F a F ard & F riends

essay by terren C e heath

Jo E fafa RD g RE w up in the small village of Ste. Marthe, Saskatchewan, near the Manitoba border. He, his father and mother and his siblings worked hard to maintain a family on the farmland of Ste. Marthe. Every Sunday and every holy day was time off from work, except for the necessities of taking care of the animals. The family took their Catholic beliefs very seriously, and the church was the centre of their lives.

One of Fafard’s tasks while growing up was to help his mother get the church ready for Sundays and holy days, and his earliest art was reflective of his tasks. A part of his job was to clean and dust the figures of the saints placed in niches high up in the church, which served as spiritual guides who watched over the parishioners. They were holy figures, and for Fafard, these sacred icons were also his first realization of what artworks could be.

The figures that Fafard created in later life as an artist seem, at first, to have little connection with those saints of his boyhood. It is true that he left behind his overt childhood religious thoughts early in his adult life. However, Fafard used his hands to fashion his own personal icons. He created sculptures based on friends, politicians, Indigenous people and historic figures, among others. These Fafard-created icons invariably found space in his studio, and they watched over him and guided him as he worked. It is possible that the figures assembled in this exhibition were

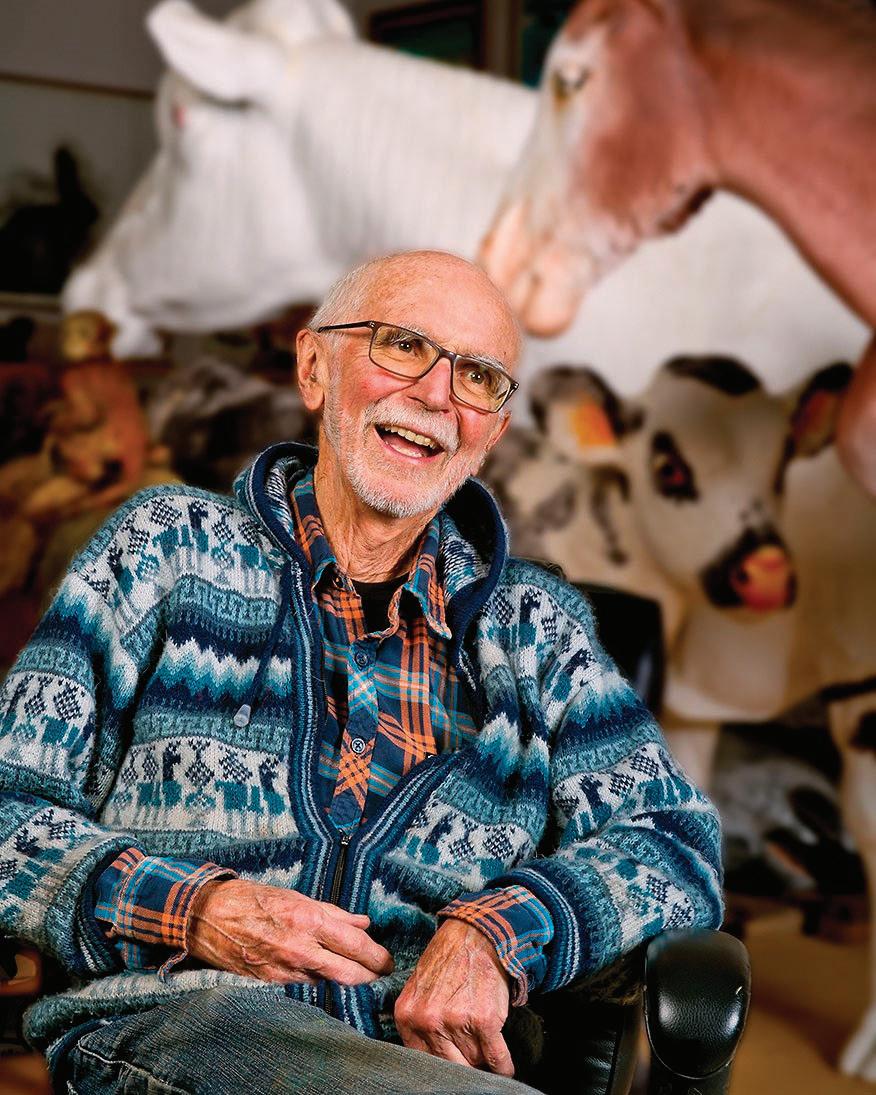

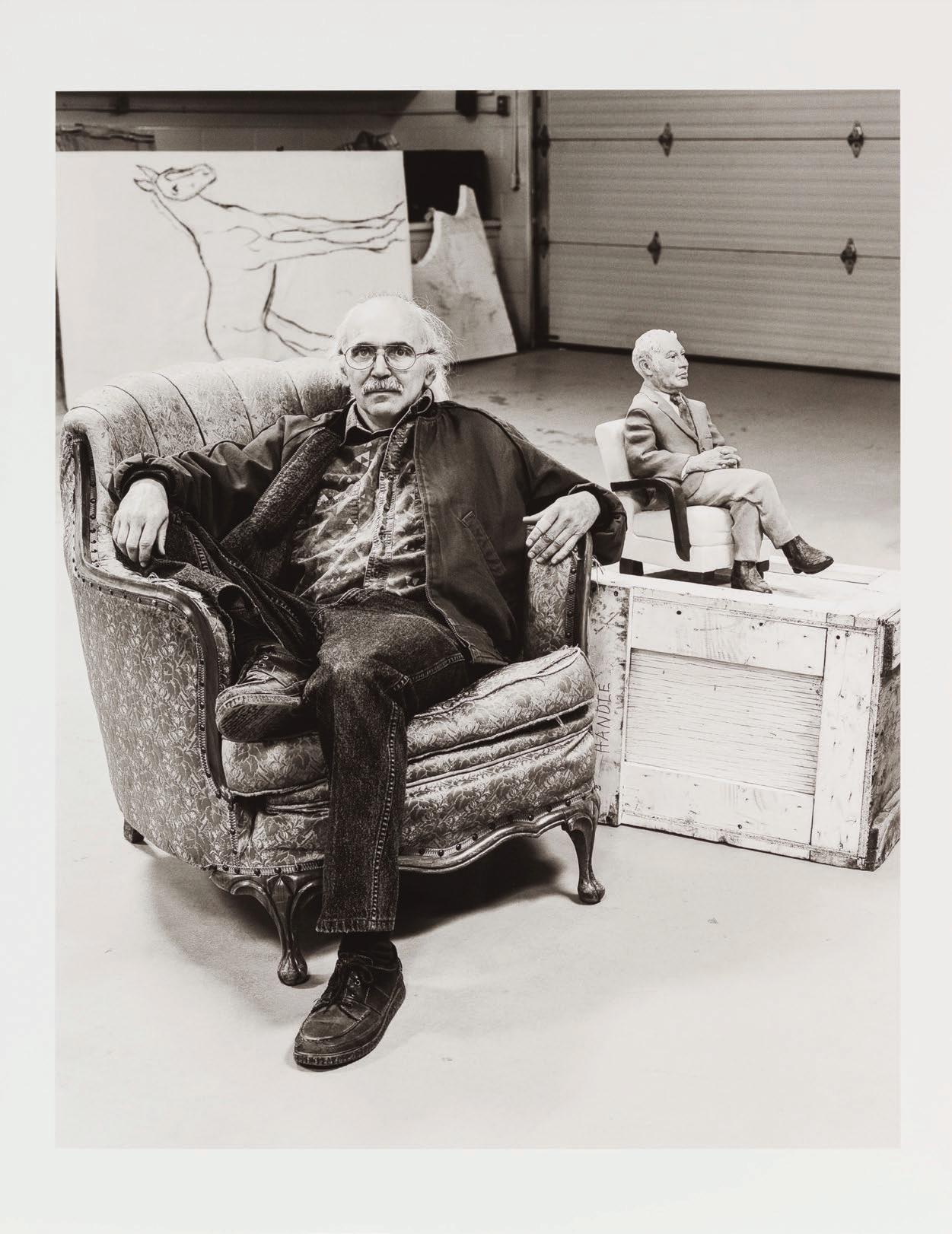

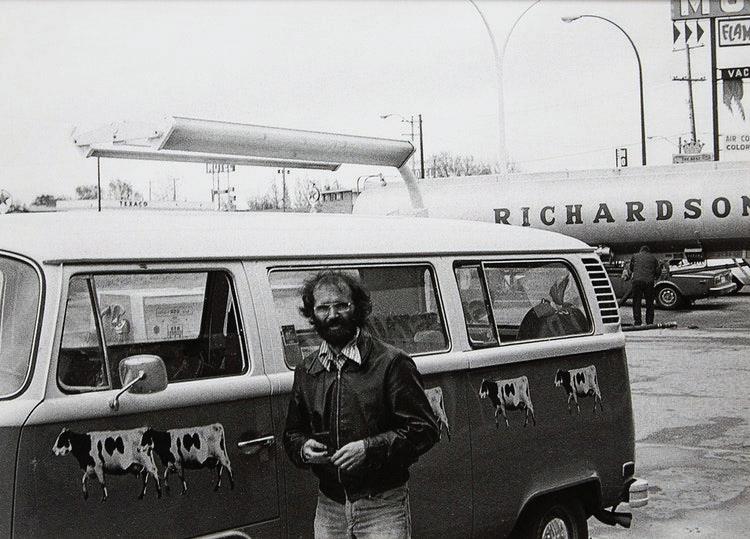

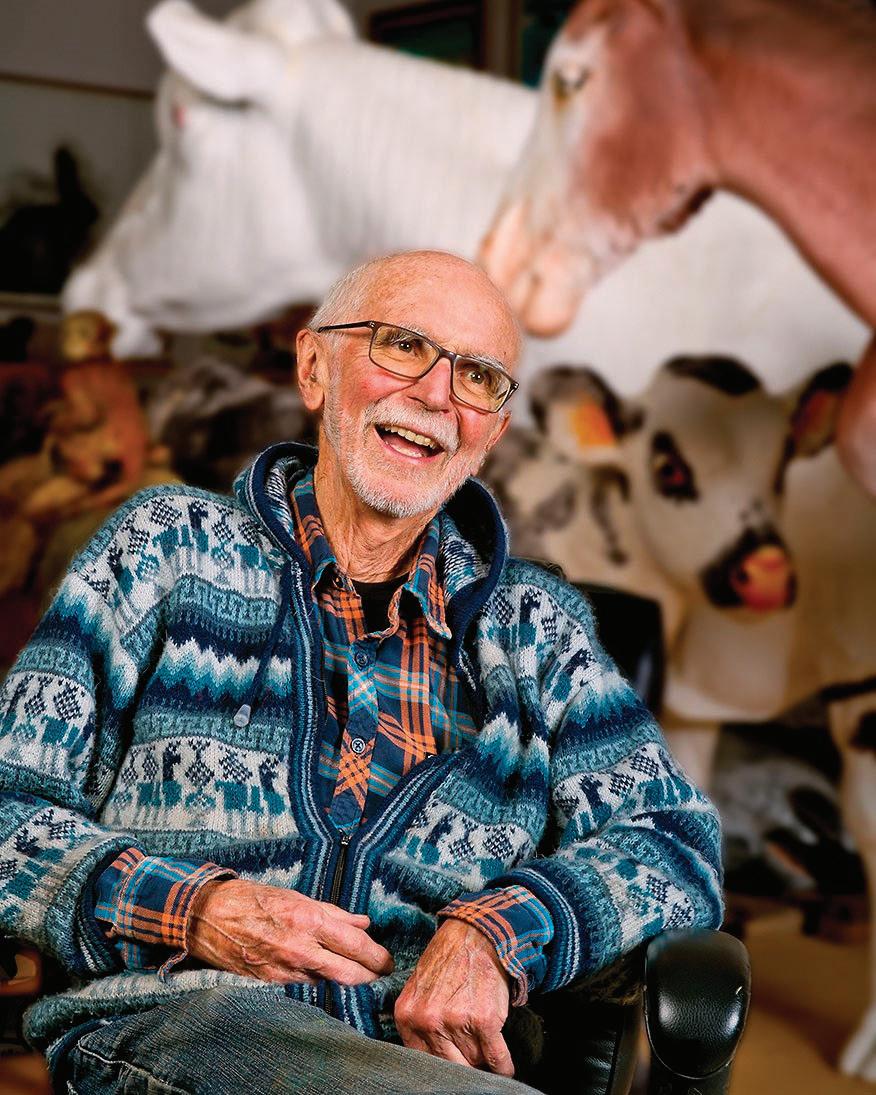

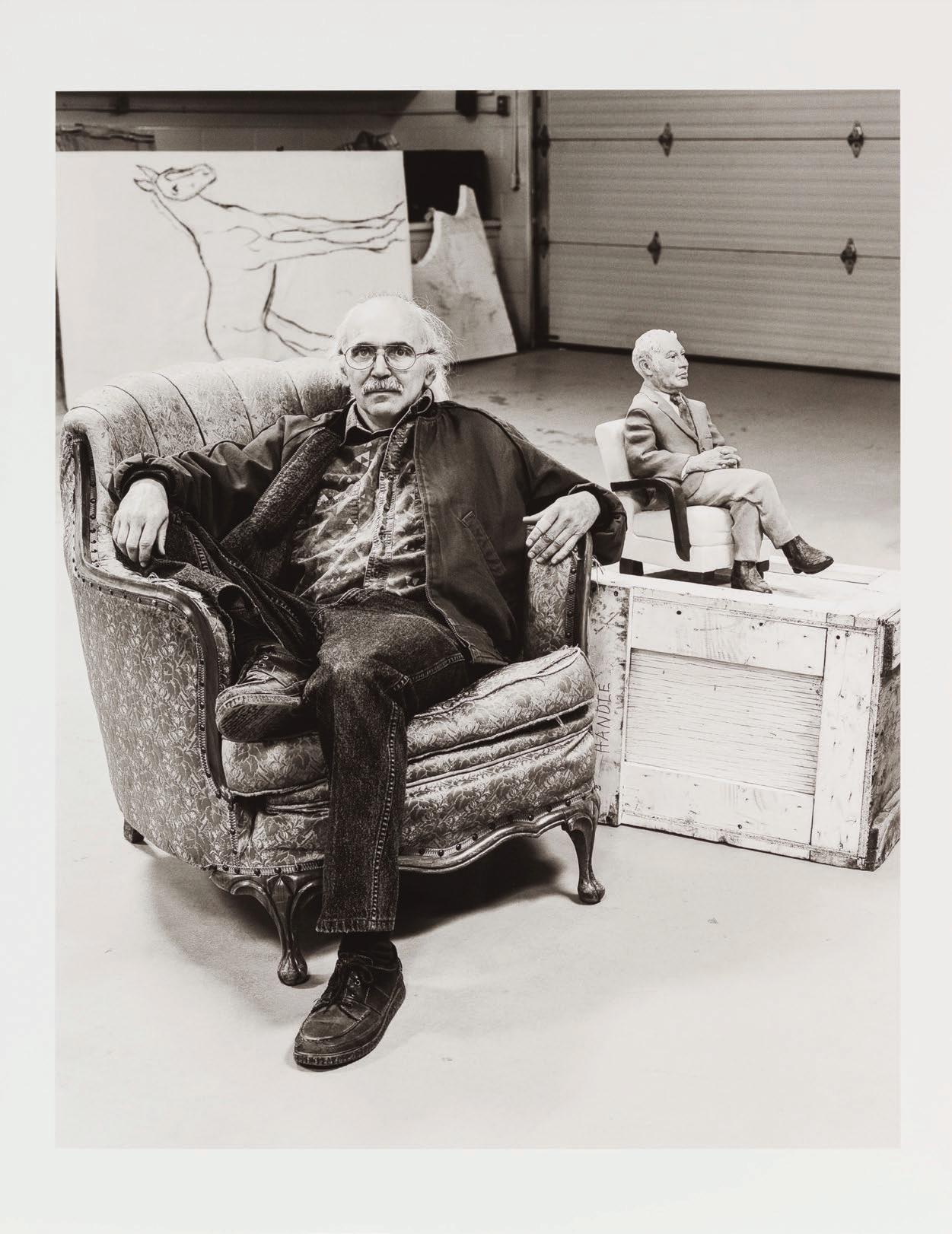

Joe Fafard in his studio

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joe Fafard in his studio

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

some of the saints of Joe’s life as an artist. Egon Schiele, Paul Gauguin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Pablo Picasso, Pierre-Auguste Renoir—these are all artists that would have inspired Fafard. O’Keeffe, for example, was always depicted by Fafard as a monumental figure whose presence demonstrated the impact that an artist could have. Picasso was the artist who taught Fafard the value of a life of innovation, and his example gave him permission to try out many forms in his artwork. These artists were like the saints Fafard had so carefully cleaned and examined as a boy—they were guides and inspirational figures.

