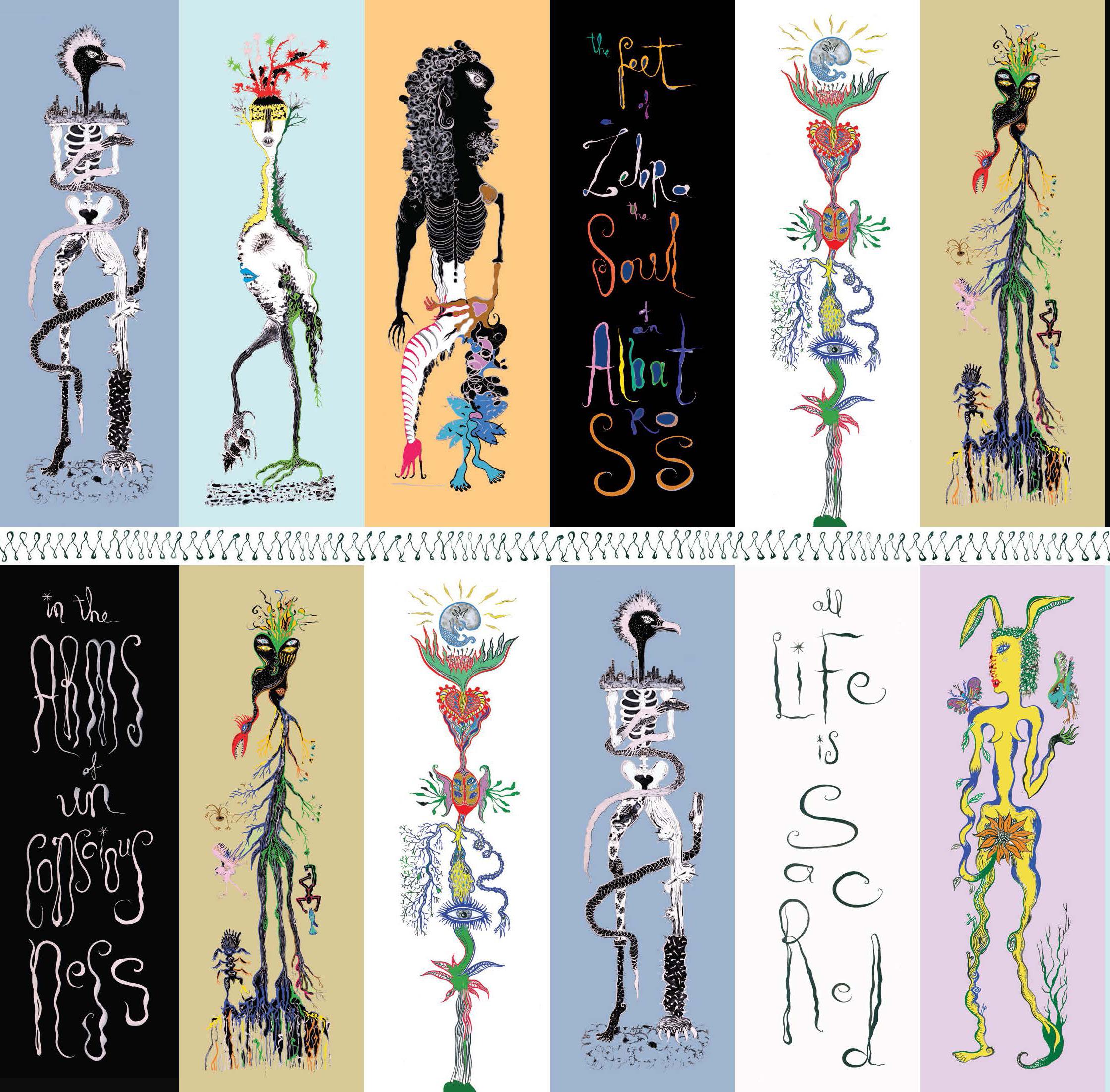

in the arms of unconsciousness: travelling into the feminist surreal

CARRIE KIBBLER CURATOR

In the arms of unconsciousness: Women, feminism and the surreal, is a cross generational exhibition featuring the work of 22 significant female Australian artists whose practices explore ideas of the surreal and feminism. Featuring newly commissioned and recent works, the exhibition includes paintings, ceramics, photography, sculpture, installation, video works, drawings and collage.

The exhibition focuses on contemporary art practices within Australia today, featuring recent works by artists who have been hugely influential figures in Australian art practice, alongside younger generations of leading artists.

The idea for this exhibition began in early 2017 after meeting with artist Louisa Chircop and discussing her work and its relationship to Surrealism and feminism. A subsequent meeting with artist Madeleine Kelly revealed similar influences in her work, leading

to the investigation of Australian women artists working today and exploring these themes. While it seemed there was a groundswell of artists engaging with surreal and feminist themes at the time, it certainly wasn’t new, as a number of midcareer and established artists have been working with these themes for decades.

Artists who were actively making and exhibiting work during the second and third waves of feminism in the 1970s-1990s in Australia include Jill Orr, Vivienne Binns, Pat Brassington, Julie Rrap, Jenny Orchard, Patricia Piccinini and Anne Wallace. Artists such as Del Kathryn Barton, Deborah Kelly, Lynda Draper, Caroline Rothwell, Louisa Chircop, Madeleine Kelly and Freya Jobbins were beginning to make work during the 1990s and were influenced by the artists and popular culture of this period.

More recently, a younger generation

2

of female artists such as Marikit Santiago, Honey Long & Prue Stent, Lucy O’Doherty, Juz Kitson, Kaylene Whiskey, Amanda Williams and Jelena Telecki are working with elements of the surreal, the psychoanalytic, the unconscious and the fantastical in their practice.

Artists were referencing dreams, the subconscious, strangeness and the uncanny, the fantastical, or psychologically unsettling images, combined with the lived experience of women and a reclaiming of the female body. Seeing so many artists

working in with these ideas led to the development of the exhibition.

Later that same year Dreamers Awake opened at White Cube in London, exploring the enduring influence of Surrealism in women’s art, and in October, Whitney Chadwick’s Militant Muse, which explored female friendships among the Surrealists, was published. Seeing these themes arise in an international context cemented the importance of this exhibition and how Australian artists are contributing to the wider conversation around Surrealism and feminism.

4

As this exhibition has developed, there has been a resurgence in projects that focus on both women and Surrealism. Major exhibitions have looked at Surrealism’s wide-spread influence post WWII and importantly looked at the diversity of Surrealism and surrealist artists, particularly artists from diverse cultural backgrounds and those living in countries outside of Europe. These include Surrealism Beyond Boarders, 24 February – 29 August 2022, Tate Modern, the first exhibition to look at artists and Surrealism across the globe from the 1920s to the 1970s; Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 9 April – 26 September 2022 and Museum Barberini, Potsdam, 22 October 2022 –29 January 2023.

While Frida Kahlo’s enduring legacy and celebrity status has seen a continued interest in and love for her work over many decades, more recently there has been a focus on other women surrealist artists and their influence on younger generations. These exhibitions have shifted the gender balance by recognising the important work of Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Vara who have been the subject of major survey exhibitions.

A renewed focus on women artists and their place in Australian and international art history has coincided with the current fourth wave of feminism which has had far reaching success in drawing attention to the rights of women globally. Beginning

in 2012, it has largely been driven by increased political activism and significantly, the use of social media as a platform for protesting and the sharing of knowledge.

In the context of the artworld there is also increasing recognition of women and women artists throughout history and steps to improve gender parity in exhibitions, collections and workplaces. In 2020, the NGA launched the landmark exhibition Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now which is one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of art by women ever assembled in Australia.

Sitting within this renewed global interest in women artists and Surrealism, In the arms of unconsciousness: Women, feminism and the surreal explores ideas of feminism and the surreal, proposing an intrinsic link between the two in contemporary Australian art practice over the decades.

The artists in this exhibition work with elements of the surreal to explore, disrupt or challenge traditional representations of the female body and provide unique perspectives on personal and political issues which resonate today.

opposite: Anne Wallace Pythoness 2022

previous page: Louisa Chircop

Il-grotta ta’ Louisa 2023 installation detail

5

8

ESSAYS ESSAYS

9

Women, Feminism & the Surreal

What is the reality of the artist?

Are Surrealist artists “inspired by an early unforgettable moment?” 1 . Is there an ‘intrinsic link between feminism and Surrealism, particularly in Australia?’ These are some of the fundamental questions posed by the 2023 exhibition In the Arms of Unconsciousness: Women, Feminism and the Surreal’.

When Pat Brassington (b.1942), arguably Australia’s most significant living Surrealist artist, was asked whether she had an unforgettable defining moment, a throaty laugh preceded her comment, “I have lots of defining moments. Whether they determine the course of my art practice …. well, I’m not going to divulge that! The work of art that is out there is my reality.” 2 .

10

COURTNEY KIDD

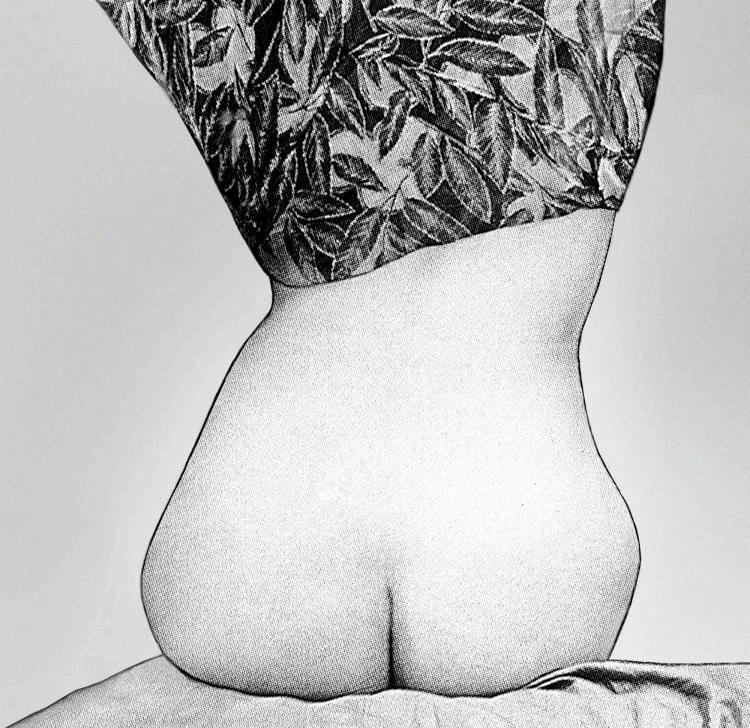

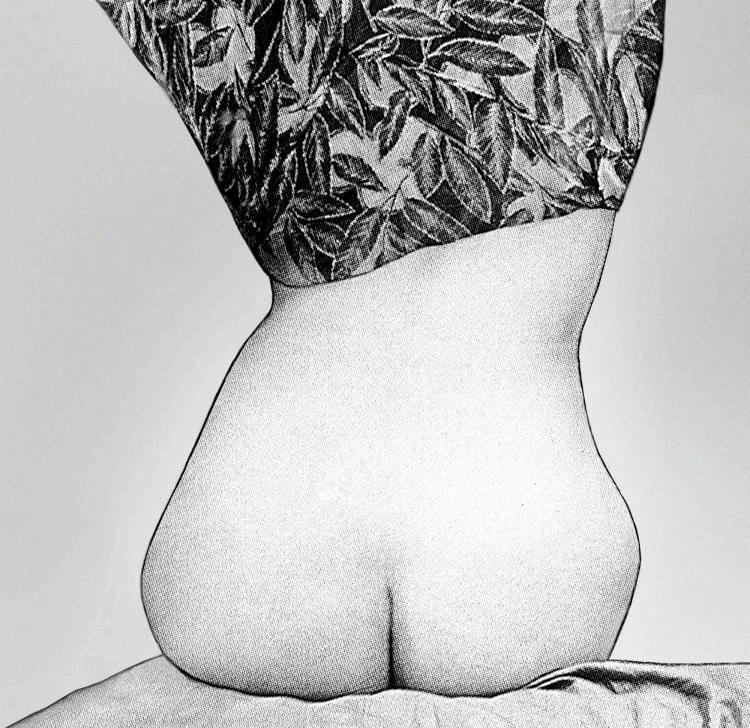

And it is a seductive yet disturbing reality masking a complex mindscape of narratives. The Tasmanian artist’s practice, informed by feminism and psychoanalysis, manipulates the medium of photography to question identity politics. Such examples on exhibition as The Wedding Guest, 2005 where a penile slug slides from under a curtain and Pillow Talk, 2005 where a young girl’s naked legs splay out from under a pillow covering her pudenda, are confident pictorial worlds in Brassington’s Surrealist play with the enigmatic. Later monochromatic images Split, 2020 and Enveloped, 2020 show the female body as unsettlingly beautiful, a clever nod to the previous century’s Surrealist take on women as either muse or sexual object.

It is thirty years since the major exhibition ‘Surrealism: Revolution by Night’ opened at the National Gallery of Australia placing Australian Surrealist artists within an international context. Then followed in 2015 the National Gallery of Victoria’s ‘Lurid Beauty: Australian Surrealism and Its Echoes’. It specifically focused on Australian practitioners and how subsequent generations of artists were influenced. These exhibitions have all been underpinned by waves of feminism that accelerated in the 1970s to the sound of Helen Reddy’s 1971 Grammy Award Winning song I am Woman and continued to impact the way in which female artists were rethinking and reclaiming how their bodies were to be represented.

Artists, Vivienne Binns b.1940, Pat Brassington b.1942, Julie Rrap b.1950, Jenny Orchard b.1951, Jill Orr b.1952, Patricia Piccinini b.1965 and Anne Wallace b.1970, were making art in Australia, while in another part of the world theoreticians Lucy Lippard and Whitney Chadwick were advocating for female representation in institutional collections and a feminist voice that questioned gender, sexuality, politics and art. Lippard’s visit to Australia propelled the establishment of the feminist Women’s Art Movement while the work of another American, artist Judy Chicago inspired such exhibitions as ‘The D’Oyley Show/An exhibition of women’s domestic fancywork’, 1979 at Watters Gallery, Sydney. It heightened a renewed interest in lacemaking, along with the use of fabrics and fibres in sculpture, all demanding credible place alongside bronze and steel.

Chicago’s seminal work, The Dinner Party 1974-79, used doyleys and other ‘unconventional’ materials to articulate new modes of representation. Later in her 1996 memoir Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist she contended that women must work outside mainstream designations in order to define their art and shape new cultural symbols.

In Australia Binns (a Canberra based former Watters artist) was shaping feminist culture, exhibiting anarchistic tendencies in her practice

11

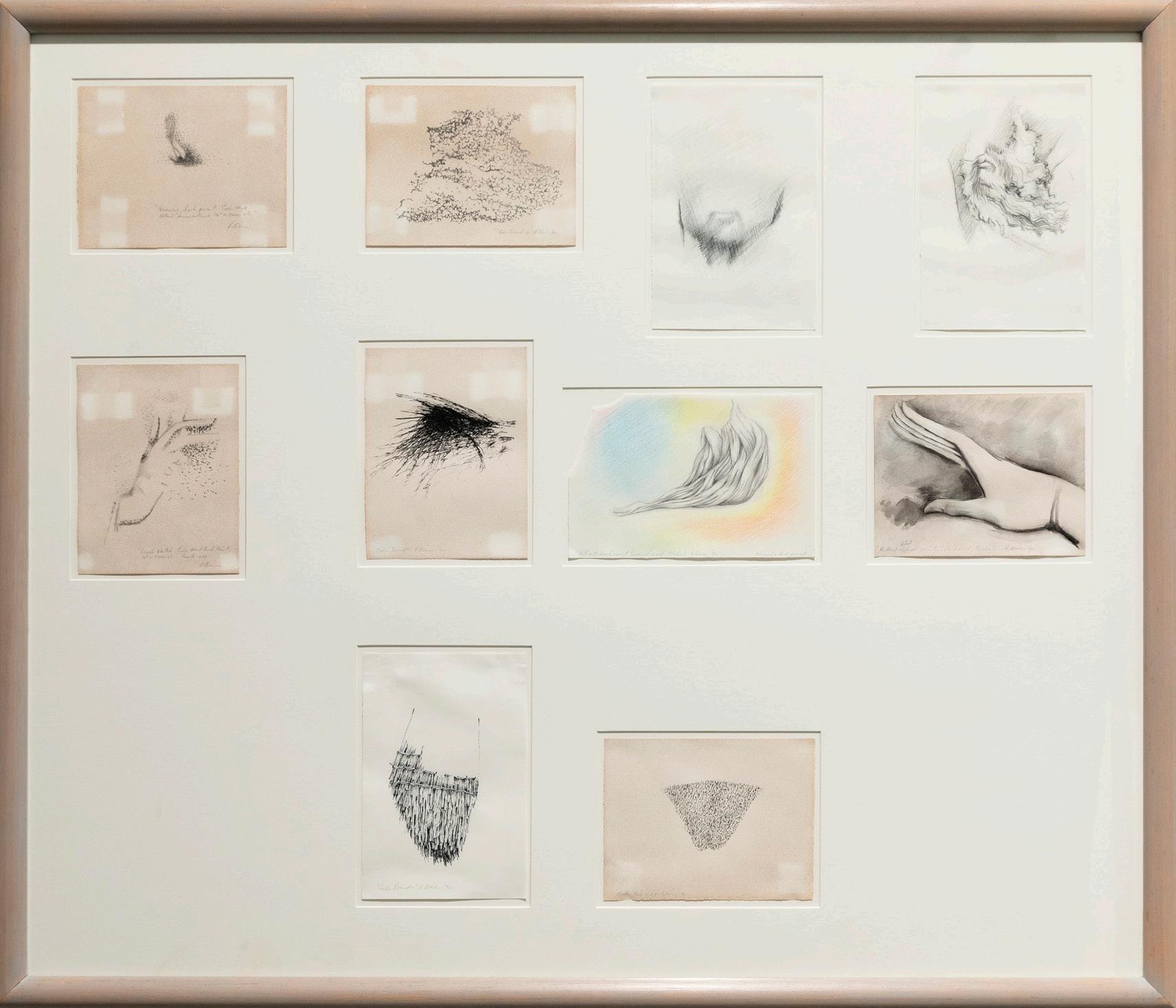

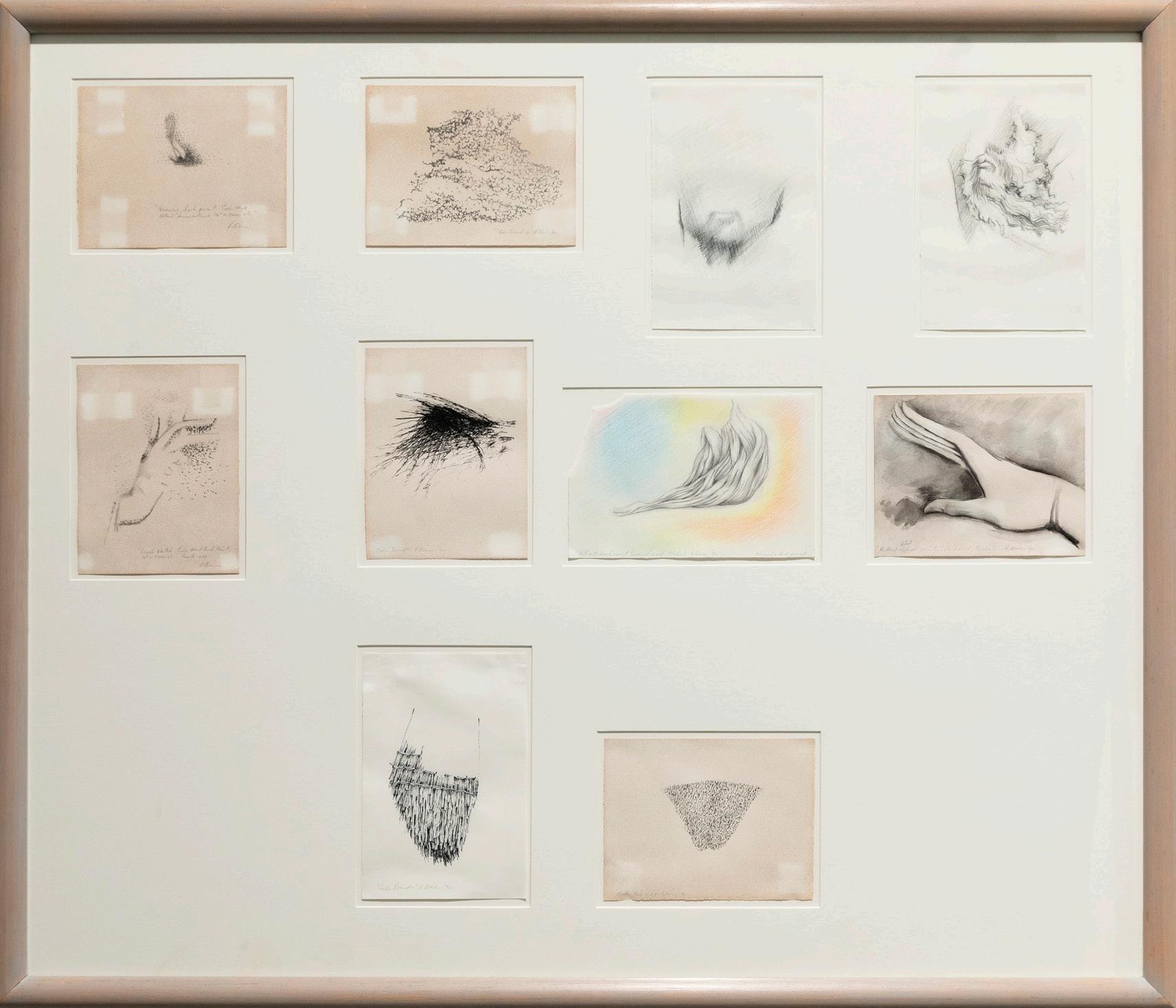

and making art that tormented the art historical cannon. Her Drawings of God, 1990 in this exhibition are fresh, spontaneous interpretations of images from art history relating to gender, art and random objects and recall the original spirit of Surrealism being to apprehend the real world in dreams. She notes, “The main thing I got from the Surrealists was automatic drawing, allowing the subconscious to come to the fore, dreams and chancechance particularly, as it is one of the ways to get in touch with the subconscious.” 3 .

As Rrap reminds us, all art is in conversation with its own history. Her suite of Instruments made in 2015 are a witty dialogue between Surrealism and feminism, where the artist’s purposely cast hands in aluminium give them a machine-like reference, their titles i.e. Instrument: Peeping 2015 and Instrument: Whistling 2015 assigning a function to women, a reference to the way in art history women perform as muses. The Instruments, installed as if an imaginary orchestra, play to a silent audience, the viewer. Rrap says, “In the 1980s I came to love the incongruities of Magritte’s work. He is like a trickster and that is what

attracts me to the Surrealists, they have humour, their disjunctive use of the body is intriguing, uncanny.” 4 .

