Underwater photography has always been an integral part of diving. Early scuba pio neers like Hans Hass (pictured here) and Jacques Cousteau knew they could tell com pelling stories only if they visually documented their underwater adventures. So, they developed and used underwater cameras almost from the beginning.

In the early days of underwater photography, divers could take only a single exposure before surfacing to change their burnt-out flash bulb. I imagine they carefully selected the motif and settings before firing that shot.

If you’ve been diving for more than twenty years, you can probably remember when un derwater photographers were limited to 36 exposures and by the film’s ISO properties. The interval from when the image was shot until you returned from the dive trip and got the film developed could be weeks. And, when you did get your finished photos, you most likely did not even remember which settings produced the result.

Fast-forward to the evolution of the digital consumer camera—a blessing for underwater photographers. With digital, the feedback is instant. You immediately see the result on the camera display, and you can adjust accordingly to improve the shot. And you can glean valuable and useful information from the embedded EXIF file.

Digital photography and YouTube—a medium that has propelled almost all human endeavors into the stratosphere by making nerdy knowl edge more accessible—have raised the bar for contemporary underwater photos. But, at the end of the day, it’s not about the camera, the lens, or megapixels. It’s about visual storytelling. How does the image resonate with the specta tor? How does it make them feel?

Tabloid journalists used to say that all stories can be boiled down to two opposite re actions: “I’m so glad that’s not me,” and “I wish that was me.” I usually try to evoke the latter when working with images as a photogra pher or magazine editor.

The portfolio pages in Quest are an homage to underwater photographers and visual story telling. I understand the energy and resources it takes to reach the quality level embodied by the portfolio contributors, so I appreciate the oppor tunity to highlight their work.

We have come a long way since Hass and Cousteau, but the game is still the same: Creat ing images that make the spectator go, “Man, I wish that was me.”

Dive safe and have fun!

Jesper Kjøller Editor-in-Chief jk@gue.comIn each issue of Quest, the new Director of GUE Quality Control, Brad Beskin, will contribute with a regular column. He will address issues, opportunities, and resources that affect your pursuit of diving excellence.

Arzukan Askin is one of the driving forces behind shark projects in the Maldives to raise awareness of the problems with human impacts on whale sharks, tiger sharks, and other endangered shark species in the atoll nation in the Indian Ocean.

The possibility of finishing a long and deep cave dive in a dry habitat is appealing. However, whether to install one is a risk-versus-benefits decision. After spending a fair bit of time on decompression stops in water and in habitats, Kirill Egorov shares his habitat experiences.

His passion started when snorkeling in his local dive club in Germany. He then started discovering the underwater world in many ways. In the early 2000s, he was finally able to take his photography below the surface, capturing his first real pictures underwater.

In addition to the standard base equipment necessary for all dives, GUE divers often carry extra equipment that can be situation dependent.

In the last issue of Quest, Guy Shockey’s article guided

Istarted diving in 1995 in Virginia Beach, Virginia. I was twelve at the time, and it hooked me quickly. I spent my weekends vacuuming the pool at my local dive shop, cleaning the shop bathrooms and floors, and organizing the fill station line—anything to earn any possible opportunity to become a better diver. I worked for that shop in a part-time capacity through college. I have sold the highest quality retail equipment, filled countless tanks, and blended liters upon liters of gas. I have vacuumed the pool more times than I can count, cleaned rental equipment, and rebuilt many a regulator. I have taught and refreshed students. I have crewed dive boats, swabbed the decks, and repaired many a marine head in nausea-inducing swells.

I share this in an attempt to assure those of you who make a living through diving that I understand and appreciate the hard work and long hours you put into your success as a diving professional.

My first exposure to GUE was a chance en counter with GUE Founder and President Jarrod Jablonski in about 1999. He visited Virginia

Beach to speak to and dive with our contingent, and as an over-zealous sixteen-year-old, I of fered to be his chauffeur. To say that I pestered him with incessant questions is an understate ment. Of course, the impression he left was inspiring and lasting.

I took Fundamentals in approximately 2002, and then Cave 1 in 2003. After a bit of a break from technical and overhead diving, I requalified for Fundamentals in 2015 and retook Cave 1. Cave 2 followed shortly after, and I recently com pleted DPV Cave with Kirill Egorov (see Quest 23.3). While I have helium and decompression qualifications from other agencies, the GUE technical curriculum begins for me in 2023, and I’m very excited to experience it.

I share this in hopes of demonstrating that I understand and appreciate the hard work and long hours each GUE diver puts into their skill set—the endless drills and practice that must be part of our commitment to excellence. I have shared in the frustration and defeat that often comes on the second day of class, just as I have shared in the celebration when it all suddenly “clicks” on day five.

Greetings, Quest Readers! It is an honor and humbling privilege for me to have the opportunity to serve GUE and each of you in the capacity of Director of Quality Control and the Chair of the Quality Control Board. The Quest team has graciously afforded me a sliver of the magazine for what I intend to be a regular column. For now, I’d like to share with you a bit about my background and my goals for the GUE Quality Control program.

Brad stresses that his relationship with GUE is not as an attorney, even if he has a professional background as a lawyer.

I earn my living as a civil litigator. I work for a law firm based in Austin, Texas, where we represent injured parties across the country in an array of actions against, for example, manu facturers of defective medical, pharmaceutical, and consumer products; insurance companies who engage in bad behavior; and fraudsters who skim off the top of healthcare, defense, housing, and other tax-funded programs.

None of this matters, other than to juxtapose the following: I want to make it clear that my position vis-à-vis GUE does not make me GUE’s attorney (or that of any GUE representa tive). I serve in a wholly volunteer capacity, and nothing I say with regard to GUE is intended to be or should ever be considered legal advice.

Indeed, much of the skill set I intend to apply in addressing GUE matters comes not from my legal training but rather from a near-decade of experience managing nonprofit organizations (along with the risks and crises inherent thereto) before I went to law school.

I believe a key ele ment to the success of any organization is a congruence between its values and its output—be it services, products, or some other deliver able. True value con gruence is obtained when the value prop osition materializes in those deliverables—when why the organization exists is represented diametrically in what it does and how it does it.

“For example, just as it would undersell Apple’s value proposition to say “we make consumer devices,” to say “we teach people scuba diving” would grossly underrepresent GUE.

I’m sure each of you can think of the GUE values with which you identify most integrally. I imagine excellence is that which comes to mind most readily: teamwork, discipline, commitment, integrity, safety, conservation, and discovery. Each of you is a steward of GUE’s values. This is true for the novice GUE diver taking a primer as much as it is for the members of our Board. Each of you is responsible for the congruence between what we do, how we do it, and why we do it. GUE is an organi zation that leads with its “why,” and the “what” and “how” flow directly and necessarily there from. For example, just as it would undersell Apple’s value proposition to say “we make consumer devices,” to say “we teach people scuba diving” would grossly underrepresent GUE.

Indeed, we can look to GUE’s mission statement to see the “why” inherent to our “how” and “what”:

Global Underwater Explorers is building global communities of passionate divers, empowered by high-quality training and organized to support wide-ranging diving activities. These communities contain and partner with dedicated explorers, conservationists, and scientific researchers to conduct a diversity of aquatic initiatives around the world.

This congruence and why-forward approach are integral to GUE’s success and the prima ry metric by which I intend to manage the QC mechanism.

QC, to me, is not the simple application of Stan dards to substantiated facts and the calibration of punishments for deviations. While, unfortu nately, that is part of the job, QC must be more. To me, quality control (and my partnership with GUE’s quality assurance initiatives) is the stew ardship of GUE’s values congruence. In that, I perceive my job to be ensuring that what we do

and how we do it—both organizationally and in dividually—remains congruent with why we do it.

