MODERN FARMER

More e t thhaan n a f fad:

Spraayiinng g c crroopps s w with h droonees s t taakkinng g o off f

More e t thhaan n a f fad:

Spraayiinng g c crroopps s w with h droonees s t taakkinng g o off f

By Dave Dawson ASSISTANT EDITOR

ARENZVILLE — If you’re driving in rural Cass County and see a lowflying drone that appears to have sprung a leak, look for a young man standingontopofatrailerwithacontroller.

Chances are you’ll see Isaac Strubbe,whoattheageof20hasbeen operating his own business, Strubbe Drone Spraying LLC, for the past couple of years. Besides running a fully licensed drone application service,heisadealerfordronemanufacturer DJI and offers after-sales support.

Strubbe grew up on a crop farm that is roughly midway between Arenzville and Beardstown. He graduated from Triopia High School and

went to Lincoln Land Community College, where he earned an associate’s degree in precision ag technology.

“I was looking for something to do to bring back to the farm and have a way to earn extra income so I could stay with farming,” Strubbe said.

The way forward appeared when he was a freshman at LLCC and attended the 2022 MAGIE show near Bloomington, which is put on by the Illinois Fertilizer & Chemical Association to show off innovations in applying agrichemicals.

Crop spraying is the process of applying insecticides, pesticides, fungicidesandotherpreventivetreatments to crops. Often referred to as crop dusting,theprocessisusedtoprotect large areas of crops from weeds, fun-

Drones continues on A3

Isaac Strubbe, owner of Strubbe Drone Spraying, based between Arenzville and Beardstown, operates one of his crop-spraying drones from atop his customized drone trailer.

Saturday, October 26, 2024

Cover Story: Spraying crops with drones taking off.....2 Small, local farms find power in new alliance......................5

How agriculture brought one couple closer.........................7

Mapping the future of agriculture..........16

Hydroponic grower opens second Illinois greenhouse.............16 Lawmakers propose 45Z extension, limiting to US feedstocks...............18

Everyday items are byproducts of farmers’ work. 8 Farmers continue to dream big with small budget............9 Dairy farms are disappearing...........12 ‘Short corn’ could replace towering cornfields................13 Cities using sheep to graze in urban landscapes..............14 Wild ginseng declining from public lands. 15 US hog inventory on rise; margins remain tight..........................15

From page A2

gus, bugs and pests.

“They were doing demos on spray drones,” Strubbe said. “ThatwaswhereIsawit first.Iwasblownaway.I wasalwaysinterestedin the technology. I hadn’t flown drones before — at least none that were worth more than $100. But that was it. I knew that was something I wanted to do.”

Strubbe attend the show in August 2022 and, by October, he was in business.

Fall is his busiest season, but he helps out as much as he can with harvest on the farm operated by his father, Kirk Strubbe.

“I enjoy farming with my family,” Strubbe

said. “We raise corn and beans, occasionally wheat.IhelpwheneverI can. Right now, I am putting the drone business first and growing that, but I definitely want to keep farming.”

Before being able to spray, Strubbe had to obtain two certificates from the Federal Aviation Administration. One was a Part 107 Certificate to fly a drone, and the other was a Part 137 Certificate to apply pesticides using drones. He also needed an aerial applicators license from the state of Illinois.

Strubbe uses an app on his phone to map the fields,lookingforthings such as power lines and fence lines. Once he has the map finished, he downloads it to his con-

troller, which features a 7-inch screen.

He punches in the height at which the drone will fly, which is no more than 400 feet, according to FAA regulations; the swath width; droplet size; and speed. From there, it will generate flight lines. The drone is set to movetotheclosestpoint andstartspraying.Once its load is empty, it returns to the trailer to repeat the process.

After seeding is complete in late spring, Strubbe will spray wheat with fungicide and alfalfa and cover crops with insecticide. The prime spraying times for fungicide on corn and beans takes place in July and early August. This fall, he has been busy spraying herDrones continues on A4

From page A3

bicide, including at small ponds.

The drone carries a 10.5-gallon tank and can spray for about 10 minutes before it needs to return for more chemicals andafreshlychargedbattery. Working solo, Strubbe can cover an 80acre field in about an hour. If his occasional helper, Connor Musch, is around, they can cover 160acreswithtwodrones in an hour.

“We can have two drones running off one trailer,” Strubbe said. “We both operate at once and split the field. One person can keep spraying whiletheotherisrefilling and switching batteries.” It takes quite a bit of power to charge the batteries quickly, which is why he has 10,000-watt chargers on the trailer. There also is an electric pump running off a generator to fill the liquid he is spraying at the time.

Musch now is back at the University of Illinois for school, but Strubbe is planning to train his youngerbrothertoassist, particularly in the area of service and repair.

Spraying isn’t the only service Strubbe offers to farmers. He also has a camera drone.

“I use it to take photos for people or help them if

their cows get out,” he said. “I don’t have a thermal drone, but I am looking to get one of them because it would be good to help measure crop health.”

Drone technology for spraying chemicals is relatively new but Strubbe believes the various methods of crop spraying including planes, helicopters and on the ground — can coexist, he said.

More than 120,000 drones were used in 2021 to spray chemicals on more than 175.5 million acres of farmland across the country, when there were more than 200,000

agricultural-drone pilots, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Drones can do things plans and helicopters can’t,” Strubbe said. “They don’t want to go near tree lines and power lines and other obstacles. One of the major benefits with the drone is how precise it can be. I don’t have to pull up at the end ofthefield,Icansprayall the way to the fence line.

“It also provides a more consistent coverage pattern because of the consistent height. I don’t want to bash the othermethods;thereisa place for all of them.”

A drone doesn’t only save time, Strubbe said,

Isaac Strubbe, owner of Strubbe Drone Spraying, basaed between Arenzville and Beardstown, pours chemicals into the tank on one of his crop-spraying drones.

but eliminates the need todriveoutintothefield to spot spray or wait for the weather to be ideal.

“It doesn’t matter if the fields are wet,” he said. “A drone can get in andspraywhereground rigs wouldn’t be able to get to. Also, it’s not knockingoveranyofthe crop or causing corn ear damage.

“I think drones are going to continue to

grow fast. I’d love to expand my fleet and crews and cover more acreage and help people get into the industry. I want to grow in that aspect and bring on more workers and pilots.

“I’m looking at it as a career, not a fad. Drones are here to stay; this is a long-term thing. Manufacturers will continue to make bigger and better models.”