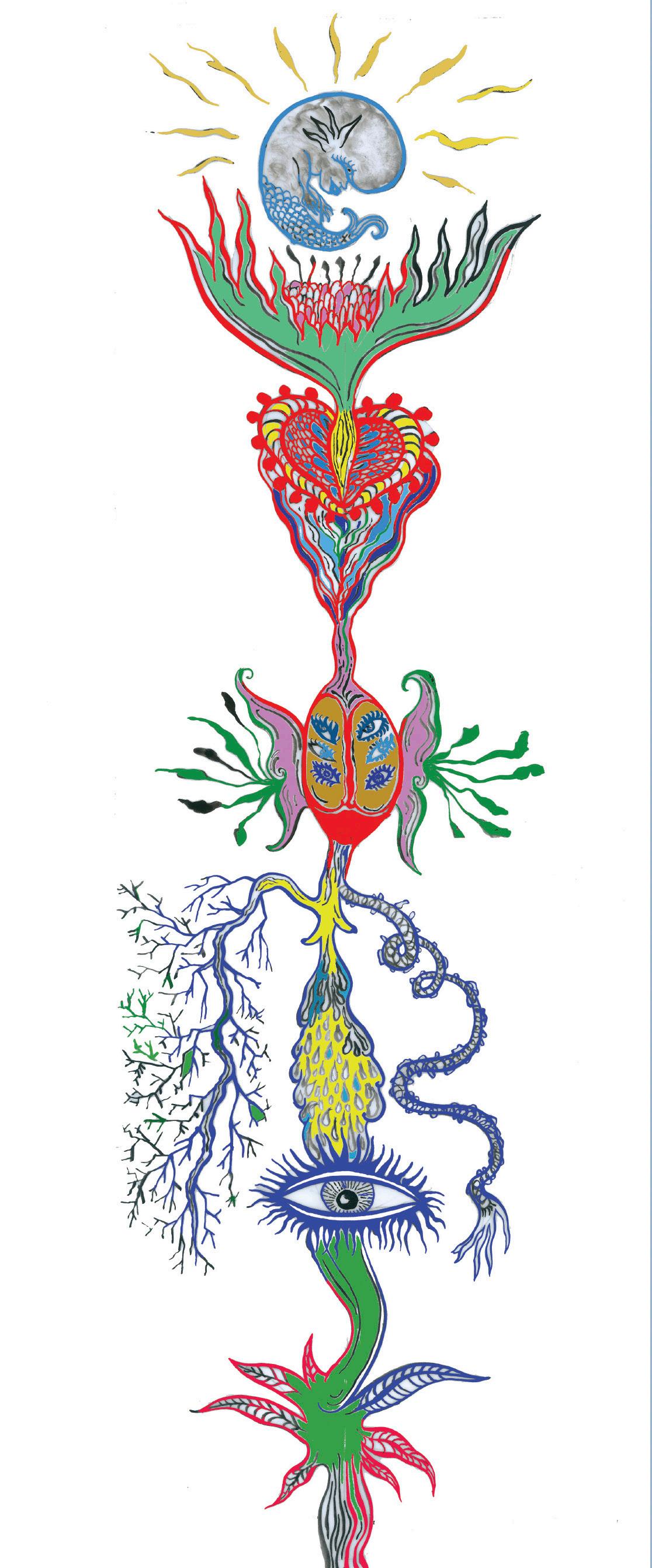

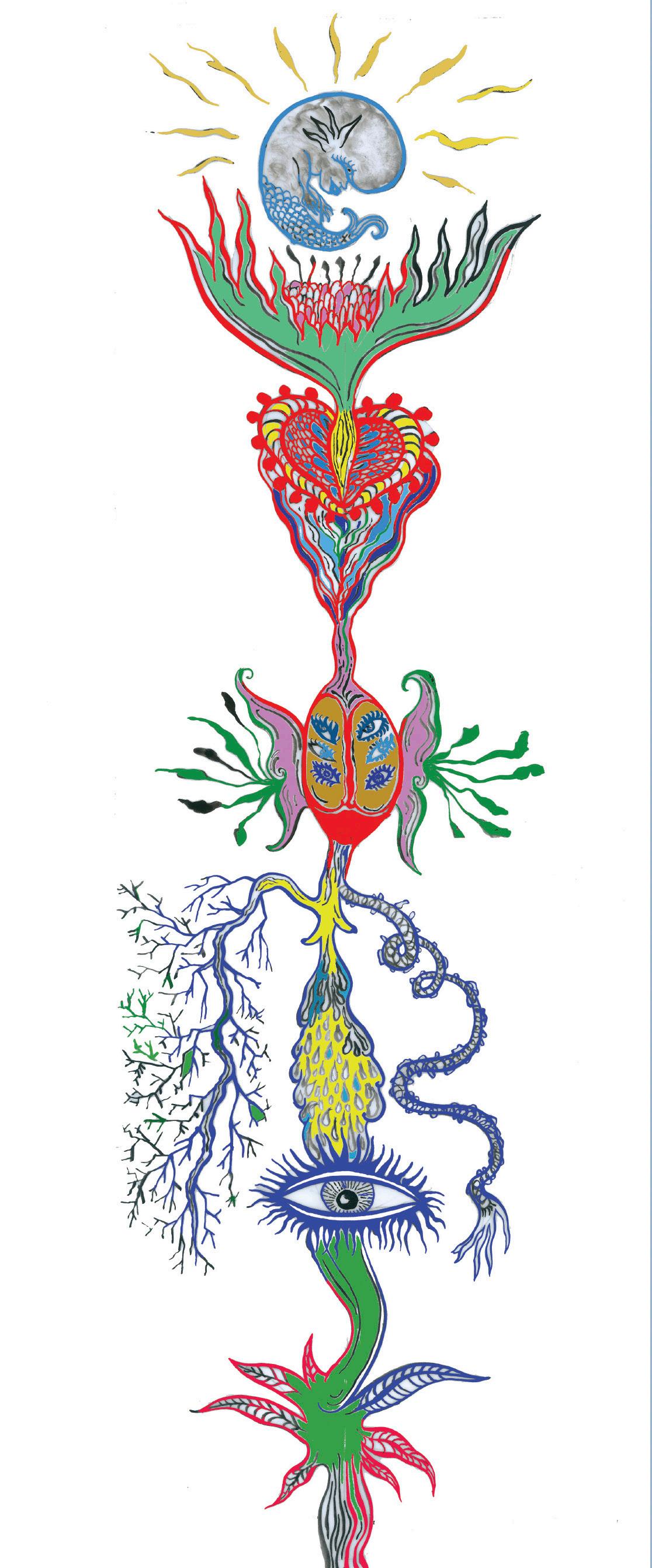

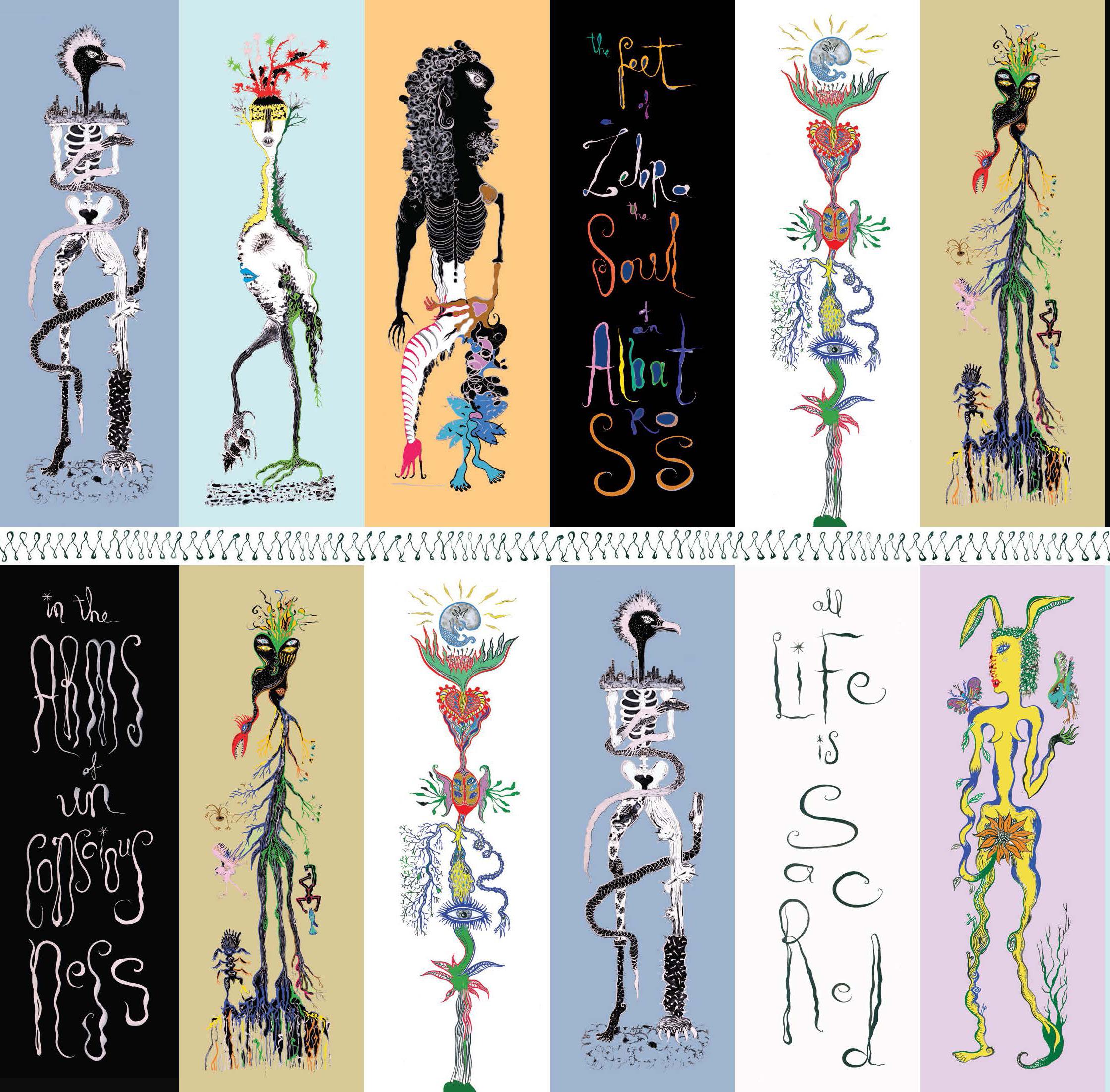

The other-worldly, the eldritch, the uncanny are ignited in Jenny Orchard’s wonder filled cacophony of totemic forms and vessels that explore imaginative states of being and says the artist “signify natural growth, change and endurance in our increasingly digitally constructed world.” A defining moment for Orchard … “When I was six and living in Zimbabwe I was sitting in the front seat of a Landrover with my father on a hunting trip. He shot an animal. I felt paralyzed. I felt out of my body, have been a vegetarian ever since. My aim is to evoke otherness, strangeness.” 5 .

Jill Orr sees her body as an ‘emotional barometer’ placed between the natural and the unnatural world. A key figure in the performance art movement of the 1970s, she cites Simone de Beauvoir and Germaine Greer as resonant influences. Orr’s photographic documentation of a live performance at Abbotsford Convent is haunting and strange. The convent took women from the streets and gave

previous page:

Vivienne Binns

Drawings of God 1990

opposite: installation image featuring (foreground) Julie Rrap Instrument: Framing 2015 and (background) Pat Brassington

12

them employment. The narrative of struggle, says the artist, “extends beyond the architectural site to the banks and waterways of the Yarra, a place of struggle for the Wurundjeri people negotiating cultural dissemination.” 6

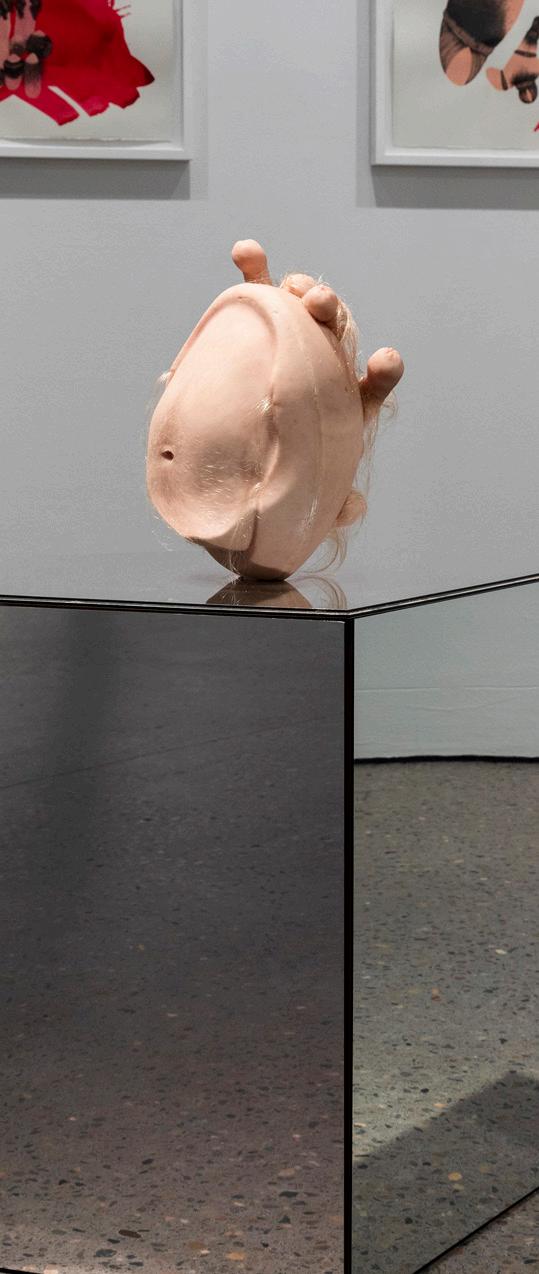

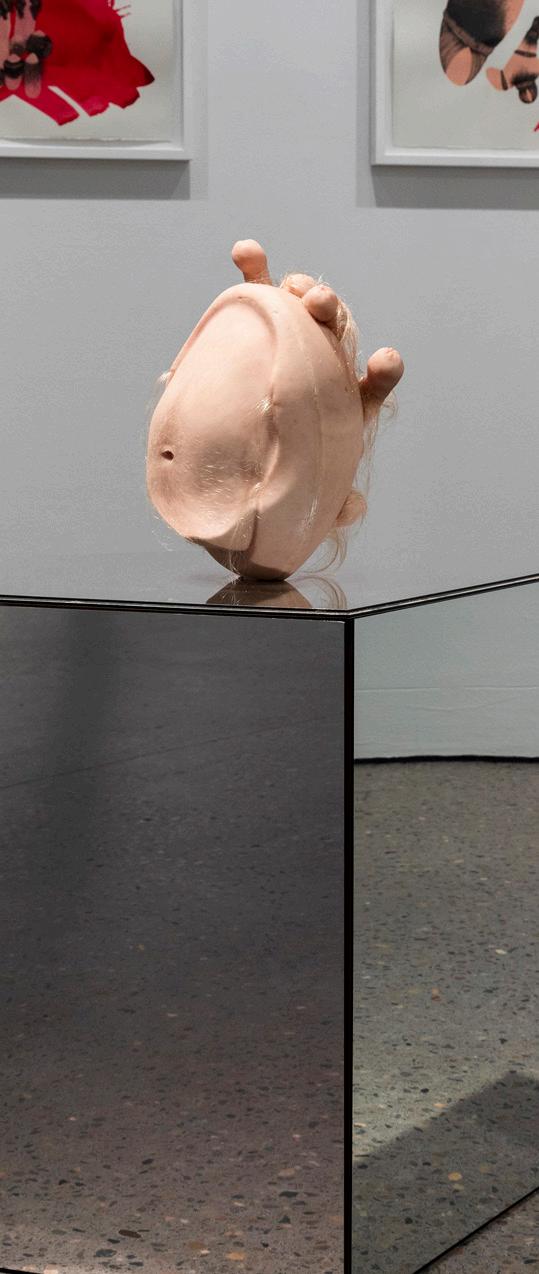

“Hair is one part of the body that we can change to alter identity” 7., says Piccinini whose hybrid figurative sculptures such as Egg/Head, 2016 offer a scary portent of what could lie ahead for the human race should it shirk ethical treatment of life forms. In the artist’s rigorous questioning of what it means to be human she offers art as salve to counter the grotesqueries of the contemporary world, evidenced in her atmospheric Meditations on the continuity of vitality, 2014, beautifully propelled via an automatic drawing technique in ink and gouache.

For Anne Wallace the real and the unreal hover in a liminal space, the female figure, alien, attests to the Surrealist tenet of women as unknowable and mysterious through metaphors of the body. Wallace recalls “growing up in a time when women didn’t seem to own images of themselves, endured representations of themselves,” 8. and in Nerves, 2017, the mirror, and Pythoness, 2022, the candle, could work as a scry foretelling the future of feminism in a world where feminism is no longer gender specific. The mood is unsettling, volatile.

And it is a volatile pulse that underpins In the Arms of Unconsciousness: Women, Feminism and the Surreal, the varied works from these history- making women negotiating a unique space where feminism and Surrealism meet to take the mind beyond daily reality to arrive at a truth. Significantly, what this timely exhibition does is propel unique dialogue, its accent Australian, distinct from the swathe of postcolonial and postmodern words and images that dominated the decades they were working in.

1 The full James Gleeson (1915-2008) quote is “Many of us live our whole lives inspired by an unforgettable moment experienced. I was about the age of four and I remember being in the garden with my mother. She was picking fruit and fell out of the loquat tree.” As told to Courtney Kidd for NSW Artnotes, Art Monthly Australia, 2002, p. 51.

