92 minute read

Crisis in Myanmar

Interview by Melline Galani

For months now, many have witnessed the cruelty and abuses made by Myanmar’s military against its own civilians. Demonstrations and a deadly crackdown have embroiled the nation since February. A single coup brought back full military rule following years of quasi-democracy. Week after week, the armed forces have escalated their attacks on the demonstrators. At the time of this interview, the military had already killed hundreds of people – while having assaulted, detained, and/or tortured thousands of others. Gwangju, as a city of human rights, peace, and democracy, cannot remain silent about this situation. Thus, the Gwangju News conducted an interview with Thinzar Aung, a citizen from Myanmar currently residing in Gwangju. Her opinions are shared in this interview. — Melline Galani

Advertisement

Gwangju News (GN): For our readers, would you first tell us a little about yourself and what brought you from Myanmar to Korea? Thinzar Aung: Yes, of course. I am studying for a PhD in integrative food, bioscience, and biotechnology at Chonnam National University. I am a food inspector for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in Myanmar. I came here to study and learn food science and technology. I hope this education will help to improve my potential to serve my country. Thinzar Aung: There are many political changes that Myanmar has gone through during the past fifty years. But the most dramatic of these can be classified under the names of the generals who held military power in their respective times. In the 1962–1988 period, it was General Ne Win. In 1988–2010, it was General Than Shwe. In 2010–2015, there was General Thein Sein. Most of Myanmar’s past has been under one military regime or another. Even during the last few years, although it was said to be a “democratic” government, it was a fake democracy. From 2010 to 2015, it was mainly a military-backed party, the USDP [Union Solidarity and Development Party], plus the military in power. From 2015 to 2020, the party called

the National League for Democracy, or NLD, which was led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, won the election. Regardless of this, a quarter of the seats in the parliament are reserved for military officers, even though they were not elected, and all the national security forces are directly under the command of General Min Aung Hlaing. So, one can see that it has not been a true democracy.

GN: What have been some of the most significant economic and cultural incidents during this time? Thinzar Aung: As I said, there have been many significant economic and cultural incidents that have taken place during the past 50 years. It is really a long period of history. But if I have to pick the most significant ones nearest to my heart, it would be the 8888 Uprising, and the Saffron Revolution. In the 8888 Uprising, a lot of people died fighting for democracy. You can picture it as being much like the 5.18 Democratic Uprising that happened here in Gwangju; it was similar in many ways. And the 2007 Saffron Revolution is significant in that it was not led by normal civilians but mainly by Buddhist monks. The peaceful Buddhist monks had to go on strike for a revolution because our people were really deep in crises – poor people especially suffered a lot as the prices for fuel and other goods rose about ten-fold. Resultantly, the Buddhist monks who could not stand by and watch such suffering led the revolution and went on strike against the government.

GN: What do you believe has led to the current situation in Myanmar? Thinzar Aung: What has led to the current situation in Myanmar? The answer is simple: “Greed.” It is greed and a hunger for power on the part of Myanmar’s military generals that know no bounds. The military generals have enough wealth and money to last them many lifetimes. So, you may want to ask why they engaged in a coup at all under such favorable conditions. Well, the catalyst that caused such unrest rests upon the fact that the NLD party wanted to change to a true democracy, so the NLD welcomed ethnic minority groups openly in an effort to attain federal unionization. However, the military did not want to give equality to these minority groups, and instead, they wanted to keep their power. They cannot stand the notion of losing any of their power, specifically the 25 percent of the seats in parliament obtained without votes, as I mentioned before. As you may know, they even have huge business networks across all sectors in Myanmar. Nobody can deny that the profits of these businesses are directly related to their unfairly obtained power and influence. So, to continue with the story of how Myanmar became embroiled in its current crisis, the NLD was to be registered as the new government on February 1. But on that day, early in the morning, the military seized power in the country by announcing a state of emergency. You can get the picture. The militarybacked party even accused the legitimately elected party of voting fraud because the military-backed party did not win the elections in the towns, cities, and regions where they thought they had indomitable influence. In reality, the military-backed party itself tried every dirty and cheap trick to win the election, but they could not. So, they arrested the legitimately elected members and staged a coup. This is a fact.

GN: Could you shed some light on how the present protests compare with the 1988 protests? Thinzar Aung: Simple. Mobile phones. In the modern IT age, many people have connections to the world through the internet and social media. But in 1988, the 8888 Uprising did not have such avenues of communication. It was called the 8888 Uprising because it occurred on the eighth of August, 1988, which is shortened to 8/8/88. A lot of people died while they were protecting the Nobel laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from a militaryorchestrated incident that amounted to an attempted assassination of her. Even though many people died in that incident, there were not a lot of documents and photos. The newspaper, the predominant form of media at the time, was under the control of the military. People were kept in the dark about what was happening across the country. Now in the present day, many people are acting as citizen journalists in the present protests in spite of the military trying to cut off the internet and ban social media. On the first day of the coup this year, the military cut off all the mobile phones and telecommunications – both landlines and mobiles. The internet was also taken offline and a total information blackout occurred. People could not call one another. It was like going back to the Stone Age. And then, there was a ban on social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, instituted. Even Wikipedia was banned in Myanmar. Even still, mobile communications are unstable and unreliable. The military has forced the telecom service providers to turn off and on the internet like light switches to disrupt any efforts by the citizens of Myanmar to keep organized amidst the chaos. Then, they do whatever they feel like – without repercussion – to keep people in the dark and cut off from the world. The atrocities they have committed and continue to commit while cutting off the electricity and internet access are unimaginable. We can only pray for the people of Myanmar from far off in these difficult times.

GN: What is the role of the Tatmadaw in Myanmar? How is it that the military has traditionally been so politically powerful? Thinzar Aung: By definition, the role of the Tatmadaw is to defend the people from threats from outside and inside the country. The military has traditionally been very politically powerful since Myanmar’s initial

independence movement and has since become more powerful from 1962 when General Ne Win launched the first coup against U Nu’s government.

GN: What is the present situation with Aung San Suu Kyi, and how much influence is she presently able to exert? Thinzar Aung: Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been arrested again on fabricated charges. She sacrificed her life for the sake of our country, but she never once has mentioned that word “sacrifice.” She always says she just chose the path to democracy. She spent more than 15 years of her life under house arrest. I hope she is well and in good health. We have not heard from her since February 1 when the coup occurred. Even though she is charged with so-called “crimes,” she has not even been allowed to meet with her lawyer. In fact, the court session was done only via an online video call, and her second court hearing this month was canceled due to an internet blackout maliciously caused by the military. Can you believe that they cut off the internet and then said the court session could not take place due to that? About her influence though, I would say it is almost nationwide. Almost everyone loves her. Those who do not have been brainwashed by the military. She has only the love, respect, and trust of the people – not any physical power or force over them. Only the military has the weapons, power, and control under the guise of “national security.”

GN: Do you think the present military takeover will be long-lasting? Thinzar Aung: The present military takeover was absolutely uncalled for. It is illegal and illegitimate. We, the people, voted for the NLD and thought our elected leaders would be in parliament seats and form the government on February 1, as is normal. We thought they would not dare to carry out such a brazen act against democracy itself, because the military’s Senior General MAL said that he would “accept any decisions made by the people of Myanmar.” Now we know his words are not worth a single penny. I do not think this military government will last a long time – at least, not long like the previous one. Yes, the previous coup occurred about sixty years ago, and it lasted about half a decade before returning to a pseudo-democracy. And to think, they even took that cheap imitation of democracy away from us. Now the people, especially the younger people, will not accept military takeover again. They had a small taste of democracy for about five years while the NLD held the majority of seats in the parliament. Despite the fact that a quarter of the seats are reserved for the military, the country truly made considerable progress in the few years that the NLD government held influence.

GN: What has the reaction of the majority of the common people in Myanmar been to the military takeover? Thinzar Aung: At first, a majority of the common people were shocked and very surprised. They could not believe the situation. And then they became enraged because they could not accept the military takeover regardless of the trumped up reasons the military party gave. Their

