13 minute read

Witness to May 18: Dr. Paul Courtright

Witness to May 18:

Dr. Paul Courtright

Advertisement

In 1979, a young Paul Courtright found himself in Korea, working as a Peace Corps volunteer just outside of Gwangju. His work-related travel took him through Gwangju in the early days of the Gwangju Uprising in 1980, later to be known as the Gwangju May 18 Democratization Movement. Eager to witness more of what was unfolding in the city, Paul bicycled back into Gwangju, where he was astonished at what was transpiring before his eyes! Forty years later, when Paul was now Dr. Courtright, he recorded his May 18 experiences in his book, Witnessing Gwangju. In advance of his planned visit to Gwangju, the Gwangju News was fortunate to be able to conduct this interview with Dr. Paul Courtright. — Ed.

Gwangju News (GN): Thank you, Dr. Courtright, for agreeing to do this interview with the Gwangju News. You were a young U.S. Peace Corps volunteer in Korea in the 1979–1981 period, part of one of the last groups in the Peace Corps’ fifteen-year history in this country. Can you tell us what motivated you to join the Peace Corps and come to Korea?

Dr. Courtright: I finished university in the U.S. in 1978, and I knew that I wanted to return overseas. I had spent part of my youth overseas because of my father’s work in Iran, Taiwan, and Australia, and I figured that, ultimately, my career would be outside of the U.S. The Peace Corps seemed to be a natural fit for me. When the Peace Corps offered me Korea and work in leprosy, I said “yes.” I knew nothing about leprosy, but after years of living in Taiwan and studying Chinese, I felt that I wanted to be somewhere in East Asia. I was particularly keen to learn a new language and a new culture, and so, Korea was a perfect choice.

GN: The Peace Corps was the “perfect choice.” So, what type of work did you do during your two years of Peace Corps service? I believe you were stationed in Jeollanamdo for the entirety of you time here.

Dr. Courtright: After my Peace Corps training, I was assigned to Naju Health Center in Jeonnam. During the first few months in Naju, I realized that there was little to do at the health center itself but a lot to do at the two leprosy resettlement villages, which were at opposite ends of the county. It was difficult to get back and forth between them, even on my bike on the back roads. I made the request to live in the largest village, Hohyewon (호혜원), and my friend Tim Warnberg said that he would provide some support to the other village. I moved in November 1979 to Hohyewon, not far from Nampyeong, which is on the outskirts of Gwangju, so I was in and out of Gwangju frequently. Among other things, it had the closest bathhouse. Gwangju became my “second home.” During this time, I spent most Mondays at the Yeosu Aeyang Hospital (여수 애양병원) learning about the eye complications of leprosy.

I lived and worked in Hohyewon until October 1980; my father had passed away, and I returned to the U.S. for a brief period. There was a new group of Peace Corps volunteers coming in, and I asked one of them to move to my village. When I returned to Korea in December, I started a new project: visiting almost all the leprosy resettlement villages in the country with my Korean coworker to examine people for eye diseases. So, during the remainder of 1980 and until the Peace Corps closed down in late 1981, I was “on the road,” traveling throughout Korea, from village to village, focused on providing eye care.

GN: As you were not based in Gwangju, how is it that you got caught up in the Gwangju Uprising in May of 1980? Can you tell us what you witnessed and what you did upon seeing the violence that was taking place?

Dr. Courtright: On May 18, I was hiking near my village. I had no idea about what was happening in Gwangju that day. My village leader told me, when I got back that evening, that “something bad had happened.” The following morning, I was taking two of my patients to the Yeosu Aeyang Hospital for eye surgery, and we changed buses in Gwangju. That was when I first saw what was really going on in Gwangju. I was shocked when I saw a young man being brutally beaten by two soldiers at the bus station. When I came back to Gwangju that evening,

my bus stopped a mile or so before the bus station because of all the debris on the road and the evidence of conflict. I spent that night and the following morning (Tuesday) in Gwangju and saw the uprising starting to emerge. I was back in my village Tuesday night and in Nampyeong on Wednesday. On Thursday, I rode my bike into Gwangju, likely the last person to get into Gwangju on that road. For the next few days, I was in Gwangju unable to get out because of the military blockade.

GN: Luckily, those were some of the calmer days of the uprising. I hope you will be able to share the details in a talk at the Gwangju International Center during your planned trip for later this year. Next is a two-part question: How did your time in Korea in general, and your witnessing the Gwangju May 18 Uprising in particular, impact your life after leaving Korea?