2 Conversation with Pat Brassington 9th June, 2023.

3 Email Vivienne Binns 15th July, 2023.

4 Conversation with Julie Rrap 22nd July, 2023.

5 Conversation with Jenny Orchard 8th July, 2023.

6 Conversation with Jill Orr 24th July, 2023.

7 Conversation with Patricia Piccinini 24th July, 2023.

8 Conversation with Anne Wallace 25th July, 2023.

14

above: Jill Orr Laundry 01 series 2019

next page: exhibition installation image

15

Exquisite corpse

CHLOÉ WOLIFSON

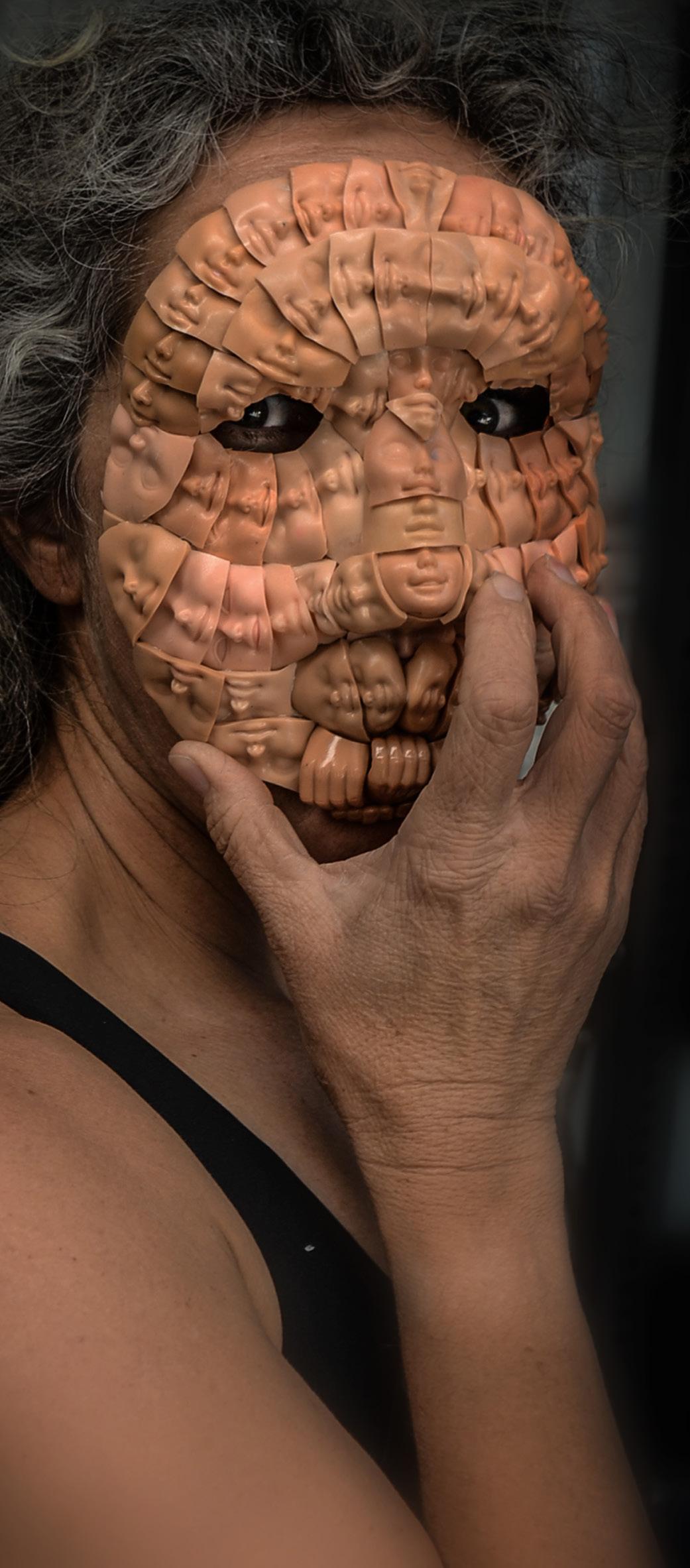

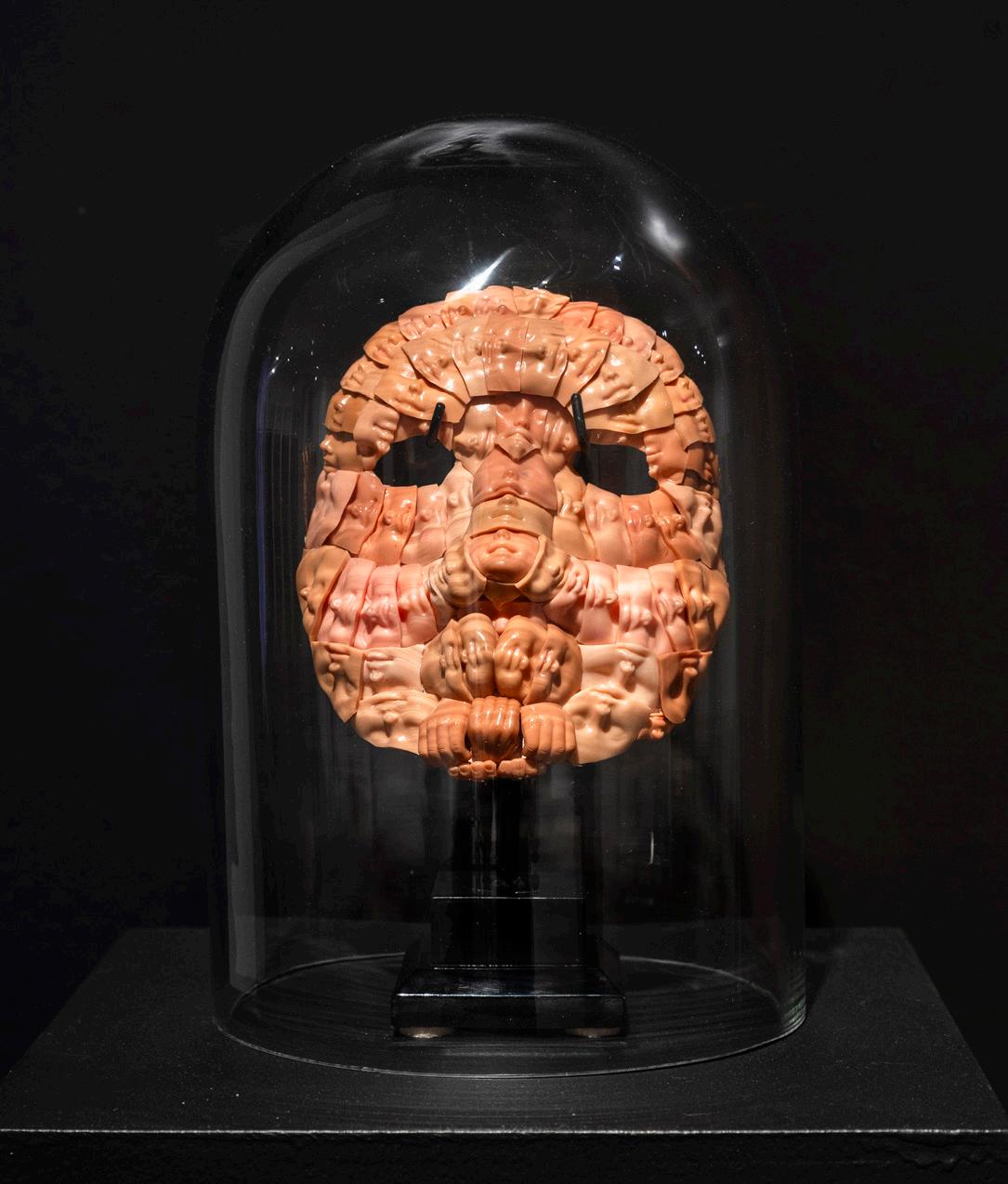

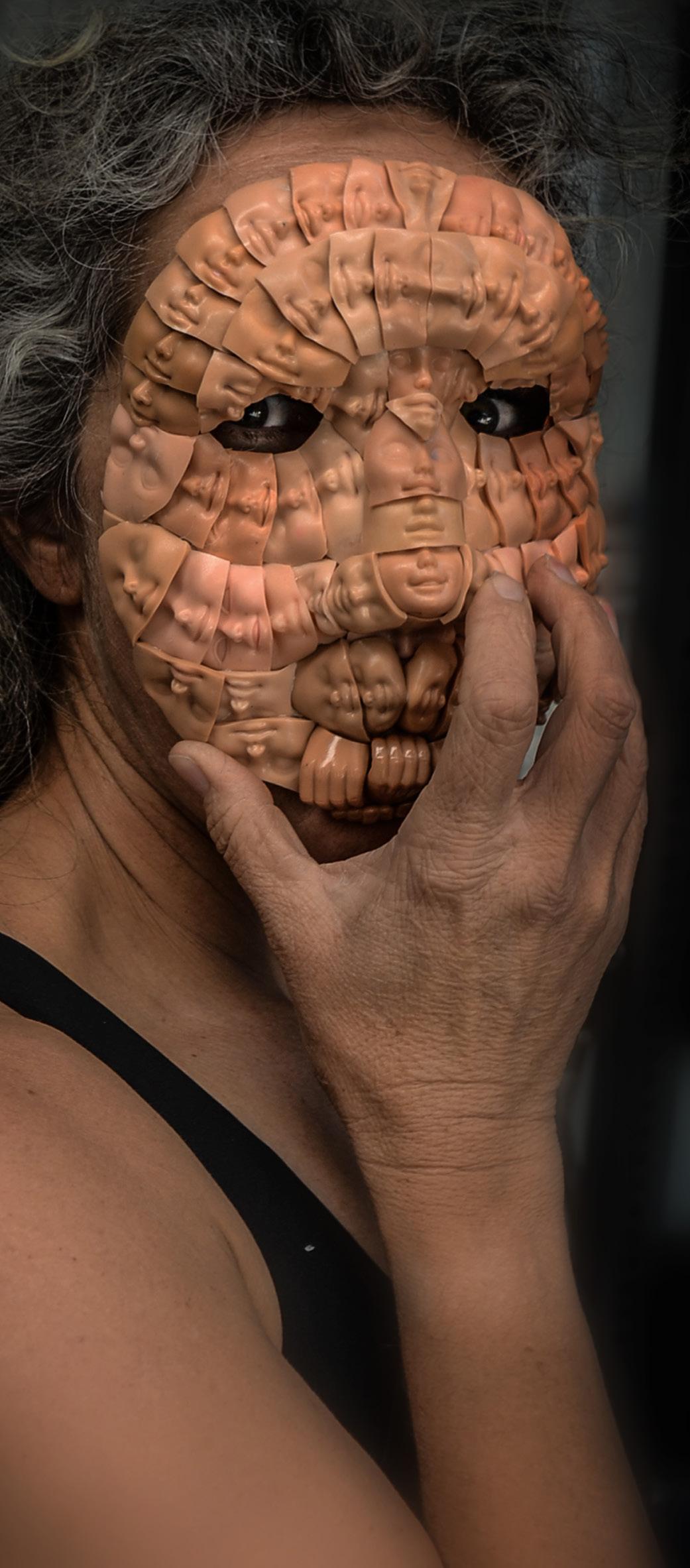

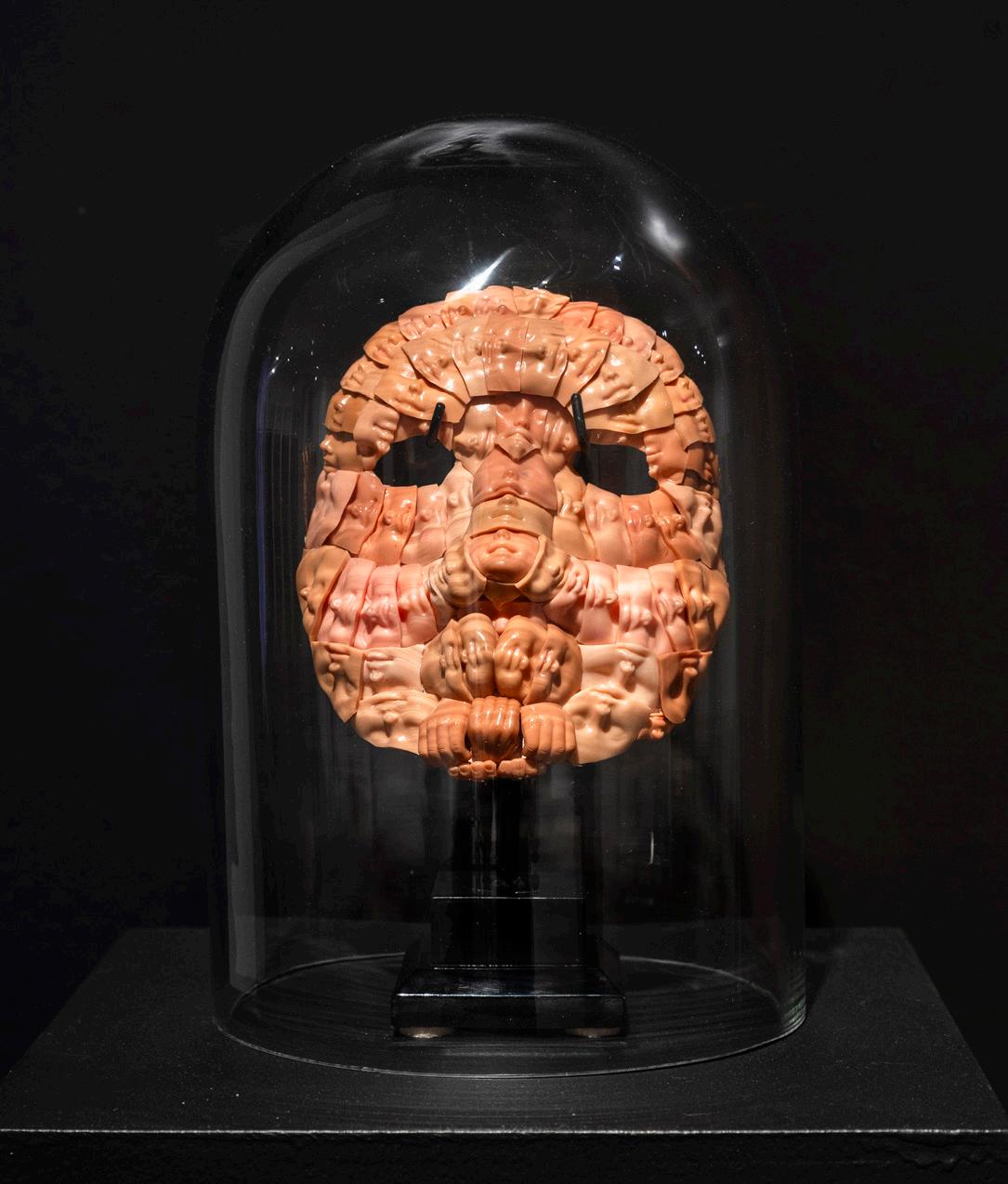

I’m at the dentist having my teeth cleaned; my 5-year-old child sits quietly in the corner of the room. “My wife and I saw the Barbie movie last night,” the dentist says. His hands are in my mouth; I remain silent. I think about Freya Jobbins’ work TODAY IS THE LAST DAY THAT I AM USING WORDS (2023). A photograph features a woman wearing a contemporary version of a Moretta mask, an object popular in Venice and Paris in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Secured to the face by a button held between the teeth, the Moretta mask allowed a woman to choose to remain silent, anonymous, and free of the male gaze. Speak, releasing the button, and the mask will fall away. Jobbins’ work is constructed from the faces of dozens of massmanufactured plastic toy dolls, while the button for biting is made from the face of a Ken doll, which the artist melted in a sandwich press.

18

above: exhibition installation image

***

Jobbins’ work takes its title from the first line of the Madonna song Bedtime Story (1994) , the lyrics of which also inspired the title of the exhibition In the Arms of Unconsciousness: Women, Feminism and the Surreal. A century ago, André Breton published his Manifeste du surréalisme, defining the movement as “psychic automatism in its pure state… Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.” Woman’s presence from the early days of the movement was as an Other, but women artists were and continue to be drawn to its emphasis on freedom of personal and artistic expression, abandonment of logic, and the creative potential of the unconscious.

Bodily experience is foregrounded in the Surrealist work of women artists, including those in this exhibition, who subvert objectification and reclaim the fragmented female body as a medium for imagination, irony and resistance. They mine the unconscious, conjuring and reassembling dreams, images and objects in the pursuit of alternative realities. The artists in the show take unique yet parallel approaches using shared motifs and methodologies, as part of surreal investigations into the dichotomies of female experience.

***

Jobbins’ subject Kayte’s eyes peer out from behind the arrangement of blank-eyed dolls faces. Kayte’s hand rests at her chin and cheek, and a few dolls’ hands can be seen behind it forming the mask’s chin. From a distance the mask might appear as a lumpen grotesque form, while from up close the dolls features come into focus creating a disembodied effect which harks back across Surrealist visual history: to the scene in Madonna’s Bedtime Story music video (1995) where the singer’s eyes and mouth are reversed, to Frida Kahlo’s 1949 painting Diego y yo in which Diego Rivera’s face is superimposed on the artist’s, to René Magritte’s Le viol (Rape) (1934), in which a woman’s torso doubles as a face.

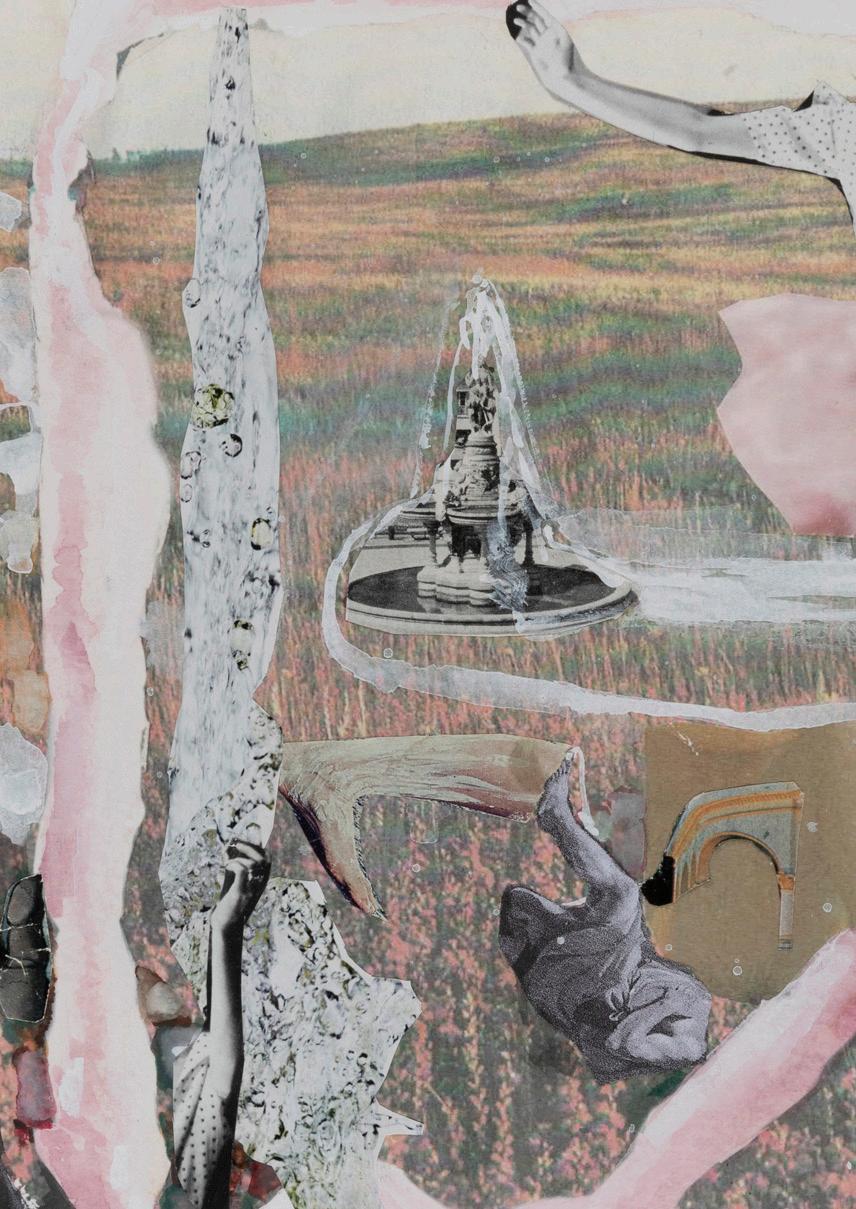

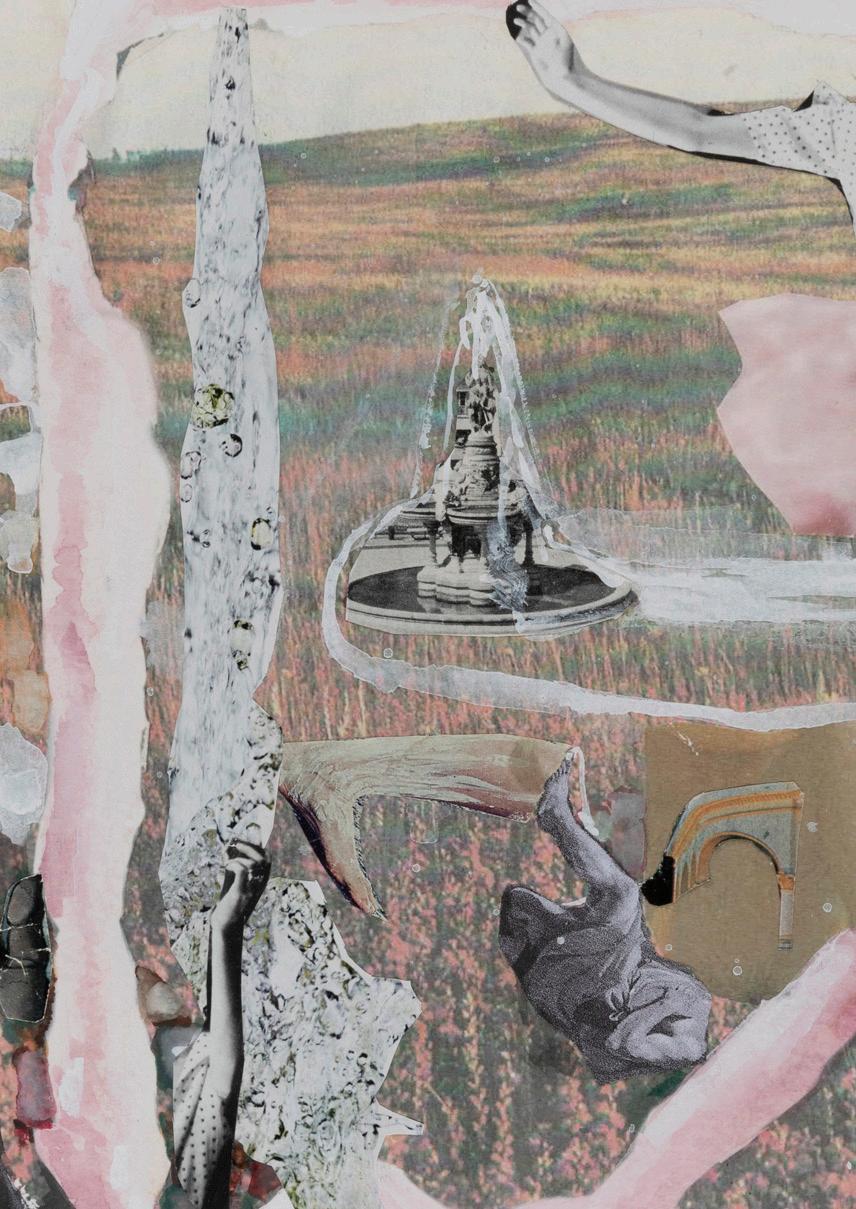

Louisa Chircop’s installation work Il-grotta ta’ Louisa (Louisa’s Grotto - translation from Maltese) (2023) is also multifaceted – a self-portrait constructed through dismemberment and disembodiment. The work’s title refers to the grottos Chircop’s migrant grandparents built in the backyard of the family home, which the artist felt were an alien presence in the Australian landscape – a situation which paralleled her own feelings of identity. Chircop’s shrine-like mixedmedia installation features handbuilt painted ceramic elements alongside painting and collage. Disembodied limbs and headless figures gather around a selfportrait of the artist as a fountain, in an exploration of the spiritual,

19

the sexual and the subconscious self. Milky-white streams bursting forth from breasts and mouth, and glistening pearlescent glazes, skirt the zone between purity and temptation.