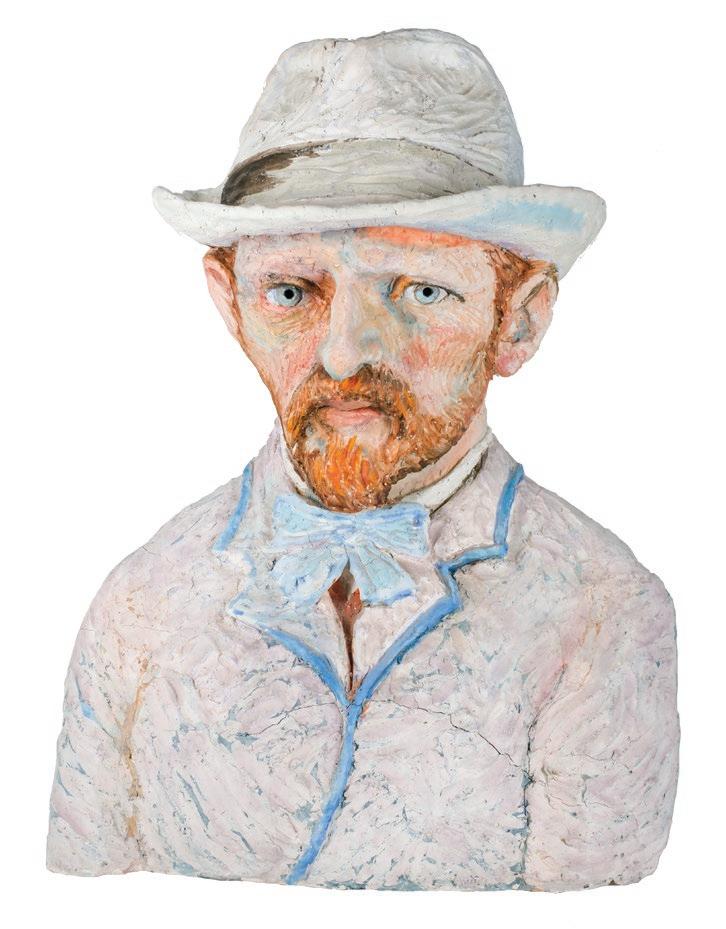

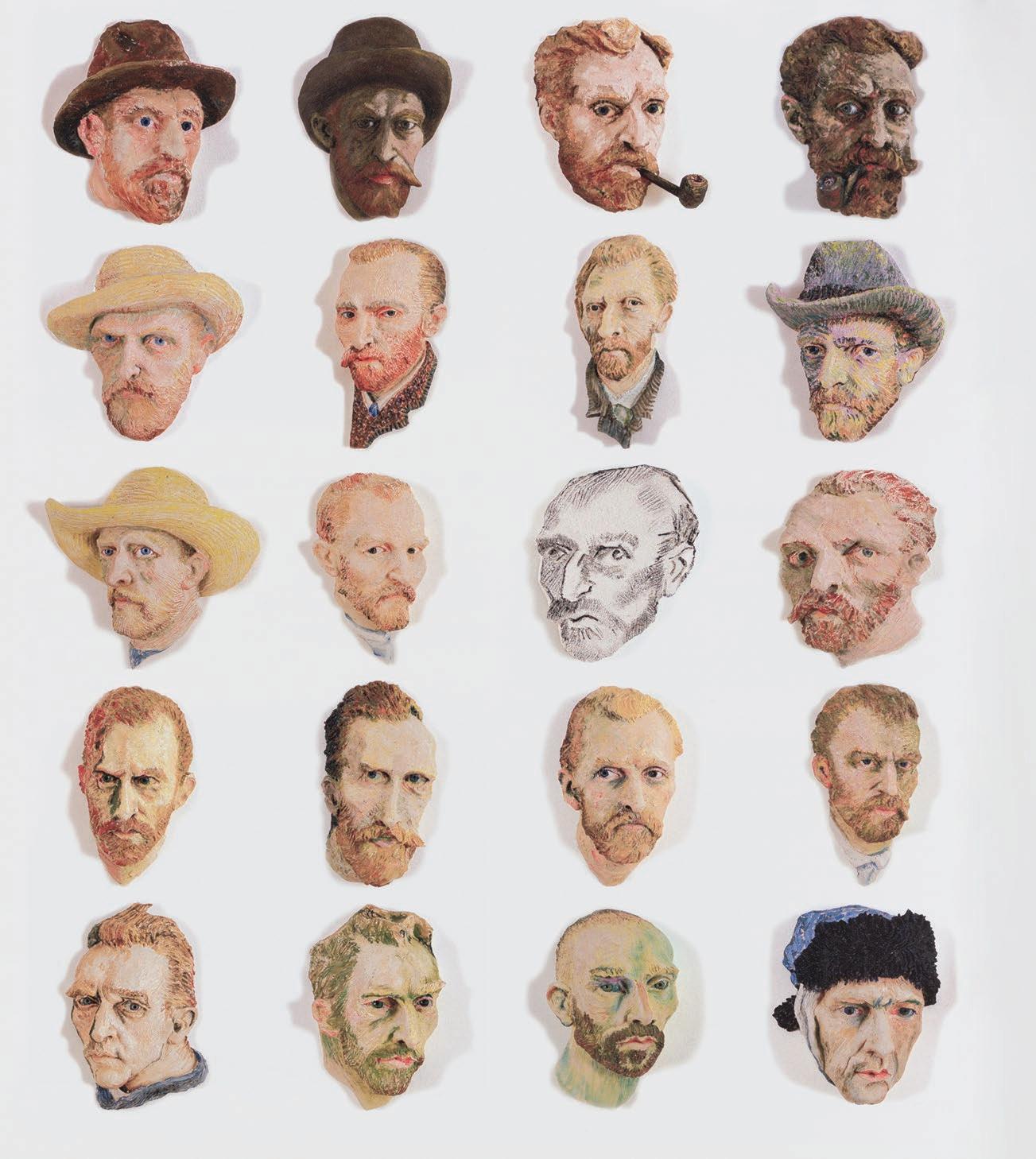

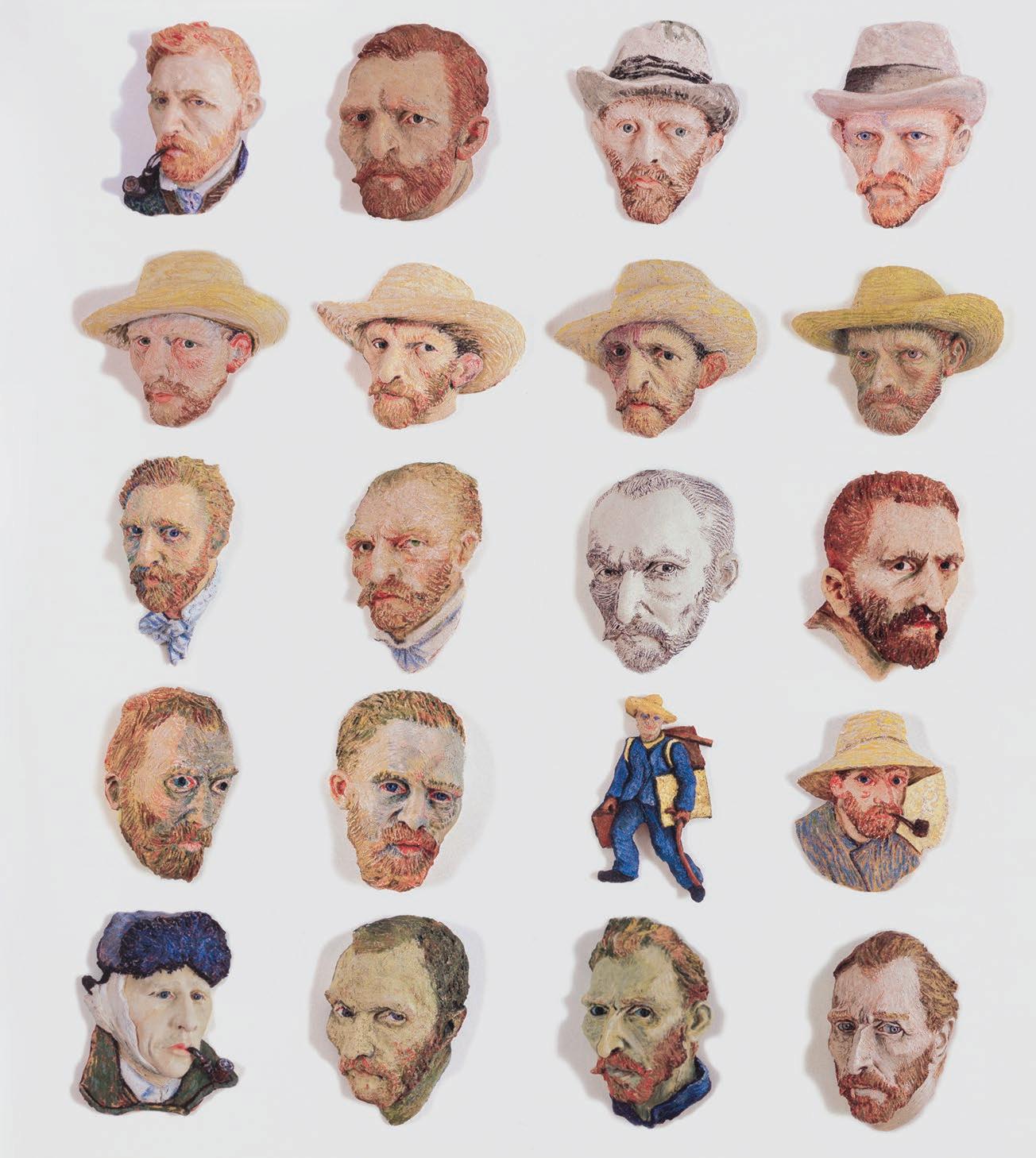

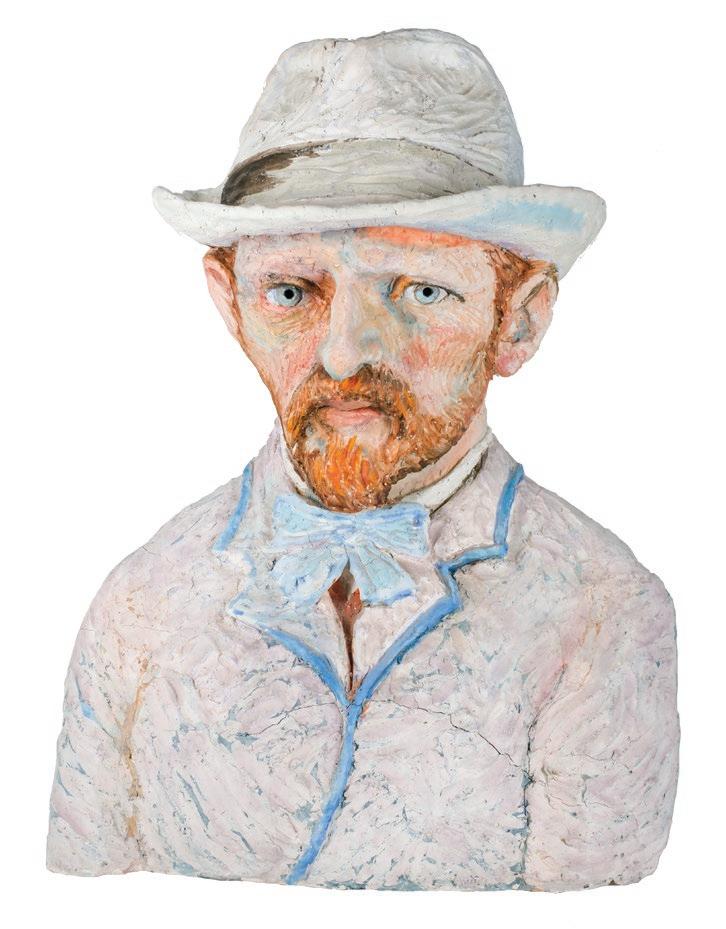

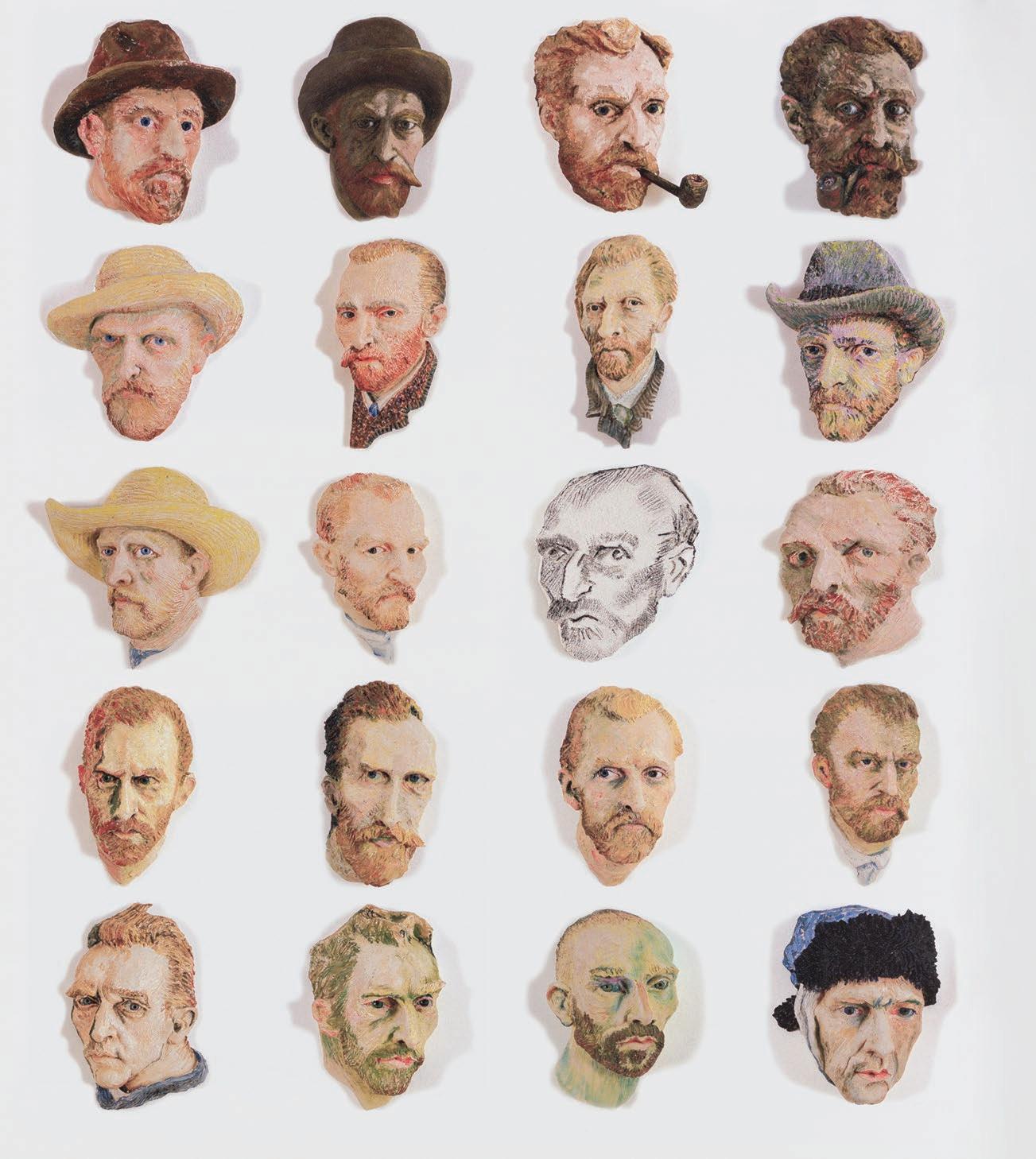

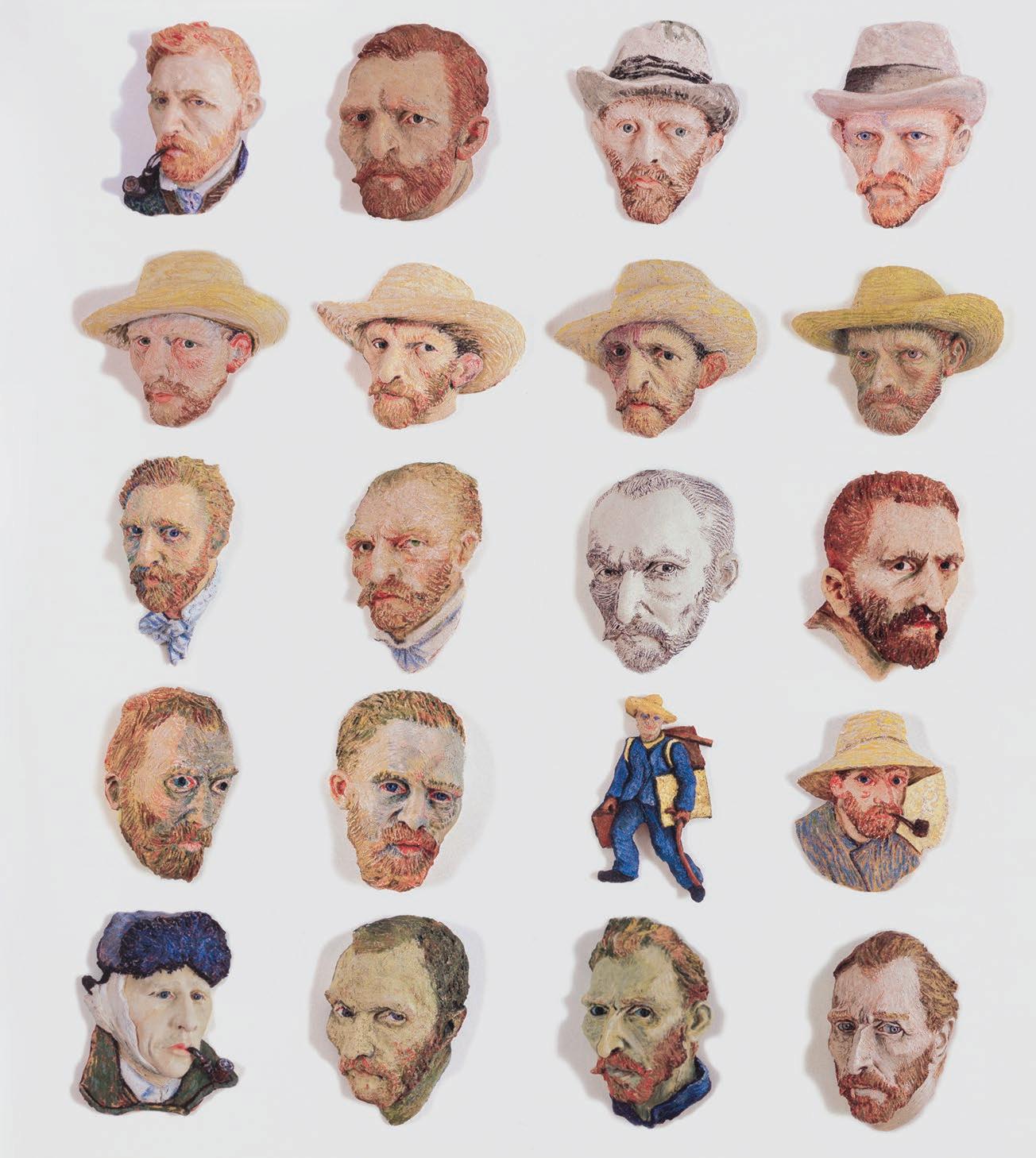

One artist whose life and works meant a great deal to Fafard throughout his own life as an artist was Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh during his life was seen as a failure. He lived off his brother Theo, who willingly supported him, and although he tried, he could not sell his works. His reputation after his death was in part a result of the dedication of his brother’s wife, who spent her widowhood establishing the legacy of his art. Fafard saw in van Gogh a troubled individual, but an artist who insisted on pursuing his own insight in the making of his art. The piece entitled Wounded Vincent (19) that Joe created was not only a powerful portrait, but it embodied a figure which Joe turned to throughout his working life. Fafard created many van Gogh sculptures throughout his life, the most recent being the bronze sculpture To Be or Not to Be (18).

In dealing with the work of Fafard, one has to recognize the role that animals assumed in his work. The French speak of some artists, studios and institutions as belonging to a specialized training in which the dominant subject matter is animals. They call practitioners of this

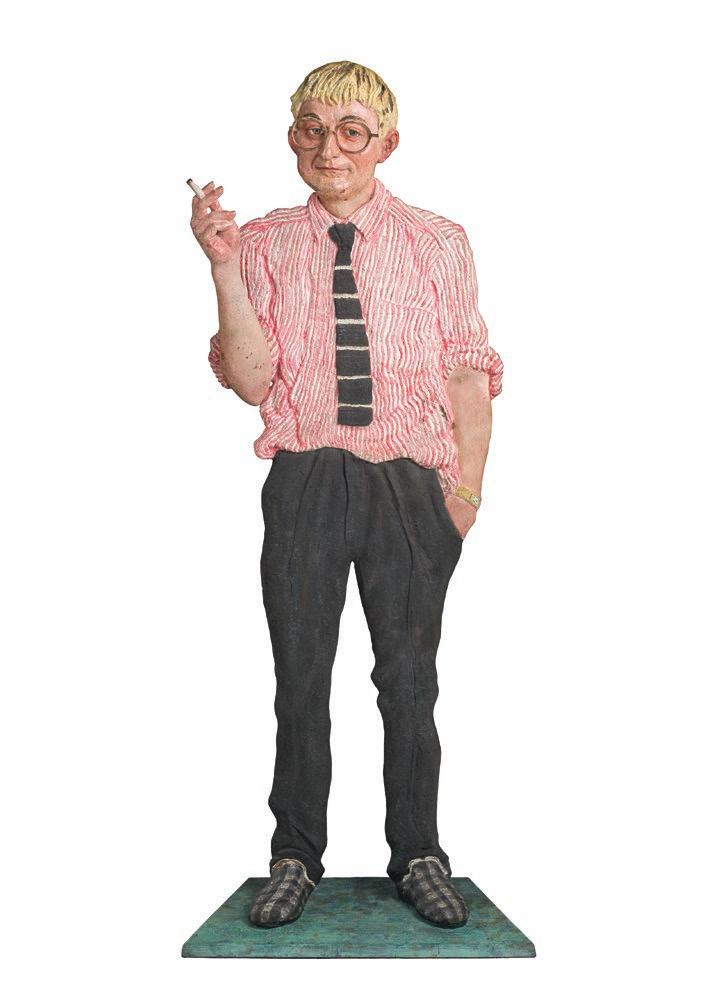

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard D.H.

bronze sculpture with patina, 1994 43 × 15 × 4 in, 109.2 × 38.1 × 10.2 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Auguste Renoir

bronze sculpture with patina, 1999 14 × 10 × 8 in, 35.6 × 25.4 × 20.3 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard D.H.

bronze sculpture with patina, 1994 43 × 15 × 4 in, 109.2 × 38.1 × 10.2 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Auguste Renoir

bronze sculpture with patina, 1999 14 × 10 × 8 in, 35.6 × 25.4 × 20.3 cm

Private Collection

Sold

24 5/8 × 19 × 8 in, 62.5 × 48.3 × 20.3 cm

Private Collection

Sold

The

25 × 17 × 12 in, 63.5 × 43.2 × 30.5 cm

Private Collection

Sold

genre animalières. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec trained in this style before he became a well-known artist in Paris. Fafard used his ability to recreate what he saw and experienced in his depictions of people and animals. For example, Fafard created the piece Sainte Rosa (16, 17), which shows a woman riding a lively horse and carrying a painter’s palette, from a photograph of Rosa Bonheur, one of the most famous of the French animalières. Fafard sensed, and communicated through his hands, that the painter riding the horse was in three dimensions. Fafard’s animal sculptures are an important part of his oeuvre.

Less well-known are the many sculptures Fafard created of Emily Carr. She was not trained as an animalière but her fascination with animals is everywhere to be seen in photographs of her. The image used in Fafard’s creation of a sculpture of her horse, Emily’s Horse (with Woo) (14), includes her pet monkey, looking quite at home from the saddle. Another sculpture, Emily (13, 15), shows the artist holding what looks like a sketchbook. Carr painted the art of the Indigenous people in British Columbia, who lived with the marine and land animals which shared the waters and land masses that they inhabited. Carr depicted their totem poles, which were genealogical stories of their families and mythical animals. She was not technically an animalière, but she loved animals and was fascinated by the people who lived closely with them. Fafard had grown up living with, and depending on, a large number of domestic and wild animals. He knew them as individuals, and he would include them in his work

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Van Gogh Arrives in Paris painted ceramic sculpture, circa 1983

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

Painter (van Gogh) bronze sculpture with patina, 1986

throughout his life. Humans were also animals that could be known and understood. The art of Fafard and Carr was not so far apart.

What Fafard learned from his personal saints was varied, and his interest in portraying his own experiences and the lives of others spanned prairie history. Fafard understood hard work and depicted those who lived by it. His creation of The Sower (4, 5) is an example of his own experience. It is an image of a person who sows seeds by hand and looks forward to the harvest. But as the person portrayed is van Gogh, another meaning is how an artist sows ideas.

Fafard understood what Indigenous people had experienced when their land was taken over by another people. A very close friend of Fafard was Tahltan and Tlingit artist Dempsey Bob, portrayed in the sculpture Dempsey (24). He became one of the elders of his people, and Fafard portrayed him waiting, his satchel over his shoulder, his patience obvious in his stance.

There is much contained in the artwork of Fafard. Each piece is a part of a story of the Canadian prairies as well as the work of an artist who dedicated his talents to telling his history in his work.

We thank Terrence Heath, author of the book Joe Fafard, for contributing the above essay.

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Emily Carr (on Horse) bronze sculpture with patina, 2003

34 × 33 × 11 in, 86.4 × 83.8 × 27.9 cm Private Collection

Sold

F a F ard et ses a M is

e ssai de t erren C e h eath (traduit de l’anglais)

Jo E fafa RD Pa SSE son enfance dans le petit village de Sainte-Marthe en Saskatchewan, près de la frontière manitobaine. La famille au grand complet travaille fort pour subvenir à ses besoins sur une terre agricole. Joe, son père et sa mère, ainsi que ses frères et sœurs prennent congé seulement les dimanches et les jours fériés, mais ils doivent tout de même prendre soin des animaux. Les Fafard sont catholiques et très croyants, et l’église est au cœur de leur vie.

L’une des tâches du petit Joe consiste à aider sa mère à préparer l’église pour les messes et les fêtes religieuses. Il doit entre autres monter jusqu’aux niches pour nettoyer et épousseter les statues des saints, les guides spirituels et les protecteurs des paroissiens. C’est en côtoyant ces icônes sacrées que Fafard prend conscience du pouvoir des œuvres d’art.

Les figures que Fafard créera plus tard ne semblent pas, à première vue, avoir beaucoup de liens avec les saints de son enfance. Au début de sa vie d’adulte, il délaisse la religion, mais il façonne ses propres icônes de ses mains en s’inspirant notamment d’amis, d’hommes politiques, d’Autochtones et de personnages historiques. Ces icônes trônent en bonne place dans l’atelier de Fafard. Comme les statues de saints de sa jeunesse, elles veillent sur lui et le guident pendant qu’il travaille. Les

Joe Fafard, 2016

Photo: © Joseph Hartman

Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

Joe Fafard, 2016

Photo: © Joseph Hartman

Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

effigies réunies dans cette exposition sont peut-être quelques-uns des « saints » qui ont accompagné Joe tout au long de sa carrière. Egon Schiele, Paul Gauguin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Pablo Picasso et Pierre-Auguste Renoir, entre autres, auraient inspiré Fafard. Par exemple, Fafard a toujours représenté O’Keeffe en figure monumentale pour démontrer l’impact qu’un artiste peut avoir. Pour sa part, Picasso a en quelque sorte enseigné à Fafard la valeur d’une vie consacrée à l’innovation et lui a laissé le champ libre pour expérimenter de nombreuses formes dans sa pratique. En plus d’être des guides comme les statues de saints de l’église de Sainte-Marthe, ces artistes étaient des sources d’inspiration.

Vincent van Gogh est l’un de ces artistes qui ont toujours compté pour Fafard. Van Gogh a connu l’échec toute sa carrière. Il vivait aux crochets de son frère Théo, qui lui offrait volontiers son soutien, mais malgré ses efforts, il n’a jamais réussi à vendre ses œuvres. Sa réputation après sa mort est en partie attribuable au dévouement de la femme de son frère qui, une fois devenue veuve, s’est consacrée à mettre en valeur le legs artistique de Vincent. Fafard a vu en van Gogh un être troublé, en plus d’un créateur qui a insisté pour suivre sa propre voie. Le Wounded Vincent (19) de Joe Fafard est non seulement un portrait puissant, mais aussi l’incarnation d’une figure vers laquelle Joe s’est tourné durant sa carrière. Fafard a fait de nombreuses sculptures de van Gogh, la dernière étant un relief en bronze intitulé To Be or Not to Be (Être ou ne pas être) (18).

Joe Fafard in his studio, Pense, 1979

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joe Fafard in his studio, Pense, 1979

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

9 7/8 × 6 5/8 × 2 1/2 in, 25.1 × 16.8 × 6.4 cm each

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

Vincent Self-Portrait Series painted ceramic

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

Vincent Self-Portrait Series painted ceramic

Les animaux occupent une place importante dans l’œuvre de Fafard. Les Français qualifient d’animaliers les artistes, ateliers et institutions qui se vouent à la représentation d’animaux. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, entre autres, s’est initié à ce genre avant d’acquérir une renommée à Paris. Fafard a exploité sa capacité à recréer avec son art ce qu’il a vu et vécu. On pense notamment à Sainte Rosa (16, 17) qui représente une femme tenant une palette de peintre chevauchant un cheval fougueux, sculpture réalisée à partir d’une photographie de Rosa Bonheur, l’une des plus célèbres animalières françaises que Joe a transposée en trois dimensions, avec ses mains.

Les sculptures animales de Fafard constituent une part appréciable de son œuvre. En revanche, ses nombreuses sculptures d’Emily Carr sont méconnues. Carr n’avait reçu aucune formation en art animalier, mais sa fascination pour les animaux est manifeste dans les photographies d’époque. Celle dont s’est inspiré Fafard pour créer Emily’s Horse (with Woo) (14) représente le cheval de Carr, mais aussi un singe, son animal de compagnie, qui semble tout à fait à l’aise, perché sur la selle. Le sujet de la sculpture Emily (13, 15) tient ce qui ressemble à un cahier de croquis, rappelant l’intérêt de Carr pour l’art des peuples autochtones de la Colombie-Britannique, qui devaient leur survie aux animaux marins et terrestres, et partageaient avec eux les eaux et le territoire qu’ils habitaient. Carr a peint et dessiné leurs mâts totémiques représentant leurs généalogies et bêtes mythiques. Carr n’était pas une animalière au sens propre, mais elle adorait les animaux et était fascinée par les gens qui vivaient auprès d’eux. Dans le même ordre d’idée, Fafard avait grandi en présence d’animaux domestiques et sauvages, dont il dépendait. Il les considérait comme des individus et les a intégrés dans son œuvre tout au long de sa vie. L’être humain est lui aussi un animal que l’on peut côtoyer et comprendre. Après tout, l’art de Fafard et celui de Carr ne sont pas si éloignés.

Fafard a appris différentes choses des saints de son enfance. Son intérêt pour ses propres expériences et la vie des autres couvre l’histoire des Prairies. Familier avec le dur labeur, Fafard représentait les gens qui vivaient de la terre. Son Semeur (4, 5), qui attend la récolte avec impatience, est une métaphore de sa vie. Toutefois, comme le personnage a les traits de van Gogh, on peut aussi y voir un artiste qui sème des idées.

Fafard comprenait fort bien ce que les Autochtones avaient vécu lorsque leurs terres avaient été saisies par d’autres peuples. Il était d’ailleurs très proche de Dempsey Bob, un ancien issu des communautés tahltan et tlingit. Fafard lui a dédié la sculpture Dempsey (24) qui le représente en train d’attendre patiemment, sacoche sur l’épaule.

Les œuvres de Fafard recèlent un contenu riche. Chacune révèle un pan de l’histoire des Prairies canadiennes, mais aussi de la vie d’un artiste qui a consacré son talent à se raconter.

Nous remercions Terrence Heath, auteur du livre Joe Fafard, pour la rédaction de ce texte, traduit de l’anglais.

Joe Fafard, 2018

Photo: Gary Robins Courtesy of Gary Robins

Jo E

Joe Fafard, 2018

Photo: Gary Robins Courtesy of Gary Robins

Jo E

fafa RD wa S my uncle, my boss, my art teacher and my friend. I knew of Joe’s talent even before I started working with him 33 years ago. I knew him as a member of our family, along with my grandmother and many others, who was very artistic. This facet of our family is just something we took for granted. He hired me right out of high school when he opened his foundry, Julienne Atelier. I was amazed at what he could do, but at the same time we knew “that’s just what Joe does.”

When I started in 1985, when Joe was transitioning into doing bronzes, I didn’t have a clue what this was all about. It took me a month to understand the whole process, but Joe had hired Pierre L’Heritier from France, who was a master in bronze casting, so we were being taught by him too. We used a lost-wax process, which is an older style of casting than we use today. But it worked well, and we worked that way for around the first ten years. After Pierre went on to do other things, we studied a ceramic shell technique at a foundry outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Going to this new method opened up easier ways of casting Joe’s work. It was at that point that I stepped into more of a management role. Joe let me do the casting the way I needed to, because he didn’t want to be as focused on the business of production, as much as he was on creating the art. He trusted me to grow and change the foundry, and in a way, he saw it like he saw his own art—we were always learning, and finding ways to improve, and we still are. We mastered producing his work in the foundry by finding new ways to do it, and his trust was a major part of that. We butted heads sometimes, and there were some sleepless nights, but we’d talk, plan and make it work.

Now, with the posthumous works, there are five of us at the foundry who are like family, and we all know how Joe approached things and wanted things done. He made us a part of the process, and even though he trusted us to run things the way we needed to, he was right there, working just as hard or even harder than any of us. He was majorly involved with his work, and we all learned directly from that. We were taught to respect the intention of the artist, whether it was Joe or anyone else we were working with, and we know this is the most important part of what we do. He had an overview of the entire process in mind all the time, thinking of the final patina all the way from the beginning of the sculpting process. He instilled that awareness in us, and it’s what we try to pass along to other artists we work with.