Dr. Courtright: My time in Korea had a huge impact on my life, as I think it does to most foreigners. When the Peace Corps closed in Korea in late 1981, I was not ready to leave. I had grown to love many aspects of the country: the people, the food, the culture, and the countryside – but certainly not the military government of the time. I taught at Seoul International School for the next year, so I did not return to the U.S. until the end of 1982.

Witnessing the events in Gwangju had a significant impact on me, however, at the time, I really did not understand what PTSD [posttraumatic stress disorder] was. The anger, pain, and defiance that people in Gwangju demonstrated was both distressing and inspirational. I wanted to remain in Korea, but I knew my status was fragile: The military government was furious with us because of our work as translators for the foreign reporters and photographers. For a long time afterwards, I tried to push it to the back recesses of my mind – for my own mental state and because I felt there was nothing I could do. Instead, I immersed myself fully in my work.

GN: I think you must have had a fascinating career in public health. Can you highlight some of the places you worked at and the things you have done?

Dr. Courtright: After completing my master’s degree in public health at Johns Hopkins, I moved to San Francisco to work at UCSF [University of California San Francisco]. During this time, I spent a year working in Egypt; my time there was the foundation for my doctorate at UC Berkeley. I have Korea to thank for putting me on my career pathway. Because of my time in Korea, I became particularly interested in the epidemiology of eye diseases, and my entire career has focused on this. After finishing my degree, I got married, and my wife and I moved to Ethiopia for one year, followed by four years in Malawi, and seven years as an associate professor at the University of British Columbia in Canada. I had decided a long time ago that I had limited interest in a U.S.-based academic career. Instead, I was interested in applied epidemiology and public health addressing real-world needs. We returned to Africa in 2001, and my wife and I established the Kilimanjaro Centre for Community Ophthalmology (www.kcco.net) in Moshi, Tanzania. Our training and research facility worked with eye care professionals from throughout Africa. It was challenging but fascinating – we even started partnerships with two Korean organizations to expand their support for the prevention of blindness in Africa. After over 20 years in Africa, I handed over the reins to a new executive director in 2016, and we moved to San Diego. Besides the fascinating experience of working in many countries in Africa, I was also glad that our two sons grew up in Africa. They are both back working in Africa after finishing their degrees.

GN: You have been to so many places and done so many things. And on top of all that, you have recently published a book on 5.18, Witnessing Gwangju. Why did you decide to undertake this book-writing project, and why did you wait until 40 years after the event to do it?

Dr. Courtright: I wanted to write my story about what I experienced in Gwangju, but I waited. Why? First, there were other foreigners, particularly Tim Warnberg, whom I felt were more capable to write about our experiences. Second, I still found it emotionally draining to think back to that time and decided it was better to wait. Third, the rest of my life took over: my work in Africa and elsewhere, and my family. After Tim died, I decided to write – but only when I had the time, when I retired.

▲ Paul Courtright meeting Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (October 2019).