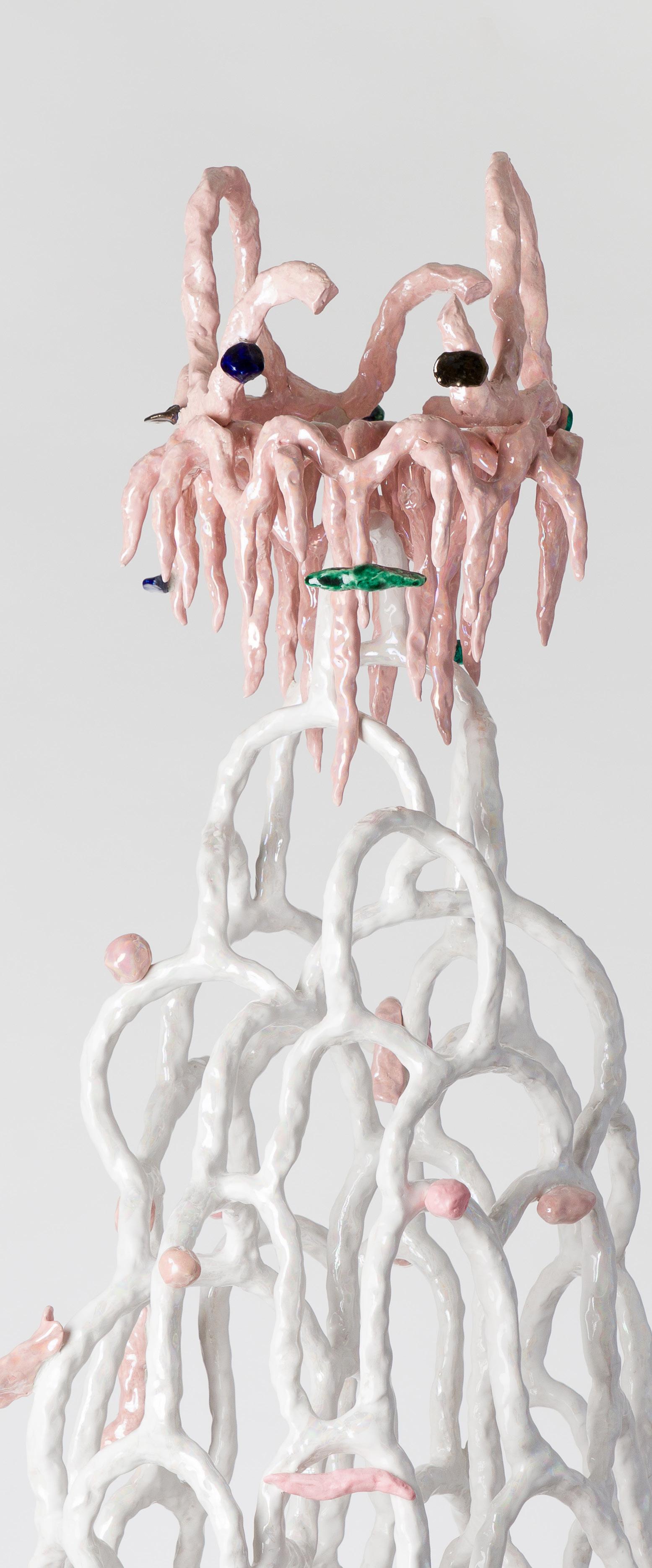

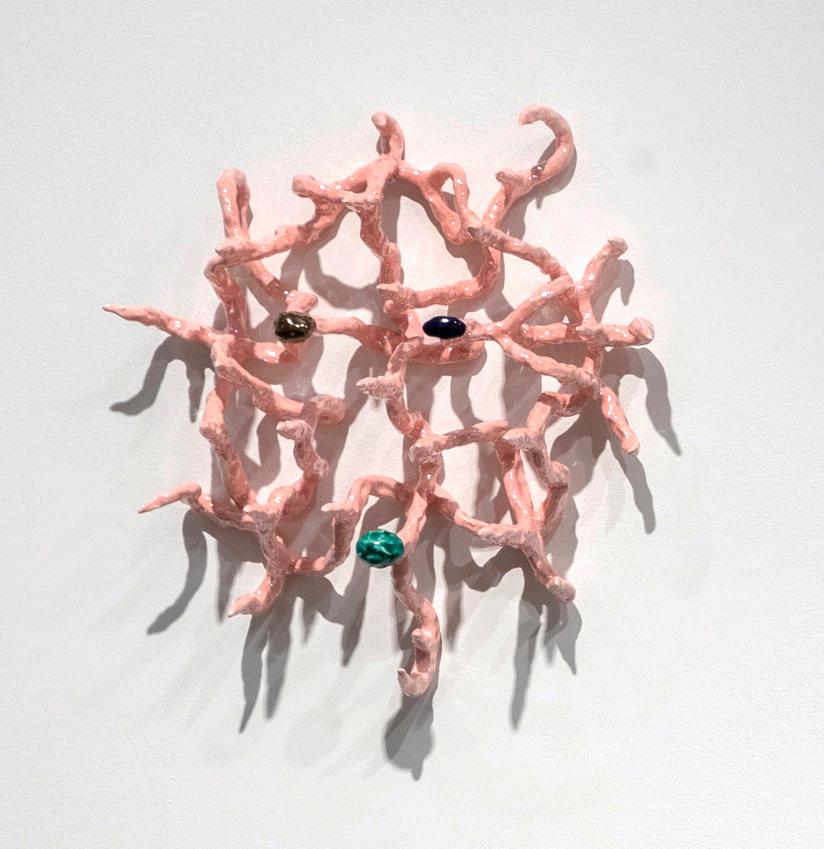

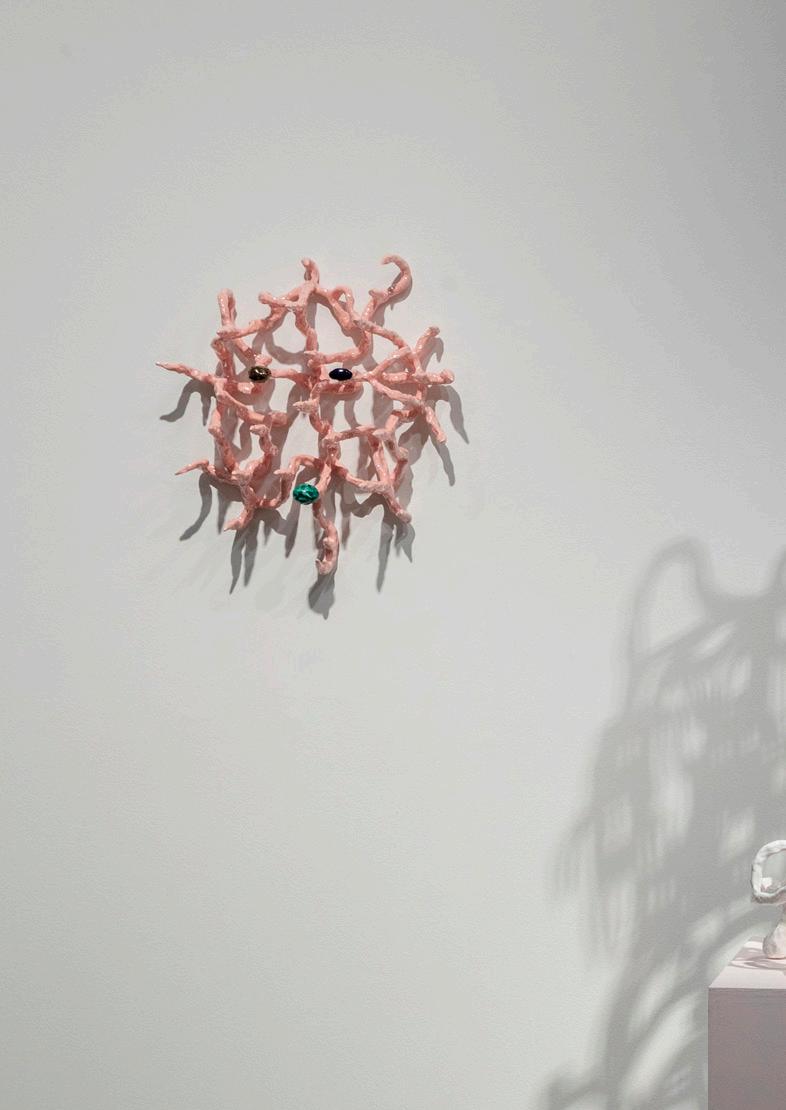

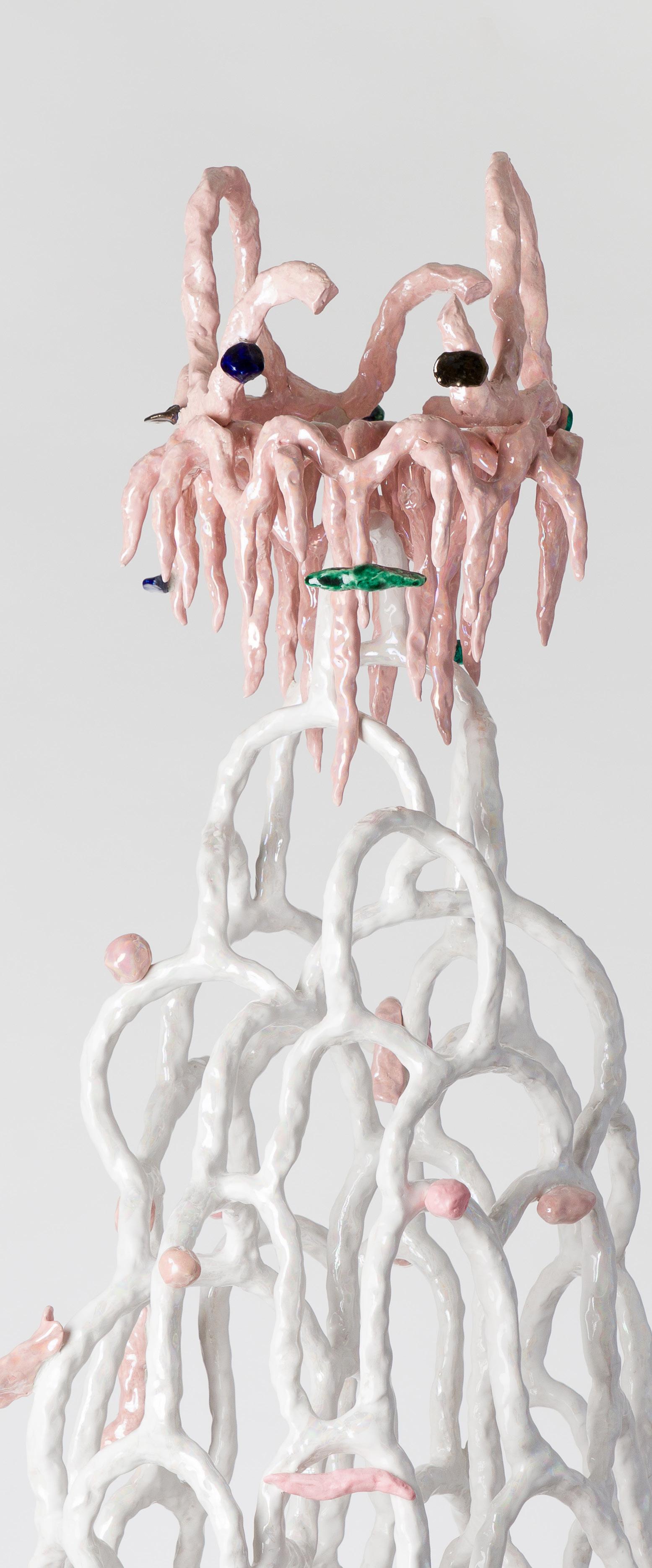

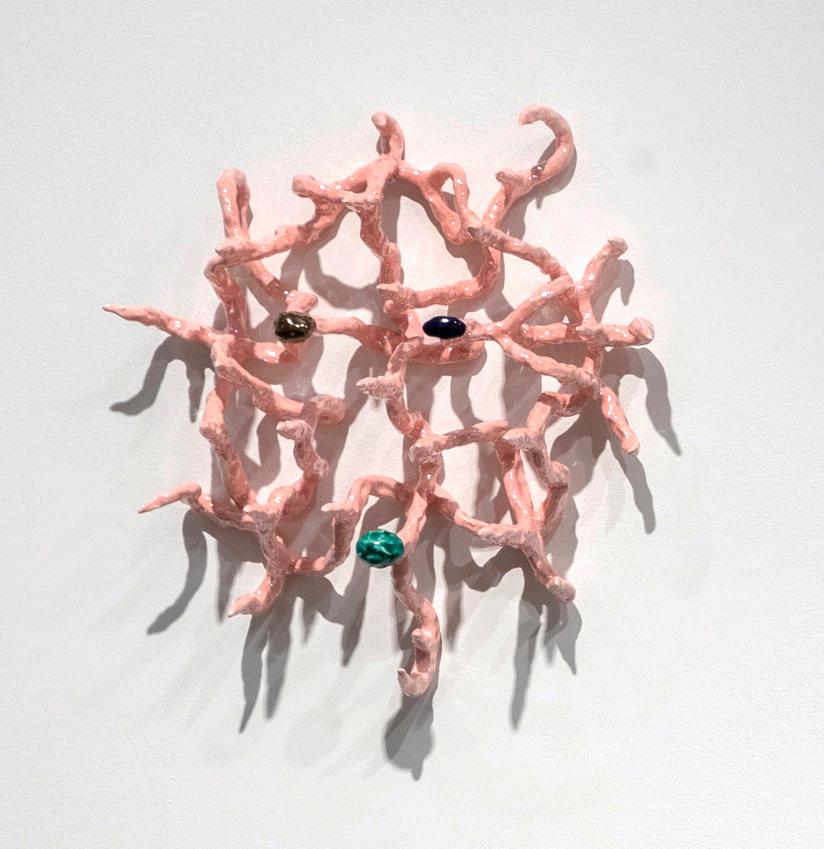

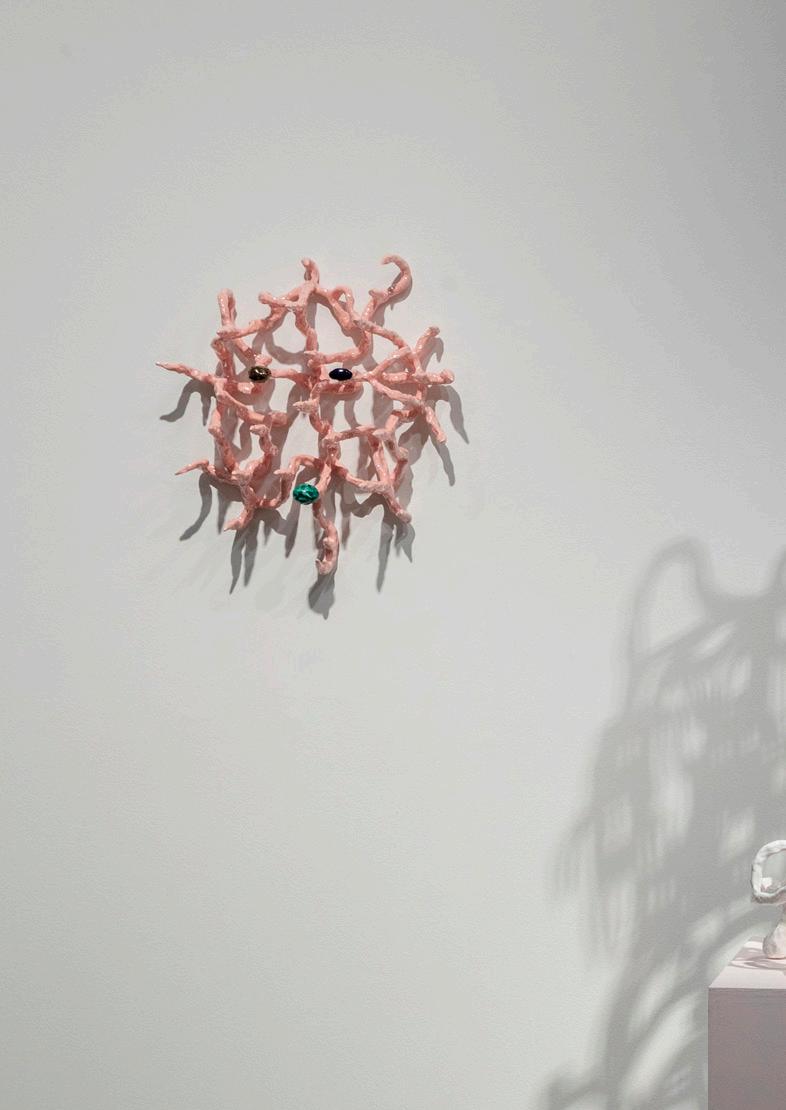

The imaginative possibilities of ceramics is also explored through Lynda Draper’s Dracaena (2021) and Dracaena II (2023), whose spindly white tendrils and fleshy pink protuberances appear like portraits of the nervous system. Draper uses clay to draw in space, and these net-like forms bridge the gap between the mental and material worlds, with their hardened clay surfaces betraying their soft, handformed origins. Emerging out of experiences of the uncanny, like that of returning to her childhood home, Draper’s sculptures explore the space between remembering and forgetting. Punctuated with black and green blob-features, they are semi-beings which are not quite here nor there, hovering above a plinth or emerging from the wall like paranormal presences.

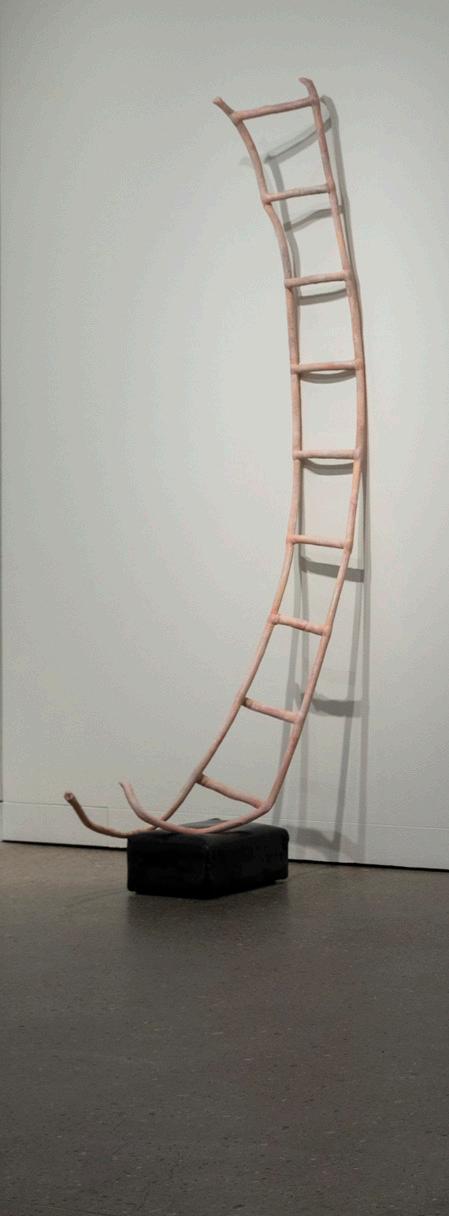

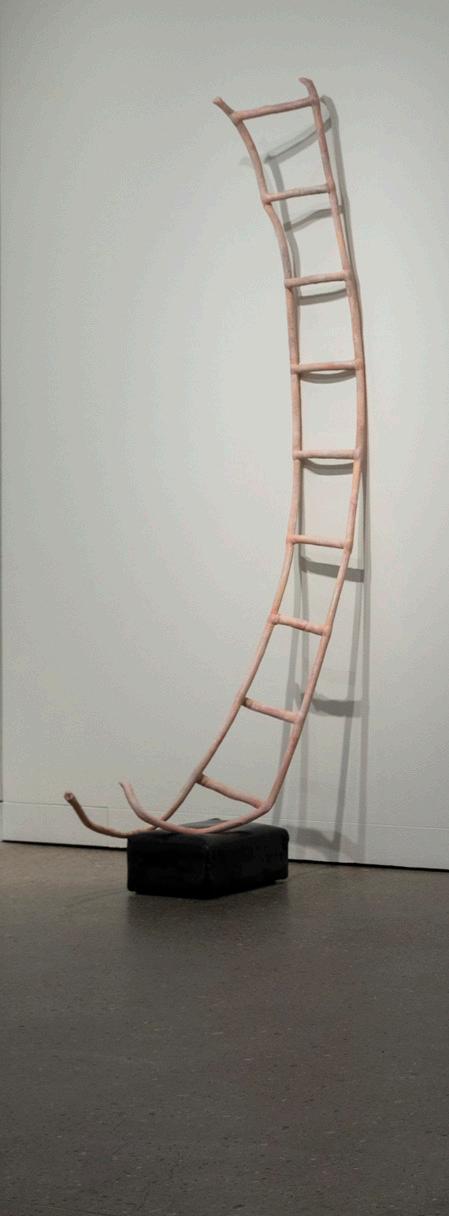

Like Draper’s works, Caroline Rothwell’s sculptures such as the fleshy-pink toned, bony trellis Ladder (2022), invite the viewer to bridge the space between the body and broader systems with their form, gesture and scale. The surface of Rothwell’s sculptures Sylvan body (silver) and Sylvan body (copper) (both 2023) have the texture of canvas and a fabric-like seam, and are formed by soft pillowy

bulges. However they stand upright and firm, possessing stiff metallic surfaces. Rothwell is intrigued by the systems which underpin our lives, and these sculptures excavate the hidden. They allude not only to skeletal, respiratory and reproductive systems, but also to botanical forms, and to the built infrastructure which snakes around, above and below us.

Madeleine Kelly’s dreamlike paintings also invite the viewer into a slippery zone between nature and culture, where organic elements are rendered with mathematical precision. In Mnemosyne (2018-23) (named for the Ancient Greek goddess of memory), an image of a person measuring a shell, discovered in an old National Geographic magazine, forms the basis for a composition exploring the human desire to uncover the information encoded within our inner and outer worlds. The spiralling form of the shell both draws inward and opens up; in Earth Drill (2023) the titular device simultaneously burrows down and exposes, encircled by birds with forked tongues. Kelly’s chosen palette of soft greens and shell pinks creates an atmospheric space for cosmic contemplation.

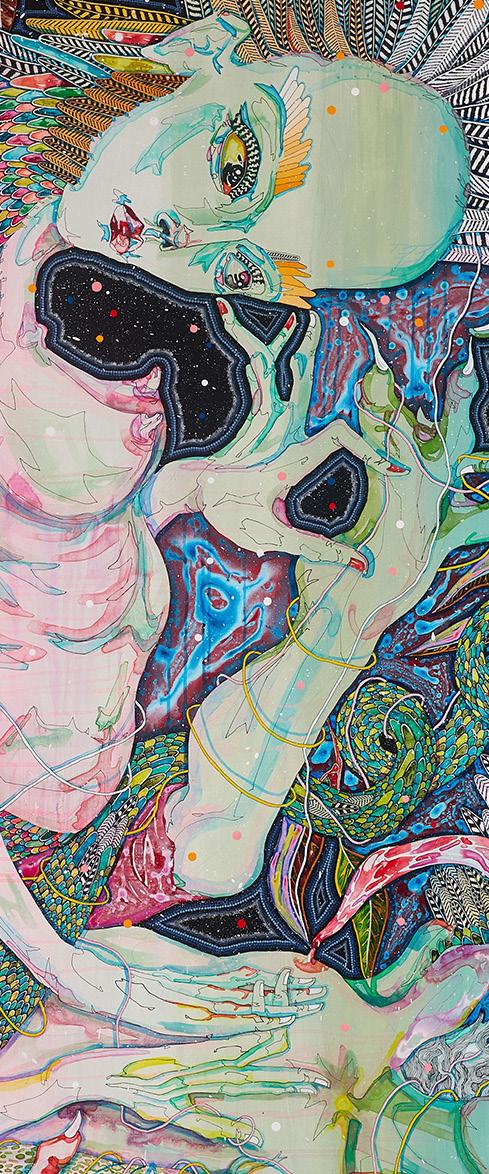

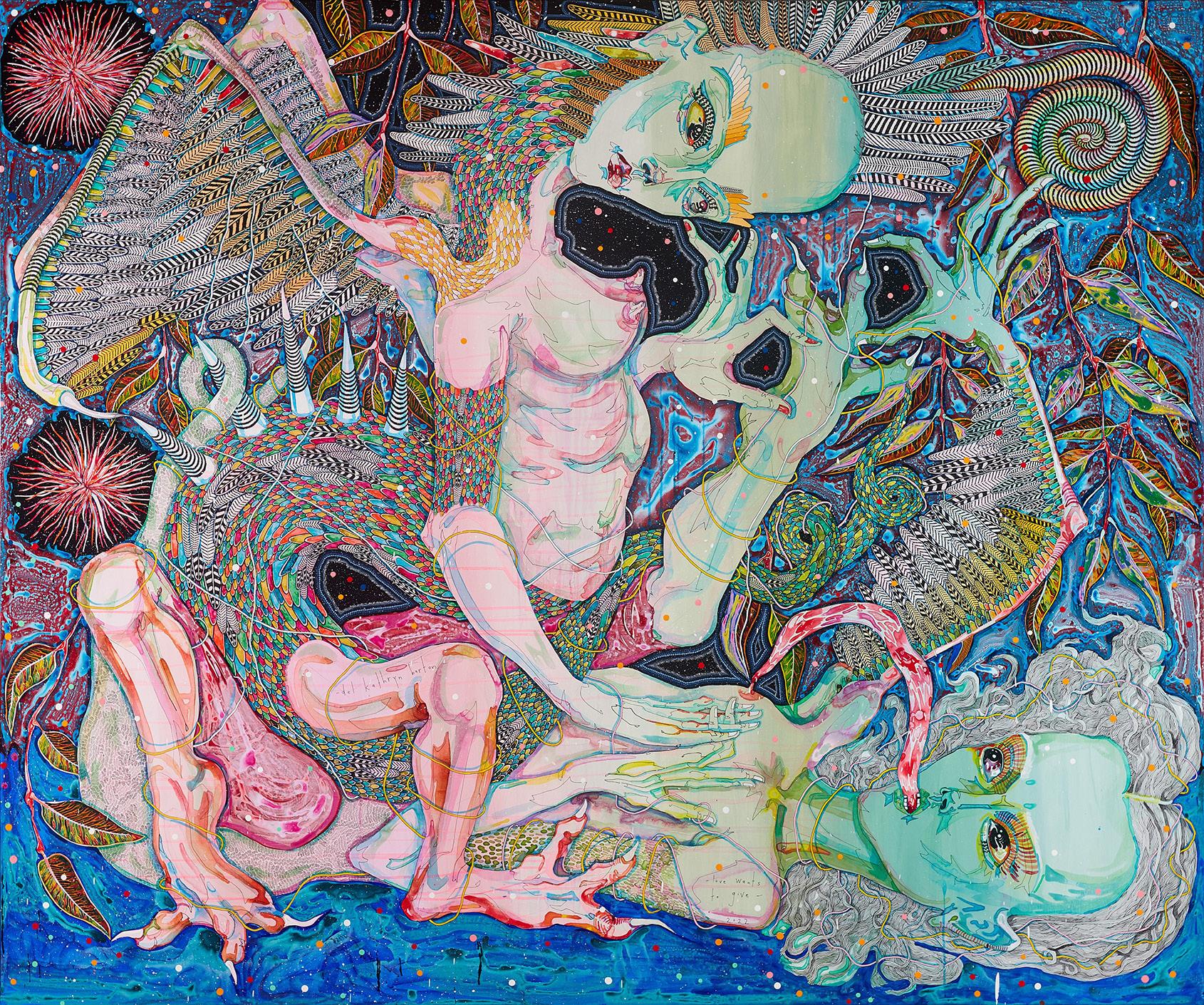

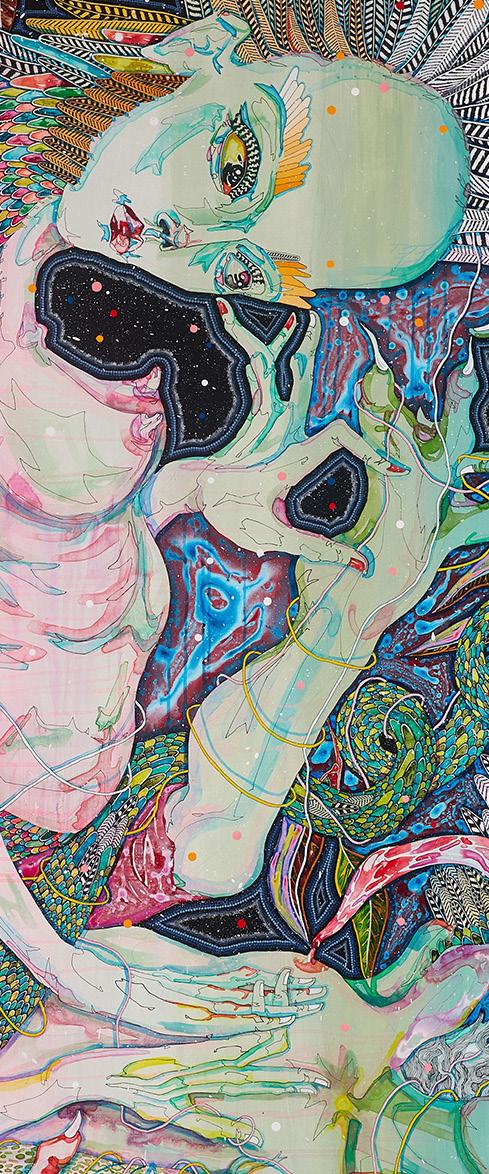

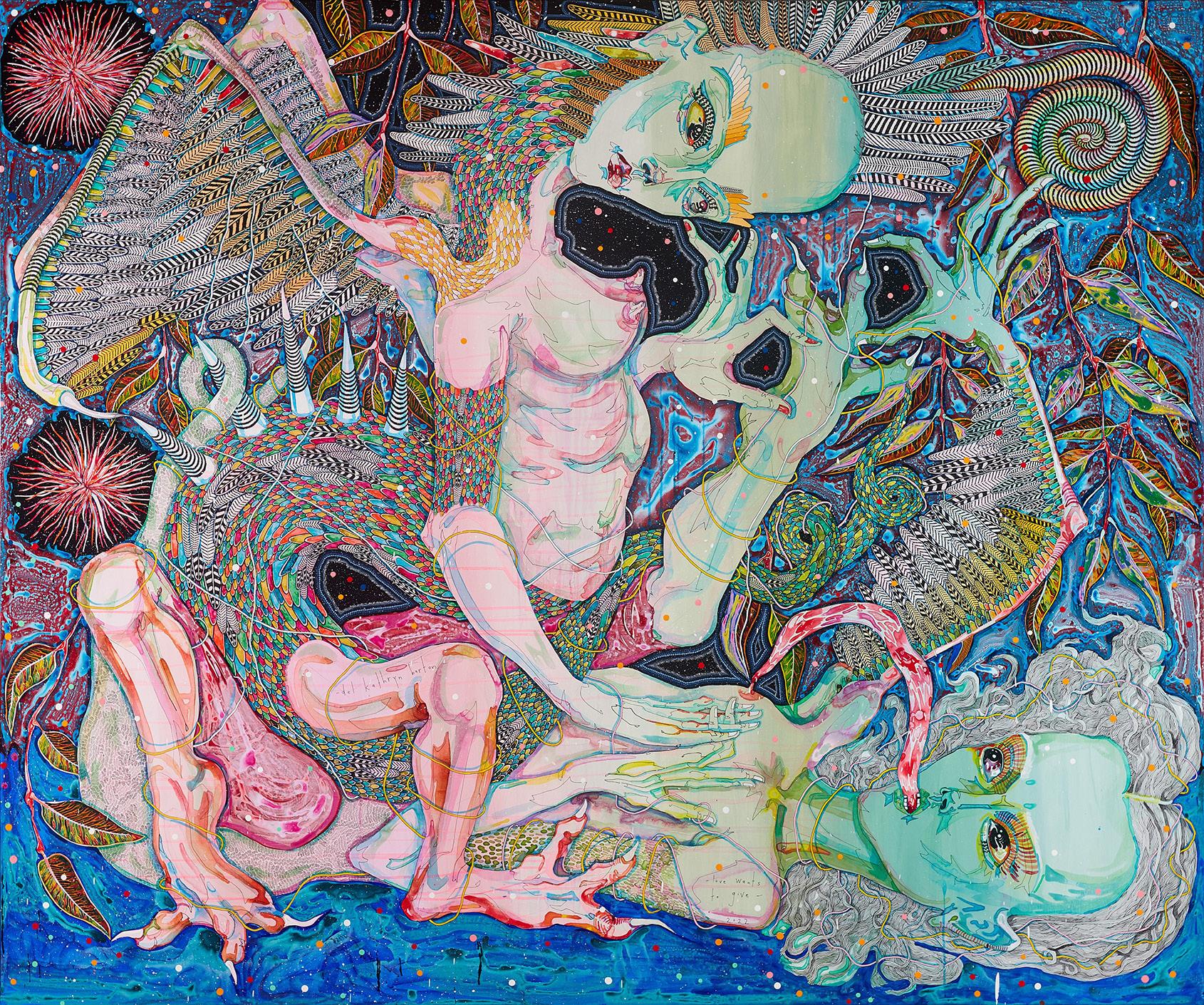

Del Kathryn Barton’s painting, love wants to give (2022) is another painterly cosmic world, featuring a fantastical exchange between two people. This iridescent, maximalist composition can barely contain the animalistic tendencies of its protagonists. Limbs intertwine;

