WORD COUNT: 6354 words

KEYWORDS: architecture, spatial, experience, game-space, real-space

ABSTRACT

Video games have become part and parcel of our present. An irrefutable staple in our culture in the advent of innovation between technology and storytelling. And as it flourishes as an industry, its gameplay spaces begin to look like spaces of reality; realism and immersion a goal that developers seem to always climb to, and over the years, have been doing so successfully. This metamorphosis sees reverberations in other fields of design – namely architecture, seeing the obscurity between Real-Space and Game-space as they feed into each other’s progress.

The question to be asked then emerges: can video games provide an improved perception of architectural space as an interactive medium?

By finding out if these developments of new typologies of space are viable as architectural experiences via comparison to reality and other mediums, as well as asking users if they are more effective as representations of space; the potential of reality and virtuality to coexist to the benefit of the designer is unraveled.

TUTORIAL: GAME-SPACE/REAL-SPACE

The experience of architecture has always been linked to imagery. Within virtual mediums, like books, film, drawings, and other visual media, we are unable to escape the familiar sight of our constructed spaces of reality regardless of genre. Yet despite the vividness of imagination, one finds the true embodiment of space –the phenomenology that surrounds its experience – to be lost in translation; the media too impersonal or too static to fully represent the journey.

Today, we face the development of the new typologies of space – spaces that emerge from the coexistence of the physical and the virtual, and the advancement of technology. Possessing both the audiovisual language of traditional virtual media and interactivity, video games establish a space in our modern world as a medium of entertainment, capable of linking the player to the spaces they visually encounter through control. They simulate the tangible. As architecture struggles to define ‘space’, virtual worlds obfuscate the already blurred lines of its definition.

Its capability as an interactive medium begs to be investigated beyond its purpose of entertainment; its analogous relation to reality shows the potential to be explored as an architectural space. Therefore, this dissertation aims to examine if these new typologies make more effective spatial experiences as representations of space – not to replace reality, but as an added method of experience – and what this means for the future of design.

The examination first defines Game-space and Realspace under spatial theories to ascertain video game space as viable architectural spaces and as a typology, after which the parallels of phenomenology between both is drawn and the variety of Game-space as a spatial experience is outlined. Two levels of Game-space comparison, using specific game environments, then establish the limits and capabilities between mediums: the first level studies Game-space vs Real-space under the lenses of realism, scale, immersion, dynamism, and spatial narrative, and the second studies Game-space vs other representations of space under realism, scale, immersion, spatial narrative, and level of perception. The examination is further compounded by results of questionnaires between gamers and non-gamers regarding game-space experience.

There has always been a difficulty in defining architecture due to its indefinite spatial nature. Initial theories on architectural space defines the physical enclosure and the separation of the interior from the exterior as an essential aspect of space (Semper, Mallgrave and Robinson, 2004). PostKantian aesthetic theories establish space as a property of mind (Schmarsow, August, 1894). Space, within New Space theories, is also a practiced place; the experience in relation to the positioning of environmental objects (Certeau, 1984). What can be seen as the most comprehensive of theories was put forward by philosopher Henri Lefebvre in his introduction to the Triad of Space, with which he weaves the three aspects – volume, ideation, and experience – with the social implications of space.

In Real-space, there consists of the perceived (spatial practice), conceived (abstract thought) and lived (bodily experience) – the real, the imaginary, and the symbolic. To Lefebvre, production of space on the perceived level takes place as an everyday spatial practice, in which space is performed and individually perceived: the phenomenology of space. Production of space on the conceived level are both ‘representation of space’ and logical ideations: this describes the epistemology of space. Production on the lived level takes place as the constitution of ‘representational spaces’ which are culturally significant places (Lefebvre and NicholsonSmith, 2013). The conceived and lived spaces stand in a triadic relationship to the perceived and are relevant to the examination of the medium of games as they, even in their earlier forms, have always been concerned with space.

The oldest board game in the world – Senet (c. 3500 BCE)–consisted of a board of 30 squares in three rows of 10, and two players that competed to move their pieces across the playing space to the end of the board. Text-based game Oregon Trail (1971) brought players from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City with the task of ensuring their wagon’s survival by inputting decisions to hunt, purchase supplies, and deal with hostile conditions in relation to this imagined space. Simulated table-tennis game Pong (1972), where the gameplay merely required vertical control over an in-game paddle, existed in a two-dimensional space. Now, as games evolve into 3D realms, the complexity of the Game-space becomes almost parallel to Real-space.

While it is precarious to compare Game-space against the Triad of Space – being a typology that Lefebvre did not expect – it, as a theory, is more encompassing of the what of Game-space. Though lacking in the physicality of space, it contains the perceived; the use of Game-space via individual routines formed through gameplay. It was conceived through thorough ideation and rule-making by game designers, and through experiences driven by narrative, gameplay, and even player-to-player interactions, become lived spaces. However, it is the kind of rules that conceive Game-space that differentiate it from Real-space. Espen Aarseth defines Game-space as an allegorical representation of space; games can never depict space as it is perceived, in its totality, as it is in real life, as the representation is always serving the primary purpose of gameplay, and its mathematical and coding rules differ from the social and physical rules of reality (Aarseth, 2001). However, video game spaces have become more ambitious and varied in their own typologies to merely define it as a spatial allegory. Its increasing interactivity and parallels to Real-space can place it as an exemplification of spatial concepts, denoting symmetrical representations of space theory (Günzel, 2019)– which in and of itself can be presented as a new typology of space.