true, insidious cause was obvious. So, you can see huge crowds protesting in the streets almost everywhere in Myanmar now, despite the overt threat to their lives for doing so. Many good people have died, many good people, like you and me, are still dying – it has even been recorded on video. Some relatives of those in the military, in a flagrant display of their lack of humanity, have given “Haha” reactions to videos of protestors being killed and dying. Can you imagine? You and I, like any other normal human beings, would give our sincere condolences to the fallen angels who have gone back to heaven. Such wanton and reckless taking of human life is never something to laugh at. May their souls rest in peace. It is truly unbelievable that there are people who are more akin ▲ Protest in Gwangju supporting democratization in Myanmar. to demons and pawns of the devils in this a result of the current conflagration, but it will verbally world walking, talking, and using social media as if they tell you “no influence.” China sells guns and weapons not were common people. only to the military but also indiscriminately to ethnic groups as well. So, what the Chinese leaders say with GN: Has the present military takeover had particular their mouths is not the same as their actions. Most of consequences for the already highly mistreated Rohingya Myanmar’s projects producing natural resources, such people? as timber, oil, gas, jade, rubies, rare-earth elements, and Thinzar Aung: I have a lot of compassion not only for the like, are contracted for many years with China-based the Rohingya people but also for the other ethnic groups companies, but we the people did not get a clear version in Myanmar. We have a lot of ethnic groups who are of the contracts involved with this. The local people did still fighting for their rights, such as the Kachin, Kaya, not even get any profit from these projects, probably the Karen, Chin, Mon, Burma, Rakhin, and the Shan. Armed military and former higher-level government officials conflicts are not actually that rare in Myanmar. Only in benefitted. You can see thousands of military-based major cities like Yangon and Mandalay can people of all businesses spanning all sectors in Myanmar as a result ethnic groups live peacefully and equally. In the border of this inequity, and those military families are incredibly regions of Myanmar, there is no guarantee for the safety rich. of any human being, regardless of their ethnic origin or race. While the ongoing military takeover is in progress, GN: News reports tell us that many unarmed protesters there will be no law and order. When even the state have been shot and killed by the military. In your opinion, counselor and president of a country have been arrested how should the world react to this brutal violation of on fabricated charges, do you think there is still hope for human rights?common people like us? Basic human rights like freedom Thinzar Aung: Tragically, the updated death toll is over of speech are not allowed in the country. If you protest 738 as of April 21. At the time of this interview, 2,559 or just speak out, and the military does not like what you citizens of Myanmar are currently being held in detention, say, the punishment is the death penalty, carried out by a and 459 deaths have officially been documented. This is bullet to the head. The lives of all peoples in Myanmar are not accounting for all of the missing bodies that have threatened. No one is safe. been hidden away or totally destroyed by the military in an effort to cover up its atrocities. You can only imagine GN: China has considerable influence in Myanmar. In what the true state of Myanmar is – the official numbers what way do you think China may exert its influence in are not representative of the monstrous acts occurring. the current situation in Myanmar? It is really a war between unarmed civilians and fully Thinzar Aung: China has always said, and continues to armed soldiers – the inequality is enormous, the cruelty say, that it will follow a “no-influence policy” in Myanmar utterly boundless. They not only kill protesters, but they politics – but in reality, it already has a lot of influence in also break into houses and kill people who are residing Myanmar, both political and economic. I do not know in peacefully. The wickedness is appalling. I saw on the news what way China will exert its influence in my country as that even in my hometown of Mandalay, soldiers broke

▲ Thinzar (wearing a white mask) during the support for Myanmar protest in Gwangju.

into a house and shot a seven-year-old girl in the back as she cowered from them, clinging to her father for security he could not provide. That blameless little girl died in her father’s arms. The military’s actions are truly ineffable. The military has done and continues to do more heinous things than you could ever imagine, like desecrating and defiling Mya Kyal Sin’s grave. Not even the dead can rest in peace under this barbaric regime. A sad truth is that some people do not even get to be buried because their bodies are not returned to the families. Now, with the help of civilian journalists and professional journalists, the atrocities carried out by the military, like the raiding of people’s homes or dehumanizing acts like forcing people to walk on all fours like a dog, are being documented, photographed, and recorded.

These noble efforts, though, are just the tip of the iceberg of all the atrocities being committed by the military that continue to go undocumented. There are many more acts of savagery that have not been brought to light as evidence and have failed to reach the international media because of the military’s forced blackout. The social media ban is still in effect at the time of this interview, and the internet blackout is being used by the military as they see fit to prevent the people of Myanmar from contacting the outside world. So, in my opinion, the world should hear the voices of the Myanmar people asking for help and should really help them, as they are in need. Innocent people’s lives are being taken in the foulest ways with reckless abandon. The only voices and words that are able to reach the outside world are just a fraction of those of people who are really in need; only a part of the living nightmare that Myanmar has become is being elucidated. Only those who are well educated in English have fiberinternet in their homes and electricity-powered personal generators – that is, only those who are rich enough to afford all these things and have not been corrupted by the military are able to talk about what is happening. So, I ask you again not to be annoyed by the cries for help, and I implore you to hear their voices. What they are doing is not only for themselves but also for all the many others without voices.

GN: We are deeply thankful to you for having the courage to speak with us. What we have heard is horrible and, as part of the Gwangju community, we will do our best to raise awareness and find ways to help the Myanmar people. Gwangju will always be with the people of Myanmar.

Photographs by Kim Hillel Yunkyoung and courtesy of Myanmar Now.

The Interviewee

Thinzar Aung is a Burmese student who is currently earning a PhD at Chonnam National University. She is from Mandalay, Myanmar, where she worked as a food inspector for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) there. Although her job and potentially her life might be in jeopardy as a result of giving this interview, she is willing to speak out against the military coup and asks for international help for her people. @junothinzar Thinzar

Kim Geun-tae 100 Meters of Art

By Kang Jennis Hyun-suk

Afew years ago, there was a Korean artist who held an exhibition at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. UN ambassadors from many countries attended the exhibition to mark World Disabled People’s Day on December 3.