20

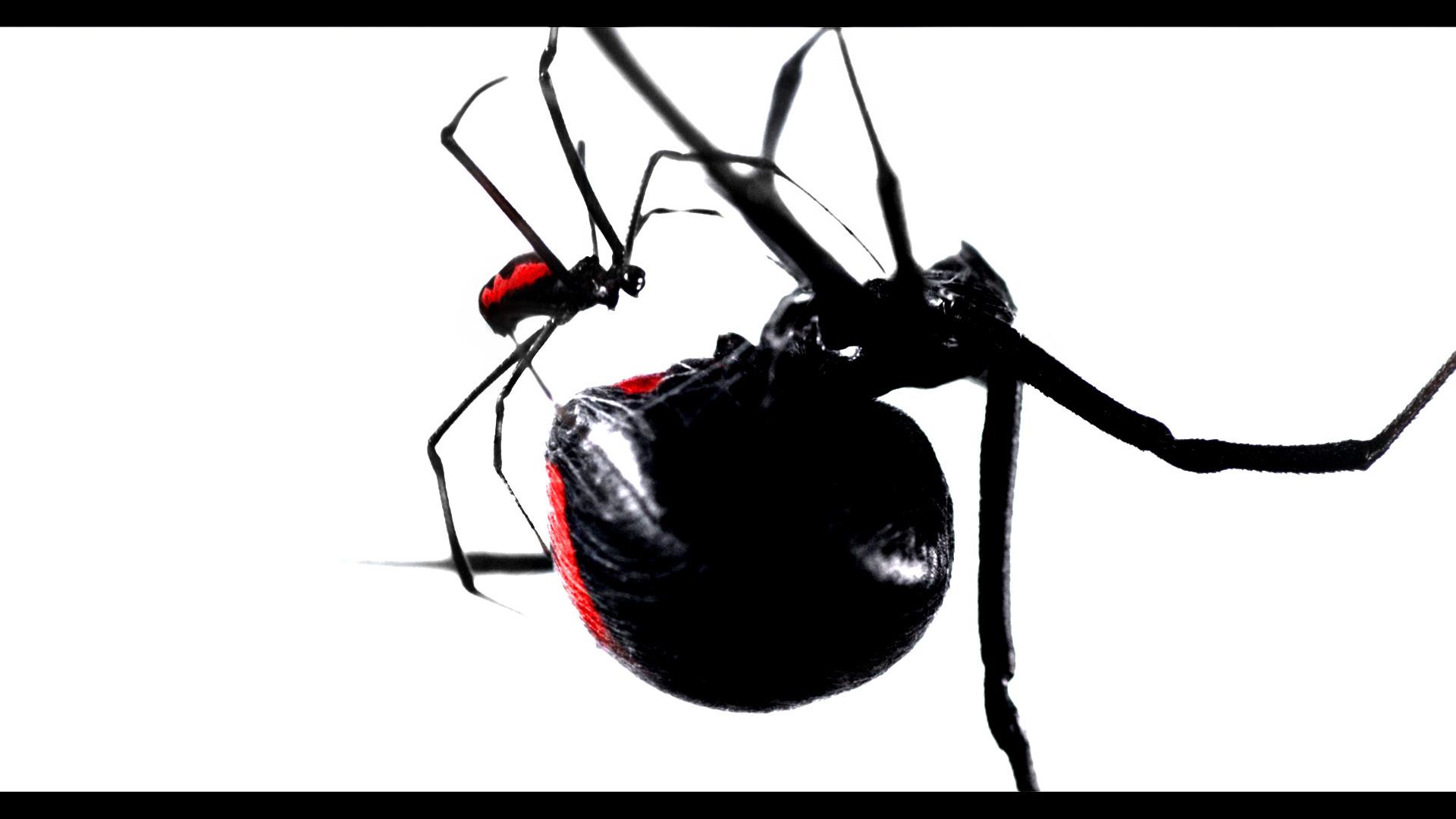

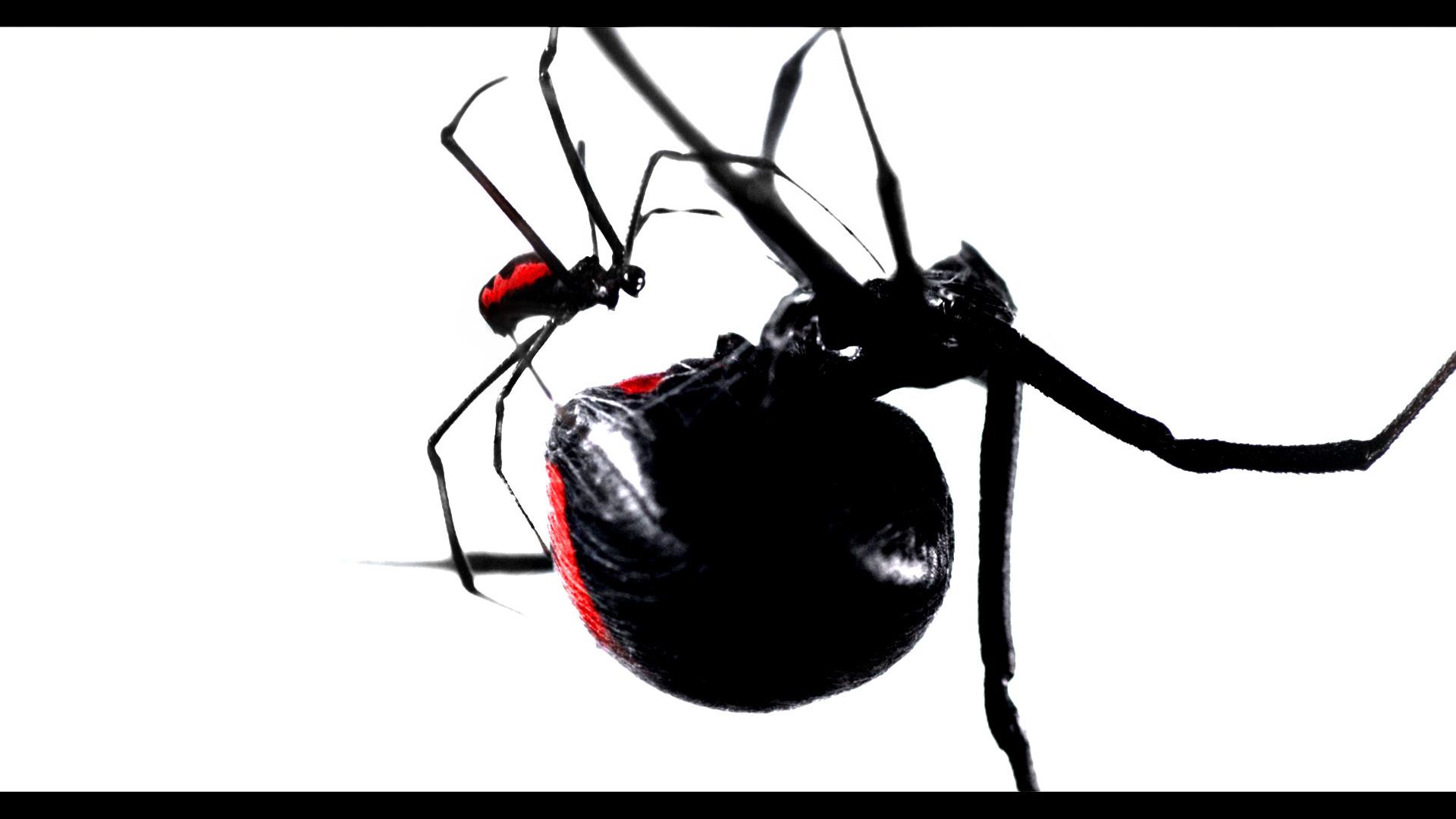

fingers and tongue sprawl tendrillike. Barton’s works are strident in their celebration of female and maternal power, and contain aesthetic universes whose legacy lies in the paintings of Surrealist women artists including Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo. The artist’s film Red (2017) explores the reproductive life of the female Australian Redback spider, one of only two known creatures where the male has been found to actively assist the female in sexual cannibalism. This encounter has been reimagined as a punk-goth feminist tableau which explodes the lines between animal, human and machine.

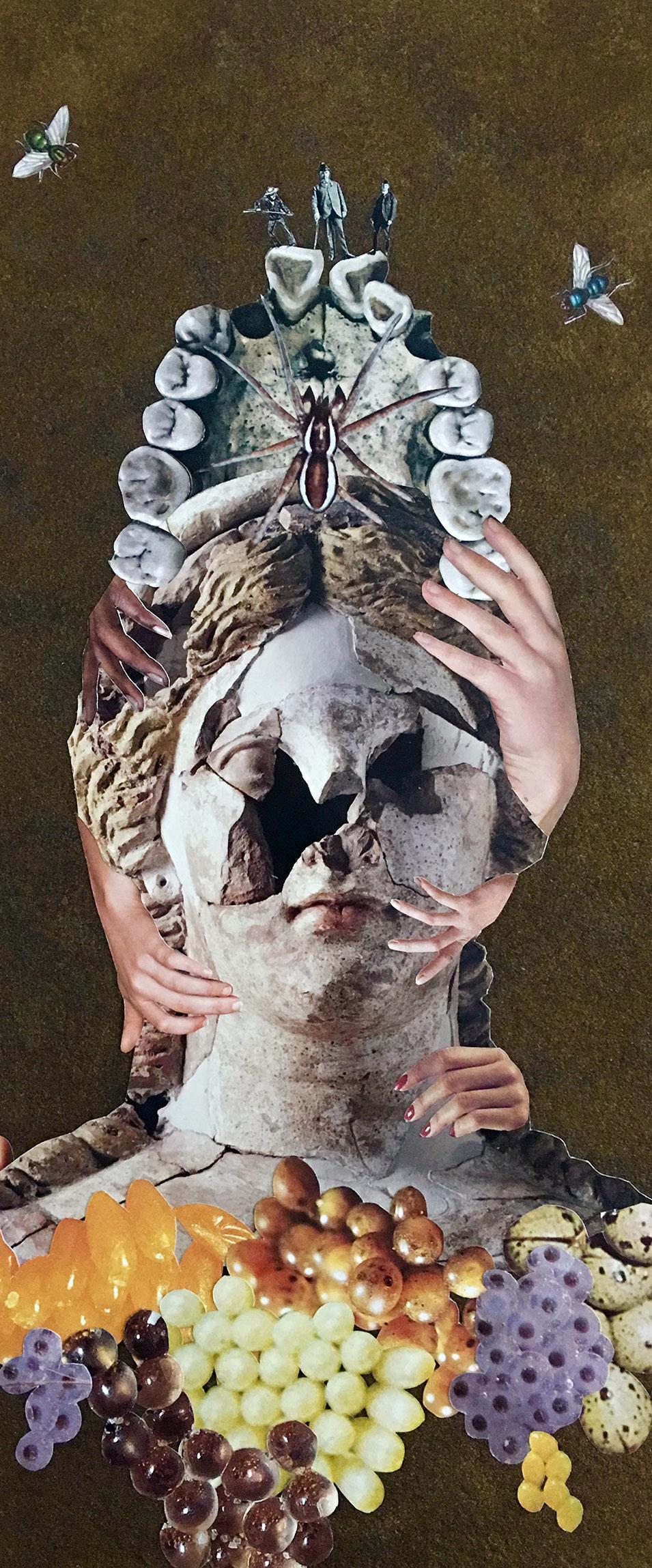

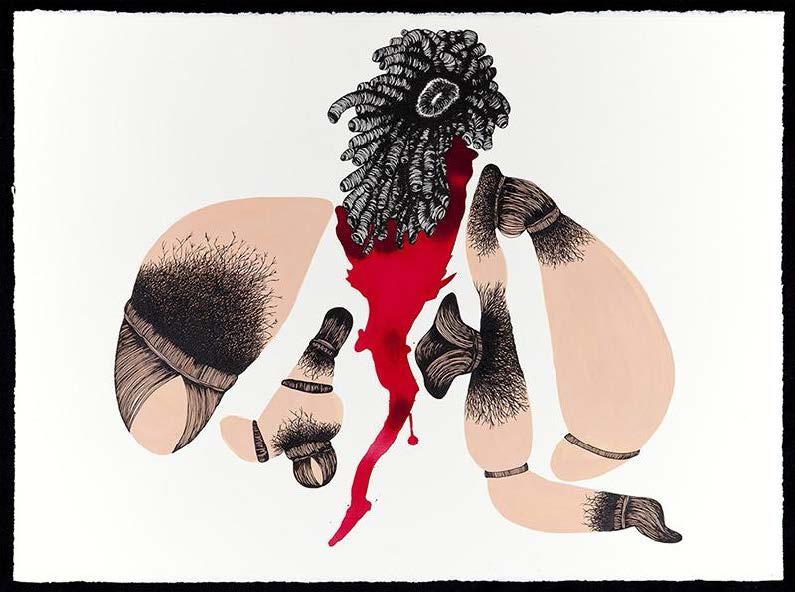

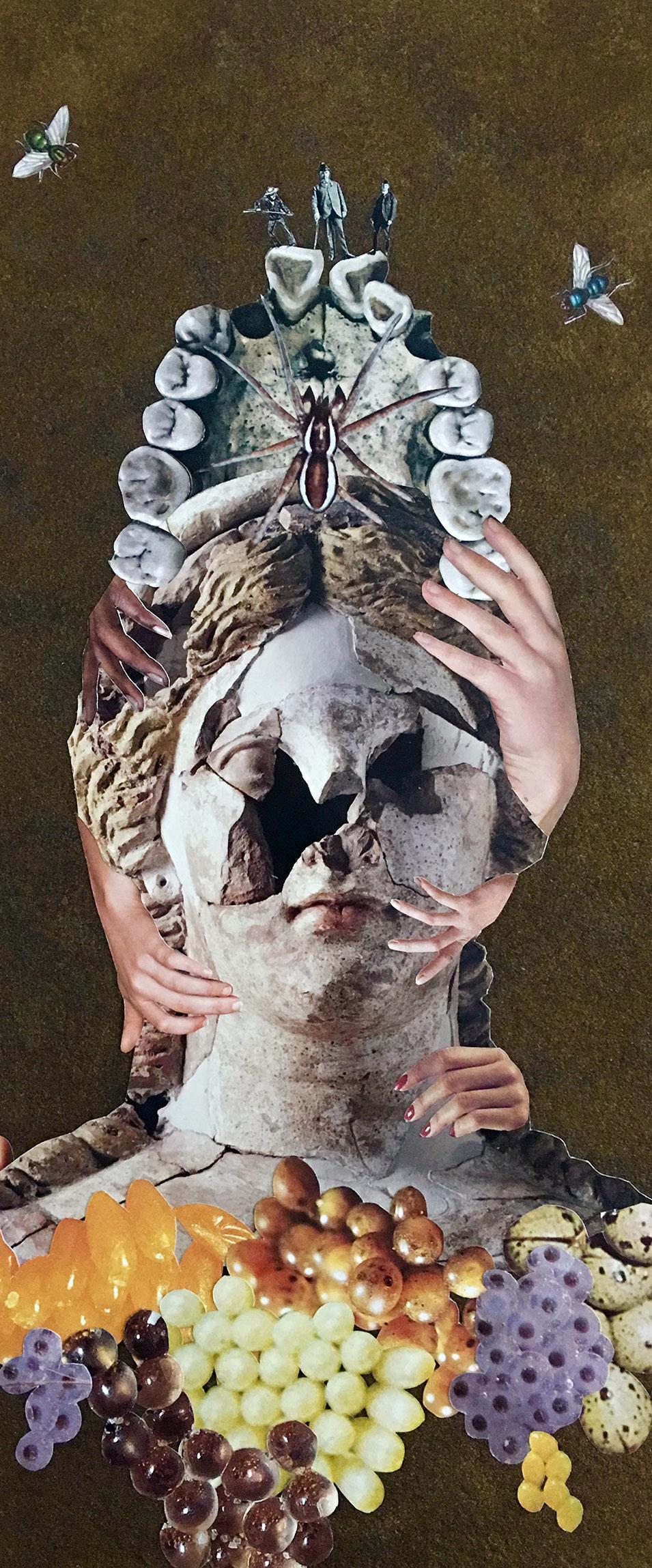

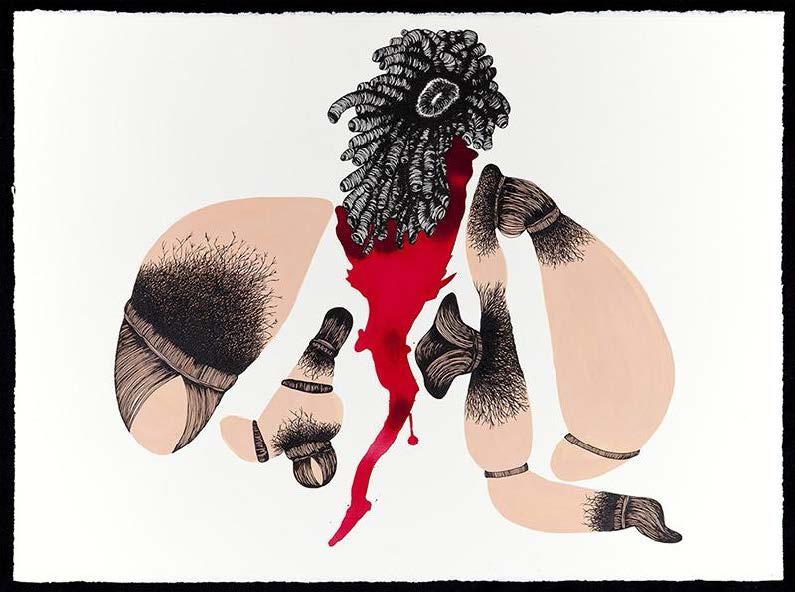

The Surrealist party game of the exquisite corpse, in which parts of figures are drawn on folded paper leaving traces of outline for others to continue, has an enduring influence which can be seen in the representation of figures across the exhibition. Another artist working in the spirit of this methodology is Deborah Kelly, whose collages, such as Death Cult (2017), Birth of Beeness (2017) and Waspwaist (2016-2017), are created in defiance of female bodily mythologies. Works such as these form the basis for the experimental collaborative animation The Gods of Tiny Things (2019). In an immersive environment in which music and mirrored imagery surround the viewer, Kelly’s hybrid figures dance in the face of existential threats.

Back at the dentists, he is insisting on an x-ray. On our previous visit six months ago, I was heavily pregnant with my younger child so x-rays were out of the question then. Today, my older child is led from the room; a hard yellow plastic rectangle is crammed inside my fleshy pink cheeks. Black and white images of the inside of my head appear on a monitor above. Exposed to their roots the teeth now loom large; disembodied, cartoonish grey shapes floating against black gums. My tongue traces their forms inside my mouth, skimming the place where hard enamel meets soft skin. The body dismembered; the body remembered.

1 Bedtime Story was written for Madonna by Björk, Nellee Hooper and Marius De Vries

2 Breton, A. Manifesto of Surrealism, in Danchev, A. (Ed) ‘100 Artists’ Manifestos From the Futurists to the Stuckists’, Penguin Classics, London, 2011, p.247

22

***

above: Del Kathryn Barton RED 2017 (still)

previous page: Madeleine Kelly Mnemosyne 2018-2023 (detail)

23

A place of multiple feminisms

KATHLEEN LINN

“The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left peers into the microscope.” 1 - Leonora Carrington

Mixing red with white creates the colour pink. We don’t call this colour pale red as we call the result of mixing blue with white pale blue. Pink gets its own name. 2 Pink is a colour that can trigger strong reactions, perhaps more than any other colour. Pink has come to represent and rally parts of the feminist movement, and the LGBTQ+ rights and pride movements. The colour pink is rightly and wonderfully ubiquitous in the exhibition In the arms of unconsciousness: Women, feminism and the surreal

During the years 2016-2017 feminism was propelled back into mainstream consciousness in a powerful way. An important and highly visible moment was the Women’s March held on 21 January 2017 to protest the inauguration of President Donald J. Trump in the United States, and his egregious sexism and misogyny. A memorable feature of these marches was the pink pussyhat, a brimless hat with two points at the top to look like cat ears. The hat’s name intended to reclaim the word pussy, taken from Donald J. Trump’s own vulgar

comments about women. 3 This wasn’t the first instance of the colour pink— at times labelled a weak colour, a feminine colour, or the embodiment of kitsch—being entwined with feminism, that connection dates to the 1960s and 1970s.

In another act of reclamation, the queer community has severed the pink triangle from a past where it was affixed to the uniform of prisoners labelled to be homosexual in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. The triangle and the colour have been recast to express pride, strength and identity. The colour pink is also intimately connected to the aesthetics of Camp.

Attempts to conceptualise the history of feminism reveal multiple and varying opinions. There is disagreement about the current wave metaphor (now up to the fourth) and whether this is constructive beyond the first and second waves that are clearly definable. 4 The history of feminism is “a history of differing ideas in wild conflict,” 5 and this holds true today; however, there

26

are several facets of contemporary feminism that warrant mentioning here. These are the importance of intersectionality, 6 the inclusion of trans women, the use of online organising as a primary tool and body positivity. 7

A significant example of online organising is the #MeToo movement that erupted on social media in 2017. The phrase ‘me too’ was first used by social activist and community organiser Tarana Burke in 2006. The #MeToo movement started as a call to action by actor Alyssa Milano, she encouraged all women who had experienced sexual abuse or harassment to post ‘me too’ as a status to show the enormity of this atrocious yet ingrained behaviour.