Spatial experience, often reduced to the rational entities of numbers and rules, is to be considered together with its environment in architectural phenomenology, the human being a complete entity with his environment – the relation of body, sensation, and meaning (Pallasmaa, 2012). For this, phenomenology aims to create spaces that are based on experiences and to address the senses, often through the manipulation of space, material, and light and shadow.

Both the spatiotemporal experience of space in Real-space and the spatiotemporal experience of Game-space have a close relationship. The Game-space, as exemplifying spatial concepts, relies on phenomenology. Spatial qualities such as navigation, interaction, and exploration must play with multiple sizes of space, interior-exterior dynamics, while remaining effectually complex at the same time, to facilitate player freedom and movement. It must be designed, constructed, narrated, and filled with interaction — much like how architects attempt to anticipate how their occupants will interact and exist with architecture. It must establish narrative space through world-building – much like the architectonic concept of the built environment explaining themselves through the paths travelled in them (Calleja, 2011).

It is according to the gaming typology and therefore the type of player that would be interacting with the space that the dynamics are tailored – single player games tend to have more narrative-driven spaces than online multiplayers; open-world games will have larger scale maps than shooters or sports simulators – and along which the user interface is also designed. Narrative-driven games may opt to forgo with intricate HUDs to deliver more cinematic experiences, making navigation and interaction with the space more intuitive through materiality or lighting, which then also serve to build

narrative alongside immersive environmental sound-design. Detail in environmental design differs to perception level or the player perspective, as well. Games viewed from the topdown like most strategy games will be more concerned about the urban/building-scale detail, first-person perspectives with detail at the human-scale, and third-person falling somewhere in between.

This variety, perhaps, is what the basic video game holds superior over VR: there is a flexibility in the type of spatial experience that can be delivered. The designer is not constrained to designing around the spontaneous firstperson perspective. The user is also not obligated to spend both space and greater financial expense as they would have to with VR equipment merely to experience a designed Gamespace. Of course, it is all dependent on user preference, as well as whether the content itself will be enhanced with the hardware or hindered. Regardless of hardware choice, games have the capability of being perceived through different eyes as the player embodies the experiences of a specific character or navigates fantastical spaces unfamiliar to them. Elements of gameplay and environmental design woven together well is what Game-space relies on to execute immersion within their narrative space. Similar to Real-space phenomenology, Gamespace phenomenology is the relation of player, sensation, and meaning.

Video games that emphasize on realism are known to use real architectural elements or backgrounds to create the natural connection of Real-space and Game-space within the player, representing a spatiotemporal part of Real-space, or several as is the case with Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series.

“History is our playground,” the series tagline says, as it uses different historical time periods as a setting for their games, often showcasing years of historical research with closeto-accurate depictions of their Real-space counterparts.

These semi-open worlds use historical playgrounds in telling the narrative of a fictional millennia-old struggle between Assassins and Templars over differing ideologies regarding the achievement of peace, following individual historical Assassins throughout time, intertwined with real-world historical events and figures in a sci-fi, historical fiction package. As such, it becomes a representation of space within a spatial typology, as these playgrounds become lived experiences that would otherwise be experienced from behind the glass of a museum display.

The French Revolution was depicted in Assassin’s Creed Unity (Ubisoft Montreal, 2014), giving a third-person perspective on the turbulent streets of 18th century Paris. The Gamespace was built as true to the city as it had existed in 1789, with changes only for gameplay’s sake – the level designers prioritising the player experience with building a game playground first, before making a historically striking and accurate depiction of Revolutionary Paris (Webster, 2019)

Open world games place importance on urban design as a way of benefiting the gameplay required for their mechanics. Assassin’s Creed placing the narrative upon the character avatar through giving specific missions that can be completed in a variety of ways using the urban landscape to their advantage; the games are well known for their unique parkour system, gaming mechanics allowing the scaling and running across the rooftops of these sprawling depictions of

historical cities. Creating an urban city such as Paris required deep historical research, pouring over hundreds of maps of the city to determine the city layout and the key aspects that needed to be changed – similar to an architect’s site analysis. The density of Real-space Paris conflicted with the games’ free-roaming movement, and so the designers had opted for a “radial scale” process: the centre of the city with is a oneto-one recreation, while the further you move from the core, the more outspread each structure becomes (Webster, 2019). While the Parisian Gamespace was a compressed enactment of the Realspace – a mere 2.4 sqkm against 105.4 sqkm, as was the limits of game development technology at its time –its careful design enabled a one-to-one enactment of Paris’ essence.

The level of detail in their historical depiction proceeds onto building scale. The Notre-Dame in the Gamespace was worked on by designers, texture artists, architects, and historians to ensure historical authenticity. Historical photos and architects were consulted for accuracy in form, down to the stained glass of its rose windows; texture artists made

sure each brick was as it had been in 1789; and historians had aided in pinpointing the exact paintings that would have been hanging on its walls (Webster, 2019). What had taken 182 years to build was constructed in virtual space within three years of the game’s development.

