as a loss of property only – or a possessable thing – while that loss included loss of language, of medicinal and food wisdoms, sacred ground, natural infrastructual systems, and so on, all of which are understood through the practice of stewardship rather than ownership. Dispossession as a framing negates other knowledge systems and indigenous ontologies.

to ‘land’ – which delimit our spatial imaginings within the autopoietic confines of settler capitalist conceptions – and rather, adopting approaches to ‘grounds’, or the earth’s surface (and the first architectural plane). While the word ‘ground’ is defined as a natural condition (ground, 2021), ‘land’ is a currency, embodying in its meaning notions of ownership, territory and marketized characterizations of productivity (land, 2021). The Unit approaches these and other such conceptions of the ground as ‘substitute grounds’, and has students suspend those modi operandi, to conjure and catalyse old and new ground philosophies and their accompanying socio-spatial imaginaries.

The Urdu term Jaahil log in the epigraph means ‘ignorant people’ as its direct translation. Its etymology outlines its meaning as ‘barbaric’ or ‘un-civilized’ metaphorically, and ‘illiterate’ literally (jaahil, 2021). It is, in part, on the basis of this misdiagnosed illiteracy by European colonial settlers that psychiatrist Frantz Fanon claimed that separate notions of the ‘Human’ were founded upon, i.e., the literate and superior humanitas2, and the

2 Humanitas is a term that signifies an exceptional kind of humanity capable of engaging in both empirical and transcendental knowledge

Unit Leader: Tuliza Sindi Unit Assistants: Tshwanelo Kubayi, Miliswa Ndziba Unit Advisor: Sarah Trehernewretched anthropos3 (Mignolo, 2015). This perception of the native as illiterate and barbaric was fundamental to the conception of ground-as-land through philosophies of improvement and development by founder of the British modern political economy, William Petty. Petty conflated the value of land (measured on the basis of its productive capacity in that political economy) with the value of people, to create what Brenna Bhandar (2020) refers to as “‘racial regimes of ownership’” (Bhandar, 2020). These new regimes tied socialization, politics, and definitions of Human to the very definitions of the ground, where any use of property that did not bare the hallmarks of individual ownership was deemed inferior, less valuable, and available for appropriation as a terra nullius4 (Bhandar, 2020).

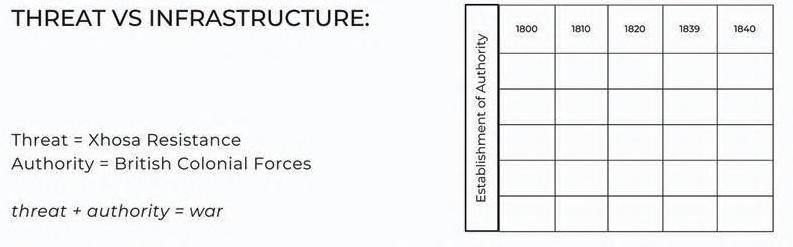

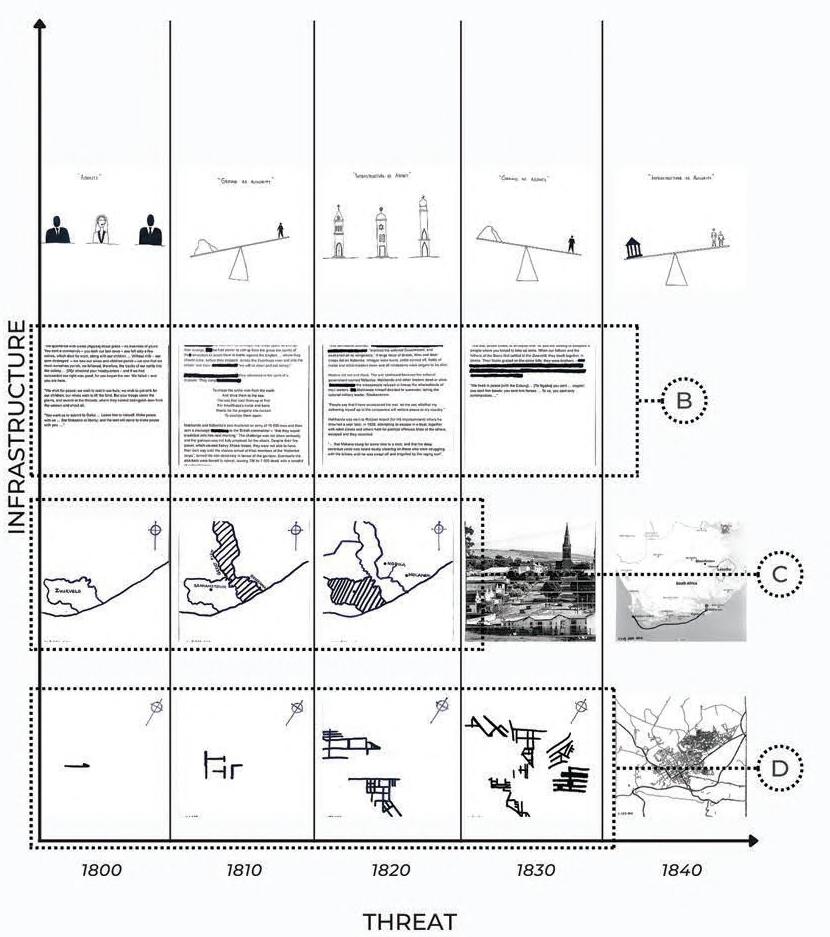

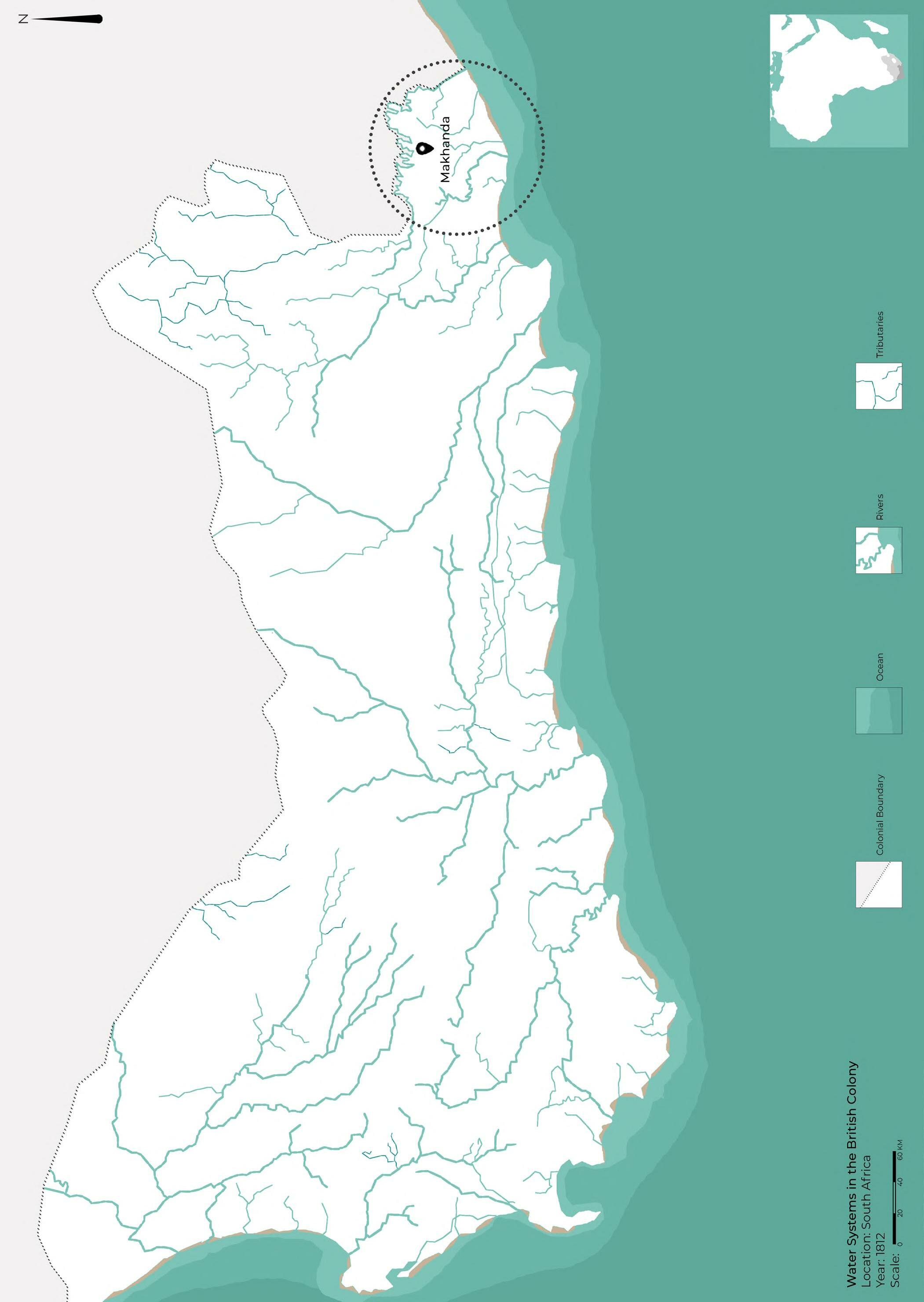

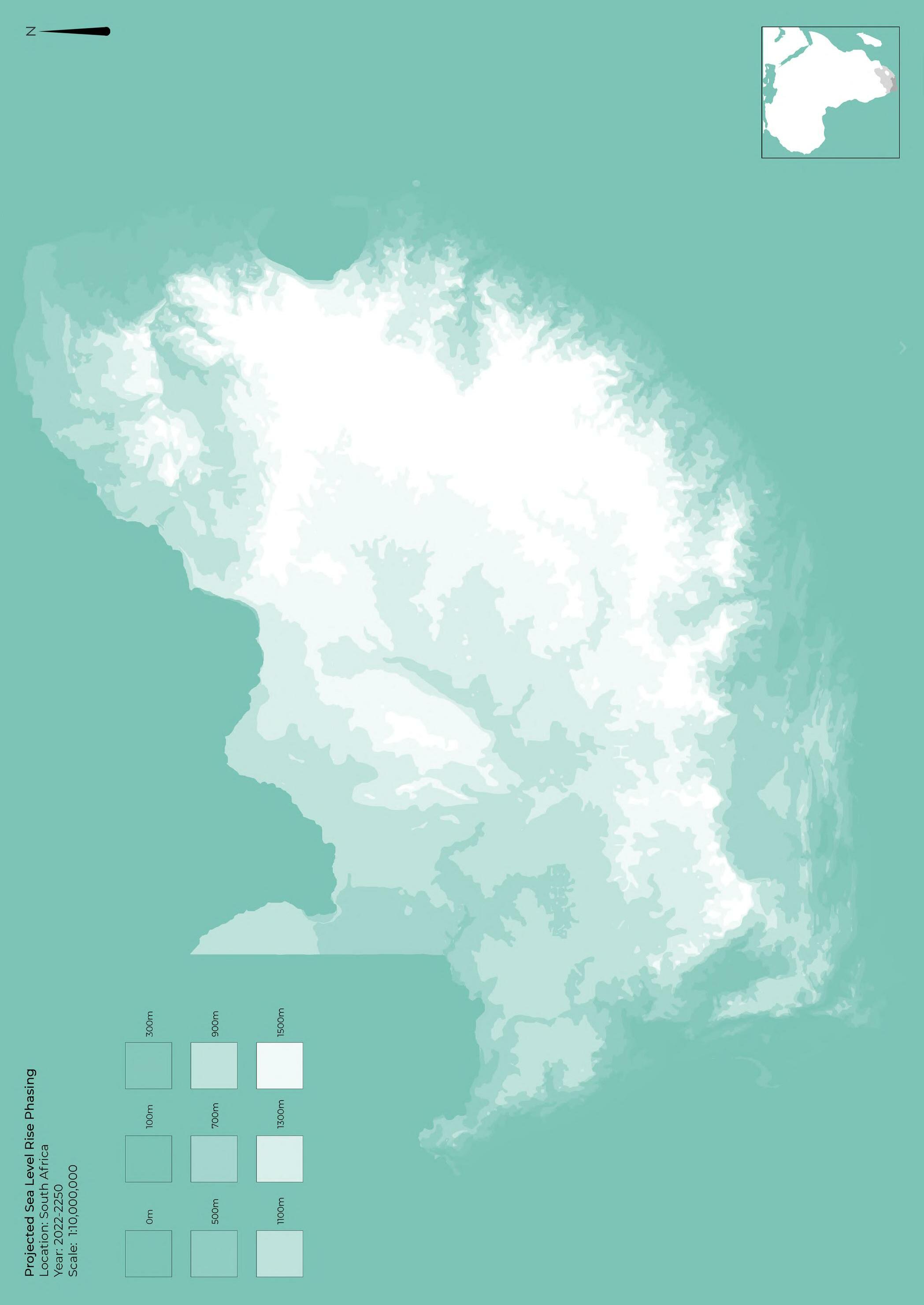

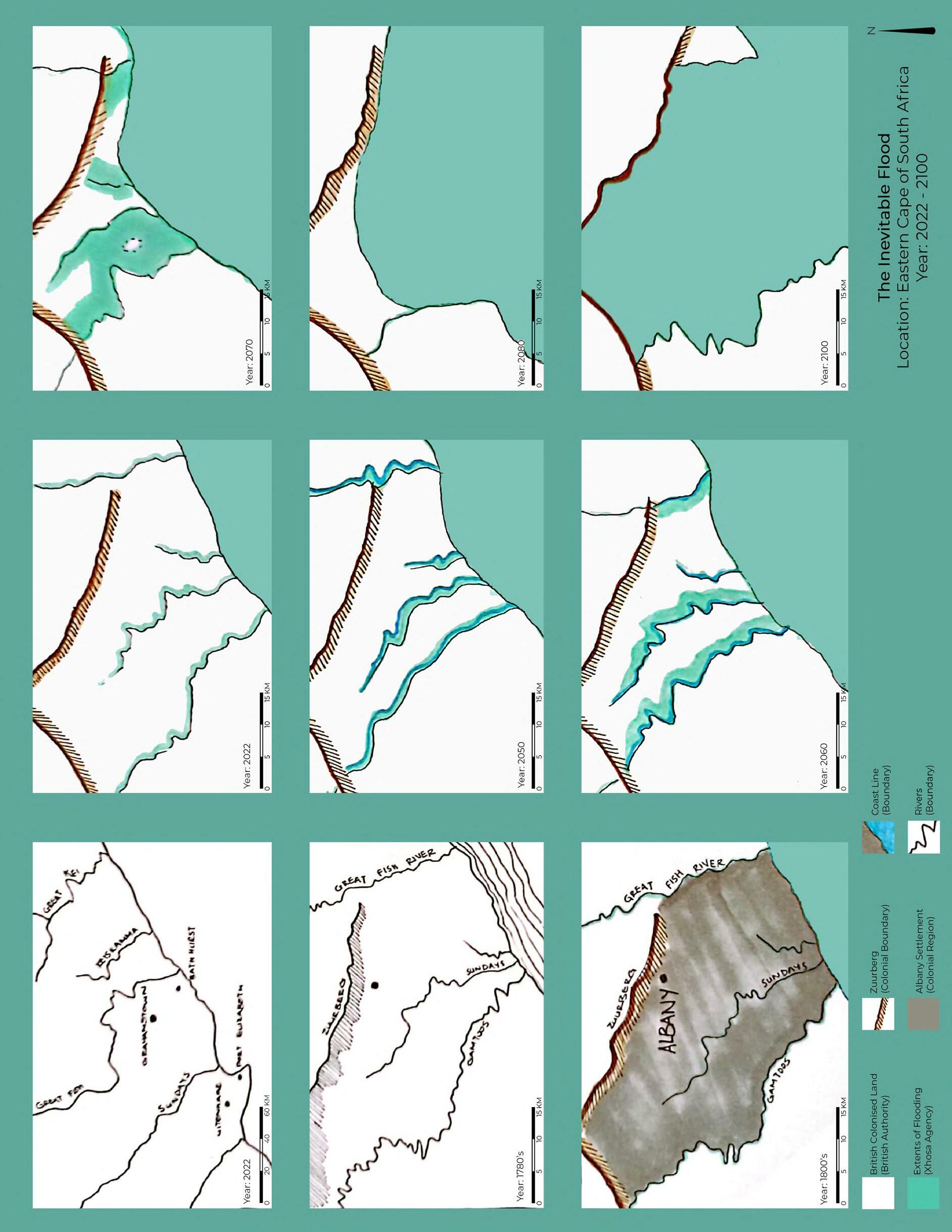

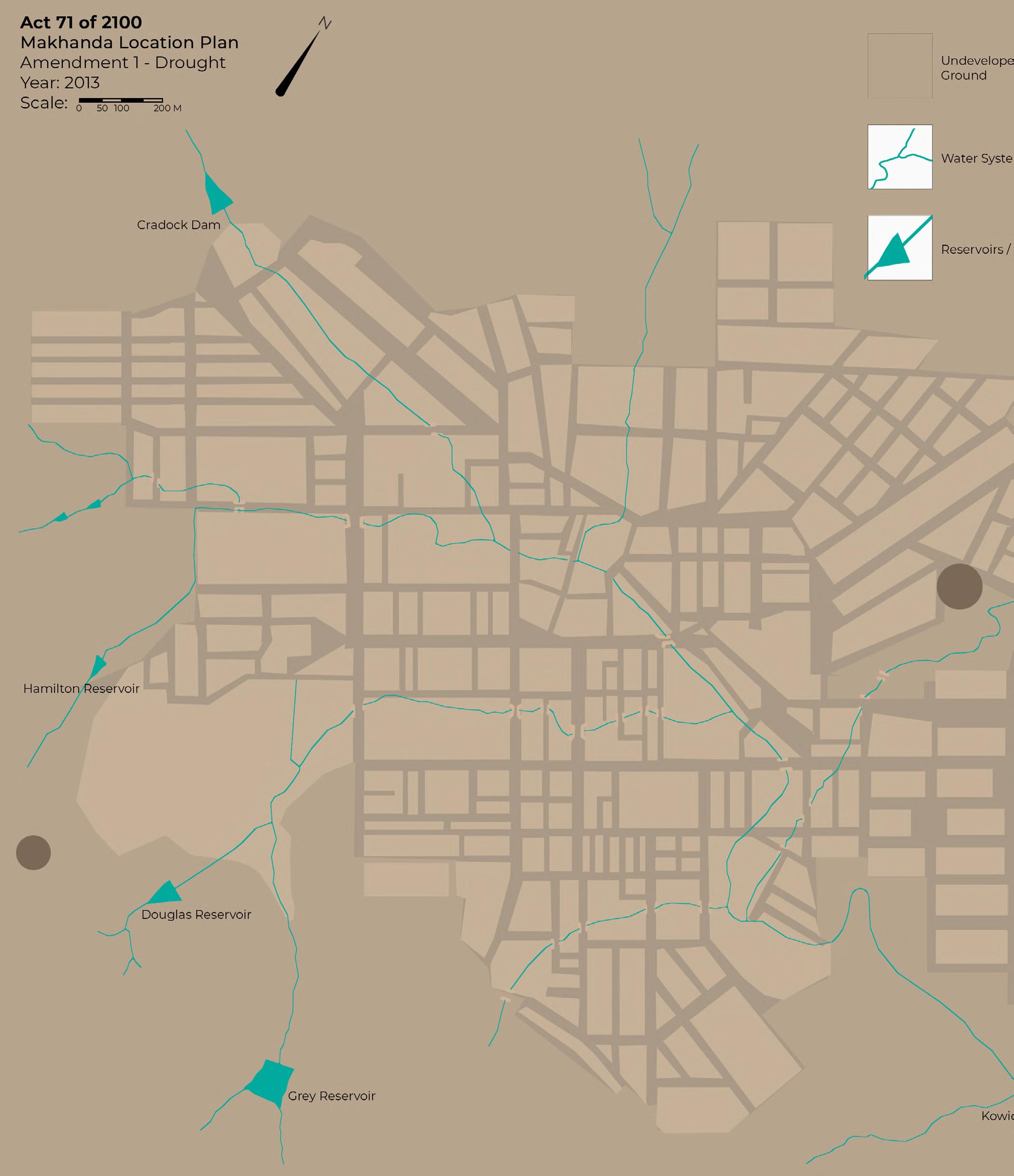

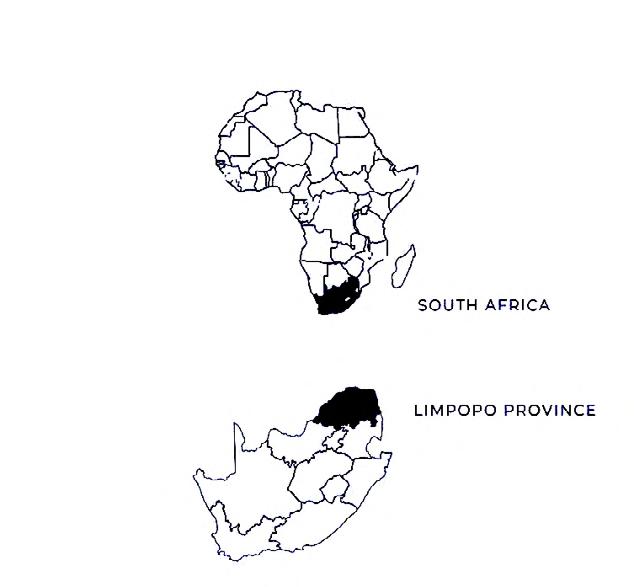

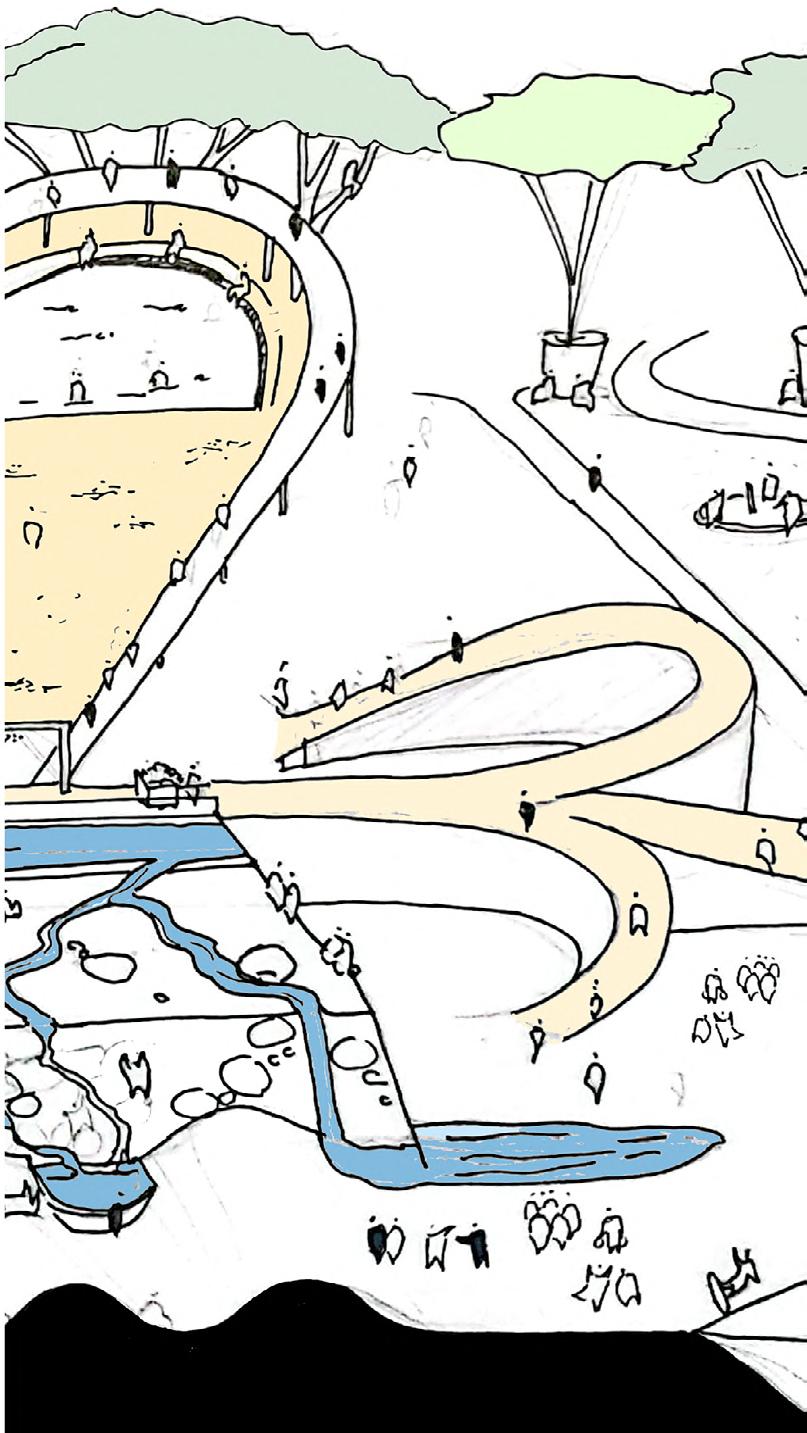

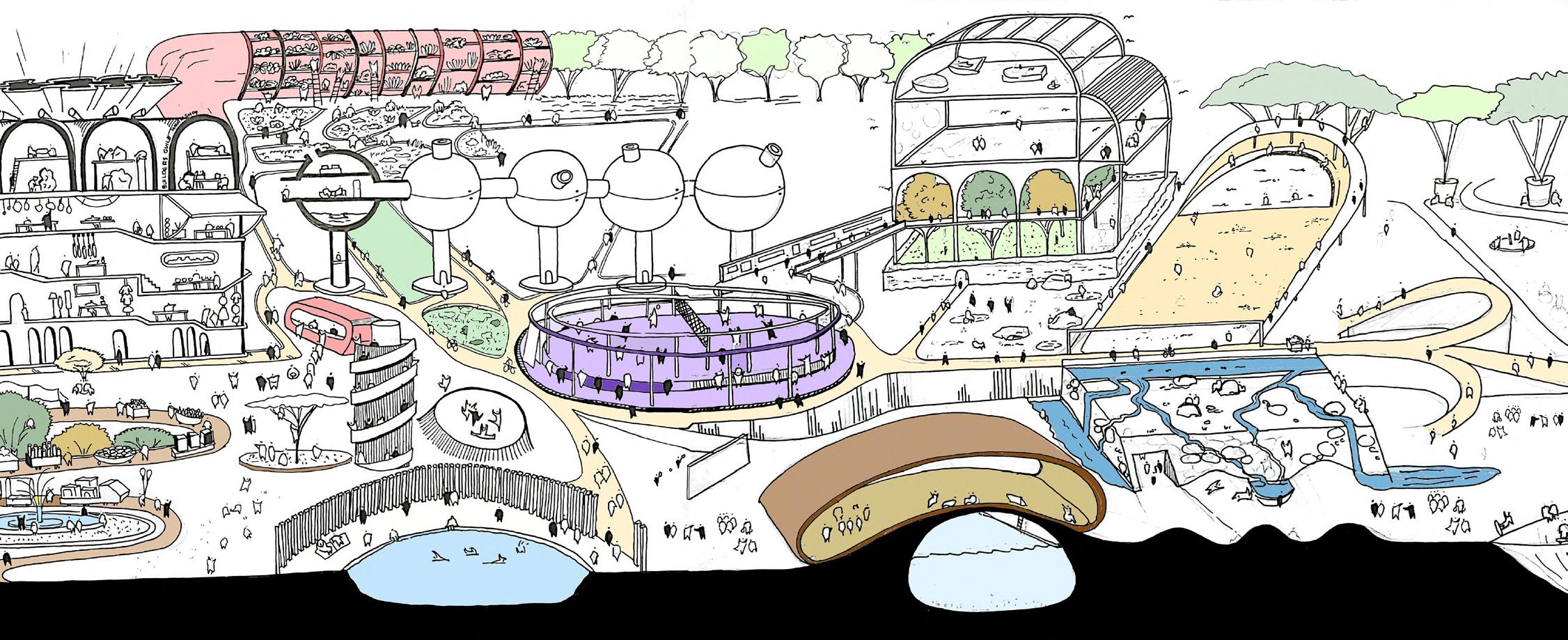

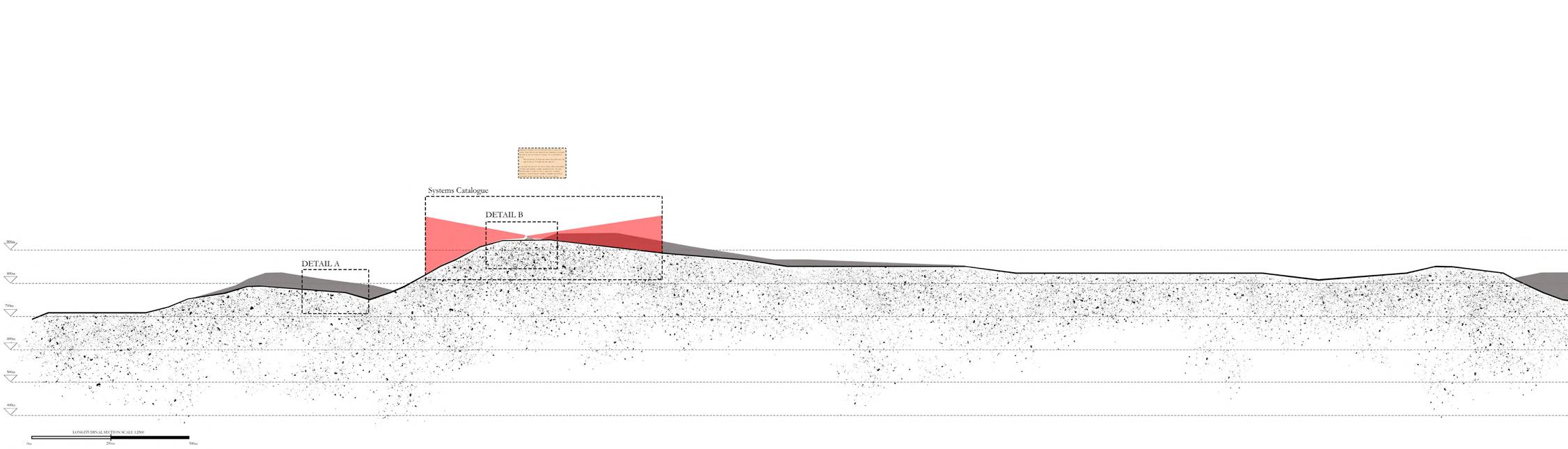

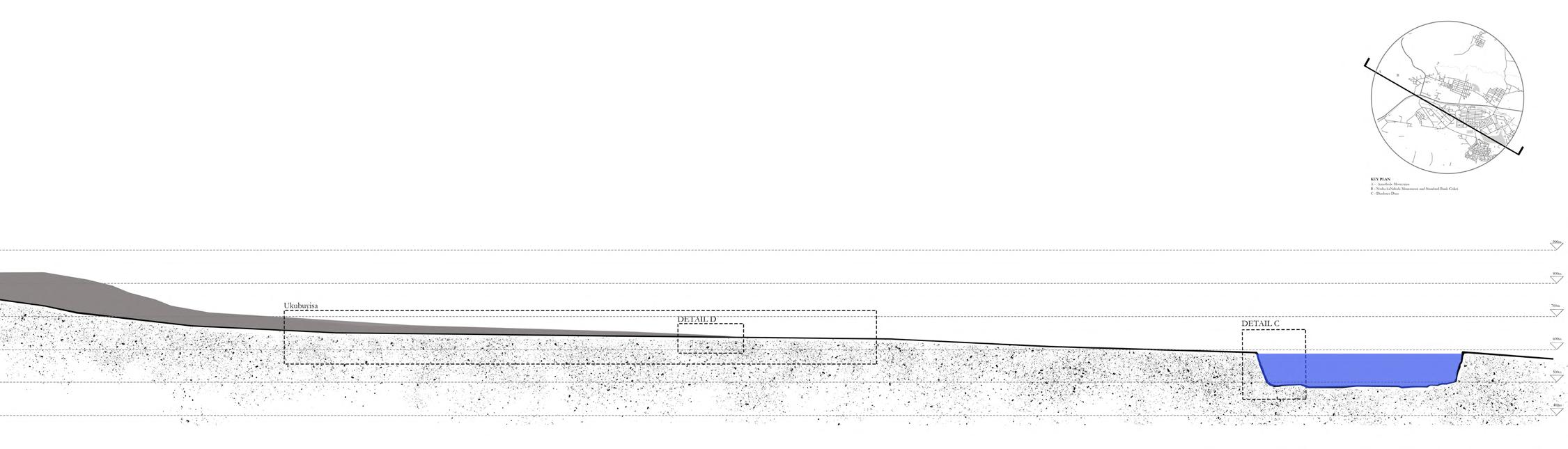

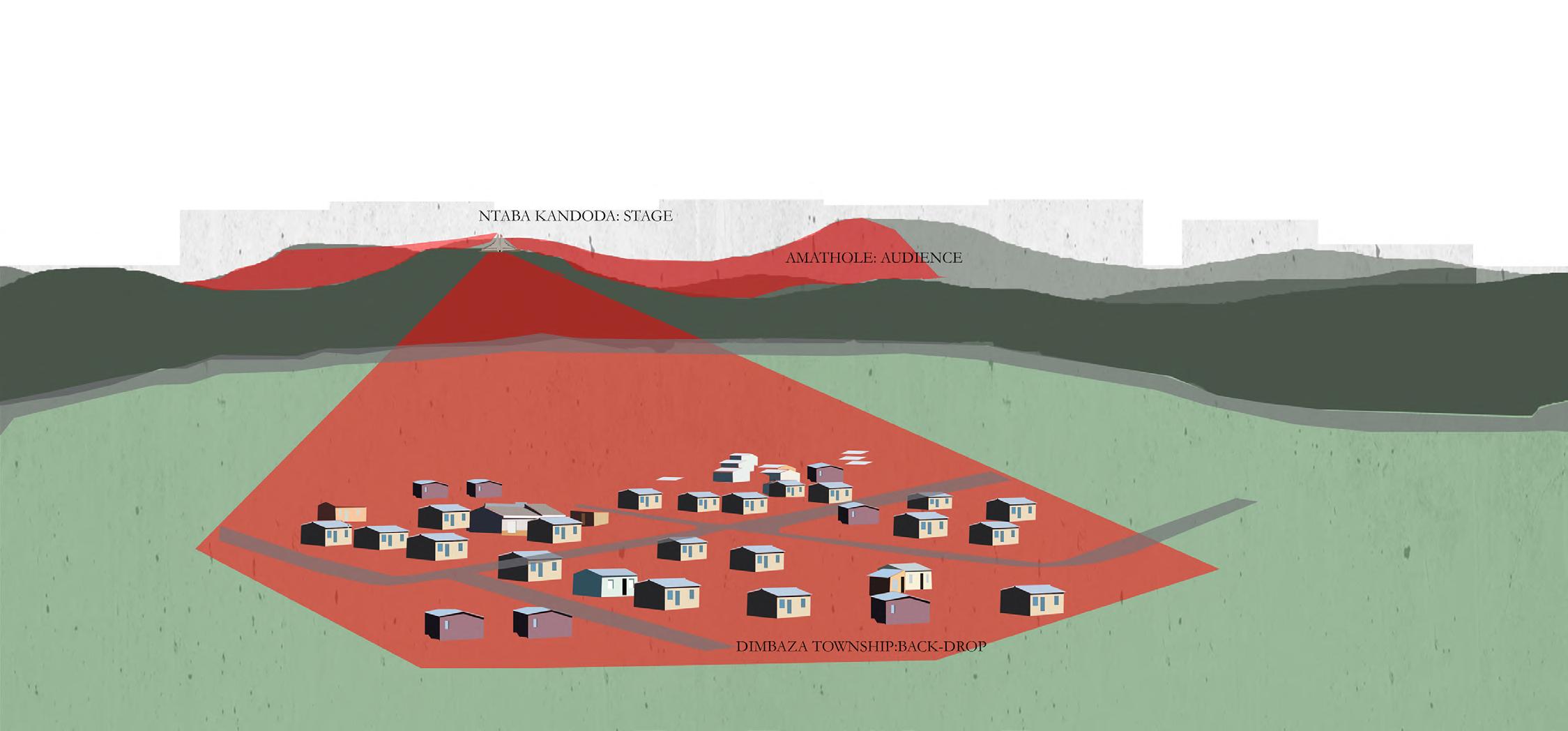

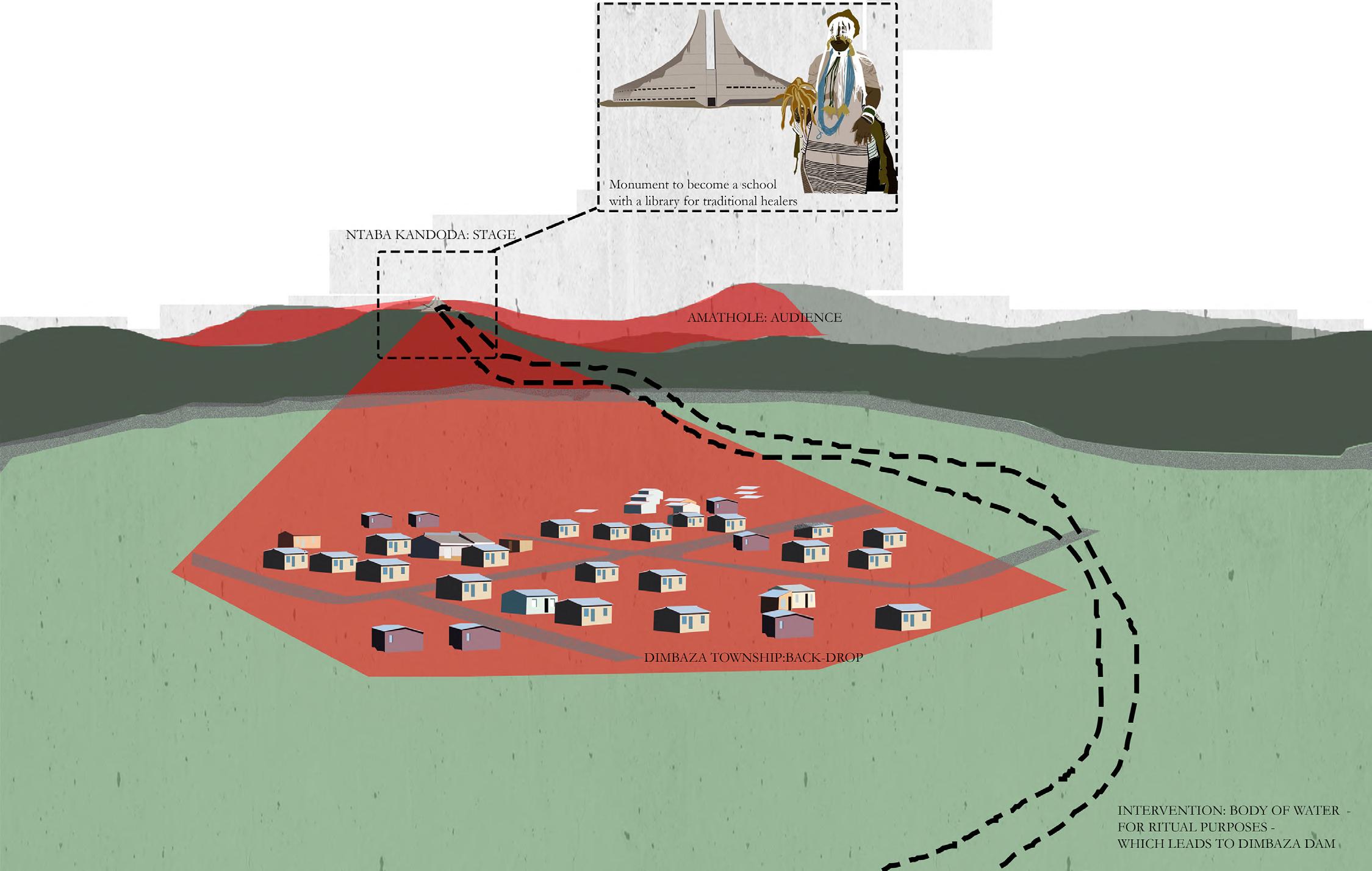

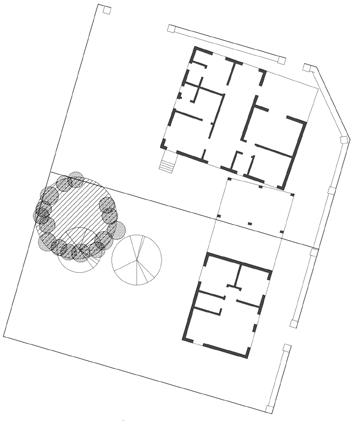

In 2022, the Unit delved into the empty land myth (or what is known in South Africa as the ‘second Hamite myth’) on a site of past and present contestations between the Xhosa and the British, namely Makhanda (formerly known as Grahamstown) in the most rural of all South African provinces, the Eastern Cape. As cartographers, archaeologists, and conjurers, students proposed revised possibilities for this terrain through the typology of a Bank. Using the Unit’s primary methods and mediums of map-making, the Unit conducted its research across four scales at different stages of the design research process and students were required to produce work of a high resolution through skilled technification tools that include assembly, phasing, and simulation.

