6 minute read

How Gerrymandering Inhibits Civil Rights Progression

Stella Liu, Year 11, Keller

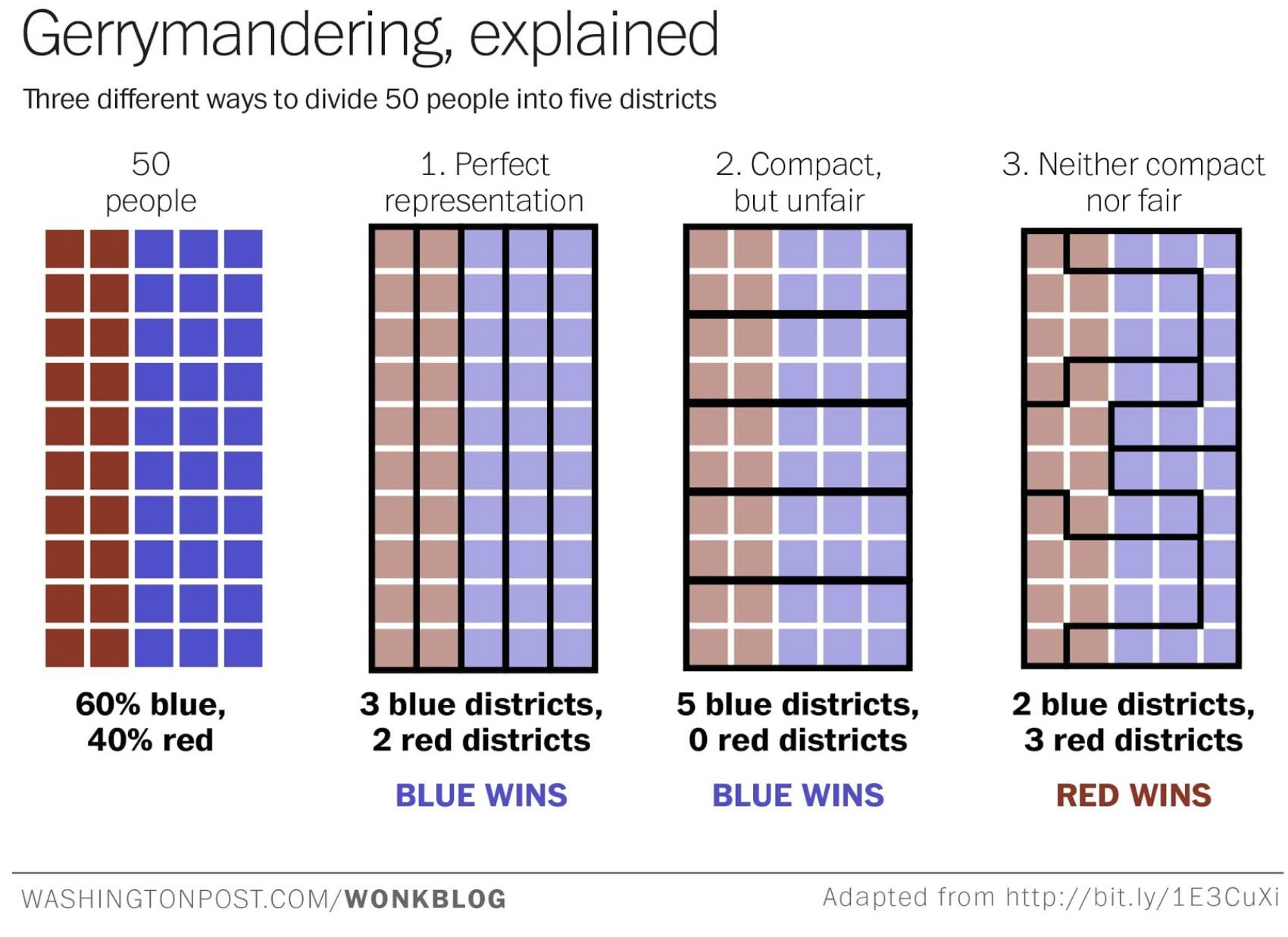

Every ten years, the United States collects census data about its population and demographics. States use the data to redraw their electoral districts; these district boundaries determine which congressmen the state elects to represent them on Capitol Hill, essentially giving state legislatures the ability to “pick the voters”. This was how Republican political strategist and gerrymandering mastermind Thomas Hoffeler described the process of gerrymandering. Diagram explaining examples of “cracking” and “packing” Gerrymandering is the manipulation of the boundaries of an electoral constituency so as to favour one party or class. Similarly, in the electoral college, when a citizen votes, they are in fact voting for an electoral college instead of their preferred candidate. Since varying methods are used to choose the candidates of the electoral college, there may be an uneven distribution of electors in either the Democratic or Republican Party depending on the specific state. A well-known consequence of this was in the 2016 election where Hilary Clinton lost to Donald Trump, even though she received 2,900,000 more votes than the latter. tests for Black constituents with a fairer national test, the proportion of Black voters in Southern states such as Mississippi dramatically increased from 6.7% to 67.5% of the state’s voting population. Section 4 of the Act banned the unjustifiable literacy tests, which included requests (according to the civil rights movement website) such as “In the space below,”“draw three circles, one inside the other.” Another question was “Write right from the left to the right as you see it spelled here.”, demonstrating again the fact that these questions really had no logical link to how qualified a voter is to vote. Section 5 outlawed discriminatory voting practices by preventing vote dilution, which involved nullifying the minority vote. It also required 9 states and certain areas of 7 other states with a history of racial discrimination in voting to seek approval from the federal government before making changes to voting laws. It didn’t take long, however, for Southern politicians to find a legal loophole. They realized that while it had become nearly impossible to limit black voters’ access to the ballot box, it was still possible to curtail the power of the votes they cast. In the years immediately following the enactment of the Voting Rights Act, a growing number of Southern jurisdictions replaced geographic districts with at-large voting (designating members of a governing body who are elected or appointed to represent the district and its citizens). It eliminated elected positions in favour of appointed ones (that reflected less of the demographics of the area) and reconfigured state legislative districts (gerrymandering) — all in an effort to reduce the effect of the newly surging Black vote and to maintain White

supremacy.