By Angela Bauer LIFESTYLES EDITOR

When Clint Bland walked away from his job as senior transportation manager for Dot Foods in Mount Sterling to start a small, family farm that’s organic in all ways but officially, he wasn’texpectingthetwo parts of his life to connect again.

Certainly not so soon.

But that’s exactly what happened when Bland and eight other farms in the region began working together to form The Farms of Illinois, an alliance aimed at helping smaller farms find outlets for their products while giving their customers — whetherindividualstrying to feed their family or institutions trying to feed their clients — easier access to farm-fresh foods.

“It started because we started selling to food banks,” Bland said. “Food banks got grants specifically to purchase from local farms. But therewasalotofchaos.”

While the food banks were eager for the opportunity, a lack of staff created unexpected issues, Bland said.

“We know there is more of a push to do locally sourced foods by institutions — think school districts, hospitals, prisons sometimes,” he said. “But most of these institutions don’t have the staff and manpower to organize with 20 or 30 different farms.”

Similarly, no one small farm can afford the infrastructure —

Along with the eggs, the alliance was delivering milk, and both were products of alliance farms.

from storage space to refrigerated trucks — necessarytosupplysuchinstitutions, he said.

“They would have to charge such a high price for the food that no one could afford it,” Bland said. “The only way … is to have all the farms come together to make that happen.”

Now Bland is at the forefront of The Farms of Illinois, an alliance of nine farms around central Illinois. Their goal?

To provide a “reliable source of nutrientdense, chemical-free food” in a one-stop shop that delivers.

“We tried to jump in there and figure out” someofthechaos,Bland said. “My background is in supply-chain management —16 years with Dot Foods — so I’m trying to help solve some of

these issues.

“It’s always been a labor of love, growing and producing.Ididn’tthink I would utilize my experience and create a local distribution company specifically for local food.Butyouseeaproblem, you try to solve it,” Bland said.

The alliance has a website,thefarmsil.com, through which customers — whether large institutions or individuals can place an order for items ranging from milk, eggs and cheese to produce and various meats.

Orders must be placed by 5 p.m. Sunday. By 5:30 p.m. Sunday, Bland is emailing the various farms with a grocery list of his own. The farms then bring their requested prod-

uctstoTheFarmsofIllinois headquarters — currently a garage at Bland Family Farms but soon to be a larger space designed for the purpose — on Monday, after which it is packed and delivered to customers’ door.

None of the farms is officially certified organic, which Bland has described as a long, expensive process, but all of them follow the same practices.

“We want to make sure we’re taking good care of the animals,” Bland said, noting chickens are raised on pastures and feed nonGMO grain, produce is raised without chemicals and pest control is organic.

The Farms of Illinois is an alliance of nine farms around central Illinois. They include:

• Abundant Pastures in Claremont,

• Bland Family Farm in Jacksonville,

• Buckhorn Dairy in Mount Sterling,

• Heirloom Haus in Pawnee,

• Itty Bitty Micro Farm in Springfield,

price and it’s delivered to your door.

“We try to be a bit more competitive (on produce). Our lettuce is more expensive, but what you’re getting is cut on Monday and delivered to your door on Tuesday, less than 24 hours later.”

• Lemay Mushroom Operation in Springfield,

• Mueller Family Farm in Bluffs,

• Oak Tree Organics in Ashland, and

• Twin Willow Farms in Roodhouse.

They’re still doing farmers markets, which is a great outlet but pretty much ensures you’re working six days a week. You’re harvesting all day Friday and, Saturday, you’re at the market. And a lot of farms are doing two or three (markets) a week.”

He reached out earlier this year to see if we’d be interested in offering some of the stuff he didn’t.”

Meyer was happy to oblige.

While the alliance is just getting started, “we do appreciate access to other wholesale and individual customers that might be outside our normal service region,” he said. “We really appreciate that it offers some allocation and distribution services. I don’t have time to be on the road (making deliveries). It’s expanded our reach.”

Meyer also appreciated the freedom he’s given to make his own choices for his farm.

Farmers markets also come with some risks the alliance doesn’t.

Prices are a bit higher andlikelytobefeltifone is shopping for an entire week’s groceries. For example, a recent price comparison showed a dozen eggs selling for $3.26 at Walmart, compared to $5 via The Farms of Illinois. Shredded mozzarella ranged in price from $4.22 to $5.64 a pound at Walmart, compared to $8.50 a pound via The Farms of Illinois.

Angela Bauer/Journal-Courier

Jose Moreno Campos wheels crates full of milk to a waiting trailer ahead of delivery to a St. Louis food bank. The milk came from one of nine farms that make up The Farms of Illinois alliance.

er the source, Bland said.

Still, they’re not too far off grocery store prices when you consid-

“It’s going to be fairly similar to what you’d find at a farmers market,” he said. “The same

That can make a difference in shelf life, too, which can help make up some of the difference in price, said Michael Meyer of Mueller Family Farm, which offers a range of produce but specializes in lettuce.

“Cut and fresh and storedatpropertemperatures,lettucecanlastat least two weeks,” Meyer said. “We try to cut it as close to the time when we’re going to box it. A lot of people who come down to the markets understand that and appreciate the value. If you’re busy but willing to pay a tiny bit more, you can get that stuff delivered right to your door.”

Alliance farms have some overlap in what they offer, which helps to ensure a reliable productsource.Thegoal eventually is to have from 20 to 30 farms in the alliance, to further ensure continuity.

“We still run out of stuff,” Bland said. “Each farm is different in their size and what they can do. We’re not the only avenue for these farms.

“They’re harvesting all the stuff and hoping it doesn’t rain because then you’re going to go home with half your stuff,” Bland said. With the alliance, “you cut to demand and there’s zero waste of food.”

It also improves the farms’ bottom lines. As does sharing farmers’ individual strengths.

“I’m comfortable (working with) groceries because of my time with Dot,” Bland said. “I’m not comfortable with restaurants. But Michael Meyer (of Mueller Family Farm) is comfortable with restaurants. He knows how to talk to chefs.”

Meyer and Bland got to know one another through attending the same farmers markets, including the Jacksonvillefarmersmarketand the Old Capitol Farmers Market in Springfield.

“He found certain crops that worked best for him,” Meyer said of Bland. “We have stuff that works best for us.

“We have the freedom to offer whatever productwewantatthetime,” he said. “... We kind of let (Bland) know what we think we’re going to have for the coming week and he’s able to offer that in his weekly email and online.”

Along with selling to grocery stores and other wholesale accounts, the alliance also extends its farmers’ selling season, Meyer said.

“We do continue to have products after (farmers) market season,” he said, noting his farm grows lettuce into November and sometimes December, even though farmers markets tendtoshutdowninOctober.