This year’s theme concluded the final part of our 3-year thematic structure, where we moved from Religion, to Violence and then Currency – the three primary pillars of state formation.

In the upcoming years - whether through academia or practice - the other critical pillars of state formation, namely, administration, law, and media, will be our primary themes of investigation.

References:

1. Anwar, F., 2021. The Funambulist Correspondents 13 /// Land Theft as Colonial Legacy in Pakistan [online] THE FUNAMBULIST MAGAZINE. Available at: <https://thefunambulist.net/ editorials/the-funambulist-correspondents13-land-theft-as-colonial-legacy-in-pakistan> [Accessed 10 August 2021].

2. Bhandar, B., 2020. Lost property: the continuing violence of improvement - Architectural Review. [online] Architectural Review. Available at: <https://www.architectural-review.com/ essays/lost-property-the-continuing-violenceof-improvement> [Accessed 17 August 2021].

3. Camissamuseum.co.za. unknown. Terra NulliusThe Lie about an Empty Land - Camissa Museum. [online] Available at: <https://camissamuseum. co.za/index.php/orientation/our-foundationpeople-roots/terra-nullius-the-lie-about-anempty-land> [Accessed 18 August 2021].

4. Chimurenga Chronic, 2018. The Idea of a Borderless World. pp.4-5.

5. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2021. dispossession [online] Available at: <https://dictionary. cambridge.org/dictionary/english/ dispossession> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

6. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2021. ground. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary.cambridge. org/dictionary/english/ground> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

7. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2021. land. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary.cambridge. org/dictionary/english/land> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

8. Dictionary.cambridge.org. 2021. unsettling. [online] Available at: <https://dictionary. cambridge.org/dictionary/english/unsettling> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

9. En.wikipedia.org. 2021. Terra nullius - Wikipedia [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Terra_nullius> [Accessed 17 August 2021].

10. Koolhaas, R., Westcott, J., Petermann, S. and Trüby, S., 2014. elements of architecture. Los Angeles: Taschen, pp.4-8.

production (Sakai, 2010:455). This referred to Europeans only as they were seen to be the only ones with this capacity.

3 Anthropos is a term reserved for a lesser kind of humanity who participate only in empirical knowledge-production, i.e., although they are able to produce knowledge, they were deemed incapable of reflecting upon and criticizing their modus operandi (Sakai, 2010:455).

4 Terra nullius is a Latin expression meaning “nobody’s land” (terra nullius – Wikipedia, 2021). Note the use of the word ‘land’ in the translation of the expression. Mirjana Ristic (2018:34-38) offers a practice-based vocabulary to this spatial classification, and refers to it as ‘spatiocide’, where entire landscapes are targeted with the aim of reverting it back to mere land by wiping out origin communities (Ristic, 2018:34-38).

11. Mignolo, W., 2015. Sylvia Wynter: What Does It Mean to Be Human?. In: K. McKittrick, ed., Sylvia Wynter on Being Human as Praxis Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp.106-123.

12. Rekhta.org.2021.jaahil. [online] Available at: <https://www.rekhta.org/urdudictionary?keyw ord=jaahil&reftype=rweb> [Accessed 6 August 2021].

13. Ristic, M., 2018. Architecture, Urban Space and War: The Destruction and Reconstruction of Sarajevo [Place of publication not identified]:

Switzerland, pp.29, 34-38.

14. Sahistory.org.za. unknown. The Empty Land Myth | South African History Online. [online] Available at: <https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/ empty-land-myth> [Accessed 18 August 2021].

15. Sakai, N., 2010. Theory and Asian humanity: on the question of humanitas and anthropos. In: Postcolonial Studies, 13th ed. London: Routledge, p.455.

‘FRONTIER COUNTRY’

The Invention of Land

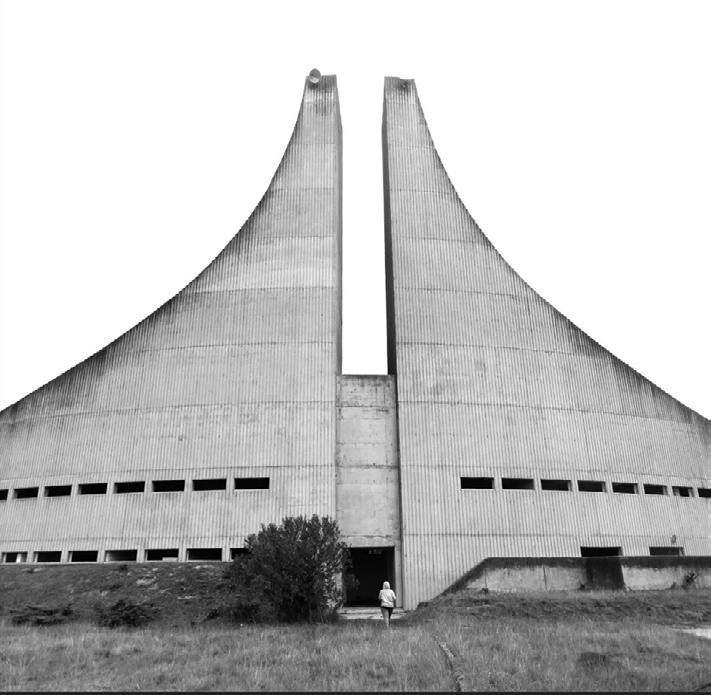

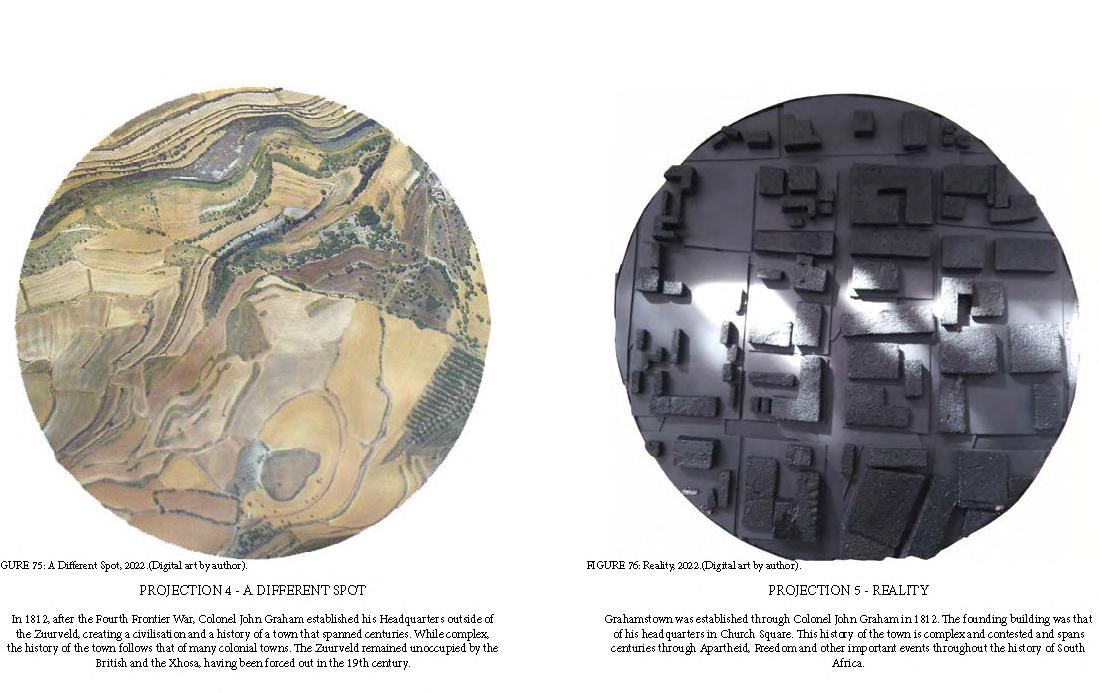

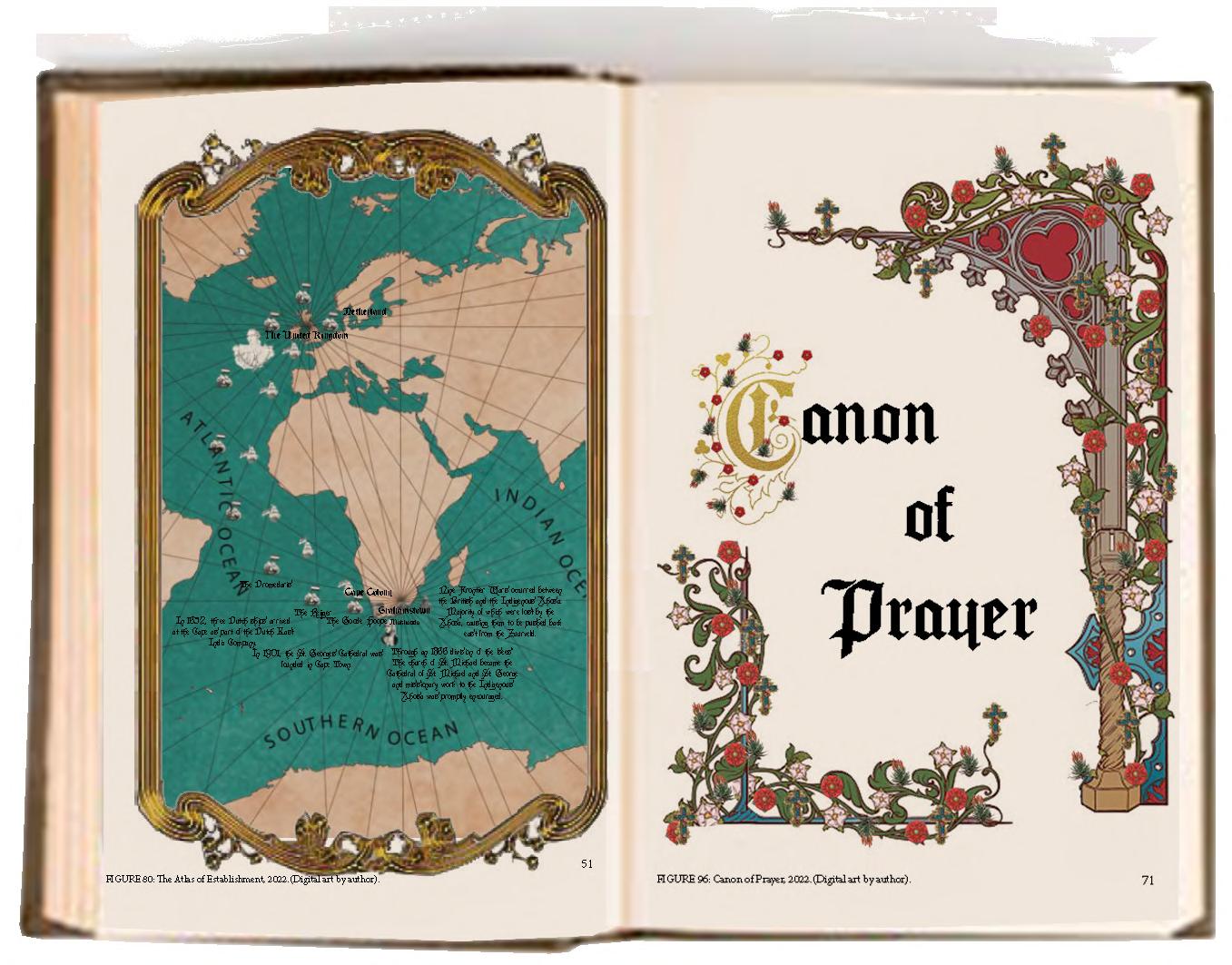

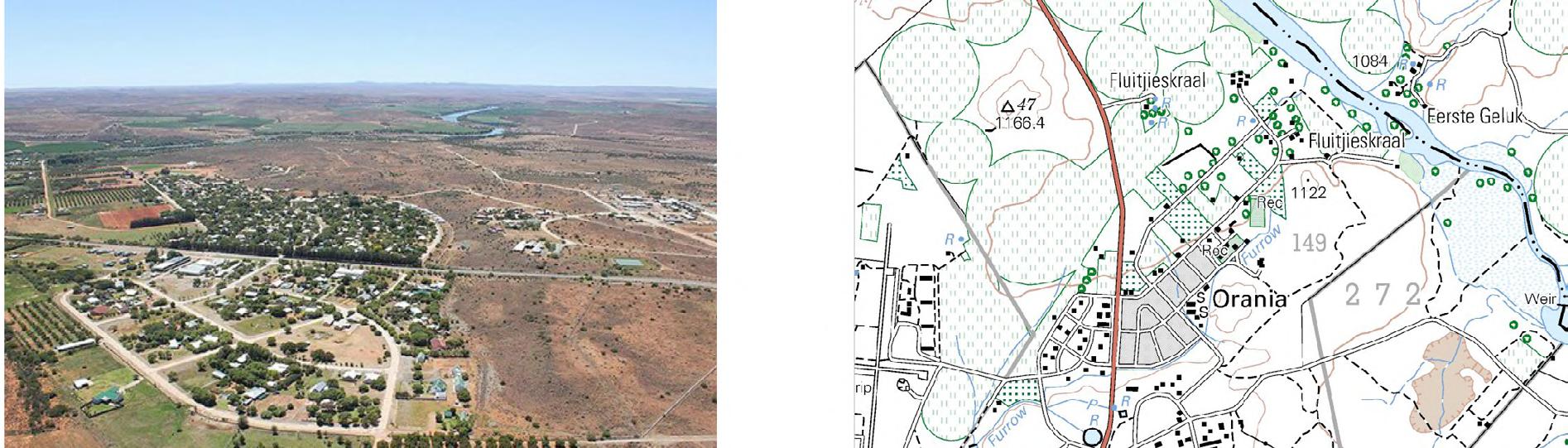

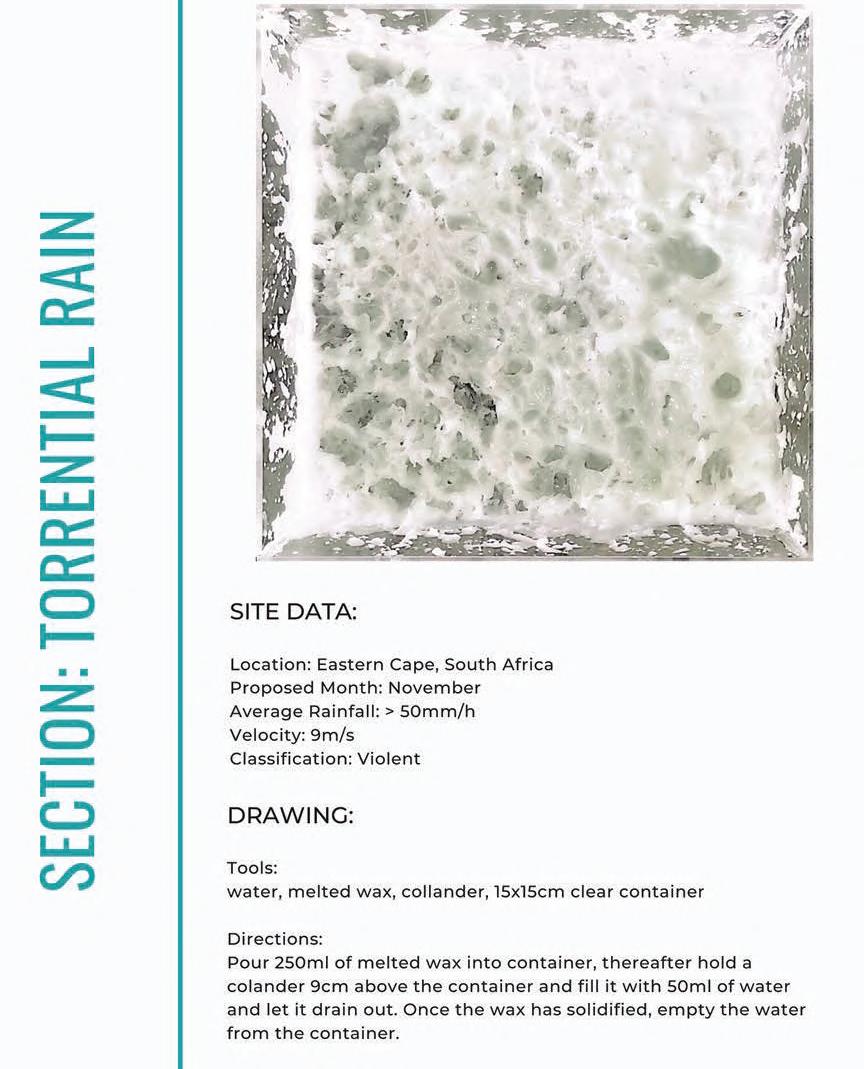

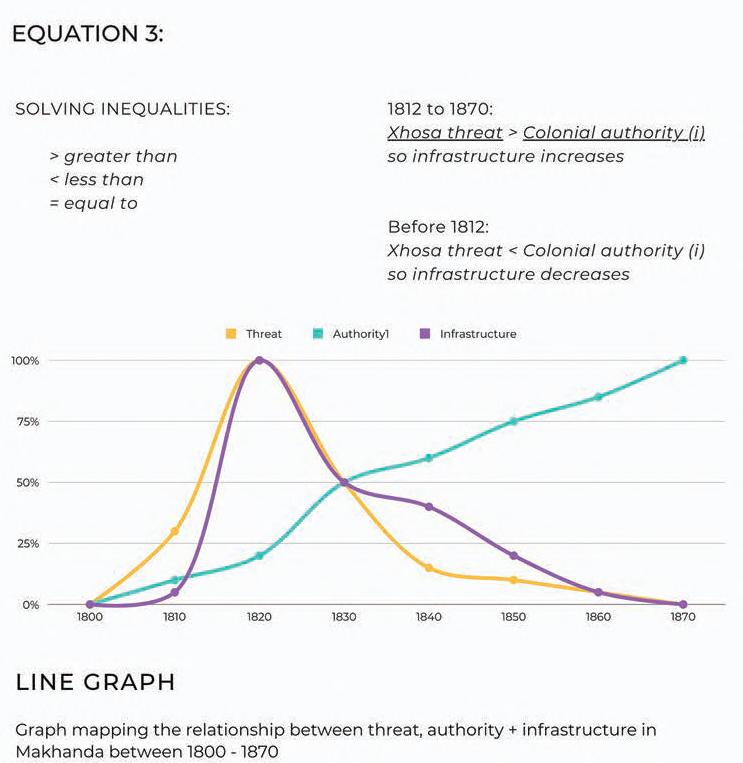

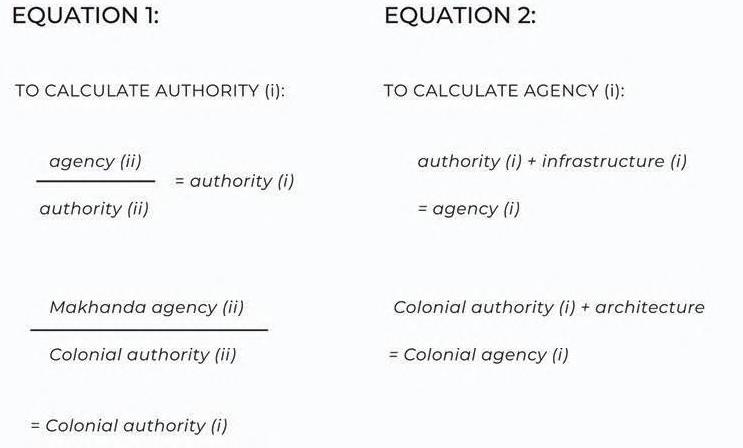

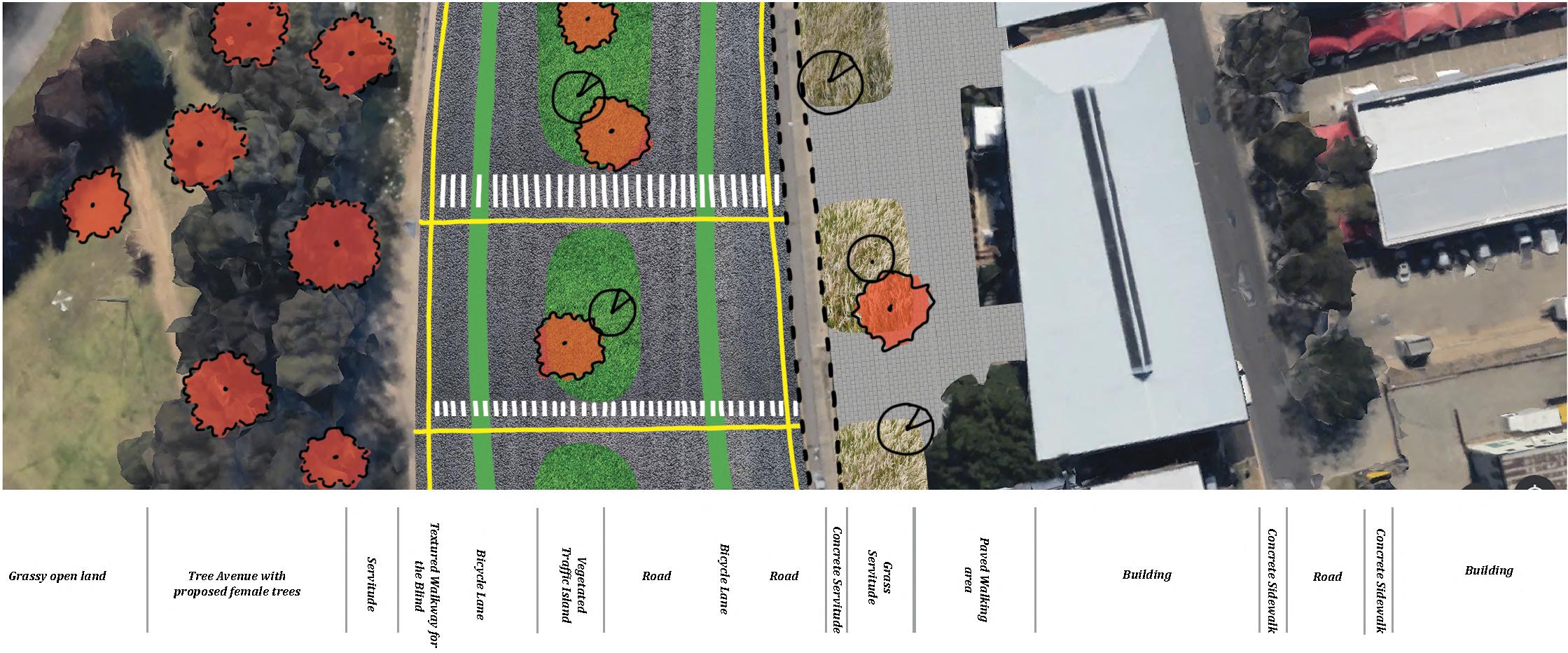

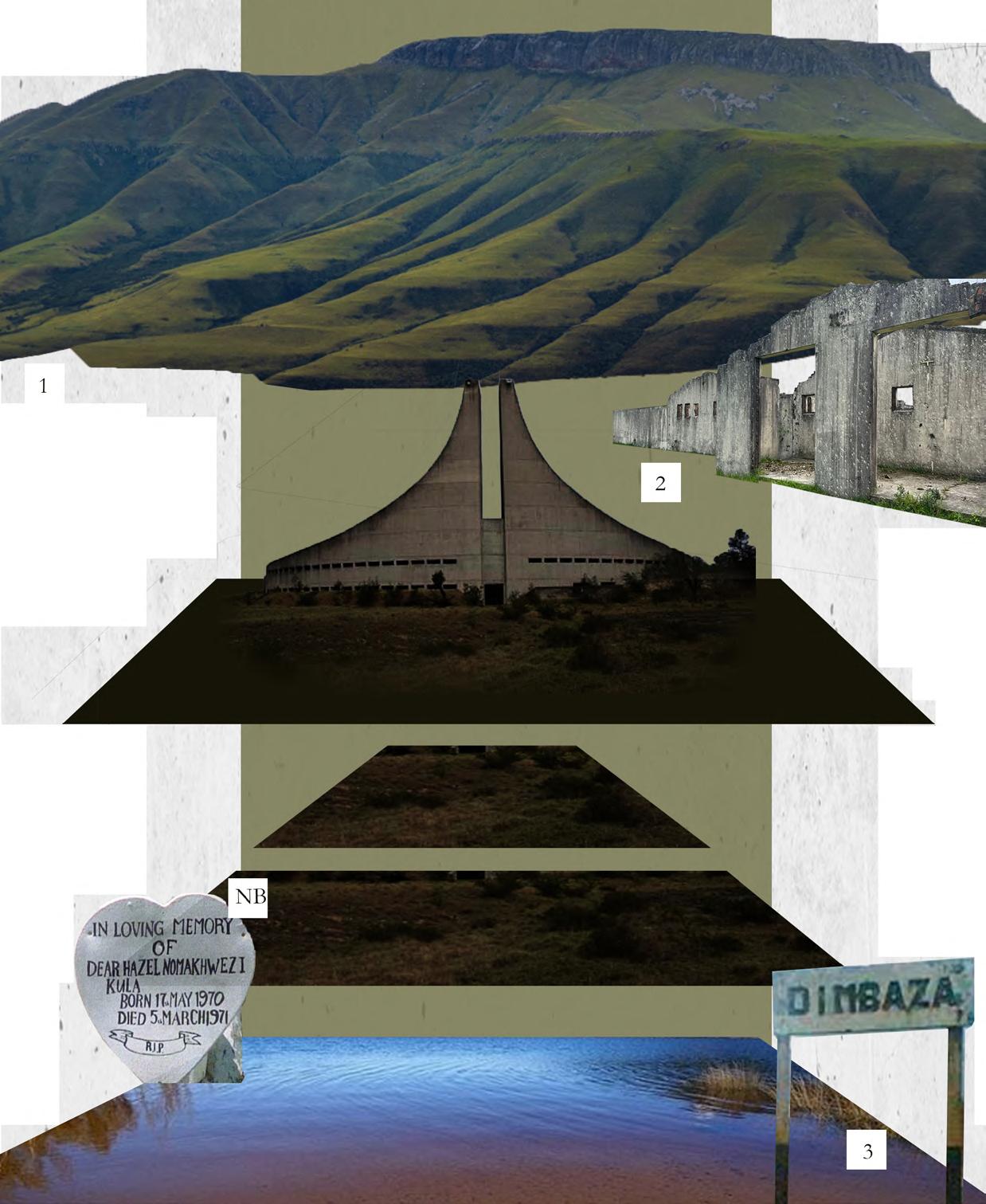

This year, students investigated the intersection between architecture and currency through the invention of ground as land/property. The studio delved into the empty land myth (known in South Africa as the ‘second Hamite myth’) in the case study town of Makhanda, which was formerly known as Grahamstown and is still referred to by some as ‘Frontier Country’.