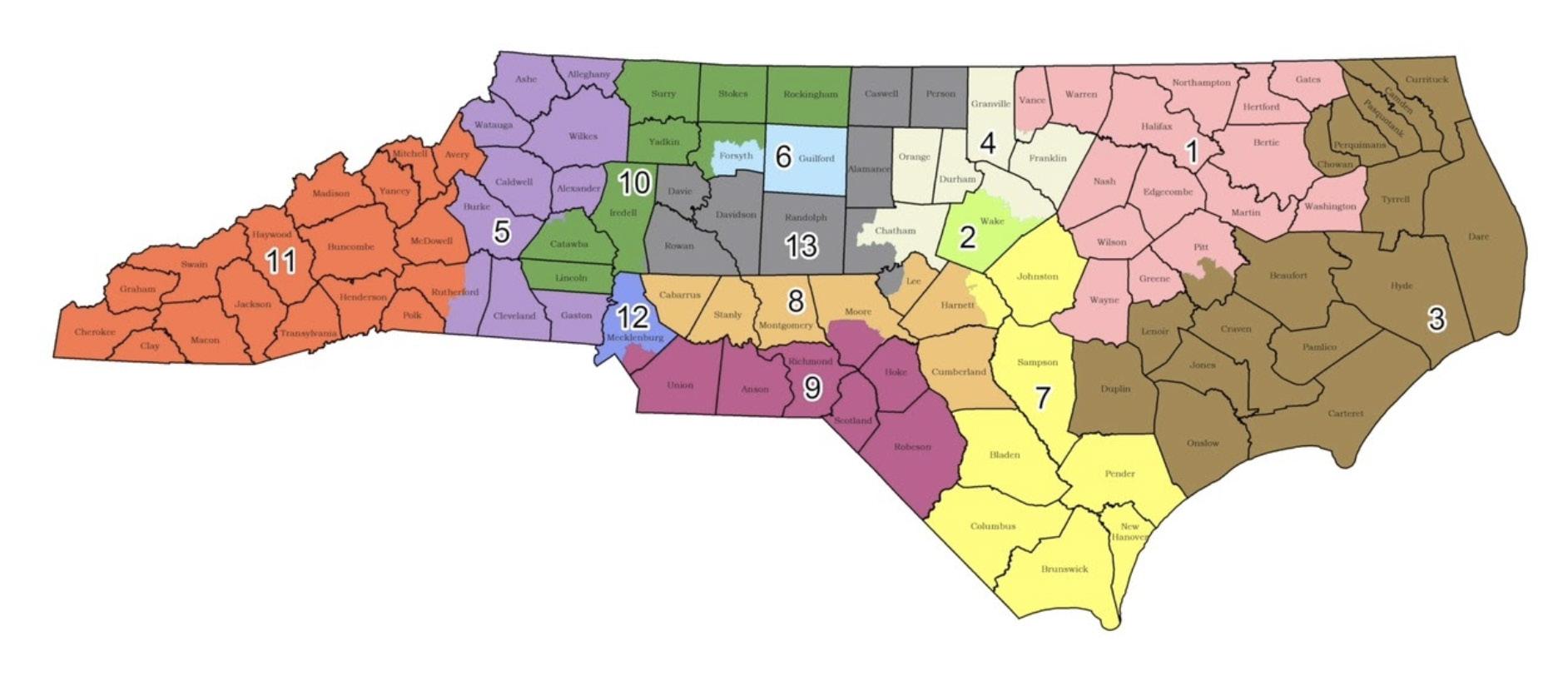

In the present day, the most notable case of racial gerrymandering can be found in North Carolina, where Thomas Hofelller famously created his masterpiece in 2011. District 12 can be seen cutting through 5 other districts in order to limit the power of Black voters in the state and to help his Republican Party win as many congressional seats as possible; all the while, his maps were proven to use racial statistics. Moreover in 2019, Jowei Chan who is a professor at the University of Michigan testified that he had used the formula “%18_ap_blk” (which shows the number of African American citizens of voting age in each district) to affect the shape of the North Carolina map. His ‘masterpiece’ involved, firstly, identifying areas in Winston-Salem, Greensboro and Charlotte that were most dominated by Black communities (it is important to note that each of these three cities of North Carolina almost have enough people for their own congressional seat). North Carolina’s congressional map divided the cities between three districts that all lean Republican by including outlying areas of mostly white and Republican voters. A congressional district that included two of the three cities would be competitive for Democrats. As a result, in the 2011 election for the House of Representatives, the Democrats received 51% of the vote but only 46% of the seats were given. The same effect of gerrymandering can be seen in the election for senate where Democrats received 50% of the vote but were only given 42% of the seats.

Map of North Carolina’s Congressional Districts in 2011

Map of North Carolina’s Congressional Districts in 2020

Hoefeller’s gerrymandering resulted in the Republican-led state of North Carolina passing many controversial laws in the following years, including the HB2 law in 2016 which banned local laws that protected LGBTQ+ people from discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. The law also prohibited transgender people from using bathrooms and locker rooms aligning with their gender identity in schools and government buildings. Furthermore, in 2013 the General Assembly voted to repeal the entire Racial Justice Act, which prohibited seeking or imposing the death penalty on the basis of race. Since this law signified tremendous civil rights progression in a former confederate state, its repeal meant that the many years of fighting for civil rights in North Carolina was gratuitous.

