Buried in the notes app of my phone, tucked behind scraps of unfinished poems, stumbled upon quotes, minimal grocery lists, and rushed notes from meetings is perhaps the only fully fleshed out piece of writing that I’ve ever produced. Considering how slow I am to get my thoughts on a page, it would make sense that this particular work is only two words long; those two words were no doubt the product of extensive mental labor.

Thinking about it now, I’m not sure why it was such an ordeal to generate such a simple phrase. I don’t recall being under any sort of time crunch, and I wasn’t faced with the weight of crafting a loved one’s obituary or omnipresent figure’s speech. The pressure must have stemmed from what came before, what I had to follow up with this budding idea of mine. The not so distant past summer saw communities being ravaged by two viruses: one of the body and one of the state.The devastating amount of loss that resulted from these insidious diseases created the need for more dialogue surrounding space and who is allowed to take it up, who gets to move through this world with lightness and who is made to move through it with heaviness.

After months spent flipping through news channels and scrolling through feeds memorializing lives cut all too short, I began trying to imagine a world in which the question of who gets to make it through another day doesn’t exist, where the sometimes beaming, sometimes stoic faces that were flashing across my screens had gotten more time. I mulled over and obsessed over how I could reach this place in my lifetime and wrote my almost literal two cents down at 8:52 pm EST on August 22, on a night where I could already tell I wouldn’t be retiring early.

Following months of inventing, curating, and polishing this world, placing one foot in the surreal with another grounded in the starkness of reality, opening my eyes and ears to subjects ranging from the role of heritage in art to the carceral state and the reclamation of indigenous identity, I finally am ready for you all to see this universe that I and countless friends, both new and old, have worked so tirelessly to engineer, this Dream State that started its life in the notes app of my phone.

The creators behind Haute Magazine are my dream team, and I want to dedicate this page to them. Thank you to our writers, photographers, videographers, designers, and marketers for sharing your voices, perspectives, and endless creativity in our Spring 2021 issue.

I’m beyond grateful to Awo, Editor in Chief, who worked thoughtfully and tirelessly on every detail of this issue. Her writing is like velvet, and her demeanor makes you feel like you’re in great hands. Awo, without you, this issue wouldn’t have come to fruition; I appreciate your unwavering support as we ventured through uncharted paths together.

Our creative leadership team jumped into the deep end, coordinating hundreds of images and reading thousands of words to achieve our goal for this issue to look and sound otherworldly, yet approachable. Alice, Director of Writing: thank you for your fearlessness and for bringing your creativity to the team. Ally, Director of Photography: I’m indebted to you for calming the chaos and uniting our visuals with your keen eye. Hala, Director of Copy, and Annabel, Director of Diversity and Inclusion: thank you for your dedication, energy, and joy — and how you light up our many meetings. Shreya, Visual Design Director: I couldn’t have put our spreads in better hands. You command every meeting with confidence and poise, and remain focused and kind as you form relationships with each designer. I am beyond proud of you for conquering the daunting task of assembling the 400+ pages of this magazine, all with an unmatched optimism. Peri and Izzy, Content Directors: you never cease to amaze me. Peri, your humble demeanor and incredible multimedia and design contributions blow me away. Izzy...where do I start? Your impeccable sense of style, prolific skillset, and bullet-proof work ethic challenged us to dream bigger. Abbey, Multimedia Director: you pioneered our Masterclass series with a smile and your go-getter attitude adds so much excitement to the team. David, Director of Finance, and Shanaya, Director of Events: your passion for Haute is infectious. Thank you for bringing your fresh enthusiasm and passion to the magazine.

Our dream team would not be complete without our graduating seniors. Christine and Alyssa, thank you for advising our E-Board and making us feel comfortable and empowered in our new roles. I’ll miss hearing your insightful comments and ideas every Sunday. Finally, Jason and Diana, co-founders and visionaries of Haute. Your dream is what brought us here today and your continued action, dedication, and spirit has helped sustain it. I’ve learned so much from both of you, and thank you for supporting our new team and the future of our publication. Your legacy will be felt at Haute forever, and I’m grateful that you trusted me to take the reins as Creative Director. I promise to keep the dream alive.

no friends mazie

bellyache Billie Eilish

Ivy Frank Ocean

Pink + White Frank Ocean

Japanese Denim Daniel Caesar

Lover Taylor Swift

Letters Metro

La La Land Bryce Vine

Lost in Yesterday Tame Impala Outro M83

vaya con dios Kali Uchis

xo goth gf

All The Time Bahamas

Forever Labrinth

Ethio Invention no. 1 Andrew Bird

fever dream mxmtoon

sippy cup mazie

Editor in Chief Awo Jama

Creative Director Sydney Loew

Co-Founders Diana Fonte + Jason Cerin

Director of Writing Alice Han

Director of Photography Ally Wei

Director of Visual Design Shreya Gopala

Director of Finance David Sirota

Directors of Content Izzy Lux + Perianne Caron

Director of Multimedia Abbey Martichenko

Director of Copy Hala Khalifeh

Director of Events Shanaya Khubchandani

Director of Diversity and Inclusion Annabel Haddad

Photography Advisor Alyssa Kyle

Marketing Advisor Christine Du

Alex Fulmer

Allison Walsh

Annabel Haddad

Ashara Wilson

Carly Lieder

Courtney Dowling

Diego Frankel

Hayley Feinstein

Jessie Silverstein

Lizzie Schneider

Maya Elimelech

Shay Martin-Jones

Sophia Ungaro

Victoria Valenzuela

Kiara Simmons

Kiera Smith

Leslie Huang

Madison Kloeber

Maria Eberhart

Natalie Serratos

Nikisha Roberts

Niq Tang

Stacy Shen

Adeline Wang

Alex Lam

Ally Wei

B Bibikova

Jacob Yeh

Josh Lin

Katherine Han

Kaohom Boonyalai

Kellie Chen

Alex Policaro

Anusri Mittal

Ariella Rabbani

Audrey Yang

Celestine Seo

Dinushi Pathirana

Ethan Woo

Haeri Kim

Hannah We

Jenny Yoon

Jessica Fan

Rianne Aguas

Taylor Collins

Vania Prayogo

Alexandra Abrams

Ankita Reddy

Anna Sun

Brooke Blair

Daphne Zhu

Dylan Weinstein

Emily Huang

Jamal Seriki

Jessica Lee

Morgan Darby

Perianne Caron

Rachel Wang

Sarah Chan

Sarah Kim

Sehee Cho

Tahlia Vayser

Fool Me Twice Sarah Bahbah

Runway Dreaming Lizzie Schneider + Ally Wei

Bloom Jacob Yeh

Remember Me Jason Cerin

Room 909 Johan Wennerström

Tumblr’s Persistence as an Online Safe Haven Annabel Haddad + Perianne Caron

Love Story Elle-May Leckenby

Becoming Visible: The Resurgence of Tongva Identity in Los Angeles Diego Frankel + Jacob Yeh

Sketches of Spring Tina Sonsa

I Wore a Onesie Courtney Dowling + Sofie Sund

Take Root Maria Eberhart

Idyll Skies Alex Lam

Exonerated Nation Victoria Valenzuela + Sarah Kim

Iridescent Exposure Niq Tang

Cherry Innocence Kellie Chen

To Poetry, Mirrors, and Myself Shay Martin-Jones + Kiera Smith

Reflections Natalie Serratos

Fleeting Youth Kaohom Boonyalai

On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog Ariann Barker + Alexandra Abrams

mazie: Cover Star Awo Jama + Ally Wei

Indulge Kiera Smith

Making It: Black Women in Business Featuring Girl Cave L.A Ashara Wilson + Perianne Caron

Women Through the Looking Glass Serena Ngin + Ashley Armitage

Squiggle Diane Villadsen

RYL0: Her take on the Post-Internet Genre of Hyperpop Maya Elimelech + Natalie Serratos

Pastel Salt Caitlin Fullam

Hide and Seek Ally Wei

Shae Brock Forrest Leo

The Descent of Love Hayley Feinstein + Cayetano González

Alter Ego B Bibikova

Matea

Pioneer of Sustainable Luxury Shanaya Khubchandani + Kiera Smith

The Shell of a Soul Sophia Ungaro + Inma Vivas

Once Upon a Reverie Stacy Shen

Coming Out and Coming of Age: The Complex Role of Fashion in the LGBTQ+ Community

Allison Walsh + Sara-Anne Waggoner

Disillusion Leslie Huang

Op Vlieland David van Dartel ve.

