Hearing Health Summer 2022

A Publication of Hearing Health Foundation

hhf.org

The Family Voices Issue Parents and children living well with hearing or balance conditions

h e a ri n g h e alt h fo u n dation

Catch every word, every call You don’t want to miss a single detail. Trust CapTel® for accurate word-for-word captions of everything your caller says. CapTel keeps you connected to the important people in your life, confident you’ll catch every word.

CapTel 2400i

www.CapTel.com 1-800-233-9130 FEDERAL LAW PROHIBITS ANYONE BUT REGISTERED USERS WITH HEARING LOSS FROM USING INTERNET PROTOCOL (IP) CAPTIONED TELEPHONES WITH THE CAPTIONS TURNED ON. IP Captioned Telephone Service may use a live operator. The operator generates captions of what the other party to the call says. These captions are then sent to your phone. There is a cost for each minute of captions generated, paid from a federally administered fund. No cost is passed on to the CapTel user for using the service. CapTel captioning service is intended exclusively for individuals with hearing loss. CapTel® is a registered trademark of Ultratec, Inc. The Bluetooth® word mark and logos are registered trademarks owned by Bluetooth SIG, Inc. and any use of such marks by Ultratec, Inc. is under license. (v2.6 10-19)

2

hearing health

hhf.org

The mission of Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) is to prevent and cure hearing loss and tinnitus through groundbreaking research and to promote hearing health. HHF is the largest nonprofit funder of hearing and balance research in the U.S. and a leader in driving new innovations and treatments for people with hearing loss, tinnitus, and other hearing and balance conditions. As part of our outreach, we provide this quarterly magazine for free to our vibrant community of readers and supporters, as well as to the dedicated professionals who work with them. Please subscribe at hhf.org/subscribe and make a donation at hhf.org/donate.

Summer 2022: The Family Voices Issue Hearing and balance conditions affect everyone in the family, sparking opportunities to cope successfully, together.

Timothy Higdon President and CEO Hearing Health Foundation

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

3

Hearing Health The Family Voices Issue

Summer 2022, Volume 38, Number 3

Publisher Timothy Higdon, President and CEO, HHF

Features

Editor Yishane

08 Family Voices We Believe “CI Kids” Can Do Anything. Hiroko Endo 12 Managing Hearing Loss How We Got Our Dad to Say Yes to Hearing Aids. Rohima Badri, Ph.D. 14 Living With Hearing Loss From “Bionic” Kid to Giving-Back Dad. Mark J. Miller 16 Family Voices On Monsters and Music. Cristina Duarte

Family Voices Let’s Let More 19 People Learn About Hearing Loss. Asher Bunkin 20 Managing Hearing Loss Travel Gets Easier for Telecoil Users. Stephen O. Frazier

usic Family Dynamics, 22 M Polsfuss-Style. Sue Baker

24 Media Leaning Into Tinnitus. Morenike Oyenusi 26 Media Unheard No More. Janine McGoldrick 28 L iving With Hearing Loss From Dark Days to a Bright Future. Sahar Reiazi 30 Research Recent Research by Hearing Health Foundation Scientists, Explained.

42 Managing Hearing Loss Explanations for Cochlear Implant Hesitancy—and What Hearing Care Professionals Can Do About It. Nancy M. Williams

Departments

Sponsored

06 In Memoriam 46 Meet the Researcher James W. Dias, Ph.D. Meringoff Family Foundation

44 Advertisement Tech Solutions. 45 Marketplace

Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) and Hearing Health magazine do not endorse any product or service shown as paid advertisements. While HHF makes every effort to publish accurate information, it is not responsible for the accuracy of information therein. See hhf.org/ad-policy.

Cover Takashi Endo with his oldest daughter Sakura (right) and his middle daughter An (left). Photo by Hiroko Endo.

Scan to subscribe or visit hhf.org/subscribe to receive a FREE subscription to this magazine. 4

hearing health

hhf.org

Lee

Art Director Robin Senior Editor

Kidder

Amy Gross

Staff Writers Pat

Dobbs, Shari Eberts, Stephen O. Frazier, Kathi Mestayer

Advertising GLM: 212.929.1300

hello@glmcommunications.com Editorial Committee

Judy R. Dubno, Ph.D. Christopher Geissler, Ph.D. Lisa Goodrich, Ph.D. Anil K. Lalwani, M.D. Rebecca M. Lewis, Au.D., Ph.D., CCC-A Joscelyn R.K. Martin, Au.D. Board of Directors

Chair: Col. John T. Dillard (U.S. Army, Ret.) Sophia Boccard Robert Boucai Judy R. Dubno, Ph.D. Jason Frank, J.D. Jay Grushkin, J.D. Roger M. Harris Elizabeth Keithley, Ph.D. Cary Kopczynski Sharon Kujawa, Ph.D. Anil K. Lalwani, M.D. Michael C. Nolan Paul E. Orlin Robert V. Shannon, Ph.D. Nancy Young, M.D. Hearing Health Foundation 575 Eighth Avenue #1201, New York, NY 10018 Phone: 212.257.6140 TTY: 888.435.6104 Email: info@hhf.org Web: hhf.org Hearing Health Foundation is a tax-exempt, charitable organization and is eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions under the IRS Code 501(c)(3). Federal Tax ID: 13-1882107 Hearing Health magazine (ISSN 2691-9044, print; ISSN 2691-9052, online) is published four times annually by Hearing Health Foundation. Copyright 2022, Hearing Health Foundation. All rights reserved. Articles may not be reproduced without written permission from Hearing Health Foundation. USPS/Automatable Poly To learn more or to subscribe or unsubscribe, call 212.257.6140 (TTY: 888.435.6104) or email info@hhf.org.

"When I first discovered the InnoCaption app, I was blown away by its potential to completely change my life and the lives of many other deaf and hard of hearing individuals." Joe Duarte Co-CEO and daily user of InnoCaption

Who We Are InnoCaption is owned and led by two Co-CEOs whose partnership and collaboration led to the launch of the first mobile-focused real-time call captioning service. We are a passionate, purpose-driven team on a mission to provide an empowering accessibility solution for the deaf and hard of hearing community. The InnoCaption Difference Our mission and mindset make our service unique. We focus solely on smartphone technology while our industry mainly offers landline phone solutions. We utilize live stenographers (CART) to provide faster and more accurate captioning despite the higher cost it entails. We are the only captioned phone service provider to offer users the choice between automated speech recognition technology or live assisted captioning on every call. All because we care about our users and put their needs first.

Dr. Olsen (Ringing) (Connected) Family Hearing Services, how can we help you today? You’d like to schedule an appointment with your audiologist? Sure, we can help you with that! What is your name? Thank you, Dr. Olsen can see you this Thursday at 9am. Does that work for you? Okay, great, we will see you on Thursday then! Please don’t forget to bring your ID with you and fill out the patient questionnaire online before arriving. We look forward to seeing you. Have a great day!

Hearing Healthcare Professionals Download our app and register for a demo account if you would like to test our service before recommending it to patients. If you have any questions regarding our service or require assistance, please contact us at healthcare@innocaption.com.

