40 minute read

Southern Stumpin

By David Abbott • Managing Editor • Ph. 334-834-1170 • Fax: 334-834-4525 • E-mail: david@hattonbrown.com

When First Is Worst

Icome from Alabama, so I know a thing or two about being number one…I know, I know, I’m sounding like THAT fan, but bear with me a minute. Alabama (this applies to the college football team, the country music band, and the state) has been #1, or close to it, their fair share of times…but not always in good ways.

In music, Alabama the band has had a lot of #1 hits and other top 10 songs, gold records, and industry accolades. In sports, the University of Alabama’s various athletics programs, but particularly its football team, have won a few championships, and come close to winning more, both in the old days under the iconic Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and more recently under the new GOAT, Nick Saban. And, of course, we do have another major college, Auburn University, which has also done quite well more often than not, including playing in, and winning, some SEC Championship and BCS national title games in the last decade or so. There was a stretch of a few years there, from 2009-2012, when the college football national championship winner every one of those years was either Alabama or Auburn, and Auburn was in the national championship game again in 2013, nearly extending the streak to five consecutive years. I have no doubt both schools will continue to see success. So, that’s when it’s good to be #1.

But in a lot of other categories, Alabama as a state has unfortunately often come in #1, or close to it, where we don’t want to be. In the minus column for our state: arguably, just about everything else besides sports and music. Yep, football aside, we’re used to being #1, or close to it, in a lot of other categories, relative to population size: obesity, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, infant mortality, violent crime, adult illiteracy, divorce, adultery, drug addiction, poverty; and often near to dead last (or first worst) in things like high school and college graduation rates, life expectancy, median income. In too many categories, we find ourselves at the top of the bad lists and the bottom of the good lists. A few years ago I read that the city of Montgomery can lay claim to having more STDs per capita than any other town in the U.S. That’s when being #1 is not so good!

And I don’t mean to be so hard on my home state; I’m just using those broad negative stats to make a point. There are plenty of good things here too, besides football: beautiful countryside, hunting and fishing, beautiful beaches, some mighty fine logging, and plenty of really nice people. We also tend to have lower unemployment rates, lower property taxes, and a generally lower cost of living that offsets the generally lower income levels quite a bit, so that in many places the actual quality of life, to the extent it can be measured objectively, is higher than the raw data might suggest.

Danger Zone

Logging is also #1 in a lot of ways—hey it’s #1 in our hearts, for sure. It’s a fine and honorable profession, one that performs a necessary service to society and the economy, and it’s filled with some of the best people you’ll ever meet. It’s generally unappreciated by much of the society that benefits from its labors. And it also consistently ranks as #1—on the list of the most dangerous jobs in America.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, there were 5,250 fatal work injuries across all sectors—all industries combined—in 2018. That number increased by 2% to 5,333 in 2019. The national average, among all industries, is about 3.5 workrelated deaths per 100,000 workers.

According to a June 3, 2020 article in Business Insider, logging has a fatality rate of 97.6 jobcaused deaths per 100,000 workers. That is almost 28 times higher than the overall rate for all jobs combined. The second most dangerous job, professional fishing, apparently has 77.4 deaths per 100,000, so logging has a pretty big lead (20 more fatalities per 100,000).

I found this very surprising; I very rarely hear about loggers dying in the woods.

Many other jobs you might intuitively think of as being more dangerous are, statistically, not. Mining, for instance: 11 deaths per 100,000. Law enforcement: we all love our heroes and know they have a dangerous job, but it turns out that “police officer” (local, state and federal combined) ranks as the 16th most dangerous job in America, at 13.7 deaths per 100,000.

How about firefighters? That’s gotta be one of the most dangerous jobs, right? I would have thought so. Well I didn’t see that on the Business Insider list…maybe I overlooked it or maybe they included it under EMT/rescue workers, it wasn’t clear…so I looked up some numbers from the U.S. Fire Administration and FEMA. In 2019, there were 62 on-duty firefighter deaths in the U.S., out of 1,115,000 firefighters (33% career and 67% volunteer). That’s the lowest annual number since USFA started keeping track, and thank God for that. It’s a fatality rate of 5.56 deaths per 100,000…well below logging’s 97.6, assuming that figure is accurate. Farming and ranching comes in at #7 with 24.7 deaths per 100,000; truck driving at #6 with 26 deaths per 100K. And there are several other things on the list, compiled from Labor Bureau and OSHA statistics: electrician, roofer, pilot. A logger is more likely to die on the job than any of them. Heck, about the only thing deadlier than logging is COVID-19 (164 deaths per 100,000). And that’s not even counting non-fatal injuries. With luck, you could just be maimed or crippled.

If memory serves, I believe I remember reading at one time, a couple of years ago, that the fishing industry briefly overtook logging as the most dangerous job one year, but logging reclaimed the crown the very next year and has, I think, held it since.