Colored in soft, warm hues is Palestinian photographer Sarah Bahbah’s latest photo series, “Fool Me Twice.” Meant to explore the “complex and often torturous dynamic between an ‘anxious’ partner and an ‘avoidant one,” the series follows the budding relationship of two young lovers, played by Noah Centineo and Alisha Boe. The series, which is currently being released in installments through Bahbah’s Instagram, has already amassed a considerable amount of interest, as each post boasts hundreds of thousands of likes. With fans pressing Netflix to make “Fool Me Twice” into a film, it is clear that Bahbah’s series is already resonating with her devoted fan base.

Sarah Bahbah, the Palestinian, Australian-raised artist crystallises the universal but rarely captured experience of oversaturated, intense feelings and imperfect relationships. Her protagonists give voice to the vast spectrum of emotion, spanning the desire for inner peace, true love, fear of commitment, playful ambivalence towards life and the paradox of wanting intimacy but craving isolation.

Models

Alisha Boe

Noah Centineo

Management

Lena Khouri from Between East

Art Department

Ester Song Kim

Assistant

Natalie Goldstein

Makeup

Alexa N. Hernandez

Styling

Ib Abdel Nasser

Hair

Josh Liu

Alex Henrichs

Haute couture is a dream state in itself -- the allure of luxury draws the public like a moth to a flame, and in every facet is an elevation from common necessity. Not only is a visit to a highend boutique an experience in the customer service aspect, but brands’ exclusive fashion shows elevate the already high fashion ex perience into an entirely different world. Worldwide fashion weeks are high-profile events with celebrities and fashion industry royalty flying in to attend. With the COVID-19 pandemic, designers had to pivot in order to create virtual edi tions of the otherworldly shows that provide a spectacle and a welcome respite from the outside world.

Typically, a fashion show takes place in a large venue equipped with a runway and many seats for attendees to view. For example, the Tommy Hilfiger New York Fashion Week show in 2016 was located on a pier and featured a carnival complete with rides, popcorn and pop-up shops. The show itself could seat up to 2000 guests and served as the main “attraction.” Oftentimes, the shows have been planned long in advance to go with the collection’s theme and inspiration and provide a deliberately artistic lens for the viewer to see the clothing through by utilizing setting, sound, and visuals. A prolific exam ple of transporting viewers through fashion shows and the col lections themselves would be the shows of Alexander McQueen. One of the most innovative creative minds of the 20th and 21st centuries, McQueen created worlds within his shows all centered around the clothing he designed. His Spring 1999 show “Number 13” highlighted the fashion house’s craftsmanship abilities, including models in ornately carved prosthetic legs, wooden angel wings and an entire skirt made of wood panels shaped to form a fan. The most avant-garde aspect of the show that lent it its dreamlike quality was the

final look. Model Shalom Harlow stood on a turntable in a plain white shift dress, gracefully sprayed in red paint by robots as she rotated. The dress was designed before the audience’s very eyes and went on to be exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s costume collection. McQueen and creative director Sarah Burton, who took over the fashion house after his death, are known for their outlandish shows and imagination. For example, in one show taking place against the backdrop of a forest, a model’s head was adorned with antlers. In a break from the avant-garde nature McQueen tends to be drawn towards, the Autumn/Winter 2010-11 “Savage Beauty” show featured ornately gilded dresses reminiscent of Renaissance textiles and was fairly wearable. Evoking medieval Madonnas and Byzantine empresses, the feature that dramatically elevated the collection’s dream state was the show’s setting. Located in a heavily laquered Parisian chateau, the sumptuousness of the collection’s surroundings paired with the regality of the clothing made those in attendance feel as though they had traveled back through time to the late 1700s.

Unfortunately, with the onset of COVID-19 in 2020, the majority of the fashion world was forced to become virtual. Fashion shows were physically canceled, but that did not stop brands from putting on a show. Louis Vuitton turned to augmented reality technology, sending each attendee a pair of goggles from which they could watch the show with just models present in a physical form in Paris. Other brands pivoted as well, showing the flexibility of

Lizzie Schneider is a student at the University of Southern California pursuing a degree in Communication.

Ally Wei is an Los Angeles-based photographer who specializes in fashion and editorial photography. She loves going on adventures and spending time with friends.

Ally studies Media Arts and Practice at the School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California.

A living fairytale of high fashion. Elegant dresses in mystical environments, featuring empowering and bold women.

Models

Annika Gavlak

Elsie Wang

Balmain opted to display their collection in typical fashion, although attendees were merely virtual faces in the crowd. Prada chose to create a line for the Spring/Summer 2020 season made up entirely of upper body logo work so as to appear fully decked out when a buyer were to be on a Zoom or Facetime call, and Gucci created an entire online “festival” complete with Gucci remotes sent to attendees in their goodie bags in which art features and celebrity appearances marked the showing of their 2020 collections. The dreaminess of these occurrences can partly be attributed to the modernity of technology usage, but for the majority of the population, an invite to attend high fashion shows, be it virtual or in-person, is a dream in itself.

Off the runway in designer stores, shopping is above the average department store or boutique experience. One is greeted personally by a sales associate who caters to every need and is typically offered a refreshment and a place to sit. In Beverly Hills on Rodeo Drive, not only does Gucci have a boutique, but also has its own café restaurant on its rooftop, further offering an all-encompassing experience. When on Rodeo itself, shoppers step into a tree-lined wonderland of glittering window displays and sumptuously dressed shoppers complete with expensive cars and pricey sit-down restaurants. It is an oasis from the hustle and bustle of Downtown Los Angeles. A unique, and often overlooked feature that makes shopping at luxury store locations a dream state is the personal relationship clients formulate with their sales associates. Relationships typically develop within a few years and if a rapport is built strong enough, especially at stores like Hermes, a shopper can get insider

access to exclusive products and even get on uber-exclusive waitlists for elusive products like the Kelly or Birkin bags. Another popular luxury locale is Asia, where the landscape of luxury shopping is shifting and where a third to a half of global luxury designer sales originate. The game of designer exclusivity and becoming a deserving customer is a feature of luxury shopping that those outside the world of fashion may not be aware of in the slightest. It is yet another gate in the path to the designer dreamstate.

The allure of luxury is its perceived unattainability, and the experience goes beyond simply clothing. The signal of wealth and attentiveness that comes with it is something that many cannot fathom and the lucky few get to experience from each new season. The production of catwalks and fashion shows are truly the lifeblood of designer fashion, for without creativity, a dreamworld created both for the masses and the few would not be possible. During uncertain times like the current COVID-19 pandemic, further questions about the unattainability of luxury fashion are called into question. Considering whether it is tone-deaf to even put on fashion shows, debating if fashion even holds as much weight during a global crisis, and the industrial shift to virtuality have been integral questions to think about for both brands and consumers. From a consumer standpoint, online shopping has held more weight than usual as the idea of wearing fun clothing in the future to events post-pandemic is a light at the end of the tunnel. The catwalk broadcasts serve as a welcome distraction from the bleak statistics released each day on news outlets and can be considered a creative dream for the future.

Jacob Yeh is an Pasadena-born and Los Angelesbased photographer who specializes in portraiture and abstract photography. He enjoys cinema, music, and most recently, cooking. Jacob studies Communications and minors in cinematic arts and media studies at the University of Southern California.

as a twin.

Throughout these past four years, I have constantly been faced with the question, “what path do I want to forge for myself?” Individuals my age find ourselves at a crucial point in our lives, as we must make decisions that have a direct impact on our future and ultimately, the legacy we establish for ourselves. With the job market becoming increasingly competitive, it feels like there is simply no time for you to not know what you want to do. I find myself as part of a generation that is thinking about financial security and success earlier than anyone else. This is due to the fact that we have constantly been taught to recognize the relationship between wealth and success, an idea that has only been magnified since I started attending the University of Southern California. As seen by the number of last names inscribed on the sides of buildings and donning the tops of scholarships, it is almost as if legacy has shifted from “who they were” to “what they were able to buy.”