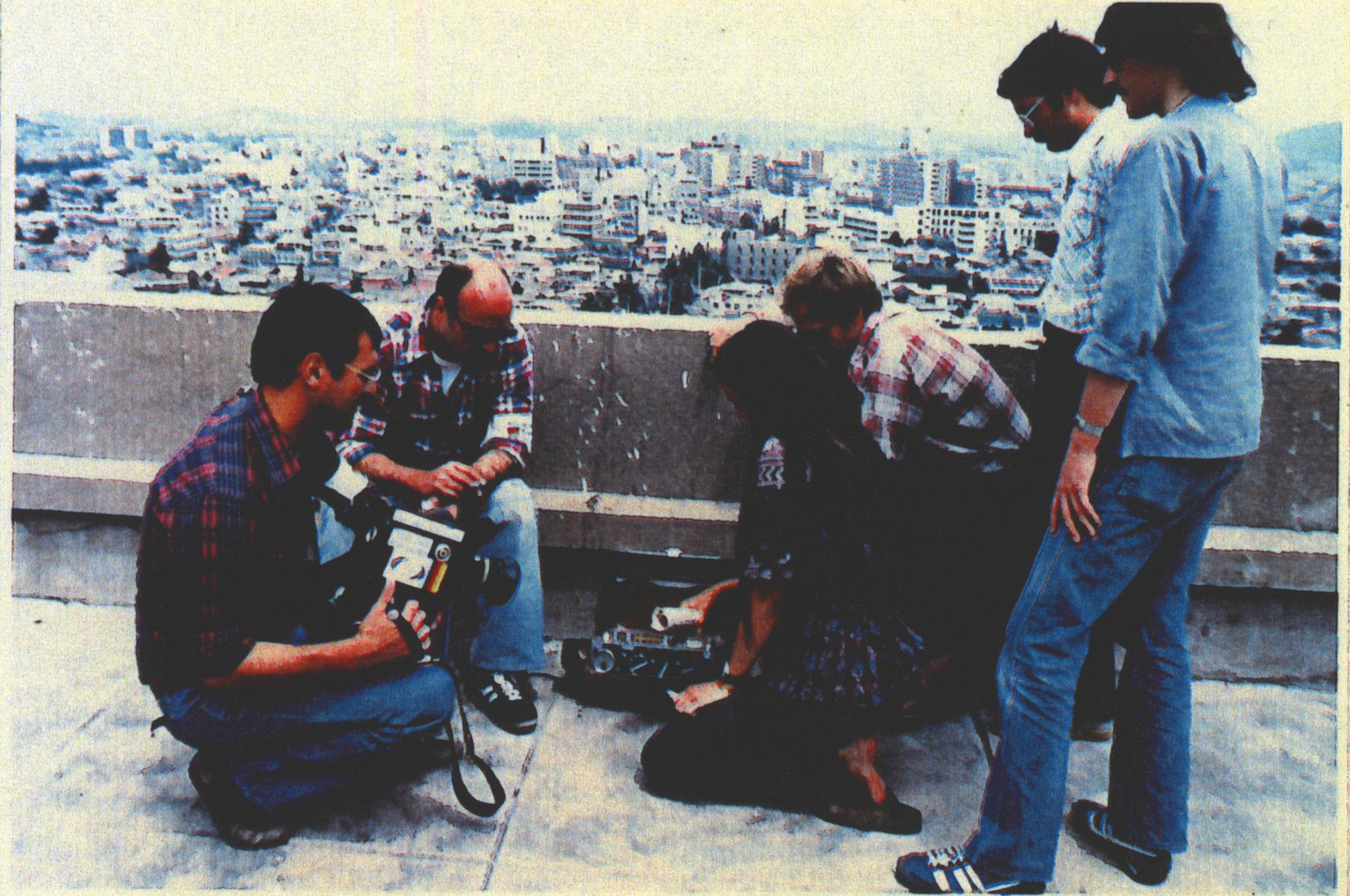

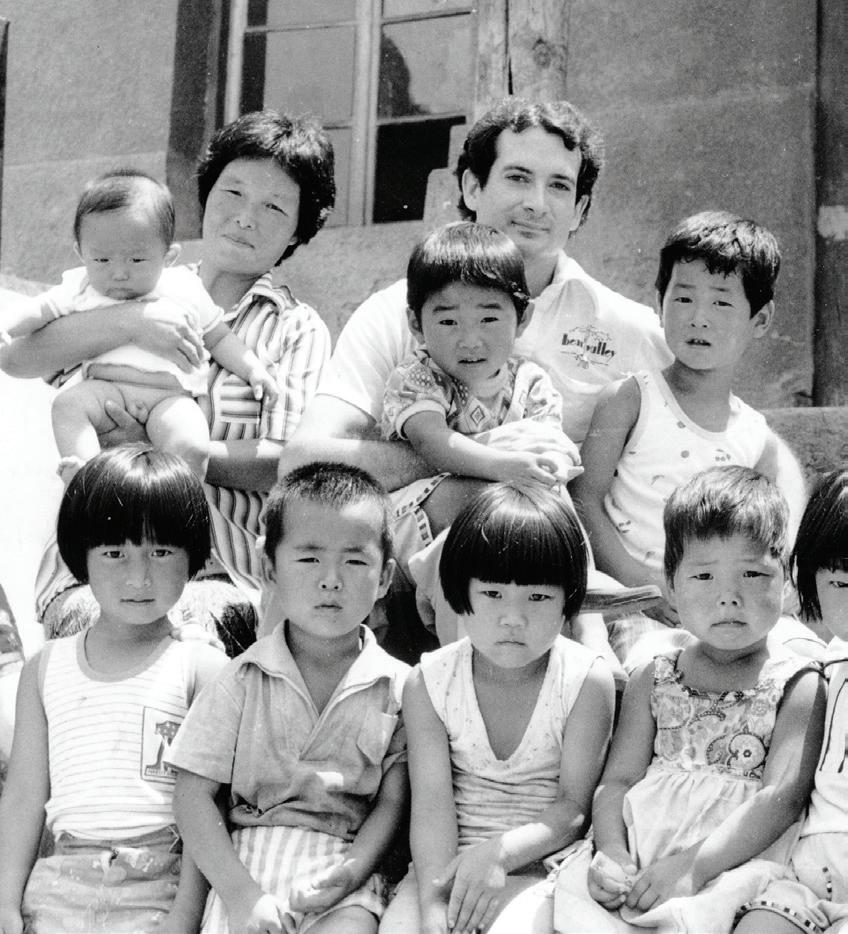

▲ Left: Paul Courtright with fellow Peace Corps volunteer Tim Warnberg at Hohyewon near Naju (1980). Right: Peace Corps volunteer Paul Courtright at a leprosy resettlement village (1979).