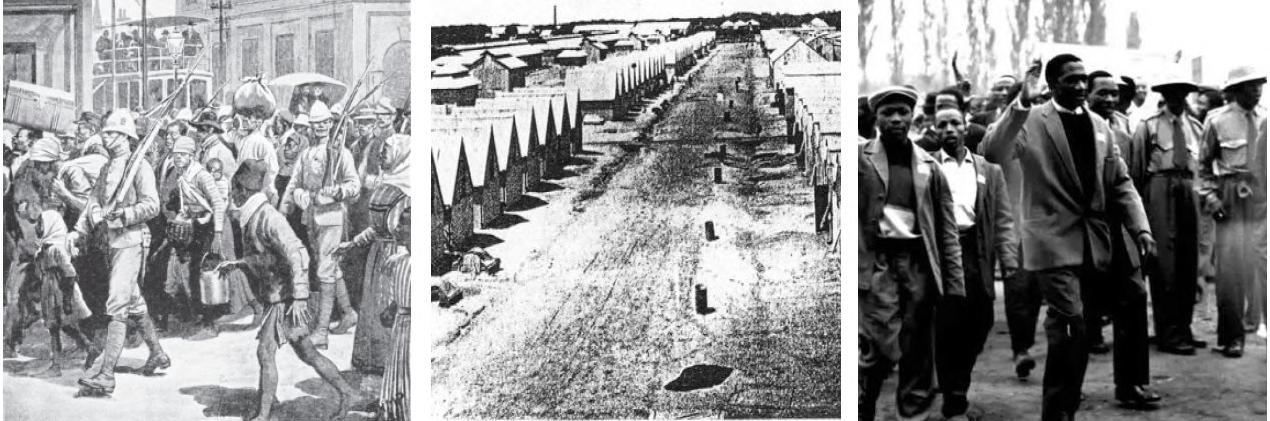

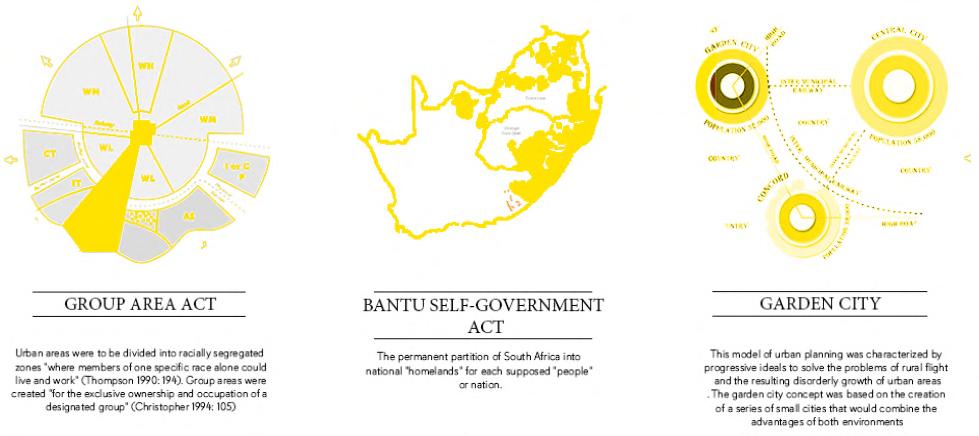

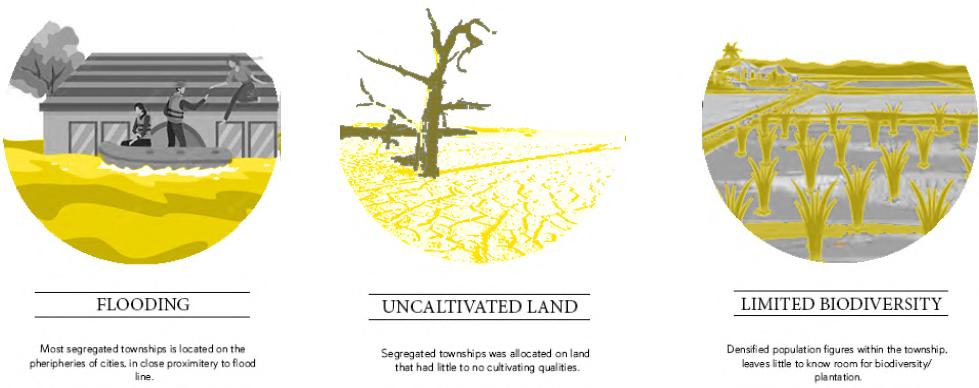

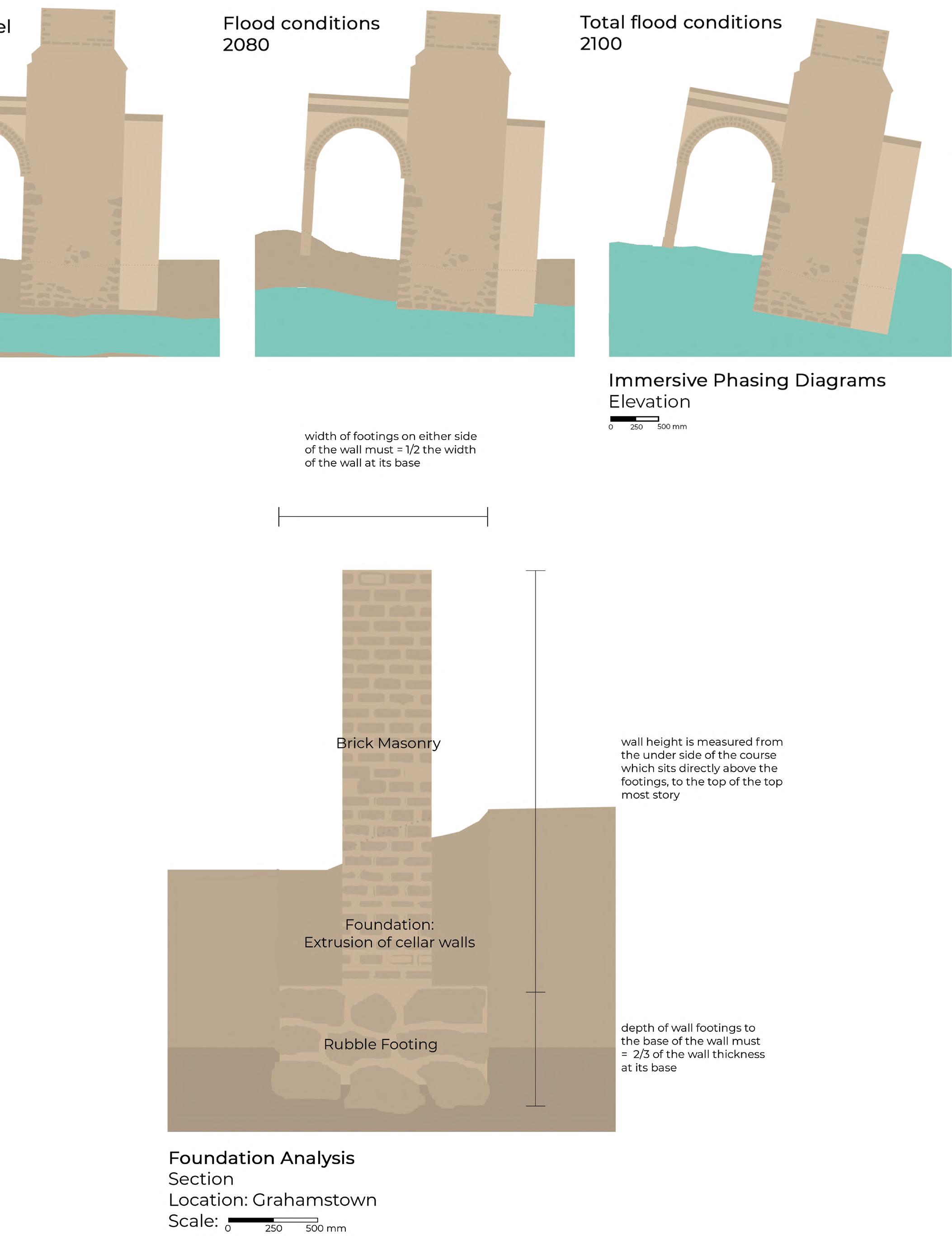

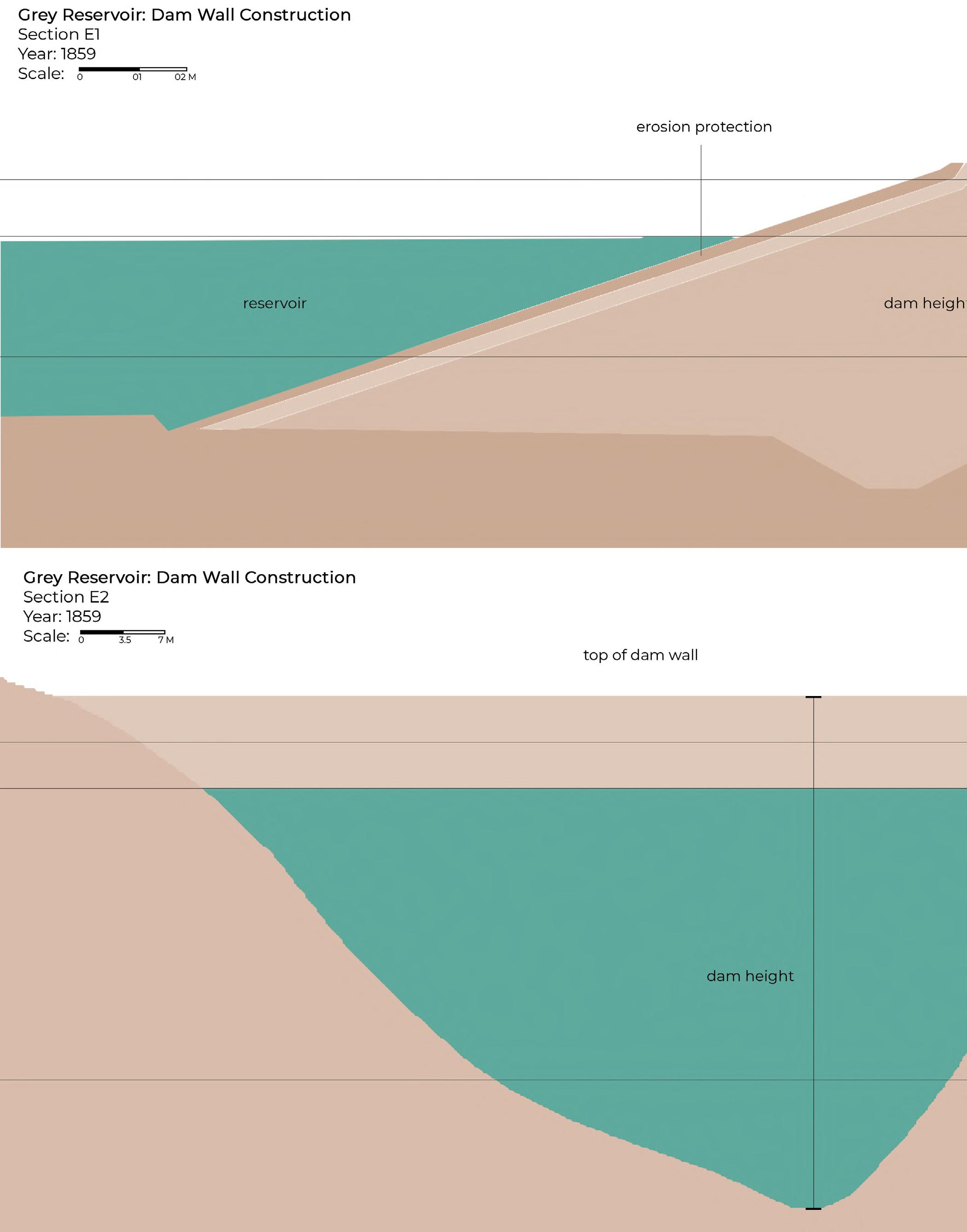

Located in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, Makhanda sits as a contested site between the Xhosa and the British and has the status as the country’s first settlement outpost, established by the 1820s British colonial settlers. Its overriding terra nullius settlement strategy informed the trajectory of land ownership and settlement formation across South Africa as it was treated as the testing ground for the land strategy that was to be rolled out at the national scale. What this strategy entailed was primarily four-fold. The one arm of the strategy was about erasing any evidence of indigenous life (i.e., the Xhosa) through what they called the Scorched Earth Policy. The Xhosa’s crops were destroyed, cattle confiscated, and homes burnt, leading to their mass displacement.

The next arm was about dispossession by compromising the currency of the Xhosa: cattle. They stole and killed their cattle, and built a gaol to imprison any Xhosa that were found attempting to steal back their cows. In the span of a year, cow theft numbers increased from 2,000 at the beginning of 1818 to 23,000 by the end.

The next arm of the strategy was to build a church. In the 16th century, a town was recognised as a city by the British Crown if it had a diocesan cathedral within its limits. This association was established when Henry VIII founded new dioceses in six English towns and also granted them

city status. The Cathedral of St. Michael and St. George was the first building to be erected in Grahamstown, and its presence allowed it to be declared a British city.

The final arm of the strategy depended on the one highlighted above, where due to the presence of a church, a city centre became possible, as the church was able to be utilized for religious worship, education, trading, and banking. This allowed the British to hastily move in over 5,000 settlers in an attempt to orchestrate a premature/ dummy settlement, thereby making a case for defence and fortification for who they could now frame as ‘innocent women and children’. The rapid increase in volume of British settlers led to an eighteen month period of rapid settlement construction (particularly homes), and roughly twenty forts (most of which were built over a span of five years) throughout the Eastern Cape province. The region remains the most fortified in all of South Africa, and through these strategies, the British cemented definitions of territory and ownership in the region, repositioning the terrain as a regulated and tradeable stock.

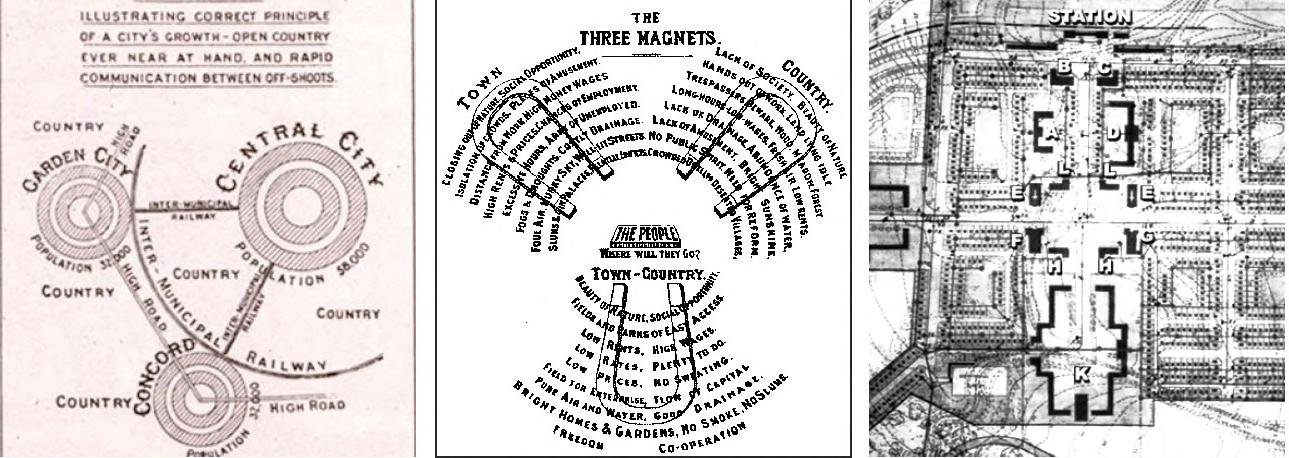

This year, students were asked to propose revised possibilities for a contested terrain of their choice (which could include Makhanda) through the typological conception of a Bank, or: a container through which to question and reimagine meanings of ‘currency’ and ‘trade’. Banks are, at their core, a mediating place of storage, and a “juncture of past, present, and future in anticipation of imminent conditions” (Treherne, 2022). Existing bank typologies range from blood banks to prisons; but also graveyards to islands; piggy banks to private art galleries; but also continents (i.e., land mass containing smaller territorialized land masses, i.e., countries) to countries (i.e., smaller land masses containing owned land zones), etc.

Edifice of Illumination: A Manuscript. TASMIYA CHANDLAY

The Mythmaking Territory of Tours. SESETHU MboNISwENI

Façades of Beauty. NobUHLE NgULUbE

Forgetting Langa. MArILIzE HIggINS

A Manuscript.

SITE: Grahamstown British Settlement, Eastern Cape

Abstract

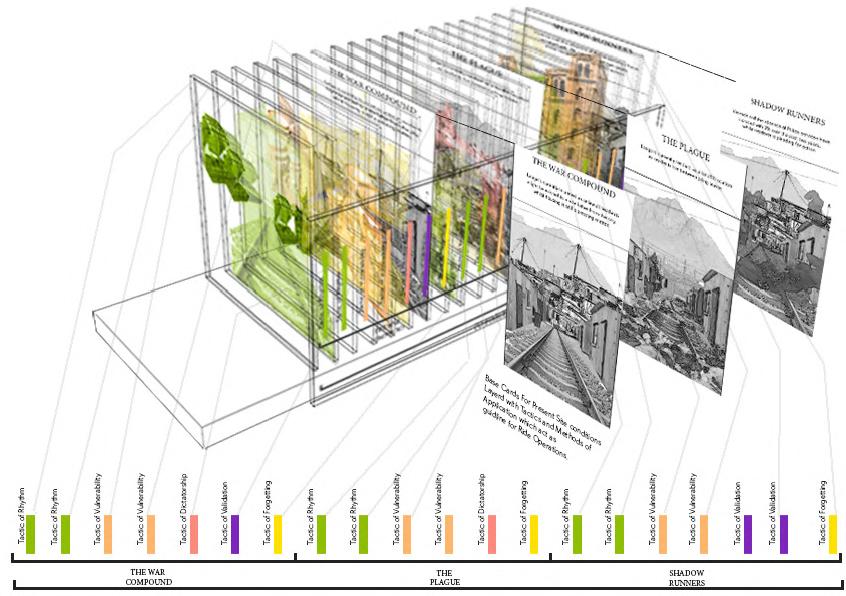

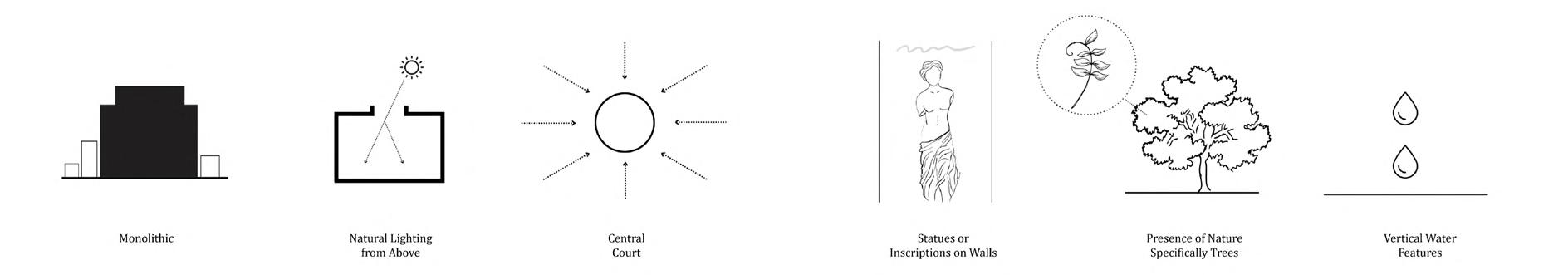

Edifice of Illumination works to uncover/unsettle how institutionalizing spaces mould us at both the scales of the individual and of society, and how bureaucratization operates as a tool of erasure, rescripting, and systematic reprogramming.

The focus of the research is rooted in the institutionalization process of the British settlement town of Makhanda (formerly known as Grahamstown). The study investigates the significant role of the religious institutions of churches, cathedrals, and mission schools in the mission of conquest. Its practices worked to override existing indigenous spatial and cultural infrastructures to assimilate indigenous groups into British cultural and religious practices as a hegemony. With the prime conversion device being that of Christianity, the establishment of British civic and religious infrastructures functioned to allow forms of British cultural frameworks to be instituted and spatially enforced.

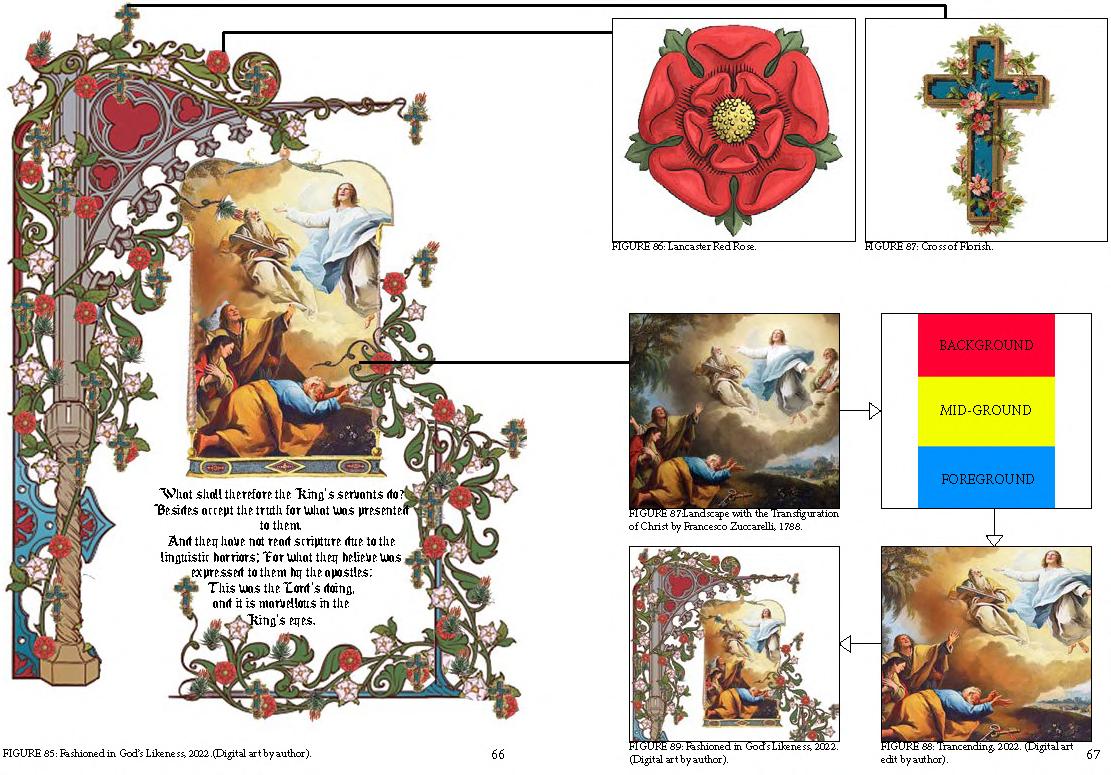

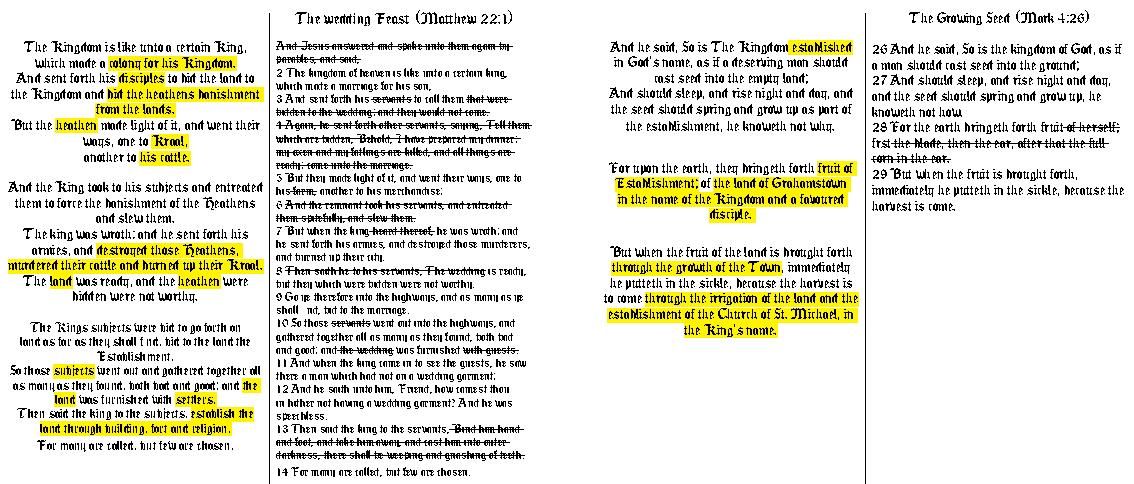

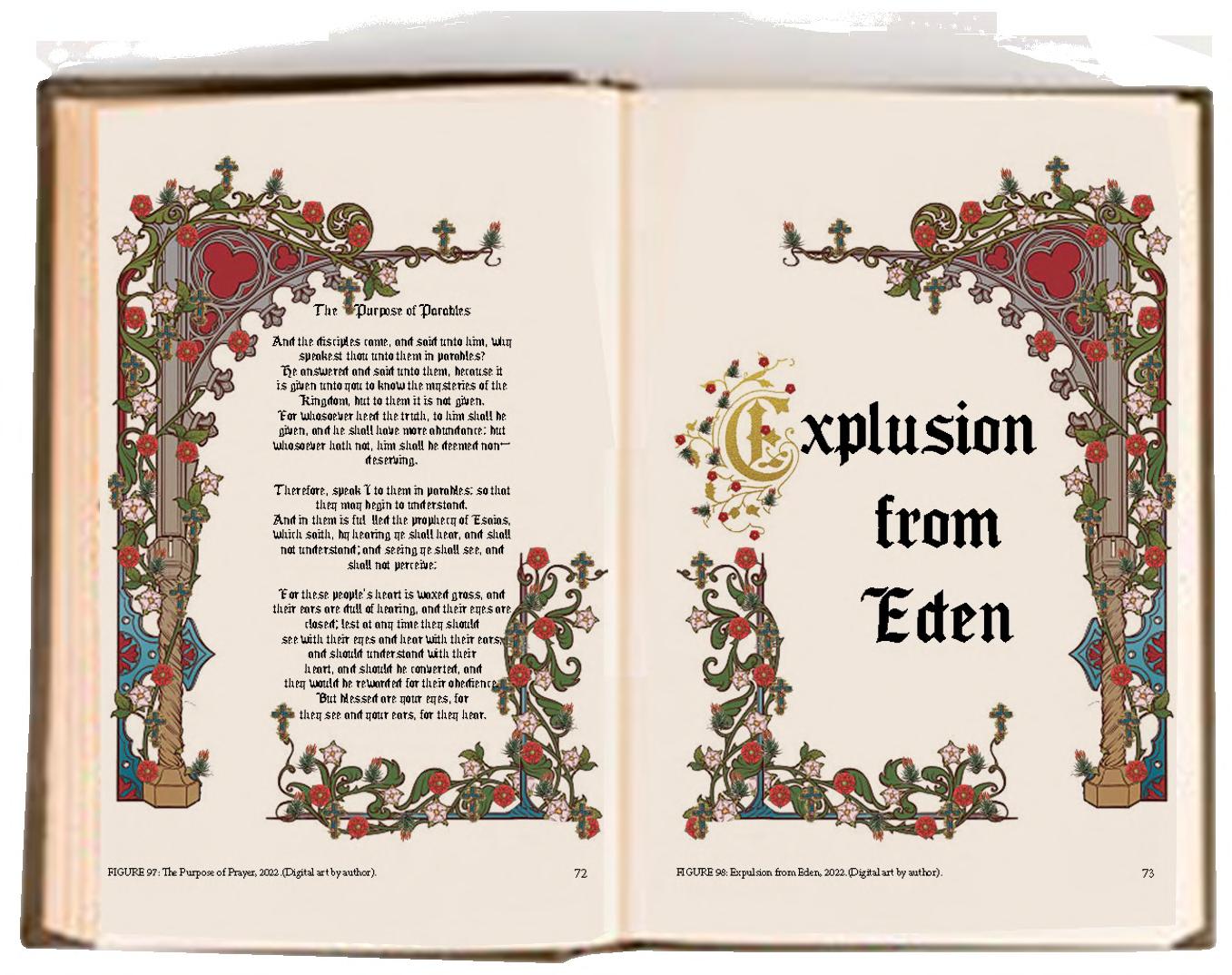

The work proposes an illuminated manuscript as a provocation of extended ways that drawing a building and building a drawing in architectural representation could be explored, as it offers a medium – through prayers, parables, symbolism, image-making, and composition – through which the ideology of spatial institutions can be more accurately blueprinted.

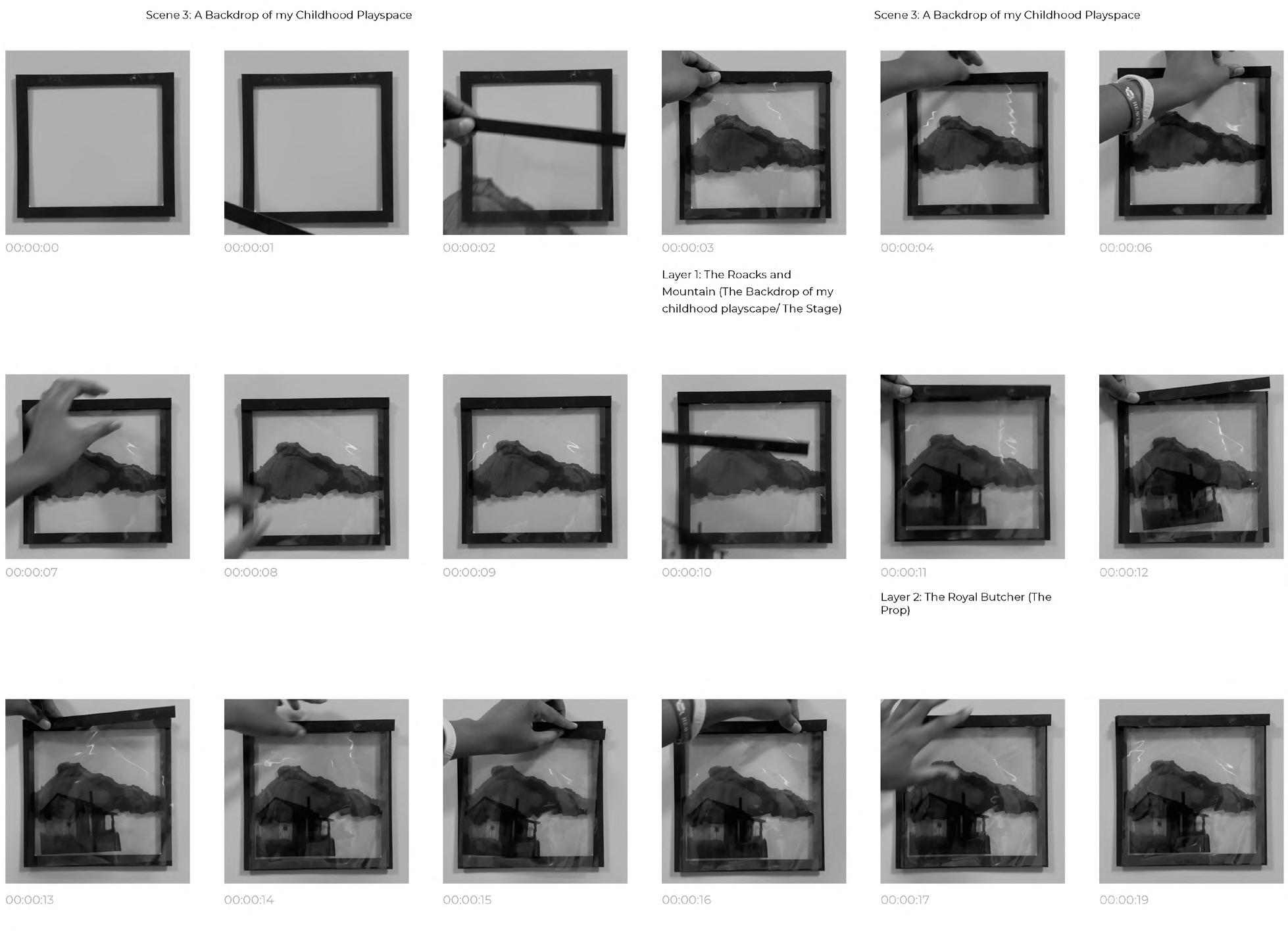

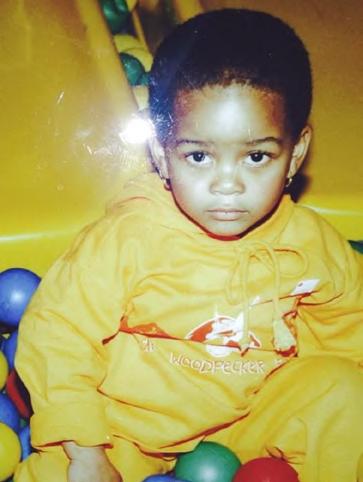

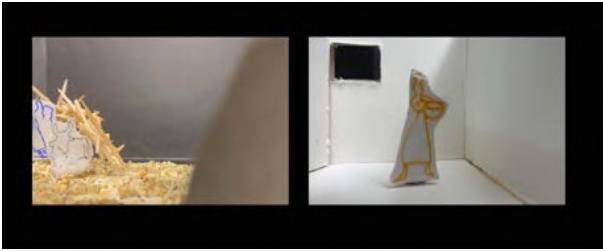

Tasmiya’s research work traverses through scales of institutionalization, from the scale of the body to the scale of the city. Tasmiya’s first project for the year offered a visual lexicon for the anxiety that can arise for students like herself as they undergo a critique session by a design lecturer in academic spaces.

She built a model of a model of herself critting the model of herself. She also produced recordings of her body in a state of tension during that design critique, and projected those alongide her at a later design critique, as a way to present the body as a cartographic tool of measure and documentation. This ability to observe the body in two different states simultaneously allowed the audience to monitor her behavioural norms, and what she refers to as ‘institutional glitching’, or the body and its performances being under a state of institutional tension.

Tasmiya took a keen interest in the instituting practice of rescripting the body, where professionalism and academic performance standards are expected. As such, she introduced her nervous self as separate from her true self.

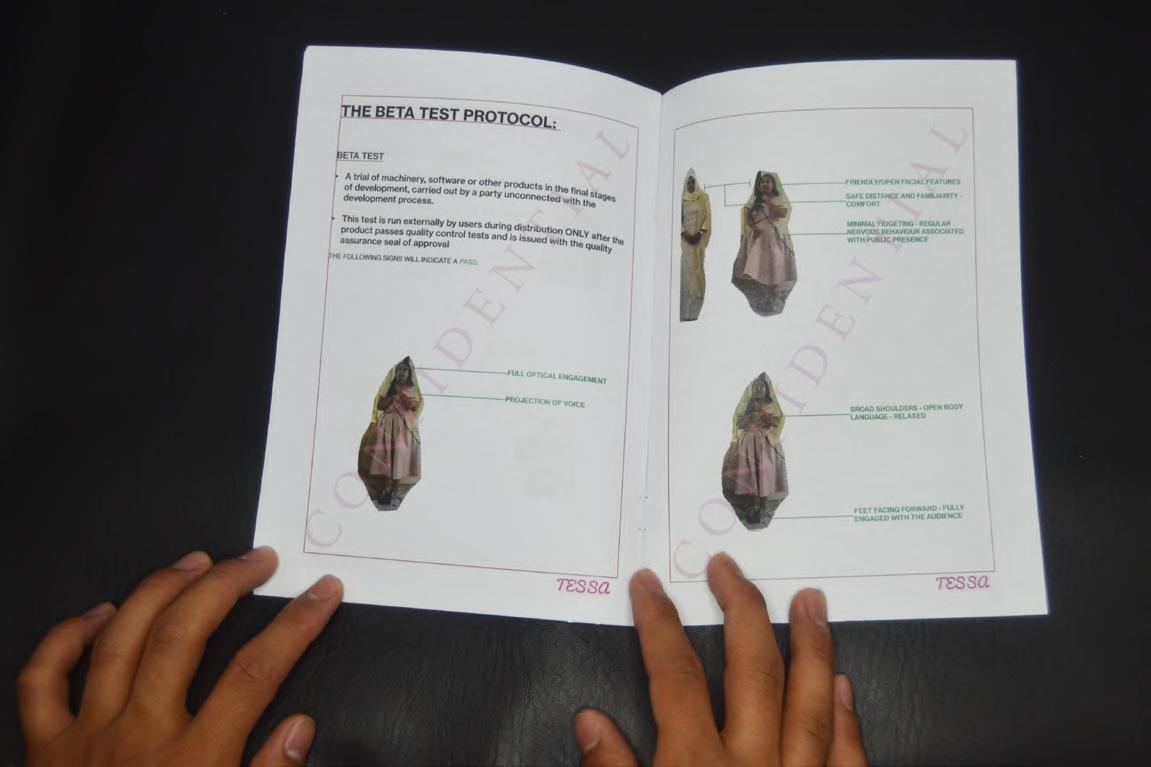

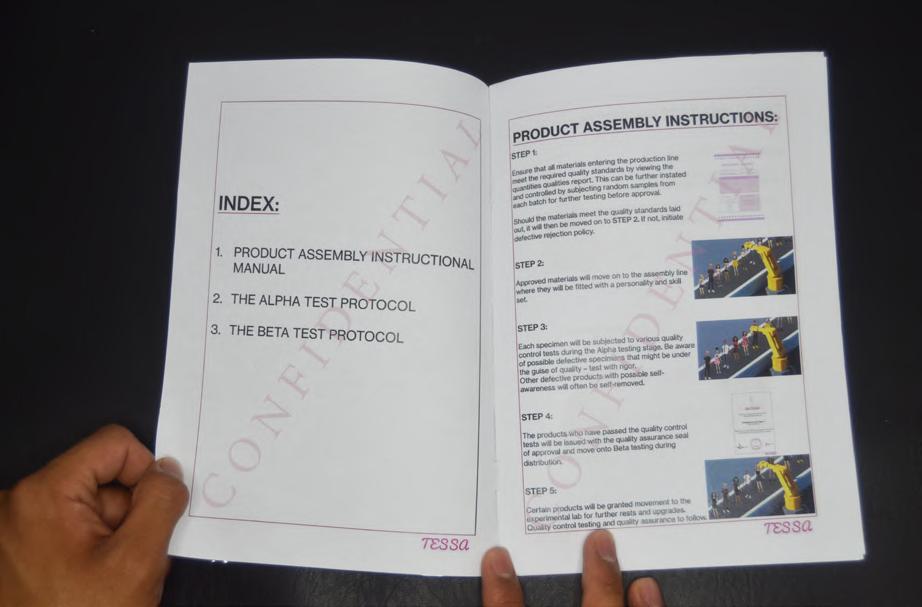

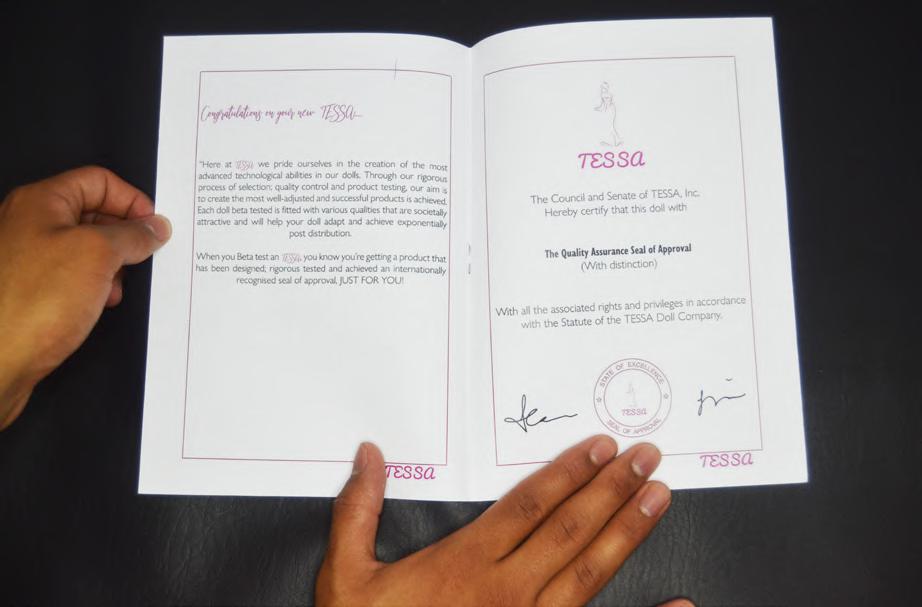

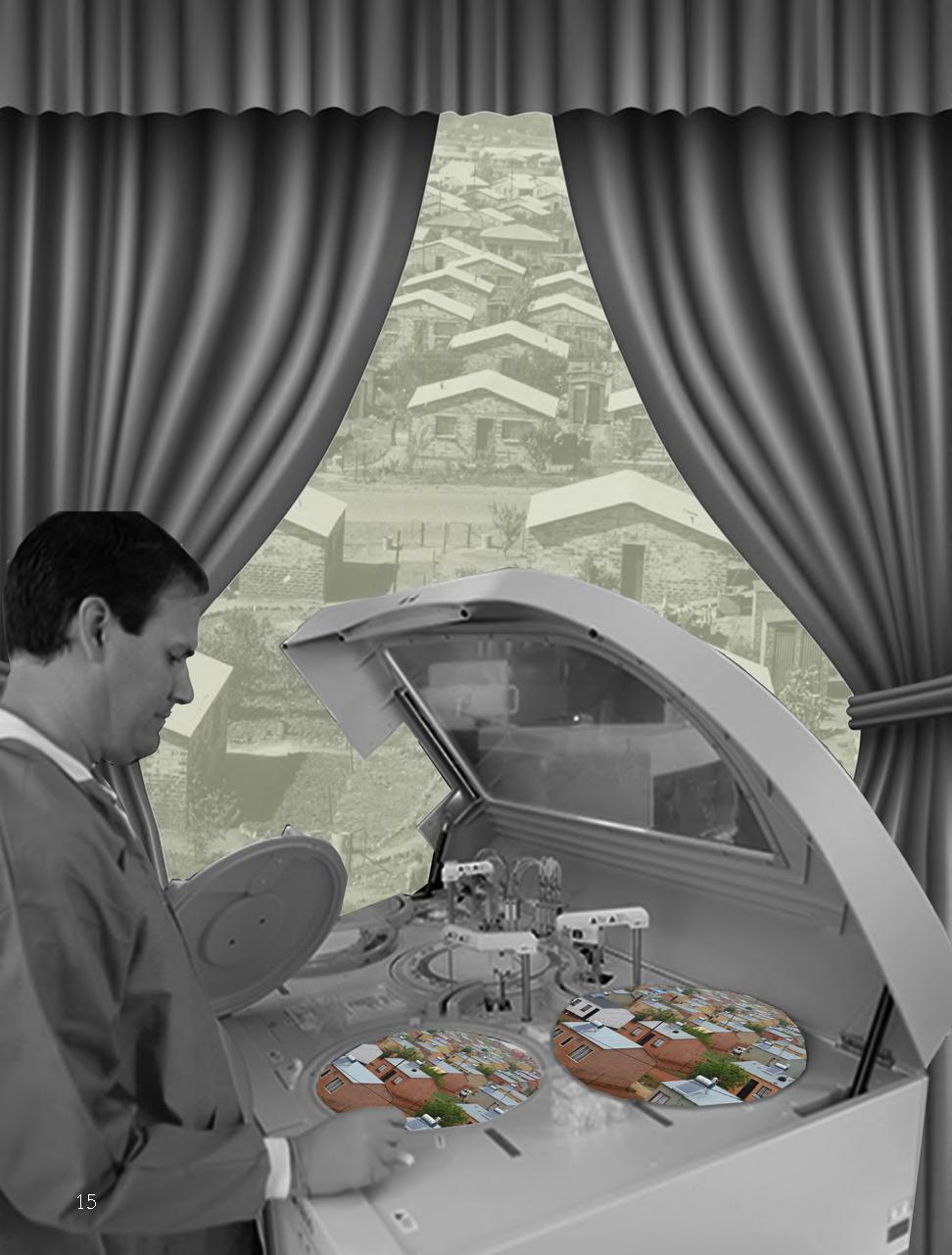

She expanded on her investigation by looking at the university through the typological mechanics of a doll factory that mass produces Tessa dolls (which is what she named the body-rescripted version of herself that is being institutionally transformed). Through this frame, she overlapped its processes, such as product assembly, product testing, alpha and beta models, and quality assurance controls, to unravel the framework that the institutional process moves bodies through.