It is my belief that, broadly, when we lead with our why—the GUE values like excellence, com mitment, teamwork, integrity, and safety—quality control becomes inherently proactive and not reactive. That is, the instances where quality con trol must be reactive (and often punitive) are the direct results of incongruence between our why and what and/or how. If only it were this simple, right? Obviously, this involves many more fac tors than I’ve listed. But, at least conceptually, I hope that makes sense.

Of course, mistakes happen. But it is easy to recognize the difference between those mis takes—conduct from which we can learn and grow and move forward—and conduct that ignores our values. The former is a natural oc currence that can be minimized through proper risk management and often addressed through coaching, development, and other formative responses. The latter is inexcusable given the great risks associated with our endeavors.

To this end, I hope to be able to allocate much more of my time to advancing GUE’s many initiatives and addressing issues before they become conflicts—as opposed to respond ing to raging conflicts. I look forward to address ing positive feedback from students and how we can build upon it (both with our students and instructors). I hope to explore and celebrate the success of our instructors’ first few classes in teaching new curricula. I am excited to support the Training Council in finding ways we can improve the course materials to empower both GUE students and instructors.

In future columns, I will attempt to add val ue for you by addressing issues, opportunities, and resources that affect your pursuit of diving excellence.

Until then, I remain yours in the Commitment to Excellence,

Brad – brad@gue.com

“In future columns, I will attempt to add value for you by addressing issues, opportunities, and resources that affect your pursuit of diving excellence.

Brad´s GUE training has been focused on cave courses, but he plans to plunge into the tech curriculum next year.

TEXT ARZUKAN ASKIN PHOTOS ARZUKAN ASKIN, JONO ALLEN, MATT PORTEUS, ALEX MUSTARD & MALDIVES WHALE

TEXT ARZUKAN ASKIN PHOTOS ARZUKAN ASKIN, JONO ALLEN, MATT PORTEUS, ALEX MUSTARD & MALDIVES WHALE

Fuvahmulah is home to the world’s largest known population of tiger sharks. Arzukan Askin enjoys a close encounter.

German/Turkish marine scientist, GUE diver, and 2021 Rolex Scholar, Arzukan Askin is one of the driving forces behind the Miyaru Programme and the Fuvahmulah Shark Project being established in the Maldives to study and raise awareness of human impacts on shark species in the atoll nation and beyond.

Every whale shark has a unique pattern, almost like human fingerprints. In many coastal cultures, the spots are referred to as stars.

ehurihi!” Fehurihi! some one shouted pointing to the starboard side of the Maldivian dhoni, our floating research base in South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area. “Fehu rihi” is the word for whale shark in Dhivehi, the national language in the Maldives. After a year of pandemic-induced cancellations of grants, constant changes in risk assessments and per mits placed on hold, I was finally able to swap out my trusted seat at a library desk at Oxford University for my spot on board the field vessel of the Maldives Whale Shark Research Pro gramme (MWSRP) supported by a joint scholar ship from Rolex and the Our World Underwater Scholarship Society.

The South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area (dubbed SAMPA by scientists in the area) in the Maldives is a globally significant aggregation site for whale sharks. Unlike other aggregation hotspots that witness seasonal whale shark movements, such as Mexico, SAMPA is among

a handful of globally unique places with a year-long presence of large numbers of whale sharks. Past research led by shark experts such as Dr. Simon Pierce has determined that the sharks exhibit significant levels of residency and a tendency to return to sites on the southern fringes of the atoll. The frequency and regularity of whale shark sightings have also made SAM PA a popular destination for divers and snorkelers wishing to observe this species. In the Maldives, snorkeling and scuba diving tourism geared to provide whale shark encounters have grown rapidly and provide significant economic value yet remain largely unregulated.

My MSc degree in conservation science at the University of Oxford was almost exclusively dedicated to sharks where possible, covering critical issues such as illegal wildlife trafficking, bycatch of sharks and fisheries interactions, in ternational treaties, human-shark relationships, and tourism. The latter is what my research the sis focused on, and I spent my summer months

analyzing whale shark injuries from collisions with vessels as well as behavioral changes in these mega-vertebrates to assess the impact of tourism on them. The findings my research brought forward were highly concerning, and I had the opportunity to present my work at the Maldives Marine Research Symposium held by the National University. The dataset I analyzed— spanning over nine years of data from South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area—revealed a 52% decline in encounters with whale sharks and a staggering inju ry rate of 70%. Almost three-quarters of all whale sharks sighted in the atoll’s waters displayed grave injuries from vessel strikes. While working with these numbers on a spreadsheet was challenging, repeatedly witnessing the consequences of poor diving skills, failure to adhere to wildlife codes of conduct, and lack of regulation highlights the magnitude of the issue and the multi-layered solutions that are needed to address it. How is this possible in a Marine Protected Area? Well, SAMPA currently exists as a “paper park” with no management plan implemented to date by the island council or Maldivian authorities despite ongoing discussions between stakeholders—a stark reminder that effective ocean conservation starts on land. Many sharks, including whale sharks, were once actively hunted in the Maldives for their prized liver oil used to waterproof dhonis, traditional fishing vessels. The introduction of synthetic coating reduced this practice until the ban on shark fishing in 2010 brought it to a complete end.

to both macro and

skill adjustment, both of which lead to excellence.

the day cruising up and down the Marine Pro tected Area documenting the presence of whale sharks, vessel activities, and assessing the number of people in the water during encoun ters with these large vertebrates. Occasionally, we would also attach long ropes to the back of the boat to conduct tow surveys. Aside from the high-pressure moments when we would encounter whale sharks and attempt to conduct microbiome sampling of their skin using big cotton buds, being pulled through the water behind a vessel while attached to a rope was certainly everyone’s highlight. As scientists, we do many strange things in the name of data collection. Mostly, our work consist ed of freediving surveys to collect Photo IDs and identify the sex of the whale sharks to build on the MWSRPs long-term monitoring database. During every encounter, we also collected data on environmental variables in situ, including cloud coverage, wind speed and direction, sea surface temperature, and visibility. Crucial data, such as cyclical and climatic shifts, have also been shown to affect the occurrence and abun dance of whale sharks, and the individuals in South Ari Atoll in particular are now known to show monsoonal movements across the atoll.

Today, dhonis serve as dive boats, and in our case as our scientific vessels. Our days in South Ari Atoll were spent patrolling the atoll’s waters in search of these endangered sharks. We would wake up, transfer from our mother ship to the survey vessel, and spend the next eight hours of

Every evening, when it was time to enter all our data from the day into the MWSRP spread sheets, and then run the ID software to crosscheck for potential matches, I could not help but smile and think back to the role of space technology in the development of the technolo gy we now use for shark conservation. Did you know that for many island cultures in places with large seasonal aggregations of whale sharks, the unique spot pattern of these ani mals (resembling a starry night sky) has earned them the role of mystical connectors between the unknown ocean and unexplored space. The cosmological significance attributed to the ani-

“

All of this proceeded under the watchful and demanding eye of a prototypical GUE instructor. The course was well-tuned

micro

Whale sharks suffer greatly from the impacts of human activities. Maldivian diver and shark guide Lonu dives down to free a whale shark entangled in industrialgrade plastic waste.

A tiger shark approaches a diving vessel from below.

PHOTO BORI BENNET

PHOTO BORI BENNET

“In partnership with the island council, we will now be the first organization to conduct long-term comprehensive studies of tiger sharks in Fuvahmulah.

Underwater photographer Jono Allen captures a large approaching female tiger shark.

Underwater photographer Jono Allen captures a large approaching female tiger shark.

mal is also reflected in the local names given to them. In Madagascar, for example, whale sharks are referred to as “marokintana” (Malagasy: “many stars”). Likewise, the Javanese name for whale sharks is “hiu geger lintang,” translating to “fish with stars on its back.” The widespread per ception of whale sharks as swimming “undersea constellations” is not only part of long-standing oral traditions in coastal cultures but has also found its way into contemporary science. And here is where the magic happens: The spot patterns on each whale shark are as unique as human fingerprints, and the software applied by researchers to iden tify individual whale sharks was devel oped in collaboration with NASA astronomers and adapted from the star-matching algorithm used by the Hubble space telescope. Confirming the identity of a whale shark will never cease to be an exciting part of my work and continues to serve as a re minder that the natural world is interconnected in unexpected ways.