Disclaimer: InnoCaption is ONLY available in the United States. FEDERAL LAW PROHIBITS ANYONE BUT REGISTERED USERS WITH HEARING LOSS FROM USING INTERNET PROTOCOL (IP) CAPTIONED TELEPHONES WITH THE CAPTIONS TURNED ON. IP captioned telephone service may use a live operator. The operator generates captions of what the other party to the call says. These captions are then sent to your phone. There is a cost for each minute of captions generated, paid from a federally administered fund. No cost is passed along to the InnoCaption User for using the service. *911 Calling Advisory: Calling 911 from a landline remains the most reliable method of reaching emergency response personnel.

in memoriam

h ear i ng health foundation

In Memoriam: Bryan Pollard of Hyperacusis Research By the Board of Hyperacusis Research We, the board of Hyperacusis Research, are devastated to report that Bryan Pollard, our founder and shining star, has died at age 57. We are taking this opportunity in the pages of our partner Hearing Health Foundation’s magazine to remember Bryan and his contributions to the field of hyperacusis research. Bryan single-handedly created an entirely new diagnosis in the field of otology—pain hyperacusis—and worked tirelessly on behalf of those who suffered from it. Bryan himself had a noise injury, with symptoms appearing after exposure to a wood chipper removing a tree in his yard. Like many with this kind of noise injury, Bryan was unable to get answers from the doctors he saw. Unlike many, he took action, starting the nonprofit Hyperacusis Research in 2011 and becoming the first non-researcher to present at the Association for Research in Otolaryngology conference, prompting researchers to take seriously the condition of being unable to tolerate everyday noise levels without discomfort or pain. “Bryan was a force of nature,” says Michael Maholchic, who has assumed the presidency of Hyperacusis Research and will carry on the work with the help of the board. This includes our partnership with Hearing Health Foundation and its Emerging Research Grants program. Bryan not only created a new diagnosis, he had to reverse years of the clinical community’s misunderstanding about hyperacusis. Especially important was his influence on changing the harmful myth that quiet was bad for patients with hyperacusis, and his emphasis on the importance of avoiding setbacks, which result from additional noise exposure. He was always responsive to those who sought his counsel and advice. He was all too aware that pain—a key component of this kind of noise-induced injury—was barely mentioned. This is why he used “noise-induced pain,” modeled on the term “noise-induced hearing loss,” in order to make the concept of hyperacusis more understandable to everyone in the fields of audiology and otology. He was also aware that 6

hearing health

hhf.org

Bryan Pollard, second from right, with (from left) Betsy Maholchic, Leslie Liberman, Charlie Liberman, Ph.D., and Michael Maholchic, at a Mass Eye and Ear event in 2017. Liberman is head of an otology research lab at Harvard Med School and Mass Eye and Ear, and Michael Maholchic has assumed the presidency of Hyperacusis Research.

the conventional wisdom passed around to people with hyperacusis—that there was no need to protect against noise—was harmful to many. Patients wanted substantive research into their condition, and Bryan was instrumental in making that happen. He wrote several pieces for professional journals, articles that sufferers found incredibly helpful as they faced a skeptical medical community. In his article “Unraveling the Mystery of Hyperacusis With Pain,” published in ENT & Audiology News in 2019, he noted that the pain component had previously been completely overlooked as part of hyperacusis. The mission was not just to propel a nascent field forward. Bryan had to turn it around first, and he did so with grace and patience. He emphasized the individual and heterogeneous nature of the condition, with the same noise dose having no effect on some people but causing life-

in memoriam

Bryan single-handedly created an entirely new diagnosis in the field of otology—pain hyperacusis—and worked tirelessly on behalf of those who suffered from it. He would become the most prominent patient-activist and the driving force for promoting research nationally focused on this condition. ruining injuries for others. Bryan preferred to make his points by asking questions rather than spouting information. For example, people would sometimes say they improved because they stopped wearing ear protection. In fact, they stopped wearing ear protection because they improved. “Which is the cause and which is the effect?” he often asked. His influence on the field was transformational. “Both audiologists—such as myself—and physicians share responsibility for not knowing more about hyperacusis,” says David Eddins, Ph.D., CCC-A, an audiologist and professor at the University of South Florida. “In my 40-year career, I know of no patient-activist who has influenced the academic and clinical auditory research community in pursuit of knowledge leading to treatment and resolution of his condition as did Bryan,” says Craig Formby, Ph.D., a professor emeritus at the University of Alabama. He adds, “Bryan was a truly unique man from a very humble background. Somehow, while working full-time as an engineer, he would become the most prominent patient-activist and the driving force for promoting research nationally focused on his condition, namely, pain hyperacusis.” Bryan also influenced the careers of several young researchers who are now focused on this new field. “He had the ability to think broadly about how science and medicine should be integrated to advance treatment,” says Paul Fuchs, Ph.D., a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Our own basic research benefited directly from his insight and interest.” Daniel Fink, M.D., credits Bryan for influencing his decision to become a noise activist. He contacted Bryan after seeing him quoted in The New York Times. “For a non-M.D., non-researcher to somehow influence a surgical subspecialty and get its members to do research on a condition, one which he unfortunately suffered from, is truly remarkable,” says Fink, who developed tinnitus and mild hyperacusis after exposure to loud music at a

restaurant on New Year’s Eve. “Most of the time it takes thousands of people with a condition or symptom or complaint years or even decades to get it recognized as a real medical condition,” Fink adds. “For a relatively rare condition like hyperacusis, what Bryan did was just remarkable.” An engineer and a scientist, Bryan made a huge difference in the lives of people with hyperacusis and noise injuries. His passing is such a blow to so many, personally and professionally. His insight gave hyperacusis real validity when faced with a slow-moving and conservative medical community that had been relying on outdated and scientifically unfounded information, and that was as a result unaware of the true nature of the condition. To honor Bryan’s memory, we urge people to donate their ears to science by signing up for the temporal bone registry at Mass Eye and Ear, so that scientists can further their knowledge of hearing disorders. And, of course, we always welcome donations to continue our research and to spread the word about the reality of hyperacusis. From the board of Hyperacusis Research, we are forever in Bryan’s debt. We love you, Bryan. Rest in peace and silence. HHF is very grateful to Bryan Pollard for his work bringing attention to hyperacusis, and to Hyperacusis Research for their ongoing support of our Emerging Research Grants program in the area of hyperacusis. For the National Temporal Bone, Hearing, and Balance Pathology Resource Registry, see masseyeandear.org/tbregistry. For more, see hyperacusisresearch.org and hhf.org/erg.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

7

family voices

We Believe ‘CI Kids’ Can Do Anything Two daughters with hearing loss due to Usher syndrome inspire a family in Japan to open their hearts to the world. By Hiroko Endo I am the mother of three beautiful daughters: Sakura, age 12, An, age 8, and Riri, age 4. When Sakura was born I didn’t know anything about hearing loss. But after An was born I learned a lot about hearing loss. An and Riri both have profound hearing loss due to Usher syndrome type 1 that means they will also begin to develop vision difficulties around the age of 10. They say that necessity is the mother of innovation and that is very true in my case. After our daughters were diagnosed, I found myself feeling helpless and desperate to find solutions for them. I didn’t have a moment of peace because I was stressed all the time. Seeing my distress, my husband Takashi gave me some words of wisdom, 8

hearing health

hhf.org

family voices

Hiroko Endo with her husband Takashi and their daughters (from left) An, Riri, and Sakura. Opposite page: The family lives in Osaka, Japan, and traveled to Australia to learn auditory verbal language skills.

saying, “It’s not right for you to base your happiness on our daughters’ health situation. It’s debilitating.” So the question became: What can we do with what we have? We decided to use our special circumstances as a stepping stone, and that our goal would be to raise our daughters as global people of the future. To figure out how to give our children the best chance for success, I wrote many emails and letters. I made countless phone calls. I visited institutions and centers around Japan to meet with teachers and doctors who know how to best educate children with hearing loss. Finally I met a university professor in Japan who was very helpful. He told me about an innovative way of thinking and educating kids who wear cochlear implants in Australia. I did not know what a cochlear implant was. Now when people in Japan ask me, “What is the meaning of CI?,” I can explain how it stands for cochlear implant, a device implanted into the cochlea, or inner ear, to help children as young as age 6 months hear sounds and acquire speech.

