20 minute read

Language Teaching: Emergency Remote Teaching

Emergency Remote Teaching

A Whole New Ballgame

Advertisement

Compiled by Dr. David E. Shaffer

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, public schools and universities throughout Korea have been forced to move their classes from their traditional face-to-face classroom environment to an online platform. Th e quickness with which this changeover took place left precious little time for English teachers to prepare – to redesign lesson plans, to get acquainted with an unfamiliar learning management system and new apps. Was teacher–student interaction feasible? Was student–student interaction possible? How could student assessment be conducted? Th ese and many other questions, adjustments, and uncertainties seemed to present themselves all at once and needed to be promptly resolved. Th e present situation is so radically diff erent from regular online teaching that it has been christened “emergency remote teaching.” It is a whole new ballgame! Presented below are the experiences of four area English teachers – teachers at the primary, secondary, and university levels who are members of KOTESOL’s Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter – and their accounts of how they have dealt with emergency remote teaching.

Everything Takes Longer

Dr. Ian Moodie is an associate professor in the Department of English Education at Mokpo National University in Muan, just north of Mokpo. He has been teaching in Korea for 15 years and for the past three years has been teaching English education majors at MNU. Here is his account.

When I fi rst heard that we were going to teach online, I was relieved and not surprised. At that time, COVID-19 had already been deemed a global pandemic, many major universities had already switched to distance learning, and the major sports leagues of the world had suddenly shut down for the season, which made it clear to me that this virus was the real deal. However, that relief soon turned to uncertainty – and then to a mild frustration in realizing that everything I wanted to do was going to take a lot longer than I thought it would. Have you heard of Hofstadter’s Law? It goes something like this: Tasks always take 20 percent longer than you expect – even if you account for Hofstadter’s Law. I experience this everyday with online teaching.

At fi rst, I tried to match my online coursework and activities as closely as I could to my previous lectures. However, I soon felt that this was not the best approach and have since modifi ed the materials to better suit the medium. My courses (whether they be in pedagogy, English language, or linguistics) tend to involve a great deal of collaborative activities, but this has been harder to pull off online – harder for me to plan and harder for the students to complete. My students expressed a preference to be able to do the coursework at a time of their choosing and to not have to login at specifi c times for lectures or to do activities. Th us, my classes now involve mostly asynchronous learning, and I have had to accept that while this is not an ideal approach for effi cacious language teaching and teacher training, it is a pragmatic approach to get through the semester.

Th ere are some positive things arising from this experience, too. For one, being forced to cede to online instruction, I now have a deeper understanding of how to make use of blended learning in the future. I also feel that this experience will give stakeholders a renewed appreciation for the role that schools, universities, and learning institutes provide to our communities. Moreover, this experience has been a good reminder of the need to accept things how they are as opposed to how we wish them to be.

Th e Missing Feedback Loop

Brennand Kennedy teaches undergraduates at Dongshin University in Naju, just south of Gwangju. He has been teaching in Korea for six years and for two years at Dongshin. Here is his account.

addition to keeping my job while not risking the further spread of the virus, it also allowed me to be much more involved in my daughter’s birth and her first weeks of life. However, with no experience teaching online and a brand-new career preparation course to teach, I knew that I was in for a rough semester.

One major challenge has been student engagement (or lack thereof). Although I considered conducting live lectures through video conferencing software, most teachers in my department have had to settle for uploading pre-recorded lectures along with the university-mandated 35 minutes of coursework per lesson. Initially, in hopes of retaining some semblance of real-time student interaction in what are supposed to be conversation courses, I naively asked students to adhere to the originally scheduled lecture times when participating in the video lectures. However, after two weeks of trying to enforce this rule, it occurred to me that some of my students might be lacking easy access to computers and/or the internet, and may even be venturing out to internet cafes just to participate in my lectures, thus defeating the purpose of the online courses. Although we live in what is often called the most connected country in the world, my hopes for some type of normalcy during such an unprecedented crisis turned out to be unreasonable, and I have since been giving students the entire week to (virtually) attend my lectures.

This initial oversight points to the more general challenge of interacting with students in an online setting. A large portion of what teachers do in the classroom occurs based on the real-time feedback we get from our students, whether it is the pace of instruction, the activities used, or the way we explain new language items. For me, online teaching has completely removed that feedback loop and the already hard work of understanding each student’s unique obstacles to language learning has become effectively impossible as few students are willing to communicate with me through any of the many available means. Sadly, after eight weeks there are only a handful of students whose names I have come to recognize. Where I used to be a coach for my students, online teaching has made me into a police officer, constantly monitoring to ensure that students are watching every video and completing every survey, quiz, and forum that I poured so many hours of work into creating. While I appreciate all new experiences, my students and I are hoping this experience will soon meet its permanent end.