Photo IDs of whale sharks are also a critical tool that allows us to accurately track injuries and healing rates as well as observe behaviors over time. Most importantly, they provide a window of insight into encounter data that would otherwise not reflect the full picture of what is happening in SAMPA. My thesis showed that the encounters have declined by 52%. We are only seeing half as many whale sharks in South Ari Atoll as we used to… or do we? Photo ID data of the sharks still encountered in the MPA reveals that the area has not lost its sharks or experienced a decline in their population size. The same individual sharks are still present, they simply return to the surface significantly less, most likely due to disturbance from tourism. Many whale sharks have been displaying increasingly evasive behavior in the presence of boats and tourists, and while

encounters used to be several minutes long just a few years ago, allowing people to observe these gentle giants and swim next to them, today many whale sharks quickly dive down when approached by people and boats. The extent of human pressure on these sharks left some of our volunteers on board baffled when we logged more than 10 vessels—each with an average number of 15 tourists on board—crowding one whale shark.

Over the next weeks, similar stories unfolded and our concern for the sharks grew steadily when we observed count less vessels speeding through the MPA, injuring sharks in the process. Ironically, most of these vessels are speeding to quickly reach a whale shark sighted by other boats. Recommendations by research groups and online campaigns across the Maldives have raised some awareness of this issue, but without enforcement by rangers or the threat of fines, it has proven challenging to prevent boats from doing so. The case of SAMPA highlights global lessons regarding the uncertain future of this endangered species. Like many other areas with large numbers of whale sharks, SAMPA too provides critical habitat for this rapidly declining shark species and if managed well, can contin ue to serve as a critical nursery site for juvenile whale sharks. Not only does the current pressure from tourism impede their feeding and thermo regulation behavior, but it also jeopardizes the health of the population in the long run. What is often overlooked is that this is not only an issue threatening these animals; current practices also reduce the economic sustainability of the in dustry. A decline in the very species responsible for attracting tourists is bound to impact local development. Successful whale shark tourism in SAMPA needs to protect wildlife and their habi tats while also balancing its social and econom ic values—an issue that is not only present in South Ari Atoll but also across the Maldives and the world.

“

Moving away from the old narratives of how sharks injure humans, we want to highlight how humans injure sharks and shine a light on the complexity of human-shark relationships in Fuvahmulah.

Since the inception of the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme to study whale sharks in South Ari Atoll, reports of identified individuals have led to the expansion of data collection to other atolls. While in most of these cases the sighted whale sharks are resident juvenile males, in the waters of Fuvahmulah, a small remote island in the deep south of the Maldives large female whale sharks have been sighted. A significant finding, as encounters with females globally are rare and only recorded in a handful of places, such as the Galapagos Islands and St. Helena. The most recent comprehensive assessment of extinction risk for all 31 oceanic species of sharks and rays has determined a decline in their global abundance by 71%, result ing from an 18-fold increase in relative fishing pressure since the 1970s. Amidst these statis tics, the Indian Ocean stands out as the epicen ter of megafauna loss, and in the middle of it is Fuvahmulah, a beacon of hope for the conser vation of our world’s apex predators. It is known

as “Shark Island” among the locals. Located in the deep waters of the equatorial channel, the island not only witnesses the presence of whale sharks but is also a vital pathway for the migration of endangered ocean ic manta rays and schooling hammerhead sharks, has a cleaning station frequented by endangered pelagic thresher sharks, and is home to a resident population of over 200 tiger sharks—the largest population of tiger sharks in the world that we know of to date.

Sharks have thrived in the waters of the island after the national ban on shark fishing ten years ago. But despite this positive development, human impacts continue to negatively affect the species through increasing pressure from rapid ly expanding and unregulated dive tourism, con flict with tuna fishermen, and incidental bycatch

The question is not how sharks hurt humans but how humans hurt sharks. A boat propeller injured this whale shark.

in artisanal fisheries. Baseline data derived from photos taken by our team members over nine months suggests that about 30% of the sharks have suffered anthropogenic injuries, with many of them being named “Half-fin,” “Joker,” or “Pi rate” by local dive centers, names reflective of the amputations, dislocated jaws, and cuts they have sustained. Several individuals are estimat ed to be pregnant, and together with the injured individuals seem to display strong site fidelity, according to observations from local dive cen ters with regular resightings of the same shark over the last two years. This suggests that Fuvahmulah might act as a “rehabilitation sta tion” or “hospital” for weaker and energetically compromised sharks. Together with some of Fuvahmulah’s most passionate shark conser vationists, I had the opportunity to meet with with the mayor of the island and highlight the importance of Fuvahmulah for the conservation of sharks globally. All signs pointed to the is land being a globally significant shark hotspot with an uncertain future, yet aside from photo IDs collected by one dive center and individual research projects conducted by visiting marine

biologists, little comprehensive research effort has been focused on the sharks in this tiny speck of land on the equatorial channel. To fill this critical research gap, we decided to estab lish the Miyaru Programme—Fuvahmulah Shark Project. “Miyaru” means “shark” in Dhivehi. Our name not only represents our dedication to the research and conservation of the understudied shark populations of the Maldives but also our firm commitment to collaborative, transparent, and inclusive research that is reflective of our values. We strive to become a research team that consists of 3/4 Maldivian and 1/4 international scientists to ensure sustainability and capacity-building on the ground.

Working in partnership with the island council and local community groups, we now seek to conduct the first comprehensive and interdisci plinary studies of sharks in Fuvahmulah through monitoring of tourism pressure and advanced classification of anthropogenic injuries. Our collaborators include researchers from around the world, including NatGeo Explorer

The

The

Maldivians call Fuvahmulah “Shark Island.” A local freedives with a tiger shark.

harbor on Fuvahmulah, one of the most southern islands in the Maldivian archipelago.

PHOTO JONO ALLEN

Maldivians call Fuvahmulah “Shark Island.” A local freedives with a tiger shark.

harbor on Fuvahmulah, one of the most southern islands in the Maldivian archipelago.

PHOTO JONO ALLEN

and PecLab FIU Director Dr. Yannis Papasta matiou, who has over 26 years of experience studying our world’s apex predators. Once we have gathered enough funding, we are seeking to employ novel technologies and use touchless ultrasound devices underwater to confirm preg nancies. Globally, there are still large gaps in our knowledge of tiger shark reproduction and the presence of several pregnant sharks could indicate that mating grounds could be near. Most importantly, our objective is to monitor the health and residency behavior of these beautiful predators and generate knowledge that will feed into the island’s shark conservation and man agement plan, serving both local livelihoods and wildlife.

Our approach is multidimensional and will not only bring together science and conservation but also storytelling underwater. We believe in the power of science, communication and trans parency. Our research processes, outcomes, and the stories of the people we work with will be captured by professional underwater photogra phers and videographers to reach more people, share new shark stories, and make an impact on the conservation of sharks locally as well as internationally. Moving away from the old narra tives of how sharks injure humans, we want to

highlight how humans injure sharks and shine a light on the complexity of human-shark rela tionships in Fuvahmulah. The first phase of our work will be dedicated to tiger sharks; however, the deeper waters of the island offer encounters with rare species such as pelagic threshers— one of the most elusive oceanic shark species. For phase two, our goal will be to put together a highly qualified technical dive team to descend beyond recreational limits and gather data in the deep. Rebreathers will be a critical tool for this mission, as threshers are shy and quickly get scared away by divers’ bubbles. GUE Funda mentals training—which has never been done in the Maldives—will allow our team to refine the core skills required to conduct these challenging dives. As divers, we have access to a world so few people get to experience, and as a research team, we are incredibly privileged to spend so much time in the presence of our ocean’s giants. That access comes with responsibility. A new and mostly unexplored world of sharks awaits in the deep reefs of Fuvahmulah, and with it the discovery of new knowledge that could help us to protect what might be the last shark sanctu ary of the Indian Ocean.