“It seems like falls are increasingly warm and linger,” Meyer said. “It reallydoesn’tdoyouany goodifthere’snomarket totakeit.Whenthemarket season’s over, if you’ve already been a customer of (Mueller Family Farm) and are wondering how to continue getting our product, (the alliance) is a really good way.”

By Ben Singson REPORTER

— Farming

can be an arduous professioneveninthebestof times. It requires long hours, hefty capital, exhausting labor and constant maintenance of both crops and equipment.

One Scott County couple has found it’s much more manageable when youhaveyoursignificant other by your side.

Chris and Libby Nobis have been married for nearly 23 years and have spent their whole marriedlifeworkingtogether ontheirfarm.Neitherisa full-time farmer. Chris Nobis is a manager for BurrusSeed,whileLibby Nobisissupervisorofhyperbaric medicine for Jacksonville Memorial Hospital and an emergencymedicaltechnician for Winchester EMS.

In their free time, though, they grow corn, soybeans and alfalfa and raisecattleontheirfarm, which is about 15 miles west of Jacksonville.

Libby Nobis didn’t expect to be involved with agriculture in her married life, she said. By her own admission, she is a “city girl” from Jacksonville and only wanted to get married and have children as an adult.

While she did end up doing both of those things, she also has learnedtolovethefieldin the years she has been working alongside her husband.

“I kind of fell into it and love it,” Libby Nobis said.

The two usually work

together to do whatever needs doing around the farm, whether it’s working with cattle or moving and maintaining equipment, though Libby Nobis said the latter usually is her husband’s domain.

Having his spouse nexttohimmakesiteasierforChrisNobistokeep her informed about what needs to be done on the farm while also ensuring she is involved in farming.

“It makes me feel good to know that this is what she wants to do, too, alongsideofme,”hesaid.

“I’m not just dragging her along because it’s something I’m passionate about. She’s very passionate about it, too.”

No couple agrees on everything, though, and theNobisesarenoexception. Both said Chris Nobis is something of a perfectionist when it comes totasksaroundthefarm, while Libby Nobis is more willing to take shortcuts to get the job done faster.

“She cuts corners and I’m more old-fashioned,” Chris Nobis said. “I like todothingsrightthefirst time and not have to cut corners and go back and do things a second and third time.”

“And I’m a ‘hurry up andgetitdone’(person),” Libby Nobis said.

Patience, therefore, is an important virtue to haveforanycoupleswho farm together, the Nobises said. Preparation is another quality couples should have, because agriculture means dealing with many unexpected issues, Libby Nobis said.

“Farming throws a lot

of curveballs at you that you’vegottobewillingto roll with,” she said.

If there is one thing that more than two decadesoffarmingtogether has taught them, it is “how to push each other’s buttons,” Libby Nobis said. That knowledge helps them to stay calm when they encounter issues while farming together.

“We don’t want to yell at each other,” she said. “When you have frustrations — low grain prices and things like that — we’re each other’s cheerleaders and why we’re

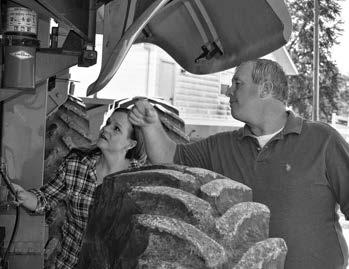

Chris and Libby Nobis look under the hood of a combine on their farm. The Exeter couple says farming together has helped bring them closer together during more than two decades of marriage.

By Samantha McDaniel-Ogletree

Mostoftheitemssoldin stores,atfarmersmarkets and in restaurants are made from something grown by farmers.

Vegetable oil, soy products and animal feed are among items commonly thought of when a person thinks of the uses for grain. But there are many items made from corn or soybeans that aren’t intended to be eaten.

“‘Food, fuel and fiber’ is the big statement when it comes to what farmers grow,” said Aaron Dufelmeier, director of the University of Illinois Exten-

sion Office in Morgan County. “The purpose behind most of what a farmer grows is the well-being of people.”

While a majority of corn and soybeans is used in animal feed, it also can be used in bio-fuels. For example, corn is used for ethanol production, while soybeansoftenareusedto manufacture biodiesel.

“There are a lot of things that we don’t often thinkaboutwhenitcomes to products made from corn and soybeans,” Dufelmeier said.

Farmers have little control over what happens to their crop once it is sold.

Once at the elevator, it is taken elsewhere by truck,

rail or river, to be used as the buyer wishes. When farmers bring their corn to Scoular Grain, just east of Waverly, it goes through a process before it is loaded onto a train and taken to places such as west Texas

andMexico,whereitoften is used as cattle feed.

Marcus Christensen, generalmanagerforScoularGrain,saidyear-round — but especially during the harvest season — truckloads of corn are weighed, separated and

transported to different locationsforuseprimarily in animal feed or ethanol, Christensen said.

“The number of trucks we see daily varies depending on the time,” Christensen said. “Harvest is obviously a busier time at grain bins.”

Corn in the grain bins canbestoredforaslittleas adayoraslongasacouple of years, depending on market demand.

loaded onto trains at their primary locations. At satellite locations, soybeans go through the same process before being loaded onto trucks for transportation.

When a truck brings a load to the elevator, the loaded truck is weighed, the product is dumped, and the truck is weighed again to ascertain the product’s weight. From there, corn is segregated basedonqualityanddried to meet rail lines’ specifications before being stored or loaded.

Thecompanyisresponsible for loading approximately 450,000 bushels of corn into a 110-car train unit, after which it will be

Soybeans also are transported elsewhere. From the elevator, soybeans are loaded onto trucks. Most then are takentoSt.Louis,wherethey are loaded onto barges on the Mississippi River and taken to New Orleans for saletonationalorinternational buyers.

Some farmers adapt their crop to address a specific need, such as a certainvarietyofcornthat meets Anheuser-Busch’s particular specifications, Dufelmeier said .

“Some companies advertise for certain productsandfarmerscancater to them, so they’ll have a bit more control there,” Dufelmeier said. “But, no matter what, we as consumers, everything we touch,use,pickupisabyproduct of something a farmer is growing.”

Here are some products you may never have realized are made from grain grown in the fields of west-central Illinois.

Products made from corn include toilet paper (corn is a surprisingly soft and absorbent material), drywall (cornstarch’s binding properties are used in many construction-grade materials), toothpaste, crayons, diapers, spark plugs, hand soap, and aspirin.

Products made from soybean include artificial fire logs, candles, carpet backing, cleaning products, printer inks and toners, pet food, synthetic fabrics, and crib mattresses.