So, yeah, it’s not always so great to be #1.

Improvements

On the other hand, I came across this in a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) report from 1995: “The National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities (NTOF) Surveillance System indicates that during the period 1980-89, nearly 6,400 U.S. workers died each year from traumatic injuries suffered in the workplace [NIOSH 1993a]. Over this 10-year period, an estimated 1,492 of these deaths occurred in the logging industry, where the average annual fatality rate is more than 23 times that for all U.S. workers (164 deaths per 100,000 workers compared with 7 per 100,000).”

So, both the overall numbers and the logging numbers were much higher 30-40 years ago. The absolute number of deaths overall was about 1,200 more per year (for everything combined) back then, and the rate was double what it is now. The logging fatality rate has come down by about 40%, from 164 deaths per 100K in the ’80s to about 98 in 2019. No doubt that’s due to a lot of factors. Logging has definitely become safer—more mechanized, fewer men on the ground, more use of safety equipment and greater awareness and education about risks— but it’s still dangerous work, so you guys be careful out there. Turns out you might be the toughest and bravest men (and women) in America. Now that part doesn’t surprise me at all. SLT

Rising Above

■ Samantha Bull determined to keep her husband’s logging business going after his death.

By David Abbott

FOUKE, Ark.

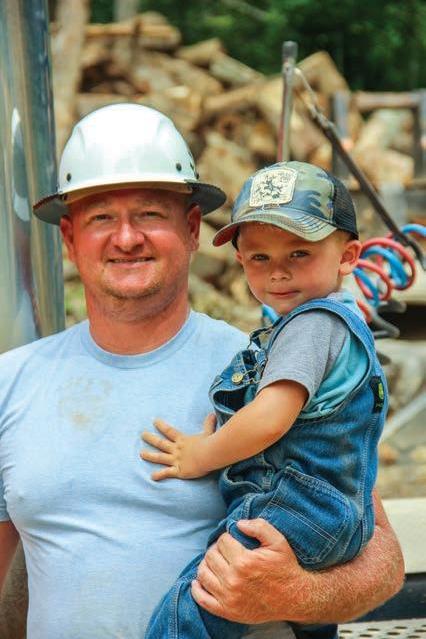

It could be the premise for a Hallmark movie. Eight years ago, Samantha Bull was a stay-at-home mom and housewife, happily married to her high school sweetheart, Michael, who supported his family with his logging company, Stanley Bull Jr. Logging (Michael was his middle name). They had two daughters, Josie, 11, and Leena, a newborn. Life wasn’t always easy, but it was good.

Then tragedy struck. In March of 2013, at age 37, Michael was diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma, an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A fast-growing cancer of immune cells in the blood, it is often rapidly fatal. Sadly, this turned out to be the case for Michael. He died in November that year. “It all happened very quickly,” Samantha says. “We were not really prepared for it at all.”

A widow at 33, she was left with the assets of a business she didn’t know much about. She had helped with the paperwork, but that was about it. Stanley Bull Jr. Logging had been a stable and profitable operation, but it wouldn’t run itself on autopilot. She had no other source of income—no college degree, no job experience. What she did have: two little girls to take care of and bills that weren’t going to pay themselves.

So, in the midst of her grief, this young, suddenly single mom had to make a choice. She could sell the business her husband started, settle its debts and look for a job that would pay enough and a daycare she could afford. Or, she could use what her husband left her and try to make a go of the logging company herself. “It was either get rid of it or try to make it work,” she knew. “So, I thought, what the heck, let’s just give it a try.”

Of course, making the decision to manage a logging business herself was just step one; actually doing it would be no easy task. “I was freaked out,” she admits. “I was scared. I didn’t know anything about what goes on out here in the woods.”

Looking back, she has wondered at times what made her do this. Part of it was certainly financial: the business was there, and could support her and the girls, if it succeeded. But in part, it was a way to honor the memory of her late husband and to preserve his legacy for his daughters. He grew up in logging, had worked in it the whole time they were married, since 2000. “Michael had a big passion for it. It was something he loved and I thought he would probably want me to at least try to keep it going.”

For various reasons, her lawyer advised her to change the company name, or rather to form a new company under a different name: Bull IV Logging LLC. She chose that name as a play-on-words with a double meaning; it signifies that Michael Bull was “for” logging, because he was passionate about it, but also because they were a family of four.

Left to right: Weyerhaeuser forester Gerald Wright, crew foreman Tad Ward and owner Samantha Bull

Help

Suffice to say, eight years later, Bull IV Logging is still going strong. Now 41, Samantha is proud of what she accomplished with a little grit and determination, but she’s also quick to point out that she didn’t do it entirely on her own.