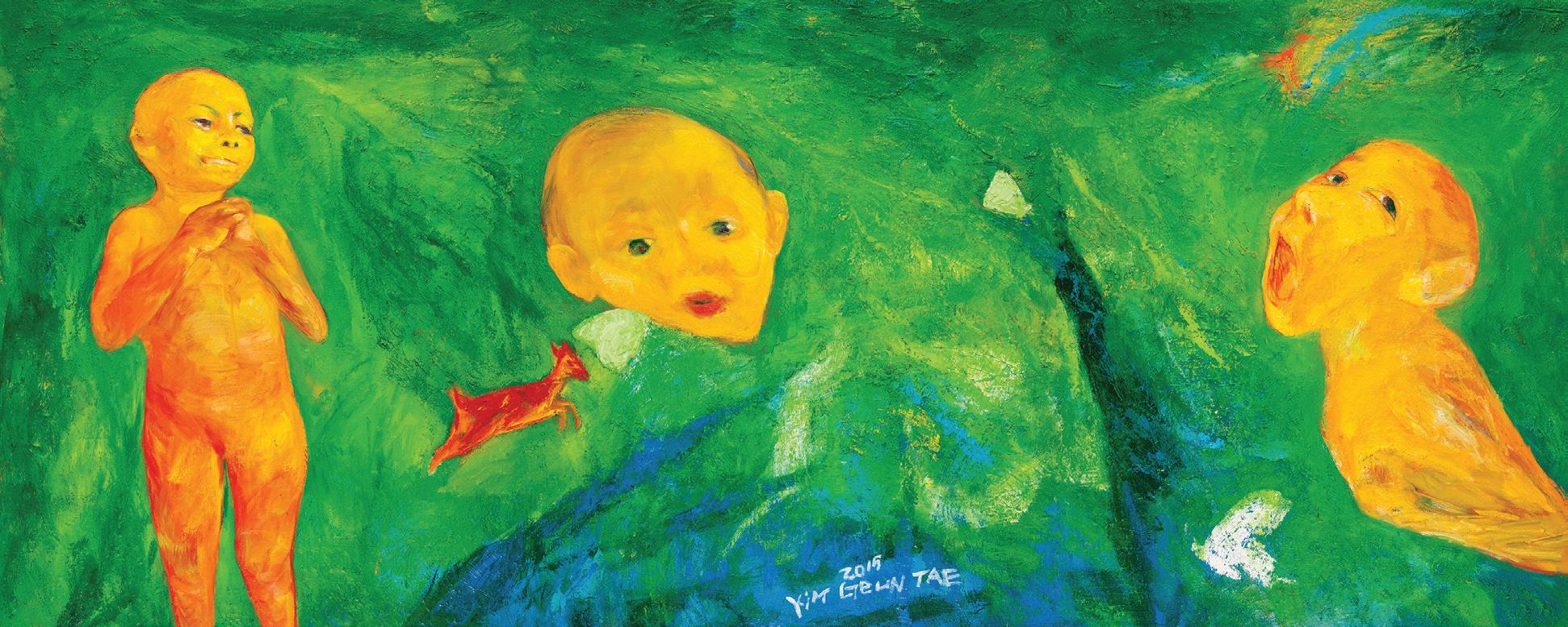

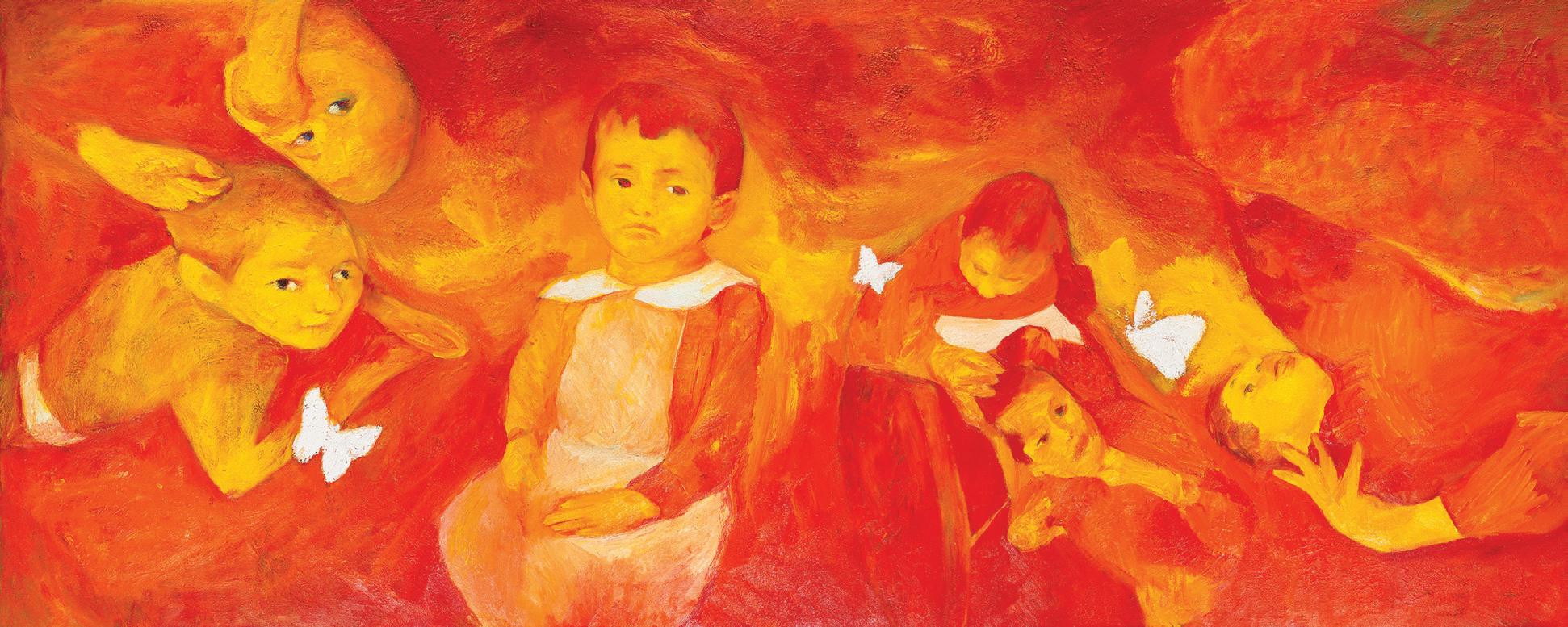

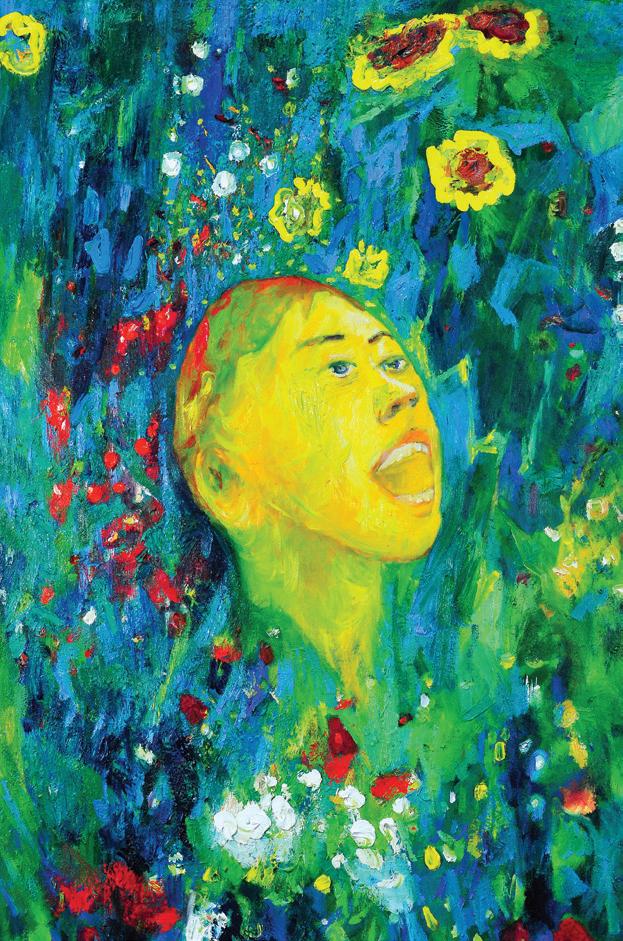

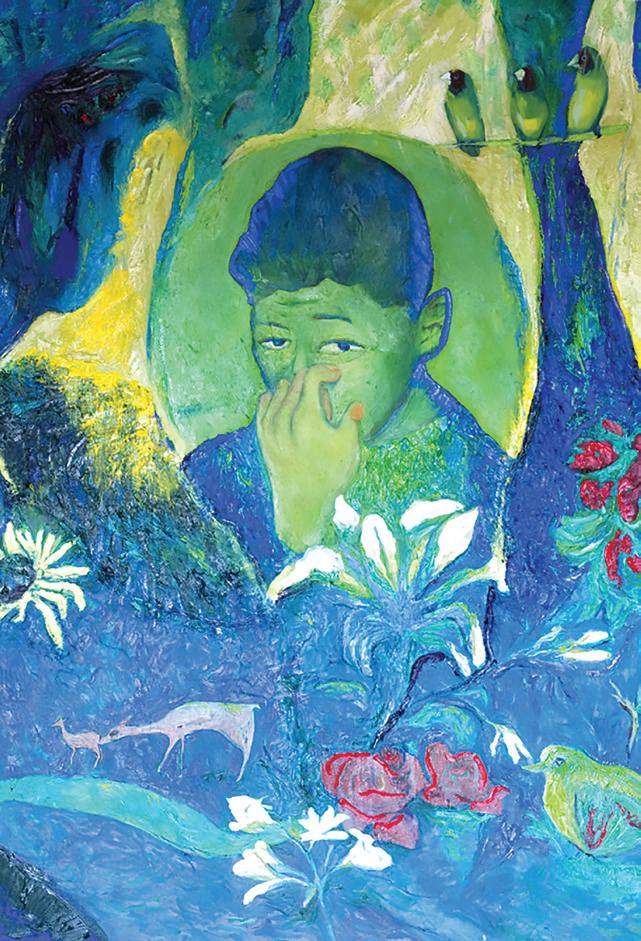

The artist, Kim Geun-tae, painted a huge work of art with an unfamiliar theme. The 100-meter-long artwork consisted of 77 large paintings of children with mental handicaps. At the invitation of UN Ambassador Oh Joon, who was the chairman of the Convention on the Rights of the Disabled, Kim’s paintings were also exhibited in Geneva and Paris.

In 2020, Kim Geun-tae exhibited his artworks under the theme of “May, Starry Wildflower” at the Asia Culture Center (ACC) in Gwangju. The ACC was built on the very block where the Jeollanam-do Provincial Office was located in 1980. The main building of the Provincial Office still stands as the historical site where the Gwangju Uprising came to a bloody end, symbolizing the spirit of democracy not only for the citizens of Gwangju but for many other citizens in the world.

Kim Geun-tae’s exhibition at the ACC triggered memories of four decades earlier. Back in May of 1980, Kim was one of the last remaining members of the civilian resistance who had taken over the Provincial Office, where they were to make their last stand. On May 26, there were rumors going around that the martial law troops were coming back into the heart of downtown to sweep away the resistance. That night, a brave female (who passed away this past February) picked up a microphone and shouted into the loudspeakers, “Citizens, help us. Citizens, let’s fight together.” Kim knew that that night might be the last of the fighting, as the small group of armed protesters were greatly outnumbered by the much better-armed military. But Kim could not forget his mother’s pleading, “Save your life!” In the darkness that night, he put down his gun and left the Provincial Office with a comrade.

Kim hid in his studio, and there he heard the nearby footsteps of soldiers. He still cannot erase from memory the sound of gunfire and screaming that he heard as the military troops made their final assault on the Provincial Office under darkness in the very early hours of May 27. He has lived his whole life with remorse for not being with his colleagues who resisted to the end against soldiers who had indiscriminately killed so many Gwangju citizens. But survivor’s guilt affected all Gwangju citizens who listened to the soldiers’ footsteps and gunfire that night in helplessness. to work as an art teacher at a high school in Mokpo. However, the sound of “You coward!” haunted him every day and night. Unable to live a regular daily life, he quit teaching and went to France.

Because of Kim Geun-tae’s harrowing experience, I wanted to interview the artist for the May issue of the Gwangju News. So, I called him to arrange for an interview. His son answered the phone and said that his father was losing his hearing. A few days later, I headed towards Mokpo to interview Kim with his wife at his studio in Muan (southwest of Gwangju).

THE INTERVIEW

Jennis: Thank you for giving your precious time. I have researched you and your artworks, but I want to learn more. You have said you went to Paris after marriage. How did you spend your time in France? Kim Geun-tae: I painted and painted human bodies at the Grand Chaumiere Academy. While painting, I constantly thought about humans, why we were born, and what we really are.

Jennis: It sounds like you took the time to find yourself while studying in Paris. What made you come back to Korea? Kim Geun-tae: I was crazy about painting in Paris. It was a time when I could forget myself. But I was sorry for my wife, who was supporting me by working as a teacher in an elementary school. I came back to Korea because I could no longer put such a financial burden on her.