Within days millions of women (and some men) around the world posted on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram, sharing their stories.

I will chart a little more of the colour pink’s importance to contemporary culture. Pink has been loved and hated by parents and young children across the globe as, along with blue, it is frequently used to draw the lines of the gender binary in childhood and to re-affirm this binary in our society. But pink is also the persistent ‘millennial’ pink (Rose Quartz was Pantone’s colour of the year in 2016) and as such pink has become a force in recent years to express not only feminism or sexuality, but also and importantly, this moment in the early twenty-first century.

27

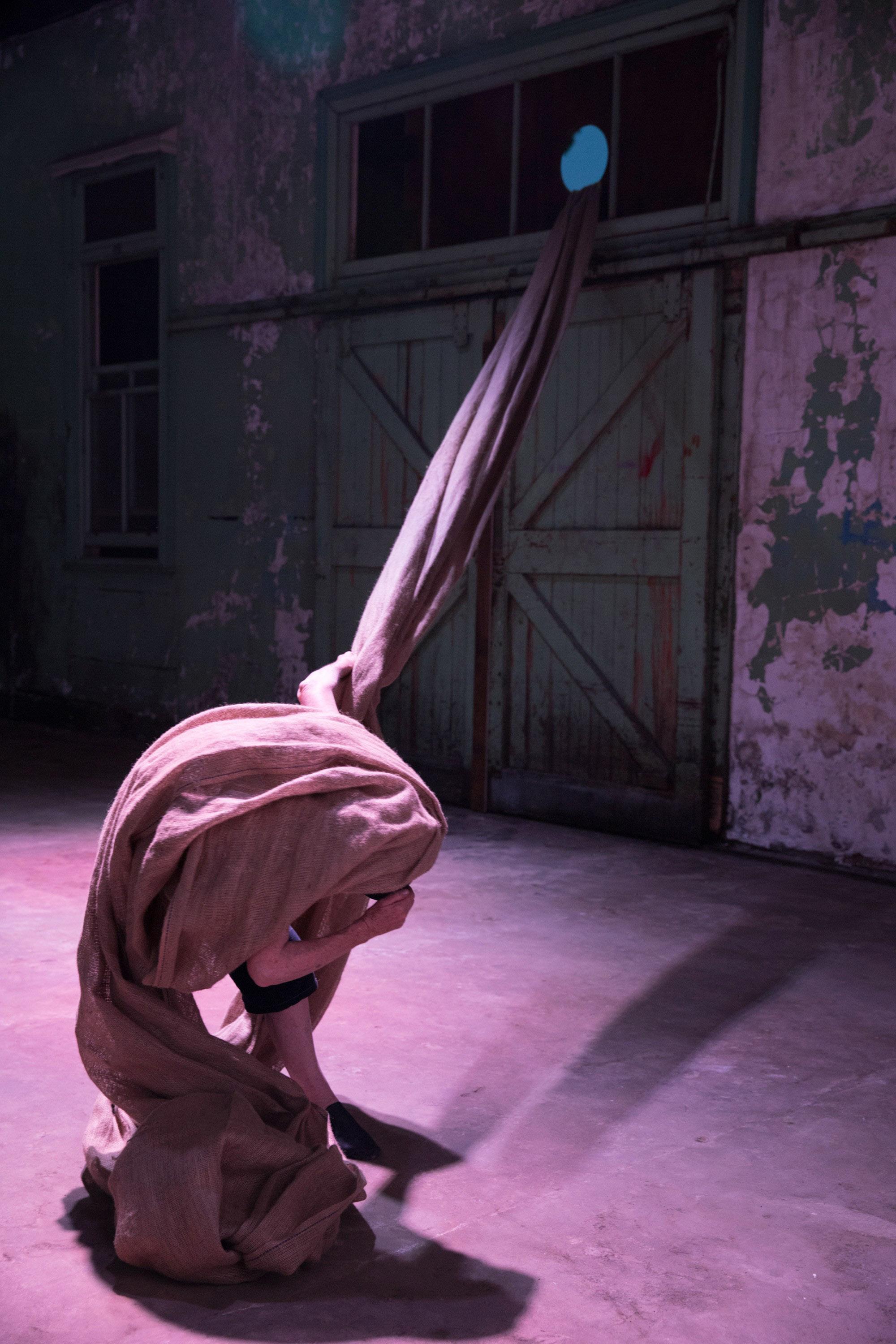

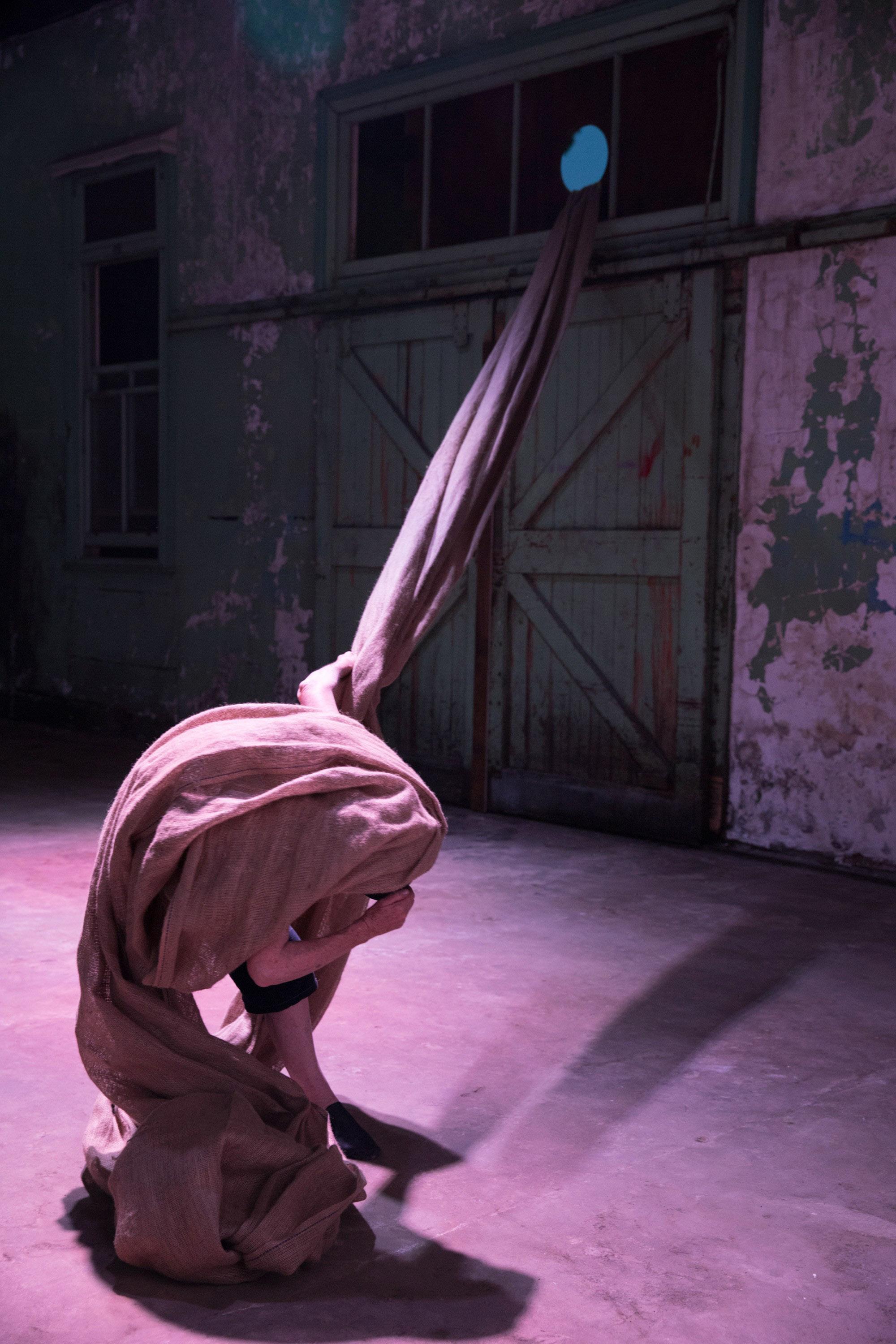

The use of pink by the artists Honey Long & Prue Stent, Lucy O’Doherty and others in In the arms of unconsciousness taps into the multifaceted meaning and history of the colour. Honey Long & Prue Stent’s three large-scale photographic works were created through performative encounters between a figure, often a naked woman (frequently the artists themselves) and the natural environment, here the Australian landscape. The artists use pink fabrics to screen or cover parts of the body, abstracting the body’s shape into sculptural, hybrid forms. In Long & Stent’s work these bodies are not part of the scenery, they are not there simply for the viewer’s pleasure. Their figures, while quoting art historical tropes, stand in contrast to classical, essentialist depictions of the female form in the natural environment. These works explore dreamy, fluid forms, the environment and transformation.

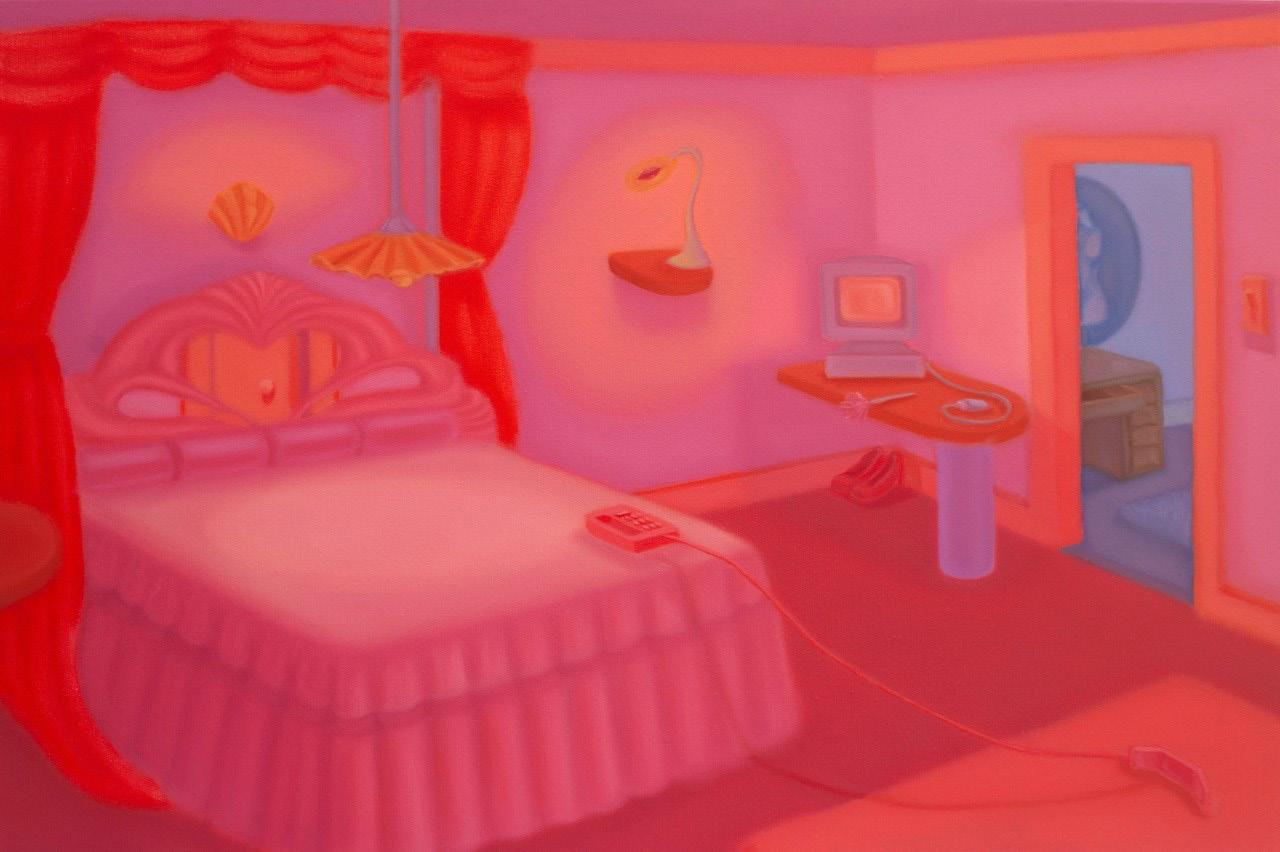

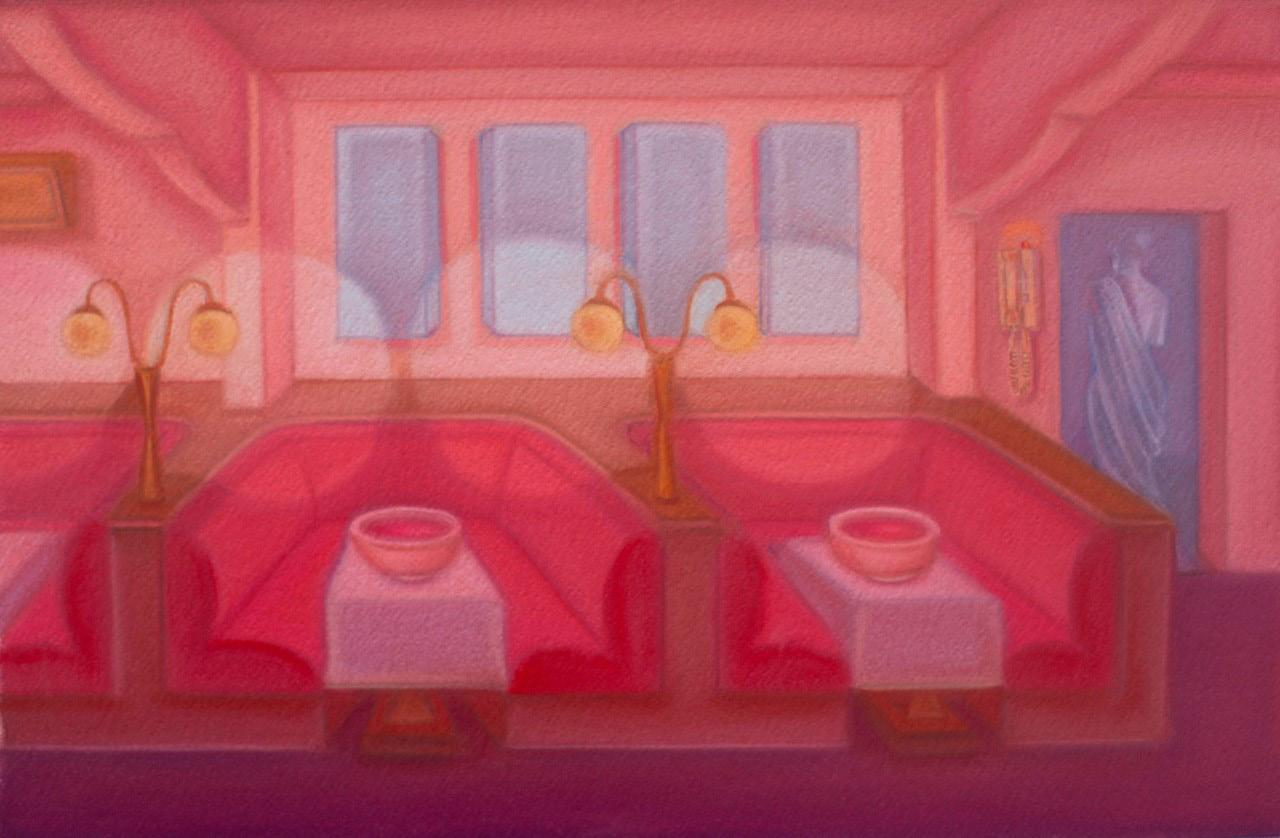

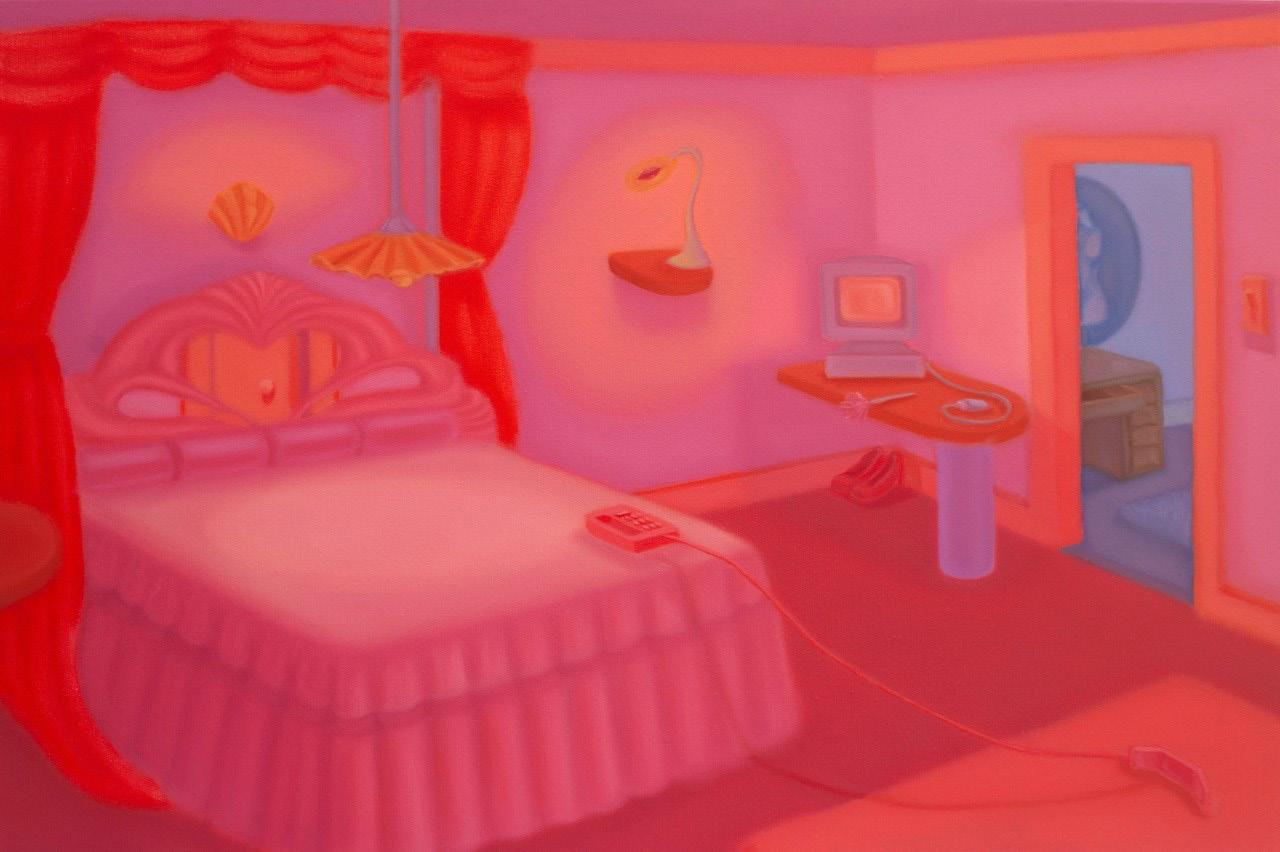

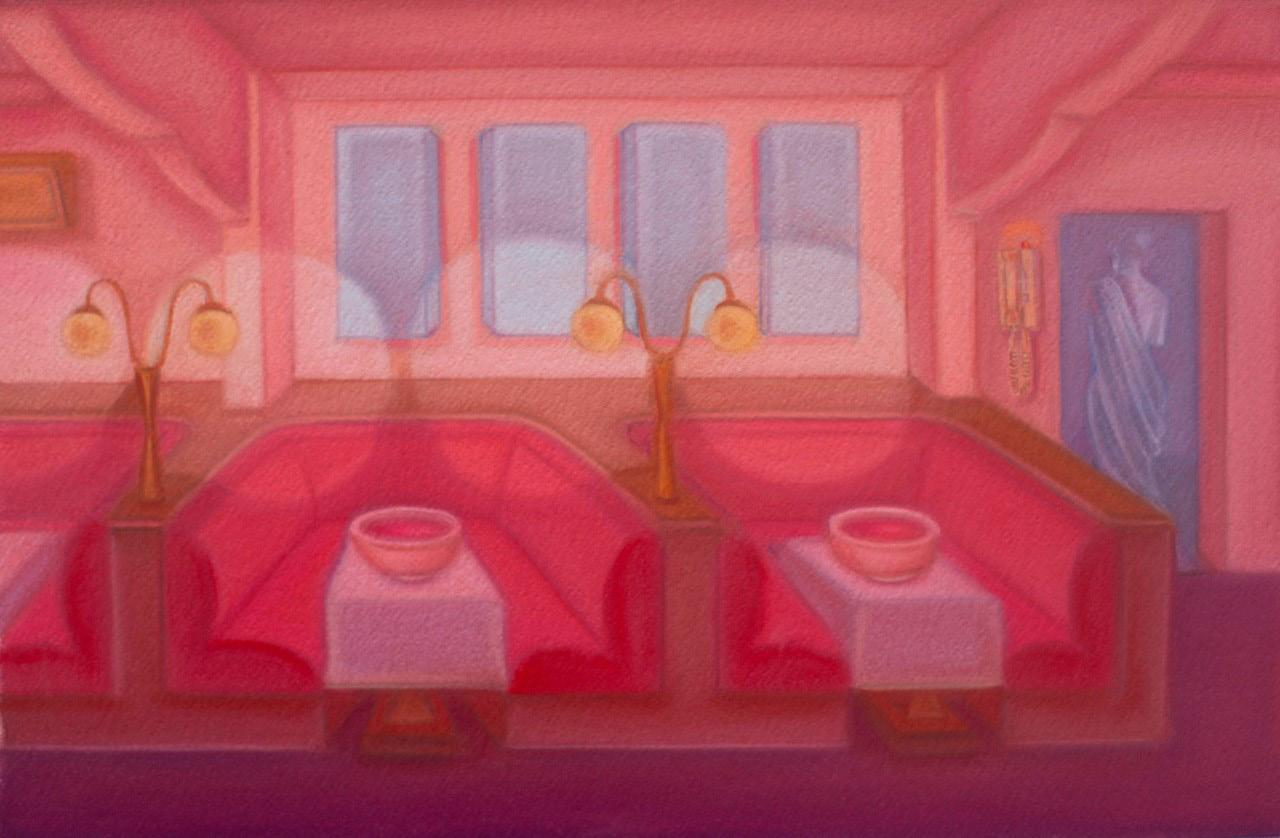

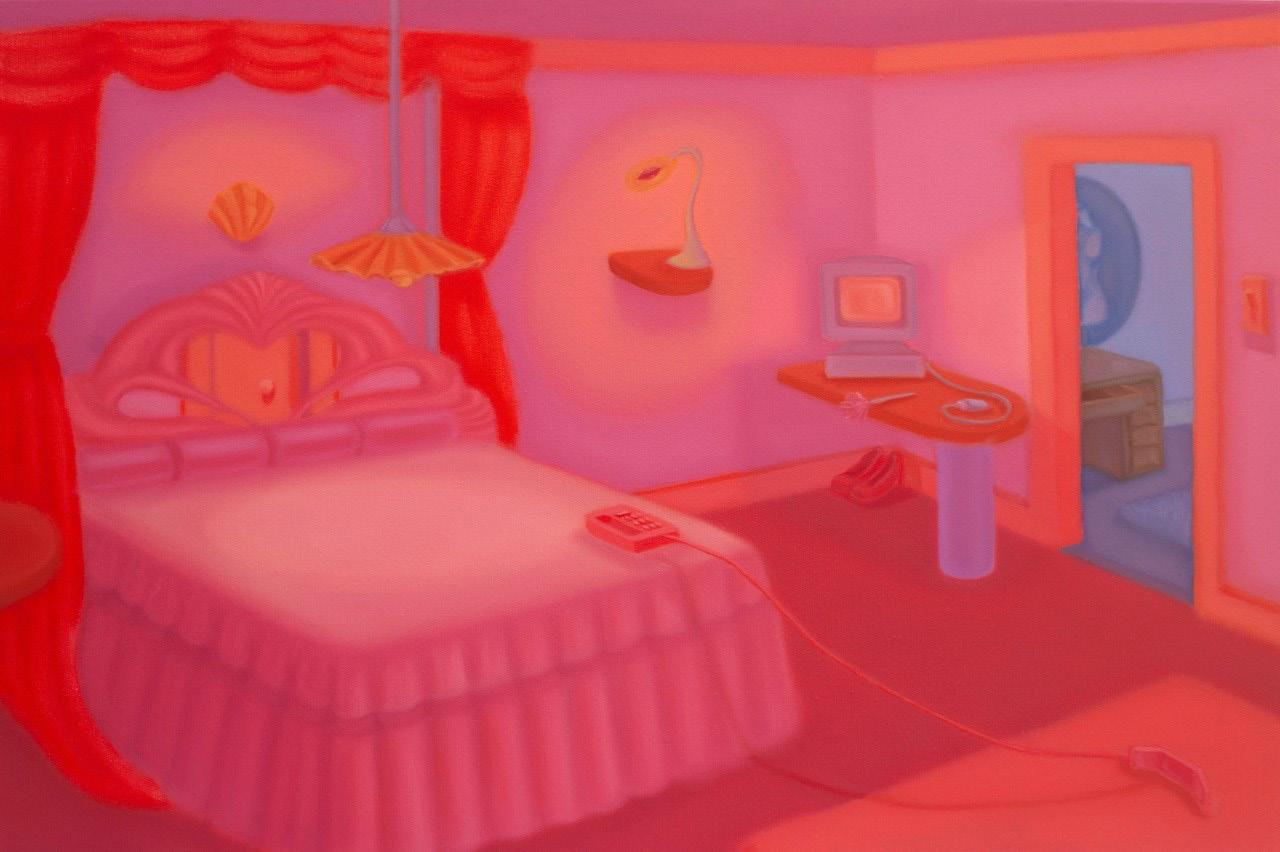

Lucy O’Doherty’s suite of paintings portrays booths at a café, a swimming pool and the intimate environment of a bedroom but are devoid of people, entirely. They seem to tap into the same unsettling, psychologically charged space that Edward Hopper inhabits with his emotionally dense works. But unlike Hopper, O’Doherty’s work is rendered in decadent pinks

which layer a further fantastical, contemporary quality onto the work.