When she took over, the businesswoman admits, “I was nervous about

it. You have to have a confidence in the people who are running the machines.” And she didn’t have that confidence; she believed the crew she had wouldn’t last. “It is hard to get good people who want to do anything,” she acknowledges, echoing a common frustration of logging business owners everywhere.

What she needed was a skilled and experienced foreman to stay on top of everything on the job site. In June 2014, she hired Tad Ward to fill that position. Ward, who grew up in logging, turned out to be just what the doctor ordered. He had known Mi chael but had not worked for him, and he had known Samantha for a long time. Her dad, Braden Jackson, had been a truck driver, and actually used to haul wood for Ward’s father, Doyal Ward. He knew what he was doing, and she knew she could trust him.

Tad turned out to be something more than just a foreman. They form ed a partnership: Samantha manages the financials, the “business” side of the business, while Ward runs a load er and supervises operations in the woods. The arrangement has been beneficial for both of them. “It works, and it’s been really good,” she says. “I truly do not believe my business would have flourished like it has to day without the help of Tad’s knowledge, drive and guidance along the way. I am forever grateful for him.”

Equipment

Stribling Equipment in Texar kana, Ark., supplies the Bull’s roster of John Deere machines, including three loaders—2011 and 2014 437Ds and a 2019 437E— one for filling trucks, and the others for delimbing, merchandizing and separating pulpwood from logs. With no local chip-n-saw market, they have fewer sorts. One of the loaders has a Rotobec grapple saw, making it easier to top stems, Tad says.

Two skidders, a ’17 748L and ’18 648L, keep the loaders busy, each usually pulling to one of the delimbing loaders. A 2018 643L does the bulk of felling, and they keep a 643K in reserve on site. Several other spare machines are parked at Samantha’s house, ready if needed. A ’16 Case 750K helps build and maintain roads.

The crew these days leaves Sa man tha feeling all kinds of confident.

“To have a good crew is essential to running a logging operation, and I feel like I have some of the best,” she says. “I am very thankful for their hard work, determination, dependability and teamwork. It plays a huge role in making my business run smoothly.”

Bryar Ward, Tad’s son, runs the 748L, with Blake Uncel on the smaller skidder. James Nowlin handles the cutter, while Shane Baker and Tad do most of the loading and delimbing. Bud "Pops" Bland, who is 82, mans the dozer, maintaining roads when it gets wet. He also keeps roads swept when needed, and handles BMP work.

Four Western Star trucks and two contractors haul with Viking plantation trailers. Samantha buys her trucks and trailers from Lonestar Truck Group on the Texas side of Texarkana.

The Bull crew uses three Deere loaders, one for keeping trucks loaded, the other two for sorting and merchandizing.

Left to right, James Nowlin, Blake Uncel, Bud “Pops” Bland, Bryar Ward, Shane Baker

Company truck drivers, from left: Ryan White, Jerry Edgar, Larry Buford

Maintenance

Machine operators track hours and change oil when needed, every 500 hours on the newer equipment and every 250 hours on the older stuff. Machines run on average about 40 hours a week, so they go about six to eight weeks between service jobs.

Major repairs go back to Stribling, and everything is still under warranty except for the two older loaders. One of those has 14,000

Stribling Equipment in Texarkana supplies all the crew's Deere machines.

hours on it and Tad says they haven’t had to do anything to it.

When it comes time to get new machines, Samantha isn’t too concerned with trade-in value. “That girl won’t trade nothing,” Tad laughs. At the yard, there is a truck for which somebody offered her a lot of money, but she wouldn't sell. It sits in the yard and they crank it every now and then and let it run to keep the batteries charged. She has her reason, and it’s a good one. “Mainly the stuff I have kept was what Michael had, and I just can’t get rid of it,” she explains.

Ark-La-Tex Land

Based near Texarkana close also to the Louisiana line, Bull IV Logging tackles tracts throughout that Ark-La-Tex corridor, in all three states. In March 2021, when Southern Loggin’ Times finally caught up with them—a meeting that had been planned a year earlier but delayed by coronavirus travel restrictions— Bull IV was working on Weyerhaeuser land in Bossier Parish, Louisiana, about an hour from their home base in Arkansas.

The 29-year-old pine stand is surrounded by private land and was part of Weyerhaeuser’s Willamette acquisition in 2002. It was a 40-acre job, or 35 acres when you count around the SMZs, according to Gerald Wright, a Weyerhaeuser harvest manager out of De Queen, Ark. who often works closely with Samantha and Tad. It was a clear-cut, with thinning allowed inside the blue lines that marked the streamside management zones. Not surprisingly, production here was light on pulpwood. “We run about eight loads of logs to every one load of pulpwood fiber,” Tad reckons.