According to Merriam-Webster, success can be defined as “the gaining of wealth, respect, or fame.” When you grow up seeing explicit phrases such as these printed on something as official as a dictionary, it feels difficult to dispute. Many people grow up believing that success involves earning large amounts of money, being academically gifted or serving as the leader of a powerful institution. It is for this reason that many young people pursue careers as doctors, lawyers and engineers, as they are well respected occupations that practically ensure financial security and, relatedly, future success. Society has pruned us to recognize the idea that wealth leads to status and status leads to power. This makes sense, as success through these avenues can be tangibly measured by annual income, company hierarchical standings and general reverence an occupation receives from society. We currently find ourselves in the midst of a data-driven world where numerics and statistics can be used to draw conclusions to concepts as broad as success.

With wealth comes the opportunity for people to exercise forms of social influence. “A lasting legacy of support” is how one of USC’s many naming opportunities is described online, which range in price from $25,000 to $3.5 million. Emblazoning the name of donors onto buildings, bricks, plaques, scholarships and programmatic funds has been

a way for institutions to entice check-cutting for years. Experts say that these donations are often “a combination of vanity and legacy—with an emphasis on the latter.” Wealthy families want to envision and put into place what their legacy is and how to pass it to the next generation. While not inherently narcissistic, as each naming is tied to a philanthropic bequest, these items undoubtedly play a role in each donor’s legacy. These namesake items serve as a physical and long-lasting reminder of the significant role that person played. It is a guarantee that generations to come will know that name and connect it to the success that the given entity amasses; however, is a namesake able to represent the totality of one’s legacy?

When I asked some of my friends their opinion, one said the names that decorate our campus “don’t mean much to me since I don’t know these individuals personally, I just know they were wealthy enough to put their name on the front of a lecture hall. For me, it doesn’t speak to who they truly are as an individual.” Someone else joined in to say “just because you have enough money to buy a bench doesn’t necessarily mean that you are a good person.” While it is a hope that wealthy individuals are not donating money with the sole intention of having their name on a building that will outlast their own physicality, responses like these, and those expressed in numerous studies, support the idea that material aspects of one’s legacy are not all-encompassing.

Strayer University recently conducted a national study known as the “Success Project Survey’’ to determine what Americans’ modern definitions of success are. Results showed that 90% of respondents

thought success depends principally on happiness rather than power or prestige. In his response to the results of the study, Dr. Michael Plater, president of Strayer University, said “I think people will be surprised to hear that the vast majority of this country no longer views traditional wealth and fame-based notions of success as having ‘made it.’’’ As mentioned previously, we do still live in a time where money plays a key role in our daily lives, but it is important to recognize that it is one of many factors.

The concept of legacy often reminds us of death, but the two are not mutually exclusive. Death informs life by giving you a perspective on what’s important, but legacy is really about life and living. It helps us decide the kind of life we want to live and the kind of world we want to live in. The giving and receiving of legacies often brings with it a multitude of emotions: longing, remorse, anxiety, fear, contentment, gratitude, humility, love. In experiencing this spectrum of emotions, there is a reflective period that forces you to take into account all of your accomplishments and shortcomings, what you’ve done and hope to do and the introspection of your life as a whole. For many, that involves looking to an individual they admire and the things they did to give their life meaning.

During my freshman year of college, I was told that my grandmother had been diagnosed with lung cancer. Due to the stage the cancer was in at the time of diagnosis, she was given a six-month time frame left to live. Since her symptoms were not present and she would always say how she felt as good as could be, I never really thought much of it. However, Thanksgiving came around and it was as if

everything came crashing down at once. Her condition worsened exponentially, she was given an even shorter period of expectancy. The person whom I had known all my life was slipping away right before my eyes. One short month later, I received the call saying she was gone.

My parents asked if I would give the eulogy speech at her memorial service. At first, I was unsure how I was to take 87 years of someone’s life and condense them into a mere 400 words. It was during this time that I had to look back on all the memories that left an impact on my life and think about what legacy truly meant to me. Through this process of reflecting and writing, I was able to wade through years of what I thought legacy was supposed to mean and solidify my own definition of it. For me, it was that when a person truly impacts your life in a significant way, it is not the amount of money they had in their bank account, the size of the house they lived in or any other materialistic factor that mattered, but instead the social and personal impact they left on your life.

We all want to be remembered in some capacity after we die. Whether that be for the work we did in our professional field, the acts of service we took part in, or simply for the kind of person we were, there is a collective goal to not be forgotten. As humans, we have an inherent desire to create meaning in our life and to have that meaning live on after us. When our accomplishments can be recognized and revered by others, it almost serves as an existential affirmation that our life mattered. As a society, we contextualize this construct as legacy. Built on stories, traditions, memories, hopes and dreams, legacy is the interconnection across time that satisfies a need for those who have come before us and a responsibility to those who come after us. Legacy is fundamental to what it is to be human.

Grooming

Robert Maldonado

Makeup

Alejandra Villanueva

Styling and Nails

Alissa Nguyen

Set Design

Elizabeth Yin

Videography

Abbey Martichenko

Buildings may crumble to the ground and plaques may rust over, but one thing that cannot be erased posthumously is the personal connection that is established between two individuals. My grandmother is physically gone, but psychologically she is everywhere. She has become a part of me, my parents and my family on a cellular level, which allows many roads to still lead back to her. For me, that is what defines a legacy: Being able to push beyond the veil of grief and mourning to reveal the beauty that emerges once you accept the finality of goodbyes. It is the traits and ethics that people bestow upon those around them that live on after one dies. For both young and old, the power of legacy enables us to live fully in the present. You understand that you are part of a larger community, a community that must remember its past to build its future. In legacy, there is caring combined with conscience, and wisdom to be found in one another.

Jason Cerin is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in International Relations (Global Business). He is the Co-Founder and former Creative Director of Haute Magazine.

Tim Vo is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Law. He is also a Los Angeles-based photographer who specializes in fashion and editorial photography.