For information on the projects, visit www.fuvahmulahsharks.org and www.miyaru.org

Arzucan Askin

Arzucan Askin is a marine scientist, technical diver, Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and National Geographic Explorer. Her scientific work at the intersection of oceans and society has taken her across the globe, from the monitoring of coral reef health in the waters of Hong Kong, the tracking of illegal fishing activities in Malaysia, ghost gear removal from wrecks in Turkey, all the way to acoustic monitoring of blue whales in uncharted Arctic waters. Awarded the 2021 European Rolex Scholarship

for a year of advanced dive training and marine science in the field, she spent the last year travelling the world to learn from leading researchers and dive professionals in the underwater world. As co-founder of the Miyaru Programme, she currently works on setting up shark science and storytelling projects that illuminate the intersection of human societies and sharks. She also hosts specialized shark dive expeditions together with underwater photographer Jono Allen. www.arzucan-askin.com

Long decompression stops are known to be boring at best, but they can also include varying degrees of discomfort or even dangerous conditions; for example, hypothermia caused by a leaking drysuit. The possibility of finishing a long and deep cave dive in a dry habitat is appealing. However, whether to install one is a risk-versus-benefits decision. After spending a fair bit of time on decompression stops in water and in habitats, Kirill Egorov shares his habitat experiences.

As long as humans have exist ed, they have ventured under water. Some of their reasons had to do with gathering food, looking for treasures, and/or conducting military activities.

From the beginning, these early divers tried to overcome the limitations caused by breath-hold diving.

Long before the invention of technologies, such as surface-supplied equipment, rebreath ers, and open-circuit diving gear, the inverted diving bell was developed. This chamber can be suspended in the water and filled with air. It is open at the bottom, allowing divers to get in and out while conducting underwater operations.

Probably the earliest description belongs to Aristotle, who wrote the following in the 4th century BC:

“Diving bells enable the divers to respire equally well by letting down a cauldron, for this does not fill with water but retains the air, for it is forced straight down into the water.”

From Aristotle’s time until today, historical references to the use of different types of diving bells can be found. Such devices have been used for recovering sunken treasures from the Spanish ships off the coast of Florida and Santo Domingo, for salvaging the wrecks of Mary Rose and Vasa, and many other underwater adventures.

This habitat is equipped with a scrubber unit, an essential feature that allows the decompressing divers to get off the mouthpieces.

“

Cave divers use habitats to make long decompression stops more comfortable and potentially safer. They allow us to get rid of some or all diving equipment, get out of the water, warm up and relax, talk, eat, and drink.

The simple, original design has undergone some significant improvements over time. Dive operations began to replenish breathing gas (first using barrels to transport it, then later bellows and pumps), different combinations of ropes and weights were deployed to change depth while sit ting in the bell, and ropes and colored flags were used to communicate with the surface crew.

These concepts are still in use today and are actively utilized by commercial and military div ers.

The scientific diving community not only found a good use for diving bells but also somewhat expanded the concept by developing underwater habitats—submerged structures in which people can live for extended periods and carry out most of the basic human functions during a 24-hour day, such as working, resting, eating, attending to personal hygiene, and sleeping.

Adventurers and explorers such as Jacques Cousteau and Edwin Albert Link contributed much to underwater habitat research by setting up multi-day underwater operations in order to study not only the ocean, but also how the human body copes with such conditions.

How does all this apply to us? Technical divers, especially cave divers, tend to “borrow” various technologies from military and commercial diving communities to put them to extremely good use in their field. Rebreathers and DPVs are good examples of this.

Cave divers use habitats to make long decom pression stops more comfortable and potential ly safer. They allow us to get rid of some or all diving equipment, get out of the water (at least partially), warm up and relax, talk, eat, and drink. Some nicer ones will even allow the use of a tablet or an MP3 player. Divers can even read a book to help with the boredom of long decom pressions.

A soft-shell habitat is relatively easy to install and fits in many environments.

At the same time, some potential risks are present when a team utilizes a habitat. For in stance, during installation, visibility can be bad. Also, if the operation is not planned correctly, divers can end up blocked from the cave exit. Habitats float and are tough to secure due to the significant volume of gas. Anchors, ice screws,

the cave ceiling, metal frames, or a combina tion of all those factors create a significant challenge. Also, as with any gas-filled volume, a leak can lead to loss of breathing gas and/ or even the collapse of the soft-shell habitat. Care must be taken to avoid CO2 build-up in the habitat, and div ers are advised to be cautious when going off their rebreather loops or open-circuit regulators. Lastly, bacteria or mold can accumulate if the habitat is used for several seasons or years. Granted, all of these are manageable risks, but they must be discussed whenever a team considers using a habitat for their project.

Let’s say that our project team has decided to use a habitat. Now we have to choose where and how to install it, as well as what type of hab itat will best fit our needs. We must start by decid ing if it will be a short- or a long-time application and how far into a cave we will have to place it to meet our decompression needs. It is important not to disturb the aesthetic of the cave for other div ers. We will also need to decide how to secure it. Is it going to be anchored to the floor, screwed into the walls, or pushed against the ceiling? That is where we will have to look at different design options.

Containers used for beer or wine making can be modified to serve as hard-shell habitats.

Containers used for beer or wine making can be modified to serve as hard-shell habitats.

“The simple start is to choose between hard and soft-shell options.

Installing a habitat requires planning and teamwork. Also, the habitat must be tested before using it for sharp deco dives.

Hardshell habitats are produced in different sizes and, as a result, they provide a very differ ent level of comfort and complexity of installation. The simplest ones are nothing but a plastic tub, big enough for a diver to get their head (and maybe shoulders) out of the water to get some rest from the mouthpiece, clear the mask, drink and eat something and chat about the dive. But another choice is to use a large container nor mally used to transport water or juices for wine making and brewing. These allow a diver to get out of the water. After the equipment is removed and clipped outside, divers can sit and have a very comfortable deco. These habitats are sta ble and very cozy, and they allow for setting up a number of extras, such as attachment points for scrubbers or food tubes. They can stay in ser vice for years but will need periodic checks and scrubbing. The problem with large hard-shell habitats is that they can be used only in a rather large cave with a big entrance, easy water ac cess, and a stable flat ceiling at a specific depth.

Soft-shell habitats are often made-to-order neo prene or rubber bags resembling an oversized lift bag. The shoft-shell habitat will have to be either stretched over a metal frame, pushed into

the frame, or pushed into the ceiling and secured to the wall and the floor using anchors and screws.

These habitats are much smaller and easier to transport, both on land and in the water. They are some what easier to install, can be set up in several environments (po tentially even in open water), and may be set up to change depth as a team is going through their decompression inside.

Unfortunately, the costs for soft habitats are pretty high, as they have to be made to order. They tend to develop minor leaks over time as they are pushed into walls and ceilings. This is especially the case if they have a dump valve installed. They also require modifications of the cave, such as drilling or nailing, a practice that is not the most environmentally friendly approach.

Whatever option is chosen, it is essential to work as a team during all preparations—to set up and fill the habitat—as well as to ensure that everyone is safe and knows what is happening. It is also crucial to do a few test dives to ensure everything works as intended before trusting the habitat to support dives that require substantial decompression.