Detail extends also to a human scale. Walking the streets of Paris leads the player avatar to bump into crowds of peasants stumbling through the muddy streets or rioting outside palaces. Walking into those palaces greets the player with striking renditions of bourgeoisie opulence from the Rococo ceiling frescos to the marble flooring, with virtual AI-operated nobles loitering in their powdered wigs within the salons.

These spaces are also somewhat dynamic, shifting and changing with the weather, with the progression of the narrative and the protagonist’s actions as they run through

tides of historical time, witnessing the build-up of a revolution. This is enhanced through realistic graphical presentation and a dynamic soundscape – heavy foot traffic and conversations in French while navigating streets, birdsong, commotion to subtle humming from passersby, Gregorian chants nearing churches, cannon fire in the distance from the brewing uprising layered upon each other to reflect 18th century Paris. Controls, especially if one plays on a console platform, are also made heavier as to reflect the weight of the avatar’s movement, an embodiment of a character within the player’s hands.

However, where the level of detail astonishes, it falls short of in certain aspects of realism: not all characters in the Gamespace are able to be socially interacted with, save for key narrative and gameplay figures (eg. Merchants, mission givers, Napoleon Bonaparte) and yet only to the extent of what the narrative allows the avatar to do. Realism in Game-space can only go as far as the life within it is coded to be, as far as it is technologically capable of going. These crowds in the streets do nothing more than follow routine coded into them and offer news around the narrative or the historical context. Games like Assassin’s Creed use civilians as set dressing, and so complex human behaviour is never a concern beyond what is needed for gameplay, and even so, the spontaneity of human behaviour can never be coded. So, it begins the unravelling of the limits of realistic Gamespace – it cannot truly replicate the freedom and complexity of reality, at least as of today, regardless of detail.

Surrealistic Game-spaces, by their very nature, rely on suspension of disbelief to deliver a believable spatial narrative. They are an exploration of narrative interpretation and function as entertaining gameplay level design. As such, realism does not necessarily apply to these types of Gamespaces so much as world-building – the context of the surrealism. These surrealist spaces then are heavily bound to its creations of conceived space to be resulting lived spacesthese spatial explorations of concepts for the pure experience of the emotional capabilities of architectural space. As is said in the Manifestoes of Surrealism: “(…) Surrealism aims quite simply at the total recovery of our psychic force by a means which is nothing other than the dizzying descent into ourselves, the systematic illumination of hidden places and the progressive darkening of other places.” (Breton and Breton, 1972)