The surreal, although derived from Surrealism, encompasses a broader scope than the initial movement in the 1920s. Not only is it a melding of the oneiric or dream world, our unconscious mind and reality, but the surreal can flip our usual way of thinking allowing for the possibilities of metamorphosis, hybridity and plasticity of bodies and forms. These are fertile areas of research and thought, explored by contemporary artists concerned with the impending climate crisis, gender and sexuality. Elements of the surreal also weave into fantasy and science fiction within contemporary culture.

Juz Kitson’s delicate hand-built and slip cast porcelain and clay works are intricate and finely detailed. They operate on a granular or micro level, but taken as a whole, the work’s large size and other-worldly qualities allow it to zoom out, to become macro in its investigation of nature’s cycles of metamorphoses, transformation, decay, beauty and abundance. The work shown here, Observe the many ways, liminal spaces bordering things we already know. In memory of the wildfires. (2021-2022), respond to the bushfires of 2019 that devastated the areas around Kitson’s studio on the

previous page:

Lucy O’Doherty

Think Pynk 2023

opposite:

Juz Kitson

Observe the many ways, liminal spaces bordering things we already know. In memory of the wildfires. (2021-2022)

28

south coast of Australia.

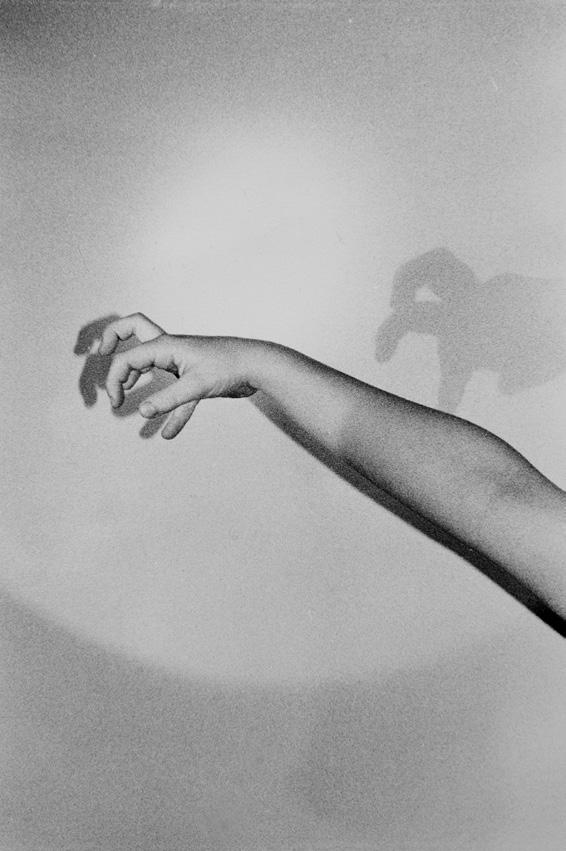

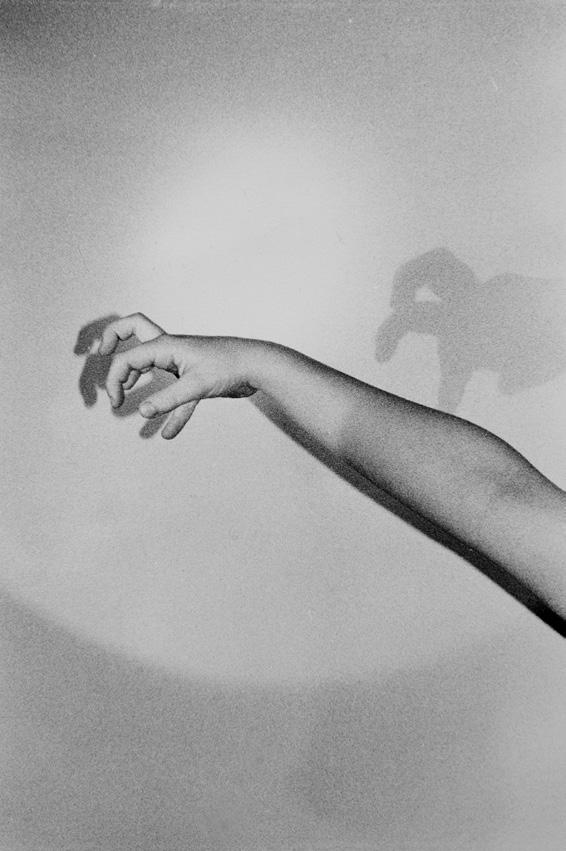

Amanda Williams’ series of photographs Or your shadow rising to meet you (2020-2023) include four images of Williams’ daughter— just her arm, held out, her hand making shapes. Each photograph captures shadow-play on the wall behind: one a spider, another the beak of a swan. This is accompanied by four photograms depicting the eery warp and weft of a single piece of material. This series invites the viewer into the private space of Williams’ home during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown, a time she spent with her daughter. Williams’ practice more broadly seeks to destabilise the history of analogue photography and photographic processes through experimentation—this includes using exhausted developing chemicals, not ‘fixing’ images, or bleaching or solarising with extra light.

Kaylene Whiskey’s single-channel video work Ngura Pukulpa – Happy Place (2022) features a group of Aboriginal women travelling through the APY Lands 8 in a four-wheel drive while hand-painted images of Wonder Woman, flowers, the ‘Holy Book’ and boomerangs dance across the screen. This is accompanied by a humorous soundtrack of Whiskey’s joyful voice repeating her own name. Whiskey’s large-scale paintings combine her love for popular culture icons like Dolly Parton and Wonder Woman—women Whiskey refers to as kunga kunpa or strong women— with flowers, snakes, birds, guitars

and the beautiful landscape of her Anangu home rendered in traditional dot iconography and a contemporary style.

Pop culture and Catholicism inform the work Renaissance (2018/2023) by Marikit Santiago. Santiago’s self-portrait references Beyonce’s pregnancy announcement of 2017. Beyonce was photographed with a blue veil alluding to the Madonna and child, her pose said to echo Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c.1485). Santiago’s self-portrait, while at once highly realistic holds fantastic or surreal elements. Her head seems too large for her body, while her body joins with and separates from the unmistakeable outline of the Virgin Mary in her traditional pose (where she is veiled with her arms held out to her sides). Santiago is the mother of three young children who feature in her paintings, both as subjects and as assistants, sometimes contributing their own marks to her work. By working with her children in this way, Santiago challenges the persistent idea in the history of painting that the painter is a lone, inspired (male) genius.

Through her precise and minimal figurative painting style and restrained brushwork, Jelena Telecki explores the dynamics of power and control in different contexts. The painting Suit (2023) commissioned specifically for In the arms of unconsciousness, features a shiny, emerald-green rendering of the jacket from a 1980s women’s

30

power suit. Through its comical, disproportionately large shoulder pads, Telecki considers the garment’s role in signalling and (quite literally) shaping women into new and more dominant roles at work.

Leading Surrealist figure Leonora Carrington’s book Down Below details her experience of a psychotic break and subsequent mis/treatment at an institution in Madrid in the 1940s. In Marina Warner’s introduction to the book, she talks about the expectations placed upon a very young Carrington by her much older lover Max Ernst. Not only was Carrington expected to be the femme-enfant (child-woman) medium summoned from the Surrealist dream-world, she was expected to be a subservient young woman who cooked for and entertained Ernst’s revolving circle of guests. 9 In the painting Rude (2021) Telecki questions the expectation placed upon her by her Serbian family, specifically that women should hide their grey hairs— and the aging process in general— always being disciplined and ‘well presented’ in their appearance.

The artworks discussed in this essay have all been created within the last eight years and speak powerfully to our present moment— one of upheaval, challenges, transformations and reformations. They show how women see themselves within (or without) our society, and our society itself. These works tantalise with the graspability of equity and societal shift, but

also remind us of the persistent expectations placed upon women and the looming environmental crisis. These artists remind us of the enduring importance of women’s lives—their thoughts, actions, friendships and families.

1 Carrington, L., 1988, Down Below, The New York Review of Books, New York, p. 19

2 I am referring to mixing the primary colours (red, blue and yellow) with white, not the secondary colours or black.

3 The New York Times, 2016, ‘Transcript: Donald Trumps taped comments about women’

4 Grady, C., 2018, ‘The waves of feminism, and why people keep fighting over them, explained’ Vox

5 ibid.

6 Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how a person’s various social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. The term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. Intersectionality is seen as part of third-wave feminism.

7 Grady, C., 2018, Op. cit.

8 Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara

Lands in South Australia

9 Carrington, L., 1988, Down Below, The New York Review of Books, New York, p. xiii

31

DEL KATHRYN BARTON

VIVIENNE BINNS

PAT BRASSINGTON

LOUISA CHIRCOP

LYNDA DRAPER

FREYA JOBBINS

DEBORAH KELLY

MADELEINE KELLY

JUZ KITSON

HONEY LONG & PRUE STENT

LUCY O’DOHERTY

JENNY ORCHARD

JILL ORR

PATRICIA PICCININI

CAROLINE ROTHWELL

JULIE RRAP

MARIKIT SANTIAGO

JELENA TELECKI

ANNE WALLACE

KAYLENE WHISKEY

AMANDA WILLIAMS

34

ARTISTS & WORKS ARTISTS & WORKS

35

DEL KATHRYN BARTON

36

38

Del Kathryn Barton’s obsessively patterned, meticulously detailed and vivid paintings explore the female experience and female sexuality interwoven with references to traditional folklore and the cosmos. The dream-like and fantastical scenes of imaginary worlds are a celebration of female power, often featuring fierce and erotic female forms combined with references to the animal world. Barton has described her work as ‘a feminist fever dream’.

In love wants to give a divine feminine love is revealed as an organic, evolving, energetic life source that permeates from the artist into the canvas and unflinchingly embodies the radical fierceness of raw existence.

left and previous page (detail): love wants to give 2022 acrylic on linen

39

del kathryn barton

40

Text/Artist Statement

RED is Del Kathryn Barton’s second film and first live action film, featuring Cate Blanchett, Alex Russel, Arella Plater and dancer Charmene Yap. It is based on the mating instincts of the redback spider in which the male offers himself as a meal to the female after mating. Barton has described the feminist film as a celebration of raw female power.

“RED is a radical reimagining of a number of creation myths. The Australian red-back spider is one of only two animals in the world where the male has been found to actively assist the female in sexual cannibalism. This jewellike mother-hunter gives life and takes life in one elemental act of creation. Radiant maternal power is celebrated in RED, in fierce and contradictory ways.”

Del Kathryn Barton

RED 2017

film, 15:00

Film Credits

Cast

MOTHER Cate Blanchett

FATHER Alex Russell

DANCER Charmene Yap

DAUGHTER Arella Plater

Written and Directed by Del Kathryn

Barton

Produced by Aquarius Films, Angie

Fielder

Creative Director Liz Ellis

Director of Photography Benjamin

Shirley ACS

Production & Costume Designer Alice

Babidge

Editor Mark Bennett

Composer Tom Schutzinger

Sound Designer Brooke Tresize

VFX Supervisor Richard Lambert

Colour Designer Andrew Clarkson

Executive Producers

Cecilia Ritchie

Polly Staniford

Arndt Art Agency

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Danielle and Daniel Besen, Besen

Collection, Melbourne

Max and Monique Burger, Burger

Collection, Hong Kong

41

del kathryn barton

RED 2017 film still

VIVIENNE BINNS

42

43

44

Viewed as anticipating the Feminist art movement, Vivienne Binns’s early career was defined by images of powerful sexual symbolism and activism. Working since the 1960s, primarily as a painter, and extensively in the area of community arts throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, her abiding interests are the function of art making as a human activity, which occurs in all social groups, and the manifestations of this throughout these communities. This is especially visible in Binns’s use of patterning and surface treatments, which connect historical art movements to domestic or familiar imagery. Her drawing practice has seen her employ the automatic drawing process used by the Dada and Surrealist artists, in which drawing is done freely and without any conscious design. This body of work first shown in 1990 are tiny drawings of God’s beard based on a range of art historical sources and given a playful feminist treatment.

“These drawings are part of a series of 44 drawings most of which are from prints in books and print media, with images of varying sizes and quality. Others are interpretations reflecting gender, contemporary art, quality and objects from various cultures called God’s beard acting as metaphors. They were meant to be understated and visually dubious at times.”

vivienne binns

45

Text/Artist Statement

ink and pen on

left and previous page (detail): Drawings of God 1990 biro, pencil,

paper

PAT BRASSINGTON

46

48

Often described as Australia’s leading surrealist photographic artist, Pat Brassington has been exhibiting for more than four decades. Her practice is informed by an interest in Surrealism, feminism and psychoanalysis and her haunting images sit in the border between the real and the unreal, the innocent and the menacing, the dream and the nightmare.

“I have long been interested in psychoanalysis and have been intrigued also by strategies used by some Surrealists. If I add these influences to my own life experience I come as close as I can to providing a rationale for my images of fantasy.”

49

top left: Enveloped 2020 pigment print

bottom left: The Wedding Guest 2005 pigment print

pat brassington

installation from left: (1-2) Split 2020 pigment print

Pillow Talk 2005 pigment print

(page 53 detail)

(3-4) Enveloped 2020 pigment print

Mouse Trap 2005 pigment print

(5-6) Scent 2020 pigment print

The Wedding Guest 2005 pigment print

51 pat brassington

LOUISA CHIRCOP

52

Louisa Chircop’s works explore the subconscious and “the shadows of the self,” deeply influenced by personal experiences as well as various movements in art history including Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism and Romanticism. Dreamlike landscapes containing disembodied limbs, headless figures and mysterious forms –some representational, others more abstract – create a surrealist atmosphere which draws the viewer closer to see what the artist has unearthed and portraits take on an extra layer of meaning.

“My work, often set against a backdrop of Boschian earthly delights, purgatory, heaven or hell is thematically mixed with elements of the human condition, pain, pleasure, guilt, shame and an invented religious sexuality – one where sex and religion intersect to form a tantra of personal meaning, where sacred meets secular presenting a pagan kind of self-worship that celebrates the earth, universe and spirituality. A corporeal darkness reveals fractures of light, staging metamorphosised, reinvented, hybrid, reborn versions of me. This emanates from my immigrant European lineage originating from medieval roots.”

previous page, left and next page:

Il-grotta ta’ Louisa

(Louisa’s Grotto) 2023 mixed media installation

louisa chircop

55

LYNDA DRAPER

58

Ceramicist Lynda Draper explores the intersection between dreams and reality. Her work is shaped by fragmented images from her surrounding environment, recollected memories, and an interest in material culture. Draper is interested in the relationship between the mind and the material world, and the related phenomenon of the metaphysical. Creating art is a way of attempting to bridge the gap between these worlds.

“Each day begins by stepping out into the quiet pre-dawn with an hour’s walk in the darkness. The world seems a different place, dreamlike, there is a sense of an ancient past. Trees and structures are transformed, it’s silent except for the sounds of nature, the occasional wildlife encounter, hopefully never the legendary black panther. Colours range from pearlescent moonlight and streetlight to pitch darkness, then the creeping distant pink dawn. These night wanderings were a source of inspiration for these sculptures, shaped by fragmented images from my environment, memory, culture and ghosts from the past. They evolved organically, often from a state of subconscious reverie – musings leading my hands to make marks, form clay structures or reassemble fired components. The work aims to invite imagination and the contemplation of some kind of other realm.”

top left and previous page (detail): Dracaena 2021 ceramic, various glazes

bottom left: Dracaena II 2023 ceramic, various glazes

lynda draper

61

FREYA JOBBINS

64

Using the first line in the song Bedtime Story (Madonna, 1995), from which this exhibition takes its title, Freya Jobbins’s work features a physically strong woman wearing a moretta mask, deliberately distancing herself from others by rendering herself silent and covering her face. A moretta mask is a black circular mask covered in black velvet which was only worn by women, held onto the face by biting down on a button on the inside. It was popular in Venice and Paris in the 17th and 18th centuries. For women of this time, it offered them more freedom, anonymity and the ability to not acknowledge others if they so chose.

“This self-empowering mask lets the woman take control and decide as to whether she wants to remain anonymous and silent, away from the objectification by the male gaze but, also, when it comes to wearing a mask, less information sparks more attraction in the unconscious mind, probably due to our neurology being forced to revert to ideal or more desirable features, because this is a stronger feature of our unconscious.”

this page, opposite and previous page (detail): TODAY IS THE LAST DAY THAT I AM USING WORDS from The Moretta Series #2 Kayte 2023 plastic assemblage on plaster bandage mask & digital print

67

freya jobbins

DEBORAH KELLY

68

70

Using images painstakingly cut from old magazines and abandoned encyclopedias Deborah Kelly creates collages of hybrid figures that recall the work of Hannah Höch and Dada artists of the early 20th century. The resulting works make elaborate, fierce, queer claims for space, both historical and representational – an uncanny fusion of bodies, animals and insects presented as static collages or a hyper-kaleidoscope of frenetically dancing creatures.

“These three recent collage works continue my life-long preoccupation with representations and mythologies of ‘The Feminine’ vs lived experience of consciousness in a body assigned female. They prod at and play with femme archetypes – the wasp waist, the queen bee, the ageing beauty – and conjure their shadows: desire and death.”

from left and previous page (detail):

Death Cult 2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, gouache on Moulin de Larrocque handmade cotton paper

Birth of Beeness 2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, on Garza handmade cotton paper

Waspwaist 2016-2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, on Garza handmade cotton paper

deborah kelly

71

74

“The Gods of Tiny Things is an experimental collaborative animation considering life in peril. At collage camp at Bundanon in beautiful Yuin Country we dreamt up personifications of our fears, our impossible appetites. Over an intense week of study and practice, we conjured figures and landscapes as heralds of grief and warning. The Gods of Tiny Things thinks about the current array of threats to life; the tolls of colonialism, climate catastrophe, human profligacy; and conversely the dynamic, kaleidoscopic pleasures of life itself, in all its teeming, prancing, clamouring fertility. We are dancing at the end of time.”

Deborah Kelly

The Gods of Tiny Things 2019 Gallery edit: two channel digital animation, colour, sound 04:00

Made on unceded Yuin Country, NSW Animation Melody Li

Sound design and score Justin Ashworth

Original composition Lex Lindsay

Collage figures Joanne Albany, Alana Ambados, Kate Andrews, Justin Ashworth, Kathryn Bird, Karen Golland, Amanda Holt, Deborah Kelly, Kath Lim, Lex Lindsay, Megan Rushton, Rie

Tamaoke, Anna Tregloan

Commissioned by Bundanon Trust

previous page installation and opposite (still detail): The Gods of Tiny Things 2019 two channel digital animation, colour, sound

deborah kelly

75

MADELEINE KELLY

76

Madeleine Kelly’s work engages with human encounters with “nature” and elemental forces. Bringing together figuration and abstraction, her practice is a mixture of the cosmic and the material that explores the many points of contact between people, animals and plants.

“Mnemosyne carries all the weight of our collective unconscious embedded in our desire to find/understand the shape of things. Spirals have a double movement that opens outward or draws back, a twofold rhythm of liveliness and creation, and withdrawal and entropy. This inward outward motion is a pattern recording the material life of time. The figure in the background is appropriated from 15th century work ‘Burial of the Wood’ by Piero della Francesca.

In Earth drill, Chthonic birds float around the drill’s spiral. Their elongated tongues reach out to forms akin to the neural synapses of the mind, where branched forms metaphorically float around in watery heads. The painting might be considered an oily network of memory. A bird’s branched tongue could exemplify the brain inside out, a treelet waiting to reanimate form or pollinate transmitters of meaning. A mould for industrial manufacturing doubles as the sun while other moulds spin out in the underworld.”

79 madeleine kelly

top left:

Mnemosyne 2018-2023 oil on polyester

bottom left and previous page (detail): Earth Drill 2023 oil on polyester

JUZ KITSON

80

82

Juz Kitson’s works are resplendent and dense. Complex and often large scale, they are exquisite musings on nature’s cycles of metamorphosis, decay, beauty and abundance. Kitson has mastered the use of porcelain and other clay bodies through intricate hand-building and slip casting to create unsettling evocative morphologies. Central to Kitson’s work is the concept of ritual and transformation. There is a deep seated and persistent questioning around the nature of the self, the role of the unconscious and the experience of changing states as we might experience in a dream or a trance. She calls her audience to brave the shadows and experience the vulnerable intensity of pleasure, delight, desire and discomfort.

“This work reflects on the opposing themes of vulnerability and strength, and an undeniable tension after raging wildfires devastated the south coast of Australia and the landscape around my home and studio. It captures the beauty of the dark trees vitrified by fire, despite the charred remains that lay like ruins. It is this form that rises with vigour and reminds us all of the sheer forceful resilience of nature. A sense of intimacy and vastness is captured as the porcelain elements fold along the body, appearing to bristle as if in fight or flight, prompting the audience to acknowledge the entanglements between humans and nature.”

left:

Observe the many ways, liminal spaces bordering things we already know. In memory of the wildfires. 2022

Jingdezhen porcelain, blackbutt timber, steel, resin, silicone, enamel, marine ply

previous page (detail): Formless within ourselves 2023

Jingdezhen porcelain, stoneware, raku, various glazes, fired multiple times

83 juz kitson

HONEY LONG & PRUE STENT

86

Honey Long and Prue Stent have worked together for the past ten years, developing a practice that traverses photography, moving image, performance, installation and sculpture. Their art is grounded in experimentation between bodies, materials and environments, and creates a space for the animate versus inanimate – the human and other – to interweave. ‘We see the body as a microcosm and are constantly exploring environments to find moments, processes or formations that reflect a feeling or speak to the body in some way,’ the artists explain. ‘We try to find points of connection where the outside world and our inner worlds overlap.’

