7 minute read

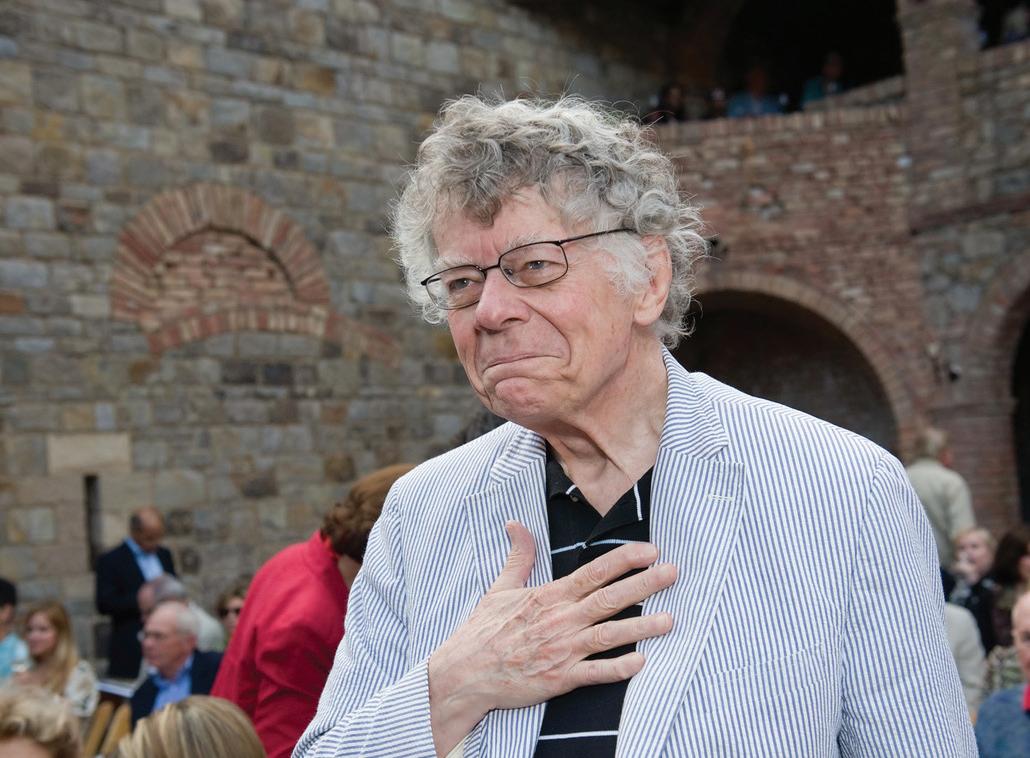

THE ORIGINAL HAUTE LIVING TALKS WITH GORDON GETTY

By Lisa Delan

GORDON GETTY SPEAKS WITH THE VOICE OF A 5-YEAR-OLD.

That is to say, his exuberant expression of self, creative intent, and heartful engagement with humanity found its voice by age five and has not wavered. In the eighty-five years separating him from the boy he was then, that voice has grown richer, deeper, more nuanced, and erudite, but its essential nature remains intact. It is rare to know who you are at such a young age. It is rarer yet to carry that foundational spirit through almost nine decades of life. As anyone who has had the good fortune to know Gordon Getty can attest, there has never been and will never be another like him. Even his external attributes are singular. Getty’s laughter is instantly identifiable, his gestures paint stories, and his singing carries the colors of a life deeply lived.

Getty is a true renaissance man whose work spans multiple fields, including music, literature, evolutionary biology, theoretical economics, strategic philanthropy, and winemaking. His broad range of expertise reflects a uniquely “golden brain,” the term applied to a minority of people who equally utilize left and right brain functions. In other words, Getty is intellectually ambidextrous. Indeed, his greatest fulfillment is found in progressing simultaneously in multiple pursuits, alternating his focus between the creativity of the arts and the structure of the sciences (though he would argue that there is great creativity to be found within structure). Uniquely, winemaking is both a science and an art. Not surprisingly, the oenophile has found many kindred spirits in the Napa Valley. Nowhere is this more evident than in his delight with Festival Napa Valley’s annual summer celebration of music and wine. Getty has been involved with the festival since its inception, and the two weeks in July spent surrounded by musicians and vintners is one of the highlights of his year.

At almost 90, Getty is still constantly evolving. He thrives on challenging himself, turning the work before him around in his mind like a Rubik’s Cube as new forms reveal themselves. But there is always time to smell the roses (or, more aptly, the grapes). He recently shared, “The older I get, the busier I am, and the busier I am, the more free time I have!” If Getty’s greatest satisfaction is found in his work, then his greatest joy rests with his family and friends. His eyes soften and shine whenever he speaks of his children and grandchildren, and he loves nothing more than being in their presence.

He has close relationships with nieces and nephews and embraces his dear friends with familial affection. The pandemic was a time of great personal loss for him, and it was in the company of family and close friends that he found resilience. Now halfway through his 89th year, Getty is thriving. Most days find him at his desk, hard at work bringing new ideas into the world, with evenings aglow sharing dinner with loved ones around the kitchen table, breaking bread, uncorking choice vintages, and of course, singing.

I have worked alongside Gordon Getty in his musical life for over three decades and recently sat down with him to revisit some of his high points and challenges as a composer over the years. Along the way we touched upon a handful of additional topics about which he is equally passionate. Conversations with Gordon Getty are seldom linear. I have discovered that the greatest insights into his process are revealed not in response to the question asked, but in response to the question he wishes had been asked. Excerpts of our conversation follow. Read on and enjoy the journey!