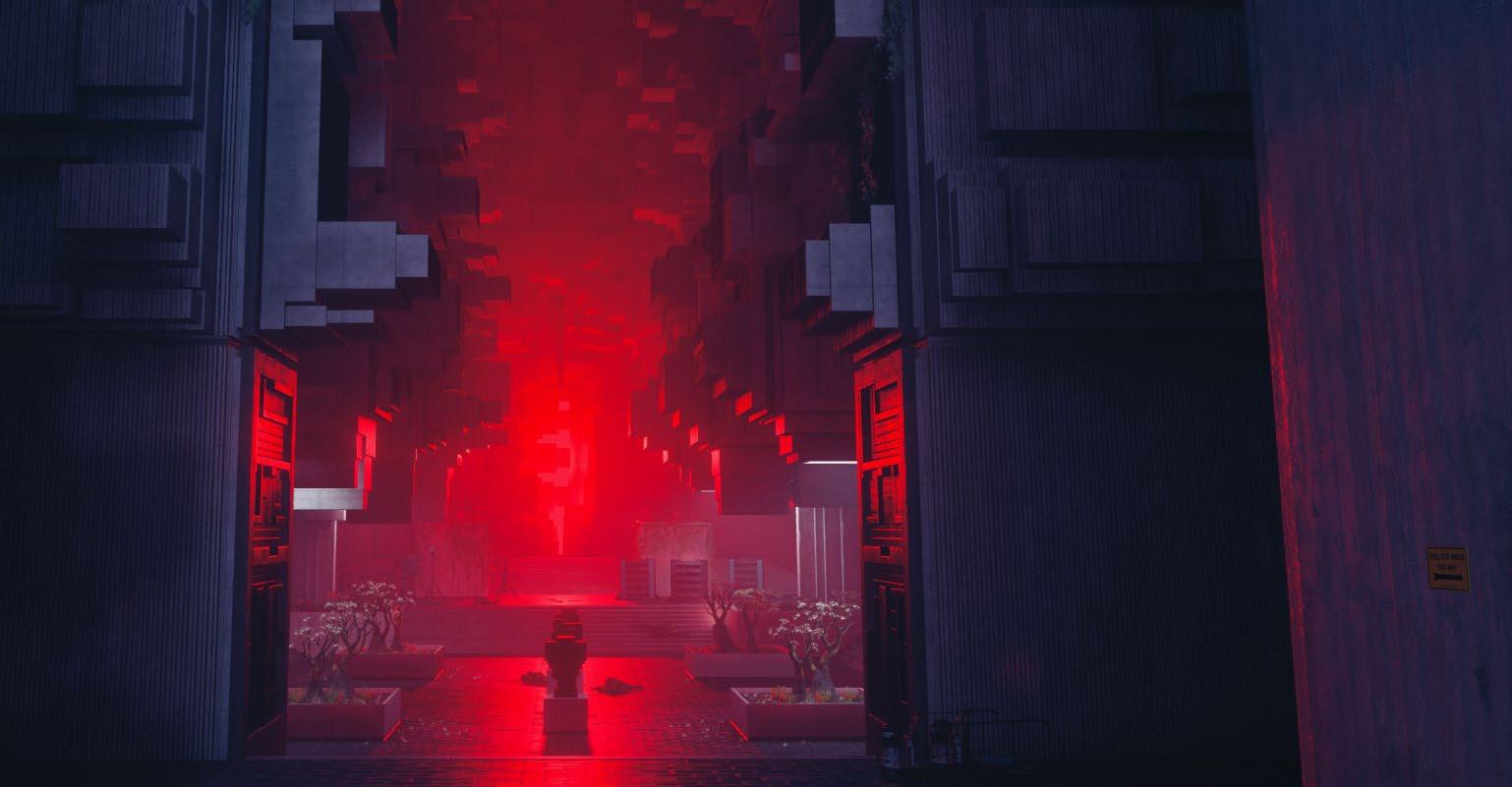

Control (Remedy Entertainment, 2019), a third-person actionadventure, has its entire runtime take place within the Oldest

House, a vast government building (dubbed Bureau of Control) being invaded by a paranormal entity. The House was heavily inspired by Long Lines, a towering Brutalist structure in the city of Manhattan, theorised to be an NSA mass surveillance hub (Wilson, 2019). While the origins of Brutalism were quite humble in its relation to large public works, social housing, and government buildings – a medium of the people, massive concrete structures have become symbols of dystopia in modern media. The game designers were aware of this as they made the Oldest House; and while set in a relatively lessvaried, smaller scale environment in comparison to Assassin’s Creed Unity, the scale of the setting feels expansive in the game’s mechanic of reactive space.

Concrete of the walls were made stark and bare. Lifeless. It balances the aspect of the game’s mechanic of destruction, the player character a disruption to the Gamespace – it acts as a canvas as the space becomes reactive to avatar’s actions. Hovering and slamming to the ground forms impact craters, bullets leave scars and dust, chunks of the walls can be ripped and thrown across the space. Materiality in Control, though limited in variety, gives way to interactivity as the player shapes the space through their combat encounters.

The design of each level was shaped by the concept of ritualism. The House’s in-game function was bureaucracy, and so it maintains a mundane austerity in its rooms that reflected repetitive office lives. However, its scale and symmetry give the feeling of the uncanny as supernatural forces pervade the Gamespace. Geometries of the space repeat in a fashion similar to designs by Carlos Scarpa.

Walls shift in these office spaces and vast halls as the building engages in its own ritual. The shapes repeat, growing inwards. The building is in control of the player’s reality. This surrealistic, impossible architecture functions as a both something that furthers the game’s overarching themes of oppression and the unknown, but also as game design elements that allow the player avatar to zip and float around

the Gamespace in their own act of supernatural destruction while offering a challenge to gameplay (Wilson, 2019). The concept of dynamic spaces in the detail and scale as The Oldest House depicts can only ever be conceived within the imagination of an architect.

Buildings like AT&T Long Lines were not meant to be for human life. Long Lines itself is a hulk of stepped massing, extruded volume made from precast concrete panels clad with flametreated granite faces that can withstand nuclear fallout. Each of the 29 floors is double the height of any office building at 6 metres, with the tenth and the twenty-ninth floors having large, protruding ventilation openings. It’s the safest building in the world, made self-sufficient for 1,500 people to survive inside its walls for two weeks, with water and food for the occupants and 250,000 gallons of fuel to power generators; and its grided floor plates house machines – few people have ever been inside. It is lifeless. Unfeeling. Existing without regard to human scale, like a monolith, much like The Oldest House.

The impracticality of space is what Gamespace can explore, unconstrained by the rules of reality, yet still connecting to Real-space by its need to stimulate the senses through phenomenology. As it simulates an experience within a space of something as uninhabitable as Longlines, it balances the senses by giving an element of life - the harsh surfaces of concrete awash with atmospheric light. While serving as set dressing, it offered a subconscious connection to the gratifying elements of Real-space architecture, making its habitation more believable, more immersive in its experience as a space as it balances the mundane and the strange.

It should be noted that the representation of fantastical architectural forms, detached from function and decoupled of real-world realism, transferred to virtual mediums to symbolise, build up atmosphere and portray narrative, are not new. As art is constructed within space, space is often reflected back to our senses through movies to literature, creating playgrounds of utopian possibilities relative to Realspace.

A medium that is perhaps the most closely connected to the architectural discipline, a medium as old as man, and having been used to represent architecture since it had begun, is illustration. Architectural designs have always been conceived through the drafting of several drawings to be brought to the constructed spaces of reality, but plenty have been left as mere visionary architecture – as there are no unbuildable buildings, only unbuilt ones – much like Hugh Ferriss’ Metropolis of Tomorrow (2005).

60 drawings accompanied by written commentary, divided into three sections. The first illustrates the “Cities of Today” as they were in mid-century United States, the second discusses “Projected Trends” in relation to urban design that he supports as well as opposes, and the final section illustrates “An Imaginary City” in what Ferriss sees as an ideal future of Real-space.