Though it was warm enough in March, this was a winter tract, Wright says, one they had held back for the wet months. “Most of them in this area we will hold for winter ground because it’s real sandy and hilly and has a lot of iron ore and rock underneath,” he explains. Bull IV gets timber strictly through Weyerhaeuser. When conditions are dry, Wright might have them working in Lafayette County, Arkansas; when it’s wet, he puts them in areas like this one, and it’s been extremely wet in recent months. “Probably worse this year than it has been in the last two or three,” Wright says. “We had three snow events down here, and then it rained probably two feet since on top of that.”

Contract drivers Jimbo Clayton, left, and D.J. Clayton, right

Markets

“It’s really too far away for a lot of Weyerhaeuser’s internal mills,” Wright says of the tract. “So the logs here go to West Fraser in New Boston, Tex. Occasionally we will send some to PotlatchDeltic (in Waldo, Ark.), but normally not very much.”

The crew averages 75 loads a week, when they can keep all six trucks hauling. “But it is so hard to find drivers,” Tad laments. “If it wasn’t for the trucking, logging would be nice!” The problem, in his opinion: there’s just a lack of qualified drivers.

Progressive Insurance, Samantha says, runs potential drivers through

Left, Michael Bull; right, daughters Josie and Leena

their system before she’ll hire them. She explains, “They have to be over 30, with three years of driving experience, and if they have any kind of tickets, you can forget it, because it will shoot your rates up too high.” Right now, Bull IV pays $55,000 in total insurance each year for the four company rigs. Recently they were considering adding a certain driver, right up until their Progressive agent informed them that hiring him would double their premium: an additional $50,000 for just the one guy.

Is there anything drivers can do if they have had problems? “I guess about the only thing you can do is quit and find a different line of work,” Tad says. “Trucks are a real fine line as far as making money anyway, I don’t care who you haul for. Once you cross that line to where you are not making money, you can’t keep them running. We have had to lay several drivers off because of insurance costs.”

The other problem is finding a driver who is dependable, they add, one who will haul and who will take care of the truck. They do drug testing of drivers, going through a third party who does a random check every month, pulling certain drivers and not letting them know until the day of the test. “I’m real stern on drugs,” Tad says. “There’s not any place for it.” The company’s safety plan outlines a zero-tolerance drug policy.

Weyerhaeuser requires a safety plan of all its loggers and provides topics for training. To comply,

Bull IV has developed its own safety program. This includes at least one formal safety meeting a month, usually around a truck tailgate. “Since the Covid, now I show it to them one-on-one,” Tad says. Everyone uses CB to communicate in the woods, also a must with Weyerhaeuser. Everyone wears PPE (hard hats and high-visibility shirts are required), nobody works on the ground, and there are no chain saws on the job besides pole saws.

“Safety is first,” Samantha says.

“Everybody out here, just about, is family, and everyone out here is working for a reason, and I just want everybody to make it back home every day.”

Logging is more than ok around these parts right now, they agree enthusiastically. Despite all the tumult of 2020, Samantha says the only thing that really affected their work adversely was the snow this winter. “Markets have been real good,” Tad adds. Wright points out that lumber has hit record high prices. “They have been running the Dierks mill and I am sure New

Boston is the same way. They have been trying to just cut as much as they can, and we have been feeding them logs.”

The two girls are doing well, their mom reports; Josie is now 19 and Leena is 8. Lena is in second grade now and Josie is attending cosmetology school. They have no interest in taking part in the logging business, though.

The journey hasn’t been a walk in the park, and there’s always another battle to fight. But Samantha doesn’t back down. In 2018, five years after cancer took her husband, the disease came calling for her as well: breast cancer. She didn’t have to undergo chemotherapy, but she had a mastectomy and it has been clear since. “This girl right here is tough, let me tell you,” Tad says. After the mastectomy, he says, she went home the next day and wouldn’t even take the pain pills. “I am just proud to be in her life,” he says. SLT

Hammer Down

■ Brandon Brock counters 2020 market volatility with diversity and plans expansion.

By Patrick Dunning

MAYKING, Ky.

For Brandon Brock, 37, owner of BBrock Enterprises, LLC, 2020 was a head scratcher of a year. It was the “lucky” 13th year in the woods for Brock, and he was starting to figure out how to efficiently manage his company when the world came screeching to a halt with the dawn of the new decade. Temporary mill closures and strenuous quotas had the young logger scrambling further for timber and trying to weather the storm during the first months of the pandemic.

“We were just trying to survive,” he reflects a year later. “Our production was down about 60% in the middle of March. I just tried to

★ maintain and keep our workers on Brandon Brock was the 2019 Kentucky Forest Industries Assn. Logger of the Year.

Hardwood sawlogs have remained the company’s focus with 40 loads hauled weekly on average.

the payroll with some cash flow.”