Focusing on What ICanDo

Lisa Casaus teaches fifth- and sixth-grade students at Unli Elementary School in Gwangju. She has been teaching in Korea for four years and has spent most of that time at her present school. Here is her account. The nature of my job, as a public elementary school guest teacher, is full of limitations. Officially, I am an assistant to a Korean English teacher. This means that the definition of my role can vary greatly based on my partnering teachers: their needs, wants, and teaching style. Other limits include the barriers of language, age, and culture, not to mention concerns about safety, that are present when teaching young learners.

EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers have developed ways to work with or around language and culture, but now, as we face the added limitation of a twodimensional teaching space, our old solutions may no longer work. Our old activities may not be appropriate. It is time to create and innovate.

As an artist as well as an EFL teacher, creation and innovation are my favorite aspects of this job. But I often suffer from “idea-overwhelm.” Too much possibility can sometimes be worse than not enough. So, when applications like Powtoon, Mentimeter, Kahoot, and Flipgrid kindle my inner illustrator’s heart, I dream of interactive presentations, animated web-comics, and class blogs where elementary students engage each other in English! Possible? Probable? Probably not. I have to remember that reality and aspirations do not always match. What is realistic in this environment? What is realistic for myself and my students? Instead of focusing on what I cannot do, I need to focus on what I can do.

What I can do is search for and organize videos, worksheets, and online games that are relevant to the lesson being taught. I can modify and repurpose, or if need be, create from scratch. This is similar to what I have been doing before, only now I am not thinking about how to develop collaborative, tactile, and kinesthetic activities. Instead, my focus is on the audio-visual realm: thinking of ways to explain how to do an activity without the immediate benefit of body language, eliciting techniques, or comprehension checking.

I can learn how to make interactive worksheets and explainer videos. I can focus on what I am good at by illustrating Baby Onion video-stories. Baby Onion, my personal mascot, is a character who features in many of my lessons. Half of my students are already familiar with the character and his friends. I can create Baby Onion material – for hours and hours and hours. And, I can remind myself that even though I love to create these materials, I also have to

Luckily, I Heard About BAND

Bryan Hale is a teacher at Yeongam High School in Yeongam, south of Gwangju, and the fi rst vicepresident of KOTESOL. He has been teaching in Korea for eight years, two years at his present school. Here is his account.

When talk fi rst went around about the Korean school year beginning online, I worried that English conversation classes might be cancelled altogether or that authentic communication could be impossible. Th is fear seemed justifi ed when I started hearing about the learning management systems being considered and how focused they were on one-way delivery of content like video lectures.

Even the more interactive possibilities seemed to have big drawbacks. I teach at a rural high school, and I worried that something like Zoom might not be accessible to students with less technology. And I knew that many more students would feel uncomfortable videoconferencing with family members around.

Luckily, I heard about Naver’s BAND. Previously, I had thought this was only a phone messaging app, but I was happy to discover that it off ers many of the communication features of social networking services in a private space with good accessibility for both phones and desktops. I campaigned to use BAND for my English conversation lessons, and fortunately, my school agreed.

Teaching live, synchronous lessons in a text-based chatroom has involved some challenges! It is tricky not being able to gauge students’ facial expressions and body language, but we have been using a lot of emoji and reactions, and I think we have established some new communication norms.

One of the benefi ts of text-based chat interaction is that it gives students more opportunity to focus on language, since the language they “listen” to does not disappear into the air, and they can be more thoughtful and deliberate about their output. At the 2018 KOTESOL International Conference, I saw a fantastic session by Jill Hadfi eld in which she spoke about creating online language activities similar to the kinds of interactions people naturally engage with on the internet, and that really guided my planning about how to teach using BAND. Jill Hadfi eld and Lindsay Clandfi eld have a book called Online Interaction, and you can fi nd some great videos of them explaining their ideas on YouTube. As we move back to classroom teaching, I would like to establish blended learning by maintaining some of these benefi cial aspects of online interaction using BAND.

Takeaways

Th ough teaching online may fi rst give the impression that the instructor would have more free time, Ian conveys how online class preparation takes longer than expected – even longer than expected with extra time already factored in! He also points out the futility in trying to construct online learning to mirror in-person classes. Brennand highlights the challenge that fostering student engagement presents in an online environment and the lack of interaction, which leads to the absence of feedback on and from students.