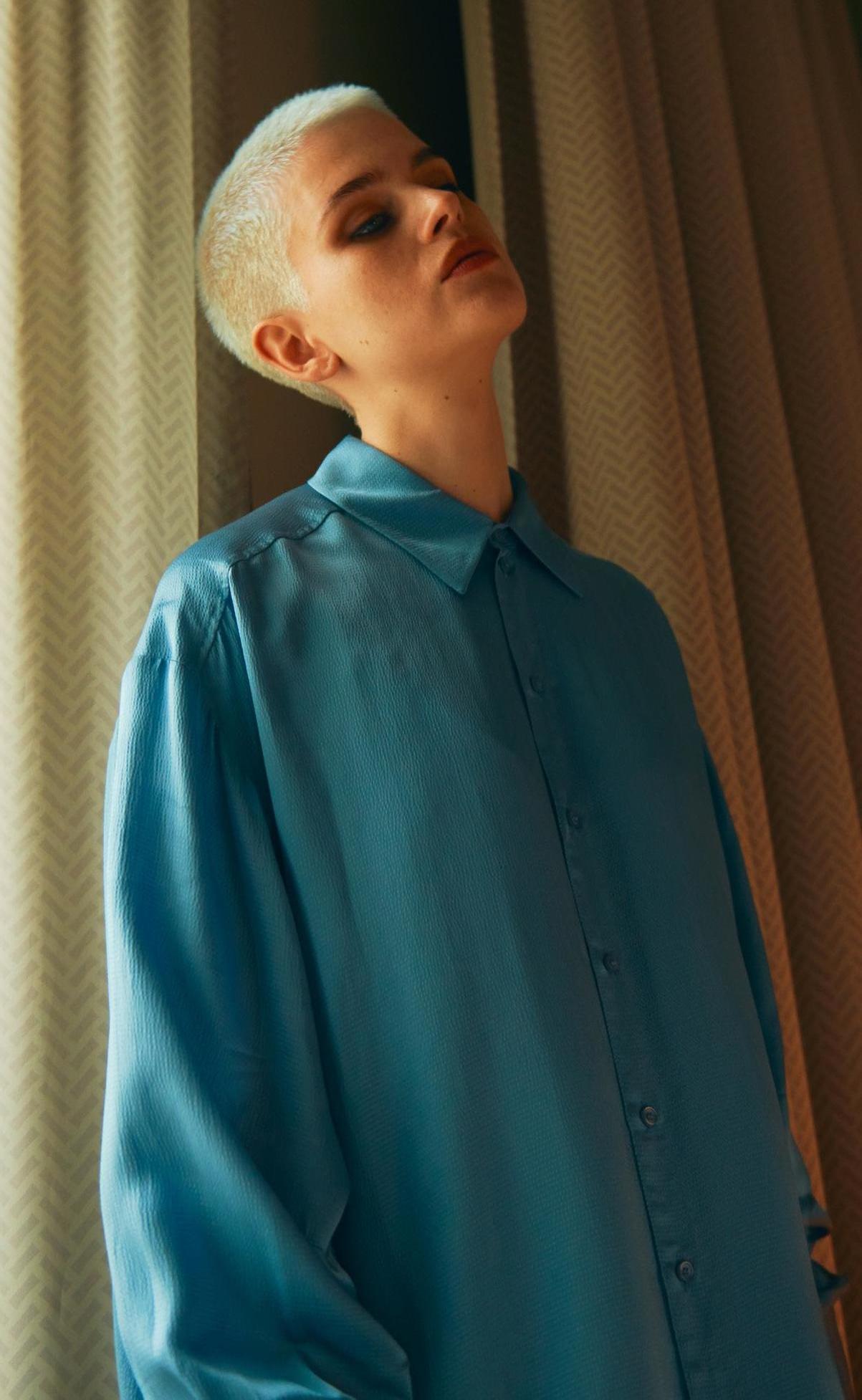

Photography by Johan Wennerström

Photography by Johan Wennerström

Cajsa Wessberg

Johanna Nordlander

Nobis Hotel Stockholm Falsett Rental

Johan Wennerström is a Stockholm based photographer whose work ‘conveys calmness, vastness, and a dreaminess only found in the northern latitudes.’

The very first time that I logged onto Tumblr, I immediately knew I was on a different kind of platform. I’d spent the first half of my freshman year of high school using little more than Adderall, Arctic Monkeys and the first four seasons of “Skins” to keep myself going, and I was in desperate search of an online platform where little to no aspect of my regular life had to be relevant. In 2014, Tumblr fit the bill: The website had already gained a reputation for being unapologetically uncensored, having a blog for any given niche interest and serving as a home for imaginative introverts instead of aspiring internet celebrities. It wasn’t long before the site became my designated space of refuge.

Founded in 2006 by David Karp, Tumblr was intended to be a social platform dedicated entirely to microblogging — the act of creating a blog in a more condensed form, with shorter text posts and smaller images than would be found on a traditional blog. The website quickly gained traction, growing to host over 100 million blogs within the year of its founding and eventually being bought by Yahoo, Inc. in 2013. The platform stood out from other leading social networks in three notable ways, the first being users’ ability to create content through a variety of mediums. While Instagram and Twitter users had to resort to photos and brief captions, the microblog format of Tumblr enabled users to share music, videos, art, photography and text posts that well exceeded 140 characters.

The lack of censorship on Tumblr posts was another draw, albeit a controversial one. There were several spaces on Tumblr dedicated to aspects of one’s lifestyle that they couldn’t share in their personal or professional life. Tumblr became a hub for these communities to thrive, due to its lack of censorship and its third key differentiator: anonymity. Instagram has always been a platform where one can curate their real life, and Twitter as one where people can quickly share what is on their minds and stay updated on current events. However, users on both platforms are likely to reveal at least basic aspects of their outside life and identity on the networks. On Tumblr, most people keep their blogs anonymous, and the ones who don’t are far more likely to gain attention for what they create rather than for who they appear to be.

“No one becomes a celebrity off of Tumblr anymore,” says Andra Mide, an artist and long-time Tumblr user from Los Angeles. “And even if you did, like in 2014, you’re kind of lost in the internet history archives.”

Mide initially became drawn to the fandom side of Tumblr but stayed on even as their interests evolved. Now at 21, they’ve had numerous side blogs with themes ranging anywhere from Korean fashion trends to classic textpost humor. “[My blogs] were whatever my interests became,” they say. “That’s the beauty of Tumblr, it enables you to do whatever you want.” Like Mide, many users felt that the element of anonymity liberated them to be whoever they wanted rather than pressuring them to adhere to a certain persona. There was no emphasis placed on the importance of celebrity and most high-profile celebrities barely bothered interacting with Tumblr’s online community. As a result, users were free to create online worlds of their own without holding back anything about themselves.

When I joined them, I discovered the extent of what could be accomplished in a Tumblr community. Having always used the creative arts as my primary tool for escape, I now had an area in which I could keep all of my artistic interests in a single place. My Tumblr blog was an independent space that I would venture to when I needed a reminder that there was more to life than my daily surroundings and routine could allow for. In this world, I was not only able to keep track of the music, literature and movies that were pulling me through high school, but I was also able to discover people from all over the world who shared my tastes.

I never had many internet friends, nor did I end up making any on Tumblr, but I did discover a new kind of dynamic in having “mutuals.” While I rarely interacted with the people I followed and who followed me, I still felt a sense of connection to them through their posts about the passions we shared. This was, in large part, due to the anonymity of the site that allowed us to shed the filtered images of ourselves and instead reveal the parts of ourselves that longed to be seen the most. I saw each post as if it had come from a peer, a friend. We were all on the same platform looking for a distraction or sense of relief in our daily lives, and we were allowed to be authentic strangers.

The sense of community to be found on the website was what kept users loyal to the platform for so long. However, the latter half of the decade would soon see a significant shift in how users of online spaces interacted with each other. Beginning with the buildup to the 2016 presidential election, communication on the platform came to focus prominently on the topics of politics and social justice. More attention was being devoted to topics of race, gender and intersectionality than ever before on the

website, and this led to an increasing presence of online communities from all sides of the political spectrum. As a result, the latter half of the 2010s saw a rise in communities that were dedicated to feminism, racial justice, queer rights, education on intersectionality and more. However, the platform also became a hub for far-right groups such as white nationalists and trans-exclusive radical feminists to congregate. This led to increased tensions among communities on the website, with practices such as doxing — publishing private or identifying information about an individual online — becoming commonplace.

Further controversy occurred when the website announced that it would no longer allow adult content, one of the things it was most known for, to be posted. The general response was not a favorable one, as the platform’s minimal censorship had been a draw to many of its users and allowed it to stand out from other social platforms. The adult community on Tumblr had been home to many groups who did not have another place to openly express that aspect of their lives, notably the LGBTQ+ and BDSM communities. The ban, particularly its focus on “female-presenting nipples,” was also seen as an unnecessary and objectifying attack on bodies that had been assigned female at birth. As a result, the platform lost nearly one-third of its users. Mide cites this ban as an instigator of the platform’s transition into the “dead” era.

“A lot of people left the website,” they recall. “Not just because of the ban, but because there was no one on it anymore. … They just kind of left because there was no audience.”

queer spaces that first drew me to the platform and figured I was growing out of the site. Doing so, however, proved to have a much greater impact on my life than I ever predicted. I spent much of my adolescence on Tumblr, gaining an understanding of who I was to a degree that I couldn’t quite do at home or at school. Tumblr was the first place I went to when I discovered that I was bisexual, and later non-binary. Tumblr was the first place I ever explored where mental health was discussed openly and where political discourse was encouraged rather than avoided. It was through Tumblr that I unexpectedly discovered more about myself and the world around me than I did in most other areas of my life. In leaving behind Tumblr, I inadvertently left behind parts of me that I hadn’t often, if ever, revealed elsewhere.

This changed when I was hit by one of the most abrupt global incidents to ever occur in my lifetime: the COVID-19 pandemic. When I found myself in the confines of quarantine that closely mirrored my entrapping and isolating daily life during my adolescence, I subsequently found myself gravitating back towards the platform that I had always been able to escape to. When I opened the app for the first time in almost a year, I was hit with a string of timely memes that seemed to reflect the current mental state of the general public, as well as a genuine lament over the toll that grief and isolation had come to take on our lives. What was missing, however, were the textposts that feigned positivity or videos of people outright ignoring the rules of quarantine, something that seemed to be commonplace on Instagram. When I continued scrolling, I found that the online community — while significantly smaller — was still finding sanctuary through shared interests.

“I feel like I know them,” says Mide about their current group of online mutuals. “I feel like I’m friends with them. … We’ve never talked before, but we’re friends. We get each other. We like each other’s best posts. Like, I know they’ve got my back on the Tumblr-sphere.”