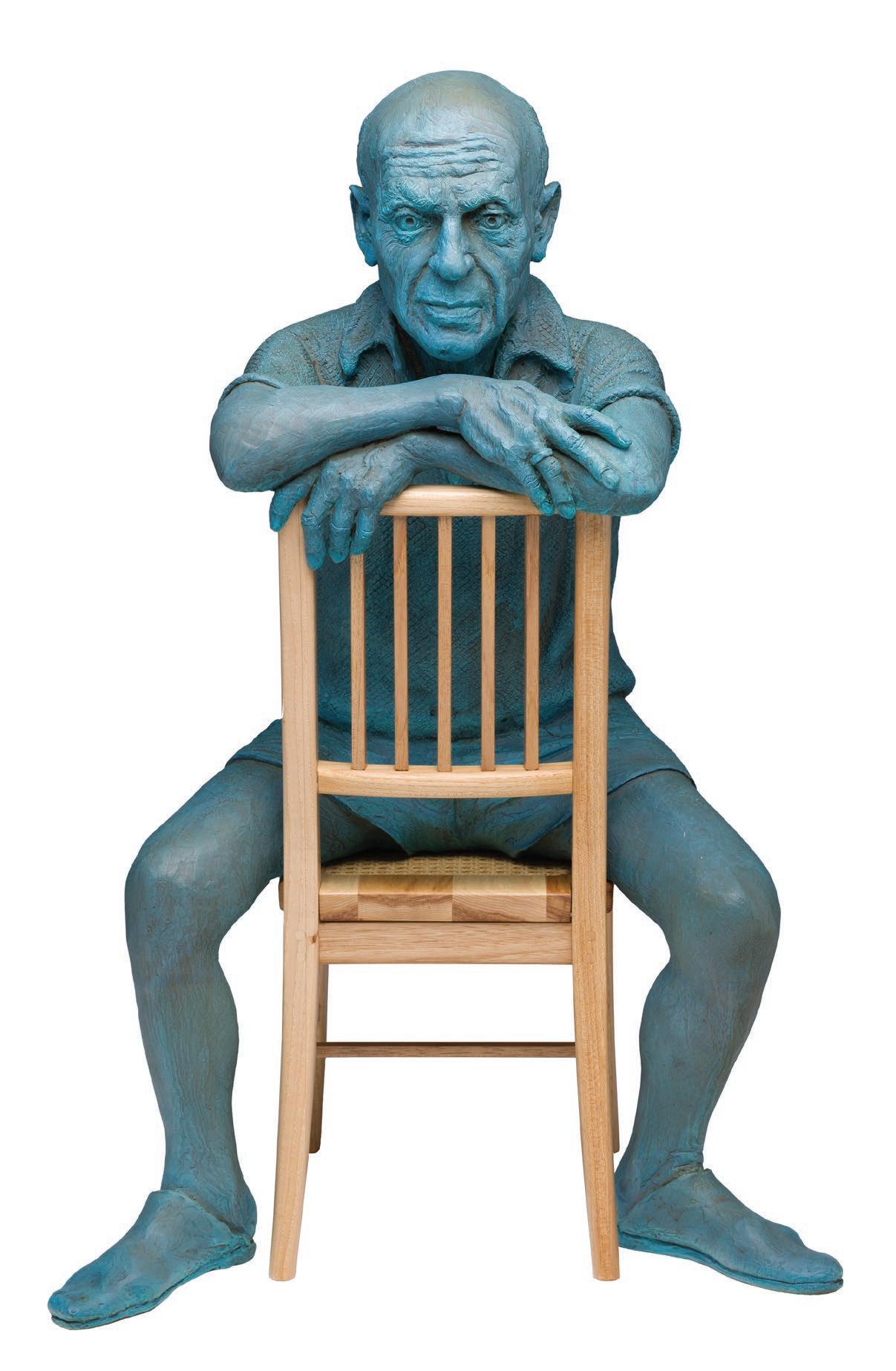

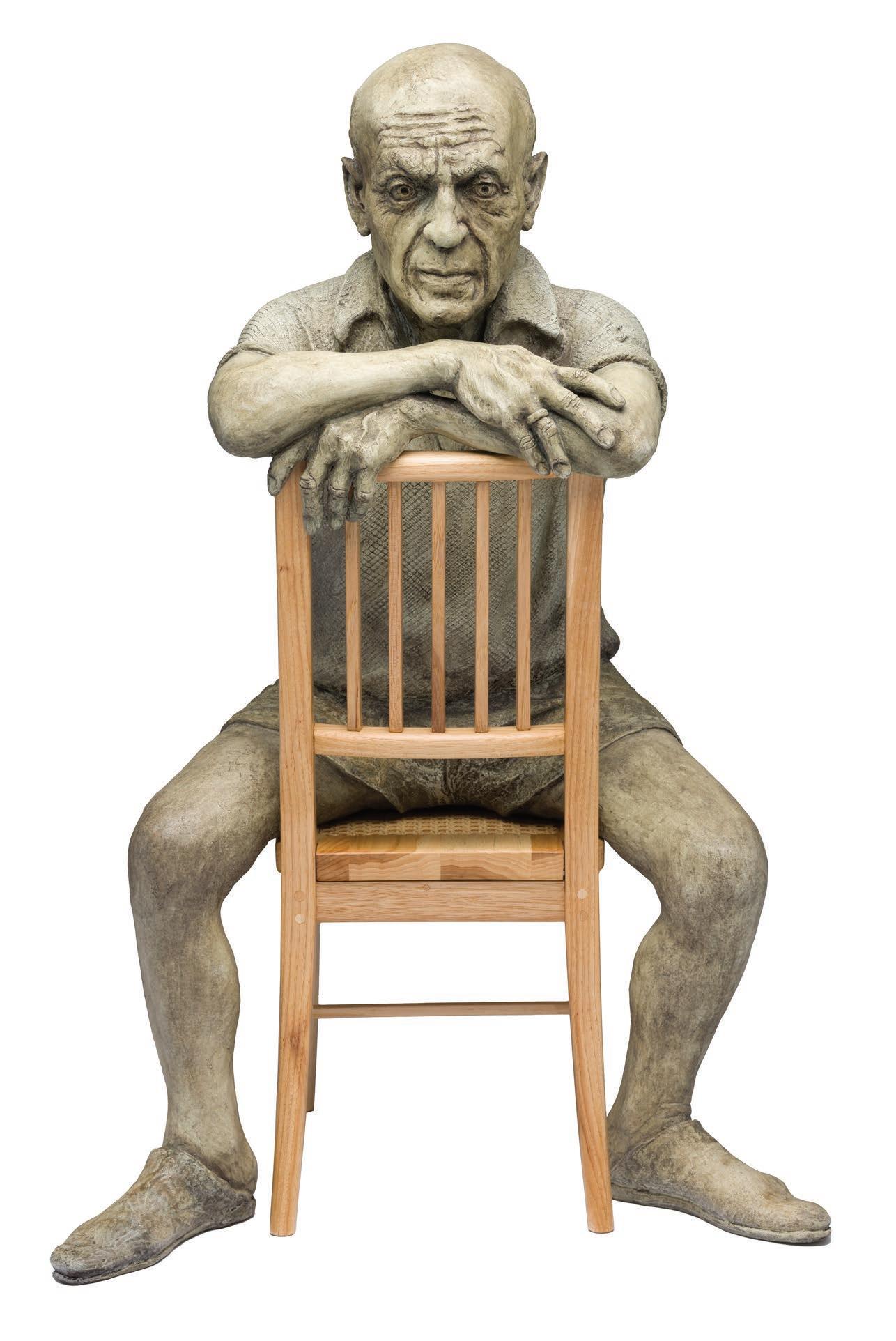

Now, without Joe around, working on this show, we knew we couldn’t and shouldn’t try to copy the way he worked with patina, colour, or powder-coating. We knew we should try to find a way to show the work and details that his hands put into making the sculpture instead. While the decision of the posthumous patina was my responsibility, it was important to choose something that the Fafard family, everyone at the foundry and potential clients would be happy with, and I think we have. Using this patina and our posthumous foundry stamp, we can produce Joe’s final works such as Picasso on a Chair and cast the remaining works from the incomplete editions, while

n otes F ro M the F oundry

honouring what makes his work so important and alive. If Joe were here, he’d say: “Do the work, do it well, enjoy it, and be proud.” Joe always looked out for us, and now, this is us looking out for Joe.

Ph I l tRE mblay Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier

Phil Tremblay, Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier, with Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9 ), 2023

Ph I l tRE mblay Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier

Phil Tremblay, Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier, with Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9 ), 2023

n otes de la Fonderie

Jo E fafa RD éta I t mon oncle, mon patron, mon professeur d’art et mon ami. Je savais qu’il avait du talent avant même de commencer à travailler avec lui il y a 33 ans. Pour moi, il était un membre de la famille, au même titre que ma grandmère et bien d’autres, doté d’un sens artistique poussé. Cette facette était pour nous une évidence. Joe m’a embauché dès la fin de mes études secondaires, lorsqu’il a ouvert sa fonderie, Julienne Atelier. J’étais émerveillé par ce qu’il arrivait à créer, mais en même temps, nous savions que c’était simplement « ce que Joe faisait ».

Lorsque j’ai commencé à travailler à l’atelier en 1985, à l’époque où Joe s’est lancé dans la création de sculptures en bronze, je n’avais pas la moindre idée de ce dont il

Joe Fafard with a model for The Sower, 2019

Joe Fafard with a model for The Sower, 2019

s’agissait. Il m’a fallu un mois pour comprendre l’ensemble du processus. Joe avait engagé Pierre L’Héritier, un maître fondeur français qui nous a également enseigné la technique. Nous utilisions un procédé à la cire perdue, une méthode qui fonctionnait bien (même si elle était plus ancienne que l’actuelle) et que avons employée pendant les dix premières années. Après le départ de Pierre pour faire d’autres projets, nous avons exploré une technique faisant appel à une coque en céramique dans une fonderie située près de Santa Fe, au Nouveau-Mexique. Cette nouvelle méthode a facilité la production des sculptures de Joe. C’est à ce moment-là que j’ai commencé à jouer un rôle plus important en gestion. Joe me laissait couler les œuvres au moyen de la technique que je privilégiais, parce qu’il voulait se concentrer sur la création plutôt que sur la production. Il me faisait confiance pour assurer le développement de l’atelier et apporter les changements que je jugeais appropriés. D’une certaine façon, il considérait cet atelier de la même façon qu’il abordait sa pratique artistique : nous étions, et nous sommes, constamment en train d’apprendre et de trouver des moyens de nous améliorer. Grâce, en grande partie, à la confiance que Joe nous témoignait, nous avons maîtrisé nos techniques pour produire ses œuvres. Nous avons parfois eu des divergences d’opinions et passé quelques nuits blanches, mais nous discutions, nous nous organisions et nous faisions en sorte que cela fonctionne.

Aujourd’hui, nous sommes cinq à la fonderie pour fabriquer les sculptures posthumes. Nous formons une famille. Nous savons tous comment Joe voyait les choses et voulait qu’elles soient faites. Il nous a intégrés au processus et, même s’il nous faisait confiance et nous laissait faire comme nous l’entendions, il était là, à nos côtés, travaillant aussi fort, voire plus, que chacun d’entre nous. Il s’investissait à fond dans son art et nous nous sommes tous inspirés de son engagement. Nous avons appris à respecter l’intention de l’artiste, que ce soit Joe ou une autre personne avec laquelle nous collaborons, et nous sommes conscients qu’il s’agit de la partie la plus importante de notre tâche. Joe avait constamment à l’esprit une vue d’ensemble, pensant à la patine finale d’une sculpture dès le début de sa conception. Il nous a inculqué cette préoccupation et nous essayons à notre tour de la transmettre aux autres artistes avec qui nous travaillons.

Lorsque nous avons organisé cette exposition, après le départ de Joe, nous savions que nous ne pouvions pas copier sa façon d’appliquer la patine, la couleur ou la peinture en poudre ni tenter de l’imiter. Nous étions conscients qu’il nous fallait plutôt trouver un moyen de mettre en valeur, sur chaque sculpture, les interventions et les détails qu’il avait faits de ses mains. C’est moi qui ai eu la responsabilité de patiner ses œuvres posthumes, mais il était capital de choisir quelque chose qui satisferait la famille Fafard, tous les employés de l’atelier et les clients potentiels, et je pense y être parvenu. Nous sommes en mesure de couler les dernières sculptures de Joe, comme Picasso on a Chair, et les œuvres restantes des éditions incomplètes, car elles porteront toutes sa patine caractéristique et notre cachet de fondeur posthume. Ainsi, nous pouvons honorer ce qui rend son œuvre si importante et si vivante.

Si Joe était là, il dirait : « Faites le travail, faites-le bien, aimez-le et soyez-en fiers. »

Joe a toujours veillé sur nous et maintenant, c’est nous qui veillons sur Joe.

Ph I l tRE mblay

Directeur général et directeur des opérations, Julienne Atelier

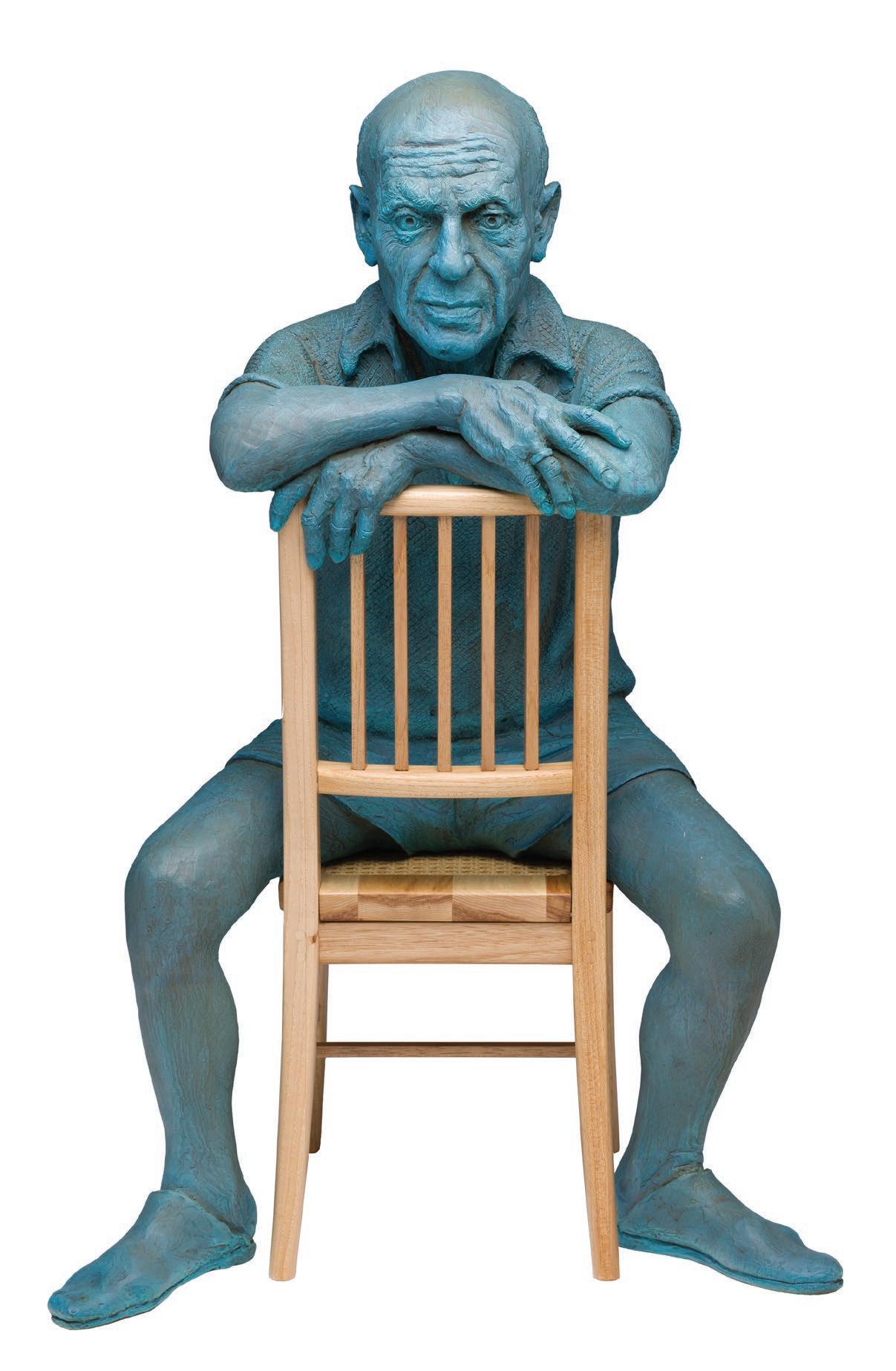

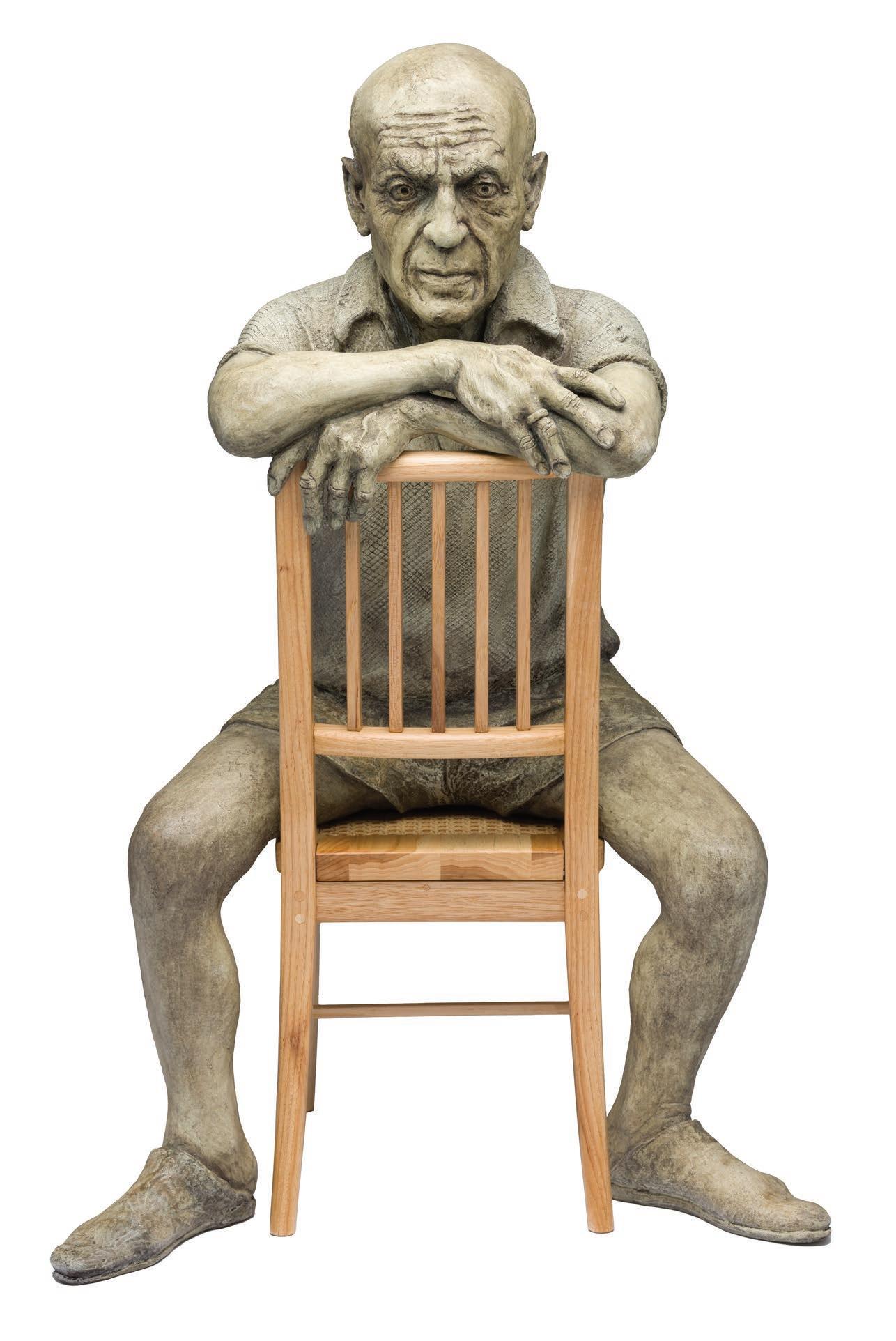

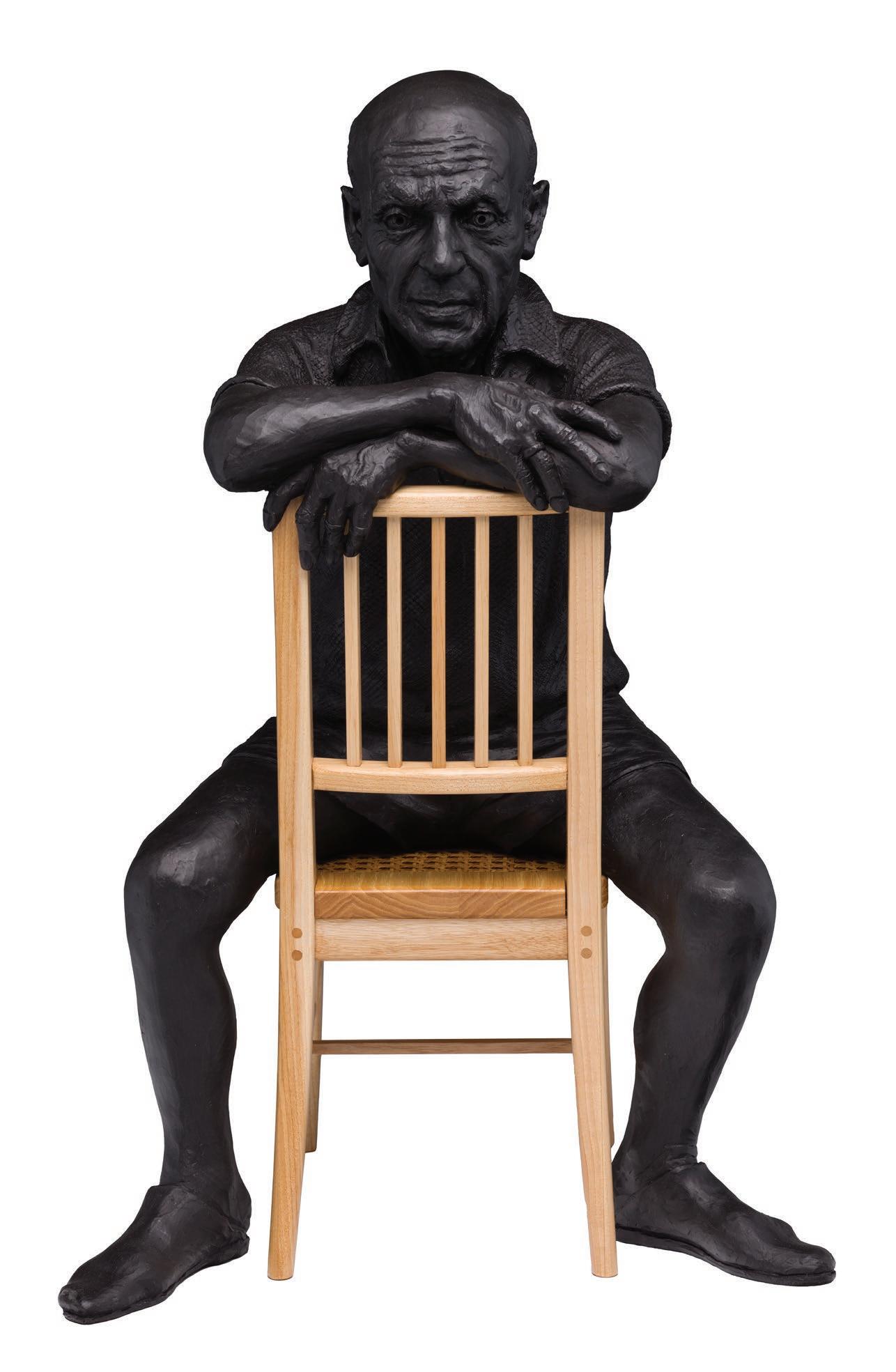

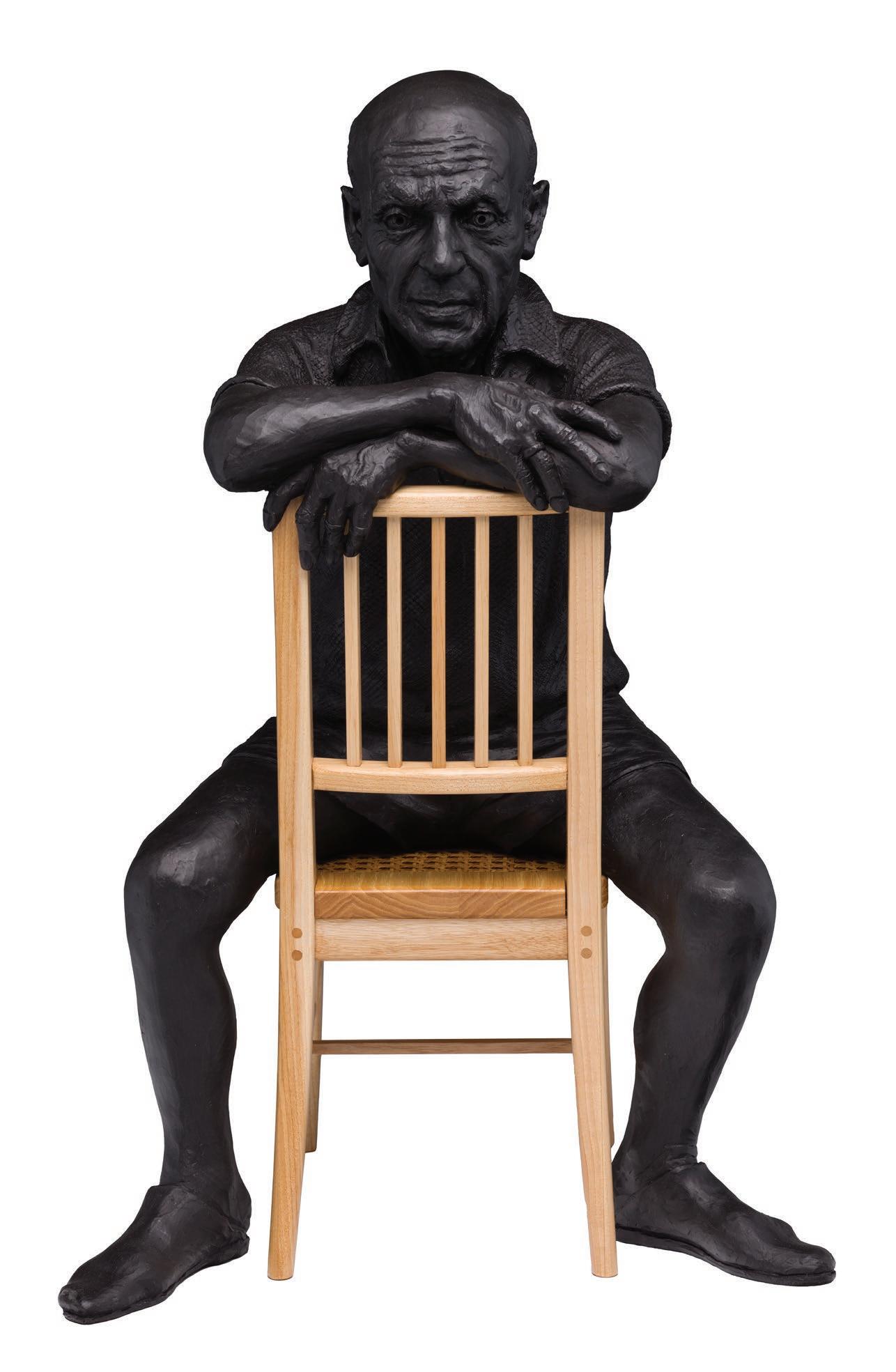

1 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9)

bronze sculpture with patina and wood, signed, editioned 6/9, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022

25 3/4 × 17 × 12 3/4 in, 65.4 × 43.2 × 32.4 cm

FI g URE 1: Portrait of Pablo Picasso

Photo: Arnold Newman

Courtesy of Getty Images

FI g URE 1: Portrait of Pablo Picasso

Photo: Arnold Newman

Courtesy of Getty Images

FI g URE 2: Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

The Opening

bronze sculpture with patina, glass and neon light on a wood base, 1988

33 × 17 3/4 × 12 1/2 in, 83.8 × 45.1 × 31.8 cm

Private Collection

Sold

FI g URE 2: Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

The Opening

bronze sculpture with patina, glass and neon light on a wood base, 1988

33 × 17 3/4 × 12 1/2 in, 83.8 × 45.1 × 31.8 cm

Private Collection

Sold

1980s, Joe Fafard began a long series of sculptures that were portraits of well-known artists. To Fafard, artists such as Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso were like a brotherhood in the history of art, what he called his “ancestral figures.” 1 Fafard produced a number of sculptures of Picasso—such as My Picasso from 1981, Le petit danseur, Standing Pablo and The Opening (figure 2), all from 1988. Picasso on a Chair from 2019 was his final depiction of the artist.

Fafard based Picasso on a Chair on a 1956 photograph of the artist taken in his Cannes studio by portrait photographer Arnold Newman (figure 1). He is sitting straddling the chair, leaning on the back like a shield or a prop. His posture is casual but slightly taut. His clothes are informal: the terrycloth shirt and shorts that he often wore in the South of France. Where Newman’s original photograph emphasizes Picasso’s quiet confidence, a master at ease surrounded by his artworks, Fafard instead chooses to capture the artist’s robust intensity. In Picasso’s penetrating gaze we sense his power, as if he is concentrating directly on the viewer. What dominates the figure are Picasso’s large head and strong hands, emphasizing his intelligence and vigorous creativity: the analytic mind of the artist and the hands that execute his vision.

Curiously, whereas Fafard had previously depicted artists as physically connected to their environment—casting Henri Rousseau’s chaise lounge or Emily Carr’s front stairs or the stool under Cézanne in the same bronze as the figures—here Picasso sits on a wood and rattan chair, a miniaturization of the original. This serves to both ground the vignette in reality, lending an immediacy to the sculpture, while also elevating Picasso as something apart from or beyond the material world: cast in metal, the figure of the artist is both tactile and unreal. Fafard masterfully captures the power and presence of this monumental figure of modern art.

The edition of Picasso on a Chair was cast posthumously, and the patina of each sculpture will vary.

1. Joe Fafard, Joe Fafard: The Bronze Years (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1996), exhibition catalogue, 31.

a u D ébut DES années 1980, Joe Fafard a entrepris la création d’une longue série de sculptures représentant des artistes célèbres—tels Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne et Pablo Picasso, entre autres—qu’ils considéraient comme les membres d’une confrérie de ses « figures ancestrales » 1 . Fafard a réalisé un certain nombre de sculptures de Picasso, telles que My Picasso de 1981 et Le petit danseur, Standing Pablo et The Opening (figure 2), toutes de 1988. Picasso on a Chair (2019) est sa dernière œuvre représentant cet artiste.

Pour réaliser Picasso on a Chair, Fafard s’est inspiré d’un portrait pris en 1956 par le photographe Arnold Newman (figure 1). Assis à califourchon sur une chaise

I N th E E a R ly

dans son atelier de Cannes, Picasso s’appuie sur le dossier comme s’il s’agissait d’un bouclier ou d’un accessoire. Quoique décontractée, sa posture dégage une certaine rigidité. Il porte une chemise en tissu éponge et un short, les vêtements qu’il privilégiait quand il vivait dans le sud de la France. Alors que la photographie originale de Newman met en relief l’assurance tranquille du maître à l’aise au milieu de ses œuvres, Fafard choisit plutôt de saisir l’intensité et la robustesse de l’artiste. On saisit la puissance de Picasso dans son regard pénétrant, comme s’il se concentrait directement sur le spectateur. C’est la grosse tête et les mains puissantes de Picasso qui dominent la figure, soulignant son intelligence et sa créativité vigoureuse : l’esprit analytique de l’artiste et les mains qui exécutent sa vision.

Curieusement, alors que Fafard avait déjà représenté des artistes physiquement liés à leur environnement—en incluant dans ses moulages en bronze, par exemple, la

Picasso on a Chair in the process of being cast

Picasso on a Chair in the process of being cast

chaise longue d’Henri Rousseau, l’escalier d’Emily Carr ou le tabouret de Cézanne— ici, Picasso est assis sur une chaise en bois et en rotin, une version miniature de l’original. Ce détail permet à la fois d’ancrer la vignette dans la réalité, conférant un caractère immédiat à la sculpture, et d’élever Picasso au rang d’un être à part ou au-delà du monde matériel : la figure de l’artiste, coulée dans le métal, est à la fois tangible et irréelle. Fafard capture magistralement la puissance et la présence de cette figure monumentale de l’art moderne.

Cette édition de Picasso on a Chair a été coulée à titre posthume et la patine de chaque sculpture varie.

1. Joe Fafard, Joe Fafard : les années de bronze (Montréal: Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal, 1996), catalogue d’exposition, 31.

Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9) at Julienne Atelier, 2023

Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9) at Julienne Atelier, 2023

2

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Picasso on a Chair (PH 2/9)

bronze sculpture with patina and wood, signed, editioned 2/9, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019 25 3/4 × 17 × 12 3/4 in, 65.4 × 43.2 × 32.4 cm

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

3

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Picasso on a Chair (PH 4/9)

bronze sculpture with patina and wood, signed, editioned 4/9, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022 25 3/4 × 17 × 12 3/4 in, 65.4 × 43.2 × 32.4 cm

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

4 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower (PH AP I )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP I, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

27 × 11 3/4 × 14 3/4 in, 68.6 × 29.8 × 37.5 cm

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower (PH AP II )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP II , dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019 27 × 11 3/4 × 14 3/4 in, 68.6 × 29.8 × 37.5 cm

5 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

5 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

6 7 8 9

6 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower Maquette (PH 2/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 2/7, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

11 3/8 × 4 1/4 × 6 1/4 in, 28.9 × 10.8 × 15.9 cm

7 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower Maquette (PH 3/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 3/7, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

11 3/8 × 4 1/4 × 6 1/4 in, 28.9 × 10.8 × 15.9 cm

8 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower Maquette (PH 4/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 4/7, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

11 3/8 × 4 1/4 × 6 1/4 in, 28.9 × 10.8 × 15.9 cm

9 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The Sower Maquette (PH 5/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 5/7, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022

11 3/8 × 4 1/4 × 6 1/4 in, 28.9 × 10.8 × 15.9 cm

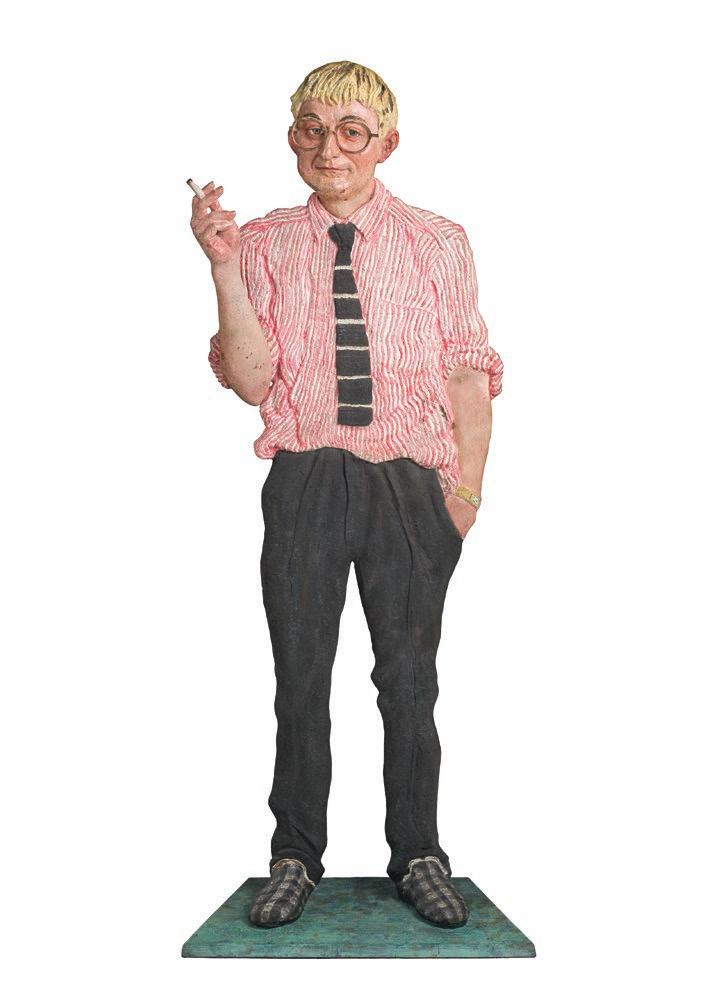

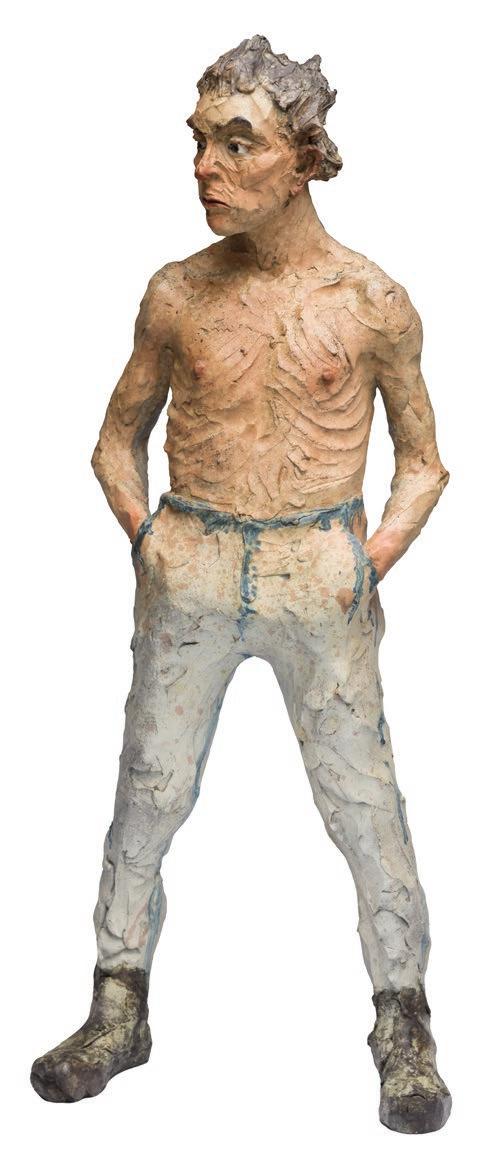

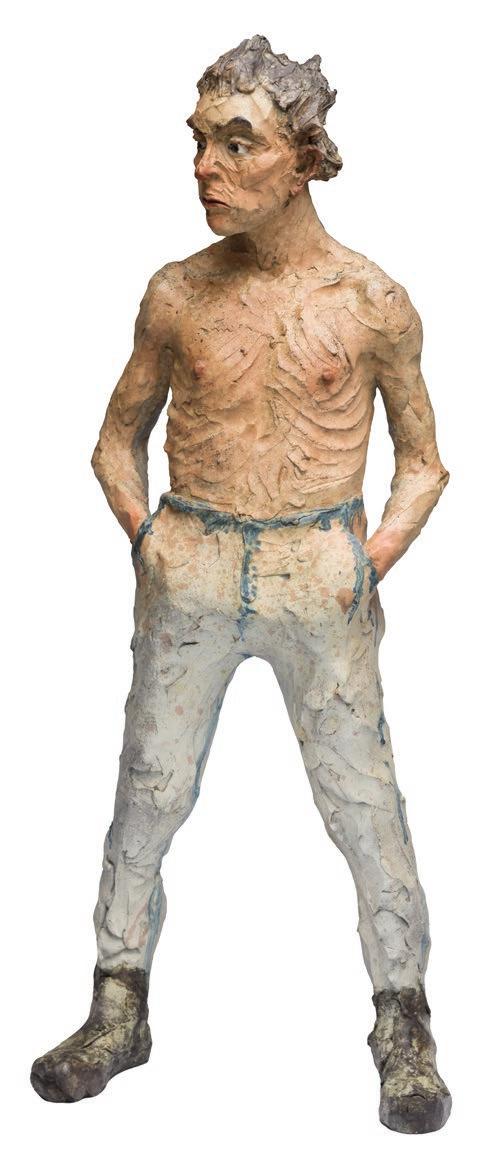

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Selfie (PH AP I )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP I, dated 2017, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022

35 × 14 1/2 × 7 in, 88.9 × 36.8 × 17.8 cm

w h E th ER I t wa S artists he admired from afar or farm animals he would see every day, Joe Fafard imbued his sculptures with the essential character of his subjects, candidly capturing a sense of their authentic self. This immediacy and intimacy becomes particularly poignant in Selfie, as Fafard turns his attention to himself in this masterful three-dimensional work.

Fafard produced Selfie at the end of his life: shortly after beginning the work, he received a cancer diagnosis and began undergoing chemotherapy. He felt it was an opportunity to present a record of himself and of his attitude as an artist. The self-conscious exercise was difficult, forcing Fafard to contend with viewing himself from the outside rather than from a place of pure introspection. The resulting work

10 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

is a profound self-portrait: hands on hips, brow-knit gaze sweeping in front of him, he presents himself as an artist defined by observation of the world around him and looking back at the culmination of a long life of creative activity.

Fafard was a master of structure and texture in his three-dimensional sculptures, and the fluid feeling of the clothes over his musculature is beautifully handled. The work is full of fine-grain detail and veracity characteristic of his practice: his pose, his hair and skin, the phone in his pocket and his sturdy shoes all add to the lifelike impression of the sculpture. The scale, too, is significant—in Fafard’s words, with a larger sculpture such as this the work “shares the space with the viewer . . . We feel

Selfie in the process of being cast

Selfie in the process of being cast

a presence comparable to that of another person in the room.” 1 Fafard had an exceptional ability to express the essential nature of living beings through clay and bronze. What Fafard communicated about his subjects was honest, timeless and universal; turning inward, what we feel piercingly in Selfie is the essence of his awareness.

The process of making this sculpture at the artist’s Pense, SK foundry can be seen in the 2022 documentary Fafard, directed by Jan Nowina-Zarzycki.

1. Quoted in Terrence Heath, Joe Fafard (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 2007), exhibition catalogue, 185.

Selfie in the process of being cast, with a completed lifetime version behind

Selfie in the process of being cast, with a completed lifetime version behind

Qu’ I l S ’ag ISSE DE représentations d’artistes qu’il admirait de loin ou d’animaux de ferme de son quotidien, Joe Fafard imprégnait ses sculptures de l’essence caractéristiques de ses sujets. Il saisissait avec candeur un sens de leur identité authentique. Cette immédiateté et cette intimité sont particulièrement poignantes dans Selfie, car Fafard se tourne vers lui-même dans cette magistrale œuvre tridimensionnelle.

Fafard a réalisé Selfie à la fin de sa vie. Peu après avoir commencé l’œuvre, il a reçu un diagnostic de cancer et a entrepris des traitements de chimiothérapie. Il a estimé que le moment était bien choisi pour présenter un témoignage sur lui-même et sur son attitude en tant qu’artiste. Cet exercice de prise de conscience a été difficile, obligeant Fafard à se regarder de l’extérieur plutôt que de se livrer à une introspection pure. L’œuvre qui en résulte est un autoportrait profond : il se présente les mains sur les hanches regardant devant lui d’un air soucieux, comme un artiste défini par l’observation du monde autour de lui qui jette un regard rétrospectif sur l’aboutissement d’une longue vie de création.

Fafard, un maître de la structure et de la texture dans ses sculptures tridimensionnelles, traite les vêtements de façon magnifique pour créer une sensation de fluidité sur sa musculature. L’œuvre regorge de détails raffinés et de la véracité caractéristiques de sa pratique : la posture, les cheveux et la peau de la figure, le téléphone dans sa poche et ses chaussures robustes accentuent l’impression de vie de la sculpture. De plus, l’échelle est importante. Dans les mots de Fafard, les sculptures de grande taille comme celle-ci « partagent l’espace avec le spectateur . . . Nous sentons une présence comparable à celle d’une autre personne dans la pièce. »1 Fafard avait une capacité exceptionnelle à exprimer la nature fondamentale des êtres vivants grâce à l’argile et au bronze. Ce que Fafard communiquait sur ses sujets était honnête, intemporel et universel. En nous tournant vers l’intérieur, ce que nous ressentons de manière aiguë dans Selfie est l’essence même de sa conscience.

Le documentaire Fafard, réalisé par Jan Nowina-Zarzycki en 2022, permet d’en savoir davantage sur le processus de fabrication de cette sculpture dans la fonderie de l’artiste à Pense, en Saskatchewan.

1. Cité dans Terrence Heath, Joe Fafard (Ottawa: Musée des beaux-arts du Canada, 2007), catalogue d’exposition 185.

Joe Fafard with Selfie, 2018

Joe Fafard with Selfie, 2018

11 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Selfie (PH AP II )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP II , dated 2017, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022 35 × 14 1/2 × 7 in, 88.9 × 36.8 × 17.8 cm

12 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Emily’s Horse (LT 1/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 1/7 and dated 2005

38 3/4 × 43 1/4 × 17 1/2 in, 98.4 × 109.9 × 44.5 cm

13 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Emily (PH AP I )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP I , dated 2005, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022 30 × 10 1/2 × 9 3/4 in, 76.2 × 26.7 × 24.8 cm

14 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Emily’s Horse (with Woo) (LT 3/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 3/7 and dated 2005

40 1/2 × 43 1/4 × 17 1/2 in, 102.9 × 109.9 × 44.5 cm

15 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe)

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Emily (PH AP II )

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned AP II , dated 2005, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022 30 × 10 1/2 × 9 3/4 in, 76.2 × 26.7 × 24.8 cm

Fafard

Fafard

16 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Sainte Rosa (LT 2/3)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 2/3 and dated 2014

28 1/2 × 11 1/4 × 33 in, 72.4 × 28.6 × 83.8 cm

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Sainte Rosa (LT 1/3)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 1/3 and dated 2014

28 1/2 × 11 1/4 × 33 in, 72.4 × 28.6 × 83.8 cm

17 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

18 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

To Be or Not to Be (PH 4/5)

bronze sculpture with patina and wood, signed, editioned 4/5, dated 2017, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019 29 1/2 × 6 1/8 × 28 1/4 in, 74.9 × 15.6 × 71.8 cm

19 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Wounded Vincent (Vincent blessé) (PH 7/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 7/7, dated 1994, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2023 29 1/2 × 7 1/2 × 23 1/2 in, 74.9 × 19.1 × 59.7 cm

20 21 22 22

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Egon Schiele I (PH 1/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 1/7, dated 2006, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

29 × 11 3/4 × 6 3/4 in, 73.7 × 29.8 × 17.1 cm

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Egon Schiele I (LT 3/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 3/7 and dated 2006

29 × 11 3/4 × 6 3/4 in, 73.7 × 29.8 × 17.1 cm

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Egon Schiele I (LT 2/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 2/7 and dated 2006

29 × 11 3/4 × 6 3/4 in, 73.7 × 29.8 × 17.1 cm

22 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

21 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

20 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

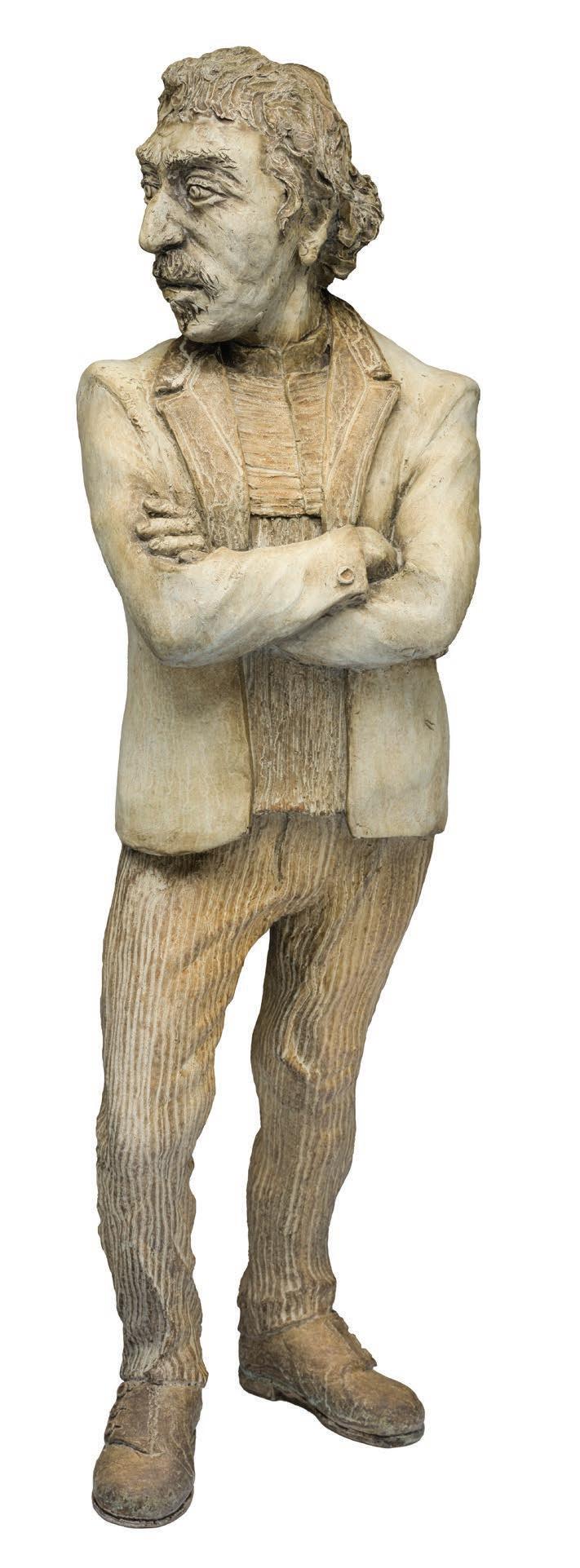

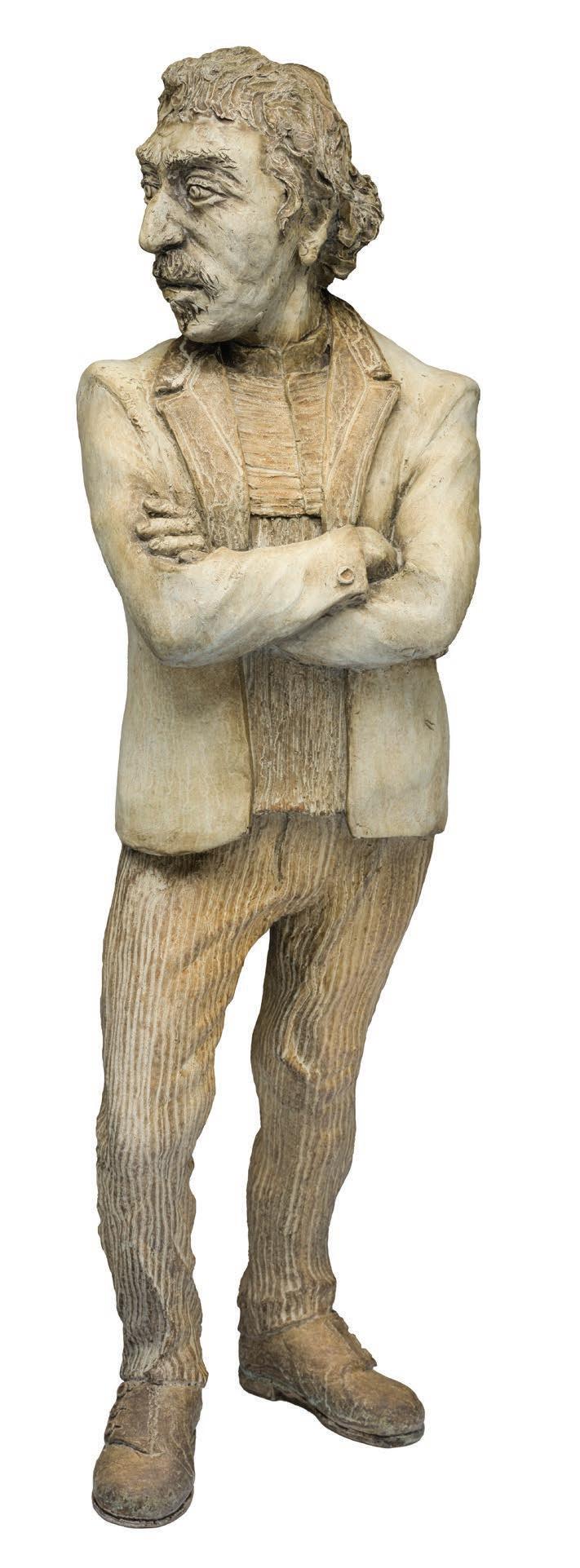

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Renoir

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 2/3 and dated 2012

35 × 32 × 29 in, 88.9 × 81.3 × 73.7 cm

23

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

23

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

24

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Dempsey (PH 2/3)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 2/3, dated 2015, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2019