Brock, like nearly every logger, felt the ripple effects of mills’ hesitancy to accept and store a large inventory, which has now culminated into supply backlogs attempting to match robust demand for lumber. Not to beat a dead horse by revisiting events from what feels like a lifetime ago, but even a temporary stall in volume production has lasting effects on current balance sheets, future capital expenditure and even the logging industry’s overall infrastructure, Brock says.

Domtar’s paper mill in Kings port, Tenn., temporarily shuttered in April 2020 and was expected to reopen after 90 days; instead, it underwent a permanent conversion that impacted Brock’s high-volume dependent operation. “It was hard to make it each week and a big difference in volume when you’re used to pushing 60,000 ft. weekly,” he says of 2020’s summer woes. “We should have been in high production putting back for the winter

From left: Brandon Brock, owner; Tim Combs, cutter operator; Keith Collins, knuckleboom operator; Josh Cornett, skidder operator, mechanic

months but it wasn’t there.” But resiliency beats a pity party any day. Brock has family that depends on him. Despite the 10-hour days and long weekends tinkering with machinery to have it ready to go the following week, Brock can’t help but brag on his crew of men, the reliability of his equipment, and his plans to continue growing his company’s portfolio despite the momentary disruption. “I have a feeling things are going to get better and I’m going to be ready when they do,” he declares. “We’re going to put the hammer down.”

Buyer’s Market

ern Pocahontas Properties clear-cutting 30-year-old pine on reclamation land. BBrock Enterprises hauls hardwood and softwood pulp to the Pixelle (former Glatfelter) paper mill in Chillicothe, Oh., Weyerhaeuser’s OSB plant in Sutton, W.Va., and Columbia Forest Products in Greensboro, NC. The logger sends his sawlogs to BPM Lumber in London, Ky., and Taylor Lumber in McDermott, Oh.

Southern Loggin’ Times Leslie Equipment in Pikeville helps with all of the company’s John Deere equipment needs. found BBrock Enterprises, LLC, in August of last year logging the strip-mining operation’s moun- as 2021’s fiscal second quarter a 5,000-acre tract in Knott County taintop thermal coal removal per- approaches its end, he noted his owned by the second largest mining forming a clear-cut prescription, tar- export markets and domestic lumcompany in the United States, Arch geting a variety of hardwood (hick- ber consumption have come back Resources, Inc., mining shot rock, ory, white oak, chestnut and poplar) strong with the new presidential with BPM Lumber leasing its tim- with 4 in. minimum DBH. They administration. After March 15, ber rights. Arch supplied BBrock were averaging 15-20 loads weekly 2020, Brock says no trees above the rock for free to construct all by looking to fencing, pillar and 1,200 ft. elevation can be cut to preaccess roads on site, which paid high-grade sawlog markets. serve habitat for an endangered bat dividends to both companies. When SLT followed up with population in eastern Kentucky, so Brock’s crew was staged ahead of Brock on how markets were faring he’s currently contracting for WestWell Equipped

Brock runs everything John Deere except for a pair of Barko knuckleboom loaders in the woods. He says having a John Deere equipment dealer on both sides of the company’s Kentucky headquarters— Leslie Equipment in Pikeville and Meade Tractor in Hazard—increases his confidence in his equipment and helps with securing necessary parts. “Leslie has a bigger fleet size and a great ground program,” Brock says. “I tend to purchase more through them and use their rentalto-purchase option for four to six

Brock and his son, Clay Mathew

months before I buy it to make sure I like it.”

Brock’s equipment inventory— including three knuckleboom loaders (’19 John Deere 337, ‘97 Barko 160C and ’05 Barko 225), ’14 John Deere 225D LC excavator with Ryan’s DS28C sawhead, ’12 John Deere 548G skidder with Bear Paw chains, and three John Deere dozers (’09 650J, ’08 750J and ’96 650G) —easily proved a match for the steep, rocky landscape of the Arch Resource tract late last summer.

“I’ve grown quite a bit but I reinvest a lot back into the business,” Brock says. “That’s the thing about the logging business: you have to put money back into it or you won’t have anything in the end. It’s rough on your equipment.”

His ’08 F650 service truck is equipped with an Auto Crane boom, Miller welder, generator, vice, compressor, a plethora of tools and a pressure washer.

Brock runs all woods equipment through his shop after every 500 hours for routine maintenance. Lucas oil and stabilizer is preferred in his engines, final drives and rear ends as well as in his log trucks, which are serviced on 10,000-mile intervals. “When we run everything through the shop I’ll touch up equipment with paint and get it looking brand new again,” he says. “I’m real OCD and like my stuff to look good. When it looks good your workers take better care of it and that helps with reselling.” Josh Cornett, fulltime mechanic, oversees all Brock’s woods machinery and trucks. Brock hauls his own wood and contracts his trucks for local loggers with his fleet rigs, including ’98 and ’03 model W900 Kenworths, ’02 model 379 Peterbilt, ’94 Western Star and four Pitts log trailers. With rate increases, Brock says it’s easier to keep two to three trailers set out and do the work with one truck to cut costs on workers’ comp and insurance while decreasing expenses on fuel, wear and tear and driver pay. Progressive Insurance provides all the company’s coverage needs in that regard.