Jennis: How was your life back in Korea? Kim Geun-tae: I continued to paint human bodies after coming back to Korea. I wanted to paint the human body rather than beautiful landscapes. I tried to find myself through the hurt of others. I heard that there were severely disabled children living on the island of Gohwado near Mokpo. So, I went to the island. Now, there is a

▲ Kim (fourth from left) at his UN exhibition presenting a portrait of Ban Ki-moon to the Secretary-General.

▲ “Like Wildflowers 2.”

bridge between Mokpo and the island, but at the time, I had to access the island by boat. I stayed there with the children for three years.

Jennis: What did you do there? Kim Geun-tae: There were children who lay on their backs and only looked up at the sky all their lives. I ate with my friends [Kim called the children his “friends”], and I tried to look at the world through their eyes. The children were born as innocent human beings but abandoned by the world. Looking into their clear eyes, I felt that they were true humans or angels who did not even know the words hate or kill. While staying with the children, I felt myself being cured of my trauma. I felt that the eyes of the children revealed their souls like wildflowers.

Jennis: You were living with them and painting them. Three years is not a short time. And you usually used red, yellow, and blue colors in your paintings. Is there a particular reason for this? Kim Geun-tae: I have a reason for choosing the primary colors. Like language, paintings also look luxurious if ambiguous colors are used. The more you hide who you are, the more sophisticated you look. People hide their true colors behind gray. I wanted to express innocence and clearness with nothing to hide.

Jennis: What are people’s general reactions to your paintings? Kim Geun-tae: The public was not familiar with paintings of disabled children. Nevertheless, I painted my “friends” in large-sized paintings and held an exhibition in Insadong in Seoul under the theme of “Like Wildflowers, Like Stars.”

Jennis: How were you able to exhibit your works at the United Nations in New York? Kim Geun-tae: I believed that even though my paintings were not well understood in Korea, there might be people in the outside world who could understand them. And I wanted to one day exhibit in places like the Pompidou Center in Paris and MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art] in New York. Some people appreciating my paintings in Insa-dong suggested that I have an exhibition at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Without knowing if there was a large space at the UN, I dreamed of creating a 100-meter-long exhibit of artwork there. And, one by one, people helped me to realize this. One person sent my profile of artworks to the UN and made a request for an exhibition for me. Another one lent me a vacant space to create large-sized paintings. At last, my dreams came true: Lee Nak-yeon, the governor of Jeollanamdo at that time, and Oh Joon, ambassador to the United Nations, recognized the meaning of my works and helped me exhibit them at the UN.

Jennis: What a story! They had an eye for the meaning in your art. You said your 100-meter-long artwork was made up of 77 large paintings. How long does it take to paint a work 100 meters long? Kim Geun-tae: It took me almost three years to finish the 100 meters of paintings, and it took a lot of paint to paint such large paintings. With my wife’s support, I was able to finish my paintings for the exhibition in New York.

Jennis: I heard that your eyesight and hearing are failing. What effect has this had on your life? Kim Geun-tae: I have been living without looking after my body, and that is why my eyesight and hearing have been deteriorating. People have worried about my lack of care for my body, but now I can better understand my “friends.” I have tried to die four times because of the May 18 trauma. Then one day, I suddenly realized that it should be my mission to deliver the message that the people who have passed away wanted to convey to the world. In this world of lookism, I have gotten a lot of messages from

▲ “Like Wildfl owers” ▲ “Th e Inner World.” ▲ “I Want to Feel.”

the children, who have the essence of beautiful human beings. Th rough my experience, I have come to think of opening an art healing center.

Jennis: I have heard from scholars and practitioners that art has healing powers. Do you mean you want to use painting for therapy for disabled children? Kim Geun-tae: No, it is rather the opposite. Until now, disabled children have been objectifi ed. But who can have clearer eyes and a clearer mind than the children? I think the treatment is needed for the people of the world with wounded souls. COVID-19 is a warning to a world that is divided into “useful” and “useless.” We have to think about what the message is that this pandemic has thrown upon mankind.

Jennis: And what do you think the message is that COVID-19 has sent us? Kim Geun-tae: In a faster and closer world, each of us is becoming more isolated and alienated. All the world communicates only with money. Th e prospects for a person’s life are so oft en impeded by the priority given to the interests of an organization or the interests of a nation. It has caused wars and sickened the Earth. We are losing the meaning of existence, of what the most precious value in human life is. So, I thought we needed a window of communication where the world could become one.

Jennis: So, you created a corporation called “Kim Geuntae and Friends of the Five Continents.” What specifi cally does the organization do? Kim Geun-tae: “Kim Geun-tae and Friends of the Five Continents” gathered paintings of disabled children living on fi ve continents and held exhibitions to commemorate the Pyeongchang Winter Paralympics. I hope that “Kim Geun-tae and Friends of the Five Continents” will take a step further toward peace on the divided Korean Peninsula and toward world peace through art.

AFTER THE INTERVIEW

Th e Jeollanamdo Art Museum in Gwangyang opened last March. Th e museum has bought Kim Geun-tae’s 100-meter artwork as a collection. Now, he is dreaming of someday exhibiting 200 meters of paintings at MoMA in New York or at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Just as with van Gogh and Th eo, I think that Kim Geun-tae has been able to create his artwork with the support of his wife, Choi Hosoon. During the interview, I sensed that their relationship is beyond merely that of wife and husband. I respect both of them for walking on the path of world peace through art. I am looking forward to seeing Kim Geun-tae’s paintings of peace at MoMA or the Pompidou Center someday.

Photographs courtesy of Kim Geun-tae. For more art and information on Kim Geun-tae, go to his website at http://m.kimgeuntae.com/

The Author

Kang Jennis Hyunsuk is a freelance interpreter who loves to read books and take photos of nature. She has been living in Gwangju all her life. She loves to talk with old ladies in the Jeolla dialect in the rural markets. Jennis feels sorry that the precious history-bearing dialects of the ancestors are fading away. She is surely a lover of Gwangju.

Remembering the Gwangju Uprising: 5.18

By C. Adam Volle

For many, the mere mention of “May” evokes pleasant thoughts of warm weather and joyful gatherings, but to the resident of Gwangju, “O-wol” (오월, May) quickly conjures up memories of ten days in 1980 (May 18–27) when violence, gunfire, and blood dominated the city’s streets. On this 41st anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising, the Gwangju News reissues an article written by C. Adam Volle in the June 2013 issue (“Remembering the Gwangju Democratic Uprising”). At the time, Volle was the online editor of the Gwangju News and later the editor of the print edition. — Ed.

Texas has the Battle of the Alamo. Israel has the Siege of Masada. Greece has the Battle of Thermopylae. And the people of Gwangju – along with every Korean who identifies with them – have their memories of May 18–27, 1980.

The short version of the story: Thirty-three years ago [now 41 years ago], some university students in Gwangju peacefully protested against their government. A brigade of the Republic of Korea (ROK) Army responded by breaking up that protest with such violence that even uninvolved passersby were killed. This cruelty so angered the population that seemingly everyone in the city fought back and made international news by forcing the soldiers out of town. The Army eventually did regain control, but the many civilians who died in the fighting quickly became martyrs, and the event has served as an important symbol for the activists who eventually transformed South Korea into a democracy.

The longer version of the story is more difficult. During a press conference in May of 2012 about his own Uprisinginspired exhibit, Seoul photographer Noh Sun-taek reminded his audience, “The remembering [of an event] has always been accompanied with forgetting.” He meant that societies’ traumatic experiences turn into those societies’ stories, but stories have requirements that reality does not. For instance, stories can never be as complicated, especially if you want a lot of people to listen to them. So, some details are emphasized, while others are ignored, depending on the needs of the people who are speaking. The process is much like the transformation of a novel into a movie script, or multiple books and interviews into a magazine article.

With that in mind, here is the longer version. Young-sam lost his lawmaker’s seat in the National Assembly for saying what everyone in South Korea already knew: The National Assembly itself was a fraud since the country’s constitution gave all the power to the man who wrote it – President Park Chung-hee. Every other representative in Kim Young-sam’s National Democratic Party immediately quit in protest.

On university campuses across the country, politically minded students once again took up the chants “Down with dictatorship!” and “Protect freedom of speech!” On the night of October 15, a thousand students from Busan National University held a torchlight demonstration in downtown Busan. The experienced riot police dutifully began teargassing and beating them. This time, however, something was wrong: Rather than dispersing, the crowd just got larger. Within 24 hours, over 50,000 people surrounded Busan City Hall. The ROK Army eventually had to send specially trained paratroopers to restore order, but by then the protests had spread to Masan and Changwon. Soon, activists promised, the whole country would rise up.

This all deeply disturbed Kim Jae-kyu, the Korean CIA director, so he reported to his boss that the protests were a serious threat. According to Kim, however, President Park’s response disturbed him even more: Park said he would give the order for soldiers to break the rule against shooting civilians. He also suggested Kim was not very good at his job. Kim thought the president was not very good at his job either and advised his boss to “govern with a broader outlook.” Then Kim shot him. In the man’s own words: “‘Bang! Bang!’ Like that.”

On that night of October 26, everything changed. A majority of South Koreans already wanted government reform, but now they expected it. After all, Park Chunghee had created the military regime; it only seemed natural that his death would end it. Foreign journalists caught the spirit of the times and began to write about a “Seoul

▲ The 5.18 Memorial Hall. (Schlarpi)

Spring” occurring in South Korea, a period of transition soon to result in long-awaited democracy.