29 × 7 3/4 × 8 1/2 in, 73.7 × 19.7 × 21.6 cm

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

25 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Gauguin (PH 4/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 4/7, dated 2018, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2022

27 1/4 × 9 1/4 × 7 in, 69.2 × 23.5 × 17.8 cm

26

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Georgia O’Keeffe (PH 7/7)

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, editioned 7/7, dated 2006, cast posthumously by Julienne Atelier and stamped JF 2021 40 1/4 × 14 3/4 × 10 1/2 in, 102.2 × 37.5 × 26.7 cm

27 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Emily 1904

bronze sculpture with patina, signed, titled, editioned 1/3 and dated 2013 77 × 27 × 77 7/8 in, 195.6 × 68.6 × 198 cm

Collection of Emily Carr University of Art + Design

Gift from Heffel to Emily Carr University of Art + Design

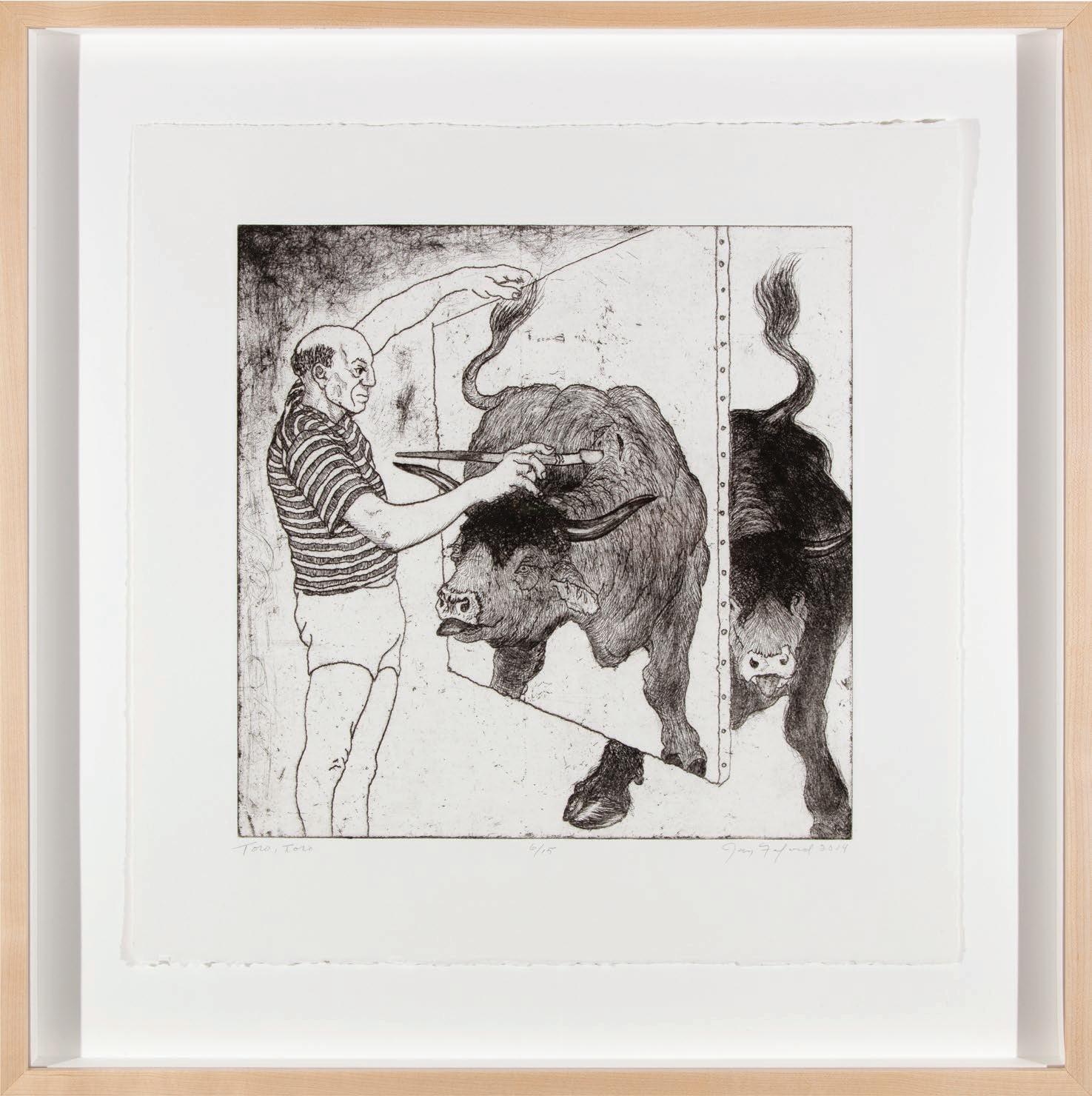

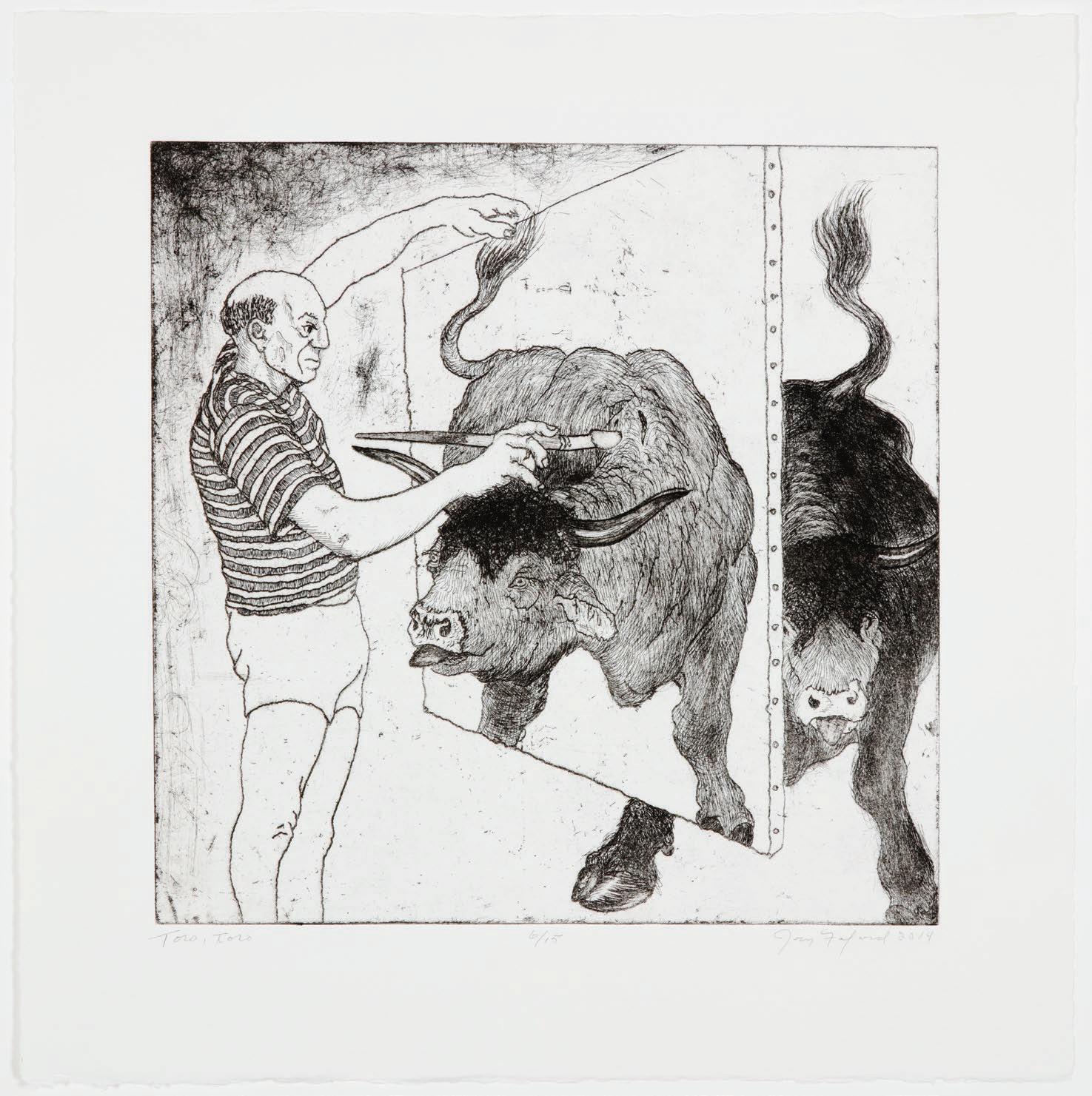

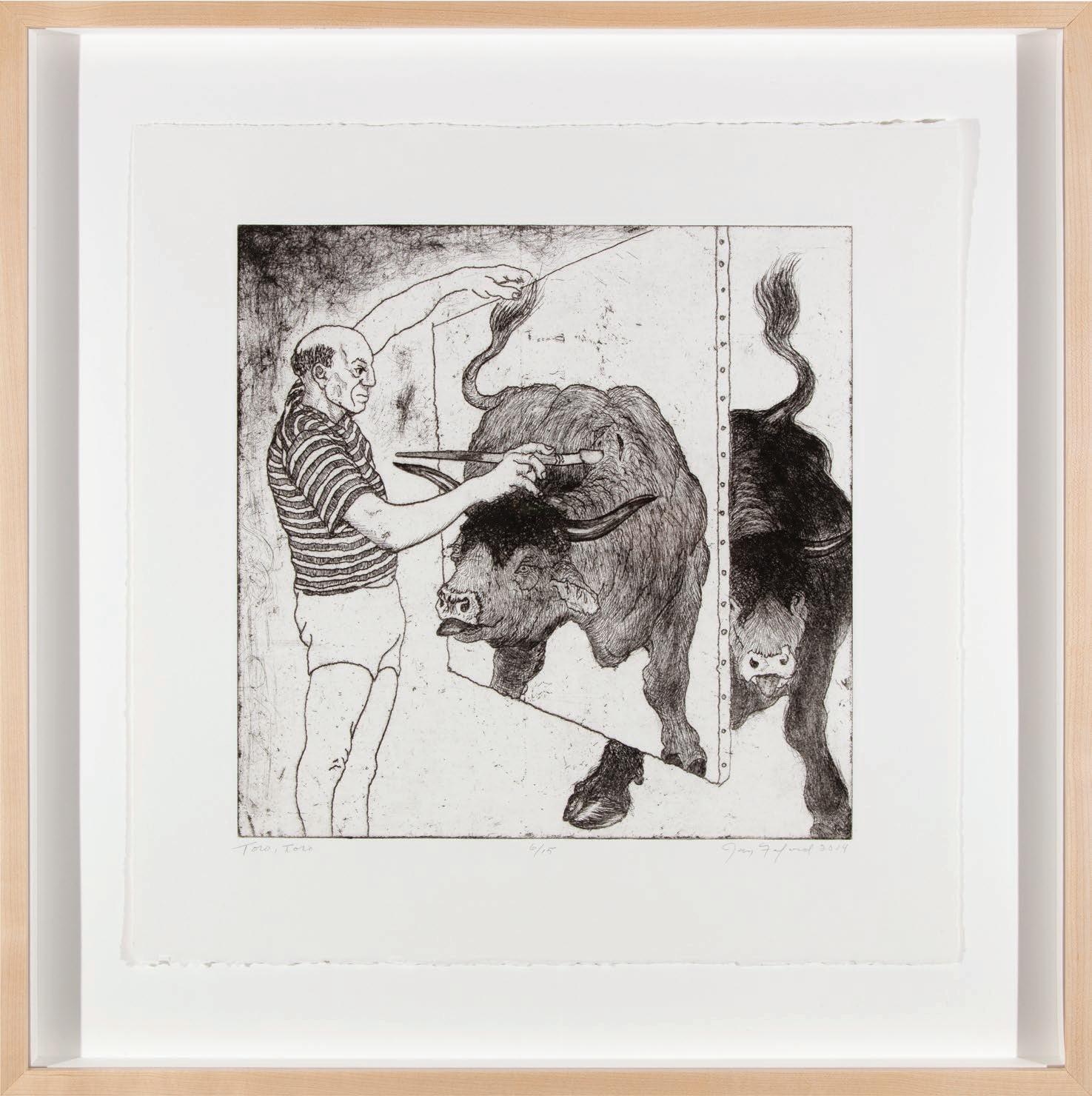

33 Toro Toro (6/15)

etching on paper

11 3/4 × 11 7/8 in, 29.8 × 30.2 cm

33 Toro Toro (6/15)

etching on paper

11 3/4 × 11 7/8 in, 29.8 × 30.2 cm

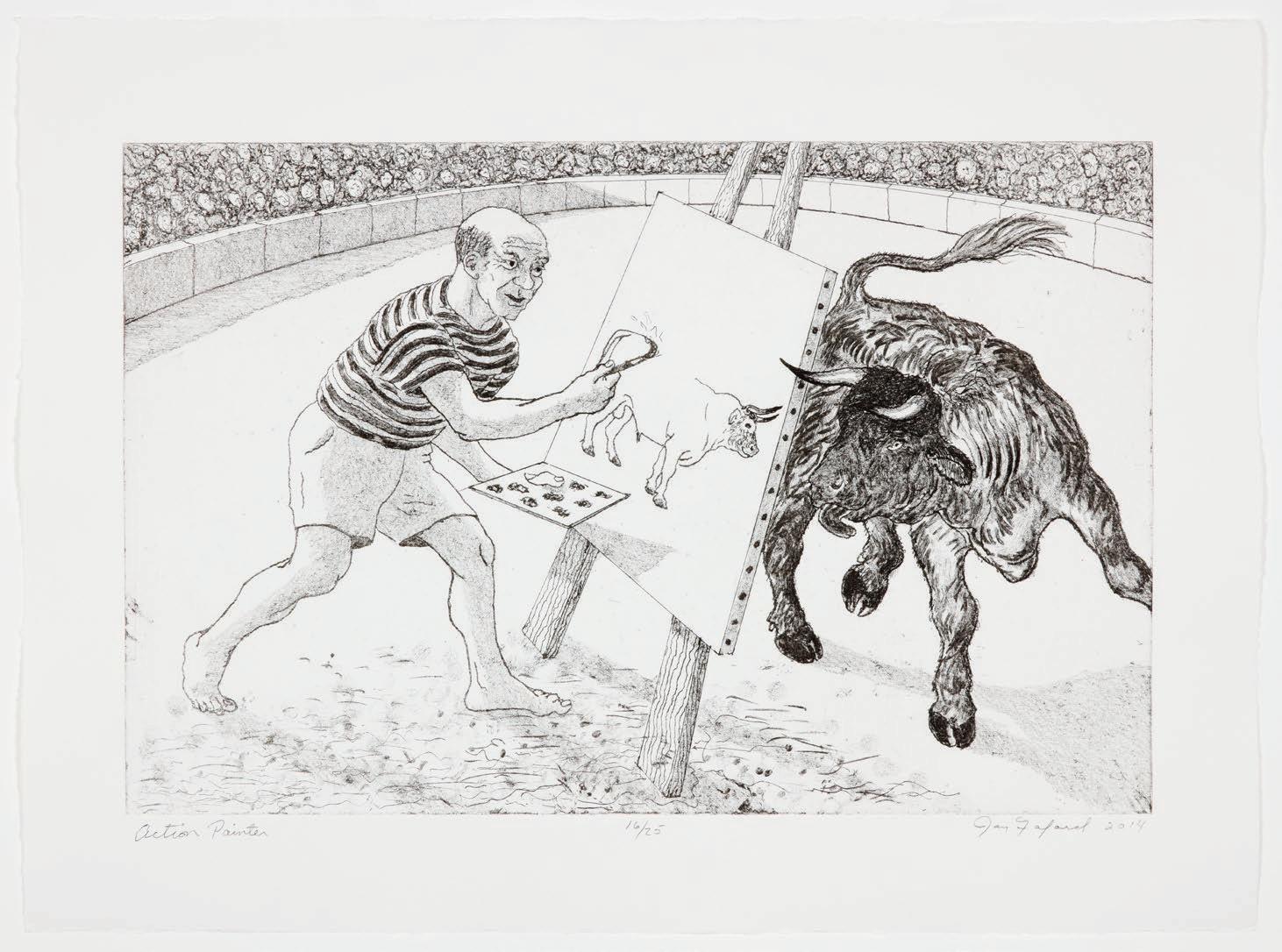

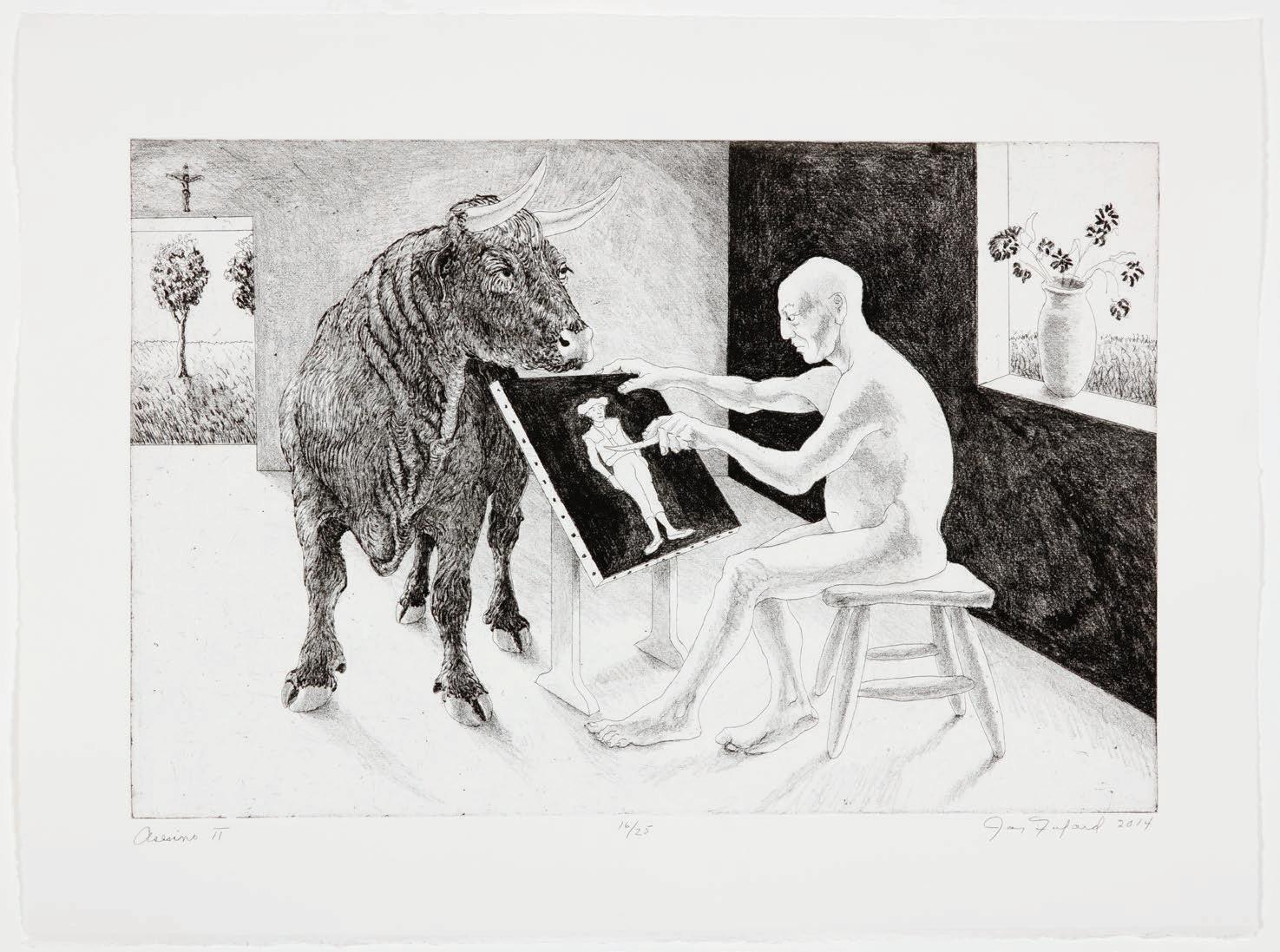

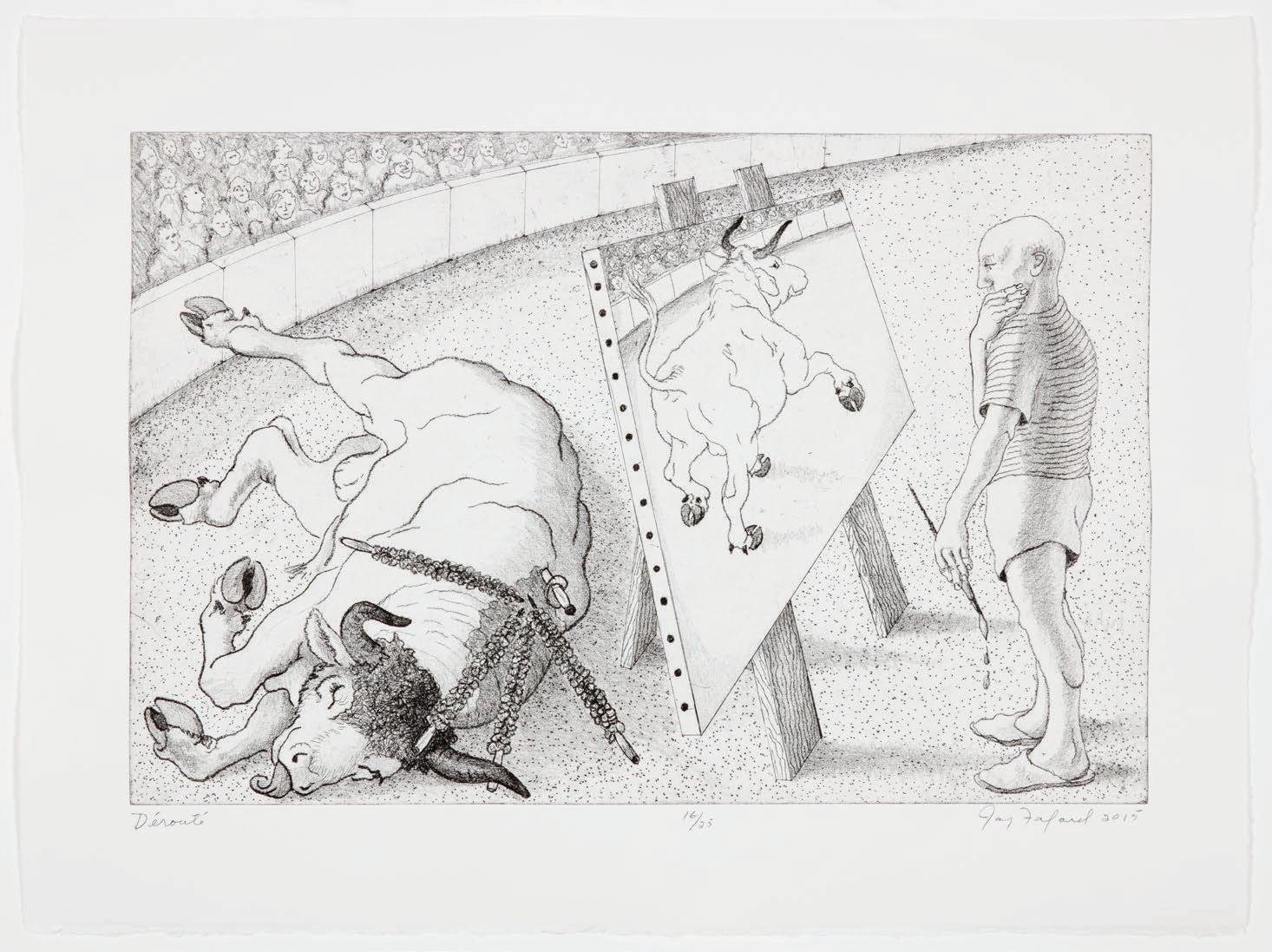

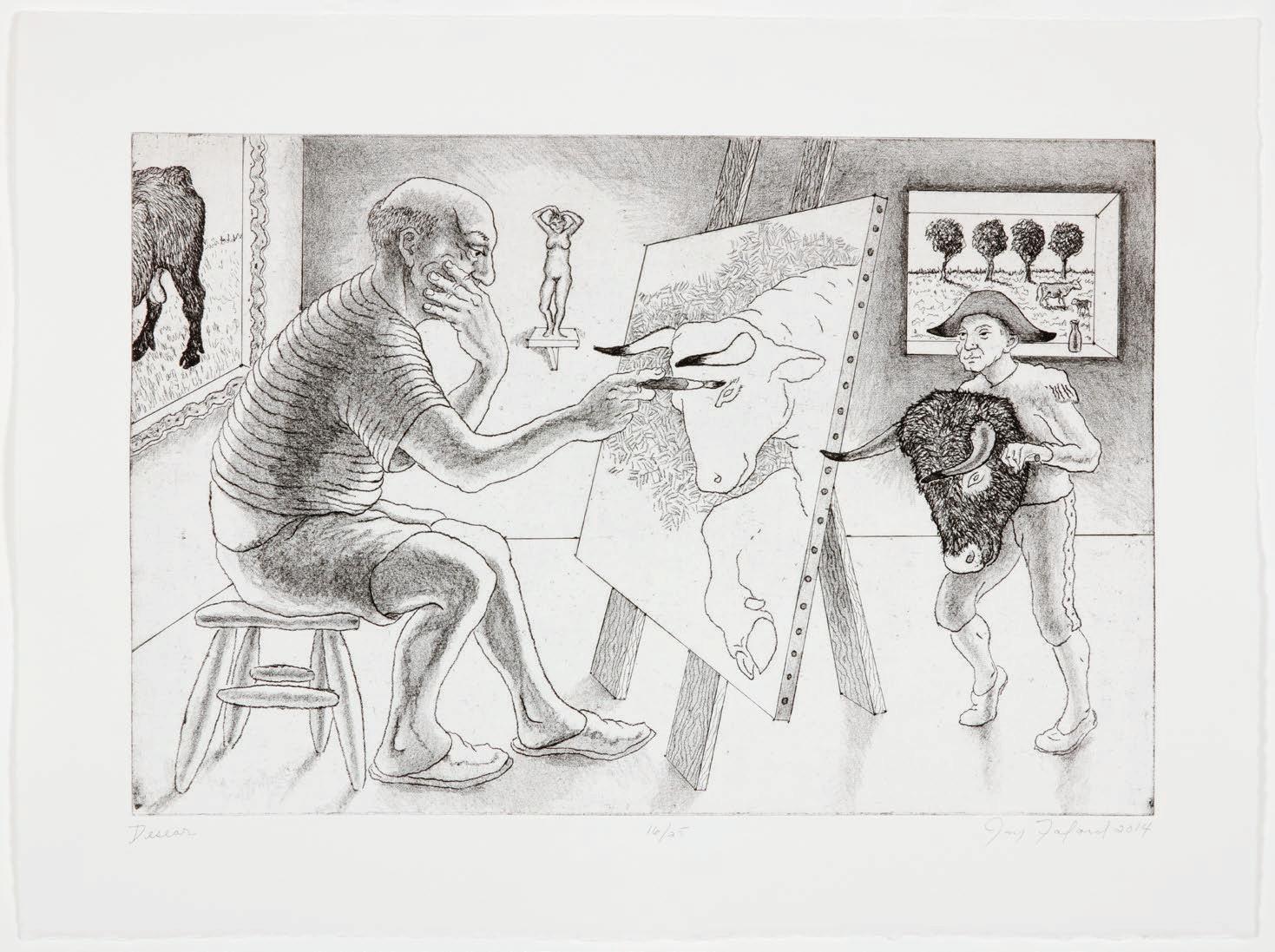

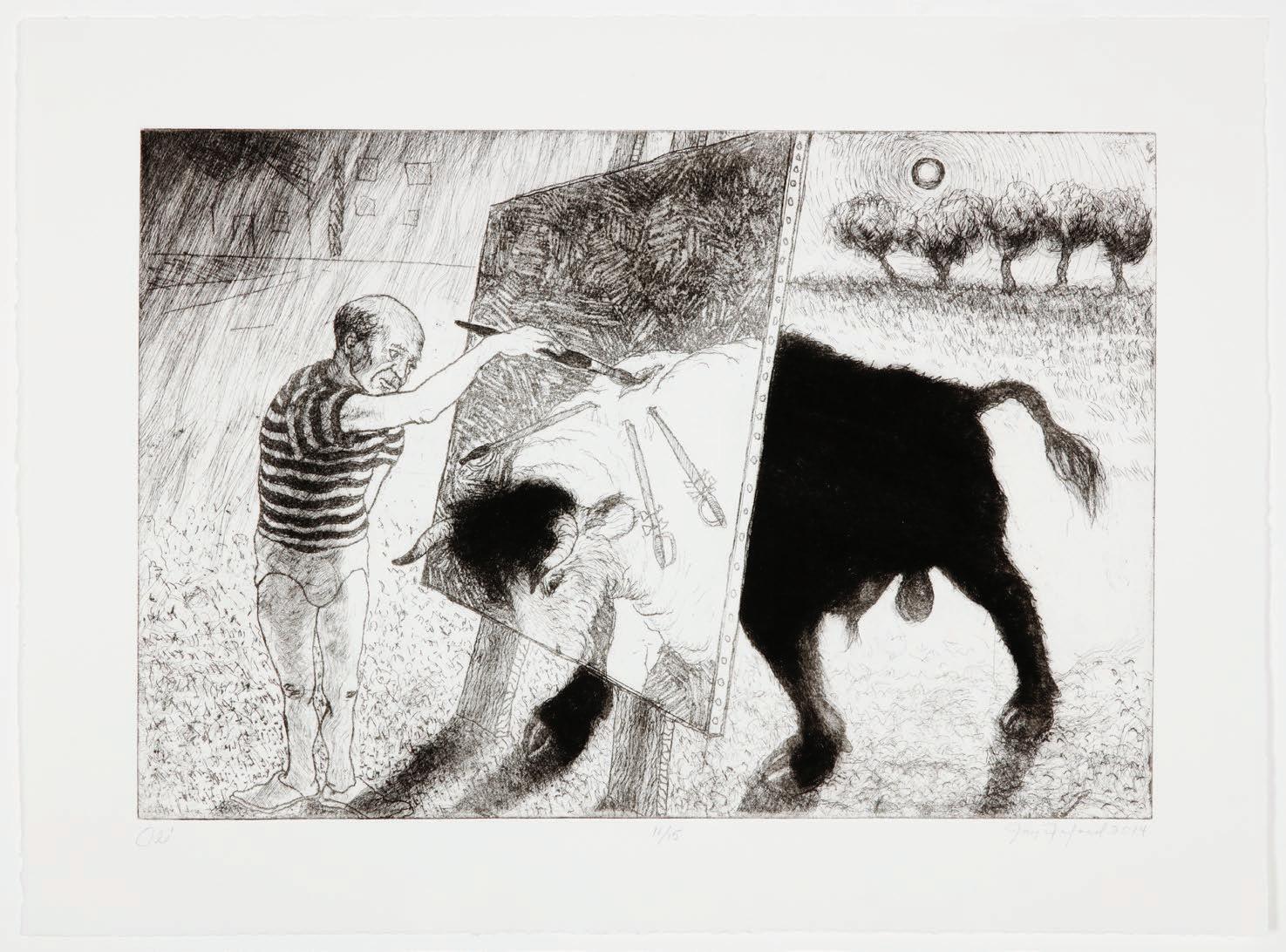

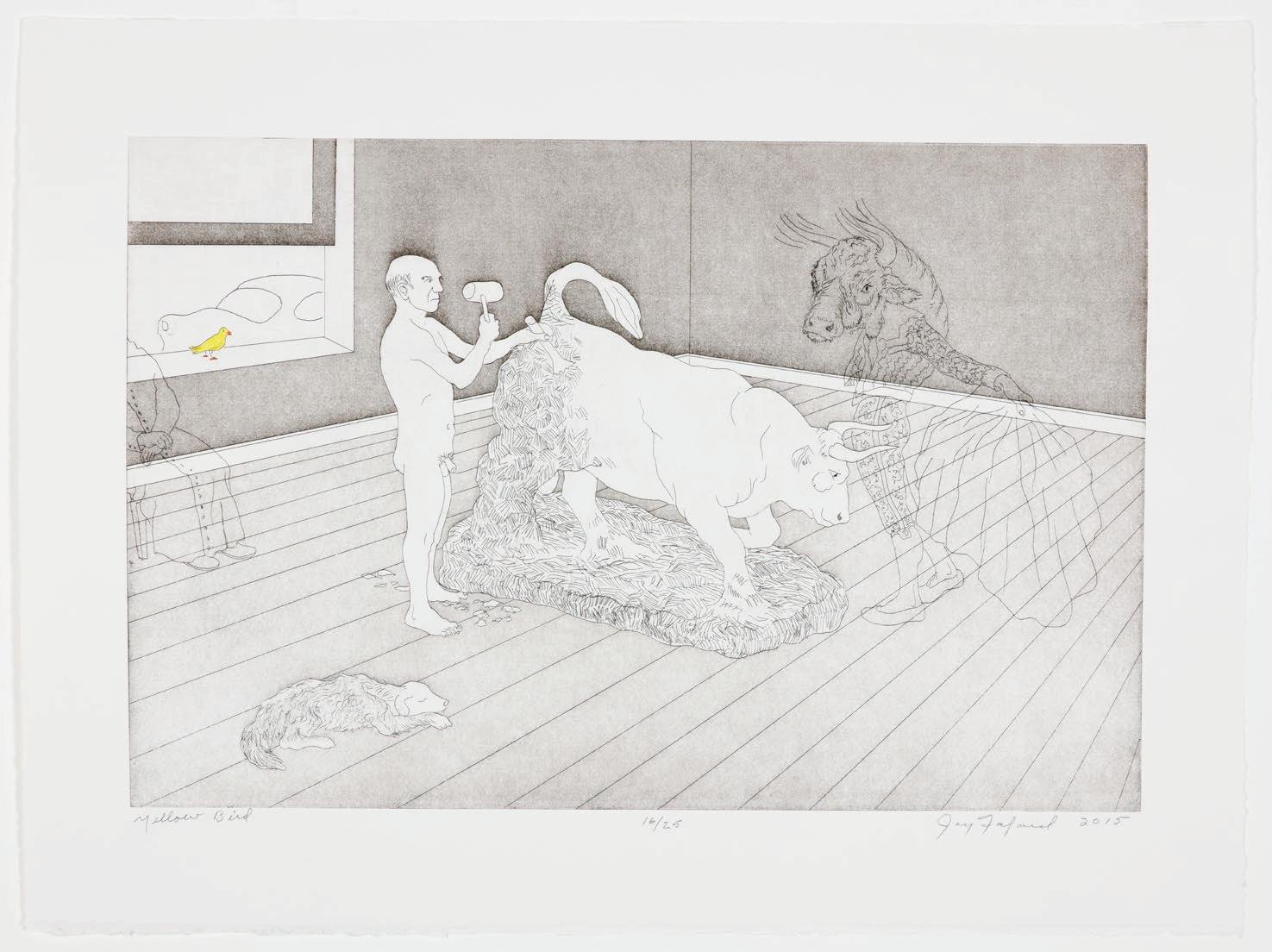

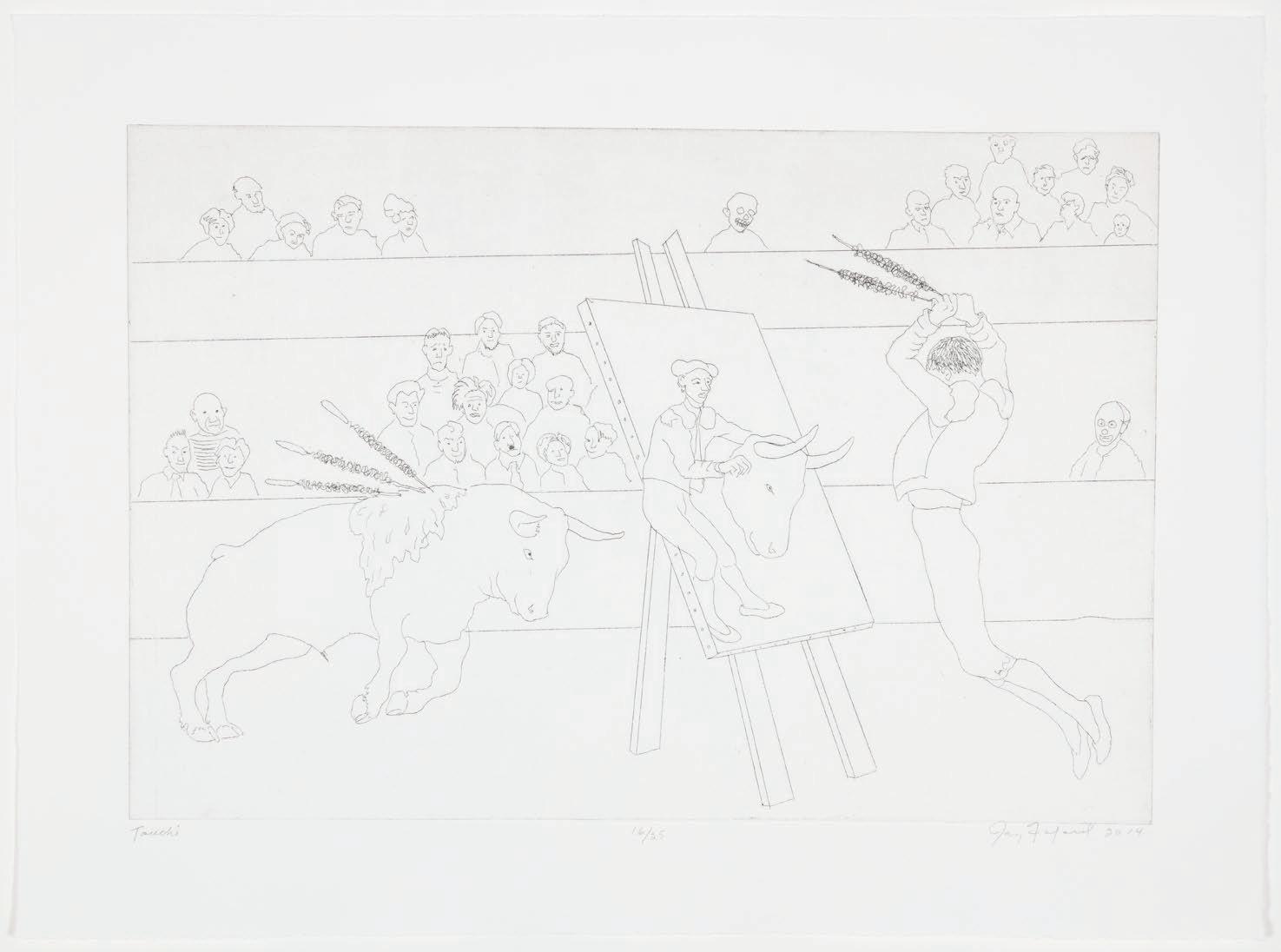

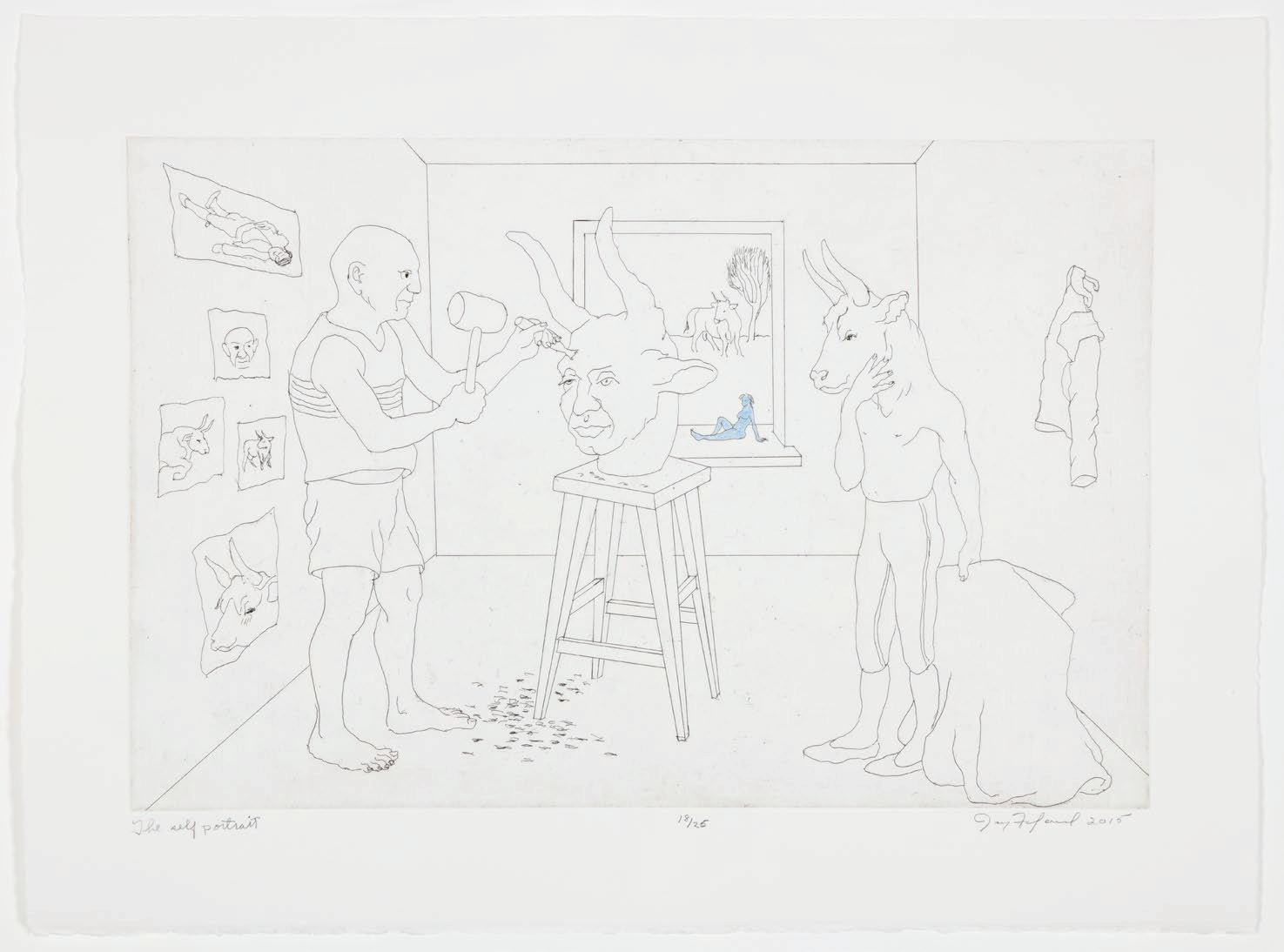

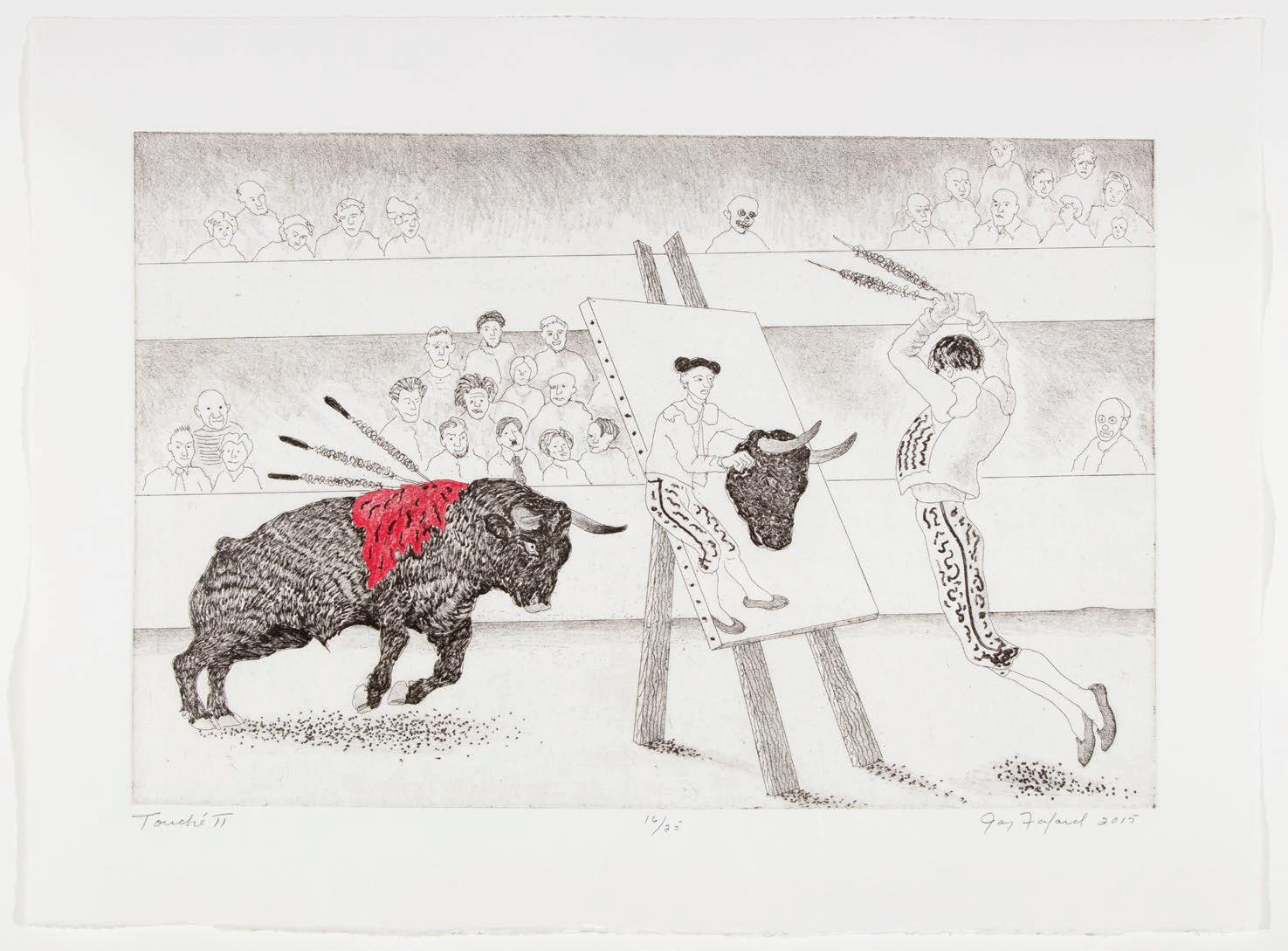

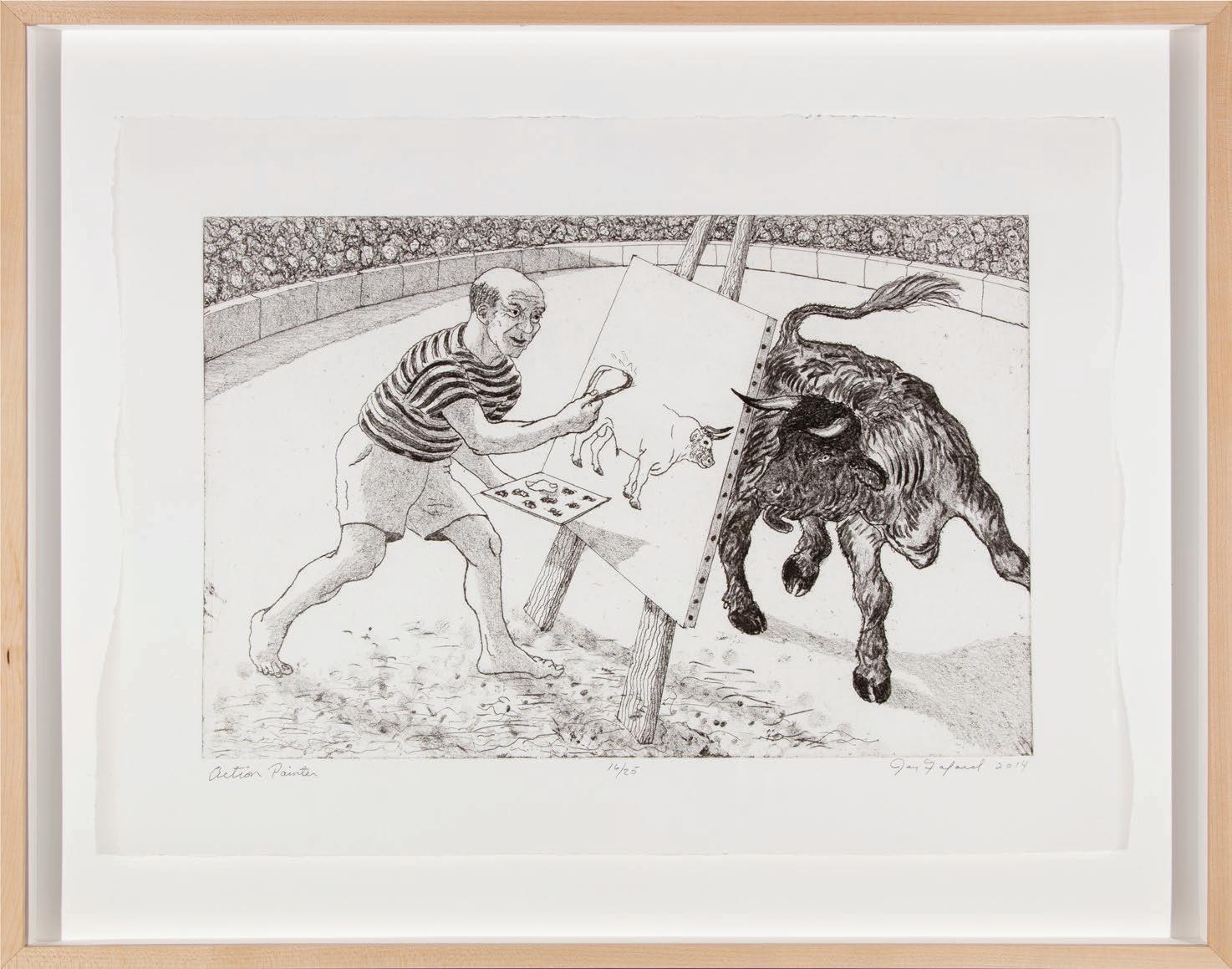

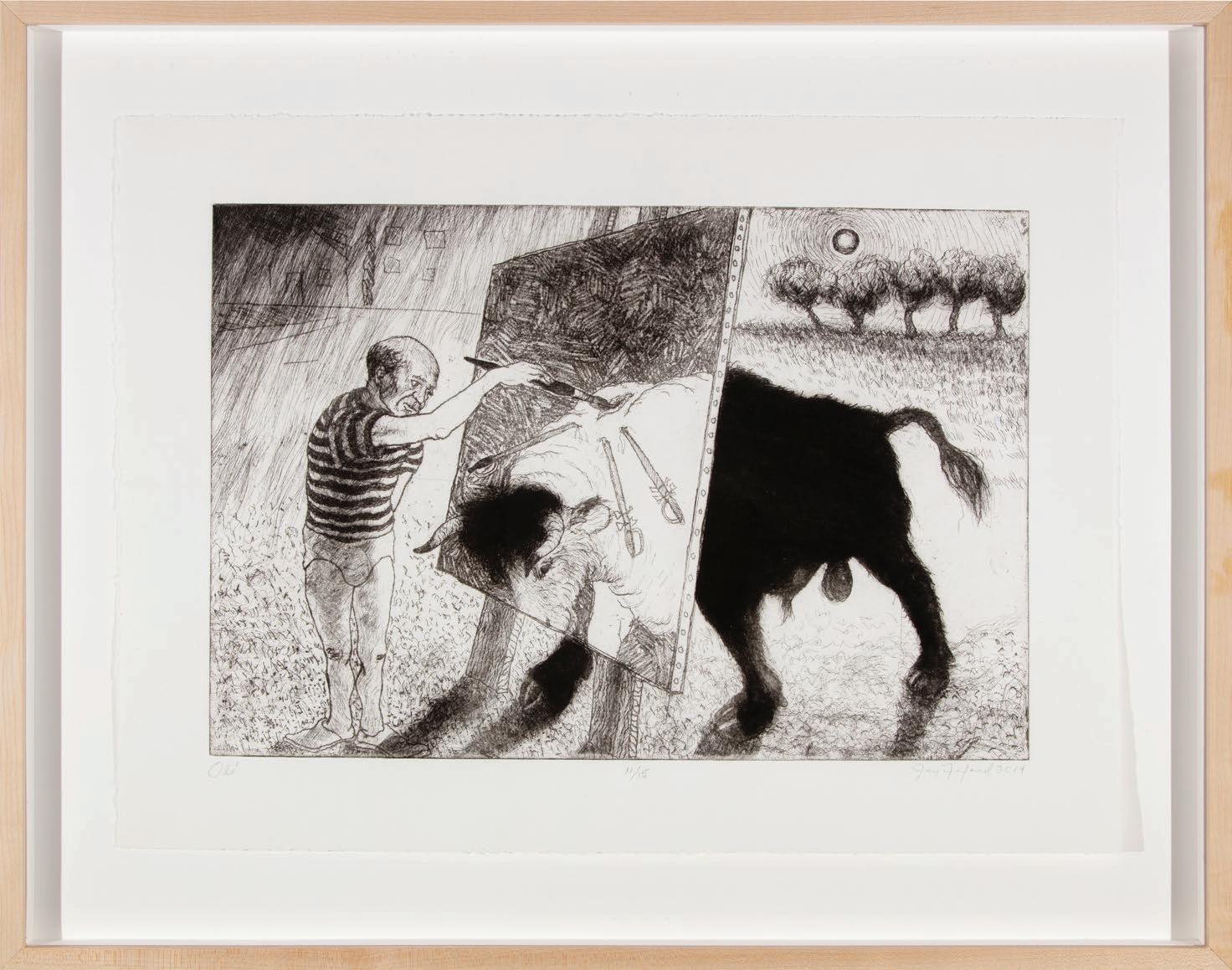

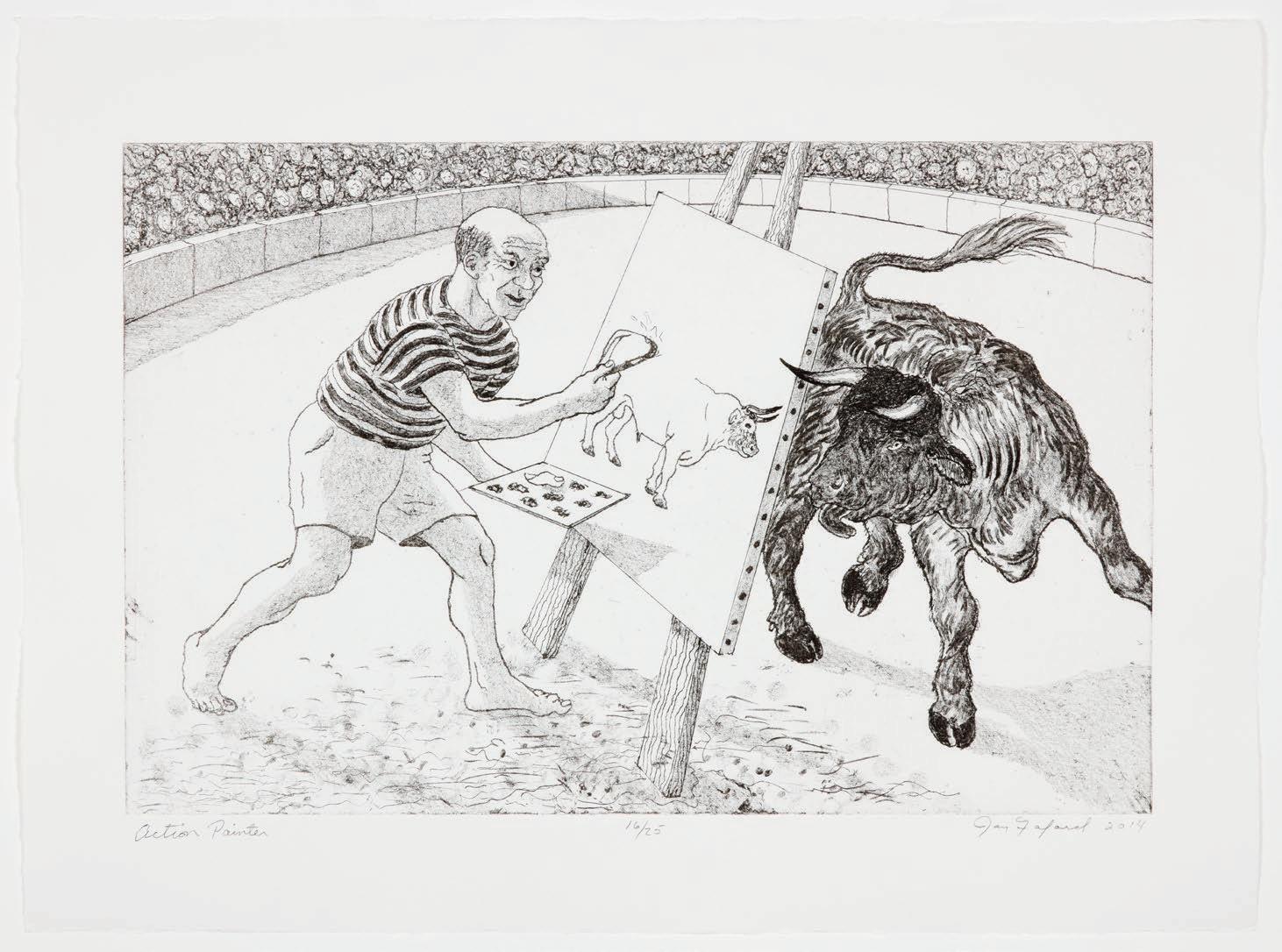

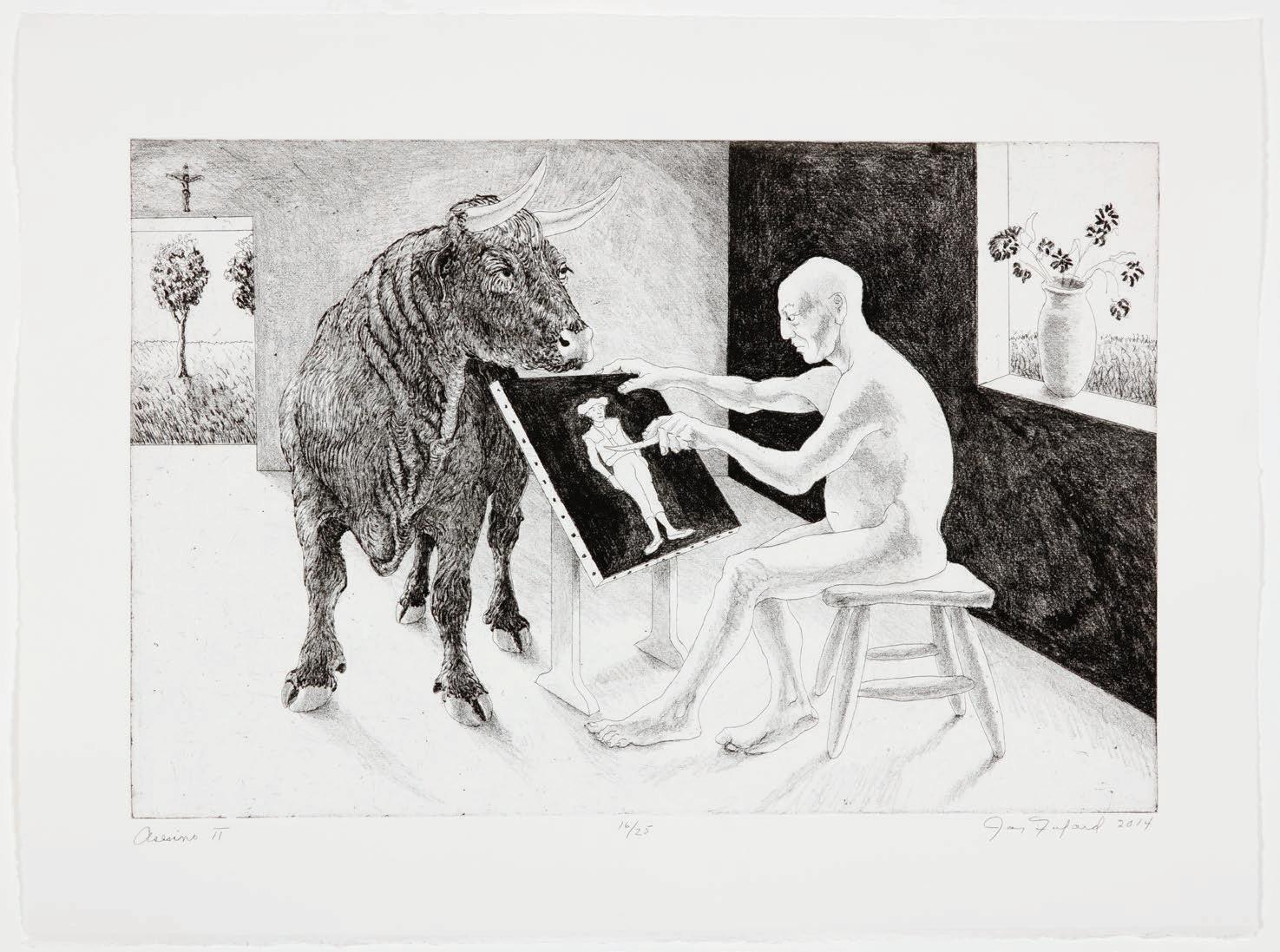

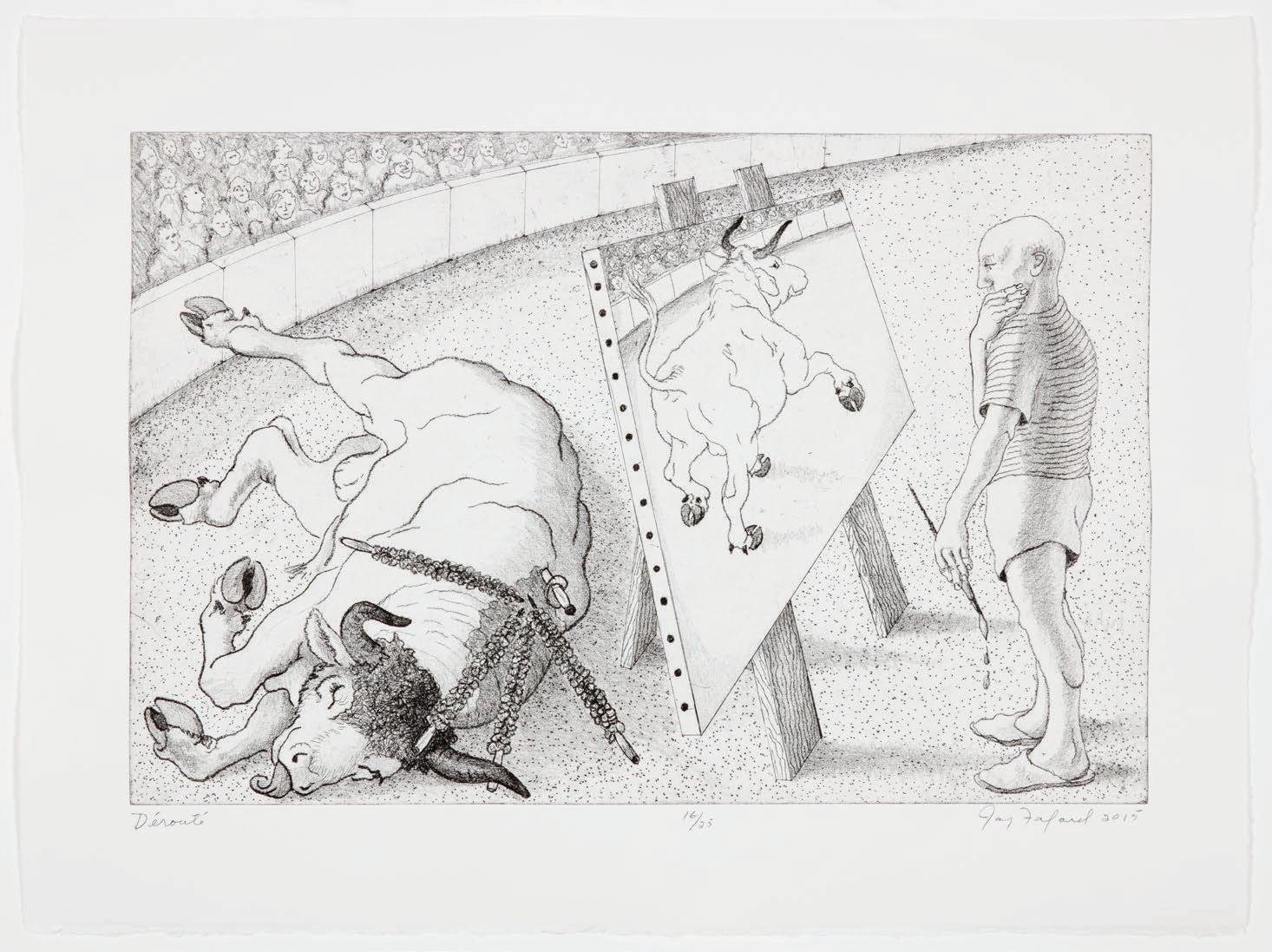

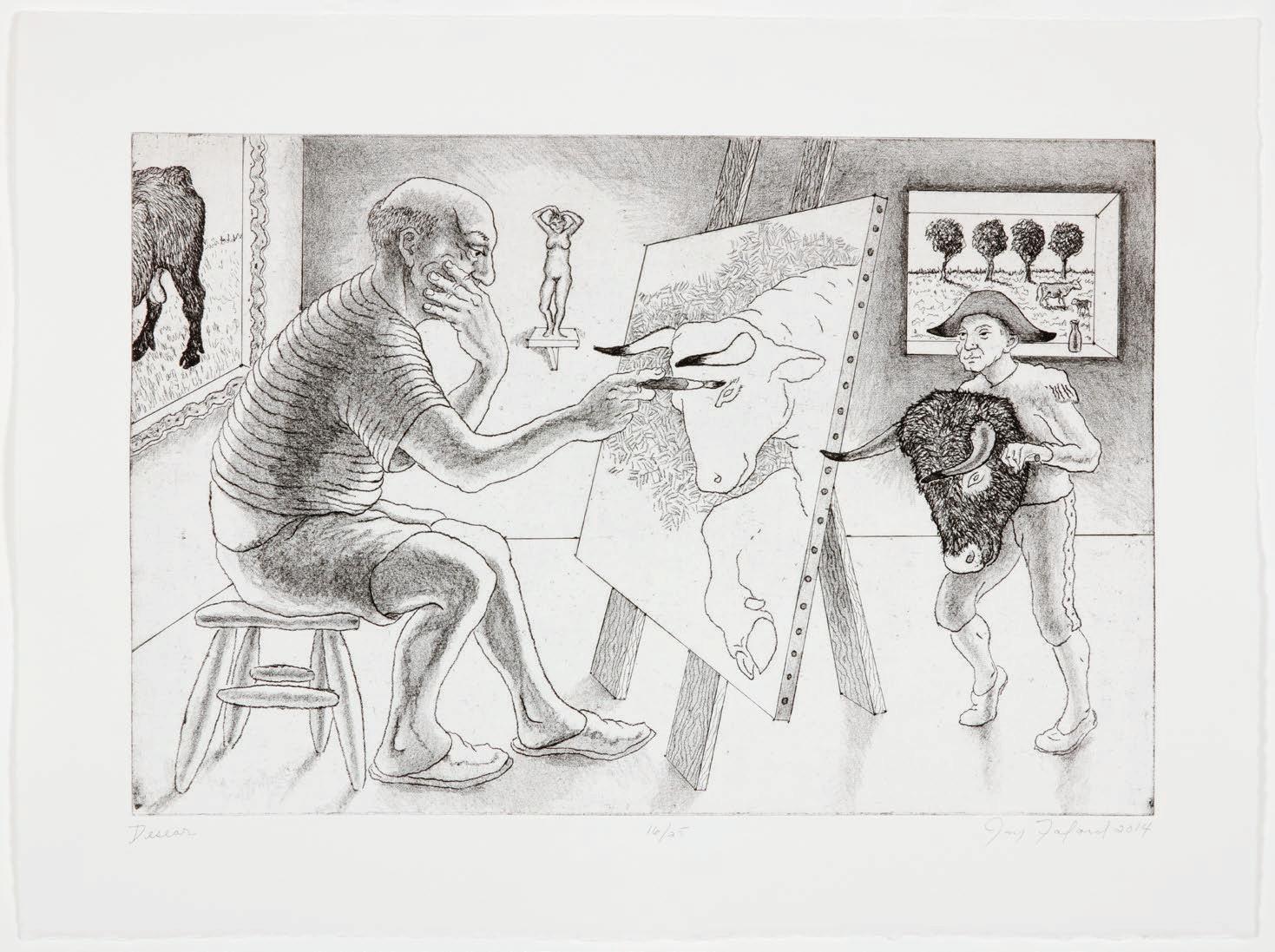

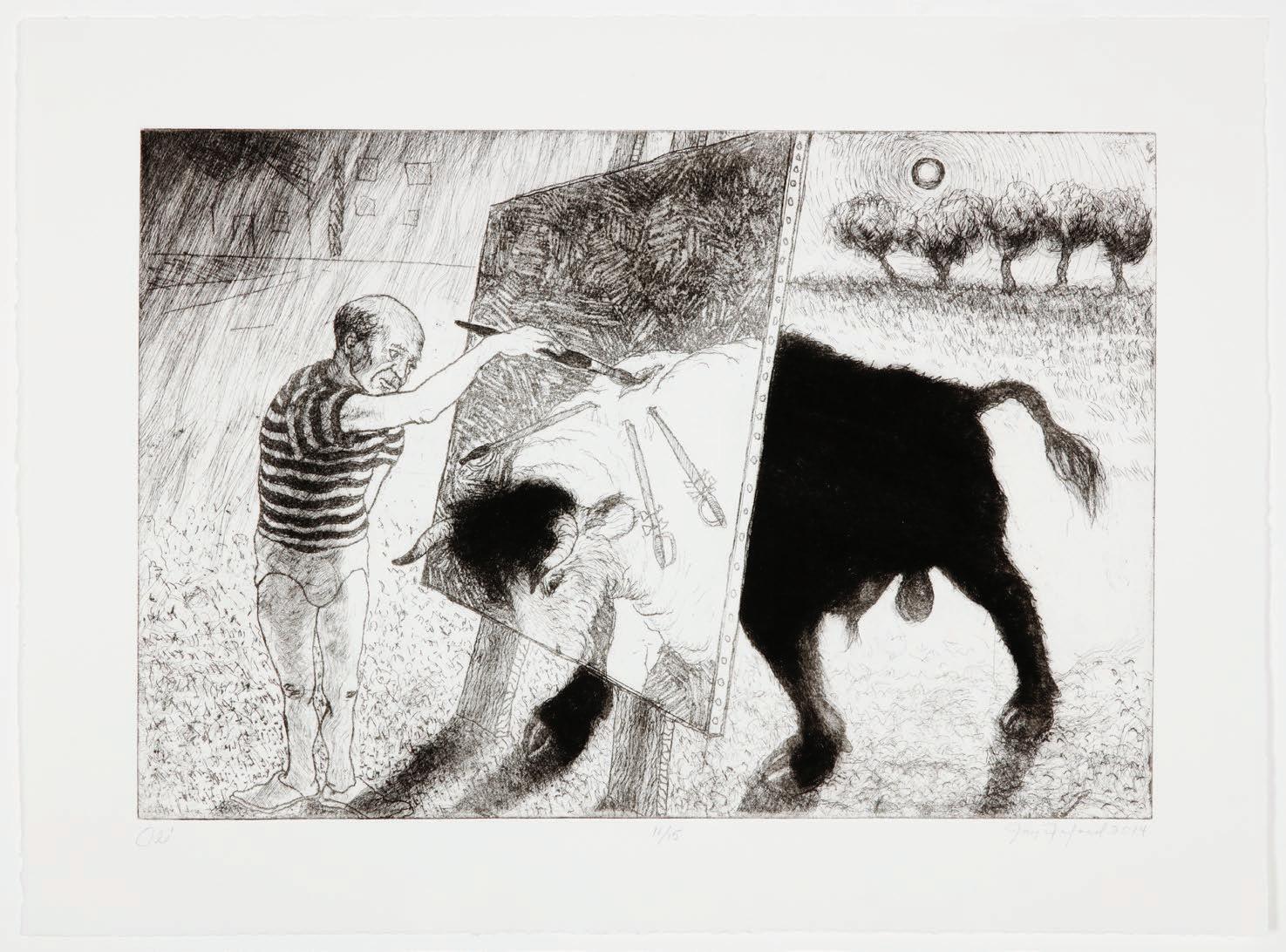

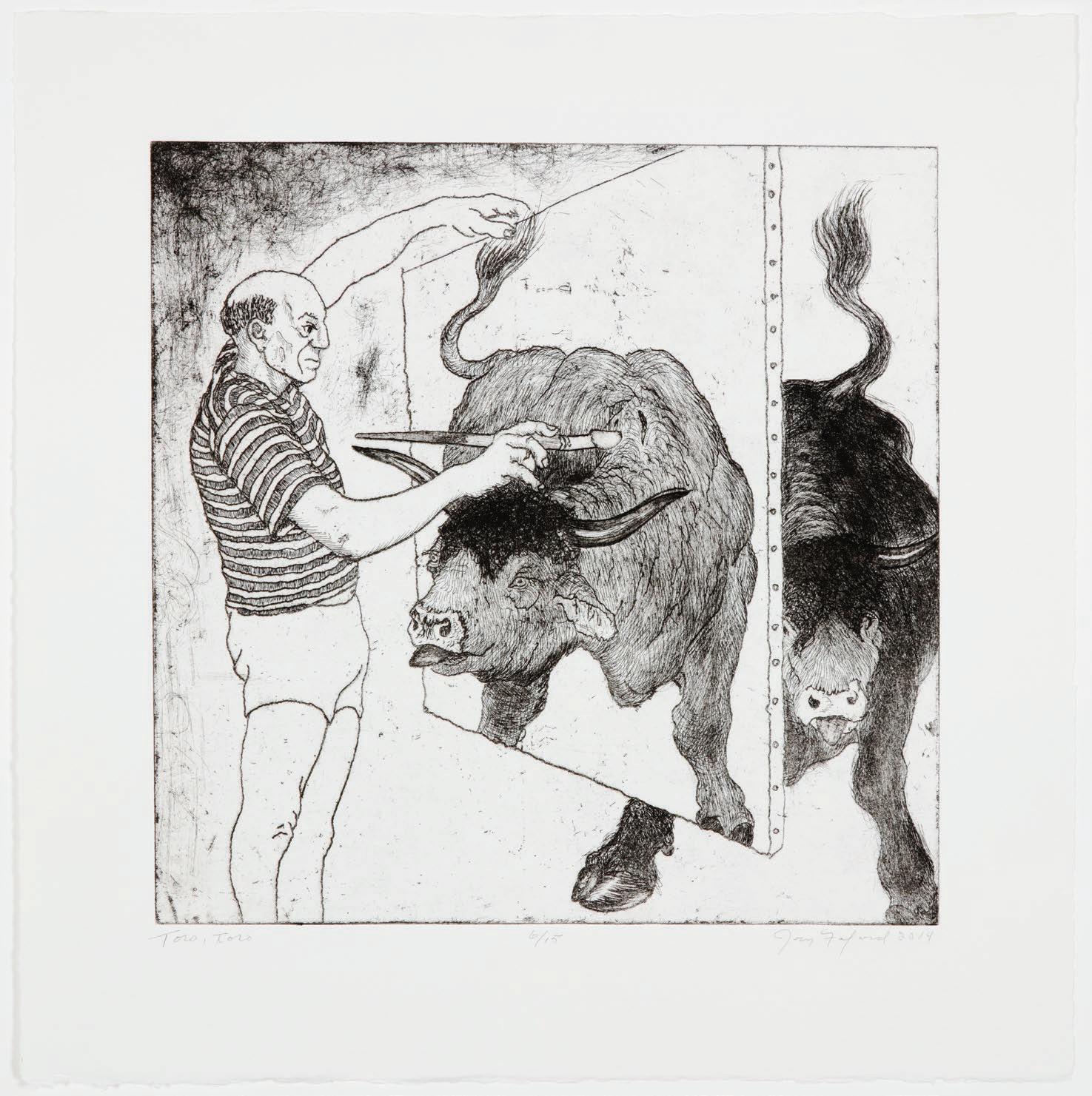

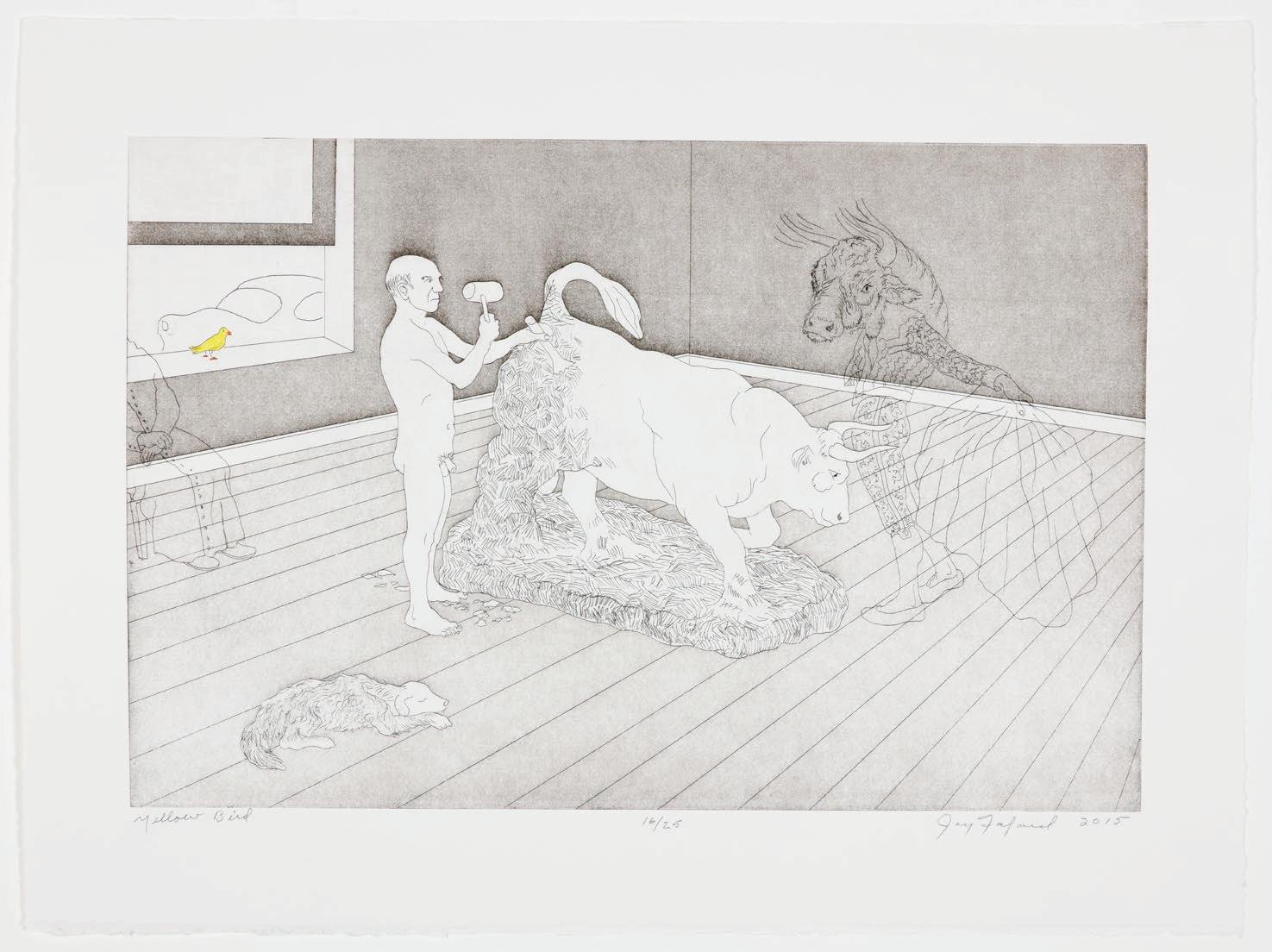

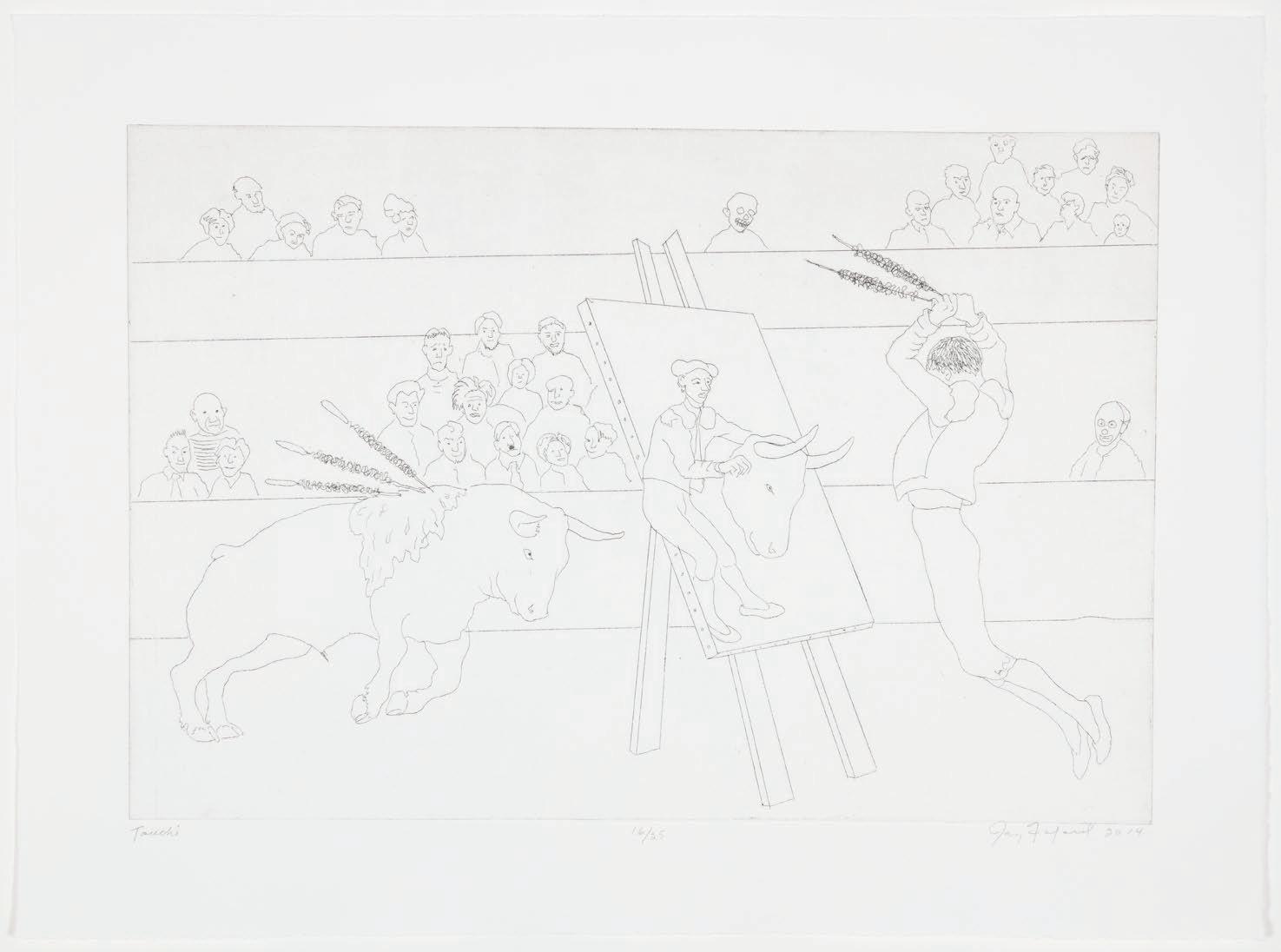

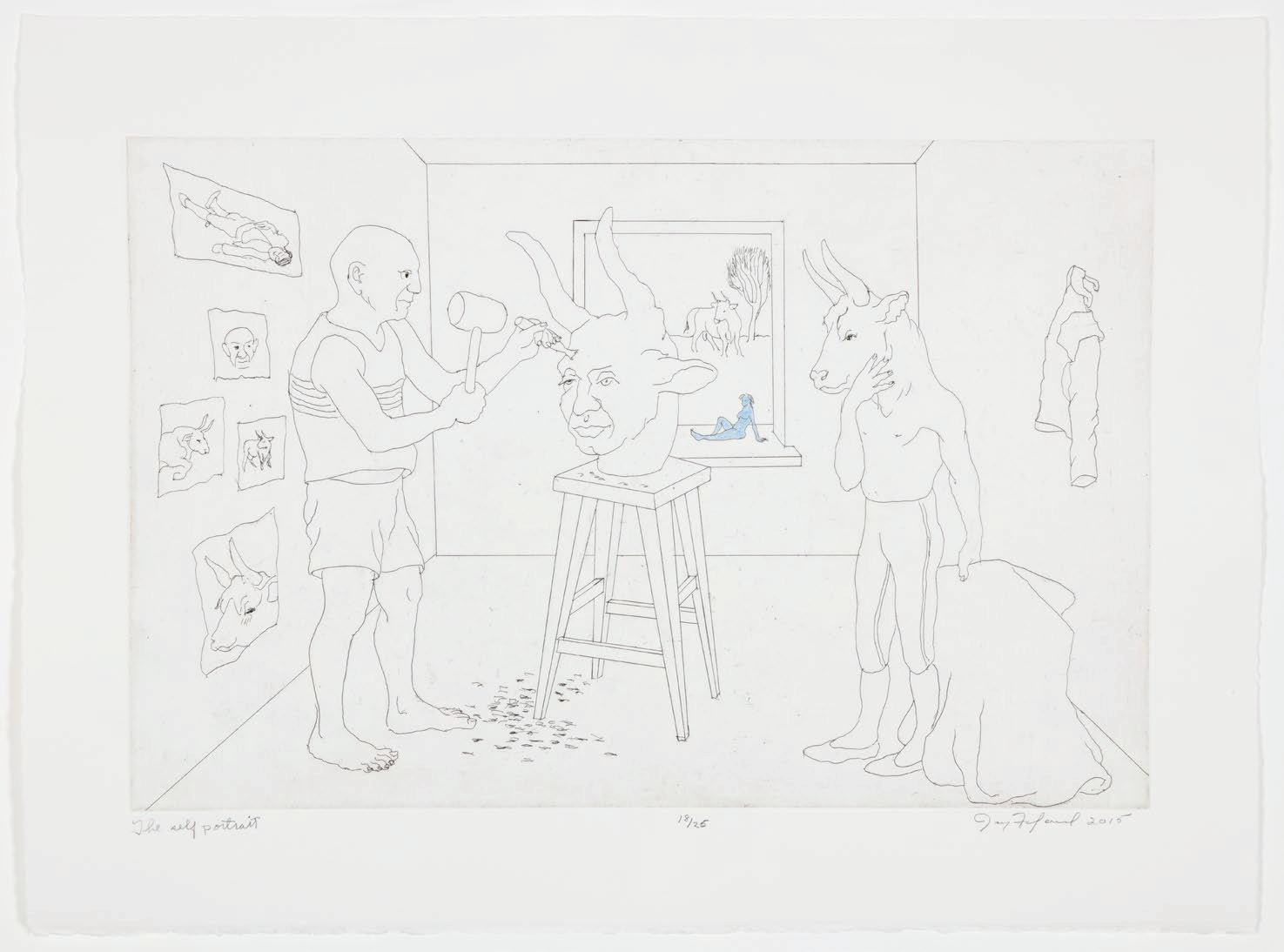

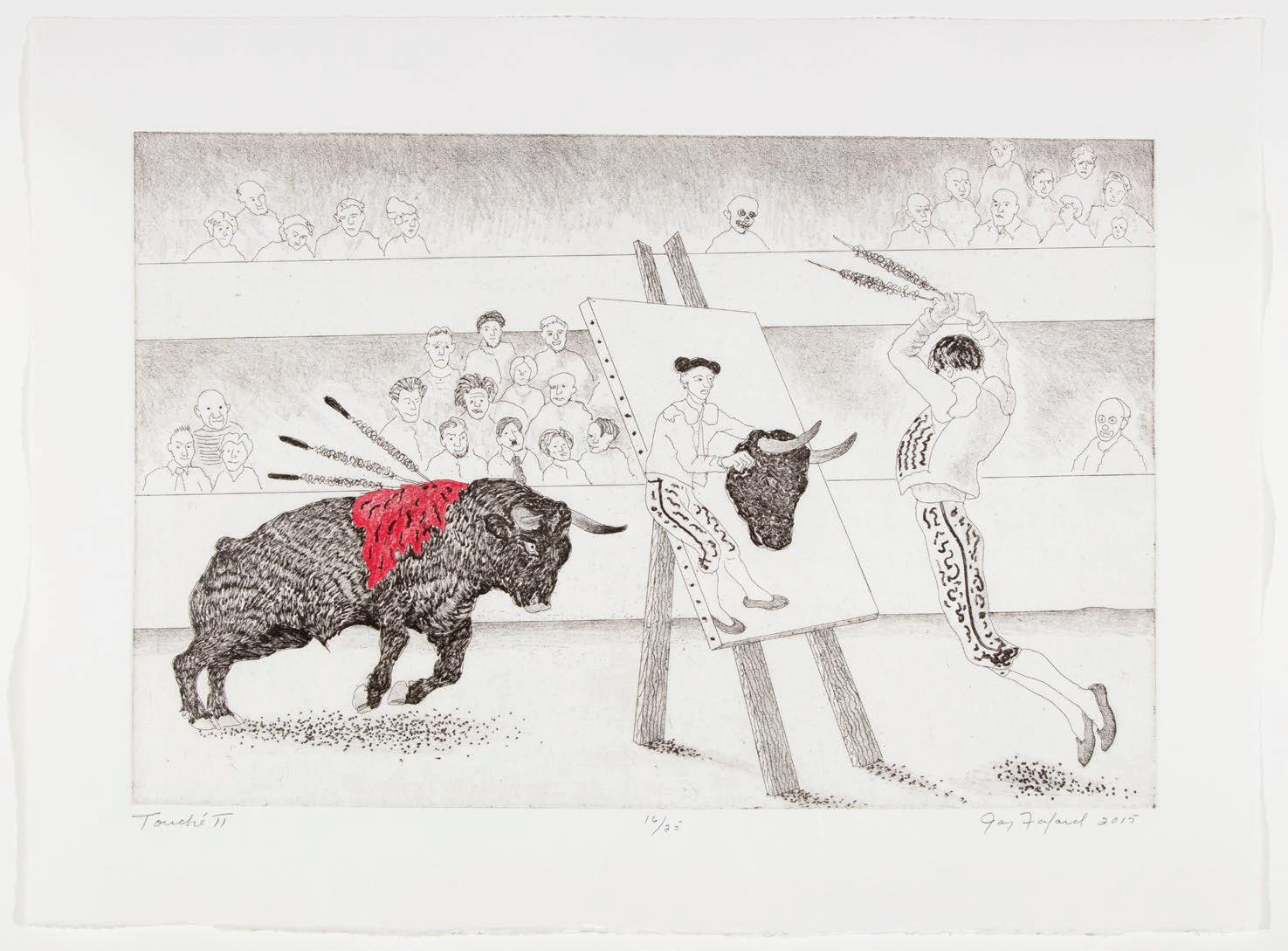

I N 2014 , Jo E fafa RD began working on a suite of 11 prints of Picasso with images based on the artist’s themes of the bull, bullfights and the Minotaur, the potent figure of the half-man, half-bull of Greek mythology. Born in Spain, Picasso had a strong connection to the world of the bullfight. As a young man he made a series of drawings featuring matadors and bulls, and this imagery continued throughout the course of his life. Picasso saw aspects of his own inner nature and virility in the Minotaur, in which the characteristics of the beast and the irrationality of the unconscious mind mingled and clashed with the higher, more refined qualities of man.

In images of Picasso painting and sculpting in his studio, Fafard’s treatment of these themes is playful and inventive. The artist is depicted at ease in loungewear, sometimes fully nude, perfectly comfortable and confident. However, Fafard offsets Picasso’s stability by shifting the boundaries of the artist’s subjects and location, as the bullfights seem to expand out of the canvas. The artist’s studio becomes the bullfighting ring; his paintbrush merges into swords and banderillas. The painter’s models become huge bulls that seem to leap through the canvas, or ghostly Minotaurs in the process of shifting between man and beast. In these compelling and dramatic etchings, Fafard imagines and captures Picasso’s vibrant, creative vision.