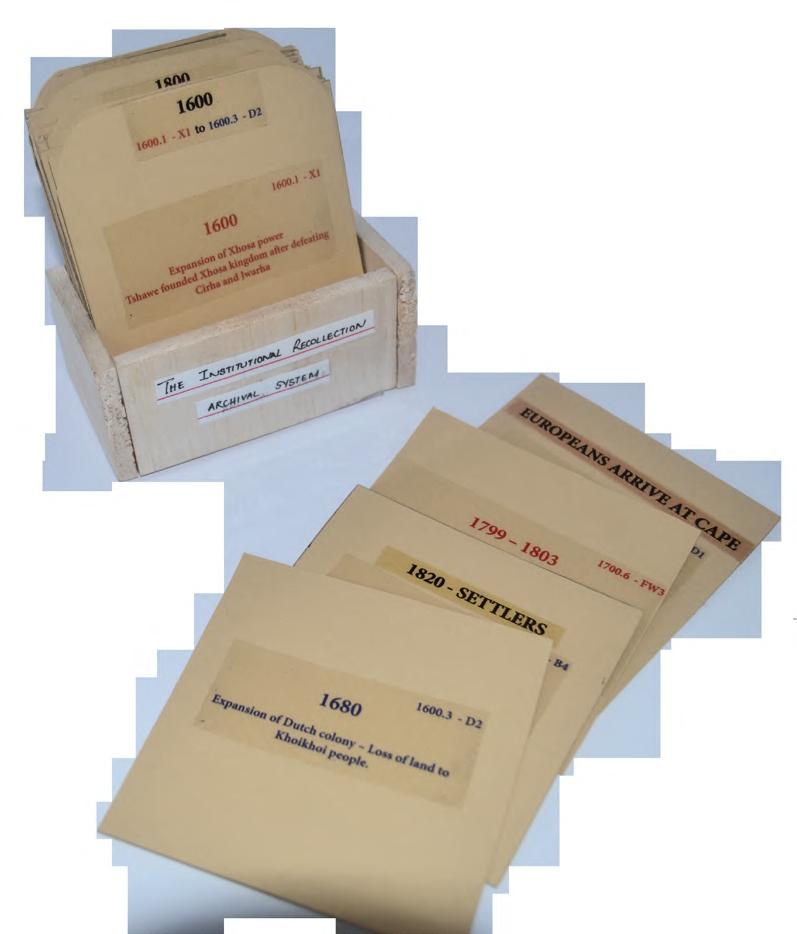

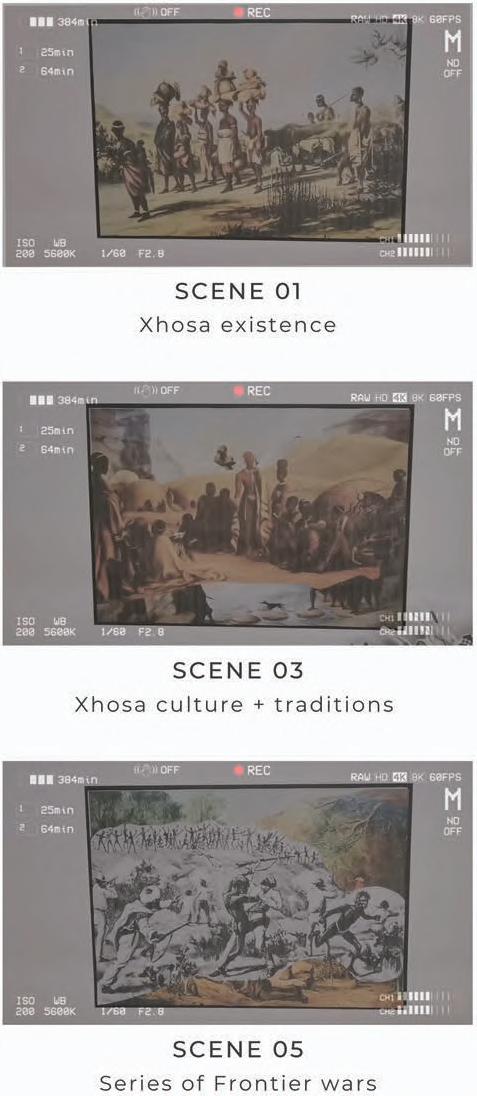

She continually increased her scale of inquiry, as she delved deeper into the greater mechanics of institutionalization. She explored the invention of colonial towns as the practice of institutionalization, and hence, architectural practice as that fundamental practice. She focussed in on the town of Makhanda as her site of study, and established an index for how the Xhosa clan region came to be instituted as the colonial settlement of Grahamstown.

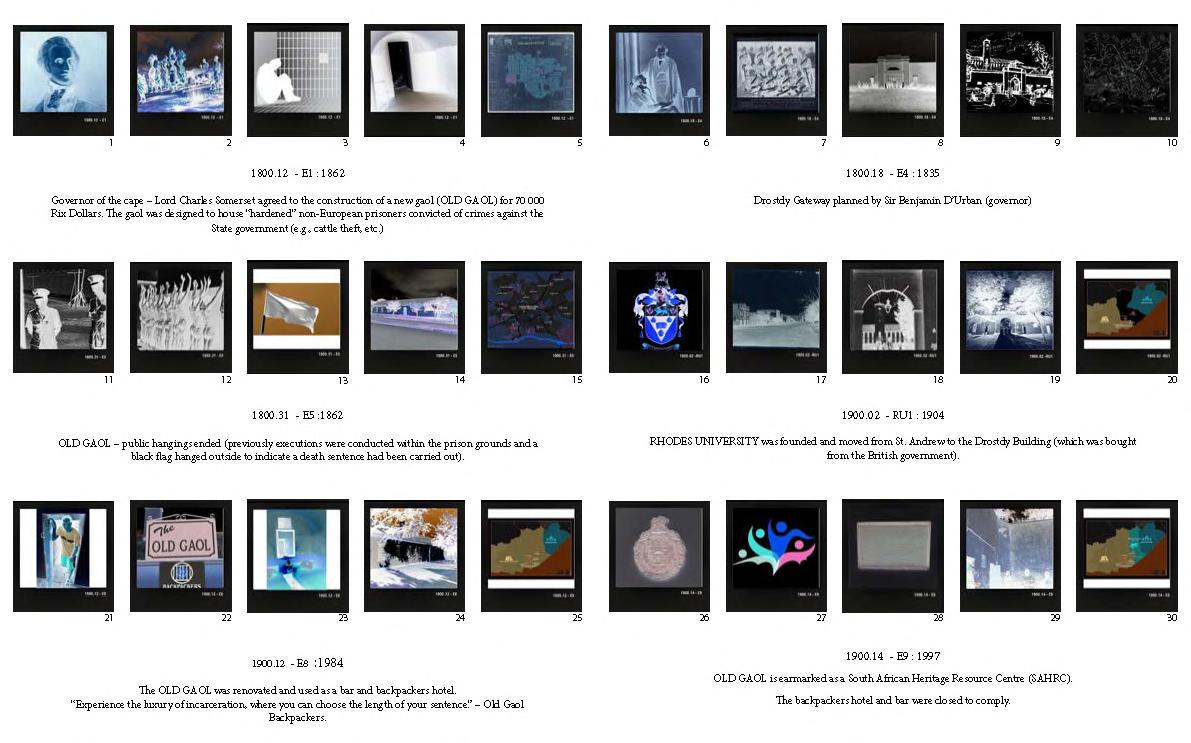

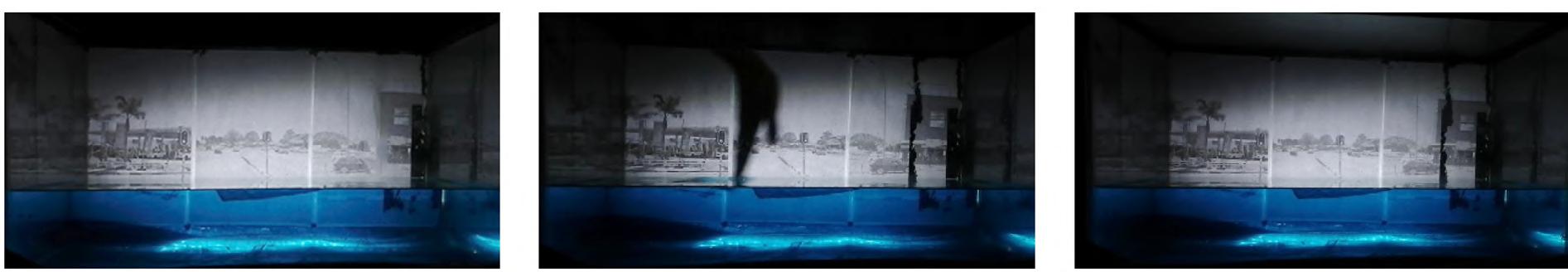

Tasmiya produced photo-negatives of archival depictions of events that founded Grahamstown as a settlement. Engagement with each narrative requires that you use a phone application to produce the original image. In that way, one’s ability to read each narrative in full is greatly disrupted and distorted, and leaves the viewer to move between events as a way to construct alternate versions of events. In this, she shows the vulnerability of institutional indexing, and its ability to rescript or mischaracterize history.

In a series of experiments to expand on the limits and possibilities of insitutional indexing, Tasmiya produced a series of projections, where she provoked alternate futures on the basis of varying recordings of the same history of the town. Through this process, she stumbled on the critical importance of the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. George in the then town of Grahamstown, which was the first built infrastructure that was introduced by the 1820s British settlers. The chapel operated as a school, civic space, market, bank, and church, and according to British law at the time, the presence of a British diocesan cathedral automatically rendered that territory a British city. In that way, architecture was used as an institutionalizing instrument.

The chapel’s various programmatic capabilities allowed the settlers to establish a premature settlement quickly due to it programmatic flexibility. This enabled them to move in their wives and children, to then make a case for the territory needing to be fortressed and defended. The very act of settling was the war tactic, with architecture as the tactic’s main weapon, and till today, the Eastern Cape is the most fortressed region of the nation and the most critical point of entry into the remainder of the South African geographic region.

Tasmiya drafted an all-encompassing atlas (inspired by the Catalan Maps) that attempts to make the relationship between Makhanda and Britain inseparable, as the process of institutionalization continuously worked across those territories toward finality, and remain intertwined.

It is at this point that Tasmiya approached architectural

r-1: The Biology of Fear (1:50) Mise-en-Abyme Model mannequin, perspex and cardboard

r-2: Tessa (1:1) Model plastic and textile

b-L: The Assembly Line (A5) Annotated Elevation and Axonometric instruction handbook

drawings as institutionalizing drawings, and interrogated ways of building a drawing as a way to draw a building, as outlined by Jonathan Hill in his Book Immaterial Architecture (2006:64).

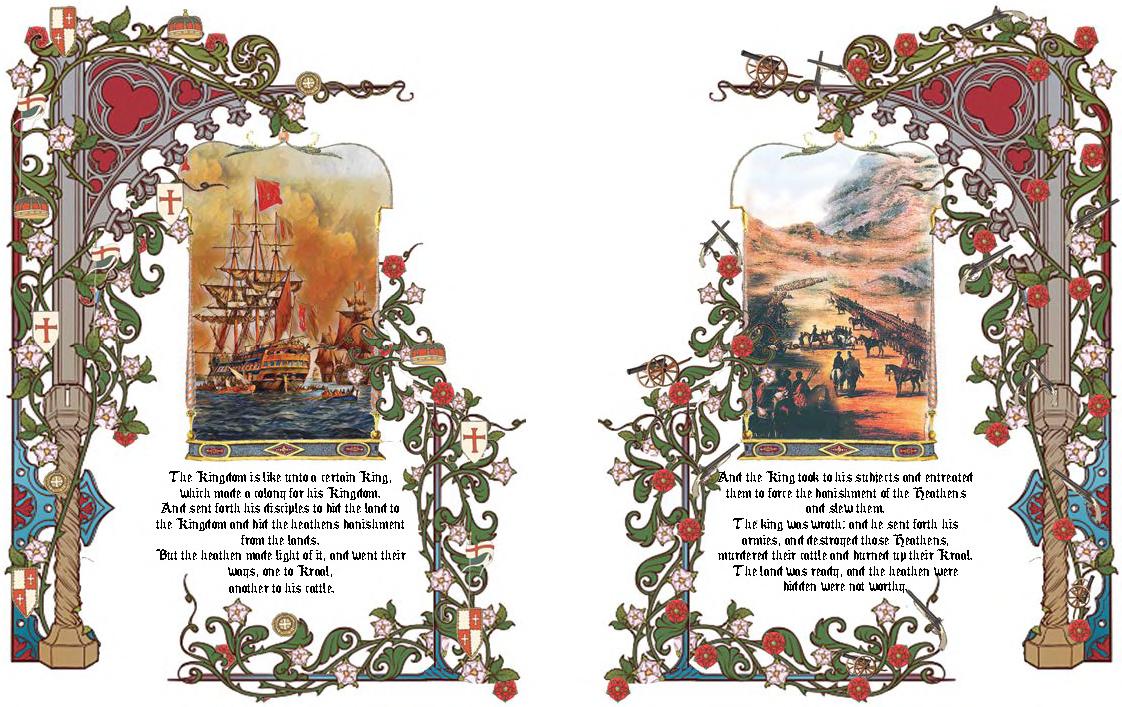

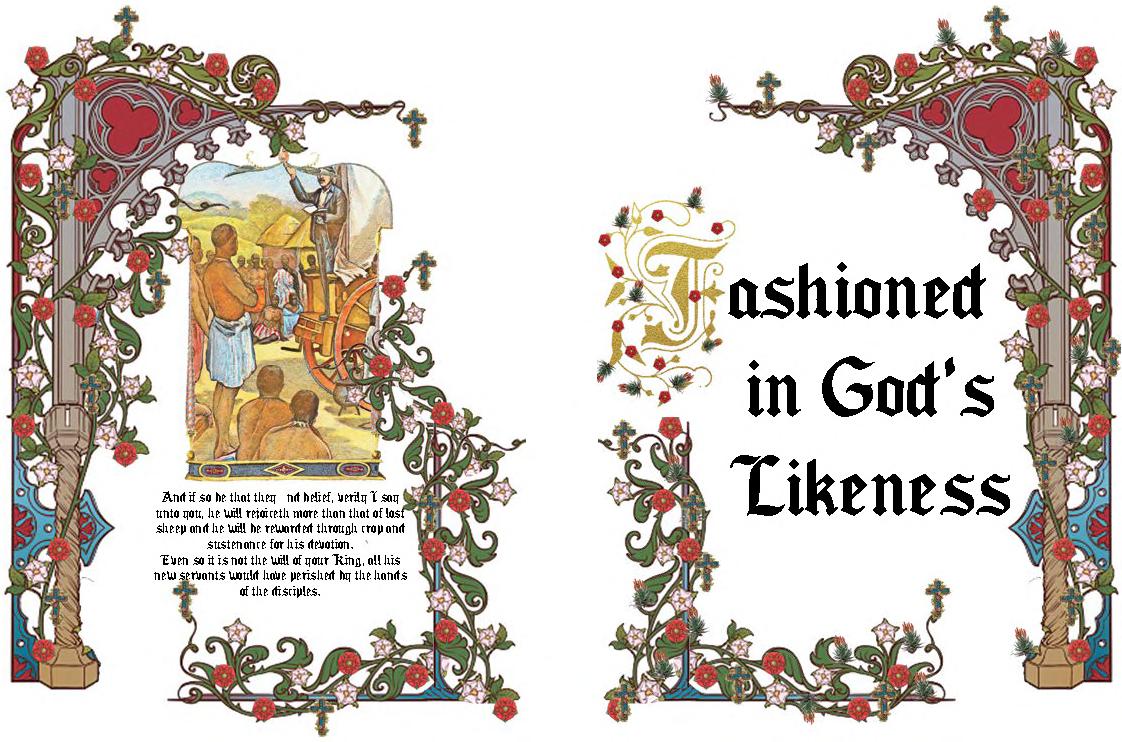

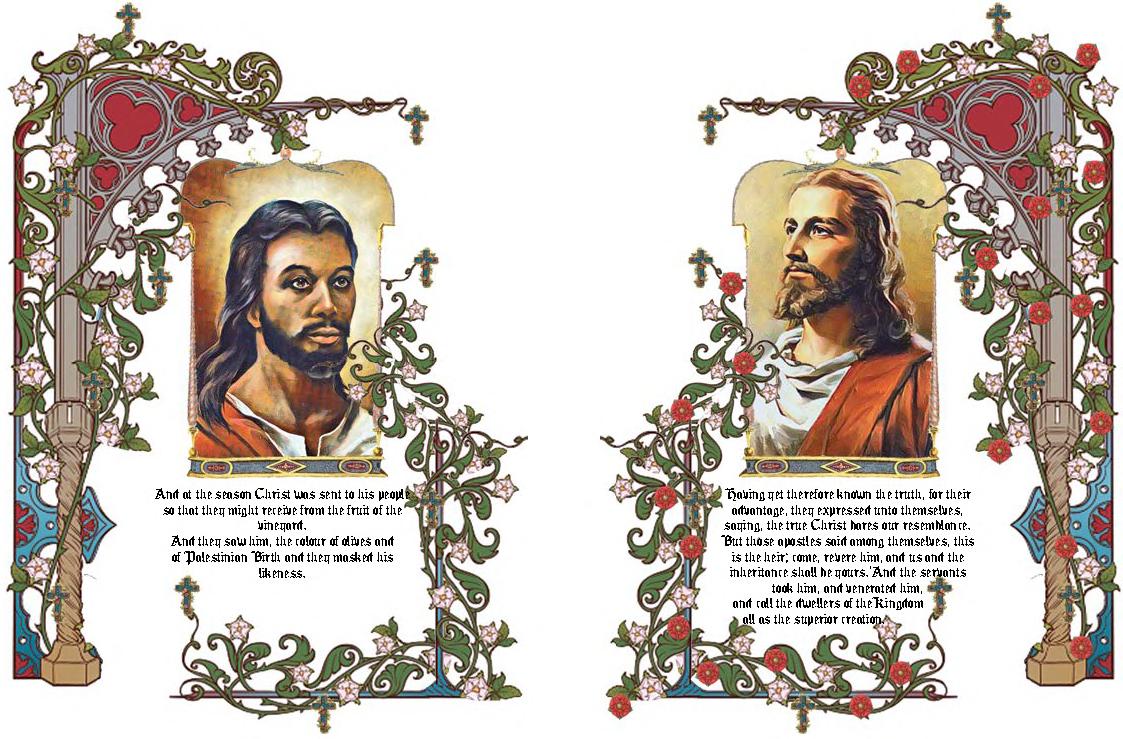

Tasmiya traced the town’s settlement process through its use of missionary work as a civilizing, educating, and assimilating tool, and proposed a way to redraw the spatial infrastructure of Makhanda’s foundational architectural infrastructures as they truly are, namely, as ideologies outlined as prayers in a prayer book called the Illuminated Manuscript. Her work attempts to reveal how biblical scripture was used to make an infrastructural case for the settlement. In the Manuscript, she treats parables as stage sets as she illuminates Makhanda’s blueprint as a holy - or rather ideological - material order, as argued by the then British settlers.

The manuscript comprises seven chapters, each articulating a critical instituting stage of Makhanda’s formation events. These chapters include:

1. Canon of Prayer (the British’s pursuit for greater

territories in times of resource crisis),

2. Expulsion from Eden (the British’s departure from Great Britain by ship),

3. Genesis (the start of colonial settlement in the Eastern Cape through forts),

4. Appointment of Divine Grace (the introduction of the cathedral and Christianity as civilizing tools),

5. Fashioned in God’s Likeness (the establishment of racial hierarchy and corresponding societal norms),

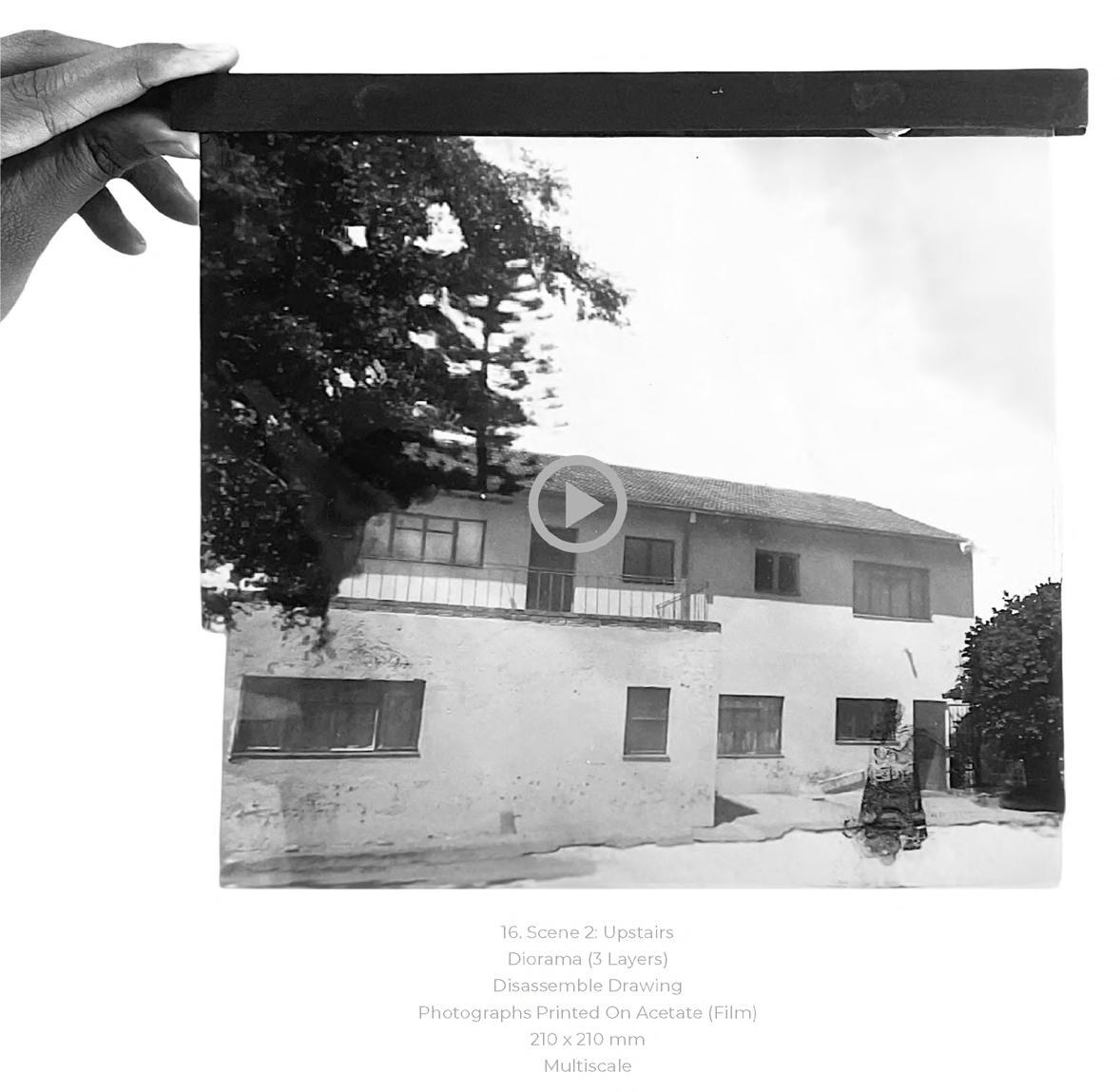

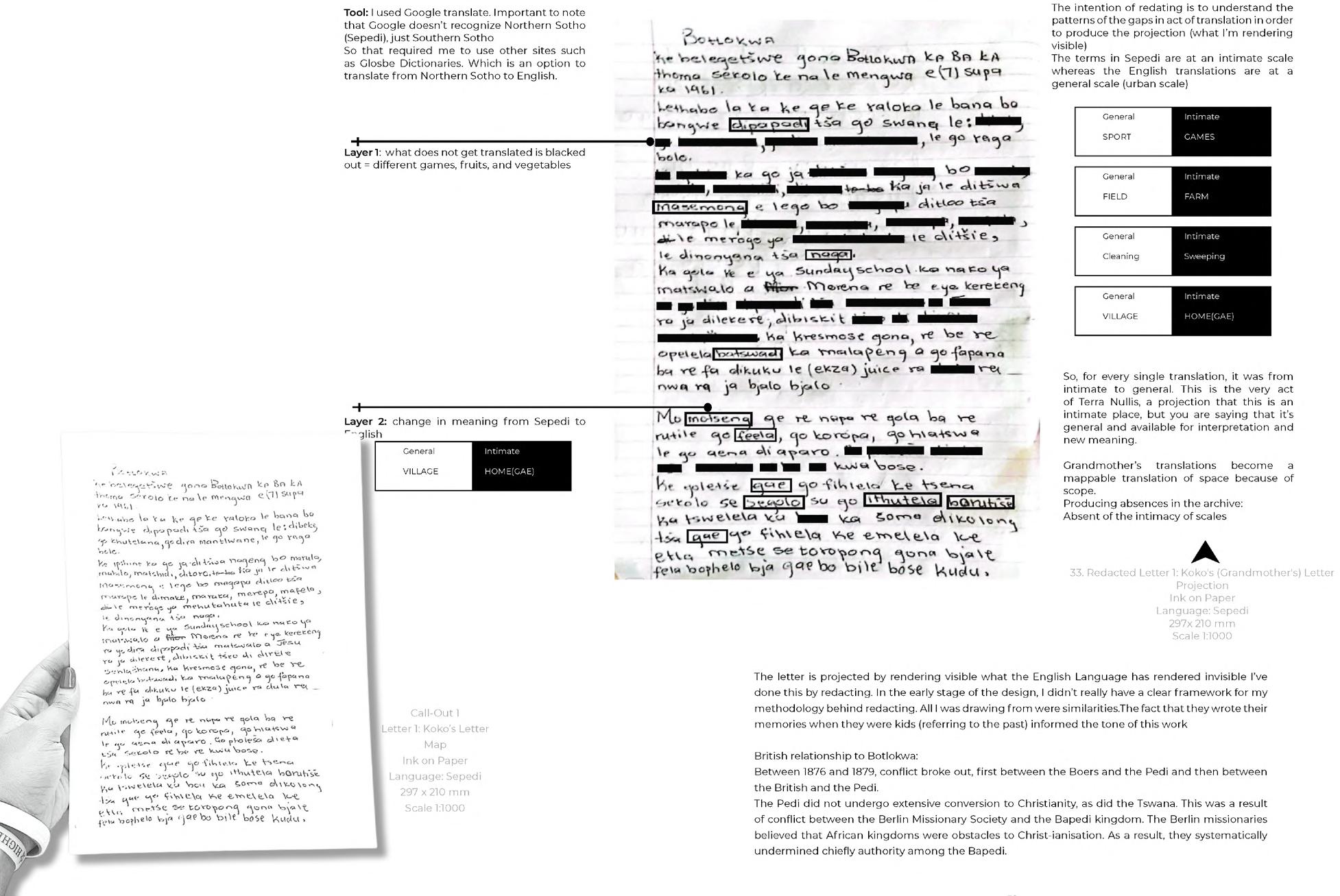

6. Knowledge of Good and Evil (the demonizing of African spirituality and cultural practices through English boarding schools, and the introduction of irrigation infrastructures as currency), and

7. Confirmation (the instituting of laws that affirm the new divine order).

Each chapter in the Manuscript is littered with its respective symbolisms as ornamentation, scenic scapes as an orchestrated and controlled gaze, parables as stage sets, and gothic frames as structural scaffolding, as was the cathedral for the town.

Product Assembly and Beta Tester Handbooks (A5)

Certificates and Guidelines

printed booklets

Colonisation Progression Across the Cape (not to scale)

b-L: Colonisation Progression Across the Cape (not to scale) Index Cards

cardboard and vinyl print

Origin Stories - Hidden Meanings (and Index) [multiscalar]

Visual Narratives as Cross-Sections hung photo-negatives

Alternate Histories (not to scale)

Area Maps collage and overlay

Illuminated Manuscript (Four Pages) [A2]

Book of Prayers Comprising Ornamentation, Scenic Scape, Stage Set, and Structural Scaffolding printed and bound book

Illuminated Manuscript (Four Pages) [A2]

Book of Prayers Comprising Ornamentation, Scenic Scape, Stage Set, and Structural Scaffolding printed and bound book

T-r

T-r: Illuminated Manuscript (A2) Book of Prayers Comprising Ornamentation, Scenic Scape, Stage Set, and Structural Scaffolding printed and bound book

r-2: Illuminated Manuscript: Atlas (not to scale) Cartographic Map rendered pencil and digital graphic

1.) Hill, J. (2006) hunting the shadow in Immaterial Architecture. New York, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, p. 64.