Lisa stresses the need to create and innovate for online instruction, that is, the need to not focus on what cannot be done with online instruction but on what new possibilities the new medium presents. Bryan is thrilled to have found BAND, the text-based chatroom that is the closest thing yet to simulating face-to-face discussion, and the use of emoji to convey body language.

Being parachuted into unknown territory can be distressful, but aft er landing and surveying the new terrain, one can identify the direction in which to proceed to best accomplish their mission – in this case, emergency remote teaching. Photographs courtesy ofIan Mo o die, Brennand Kenne dy, Lisa Casaus, and Bryan Hale.

GWANGJU-JEONNAM KOTESOL UPCOMING EVENTS

Check the chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and online activities.

For full event details:

The editor

David Shaff er has been a resident of Gwangju and professor at Chosun University for many years. He has been with KOTESOL since its early days and is a past president of the organization. At present, as vicepresident of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, he invites you to participate in the teacher development workshops at their regular meetings (presently online). Dr. Shaff er is currently the chairman of the board at the Gwangju International Center as well as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.

Oi Naengguk

Cucumber Soup

Written by Joe Wabe

The dog days of summer are here! Luckily this beautiful country has many delightful and healthy ways to keep us cool. Koreans have understood for centuries that what you eat will make a diff erence in beating extreme weather conditions.

Th e heavier the meal, the greater thermic eff ect of food on our body, so keeping it “light” in summer means keeping ourselves cooler!

A big percentage of our bodily fl uids come from foods that contain good amounts of water, like veggies and fruits. But the list does not stop there. According to traditional Chinese medicine, there are certain foods that contain cooling properties and can balance the energy of the body: Oysters, chicken eggs, yogurt, lotus root, turmeric, and seaweed are some examples.

Cucumber soup (오이냉국, oi naengguk) is a classic summer side dish in Korea, and a type of naengguk (chilled soup) that is mainly eaten in summer. It contains elements that help keep the thermic eff ect at low levels and make your body feel comfortable and chilled.

Combining cucumbers and seaweed in a chilled sweetand-sour dish produces a fresh, crispy, and cool eff ect on your palate that is regenerative and will keep your body feeling healthy throughout midsummer – best of all, it will take you only a few minutes to put it together.

The Author

Joe Wabe is a Gwangju expat, who has been contributing to the GIC and the Gwangju News for more than ten years with his work in photography and writing. INGREDIENTS (Serves 4) 1 medium-sized cucumber 1 cup of seaweed (soaked) 1 sweet red pepper (chopped) 1 cup of minced garlic 1/2 medium-sized onion (chopped) 3 tablespoons of vinegar 1 tablespoon of sugar 2 tablespoons of soy sauce 2 tablespoons of sesame seeds 4 cups of water 2 tablespoons of water 1/2 teaspoon of salt

PREPARATION

Cut the cucumber at an angle into ovals, then julienne the pieces a few at a time. Next, chop the onions into thin slices. Prepare the seaweed by soaking it for about 15 minutes, then rinse and drain well. Remove all the excess water by squeezing it tightly. In a medium-sized bowl, add the seaweed, cucumbers, and the rest of the ingredients (except the water) and toss it gently. Finally, add the water and refrigerate for at least one hour before serving. You can add a couple of ice cubes for a cooler eff ect.