All illustrations within the book are prints of his monochromatic charcoal renderings, dedications to New York’s modernist skyscrapers as the vision of the futuristic city. The skyscraper is a constant throughout his versions of the city; a strong belief in superscaled geometric monoliths as a must in the future of a city, in equally geometric civic plans, in hierarchy according to functionality. There is a difference to visions of architects today, but regardless, his was a vision that many illustrators, architects and set-designers were influenced by (Davidson, 2017), and of which several cities that were at a point seen as the global metropolis – Dubai, Tokyo, New York (‘Global city’, 2021) – closely resemble. Ferriss understood the impression that cities leave on the city dweller. It is shown in his depiction of modern utopia through light and shadow, perspective, and scale, almost gothic in its dramaticism. These impressions are eventually what inspires the aesthetic art direction of Bioshock (2K Boston, 2007) for its fictional underwater Game-space: Rapture.

Rapture was born from the dreams of Andrew Ryan, the game’s main antagonist, as a paradise free of religious and

government interference of any kind, where any citizen could prosper for his or her own gain with only the values of ambition, scientific reason, and free thought to guide its citizens in their pursuit of achievement. It models as a purely capitalistic society running on Randian Objectivism, which while utopian in its purpose, led to becoming a breeding ground for sociopolitical and economic unrest that causes its downfall.

Rapture in its height of prosperity was designed as a reflection of its in-game time-period: a 1950s Art-Deco metropolis with a silhouette that greatly mirrors Ferriss’ illustrations. Gold plated towers and bright neon light up the depths of the Atlantic. Interiors continue the gleam and glamour of the city: grand spaces adorned with heavy sculptures and velvet, expert craftsmanship in every geometric form and line, and furniture with sweeping, elongated curves with metallic finishes. Colourful posters of propaganda and commercial adverts reflect the confidence of a capitalistic utopia. ArtDeco as a theme is chosen well as a visual telling of the city’s faith in economic and technological progress to result in opulence.

Though not all of Rapture is free to explore in the Game-space – Bioshock being a more linear narrative game, therefore only allowing a set path for the player to experience Rapture – the scale of the city can be seen as game levels offer otherworldly first-person views through glass of the aquatic metropolis, aquatic life weaving across gleaming structures with muffled whale song.

There is a suspension of disbelief needed with the amount of glass used in a city underwater; but regardless, there remains a perception of a working city, a believability in the amount of thought the concept of an underwater city like Rapture had gone through. Details of its construction are littered around the city in audio diaries or exhibitions; an intriguing system consisting of a giant submersible platform anchored at the bottom, deep sea welders and mechanics, pilings and girders, and prefabricated aluminum buildings assembled near the surface, lowered using lunette rings and anchored onto the foundations making up the metropolis.

As a functioning city, systems and technology are shown as experiences in the player’s journey through Rapture. The player enters Rapture via a bathysphere from the surface, a real historical submersible, and connects to the rest of the city through the Atlantic Express train, the Rapture equivalent of a metro. Power generation is shown in one of the levels as the Hephaestus Power Facility. It consists of exposed conduits and enormous pipes and gears that make use of geothermal vents on the ocean floor. Minerva’s Den serves as the brain of Rapture, the central computing system that maintains the entire city’s functionality. The hundreds of businesses and services within the city that the player character slinks through and interacts with combine to make a sense of a working economy.

Rapture, as an interactive metropolis within Gamespace, remains an ambitious and memorable fictional setting within the gaming medium (Kim, 2016). Even beyond its ambition within its in-game universe, there was an ambition in creating a setting that proved itself a powerful concept, alike in more ways than one with Ferriss. To that end, there is a potential in Gamespace in the creation of conceptual utopias, dystopias, the balance of both, the general idea of extraordinary architectural concepts like Atlantis and Castles in the Sky, that submerge the user/player in its well-thoughtout systems and make them possible despite reality saying otherwise.

Therefore, it is a possibility, in the exploration of these Game-space concepts, that Virtual Metropolises of the Future will be conceived, and the future of design forever will be changed.

Yet another genre that envisions, or rather, projects the future of the urban city is the Dystopian Cyberpunk. The theme enforces a future of technological and scientific advancement, like the rise of artificial intelligence and cybernetic augmentation, and a capitalistic hedonism that leads to a society of the marginalised consumer against megacorps against the seedy underground.

In neo-noir classic Blade Runner (Scott, 1982), synthetic humans called ‘replicants’ were engineered for labour in space colonies. Replicants are illegal on Earth, and if set foot on our land, will be hunted down. Set in a 2019 dystopian Los Angeles, Rick Deckard is a ‘blade runner’ – a replicant hunter – and is tasked with tracking a rogue group to be permanently terminated. Deckard’s hunt throughout the city is portrayed in breath-taking frames of flying cars, decrepit apartment buildings and pyramidal corporate headquarters, the darkness of the city mostly illuminated by neon signs and animated billboards. There is the iconic cyberpunk fusion of east and west cultural imagery as a sign of rising polycultures.