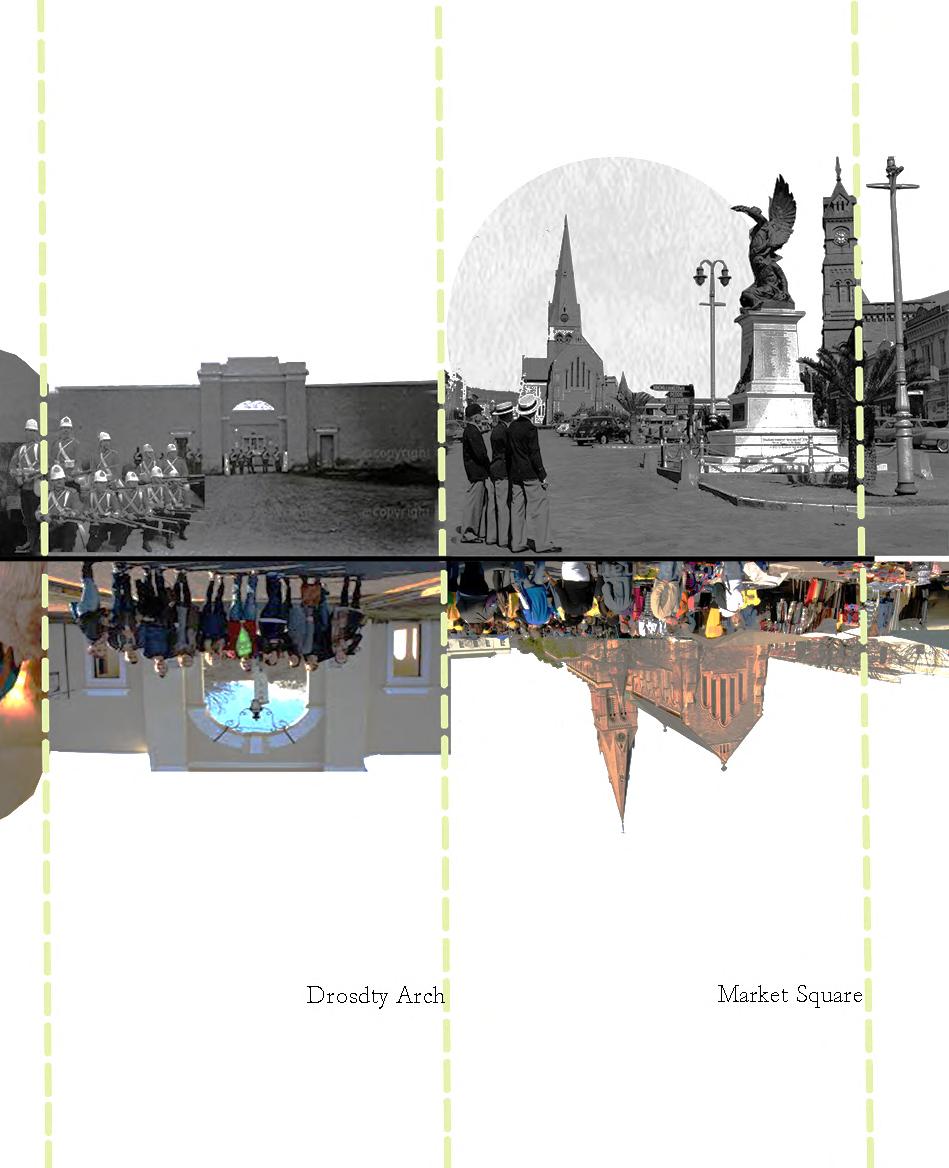

SITE: 1820s Settler Museum, Old Gaol Prison, Old Drosdy Archway

Abstract

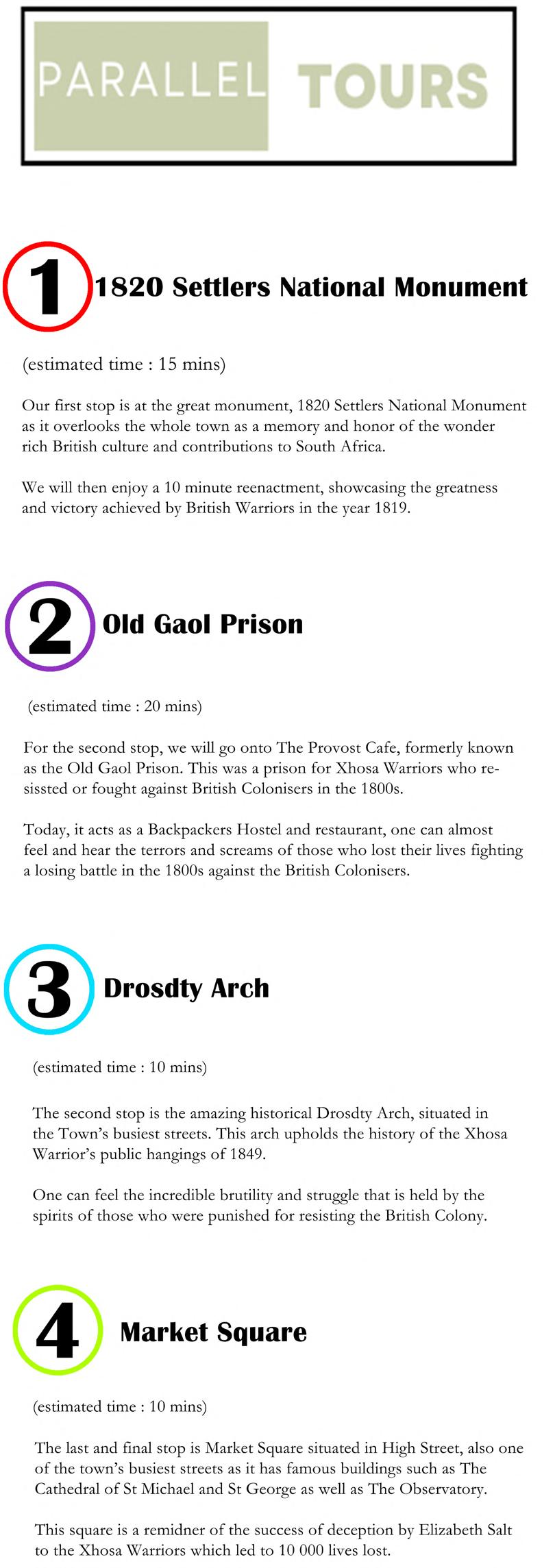

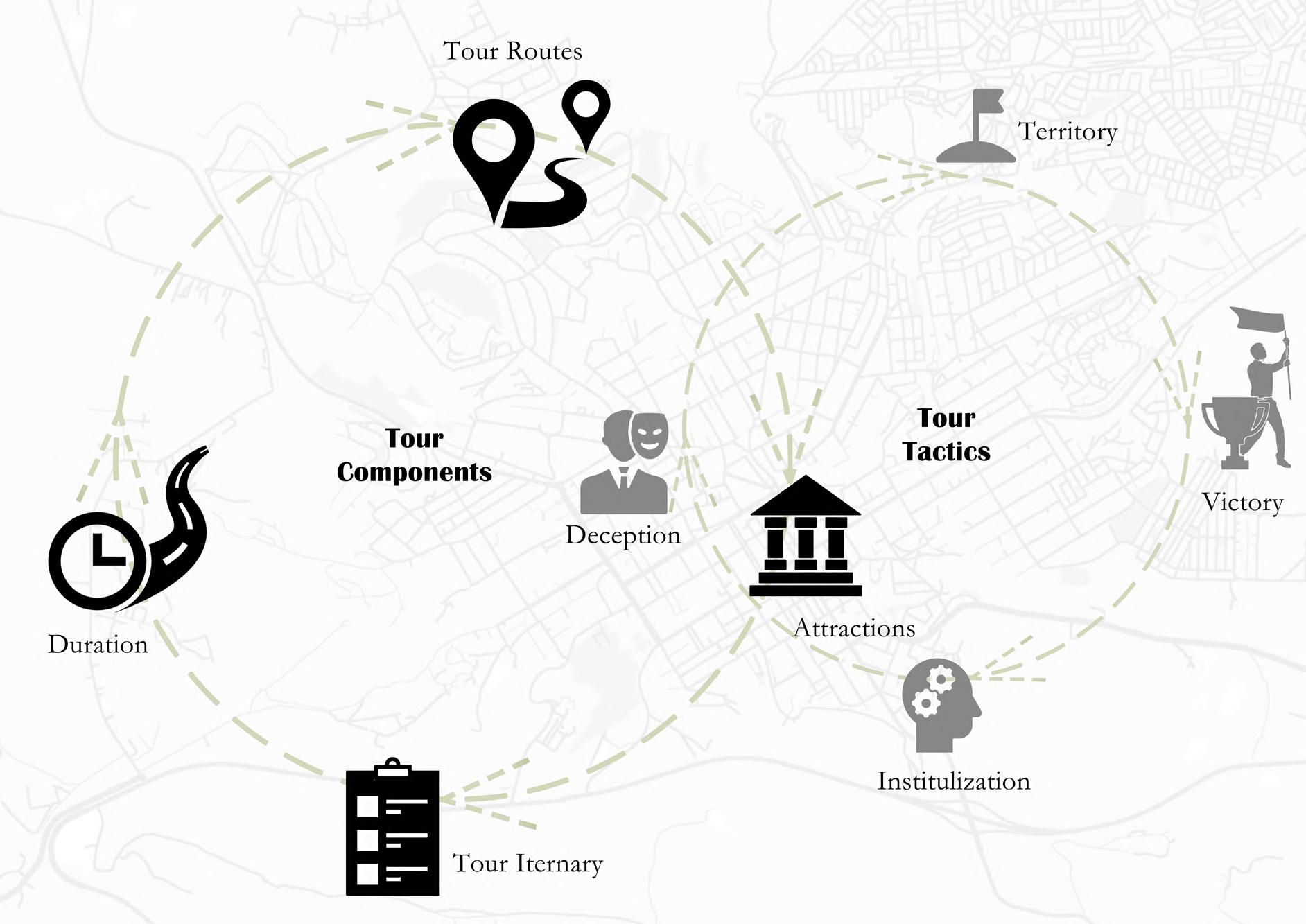

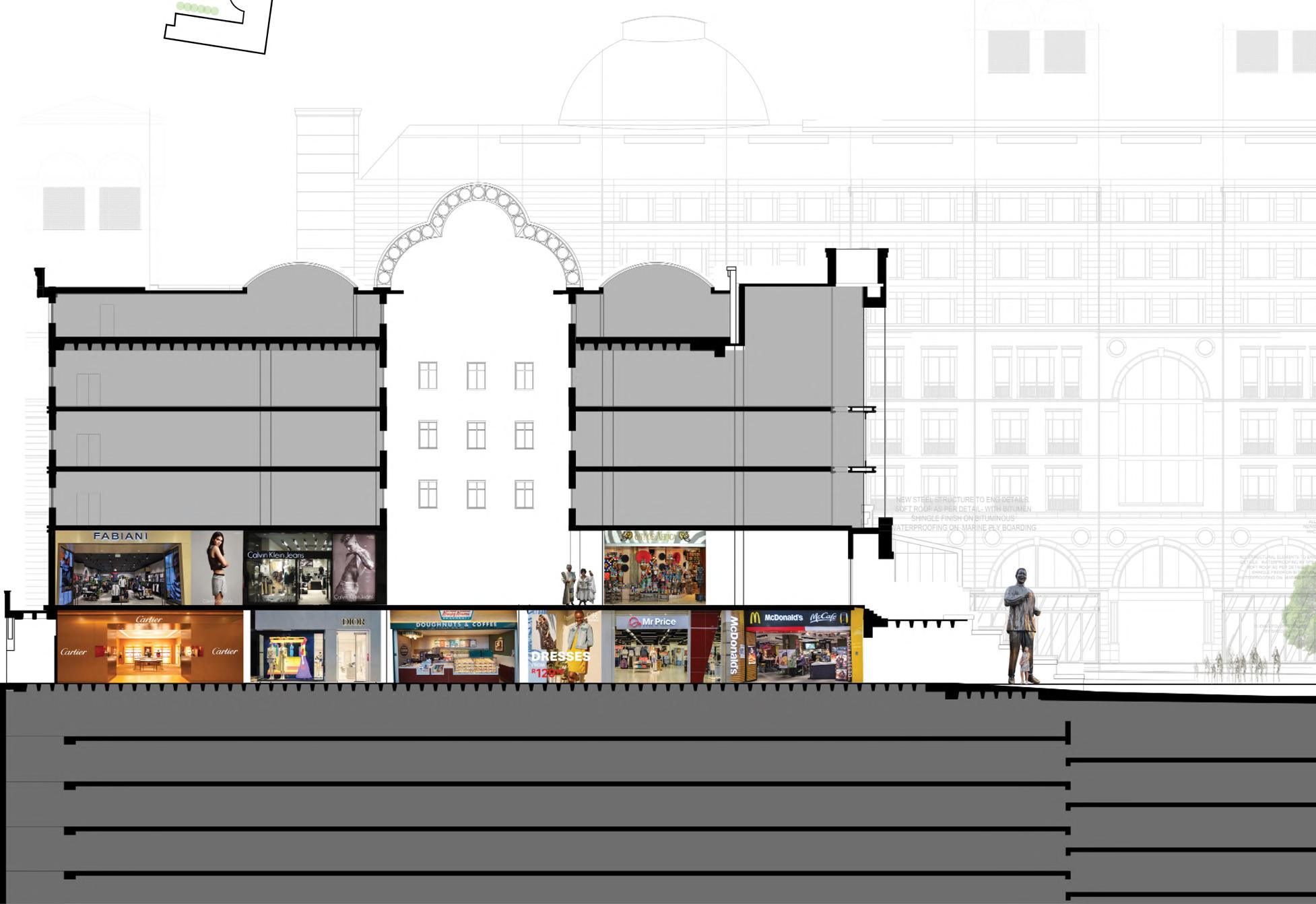

The work investigates architecture’s use as a rebranding prop in post-apartheid South Africa, where once weaponized spatial conditions are reframed as dignified and/or leisurely.

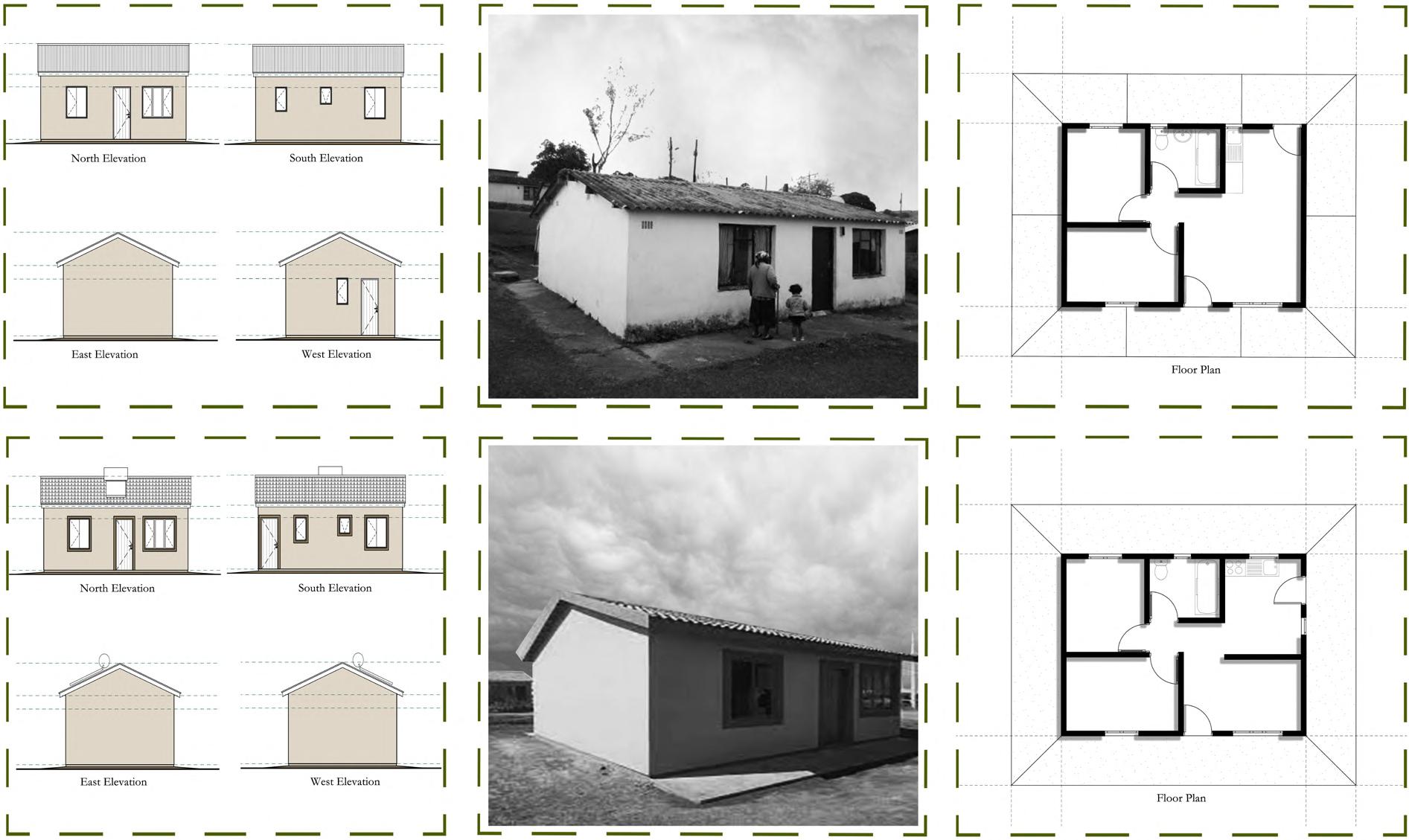

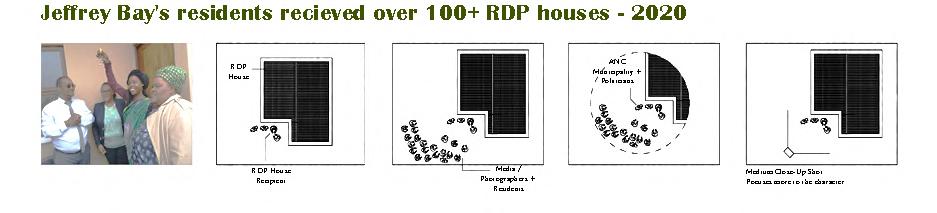

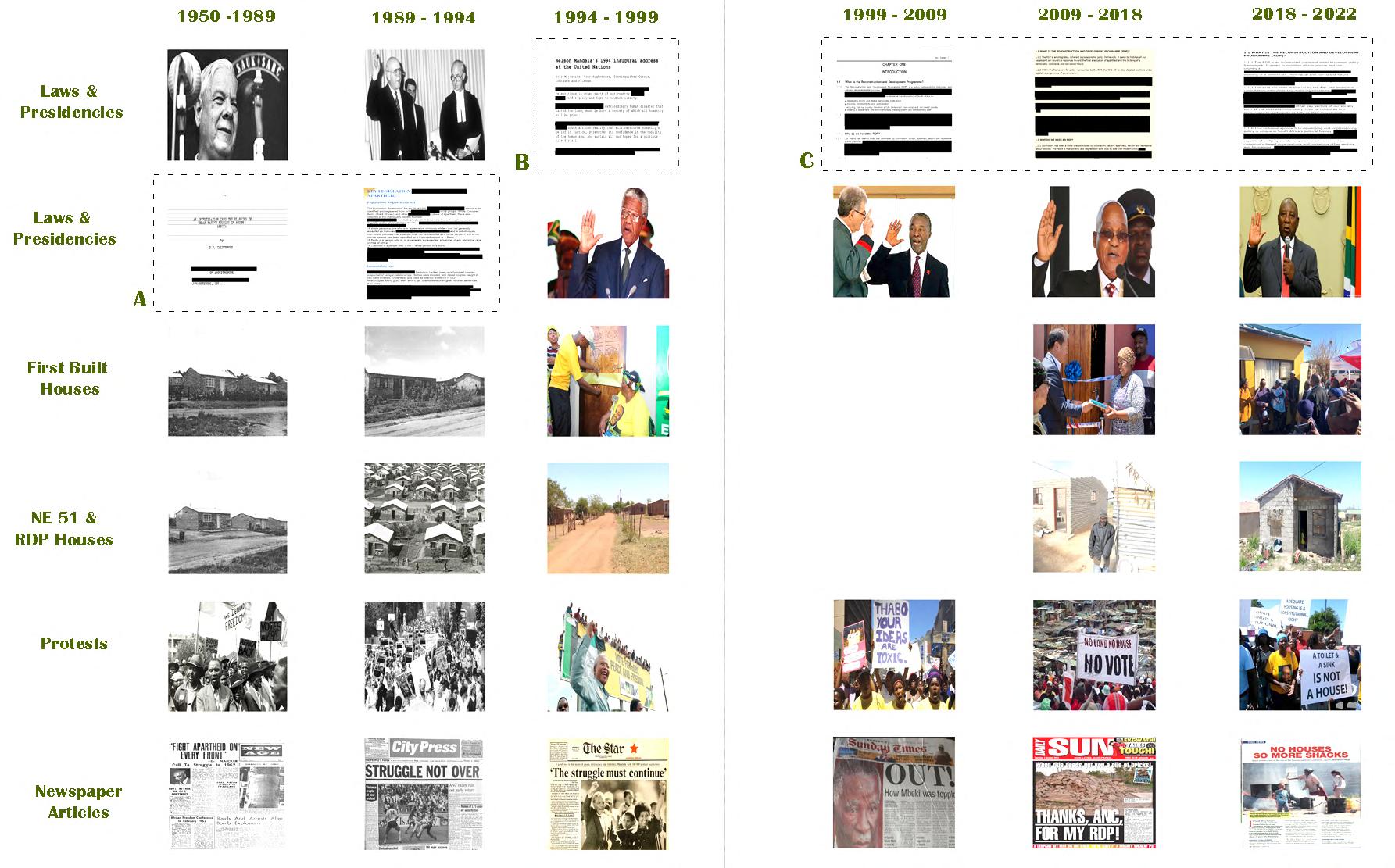

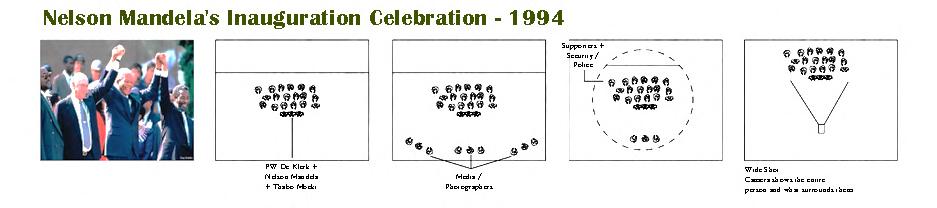

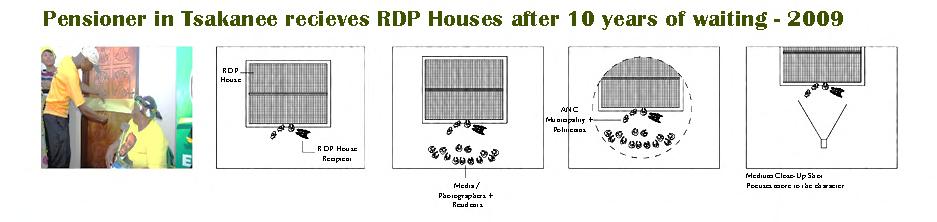

The work reveals how the South African democratic government practices spatial rebranding through law, media, and tourism, and uses apartheid’s non-European 51 (1951) migrant labour temporary homes alongside the 1996 Land Reform Act RDP (Reconstructive Development Programme) housing scheme as grounding case studies.

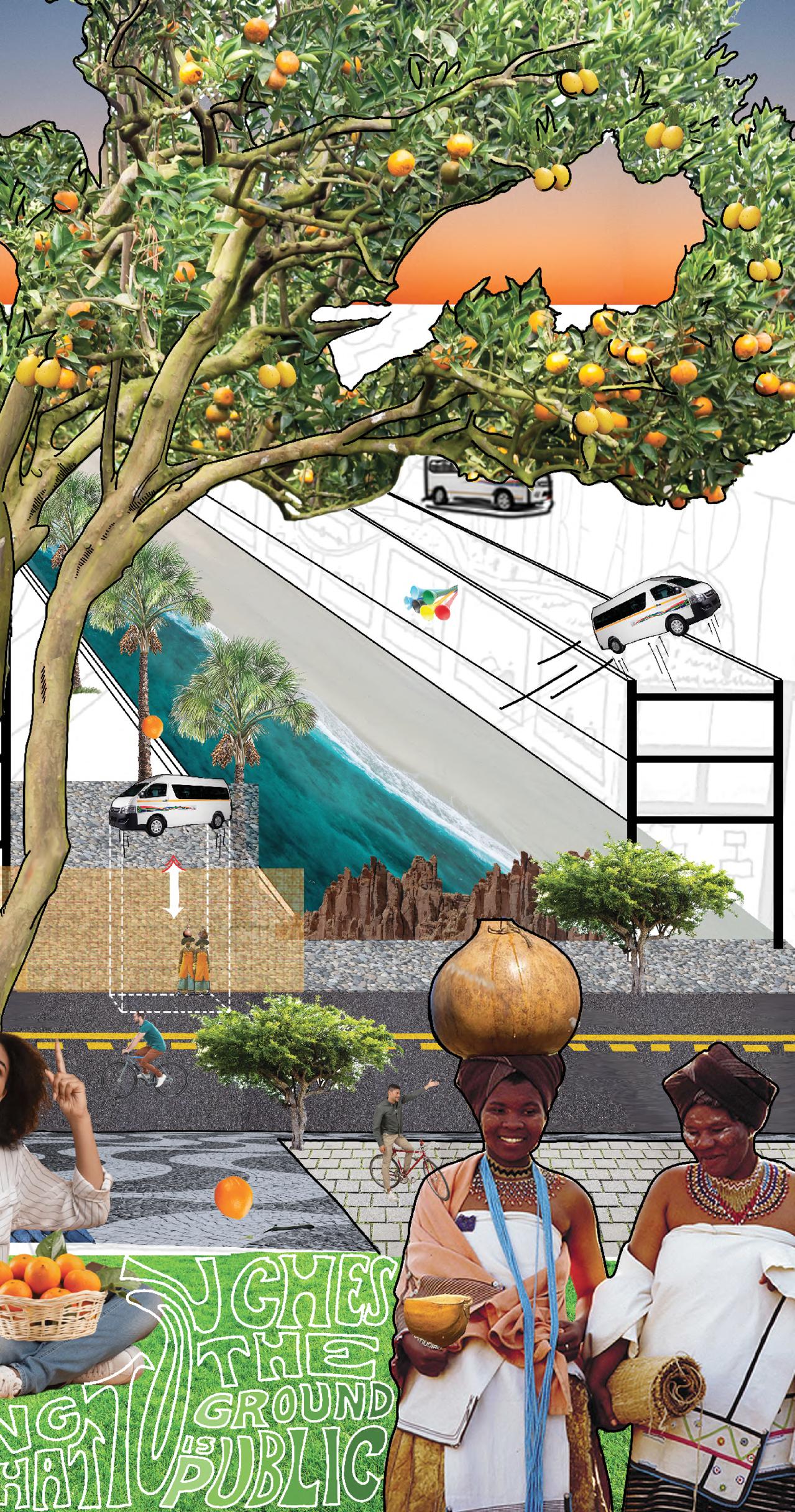

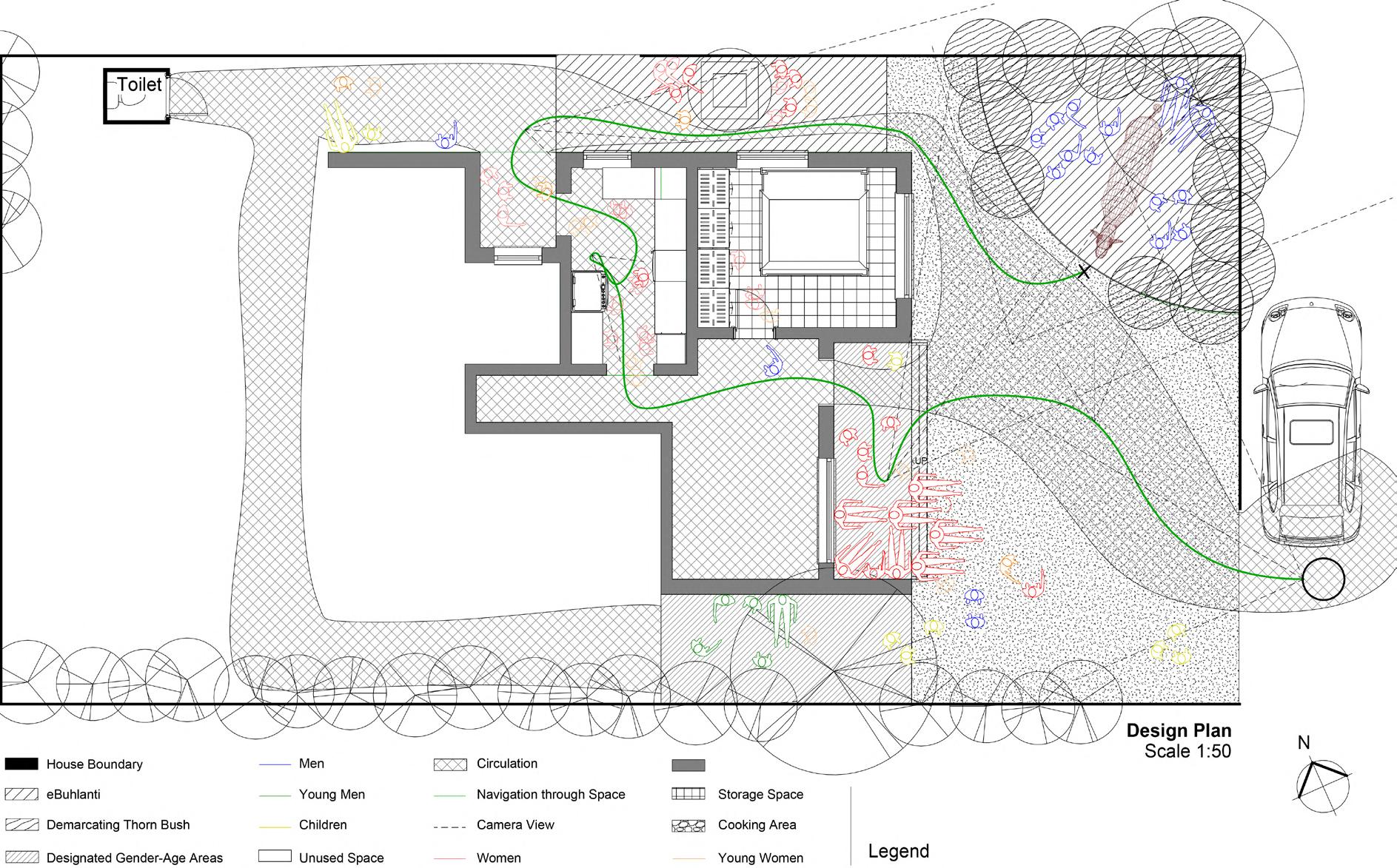

The research homes in on the British settlement town of Makhanda (formerly known as Grahamstown, but still seldomly referred to as its rebranded name), and focuses on the town’s lack of physical change, despite its legislative rebrand as symbolic reparation, as stipulated by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The work focusses particularly on an annual tour that takes place in the town, where the re-enactment of British victory over the Xhosa is simulated at the highest outpost point of the town, which is now the site of the 1820s Settlers Museum. The work approaches such ritual practices as the practice of mythmaking and knowledge creation, that is disguised through a seemingly innocuous spatial frame of a tour, which allows it to be repetitively reinforced on a ritualistic basis. The work proposes a disruption of that territory-making by intercepting the spatial framework of the tour.

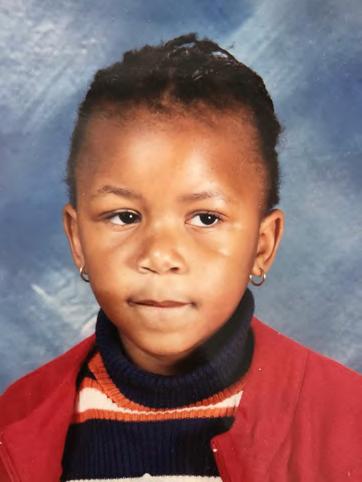

Sesethu is from the Eastern Cape township of Ncambhedlana in Mthata, where she was raised by her grandmother in a two-bedroom Reconstruction & Development Program (RDP) house that was provided by the state.

Her work looks at the South African government’s use of architecture as political symbolism and a rebranding prop, and her research started with the study of the overlaps between South African architect Douglas Calderwood’s NE51 homes (or the Non-European homes of 1951) - which were designed to be temporary units for black migrant labourers in apartheid townships - and the RDP homes offered post-apartheid (through the land reformation act of 1996) as a solution to the country’s gross urban housing shortage. She treated both home typologies as spatial artifacts, and dissected them through plan, section, elevation, form, and circulation drawings, offering this comparative study through the game of Spot the Difference. Through this, participants reveal the negligible differences that exist between both typologies, as the NE51s - that were historically designed for indignity - have now been re-pacakged and offered up as the democratic era’s dignified housing solution. She refers to this practice by the state as ‘material rescripting’. It happens in several forms in post-apartheid South Africa, such as township tours (also known as township cruises) that re-package the once heavily surveilled and resourcestarved apartheid townships into theme parks of sorts.

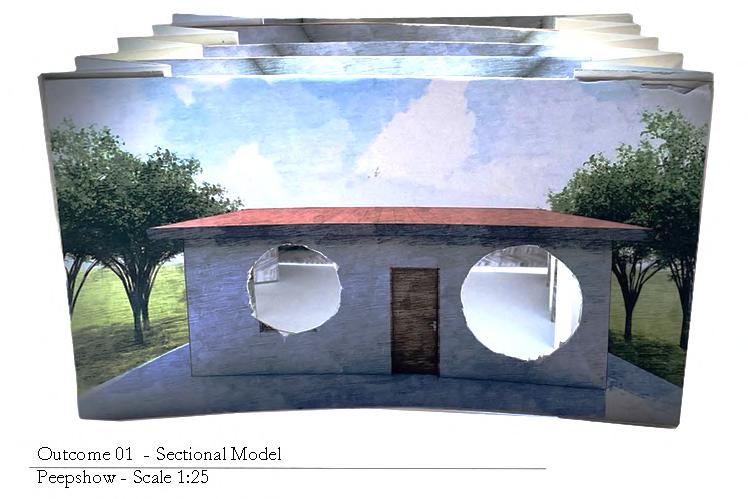

Sesethu then investigated the history of townships through the typology of a laboratory, as she uncovered how those spatial territories were used as socio-spatial formula testing grounds for the apartheid regime’s standard-ofliving experimentations on black South Africans. She provokes the notion that those environments still act as the stage on which such experiments are playing out (as if the original hypothesis is being tested over an extended period of time and across generations). In an effort to give language to these experiments, Sesethu scripts the existing hypotheses that are potentially being played out as outlined in our democratic laws. She produced a series of 1:25 peep shows that separates the components of the hypotheses and allow us to isolate our gaze to a

single layer of an experiment at a time. That way, we are able to see the consequences of each component to the whole as each gets added individually. The device of the peep shows moves us through the different experiment outcomes as we add or remove layers.

Sesethu’s research interest lies in architecture’s ability to be politically co-opted through State rebranding tools such as the law. She dissected Section 26.1 (Constitutional Assembly, 1996:11) of the South African Constitution, which articulates that

“Everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing. The state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right” (1996:11).

Through the ‘Latent Ambiguity’1 capacity of the law, Sesethu interrogated the ability for the term ‘adequate’ to be mis-applied to apartheid spatial relics such as the RDP house typology.

She worked through changes in news and advertising media, political and legal framings, as well as the logics of nomenclature of the democratic housing process to uncover the State’s language of spatial rebranding, and treated these findings as a national-scale cross-sectional drawing. Through several State of the Nation (SONA) addresses, newspaper articles, protests, and state-hosted social housing scheme handover events, the work revealed and gave language to the State’s infrastructural rebranding toolkit.

Through analytical choreographic drawings, Sesethu traced notable state-hosted events through the lens of filmmaking, and outlined how the events were recorded

1 In a legal sense, ‘Latent Ambiguity’ is defined by San Diego Research Professor of Linguistics at The University of California, Sanford Schane (2016), in his article Ambiguity and Misunderstanding in the Law, as an occurrence “where there is lack of clarity or when there is uncertainty about the application of a term in which extrinsic evidence presupposes more than one way of interpretation. However, at the face of it, it seems clear” (Schane, 2016). This in turn, allows the application of the law to be misinterpreted, misunderstood, or mis-applied.

and projected to the nation as media propaganda. She focused mostly on citizens that finally got their RDP houses after waiting for 10+ years.

Sesethu’s work attempts to confront our democratic era’s recurring practice of spatial rebranding as its tangible but dishonest offer of democracy.