Inspired by the Possibilities

We traveled to Australia as a family, where we learned so much and met so many wonderful people. Our daughters were enrolled in auditory verbal therapy sessions. Their teacher was so inspiring. She believed not only in the abilities of “CI kids” but also in the possibilities they will have in the future. She was such a strong teacher determined to bring out the best abilities of children with hearing loss. I learned that 90 percent of children with hearing loss in Australia attend mainstream schools, thanks to speech and language therapy. I spoke to so many parents who had developed their children’s speech successfully. I then realized that these children are not disabled. The handicaps are not the hearing loss or cochlear implants but rather the low awareness of the parents and caregivers around them about their chances for success.

People in Japan often ask me, “What is the meaning of CI?” And I explain how it stands for cochlear implant, a device implanted into the cochlea, or inner ear, to help children as young as age 6 months hear sounds and acquire speech.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

9

family voices

h e aring health foundation

Opposite page: An (near right) wears cochlear implants, as does her younger sister Riri.

To figure out how to give our children the best chance for success, I wrote many emails and letters. I made countless phone calls. I visited institutions and centers around Japan to meet with teachers and doctors who know how to best educate children with hearing loss. Finally I met a university professor in Japan who was very helpful. He told me about an innovative way of thinking for kids who wear cochlear implants and their education system in Australia. Children with hearing loss are a minority in every country, and those who wear CIs are even more of a minority. So it’s understandable that parents worry about their CI kids fitting in and being able to adapt and succeed in school. I realized adversity is an opportunity and with this in mind, I launched Anfini. It is an online school that teaches English to children around the world who wear cochlear implants. It is the first international school of its kind. I believe strongly that CI kids are the key to opening doors for themselves and others in the future. As the saying goes, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” These students provide hope and inspiration for future generations. They do not “need to be saved” but rather will be the ones helping others, becoming future leaders in a diverse, international society. We have 18 countries represented already! Our current curriculum includes teaching English to students, teaching auditory verbal techniques to parents, and training parents to be coaches. We provide training through videos and written text, even games, and in English and Japanese. In parts of the world, cochlear implantation is a fairly new technology so many parents are not familiar with auditory verbal techniques to enhance learning outcomes. We are taking a parent-coach approach in hopes that parents can teach English and the child’s native language in countries where CI kids do not have access to government-subsidized rehabilitation programs. We have so far conducted trial courses for several sets of Japanese 10

hearing health

hhf.org

parents and received positive feedback about the group activities, the group counseling sessions, and the parentchild English lessons. We’ve also already had many opportunities to meet with other countries through a virtual summer school, international online Meetups, and an online summit. For our inaugural summer program in 2021, CI kids from 15 countries participated. We shared two interviews, one with a ballerina from South Africa and another with a pianist from the Philippines. Both cochlear implant wearers, they talked about their challenges and how they overcame them. I think these inspirational interviews were especially beneficial for the parents because they are positive role models for their CI kids. This January during a global Meetup, representative CI kids from each country introduced themselves in English. We also shared information about the different types of government support and rehabilitation, and the common challenges that we face.

Friends Forever

I would like to introduce a member of Anfini who has quickly become my best friend. Sometimes I think it was a miracle that we met each other. Sahar and I both gave birth to children with hearing loss in our respective countries. I am Japanese and Sahar is an IranianAustralian who was then living in Iran. We both decided that our children needed cochlear

implants. We both chose a center in Australia called Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children (now known as Nextsense) to get speech therapy for our children. The center has over 20 branches in Australia and our children happened to have the same teacher. But that’s not even how we met! Sahar moved back to Iran and I moved back to Japan. Sahar wrote and illustrated a children’s book called “My Cochlear Implants” and sent it out to parents of children with cochlear implants she found on Instagram. She would ask parents if they were willing to translate her book so more children with hearing loss could benefit from her book. She reached out to me and I gladly translated her book to Japanese and that’s how we became friends. As we started to exchange more information about each other we realized that we had so many things in common. We are now best friends, and we work together at Anfini and share the same goals and ideas. Children with hearing loss are a minority in every country, and CI kids are even more of a minority. So it’s understandable that parents would worry about their CI kids fitting in, adapting, and learning in their communities. There are also other issues to think about such as making friends, being bullied, and education. We want these families to expand their horizons from their home country to the world. We want CI kids to become a global community and create lasting friendships like Sahar and I did.

Talking With the World

At first I thought I would have to learn English to make friends in other countries—but I was wrong. The way I see it now, I try harder to learn English once I have made friends outside of my country and am eager to build friendships with them. I haven’t started to teach English to my daughters just yet, but Riri clearly said “watermelon” when a CI kid from Senegal said the word while showing her the fruit. She spoke something in English for the first time!

Hiroko Endo lives in Osaka, Japan. For more, see anfini-global.com or find Anfini on Instagram @anfini_global.

Share your story: Tell us your family’s hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

11

managing hearing loss

hearing health foundat i o n

Opposite page: Take a cue from Aristotle (shown in this statue in Germany) and appeal to your reluctant loved one’s ethical, logical, and emotional senses in order to encourage them to try hearing aids.

How We Got Our Dad to Say Yes to Hearing Aids… …With some help from Aristotle. By Rohima Badri, Ph.D. My dad, without a doubt, is the most challenging hearing aid patient I’ve ever had! And he jokingly says that it was his payback for all my childhood mischief. This is the story of how my family used Aristotle’s three appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos—to encourage my dad to take action on his hearing loss—that is, to try hearing aids! To be honest, we had no idea that our method had its roots in the ancient form of persuasion at the time, but what’s important is that it worked. Hearing loss affects and challenges everyone in the family, not just the person who suffers from it. And one thing we quickly realized was that convincing your loved one to seek help is a marathon that requires a lot of patience, resilience, and empathy. Some of the early signs of hearing loss we noticed in Dad were asking us to speak up, turning up the TV volume, and saying “what?” a lot. Any subtle references to his hearing ability were frequently met with Dad firmly declaring that everything is fine and that the entire world has begun to mumble and speak in fashionably low voices. Often, denial of hearing loss is the first and toughest barrier for the family to crack in the process of getting help for their loved one. If they can accept they have a hearing loss and get a hearing test, that is half the battle won! This is where Aristotle’s three appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos—helped us get our dad into an audiologist’s office. Ethos (appeal to someone’s ethical sense): Establish your credibility by standing by your family member with a hearing loss and gaining their trust. Even though I have a doctorate in hearing sciences and training and experience as an audiologist, I still had to work to earn my dad’s trust that I would be empathetic, supportive, dependable, and 12

hearing health

hhf.org

honest throughout the process. Our family wanted our dad to take action on his hearing loss, but it was important for him to know that when we suggested hearing tests and, eventually, hearing aids, we were keeping his interests, challenges, and needs in mind. As a result, even before we began educating him about hearing loss, we first listened to his stories and challenges, empathized with him, and understood his reluctance without passing judgment. Logos (appeal to their logical senses): Establish your knowledge on the subject and use logical reasoning and sound ideas to educate your family member with a hearing loss. I researched studies and curated articles that would resonate with him. I presented statistics, expert opinions, and testimonials, as well as video clips, illustrating how untreated hearing loss affects overall quality of life. Also, I highlighted the far-reaching effects of untreated hearing loss—isolation, depression, and a decline in cognitive abilities—and the importance of timely intervention. Most importantly, we made sure not to exaggerate or overwhelm but instead let the facts speak for themselves. We gave him time and space to understand and process the information. Pathos (appeal to their emotional sense): Pathos, which means emotion in Latin, is the quickest and most powerful appeal you can make to your loved ones. Connect with your loved one’s emotions without jeopardizing the trust and credibility you’ve built. In other words, we needed to convey the facts to my dad in a way that resonated with him without alarming him as well. Remember, he needed to say yes for himself, not for us, so he wouldn’t become resentful of the entire process.

managing hearing loss

ETHOS Ethics/Credibility Trustworthiness or authority Tone/style

illustration credit: kpu press books, photo credit: flickr/maha-online

PATHOS Emotion Emotional impact Personal connection

We explained the risks of missing important information—sirens, fire alarms, or a cry for help from Mom. We discussed how his hearing loss affected not only him but his entire family. In a caring and non-accusatory manner, we pointed out how his enjoyable conversations and contributions to family time were dwindling, as well as how his tendency to be loud about everything made family gatherings and conversations challenging. He was surprised to learn how much his hearing loss had affected his family members. Last but not least, we explained how his grandchildren were unable to carry on conversations with him and how they were missing out on opportunities to get to know their fun grandpa and build a beautiful relationship. (I believe this one really hit home.)