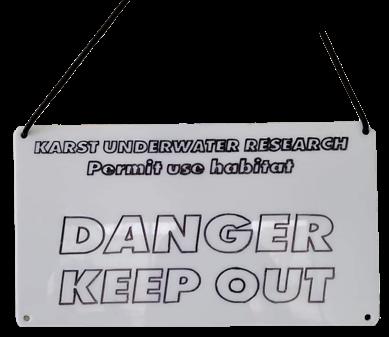

Once the habitat is in place, what’s next? Over the last ten years, several cave diving teams around the globe have not only embraced the use of habitats but have also enhanced the habitat’s safety and comfort to a whole new level. Karst Underwater Explorers (KUR) is an ex ample. The team provided photos for this article and, as a member, I would like to highlight a few cool items.

Probably the number one cool toy we have is a habitat scrubber. As mentioned above, a simple diving bell without surface-supplied gas and recirculation will slowly accumulate CO2. This will eventually make the gas in the habitat unbreathable, causing the divers to be forced to breathe from a regulator or rebreather during

The habitats usually do not provide much space, but they are a much better option than decompressing in water.

The scrubber unit is made out of an old CCR handset and a stack of sofnolime. It regulates both the CO2 and the pO2 in the habitat.

the stay in the habitat. This is tiring, boring, and prevents conversation. Staying on the breathing apparatus defies the whole purpose of having a habitat. To mitigate this problem, the KUR team designed a simple scrubber unit that uses a fan to circulate gas through a stack of sofnolime. Three cells measure the oxygen content, and an old rebreather handset is used to monitor the oxygen partial pressure (pO2) in the habitat. So, not only can we get rid of CO2, but we can also maintain a pO2 of our choosing by adding oxy gen into the habitat.

Item number two on the list of cool addi tions is a habitat phone and in-habitat internet connection. During long dives, from setting up, cleaning up after the dive, bringing in food and drinks, managing any emergencies, and engag ing EMS if needed, we are totally in the hands of the support team. Therefore, it is nice to be able to communicate with them without needing a support diver to get in the water to make sure we have everything we need and that all is well. Finally, as already mentioned, we can bring down an iPad and a set of Bluetooth speakers in a waterproof bag, allowing us to, relax, eat something nice, discuss the dive, call our sup port team, and watch a movie. That makes for a perfect end to a great dive.

Kirill Egorov graduated from Moscow State Pedagogical University as a teacher of Physics in 1999 and attended a course of archaeology at Moscow State University. These two specialties allowed him to participate in multiple scientific research programs. After his first try-dive in 2000, Kirill was totally amazed with the underwater world, and made it his hobby first and profession later. He became a PADI recreational

The habitat phone and internet connection facilitate effective communication with the surface support team.

and technical instructor in 2003-2004 and joined GUE in 2005. Since that moment he has concentrated on two main passions: diving and teaching diving. Kirill is currently teaching for GUE at Cave 2, Tech 2, and CCR levels and working on GUE training materials. He resides in High Springs, Florida, which allows him to cave dive as much as possible.

Kirill Egorov

Kirill Egorov

s someone who loves being in the water, and preferably under the surface, Julian’s inter est is creating pictures of this fascinating aspect of the world. Since most people are not able to visit this portion of the planet, he wants to share all the beauty and diversity that exists.

Telling a story within these pictures is key, as it then elicits emotions in the viewer: Showing a diver exploring known or unknown territory, capturing the action of a fast-paced underwater hockey game, models or athletes demonstrat ing the calmness and easiness of breath-hold

Adiving. His passion for diving started as a child when he first learned snorkeling in his local dive club in northern Germany. He then started discovering the underwater world in many ways, including freediving, scuba diving, and rebreath er diving in caves and on wrecks and reefs, as well as playing underwater hockey.

Fascinated by the underwater world of the Baltic Sea, he was only able to collect memo ries and mental images in the first years. His photography journey started with old fashioned film equipment in the late 1990s, using a make shift darkroom in his parents’ bathroom for developing black and white pictures. In the early 2000s, he was finally able to take his passion for photography from above the surface to below, capturing his first real pictures underwater.

www.julian-muehlenhaus.com

LOCATION Giannis D, Abu Nuhas, Egypt

CAMERA Canon EOS 5D Mark II

LENS Sigma 15mm fisheye

EXPOSURE 1/40s, f5.6, ISO 200

FLASH None

COMMENTS Three divers during the descent to the wreck.

TITLE Halls of fame

LOCATION Slate mine Nuttlar, Germany

CAMERA Canon EOS 5D Mark II

LENS Sigma 15mm fisheye

EXPOSURE 1/40s, f6.3, ISO 1600

FLASH 2 x Inon Z330, 2 x Nikonos SB105

COMMENTS Two divers exploring one of the big halls in the flooded slate mine.

TITLE Take off LOCATION Sinai, Egypt

CAMERA Sony A7R III

LENS Sigma 15mm fisheye

EXPOSURE 1/125, f13, ISO 160

FLASH 2 x Inon Z330

COMMENTS Three divers watching a huge stingray taking off from the sand.

TITLE Attack

LOCATION Swimming pool Elmshorn, Germany

CAMERA Sony A7R III

LENS Sony FE 16-35mm f4

EXPOSURE 1/10s, f10, ISO 1250

FLASH 4 x Inon Z330

COMMENT The UW rugby team Schlickteufel on the way to the strike.

TITLE The Explorer

LOCATION Chrisoula K, Abu Nuhas, Egypt

CAMERA Sony A7R III LENS Sigma 15mm fisheye for Canon EXPOSURE 1/60, f8, ISO 1000

FLASH 4 x Inon Z330 (two on camera, two placed on the tanks of the divers)

COMMENTS Due to the percolation in the engine room of the wreck, it was necessary to work efficiently and fast.

TITLE Not a school of sharks

LOCATION Hurghada, Egypt

CAMERA Sony A7R III LENS Sigma 15mm fisheye EXPOSURE 1/250, f13 ISO 400 FLASH None

COMMENT I wanted to imitate images of large schools of sharks.

In addition to the standard base equipment necessary for all dives, GUE divers often carry extra equipment that can be situation dependent. One should always evaluate the utility of additional equipment since it is easy to continue accumulating a variety of paraphernalia that unnecessarily weighs down a diver while adding additional effort and stress.

In addition to the standard base equip ment necessary for all dives, GUE divers often carry extra equipment that can be situation dependent. One should always evaluate the utility of additional equipment since it is easy to continue accumulating a variety of paraphernalia that unnecessarily weighs down a diver while adding additional effort and stress.

Extra equipment that has passed the needed/ not needed test and has been deemed useful for the effectiveness or the safety of the dive is transported in a manner that satisfies two crite ria: 1) The equipment must be out of the way, so it does not compromise the diver’s streamlined profile, cause entanglement problems, damage the equipment, or impact environmental sur roundings, and 2) The equipment must be easily accessible during the dive. In most cases, the

best way to accomplish these goals is to store extra equipment in pockets positioned on the side of a diver’s thigh, almost on the hips. Even if the thigh-mounted pockets protrude a bit, they do not significantly add to the diver’s drag, as they are predominantly hidden behind the shoul ders when the diver is in a flat trim position.

The compass is a valuable equipment item. Many divers accept that a compass is part of the configuration but then fail to use it. However, the compass provides excellent accuracy for di rectional awareness when used properly. Learn, with practice, how to use the compass by incor porating it into a normal diving regimen.

The compass should be rugged and easy to read. It should have a luminous dial, an easily referenced lubber line, large cardinal points, and a

THIS ARTICLE SERIES IS BASED ON THE GUE PUBLICATION DRESS FOR SUCCESS BY DAN MACKAY. TEXTMost digital dive instruments feature a digital compass, but many divers prefer traditional magnetic units.

The small SMB and spool are compact enough to carry in a pocket.

directional indicator. The compass must be liquid filled, and the needle pivot should allow for tilting of the compass at reasonable angles without causing the needle to stick. The compass should also have a port on the side for horizontal view ing and be worn on the left wrist with the view port toward the diver. The compass can be digital and integrated in a dive computer but, in that case, it can be difficult to read.