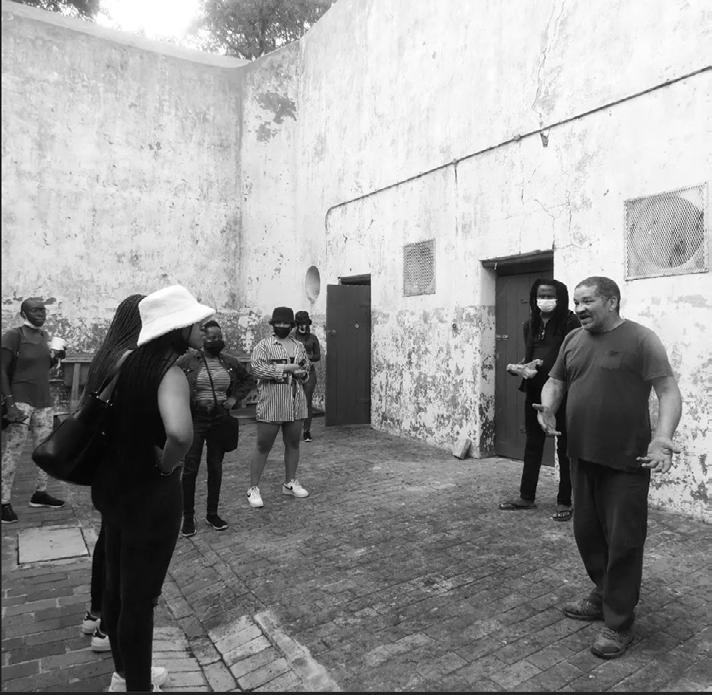

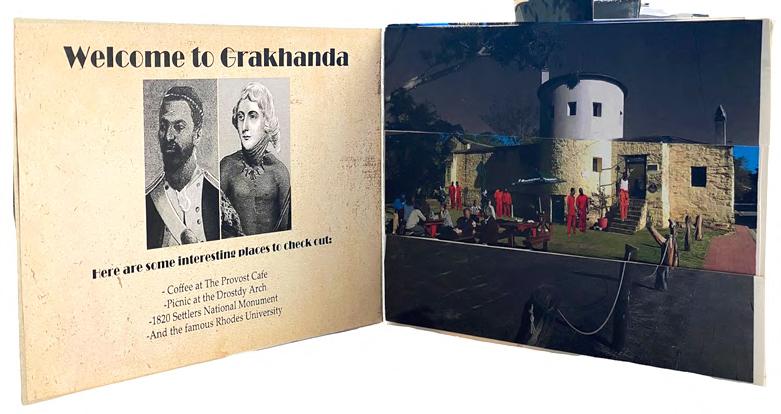

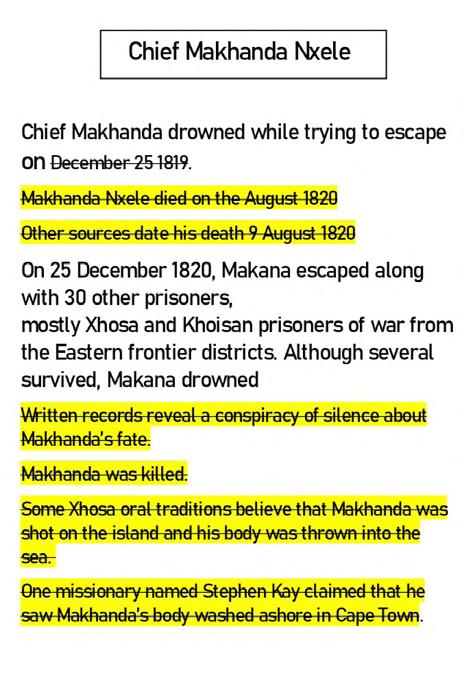

On our Unit’s Makhanda field trip, Sesethu delved into Makhanda as a rebranding of Grahamstown. The name ‘Grahamstown’ was offered by Commander of the Regiment, Colonel John Graham; named after himself. On 02 October, 2018, the town got officially renamed to Makhanda in memory of chief Makhanda, a well-known Xhosa warrior and prophet, and a contentious figure to the Xhosa people (as they blame him for their loss over the British).

The then Arts and Culture Minister, Nathi Mthethwa, announced the town’s name change from Grahamstown in the Government Gazette (No. 641 of 29 June 2018) and said how it was to be a “symbolic reparation” to “address the unjust past” (Government Gazette, 2018).

Through what she called Grakhanda at the time, which is a portmanteau of both Makhanda and Grahamstown, she articulated site through a tour that conflates the past and present, as a mirroring of the state’s tactics in how they repackage the past and offer it as the present and/or future. She collapsed time, place, and event, as she projected past programs and practices (that got overridden through the town’s rebranding process) into the present. Her work then articulated the meaning of ‘future’ as a repackaging of the past.

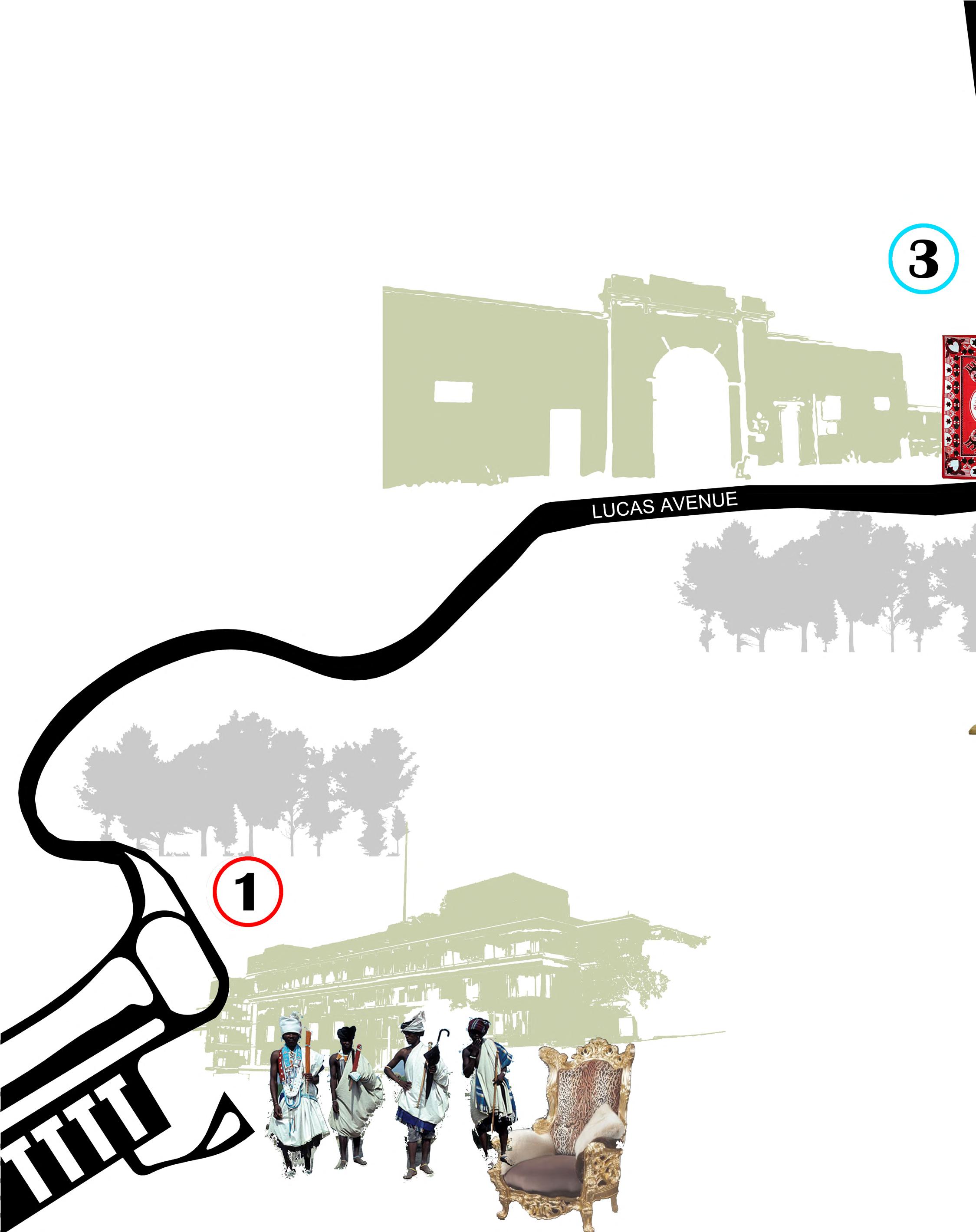

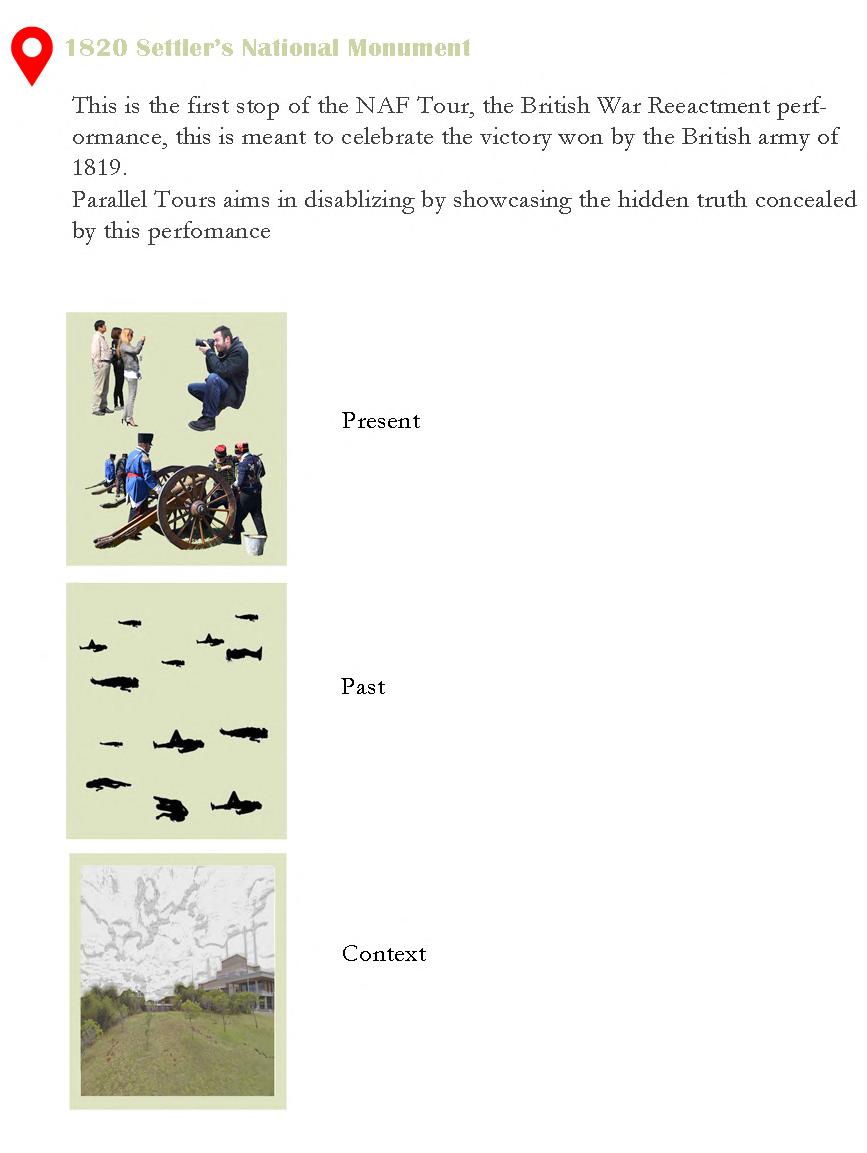

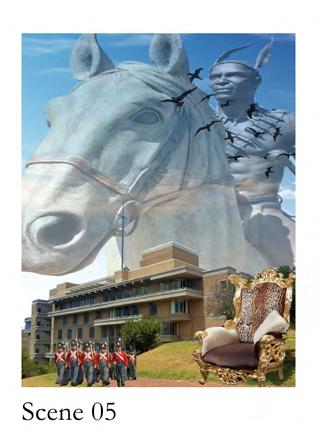

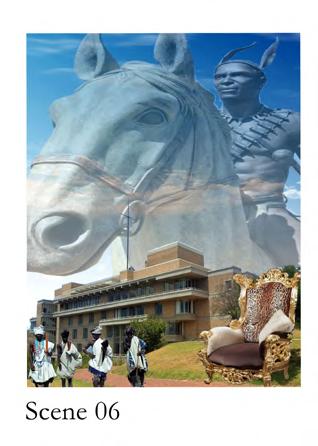

Through these rebranding studies, Sesethu uncovered an annual British victory re-enactment tour that takes place every July at the Grahamstown Arts Festival, atop the highest lookout point of the town, which was historically used as a British military defense outpost, but now houses the 1820s British Settlers Museum.

Sesethu’s work, as an attempt to reveal the innocuous spatial capacity of tours, proposed a parallel tour as a Bank of Territory Mythmaking, as she argues that tours

contain in them mythical notions of territoriality that temporarily override notions of space and place. Michel Foucault, in Archaeology of Knowledge, refers to tours as the perfect tool of discourse, as it operates as a powerful tool of knowledge-production and allows the subtle insertion of ideas into social life. Sesethu proposes the tour in an effort to intercept the annual British victory re-enactment tour, that she treats as a territory- and mythmaking spatial instrument that hides the practice of conquest in plain sight.

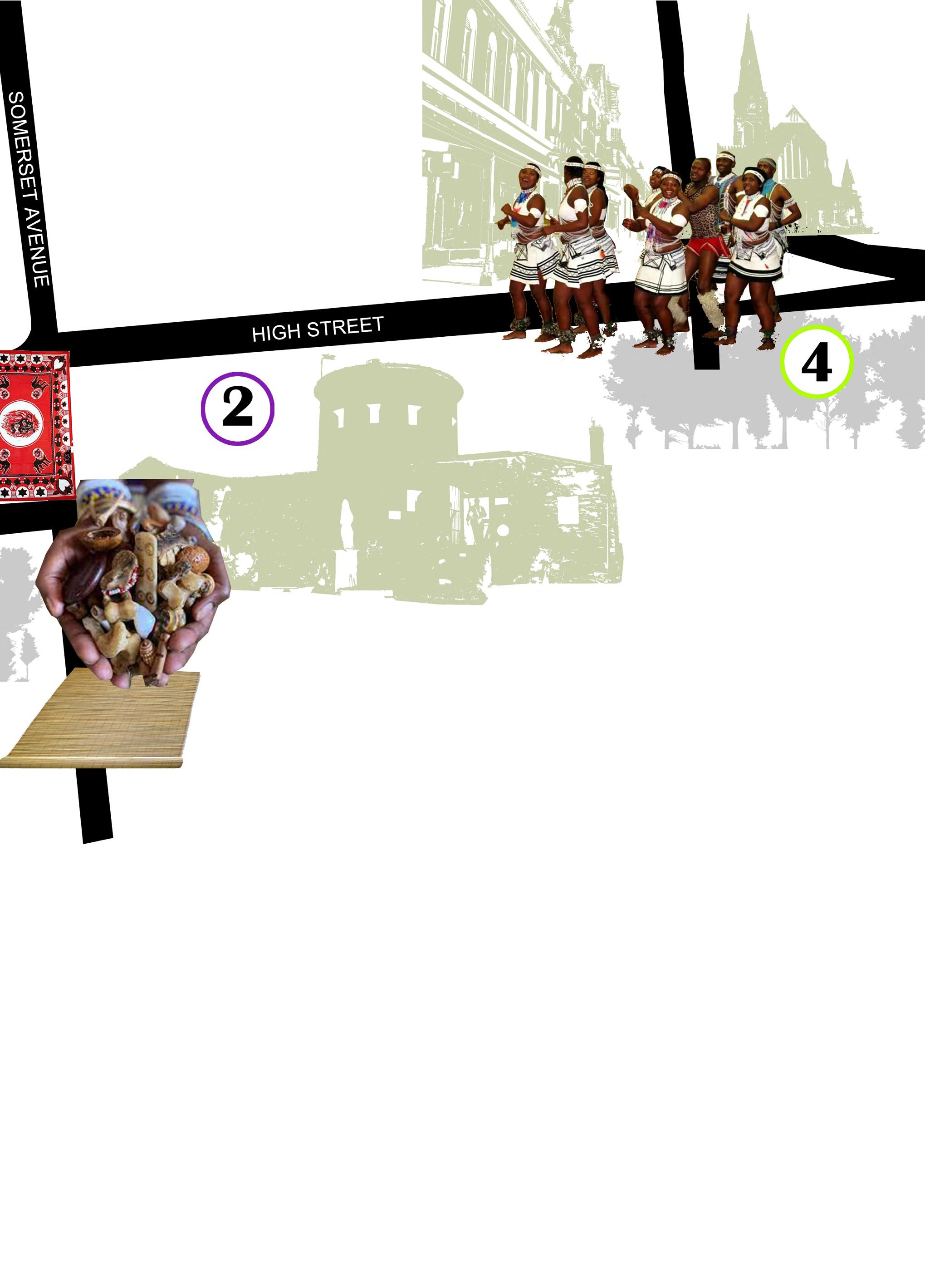

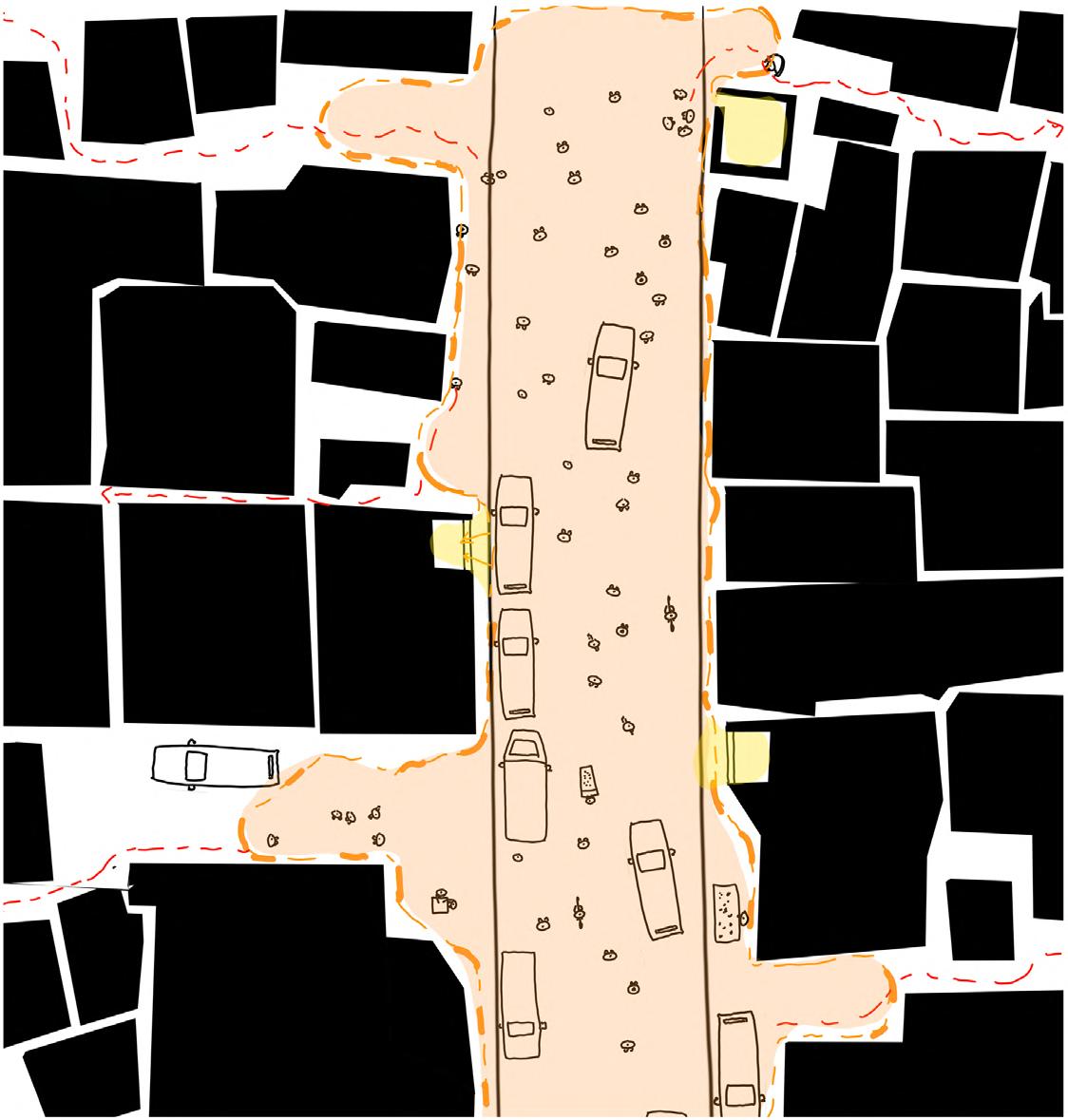

Sesethu employed touring methods of map-making - an intentionally reductive and hierarchizing spatial languaging tool as it simplifies cityscapes and plans - and demarcated spatial and event-based points of interests by rendering everything else that is not of interest, invisible.

Sesethu chose four sites in Makhanda to intervene on that are important tourist sites of victory for the British: The 1820s Settlers museum, the Old Gaol prison, the Drosdy Archway at the entrance of Rhodes University (where prisoners used to be hung in public) and Market Square, known as the site where a deception tactic by British forces involving a woman and child2 led to British victory over the Xhosa.

In her proposed parallel tour, she offers the following annual tour interventions at the respective sites:

1. at the 1820s Settlers Museum, she proposes a ritual response to the prophesy of Ukuza kukaNxele that claims the impending return of chief Makhanda through historical reenactment;

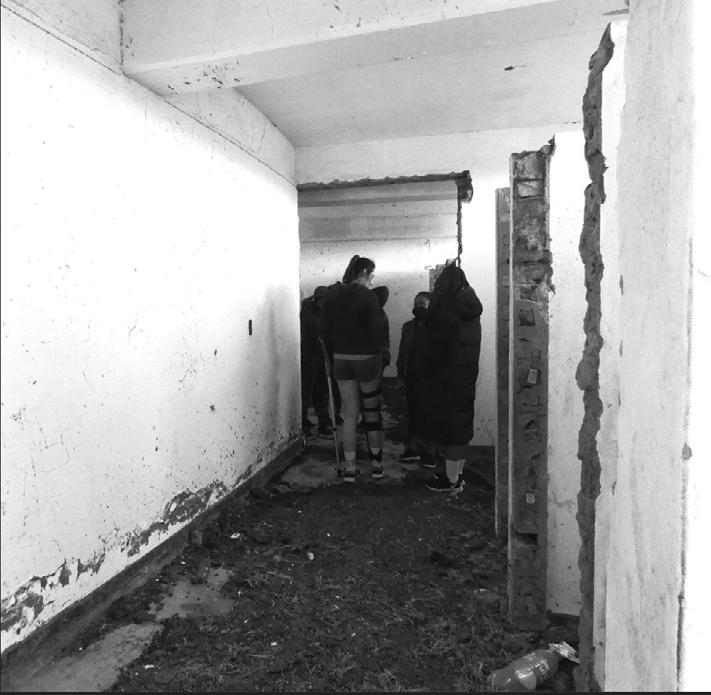

2. at the Old Gaol prison (and as an extension of the Drosdy Archway), she proposes a space of cleansing, as five hundred Xhosa warriors lost their lives there. The annual cleansing is proposed as a way to get their souls to rest, but also renders the site sacred, in contrast to its current use as a restaurant and commercial space; and

3. she proposes a Xhosa market on Market Square, as a way to start introducing authentic Xhosa cultural artifacts and rituals to the town again.

2 This deception tactic mirrored the original British settlement tactic of populating the Eastern Cape territory with ‘innocent women and children’ to make a case of increased defence and fortification, thereby speeding up their process of occupation. T-R: Spot the Difference (1:100) Plans, Section, and Elevations catalogue B-R: The Laboratory Results (1:25) Sectional Models peep shows toys B-L: Settler’s Paradise Book (A4) Collaged Elevations accordian book B-LT-R

T-R:

Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom (1:200)

Choreographic Transcripts archival photos and line drawings

B-R: Tracing History (multiscalar) Cross-Section speeches, archival photos and newspaper articles

B-R

Tour Sites Parallel Timelines (multiscalar) Elevations

Proposed Parallel Tour (not to scale)

The Road to Mythmaking with Character Palette (multiscalar)

T-L: Tour-Simulated Reality 01 (not to scale) Perspective collage

B-L: Tour-Simulated Reality 02 (not to scale) Perspective collage

T-L

B-L

T-L

B-L

T-R: Tour Tactics (1:100) Diagrammatic Map collage map and icons

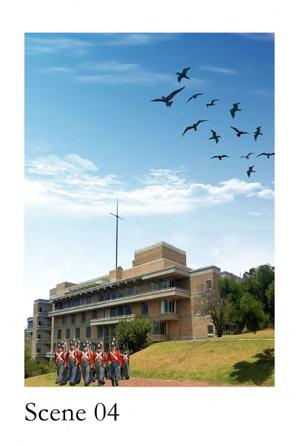

B-R: Disruption of Territory-Making (not to scale) Film Scene Perspectives film collage

References

1.) Calderwood D, 1953. Native Housing in South Africa. [O]. Available: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/11249

Accessed 5 March 2022

2.) Department of Human Settlement. 1998. Housing act 107 of 1997. [O]. Available: http://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislation/ Housing_Act_107_of_1997.pdf

Accessed 15 May 2022

3.) Schane, S. 2016. Ambiguity and Misunderstanding in the Law. [O]. Available: https://idiom.ucsd.edu/~schane/ law/ambiguity.pdf Accessed: Accessed: 14 May 2022.

4.) South African Government. 2021. Constitution of the republic of South Africa no. 108 of 1996. [O]. Available: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96. pdf

Accessed 15 May 2022

5.) South African Government. 2019. Land Reform. [O]. Available: https://www.gov.za/issues/land-reform

Accessed 15 May 2022

SITE: Albany Museum, Makhanda, Eastern Cape

Abstract

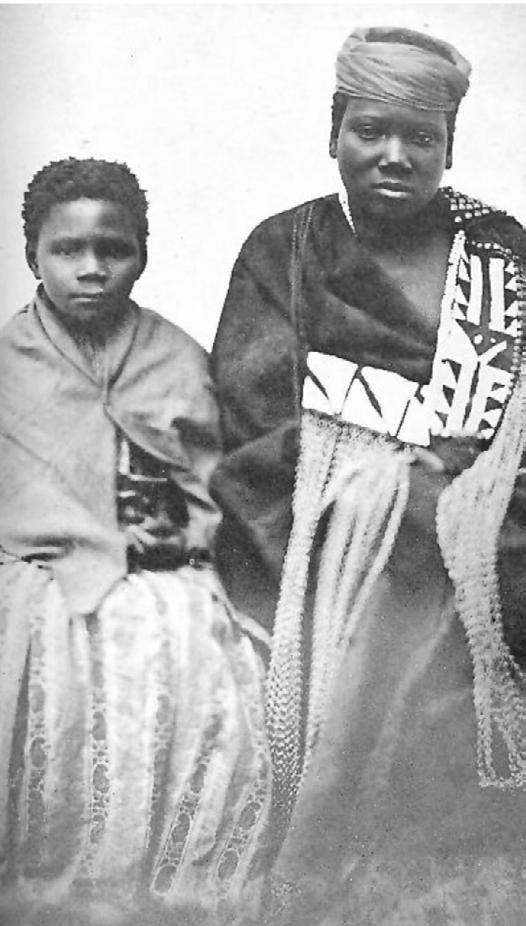

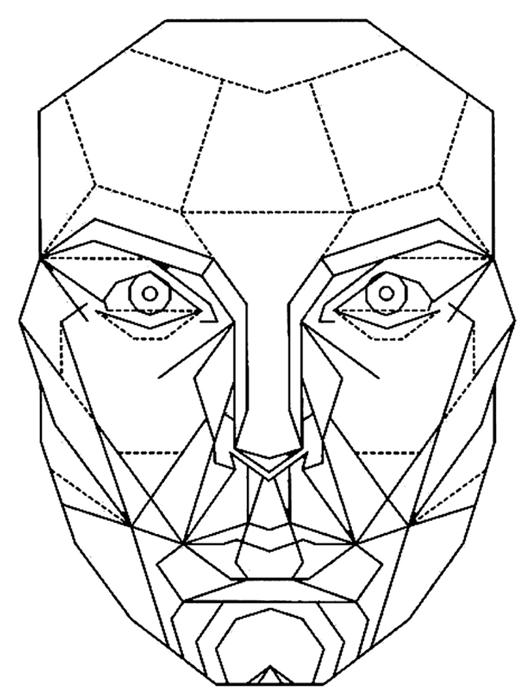

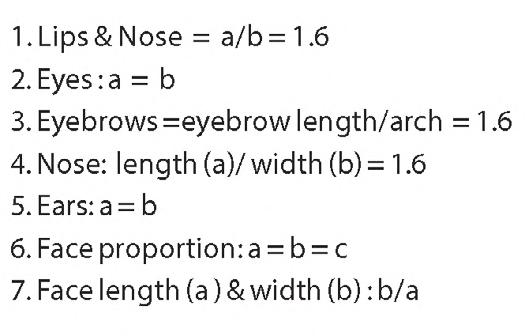

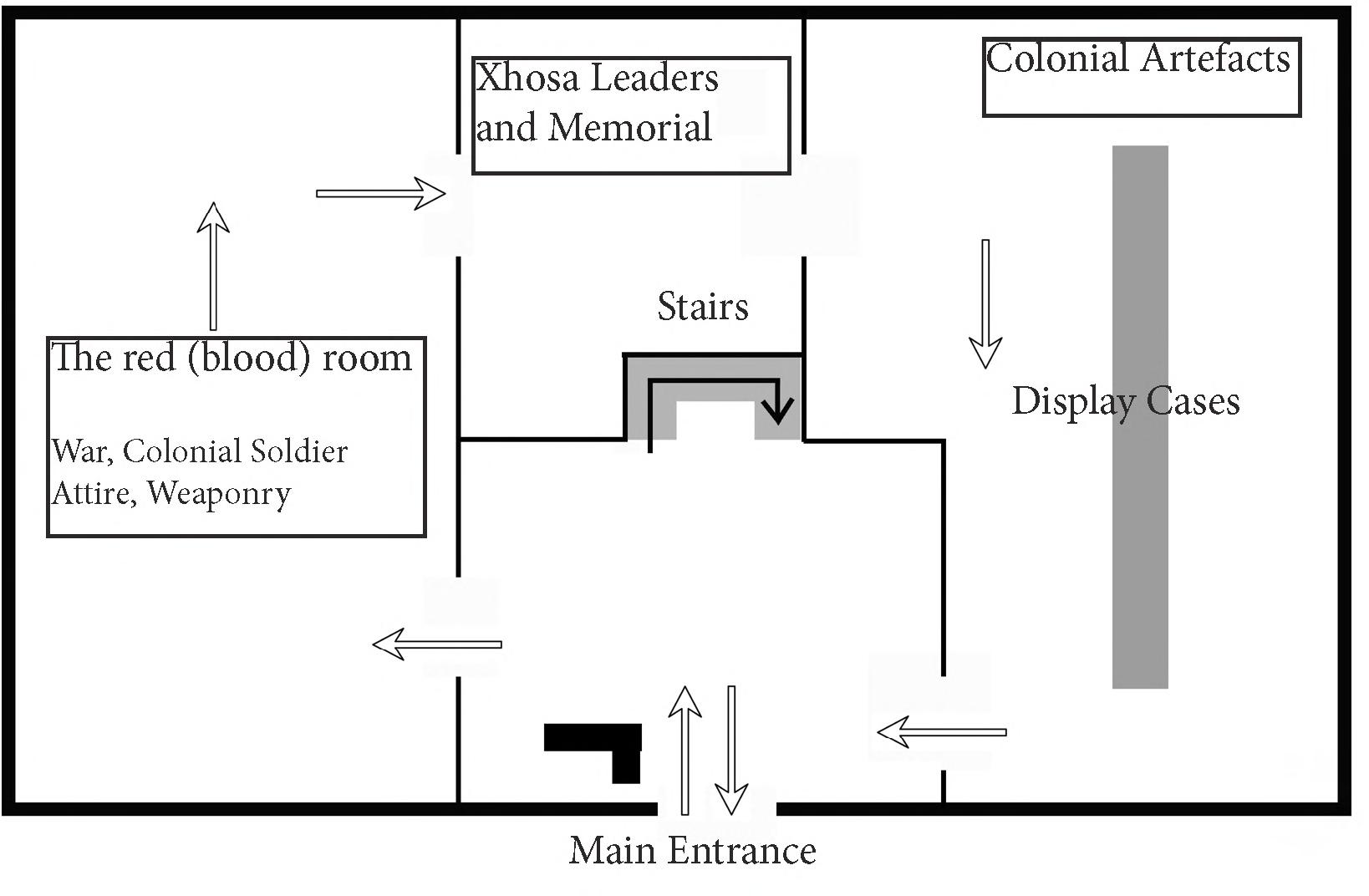

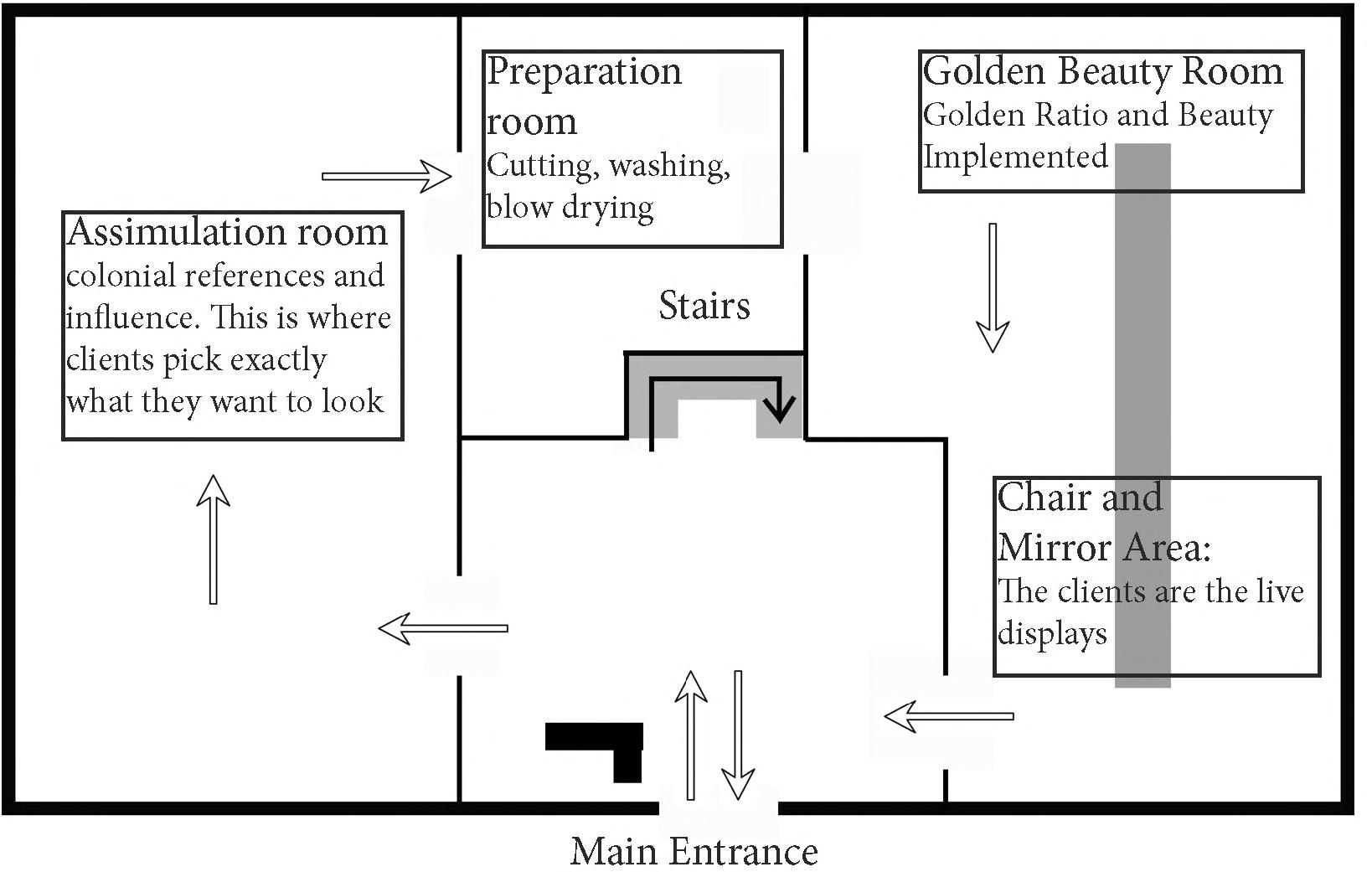

The work investigates hegemonic image-making standards through façades, where spaces that can be seen as identity-facilitating factories maintain the perversion of black female identity through assimilation practices.