But as every Korean knows, the arrival of spring is always followed by a sudden chill. There is a Korean expression for it: “The winter is jealous of the flower” (꽃샘 추위). According to General John A. Wickham Jr., commander of the peninsula’s U.S. forces, many high-ranking officers in the ROK Army considered the end of their political influence to be the end of the country. They thought that military men believed in such lofty ideas as duty, honor and sacrifice, but that civilians and the media only pursued their own “selfish interests.” In particular, the generals could not imagine allowing a president with no military experience to control their armies. These “politicians in uniform” (Wickham’s term) promised they would not stop democratization, but in private, General Wickham’s sources told him differently: They planned to regain the Blue House.

Their new leader, General Chun Doo-hwan, chose a dramatic moment to make his move: the same weekend in which everyone thought the nationwide Democratic Movement had won. On Friday, May 15, Korean citizens marched all over the country, over 100,000 in Seoul, all demanding that the National Assembly finish creating a new constitution and provide a fixed date for the direct election of a new president. The Journalists Association of Korea took the opportunity to announce that its members would strike if the government did not free the press from restrictive censorship laws. Prime Minister Shin Hyeonhwak essentially agreed to these demands, and President Choi returned early from traveling. Feeling confident, the Movement’s leaders asked all their supporters to take the weekend off. If the Assembly did not get to work on Monday, they could demonstrate again. All the protesters immediately obeyed, except for Gwangju’s.

MAY 18

In 1980, Dr. Dave Shaffer was working at Chosun University. “I got a phone call from Chosun University authorities saying that the university was closed until further notice to everyone – students, faculty, and staff.”

As Shaffer and the rest of Korea would later discover, a secret cabinet meeting occurred the previous night in which Chun Doo-hwan had extended martial law throughout the nation. To prevent new protests, the general ordered the arrests of activist leaders at night. He also ordered all political activities be banned, reinforced restrictions on the media, and sent paratroopers from the ROK Army’s Special Forces to close down the most troublesome universities.

At the main gate of Chonnam National University, 30 paratroopers watched as a crowd of 300–500 students gradually amassed in the street. The soldiers wore patches identifying themselves as members of the Army’s 7th “Pegasus” Brigade, veterans of the Vietnam War usually tasked with guarding the DMZ. They carried unusual clubs. Fifty Chonnam students decided to sit down and start shouting, “End martial law!” and “Withdraw the order to close the universities!” They did not understand that these “black berets” had different intentions than in Busan; they had been given new “chungjeong” (충정) training that emphasized offense over defense. In one session, they had watched an instruction video that suggested breaking demonstrators’ collarbones and shooting anyone who ran.

The paratroopers rushed the students. Some of them put aside their clubs in favor of their daggers. Others used their guns’ bayonets. When the students ran, the soldiers followed, and while pursuing them, the soldiers also attacked anyone else they happened to see. The first person

they killed was a deaf man oblivious to their presence. Many more after him were killed in ways that should not be described here. The soldiers stripped near naked those arrested and put them in trucks bound for prison camps. Multiple people later reported sexual assault. Others were never heard from again.

MAY 19

Despite the paratroopers’ aggression, the same phenomenon began occurring in Gwangju that scared Kim Jae-kyu in Busan. The crowds did not disappear; they got larger, and they fought back.

“They had only forks and spoons, only weapons found in the kitchen,” one sixth-grade student recently told the Gwangju News. The boy is not wrong. Kim Nam-ju writes of “the kitchen knives of the boys who rushed out of restaurants” in his poem “Don’t Sing of May as a Blade of Grass that Withers in Wind.”

The university students’ outraged friends and family did not limit themselves to silverware. Any handy weapon served a purpose for battle, from car tools to river stones. Some got creative by attaching their knives to the ends of bamboo poles. Others made Molotov cocktails (a firebomb requiring a bottle of kerosene or other fuel, a rag, and a lighter).

At 11 a.m., the paratroopers brought out new weapons of their own: armored vehicles, tanks, and flamethrowers. By 11 p.m., ordered reinforcements were summoned; a multitude of students from Gwangju’s male high schools had joined the fight.

MAY 20

A German reporter named Jürgen Hinzpeter arrived to obtain footage. He later wrote, “Never in my life, even in filming the Vietnam War, had I seen anything like this.”

Panic had begun to spread. “Kill them or they’ll kill us!” someone overheard one black beret shouting. Officers outside the city gave different advice to the fresh soldiers going in: They should show restraint to avoid further angering the population. On the Army’s loudspeakers, demands for citizens to return to their homes began to sound more like pleading. “Please return to your homes … Your families are worried about you.”

Reinforcements brought the military’s strength to just under 3,000 soldiers in addition to the already 18,000 riot police fighting, but those 21,000 men now faced over 100,000 protesters – and the number just kept growing as Gwangju residents drove their loudspeaker trucks and buses through every neighborhood, calling on every able-bodied person they saw to join the struggle. Many were pushed into action when the bodies of the dead were displayed on carts out on the streets.

At Mudeung Stadium, 200 taxi and bus drivers met to pledge their assistance, developing a strategy of driving their vehicles side-by-side up the roads where police were blocking to create moving walls that no line of riot shields could push through. By evening, a sea-like mass of demonstrators had surrounded the Army’s headquarters in the Jeollanam-do Provincial Office at the end of Geumnam Street. From its windows, the Special Forces commanders watched the city’s Tax Office burn to the ground.

MAY 21

“Citizens, let us save Gwangju!” Jeollanam-do’s governor shouted through his speaker, but very few people could hear his slogans over their own cheering and singing. It was 11 a.m., and below the governor’s helicopter, the multitude’s edge now laid no farther than ten meters from the Provincial Office’s defensive line.

Despite their closeness, violence between the two sides broke out only in small bursts because the people of Gwangju believed the Army was leaving. Tragically, they did not know more.

Earlier that morning, the Army had replaced its on-site commander with a new general who intended to make his name breaking the “Gwangju riot.” Shortly after 10 a.m., the new management gave each soldier guarding the Provincial Office a cartridge of real bullets and told him the secret signal on which to shoot into the crowds. The signal came at 1 p.m. sharp: Outside, the muggy air suddenly filled with a recording of Aegukga (애국가), Korea’s national anthem.

▲ Sculpture at the 5.18 National Cemetery. (Ulanwp)

▲ One of the ten mural sculptures at the 5.18 National Cemetery, 3rd left. (Ulanwp)

MAY 22–26

The soldiers’ ten-minute shooting spree killed 54, wounded more than 500 and crossed the final line; the community’s response came within two hours of that same day. Stores of M-1 carbine rifles in Gwangju’s police stations suddenly disappeared – often with the blessings of the local police – and by 3:20 p.m., the paratroopers took fire from the new “Citizens’ Army of Gwangju.” By May 22 at 5 p.m., the Army abandoned the Provincial Office to escape heavy machine gun fire. By 8 p.m., every soldier had left the city.

The resulting community of “liberated Gwangju” enjoys a near-utopian reputation in Jeollanamdo. To borrow the Bible’s description in Acts 2:44 of the first church, “All the believers were together and had everything in common.” During that time, Gwangju’s overjoyed citizens are said to have organized food distribution, cleaned up, policed their neighborhoods, and completed any other tasks without any hierarchical management. Others such as Dr. Shaffer remember a much more worrisome time and consider the standard description to be a rose-tinted view.

To help decide big questions that concerned the whole city, the people voted in meetings that attracted about 100,000 people. Those meetings became very passionate from the spontaneous nature of the Uprising. Gwangju’s residents emerged from all the excitement to realize that their city was still surrounded by tanks, they would eventually run out of food, and they did not know what to do next.

A group of prominent and respected elders in the community stepped forward to form the Citizens’ Settlement Committee (CSC), with the purpose of negotiating the city’s surrender. They hoped to obtain from the Army an apology, payment for the victims, and a promise not to punish anyone involved in the protests. As a gesture of goodwill, they began by collecting some of the guns taken by Gwangju’s protestors and gave them back to the Army in exchange for the freedom of arrested activists. to give up, what would be the point of all the fighting? And how could anyone trust the government not to take its usual revenge on everyone involved? The only option was to continue the armed revolution Gwangju had already begun. To stop the “surrender faction” of the CSC, activists and students staged a sort of coup and formed their own Citizen-Student Struggle Committee (CSSC). Through a mix of good argument and physical intimidation, they took away the CSC’s power. A 29-year-old named Yun Sangwon became their spokesman.

“Yun Sang-won was maybe the only one who had a strategic view,” an activist later told reporter Bradley Martin. Yun believed nobody would remember Gwangju as an example if its uprising ended with a simple surrender. “[He] wanted to complete the rebellion, put the final touch on it.” That final touch would result in his death.

MAY 26–27: THE MASSACRE

“We declare to the nation that 800,000 Gwangju citizens will fight to the end!” read the CSSC’s resolution at Democracy Square meeting on May 26. When the end did come, in fact, the CSSC discovered it had spoken for roughly 200.