Spanish in South Korea

A Language of New Opportunities

Written by José Avila Peltroche and Elisabet Ramirez

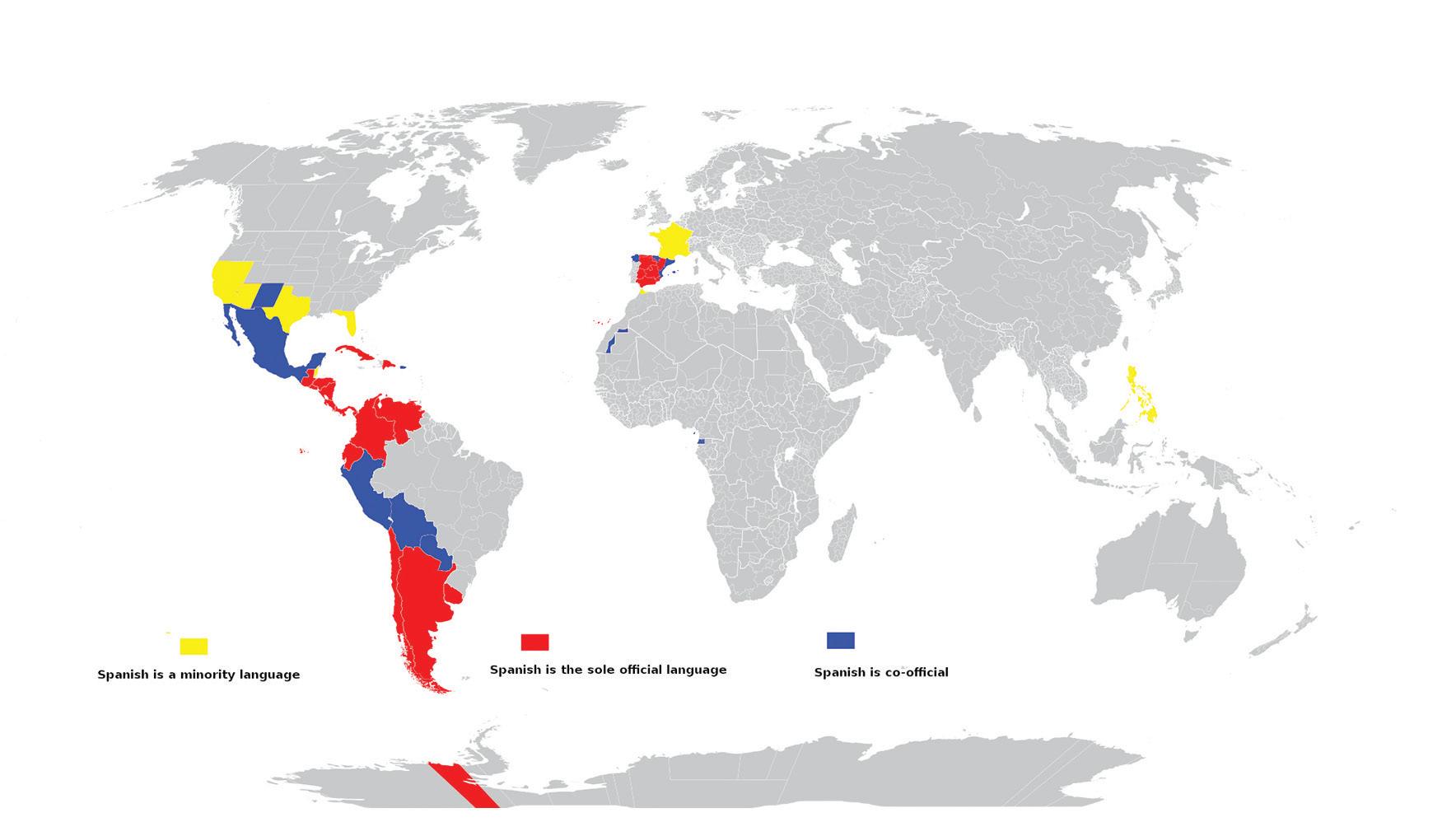

World map showing areas where Spanish is official or co-official, and where Spanish is not official but spoken by minorities. (https://commons. wikimedia.org /wiki/File:Spanish_language_World_Map.svg)

Spanish, also called Castilian due to its origin in the Spanish Kingdom of Castile, is a romance language from the Iberian Peninsula. More than 577 million people around the world (7.6 percent of the world’s population) speak Spanish as a first or second language. By the number of native speakers, it is the second most spoken language worldwide after Mandarin Chinese. Spanish is one of the six official languages of the United Nations (UN) and also of some other important politicaleconomic organizations (e.g., the European Union and the Antarctic Treaty System). Spanish is also the third most used language on the internet. Like other romance languages, it is a modern continuation of the “colloquial Latin” (also called “vulgar Latin”) that started diversifying in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. It diverged from other variants of Latin after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE.

To date, Spanish is the romance language that has achieved the highest diffusion across the globe, thanks to its propagation during the Spanish colonization period (15th–19th centuries), especially in the Americas. [1]

Spanish has also strongly influenced some creole languages. For instance, Chavacano (or Chabacano) is a Spanish-based creole language spoken in the Philippines, which itself presents variations depending on the area where it is spoken. Another good example is Palenquero, spoken primarily in the village of San Basilio de Palenque in northern Colombia. [2] One of the oldest Spanish loanwords in the Korean language is tabaco (“tobacco” in English). It entered the Korean Peninsula during the Japanese invasions in the 16th century. This word experienced many phonetic changes during the following centuries, and nowadays, it is pronounced dambae (담배). [3] Despite this old record, Spanish teaching in South Korea just started 72 years ago. In April 1948, Dongyang Institute for Foreign Languages was founded, and it originally taught six languages: English, French, German, Chinese, Russian, and for the first time, Spanish. However, this project was thwarted due to the Korean War (1950–1953). It was not until 1955 when the first department of Spanish language, at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, was inaugurated.