By Rhiannon Branch FARMWEEK

High interest rates, elevated input costs and falling commodity prices create barriers for farmers to adopt innovation, but some Illinois producers said you can still dream big with a small budget.

McLean County farmer Reid Thompson suggested the phrase “tight margins” is an understatement this year.

“We started looking at 2025numbersandthereis some margin in corn and zero to negative margin for soybeans depending on rent costs,” he said. “Andthatjustcoversoperating costs and overhead, not debt service.”

Thompson said while

the budget is almost nonexistent, he still looks for ways to innovate.

“Our thought process goingintonextyearisthat we’re not going to rule anything out, but any technology we add has to also accompany an efficiency savings,” he said.

“Maybe we don’t reduce the cost-per-acre number in inputs, but we can be moreefficientwithournitrogen and our timing.”

Thompson said there is always room for improvement, but with smaller margins, farmers must look at where they can spend a little bit of money and get a large return.

“Instead of a spend $1 andget$2back,wherecan I spend $1 and get $10 back?” he asked. “That’s

themindsetyouhavetogo into this year with. You can’t stop (innovating) because once you stop, the gaptocatchbackupisgoingtocostyouevenmore.”

Corn and soybean farmer Scott Harris has alsocontinuedtoinnovate despite tighter margins.

The Johnson County farmer told FarmWeek rain early in the growing season hindered yields this year, so Harris is thinking of ways to minimizethatimpactinthefuture.

“We ask ourselves is there something we can do to benefit the crop in a way that would produce more yield?” he said. “We need all the yield we can get when we’re dealing with prices as low as they are.”

The Harris family added technology to their planters this year and are considering the purchase of a spray drone.

“Anything that makes the planting or chemical applications faster we’re always interested in,” Harrissaid.“Aslongaswe can find out for ourselves that it’s worth the money that we’re going to spend on it.”

Harris said while farmers often must rein in big dreams during tight margins, innovation is still possible if you manage your budget correctly.

“If you’re not trying to improve your innovation, bring something new to your operation, look into

By Elizabeth Eckelkamp THE CONVERSATION

MiltonOrrlookedacross therollinghillsinnortheast Tennessee.

“I remember when we had over 1,000 dairy farms inthiscounty.Nowwehave less than 40,” Orr, an agriculture adviser for Greene County, Tennessee, said with a tinge of sadness.

That was six years ago. Today, only 14 dairy farms remain in the county, and there are only 125 dairy farms in all of Tennessee.

Across the country, the dairy industry is seeing the same trend: In 1970, over 648,000 U.S. dairy farms milked cattle.

By 2022, only 24,470 dairy farms were in operation.

While the number of dairy farms has fallen, the average herd size – the number of cows per farm –has been rising. Today, more than 60% of all milk productionoccursonfarms withmorethan2,500cows.

This massive consolidationindairyfarminghasan impact on rural communities. It also makes it more difficult for consumers to know where their food comes from and how it’s produced.

As a dairy specialist at the University of Tennessee, I’m constantly asked: Why are dairies going out of business? Well, like our friends’ Facebook relationship status, it’s complicated.

Thebiggestcomplication

is how dairy farmers are paid for the products they produce.

In 1937, the Federal Milk Marketing Orders were established under the Agricultural Marketing Agreement Act. The purpose of these orders was to set a monthly, uniform minimum price for milk based onitsenduseandtoensure that farmers were paid accurately and in a timely manner.

Farmerswerepaidbased on how the milk they harvested was used, and that’s still how it works today. Does it become bottled milk? That’s Class 1 price. Yogurt?Class2price.Cheddar cheese? Class 3 price. Butter or powdered dry milk?Class4.Traditionally, Class 1 receives the highest price.

Thereare11milkmarketing orderss that divide up the country. The Florida, SoutheastandAppalachian milk marketing orderss focus heavily on Class 1, or bottled, milk. The other milk marketing orderss, suchasUpperMidwestand Pacific Northwest, have more manufactured productssuchascheeseandbutter.

For the past several decades, farmers have generally received the minimum price. Improvements in milk quality, milk production, transportation, refrigeration and processing all led to greater quantities of milk, greater shelf life and greater access to products across the U.S. Growing supply reduced competition among processing plants and reduced overall prices.

Improvements in milk quality, milk production, transportation, refrigeration and processing all led to greater quantities of milk, greater shelf life and greater access to products across the U.S. Growing supply reduced competition among processing plants and reduced overall prices.

Along with these improvements in production came increased costs of production, such as cattle feed, farm labor, veterinary care, fuel and equipment costs.

Researchers at the UniversityofTennesseein2022 compared the price received for milk across regions against the primary

Dairy continues on A18

By Scott McFetridge ASSOCIATED PRESS

Taking a late-summer country drive in the Midwest means venturing into the corn zone, snaking between12-foot-tallgreen, leafy walls that seem to block out nearly everything other than the sun and an occasional water tower.

The skyscraper-like corn is a part of rural America as much as cavernous red barns and placid cows.

But soon, that towering cornmightbecomeaminiatureofitsformerself,replaced by stalks only half as tall as the green giants thathavedominatedfields for so long.

“Asyoudriveacrossthe Midwest, maybe in the nextseven,eight,10years, you’re going to see a lot of this out there,” said Cameron Sorgenfrey, a farmer who has been growing newly developed short corn for several years, sometimes prompting puzzledlooksfromneighboring farmers. “I think this is going to change agriculture in the Midwest.”

The short corn developed by Bayer Crop Science is being tested on about 30,000 acres in the Midwestwiththepromise of offering farmers a variety that can withstand powerfulwindstormsthat could become more frequent due to climate change.Thecorn’ssmaller stature and sturdier base enable it to withstand winds of up to 50 mph — researchers hover over fields with a helicopter to see how the plants handle the wind.

The smaller plants also let farmers plant at greater density, so they can grow more corn on the same amount of land, in-

creasing their profits. That is especially helpful as farmers have endured severalyearsoflowprices thatareforecasttocontinue.

The smaller stalks could also lead to less water use at a time of growing drought concerns.

U.S. farmers grow corn on about 90 million acres each year, usually making itthenation’slargestcrop, soit’shardtooverstatethe importance of a potential large-scale shift to smaller-stature corn, said Dior Kelley, an assistant professor at Iowa State Universitywhoisresearching different paths for growing shorter corn. Last year, U.S. farmers grew more than 400 tons of corn, most of which was used for animal feed, the fuel additive ethanol, or exported to other countries.

“It is huge. It’s a big, fundamentalshift,”Kelley said.