Of those, the CSSC sent home about 50 women, girls, and boys, leaving “80 people who had completed military service, 60 youth and high school students, and 10 women” (George Katsiaficas in Asian Unknown Uprisings: South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century). The remaining 150 barricaded themselves inside the Provincial Office and settled into their positions. The ROK Army’s operation began at roughly 2 a.m. in the early hours of May 27. Its tanks drew up to the Provincial Office around 4:30 a.m. while paratroopers attacked through the rear entrance. With many of the CCSC members having ten minutes of training in using their weapons, the battle did not last long. The government would later declare that two soldiers and 17 CSSC members died in the fighting. Yoon Sang-won was shot in the kidney and then burned to death by a fire.

However, the desired effect of his sacrifice soon began to materialize. “Chun Doo-hwan’s position seems less secure,” General Wickham reported to Washington, D.C., soon after.

“Chun Doo-hwan is a marked man,” the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung declared more bluntly on May 30.

The new leaders of South Korea never fully recovered from Gwangju’s ruining of their debut. They lost effective power seven years later.

Special thanks to Dr. Dave Shaffer, Yoon Sang Soo, and Tim Whitman. Arranged by David Shaffer.

▲ Left and right: Human remains await a proper burial.

Odds and (Dead) Ends

Whistling Past the Graveyard

By Isaiah Winters

Every six months to a year, I cobble together an assortment of misfit findings from my many odd experiences in the City of Light. Though each would be a research dead end unworthy of its own article, together they make for a decent miscellany of notable oddities. In this issue, I tack on more than a few worthwhile afterthoughts that didn’t get their day in the sun for varying reasons. These addenda range from scattered human remains and hidden cypress forests to semi-shuttered expat bars and urban army trenches – all within our fair city of Gwangju. There’s a lot to sift through, so let’s get right to it.

THE BONEYARD STALKER

In last month’s Lost in Gwangju, I mentioned the removal of thousands of corpses across the city’s urban parklands to make way for the Gwangju Private Park Special Project that’s gathering steam following the expiration of the sunset law protecting said parks. I didn’t think widescale exhumations would start quite so soon, but about a week after submitting that article, I came across a massive graveyard on the backside of Maegok-san, where roughly a third of the corpses had already been disinterred and removed as part of the special project. I decided to take a careful walk around the many hillside graves, both as a solemn gesture following the article I’d just finished and as a way of scrutinizing any signs of negligence during the hasty body-removal process.

To my surprise, it didn’t take long to find plenty of bones scattered about the area’s numerous burial mounds. I’m not exactly sure how gravedigging and body removals work in Korea, but the human remains and toppled gravestones I saw seemed like sloppy work. To get an idea of who was

doing this work on behalf of the special project, I checked the calendar for what’s called a “ghost-free day” (손이 없는 날), which is traditionally seen as a day that’s good for moving house or changing gravesites, as ghosts are supposedly inactive then and therefore unable to cause the living any trouble. The weekend of April 10–11 was “ghost-free” according to the lunar calendar sites I found online, so I paid the graveyard another visit then hoping to see the process in real-time.

That Saturday, I saw no one at first, that is, if you don’t count the many fragments of people scattered about the freshly dug graves. In that regard, I found more and bigger bones than on my prior visit, not to mention many tatters of burial shrouds (수의), which was rather disconcerting. On my second visit that same weekend, I caught sight of a man sitting next to a grave in the distance. He looked a bit unsettled and out of place, much like myself. As I walked the rows above him, he spotted me, stood up, and slowly made his way over to where he’d anticipated I was headed. In response, I made a few erratic direction changes and then left, not wanting to strike up a conversation with another weirdo in a graveyard just before sunset. It’s actually not the dead I’m afraid of – it’s the living.

URBAN CYPRESS FOREST

On the opposite side of Maegok-san, just behind the Gwangju National Museum, there’s a large but little-known stretch of cypress trees that provide one of the city’s most convenient escapes from the bedlam of urban life. I used to think that the cypress forests of Hwasun and Jangseong were the closest, but this one’s literally a neighborhood away from home and quite impressive in size considering how deep within the city it is. There are pleasant, fernlined trails from top to bottom that snake back and forth through all the incredibly tall trees, which helps slow visitors down to maximize their time among the serene setting. As you walk down, the trails eventually end at a thicket of Sasa bamboo (섬조릿대), which gives you no other option than to return back up the lush, forested hillside to complete the circuit of meandering footpaths. Article-wise, there isn’t much else to say about this place except that it’s a must-see for anyone seeking tranquility without leaving the City of Light. Just remember to bring bug spray.

BELATED FAREWELL TO SPEAKS

I never really got to say goodbye to Speakeasy, one of downtown Gwangju’s longest-standing expat bars that struggled through the pandemic and sadly gave up the ghost last year. I’d gone there off and on since my arrival in 2010 and, although I never became a regular that anyone would remember, the place left an impression on me. I missed its farewell weekend because I figured it’d be packed and so stayed home, not wanting to contribute to any potential headlines the following week bearing words like “virus,” “bar,” and “foreigners.” I was also hosting a few friends from another, harder-hit region of the country that weekend, so I felt a little more of a burden to play it safe. From those who’d attended, I later heard that it was actually a fairly normal weekend and not all that crowded. It seems that so many wellestablished businesses across the globe expired in the same subdued way – without much hijinks or fanfare. It’s yet another example of COVID-19’s impact, which has quietly killed a lot more than just people. Ultimately, peripheral lurker that I was, I didn’t feel like the right person to write a proper eulogy for the place.

Though just a fly on the wall, somehow I still possess flashes of memory from Speaks that I fondly recall. For instance, my first memory there was going in with a wallet full of cash and then leaving in a vertiginous state with barely a single taxi fare left. (This would go on to be the ritual for practically every visit.) I later remember holding a lover’s hair back in the winter cold as her “technicolor yawn” flecked a nearby sidewalk – the result of that night’s overindulgence. On another night at Speaks, I remember having an extended chat with a pair of talkative guys who later invited me to a club, a veiled invitation that likely would’ve ended in a manly ménage à trois had I not turned them down. On a later visit, I ran into a higherup in the police force who used to be my student. That night, he was sharing drinks with his new teacher, probably the best-known pugilist of the local expat community, whom I’d seen get in a donnybrook over a game of pool some ten years back. As for my last visit to the living Speakeasy, it was during the fundraiser event for the Australian wildfires of 2019–2020, where I estimate half the night’s sales were to yours truly. Today, although Speaks is no longer officially open, you can see here that legendary bars never truly close.

▲ Left: Spring (and mosquitoes) are back in Maegok-dong’s cypress forest. Right: A bar’s-eye view of Speakeasy’s iconic mural.

TRACKING URBAN TRENCHWORKS

Over the last month, my switch to more local, urban hikes within Gwangju has yielded surprising finds, the most interesting of which have been army trenches and dugouts. There must be lots of them because in a short time I’ve come across three separate entrenchments in different areas of the city. One is an extensive network of tire-lined trenches at strategic places along an otherwise uninspiring hilltop. The site seems to have been decommissioned for quite some time, given how overgrown and hard to spot it was at first. Although it’s a legit hiking trail that’s completely open to the public, I don’t feel comfortable naming it here due to its close proximity to highly sensitive military installations. In terms of an article, the thought of writing an entire piece about hiking a trench-lined urban hill and then not sharing the name and location seemed like too much of a tease.

On yet another urban hilltop, I came across a lonely dugout that alone wasn’t very interesting, though its location and orientation were intriguing. It was atop the hill nearest the Sandong Bridge (산동교) in Dongnimdong. The December 2020 edition of Lost in Gwangju featured this bridge, which was the only site in Gwangju where fighting took place during the Korean War. (Long story short, the defenders detonated the bridge, took up positions in the nearby hills, and then fell back after an hour of fighting.) The little dugout I found atop this particular hill faces the bridge and, although it certainly doesn’t date back to the Korean War, it does suggest a postwar military presence on this strategically located hill. It makes you wonder whether the city’s defenders were ever nearby. Sturdy fencing and private property have prevented me from snooping around the hillside even more, though I suspect there’s more to see there. After digging around online, however, nothing came up, making any potential article dead on arrival.

By far my favorite trenches are along another sleepy hilltop within the metropolitan city limits. These trenches are particularly notable for the figures occupying them day and night: plastic cutouts of North Korean soldiers. Years ago, I’d found the exact same cutouts at a decommissioned military site elsewhere in South Jeolla, but after forgetting to mark the spot on a map, it took me years to relocate the cutouts. When I mentioned this to a friend, he said he knew of some right here in the city and helped guide me to them. I’m hugely grateful for that. In the end, the reason why I won’t write up more on this find is that I don’t want to be responsible for any dummies who go there in search of a souvenir. So, to keep our lads in top fighting condition, I’ll end this month’s miscellany of odds and (dead) ends here.

The Author

Originally from Southern California, Isaiah Winters is a Gwangju-based urban explorer who enjoys writing about the City of Light’s lesser-known quarters. When he’s not roaming the streets and writing about his experiences, he’s usually working or fulfilling his duties as the Gwangju News’ heavily caffeinated chief proofreader. You can find more of his photography on Instagram. @d.p.r.kwangju

▲ A wall of former patients.