the American government responded to it, and how this event impacted people from all walks of life. I thought that it would best be done as a memoir. When I visited Korea in May 2019, it became clear to me, after talking with many of my Korean friends, that Koreans also wanted to hear a foreign perspective of the event. I was told that, as a foreigner, I was considered independent – I was not from Gwangju or other places in the country, and my perspective was not biased toward any point of view. So, I felt that it was also good to have a Korean translation of my book. When I was in Seoul, I was shocked that there were still people who believed the Chun narrative. Incredible!

GN: Yes, I can empathize with the “emotionally draining” part. So, tell us how you went about doing the research required for such a book-length project? I suspect that if I were to reach back and dust off my cranial archives of 5.18 memories, I would be lucky to find enough detail for a short essay.

Dr. Courtright: It would have been impossible for me to write my memoir if I had not kept extensive notes detailing every single day during the uprising. My notes captured not just what I saw, but also how I felt, and what I heard. I had to recreate the dialogue as best as I could. It was important for me to visit Gwangju in 2019 to view a few places, for example, the provincial office building, to remind myself of the interior layout. I wanted to make sure that I captured the sense of the place accurately. I also used some letters I had written to friends at the time, which I had photocopied before posting because I realized that they included a lot of information. Why did I write everything down in May 1980? Having it written down was the only way that I could sleep at night. The events of each day were traumatic, and I found it difficult to sleep unless I had written everything down. That allowed me to be confident that nothing was lost – it was captured on paper and did not have to bang around in my brain all night.

GN: What perspective did you take in your account in Witnessing Gwangju? What do you hope that the reader takes away from the account of 5.18 that you present?

Dr. Courtright: I decided early on that I would only write about what I had observed, what I had heard, and what I had felt during those days, rather than describe the perspectives of others. There are academic articles about the uprising, and it was not necessary for me to repeat what had already been written about specific events. Although I am an academic, my field is not Korean political history, and I did not feel qualified to discuss the implications of the uprising in Korean history or in America’s interaction with Korea. I was only qualified to present what I had experienced, and I hoped that it would give a perspective that may not have been presented in the past. Since my main audience was American, it was also important to present my life in Korea – it helps the readers to imagine themselves in my shoes. I always wondered “what if I…,” so I hope readers consider what they might have done when presented with the same situation. Of course, I also wanted the readers to appreciate my fondness for Korea.

there is a Korean translation of Witnessing out also, “5.18 – Pureun nun-ui jeungin” (5.18 – 푸른 눈의 증인). Is it also enjoying a wide readership?

Dr. Courtright: As you might imagine, many former Korea Peace Corps volunteers are interested in reading Witnessing Gwangju. I have given several talks to Korean studies classes at U.S. and Canadian universities. I hope that people with an interest in modern Korean political history will read my book, but that requires marketing – which is not my strong point. Interestingly, the Korean translation of Witnessing Gwangju has sold many more copies than the English version. There will be a rerelease of the Korean version with additional pictures. Hollym Press has released the English version as an ebook just recently, which should make it more accessible for people in other countries, too.

GN: English, Korean, and now an ebook version – the book appears to be doing extremely well, and gaining in popularity! Well, have you looked into a crystal ball, read tea leaves, or had your saju read lately? Can you tell us what might be in store for Paul Courtright in the future? Dr. Courtright: I tend to avoid looking at crystal balls. That said, I expect that I will continue to support the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem in Africa. Although semi-retired, I work with the Ministries of Health and NGO partners in about 20 countries to help them plan their pathway to elimination – a few, like Malawi, are almost there! I have a team of eleven African technical advisors who now provide on-theground support for these countries instead of me. In San Diego, I am involved in a number of volunteer activities, which I enjoy. Visiting with friends from Korea and eating good banchan with soju or makgeolli will always remain in my future, and a visit to Korea is being planned for later this year.

GN: Ah, soju and makgeolli conjure up memories of times gone by – times that I am sure you have captured in your book. Thank you, Paul, for this interview, and we look forward to your visit to Gwangju this year.

Interviewed by David Shaffer, Gwangju News editor-in-chief. Photographs courtesy of Dr. Paul Courtright.