“In these works, from Phanta Firma (2016-2018), we have quoted and appropriated signs, tropes, and motifs of femininity from contemporary culture and the canon of art history as an erotic lure that guides the viewer into unfamiliar territory. Using our own bodies and dream-like environments, the works are a reimagining of classical representations of the female subject and landscape. Embodying Muse, Venus and Siren, the body remains a mysterious agent, veiled and screened behind these different roles. A tension is sustained between conflicting forces, with the figures appearing both vulnerable and powerful at the same time. This emotional charge is shared between subject and landscape, collapsing boundaries between inside and outside and creating a liminal space which speaks to transformation, hybridity and flux.”

top left and previous page (detail):

Body Orbit 2015

archival pigment print

bottom left: Venus Milk 2015 archival pigment print

next page: Salt Pool 2018 archival pigment print

honey long & prue stent

89

LUCY O’DOHERTY

94

96

Working with paint or soft pastels, Lucy O’Doherty take viewers on a dream like journey through nostalgic landscapes and interiors. Devoid of figures, the works have a psychologically unsettling quality, the only hints of human interactions a flashing light on a phone indicating a message, a drawer slightly ajar or a pair of shoes.

“For Think Pynk I was thinking about the history of the colour pink and how it’s currently at peak popularity within popular culture, but also the difference in attitude towards hyperfemininity in popular culture and feminism from the 1970s to now.

With The first room the restaurant experience is a metaphor for being in the womb, which is the first ‘room’ we all inhabit, and comments on how the womb (like a restaurant) is treated like a public space with many people and governing bodies feeling entitled to an opinion on what should happen inside the womb.

Empty pool, erupting volcano and looming clam shell is an expression of my personal dreamscape, populated by an empty pool and an erupting volcano symbolising male and female genitalia and my anxiety over whether I’ll have children, as well as the strange position women are in today where we are still encouraged to fulfil the traditional gender role of becoming a mother while also grappling with the uncertainty of a warming earth and increasingly frequent natural disasters.”

previous

(detail):

97 lucy o’doherty

top left: The first room 2023 soft pastel on paper

bottom left: Think Pynk 2023 oil on linen

page

Empty pool, erupting volcano and looming clam shell 2023 oil on linen

JENNY ORCHARD

100

102

Jenny Orchard is a celebrated artist working across ceramics, painting, drawing and collage. She is well known for her bold figurative hybrid ceramics called Zookiniis or Interbeings, totemic forms and vessels, which she has made since the early 1980s. Her current work is preoccupied with exploring liminal states of being and celebrating the diversity of material form.

“These totemic creatures may appear to spring from the arms of my dreams wholly formed, but there is always a wild dance between the idea, the unconscious desire to bring them into the world, and the possibilities and limitations of the materials used. The serendipitous emergence of their presence and identity is always a surprise to me. Once completed they invade my consciousness with their narrative, their stories have a unifying grounding in their inbetweenness, the sharing of substance and identity. They are all the same matter of the world. They (and we) are the remains of everything; the prehistoric longings, the inconceivable destinies, our consciousness coincides virtually with everything in the world. I want them to ask that question ‘who are we?’”

left: Who Are We? 2023 ceramics, various glazes installation detail

previous page (detail): Recombinant delinquent warrior wall 2023

digital print from handdrawn and digitally rendered drawings

next page: Who Are We? 2023 ceramics, various glazes

103

jenny orchard

“Recombinant DNA and biotechnology manipulates and recombines the genes of animals and plants. This technology has been in use for decades to create transgenic organisms, usually they are not given names. The ethical and philosophical questions around

these emerging new species is the reason I ask ‘who are we?’ The wall is my dreamscape of transgenic creature friends.”

106

Recombinant delinquent warrior wall 2023 digital print from handdrawn and digitally rendered drawings

107

jenny orchard

JILL ORR

108

110

Jill Orr’s performance works have delighted, shocked and moved audiences for several decades. Orr was a key figure in the performance art movement of the 1970s and her ongoing practice continues to be hugely influential. She is widely recognised for her seminal 1979 performance Bleeding Trees. Her practice centres on issues of the psycho-social and environmental where she draws on land and identities as they are shaped in, on and with the environment, be it country or urban locales. Her physically demanding performances and resulting documentation often feature a surreal, dystopian landscape in which she uses her body as an ‘emotional barometer’ placed between the natural and unnatural.

“These images are taken from a live performance titled Laundry, created for Temporal Proximities, curated by Kelli Alred. The event was held in the Magdalen Laundries at the Abbottsford Convent in Melbourne. This is a space that has an intense history of women who worked there. Their work and lives are felt through the very bones of the architecture. The performance was a response to the history and the site.”

opposite, previous page (detail) and next page:

Laundry 01 series 2019

archival pigment prints

Photographer: Clare Rae for Jill Orr

111 jill orr

PATRICIA PICCININI

114

Meditations of the continuity of vitality series 2014 including from top left: The casting vote, Eighteen Jizo, Duplicate Bridge, Constrained by nets, Emotion restrained by reason ink and gouache on paper

116

Patricia Piccinini’s work encompasses sculpture, photography, video and drawing and her practice examines the increasingly nebulous boundary between the artificial and the natural as it appears in contemporary culture and ideas. Her surreal drawings, hybrid animals and vehicular creatures question the way that contemporary technology and culture changes our understanding of what it means to be human and wonders at our relationships with – and responsibilities towards – that which we create. While ethics are central, her approach is ambiguous and questioning rather than moralistic and didactic.

“These drawings are a series of explorations of ideas and aesthetics that excite me. They are a space in which I can think about Surrealism, for example, which is as central to my broader practice as realism is. These works are emotional, and funny, free and perhaps a bit obsessive. Drawing has always been at the core of my practice and these drawings often become something very fleshy.

For me, hair is one of the great symbols because it is so amorphous and can be so many things at once. It is ambiguous but emotive and beautiful. Hair is living but it is not alive. It is sensuous but it has no feelings. Hair is never fixed, we can transform our hair into whatever we choose but at the same time it will always try to return to a tangle. What we do to our hair expresses both our interiority and our relationship to social pressures. Hair is one of these things that is used to divide us but it is also what unites us with all other mammals.”

Next page:

Meditations of the continuity of vitality series 2014 installation view

Egg/Head 2016

silicone, human hair installation view

patricia piccinini

117

CAROLINE ROTHWELL

120

122

“

Caroline Rothwell’s multidisciplinary and research driven practice explores the intersection of art and science through sculptures, installations, animations and digital collages that invite viewers to consider our relationship with the natural environment. Part human and part plant, these surreal sculptures in which rib cages morph into botanical forms, comment on the interconnectedness of botanical, human and industrial systems.

I’ve been thinking about the systems and complex structures that surround us: from the ecosystems and carbon cycle that run our planet; the circulatory system that runs our body; the industrial system of pipes and cables that controls the flows of water, energy, data etc. And particularly trying to think through the need for us to consider ourselves alongside and interconnected with nature’s systems rather than above.

At the same time, my studio headspace is about making and building and messing with the structures of sculpture, drawing etc and I try to turn off my ‘logical’ brain to find the fictitious space where these ideas can be brought into our consciousness in a way that is harder to speak to but perhaps clearer.”

left:

Sylvan body (copper) 2023

hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, copper leaf, plug, composite materials

previous page:

Sylvan body (silver) 2023

hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, metal leaf, composite materials

123

caroline rothwell

installation image from left: Caroline Rothwell Ladder 2022

canvas, hystrostone, steel, encaustic beeswax, bioresin, false nails

Sylvan body (silver) 2023

hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, metal leaf, composite materials

Sylvan body (copper) 2023

hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, copper leaf, plug, composite materials

JULIE RRAP

126

128

Working across photography, sculpture, performance and video, Julie Rrap has played a seminal role in contemporary feminist art in Australia. Using her own, often naked body, she challenges and reinterprets the representation of the female body. She has commented that her practice has strong synergies with the surrealist movement and those artists’ use of the female form, but in a contemporary context and with a feminist representation of the female body.

In this body of work, aluminium casts of Rrap’s hands appear almost suspended in space, making a series of gestures and actions. Rrap has explained that the titles create a narrative and enable the viewer to imagine the sounds and actions she was performing.

“As a group…, these actions become characters in a conversation. These instruments can be performative, musical, surgical, tool-like – they are intended to encourage the audience to participate. Direct silicon casting from my own hands creates a fidelity to detail that renders these objects as uncanny, echoing the Surrealist interest in fragmented human body parts.”

clockwise from top left: Instrument

2015: Measuring; Touching and Pointing; Counting; Whistling

previous page detail:

Instrument: Hooting

2015

cast aluminium and steel

next page: Instrument 2015

cast aluminium and steel

installation view

julie rrap

129

MARIKIT SANTIAGO

132

134

Marikit Santiago’s works are intensely personal and autobiographic. Her hyper-real painting style is often combined with sculpture and installation to create works that reference Catholicism, Renaissance painting and popular culture to comment on her Filipino heritage and her role as a mother and woman artist.

This self portrait of the artist references Beyoncé’s iconic 2017 photograph to announce the birth of her twins in which the singer wore a blue veil to reference the Blessed Virgin, and her pose echoed Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. The juxtaposition of the cyanotype negative and blocked white space against Santiago’s bare skin and the floral background, creates a surreal layering of images.

“The work examines attitudes surrounding colonial mentality and conflicting, simultaneous sensations of vulnerability and empowerment, maternal sacrifice and hedonistic desires, acceptance and rejection. The work speaks of pride in my body for growing and nourishing now three lives.”

left and previous page

(detail):

Renaissance 2018/2023

acrylic, oil and pyrography on ply

floral arrangement by Florian Pigeon, Fleur de Flo

135

santiago

marikit

JELENA TELECKI

136

138

Jelena Telecki was born in Yugoslavia and lived in Croatia and Serbia before leaving her homeland and migrating to Australia during the Yugoslav Wars (1991-2001). Her uncanny and ambiguous images often look at historical and presentday representations of power and power dynamics. Her works trace this interest and stem from her consideration of how women were and are represented in the media, and how these representations inform our self-awareness and the way we negotiate our daily lives and relationships.

“ Attached is a work that is a delayed response to Terry Woronov’s anthropology lecture on love, money and marriage.

Rude is a response to being pressured on behalf of my Serbian family to dye my hair and hide greys. In my country, women who leave their grey hair visible are often perceived as having bad manners and being rude for allowing everyone to see their aging process. There is an expectation from women to be disciplined and well presented – and this excludes having grey hair.

Suit (which was commissioned for this exhibition) is a painting based on the images of the 80s women power suits and the use of garments in the working environment as a means of signalling domination and power.”

139

previous page (detail): Attached 2021

jelena telecki next page: installation view

left: Suit 2023 oil on polycotton

oil on linen

check

ANNE WALLACE

142

144

Anne Wallace’s realist paintings are both strangely familiar and anxiously unsettling. Her work is influenced by film, music and literature and investigates themes of anxiety, childhood memories and personal identity. Often depicting women and suburban interiors, there is a nostalgia in her work that immediately draws the viewer in to her often absurd or dream-like scenes. Resembling film stills, she has the ability to create tension and suspense in her imagesbetween the real and the unreal - where there is the possibility for something to happen, yet the viewer is given only a single frame in a potentially larger story and must make their own narrative.

“The most interesting stories to me are the ones that involve women; the way they’re placed in the world, the way they’re looked at, the way they don’t necessarily have any agency in some situations. I’m old enough to have experienced a bridge between two generations. Feminism is now something that we can assume has made an impact, but when I was growing up it wasn’t really like that. It’s partly the background that I had and the school that I went to, but women seemed to not be owning the images of themselves, and had to endure representations of themselves.”

opposite top: Pythoness 2022 oil on linen

opposite bottom: Nerves 2017 oil on linen

145

wallace

anne

KAYLENE WHISKEY

146

148

Kaylene Whiskey is a Yankunytjatjara artist who paints at Iwantja Arts in the APY Lands in South Australia. Whiskey has a distinct style that synthesises desert and popular culture into humorous and riotous images that combine traditional dot iconography with cartoon speech bubbles and portraits of pop culture icons such as Tina Turner, Dolly Parton, Cher and Wonder Woman. In Whiskey’s world these pop culture divas, along with Whiskey’s own creation of a black wonder woman, become kungka ku n pu (strong women) who are speaking in language and going about daily life in Indulkana.

Ngura Pukulpa – Happy Place brings Whiskey’s collision of pop and A n angu culture to the screen. The work was originally commissioned by Melbourne Art Foundation in partnership with the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI). Combining live-action and animation, Whiskey and her entourage of seven kungka ku n pu (strong women) dance and travel through the red desert of Indulkana in a vivid dreamscape.

opposite, previous page and next page

(detail):

Ngura Pukulpa - Happy Place 2022 (still) single channel video

kaylene whiskey

149

AMANDA WILLIAMS

152

154

Amanda Williams’s practice presents a feminist critique of the history of photography and architectural modernism. Often using vintage equipment and papers with expired processing chemicals, she offers a subtle comment on the apparent obsolescence of analogue techniques and technologies. Darkroom experimentation including bleaching or solarising with extra light, removes, enhances or shifts tonal variations in the images.

“Or your shadow, rising to meet you is a continuing series of works that reflect my interest in the history of photography, and the elemental properties of light, time and the experience of being in physical environments. The installation forms a symbolic representation of a private place, my home, and my relationship with my daughter. It

offers a call and response between the original four photographic ‘portraits’ made in 2020, and a new four-panel mural scale photogram, depicting the warp and weft of a single piece of linen fabric.

The title is a riff on a line from the opening section of The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot which I read in 2020. It felt unexpectedly resonant and relevant. The poem was written in 1922, during a period characterised by post world-war weariness, Spanish Flu pandemic and a palpable sense of disconnection and desolation. A new reality was needed and heralded, one that … severed ties with the past while exploring (exorcising) the deep shadows that were lurking in the recesses of dystopian visions of the early 20th century: Cubism, Surrealism, Dada, Futurism et al., providing the ‘new’.

opposite:

Or your shadow, rising to meet you series 2020

top (#2, #3)

bottom (#5,#6)

gelatin silver hand print on fibre-based paper

previous page (detail): Untitled linen IV from Or your shadow, rising to meet you series

2020-2023

gelatin silver hand print on fibre-based

amanda williams

155

156

Or your shadow, rising to meet you 2020-2023 gelatin silver hand print on fibre-based paper and unique silver gelatin photograms installation view

157

Amanda Williams

list of works

DEL KATHRYN BARTON

Born 1972 Sydney, Australia

Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

love wants to give 2022 acrylic on linen

240 x 200 cm

Private Collection

RED 2017 film

15:00

Written and Directed by Del Kathryn Barton see page 47 for full credits

represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery Sydney, A3, Berlin and Albertz Benda, NYC

VIVIENNE BINNS

Born 1940 Wyong, Australia Lives Ngunnawal land/Canberra, Australia

Drawings of God 1990 biro, pencil, ink and pen on paper 78 x 91 cm

represented by Milani Gallery, Brisbane and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

PAT BRASSINGTON

Born 1942 Hobart, Australia

Lives Muwinina land/Hobart, Australia

Bloom 2003 pigment print, ed of 6 + 2 AP, 5/6 78 x 56 cm

Enveloped 2020 pigment print, ed of 6 + 2 AP, 4/6 75 x 75 cm

Mouse Trap 2005 pigment print, edof 6 + 2 AP, 3/6 85 x 63 cm

Pillow Talk 2005 pigment print, ed of 6 + 2AP, AP1 84 x 62 cm

Scent 2020 pigment print, ed of 6 + 2 AP, 4/6 75 x 75 cm

Split 2020 pigment print, edition of 6 + 2 AP, 4/6 75 x 75 cm

The Wedding Guest 2005 pigment print, edition of 6 + 2 AP, 3/6 84 x 62 cm

represented by ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne and Bett Gallery, Hobart

LOUISA CHIRCOP

Born 1974 Sydney, Australia Lives Dharawal land/Sydney, Australia

Il-grotta ta’ Louisa (translation from Maltese: Louisa’s Grotto) 2023 installation various dimensions

represented by Galerie HEIMAT, France louisachircop.com

LYNDA DRAPER

Born 1962 Sydney, Australia Lives Dharawal land/Illawarra region, Australia

Dracaena 2021 ceramic, various glazes 115 x 70 x 70 cm

Dracaena II 2023 ceramic, various glazes 50 x 50 x 24 cm

represented by Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney lyndadraper.com

FREYA JOBBINS

Born 1965 Johannesburg, South Africa

Lives Dharawal & Gundungurra Country/Picton, Australia

TODAY IS THE LAST DAY THAT I AM USING WORDS from The Moretta Series #2 Kayte 2023 plastic assemblage on plaster bandage mask & digital print 14 x 15 x 5 cm (mask) 330 x 240 cm (print)

freyajobbins.com

DEBORAH KELLY

Born 1962 Melbourne, Australia Lives between Gadigal Country/ Sydney and Jerrinja Country/ Currarong, Australia

Birth of Beeness 2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, on Garza handmade cotton paper 30.5 x 45 cm

Death Cult 2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, gouache on Moulin de Larrocque handmade cotton paper 32.7 x 40.5 cm

The Gods of Tiny Things 2019 two channel digital animation, colour, sound 05:25

Collage figures: Joanne Albany, Alana Ambados, Kate Andrews, Justin Ashworth, Kathryn Bird, Karen Golland, Amanda Holt, Deborah Kelly, Kath Lim, Lex Lindsay, Megan Rushton, Rie Tamaoke, Anna Tregloan

Waspwaist 2016-2017 collage, pure pigment, ink, on Garza handmade cotton paper 31 x 40.5 cm

represented by Wagner Contemporary, Sydney

158

MADELEINE KELLY

Born 1977 Freising, Germany

Lives Dharawal Country/ Wollongong, Australia

Earth Drill 2023 oil on polyester 137 x 101 cm

Mnemosyne 2023 oil on polyester 101 x 137 cm

madeleinekelly.com.au

JUZ KITSON

Born 1987 Sydney, Australia

Lives Yuin Country/south coast NSW, Australia

Formless within ourselves 2023 Jingdezhen porcelain, stoneware, raku, various glazes, fired multiple times

80 x 35 x 13 cm

Observe the many ways, liminal spaces bordering things we already know. In memory of the wildfires. 2022

Jingdezhen porcelain, blackbutt timber, steel, resin, silicone, enamel, marine ply

115 x 46 x 40 cm

represented by Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne and Jan Murphy Gallery, Brisbane thearthousemilton.com

HONEY LONG & PRUE STENT

Honey Long/Prue Stent: Born 1993

Sydney, Australia

Live Narrm/Melbourne, Australia

Body Orbit 2015

archival pigment print, edition of 5 + 3 A/P, 5/5

72 x 108 cm

Salt Pool 2018

archival pigment print, edition of 3 + 3 A/P, AP2

106 x 157 cm

Venus Milk 2015

archival pigment print, edition of 3 + 3 A/P, 3/3 106 x 159 cm

represented by ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne honeyandprue.com

LUCY O’DOHERTY

Born 1986 Sydney, Australia Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Empty pool, erupting volcano and looming clam shell 2023 oil on linen 50 x 76 cm

The first room 2023 soft pastel on paper 47 x 72 cm

Think Pynk 2023 oil on linen 50 x 76 cm

represented by China Heights Gallery, Sydney and Jhana Millers Art Gallery, Wellington

JENNY ORCHARD

Born 1951 Ankara, Turkey Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Recombinant delinquent warrior wall 2023 digital print from hand-drawn and digitally rendered drawings 281 x 572 cm

Who Are We? 2023 ceramics, various glazes variable dimensions overall installation 200 x 300cm

represented by Despard Gallery, Hobart jennyorchard.com

JILL ORR

Born 1952 Melbourne, Australia

Lives Narrm/Melbourne, Australia

Laundry 01 series 2019

archival pigment prints

110 x 151.8 cm / 110 x 86.7 cm (x2)

Photographer: Clare Rae for Jill Orr

represented by THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne jillorr.com.au

PATRICIA PICCININI

Born 1965 Freetown, Sierra Leone

Lives Narrm/Melbourne, Australia

Meditations of the continuity of vitality series 2014

including: Constrained by nets; Duplicate bridge; Eighteen Jizo; Emotion restrained by reason; The casting vote ink and gouache on paper

56 x 76 cm each

Egg/Head 2016

silicone, human hair, edition 2 of 3 + 1AP

45 x 30 x 30cm (sculpture)

represented by Roslyn Oxley9

Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco and Yavuz Gallery, Singapore patriciapiccinini.net

CAROLINE ROTHWELL

Born 1967 Yorkshire, England

Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Ladder 2022

canvas, hystrostone, steel, encaustic beeswax, bioresin, false nails

259 x 50 x 110 cm

Sylvan body (copper) 2023

hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, copper leaf, plug, composite materials

86 x 44 x 40 cm (sculpture)

159

Sylvan body (silver) 2023 hydrostone, canvas, steel, bioresin, metal leaf, composite materials 138 x 38 x 38 cm (sculpture)

represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne and Yavuz Gallery, Singapore carolinerothwell.com

JULIE RRAP

Born 1950 Lismore, Australia Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Instrument 2015 incl. Spying, Framing, Hooting, Whistling, Peeping, Counting, Measuring, Touching and Pointing cast aluminium and steel, edition of 5 + AP1

represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne julierrap.com

MARIKIT SANTIAGO

Born 1985, Melbourne, Australia

Lives Dharug land/Sydney, Australia

Renaissance 2018/2023

acrylic, oil and pyrography on ply 132 x 65cm (painting)

floral arrangement by Florian Pigeon, Fleur de Flo

represented by The Something Machine, Bellport NY

JELENA TELECKI

Born 1976 Yugoslavia

Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Attached 2021 oil on linen 61 x 51 cm

Rude 2021 oil on linen 51 x 59 cm

Love Collection

Suit 2023 oil on polycotton 157 x 119 cm

represented by Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney jelenatelecki.com

ANNE WALLACE

Born 1970 Brisbane, Australia Lives Narrm/Melbourne, Australia

Pythoness 2022 oil on linen 92 x 123 cm

Nerves 2017 oil on linen 86 x 56 cm

Nikki Whelan Collection, Brisbane

represented by Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney and Kalli Rolfe

Contemporary Art

KAYLENE WHISKEY

Born 1976 Mpartnwe/Alice Springs, Australia

Lives Indulkana Community, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, Australia

Ngura Pukulpa - Happy Place 2022 single channel video 08:07

represented by Iwantja Arts, Indulkana and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

AMANDA WILLIAMS

Born 1975, Sydney, Australia

Lives Gadigal Country/Sydney, Australia

Or your shadow, rising to meet you 2020-2023

gelatin silver hand print on fibrebased paper and unique silver gelatin photograms

represented by The Commercial, Sydney awilliams.com.au

right: Il-grotta ta’ Louisa (Louisa’s Grotto) 2023 mixed media installation view

160

Image credits:

All photos by silversalt photography unless indicated below

Opposite: Julie Rrap Instrument: Peeping 2015 (installation detail)

Inside cover: Honey Long & Prue Stent, Venus Milk 2015. Courtesy the artists and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne

Page 4: courtesy of the artist and Kalli

Rolfe Contemporary Art, Melbourne

Page 15: Photo: Clare Rae, courtesy of the artist

Page 21: courtesy of the artist

Page 23, 40: courtesy of the artist

Page 27: courtesy of the artist and China Heights Gallery, Sydney and Jhana Millers Art Gallery, Wellington

Page 28: courtesy of the artist and Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

Page 37-38: courtesy of the artist

Page 47-48 courtesy of the artist and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne

Page 59-60: courtesy of the artists and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Page 65-66: courtesy the artist

Page 69, 74: courtesy of the artist

Page 77, 78: courtesy of the artist

Page 81, 82: courtesy of the artist and Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

Page 87-91: courtesy of the artists and ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne