edible INDY

Celebrating the Bounty of Bloomington, Carmel, Columbus, Indianapolis and Beyond

Pears

Cooking with Anthony Castonzo

Hoosier Shrimp Farms

Growing Hops

Eat. Drink. Read. Think.

Local. Issue Thirteen Fall 2014

Celebrating the Bounty of Bloomington, Carmel, Columbus, Indianapolis and Beyond

Cooking with Anthony Castonzo

Hoosier Shrimp Farms

Growing Hops

Eat. Drink. Read. Think.

Local. Issue Thirteen Fall 2014

We are so grateful for the support of the community over the last year. We celebrated our first year anniversary of owning Edible Indy earlier this month! Your support has helped us to grow and increase the awareness of the importance of supporting the local food movement. This issue is full of Hoosier Fall goodness and we do hope you will enjoy it with all of your heart.

We hired a new managing editor, Rachel D. Russell in August. You will hear more about her and from her in our winter issue. Give her a tweet to welcome her @rachelgetsindy. In addition, we were blessed to have three wonderfully talented interns this year who assisted in pulling this issue together with photography, writing and graphics. We thank them from the bottom of our heart for all of the hand and excellent work they contributed. Corttany, Kolton and Sofia- we wish you all the best in your future endeavors and hope you know you made the Edible Indy family even better!

Hoosier Hugs,

Jennifer & Jeff

We would like to share with you a letter from our intern, Corttany Brooks, who was our summer assistant managing editor.

The decision I made in high school to leave my home in central Indiana in pursuit of a higher education was not one taken lightly. So, when I had the opportunity to come back to my Hoosier state and intern at Edible Indy, I quite literally jumped (you can even ask my parents) at the chance. I was equal parts scared that my lack of professional writing skills wouldn’t be sufficient and excited to get a real learning experience in journalism. The first few weeks were a fish-out-of-water experience where I wasn’t fully sure what was going on. Fortunately, with the proper guidance from my boss and mentor Jennifer Rubenstein, these past twelve weeks have developed a passion in me, for this publication and everything we stand for.

These past few months have taught me how to persevere and develop a thicker skin when communicating with other people. I’ve learnt how much one can actually do when they stop hiding under their comfort zone and test their limits. This internship has been an invaluable experience. For anyone contemplating whether an internship is worth your time, I would say that it is. It’s much more than just work experience. School prepares you for the real world, but an internship is a chance for you to get a feel for the life you hope to be living one day.

Corttany Brooks

Subscribe now! Give the gift of Edible Indy to someone—even yourself—delivered right to your door! $32 for one year (four issues) or $52 for a twoyear subscription (eight issues). Subscribe online at EdibleIndy.com

publisher Rubenstein Hills LLC

editor in chief Jennifer Rubenstein

cfo Jeff Rubenstein

copy editor Doug Adrianson

designer Cheryl Angelina Koehler

web designer Mary Ogle

interns

Corttany Brooks, Assistant Managing Editor Kolton Dallas, Photography / Video Sofia Puga, Graphics

advertising

317.489.9194

jennifer@edibleindy.com

Please call or email to inquire about being a member of our advertising partnership and show your support for the local food culture in central Indiana.

contact us

Edible Indy PO Box 155

Zionsville, Indiana 46278

317.489.9194

info@edibleindy.com

Edible Indy is published quarterly (March, May, September and November). Distributed throughout central Indiana and by subscription elsewhere. Subscriptions are $32 for one year/four issues and can be purchased online at EdibleIndy.com or by check to the address above.

Every effort is made to avoid errors, misspellings and omissions. If, however, an error comes to your attention, then you probably have not had enough wine with your healthy food.* Please accept our sincere apologies and, if it’s important, please notify us! Thank you.

*Sarcastic copy courtesy of Edible Berkshires

No part of this publication may be used without written permission from the publisher. © 2014 all rights reserved.

Over the summer we partnered with Bloomingfoods in celebrating Central Indiana foods over instagram. Each of the winners received $75 from Bloomingfoods along with their photo printed on canvas and displayed in Bloomingfoods. There were over 300 entries. Congratulations to the top 5 winners.

Jessika

@Bloomingveg

Elisabeth Simeri

@elizabethsimeri

Christa Nimmer

@insatiableindiana

James Nimmer

@jamesnimmer

Cate Pickens

@catepickens

Shout out to other Instagram photos tagged with #hoosierfood.

Thank you and keep tagging #hoosierfood—you never know when the next contest will pop up!

Follow us on instagram @edibleindy

When our Summer issue came out, we asked you to join the conversation and share your Indiana food story by tagging us in your tweets, Facebook posts and Instagrams. Here’s how our readers have been enjoying #HoosierFood this summer.

@EskenaziHealth: What is your favorite farmers’ market in Central Indiana and why? Reply, and we’ll send you a FREE copy of @ EdibleIndy Magazine!

—Eskenazi Health, Jun 19

@CarlaKnapp: Got my @ EdibleIndy farmers market guide in hand & ready to go score some yummy local food finds! #eatlocal —Carla Knapp, Jul 19

@kibiorg: Check out the latest edition of @EdibleIndy for a super cool rundown of farmers markets!

—Keep Indianapolis Beautiful, Inc., Jul 8

@DistelrathFarms: @Yourlocal_deli + @DistelrathFarms means your greens only traveled 2 miles to reach your plate! Support #local! @EdibleIndy @ IndyMonthly

—Distelrath Farms, Jun 27

@e_tande: “@EdibleIndy: “Foodie”: Person who loves everything about food, consciously seeks out quality, consumes responsibly & shares the experience.

—E Tande, Jun 24

@edibleindyjenn: Hello @EdibleIndy Readers! I am the owner and publisher and if you ever want to reach out to me personally, HERE I AM!

—Jennifer Rubenstein, Jul 9

@Arts4LearningIN: Our friends at @EdibleIndy reached 2k followers! Haven’t hopped on board yet? Get your foodie fix; follow them now!

—Arts for Learning, Jun 19

@INhousePC: @EskenaziHealth @EdibleIndy Greenfield Farmers Market! All the fruits and vegetables are ripe and perfect every year! @HoosierHarvest

—INhouse Primary Care, Jun 19

@AarynNC: Yes! Love the mango ginger! RT @ EdibleIndy: Have you tried @ sagessyrup?

—Aaryn, Jun 12

@dctourismIN: @AroundIndy @EdibleIndy @IndianaFoodways Highpoint Orchard opens today for the season! #Yum #Homegrown —Greensburg Tourism, Jun 10

@dorothyhoffman: Why do I love #indiana? “within 100 miles of #Indy there are more than 250 farms and farm markets” @EdibleIndy @wfyi #slowfood #CSA #organic

—Dorothy Hoffman, Jul 30

@CaraDafforn: Grateful for @ EdibleIndy a local partner of #urelish Farm and @IndyCM

—U-Relish Farm LLC, Jun 5

@TAB5910: Beautiful morning at the @BRfarmersmarket. Picked up salad fixings, eggs & a copy of @EdibleIndy. Nice! —Tracy Barnhart, May 31

@iomphaloskepsis: Recognition welldeserved! It’s yummy “@ PoguesRunGrocer: Our signature Broccoli Salad recipe is in the new issue of @EdibleIndy!”

—Marisol, May 30

Slow Food Indy created the Snail of Approval Honoree Program in 2012. This program is a member-driven process in which a committee votes on who will receive the Snail of Approval award. The program is designed to showcase and encourage those businesses that are committed to Slow Food values and make them integral to their operation. The aim of the program is to drive traffic to the recipients of the award, helping them become more successful and thereby further promoting sustainability. Edible Indy is pleased to announce the 2014–15 list:

Black Market

Bluebeard

Cerulean—Indianapolis

Duos

Goose the Market

Indigo Duck

Late Harvest Kitchen

Libertine

Milktooth

Pizzology

Plow & Anchor

R Bistro

Recess

The Loft at Trader’s Point Farm

The Local Eatery and Pub

Congratulations to this year’s honorees for their continued efforts promoting sustainability. For more information on Slow Food Indy, visit SlowFoodIndy.com.