Taking the Next Steps

“Bah, what’s there to lose?” my dad said loudly a few days later. “Let’s get started on that hearing test you’ve been talking about!” he said in his usual semi-gruff voice. But something changed when he was left standing with a piece of paper that read, “Bilateral mild to severe steeply sloping high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss.” He now had tangible proof that not all is well with his hearing. That, I believe, helped to put things in perspective. Now he was the one who had a lot of questions: “What does it mean? Can it be corrected? Do I have to wear hearing aids now?” We told him to take a deep breath and that he didn’t have to make any decisions just yet, at least not until the next step, the hearing aid evaluation. I explained to him that the hearing aid evaluation allows him to experience what it’s like to wear a hearing aid, ask questions, and

LOGOS Logic/Reason Facts and statistics Scientific evidence

discuss the best course of action. At the hearing aid evaluation, my dad purchased a pair the same day! We were overjoyed as a family. However, buying hearing aids is one thing, making a habit of wearing them consistently is quite another. This is another adventure worthy of its own chapter. My dad now recalls how patient, empathic, and honest his family was throughout the process, even though we’d been waiting for him to say yes to hearing aids from day one. So, if you are wondering about how to encourage your loved ones to take action on their hearing loss, take a cue from Aristotle and appeal to their ethical, logical, and emotional senses with honesty, empathy, and patience. Don’t just convince; connect and converse as well.

Rohima Badri, Ph.D., lives in New Jersey. She is a hearing healthcare adviser for HHF’s Keep Listening prevention campaign. For more, see hhf.org/keeplistening.

Share your story: Have you helped convince a loved one to treat their hearing loss? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate. a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

13

living with hearing loss

hearing health foundati o n

From ‘Bionic’ Kid to Giving-Back Dad A “hearing teacher” who grew up with a hearing loss helps deaf and hard of hearing students navigate school and life. By Mark J. Miller TV’s “The Six Million Dollar Man” was a bit of a savior to me back when I was a kid in the ’70s. The show followed a former astronaut who, after an errant test flight, gets rebuilt with “bionics” that make him extra strong and extra fast. He, of course, becomes a secret agent, and viewers often got to see the electronics embedded in his skin. Meanwhile, I was walking around with a massive Zenith hearing aid under my shirt and a wire popping out of my collar and up to my ear. It helped to be able to tell other kids I was like the Bionic Man. I’d pretend to be able to hear conversations two rooms over through my before-its-time wearable tech. The ruse only worked for so long, but at least we got a few laughs out of it. I was born with a bilateral, mild-to-profound sensorineural loss due to BOR Syndrome, a rare syndrome that can affect your hearing and kidneys; my audiogram looks like a double-black-diamond ski slope. For some unknown reason, I only wore one hearing aid for most of my childhood, but eventually graduated to two behindthe-ear aids and then in-the-canal outfits once I graduated from college and had a little dough (stress on “little”). One of my sisters is also hard of hearing, but we didn’t compare notes too often about our predicament. Other than her, I had never met anyone else who was hard of hearing until my senior year of high school when a girl noticed my hearing aid and told me she had one, too. I was 14

hearing health

hhf.org

completely stunned into silence, not knowing what to say. I still feel bad about it. As an adult, I spent 25 years in the world of magazine and website publishing and absolutely loved it, but a strange thing happened. A good friend who is a teacher kept encouraging me to become a teacher, too, after seeing how much I enjoyed coaching the soccer team our young daughters played on together. While I liked the idea, I also didn’t want to take on a classroom, where it would be hard to hear students in the back. Truth be told, I didn’t want to deal with actually managing the emotional roller coaster of 30 kids, either. Plus, I loved what I did. Every day as a writer was a new adventure with new stories to tell. Then I got a phone call from my pal. “A woman came into my classroom today who is something called a hearing teacher. Have you heard of such a thing?” Well, no, I hadn’t. And so we talked about what hearing teachers do, which is meeting with deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) students and helping them with any social, emotional, academic, and straight-up technical issues related to their hearing. As hearing teachers, we are advocates for our students, teaching instructors, administrators, and even parents how to work with each child’s hearing loss. Then we teach the students to advocate for themselves. The potential impact

living with hearing loss

Opposite page: Coaching his daughter’s soccer team led Mark Miller to recognize how much he enjoys teaching. He became a hearing teacher for students with hearing loss, an adult advocate he wishes he had as a kid growing up (far left).

One of my favorite moments when I meet a new student is when I take out my hearing aids and show them that we have something in common; oftentimes I’m the first fellow hard of hearing person they’ve ever met. I never had a hearing teacher, but I wish I’d had someone who could have helped guide me through the social pitfalls and taught me how to be a better self-advocate. we can have when working one-to-one or in small groups attracted me. It sounded interesting, and also appealed as a way I could give back. One of my favorite moments when I meet a new student is when I take out my hearing aids and show them that we have something in common; oftentimes I’m the first fellow hard of hearing person they’ve ever met. I never had a hearing teacher, but I wish I’d had someone who could have helped guide me through the social pitfalls and taught me how to be a better self-advocate. Instead, I just nodded and smiled before figuring out on my own that there was a better way to go through life. I loved journalism, but I love being a hearing teacher, too. Like my past life, each day brings new characters, new adventures, and new stories. It is an honor to try and help these kids try to figure out where they fit in and how to be sure they can hear to the best of their abilities. Perhaps my work now is a way to make up for leaving my classmate with a hearing loss hanging all those years ago. So now I get to hear the stresses of today’s young kids with hearing loss and relate them back to my own concerns. The world of hearing devices has obviously changed with digital, Bluetooth, and even accessories for hearing aids that make them look like tiny basketballs. When I found myself in the hearing-teacher world, I realized I was reading a ton of hearing-related articles that were extremely helpful, whether it was to show students examples of the cool jobs done by hard of hearing adults, keep up on the tech and political changes happening in the DHH world, or discover all the different forms advocacy could take. I figured my colleagues could use this

same info so I created a little in-house newsletter, which evolved into the Hear Ye website. It’s pretty rudimentary, but the basic idea is to provide a central point for news about hearing issues so people can find it in one place. I try to update it a few times during the course of the week. Some weeks I’m more successful with that than others. While the audience is very specialized, it feels good to know that I’m helping someone out there find the information. Being hard of hearing has certainly shaped who I am. One of the most important lessons I share with my students is discerning the difference between hearing and listening. In the end, we discover that just because we don’t have great hearing doesn’t mean we can’t be great listeners. Most people, hearing or not, aren’t good listeners, but I believe it’s crucial that we all work on this dying art (even if we can’t exactly make out what’s being said two rooms away).

Mark J. Miller is a teacher in the New York City school system. For more, see sites.google.com/view/hear-ye.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

15

family voices

Cristina Duarte with her husband and parents.