Marking devices come in two types: open circuit (OC) and closed circuit (CC). An open-circuit bag has a physical opening in the bottom of the bag that requires purging a regulator into it to fill the bag. A closed-circuit bag has a valve that the diver either blows up orally or attaches to a low-pressure accessory hose for inflation. Extreme care must be taken to ensure that the valve on the SMB is one that does not lock to the hose, which could cause a rapid uncontrolled ascent to the surface if the diver is unable to detach the hose.

At one time, the closed-circuit design was preferable because it was possible for the open-circuit bag to reach the surface, fall over, and “dump” its air, rendering it ineffective as a marking device. Newer designs have a trap ping mechanism that stops this from occurring. A diver considering an OC SMB should be sure that it has an anti-dumping design.

sages to the surface crew. In an emergency, an SMB may be used as a flotation device. For diving in the ocean, divers sometimes carry two SMBs, a large one and a smaller one. The larger SMB is either stowed in the storage pack on the back plate or secured to the bottom of the back plate using two loops of shock cord. The small er SMB, with a spool pre-attached, is typically stored in a pocket.

Spools can serve multiple purposes but are primarily used to deploy SMBs and to provide directional guidance in overhead and low-visibili ty environments.

In cave diving and advanced wreck pene tration they can offer directional control when covering short distances, such as completing jumps and gaps, or they can be used as an emer gency safety device for lost line/buddy drills. See page 60 for more infor mation about the use of spools in cave diving.

The SMB provides surface support with a visual reference to the location of a diver and also gives the diver a point of reference during decompression stops. An SMB enhances safety by providing location information to surface support and is especially useful in high traffic areas.

Spools should be sim ple and without locking mechanisms or handles. The central hole should be large enough to allow handling with thick wet or dry gloves.

The SMB provides surface support with a visual reference to the location of a diver and also gives the diver a point of reference during decompression stops. An SMB enhances safe ty by providing location information to surface support and is especially useful in high traffic areas. It can also be used to float expended stages/decompression bottles so they can be located and recovered, and/or to send up mes

Many divers carry at least two spools. A 25 m/75 ft spool with a double-ender is carried as a safety spool in the right-hand pocket and should only be deployed in cases of emergency. The middle of a silt-out or a lost buddy situation is not the time to discover one’s safety spool is not where it is supposed to be or that it is tan gled. That is why it is imperative that the emer gency spool is simple and tangle-free. When this device is needed, it is definitely needed.

The second spool is typically 30 m/100 ft and is attached to the secondary lift device, the 1 m/3 ft SMB, and stowed in the right pocket. A third spool, also with 30 m/100 ft of line, may be carried in the right pocket for use with the

“

must be as simple as possible without unnecessary tension mechanisms or ratchets.

primary lift device or for general-purpose use, if required. Spools larger than 30 m/100 ft tend to be cumbersome and should only be carried for special purposes. If a dive requires a spool larger than this, consideration should be given to carrying a primary reel. Larger spools such as the 45 m/150 ft should be restricted to over head environment use.

In overhead or low visibility environments, the primary reel provides a navigational guideline back to the daylight zone for exiting.

The reel must be of a simple design without possible line traps between the handle and spool. No ratchets, spring-loaded tension mech anisms, or retaining devices are needed.

The capacity should be at least 120 m/400 ft. The primary reel can be carried attached to the diver on the butt D-ring of the crotch strap.

Take care when selecting a primary reel, avoiding gimmicky designs that are easily tangled. Dealing with a troublesome reel can be

See page 60 for more information about the use of spools and reels in cave diving.

frustrating at depth when bottom time is ticking away. A poorly designed reel can also cause a significant entanglement hazard when line unexpectedly pays off the reel and trails behind, unbeknownst to the diver. When attaching the double-ended bolt snap to the reel, ensure that it is snapped down through the top of the at tachment point of the reel. This will ensure that the reel cannot automatically detach itself from the bolt snap, which happens on an annoyingly regular basis if the bolt snap is attached incor rectly.

Bolt snaps and double-enders provide a meth od to attach equipment to the harness or to store ancillary equipment in pockets. Choosing the right size for the job can vastly improve ease of attaching or detaching equipment as required. All stainless steel construction is important. While brass and nickel-plated de vices are less expensive, they rarely include a stainless-steel gate spring. Springs that are

Select quality stainless steel bolt snaps and doubleenders to avoid jamming caused by corrosion.

not stainless steel tend to rust and jam quick ly, even in freshwater. It is wise to incur the extra expense and effort to insist on stainless steel bolt snaps and double-enders, as these devices are frequently being manipulated by feel alone. This becomes a nearly impossible task when a rusted gate jams and impinges on diver safety, especially when expending an inordinate amount of effort while conducting time-sensitive maneuvers, such as manipulat ing stage bottles at depth.

Select the correct device for the job and avoid choosing a bolt snap that is too big. In general, the following sizes are used for the tasks indicated:

• Securing the long hose to the harness –1/2” bolt snap

• Securing backup lights to the harness –1/2” bolt snap

• Securing the SPG to the left-hip D-ring –3/4” bolt snap

• Securing stage bottles – 3/4” or 1” bolt snaps

Double-enders are the jack-of-all-trades and are used for a variety of tasks. It is appropriate to raise another training caveat at this time: Avoid the urge to think that bigger is better. Use the appropriately sized attachment device for

the task indicated. What seems like a difficult job to attach and remove when first learning a skill becomes easier when motor skill and muscle memory improve through practice. As always, stick with the mantra of never substituting equipment for skill.

Wetnotes provide a method of communication while underwater and data collection.

When hand or light signals are inadequate, wetnotes can provide an unambiguous method of communicating clearly. As well, they provide a very convenient place to keep deco sched ules or any other information that a diver may require to have at their disposal on a perma nent basis. They are also far more flexible than slates for survey work.

The wetnotes binder can also store tools, pencils, small spare parts, and even survey compasses. The wetnotes chosen should have the erasable, spiral-bound sheets and an exter nal cover that provides a secure storage area for pencils and a survey compass, as well as an elastic closure method and an attachment point for a bolt snap. Wetnotes are stored securely clipped off to a bungee in a pocket when not in use.

TEXT JESPER KJØLLER PHOTOS JESPER KJØLLER & DERK REMMERS

TEXT JESPER KJØLLER PHOTOS JESPER KJØLLER & DERK REMMERS

Up to half of the diving time on a typical Tech 1 dive is spent in the water without many references; buoyancy and stability are essential.

PHOTO DERK REMMERS

PHOTO DERK REMMERS

behind your head makes a powerful hissing sound, and you immediately know that you must do something about it. Is the leak coming from the left or the right post? Or maybe from the middle of the manifold?

You are not sure, so you make a quick decision based on your training—you begin to shut down the right-post valve while signaling to your team with your primary light on your left hand. You breathe your primary regulator down, clip it to your right chest D-ring, and switch to your backup with the left hand. You pause your breathing for a few seconds while listening for bubbles. Did they stop? Yes! That reveals essen tial information. First, you’re now sure that you chose the correct valve to shut down.

But, since the bubbles stopped, you also know that the problem might be fixable be cause it relates to a first-stage regulator and not the manifold. So far, so good. But now you need help.

You call in the closest teammate and ask for assistance. The diver in front of you takes note of what you are breathing—the necklace bungees on your cheeks reveal that you’ve switched to your backup and that the left post is open and functioning.

Your teammate goes into troubleshooting mode behind your head and out of your field of vision while you orient yourself, make sure the line is nearby, and ensure that the team isn’t drifting away.

Your aide reappears in front of you, taps you on your right shoulder, and indicates with

Wan OK sign to you and the third team member that your right-post regulator is reseated. It is good again, and you can switch back to your primary second stage. You unclip it, purge it to verify that it is breathable, and then you per form a flow check to verify all valves are open. You also check that your deco cylinder valve is closed and pressurized, and, finally, you check your SPG before agreeing with the team to con tinue the dive.