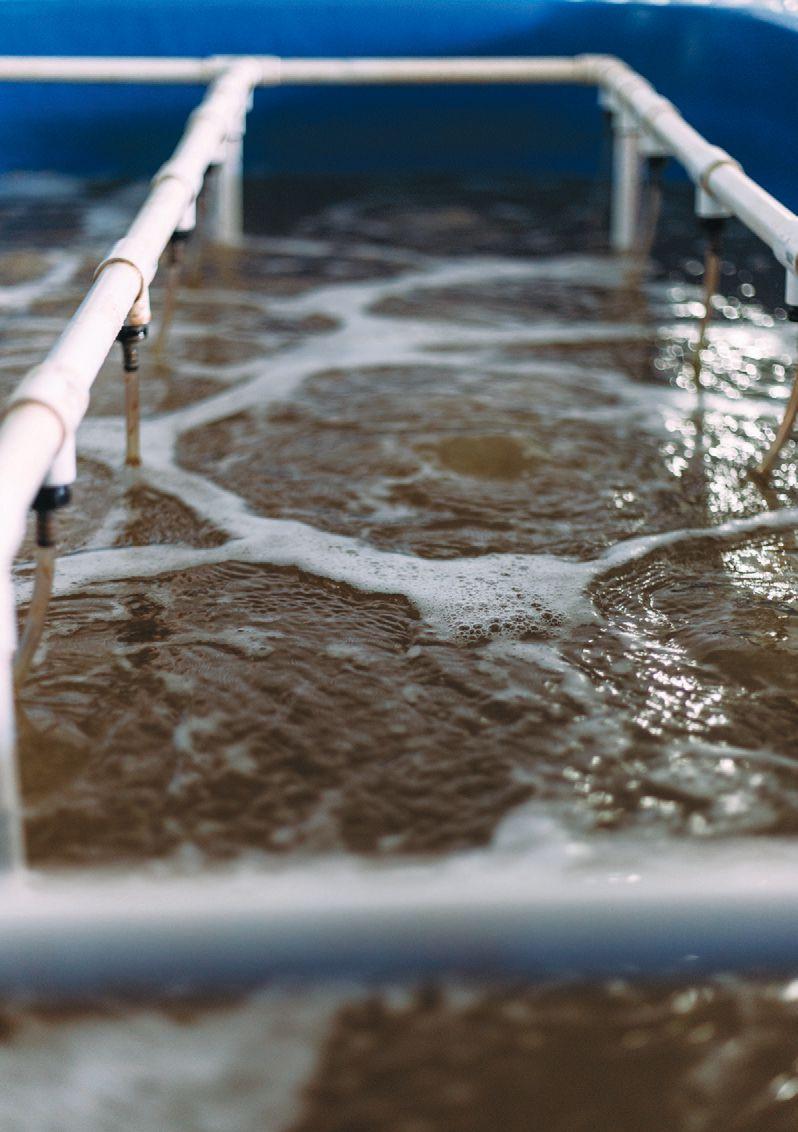

WRITTEN BY VIRGINIA PLEASANT, PHOTOGRAPHY BY KOLTON DALLAS

Tucked in amidst more familiar crops like corn and soybeans, Indiana boasts a growing number of shrimp farms. Yes, you read that right: Hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean, a handful of Hoosier farmers are producing shrimp. These farms provide an alternative to both domestically caught wild shrimp and imported farmed or wild shrimp. Growing concern over the safety of wild shrimp due to water pollution and of foreign farmed shrimp due to inconsistent quality and environmental impact have created demand for a fresher and safer alternative.

Domestically, the shrimping industry in the Gulf of Mexico is still struggling to recover from the Deep Water Horizon oil spill of 2010. Although recent studies show that the quality of the shrimp is recovering, the numbers of shrimp caught in an average haul are still much lower than they were prior to the spill. However, shrimp remains the most popular type of seafood consumed in the U.S., accounting for a quarter of seafood consumption.

The traditional alternative to domestically caught shrimp has been imported farmed or wild-caught shrimp. Although some of these sources receive a thumbs up for quality, safety and environmental impact (FishNavy.com provides a concise breakdown), many are questionable. Furthermore, food safety inspections struggle to keep up with the volume of shrimp and other seafood being imported.

The FDA inspects only 2%–20% of seafood that is imported. Shrimp comprise only a fraction of what is inspected, and 80% of the shrimp that are inspected are ultimately rejected. Rejected shrimp are declined for various reasons, including elevated levels of antibiotics, preservatives and other additives, as well as inferior quality. In addi-

tion to food safety concerns, irresponsibly managed shrimp farms raise environmental concerns and have been associated with aquatic “dead zones.”

But does Indiana-farmed shrimp provide a viable alternative?

There are two main types of shrimp farming in Indiana: fresh water shrimp (also called prawns) and saltwater (or marine) shrimp. Fresh water farms are mostly located in Southern Indiana because the longer growing season is better suited for the outdoor ponds that are used. These ponds are drained and harvested in the early fall. Saltwater farms are scattered throughout the state and use indoor pools, which allow for better temperature control and make it possible to produce shrimp year-round.

On a recent visit to BDJS (Best Darn Jumbo Shrimp) Farms in Cutler, I saw a marine shrimp operation firsthand. BDJS is owned and operated by the Barbour family and has been in business for over three years. As with other shrimp farms in Indiana, you aren’t likely to find their shrimp in grocery stores. Instead, you can try their shrimp in locally sourcing restaurants including Bluebeard, Plat 99, R Bistro, Cerulaean, Black Market and others. You can also buy shrimp directly from the farm, or in specialty food stores and meat markets.* (Some farms also participate in farmers’ markets.)

Barbour grows its Pacific White shrimp in 18-foot above-ground swimming pools with pumps to circulate water. Doug Barbour uses swimming pools because they are relatively simple to set up and work well with the environmentally sustainable business model at the heart of BDJS. Barbour strives for a zero-waste facility: Pools are recyclable if they need to be replaced, water is recirculated and

micro-organisms are used to maintain a beneficial ecosystem. Barbour says the heaters used to maintain water temperature use less energy than an average household in a year. The only additives used in the water here are baking soda and sugar.

Although BDJS and a growing number of other farms recirculate water or, in the case of outdoor prawn farms, drain water into holding tanks for future use, some farms don’t. Dumping of water has led to environmental concerns of wasted water and potential contamination. Barbour and others like him act as consultants for farmers hoping to make the switch to more sustainable systems. Another concern for shrimp farmers (although not in Indiana so far) has been viral infection of shrimp, a main area of aquaculture research for the USDA.

Some potential consumers of Indiana farmed shrimp are skeptical of their quality and concerned about the implications of moving coastal industries inland. It does, after all, defy logic to find saltwater shrimp pools in the middle of cornfields. But these shrimp do provide a fresher and safer alternative to many of their imported counterparts. And, as more farms move toward contained systems with little to no waste, they will become a more environmentally sustainable option.

Virginia Pleasant is a PhD student at Purdue University and is affiliated with the American Studies and Anthropology departments. She researches food systems and culture as well as smallscale and alternative food production.

Saltwater

BDJS (Best Darn Jumbo Shrimp)

Farms

Cutler BDJSFarms.com 765.268.2040

Bedrock Springs Seafood Farm

Ladoga Facebook.com/Bedrock-SpringsSeafood-Farm

RDM Farms

Fowler RDMShrimp.com 765.583.0052

Big Barn Shrimp Farm Flora Facebook.com/BigBarnShrimpFarm 574.967.3266

JT Shrimp Wheatfield JTShrimp.com 219.987.3809

Indiana Aqua Farms (White Diamond Shrimp)

Columbus IndianaAquaFarms.com 812.344.8889

Fresh Water

Eddy-Lynn’s Shrimp Farm Coatesville ShrimpFarmingInIndiana.com 765.386.7496

Connor Shrimp Farm Monrovia

ConnorShrimpFarm.com 765.349.1427

Retail

Goose the Market GooseTheMarket.com

Moody’s Butcher Shops MoodyMeats.com

SOURCES

USDA.gov Ag.Purdue.edu

FishNavy.com

Doug Barbour, BDJS Farms

WRITTEN BY CORTTANY BROOKS RECIPE AND RECIPE PHOTO BY JENNIFER RUBENSTEIN

As the first leaves of fall begin to turn and Hoosiers reach for their scarves, the rituals of autumn call upon us. Another ritual is unique to our southern Hoosiers: the enjoyment of Indiana’s persimmon fruit.