For additional diversity Brock is involved in abandoned mine land reclamation work for the state, excavation work on the side and contracts his trucks to local loggers. His latest endeavor, due to this year’s boom in lumber prices, is the current construction of a small-production sawmill focused on crossties, fencing boards, flooring, sawdust and chips. Brock anticipates it will be completed and ready to operate by July 1 and that it will turn out 250MBF a month.

The decade that has almost passed since he founded his LLC in 2011 seems like it’s been a short one. In that time, Brock was honored with the 2019 Kentucky Logger of the Year award on August 25, 2020. He gives the credit to his crew, noting that without good help like them, it isn’t possible to be a reliable producer and to run such a clean operation that is compliant with the state’s BMP regulations. “I’ve got great workers,” he acknowledges. “I wouldn’t be able to make it without my crew.”

As far as he’s come and as much as he’s accomplished, the young logger admits he’s still hungry. “We’re going to continue to grow,” he predicts confidently. “I’m ready to put the hammer down.” SLT

On With The Show

■ After multiple Covid-19 delays in 2020, Expo Richmond makes a strong comeback.

Jewell Machinery welcomed attendees. JP Pierson, Pitts Trailers President, caught up with Pat Weiler, left.

Virginia logger Donnie Reaves made the rounds.

By David Abbott

RICHMOND, Va.

The wellknown steam engine that greets incoming attendees at the entrance to the East Coast Sawmill and Logging Equipment Exposition was on the opposite end of the Richmond Raceway lot this year from its usual location. In fact, the whole entrance was moved to the other side, one of the many changes forced on the 37th edition of Expo Richmond by the pandemic.

First of all, this 37th Expo was supposed to have taken place a year earlier, in May 2020, but was delayed by the pandemic shutdowns, first to October of last year and then again to May 2122, 2021. Expo Chairman Jamie Coleman estimates that about 4,000 in total were on hand for this year’s event. That’s just about two-thirds of the normal amount, down by 2,000 from the 2018 totals. There were also about 80 fewer exhibitors this year than in the last Expo. Many companies couldn’t make it due to continuing Covid-related travel restrictions, such as for those coming from Canada. In some cases, large corporate entities opted

Tigercat mascot on one of Binky Tapscott’s ATVs

A diverse crowd came from all over.

The next generation is on board. People were happy to get back out in person.

Many made quality connections.

Nelson Logging of Oxford, NC came with matching shirts for the whole family (not all of whom are pictured here).

Pierson, left, with Forest Pro’s Binky Tapscott, right Weiler, Cat and Carter Cat had a crowd.

to avoid potential risk and sat this one out, a policy that precluded the usual involvement from some local branches, dealers or reps. And yet, many did attend— some, like Pitts Trailers, brought a large group. All things considered (not just ongoing pandemic concerns but also fuel shortages), most of those who attended considered the 2021 Expo a success. Numbers were down, but it was a more robust crowd than it might have been. “We all knew going in that there would be less, and no one really knew what to expect,” Coleman admits. “Most of the people I talked to said it was a pleasant surprise.”

The key word was quality, not quantity; many exhibitors related that the attendees they saw were not casual browsers but real potential leads, interested in making purchases. One Rotobec salesman said he had already seen three quality leads before 10 a.m. on the first day, adding that if he didn’t see anyone else, it would have already been worth his trip.

People generally seemed happy to get back together in person, and some came from long distances: there were loggers from Georgia, Alabama, even south Arkansas. Robert Terrell, Jr. of Georgia’s Terrell Enterprises, Inc. came looking for a shaver to put on their wood yard to make shavings for animal bedding.

Instead of taking much of a breather, Expo organizers (Coleman as well as Virginia Forest Products Assn. Executive Director Lesley Moseley, who Coleman credits with having done most of the “heavy lifting” this year) are already hard at work for the next Expo. They plan to do the whole thing over again next year, to get the schedule back on track for its usual biennial even year rotation. After the back-toback 2021 and 2022 shows, Expo will return in 2024, 2026 and so on from there. Fingers are crossed that next year will see the show completely back to normal, as Coleman says: “We’ll be ready to rock and roll in 2022.” SLT

Making The Grade

■ Researchers seek industry standard for Appalachian hardwood log grading.

By Curt Hassler, Joe McNeel, Jordan Thompson

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is part one of a two-part series on hardwood mill practices in the Appalachian region, based on studies performed by the West Virginia University Appalachian Hardwood Center. It originally ran in the May/June 2021 issue of Timber Harvesting, another Hatton-Brown publication.