This situation was simulated with a blow gun by the instructor on a GUE Tech 1 dive. During the course, this will occur again and again in dif ferent variations of left post, right post, fixable or non-fixable regulator, and manifold failures. The intent is to move the valve drill from the Fundamentals course into a more realistic sce nario and teach the Tech 1 trainee to deal with more advanced and realistic failure scenarios.

One way to differentiate between different levels of diving is to look at the basic prob lem-solving methodology. In recreational diving, it is always an option to abort the dive and go to the surface in the event of a problem. Even if most entry-level dive courses involve safety drills, they do not have to be as robust, as they only need to cover the distance between where the problem occurred and the surface.

Technical diving, however, is different. “Just go up“ is no longer an option. The shortest possible definition of technical diving is a sce nario involving overhead and/or more than one gas deployed during the dive. Having a ceiling over your head—a virtual ceiling in the case of decompression or a physical ceiling in a cave, inside a wreck, or under ice—prevents the diver from applying the recreational problem-solving

“One way to differentiate between different levels of diving is to look at the basic problem-solving methodology.

Before the failure scenarios are practiced in water, they are drilled during extensive dry runs.

method. And, bringing more than one gas on the dive adds complexity and accelerates the pos sibility of breathing the wrong gas at the wrong depth with potentially fatal consequences. Approaching a dive with these factors in mind poses a much higher demand on the diver, the team, the equipment, the training, the prepara tion, and the procedures.

Tech 1 is designed to develop problem-solv ing skills in the participants and to present well-proven and safe templates for normoxic trimix accelerated decompression dives to a maximum depth of 51 m/170 ft with a maxi mum of 30 minutes of decompression.

Historically, the Level 1 courses were developed before the Fundamentals class that later became a prerequisite for Tech 1 and Cave 1. That is why practically all the skills and concepts taught during Fundamentals are scaled directly towards Tech 1 or Cave 1. The Fundamentals class was reverse-engineered by instructors to basically answer the question, “What skills do we want our students to master, at a minimum, before they arrive for the Level 1 training?”

As a Tech 1 instructor, you are privileged. Your students already have a Fundamentals Tech pass. You have excellent raw material to work with, and it is only a matter of propelling the students to a new level of aware ness and providing them with the tools and templates for executing decompression dives. They already know how to shoot an SMB, share gas, and do valve drills, and they should have a decent repertoire of different propulsion meth ods.

switch into an expect-the-unexpected mindset and trust that combining their Fundamentals skills, teamwork, and increased situational awareness will bring the team safely back to the surface.

But they are not left to their own devices. The correct response to different failures is briefed and practiced during dry runs before each of the training dives. It could be argued that the scenarios are slightly unrealistic. I mean, how likely is it that you lose your mask, your prima ry light fails, and you’re forced to shut half the team’s valves on the same dive? But, the aim is to present the team with increasingly complex situations to build the confidence to prioritize the challenges. This is where the “train hard, fight easy” approach enters the picture.

“In the Tech 1 course, the training shifts into a dynamic scenario-based pattern. The students do not know what is going to happen in detail.

Unless they’ve already taken a cave diving class, most Tech 1 students have only limited experience working with reels and lines—so, one of the early dry runs teaches the students the ba sic principles of line work. If you are not careful, the line can create more prob lems than it solves. It is worth remembering that Gremlins and lines have one thing in common: Don’t get them wet! (The other Gremlin rule—do not feed them after midnight—does not really apply to lines.)

But, during Fundamentals, all of these skills were practiced in a static and predictable setting, and they were prepared and briefed by the instructor. No surprises. In the Tech 1 course, the training shifts into a dynamic sce nario-based pattern. The students do not know what is going to happen in detail. They must

Obviously, getting lines wet can’t be avoided, but the Gremlin analogy at least reminds us that lines must be handled with a lot of care under water. While working on the line-laying dry run, instructors present other failures such as lost masks and failed primary lights, and they intro duce principles and necessary communication for rearranging the team on the line.

The decompression cylinder is the key to technical diving. It allows the diver to bring more gas, and it facilitates accelerated decompres sion as the elevated oxygen partial pressure cre ates a more efficient elimination of inert gases.

The line work dry run sets the pace for the entire course. Failures are introduced and the trainees learn how to rearrange the team to box in the weakest link.

“The focus here is developing decisionmaking, communication, and necessary situational awareness skills that make the team an efficient, functional, and safe unit.

During the experience dives, the instructor might still create a few challenges, but the main focus is executing actual decompression dives in real environments.

Deco cylinders are a new piece of equipment for a Tech 1 student, and they are introduced in a similar way as a weapon to a new recruit. During boot camp, no shots are fired, but the soldiers get accustomed to carrying the weapon everywhere and develop constant awareness of the firearm’s status. During the first couple of dives, the deco cylinder is carried but not used— the students get a chance to perform skills like S-drills and valve drills while getting used to carrying the deco cylinder.

Ascent training is an integral part of the Tech 1 course. Ascents must be executed with precision in buoyancy control, timing, and communication. L

Limited Technical divers, especially wreck divers, spend a lot of time in the water column with little or no reference except for a downline or an SMB. Get ting comfortable and stable in mid-water is an essential skill, which is why the first dive on the course begins where the Fundamentals course left off. Are the candidates able to perform S-drills and valve drills on a line? Do they have their priorities straight? It is more important to

stay close to the line and keep the team to gether than to execute a smooth and fast valve drill. Also, on the first dive, instructors evaluate whether or not the team can perform every fin kick in their repertoire.

The rest of the training dives during the Tech 1 course can be divided into three parts. The first dives are relatively shallow and focus on developing team capacity and problem-solving skills. These dives can be represented by the letter “L,“ but it is lying down like this:

The majority of the time is spent relatively shallow (the long stem of the lying “L”), with less time on the ascent. The students practice line-laying while dealing with basic problems such as lost masks, failing primary lights, and simple regulator failures (often ending in gas-sharing scenarios). The focus here is de veloping decision-making, communication, and necessary situational awareness skills that make the team an efficient, functional, and safe unit.

Instructors also introduce the workflow of a decom pression dive. The key is breaking the dive into smaller segments and preparing for each phase by thinking ahead. The students learn to ask themselves, “Where do I need to be positioned, and how can I best sup port the team and the mission?”

Typically, on the second day, instruc tors introduce the gas switch and add it to the scenarios. During a critical dry run, instructors emphasize the importance of doing clean and smooth gas switches and practice them. Now, the deco cylinder is no longer just baggage.

The second part of the dives (the upright “L”) aims to solidify the ascents, particularly

Getting safe and efficient access to explore depths between 30 m/100 ft and 51 m/170 ft is a considerable increase in exploration range for a diver.

by teaching efficient communication for decompression stops. These dives are done to 30 m/100 ft, but still on nitrox. This gives the student an interesting experience with performing complex problem-solving tasks while under the influence of narcosis and drives home the point that the 30 m/100 ft END mandated by GUE standards makes a lot of sense.

The focus on the first part of the ascent is moving fast—9 m/30 ft per minute—to the first stop. From the first deco stop, the focus switches to precision in timing and stable buoyancy. Most teams struggle with timing and communication during decom pression, so a dry run focusing on ascent protocols usually follows.

Classroom Tech 1’s six academic chapters pick up where Fundamentals ends. After the in troduction chapter that presents GUE, the

“

30 m/100 ft and 51 m/ 170 ft.

course structure, the course limits, and certification requirements, the two chapters that fol low are a direct extension of similar chapters from the Fundamentals course.

Gas Dynamics covers oxygen limits and nar cosis in more detail—the depth and decompres sion gas add complexity and require a deeper understanding of the impact different gases have on the human body at elevated partial pressures.

Gas Planning is more elaborate, as decom pression cylinders are added to the calculations, and the Decompression chapter extends to cover not only decompression theory in depth, but also practical decompression planning with software and subsequent, pragmatic modifica tions to the profiles.