From the Latin for “divine fruit”, the persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) is a native Indiana tree that bears golf-ball-sized fruit that usually turns a bright orange and falls to the ground in late fall.

The persimmon is unlike other fruit in that it does not fully ripen until after it has dropped from the tree and onto the earth. Ripe persimmon fruit is sweet, with high sugar content, making it ideal for many desserts such as sherbet, custard, pudding and cake.

For Bloomington Brewing Company, late autumn means the opportunity to brew their specialty Persimmon Ale. Over 100 pounds of Indiana persimmon pulp is added to the boil kettle, along with ground cinnamon and nutmeg, giving the brew some holiday spice, according to Mark Cady, business manager at BBC.

All of the persimmons in their ale are harvested in the wild and provided by Dillman Farms, a family-owned treasure of Monroe County. Their motto: “We believe that the food we eat should be as simple as possible.”

About 35 miles south of Bloomington, Mitchell’s Annual Persimmon Festival, sponsored by the Greater Mitchell Chamber of Commerce, has become a Southern Indiana tradition that commemorates this indigenous signature fruit with a weeklong celebration. The 2014 festival, the 68th, takes place Sept. 20–27, with Main Street activities kicking off on Monday. For more information on the festival visit PersimmonFestival.org.

Persimmons are a native resource that few people are aware of. The fruit is healthy, high in nutrients and should be harvested immediately if they have fallen to the ground. If you’re not yet a fan of this fruit, we can guarantee you will be after Edible Indy’s Persimmon Cardamom Ice Cream with Maple Syrup and Toasted Almonds.

Corttany Brooks is a junior at Ohio University and assistant managing editor at Edible Indy. She is working towards degrees in journalism and political science and hopes to find a job after graduation that will allow her to apply her knowledge of communications with her love of healthful living.

A common myth about the persimmon tree is that when the ovary inside a persimmon fruit is shaped like a spoon, a bad winter is expected. When it is shaped like a fork, a mild winter can be expected.

The common persimmon tree is a native species found in a variety of habitats from southern New England, throughout the southeastern United States and westward to California. ‘ It is one of the few trees that can grow in almost any type of soil, and can adapt to a wide range of climates. They are an excellent source of potassium, much higher than bananas.

Old wives’ tale: Eating them raw can cure leg cramps.

Yields: 1 quart

1½ cups heavy cream

1 cup half and half (or soy milk)

½ cup sour cream

½ cup brown sugar

¼ cup maple syrup

½ teaspoon cardamom spice

2 teaspoons vanilla extract

2 cups persimmon pulp, puréed (we purchased pulp from Dillman Farms)

½ cup toasted chopped almonds (sauté them in a pan with butter until slightly brown)

Pour 1 cup of the cream into a medium saucepan and add the sour cream, sugar, maple syrup, and cardamom spice. Cook over medium heat, stirring, until the mixture is smooth and dissolved, about 5 minutes.

Remove from heat and add the remaining cream, half and half or soy milk, persimmon purée and vanilla extract. Chill mixture for at least 8 hours, preferably overnight.

Pour mixture into your ice cream maker and freeze according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Add in the toasted almonds near the end of the process to allow for the almonds to be distributed evenly. Transfer ice cream a freezer container.

Cooking with...

... Indianapolis Colts Player and Great Italian Cook

WRITTEN BY JENNIFER RUBENSTEIN

PHOTOGRAPHY BY KOLTON DALLAS

“I maintain that French cooking is cheating: When you throw butter and cheese in something, it is going to be delicious.”

—Anthony Castonzo

We recently invited Anthony Castonzo of the Indianapolis Colts to cook with us in the Edible Indy kitchen. This sixfoot-seven Chicago-born, Italian-rooted gentle giant soon confirmed that he knows his way around the kitchen with very little assistance.

He politely took his shoes off before walking into the kitchen, lugging with him his favorite kitchen appliance, a Cuisinart food processor, along with a cookie tray and aluminum foil. He came prepared to cook us one of his favorite Italian dishes, Chicken Pesto Pasta with Pine Nuts.

Anthony, best known as #74 left tackle of the Indianapolis Colts, is also known as the Italian who loves to cook. Growing up in Hawthorn Woods, a suburb of Chicago, he became acquainted with the kitchen at an early age. His parents, Bill and Shari Castonzo, owned Oregano’s Corner Café from 1998 to 2011, a down-to-earth Italian eatery. His mother, Shari is the cook in the family.

“My mother is very impressive in the kitchen,” Anthony told us before he joked about the fact his nani (grandmother) made Shari, who isn’t Italian, learn how to cook her inherited Italian dishes as prerequisite for marrying her son.

Cooking Italian food comes naturally to Anthony. He reminisced about one of his earliest memories of making homemade pasta in his preschool class with his mom. He recounts cranking the pasta machine and how exciting it was to watch the machine turn dough into pasta.

While attending Boston College, he studied biochemistry, was a

Scholar nominee and had a record 54 starts on the football field. Coming to college at 240 pounds, he was still required to gain 60 more to continue to play college football. It is this time that he accredits with the growth of his diverse and healthy food tastes.

He extensively researched gaining healthy weight rather than using the mentality of eating as much of whatever and whenever just to increase weight. He explained, “I needed to gain the weight gradually and had to eat consistently, but I didn’t want to just get fat.” During his research, the availability of East Coast seafood and a television in his dorm turned his slight love for food into more of a passion.

“I discovered and watched the Food Network all the time,” he recalls. Tyler Florence, Giada De Laurentiis and Ina Garten quickly taught him how to whip up great dishes with heart and soul.

“Giada [of the Food Network] used pine nuts on the regular, so I thought I would give it a whirl,” he explains while munching on them in the kitchen. Pine nuts are one of his favorite foods. Toasting them up in the oven during our interview, he threw them in some olive oil with a pinch of salt and pepper. His first experience with pine nuts was at his family’s restaurant with a tomato, basil and pine nut pizza—still popular the menu at Oregano’s. He tends to eat them often as a snack or throw them into a pasta dish like the one he made for us, to add a little extra flavor and protein.

While Anthony has clean and healthy eating habits, he does have a few food weaknesses.

“My ultimate cheat meal that I could eat everyday of the week is my mom’s Sunday gravy. You wake up in our house at 8 m and it

“I am a big fan of pounding chicken so it will tear apart and have the best flavoring.”

—Anthony Castonzo

smells of fresh garlic.” He continues to talk about how adding in meat is what makes it “gravy.” His mother puts braciole—a butterflied beef filled with cheese, garlic, Italian parsley, basil and prosciutto, rolled together and braised—into the sauce along with her secret ingredient: neck bone. She simmers the meat in the marinara sauce all day. Before serving the gravy, all of the meat and neck bone are removed and served separately from the pasta and the sauce. Then, the gravy is served up with perciatelli, a pasta that is like a thicker spaghetti with a pinhole through the middle.

He also has a few must eats around Indianapolis. One of his favorite local establishments is Bluebeard in Fletcher Place, where he and his girlfriend visit frequently. Living in Zionsville he also loves to hit up Noah Grant’s, where he says he has found the best sushi in Central Indiana. After spending years in Boston, where the fish is of optimal freshness, he said the fish at Noah Grant’s tastes the closest to what he fell in love with on the coast.

The meal he splurges on the most is breakfast. He also loves to grab Hoosier grub created by Café Patachou and Jacquie’s Café, both Hoosier favorites for creating dishes with local ingredients.

He grills when he can, as he prefers the least mess possible and the freshest cooked meals. His refrigerator tends to be bare, as he frequents the store on a near-daily basis. Eating five meals a day and between 4,000 and 5,000 calories, he strives to keep his meals appealing and new.

One of his favorite meals to make at home is a mushroom garlic bison burger tortilla. Moody Meats is his go-to butcher to get fresh meats like ground bison, salmon and even sea bass. Another must-have are Cherub tomatoes; he says he eats them like candy and can’t get enough of them.

Rounding out our afternoon of cooking and conversation with Anthony, he quickly whipped up the pesto with freshly grated Parmesan cheese, toasted pine nuts, a couple handfuls of basil, olive oil and salt and pepper. Then he sliced up the seasoned sautéed chicken breasts and strained the penne. He arranged the plate beautifully in his Anthony Castonzo manner with just one dish, plated with the lovely pesto spread over the chicken and pasta.