Researchers with the Appalachian Hardwood Center (AHC) at West Virginia University have recently conducted more than 60 studies at sawmills in six states to better understand log grades, lumber grade yields and pricing of hardwood logs.

In the course of these studies, the AHC became aware that mills had created their own de facto systems—unique to each individual mill or company. While these millspecific systems could vary considerably in how logs were graded/classified, certain commonalities were evident, including species, scaling diameter and number of clear faces. Certain nuances in assigning a grade were applied by mills, with no consistency between mills and could include log length, position in the tree (butt or upper log), and log end conditions.

Mills in nine Appalachian sates were surveyed to determine procurement strategies and identify common grading and scaling measurement protocols that could be used in the development of a regional hardwood log grading and scaling system. This article documents how the hardwood industry, in the absence of a standardized industry-wide log grading system, conducts grading and scaling operations for hardwood logs in the Appalachian region.

The survey is based on 110 useable survey responses. Responding mill production levels, range from 0.04 to 150MMBF in annual output.

Scaling Diameter, Length

Scaling of hardwood logs is arguably just as important as grading since log pricing is based on both grade and volume of a log. The two measurements required to determine log volume are scaling diameter and length. Scaling diameter for hardwood logs is determined by measuring the diameter inside the bark at the small end of the log (DIB). Total log length is measured in feet. With these two measurements, the total volume, in board feet, can be calculated using an established log rule. Three log rules consistently used by the industry include the Doyle, Scribner, and International ¼ inch Log Rules.

The most common log rule used by mills was the Doyle log rule, with 76% reporting its use. The second most used log rule was Scribner decimal C (11%), followed by the International ¼ log rule (10%). Three percent of the surveyed mills used some combination of log rules, but in all cases, Doyle was part of the combination. The Doyle log rule was used consistently across all nine states in the sample, with Ohio and West Virginia using it exclusively. The International Log Rule saw the greatest use in Virginia and North Carolina, while the Scribner Decimal C log rule was used mostly in Pennsylvania and North Carolina.

Four options for measuring scaling diameter were reported in the survey: Average—The largest and smallest measurement taken through the center of the heart added together and divided by two; Short-way only (SWO)—the shortest measurement of diameter crossing through the heart of the log; Short-way then 90 degrees to that-

Developing workable regional scaling and grading standards will require plenty of communication, negotiation.

Inconsistent grading practices mean getting the best value can be difficult.

(SW+90)—the shortest measurement of diameter crossing through the heart of the log and then 90 degrees to that, adding those two measurements together, and dividing by two; and Other—including purchasing logs by weight and measuring just the small end of the log inside bark (with no further explanation). The two most common methods reported were Average (43%) and (SW+90) (31%), with a combined total of over 74% of responses.

There were six methods reported by respondents for handling fractional inches when measuring scaling diameter. The options were:

A—Round up if the fraction is ≥0.5 inches (34%)

B—Alternate rounding up and down if the fraction equals 0.5 inches (24%)

C—Round up if the fraction is ≥0.75 inches (10%)

D—Always round down (9%)

E—Round down if the fraction is ≤0.5 inches (8%)

F—Other options included rounding based on log quality or an implication that no rounding took place (15%)

Mills were asked whether they buy logs of even lengths only or if they also buy odd length logs. For 107 responding mills, 60% purchased only even length logs, while the remaining 40% purchased both even and odd length logs. For those mills that purchase only even length logs, this creates a possible situation where a logger produces a 9 ft. log, sells it as an 8 ft. log to the mill— and the mill then produces and sells 9 ft. boards.

Trim allowance ensures that a mill can saw lumber full length and not be forced to trim a foot or more. Of the 100 mills responding, 26% preferred four inches of trim, while 25% of the respondents reported using “Other” preferred lengths of trim ranging from 0-12 inches. Twenty-five percent preferred six inches of trim and 24% preferred a range between four and six inches.

If the preferred trim allowance was not present in a log, respondents were asked what trim allowance is acceptable before initiating a scalebased length deduction. A variety of minimum trim allowances were reported: 1 inch—20%; 2 inches— 32%; 3 inches—12%; 4 inches— 16%; Other—20%.

Scaling Deductions

In many cases, mills use established scaling rules, but then add their own “rules of thumb” that result in custom scaling practices.

Defects that affect lumber yield present a range of issues. Questions were posed about specific scaling defects, including double hearts, sweep, holes and shake. Perhaps the most difficult aspect of log scaling is dealing with scaling defects and developing a basic understanding of how they are handled. Understanding how they are most handled by the industry can help define the best options for a standardized scaling system.

A double heart is created when the bole of a tree diverges and forms two forks, a common occurrence in hardwood logs with a negative effect on log value and lumber quality. Mills provided nine different approaches to determining the amount of deduction for doublehearted logs.