Buildings lining the streets look like a literal accumulation of their history, as they retrofitted new MEP systems or new facades on top of the old structure, a city with a broken consumer base that no longer benefits from the capital. The streets themselves have become congested left-over spaces as the city rises in height, the rich and technocratic living above the common, creating a city that has lost its human scale. The city is dense and overpopulated and art director Syd Mead shows these overly lived spaces through visual clutter (Lightman, 2020) – eventually becoming a staple in the visual aesthetics of cyberpunk culture.

The genre over the years has become a niche trend in popular media, shifting and changing in accordance with what the time visualises as the future. CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) visualises the future in the form of Night City –an independent city-state located on the border of California as 21st century multicultural megalopolis. Prior to its release, the game had gathered a significant amount of anticipation, and with good reason: CD Projekt, a well-reputed gaming development company, had set an ambitious goal of a fully fleshed, explorable open-world that brings the likes of cult classic Blade Runner to life in the player’s hands.

For the most part, Cyberpunk 2077 had achieved its goal. Night City is a lively setting with its own rich socioeconomic history. It all can be learned via radio, surrounding conversations, in-

game internet, and an in-game codex. The map is large and dense – totalling up to 43.5 sqm, almost half the size of the capital of Senegal, in addition to a partially explorable vertical axis – with complex streets and shortcuts that can be quickly traversed with a variety of vehicles at the player character’s disposal. The city itself has character; divided between six districts, with interiors and exteriors that differ in style between them, and the districts differ in their age, socioeconomic standard, terrain, and function. The architectural styles are a believable mess of classic Modernism to striking postmodern to industrial Metabolist. The player character, as a mercenary, resides in one of the more run-down regions called Watson, in an apartment that is reminiscent of gigantic social housing project.

The manner in which the city is populated serves its genre well. In true cyberpunk fashion, Night Citizens show to

be a dehumanising society, and the city is rampant with gun violence, corporate warfare, hypersexuality, class discrimination, hedonistic escapism, and an obsession with consumerism. As it is a world that encourages body augmentation, citizens of all shapes, sizes, ethnicities and temperaments walk the streets, and media is all inclusive with announcements in eastern and western languages. The Game-space is thematically based on freedom, and it carries over to gameplay in letting the player have autonomy of choice, from character customisation to narrative direction and gameplay style.

As it is, the world-building within Night City is one of its key strengths. Its decidedly more colourful spin on the gritty Los Angeles of Blade Runner is a sensory marvel, sound design and visual detail not in any way lacking as you experience it in your first-person view. However, this effort of immersion and style falls apart once technological shortcomings prevent players from experiencing this space to its fullest potential. Cyberpunk 2077 had become known as a failure at launch (MacDonald, 2020). The anticipated title became synonymous with disappointment from unfinished code, missing gameplay features, and unexplained game crashes. Bizarre glitches impeded players from exploring what would have been a realistic depiction of a cyberpunk themed Game-space – an elevated experience from the beautiful cinematography of Blade Runner. Where ambition had prospered, the potential of Night City falls apart as it shows yet another limit to the Game-space experience. It goes to show ambition and scale does not equal a successful Game-space.

Video games are made via an intensely complicated development process involving hundreds of artists, programmers and animators working together on a gigantic, rapidly updating program. While not so different from any other design discipline, the game development industry has been plagued with problems of time crunches and corporate pressure, and just like other disciplines, a design can only be as good as how it was made. The Game-space experience, while capable of much immersion, is fickle; it takes something as simple as a glitch to ruin what would be the height of a sensation and shatter the illusion of an engaging space.

Perception of space can vary between person to person, and to avoid the risk of comparing representational mediums based solely on personal standpoints, data from several other users were gathered regarding the effectivity of video games as spatial experiences and as emerging spatial typologies.

Two user groups were sent out questionnaires: gamers, as a control group, and non-gamers, as a general public perspective. All respondents from both user groups fit the 19-26 age range. The game type chosen for evaluation is the open-world category, due to the games being more exploration based and the free-roaming being closer to reallife behaviours, with variety in forms of space experienced in one greater Game-space world.

Gamer user group consisted of 9 respondents, all of whom play video games consistently or are extremely familiar with the medium. Three were in the field of Architecture and six of whom were in other STEM fields.

Initial questions tested existing user disposition on a quantitative scale of 1-5. Gamers were asked their frequency of open-world gaming; whether they are immersive; and if narrative, gameplay, environment detail, scale and realism were factors to their immersion in games. The respondents all had a varied response to frequency, 22% of players not playing open-world genres as frequently as the rest, but all unanimously scoring it high on the immersion scale. Narrative, detail and scale ranked high on the factors contributing to immersion, with gameplay scoring mostly neutral, and realism scoring mostly low.

They were then asked to evaluate a specific game title and scale several factors affecting experience of the game. User-friendliness/efficiency, gameplay, environment design, narrative, sound design, and graphics were scaled against the level of immersion. The games listed varied in genres of fantasy, sci-fi, action-adventure as well as various platforms. Gameplay, environment design, narrative and sound design scaled high for all games; ease/efficiency and graphics had mixed responses, but did not seem to affect immersion as all games scaled high.

The Non-gamer user group had 5 respondents – the criteria having been users who have had limited experience with gaming, and had consisted of users within Architecture, Education Studies and Psychology fields. The non-gamers were personally sat down to play Assassin’s Creed Unity, the game chosen as having the most factors of experiential comparison due to being modelled after a real location. The game was played in a controlled environment, after which the questionnaire was given to answer afterwards.