A big “light bulb” moment occurs when the students realize that a 40-minute dive at 39 m/130 ft, a 30-minute dive at 45 m/150 ft and a 20-minute dive at 51 m/170 ft present the same decompression—30 minutes of decompression with 3 minutes on the 21-9 m/70-30 ft stops and 15 minutes at 6 m/20 ft.

Chapters on decompression illness and dive planning round out the written materials. Students demonstrate theoretical mastery with the exam—essentially, a dive planning exercise cover ing decompression schedules and gas planning.

The course culminates in part three: the three experience dives. Getting a chance to plan and execute real decompression dives in open water is where all the hard work pays off.

The students are breathing trimix and switching to 50% decompression gas on the way up. By now, most of the challenges should already have been mastered, so the instructor will not necessarily hit the students with mul tiple failures but let them enjoy the execution of the dives with only minor interference. The instructor will, however, usually orchestrate different ascent modalities to give the student a chance to handle a floating deco situation simulating a lost line in open water. Success fully getting a gas-sharing teammate up to the gas switch depth; drifting and executing a stable, efficient gas switch in the team; and getting a bag to the surface while keeping cool and prioritizing the different tasks are all good measures of success.

Getting safe and efficient access to explore depths between 30 m/100 ft and 51 m/170 ft is a considerable increase in exploration range for a diver.

After the course, newly certified Tech 1 students will be surprised at how easy it is to execute Tech 1 dives. After dealing with an

The Tech 1 rating opens up a new and exciting range of exploration possibilities between

The Tech 1 rating opens up a new and exciting range of exploration possibilities between

increasing number of failures and more com plex scenarios, they will be relieved to discover that most real dives run smoothly with very few glitches. They “trained hard.” Now, they can enjoy the “fight easy” part. The students walk away from the course with a few standardized templates that can be modified to fit variations in depths and dive times.

The biggest revelation is when branching out from the course team and performing with other GUE Tech 1-trained divers. That is where the standardized approach to equipment configu ration, communication, and protocols pays off. The ability to seamlessly integrate with other teams and contribute to projects in a meaning ful way from the first day is a great feeling.

The Technical Diver Level 1 course requires a certification at GUE Fundamentals level with Technical rating requirements and a minimum of 100 experience dives.

Divers embarking on a technical path must be prepared to handle emergencies and execute dives during which they will not be able to make a direct ascent due to decompression obligations.

This type of diving requires an increased level of physical fitness, as there is more equipment to handle, and decompression stress is increased.

Course outcomes include, but are not limited to: cultivating, integrating, and expanding the essential skills required for safe technical diving; identifying and resolving problems; using the double-tank configuration and addressing the potential failure problems associated with doing so; using nitrox for acceleration and general decompression strategies; using helium to minimize narcosis; and applying single decompression stage diving with respect to decompression procedures.

Applicants for a GUE Technical Diver Level 1 program must:

• Be a minimum of 18 years of age.

• Be physically and mentally fit.

• Be a non-smoker and able to swim.

• Obtain a physician’s prior written authorization for use of prescription drugs, except for birth control, or for any medical condition that may pose a risk while diving.

• Have earned a GUE FundamentalsTechnical certification.

• Have a minimum of 100 logged dives beyond entry-level scuba diver.

The Technical Diver Level 1 course is normally conducted over six days. It requires a minimum of seven dives (including three trimix experience dives) and at least 48 hours of instruction, encompassing classroom lectures, land drills, and in-water work .

Maximum deco 30 minutes

Bottom gas 30/30, 21/35, or 18/45 Deco gas 50% or 100%

The Tech 1 course is a prerequisite for the CCR 1 and Tech 2 programs, but both require a minimum of 25 experience dives in the logbook before enrolling.

The most obvious risk in overhead diving is the possibility that divers may be unable to quickly reach the surface in the event of a problem with navigation, equipment, or a team member. This constraint clearly distinguishes overhead diving (e.g., caves) from even the most aggressive types of open water diving. Cave divers minimize the risk of becoming lost by using guidelines that begin at the cave entrance.

This constraint clearly distin guishes overhead diving (e.g., caves) from even the most ag gressive types of open water diving. Cave divers minimize the risk of becoming lost by using guidelines that begin at the cave entrance.

Entering an overhead environment without a continuous guideline to the open water greatly increases the likelihood of a fatality. Continu ous guidelines are critical to cave divers’ ability to safely navigate in restricted passages or in limited visibility.

Because it is so important to maintain a continuous guideline to the exit, divers must

be proficient in the use of guideline reels. And, while working with guidelines requires practice, guideline skills are a valuable asset in any type of overhead diving and are well worth the additional effort required to master them.

The type and number of guideline devices that cave divers will take on a dive will vary depending on their level of training and the part of the cave to be dived. However, all divers entering an overhead should have a minimum of one safety spool per diver and one penetration reel per team. Safety spools must have a minimum of 45 m/150 ft of line and should be used only in the event of an emer

Working

with lines is an essential skill for all cave divers.PHOTO KIRILL EGOROV

gency. Emergency situations that would justify the use of a safety spool include searching for a lost line or dive buddy or repairing a damaged line. Penetration reels typically carry between 45 and 150 m/150 and 500 ft of line, and divers use them to bridge the distance between the en trance to the cave and the permanent guideline (usually about 30 m/100 ft into the cave).

Generally, prior to its use, divers are advised to knot the line on their reel every 3 m/10 ft to help them track the amount of guideline de ployed. Jump and gap spools contain about 15 and 25 m/50 and 75 ft, respectively. Advanced cave divers use these spools to maintain a con tinuous line despite existing gaps (which we’ll discuss in later articles).

It is very important that cave divers become proficient in the use of guideline devices and the subtle techniques of proper guideline de ployment.

When installing a guideline, overhead teams must follow an established protocol.

First, before entering a cave, a team’s lead diver should run the penetration reel and secure its line to a fixed object in the open water. This first tie-off—called a primary tie-off— should mark a position from which a direct ascent to the surface is possible, even during a complete loss of visibility. This guideline should be run close to the bottom to minimize interference with other divers. The projection on which this line is tied should be secure and large enough for a convenient tie-off, but not so large as to waste time or line. Typically, objects that are roughly basketball-sized or smaller provide the most efficient wraps. A primary tie-off includes two loops around the projection for extra security.

After the lead diver secures the primary tie-off and verifies the team’s readiness, they can begin penetrating the cave. Soon after entering the overhead, lead divers should install a second ary tie-off. In low-flow conditions, this is usually done very quickly; however, in high-flow condi tions, teams should move beyond the entrance to a point where the flow may be reduced.

“It is very important that cave divers become proficient in the use of guideline devices and the subtle techniques of proper guideline deployment.

When running a primary reel, keeping it clean and tight is essential for providing enough space for other teams to safely enter and exit the cave.

Primary guidelines are always tied off by lead divers; nonetheless, they are a team responsibility. Other team members can provide assistance by illuminating the way, maintaining line tension, doing line placements, or otherwise helping to maintain team unity. The person nearest the lead diver should provide the most assistance, while other team members should verify the direction of travel and the position of the line, providing help as necessary.

If the line begins to drift or wander into small er areas, the lead diver should place it under a rock or secure it to a projection. Line wandering into smaller areas can create line traps, which may impede a team’s ability to exit. During a loss of visibility, line that has drifted into a line trap is difficult or impossible to follow, greatly increasing the stress of the dive. To prevent line traps in unrestricted passageways, divers should fix the line with placements and tie-offs any time the cave or team changes depth or direction. While tie-offs can be a more secure method of preventing the line from drifting into traps, most divers prefer placements (defined

below) since they are simple to secure and faster to remove. Placements are also easier to follow in bad visibility. Divers may choose to use a tie-off rather than a placement when placements are not secure enough or, due to the terrain, not possible to execute.