Researchers have long focused on developing plantsthatcouldgrowthe most corn but recently there has been equal emphasis on other traits, such as making the plant

more drought-tolerant or able to withstand high temperatures. Although there already were efforts to grow shorter corn, the demand for innovations by private companies such as Bayer and academicscientistssoaredafter an intense windstorm called a derecho — plowed through the Midwest in August 2020.

The storm killed four

people and caused $11 billion in damage, with the greatest destruction in a widestripofeasternIowa, wherewindsexceeded100 mph. In cities such as Cedar Rapids, the wind toppled thousands of trees but the damage to a corn croponlyweeksfromharvest was especially stunning.

“It looked like someone had come through with a

machete and cut all of our corn down,” Kelley said.

Or as Sorgenfrey, the farmer who endured the derecho put it, “Most of my corn looked like it had been steamrolled.”

Although Kelley is excitedaboutthepotentialof short corn, she said farmers need to be aware that cobs that grow closer to thesoilcouldbemorevulnerable to diseases or

mold. Short plants also could be susceptible to a problem called lodging, whenthecorntiltsoveraftersomethinglikeaheavy rainandthengrowsalong the ground, Kelley said.

Brian Leake, a Bayer spokesman, said the company has been developing short corn for more than 20 years. Other companies such as Stine Seed and Corteva also have beenworkingforadecade or longer to offer shortcorn varieties.

While the big goal has been developing corn that can withstand high winds, researchers also note that a shorter stalk makes it easier for farmers to get into fields with equipment for tasks such as spreading fungicide or seeding the ground with a future cover crop. Bayer expects to ramp up its production in 2027, and Leake said he hopes that by later in this decade, farmers will be growingshortcorneverywhere.

“We see the opportunity of this being the new normal across both the U.S.andotherpartsofthe world,” he said.

By Kristin M. Hall ASSOCIATED PRESS

Along the Cumberland River just north of downtown Nashville, Tennessee,touristsonpartypontoons float past the recognizable skyline, but they also can see something a little less expected: hundredsofsheepnibblingon the grass along the riverbank.

The urban sheepherder who manages this flock, Zach Richardson, said sometimes the tourist boats will go out of their waytolettheirpassengers get a closer glimpse of the Nashville Chew Crew grazing a few hundred yards away from densely populated residential and commercial buildings.

The joy people get from watching sheep graze is partly why they are becoming trendy workers in some urban areas.

“Everybody that comes out here and experiences the sheep, they enjoy it more than they would someone on a zero-turn moweroraguywithaleaf blower or a weed eater,” Richardson said.

Using sheep for pre-

scribed grazing is not a new landscaping method, but more urban communities are opting for it to handle land management concerns such as invasive species, wildfire risks, protection of native vegetationandanimalhabitats and maintaining historic sites.

Nashville’s parks department hired the Chew Crewin2017tohelpmaintain Fort Negley, a Civil War-era Union fortification that had weeds growing between and along its stones that lawnmowers could easily chip. Sheep now graze about 150 acres of city property annually, including in the historic Nashville City Cemetery.

“It is a more environmentally sustainable way to care for the greenspace and oftentimes is cheaper than doing it with handheldequipmentandstaff,” said Jim Hester, assistant director of Metro Nashville Parks.

Livingamongthesheep —andoftenblendingin— are the Chew Crew’s livestockguardiandogs,Anatolian shepherds, who are born and stay with them 24/7tokeepawaynosyin-

George

Walker IV/AP

Zach Richardson, owner of the Nashville Chew Crew, looks over his flock of sheep along the Cumberland River bank. The sheep are used to clear out overgrown weeds and invasive plants in the city's parks, greenways and cemeteries.

truders, both the two-legged and the four-legged kinds. The flock is comprised of hair sheep, a typeofbreedthatnaturallyshedsitshairfibersand often is used for meat.

Another important canine employee is Duggie, thebordercollie.Withonlyafewwhistlesandcommands from Richardson, Duggie can control the

whole flock when they needtobemoved,separated or loaded onto a trailer.

Across the country, another municipality also has become reliant on these hoofed nibblers.

Santa Barbara, California, has been using grazing sheep for about seven years as one way to manage land buffers that can slow or halt the spread of wildfires.

“The community loves thegrazersandit’skindof a great way of community engagement,” said Monique O’Conner, open spaceplannerforthecity’s parks and recreation. “It’s kindofanewshinywayof land management.”

The grazed areas can change how fire moves, said Mark vonTillow, the wildland specialist for the Santa Barbara City Fire Department.

“So if a fire is coming down the hill and it’s going through a full brush field,andthenallofasudden it hits grazed area that’s sort of broken up

Richardson, the owner of Chew Crew who at the time was a UGA student studying landscape architecture, was inspired to create his own goat grazing business. The goats became the most popular four-legged creatures on campus, he said.

“Whatwasfunandless expected was kind of the side projects and a life of its own developed around the Chew Crew,” Kirsche said.“Wehadartstudents doing time-lapse photography, documenting changes over time. One point we had a student dressed as a goat playing goat songs on the guitar and other students serving goat cheese and goat ice cream.”

vegetation, the fire behavior reacts drastically and dropstotheground,”vonTillow said. “That gives firefighters a chance to attack the fire.”

Even some universities have tried out herds of goats and sheep on campus property. In 2010, the University of Georgia had a privet problem that was overtakingasectionofthe campus not used by studentsorstaffandpushing out native plants, said Kevin Kirsche, the school’s director of sustainability.

Rather than using chemicals or mowers, Kirsche said they hired JennifChandlertosendin a herd of goats to strip the bark off the privet, stomp on roots and defoliate the branches.

“Bringing the goats to the site was an alternative means of removing invasive plants in a way that was nontoxic to the environment and friendly to people,” Kirsche said.

Around the same time,

Richardson, who moved his company to Nashville after finishing his degree, now prefers sheep over goats. Sheep are more flock-oriented and aren’t inclined to climb and explore as much as goats.

“I’ll never own another goat,” he admitted. “They arelikelittleHoudinis.It’s like trying to fence in water.”

But sheep are not a silver bullet solution for all cities and their lands, according to O’Conner. “We wanttoeducatethepublic on why we’re choosing to graze where we’re grazing,” she said.

Not every urban site is ideal. Chandler owns City Sheep and Goat in Colbert, Georgia, about 12 miles northeast of UGA’s campus in Athens, where her sheep graze on mostly residential properties and community projects such asClydeShepherdNature Preserve in North Decatur,justoutsideofAtlanta. In 2015, some of her sheep were attacked and

By Justine Law THE CONVERSATION

Many people know ginsengasaningredientinvitamin supplements or herbal tea. That ginseng is grown commercially on farms in Wisconsin and Ontario, Canada.