Initial questions evaluated prior experiences regarding mediums on the same quantitative scale. 80% of the respondents have played video games, and all have at some point been exposed to the medium. Video games, film/TV, and book were rated according to immersion – games scored highest, film and TV scoring a close second, and books receiving more mixed responses. In addition to medium, general factors of realism and narrative were also scaled. Narrative was a high contributor to immersion, with realism receiving a more mixed response.

Assassin’s Creed Unity was then evaluated similarly to the Gamer user group’s factors: user-friendliness/efficiency, gameplay, environment design, narrative, sound design, and graphics scaled against immersion. The game had been fairly easy to play; environment design, narrative, sound design, graphics scoring very high alongside a highly immersive experience with the game. The only factor to differ from the Gamer user group was gameplay not being much of a factor considered for immersion.

Both user groups were then asked open questions regarding the emotions felt in the Game-space, memorable aspects, and whether video games are an effective way of experiencing space. The answers are similar across both user groups. Emotions are largely driven by the space represented; awe at beautiful sights, excitement and thrill at exploration. Memorable aspects can differ among users, between wellwritten stories, free roam and traversal aspects, scale and attention to detail, ambient design and music, visual design among others.

When it comes to effective means of spatial experience it had generally been a resounding yes if compared to film or photography. Non-gamers had additionally suggested the use of VR kits to increase realistic experience, but regardless they unanimously would be willing to experience the Gamespace again without it.

One gamer is quoted as having written:

However, they brought up a point regarding the effective perception of space, arguing that any typology, for effective spatial experience, will be dependent on the quality of its interactions.

Ultimately, what the results show is the capability of Gamespace to be perceived as architectural experiences, to both gamers and non-gamers. Its ability to interact and explicitly inject narrative and audiovisual design facilitates immersion in a well-designed environment, which can in turn create the optimum means by which space can be perceived.

“Videogames allow atmosphere of space by letting the player interact with a well-executed environment and ambience. Because I can meaningfully interact with and explore the space freely I get a better idea of what it feels like to be in that space. Games can also play with music and colour palette changes to demonstrate atmosphere. If that is done appropriately, the game is the most effective means of experience.”

“What allows for space to be perceived is the amount of interactivity within said space.”

Architecture, in its all-encompassing nature, has become a test of the masterful combination of narrative and design, and technology its proving ground to provide the best of spatial experience. As Gamespace evolves to be bigger and better since its conception, even separate to the realms of VR, it demonstrates clear aptitude in such provisions beyond its interactivity. An aspect of what makes Gamespace thrive is its ability to simply be as a fictional space, using the freedom of virtual space to make the more impossible architectural concepts possible to experience, while also being capable of replicating many spaces of reality. Of course, it would be dependent on the execution and the quality of its interactivity within, but similar things can be said of any project, as such is the nature of design.

Therefore, the use and implementation of Game-space in the built environment would be advantageous to the designer. Game-space learns and takes from Real-space, so too can Real-space with Gamespace. If not to include within the Real-space design process itself via simulation, then to create as an extension of Real-space. Game-space can bridge the gap of user and experience.

But the designer can take it beyond this. The designer can create architecture solely for Game-space – where fantastical images can truly flourish. Not to replace reality, but to let architecture evolve purely from creativity and freedom of imagination, unbound by realism, but still shared as an experience amongst users as they see into the designer’s mind as the experience was intended. As architecture continues to concern itself with the best of spatial experience, the truest spatial experience can reach new heights as people embrace the obfuscation of reality and virtuality. Game-space can provide for the people the future of our built environment.

2K Boston (2007) Bioshock [[digital download] PC]. California: 2K Games (Bioshock).

Aarseth, E. (2001) ‘Allegories of Space’. doi:10.1007/978-37643-8415-9_13.

Abbott, C. (2007) ‘Cyberpunk Cities: Science Fiction Meets Urban Theory’, Journal of Planning Education and Research - J PLAN EDUC RES, 27. doi:10.1177/0739456X07305795.

Adams, E. (2003) ‘The Construction of Ludic Space.’, in.

Blackford, R. (2004) ‘Reading the Ruined Cities’, Science Fiction Studies. Edited by S. Heuser, 31(2). Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4241258 (Accessed: 24 December 2021).

Borries, F. von, Walz, S.P. and Böttger, M. (2007) Space time play: computer games, architecture and urbanism, the next level. Bäsel: Birkhauser Verlag.

Breton, A. and Breton, A. (1972) Manifestoes of surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press (Ann Arbor paperbacks, 182).

Brouchoud, J. (no date) ‘The Importance of Architecture in Video Games and Virtual Worlds | Arch Virtual VR Training and Simulation for Education and Enterprise’. Available at: https://archvirtual.com/2013/02/09/the-importanceof-architecture-in-video-games-and-virtual-worlds/ (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

Calleja, G. (2011) In-game: from immersion to incorporation. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

CD Projekt Red (2020) Cyberpunk 2077 [[digital download] PC]. Warsaw: CD Projekt.