HL: Which performances or recordings of your music stand out most vividly for you?

GG: Well, the first performances of Joan and the Bells on the Volga River tour with the RNO (Russian National Orchestra), where you sang Joan, were stupendous. The orchestration had come to me fully formed and I wrote it rather quickly. Those rehearsals were the first time I heard the whole piece with orchestra, and thought, “Jeepers, Gordon, you’ve really got it this time!” And certainly, Joan and the Bells, when Pentatone recorded it in Munich (with Melody Moore and Lester Lynch), was a high point. The recording of my piano pieces with Conrad Tao was unbelievable, because he’s just so good! I mean, scary good! I remember he was not quite 18. Can you believe that? He was still a minor, and his parents had to travel to Skywalker Sound with him. That recording was a doozy! And I’m really looking forward to the new recording of Goodbye, Mr. Chips (Getty’s most recent opera, which was released as a film during the pandemic) early next year. That will be shortly after my 90th.

HL: You are engaged in such disparate fields—music, literature, economics, evolutionary biology—is there a throughline that connects all these different modalities for you?

GG: You can’t compose unless you have a composer’s ear—it’s the organ of Corti (responsible for transduction of auditory signals). You need an exceptionally accurate sense of relative pitch; absolute pitch has nothing to do with it. It might have something to do with verse, too, because the ear in verse is very important, as you know, because you’re very good at that. But as far as economics and evolutionary biology, those two fields are both almost pure logic. You don’t need much evidence at all in either field—you have to puzzle things out. I do these puzzles in the mornings—Sudoku and the puzzles in the New York

Times—and the crossword puzzle in the Financial Times, which is hilarious, and it’s a killer, too. I spend too much time at that, but I love it! Orchestrating in itself is a kind of brainteaser, in which all of the instruments have to connect in just the right way to create the whole. So, I love to solve puzzles, and I seem to be good at it. I always knew that I could compose, I always knew I could write verse, and I always knew I was a good problem-solver.

HL: I remember when Misha (pianist, conductor, and composer Mikhail Pletnev) said to you, “Gordon, you live in a world of art and music, of beauty, language and deep thought. You are not of this world.” Over the past 30-plus years, I’ve known you to spend most days diligently working to explore and contribute to these worlds. Do you ever wonder if your intense focus comes at a price?

GG: I have a funny mind. I’m the last guy in an airport terminal or on the highway—back when I drove—to understand instructions and know where to go. I understand the words, but they are saying, “Sacramento is this way” or “North is that way.” And I’m saying, “Wait a minute, I need more information!” Everyone else gets it and I don’t! A lot of people have much more in the way of practical gifts than I do. I doubt that I’d score four out of 10 on the scale of practical gifts. It’s funny, because we’re born with different noggins, like Jack Spratt and his wife. My dear wife, of course, was great, and she organized all the things that I wasn’t good at, so she spared me much of that.

HL: She also offered some lovely, creative input, like suggesting you add a love duet to your opera, The Canterville Ghost GG: That too, that too. She had astute powers of observation and was keenly insightful.

HL: What new music are you working on now?

GG: “Saint Christopher” (for chorus and orchestra). I can tell you it’s a puzzle, because this time I’ve tried to channel Bach—and I’m telling you, holy mackerel, that’s a tall order!

HL: You and I have spent a lot of time grappling with the “survival of classical music,” given current cultural trends. What gives you hope for the future of music?

GG: Well, I’m thinking about the ancient bone flutes found in caves from over 30,000 years ago that have gone down to the museum in Dordogne in Les Eyzies (the Musée national de Préhistoire). These are actual bone flutes, with holes punched in them; people played these flutes. I’ve heard recordings made on replicas and, by God, they sound like modern music to me. The impression I drew is that people played this music for a reason, and nature knows only one reason: it’s selective advantage (which suggests the best adapted individuals survive).

My hypothesis—which is worth less than a molecule of my best wine!—is that if you saw someone around the campfire that didn’t respond to the music, you wouldn’t trust them. You would gravitate toward other members of the group who showed interest in sharing the music. That’s whom you would bond with. Now studies have found that music and empathy are linked—they are processed via the same neural pathways.

If we’re looking at evolution, these pathways influence the way we navigate our social environment. We are drawn to connect with others who demonstrate qualities, like empathy, that we trust, and that is how we build strong communities, better equipped to withstand the hardships humans face. Of empathic people, we say they have a soul, meaning a deep heart, a caring for others. And as long as we have a soul, we will always have music.

Notes About The Author

Lisa Delan’s poetry and prose have been featured in literary journals such as American Writers Review, Burningword Literary Journal, Cathexis Northwest Press, Poets’ Choice, and Viewless Wings. She has been nominated for a 2023 Pushcart Prize.

In 2022, Festival Napa Valley commissioned settings of three of Delan’s poems by composers Jake Heggie, Jack Perla, and Luna Pearl Woolf, which premiered by Alexandra Armantrading and Kevin Korth as part of the festival’s summer season. Delan is currently working on a libretto for a new choral work with Volti composer-inresidence, Mark Winges, to premiere in the SF Bay Area.

When she is not writing, you can find the soprano, an international performer who records for the Pentatone label, singing works by some of her favorite American composers.