In contrast, wild American ginseng is an understoryplantthatcanlivefor decadesintheforestsofthe Appalachian Mountains. The plant’s taproot grows throughoutitslifeandsells forhundredsofdollarsper pound, primarily to East Asian customers who consume it for health reasons.

Because it’s such a valuable medicinal plant, harvestingginsenghashelped families in mountainous

regions of states such as Kentucky, West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina andOhioweathereconomic ups and downs since the late1700s.

Most harvesting takes place in Appalachia’s longenduring forest commons – forests across the region thathistoricallyweremanagedandusedbylocalresidents. Many people in Appalachia still believe that, at least in practice, forests shouldbecommonproperty, even as large swaths of the region’s forests have been placed under state or federal ownership over the past century.

Recently,however,ithas become harder for diggers to harvest ginseng from public lands, such as na-

By Rhiannon Branch FARMWEEK

The latest quarterly hogsandpigsreportfrom USDA showed an increase in U.S. numbers.

Inventory as of Sept. 1 waspeggedat76.5million head, up slightly from September 2023 and up 2%fromJune1.InIllinois, all hogs and pigs totaled 5.6millionhead,down3% sinceJunebutup2%compared to last year.

Duringawebinarhosted by the National Pork Board after the report was released Sept. 26, Brett Stuart with Global AgriTrends said there is potential for swine numbers to continue to rise.

“The WASDE (World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates) report shows 2024 pork production up 2.7%,” he said.“Ifwewereup1.1%in

tional forests. Those who flout regulations are receiving steeper fines and, sometimes, prison sentences.

This is because ginseng populations are hovering atafractionoftheirhistorical levels. Government agencies, scholars and the media have asserted that contemporary diggers have over-harvested wild ginseng from Appalachia’s forests.

I’m an environmental geographer who studies rural livelihoods and conservation in North American forests. As I see it, large-scale threats to ginseng,includingminingand climate change, are bigger concerns than small-scale harvesting by negligent

diggers.Ibelievemanydiggers can be valuable conservation partners.

Ginseng was listed in AppendixIIoftheConventiononInternationalTrade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in 1975. This indicated that the plant was not threatened at the time but could become so. Today, ginseng is classified as vulnerable in13 of the19 states that allow its harvest and sale, subjecttostateregulations.

Some of those regulations include:

– A harvest season from Sept.1through late fall.

– Harvesting bans on certain types of land, such as state parks and wildlife refuges.

– A requirement that

harvested plants must have three leaves, or “prongs,” a proxy for the plant’s age.

– A requirement that diggers plant the berries from ginseng they’ve dug at the harvest site.

Over the past decade, state and federal agencies have tightened ginseng regulationsandrampedup enforcement. These actions were spurred largely by rising ginseng prices and by evidence that ginseng was sometimes sold on black markets in exchange for illegal drugs.

In 2018, for instance, West Virginia increased fines for illegal ginseng harvestingfrom$100tobetween$500and$1,000fora first offense. That same

year, Ohio began using dogstodetectginsengheld bypeoplesuspectedofillegal digging.

States with sizable ginseng harvests often conduct undercover and sting operations to detect illegal harvesting. Some national parks and preserves even dyeorattachmicrochipsto ginsengplantstomakeillegal collection easier to spot.

Meanwhile,theU.S.Forest Service has indefinitely suspended ginseng harvesting in national forests in Kentucky, North Carolina,GeorgiaandTennessee. These closures cover over 5,000 square miles of Appalachian forestland – an arealargerthanthestateof Connecticut.

the first half, that means to get to the WASDE number,we’regoingtobe up4.3%inthesecondhalf of the year.”

Stuart said given those estimates, the hog industry could be looking at larger production going into the fourth quarter.

The September report placed breeding inventory at 6.04 million head, down 2% from last year, but up1% from the previousquarter.Thebreeding inventory in Illinois, 650,000 head, was down 20,000 from last year.

Market hog inventory (70.4 million head) was up 1% from last year and 2% from last quarter nationwide and up 2% in Illinois at 4.95 million head.

Thereportalsoshowed increases in some of the higher weight classes for market hogs.

BY MCG ONLINE

The demand for food is directly related to population growth.By2050,foodneedsare expected to double, according toastudypublishedinthejournal Agricultural Economics.

That puts increasing pressure on the agricultural sector tomeetgrowingdemand.However,manyexpertsthinktheindustry will fall short.

In addition to increased food demand, consumer habits, technology,andpoliciescontinue to force the agricultural industrytoevolve.Indeed,theagricultural sector may look very different in the future.

Social media has transformed many industries, and it can do the same for agriculture. Farming supply chains cancommunicatewithoneanotherbygettingfeedbackfrom customersinrealtimethrough social media. However, agricultural operations will have to devote teams to manage socialmediapresence,especially since misinformation is so widespread on social media. Apart from social media, local farmers may increase their efforts to utilize mobile apps and direct-to-consumer purchasing options. The global pandemic helped businesses

reimagine takeout and curbside shopping. Local farms may want to market to the home-shopping community, providing ways to deliver produce, fresh meat and poultry and other items direct to customers homes.

Thefuturemayfeatureasignificant shift in the way farms source their ingredients. Regeneration International says that regenerative agriculture can be the future. This describes farming and grazing practicesthatmayhelpreverse climate change by rebuilding soil organic matter and restor-

ing degraded soil biodiversity. Some insist that farmers who utilizeregenerativeagriculture produce food that is more sustainable and healthy. This is something eco- and healthconscious consumers can stand behind.

There’s a good chance that technology will continue to play important and growing roles in farming operations. New agricultural technologies can collect data on soil and plant health and produce results in real time. Precision farming technology can be de-

veloped to deliver integrated solutions no matter the size of the operation.

Shift in what’s grown Farmers may give more thought to sustainable products. Crops like hemp and cannabis are being utilized in new and innovative ways, and they re only the start as consumers have expanded their views on plant-based foods and products.

While there’s no way to see into the future, individuals can anticipate changes that could be in store for the agricultural sector in the decades ahead.

By Talia Soglin TRIBUNE NEWS SERVICE

Hydroponic grower BrightFarmshasopeneda new greenhouse in Yorkville as part of a nationwide expansion it says willeventuallyincreaseits growing capacity seven times over.

The greenhouse is the second in Illinois for BrightFarms, which grows leafy greens sold in grocery stores.