On Monsters and Music My life as a real-life “CODA,” child of deaf adults, was both like and unlike that portrayed in this year’s winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture. By Cristina Duarte I cannot tell you how many times in my 32 years people have asked me, “What is it like to have parents who are deaf?” My answer has always been the same, regardless of who is asking or how old I am: “What is it like to have hearing parents?” My parents were both born with profound hearing loss to hearing families. Since they were born into hearing families, they were not raised signing—in fact they both only learned to sign in their 20s when they joined (and met through) Self Help for the Hard of Hearing (SHHH) which has since become the Hearing Loss Association of America (HLAA). As a result of their experiences and upbringing, my parents are both strong lip readers (speech readers), communicate orally, and sign in exact English (SEE)— even my dad, who grew up in Portugal. My mom tells us that neither I nor my siblings really went through the “terrible twos” because we could sign before we could speak, and because of this, we were able to communicate our needs from a young age. 16

hearing health

hhf.org

From what I hear, I was a pretty good signer up until the time I went to kindergarten and saw that none of the other kids signed. Apparently, I came home and confidently informed my parents I would not be signing anymore (what a terrible kid, I know!). Today, as an adult who works in the deaf and hard of hearing community, I sign again. I was beyond excited when I saw the trailer for the film “CODA” (child of deaf adults) for the first time. Even just from watching the clip, I could tell it was going to be good, and probably a little emotional. Once I finally got to watch it, it did not disappoint. I thought the entire cast did a wonderful job, and there were so many points in the movie where I found myself reminiscing about my childhood. It was so wonderful the film won the 2022 Academy Award for Best Picture!

I Can Relate

There were many parts of the movie where I found myself smiling because I felt like I could relate. However, the primary mode of communication in my house growing up

family voices

From what I hear, I was a pretty good signer up until the time I went to kindergarten and saw that none of the other kids signed. Apparently, I came home and confidently informed my parents I would not be signing anymore (what a terrible kid, I know!). Today, as an adult who works in the deaf and hard of hearing community, I sign again. was spoken English. We had communication rules in the house: Always be facing Mom and Dad when speaking to them; don’t cover your mouth while talking; enunciate your words and speak clearly, among other things. I remember my dad used to get frustrated with me all the time because as a teenager I would speak “like a machine gun on fire.” I would get constant reminders that I needed to speak up and slow down. In contrast, in “CODA,” Ruby’s family relies on American Sign Language, which is a very different experience. In my house growing up, my parents had flashers— we called the assistive device a “baby crier.” When the phone rang or the doorbell went off, one of us started screaming, and the lights would flash. My parents used this technology at night to wake them up when a baby was crying. When I was about 6, I went through a phase where I would wake up in the middle of the night and want to go to sleep with my parents. I am sure a lot of kids go through that, but I was also scared of getting out of bed because the “monsters” could get me, and I needed my dad to come get me. Every night—for probably too long—I would wake up and just scream in my bed to cause the lights in my parents’ room to start flashing. Like clockwork, I would see my dad come out of his room and go to the nursery to check on my baby brother. Once my dad realized it was not the baby crying, he would come to my room and see me gesturing to be picked up and carried back to my parents’ room. One night, and I remember it like it was yesterday, I started screaming per usual and watched my dad go to the baby’s room. However, this time when he came out, instead of picking me up, he looked at me, unplugged the baby crier, and went back to his room. To say I was distraught is an understatement. In hindsight I laugh because I could have easily gotten

out of bed and walked myself to their room, but I didn’t. And ultimately it worked—I didn’t wake them up anymore and slept through the night. At the time, I couldn’t believe my father would leave me to the monsters, but that is my most vivid memory associated with being a CODA. My parents always encouraged us to pursue music. My dad, like the dad in the movie, loved music with heavy bass. Now, he didn’t listen to rap, but there was a lot of classic rock and especially in the car, it was always very loud. My mom would get mad at him all the time because we would borrow his car, turn it on, and immediately jump out of our seats because he’d left the music all the way up where he could feel it. I would always laugh, and I loved riding with my dad with the music blasting and windows down. I was obsessed with “The Sound of Music” when I was a kid; I can’t even count the number of times we watched it as a family, and my parents would put it on the loudspeaker as my siblings and I danced around singing. We have multiple home videos of us belting the songs in at home “performances.” I remember when we were singing for our dad back when he had hearing aids, he would place his hand lightly on the side of our throats to feel the vibrations of us singing—also like the father in the movie. I was actually surprised when I saw the father in the movie do that because I had thought it was just something my dad did!

Communication Help

I attribute my communication skills and empathy to my experiences growing up. I think observing my parents’ struggles with lack of accessibility—and specifically seeing so many hearing individuals make it clear that communication with my parents was burdensome—shaped me into the person I am today. I watched my parents gracefully advocate not only for themselves but for others, and I feel like I followed their example. a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

17

family voices

h e aring health foundation

Cristina’s parents, Meg and Joe, in August 1984. They met in 1982 and started dating in July 1983.

The lack of accessibility portrayed in the movie was very real and hit close to home even though my parents’ accessibility needs weren’t the same. While there were many things I noticed, the primary one was the issues with telecommunications accessibility. For as long as I can remember, I would answer the landline phone in the family home. I had everything very well-rehearsed: “Duarte residence, Cristina speaking. How can I help you?” I loved getting to answer the phone and relaying the messages for my parents. Some other CODAs have shared with me that they always felt burdened by the responsibility, but I can’t relate to that because it is something I always enjoyed. I would either take messages down for my parents or listen on the phone and mouth to them what the caller was saying. This was back before captioned telephones and other relay services were available. As I got older, telecommunications relay services started becoming available, but due to delays with the technologies I got to keep my job as the answerer of the phones! When I was at school and had to call my parents from the nurse’s office—which admittedly was frequently because I loved staying home from school—it was a struggle to communicate what was going on. Luckily, I was such a frequent visitor of the nurse’s office that she developed a “yes/no” system with my mom. My mom would ask questions and the school nurse would answer yes or no very clearly. This resulted in me being sent back to class probably 75 percent of the time. When my parents got the InnoCaption app on their cellphones it was the first time I was ever able to reach my parents like my hearing peers. It was incredibly special and to this day I don’t take having that ability to connect 18

hearing health

hhf.org

with them for granted. The InnoCaption technology and the doors it opened for my parents is actually why I specialized in communications law—specifically telecommunication relay services. I can tell you I love my family and how close we are. I know a lot of people say this, but I feel like I have the best parents in the world and I am incredibly grateful to have been born to them. I love being able to sign and where my connection to the community has led me in life. I am grateful for the values my parents instilled in me, which were probably largely due to their experiences growing up hard of hearing. Occasionally I get asked whether I would have preferred to have hearing parents—and while I can say I have no idea what that would have been like, I can also honestly say that I am happy with my family and have never wished that it was different.

Cristina Duarte is the senior director of regulatory affairs at InnoCaption, a mobile app that provides call captioning for the deaf and hard of hearing, where she works with her father. InnoCaption is a promotional partner for Keep Listening, HHF’s hearing loss prevention campaign. “CODA” is available to stream on Apple TV+.

Share your story: Are you a CODA? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

family voices Wearing hearing aids gives Asher Bunkin, shown at near left with his family, an opportunity to teach others about hearing loss.

Let’s Let More People Learn About Hearing Loss By Asher Bunkin My name is Asher and I will start middle school in the fall. I have bilateral, mild-moderate sensorineural hearing loss. When I was around 4 ½ years old I had an ear infection and had a lot of trouble hearing. My mom took me to an ENT (ear, nose, and throat) doctor who treated the ear infection and suggested seeing an audiologist to test my hearing. The audiologist confirmed I had an underlying hearing loss, and then I got my first pair of hearing aids. Even though we have some family history of hearing loss, no one realized I had hearing loss before that ear infection.