Nevertheless, all of the backward momentum is constitutional. The courts struggled to define and standardize the criteria for deeming cases of redistricting as illegal, only being able to rule a few extreme cases as unconstitutional. Recently in 2019, however, in the Rucho v. Common Cause, a three-judge district court struck down North Carolina’s 2016 congressional map, ruling that the plaintiffs had standing to challenge it and that the map was the product of partisan gerrymandering (favouring one political side’s interests). The Supreme Court, in support of the district court’s ruling, ultimately decided that partisan gerrymandering was a non-justiciable political question that could be dealt with by state courts instead of involving federal courts. Following Rucho v. Common Cause, the Republican-led North Carolina government was forced to redraw its map without looking at racial and partisan data, resulting in a version that is much less biased and untouched by gerrymandering. Subsequently, the repeal to the Racial Justice Act in North Carolina was ruled unconstitutional in 2020.

To conclude, the practice of gerrymandering, racial or partisan, not only undermines the democracy that the United States prides itself on, but it also undermines the progress made in the Civil Rights Movement and the legacy of influential figures such as Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks and W.E.B Du Bois. In addition, it diminishes the historical, symbolic, and political significance of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The United States will never be a true democracy if the power that comes with each voter does not hold equal weight: progress in civil rights will be inhibited if this is the case. Unless states seek independent commissions for voters to directly choose their representatives, the effects of gerrymandering could potentially be far-reaching and detrimental to many.