BrightFarms, which is headquartered in New York, opened a greenhouse in Rochelle, about 80 miles west of Chicago,

in 2016. The company has five other existing greenhouses, one each in New Hampshire, Virginia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Ohio.

The company also plans to open indoor farms in Macon, Georgia, and Lorena, Texas, with construction of those greenhouses set to near completion by the end of the year. Because they are larger and more technologicallyadvancedthanits existing indoor farms, BrightFarms says, the three new greenhouses will increase the company’s growing capacity by

seven times.

The Rochelle farm, for instance, can produce about 4 million salads a year, the company says. The Yorkville farm will produce as many as 25 million. All together, the companysays,itwilleventually be able to produce as many as 150 million poundsofleafygreensper year.

The increased efficiency of the new greenhouses, CEO Steve Platt said, comes primarily from two areas: a climate control system that keeps the greenhouse at optimal growing temperature

year-round and an automated planting system.

“No hands touch anything from seed all the waytoharvest,”Plattsaid. “It’s really advanced compared to what we started with over10 years ago.”

BrightFarms, founded in 2011, was bought by privately held conglomerate Cox Enterprises in 2021. Subsidiary Cox Farms also owns greenhouse fruit and vegetable grower Mucci Farms.

In the past, BrightFarms dabbled in vegetables — it grew tomatoes at the Rochelle facility, for instance — but has since

narroweditsfocustoleafy greens. The company also used to strike exclusive deals with grocery stores tobuildoutitsgreenhouses; it’s moved away from that model too.

“When the company was starting, I think they needed something like that,”Plattsaid.“Butnow, we’veproventhebusiness model, we’ve proven the partnership with our customers.”

The company has netted dollar sales of nearly $60 million over the last year, marking growth of about 20%, Platt said.

Overall, the packaged salad market saw more than $9 billion in sales over the last year, according to market research firm SPINS. Though growth in the industry as awholeremainedmoreor less flat, sales of packaged saladsgrownincontrolled environments—whichincludesvarioustypesofindoor farming including hydroponics—grewmore than 30% over the year.

Proponents of indoor

growing tout its climate benefits, noting that produce grown locally in greenhouses needs to be driven much shorter distances to grocery shelves than produce grown, for instance,inCaliforniaand shipped to grocery stores throughout the Midwest. IntheMidwest,Plattsaid, BrightFarms tries not to truckitsgreensmorethan four hours away from where they’re grown.

Some advocates have raised concerns about the energy usage required for indoor farming, and research about the overall climate impact of greenhouse farming is mixed. One study cited in an overview by The Washington Post found that indoor-grown tomatoes had carbon footprints six timeslargerthantheirtraditionally grown counterparts, while another paper found greenhousegrown lettuce had lower carbon impacts than lettuce grown outdoors, precisely because of the decrease in trucking miles.

From page A9

the future and be a bit more prepared, then you arefallingbehind,”Harris said.

Aspraydroneisoneinvestment that has paid off in recent years for Marion CountyfarmerAndyHeadley,whoraisescorn,soybeans and cattle with his dad and brother.

“We saved a lot of money by applying our own fungicide rather than hiring a plane, and it’s easier to do it and more timely,” he said.

He said while they generally stick to what is “tried and true” when income is down, they don’t rule out new ideas.

“You just have to watch and make sure you’re going to get a decent return on your investment if you’re going to spend money during these times.”

Thatisapointthatfifthgeneration Ogle County farmer Ryan Reeverts

considered a few weeks ago when he purchased his first piece of equipment; a 1981 International axial flow combine with 4,100 hours.

Whilethat’snotthetypical mental image of the term “innovation,” Reeverts said it was the next logical step for growth in his second year of cash renting ground on his own.

“It’s gotten to a point where I needed to justify that custom harvest paymentversustryingtopurchase my own machine to cover my own acres,” he said.

While he wanted to look for something newer with the capability to add GPS and in-cab yield monitors, he said he went in with a mindset that he can always upgrade when money allows.

“With these tighter marginsitjustgetstoaposition where we’ve got to holdoffonthoseopportunities and look for new ways to adapt and overcome,” Reeverts said.

One way he has done that is by securing an Environmental Quality IncentivesProgramcontract with USDA’s Natural ResourcesConservationService.

“That’sgoingtoprovide uswiththeabilitytoinnovate the way we rotationallygrazeourcattleonour pasture,” he said. “And that’s going to improve our harvest efficiency when it comes to running those cows on smaller tracts of land.”

Knowing that the ag economy is cyclical, Reeverts said he continues to think ahead.

“Ithinkit’simportantto always look for opportunities to innovate and change the mindset toward what we’re trying to accomplish on our operations,” he said.

This story was distributed through a cooperative project between Illinois Farm Bureau and the Illinois Press Association. For more food and farming news, visit FarmWeekNow.com.

Chris and Libby Nobis talk while putting air in a tire on a combine. The Exeter couple says farming together has helped bring them closer together during more than two decades of marriage.

From page A7

doing this.”

ChrisNobisechoedhis wife’s sentiments, saying that remembering they are working in agricultureasateamhelpsthem not to provoke one an-

other. Not being career farmers also helps, he said, because they can leave anything giving them trouble where it is and go home, knowing it stillwillbetherethenext day.

Farming has brought the two closer together and Libby Nobis contin-

ues to impress her husband each day with how far she’s come for a “city girl,” he said.

“It really helps, being there together,” Chris Nobis said. “We get to spend time with each other and, I think, every day we learn something about the other.”

From page A14

killed by dogs who got through the electric fencing while in a public park. Those kinds of incidents have been rare, according to Chandler.

The sheep need to be moved regularly because they tire of the same plants and relocating reduces the chances of a predator attack, Chandler said.

Hundreds of sheep can impact the environment by spreading seeds. The city of Santa Barbara does environment surveys before bringing in grazers sinceitcanalsoaffectbird habitats and nests.

“Throwing like 500 sheep into an area is a muchlargerimpactonthe land and those soils than our native herbivores would have,” O’Conner said.

Along the levee of the Cumberland River, the side of the greenway wheretheparkusesmowerslooksmanicuredlikea golf course. On the other side where the Chew Crew ewes are munching, an ecosystem is flourishing.

“There’s rabbits, butterflies, groundhogs, turtles, nesting birds,” Richardsonsaid.“Thelistgoes on. It’s way more diverse. Even though we’ve removedsomeofthevegetation, there’s still a habitat thatcansupportwildlife.”

Richardson checks on his flock daily, but he also often receives pictures and videos that people take of the sheep because his phone is listed on the electric fence.