E N 2014 , Jo E fafa RD a entrepris une série de 11 gravures s’inspirant des œuvres de Picasso sur le thème des taureaux, de la corrida et du Minotaure, la figure puissante mi-homme, mi-taureau de la mythologie grecque. Né en Espagne, Picasso était très attaché au monde de la tauromachie. Dans sa jeunesse, il a réalisé une série de dessins représentant des matadors et des taureaux, et il s’est intéressé à ce thème toute sa vie. Picasso a vu dans le Minotaure des aspects de sa propre nature intérieure et de sa virilité, où les caractéristiques de la bête et l’irrationalité de l’inconscient se mêlent et s’opposent aux qualités plus élevées et plus raffinées de l’homme.

Dans les représentations de Picasso au travail dans son atelier, Fafard traite ces thèmes de manière ludique et inventive. On y voit l’artiste dans des vêtements de détente, parfois entièrement nu, parfaitement à l’aise et confiant. Cependant, Fafard contrebalance la stabilité de Picasso en déplaçant les limites des sujets et de l’emplacement de l’artiste, car les corridas semblent s’étendre hors de la toile. L’atelier de l’artiste devient l’arène et son pinceau, une épée et des banderilles. Les modèles du peintre sont d’énormes taureaux qui semblent traverser la toile en bondissant, ou un Minotaure fantomatique en train de se transformer d’homme à bête. Dans ces gravures fascinantes et dramatiques, Fafard imagine et capture la vision vibrante et créative de Picasso.

pi C asso print series

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Action Painter (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2014

11 3/4 × 17 7/8 in, 29.8 × 45.4 cm

28

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

28

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Asesino II (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2014

11 5/8 × 17 3/4 in, 29.5 × 45.1 cm

29 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

29 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Derouté (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2015

11 3/4 × 17 3/4 in, 29.8 × 45.1 cm

30

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

30

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Desear (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2014

11 3/4 × 17 3/4 in, 29.8 × 45.1 cm

31 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

31 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Olé (11/15)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 11/15 and dated 2014

12 × 17 3/4 in, 30.5 × 45.1 cm

32 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

32 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Toro Toro (6/15)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 6/15 and dated 2014

11 3/4 × 11 7/8 in, 29.8 × 30.2 cm

33 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

33 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Yellow Bird (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2015

11 3/4 × 17 3/4 in, 29.8 × 45.1 cm

34 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

34 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Touché (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2014

12 × 17 in, 30.5 × 43.2 cm

35 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

35 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Asesino I (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25

and dated 2014

11 5/8 × 17 3/4 in, 29.5 × 45.1 cm