Sorok-do: Island of Patients

By Melline Galani

When I visited Sorok-do (Sorok Island) on an organized trip, I did not know what to expect. We were told that Sorok-do has long been called the “Leper Island” because patients suffering from leprosy are treated there, as they have been for more than one hundred years. To be honest, I did not and still do not know much about the disease. I thought it was an ailment spread during the Middle Ages that had been eradicated a long time ago.

According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)1 leprosy, also known as Hansen’s Disease, is an infection caused by a slow-growing bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. It is one of the oldest diseases in recorded history. The first known written reference to leprosy is from around 600 B.C. It primarily affects the nerves of the extremities, the skin, the lining of the nose, and the upper respiratory tract. With early diagnosis and treatment, the disease can be cured. People with Hansen’s disease can continue to work and lead an active life during and after treatment.

Since antiquity, is was believed that people with Hansen’s disease should be kept isolated in colonies so as not to spread the disease. They faced discrimination, isolation, and hardships beyond imagination. Sorokdo National Hospital, situated on the island with the same name, reflects the country’s colonial legacy. Sorok-do is home to Korea’s largest leper colony.

Being on an organized trip, we had a guide explaining things in detail during the tour. There are also bilingual descriptions in almost all areas. The island can now be

▲ Rehabilitation Center

reached by car because a bridge connecting it to the mainland was built twelve years ago. Before that, the island could only be reached by boat, making it perfectly isolated from the mainland. As described below, this resulted in the Japanese building a concentration camp on Sorok-do.

The hospital was built in 1916 (then known as the Sorok-do Charity Clinic)2 under the leper quarantine policies of the Japanese colonial administration (which enacted the Leprosy Prevention Law in 1907). Sorokdo National Hospital has cared for a colony of Hansen’s disease residents since then – the largest in Korea – and the island infamously served as a concentration camp for these patients throughout the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945.3 At its peak, Sorok-do was home to about 6,000 Hansen’s disease patients, and the hospital's busiest department was the operating room where the lepers were sterilized.

Long story short, thousands of people were starved and tortured on the island. First by the Japanese until 1945, and then by the Korean authorities, who continued to quarantine lepers on Sorok-do until 1963. In addition to forced labor, patients were subjected to forced vasectomies, abortions, and amputations both as part of medical experiments and out of fear that the disease was hereditary.

During the Japanese occupation, one of the directors of the hospital was Masato Suho. He built a statue of himself and urged people to worship it (the statue no longer exists). In 1942, a patient named Lee Chun-sang killed the director and he, too, was executed. Discrimination and atrocities continued on Sorok-do even under the Korean administration. For example, although a few select patients were allowed to have children, these parents could only see their offspring once a month, and the children had to leave the island after they reached school age. Men were not allowed to marry fellow patients unless they first underwent vasectomies.4 Furthermore, on August 22, 1945, eighty-four patients were killed by armed staff during a conflict between hospital employees and patients.5 Today, the old hospital building has been replaced by a new, modern structure. The hospital is still in operation, in part dedicated to the care of dementia patients. Anyone diagnosed with Hansen’s disease can be admitted to the hospital and may leave after treatment.

The island has a tranquil but somehow desolate beauty, with two long beaches and pine trees. But its history is stained with blood and tears. As it is not entirely open to the public, we could visit only a part of it. Among the places we visited, two locations stuck deep in my mind: the autopsy lab and the rehabilitation center.

The autopsy lab is composed of two rooms, one for autopsies and one for sterilizations. The rooms retain the smell and screams from the past. It is the desolate view that stuck with me. The lab’s most striking feature was the operating table, used for vasectomies and sterilizations, lying alone in the middle of a quiet room. Feelings of sorrow and regret accompanied me on the tour.

The rehabilitation center lies next to the autopsy lab in a red-brick, H-shaped building comprised of small, dark, and cold detention rooms (the center was not a prison but looked as if it were). Everything looked horrible, as in a horror movie. Not even one’s imagination can picture the inhuman treatment the people once detained here must had suffered.

But not everything is sad about Sorok-do. There is a central park, a beautiful garden with monuments, and nicely tailored trees. A stroll on its paths may bring light and joy to a burdened mind after seeing the above-mentioned places.

Th e tour guide also told us the story of two Austrian nurses, Margreth Pissarek and Marianne Stoeger, who came to the hospital in 1962 to help the patients. Th e two Austrian nurses not only corrected many misbeliefs about leprosy, but also sought some medicine and other aid for the patients and their children, even asking their own families and acquaintances to send medicine, while getting nutritional supplements and milk powder for the children who suff ered from malnutrition. For children isolated from their parents, they built a childcare center and made clothes for them by hand.6 Th ey stayed for forty years, and for all the good they did, they are considered angels among the island’s population.

Today the Sorokdo National Hospital, in addition to the treatment of patients, houses the Hansen’s Disease Museum. Rather than being a site of horror, today it is an island of healing.

I think Sorok-do is a must-visit place for its history, something that we should not be allowed to forget. For my children and me, it was a memorable experience that also taught a history lesson that all generations, especially the young, need.

▲ Hansen’s Disease Museum

Resources

1 CDC. (2017). Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy). Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/leprosy/index. html 2 Sorokdo National Hospital. (n.d.). History. Accessed February 23, 2019. http://www.sorokdo.go.kr/eng/html/content. do?menu_cd=04_02&depth=hi 3 Jeff reys, D. (2011). Sorok Island: Th e last leper colony.

Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/ asia/sorok-island-last-leper-colony-5334621.html 4 Jeff reys, D. (2011). See above. 5 Lee, H. (2018). Books shed light on former leper colony. Korean

Biomedical Review. https://www.koreabiomed.com/news/ articleView.html?idxno=2381 6 Chang, I. (2016, February 11). Angels descend on Sorokdo.

Korea.net. https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/People/ view?articleId=132478

SOROK ISLAND 소록도

Address

Sorok-ri, Doyang-eup, Goheung-gun, Jeollanam-do 전라남도 고흥군 도양읍 소록리 Phone: 061-830-5637

The Author

Melline Galani is a Romanian enthusiast, born and raised in the capital city of Bucharest, who is currently living in Gwangju. She likes new challenges and learning interesting things, and she is incurably optimistic. @melligalanis

Budva

The Heart of the Adriatic

By Mirjana Adzic

Have you heard of Montenegro? It is a small country on the Balkan Peninsula in southeastern Europe, and the translation of its name literally means “black mountain.” Montenegro is a rather small country with a territory of 13,812 square kilometers and a population of just over 620,000 people, but it is nonetheless home of some of the prettiest nature and scenery. Montenegro has very high mountains, where you can enjoy skiing in the winter and, at the same time, a captivating seaside with some of the most beautiful beaches along the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Our highest mountain peak reaches 2,535 meters above sea level, and those who enjoy mountain climbing can fi nd some of the most challenging trails. Because of its natural diversity and complexity, Montenegro is home to all four seasons, with winters getting cold, down to –20 degrees Celsius in the north, and summers reaching up to 40 degrees in the south.

One of the most famous places in the south of Montenegro is a charming city of roughly 20,000 inhabitants called Budva. Budva is 2,500 years old and is one of the oldest settlements on this part of the coast. In the heart of Budva as it exists today, you can fi nd the old town, which is fully encircled by defensive stone walls, inside which are wellpreserved towers, embrasures, fortifi ed city gates, and a citadel. If you do go inside the Old Town, do not miss out on a chance to see the citadel dating back to the 15th century, where inside you can fi nd the Maritime Museum of Budva. Also, you absolutely should see the Museum of the Town of Budva, which is in the very center of the Old Town. Th ere you can fi nd a permanent exhibition of archaeological and ethnographic collections, and the museum tries its best to refl ect the life and historical conditions brought by the interchanging of Illyrian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Slavic and other cultures that are specifi c to this region. Many small, narrow streets inside the town hide wonderful restaurants that sell traditional Montenegrin seaside dishes such as black risotto, octopus salad, buzara (seafood slowly cooked in wine), as well as staple dishes such as Njeguški pršut (dry-cured ham) with cheese and olives, and priganice (fried dough, ideal for breakfast). Montenegro is really the best place to visit if you enjoy tasty food. With an average height of 183 centimeters, Montenegrins sure know how to eat!

As tourism is the main driver of Budva’s economy, there are many wonderful beaches to explore nearby. Mogren Beach is right outside the Old Town and is arguably the most famous for tourists. Just a fi ve-minute drive from the city center, you will fi nd Jaz Beach, which is very long and spacious and in previous years was home to the Sea Dance Festival, where performers such as Madonna and Th e Rolling Stones entertained audiences.

In Budva Riviera (the name for the whole province), you can fi nd old villages fi lled with local culture and spacious beaches, especially in a place called Bečići. Two of the most recognizable places in Montenegro are for sure

▲ Budva’s Old Town.

Miločer Beach and Sveti Stefan. Sveti Stefan is an island connected to the mainland filled with 15thcentury villas known as the most photographed place in Montenegro. Today, the island is a part of a luxurious resort, and only guests of the hotel or one of the restaurants in the resort can enter Sveti Stefan.