It’s important that you don’t let people bring you down for wearing hearing aids. Take the opportunity to explain about hearing loss and using hearing aids. Let them know more about it! After I was diagnosed, I was fitted with hearing aids. They help me hear. If I miss things during conversations, I sometimes change the topic so I can continue to participate in a group discussion. I need to focus on the big picture of a conversation to make sense of what is going on in case I miss words here and there. I also try to read lips and stay close to the person who is speaking. I have trouble hearing people when they are whispering or if I am too far away from the person speaking. I rely on friends to help me if I need something repeated. When

people are talking quickly or wearing masks it is not easy to hear. For example, when I am swimming I can’t wear my hearing aids and as a result cannot hear what is going on around me. Sometimes I run into trouble if my hearing aids shut off during the day—when the rechargeable batteries die. Otherwise, my hearing loss doesn’t stop me from doing anything at all. I would tell someone with a new diagnosis to persevere, know that you can get used to it, and think about the positives and not the negatives. It’s important that you don’t let people bring you down for wearing hearing aids. Take the opportunity to explain about hearing loss and using hearing aids. Let them know more about it! I heard about Hearing Health Foundation from my mother because I was in school with the younger daughter of HHF’s former CEO, Nadine Dehgan. Now my mother works for SoundPrint, the decibel measuring app, which is how we reconnected with HHF. Our family thinks it is important to educate as many people as possible about the research HHF does for hearing health and encourage them to protect their hearing.

Asher Bunkin lives in New York City with his family, including mom Sharon Bunkin, the director of marketing at SoundPrint. SoundPrint is a promotional partner for Keep Listening, HHF’s hearing loss prevention campaign. For more, see hhf.org/keeplistening/partners. Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate. a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

19

managing hearing loss

hearing health foundat i o n

Travel Gets Easier for Telecoil Users In the past couple of years there’s been an explosion of what could be industry-altering hearing loop news in the field of transportation, ready to go for us for when we’re all fully back on the road. By Stephen O. Frazier Hearing loops have been available in the U.K. for years, in airports, train stations, the Underground, and even London taxicabs. They’re now becoming more plentiful in transportation systems here in the U.S. Recent announcements of new hearing loop installations and major plans for their future use in the field of transportation have pushed this time-tested technology to the forefront in efforts to accommodate the special needs of travelers with hearing loss. A hearing loop is a wire that surrounds a defined area and is connected to an electronic sound source such as a public address system. It emits a silent electromagnetic signal that carries the sound from its electronic source to receivers called telecoils (T-coils) in hearing aids or cochlear implant (CI) processors. The majority of hearing aid models currently on the market have (or can be fitted with) telecoils. CI processors also generally come fitted with telecoils, varying by manufacturer. My hearing aids and their telecoils are already optimized to match my audiogram and provide an extra boost to those frequencies I have the most difficulty hearing. Turning them on is simple: In a looped setting I just touch a button on my hearing aid and I’m instantly connected to the loop and its signal. Any number of telecoil users in a room can access the signal from the loop, something that is not possible with Bluetooth, which is basically a 1-to-1 system. Here are some highlights: » The list of airports offering one or more forms of hearing loop technology in their terminals in the U.S. grew from 12 to 20 in just the past year or so. Among those added to the list were the major hubs of LaGuardia Airport in New York City and Los Angeles International Airport. Memphis International is looping the departure gates in a new concourse now under construction, and, thanks to a grant from the Federal Aviation Administration, the Billings, Montana, airport will be including hearing loops in upgrades to their two terminals. In addition, the airports in Minneapolis and Phoenix, both major hubs that already offered the technology, are expanding its presence at a variety of locations within their terminals. » New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) is testing looped city buses. A Hearing Loss Association of America NYC chapter member who volunteered to test says, “We were able to hear announcements from both the bus driver (live) and from outside 20

hearing health

hhf.org

My hearing aids and their telecoils are already optimized to match my audiogram and provide an extra boost to those frequencies I have the most difficulty hearing. Turning them on is simple: In a looped setting I just touch a button on my hearing aid and I’m instantly connected to the loop and its signal. Any number of telecoil users in a room can access the signal from the loop, something that is not possible with Bluetooth, which is basically a 1-to-1 system.

managing hearing loss

Adventures in Looping, Near and Far Since the advent of COVID I’ve not strayed much outside of Albuquerque’s Rio Grande Valley but previously, en route to Paris via Madrid, I listened to Plácido Domingo through my personal (don’t leave home without it) neckloop instead of the offered earbuds on an Iberia Airlines flight. In Paris I used a neckloop for a self-conducted tour of the catacombs under Notre Dame. There was a counter loop at the tourist office in tiny Les Eyzies in rural France, and upon my departure I experienced the loop in a waiting area at Charles De Gaulle Airport. Across the Channel, I used my neckloop in place of the offered earphones with the receiver they provided to hear the prerecorded messages at each of the monolithic stones at Stonehenge in the English countryside. I’ve also been able to talk with agents at subway information/fare booths and at Penn Station in New York City. A theater-provided neckloop let me hear and understand the dialogue in the award-winning “Kinky Boots” musical on Broadway. I regularly attend Hearing Loss Association of America conventions and, of course, all of the meeting rooms are looped so even if I sit in the back row it’s as though I have a front row seat. And at home in Albuquerque there’s a plethora of opportunities to use my telecoils. —S.O.F.

» » »

»

»

(recorded). The sound quality varied between the two sources, but both were pretty good.” The MTA board has approved the funding for over 500 new subway cars dubbed the R262 model that will be fitted with hearing loops. The MTA has also tested the installation of a hearing loop at the busy Bowling Green subway station in lower Manhattan. In July 2021 Amtrak signed a $7.3 billion contract for 83 new train sets (expected to be six cars each) to be built by the German company Siemens in their California plant. They will be fitted with hearing loops and used on the line’s heavily traveled Northeast Corridor routes. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced a set of new accessibility requirements for all transportation terminals it operates. The requirements mandate the inclusion of hearing loops at departure gates and information booths at all new or significantly upgraded airports and at the information counters at rail, bus, and ferry terminals as well. Also recently San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit System (BART) took delivery of a fleet of hearing loop– equipped rail cars and completed the installation of hearing loops at all 50 of the system’s stations.

Prior to these recent developments, hearing loops had already found their way into other travel-related facilities such as New York’s Penn and Grand Central stations, the Intermodal station in Milwaukee that serves short and long distance train and bus passengers, and even New

York City taxicabs. The Rail Vehicles Access Advisory Committee had made a recommendation to the U.S. Access Board to encourage the appropriate federal agency to require that all future rail cars be equipped with hearing loops. All of this points to a future where travel will be just a little bit easier for people who have the little copper telecoils in their hearing aids or cochlear implant processor.

Trained by the Hearing Loss Association of America as a hearing loss support specialist, staff writer and New Mexico resident Stephen O. Frazier has served HLAA and others at the local, state, and national levels as a volunteer in their efforts to improve communication access for people with hearing loss. Contact him at hlaanm@juno.com. For more, see sofnabq.com and loopnm.com. For references, see hhf.org/summer2022-references.

Share your story: Tell us where you use hearing loops at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate. a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

21

Family Dynamics, Polsfuss-Style Each in their own way, Les Paul’s parents nurtured their son to change the music industry. By Sue Baker

Above, from left: George and Evelyn Polsfuss, Les Paul’s parents. Lester Polsfuss, who became Les Paul, with his mom Evelyn, circa 1924. Les and Evelyn. Les and his brother Ralph. Opposite page, top: Les and Evelyn at her 100th birthday party.