He then said, “Can we eat it?” and Matt Conti, assistant director of communications for the Indianapolis Colts; Kolton Dallas, our intern and photographer; my husband, daughters and I each grabbed up a bowl. Silence took over as we savored this simple, fresh and deliciously prepared dish cooked up by a man so overwhelming in size, yet so humble in nature.

It is enlightening to see how at home Anthony is in Central Indiana and how strongly he feels about eating well and being embedded within the local movement. He does all of this while making it a priority to support the local community, from the markets to the feasts, and to celebrate the bounty under his nose.

Breakfast: three egg whites, two egg yolks, toast, yogurt and oatmeal

Protein shake

First Lunch: a sandwich with some wheat pasta and a salad

Protein shake

Second Lunch: a peanut butter and jelly sandwich

Dinner: fish or other lean protein, pasta, salad and vegetables

Late-night snack: high protein and fat, such as nuts or beef jerky

Co-founders of SmithBites.com, Rod, aka “The Professor,” and Debra Smith are professional photographers, videographers, writers and storytellers whose first life involved creating jingles and voiceover for radio, television and film. Their love of food as well as a great story has allowed the Smiths to photograph and create videos about food on both coasts of the U.S. and in Europe.

Hard cider has quite the colorful history here in America; in fact, during Colonial times in the Eastern States, cider was more popular than beer, wine or whiskey. It was far more difficult to grow grains for beer than it was to grow apples, so seeds were brought over from England and orchards were established. In time, cider-making became as popular here as it was in England. By the mid-1800s, the New England states were producing nearly 300,000 gallons of cider every year.

As settlers moved west, missionary John Chapman, also known as Johnny Appleseed, traveled ahead grafting small nurseries of cider apples in the Great Lakes and the Ohio River regions. Because it was safer to drink than water, making hard cider was quite common on most homesteads by the end of the 19th century.

Once one of the most popular alcoholic drinks, hard cider lost its momentum during Prohibition. Many orchards were burned to the ground, and by the time Prohibition ended, German settlers were establishing large breweries for making their beloved beer. Thanks to the popularity of microbreweries, cider is experiencing huge growth here in the U.S., with cider production increasing nearly 264 between 2005 and 2012.

When we moved into our house 12 years ago, we were fortunate enough to inherit mature fruit trees—three apple trees and one pear tree that reside in a sunny patch of our yard. I’m not really sure how old the trees are, but they are prolific producers of sweet apples and pears. It’s impossible to consume all the fruit each season before the bees and raccoons claim them. We’ve made pies, pear caramel sauce, jams and jellies. Last year, we made our first attempt at making pear cider.

When I learned I needed to eliminate gluten from my diet, traditional wheat-based beer was no longer an option. Apple and pear ciders are a wonderful alternative (and ciders also happen to be one of my favorite fermented beverages to sip).

In our research, there are many different methods and opinions when it comes to home-brewing. This was our first experience, and while “true” cider apples are called “bittersweets” or “bittersharps” and taste terrible, our trees produce Golden Delicious and Forelle fruit, which typically aren’t used for making ciders. We were still pleased with our results, and it was a fun experiment.

Makes 10 (12-ounce) bottles

18–20 pounds fresh pears (our tree produces Forelle pears)

1 Campden tablet (for sterilizing)

1 teaspoon Cuvee Active Dry Wine Yeast

½ cup simple syrup (equal parts sugar and water)

Special Equipment Needed:

2 (1-gallon) carboys (glass bottles)

Siphon hose

Bung

Airlock

Bottles

Funnel

Juice approximately 18–20 pounds of pears to fill a 1-gallon carboy; we used an electric home juicer. Be sure to sterilize all the tools and the carboy. We used a product called Star San, which is available online and in local home-brew shops. The juice can either be pasteurized (by slowly heating it to 170° and then cooling it back to room temperature) or sterilized by adding a Campden tablet to it and letting it sit for 24 hours; both methods kill any bacteria that might be present.

Funnel the treated juice into a 1-gallon carboy and add a teaspoon of yeast (known as pitching). We used Cuvee Active Dry Wine Yeast, but you could substitute Champagne yeast or other recommendations from a local homebrew shop. Some brewers choose to add the active dry yeast directly to the carboy like we did, but most will recommend you rehydrate the yeast according to the instructions on the packet.

After pitching the yeast, cap the carboy with a “bung” (stopper) and an “airlock”; the airlock lets the gases escape without outside air entering the carboy. As the juice ferments, tiny bubbles will rise to the top; once you stop seeing bubbles, fermentation is complete (approximately 2 weeks).

At this point, it’s time to carefully siphon the fermented juice into another 1-gallon carboy—try not to siphon any of the sediment at the bottom. Add ½ cup of simple syrup, which is used to create a secondary fermentation in the bottle.

Siphon this mixture into individual bottles. We have used both bottles with caps and bottles with swing-top rubber stoppers. (We prefer the swing-top rubber stoppers because the seal seems more secure.) One gallon of cider will fill approximately 10 (12-ounce) bottles or 4 (32-ounce) bottles. Put the sealed bottles in the refrigerator immediately. After about a week (or up to 6 months) your sparkling pear cider is ready to enjoy!

You can also view a short video piece we made documenting our experience by visiting EdibleIndy.com. You’ll need a few basic pieces of home-brewing equipment but they aren’t very expensive—and as I said, it’s fun!

WRITTEN BY CORTTANY BROOKS, PHOTOGRAPHY BY KOLTON DALLAS

Most farmers have a fair idea of how much they spend on heat and electricity but relatively few regularly monitor their total energy consumption. When they look a little closer, many of them start to explore investing in renewable energy.

“Renewable energy” is any naturally occurring, theoretically inexhaustible source of energy that is not derived from fossil or nuclear fuel. These sources include biomass, solar, wind, geothermal, tidal and hydroelectric power. In the past five years, Indiana has made tremendous strides in the use of wind, biofuel, solar and biomass resources. Furthermore, Indiana has used its manufacturing skills to become an integral part of these energy industry supply chains.

Potential savings are greatest in energy-intensive sectors such as pigs, poultry, dairy and those reliant on refrigerated storage but relatively simple measures can be applied on any farm. In fact, improving the energy efficiency of existing buildings, equipment and processes could give a quicker and longer-lasting financial return than any other investment activity, says the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

If the trend of renewable energy sprouting up across the nation’s farms is emblematic of the connection between earth and economy, Fortune Acres, a certified-organic farm in the Traders Point area, is a good example. Sheila Fortune, owner of the 56-acre farm, stands by their commitment “to keep the land as it is, for future generations.” In 2010, she went looking for energy alternatives, and settled on a a low-wind-speed turbine to generate electricity, a geothermal heating system for the barn and a solar fan for the greenhouse.

Electricity generated from renewable sources including hydroelectric power makes up a very small share of Indiana’s total use. Wind continues to be the primary renewable resource for electric power generation in Indiana.

As a whole, Indiana has moderately good potential for solar energy development, particularly in the southern part of the state, which sees on average more than four and a half hours of direct sun per day

throughout the year. Indiana’s Solar Thermal Grant program, administered by the Office of Energy Development, has helped fund more than a dozen solar projects in the state, including a water-heating system at Bloomington’s Upland Brewery. The 600-gallon system produces enough hot water for the brewery’s normal kitchen use as well as preheating water for its brewing process, prompting the company to rebrand its signature brew as Helios Pale Ale, after the Greek word for “sun.”

Other renewable energy projects in the state include a geothermal heating and cooling system at Ball State University in Muncie. The university is installing the nation’s largest ground-source geothermal heating and cooling system. The system will replace four aging coalfired boilers and provide renewable power that will heat and cool 47 university buildings. It is estimated that $2 million in operating costs will be saved each year, and that the university’s carbon footprint will be cut in half. The first half of the project was completed in March 2012, and the final half is scheduled for completion in 2015.

The prospective success of renewable power on her farm has made Sheila Fortune a renewable energy advocate.

“Ms. Fortune aspires to be as natural as possible,” said Max Wilkinson, farm manager at Fortune Acres. “We want to use the resources in the ground in every way we can here.”

Indiana’s first utility-scale wind farm, the Benton County Wind Farm (also called Goodland I), opened in 2008, producing 130 megawatts of electricity per year. Today, Indiana boasts 1,300 megawatts of wind power, enough to provide electricity for 300,000 homes. And there’s an additional 8,000 megawatts wind power in the works.

The local economy is getting a lift from wind energy as well. In 2009, the wind industry supported 3,000 to 4,000 jobs in Indiana. At least 14 facilities in the state manufacture

components for the wind industry. Gearbox manufacturer Brevini recently opened a plant in Muncie, despite the economic downturn, and employed 200 people there by 2012, with an ultimate goal of 450 jobs at the facility.

Turbines used to produce electricity from wind can provide a large portion of the average power needs of a farm, however they must be located in high-wind areas and generally require at least one acre of land to produce enough energy. Farmers or ranchers with grazing land in an area with good wind speeds could also consider leasing their land for wind power production to a utility company while still being able to use their land for their animals. For the option of running a system connected to the grid, the land owner must have an average annual wind speed of at least 10 mph. Installing wind turbines is a long-term investment, costing anywhere from $13,000 to $40,000 for a residential wind energy system.

Keep in mind a wind turbine can be a good complement to a photovoltaic (PV) system (see solar) in temperate climates. Wind energy is available when solar energy is not. It is strongest in fall, winter and spring, as well as at night when hot air rises from the earth’s surface, increasing air flow.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Wind Program and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) published a wind resource map for Indiana revealing Central and Southern Indiana farms may not see return on their investment for over a decade, while the northern, especially northwestern, part of the state is “well-suited” for wind development.

While many think of hot springs and natural hot water as the source for geothermal power, there is a source of geothermal power much more commonly available: simply the constant ground temperature. Farm buildings and homes can use geothermal heat pumps to exchange air temperature and ground temperature year

round, keeping buildings cool in summer and warm in winter. While geothermal systems are more expensive to purchase and install than a typical fossil-fuel-burning furnace, the return on investment is just five to 10 years. Geothermal systems are best suited for new construction, considering the extensive excavation process involved.

Keep in mind that any renewable energy electric system on the farm can be connected to the utility grid with an inverter, allowing the farm to receive financial incentives for the power it produces. When considering a renewable energy system, check with local laws and ordinances before beginning construction.

The sun’s energy can be used for heating and cooling greenhouses and water systems, or with photovoltaics it can be used to produce electricity. PV systems can be used to power lighting, electric fencing, small motors and fans, and for pumping water and charging batteries.

Passive solar design can be used to heat and cool greenhouses—a cost-effective option for small growers interested in extending their growing season. A solar greenhouse is highly insulated, uses natural ventilation, and has panels angled to collect maximum solar heat depending on the latitude or location of the greenhouse. Like any major appliance, certified and labeled solar heaters are the most reliable. Consult the Solar Rating and Certification Corporation (SRCC) for certification and rating of solar equipment.

Indiana is the third-fastest-growing state in wind energy capacity, ranking 11th in the nation. Between 2009 and 2012, the state increased its wind capacity tenfold.

The 65 megawatts of solar energy currently installed in Indiana ranks the state 20th in the country in installed solar capacity, enough to power 6,900 homes.

Geothermal resource potential maps for the United States show naturally occurring geothermal resources available and deployed today. (Rankings by state are unavailable.)

Financial incentive programs are vast but frequently changing, therefore the best way to stay up to date with current programs is to check online resources such as the Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE) regularly. For a full listing visit dsireusa.org.

Indiana Office of Energy Development: energy.in.gov

U.S. Department of Energy: energy.gov

Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency: dsireusa.org

U.S. Energy Information Administration: eia.gov

Natural Resources Defense Council: nrdc.org

U.S. Department of Agriculture: usda.gov

Solar Energy Industries Association: seia.org

Fortune Acres: FortuneAcres.com

Federal and state programs are playing a critical role in supporting the renewable energy industry, but they are insufficient to the long-term task of transforming our energy economy. That will require a set of innovative energy policies in addition to substantial program funding. Indiana could be at the center of a new clean-energy future for America if the right policies are put in place, starting with a national commitment to reduce emissions of global warming pollution, support energy efficiency and advance development of homegrown renewable energy.

Corttany Brooks is a junior at Ohio University and assistant managing editor at Edible Indy. She is working towards degrees in journalism and political science and hopes to find a job after graduation that will allow her to apply her knowledge of communications with her love of healthful living

WRITTEN BY JENNIFER RUBENSTEIN GRAPHICS BY SOFIA PUGA

The mission of the Indianapolis Zoo is to empower people and communities, both locally and globally, to advance animal conservation. The original Indianapolis Zoo opened in 1964 and in the summer of 1988 moved to its current location at White River State Park.

Over $1.98 million was raised this year at the 28th annual Zoobilation fundraiser, where over 70 local restaurants provide food and beverages to a sold-out black-tie crowd. U.S. News & World Report ranked the Indianapolis Zoo as No. 6 on its list of Things to Do in Indianapolis.

Edible Indy asked: How does the zoo support the local food movement with the animals? The answers might surprise you.

Indianapolis Zoo feeds and cares over 2,000 animals (230 species) and 16,000 plants.

(Approximately 50% of the groceries are purchased locally.)

300 tons (600,000 pounds) of grass and alfalfa hay are locally grown, harvested and purchased each year.

Meat $120,629

Fish

$108,728

Hay $ 88,586

Produce $ 64,423

Other $ 64,770

Grain $ 62,114

Gel $ 26,886

Total Grocery Bill: $536,136

“The zoo recently established a purchasing agreement with the Indianapolis Airport Authority to procure hay from the land that surrounds the airport. According to the FAA this property must remain ‘empty’ but it can be cultivated for crops such as grass/ alfalfa, wheat and certain legumes. By entering into this agreement we are establishing relationships with local farmers and supporting the local economy,” says Zoo Nutritionist Jason Williams, PhD.

$90,000—$105,000 in hay is purchased locally each year from two vendors.

MEAT

Approximately 100 pounds a day (37,000–40,000 pounds a year).

Locally owned Indianapolis meat distributor, Dugdale Beef Company, provides 100% of the beef, of which 30%–45% is from local farms and the remainder from other Midwest farms.

Meat purchased is USDA ground beef 90%–95% lean.

100% of mice, rats and rabbits come from Martinsville rodent vendor Hoosier Mouse Supply.

PRODUCE

Gordon Food Service provides 90% of the produce.

The zoo has an onsite garden that produces tomatoes, eggplant, strawberries, herbs, blackberries, apples and more.

African elephant, Tombi

Cost per day to feed: $26.50

Weekly

Hay: 18 bales (40 pounds/bale)

Mega-Herbivore cubes: 58.8 pounds

Leaf-eater biscuits: 11 pounds

Sweet potatoes: 20 pounds

Produce: 13.6 pounds

African lion, Nyack

Cost per day to feed: $23.50

Weekly

Beef: 9 pounds

Large rabbit: 1

Femur bone: 1

Annually

Hay: 936 bales

Mega-Herbivore cubes: 3,057 pounds

Leaf-eater biscuits: 572 pounds

Sweet potatoes: 1,040 pounds

Produce: 707 pounds

Giraffe, AJ

Cost per day to feed: $9

Weekly

Herbivore Grain: 5 pounds

Lo Pro Grain: 4 pounds

Sweet potato: .75 pounds

Produce: 2 pounds

Orangutan, Rocky

Cost per day to feed: $7.50

Weekly

Gel: 4.63 pounds

Leaf-eater biscuits: 2.71 pounds

Starch: 1.54 pounds

Fruit: 4.63 pounds

Approved produce: underripe bananas, apples, pears, melons, carrots, greens

An African elephant consumes between 1.4% and 1.6% of its body weight per day.

Elephants eat 45,000 pounds/year of locally harvested hay and grass.

Total elephants: 8

Food enrichment: 2.5 pounds

Annually

Beef: 468 pounds

Large rabbits: 52

Femur bones: 52

Food enrichment: 130 pounds

Primary diet contains commercially formulated carnivore meat.

Food enrichment: rodents, beef liver, chicken broth, goat milk, steamed chicken breast, beef chunk meat

Total lions: 3

Annually

Herbivore Grain: 260 pounds

Lo Pro Grain: 208 pounds

Sweet potato: 39 pounds

Produce: 104 pounds

Giraffes are browsing herbivores.

Giraffes are given hay and browse (tree and shrub cuttings from around the zoo) as treats each week, based on diets and availability.

Total giraffes: 3

Greens: 9.25 pounds

Vegetables: 6.94 pounds

Annually

Gel: 240 pounds

Leaf-eater biscuits: 140.92 pounds

Starch: 80 pounds

Fruit: 240 pounds

Greens: 481 pounds

Vegetables: 360.88 pounds

The Indianapolis orangutans grew up in entertainment or in a zoo setting, not in the wild. Their diet is different than what it would be in the wild.

Approved zoo diet consists of primate biscuits, fruits, starches, vegetables, greens and enrichment items. Examples of orangutan food: cherries, peaches, tomatoes, tomatillos, mung bean noodles, white potatoes, plantains, mushrooms, leeks, broccoli, collard greens, dandelion greens, peanut butter, prunes, pumpkin, sugar-free Jell-O.

Total orangutans: 8

Many animals eat treats called browse, which is made up of trimmings and clippings from edible landscape around the zoo, such as grass, trees and flowers. Other browse comes from palms and bamboo grown onsite.

“When designing new landscape, we keep in mind what can we use and feed out in the future,” says Lori Roedell, curator of horticulture. “About 50% of the landscape at the zoo is edible.”

Edible landscape is the priority. Otherwise, the plants should work well for perching or propping, or at the very least, they should be useful for making mulch.

“Depending on where the product is grown, the nutrients are different due to soil and environment, so we coordinate with horticulture to grow small amounts of produce to create variety for the animals,” says Kat Davis, nutrition area manager.

“About 10% of the garden is used by the chefs at the zoo for guests to enjoy,” says Lori Roedell, curator of horticulture. Humans visiting can chose from the healthy local ingredients provided by Smoking Goose, Trader’s Point Creamery, Pleasant View Orchard and Eden Farm at the Farm-to-Table Stand, Café on the Common and other stands throughout the campus.

But much of the produce grown on the zoo campus is used to feed the animals. Here’s what they grow in the garden:

Alpine currants apples apple squash basil (orangutans like basil) beans black raspberries corn dandelion greens eggplant lemon balm mustard greens peppers pumpkins sunflowers (tortoises eat the heads) tomatoes watermelons

We asked why the zoo has not been able to create more contracts with local farms for animal feed. Zoo nutritionist Jason Williams, PhD explains:

“The diets for our animals can be very specific with regards to product type and thus it can be difficult for local vendors to keep up with our demands.”

And as much as the zoo would like to accept food donations or road kill for the animals, they can’t, due to food safety concerns. All food needs to filter through the commissary to pinpoint any issues.

If you have interest in donating your time or money to the Indianapolis Zoo, call 317.630.2025 or visit IndianapolisZoo.com.

Photos, top to bottom: Lori, Roedell, curator of horticulture inspects the Zoo’s garden for ripe produce. Riley at IU Health helps ensure healthy dining options with local ingredients for the Zoo’s guests. Kat Davis, nutrition area manager talks of the local harvest from the Zoo’s garden.

COCKTAIL RECIPE COURTESY OF CERULEAN PHOTOGRAPHY BY KOLTON DALLAS

Perfect for a fall evening. The tobacco brands used in the simple syrup are ommonly found at any cigar shop.

2 ounces lighter blend scotch

½ ounce Tobacco Simple Syrup (recipe below)

1 dash Angostura Bitters

1 dash Green Chartreuse

Rim rinse: Single-malt scotch

Tobacco Simple Syrup (Makes 2 quarts)

1 quart hot water

1 quart sugar

15 grams Reigel’s Blend pipe tobacco

10 grams Cornell & Diehl Epiphany pipe tobacco

Mix together and cover. Steep for 15–17 minutes. Cool completely. Once cool, pour into a glass container with a lid. Syrup will keep up to 6 months refrigerated.

Place large ice cube in tumbler, rinse glass with single-malt scotch, dash top of ice cube with bitters. Combine scotch, syrup and Green Chartreuse into mixing glass and stir until chilled. Strain into prepped tumbler.

Available at Vine and Table, Carmel VineandTable.com

Green Chartreuse $59.99 Angostura Bitters $9.99

Three mouthwatering pear dishes for your fall feast

Indiana Duck Breast with Zucchini, Wild Mushrooms, Pears and Pine Nut–Pear Ketchup

Recipe and Photo Courtesy of Jonathon Brooks, owner and executive chef, Milktooth

Serves 2

2 duck breasts, scored and seasoned liberally with kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

For the Pine Nut–Pear Ketchup

(This recipe makes extra ketchup.)

“The awesomely primal flavor and texture of duck too often gets lost in overly rich flabby dishes. Here, the duck’s fat carries these barely cooked vegetables and the sugary musk of the pear is expressed raw and is a background note in a ketchup that’s served warm and bears no resemblance to Heinz.”

—Jonathan Brooks

2 tablespoons coconut oil or bacon fat

½ sweet yellow onion, diced

1-inch piece ginger, minced

3 cloves garlic, minced

2 tablespoons tomato paste

2 pears, diced

3 medium-sized ripe tomatoes, diced

⅓ cup light brown sugar

¼ cup vinegar

1 cup water

½ cup toasted pine nuts

1 teaspoon ground turmeric

1 teaspoon ground red pepper

¼ teaspoon each: ground clove, curry powder, ground cumin

1 tablespoos kosher salt

Leave out the duck breasts while you prepare the ketchup, and preheat oven to 350°. On low heat, sauté the yellow onion and ginger in coconut oil for 4 minutes or until translucent. Add the garlic and sauté another 4 minutes. Add tomato paste and

sauté 4 minutes. Add the rest of the ingredients and bring to a simmer over high heat. Exercise extreme caution if choosing to purée the ketchup at this point. Otherwise, reduce heat to low and continue cooking while you finish the dish.

To compose the dish:

1 medium zucchini, halved horizontally

1½ cups wild mushrooms, sliced thickly

1 small red onion, shaved thinly

1 pear, shaved thinly

Put the duck breasts skin side down in a cold pan over medium heat with no oil or butter, allow the skin to brown and the fat to render for 10–15 minutes, periodically carefully draining the excess fat into a container for another use. Put the pan in the oven with the duck still skin side down and cook for 11 minutes, basting the flesh side once with the fat in the pan halfway through cooking. After cooking, flip the duck and rest it in the pan before slicing and while preparing the vegetables.

Sauté the zucchini and mushrooms in 1 tablespoon rendered duck fat briefly, 4–5 minutes, just long enough to get some nice caramelization on the outside. Season with salt and pepper, slice to your liking, serve with the sliced duck and ketchup, garnish with shaved onion and pear.

Recipe created by Head Chef Dan Nichols, Quaff

Serves 10

5 heads baby iceberg lettuce

½ cup rehydrated dried cherries

½ cup chopped pecans

Vinaigrette

1 cup apple cider vinegar

⅔ cup buttermilk

1⅔ cups mayonnaise

2 cups sour cream

4 tablespoons minced onion

4 tablespoons minced garlic

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1 teaspoon Tabasco sauce

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh parsley

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh thyme

½ pound smoked bleu cheese, finely crumbled

Combine all ingredients except bleu cheese and whisk until well combined and smooth. Stir in bleu cheese.

Chai tea poached pears

5 pears

2 quarts water

4 tablespoons chai tea

Peel, halve, core and remove stems from pears. Bring water to boil and add chai tea. Steep tea for 5 minutes. Strain liquid and poach pears in liquid for about 30 minutes, until pears are soft.

Candied bacon

½ cup brown sugar

1 tablespoon rice wine vinegar

½ cup hot water

1 pound bacon

Preheat over to 350°. Mix sugar, vinegar and water. Lay out bacon on sheet pan and cook in oven until almost done. Brush sugar mixture liberally on both sides of bacon and finish cooking in oven for 5 minutes. Cut lettuce into quarters and lay 2 wedges on each plate. Drizzle with vinaigrette and top salad with cherries, pecans, candied bacon and poached pears.

Recipe created by Sous-Chef Christen Angermeier, Quaff On! Bloomington, Photography by April Schmid

Serves 10

For the creme brûlée:

6 cups heavy whipping cream

2 cups whole milk

½ teaspoon salt

3 cinnamon sticks

3 tablespoons cinnamon powder

1 cup sugar

½ cup honey

18 egg yolks

For the compote:

5 red pears peeled, cored and stem removed

4 ounces dried cherries

1 cup Quaff On! Hare Trigger IPA (or other IPA or pale ale)

3 tablespoons sugar

whisk in cinnamon powder, ½ cup sugar and

Bring cream, milk, salt and cinnamon sticks to a light boil. Turn off heat and steep for 30 minutes to an hour. Strain mixture through chinois or strainer with cheesecloth, reserving liquid. Return liquid to sauce pan and honey. overcooked. with crème brûlée.

Bring to a simmer until sugar is dissolved. Whisk while warming and strain mixture through chinois or strainer with cheesecloth, reserving liquid. Whisk egg yolks with ½ cup sugar until well combined.

Slowly whisk cream mixture into egg yolks, ladle by ladle, making sure each addition is fully incorporated before adding the next, until fully combined and consistent.

Fill ramekins to top with crème brûlée. Bake in water bath at 300° for 30 minutes, until set in middle but not

While crème brûlée is baking, prepare the compote. Dice pears while bringing beer, sugar and cherries to a simmer. Add pears to liquid and simmer until fruit is cooked. Add liquid and/or sugar if more sweetness or liquid is needed. Serve

JANE SIMON AMMESON

In the fall, as jewel-colored leaves drift slowly across the back byways in the area of Northwest Indiana called Amish Country, it is possible to catch glimpses of life as it was lived over a century ago. Young boys navigate horse-drawn wagons filled with a cornucopia of fresh vegetables down dirt roads; girls dressed in homemade dresses and matching bonnets in the palest of pastels drive buggies past farms set on squares of green.

I have my favorite places to stop when I’m traveling through this 19th-century rural landscape and the first is always Country Lane Bakery, just seven miles south of Shipshewana on County Road 43. Like most Amish homes and businesses, it is a plain white building. Inside, even without electricity, it buzzes with visitors who all know to get here early for the freshly baked rolls, breads, cakes and unbelievable pies.

On my first visit, I arrived at 2pm and, alas, found only one peach cream pie left but oh, it was so good. I’ve never been able to find a recipe similar to the one I ate and so now I’m among the first arrivals on my pilgrimage through some of the best country eating in the state.

Just a few miles north on the same country road, I visit Green Meadow Farms, an Amish farm selling Lady-Finger Popcorn, a tender, very small, hull-less heritage popcorn, as well as fresh eggs, cheeses and meats (depending upon the day) from their self-serve back porch.

For house-prepared Amish-style meals, both Blue Gate in Shipshewana and Das Dutchman Essenhaus in Middlebury know how to cook classic country such as homemade noodles topped with beef or chicken and served with real made-on-site mashed potatoes, biscuits, fried chicken and, of course, more pies. Both places have a bakery, inn, offer carriage rides and shopping.

On County Road 16, which covers the short distance between Middlebury and Shipshewana, watch cheese being made every morning at Guggisberg Deutsch Kase Haus. Then head west to the Dutch Country Market, owned by the Lehmans, an Amish family of eight. Here you can see noodle making using a hand-cranked noodle machine (and buy some too), fresh-from-the-hive honey products as well as nut butters. The noodles, made of only

Next page, clockwise from top left: Country Lane Bakery just north of Goshen. An Amish bakery known for pies and breads, which are baked in propane-fueled ovens because of this self-sustaining religious group’s belief that reliance on public power ties them too closely to the outside world.

Quilt Garden at Das Essenhaus: Amish Country is known for its beautiful quilt gardens, blankets of blooms planted to replicate classic and new quilt squares. Das Essenhaus is a delightful restaurant and bakery complex with carriage rides, a hotel and boutique shops.

Photo provided by Amish Country/Elkhart County CVB.

One of the many joys of driving the back roads in Northwestern Indiana’s Amish Country is coming across bake sales like this one, raising money for local Amish schools.

The oldest continuously operating grist mill in the state, the Bonneyville Mill, between Bristol and Middlebury, continues to turn out flours and meals with the heavy turns of the mill wheel—just as it did over 150 years ago.

durum wheat flour, eggs and water, are packaged under the name of Katie’s Noodles in honor of Mrs. Lehman, who cranks out 48,000 pounds each year with the help of her six children.

Another plus: The Lehmans, like many businesses in Amish Country, annually plant a quilt garden—a mass of blooms replicating either a traditional or new-style quilt pattern. Make spotting them as well as the quilt murals drawn on barns part of your Amish meander.

At one time, every river, creek and stream in Indiana most likely had a mill or two or more, the water generating power to grind grain into flour. The Bonneyville Mill, Indiana’s oldest continuous operating grist mill, first started grinding flour in 1832. Now part of the 223-acre Bonneyville Mill County Park, just east of Bristol, Indiana, on County Road 131, there’s no charge to enter and watch the giant millstones grind corn, wheat, rye and buckwheat, which are packaged and sold at the gift shop across the road.

Interior Wakarusa Dime Store, which opened in 1907 as a general store, is one of many historic structures in this charming small town in Northwest Indiana’s Amish Country. Photos courtesy of Amish Country/Elkhart County CVB.

It’s not all country eating here. A fascinating food scene is taking place in many of the area’s charming 19th-century towns. In Bristol, with its century-plus opera house, stop by for a tasting at Fruit Hills Winery. While in Elkhart, a scenic city where three rivers meet and mansions line the riverbanks, sip 13, an American Black Ale, while munching on the Landimore Garlic house-made pizza with garlic oil, sun-dried tomatoes, artichoke hearts, roasted garlic, mozzarella and goat cheese in the outdoor beer garden at Iechyd Da (the name is Welsh for cheers) Brewing Company.

In downtown Goshen, beautiful Victorian-era commercial buildings house food-centric entities. Kelly Jae’s Café offers small plates and craft cocktails and Rachel’s Bread is an astounding artisan bakery where yummy goods are made in a wood-fired oven. Next door is the delightful Goshen Farmers’ Market, where I buy freshly picked ground cherries (covered with a papery skin like tomatillos and good for pies) as well as other local edibles. There are many more must-stops here— Mattern Meat Butcher Shop, The Chief Ice Cream (voted number one in Indiana) and Venturi’s, which makes certified Neapolitan pizza.

Be sure in all this traveling to take a side road or two. Last time I did I ended up at the Wakarusa Dime Store, where they’re known for their jelly beans, so who knows what treats you might find. But keep in mind that Amish places will be closed on Sundays.

Jane Simon Ammeson is a freelance writer and photographer who specializes in travel, food and personalities. A member of the Indiana Foodways Alliance, Jane is a James Beard Foundation judge for the Great Lakes Region and a member of Society of American Travel Writers and Midwest Travel Writers Association. Read her blog at NWITimes.com/ niche/shore/blogs/will-travel-for-food; Twitter @HPAmmeson.

“When the frost is on the punkin and the fodder’s in the shock”—James Whitcomb Riley

Fall is the time to experience a fresh apple donut, sip on some apple cider, or bake up some pumpkin pie. Here are six exceptional places to visit in Central Indiana for your apple and pumpkin fix.

Anderson Orchard

offers 100 acres of pick-your-own apples and pumpkins. Enjoy hayrides, playground, cider slushes, caramel apples, elephant ears, or apple cobbler.

Craft Fair, September 27 and 28. New this year, October Fest, October 4 and 5.

Hours of operation: M–Sun 8–8

Location: 369 E Greencastle Rd, Mooresville

Stuckey Farm is a working U-pick apple orchard that welcomes visitors. Come and pick from 27 different varieties of apples. Come visit the kids play area “Adventure Acres”, take a free wagon ride, see how they make cider, eat in their picnic area, or just browse through their Country Market.

Hours of operation this fall:

M–Th 9–6, F–Sat 9–8, Sun 1–5

Location:

19975 Hamilton Boone Rd, Sheridan stuckeyfarm.com

Pick you own Jack-O-Lantern from over 18 acres of pumpkins at the Appleworks Weekend wagon rides to the patch begin September 27.

Hours of operation: M–Sat 9–6; Sun 10–6

Location: 8157 S 250 W, Trafalgar

Tuttle Orchards is a favorite Central Indiana destination for apple picking, pumpkin patch, corn maze, hayrides, and more. No general admission or parking charge. Fall activities begin September 6 with Kickoff Caramel Apple Festival

Hours of operation:

M–W 9–6, Th–Sat 9–7, CLOSED Sunday

Location: 5717 N 300 W, Greenfield tuttleorchards.com

McClure’s family-owned apple orchard is a great getaway for the entire family: petting zoo, gift shopping, trolley rides, u-pick apples and pumpkins, wine and hard cider tastings and apple dumplings.

Hours of operation:

You’ll find acres of pumpkins and tons of fun at the Waterman’s Family Farm Fall Harvest Festival, September 27–November 1.

Hours of operation: Indianapolis Festival hours: 9–8 Greenwood Festival hours: TBA

Locations: 7010 E Raymond St, Indianapolis 317.356.6995

1100 N Ind Hwy 37, Greenwood 317.888.4189 watermansfamilyfarm.com

*These businesses were invited to participate in this paid advertisement.

Apple Barn: M–Sat 9–5; Sun 11–5 Café: M–F 8–5; Sat 9-5; Sun 11–5

Location: 5054 N US Hwy 31, Peru

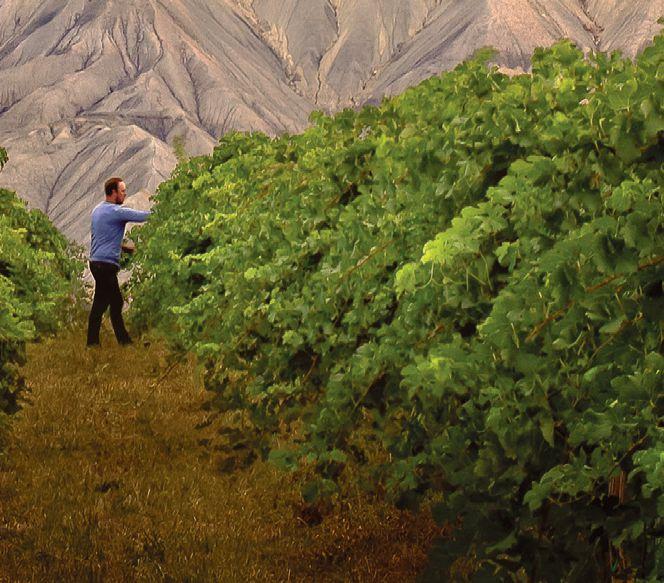

BY TRISTAN SCHMID PHOTOGRAPHY BY APRIL SCHMID

Hops, along with water, barley and yeast, comprise the basic ingredients of beer. Breweries rely on hops to produce flavorful, aromatic beverages. And just as the number of craft breweries in Indiana is quickly growing--to nearly 100 into the fall of 2014, the number of hops farms in increasing, too.

Ryan Hammer, of Three Hammers Farms, is one of the new generation of hops farmers. Hammer tends 400 hops plants in Knightstown, Indiana, known for being the site of the filming of Hoosiers.

“We put in four varieties of ten plants each in the spring of 2012. We had good success with the first-year plants and sold eleven pounds of CTZ to Sun King Brewing that fall,” Hammer says. “They used the hops to wet-hop a small batch of Osiris pale ale and called it Three Hammers Wet Hopped Osiris.”

Hammer was hooked after that positive experience. “We tripled our plants the next year, then doubled our plants this year to expand to ¼ of an acre.”

In addition to expanding the farm, Hammer has expanded the va-

rieties of hops he grows.“We planted Cascade and Chinook in 2013 and also added more of the Nugget and CTZ to fill the rows. That year, Sun King purchased Cascade and Chinook wet (undried) hops. They used those in their Wet Hopped & Sticky which might be the first wet hopped beer in Indiana made with Indiana hops.”

Other breweries in Indianapolis have used locally grown hops from Three Hammers, too. “Flat 12 used wet Nugget hops for an all wet-hopped beer, and Indiana City Brewing Co. used Chinook in their Red Collar Imperial Amber as well as Nugget in another beer. Sun King and Indiana City are slated to brew both of those beers again this year with our hops.”

Farming hops brings challenges not found with other common Indiana crops like corn and soy. Hammer says it’s expensive, partially because of the required trellis system, and also because the plants need a lot of water, especially late in the season when rainfall is infrequent.

Water can be a problem in a different way, too. “With all of the water going to the plants, mildew is a big issue. Powdery and Downy

Unexpected weather is an issue with hops. Rosenbaum says many of his hop vines were blown down during an intense storm and didn’t produce usable cones this year.

Hops plants can take more than 4 years to yield a full crop.

Below: Shadow, a baby water buffalo born and raised at Loesch Farm, often goes up to sniff the bitter Cascade hops fines grown at the farm.

mildew are what drove hop production out of the midwest to the Yakima Valley (Washington state) where it is much drier, but they still deal with those problems there too,” Hammer says.

Monoculture farms like Three Hammers aren’t the only places in Indiana producing hops; some breweries are even getting in on the action.

Bloomington Brewing Company grows organic Cascade hops at their Loesch Farm on the west side of Bloomington. Head brewer, Floyd Rosenbaum, has been growing the hops for six years and has harvested them in late summer for the past five years, using them shortly thereafter for the brewery’s annual Homegrown Ale.

Though Bloomington Brewing Company doesn’t plan on selling their hops, the crop has generally done well. “We’re planning on getting some more plants, about 50, next year,” Rosenbaum says.

There’s plenty of room for growth in the Indiana hops industry, says Ryan Hammer.

“I would say we are behind Michigan by about 5 to 10 years as far as our growth in craft beer and the agriculture that supports it. I don’t believe this is a bad thing. The growth of craft beer and its supporting industries is just starting to ramp up and is still not up to pre-prohibition levels. I don’t think we will grow, in size, to surpass the Pacific Northwest, but I don’t think that is our goal, either.”

Hammers says growing hops in Indiana is important for our communities. “The closer the person growing the food or product is to the person consuming or eating the food is nothing but good for every aspect of human culture. There is something very special about being able to exchange hard-earned money and buy and ultimately consume something that someone put passion and time into to create. People are seeing that now more than ever before.”

Tristan Schmid is Communications Director for Brewers of Indiana Guild, a non-profit trade association representing all of Indiana’s nearly 100 small breweries. When he’s not spreading the word about Indiana craft beer, he’s walking his dogs, riding his bike or eating local food.

This past summer, Purdue Extension offered webinars about growing hops. The university is growing hops at their Meigs Farm.

The cost of establishing a 1-acre hop farm is about $13,000, according to the SARE program (Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education).

Lupulin, a brownish-yellow powder, is the active, aromatic ingredient in hops and has mild sedative effects.

Indiana has nearly 100 craft breweries, though the vast majority of beer purchased in the state is still from major companies like Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors.

The Indiana State Fair introduced craft beer for the first time to attendees.

WHEN

S ATURDAY, S EPTEMBER 27, 2014 6:00 PM TO 10:00 PM

The Food and Cocktail Reception starts at 6:00 PM, Chef Awards at 7:45 PM, and Music & IndyCar Activities from 7:30 til 10 WHERE

DALLARA INDYCAR FACTO RY 1201 MAIN STREE T S PEEDWAY, INDIANA, 46224

$40 per person (Includes entry, food tasting, 5 tip tickets and cookbook)

$350 per table of 10

Purchase your tickets online at www.arcind.org, contact Spencer Valentine at 317-977-2375 or email at svalentine@arcind.org.

Illustrated By Sofia Puga

When harvested early, the leaves of horseradish root can be used as lettuce

1

2

Allow root to dry and pack in bins between layers of moist sand or sawdust

Place in a dark location with humidity over 90% and temperature between 32-40°

*Over 45° the root gets woody and will sprout

Optimal Storage time is 6-9 months : Flavor lessens over time

A

Delay Harvest until October or Early November in cooler weather

First Dig up entire root

Second Cut off all leaves of root

Last Trim off new growth roots with top of root being square.

Store root growth loosely in plastic bag in the fridge for spring planting

By Jennifer Rubenstein

Raw horseradish is the traditional Bitter Herbs of Passover Seders

3

Peel horseradish or it will lose flavor

Fumes are strong: stay upwind or work near a window or outdoor

It’s mustard oil (flavor and hotness) dissipates within 30 minutes when exposed to air After grating or dicing, cover with white vinegar to prevent oxidation

*The longer you wait to add the vinegar the hotter it will be.

Less hot add vinegar 1-2 minutes

More hot wait 6-8 minutes

Sinus Infections: Instant relief hold 1/4 teaspoon of freshly grated root in mouth until taste is gone.