36 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

The self portrait (18/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 18/25 and dated 2015

11 5/8 × 17 3/4 in, 29.5 × 45.1 cm

37 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

37 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

oc RCA 1942 – 2019

Touché II (16/25)

etching on paper, signed, titled, editioned 16/25 and dated 2015

11 3/4 × 17 3/4 in, 29.8 × 45.1 cm

38 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

38 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Fafard (from the Portrait Project) gelatin silver photograph, on verso signed, titled, editioned 4/13 and inscribed Regina, SK . – May 1993 18 3/4 × 15 in, 47.6 × 38.1 cm

39 Jürgen Vogt

39 Jürgen Vogt

13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto Ontario, Canada m 5 R 2 E 1

Tel 416-961-6505, Fax 416-961-4245

Toll Free 1-888-818-6505

www.heffel.com

Follow us @HeffelAuction:

L I X

C opyright

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written consent

ISbN: 978-1-927031-62-9

Printed in Canada B

h e FF el g allery t oronto

ack cover/couverture arr I ère:

sculpture

35 × 14 1/2 × 7 in, 88.9 × 36.8 × 17.8 cm

11 Selfie (PH AP II ) bronze

with patina

F a F

ard & F riends

a s elling e xhibition

32 Olé (11/15) etching on paper

12 × 17 3/4 in, 30.5 × 45.1 cm

32 Olé (11/15) etching on paper

12 × 17 3/4 in, 30.5 × 45.1 cm

Heffel staff with Joe Fafard at the opening of Joe Fafard, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2008

Joe Fafard next to Pense sign

Photo: Ernest Mayer Courtesy of Ernest Mayer

Heffel staff with Joe Fafard at the opening of Joe Fafard, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2008

Joe Fafard next to Pense sign

Photo: Ernest Mayer Courtesy of Ernest Mayer

Joe Fafard

Unknown photographer

David and Robert Heffel with Joe Fafard (far right), Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Pierre Théberge, former director of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2008

Joe Fafard

Unknown photographer

David and Robert Heffel with Joe Fafard (far right), Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Pierre Théberge, former director of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2008

Joe Fafard in his studio

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joe Fafard in his studio

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard D.H.

bronze sculpture with patina, 1994 43 × 15 × 4 in, 109.2 × 38.1 × 10.2 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Auguste Renoir

bronze sculpture with patina, 1999 14 × 10 × 8 in, 35.6 × 25.4 × 20.3 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard D.H.

bronze sculpture with patina, 1994 43 × 15 × 4 in, 109.2 × 38.1 × 10.2 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard Auguste Renoir

bronze sculpture with patina, 1999 14 × 10 × 8 in, 35.6 × 25.4 × 20.3 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Joe Fafard, 2016

Photo: © Joseph Hartman

Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

Joe Fafard, 2016

Photo: © Joseph Hartman

Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto

Joe Fafard in his studio, Pense, 1979

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joe Fafard in his studio, Pense, 1979

Photo: Don Hall Courtesy of Don Hall

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

Vincent Self-Portrait Series painted ceramic

Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