According to the Korean Ministry of Education, in 2005, the number of people learning Spanish in South Korea was approximately 15,000. There are currently 30 universities where Spanish is taught as a second language, 14 of which have their own Department of Spanish Language and Literature. Also, 41 high school institutes offer it as an optional subject, and four high schools as a mandatory subject. [4] Interestingly, South Korea is the country in Asia having the highest number of students enrolled in the Diplomas de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE; English: Diplomas of Spanish as a Foreign Language) exam. The DELE is a world-recognized certificate of proficiency and fluency in Spanish. In 2010, more than 2,000 Korean students decided to take the DELE exam, 70 percent of them being women. [4]

Nowadays, Spanish is the most required Western language in South Korea aft er English. Th e popularity of Spanish in the country can be refl ected in several aspects. With the expansion of South Korean companies around the world, such as Samsung and LG, having Spanish-speaking personnel gives them a competitive advantage in expanding their markets to places like Latin America. In fact, every summer, Seoul hosts the Latin American Festival, where music, dances, foods, along with other cultural expressions from countries in this region, are presented. An interesting example of how Spanish can connect places geographically distant from South Korea can be found in K-pop music. During the last few years, Korean bands have made collaborations with Latin artists and have included Spanish phrases in their songs. Th is is an eff ort to connect better with their fans in Spanish-speaking countries, which represent an important percentage of their sales. [5] Spanish words have also been used for naming products from diff erent industries: LG called its new kimchi refrigerator dios (“God” in English), and Hyundai used tiburón (“shark” in English) for naming one of its sport car models. [3]

In Gwangju, Spanish is taught at some institutions. Chosun University is the only one having its own Department of Spanish Studies in the Jeollanam-do area. [4] Th e Gwangju International Center also off ers Spanish classes to Gwangju citizens and expats. Despite the importance of this formal education while learning Spanish, informal activities, such as talking with nativespeaker friends and acquaintances, are crucial to becoming fl uent. [6] In this sense, the Gwangju Spanish Club was created in 2013 by Douglas Baumwoll, a US expat who learned Spanish in the Canary Islands (Spain), to bring native and non-native Spanish speakers together.

Since 2019, twice a month the Gwangju International Center has hosted the Spanish Language Exchange organized by the Gwangju Spanish Club. Th e exchange has gathered people from countries like Mexico, Peru,

Spain, Bolivia, Ecuador, the USA, Colombia, Haiti, the Philippines, and of course, South Korea. It off ers a friendly place for practicing Spanish regardless of a person’s level, and it helps the Gwangju community connect with the diff erent cultural backgrounds that Spanish-speaking countries have.

In summary, Spanish is still a young language in South Korea and is mostly spoken by minorities in this country. However, its expansion during the past seven decades has been extraordinary. Despite being still far behind other languages such as English and Chinese, the utility of Spanish in business and cultural exchanges attracts and will continue to attract more students of all ages. Spanish has become a door to new opportunities for Koreans to explore.

Sources

[1] Instituto Cervantes. (2018). 577 millones de personas hablan español, el 7,6 % de la población mundial. Cervantes Institute. https://www. cervantes.es/sobre_instituto_cervantes/prensa/2018/noticias/np_ presentacion-anuario.htm [2] Lipski, J. M. (2004). Las lenguas criollas de base hispana. Lexis:

Revista de lingüística y literatura, 28 (1/2), 461–508. [3] Segura, J. J., & Cabrera-Sánchez, J. (2011). El español en Corea del

Sur. El español en el mundo. Anuario 2010–2011. Cervantes Institute. https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/anuario/anuario_10-11/jimenez_ cabrera/p01.htm

[4]

Kwon, E. H. (2007). El español en Corea del Sur. Enciclopedia del español en el mundo. Anuario del Instituto Cervantes 2006-2007 (pp. 146–149). Instituto Cervantes. [5] Rivas, J. (2018). El creciente interés de Corea por aprender español.

K-magazine. https://www.k-magazinemx.com/el-creciente-interesde-corea-por-aprender-espanol/ [6] Mendoza-Puertas, J. D. (2018). La educación informal en el aprendizaje del español entre los universitarios de Corea del Sur.

Revista Internacional de Lenguas Extranjeras, 9, 55–75

The author

Elisabet Ramirez is an environmental engineer from Queretaro, Mexico. She is a Spanish teacher in Gwangju. José and Elisabet are in charge of the Spanish Language Exchanges at the Gwangju International Center. Instagram:@elielir

The author

Jose Avila Peltroche is a biologist from Lima, Peru. He is currently doing a PhD in seaweed biology at Chosun University in Gwangju. Instagram: @jocavi89