22

hearing health

Lester Polsfuss—later known as Les Paul—was the second child of George and Evelyn Polsfuss. They divorced when Les was quite young but they each, in their own ways, helped Les. In his memoir “Les Paul in His Own Words,” Les wrote that his father was “a good man, a great rascal and storyteller.” One could say that also describes Les. George gave Les the nickname “Red” because of his red hair. Les relayed how his father would bring home an assortment of strange gambling winnings. “He was something else, a real trip,” Les wrote. In the 1920s, when teenage Les wanted to build a cutting lathe to record his music, he went to his dad’s auto dealership where George’s mechanic helped Les build his first lathe. After George and Evelyn divorced, Les said his father settled down. It was George, along with Ralph, who invited Les and Mary Ford to perform at the opening of their jointly owned Club 400. Les said Ralph was handsome and outgoing, and the brothers were fond of each other, hhf.org

despite the age difference and their very different personalities. Evelyn Stutz Polsfuss loved both of her sons. Even when Les was a preschooler, she recognized his talent. She would arrange for her young son to perform for local fraternal organizations. Les was so tiny that they placed him on top of a table where he would sing, dance, and tell funny stories. “I did a lot of crazy, stupid things when I was a kid,” Les wrote in his book. “But rather than scold me, she always took pride in the fact that I was thinking creatively and had the initiative to do something.” While Les was still young, his mom gave him his first stage name, Red Hot Red. Les shared, “She always said, don’t look at the negative, look at the positive, and you can do it. And she shoved me out on stage the same way. ‘Go out and get ’em, Lester. Go out and get ’em.’” Les’s ferocious curiosity meant Evelyn was always answering questions. When she did not know an answer, she would take Les to

music

“I did a lot of crazy, stupid things when I was a kid,” Les wrote in his book. “But rather than scold me, [Mom] always took pride in the fact that I was thinking creatively and had the initiative to do something.” While Les was still young, his mom gave him his first stage name, Red Hot Red. Les shared, “She always said, don’t look at the negative, look at the positive, and you can do it. And she shoved me out on stage the same way. ‘Go out and get ’em, Lester. Go out and get ’em.’ ”

the library or to a local teacher. She was determined to help her son be his best. When Les’s favorite musicians came to town, Evelyn found ways to get her son to see the performances. She even took Les to Nashville to see country and blues star DeFord Bailey. When 13-year-old Les wanted to amplify his voice while performing, Evelyn allowed him to use her telephone and radio. Around the same time, Evelyn arranged for Les to perform on a Milwaukee radio station—and from there he never stopped. Even when Les was an adult, Evelyn continually encouraged him to stretch to his full potential. When he was playing his electric guitar professionally, she urged him to sound different from other guitar players. That impetus drove Les to spend two years building his multifaceted sound and a new, solid-body guitar that set the music world upside down. “She was the biggest single influence of my life,” Les said about his mom, “and we were close in a way that never diminished till the day she died at the age of 101 and a half.”

Sue Baker is the program director at the Les Paul Foundation. We are grateful to the Les Paul Foundation for its ongoing support of tinnitus research through HHF’s Emerging Research Grants program.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

23

media

h e ar i n g h e alth foundation

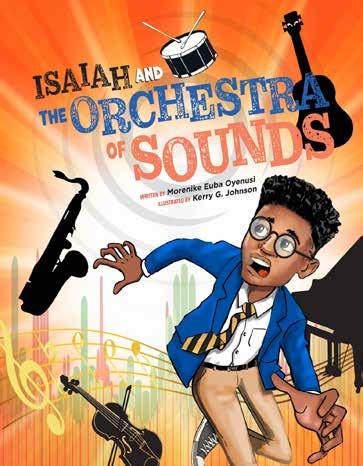

Morenike Euba Oyenusi wanted to create an approachable way to educate young people about tinnitus and how tinnitus can be caused by exposure to loud sounds.

Leaning Into Tinnitus What if the cacophony of tinnitus sounded like an orchestra? By Morenike Euba Oyenusi

My struggle with tinnitus started on Monday, November 25, 2019. I remember that day distinctly because it was my daughter Oyinade’s 19th birthday. I had begun to experience extreme dizziness the day before, so much so that I could not walk initially, and by Monday morning, the dizziness was accompanied by horrible nausea and stomach pain. I urgently implored Tunji, my late husband, to drive me to the nearest emergency room, where I was diagnosed with vertigo. Later that day, the tinnitus symptoms started, and they have been continuous since then. Two weeks later—by which time the other symptoms had thankfully disappeared—I was diagnosed with a partial hearing loss and tinnitus. The tinnitus was a traumatic ordeal for me. I found myself just writing down my thoughts to cope with the terror. This evolved into a poem, which continued to get longer and longer. I became decidedly fascinated by the sounds in my ear—each individual and distinguishable, but with all the 24

hearing health

hhf.org

noises working together to make a complex, incredible sound, just like instruments in an orchestra. There is no other way to describe it. That began the notion of writing about tinnitus as an orchestral performance. My first thought was to have my epistle published as a poem in a literary journal. I sent it to an academic journal, but I had no response. The rejection (or failure to reply) was a marvelous blessing because, several months later, God gave me the idea of turning the poem into a short graphic novel for preteens, teenagers, and young adults. The idea was to create an approachable way to educate these age groups about tinnitus and how tinnitus can be caused by loud noise and hearing loss. (The doctors speculate that, in my case, infection rather than loud noise was more likely the cause of tinnitus and hearing loss.) I was captivated by this vision and looked for an illustrator to help me implement it while working on turning the very long poem into a story. The result is “Isaiah and the Orchestra of Sounds,” with illustrations by Kerry G. Johnson. Our hero, 15-year-old Isaiah, starts

media

I became decidedly fascinated by the sounds in my ear—each individual and distinguishable, but with all the noises working together to make a complex, incredible sound, just like instruments in an orchestra. There is no other way to describe it. That began the notion of writing about tinnitus as an orchestral performance.

to hear terrifying and strange noises in his right ear on a normal, regular day in Baltimore. The story follows his battle with tinnitus. Even though Isaiah is not dealing with musical tinnitus (and I learned only later that there is such a thing), he expresses his experience as that of an alien orchestra performing in his ear. I use the musical performance theme and musical references throughout the book, and I am quite pleased with how all that turned out. I also include resources to help people with tinnitus and advice for noise avoidance. My hope is to have the book in doctors’ offices, schools, and libraries to help teach that loud noise is a very real threat to hearing health and well-being. This is an acute concern given the prevalence of headphone use and loud concerts, and how little cognizance there is of the dangers. The irony is that music is beautiful and pleasant to listen to, but if you listen to it too loudly, you can experience a ghastly orchestra, as Isaiah does, and one that may never stop playing.

Morenike Euba Oyenusi is a NigerianAmerican lawyer, author, and minister who lives in Maryland. Her first book, “Chasing Butterflies in the Sunlight,” was a finalist in the 2021 Next Generation Indie Books Awards. For more, see paradiserestoredpublishing.com.

Share your story: How do you cope with tinnitus? Tell us at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

25

media

h e ar i n g h e alth foundation

Unheard No More An entertainment executive’s search for support sparks the idea to capture Ménière’s disease in a documentary. By Janine McGoldrick It has been nine years since I was diagnosed with Ménière’s disease. “A disease? Am I going to die?” I asked my doctor. He explained Ménière’s wouldn’t kill me but, unfortunately, it is a chronic condition with no cure. I’d have to learn to manage the symptoms and, well, just live with it. Easier said than done. Ménière’s symptoms can include horrible bouts of vertigo and nausea, drastic hearing loss, roaring tinnitus (ringing in the ear), painful ear pressure, extreme fatigue, and severe imbalance—just to name a few. Ménière’s is an “invisible” illness, not widely known and difficult to explain. Google and WebMD became my best friends but are no substitutes for personal empathy and understanding—two things desperately needed by people with an enduring health condition. Unfortunately, hearing a list of symptoms can’t give someone a full picture of what Ménière’s does to you. I have spent nearly a decade struggling to describe my condition to my family, friends, employers, and even strangers on the subway who think I’m drunk because I have difficulty walking straight. Now, I admit I love me some Guinness, but when I explain, “It’s not the alcohol, it’s the Ménière’s,” I’m met with blank stares. Complicating things further is the fact that a Ménière’s “attack” can happen anywhere, at any time, with little warning. One moment you’re fine, working at your desk or 26