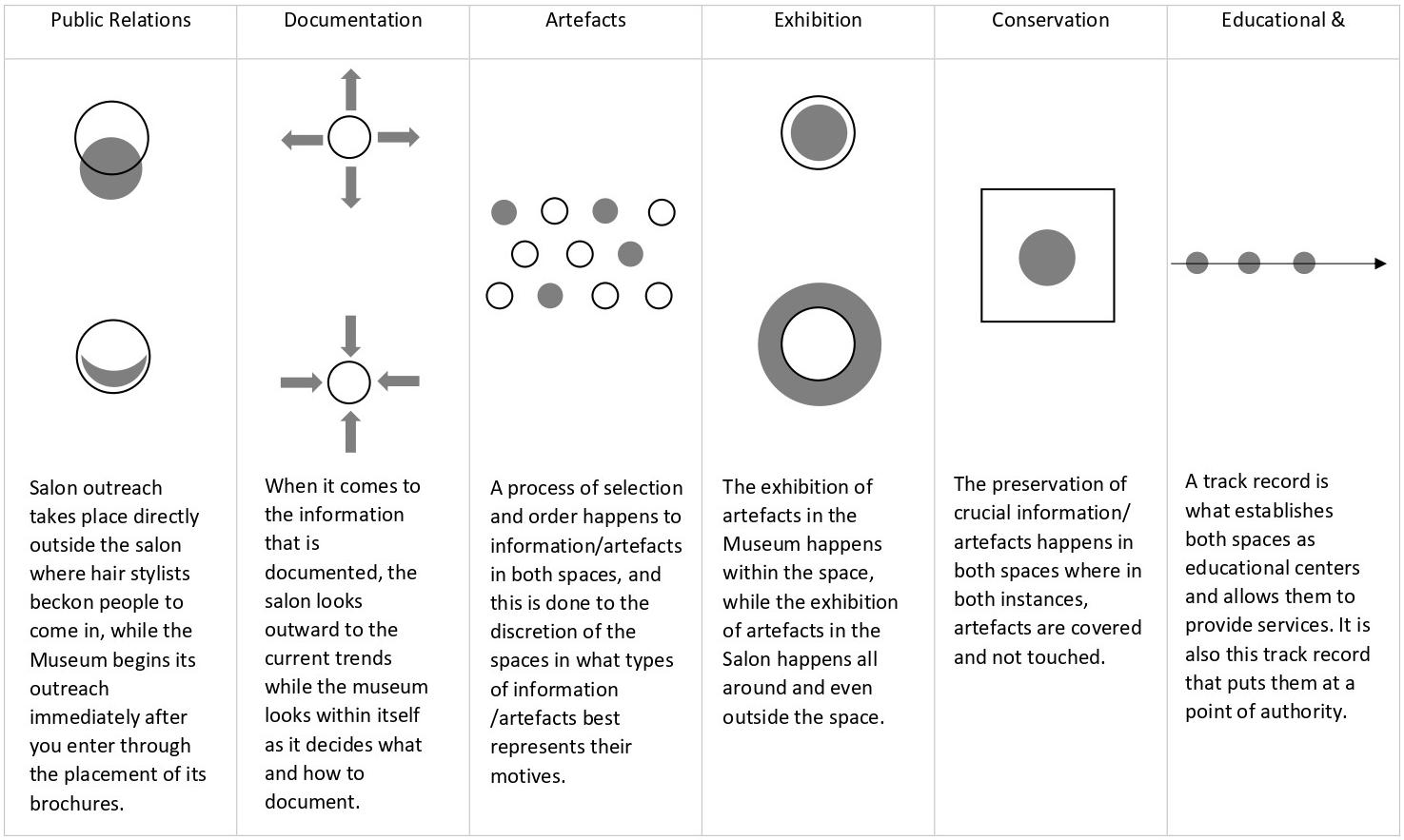

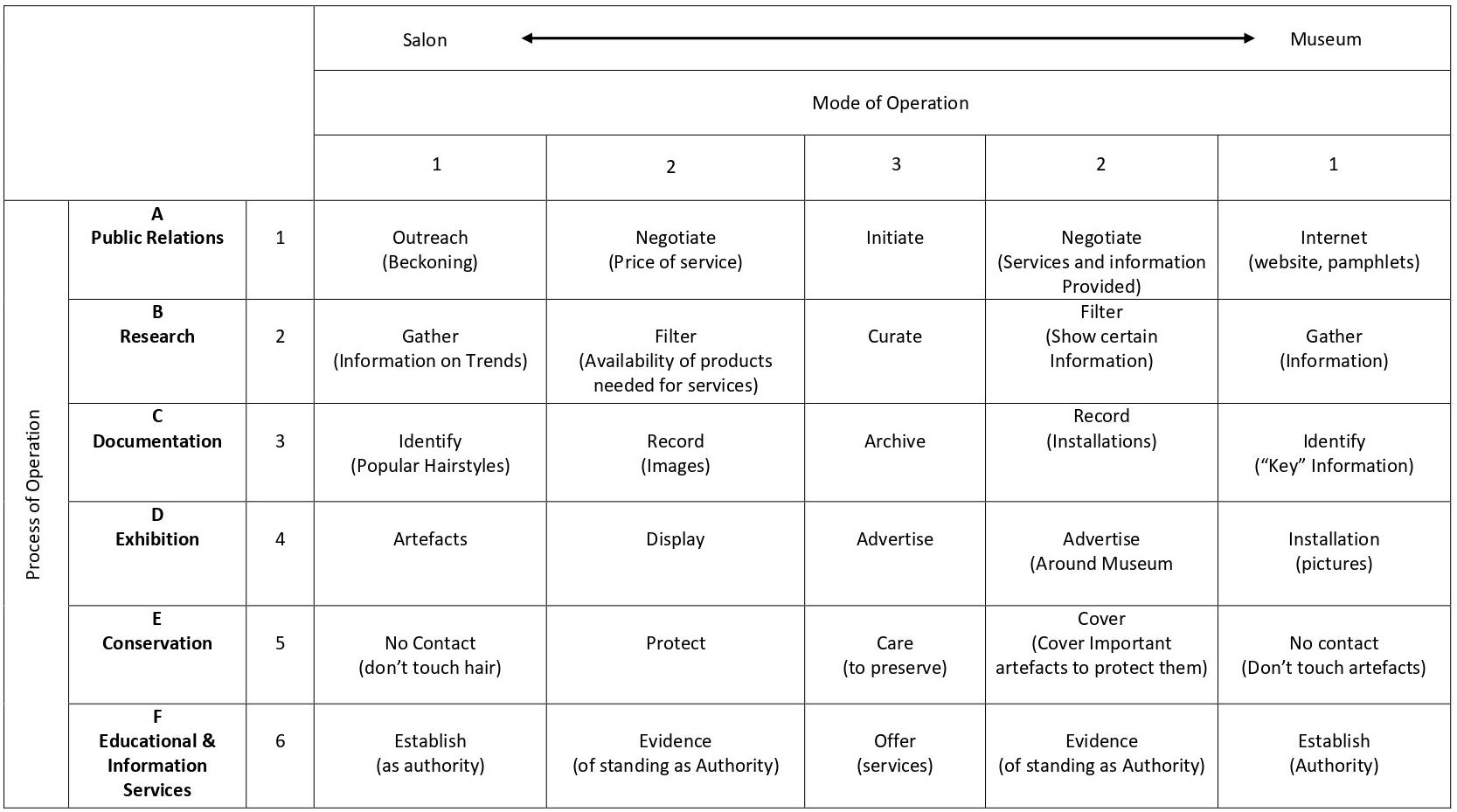

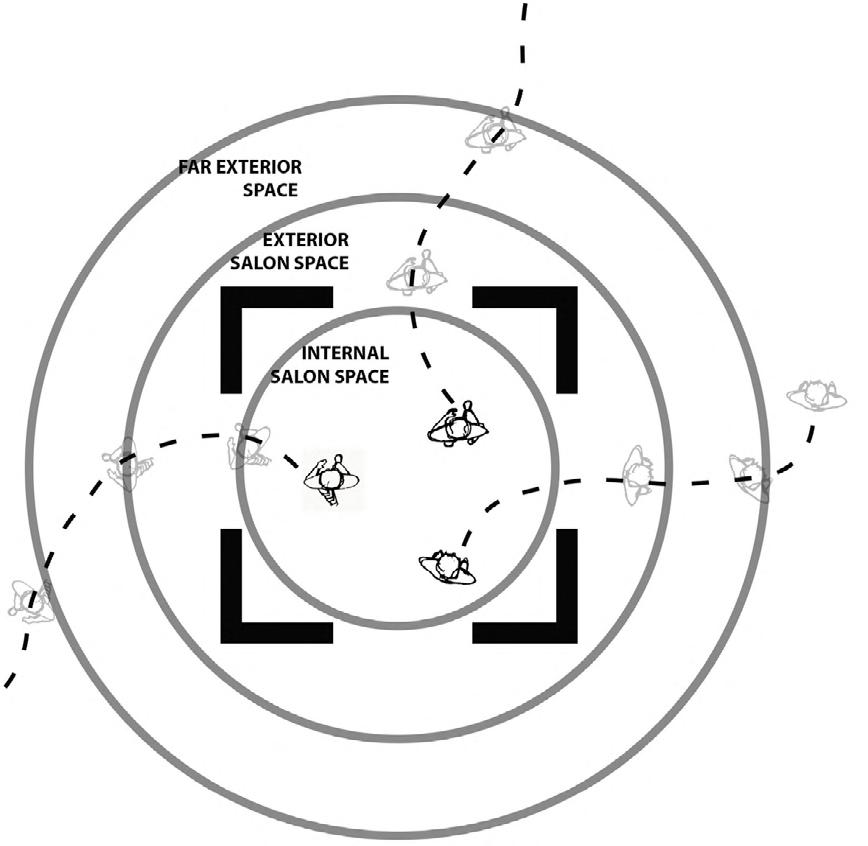

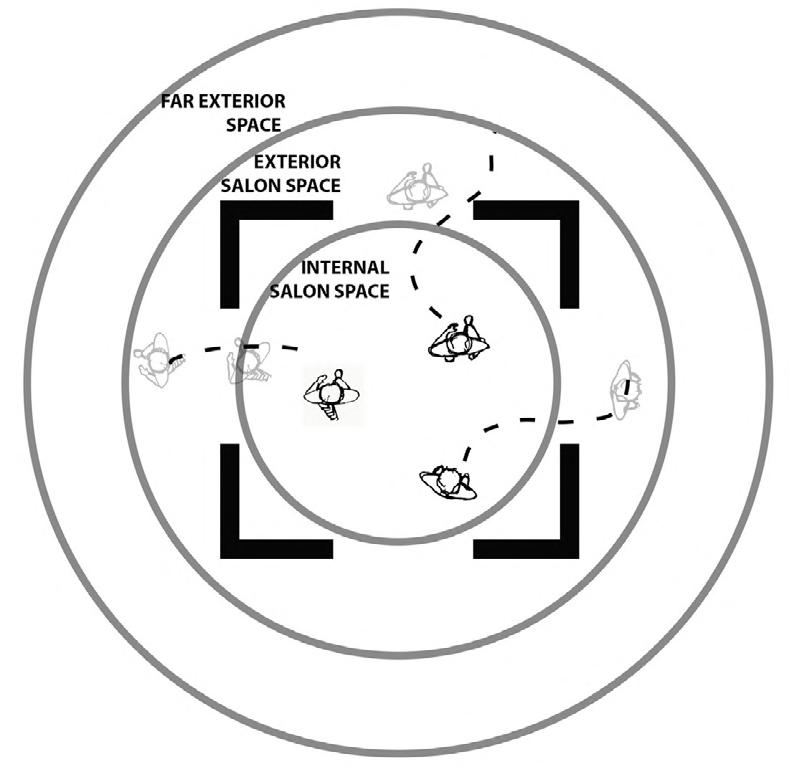

Using her personal hair salon as my primary site of study, Nobuhle’s work approaches the salon anthropologically and unravels the various façades that make up the space, how they operate and all that it perpetuates through various visual clues and mechanisms of engagement. In this way, the work makes a distinction between conscious experience and subconscious messaging as it reveals how hair salons act as institutions of modern beauty ideals that assimilate marginal identities into western hegemonic identity.

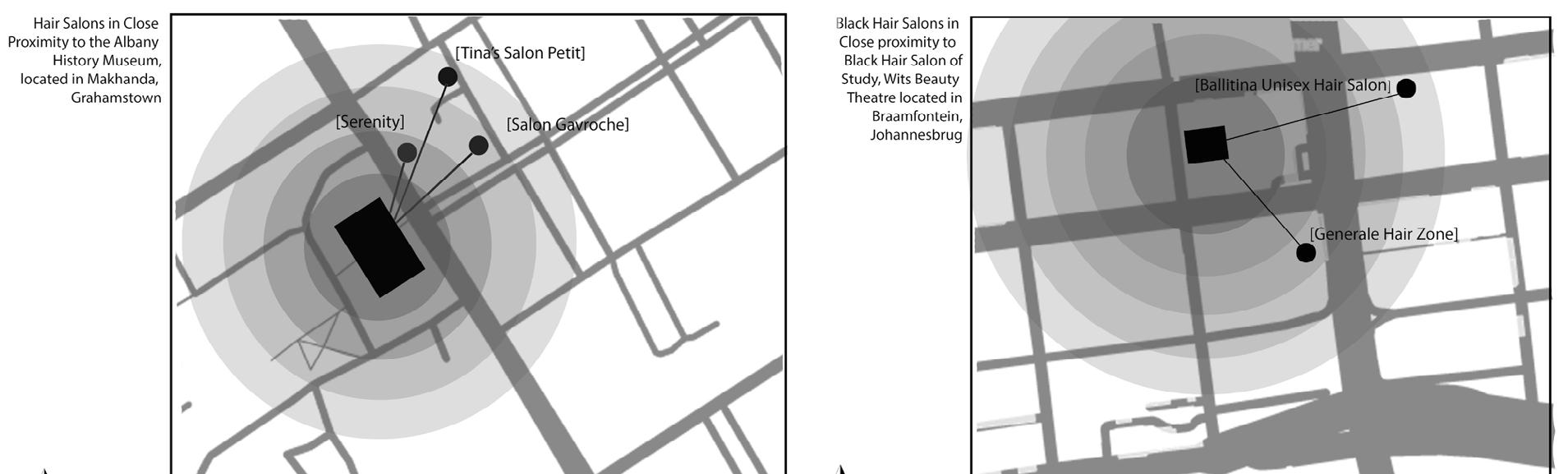

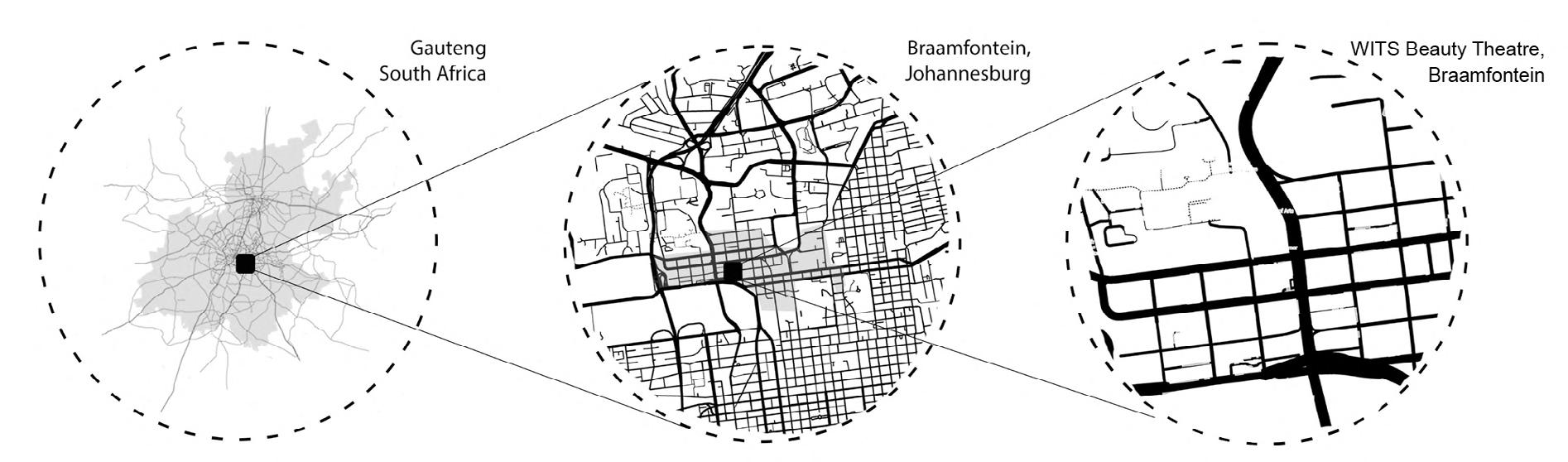

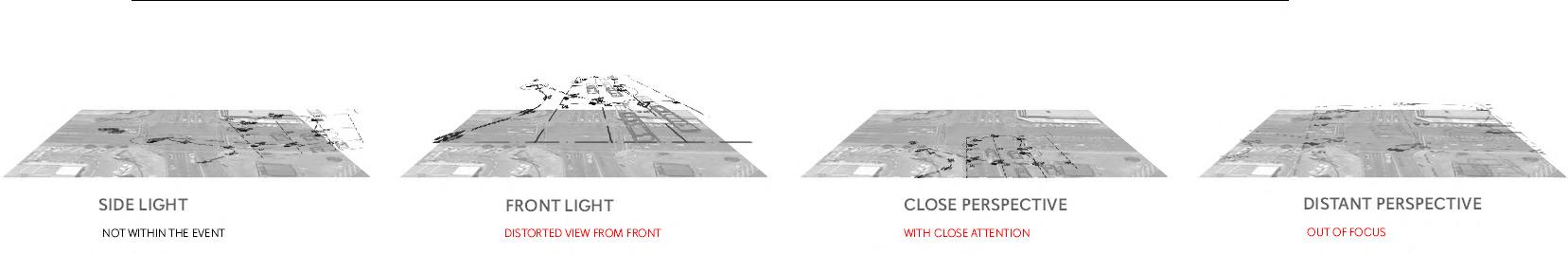

Treating the hair salon as a mirror to museum spaces, in how they both statically and actively preserve global beauty standards, the project intervention gets sited in the Albany History Museum in Makhanda, Eastern Cape. Its lexicon and cataloguing tools are appropriated to reorient our subconscious proximity to hair salons by relocating its practices and reframing them as an archived museum display, to fix in time a more honest rendition of the innerworkings of such spaces, and in that way, to critique what museums define as ‘accurate’ recordings of culture.

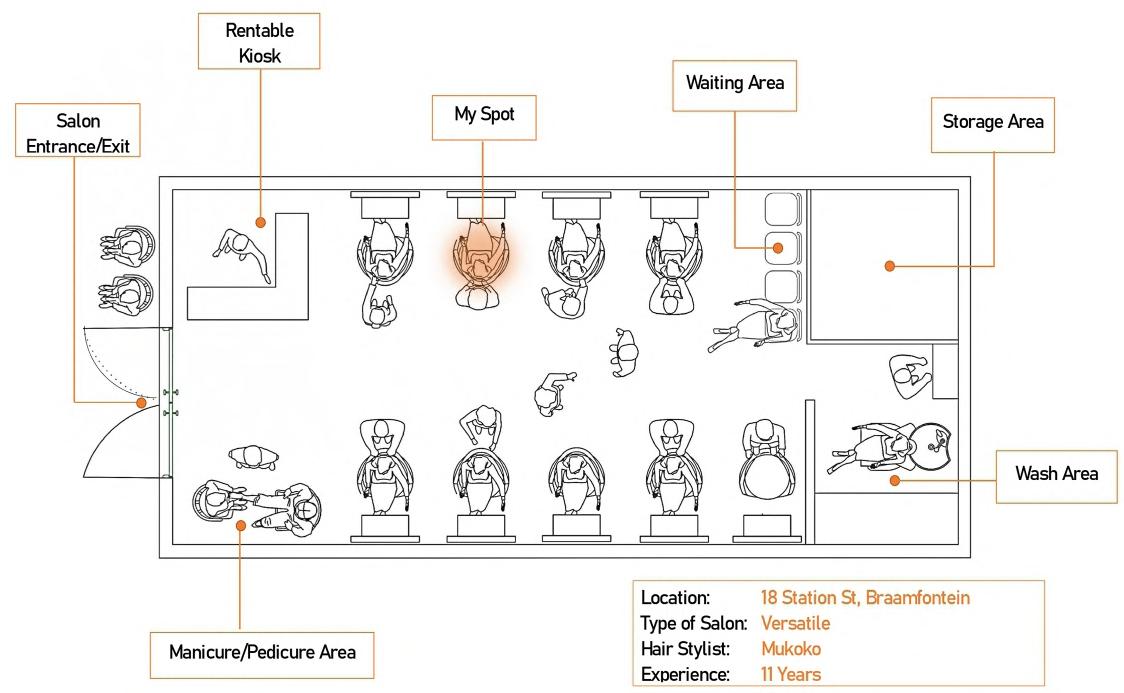

Nobuhle’s research interest lies in the relationship between space and identity, through the political signifier of black hair, and approaches architecture as a homegenizing image-making tool.

Nobuhle has a complex relationship with her own hair, as its versatility, Eurocentric leanings, and sometimes lack of distinct natural character have become sensitive sites of contestation for her.

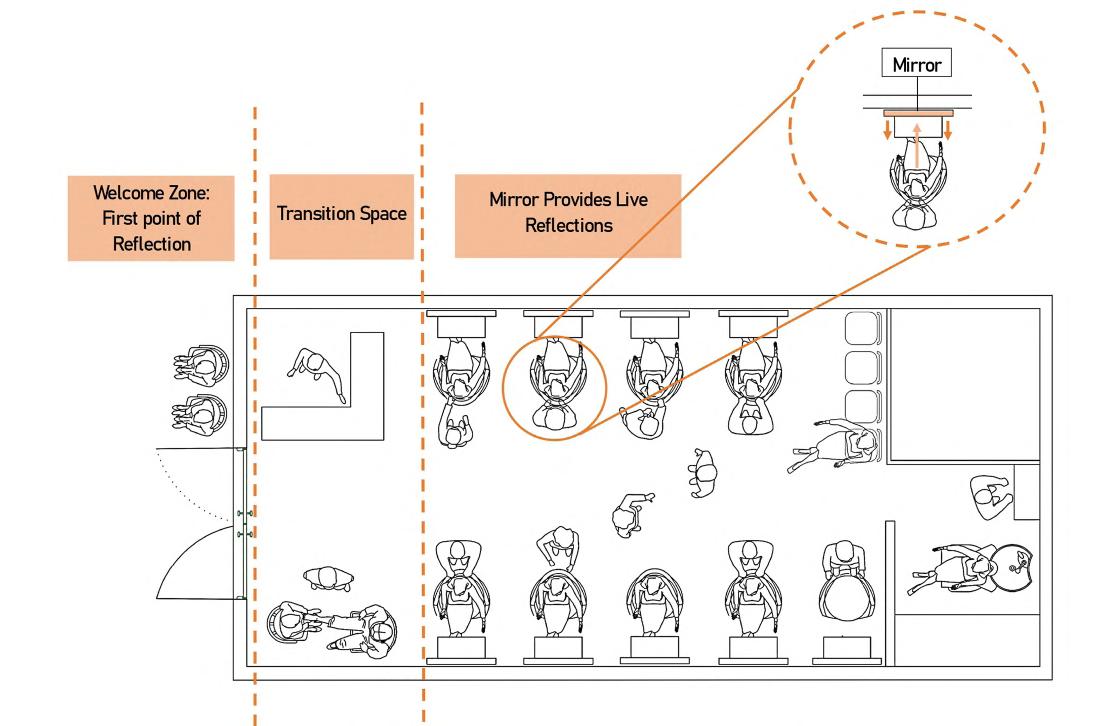

Her research starting point was her personal hair salon, called the WITS Beauty Theatre in the Johannesburg Central Business District (CBD) where, through an anthropological frame, she treated it as an image factory as it produces, maintains, and reinforces Eurocentric beauty standards and stands as a credible authority, catalogue, and archive (both live and recorded) of ‘universal’ beauty standards. The salon’s system of operation was then paralleled to the work’s chosen site of intervention, namely the Albany Museum in Makhanda, Eastern Cape, due to its overlapping social function as a credible authority, catalogue, and archive of images of our past selves, which, in the context of the Museum, holds mischaracterizing reflections of black primitivity and non-belonging in the context of modernity. The museum is also explored as an image factory.

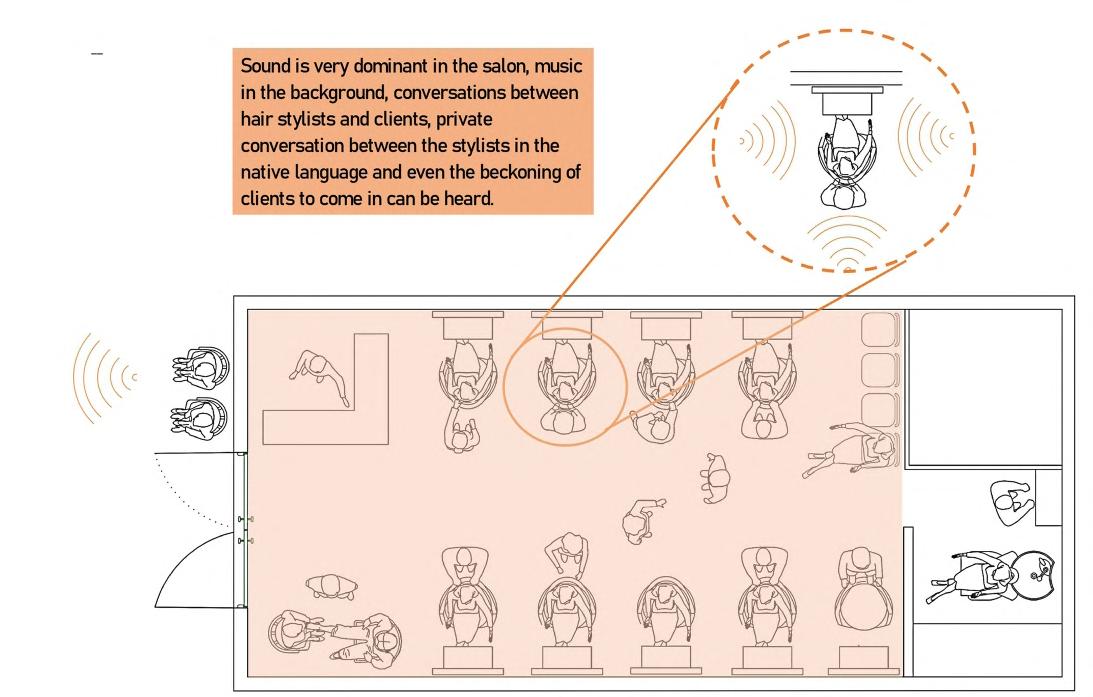

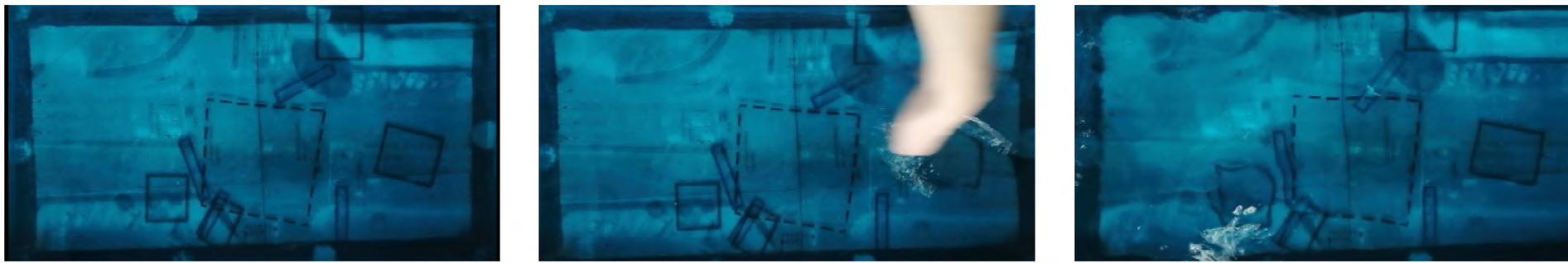

In one of her many explorations, she highlighted the mirror in her salon as a device that produces live projections. She personified hair as she reimagined the salon as a war zone that reflects the casualties after the day’s battle against the kinky characteristics of natural black hair. Due to her experience of tension and strain when she gets her hair done, she renamed different processes of taming her natural hair through the lens of subduing war tactics, that include the hair dryer as firepower, which in the military refers to the capability to direct force upon an enemy.

She also reimagined the hair salon as a graveyard for both the hair, and along with it, one’s ability to hold an unadulterated sense of self-identification.

She built a 1:1 model of the conditions within her hair

salon, which presented great immersive possibilities for her work as she worked with sound, signage, and mirroring in various iterations of the installation, all tactics that are employed by the salon.

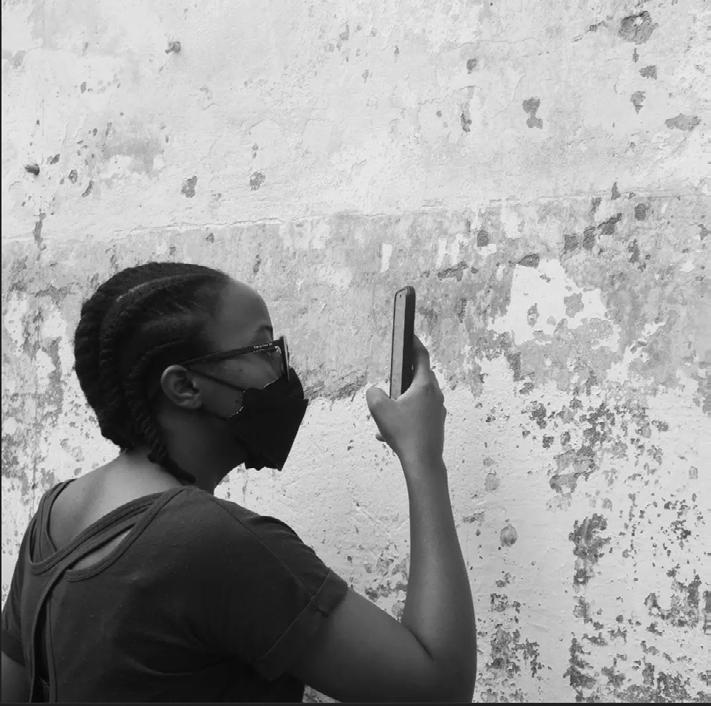

The visit to Makhanda further inspired her interest in image-making through her experience at the Albany Museum. She explored the Museum as an extension to her research site of the salon, and investigated the role the Museum plays in producing and maintaining a false but seemingly real image (as it categorizes itself as an accurate record of history) of the black population of the Eastern Cape province across time. She documented the display tactics of the Museum’s exhibitions to better understand its image-making construction tactics.

Nobuhle took interest in the codifying tool of museum cataloguing as an apparatus that legitimates very scripted and curated images of cultural groups, and through this, explored the cataloguing capacity of the hair salon as an overlapping exercise.

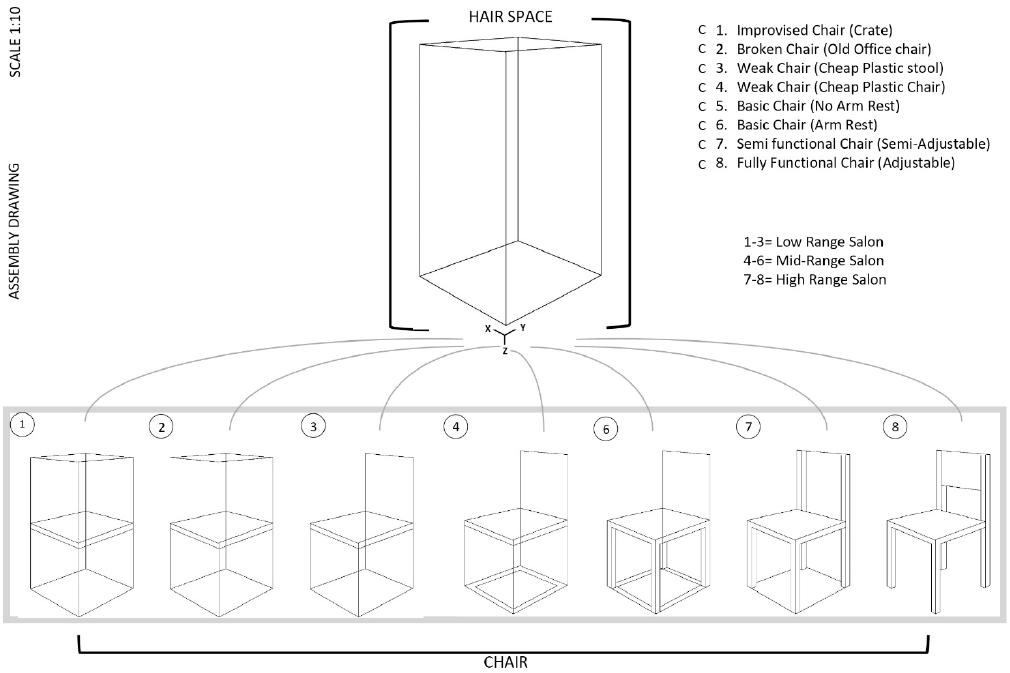

Nobuhle investigated class tiers of hair salons, and their corresponding means of communicating identity. Some of that investigation included the study of chairs as the most primal salon infrastructure, where at the lowest economic scale, salons contain only a chair, the client as the table that holds the hair, and the hairdresser as storage as they hold their products in their backpacks on their persons.

It was important for Nobuhle to make a distinction between the conscious agency that salons afford black women in modern times, and the subconscious messaging that intercepts that conscious experience of agency. For this reason, she chose to extensively interrogate all of the visual messaging that she experiences from the salon as a series of façades, considering how imagery is literally used to plaster the storefront to become an actual façade. Nobuhle explored façading at four scales, and she languaged four zones of façading:

1. The first scale of façading is at the ideological scale, where ideal beauty standards are created at global scales and then disseminated through social artifacts

such as mainstream magazine covers that act as the walls of shop waiting aisles.

2. The second scale of façading is at the urban scale, where salon storefronts are plastered with these beauty ideals, and to support this, front-persons with placards of hairstyle ideas stand at the entrance of salons to add an auditory landscape to the overall spatial framework of allure. At this scale, Nobuhle ranked the faces most displayed, and studied their features as an urban scale façade study.

3. The third scale of façading is at the architectural scale, where the synthetic hair on sale within hair salons act as a wall finish as it plasters the interior, and the images of others reflected in the mirrors act as wallpaper extensions of the dismembered hair as a wall plaster.

4. The fourth scale of façading is that of the 1:1 ritual scale, in the very practice of identity reformation, where the performance of a new identity by those whose natural black hair has been tamed becomes an

added sell for interested observers.

Nobuhle’s proposition offers both the salon and the museum as Façade Banks. She offers a critique of preservation, as being synonymous with cultural production, and she offers a museumifying of her hair salon’s façades in its more truthful subconscious reality. This reflects, for instance, through the front-persons that call out to the women on the street, who are not only showing women hairstyles, but in fact target one’s sense of identity as measured against existing beauty ideals. So, rather than the placard as what gets displayed in the museum, the apparatus that measures these ideals is what gets put on display.

Nobuhle’s proposition attempts to conflate the meanings of memory- and identity-making, and then works to ‘defaçade’ its practices through exaggerated expressions of reality.