“If the sheep can be a catalysttoconnectbackto nature just for a split second or spark a kid’s imagination to go down to the riverandcatchacrawdad, I think more of that is good,” Richardson said.

By Tammie Sloup FARMWEEK

A bipartisan group of lawmakers are sponsoring legislationtorestricttheeligibility of the 45Z tax credit to renewable fuels derived only from domestically sourced feedstock and extending the credit for seven years.

Thebicameralandbipartisan Farmer First Fuel IncentivesActisco-ledbyU.S. Sens. Roger Marshall, RKansas, and Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, with companion legislation introduced by U.S. Reps. Tracey Mann, R-Kansas, and Marcy Kaptur, D-Ohio. Created by the Inflation Reduction Act, the Clean Fuel Production Credit (45Z) for low carbon fuels, including sustainable avia-

From page A12

costs of production: feed andlabor.Theresultsshow why farms are struggling. From 2005 to 2020, milk sales income per 100 pounds of milk produced rangedfrom$11.54to$29.80, with an average price of $18.57.Forthatsameperiod, the total costs to produce 100 pounds of milk ranged from $11.27 to $43.88, with an average cost of $25.80. On average, that meant a single cow that produced 24,000 pounds of milk brought in about $4,457. Yet,itcost$6,192toproduce that milk, meaning a loss for the dairy farmer.

More efficient farms are able to reduce their costs of production by improving cow health, reproductive performance and feed-tomilk conversion ratios.

Larger farms or groups of farmers – cooperatives such as Dairy Farmers of America – may also be able

tionfuel(SAF),willbeineffect from 2025 to 2027, which is not enough time, lawmakers said.

Extendingthecreditto10 years would give the ethanolindustrythetimeandfinancialincentivetobuildup the infrastructure needed fortheU.S.tobelessreliant on foreign fuel, open new marketsforfarmersandincrease ethanol production acrosstheMidwest,according to a news release.

“It’s very tough in farm country with high interest rates and low commodity prices,whichisexactlywhy we can’t have a tax policy that will lower commodity pricesevenmore,”Marshall said. “While we support free trade and open markets, we do not believe foreign feedstocks should be incentivized through the

to take advantage of forward contracting on grain and future milk prices. Investments in precision technologies such as robotic milking systems, rotary parlors and wearable health and reproductive technologies can help reduce labor costs across farms.

Regardless of size, survivinginthedairyindustry takes passion, dedication and careful business management.

Some regions have had greater losses than others, which largely ties back to how farmers are paid, meaning the classes of milk,andtherisingcostsof production in their area. There are some insurance and hedging programs that canhelpfarmersoffsethigh costsofproductionorunexpected drops in price. If farmers take advantage of them, data shows they can functions as a safety net, buttheydon’tfixtheunderlying problem of costs exceeding income.

hard-earned dollars of U.S. taxpayers to the detriment of American farmers.”

Illinois Farm Bureau President Brian Duncan submitted comments to USDA in July stressing the 45Z tax credit should benefitonlyproducersmanufacturing biofuels from feedstocks sourced from the U.S. The department received 260 comments.

“The use of low-carbon commodities provides new market opportunities for U.S. farmers. However, without the proper framework, farmers may face unnecessary barriers limiting access to these markets,” Duncan wrote. “It is imperative that the program design and structure for lowcarbon feedstocks is done correctly the first time so therewillbeoptimalpartic-

Passing the torch

Why do some dairy farmersstillpersist,despite low milk prices and high costs of production?

For many farmers, the answer is because it is a familybusinessandapart of their heritage. Ninetyseven percent of U.S. dairy farms are family owned and operated. Some have grown large to survive. For many others, transitioning to the next generation is a major hurdle.

The average age of all farmers in the 2022 Census of Agriculture was 58.1.Only9%wereconsidered“youngfarmers,”age 34 or younger. These trendsarealsoreflectedin the dairy world. Yet, only 53% of all producers said they were actively engaged in estate or succession planning, meaning theyhadatleastidentified a successor.

Helping farms thrive

In theory, buying more

ipationfromfarmersacross the country.”

Illinois’twosenatorsand four representatives, including Nikki Budzinski, D-Springfield; Darin LaHood, R-Dunlap; Eric Sorenson,D-Moline;andRobin Kelly, D-Matteson, previously signed onto bipartisan letters in support of limitingthecredittodomestically produced renewable fuels derived from domestically produced feedstocks.

Failuretoproperlystructure the feedstock sustainability criteria associated with 45Z credit will incentivize the use of foreign feedstocks over those from U.S. suppliers, contrary to the intent of Congress, the senators’ July 30 letter to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated.

Commodity group lead-

dairy would drive up the marketvalueofthoseproductsandinfluencetheprice producers receive for their milk. Society has actually done that. Dairy consumption has never been higher. But the way people consume dairy has changed.

Americanseatalot,andI meanalot,ofcheese.Wealso consume a good amount of ice cream, yogurt and butter, but not as much milk as we used to.

Does this mean the U.S. shouldchangethewaymilk is priced? Maybe.

The milk marketing orders is currently undergoingreform,whichmayhelp stem the tide of dairy farmers exiting. The reform focuses on being more reflective of modern cows’ ability to produce greater fat and protein amounts; updating thecostsupportprocessors receive for cheese, butter, nonfat dry milk and dried whey; and updating the way Class 1 is valued, among other changes. In theory, these changes

ers applauded the recently introduced legislation.

“Corn growers are making every effort to help the airline industry lower its greenhouse gas emissions throughtheuseofcornethanol,”saidMinnesotafarmerandNationalCornGrowers Association President Harold Wolle. “We are deeply appreciative of these leaders for introducing legislation that establishes requirementsforthetaxcredit that will level the playing field for America’s corn growers.”

AmericanSoybeanAssociationPresidentJoshGackle said farmers who grow thecropsutilizedinbiofuels take pride in reducing greenhouse gas emissions while supporting the U.S. economy and energy independence.

would put milk pricing in linewiththecostofproduction across the country.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is also providing support for four Dairy Business Innovation Initiatives to help dairy farmers find ways to keep their operations going for future generations through grants, research support and technical assistance.

Another way to boost localdairiesistobuydirectly fromafarmer.Value-added or farmstead dairy operations that make and sell milk and products such as cheese straight to customers have been growing. These operations come with financial risks for the farmer, however.

Being responsible for milking, processing and marketing your milk takes the already big job of milk production and adds two more jobs on top of it. And customershavetobefinancially able to pay a higher pricefortheproductandbe willing to travel to get it.