Concerning deductions for sweep, about 37% of responding mills use diameter and length deductions when handling sweep, 33% reported using a diameter deduction only, nearly 18% used a length deduction only, while 12% did not use any diameter or length deductions.

Holes that occur due to heart rot

generally affect the cant section of the log where the cant is located. It is generally difficult to assess the impact of a hole and associated decay on lumber recovery and quality.

Nearly 37% of responding mills use both diameter and length deductions for holes; just over 27% used a length deduction only; and 25% used diameter only. Nearly 11% of surveyed mills did not use any diameter or length deduction and instead simply estimate the board footage loss caused by the defect through a visual inspection.

Shake occurs as an end defect in hardwood logs, where the growth rings separate from each other. Almost 39% of responding mills used both diameter and length when making deductions for shake, followed by 27% that used a length deduction only and 21% used only a diameter deduction. Just over 13% of the surveyed mills used only visual assessments of the loss of board footage caused by the defect.

Grading Protocols

Grading hardwood logs is a process that uses the exterior features of logs to determine quality (or grade). Generally, a log is divided into four quadrants or faces, and each face is evaluated independently to determine the presence or absence of defects. The grade is then based, in part, on the number of clear faces.

Of the mills sampled, 89% graded logs without rolling to examine all four sides/faces, while only 11% indicated they did roll logs when grading. The failure to roll the log is probably associated with saving time in a production setting where time is of the essence in getting loads graded and scaled as quickly as possible.

About 42% assumed the bottom of the log was “similar to other 3 sides,” followed by “clear” assumed by 34% of respondents. Assuming the bottom face is “clear” is often a false assumption that unfairly boosts the quality of a particular log. “Other” responses (24%) assumed that the bottom face on each log has at least one defect or that half of the logs contained defects on the bottom face.

Finally, mills were asked if they would support the development of a standard log grading system. Of the mills that responded, 66% indicated they would support such an effort, 34% would not. Mill size did not

Wide scaling variability among log buyers makes for inefficient economic decisions across the industry.

Conclusions

The various scaling and grading protocols examined in this survey, taken together, confirm that log grading and scaling are highly variable and depend in many cases on mill-based rules of thumb relative to grading and scaling standards.

A variety of ad hoc systems are used in Appalachia, making it difficult to reach intelligent economic decisions about where to sell logs to maximize value. Ad hoc grading and scaling protocols do not serve the best interests of the hardwood industry. However, the authors believe the results do indicate a reasonable path forward in developing a standardized system.

The Doyle log rule was by far the most common rule in use. But for a standardized system to attain broad acceptance, all three rules cited by respondents must be permitted (Doyle, Scribner, and International ¼ inch). Similarly, the option of buying both even and odd length logs must be included, even though a majority of mills (58%) purchased only even length logs.

Further, the issue of trim allowance showed that discussion among log grading practitioners and mills would be necessary to reach consensus about handling such important factors in a standardized system.

In the case of scaling diameter, a method must be chosen that is common but also does not favor buyer or seller in any significant way. The most common response was to measure the smallest diameter then the largest diameter and average them—but that tends to slightly favor the seller of logs.

The best option would appear to be to measure the shortest diameter, rotate 90° and take the second diameter measurement, and then average them, which was the second most common response (31%).

Handling fractional portions of an average scaling diameter also resulted in a number of options reported by respondents. Perhaps the most logical approach is to simply decide how to handle a halfinch fraction. For practical purposes, a rule that says “…round down if the fraction is ≤0.5 inches and round up if the fraction is >0.5 inches…” seems reasonable.

The survey was not designed to elicit specific rules of thumb being used by respondents, as that would have unduly complicated the responses. The most reasonable approach is to analyze log and lumber yield data in such a way that the selection of a rule-of-thumb would not significantly alter the overrun/ underrun expected from the log in the absence of the scaling defect.

Even with 66% of responding mills favoring a standardized system, the elements of such a system must be simple to use in a production setting, mirror what the industry is currently using and serve as the basis for efficiently pricing hardwood logs.

Log grades must be based on extensive empirical data that is collected on a “per log” basis. The grades would necessarily be based on lumber yields of NHLA lumber grades, which relate back to scaling diameter and number of clear faces. It’s only by combining log grade with overrun/underrun, sawing costs and lumber/cant pricing that the pricing of logs can be consistently determined.

Barriers are created when sawmills offer a variety of scaling and grading options. In that case, it can be difficult to define the best option for producers, landowners and contractors. The opinions of all interested stakeholders must be considered in order to ensure acceptance, implementation, and continued development of a standardized hardwood log grading system. SLT

Joseph McNeel is Director of the West Virginia University Appalachian Hardwood Center (WVU AHC); Curt Hassler is a research professor at WVU AHC; and Jordan Thompson is a procurement forester for Millwood Lumber in Gnadenhutten, Ohio.