Certeau, M. de (1984) The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Davidson, J. (2017) An Interactive History of 42nd Street’s Dramatic Transformation Over 164 Years, Intelligencer. Available at: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2017/04/ nyc-walking-tour-of-42nd-street.html (Accessed: 11 December 2021).

Dwiar, R. (2017) ‘The genius of Rapture’, Eurogamer, 21 August. Available at: https://www.eurogamer.net/ articles/2017-08-21-the-genius-of-rapture (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

Ferriss, H. (2005) The metropolis of tomorrow. Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications.

Gerber, A. and Götz, U. (eds) (2019) Architectonics of game spaces: the spatial logic of the virtual and its meaning for

the real. Bielefeld: transcript (Architecture, Volume 50).

‘Global city’ (2021) Wikipedia. Available at: https:// en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Global_ city&oldid=1060001022 (Accessed: 11 December 2021).

Goodman, N. (20) Languages of art: an approach to a theory of symbols. 2. ed., [Nachdr.]. Indianapolis, Ind.: Hackett.

Günzel, S. (2019) ‘The Lived Space of Computer Games’, in, pp. 167–182. doi:10.14361/9783839448021-012.

Here’s How Big Cyberpunk 2077’s Map Is (Measured) (2021) Twinfinite. Available at: https://twinfinite.net/2021/01/ heres-how-big-cyberpunk-2077s-map-is-measured/ (Accessed: 22 December 2021).

Irrational Games (2013) Bioshock Infinite: Burial at Sea [[digital download] PC]. 2K Games (Bioshock).

Kim, M. (2016) There Will Never Be a Place Like ’BioShock’s Rapture, Inverse. Available at: https://www.inverse.com/ article/20978-bioshock-collection-rapture-love-letter (Accessed: 11 December 2021).

Kirci, N. and Soltani, S. (2019) ‘Phenomenology and space in architecture: experience, sensation and meaning’, International Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology, 6(1), pp. 1–6. doi:10.15377/2409-9821.2019.06.1.

Lefebvre, H. and Nicholson-Smith, D. (2013) The production of space. 33. print. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Lightman, H. (2020) Discussing the Set Design of Blade Runner, American Cinematographer. Available at: https://ascmag.com/articles/blade-runner-set-design (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

MacDonald, K. (2020) ‘Cyberpunk 2077: how 2020’s biggest video game launch turned into a shambles’, The Guardian, 18 December. Available at: https://www.theguardian. com/games/2020/dec/18/cyberpunk-2077-how-2020sbiggest-video-game-launch-turned-into-a-shambles (Accessed: 22 December 2021).

Night City: how Cyberpunk 2077’s future megacity was built (no date) Domus. Available at: https://www.domusweb.it/ en/architecture/gallery/2020/12/21/night-city-how-thecyberpunk-2077s-megalopolis-was-built.html (Accessed: 22 December 2021).

One Year Later, Cyberpunk 2077 Is Still a Massive Disappointment (2021) Twinfinite. Available at: https:// twinfinite.net/2021/12/one-year-later-cyberpunk2077-is-still-a-massive-disappointment/ (Accessed: 22 December 2021).

Pallasmaa, J. (2012) The eyes of the skin: architecture and the senses. 3. ed. Chichester: Wiley.

Remedy Entertainment (2019) Control [[digital download] Xbox One]. Milan: 505 Games.

Schmarsow, August (1894) Das Wesen der architektonischen Schöpfung: Antrittsvorlesung, gehalten in der Aula der K. Universität Leipzig am 8. November 1893. Leipzig: NN. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.49891.

Scott, R. (1982) Blade Runner. Warner Brothers.

Semper, G., Mallgrave, H.F. and Robinson, M. (2004) Style in the technical and tectonic arts, or, Practical aesthetics. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute (Texts & documents).

Stouhi, D. (2020) From Backdrop to Spotlight: The Significance of Architecture in Video Game Design | ArchDaily, Archdaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/938307/from-backdrop-to-spotlight-thesignificance-of-architecture-in-video-game-design (Accessed: 25 November 2021).

The Cyberpunk 2077 Hype Is Just Too Much (no date) Kotaku. Available at: https://kotaku.com/the-cyberpunk2077-hype-is-just-too-much-1845808091 (Accessed: 22 December 2021).

‘The Metropolis of Tomorrow’ (2021) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_ Metropolis_of_Tomorrow&oldid=1015195187 (Accessed: 21 December 2021).

Ubisoft Montreal (2014) Assassin’s Creed Unity [[CD] Xbox One]. Montreuil: Ubisoft (Assassin’s Creed).

Webster, A. (2019) Building a better Paris in Assassin’s Creed Unity, The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge. com/2014/10/31/7132587/assassins-creed-unity-paris (Accessed: 15 October 2021).

Wilson, E. (2019a) ‘Remedy’s Control is built on concrete foundations’, Eurogamer, 3 September. Available at: https:// www.eurogamer.net/articles/2019-09-03-remedyscontrol-is-built-on-concrete-foundations (Accessed: 15 November 2021).

Wilson, E. (2019b) ‘The impossible architecture of video games’, Eurogamer, 12 February. Available at: https://www. eurogamer.net/articles/2019-02-12-the-impossiblearchitecture-of-video-games (Accessed: 15 November 2021).