T-R: Salon Diorama (Second Iteration) [1:1] Installation wood B-R: Salon Diorama: Sound Nodes (1:50) Axonometric rendered line drawing B-L: Museum Catalogue Discrepancies (not to scale) Case Study archival photos and corresponding text B-LT-R

T-R:

Museum: System of Operation (not to scale)

Diagrams line drawings

B-R: Salon and Museum: Mirrored System of Operation (not to scale) Mirroring Table line drawing

T-L: Architectural Scale Façade (multiscalar) Axonometric and Analytical Perspectives photo series with contrast

B-L: Ritual Scale Façade (multiscalar) Analytical Perspectives photo series with contrast

R: Chair as Salon (1:10) Comparative Study line drawings

Urban Scale Façade Study (1:5)

Cross-Section photo series with contrast

T-R B-R

T-R: Locating WITS Beauty Theatre (multiscalar) Maps line drawings

B-R: Proposed Assimilation Room (not to scale) Perspective collage

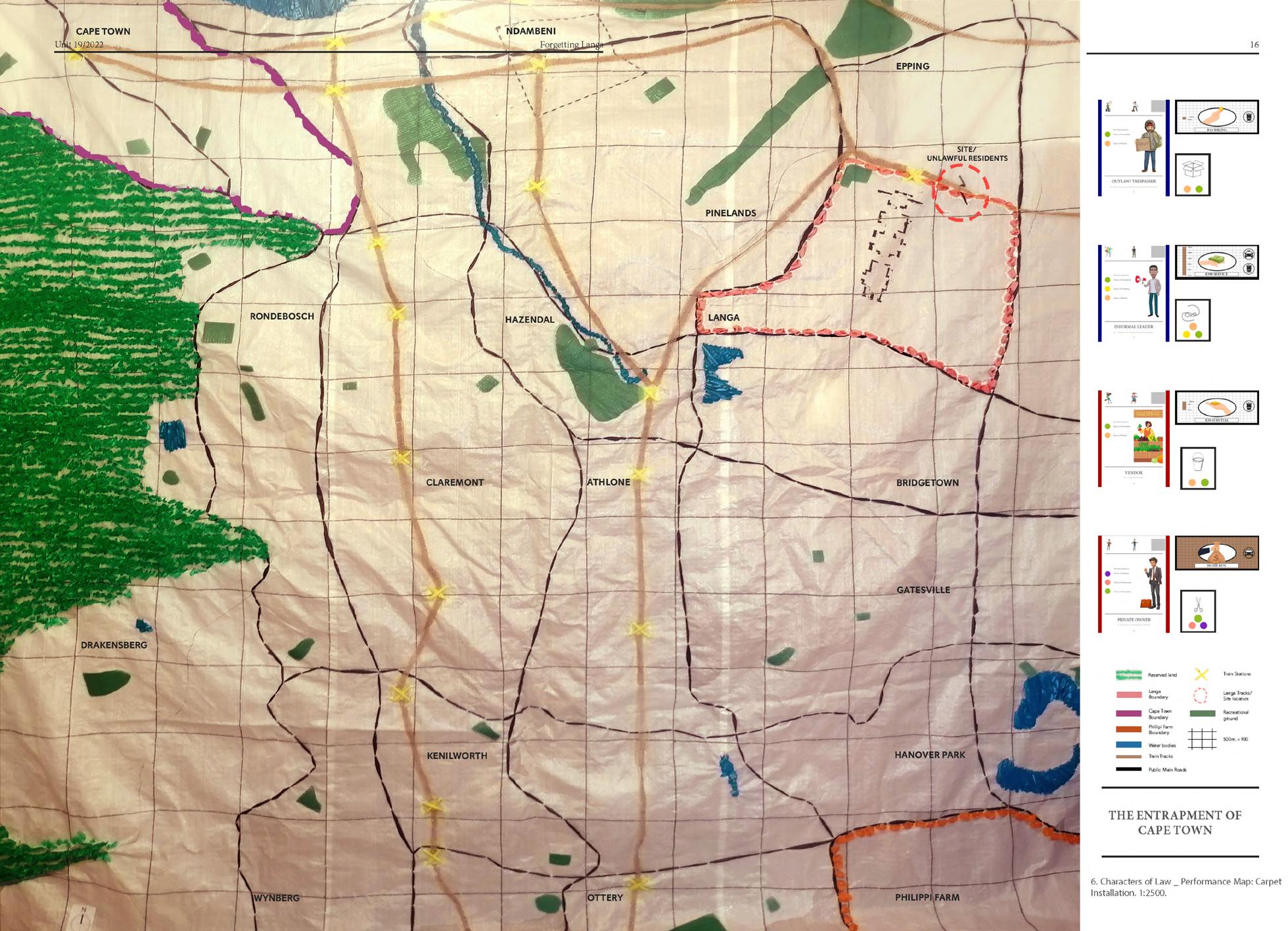

SITE: Langa Township, Cape Town, Western Cape

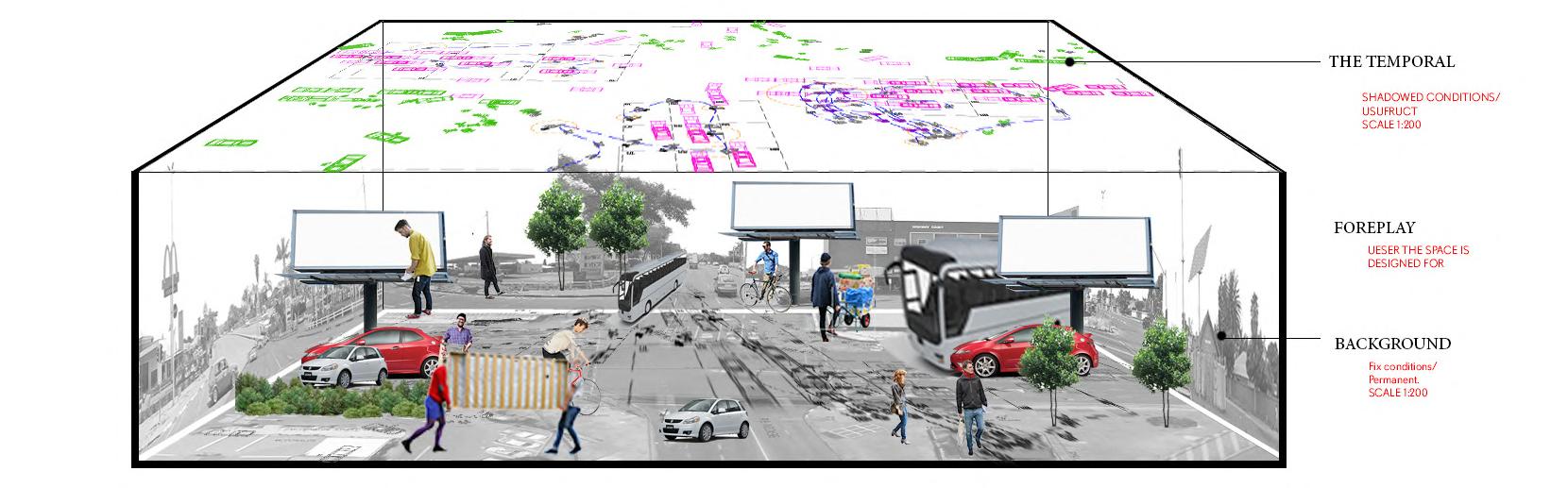

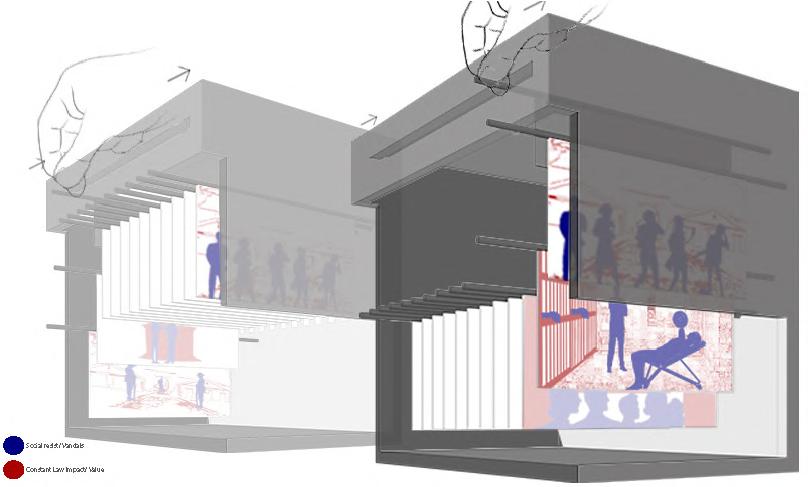

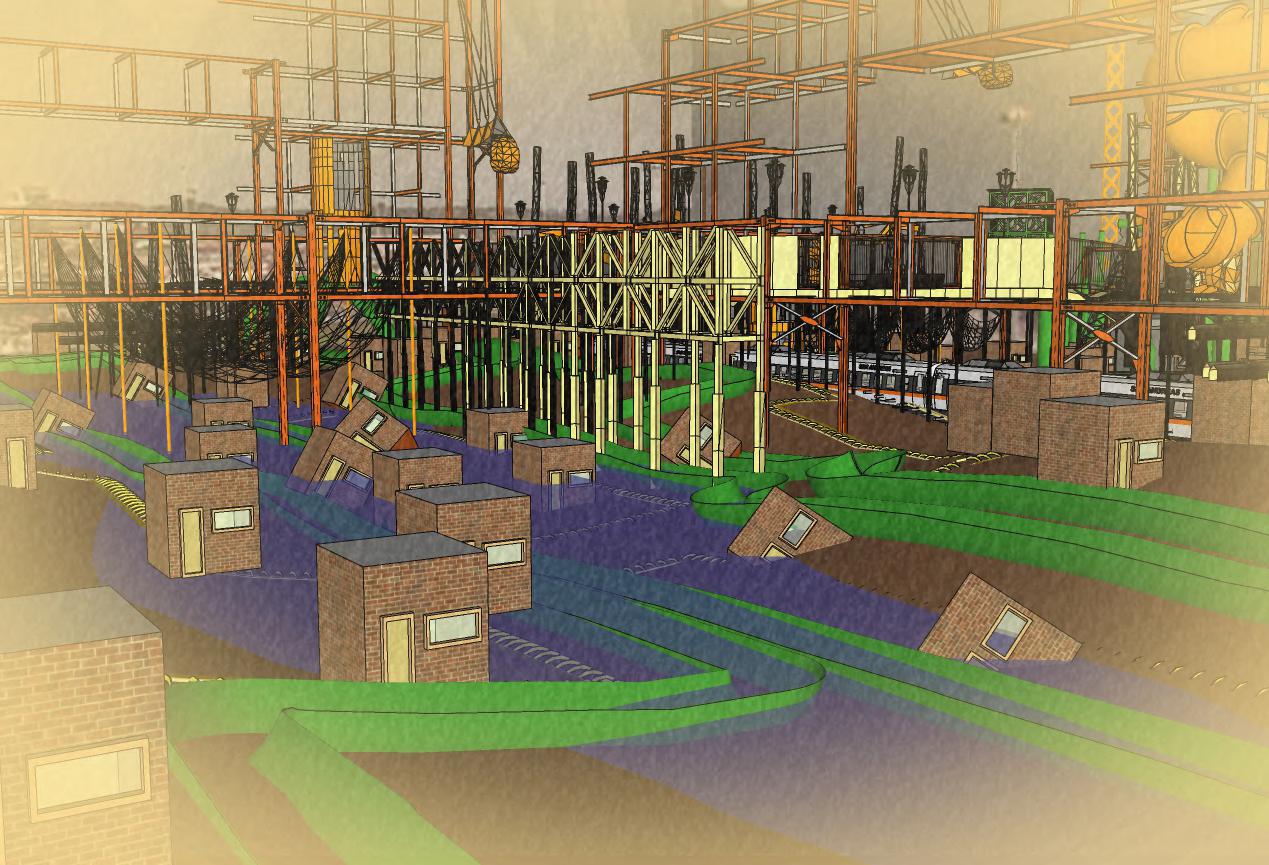

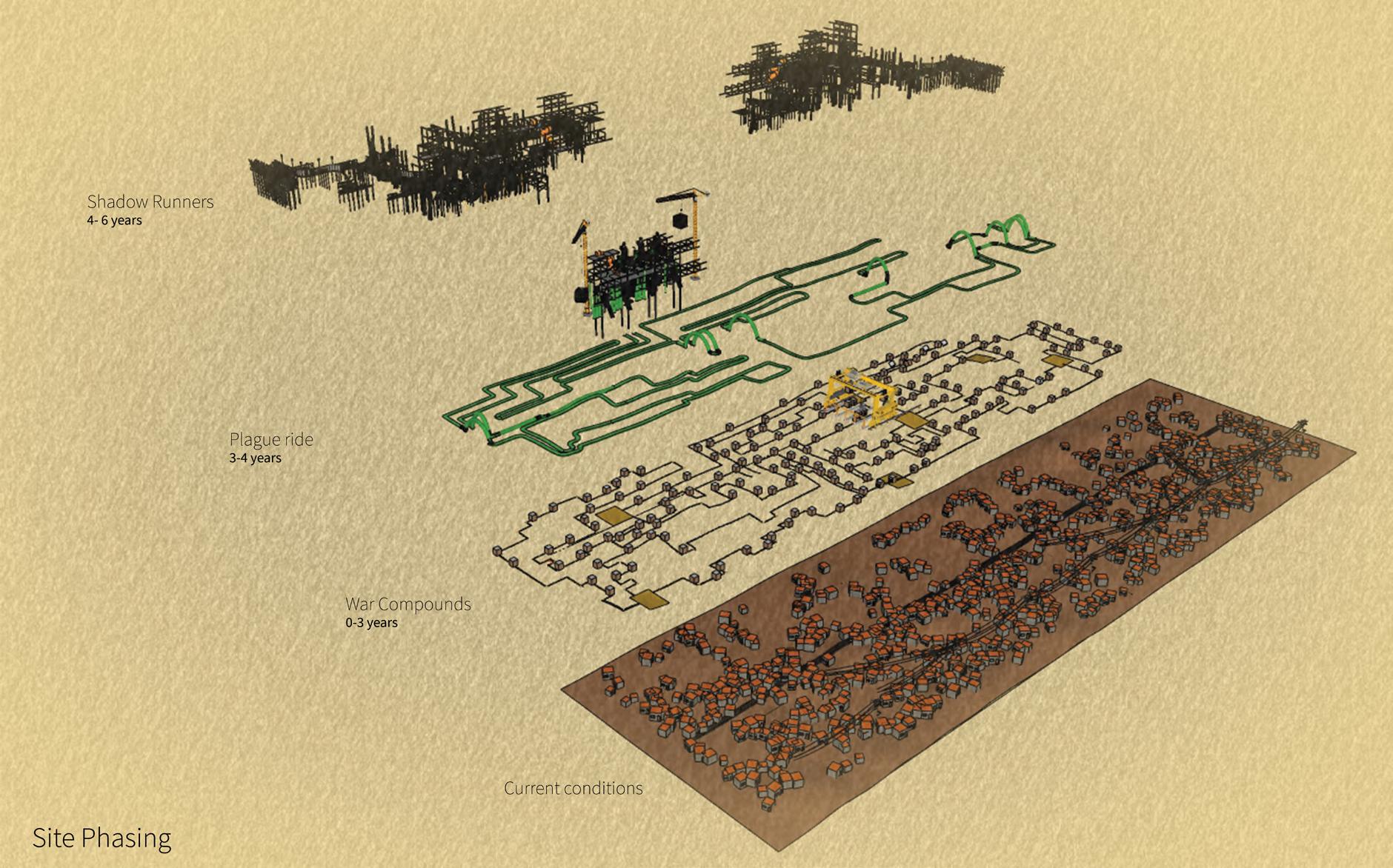

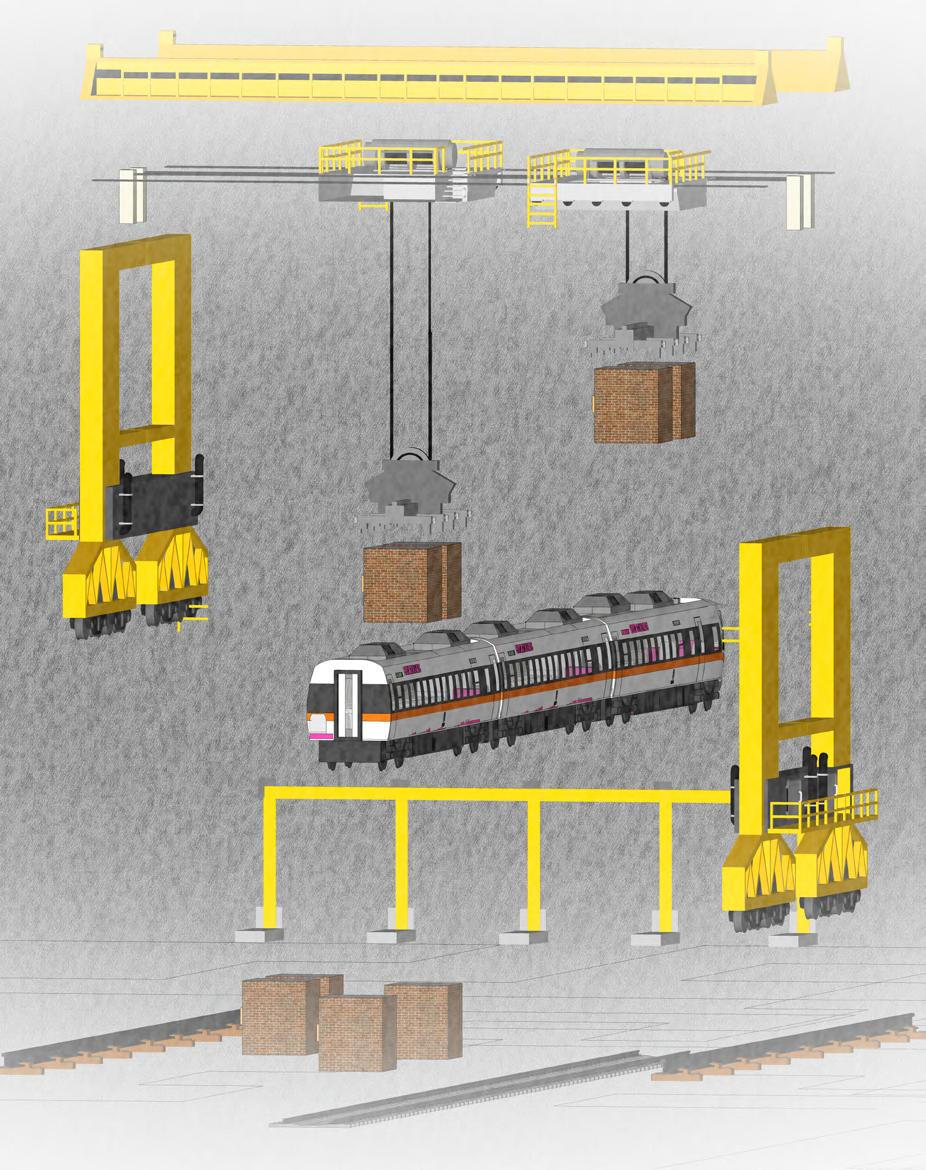

The work approaches architectural practice as the process of museumification, as it produces static programmatic conditions whose aim is for built fabric to endure rather than adapt to societal changes, erasing both what was and what could be as it insists on what must be. This practice produces what can be termed ghost-town conditions, or anti-resilient landscapes.

The work defines architecture as the law that structures and guides the behavioural rhythm of society, and the work traces how architecture-as-law imposes normative and acceptable conditions of time.

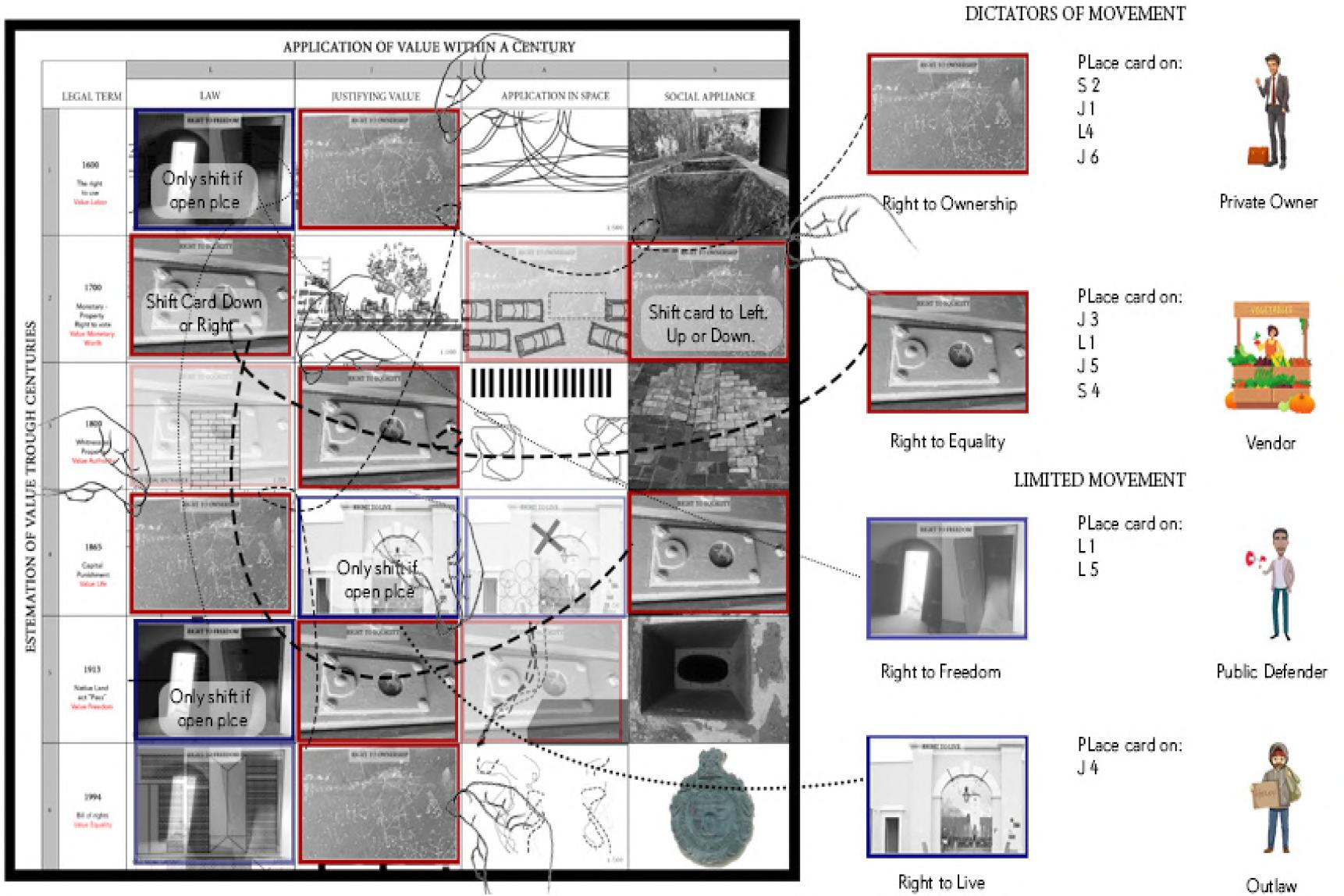

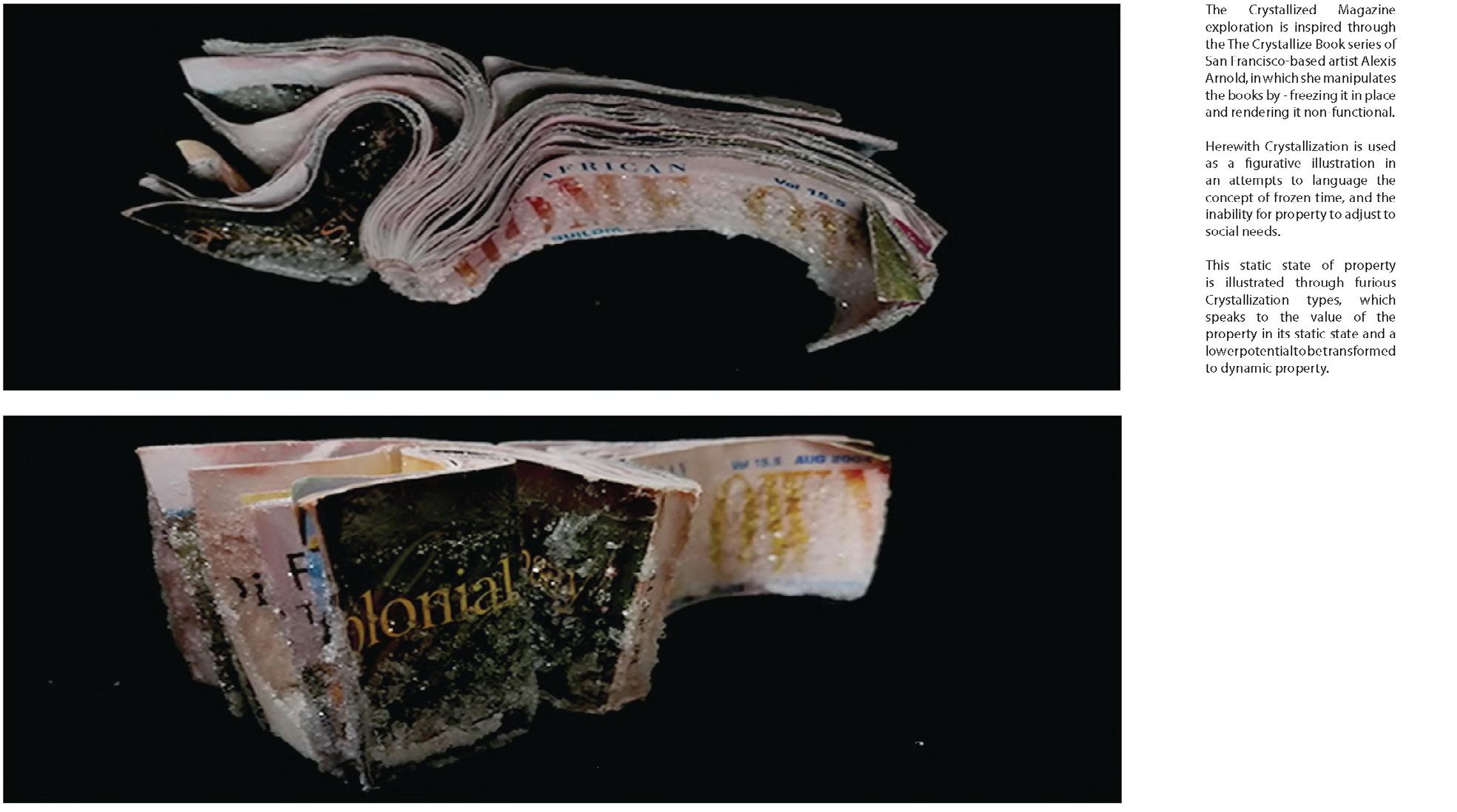

The work focusses on the Usufruct Law, and its capacity to render static-ness (or exclusive private ownership) dynamic and mobile. Due to the law’s ambiguous characteristics, ‘latent ambiguity’ law practices are able to be implemented in how it is applied in practice. Its vague definition of the terms ‘value’ and ‘vandalism’ determine the scope of the research endeavour.

The project site of interest and intervention is the Langa Railway Tracks in Cape Town, owned by PRASA, which is occupied by over three hundred unlawful residents with a pending eviction order.

The work proposes alternate ownership possibilities, by reconfiguring this static conception of ownership, and introducing notions of dynamic property in an effort to legalize their presence.

The research is conducted through model building, videography, and drawings that allow audiences to experience architecture’s social structuring capacities.

Marilize’s thematic interest is about the private property law called the Usufruct Law, which gives the ability to temporarily hand over private property ownership to someone or an entity who must add value to the property and not vandalize it. The ambiguous terms, ‘value’ and ‘vandalism’ in its definition became a focussed source of research inquiry for Marilize throughout the year, as those meanings are dependent on individual interpretation in the Usufruct Law, and State interpretation in the Eminent Domain Law1 (which stands as the the public realm version of the Usufruct law).

Marilize takes great interest in the extreme dynamics between (mostly privately owned) abandoned urban infrastructures in relation to sections of the public realm that are able to routinely hold a multiplicity of programs at the same time, such as traffic stops and public parks.

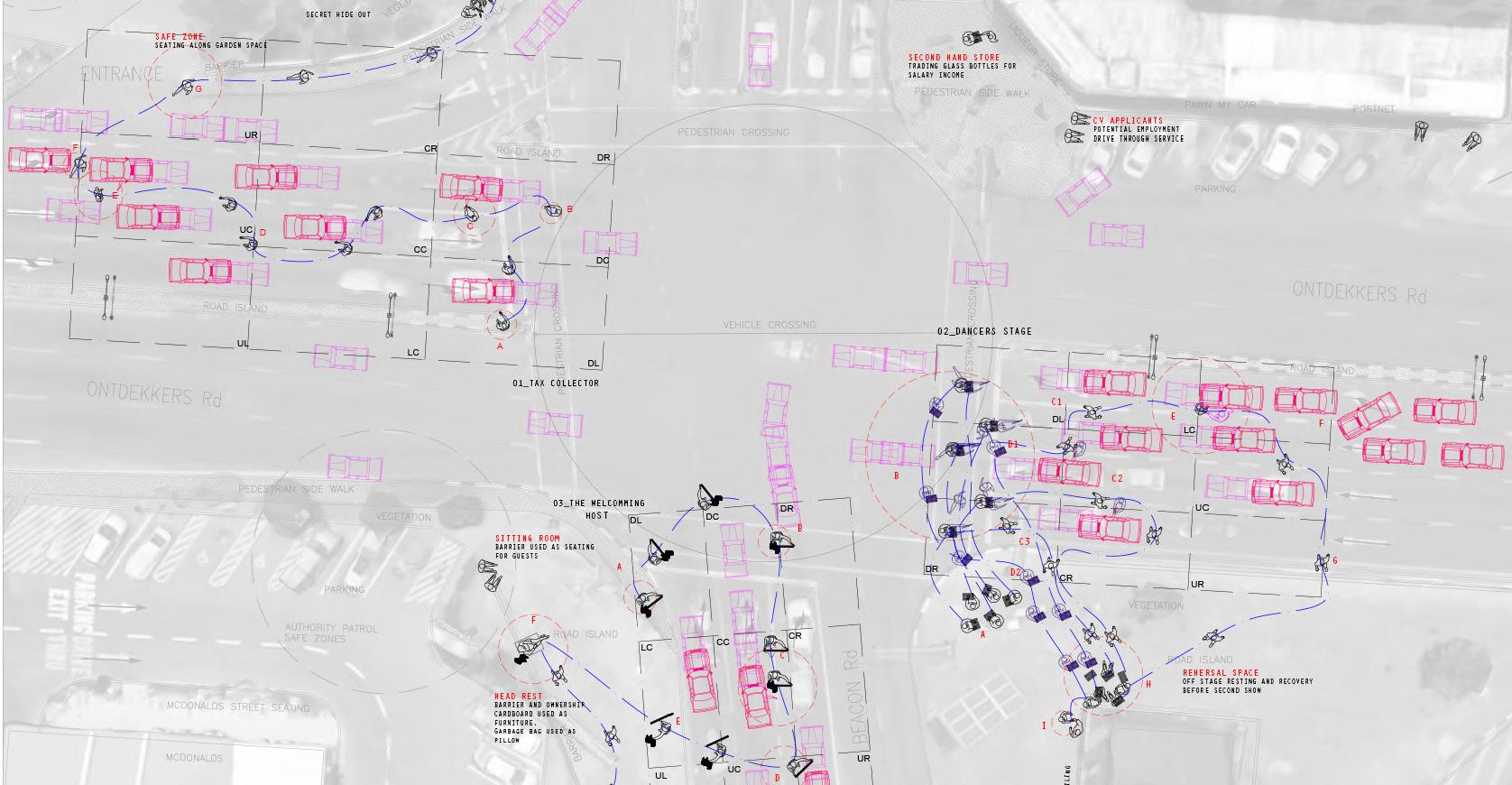

In her first inquiry of the year, she notated the rotational programmes at a traffic stop that she drives through everyday through a 3-tiered diorama. The rhythm of the traffic lights dictates the programmes’ rotation and duration cycles, and her work approached those rotations as performances with front, centre and back-stages, and scripted us through those cycles at their exact speeds.

She extracted four key characters in the cyclical performance of this dynamism:

• salespeople; who she terms Buskers in the work, and are socially positioned as value-adding while legally positioned as vandalizing/trespassing,

• performers; who are termed Entertainers in the work, and are legally positioned as vandalizing/ trespassing,

• beggers and ‘trolley pushers’2, who are termed Cleaners in her work, and are socially and

1 “The right of a State to expropriate and transfer a property to a third party, to benefit public interest or public purpose” (Britannica, 2019). This concept is further defined and unpacked by the South African Professor of North-West University, faculty of law, Elmien du Plessis (2021) in her article No Expropriation Without Compensation in SouthAfrica’s Constitution – for the Time Being (Du Plessis, 2021). She articulates that South Africa has adopted the concept of “just and equitable” compensation within the Expropriation Act, however, the Constitution fails to articulate what is defined by the State as “just and equitable”. In 2021, the latest Constitution Amendment Bill stated that expropriation for land reform purposes may be nil, “that the land is the common heritage of all citizens that must be safeguarded for future generations, and that certain land can be placed under State custodianship for citizens to gain access to land on an equitable basis” (Du Plessis, 2021). Despite this, the distinction between public interest and public purpose remains undefined within the legislature (Du Plessis, 2021).

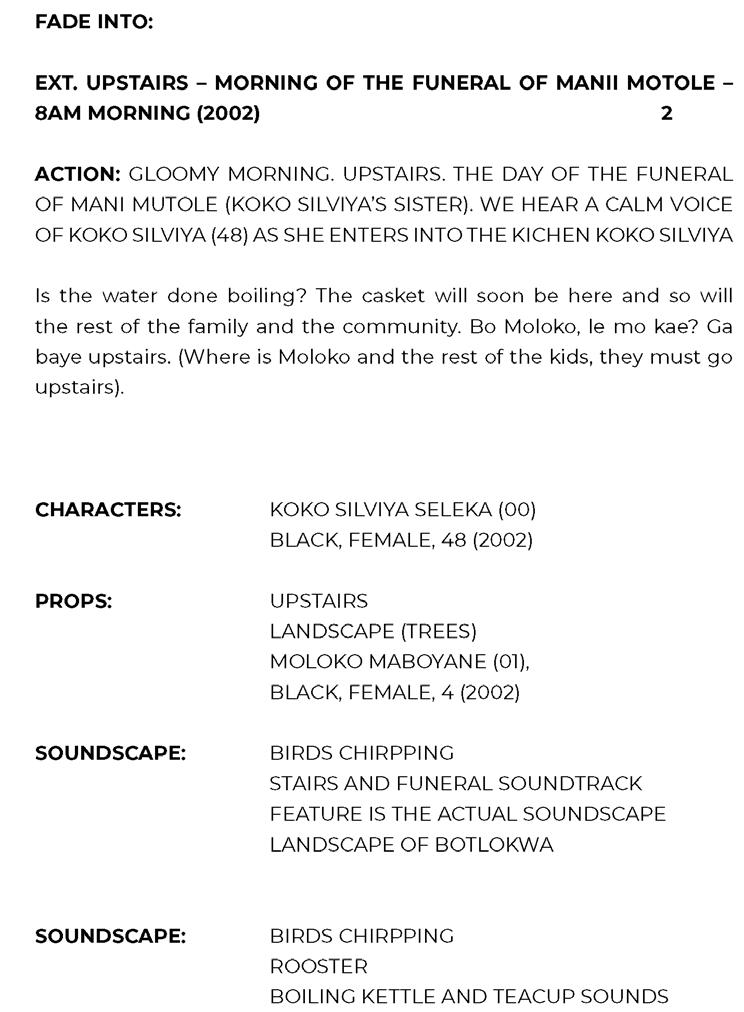

2 This term refers to the independent network of recyclers across South Africa that comprise some of the most economically marginalized people in the country. Their self-driven service contributes greatly to the country’s annual GDP, yet they remain under-served, scrutinized, and mistrusted by the State.