Vincent Self-Portrait Series painted ceramic

Joe Fafard, 2018

Photo: Gary Robins Courtesy of Gary Robins

Jo E

Joe Fafard, 2018

Photo: Gary Robins Courtesy of Gary Robins

Jo E

Ph I l tRE mblay Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier

Phil Tremblay, Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier, with Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9 ), 2023

Ph I l tRE mblay Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier

Phil Tremblay, Manager & Director of Operations, Julienne Atelier, with Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9 ), 2023

Joe Fafard with a model for The Sower, 2019

Joe Fafard with a model for The Sower, 2019

FI g URE 1: Portrait of Pablo Picasso

Photo: Arnold Newman

Courtesy of Getty Images

FI g URE 1: Portrait of Pablo Picasso

Photo: Arnold Newman

Courtesy of Getty Images

FI g URE 2: Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

The Opening

bronze sculpture with patina, glass and neon light on a wood base, 1988

33 × 17 3/4 × 12 1/2 in, 83.8 × 45.1 × 31.8 cm

Private Collection

Sold

FI g URE 2: Joseph h e C tor y von (Joe) Fa Fard

The Opening

bronze sculpture with patina, glass and neon light on a wood base, 1988

33 × 17 3/4 × 12 1/2 in, 83.8 × 45.1 × 31.8 cm

Private Collection

Sold

Picasso on a Chair in the process of being cast

Picasso on a Chair in the process of being cast

Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9) at Julienne Atelier, 2023

Picasso on a Chair (PH 6/9) at Julienne Atelier, 2023

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

5 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

5 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Selfie in the process of being cast

Selfie in the process of being cast

Selfie in the process of being cast, with a completed lifetime version behind

Selfie in the process of being cast, with a completed lifetime version behind

Joe Fafard with Selfie, 2018

Joe Fafard with Selfie, 2018

Fafard

Fafard

23

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

23

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

33 Toro Toro (6/15)

etching on paper

11 3/4 × 11 7/8 in, 29.8 × 30.2 cm

33 Toro Toro (6/15)

etching on paper

11 3/4 × 11 7/8 in, 29.8 × 30.2 cm

28

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

28

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

29 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

29 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

30

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

30

Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

31 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

31 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

32 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

32 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

33 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

33 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

34 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

34 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

35 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

35 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

37 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

37 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

38 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

38 Joseph Hector Yvon (Joe) Fafard

39 Jürgen Vogt

39 Jürgen Vogt