hearing health

hhf.org

making dinner. Then, with the flick of a switch, pressure begins to build in your head, you are thrown off balance, and everything around you starts to spin so violently you collapse and can’t move. This can last for a few minutes or a few weeks. As it all takes place inside your head, and happens while you “look healthy,” others—including doctors—are skeptical it’s even occurring, leaving you feeling anxious, depressed, and isolated. Jobs are lost, social engagements are canceled, relationships end. Hearing issues weren’t new to my family as my dad suffered severe hearing loss due to years working with airplane engines and large electrical machinery. But none of us had ever heard of Ménière’s or were prepared for the life changes that would ensue. My mother witnessed several of my Ménière’s attacks— helping me to the bed, scrambling to get my rescue meds, and cleaning up my vomit. Now she is constantly worried about the greater harm that may happen if I have an attack when I am alone or traveling. My brother Michael told me it can be difficult to know exactly how to help family members who have medical ailments, but it’s harder when they suffer from a disease as mysterious as Ménière’s. As much as my loved ones wanted to grasp how much my world has changed they couldn’t. When I found a community of Ménière’s support groups on social media, I heard similar repeated refrains: “No one realizes what I go through”; “My family doesn’t get it”; “I’m alone on this journey.” So I wanted to find a way to give my family,

media Janine McGoldrick (second from right) and her family hadn’t heard of Ménière’s disease before she was diagnosed, and none were prepared for the life changes that come with the condition.

One moment you’re fine, working at your desk or making dinner. Then, with the flick of a switch, pressure begins to build in your head, you are thrown off balance, and everything around you starts to spin so violently you collapse and can’t move. This can last for a few minutes or a few weeks. and many others, a better understanding of the monster called Ménière’s. As a veteran entertainment industry executive, I am acutely aware of the power that film and television have to enlighten, so I decided to develop “Unheard: The Ears of Ménière’s,” a documentary that will shine a light on this debilitating disease which has remained unheard of for far too long. The film will create a visceral viewing experience for audiences so they directly experience the effects of the condition. Through creative camera movements and innovative sound design, it will simulate Ménière’s symptoms so viewers not only learn but also feel. When I mentioned my film idea to my brother he was so excited. He said having visual and auditory examples of the Ménière’s experience would be an invaluable tool for people like him who need to know more about this debilitating illness. Another goal of the documentary is to elevate Ménière’s in the public consciousness and attract funding for more research to find better treatments and hopefully a cure. Research for Ménière’s disease, like many vestibular disorders, is vastly underfunded. In order for people to have a better quality of life, this needs to change. I’m grateful to Hearing Health Foundation (HHF) for supporting our film through recommending medical experts as well as patients of the condition who have shared their stories with HHF. My hope is that Ménière’s

becomes as recognizable as Parkinson’s, diabetes, and multiple sclerosis. So, the next time I need to call out sick, cancel plans, or ask for help in public after stating, “I am having a Ménière’s episode,” I am met with recognition and not incomprehension from family and strangers alike.

Janine McGoldrick is an entertainment strategist and producer. She can be reached via email at janine@2ndchapterproductions.com and on Twitter and Instagram at @2ndChapterProd. “Unheard: The Ears of Ménière’s” welcomes corporate sponsorships and other funding toward production. To learn more, see 2ndchapterproductions.com.

Share your story: Tell us your Ménière’s disease journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

27

living with hearing loss

hearing health foundati o n

From Dark Days to a Bright Future Networking among mothers of cochlear implanted children around the world leads to a solution for a young girl. By Sahar Reiazi Samin lives in Iran. A family friend, Soheila (above, center), accompanied her on the day her replacement cochlear implant processor was switched on. Through a network of cochlear implant families, Samin was able to receive a processor donated from Australia that was used and older—but just like the one she lost.

28

hearing health

hhf.org

Samin was born in a small village in the province of Mashhad in northeast Iran. She is the only person in her family who has a hearing loss. Doctors suggested cochlear implants, and even though her father did not have the money they opted to get the surgery. Her father borrowed the money he needed and Samin was unilaterally implanted in Iran when she was 7 years old. Teachers in her school were impressed as Samin proved herself a fast learner and a bright child. Samin turned 9 and her speech was progressing well. One day when she was riding the bus with her parents Samin dozed off. When they got off the bus, her parents realized the cochlear implant processor wasn’t on her ear. They were devastated. They searched and searched, contacted the bus company, and even filed a statement with the police saying her cochlear implant device had been lost. But the processor was gone. For the first time in two years, Samin had to experience silence. Her family was distraught. Samin cried every day for a month, until she just went silent and communicated with her family through lipreading (speechreading). Her elder brother by two years was upset for his sister, and asked their mother why Samin wouldn’t talk anymore. “I was so distressed that I would lay down all day depressed and hopeless,” Samin’s mom says. “I couldn’t muster up the energy to get up and cook for my own children.” Samin’s mom refers to that time as “the dark days.” They were still paying installments on Samin’s last device and could not afford to buy a new one. Though they appealed to different organizations, all said that due to the long waitlist it could be years until Samin was eligible for a new device—a device the family could not afford to begin with.

living with hearing loss

They searched and searched, contacted the bus company, and even filed a statement with the police saying her cochlear implant device had been lost. But the processor was gone. For the first time in two years, Samin had to experience silence.

I heard about Samin’s story through a mutual friend. I told her I would help raise funds for Samin no matter what. Something inside me woke up, a little flame that would not be put out until I saw Samin with a new device. I started making calls and sending out emails. My mind was working nonstop to find someone I could reach out to. Every day counted, because I would wake up thinking how Samin could not hear, and how that wasn’t fair. So many emails and messages from people across the globe came in, reassuring me that they would do anything within their power to find a device for Samin. One person I contacted was my friend Hiroko in Japan. She was sympathetic because she had two daughters who wear cochlear implants and she could understand Samin’s situation well. After just 48 hours, I received a call from Hiroko. When I picked up and said hello, she said excitedly, “Hi, Sahar. A device has been found for Samin from Australia! It will be donated to her, please contact….” I was crying tears of joy; Hiroko was crying tears of joy. It was one of the best moments of my life. Australia has excellent medical care for their citizens. The country supplies the newest hearing devices and latest technologies for free as part of a government organization called Medicare. That is why people often donate their older devices. The device donated to Samin was an older model—but exactly the same as what she had before. I offered to pay for postage fees to the kind donor, but she insisted that she would pay for it herself. The device was sent out to Soheila Naderi, the friend who had introduced Samin to me. She lived close to Samin’s village and had better access to her than me. Soheila also has a son with cochlear implants. She is a dear soul who helps

and informs families of children with hearing loss on her social media page. The device arrived! Samin’s mom was informed, and Soheila took Samin and her mother to their local audiologist. The audiologist asked, “Samin, can you hear me?” and she replied “Yes.” Soheila recorded it all using her phone and sent the videos to me. We were all overcome by emotion. I still keep in touch with Samin’s mom to ask how Samin is doing. Samin is attending rehabilitation classes and mainstream school and her future looks bright. I aspire to create an organization in Iran which focuses on donating used hearing devices—such as hearing aids and cochlear implant speech processors, and spare parts such as batteries—to families who need them. Who knows, maybe we’ll call it “The Samin Foundation.” Samin is an Arabic word that means “precious,” and not only is everyone in this story precious to me, but so is being able to fully hear.

Sahar Reiazi (near left) appeared on the cover of the Spring 2021 issue, at hhf.org/magazine. Hiroko’s story is the cover story of this issue.

Share your story: Tell us your hearing loss journey at editor@hhf.org.

Support our research: hhf.org/donate.

a publication of hearing health foundation

summer 2022

29

research