The site might have fallen into obscurity since the 2018 ban, but a quiet but active community continues to thrive within that obscurity. In fact, it may be the growing distance between Tumblr and mainstream culture that allows users to be far more candid than they would ever be on another site. I, for one, have felt less alone on Tumblr than I have on any other platform since the pandemic began. In doing so, I’ve realized that Instagram and Twitter have always enabled me to project an idealized image of who I am, but Tumblr continues to be the only online platform where I might be able to express some of the most authentic parts of myself. Tumblr may not be considered a “social platform” in the term’s traditional sense, but the sense of solidarity to be found on it makes it one of the only platforms where the term “social” might feel truly fitting.

Annabel Haddad is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in English (Creative Writing). They are the Director of Diversity and Inclusion for Haute Magazine.

Perianne Caron is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in Communication. She is a Co-Director of Content for Haute Magazine.

Photography by Elle-May Leckenby

Photography by Elle-May Leckenby

Elle-May is a photographer and designer for “1924US” whose work in collaboration with her husband, Christian, tells the stories of their lives and passions.

Models

Christian

Elle-May Leckenby

Writing by Diego Frankel

Photography by Jacob Yeh

Writing by Diego Frankel

Photography by Jacob Yeh

The city of Los Angeles is a unique dream, one that tramples over the city’s previous lives. Today, LA is praised as a cultural melting pot, boasting a variety of ethnic enclaves ranging from Little Armenia to El Salvador Corridor. But what is now the incredibly diverse world capital of media was built by forcibly, violently removing a population from the land and narrative of American triumph.

The Tongva are the original inhabitants of the Los Angeles basin. Their words appear on maps – Topanga, Cucamonga, Cahuenga – but their cultural presence is largely erased from public memory. Yet in the face of the erasure, there are many Tongva descendents reclaiming their narrative, searching through a sea of records to confirm their heritage, and reviving old practices.

Josh Andujo works for numerous organizations: a veteran-owned coffee company, another that takes low-income kids backpacking and hiking, and one where he teaches firearm safety on weekends.

Growing up, he wasn’t very concerned with his cultural identity. “I always identified as American,” he said. Some of his family would have said Mexican or Chicano, but Andujo understands that his family didn’t move – the borders did.

“We’ve always been in Montebello,” Andujo said. His family worked in the brick and oil industries that dominated the area even before the city was incorporated in 1920. Andujo’s great grandparents formed and played for the first Hispanic baseball and softball teams in Montebello. They also helped desegregate some of Montebello’s public spaces, advocating to allow Hispanic and Black people into the public pool every day of the week rather than a designated Monday, known as ‘Mexican Day.’

Still residing in Montebello, Andujo said he feels a strong connection to his home.

The first and last time he heard about Native Americans in school was in fourth grade when he did a project on the Spanish missions. It wasn’t until 2016, when Andujo was 22, that he learned about his Indigenous ancestry.

He found out as his paternal grandmother was dying. Toward the end of her life, she started to lose her mental faculties — among them, the ability to speak English and Spanish. Instead, she started communicating through a strange combination of sounds. “We thought she was losing it,” Andujo said, but then his aunt stepped in and told him that she was speaking Apache. He ominously mentioned that her husband, Josh’s grandfather, “didn’t want her speaking the language.”

Andujo started asking questions, and found out that his father’s side of the family was Chiricahua Apache, from the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona. Later, he was able to trace his heritage to the Bedonkohe band and found that some of his ancestors rode alongside Geronimo (a famous Apache warrior from the Apache-US conflicts in the mid to late 1800s). On his mother’s side, nobody said more than “we’re L.A Indian” until Andujo got to speak with his grandmother’s cousin, who started telling him more of his Tongva history.

In 2018, Josh attended Moompetam, an annual event at the Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific celebrating California’s Indigenous maritime cultures (Moompetam means ‘People of the Saltwater’ in Tongva). There, he met his future mentor who advised him that if he wanted to join the tribe, he would need to show proof of “anything that’s going to trace back to the San Gabriel Mission.”

There, he met his future mentor who explained to him the process of joining the tribe, which is intimately tied to ancestral suffering. Andujo had to show proof of “anything that’s going to trace back to the San Gabriel Mission.” Baptismal records are the most common, as they document Tongva who were connected to the Mission and stand as testimony to the violence they were subjected to.

With the help of his grandmother’s cousin, Josh searched through the Gabrieleño Mission’s archives, now held and digitized through the Huntington Library, to find records of his family.

Andujo struck gold. He was able to quickly find evidence of his family that traced back to not only the San Gabriel Mission, but his ancestral village. He now knows his family came from the village Shevaanga, located in what is today Montebello. He was also able to find his family names before they were given the name Contreras.

Three years later, Andujo is now a tribal dancer and constantly learning more about Tongva culture. Other tribe members have told him he’s a rising star, confirmed by the significance of his naming ceremony. He was given the name Strong Standing Oak. For the Tongva, the oak tree symbolizes strength and survival due to its ability to survive tough conditions. Oak trees provide food and shelter, both of which Andujo also provides for his family. In addition to the name, he spoke to how impactful the ceremony had been for him.

It was back in June of 2020, a few months into the pandemic. Andujo knew the ceremony would be small, and the few tribe members who would attend and perform the ceremony told him to meet them at a house he visited regularly for trainings. When he arrived, they told him they were going into the mountains. Traditionally, the Tongva had held their naming ceremonies in the mountains, but were forced to stop by the Spanish in the 1700s. Andujo’s was the first naming ceremony held there in over 300 years. ‘How do you feel?’ they asked him afterward. “I feel good. I feel accepted. I feel, I feel Tongva now,” he responded.

The other tribe members have told Andujo he’s incredibly lucky to have traced his lineage in such a short amount of time. Many of the elders who have been researching their family’s histories for much longer haven’t been able to find their village. “I still haven’t even met anyone who descends from my village either,” Andujo said. A lot of people are actually surprised that he is from Shevaanga since it’s so close to the original San Gabriel mission, the Mission Vieja. “Not many made it out,” he said.

There are a lot of remarkable things about Andujo’s story, but many are common within the community. Like Andujo, many Tongva have submerged their identities under Chicanx or Latinx, as previous generations mixed and found it less burdensome to assimilate.

Another Tongva tribe member, Julia Bogany, said “it skips a generation.” It was her grandmother who got her a Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) card when Bogany was born in Santa Monica in 1948. The BIA is a federal agency responsible for laws and policies related to Native Americans, including providing funds for healthcare, housing, food, and education to federally recognized, card-holding Native Americans in need. Two years later, her grandmother passed away, and eleven years after that, when she was 13, Bogany’s mother handed her a BIA card.

Bogany said she probably would have identified as Chicana growing up, though she didn’t give it much thought. Her mother was Tongva and Acjachemen (a tribe from the San Diego area), and her dad was “Azteca and Spaniard.”

Bogany’s father once tried to sever her legal ties to the Tongva tribe. Bogany believes he was motivated more by internal family arguments rather than a broader anti-Native sentiment, but even so, it fits a trend of Tongva identities being made invisible. Without telling Bogany, her father went directly to the Tongva chief to ask that she be unenrolled from the tribe. She expressed a sense of conflict, knowing that her father knew more about her heritage than he let on. He knew who her chief was, “but it’s not something they told you,” she explains. Fortunately for Bogany, the chief refused.

Bogany was raised Catholic but doesn’t identify as Catholic. In Catholic school, she said she was disappointed in how local history was presented. “When I was in Catholic school we didn’t learn about the missions. We learned about the crusades,” she said. “My ancestors died building those missions.”

Today, Bogany is the cultural consultant for the Tongva tribe and sits on the tribal council. She maintains a website (tobevisible.org) and does an impressive range of other jobs ranging from sitting in on federal negotiations around Indian Health (specifically child welfare and mental health) to teaching the Tongva language and crafts such as basket weaving and soap stone carving, to supervising doctoral theses in the greater LA area. Bogany’s website says that “her calendar is a full year ahead of time.”

Bogany also maintains a close relationship with the San Gabriel Mission and often gives talks there to discuss the genocide that happened there, though today’s mission is actually a few miles away from the original one that was built near Andujo’s ancestral village. That one sat on the bank of the LA River, but was damaged by flooding around 250 years ago and relocated to where it sits today.

Bogany also works with priests at the Mission, in a surprisingly fruitful relationship. “[They] say ‘we’re happy you’re not angry.’ I’m not, because it’s a healing process,” she said, demonstrating an incredible capacity for compassion.

It wasn’t an easy or fast journey, though. Bogany has been working as the tribe’s cultural consultant for thirty four years, ever since she joined the tribe in 1987. She was 39 when she decided to attend a Tongva tribe meeting at La Casa– a church, Catholic school and community center in San Gabriel. When she arrived, she opened a door that set off a fire alarm. “I don’t know who you are but you made a grand entrance,” a tribe member later told her. But the day was marked by joy, not embarrassment. “All of a sudden from having just me and my children. ... I had like 300 cousins in one day,” she said. One of those cousins is now Andujo, though they refer to each other as aunt and nephew.

Bogany took on the role of cultural consultant shortly after she joined the tribe. “I started buying, like, every book that had the word ‘Tongva.’ Sometimes it was just a word on a map,” she said, laughing. She started working in universities, including USC, creating presentations on Tongva history, which she still gives today.

Bogany also spoke on the interesting relationship between the Tongva and other Native Americans that were brought to L.A. Most came in the 1950s, as the result of a program known as ‘Relocation,’ which involved the Bureau of Indian Affairs relocating Native Americans away from their tribal lands and integrating them into urban environments. This policy culminated in the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, which freighted Native Americans into urban centers, away from their reservations or tribal lands in an attempt to assimilate them into American life and erase their cultures.

The Native Americans who were brought to Los Angeles “don’t know we’re here,” Bogany said, “because they’re thinking they’re coming to the promised land and, [there] couldn’t be no Indians there because they’re bringing us.” Additionally, like Bogany’s, Tongva identities at this point had largely been submerged under Chicanx identities. This was just one of the ways Bogany said Tongva people felt invisible.

Five years ago, Bogany’s great granddaughter asked her what it felt like to be a Tongva woman. Bogany replied, “I feel invisible.” Even at 10 years old, her great granddaughter was taken aback. “That’s how I feel,” she said. Now, Bogany laughs at the “trouble” her daughter causes, fully aware of and vocal about her Tongva roots. “Now your job,” Bogany tells her, “is to teach the next seven generations.”

Bogany also works with Indian Health in a few different capacities. “I sit on the roundtable for ICWA [Indian Child Welfare Act] in children’s court in Los Angeles.” She said it’s important to just have another Native voice supporting the children. She wrote and now teaches the curriculum at Riverside San Bernardino Indian Health on mental health for Native Americans.

“Maybe we didn’t all deal with the same things, but there’s issues down deeper. There’s trauma that’s been going on for years,” Bogany said. She wants social workers to understand the traumas that Native Americans especially deal with.

Bogany also strives to create more room for Tongva youth in higher education systems. When a young Tongva member asked if college was for them, she replied, “As long as my foot’s in the door, it’s for you.”

To complete her already bursting resume, Bogany said she “still [researches] everything under the sun.” She’s constantly creating new presentations, and one of her latest projects is a book on important Tongva women. Among them is Azusa, a Tongva healer for whom Bogany was trying to find more sources, but kept hitting a wall. Eventually, someone came to one of Bogany’s book signings and told her he didn’t know why, but he felt he had to come see her. He flipped through the pages and saw Azusa, solving the riddle for Bogany. He pointed her to sources on a woman named “Blessed Miracle,” the translation of “Azusa.”

The other women in the book include the L.A. Water Woman, the first Tongva woman to work for the LA Department of Water and Power DWP — you can find her statue on the Gold Line, Lincoln Heights/Cypress Park station — and the La Brea Tar Pit Woman, a partial skeleton recovered in 1914 whose digital reimaginings startled Julia, who pulled up an image of her daughter. “They look exactly alike!” Bogany said.

The work that Bogany does is nothing short of amazing. Her work, as she is happy to tell you, is and has always been rooted in love. Not only for her family or for Tongva people, but for everyone. Her compassion and motivation are infectious– a quality you want from someone at the forefront of the discussion on how to move forward while acknowledging our past.

Bogany didn’t completely transition away from Christianity though. While Andujo had grown disillusioned with the church, Bogany became a Pentacostal minister.

Again fighting any one-dimensional characterizations of her narrative, Bogany offered a piece of wisdom. “History happens to all of us,” she said smiling, reclining in her desk chair, settling into comfort in the presence of conflict.

Diego Frankel is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in Computational Linguistics.

Jacob Yeh is an Pasadena-born and Los Angeles-based photographer who specializes in portraiture and abstract photography. He enjoys cinema, music, and most recently, cooking. Jacob studies Communications and minors in Cinematic Arts and Media Studies at the University of Southern California.

Photographer

Tina Sosna

Assistant Photographer

Florian Hagenbring

Models

Maren Büttner

Tina Sosna

Tina Sosna is a Germany-based photographer who specializes in self-portrait and landscape photography. Her work is about finding the beauty in our everyday life and conserving it.

Some betrayals cut so deep there aren’t words to encapsulate the grief. It’s more easily explained through moments: moments so unbearably tragic, so indescribably harrowing, you genuinely aren’t sure if you will live to see another day of sunlight. You don’t believe that you will ever feel beyond anguish.

When I was nine years old, I celebrated Halloween in a hot pink flapper dress complete with a pair of black satin gloves and a sequined feathered headpiece. It was my favorite costume I ever wore. My parents decorated our lawn as an elaborate graveyard concealed by fog machines while orange and purple string lights wrapped around the pillars of the front porch. I filled a pillowcase with candies collected from neighbors and traded Reese’s for Twix and Kit Kats for Skittles on the landing outside my bedroom door with some kids from school. While I’d known him since the first grade, that night was the first time I’d ever spoken to [REDACTED] and spent time with him outside of a classroom. It wasn’t until years later that we truly became friends under the rosy glow of the summer sun and idle mischief at the childhood home of Laurel Acosta — Fairdale, we called it. Drunk on daiquiris and the innocence of youth, we spent the summer before senior year lounging on the pool deck, taking the train to the city for exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art, and making family of whoever was around. Laurel and I, alongside our actress friend Gwen, had bonded the previous academic year through our mutual involvement in high school drama (with a capital D). We grew our squad — as Laurel’s mother Joanne aptly called us — through theatrical affiliations and old friends. I began a brief affair with Seth Gerber, an extremely tall and extremely immodest pal from Laurel’s past, that came and went with the season. My friends would hop into the backseat of my ‘97 Wrangler while I drove to watch the sunset over the Golden Gate behind the glittering night of the San Francisco skyline — windswept as we soared across the bridge, The Beatles poured through the crackling car speakers as we belted along: “are you sad because you’re on your own?... No, I get by with a little help from my friends.”

We graduated the following May, and though we all went our separate ways we remained tied together through juvenescence and its strings of naivete. That first Thanksgiving we returned to Fairdale, reunited for a last hurrah at the house we all made a home of in our indulgent nights of high school cliche. We toasted: “To the family we chose.” As we grew older, and others grew apart, something about us was timelessly intertwined. We loved

each other too much to ever let our family go. So as another year came and went, we once again found ourselves reconvened, this time at Joanne’s notably smaller apartment one town over. That November we gathered in our old prom dresses and tuxedos, playing dress up from easier days long lost to the interminability of existence. We drank heartily and danced even moreso, as though we all knew it was the last night we would ever be together. The minutes ticked on and we eventually fell victim to drowsiness. I swapped my ball gown for a sparkly unicorn onesie. Laurel took the top bunk while [REDACTED] and I shared the bottom. His eyes met mine.

“Do you want to cuddle?”

“No.”

I turned over and went to bed.

At three in the morning I awoke to find his arms wrapped around me, stuck in a spooning chokehold that I verbally rejected. Still, I thought nothing of it. He must have done this in his sleep. I removed his grasp from my body, rolled him back to his side of the bed, and fell asleep once more. It wasn’t for another two months that I became aware of the full extent of what happened to me. It took something far more heinous for the reality of my situation to dawn. To think of it is reviling. To try to envision it is unthinkable. But the rage came to fruition in the dark January evening when Gwen and I went to a Goodwill to buy cheap, breakable items we beat up in the woods with baseball bats. Screaming. Trying desperately to free ourselves of strangling despair. [REDACTED] molested her too. Only she was awake.

His fatal flaw was attempting damage control. The morning after he violated me, he spoke with Seth: “CJ must have been pretty drunk last night because she kept putting my hands on her boobs while she slept.” The morning after he violated Gwen, he spoke with Laurel: “Gwen must have been pretty drunk last night because she kept putting my hands on her boobs while she slept.” With our revelations came Laurel’s, whose own repressed memories emerged with our trauma to a night he had done the same to her two years prior. She told me later, “I didn’t think anything of it. He was just sleeping.”

When you love someone so much that, even in lieu of blood bonds, you still refer to them as family, trust is unyielding. You don’t excuse red flags because you don’t even see them. But then comes the crashing wave of gut-wrenching treachery and remembrances reemerge from the shadows of subconscious.

It wasn’t an accident. He didn’t roll over in his sleep and land on top of me. To know a deception so disfiguring is deathlike. I thought I knew pain before this; I thought I knew suffering. But I was only a child living in a dreamlike state of idle credulity. My friends were my family, that was something I once believed to be not an idea but a fact of being — like the blueness of the sky or the intangibility of faith. Before, I believed in the goodness of others. I believed that people were made to have benevolent intentions but were corrupted by the evils of the world. But [REDACTED] was not made evil: he was born vile. And he robbed me of hope.

To be assaulted may as well be a woman’s rite of passage. I was in eighth grade when someone told me one in six women will be sexually assaulted in their lives. At the time I thought that was some kind of sick exaggeration. I was still young enough to think it inconceivable. But a few months later a friend of mine was raped for the first time. She was only thirteen. The following years saw every woman in my life become a statistic. One by one, they fell like dominoes. It became a question not of if it would happen to me, but when.

I thought that it would be in a frat basement at half passed midnight, or in the grimy underbelly of some European club I would stumble upon in a daze of adolescent impropriety, or, perhaps, in the alley behind my South LA apartment. I like to wear mini skirts and high heels, the sorts of garments they say attract assault, so I carry a can of pepper spray and the shiny pink Smith & Wesson blade my father bought me in a desperate attempt to protect against the inevitable. I often keep the knife open in my pocket, gripping so tightly my knuckles turn white as I walk darkened streets. But I never thought to bring it to bed with me, to sleep next to a friend I’d known almost as long as I’d been alive. Dressed in a sparkly pink onesie with a shiny rainbow tail.

I returned to Los Angeles in a matter of days as a broken version of the girl I used to be. Nights fell, mornings dawned, time ticked on — and as it went,

so did I, becoming less of a person and more of one’s shadow. I filled my schedule excessively to avoid confronting the reality of my loss. Not only of a friend, but also of myself and everything I once believed in. Stuck in traffic on the 405 I found myself screaming, banging my head against the steering wheel, desperate for a reprieve from agony. I left mascara-stained teardrops on all the furniture in my apartment, sometimes escaping to the porch stoop to smoke a cigarette in the hopes it would burn away the anguish. Still, I carried on: school, work, making movies — distractions to quell the heartache. The only times I didn’t suffer were the times I was too busy to allow it. But then the world fell apart as an unknown virus ravaged the globe. The university sent us packing.

Everyone else lost sophomore year. I lost my sanity.

Quarantining at the scene of the crime, I saw [REDACTED] everywhere I looked. He was on the edge of my bed when I tried to sleep at night, talking to me about Randy Newman’s scoring just as he had three months prior. He was in my yard sharing White Claws and laughter. He was on the landing trading Halloween candies with the nine year old version of myself. I couldn’t be in the house without being encompassed by rage — but I couldn’t leave the house at all. So I sat in silence and watched the world burn as I became more and more infested with unflinching despair.

My family was forced to watch me disintegrate. They stood over my heaving body as I sobbed on the kitchen floor unable to move. They witnessed the blood drip from my knuckles as I released rage upon my own body. They saw me starve, slowly, as weight shed from my already dainty frame.

One night I collapsed in the dirt of the lime trees, pulsating, screaming at my mother that I wanted to see him suffer; I wanted to see him bleed. My parents tried to empathize, telling me stories of their own pain to help me feel less alone — but it only made me worse. Knowing the wickedness of humanity transcended what already consumed me. Knowing that inane agony is the only universal truth. Knowing my faith in integrity dissipated alongside my idealism.

On December 20, 2019 I texted [REDACTED] asking him to drive me home from a friend’s birthday party.

ME: Ok could you swoop? Perchance? [REDACTED]: Yee I’ll leave in a min ME: I love you

By that time he already assaulted me — I just didn’t know it yet. We drove around town for a while talking about everything and nothing. Dreams for the future, aspirations regarding lives neither of us will ever live. It was the last time I remember seeing him. These were the last texts we exchanged. I never confronted him and he never contacted me. A silence so loud it could break glass.

Today I live in a stasis. I once found meaning in love for those around me; now, I find meaning in impermanence. Every moment of existence is fleeting. Every person you know and love with a deepness that seems inexorable will someday no longer breathe in flesh but only memory. Only once my innocence left me did I realize I still had it. I know now to nurture what I can’t afford to lose.

My year was spent recovering from emotional holocaust, and though there were times I genuinely wasn’t sure that I would, I survived. The three of us survived.

To Gwen & Laurel — the family I chose.

Sofie Sund is a photographer based in Trondheim, Norway. Her work features vibrant self portraits to express herself.

Courtney J Dowling is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a major in Cinema and Media Studies.

Maria Eberhart

Maria Eberhart

Maria Eberhart is a Baltimore-born and Los Angeles-based photographer who specializes in film photography. She enjoys going to see local bands and writing poetry. Maria studies journalism at the University of Southern California.

Photographer Maria Eberhart

Models

Rachel Chioke

Gianna Verga

Photographer Maria Eberhart

Models

Rachel Chioke

Gianna Verga

Alex Lam is an Saigonborn and Los-Angelesbased photographer who specializes in portrait photography. She enjoys listening to Ariana Grande and watching New Girl. Alex studies Environmental Science and Economics at the University of Southern California.

Model Emily Nguyen 126

Model Emily Nguyen 126

In 2011, Obie Steven Anthony was exonerated after serving 16 years in the California prison system for a crime that he did not commit. Anthony, who was 19-years-old at the time he was convicted, was charged with murder with three counts of robbery as well as attempted murder. Although he was not at the crime scene and there was no evidence linking him to the crime, the use of official misconduct, mistaken identification, and informant testimony all played a role in Anthony’s wrongful conviction.

Before Anthony was unfairly convicted of these crimes, he was a high school student in South Central Los Angeles, contemplating different career paths under the care of his mother. He was considering furthering his education to work in the dental field, and after working with the California Conservation Corps under the Department of Forestry, he aspired to become a firefighter.

However, witnessing police tension and abuse of power in his community from a young age caused Anthony to experience a lot of external and internal conflict. At the time of Anthony’s conviction, two detectives intentionally engaged in misconduct to frame him for the crime so that he would go to prison. The prosecution also used the testimony of a known murderer and snitch and the identification of a man who frequently changed his story.

“I was totally shocked. I had no idea, I didn’t even know how to do murder. I didn’t even know where it happened. I didn’t even know anything. I just knew that I was being charged.” Anthony said.

Since 1989, there have been 2,720 exonerations of innocent people from prisons and death row. According to Jonathan Delman, a USC alum from Long Island, New York who is currently studying law at the Cardozo School of Law with the Innocence Project, an exoneration

occurs when someone has been convicted for a crime that they did not commit and is released from prison short of their term because their innocence has been proven. To combat this, the Innocence Project works to free innocent people from prison and reform the criminal justice systems to prevent and encourage accountability on wrongful convictions.

According to Delman, the Innocence Project has a team of social workers that helps exonerees through their transition process, in anticipation that many will encounter issues finding jobs, housing, and navigating technology. Additionally, there are 35 states that offer monetary compensation to exonerees, although statutes vary by constituency.

Common wrongful conviction causes include faulty forensic evidence, eyewitness misidentification, police or prosecutorial misconduct, false confessions and jailhouse informants. Race and socioeconomic status are also major factors in wrongful convictions, which can play into inadequate defense and jury bias, according to Delman.

“The image of Black people, particularly Black men behind bars, has just become so grossly standardized in our country … I think when grisly acts are committed like murders and rapes, the police, who in many jurisdictions are elected officials, feel pressure to put someone behind bars, even if they’re not sure who it is. They know that’s going to have to be done by a jury so they go after Black men. It’s a hard, disgusting fact,” Delman said.

Including Anthony’s case, half of all exonerations involve an innocent Black person. Although Black people make up only 13% of the population in the United States, they are far more represented in the carceral system than any other race.

With no criminal record or history in youth detention, Anthony found it difficult to adjust to life in prison, now living with men who had been incarcerated as long as he had been alive. Being illiterate, having no support, and grieving his mom that had recently passed away while he was incarcerated, Anthony said he had to keep a straight face and act as if he had been accustomed to it all.

It wasn’t until 2008 that the Northern California Innocence Project and the Loyola Marymount Law’s Project for the Innocent stepped in to help Anthony prove his innocence.

VICTORIA VALENZUELA + SARAH KIM

After three and a half years of fighting the case, the group of attorneys and college students was able to help Anthony win his freedom and be exonerated of all charges.

“You have no help. Your cries for help are a void because there is no one who’s going to help. You are left to help yourself out of a horrendous situation,” Anthony said.

Anthony compared being exonerated to falling off a boat and not knowing how to swim and then drowning but then being pulled up, gasping for air. He said that the feeling of knowing you almost drowned and the relief of finally being safe is similar to an exoneration.

After the 18 years Anthony spent wrongfully convicted, he faced many challenges adapting to life outside of prison. Being sentenced as a 19-year-old and exonerated at 37-years-old, Anthony felt like he grew up in prison. When he had come out of prison, he noticed more diversity and interracial relationships than before his incarceration in the early 1990s; he also had to adjust from the typical male-to-male dominant, controlling conversations he ex-

perienced in prison. Additionally, Anthony had to learn how to use the many technological advance ments that came out in the 2000s — like not knowing how to take a photo with a phone.

Although Anthony was able to live with his fiance after his ex oneration, he still struggled to find a job and to acquire a Cali fornia state ID and Social Secu rity Card, which are disposed of after 10 years of inactivity. After sharing his story with California legislators when originally advo cating against prosecutorial mis conduct, Anthony inspired Obie’s Law, a law put in place to provide wrongfully convicted people with reintegration resources following their exoneration.

In 2015, Anthony founded Exon erated Nation to create a plat form for exonerees from all over the country to come together and help each other heal from the de bilitating effects of being put in prison for crimes in which they didn’t commit.

“All of us, even though we have been proven innocent of the crime, still have the stigma of being in prison and being removed from the community. When we go ap ply for a job, and we go try to get an apartment, we have no rental history, we have no work history.

It makes it very difficult for em

ployers [to employ us] and renters to rent to us, even though they are very sympathetic to the situation that we’ve been through,”

Before Gloria Killian was wrongfully convicted in 1986, she was in law school with aspirations to work in estates and trust legality. Similar to Anthony’s case, Killian’s conviction involved misconduct and relied heavily on the testimony of another person being tried for the same case, yet was given a reduced sentence for naming Killian. With the case Killian was charged for involving murder and conspiracy, she was sentenced to 32 years to life in prison. She served 10 years of the sentence before filing a writ of habeas and being exonerated by a private lawyer after they were able to dethe testimony of the co-defendant who had claimed Killian was the leader of Killian was exonerated in March 2002, and was finally released from prison in August 2002. After Anthony was exonerated, the two met in Northern California and began working together to see how Exonerated Nation could best help exonerees.

Outside of Exonerated Nation, Killian also helps currently incarcerated men and women work on

their cases while they are in prison. She is also very active at USC, having been an important figure in the founding the USC Law Project at the California Institution for Women.

“Incarcerated men and women are no different from you and I. They are not some strange, evil people that came from somewhere. They are exactly us, and fact is, anybody can get into trouble, have problems, or have a bad time,” Killian said.

Zavion Johnson, the eldest of seven children raised in Northern California, was 18-years-old when he was sentenced to two life sentences after being wrongfully charged for murder. Johnson aspired to be a train conductor after seeing the travel and money that his uncle’s friend was able to make in the industry. However, after a tragic day in which Johnson’s baby daughter had slipped and hit her head on the bath and died, officials suspected the child suffered from shaken baby syndrome and arrested Johnson on the day of his daughter’s funeral.

Johnson said that knowing he was innocent and having faith in God kept him fighting for the 16 years and four days that

he was kept in prison. In 2014, Johnson received a letter from the Northern California Innocence Project that his case was in circulation, and in 2015 he was able to meet with his new legal counsel. On the day that Johnson was ex onerated, he walked out of the courtroom in a paper suit with no money, clothes, bus ticket or apology. Since then, he said his six attorneys have become his friends and like his family. His first meal post-conviction was Popeye’s chicken and a strawberry soda.

“I look up and it’s 2016, and there are six different people that I had the opportunity to meet who are a part of my team. Work was al ready being done. I still don’t really don’t understand the dynamics of how and when I would come home, but just to have all these peo ple invested in me, I knew that I was coming home,” Johnson said.

Johnson said he feels that he was kidnapped on his way to college, as he was only 18-years-old when he was convicted. Now, Johnson works with Exonerated Nation and speaks at different universities to raise awareness about wrongful convictions.

Anthony, Johnson, Killian and Delman all seem to agree on what needs to be done to prevent wrongful convictions from happen ing — accountability. Anthony believes that without accountability, the criminal justice system will continue to ignore procedures set in place. Delman actively supports laws that give defense attorneys greater access to files and put pressure on elected officials to pay attention and make the changes necessary.

“You need to have accountability within the system to have actual reform because accountability is performed,” Anthony said.

Victoria Valenzuela is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in Creative Writing.

Sarah Kim is a student at the University of Southern California currently pursuing a degree in Communication.

Niqfilms is an LA-based photographer who only shoots on film. He enjoys Djing Hip Hop and designing clothes. Niq studies entrepreneurship and multimedia at the University of Southern California.

146

Model Lilly Phillips

146

Model Lilly Phillips

Photography By Kellie

Photography By Kellie

Kellie Chen is an Bay Area-born and Bay Area-based photographer who specializes in portrait photography. She enjoy(s) painting, cooking, and baking. Kellie studies Communication at the University of Southern California.

152

Writing by Shay Martin-Jones

Photography by Kiera Smith

Writing by Shay Martin-Jones

Photography by Kiera Smith

In my story, it begins with people, with bodies, falling apart and building back together—a total reimagining, brought forth by inconceivable destruction of self-understanding and identity. In many Queer stories, it starts and ends like this: falling into ourselves over time, picking up pieces of our identity along the way and reshaping it at every rest stop. Self-reflection is perpetual.

Three years ago, I woke up from a dream and was infatuated with my best friend (which could be to say that I woke up from one dream and entered into another). I was 18, proudly bisexual, and caught in my own mind, which was somewhere out of this atmosphere, closer to the moon than the ground. It was the first time in my life I had ever considered myself to be romantically interested in a boy. Spending time with him made me warm, and I wanted to be as close to him as possible—romance was the normal next step, a way to level up the friendship, to immortalize it.

Of course I would have a crush on him, I thought, I want to be a part of his life for as long as possible; I want to spend my days talking, laughing and existing with him. A relationship would be so similar to our already growing and happy friendship but closer somehow.

In a way, this newfound crush felt safe to me. I could create an idealized future in my head in which I could have a long-term relationship with a man without having to interact with or pursue any strange ones. My best friend became a safety net, allowing me to conceptualize that I could achieve a domestic life with a man because this one was kind, loving and knew me well. I would not have to have sex with him because he was asexual, I would not have to fit the mold of “woman” perfectly because he was also Queer and would never dream of forcing me into it.

I thought it was ideal because I would, in practice, only have to be his friend but in a romantic way. There was always an undertone of discomfort in this infatuation that I could never quite place—an aversion to the reality outside of my world of daydreams. I knew, realistically, he would never reciprocate, and this fact made me feel even safer somehow. This was the basis of my first (and final) crush on a man.

My feelings for women came much earlier than that. At nine, I was already flirting with girls and playing house with them, kissing in secret. At 13, I had my first crush. It was passionate, charged, romantic—everything a barely teenaged Queer kid needed in a fling— and she lived approximately 3,800 miles away.

Before we ever dated, we spent years somewhere between friendship and romance; she sent me birthday cards with love letters and playlists inside, all sprayed with her perfume. When we began dating in my late teenage years, I sent her a map of the night sky of the day we met and clumsily written love poetry. Relationships with women have always felt natural to me—something gentle, endlessly romantic and dreamy. They are the only relationships I have actively, shamelessly pursued—even at the risk of writing embarrassingly cliche odes with badly translated Portuguese dying at the end of stanzas. Still, I left the door to my identity slightly ajar; men were an after-thought but a necessity, people I figured I would keep in my sexuality as a possibility but never a promise. Just in case.