Budva is also quite famous for its vibrant nightlife in the city center during summer, with many open bars and clubs that attract young people. However, right outside of the city center, Budva also offers beautiful places to relax for those who prefer calmness and the enjoyment of nature in the heart of the Adriatic.

▲ A beach in Budva.

▲ Budva Marina

The Author

Mirjana Adzic was born and raised in Montenegro. After completing her undergraduate degree, she moved to Seoul where she currently attends Ewha Womans University. Mirjana enjoys traveling, encountering new cultures, reading, and learning foreign languages.

The Cosmopolitan Classroom

Interview with Lindsay Herron

I thought I was aware of what cosmopolitanism entailed, that is, until I saw a presentation on cosmopolitanism and EFL learners at a Korea TESOL event. I wasn’t sure what this meant, but it piqued my interest and I attended the presentation. I came away from the presentation with a broader understanding of cosmopolitanism and how it fi ts into EFL pedagogy. Th at presentation was delivered by Lindsay Herron, who has been teaching in Gwangju for over a decade. Th ough I knew that she was super busy with a myriad of projects, she was fi nally able to do this interview for the Gwangju News. — D. Shaff er

Gwangju News (GN): I know that you have done a lot of study in cosmopolitanism. When I think of a cosmopolitan, the fi rst thing that comes to mind is someone who is well-to-do, educated, speaks several languages, and travels to many diff erent places. I assume that’s not what you’re studying…is it?

Lindsay Herron: Th at’s what I used to think of when I heard “cosmopolitan,” as well! But when we talk about cosmopolitanism and cosmopolitan orientations, that’s not exactly what we mean. Cosmopolitan is actually a term that dates back to Ancient Greece and the Stoics; the Cynic philosopher Diogenes (c. 390–323 BCE) is credited with coining the term when he declared himself a kosmopolites, or “citizen of the world,” instead of a citizen merely of the nation-state. Th e idea was adopted by Enlightenment thinkers, including the infl uential philosopher Immanuel Kant, to advocate for more universalist perspectives and moral obligations (Hansen, 2014). Today, cosmopolitanism has been embraced by a wide variety of fi elds, from anthropology to sociology, and media studies to political science, as a framework for understanding the complex intersections and interactions between the local and global. Most conceptualizations of cosmopolitanism today go beyond the local and global, however, to encompass all the myriad diff erences that are inherent among us. Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah (2006) describes cosmopolitanism as comprising the entwined concepts of pluralism and fallibilism – that is, a recognition of the existence of multiple perspectives and also the limitations of your own. In many ways, cosmopolitanism is about relativizing the self, about viewing yourself and your understandings within larger contexts and from other perspectives. It’s about delighting in diff erence, seeking out new ideas and experiences, and engaging with others in a welcoming, open way – and on their own terms. It’s also about our responsibility as citizens of the world to act beyond borders with an eye toward our shared ethical obligation to others. If cosmopolitanism had a slogan, Appiah (2006) says, it might be “universality plus diff erence” (loc. 2206). Th at is to say, cosmopolitanism is a way to both appreciate and move beyond diff erences to a central core of shared humanity.

Cosmopolitanism is also about growing and changing through encounters with diff erence. When we encounter a new perspective, we experience a sense of disjuncture between the new and the known. We become aware of previously unknown paths and possibilities in life, which in turn highlight the limitations of our own taken-forgranted beliefs, assumptions, and biases. As we start to critically consider and question our own enculturated versions of “normal,” we come to understand that “normal” is relative at best – that there are manifold ways of being in the world. Th is expanded awareness of the

world changes us; we approach both new perspectives and old beliefs with a more critical eye, adopting the ones that suit us, while cultivating more hospitable, empathetic, humanizing views of others. Cosmopolitanism in this way can foster community, connection, and belonging as understandings of boundaries, self, and other evolve.

GN: Cosmopolitanism “fosters community” – that’s a nice way of putting it! So, what got you interested in the study of cosmopolitanism?

Lindsay: Th e fi rst doctoral course I took at Indiana University was a survey course incorporating a wide range of literacy-related topics, including cosmopolitan literacies. Th e following summer, I took an intensive reading elective on cosmopolitanism that allowed us to delve deeply into and engage with a variety of interdisciplinary perspectives on the topic. I enjoyed this course so much that, as part of my fi nal project, I draft ed a research proposal that eventually evolved into the basis for my dissertation.

Cosmopolitanism appeals to me for many reasons. First and foremost, I think it’s an important topic, particularly considering the xenophobia and intolerance so rife in today’s world. With its dual emphases on ethical obligation and criticality, cosmopolitan education seems a promising way to encourage more open, empathetic perspectives; to question what we “know” and believe; to imagine new and better alternatives; and ultimately to build a better world. Second, I love how interdisciplinary it is. As part of my research, I’ve gotten to read books and articles from scholars around the world in the fi elds of media studies, cultural studies, political science, anthropology, social science, tourism theory, philosophy, philanthropy, and (of course) literacy and education.

Th e third reason I fi nd cosmopolitanism fascinating is that it’s immediately, viscerally, and visibly relevant to my life (and yours, too, if you’re reading this!). One key aspect of cosmopolitanism, dating back many millennia, is the selective adaptation of global trends to local tastes. K-pop, with its Western inspirations and infl uences, local performers, and global dissemination? Cosmopolitan! Th e cafes that dot Gwangju’s streets, serving coff ee and European delicacies matching Korean tastes, with hours suiting Korean preferences? Cosmopolitan! Th e food court at Costco, where Korean customers take the condiments provided as hot dog toppings (onions, mustard, ketchup, and relish), mix them together on a plate, and eat them as a side dish? Cosmopolitan!

Learning about cosmopolitanism has helped me understand the mélange of cultural infl uences surrounding me here in Korea and also reminded me that fostering a cosmopolitan mindset – especially one that gives others the benefi t of the doubt and seeks a deeper understanding of situated practices – is a continuous process. I don’t always manage it, but I fi nd that pushing myself toward more cosmopolitan openness and striving to consider other perspectives can help when I feel frustrated or impatient with life in Korea. For example, to be honest, I used to be fairly disdainful of the “misuse” of hot dog toppings at Costco; since recognizing this activity for what it was (the contextually appropriate creation of banchan) and as a fundamentally cosmopolitan practice, though, I have much more appreciation for it.

GN: Cosmopolitanism is an aspect of society, or societies, but how does it fi t into education?

Lindsay: Cosmopolitanism is a popular lens for educational practice today. In many ways, in fact, education is inherently cosmopolitan! In cosmopolitan theory, transformation is spurred by encounters with the new that draw people’s attention to the limitations of their previous perspectives and simultaneously present new possibilities. Th at’s education in a nutshell, isn’t it? Hansen’s (2014) work on cosmopolitanism explicitly compares embodied cosmopolitanism to education, describing education as “a transformative experience of becoming aware of one’s skills or lack thereof, of grasping their signifi cance or their triviality, of discovering (oft en with surprise) that knowledge is a more many-sided

▲ Cosmopolitanism includes an ethics of care: empathy, hospitality, and compassion for others. Th e author and Mitzi Kaufman at the fi rst Gwangju Queer Culture Festival in 2018.

concept … than simply having information” (p. 10). Researcher Ninni Wahlström (2014) also fi nds “active, potentially cosmopolitan-minded meaning-making” (p. 130) in classes that encourage curiosity and wonder as students encounter new ideas and thoughts. She describes this as an “aesthetic-refl ective experience” that helps students create new meaning, and she encourages a classroom that “includes inner feelings, imagination, and self-refl exivity” (p. 125). Th e question, then, isn’t really whether cosmopolitanism is related to education but rather how teachers can create in their lessons a sense of embodied cosmopolitanism, that sense of “wonder, triggered by substantive encounters with the new” (Hansen, 2014, p. 9) that encourages new understandings and new meaning-making.

GN: Can you give us some ideas as to how teachers can introduce cosmopolitan meaning-making into their classroom teaching?

Lindsay: It might help here to think of cosmopolitanism as entailing two separate but entwined elements: (a) an ethical obligation to others that might emerge as empathy, openness, hospitality, and a concern for others’ wellbeing (including distant/diff erent others) and (b) the potential for refl ective transformation through encounters with diff erence. Th ese can be achieved by creating opportunities for disjuncture, gently disrupting what students “know” or believe is “normal” to encourage the pluralism and fallibilism described by Appiah. Simply teaching a foreign language and introducing various aspects of other cultures is, in eff ect, quite cosmopolitan! Our teaching styles, methodologies, educational priorities, and approaches to classroom management are oft en diff erent from what students have experienced, giving them new perspectives on what “education,” “learning,” and “success” can look like. For foreign teachers, in particular, it can be useful to incorporate stories about our lives, photos of our friends and families, and information about our favorite things, giving students new and varied ideas about what “foreigners” are like. Related to this, I also strongly encourage foreigner teachers to try to disrupt the prevailing stereotypes here (e.g., by enjoying spicy foods, using chopsticks, being able to speak Korean), which can help to highlight generalizations, assumptions, and biases, and thus force students (and our colleagues) to question their understandings and beliefs.

Th inking about cosmopolitanism in this way, it’s surprisingly easy to make your class more cosmopolitan. Here are a few easy adjustments: